Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

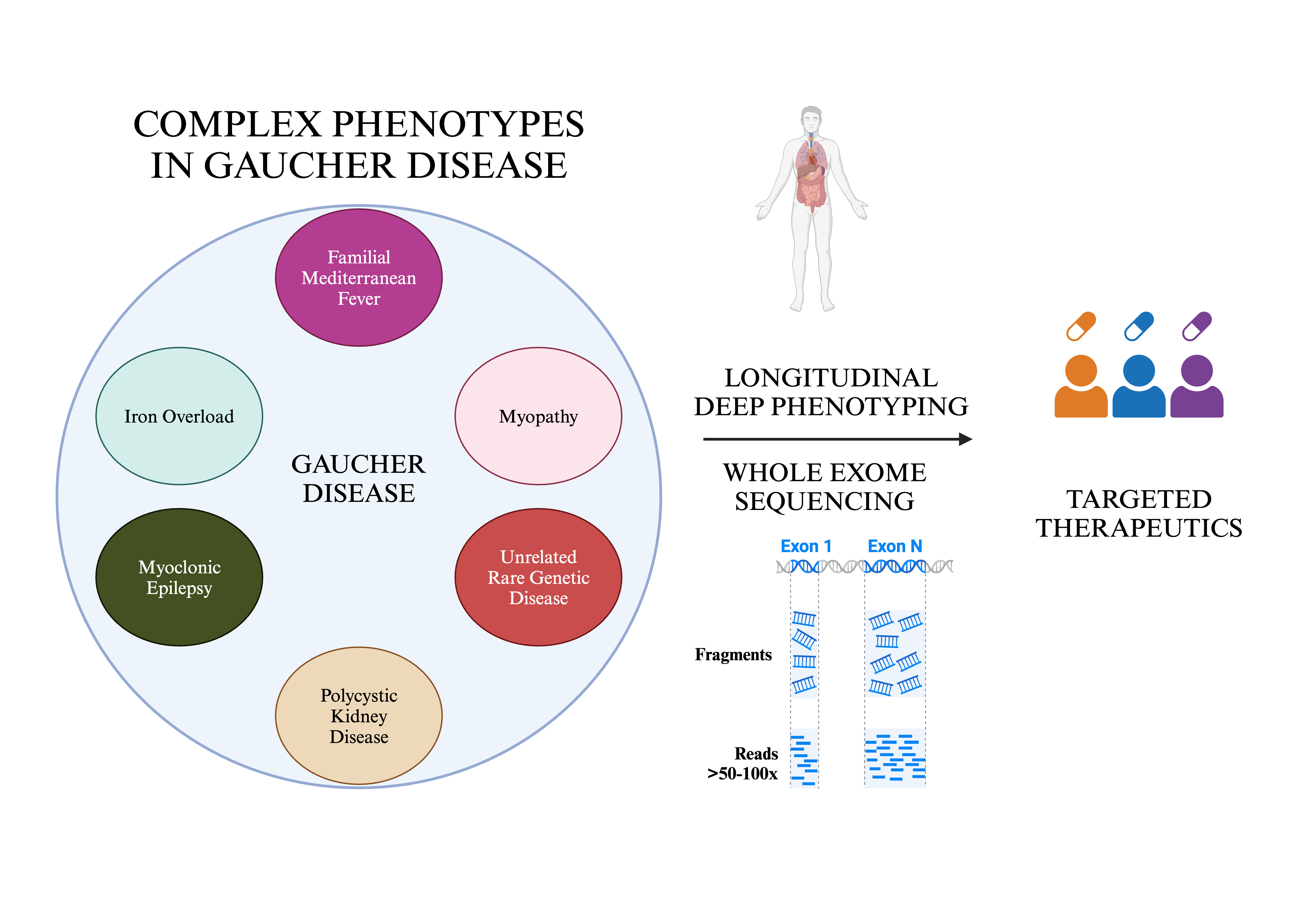

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Cohort

2.2. Longitudinal Deep Phenotyping

2.3. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

- I.

- Unusual inflammatory symptoms due to concurrent Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) in GD1 (n=4).

- II.

- Myopathy, osteoporosis and chronic fatigue in GD1 (n=2).

- III.

- Occurrence of complex phenotype due to another rare genetic disease (n=5, GD1).

- IV.

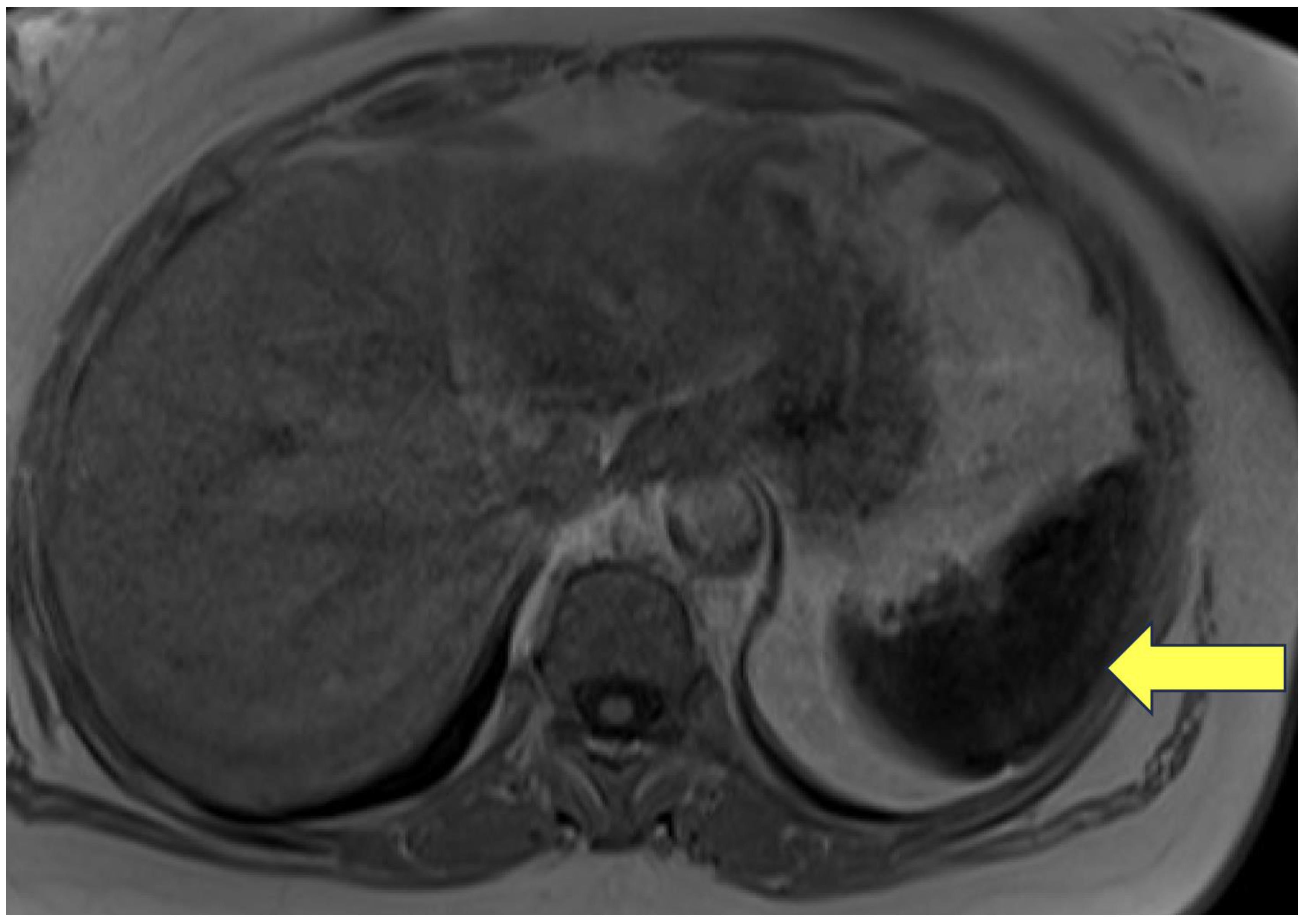

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (n=2, GD1).

- V.

- Myoclonic epilepsy (n=1, GD3).

- VI.

- Hyperferritinemia and iron overload (n=5, GD1).

- I.

- Unusual inflammatory symptoms due to concurrent FMF

- II.

- Myopathy and chronic fatigue

- III.

- Occurrence of complex phenotype due to a second, apparently unrelated genetic disease

- IV. ADPKD

- V. Myoclonic epilepsy

- VI.

- Hyperferritinemia and iron overload

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grabowski GA, Antommaria AHM, Kolodny EH, Mistry PK. Gaucher disease: Basic and translational science needs for more complete therapy and management. Mol Genet Metab. 2021;132(2):59-75. [CrossRef]

- Mistry PK, Cappellini MD, Lukina E, et al. A reappraisal of Gaucher disease—diagnosis and disease management algorithms. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(1):110-115. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski GA, Kolodny EH, Weinreb NJ, et al. Gaucher Disease: Phenotypic and Genetic Variation. (Valle D, Antonarakis S, Ballabio A, Beaudet A, Mitchell G, eds.). The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://ommbid.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2709§ionid=225546386.

- Sidransky E. Gaucher disease: insights from a rare Mendelian disorder. Discov Med. 2012;14(77):273-281.

- Sidransky E. Gaucher disease: complexity in a “simple” disorder. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83(1-2):6-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CK, Stein PB, Liu J, et al. Genome-wide association study of N370S homozygous Gaucher disease reveals the candidacy of CLN8 gene as a genetic modifier contributing to extreme phenotypic variation. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(4):377-383. [CrossRef]

- Velayati A, DePaolo J, Gupta N, et al. A mutation in SCARB2 is a modifier in gaucher disease. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(11):1232-1238. [CrossRef]

- Lo SM, Liu J, Chen F, et al. Pulmonary vascular disease in Gaucher disease: clinical spectrum, determinants of phenotype and long-term outcomes of therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(3):643-650. [CrossRef]

- Drelichman GI, Fernández Escobar N, Soberon BC, et al. Long-read single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing of GBA1 locus in Gaucher disease national cohort from Argentina reveals high frequency of complex allele underlying severe skeletal phenotypes: Collaborative study from the Argentine Group for Diagnosis and Treatment of Gaucher Disease. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2021;29:100820. [CrossRef]

- Lo SM, Choi M, Liu J, et al. Phenotype diversity in type 1 Gaucher disease: discovering the genetic basis of Gaucher disease/hematologic malignancy phenotype by individual genome analysis. Blood. 2012;119(20):4731-4740. [CrossRef]

- The International FMF Consortium. Ancient Missense Mutations in a New Member of the RoRet Gene Family Are Likely to Cause Familial Mediterranean Fever. Cell. 1997;90(4):797-807. [CrossRef]

- Aksentijevich I, Torosyan Y, Samuels J, et al. Mutation and Haplotype Studies of Familial Mediterranean Fever Reveal New Ancestral Relationships and Evidence for a High Carrier Frequency with Reduced Penetrance in the Ashkenazi Jewish Population. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 1999;64(4):949-962. [CrossRef]

- Lehtokari VL, Pelin K, Herczegfalvi A, et al. Nemaline myopathy caused by mutations in the nebulin gene may present as a distal myopathy. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2011;21(8):556-562. [CrossRef]

- Moreno CAM, Artilheiro MC, Fonseca ATQSM, et al. Clinical Manifestation of Nebulin-Associated Nemaline Myopathy. Neurol Genet. 2023;9(1). [CrossRef]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/95123/.

- Rabin R, Hirsch Y, Booth KTA, et al. ARSA Variant Associated With Late Infantile Metachromatic Leukodystrophy and Carrier Rate in Individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish Ancestry. Am J Med Genet A. Published online October 30, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Stein P, Yang R, Liu J, Pastores GM, Mistry PK. Evaluation of high density lipoprotein as a circulating biomarker of Gaucher disease activity. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(2):429-437. [CrossRef]

- Guo D chuan, Duan XY, Regalado ES, et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in YY1AP1 Lead to Grange Syndrome and a Fibromuscular Dysplasia-Like Vascular Disease. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2017;100(1):21-30. [CrossRef]

- Peterschmitt MJ, Freisens S, Underhill LH, Foster MC, Lewis G, Gaemers SJM. Long-term adverse event profile from four completed trials of oral eliglustat in adults with Gaucher disease type 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):128. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Elias A, Benito B. Ion Channel Disorders and Sudden Cardiac Death. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):692. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki T, Delgado-Escueta A V, Aguan K, et al. Mutations in EFHC1 cause juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):842-849. [CrossRef]

- de Nijs L, Wolkoff N, Coumans B, Delgado-Escueta A V., Grisar T, Lakaye B. Mutations of EFHC1, linked to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, disrupt radial and tangential migrations during brain development. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(23):5106-5117. [CrossRef]

- Stein P, Yu H, Jain D, Mistry PK. Hyperferritinemia and iron overload in type 1 Gaucher disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(7):472-476. [CrossRef]

- Yassin MA, Soliman AT, Desanctis V, Abusamaan S, Elsotouhy A, Aldewik N. Hereditary Hemochromatosis in an Adult Due to H63D Mutation: The Value of Estimating Iron Deposition By MRI T2* and Dissociation Between Serum Ferritin Concentration and Hepatic Iron Overload. Blood. 2014;124(21):4891-4891. [CrossRef]

- Duca L, Granata F, Di Pierro E, Brancaleoni V, Graziadei G, Nava I. Associated Effect of SLC40A1 and TMPRSS6 Polymorphisms on Iron Overload. Metabolites. 2022;12(10):919. [CrossRef]

- Hanson EH. HFE Gene and Hereditary Hemochromatosis: A HuGE Review. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(3):193-206. [CrossRef]

- Santos PCJL, Cançado RD, Pereira AC, et al. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Mutations in genes involved in iron homeostasis in Brazilian patients. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;46(4):302-307. [CrossRef]

- Posey JE, Harel T, Liu P, et al. Resolution of Disease Phenotypes Resulting from Multilocus Genomic Variation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(1):21-31. [CrossRef]

- Boddupalli CS, Nair S, Belinsky G, et al. Neuroinflammation in neuronopathic Gaucher disease: Role of microglia and NK cells, biomarkers, and response to substrate reduction therapy. Elife. 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Vardi A, Zigdon H, Meshcheriakova A, et al. Delineating pathological pathways in a chemically induced mouse model of Gaucher disease. J Pathol. 2016;239(4):496-509. [CrossRef]

- Mistry PK, Sirrs S, Chan A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in type 1 Gaucher’s disease: genetic and epigenetic determinants of phenotype and response to therapy. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;77(1-2):91-98. [CrossRef]

- ROBERTS WC, FREDRICKSON DS. Gaucher’s Disease of the Lung Causing Severe Pulmonary Hypertension with Associated Acute Recurrent Pericarditis. Circulation. 1967;35(4):783-789. [CrossRef]

- Nair S, Boddupalli CS, Verma R, et al. Type II NKT-TFH cells against Gaucher lipids regulate B-cell immunity and inflammation. Blood. 2015;125(8):1256-1271. [CrossRef]

- Pandey MK, Grabowski GA. Immunological Cells and Functions in Gaucher Disease. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18(3):197-220. [CrossRef]

- Lancieri M, Bustaffa M, Palmeri S, et al. An Update on Familial Mediterranean Fever. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9584. [CrossRef]

- Aflaki E, Moaven N, Borger DK, et al. Lysosomal storage and impaired autophagy lead to inflammasome activation in Gaucher macrophages. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):77-88. [CrossRef]

- Booty MG, Chae JJ, Masters SL, et al. Familial mediterranean fever with a single MEFV mutation: Where is the second hit? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(6):1851-1861. [CrossRef]

- Berkun Y, Eisenstein E, Ben-Chetrit E. FMF - clinical features, new treatments and the role of genetic modifiers: a critical digest of the 2010-2012 literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(3 Suppl 72):S90-5.

- Stirnemann J, Belmatoug N, Camou F, et al. A Review of Gaucher Disease Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):441. [CrossRef]

- LIDAR M, KEDEM R, BERKUN Y, LANGEVITZ P, LIVNEH A. Familial Mediterranean Fever in Ashkenazi Jews: The Mild End of the Clinical Spectrum. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(2):422-425. [CrossRef]

- Waldman S, Backenroth D, Harney É, et al. Genome-wide data from medieval German Jews show that the Ashkenazi founder event pre-dated the 14th century. Cell. 2022;185(25):4703-4716.e16. [CrossRef]

- Pandey MK, Burrow TA, Rani R, et al. Complement drives glucosylceramide accumulation and tissue inflammation in Gaucher disease. Nature. 2017;543(7643):108-112. [CrossRef]

- Pastores GM, Barnett NL, Bathan P, Kolodny EH. A neurological symptom survey of patients with type I Gaucher disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26(7):641-645. [CrossRef]

- Tsai L, Chien Y, Yang C, Hwu W. Myopathy in Gaucher disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31(S3):489-491. [CrossRef]

- Dalle S, Rossmeislova L, Koppo K. The Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Sewry CA, Laitila JM, Wallgren-Pettersson C. Nemaline myopathies: a current view. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2019;40(2):111-126. [CrossRef]

- González-Jamett A, Vásquez W, Cifuentes-Riveros G, Martínez-Pando R, Sáez JC, Cárdenas AM. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Connexin Hemichannels in Muscular Dystrophies. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2):507. [CrossRef]

- Lim JA, Li L, Raben N. Pompe disease: from pathophysiology to therapy and back again. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6. [CrossRef]

- Scott SA, Edelmann L, Liu L, Luo M, Desnick RJ, Kornreich R. Experience with carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for 16 Ashkenazi Jewish genetic diseases. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(11):1240-1250. [CrossRef]

- Emery A. Rare genetic disorders in certain populations. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2009;19(5):307. [CrossRef]

- Mistry PK, Liu J, Yang M, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene-deficient mouse recapitulates Gaucher disease displaying cellular and molecular dysregulation beyond the macrophage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(45):19473-19478. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom BE, Cappellini MD, Weinreb NJ, et al. Cancer risk and gammopathies in 2123 adults with Gaucher disease type 1 in the International Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(10):1337-1347. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Halene S, Yang M, et al. Gaucher disease gene GBA functions in immune regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(25):10018-10023. [CrossRef]

- Davies EH, Seunarine KK, Banks T, Clark CA, Vellodi A. Brain white matter abnormalities in paediatric Gaucher Type I and Type III using diffusion tensor imaging. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(2):549-553. [CrossRef]

- Natoli TA, Smith LA, Rogers KA, et al. Inhibition of glucosylceramide accumulation results in effective blockade of polycystic kidney disease in mouse models. Nat Med. 2010;16(7):788-792. [CrossRef]

- Gansevoort RT, Hariri A, Minini P, et al. Venglustat, a Novel Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitor, in Patients at Risk of Rapidly Progressing ADPKD: Primary Results of a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2/3 Randomized Clinical Trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2023;81(5):517-527.e1. [CrossRef]

- Nobakht N, Hanna RM, Al-Baghdadi M, et al. Advances in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Clinical Review. Kidney Med. 2020;2(2):196-208. [CrossRef]

- King JO. Progressive myoclonic epilepsy due to Gaucher’s disease in an adult. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38(9):849-854. [CrossRef]

- Park JK, Orvisky E, Tayebi N, et al. Myoclonic Epilepsy in Gaucher Disease: Genotype-Phenotype Insights from a Rare Patient Subgroup. Pediatr Res. 2003;53(3):387-395. [CrossRef]

- Rothwell JC, Obeso JA, Marsden CD. On the significance of giant somatosensory evoked potentials in cortical myoclonus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47(1):33-42. [CrossRef]

- Manganotti P, Tamburin S, Zanette G, Fiaschi A. Hyperexcitable cortical responses in progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology. 2001;57(10):1793-1799. [CrossRef]

- Garvey MA, Toro C, Goldstein S, et al. Somatosensory evoked potentials as a marker of disease burden in type 3 Gaucher disease. Neurology. 2001;56(3):391-394. [CrossRef]

- Thounaojam R, Langbang L, Itisham K, et al. EFHC1 mutation in Indian juvenile myoclonic epilepsy patient. Epilepsia Open. 2017;2(1):84-89. [CrossRef]

- Loucks CM, Park K, Walker DS, et al. EFHC1, implicated in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, functions at the cilium and synapse to modulate dopamine signaling. Elife. 2019;8. [CrossRef]

- Ciumas C, Wahlin TBR, Jucaite A, Lindstrom P, Halldin C, Savic I. Reduced dopamine transporter binding in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;71(11):788-794. [CrossRef]

- Regenboog M, van Kuilenburg ABP, Verheij J, Swinkels DW, Hollak CEM. Hyperferritinemia and iron metabolism in Gaucher disease: Potential pathophysiological implications. Blood Rev. 2016;30(6):431-437. [CrossRef]

- Allen MJ, Myer BJ, Khokher AM, Rushton N, Cox TM. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and the pathogenesis of Gaucher’s disease: increased release of interleukin-6 and interleukin-10. QJM. 1997;90(1):19-25. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(9):1271-1276. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz F, Pawłowicz E, Klimkowska M, et al. Ferritinemia and serum inflammatory cytokines in Swedish adults with Gaucher disease type 1. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2018;68:35-42. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre T, Reihani N, Daher R, et al. Involvement of hepcidin in iron metabolism dysregulation in Gaucher disease. Haematologica. 2018;103(4):587-596. [CrossRef]

- Kesner JS, Chen Z, Shi P, et al. Noncoding translation mitigation. Nature. 2023;617(7960):395-402. [CrossRef]

| Concomitant Genetic Disorder | Number of Cases |

| Familial Mediterranean Fever | 4 |

| Nemaline Myopathy | 2 |

| Metachromatic Leukodystrophy | 1 |

| Fibromuscular Dysplasia | 1 |

| Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Syndrome | 2 |

| Myoclonic Epilepsy | 1 |

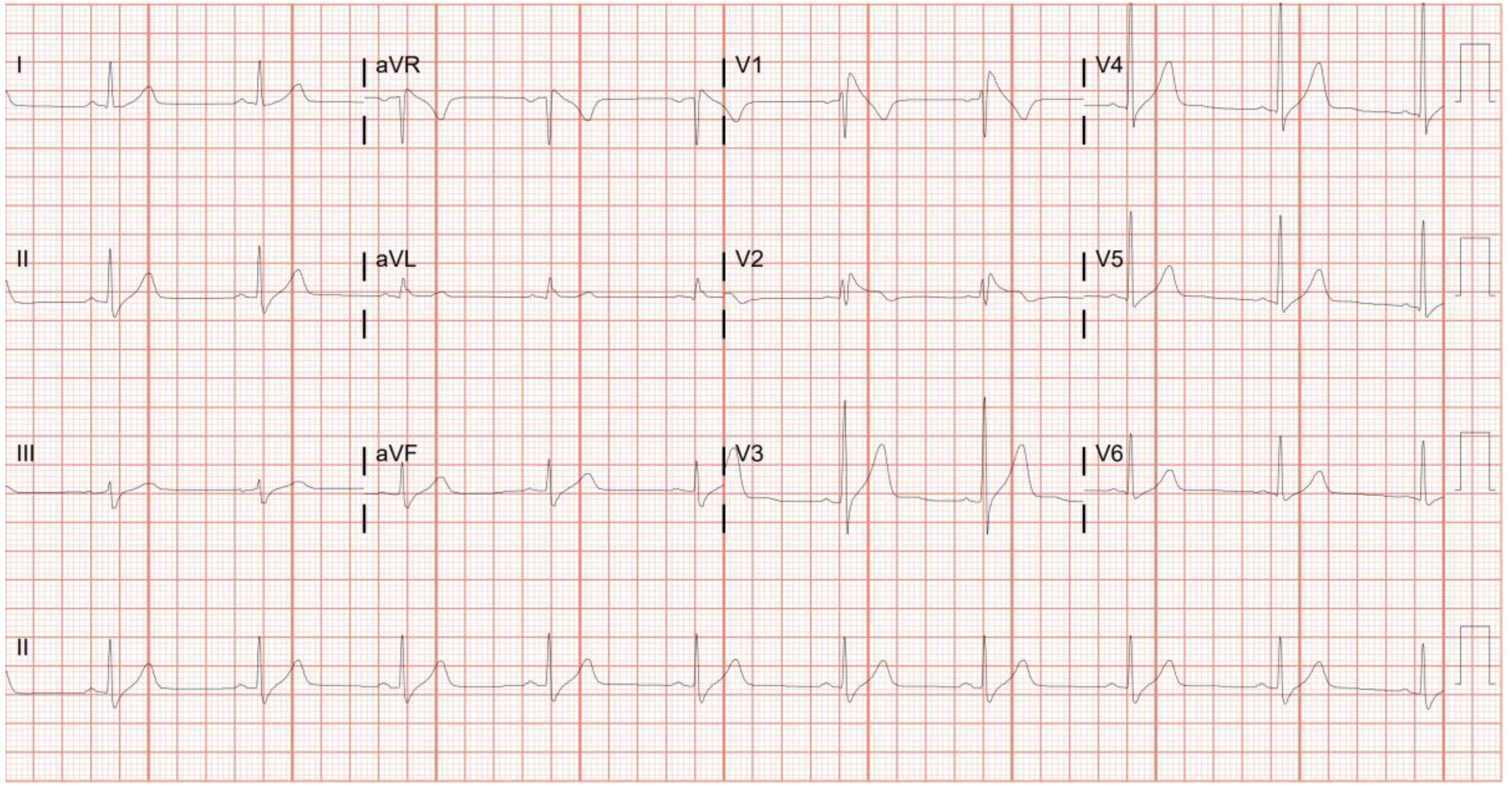

| Brugada syndrome | 1 |

| Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease | 2 |

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis | 5 |

| Demographic | Complex phenotype GD (N=18) | Total cohort (N=275) |

| Age (years) [Mean (Range)] | 42.4 (11-73) | 46.4 (1-94) |

| Gender (Female) N (%) | 18 (55.5) | 142 (51.6) |

| GBA1 genotype (p.Asn409Ser/p.Asn409Ser) N (%) | 11 (61.1) | 151 (54.9) |

| Splenectomy N (%) | 0 (0) | 15 (5.4) |

| ERT N (%) | 9 (50) | 133 (48.4) |

| SRT N (%) | 9 (50) | 107 (38.9) |

| Untreated N (%) | 0 (0) | 39 (14.2) |

| Disease | Patient | Gene | Mutation | Amino Acid Change | Type | Zygosity | SIFT | MAF | ASJ-MAF | PolyPhen | Yale GD Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familial Mediterranean Fever | Patient 1 | MEFV | rs1231123 | p.Asp424Lys | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated (0.34) | 0.3744 | 0.4184 | possibly damaging(0.631) | 0.63 |

| Patient 2 | MEFV | rs28940579 | p.Val726Ala | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated(1) | 0.002167 | 0.0421 | benign(0.06) | 0.07 | |

| Patient 3 | MEFV | rs28940579 | p.Val726Ala | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated(1) | 0.002167 | 0.0421 | benign(0.06) | 0.07 | |

| Patient 4 | MEFV | rs1231123 | p.Asp424Lys | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated (0.34) | 0.3744 | 0.4184 | possibly damaging(0.631) | 0.63 | |

| Nemaline Myopathy | Patient 5 | NEB | rs750810441 | p.Asp5398Asn | Coding | Heterozygous | NA | 0.002193 | 0.0115 | unknown(0) | 0.01 |

| Patient 6 | NEB | rs201825451 | p.Asp8345= | Coding | Heterozygous | NA | 0.00157 | 0.017 | NA | 0.03 | |

| Metachromatic Leukodystrophy | Patient 7 | ARSA | rs867538940 | p.Arg60Trp | Coding | Homozygous | deleterious(0.03) | 5.82E-06 | 0 | probably damaging(0.989) | 0.01 |

| Fibromuscular Dysplasia | Patient 8 | YY1AP1 | rs41264945 | p.Gln242 | Coding | Heterozygous | deleterious(0) | 0.03638 | 0.0308 | probably damaging(0.999) | 0.04 |

| Brugada Syndrome | Patient 9 | CACNB2 | rs875989812 | NA | Splice acceptor | Heterozygous | NA | 0.0006187 | 0.0026 | NA | 0.007 |

| Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency | Patient 10 | MSH6 | c.2822dupA | NA | Frame-shift | Homozygous | deleterious(0) | 0 | 0 | probably damaging(0.999) | 0.008 |

| Patient 11 | MSH6 | c.2822dupA | NA | Frame-shift | Homozygous | deleterious(0) | 0 | 0 | probably damaging(0.999) | 0.008 | |

| ADPKD | Patient 12 | PKD1 | rs138575342 | p.Pro694Leu | Coding | Heterozygous | deleterious(0) | 0.02435 | 0 | probably damaging(0.993) | 0.037 |

| Patient 13 | PKD1 | rs1282668884 | p.Arg4150Cys | Coding | Heterozygous | deleterious(0) | NA | 0 | probably damaging(1) | 0 | |

| Myoclonic Epilepsy | Patient 14 | EFHC1 | rs1570624 | p.Arg294His | Coding | Heterozygous | deleterious(0) | 0.01005 | 0.0043 | probably damaging(0.999) | 0.02 |

| Hemochromatosis | Patient 5 | HFE | rs1799945 | p.His63Asp | Coding | Homozygous | tolerated(0.09) | 0.1092 | 0.1208 | possibly damaging(0.704) | 0.22 |

| SLC40A1 | rs2304704 | p.Val221= | Splice site | Homozygous | NA | 0.6286 | 0.7137 | NA | 0.89 | ||

| SLC40A1 | rs1439816 | NA | Non-coding | Homozygous | NA | 0.7967 | 0.8192 | NA | 0.96 | ||

| Patient 15 | HFE | rs1800562 | p.Cys282Tyr | Coding | Heterozygous | deleterious(0) | 0.03321 | 0.0138 | possibly damaging(0.509) | 0.06 | |

| SLC40A1 | rs2304704 | p.Val221= | Splice site | Homozygous | NA | 0.6286 | 0.7137 | NA | 0.89 | ||

| SLC40A1 | rs1439816 | NA | Non-coding | Homozygous | NA | 0.7967 | 0.8192 | NA | 0.96 | ||

| Patient 16 | HFE | rs1799945 | p.His63Asp | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated(0.09) | 0.1092 | 0.1208 | possibly damaging(0.704) | 0.22 | |

| SLC40A1 | rs1439816 | NA | Non-coding | Heterozygous | NA | 0.7967 | 0.8192 | NA | 0.96 | ||

| SLC40A1 | rs11568351 | NA | Non-coding | Heterozygous | NA | 0.168 | 0.1275 | NA | 0.28 | ||

| SLC40A1 | rs13008848 | NA | Non-coding | Heterozygous | NA | 0.1655 | 0.1252 | NA | 0.27 | ||

| Patient 17 | HFE | rs1799945 | p.His63Asp | Coding | Heterozygous | tolerated(0.09) | 0.1092 | 0.1208 | possibly damaging(0.704) | 0.22 | |

| SLC40A1 | rs2304704 | p.Val221= | Splice site | Homozygous | NA | 0.6286 | 0.7137 | NA | 0.89 | ||

| SLC40A1 | rs1439816 | NA | Non-coding | Homozygous | NA | 0.7967 | 0.8192 | NA | 0.96 | ||

| Patient 18 | SLC40A1 | rs2304704 | p.Val221= | Splice site | Homozygous | NA | 0.6286 | 0.7137 | NA | 0.89 | |

| SLC40A1 | rs1439816 | NA | Non-coding | Homozygous | NA | 0.7967 | 0.8192 | NA | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).