1. Introduction

World Health Organization estimates that 5 - 14% of patients with diabetes have latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) [

1,

2]. It is described that subjects with LADA have intermediate features between type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). LADA is characterized by slower autoimmune destruction of the β-cells compared to T1D, where glutamate decarboxylase autoantibodies (GADA) are the predominant serum marker [

3,

4]. This autoimmune process results in progressive hyperglycemia, and thus, patients with LADA do not require insulin therapy at the onset of diabetes[

5]. On the other hand, the etiology of LADA involves insulin resistance. As with T2D, the risk of LADA is modified by lifestyle factors such as body mass index and physical activity [

6]. Moreover, the initial clinical presentation of LADA resembles that of T2D. Consequently, patients with LADA are initially diagnosed with T2D, and they receive inadequate therapies for their diabetes until insulin dependence develops [

5,

7].

Buzzetti et al. (2020) suggest that the phenotype of LADA is heterogeneous with some patients similar to T1D and others indistinguishable from T2D [

8]. There are variations in the phenotype of LADA between populations, such as populations from Europe, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen have intermediate features between T1D and T2D [

9,

10,

11]. Nonetheless, in Chinese populations, LADA has similar insulin resistance compared to T2D, and less serum GADA levels [

12,

13]. The variations in the phenotype of LADA suggest that differences between populations could be attributed to genetic risk factors. In this sense, LADA has genetic traits that interact with the environmental factors of T1D and T2D [

6]. The genetic risk factors together with non-genetic factors of LADA could influence the rate of β-cell destruction and thus lead to a heterogenous clinical presentation [

14]. Our knowledge is that only one GWAS of LADA has been conducted in a European population; in this study, they found 5 polymorphisms in LADA (genes HLA-DQB1, PTPN22, INS, and SH2B3), these SNPs are related to T1D [

15]. In the Chinese Han population, Song et al (2024) associated LADA and T1D with an RPS26 variant in a case-control study [

16]. On the other hand, Mendelian randomization studies in the European population associated lifestyle risk factors in LADA with risk genotypes related to T2D (FTO and TCF7L2) [

17,

18]. In this sense, more studies are necessary to comprehend the genetics of LADA better. However, information about risk genotypes of LADA in non-European populations, including Latin American populations, is scarce. Genetic studies in the Latin American population could reveal LADA risk factors unique to this population. Therefore, this study aims to perform a GWAS with phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) of LADA of a population of patients with LADA from a hospital in southeastern Mexico and a biobank of the Mexican population.

2. Results

A total of 51 phenotypes were evaluated in our PheWAS analysis, which identified 981 SNPs associated with these phenotypes (p < 5x10-5). The associations are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

In the case-control GWAS analysis for LADA and population-based controls, no genome-wide significant association was found. Still, we observed 8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated at the nominal level (p-value < 1x10-5) (Supplementary Figure 1). Five SNPs are intronic in the LIFR and HDAC9 genes, two are intergenic variables, and one is located downstream of the TMEM20 gene (Supplementary Table 2).

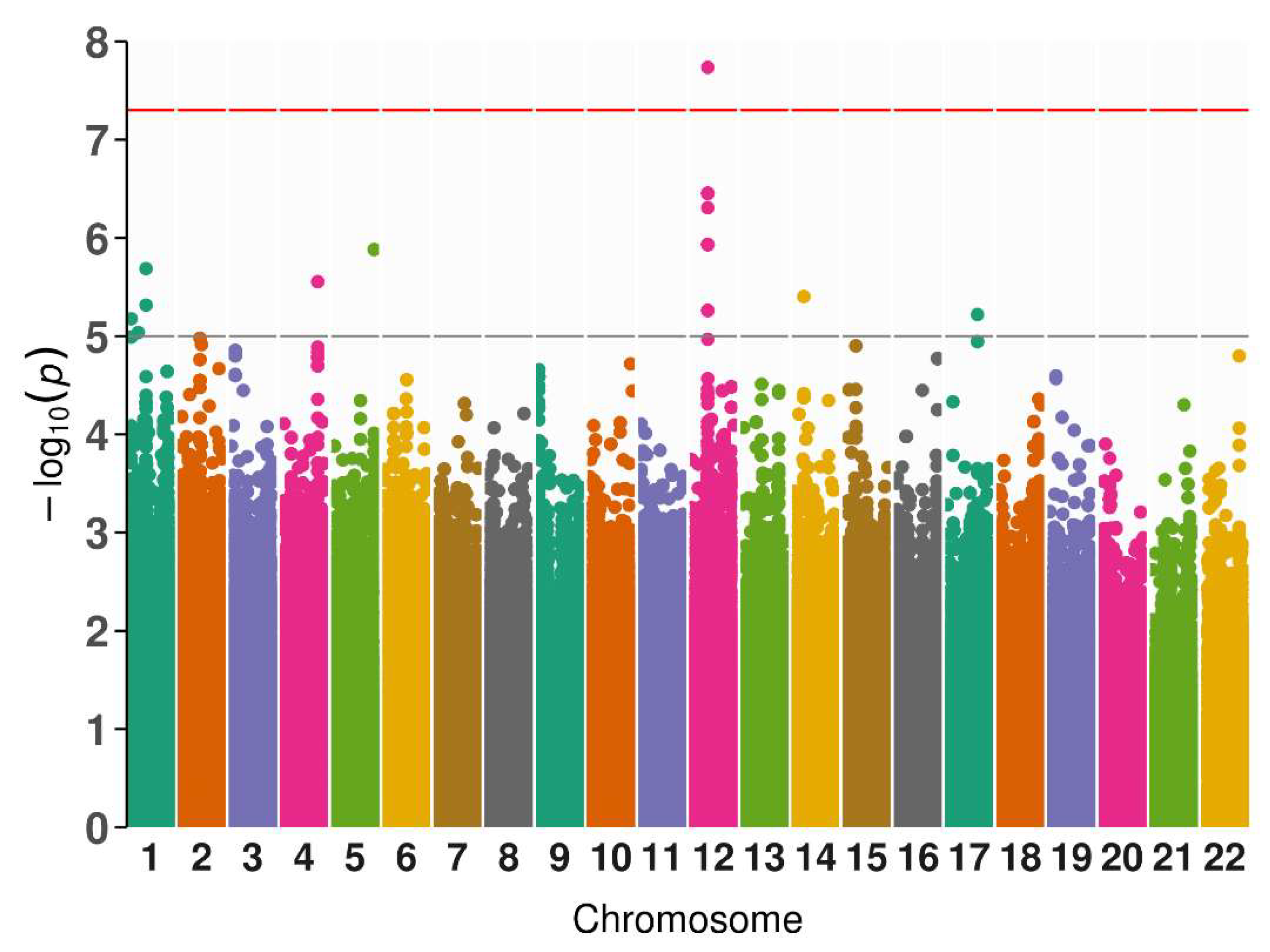

In LADA cases (n=50), we associated GADA levels and one polymorphism with genome-wide significance (p < 5x10

-8). Likewise, we found 25 more variants associated with GADA levels at nominal significance (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1 presents significant polymorphisms associated with phenotypic features in patients with LADA (diabetes onset, height, and hypertension onset).

The SNP is rs7305229, a downstream variant of the FAIM2 gene (p = 1.84x10

-8, β = -1.27, SE = 0.18 and MAF = 0.22).

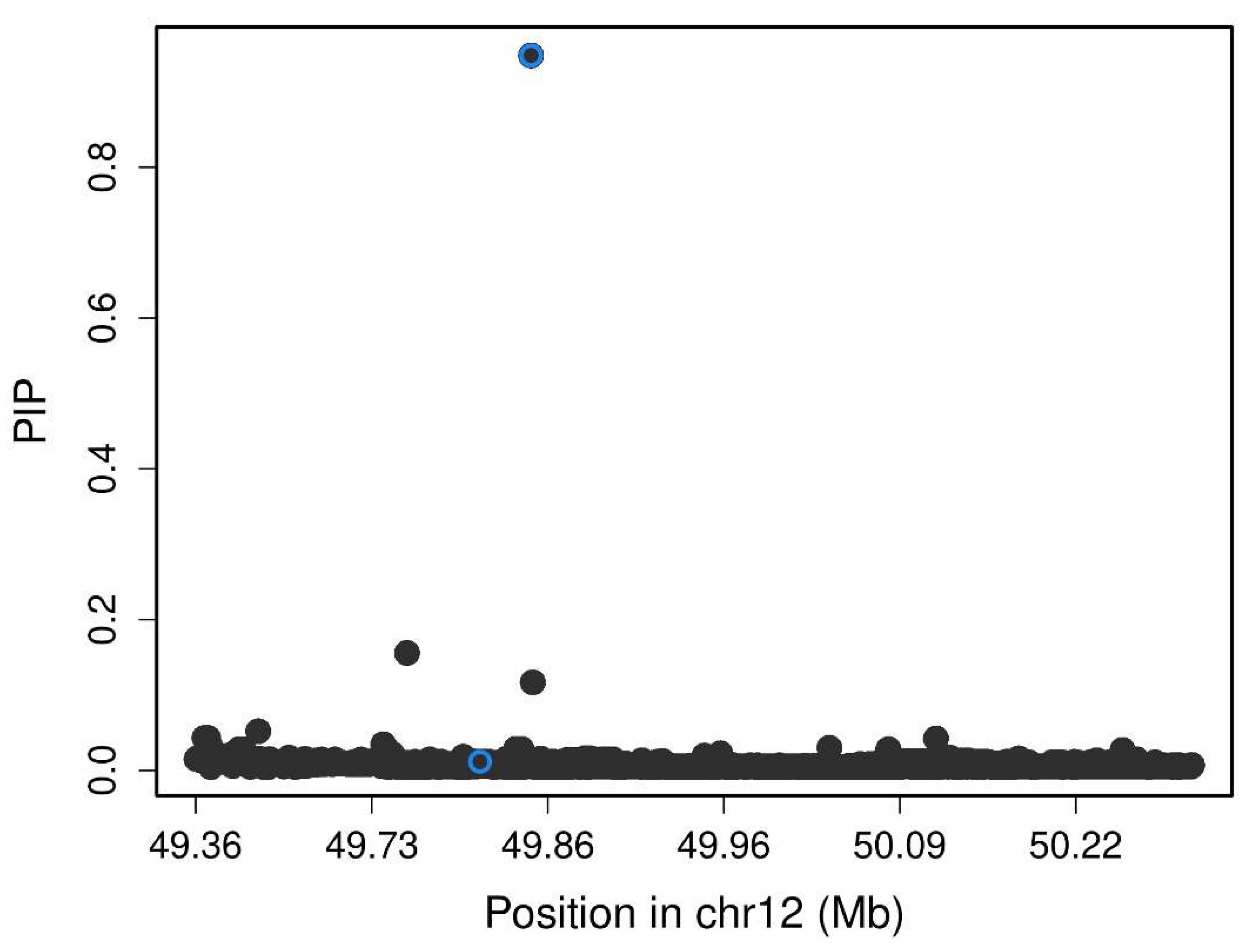

Figure 1 includes the Manhattan plot for the GADA genome-wide associations. After, we performed a fine mapping of rs7305229 locus, including all SNPs within 1Mb.

Figure 2 shows that the polymorphism rs7305229 had a 94.8% posterior inclusion probability of being causal for the GADA levels phenotype, the greatest posterior probability.

We realized a PheWAS with the GWAS Atlas database, which found 41 traits of the metabolic domain associated with rs7305229 (p < 5x10-8). Bioelectrical impedance-related measures and body mass index were frequently associated with rs7305229. Other traits related to this SNP were salt consumption, age at menarche, and bone mineral density. Notably, we did not find an association between rs7305229 and the immunological domain (p > 1x10-5) (Supplementary Table 3).

The rs7305229 was associated with GADA levels in our population and with BMI in the GWAS Atlas database. Thus, we performed a conditional analysis to identify possible dependent associations. The linear model between the normalized values of both traits showed no association (R2=0.026, p=0.262). Besides, the second genome-wide analysis had changes in comparison to the first analysis (p = 6.97x10-8, β = -1.26, SE = 0.19).

3. Discussion

We explored GWAS associations in multiple phenotypes in individuals diagnosed with LADA from Southern Mexico, we showed that rs7305229 is associated with GADA antibody levels.

In the comparison between LADA cases and population-based controls, we identified associations with the LIFR (leukemia inhibitory factor receptor) gene. These associated SNPs of LIFR are intronic variants, and they probably change expression levels rather than alter their protein structure. In addition, LIFR is a transmembrane receptor that binds to IL-6 family members, including leukemia inhibitory factor and oncostatin-M [

19]. LIFR is involved in lipolysis, adipose inflammation, hepatic triacylglycerol accumulation, and insulin resistance in mouse models [

20,

21]. Literature remarks that 56% of patients with T2D have NAFLD [

22]. In the context of the changes in LIFR expression could be related to susceptibility to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and insulin resistance in patients with LADA, and the LIFR/JAK/STAT3 inflammatory pathway enhances adipocyte lipolysis [

21]. Although, the evidence on subjects with LADA is scarce; a study of hospitalized patients in China reported that 24.6% of individuals with LADA had NAFLD [

23]. In our population, we found fewer patients with LADA and NAFLD than with T2D and NAFLD; nonetheless, the risk for NAFLD in patients with LADA could be greater than in healthy subjects [

24].

We associated a total of 981 SNP with nominal associations in different phenotypes, the phenotypes with more associations were age of hypertension onset (n=244), BMI (n=88), insulin doses (n=74), and cholesterol levels (n=67). Notably, these phenotypes resemble the metabolic syndrome criteria [

25]. In addition, the LADA genetic constitution has polymorphisms associated with metabolic syndrome [

14,

15].

Our PheWAS identified a GWAS significant association with a 3’UTR genetic variant (rs7305229) located downstream of the FAIM2 gene (Fas apoptotic inhibitory molecule 2) with plasmatic GADA antibody levels in patients diagnosed with LADA. Polymorphisms of FAIM2 are associated with childhood obesity, autoimmune thyroid disease, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [

26,

27,

28]. Besides, FAIM2 expression is associated with lymphocyte CD8+ antitumor activity. The FAIM2 protein protects from cell death induced by Fas and plays an important role in calcium balance in the endoplasmic reticulum [

29]. Concerning that, FAIM2 KO mouse models showed increased apoptosis of newly activated T lymphocytes; this evidence suggests that FAIM2 protects the T cells from apoptosis, as the first days of a cytotoxic response are hostile for memory T cells [

30].

We employed the GWAS Atlas data to perform a second PheWAS to compare our observations with previous results from other populations. Notably, this second PheWAS showed that SNP rs7305229 has not been associated with immunologic traits. Instead, this SNP is mainly associated with metabolic traits. In this sense, FAIM2 is mainly expressed in nervous system tissues [

29]. Remarkably, Littleton et al. (2024) reported that variants of FAIM2 in 3’UTR change expression levels and influence neuronal populations in mouse models. They propose that expression of FAIM2 is required for the normal development of anorexigenic neurons in the hypothalamus; however, individuals with less expression would have fewer anorexigenic neurons and thus increased appetite [

27].

There is limited evidence on the effect of genetic variations of FAIM2 on GADA antibodies, even though GADA is present in other autoimmune disorders. In this sense, GADA antibodies are detectable in some individuals with Graves' disease; furthermore, these subjects with GADA can develop T1D [

31,

32]. Notably, a study associated a SNP of FAIM2 with antibody levels in patients with Graves’ disease [

28]. Nonetheless, other variants of FAIM2 in the 3’UTR region are associated with obesity and body adiposity in other GWAS [

33,

34]. Nevertheless, we did not find associations between BMI with GADA and rs7305229. Littleton et al. (2024) propose that subjects with fewer anorexigenic POMC neurons would have reduced expression of FAIM2, induce increased appetite, and higher risk of becoming overweight in childhood [

27]. Interestingly, evidence shows that childhood obesity genetics are a risk factor for diabetes regardless of autoimmunity or insulin resistance [

35]. In addition, high BMI is a risk factor for childhood type 2 diabetes and latent autoimmune diabetes in youth [

36]. Furthermore, obesity in childhood also is a risk factor in adult age for T2D and LADA [

37].

We hypothesize that our subjects with LADA and rs7305229 would have lower GADA antibody levels. Likewise, other SNPs of the FAIM2 gene could produce increased BMI and thus, a high risk of diabetes. BMI and GADA antibody levels are heterogeneous features among patients with LADA: some individuals have high antibody levels and low BMI, while others have low antibody levels and high BMI [

14]. In this regard, Caucasian patients with LADA have a greater proportion of high antibody levels than Chinese subjects with LADA. Conversely, metabolic syndrome is more frequent in the Caucasian population than in the Chinese individuals. Another difference is insulin resistance; LADA has similar resistance to T2D in the Chinese population, but in Caucasian patients, it is less pronounced than in T2D [

12]. Our population showed low antibody levels, high frequency of metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance like T2D. The variability of clinical features of LADA would reflect the differences in genetic and environmental risk factors among individuals and populations [

14].

We know, this is the first GWAS of LADA performed in the Mexican population; nevertheless, it has some limitations. First, all subjects with LADA were from a single care center in Southeastern Mexico. In addition, the healthy subjects’ genotypes were from a nationwide database, which limited the comparison between phenotypical features. The sample size of our study is small, and we do not have a replication cohort, reducing our statistical power. Although using the subpopulation from Southeast Mexico limited the sample size, our GWAS was well controlled, as reflected in our lambda values.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Population

We included a subsample of 59 deeply phenotyped individuals diagnosed with LADA from a previous study [

24]. These subjects attend the Diabetes Clinic of the Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad “Dr. Gustavo A. Rovirosa Pérez” from January 2020 to May 2021. The hospital cares for patients from Chiapas, Veracruz, and Tabasco (Southeast Mexico). A diabetologist evaluated all recruited subjects. We included individuals who met the following criteria: Mexican descent, older than 30 years at the time of diabetes diagnosis, more than six months without insulin treatment after diagnosis, and positivity to GADA determined by ELISA (≥ 5 UI/mL). We followed the ethical principles from the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the High Specialization Regional Hospital “Dr. Gustavo A. Rovirosa Pérez” (HR/ENS/ARM/8073/2023; July 5th, 2023). They received verbal and written information about this study. Every patient participated voluntarily without receiving remuneration and signed an informed consent.

We also included a population-based control sample from the Mexican Genomic Database for Addiction Research (MxGDAR/Encodat) [

38]. Creation of the MxGDAR/ENCODAT database was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (CEI/C/083/2015) and the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (01/2017/I). This study was derived from the Mexican National Survey of Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drug Use. Subjects from the 32 states in Mexico were sampled, and regions where more than half of the population speaks a Native American language were excluded. We included 3121 individuals who met the following inclusion criteria: Mexican descent, older than 18 years, without self-reported diabetes or other comorbidities.

4.2. Phenotypic Characterization

A structured questionnaire was applied to recruited patients with LADA, we collected sociodemographic data (age, gender, education, marital status, socioeconomic status). Family history, age at diabetes diagnosis, diabetes complications, comorbidities, and pharmacotherapy were retrieved from clinical records. We measured weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Fasting glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triacylglycerols were determined from blood serum. GADA antibody levels were detected with an ELISA kit (MyBioSource, USA). A total of 51 phenotypes were evaluated.

4.3. Microarrays Analysis

We extracted DNA from whole blood samples using a salting-out procedure with the Puregene Blood kit (Qiagen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was hybridized with the Infinium Psycharray Beadchip (Illumina, USA) following the automated protocol. All genotyping procedures were performed in the Unidad de Alta Tecnología para Expresión y Microarreglos of the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica. The microarray analysis was similar to the population-based controls from the MxGDAR database, as previously described [

38].

4.4. Genotype Quality Control

Quality control of genotypes was performed with PLINK 1.9 version b7.1 [

39]. We excluded genetic variants with call rate < 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 05, p-value <1e-10 for a chi-squared test for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for cases and p < 1e

-06 for controls, and chimeric alleles (AT and CG). Individuals were excluded if they had a call rate < 95% for all the genetic variants and ± 3 standard deviations from the mean heterozygosity rate. We calculate the identity-by-state of all sample pairs to identify genetic relatedness. Pairs of individuals with pi-hat > 0.2 were selected, and related individuals with lower genotyping rates were excluded. Using this threshold, we kept 59 individuals diagnosed with LADA and 3086 population-based controls for further analysis.

4.5. Population Stratification

We used the pcair function of the GENESIS package version 2.30 for R version 4.2 to estimate principal components analysis (PCA) to evaluate population stratification. We included independent SNPs filtered by linkage disequilibrium pruning (threshold: 0.1, slide size: 106). Nonetheless, the population analysis showed the previously reported differences between the Southeast and other regions of Mexico [

40]. As previously described, the population from the South of Mexico could have a genetic structure different from that of the country's center [

38]. To avoid effects in our statistical tests for population stratification, we cluster cases and controls. We visualize the potential clustering of subpopulations inside our sample with Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) using the first 5 principal components (PCs). Two clusters were observed: one group with individuals from various regions of Mexico (cases n=12, controls n=2592), and the other with subjects mainly from Southeastern Mexico (cases n=50, controls n=491). The subpopulation that had the most cases from our LADA sample was selected. (Supplementary

Figure 2)

4.6. Genotype Imputation

We performed the imputation of autosomal genetic variants using the TOPMed Imputation Server with the TOPMed-r2 reference panel [

41]. We used the following parameters as post-imputation quality control, keeping those genetic variants with MAF > 0.05, quality score (R

2) > 0.7, and chi-squared p > 1x10

-6 for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. After quality control, we kept 5,797,363 genetic variants for the following analysis.

4.7. Phomene-Wide Association Study (PheWAS)

GENESIS package for R was employed to perform a case-control GWAS of LADA (n=50) versus controls (n=491), including the first 5 PCs, sex, and age as covariates. The statistic inflation factor (λ) was 1.082. Also, we performed genome-wide linear regressions between SNPs and phenotypic features of LADA cases with PLINK 1.9; covariates for this analysis were the first 2 PCs, sex, and age. Included phenotypes were continuous variables (anthropometric measures, biochemical measures, antibody levels, and years of disease evolution). Categorical variables were excluded from PheWAS as they had poor quality control results. A p-value < 5x10-8 was considered genome-wide significant and a p-value < 1x10-5 was nominally significant for both analyses. QQ plots and Manhattan plots were realized with ggplot2 and fastman libraries for R.

4.8. Fine Mapping

We used the susieR package version 0.12.35 for R version 4.2 was employed to perform a fine mapping for the associated loci using the summary statistics that showed GWAS significance. A 1000 kb window around the top genetic variant was selected as a significant locus. The LDlinkR package for R was employed to acquire the LD correlation matrix from the LDlink web application, we used the Mexican Ancestry from Los Angeles (MXL) population as a reference [

42]. Genetic variants with 95% posterior inclusion probability (PIP) were considered part of the credible set.

4.9. PheWAS Analysis

To find associations of SNPs with phenotypes in previous GWAS, the GWAS Atlas website was employed for PheWAS analysis of the nominally significant SNP. Associations with p-value <5x10-8 were considered significant.

4.10. Conditional Analysis

We realized a conditional analysis to identify phenotypes dependently associated with significant GWAS loci. For patients with LADA, a second genome-wide analysis was performed with PLINK 1.9 [

43]. This analysis included body mass index as a covariant for the significant GWAS loci. Also, a linear model for body mass index and GADA levels was calculated with R.

5. Conclusions

We performed a phenome-wide association study of LADA in subjects from southeastern Mexico, and the results indicated that rs7305229 was associated with GADA antibody levels. These findings contribute to understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying LADA, as its heterogeneity among individuals may be reflected in their genetic constitutions. Because the genetic risk factors for LADA may vary among populations, it is necessary to expand research in this area.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Manhattan plot and QQ plot of GWAS comparing LADA vs controls; Figure S2: Population stratification in the principal component analysis and UMAP; Table S1: PheWAS associations with evaluated traits in patients with LADA; Table S2: Significant variants in GWAS analysis; TableS3: Results of the PheWAS of rs7305229 performed with GWAS Atlas database.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E.J.-R. and A.D.G.-M.; methodology, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M. and A.D.G.-M.; software, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M. and D.R.-R.; validation, J.J.M.-M., C.A.T.-Z. and H.N.; formal analysis, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M. and D.R.-R.; investigation, G.A.N.-R., E.R.-S. and J.D.C.-C.; resources, I.E.J.-R., E.R.-S., H.N. and A.D.G.-M.; data curation, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M., J.A.V.-V., M.N.B.-G. and M.E.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M. and I.E.J.-R.; writing—review and editing, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M., I.E.J.-R., C.A.T.-Z. and A.D.G.-M.; visualization, G.A.N.-R., J.J.M.-M., J.D.C.-C and A.D.G.-M.; supervision, I.E.J.-R.; project administration, I.E.J.-R. and E.R.-S.; funding acquisition, H.N. and A.D.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of High Specialization Regional Hospital “Dr. Gustavo A. Rovirosa Pérez” (HR/ENS/ARM/8073/2023; July 5th, 2023). Creation of the MxGDAR/ENCODAT database was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (CEI/C/083/2015) and the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (01/2017/I).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of the MxGDAR/ENCODAT database can be found in the European Variation Archive (EVA) with the ID PRJEB37766. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the Unidad de Alta Tecnología para Expresión y Microarreglos of the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica for their technical support. The authors also thank CONAHCYT for supporting Germán Alberto Nolasco-Rosales (CVU 1005141), David Ruiz-Ramos (CVU 888651), and Juan Daniel Cruz-Castillo (CVU 1043199) with the National Scholarship for Postgraduate Studies; they are students of the Doctorate in Biomedical Sciences degree at the Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. This work was supported by the Kavli Institute for Neuroscience at Yale University's Kavli Postdoctoral Award for Academic Diversity to Jose Jaime Martinez-Magaña.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramu, D.; Ramaswamy, S.; Rao, S.; Paul, S.F.D. The worldwide prevalence of latent autoimmune diabetes of adults among adult-onset diabetic individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2023, 82, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Classification of diabetes mellitus; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2023, 47, S20–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zou, H.; Xie, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, Y. Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA): From Immunopathogenesis to Immunotherapy. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, V.; Ahmed, A.; Anjankar, A. A Review on Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults. Cureus 2023, 15, e47915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, S. Lifestyle or Environmental Influences and Their Interaction With Genetic Susceptibility on the Risk of LADA. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Luo, S.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Z. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: a focus on β-cell protection and therapy. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, R.; Tuomi, T.; Mauricio, D.; Pietropaolo, M.; Zhou, Z.; Pozzilli, P.; Leslie, R.D. Management of Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults: A Consensus Statement From an International Expert Panel. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zubairi, T.; Al-Habori, M.; Saif-Ali, R. Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA) and its Metabolic Characteristics among Yemeni Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2021, 14, 4223–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawa, M.I.; Kolb, H.; Schloot, N.; Beyan, H.; Paschou, S.A.; Buzzetti, R.; Mauricio, D.; De Leiva, A.; Yderstraede, K.; Beck-Neilsen, H.; et al. Adult-Onset Autoimmune Diabetes in Europe Is Prevalent With a Broad Clinical Phenotype. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddaloni, E.; Lessan, N.; Al Tikriti, A.; Buzzetti, R.; Pozzilli, P.; Barakat, M.T. Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults in the United Arab Emirates: Clinical Features and Factors Related to Insulin-Requirement. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0131837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, S.; Zhou, Z. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults in China. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Ji, L.; Jia, W.; Ning, G.; Huang, G.; Yang, L.; Lin, J.; Liu, Z.; Hagopian, W.A.; et al. Frequency, Immunogenetics, and Clinical Characteristics of Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in China (LADA China Study): A Nationwide, Multicenter, Clinic-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes 2013, 62, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzetti, R.; Maddaloni, E.; Gaglia, J.; Leslie, R.D.; Wong, F.S.; Boehm, B.O. Adult-onset autoimmune diabetes. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousminer, D.L.; Ahlqvist, E.; Mishra, R.; Andersen, M.K.; Chesi, A.; Hawa, M.I.; Davis, A.; Hodge, K.M.; Bradfield, J.P.; Zhou, K.; et al. First Genome-Wide Association Study of Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults Reveals Novel Insights Linking Immune and Metabolic Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2396–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Xie, L.; Ding, J.; Chen, Y.; Zou, H.; Pang, H.; Peng, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Association of gene polymorphism with different types of diabetes in Chinese individuals. Journal of Diabetes Investigation 2024, 15, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, R.; Ahlqvist, E.; Andersson, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Carlsson, P.-O.; Grill, V.; Groop, L.; Martinell, M.; Sørgjerd, E.P.; Tuomi, T.; et al. Physical Activity, Genetic Susceptibility, and the Risk of Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults and Type 2 Diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020, 105, e4112–e4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfvenborg, J.E.; Ahlqvist, E.; Alfredsson, L.; Andersson, T.; Dorkhan, M.; Groop, L.; Tuomi, T.; Wolk, A.; Carlsson, S. Genotypes of HLA, TCF7L2, and FTO as potential modifiers of the association between sweetened beverage consumption and risk of LADA and type 2 diabetes. European Journal of Nutrition 2020, 59, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikelonis, D.; Jorcyk, C.L.; Tawara, K.; Oxford, J.T. Stüve-Wiedemann syndrome: LIFR and associated cytokines in clinical course and etiology. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2014, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.L.; Hang, H.; Boudreau, A.; Elks, C.M. Oncostatin M Induces Lipolysis and Suppresses Insulin Response in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Gupta, A.; Yu, J.; Granados, J.Z.; Gandhi, A.Y.; Evers, B.M.; Iyengar, P.; Infante, R.E. LIFR-alpha-dependent adipocyte signaling in obesity limits adipose expansion contributing to fatty liver disease. iScience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.W.-S.; Ekstedt, M.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. Journal of Hepatology 2023, 79, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.P.; Zhao, C.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Lu, J.X.; Li, L.X.; Jia, W.P. [The relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome in patients with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2018, 98, 2398–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Rosales, G.A.; Ramírez-González, D.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Ávila-Fernandez, Á.; Villar-Juarez, G.E.; González-Castro, T.B.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Guzmán-Priego, C.G.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Ble-Castillo, J.L.; et al. Identification and phenotypic characterization of patients with LADA in a population of southeast Mexico. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.-C.; James, W.P.T.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.D.; Askland, K.D.; Barlassina, C.; Bellodi, L.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Black, D.; Bloch, M.; Brentani, H.; Burton, C.L.; Camarena, B.; et al. Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive–compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleton, S.H.; Trang, K.B.; Volpe, C.M.; Cook, K.; DeBruyne, N.; Maguire, J.A.; Weidekamp, M.A.; Hodge, K.M.; Boehm, K.; Lu, S.; et al. Variant-to-function analysis of the childhood obesity chr12q13 locus implicates rs7132908 as a causal variant within the 3′ UTR of <em>FAIM2</em>. Cell Genomics 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, B.; Borysewicz-Sańczyk, H.; Wawrusiewicz-Kurylonek, N.; Aversa, T.; Corica, D.; Gościk, J.; Krętowski, A.; Waśniewska, M.; Bossowski, A. Analysis of Polymorphisms rs7093069-IL-2RA, rs7138803-FAIM2, and rs1748033-PADI4 in the Group of Adolescents With Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ye, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, L.; Gao, L.; sun, Q.; Tong, S.; Sun, Z.; Yang, J.a.; et al. FAIM2 is a potential pan-cancer biomarker for prognosis and immune infiltration. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado de Mendoza, T.; Liu, F.; Verma, I.M. Antiapoptotic Role for Lifeguard in T Cell Mediated Immune Response. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0142161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-T.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Cheng, B.-W.; Lo, F.-S.; Ting, W.-H.; Lee, Y.-J. Graves disease is more prevalent than Hashimoto disease in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniyama, M.; Kasuga, A.; Nagayama, C.; Ito, K. Occurrence of type 1 diabetes in graves' disease patients who are positive for antiglutamic Acid decarboxylase antibodies: an 8-year followup study. J Thyroid Res 2010, 2011, 306487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Urrutia, P.; Abud, C.; Franco-Trecu, V.; Colistro, V.; Rodríguez-Arellano, M.E.; Alvarez-Fariña, R.; Acuña Alonso, V.; Bertoni, B.; Granados, J. Effect of 15 BMI-Associated Polymorphisms, Reported for Europeans, across Ethnicities and Degrees of Amerindian Ancestry in Mexican Children. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulit, S.L.; Stoneman, C.; Morris, A.P.; Wood, A.R.; Glastonbury, C.A.; Tyrrell, J.; Yengo, L.; Ferreira, T.; Marouli, E.; Ji, Y.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for body fat distribution in 694 649 individuals of European ancestry. Human Molecular Genetics 2019, 28, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Richardson, T.G.; Zhan, Y.; Carlsson, S. Childhood adiposity and novel subtypes of adult-onset diabetes: a Mendelian randomisation and genome-wide genetic correlation study. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Yu, J. Clinical features of childhood diabetes mellitus focusing on latent autoimmune diabetes. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2016, 21, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihrauch-Blüher, S.; Wiegand, S. Risk Factors and Implications of Childhood Obesity. Current Obesity Reports 2018, 7, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Villatoro Velázquez, J.A.; Camarena, B.; Martín del Campo Sanchez, R.; Fleiz Bautista, C.; Bustos Gamiño, M.; Reséndiz, E.; Aguilar, A.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; et al. The Identification of Admixture Patterns Could Refine Pharmacogenetic Counseling: Analysis of a Population-Based Sample in Mexico. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.A.M.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4, s13742–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Palma-Martínez, M.J.; Chong, A.Y.; Quinto-Cortés, C.D.; Barberena-Jonas, C.; Medina-Muñoz, S.G.; Ragsdale, A.; Delgado-Sánchez, G.; Cruz-Hervert, L.P.; Ferreyra-Reyes, L.; et al. Mexican Biobank advances population and medical genomics of diverse ancestries. Nature 2023, 622, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Forer, L.; Schönherr, S.; Sidore, C.; Locke, A.E.; Kwong, A.; Vrieze, S.I.; Chew, E.Y.; Levy, S.; McGue, M.; et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nature Genetics 2016, 48, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiela, M.J.; Chanock, S.J. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3555–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).