Submitted:

23 January 2026

Posted:

23 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

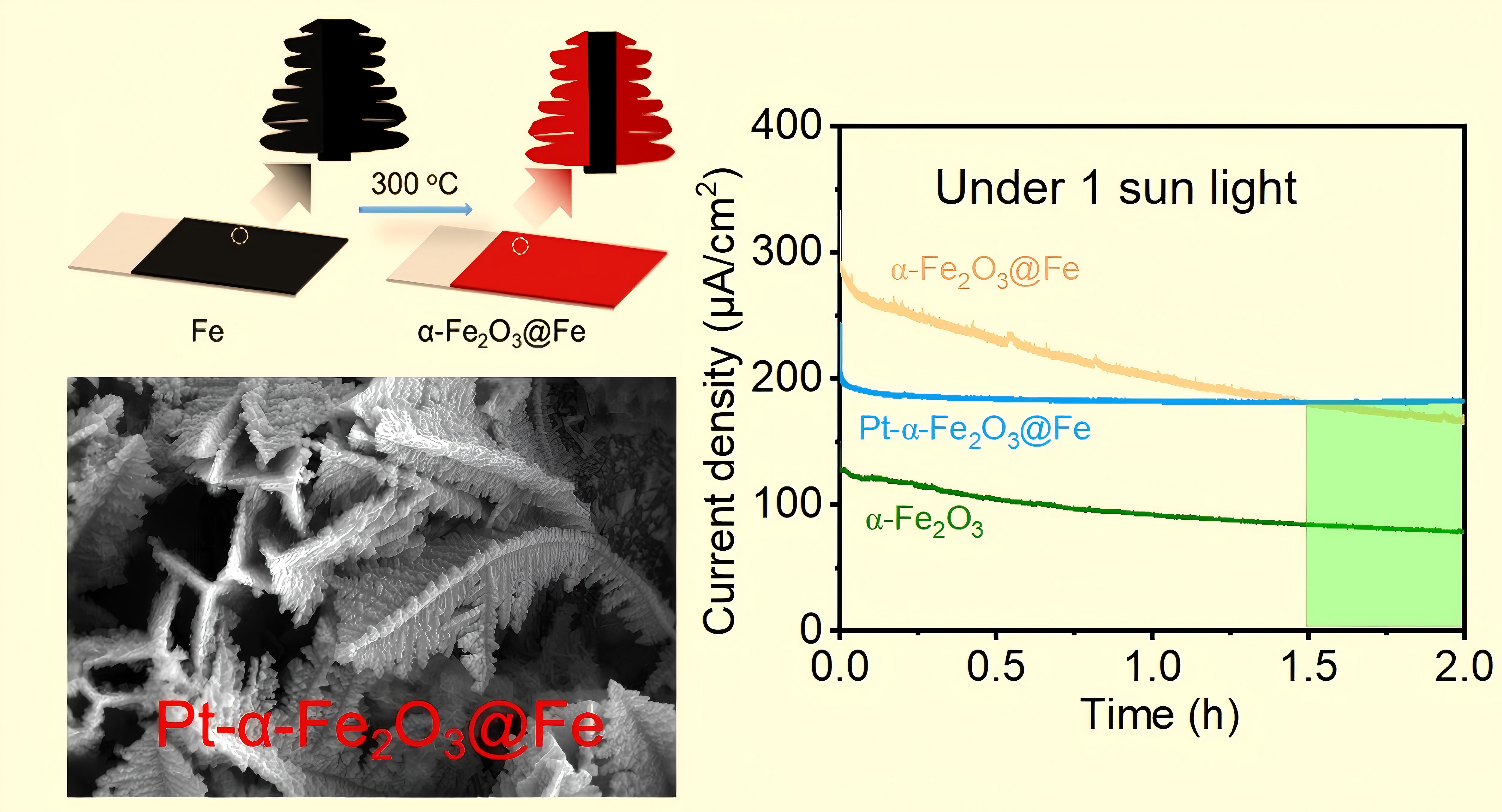

3.1. Synthesis Principle of α-Fe₂O₃@Fe

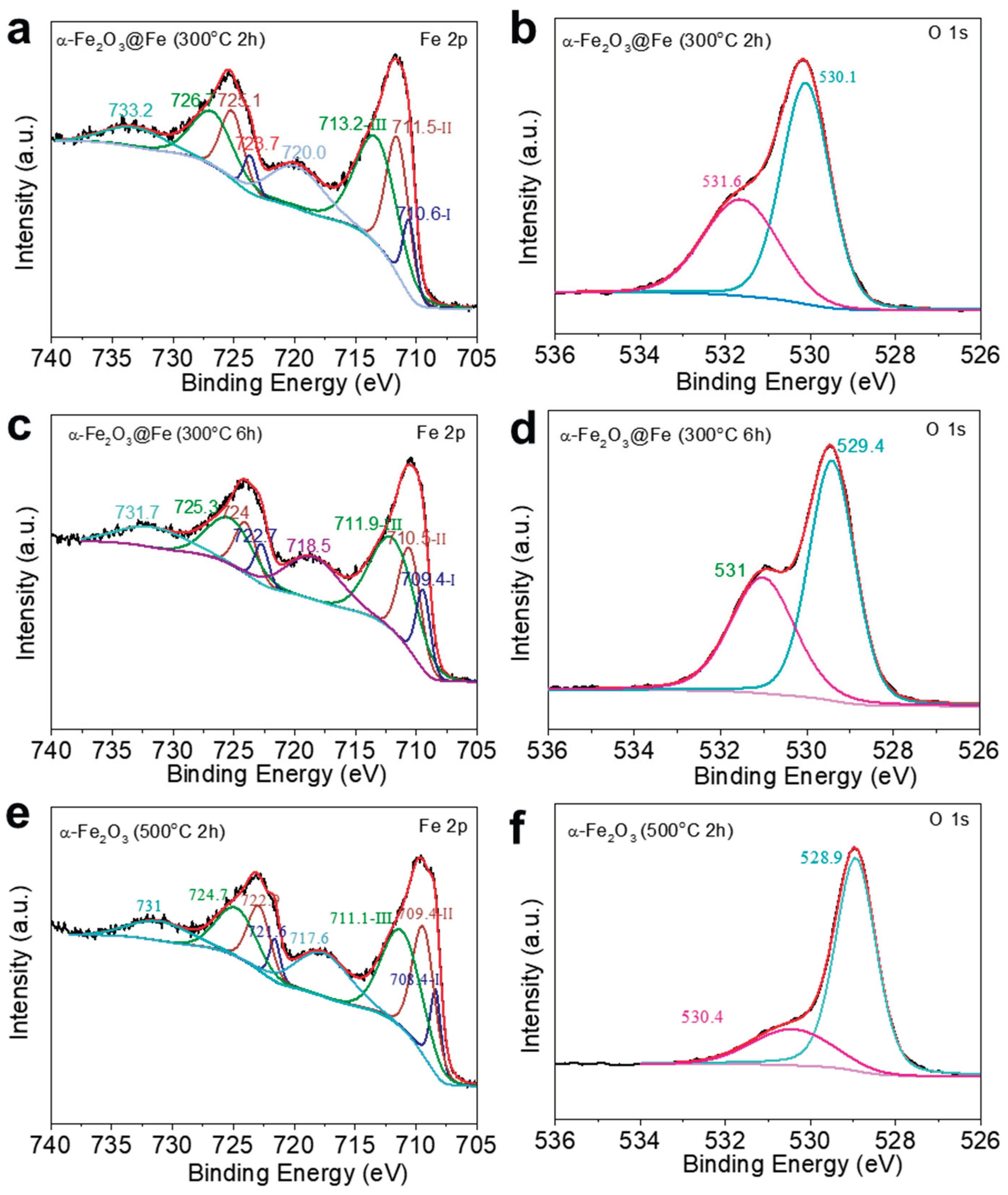

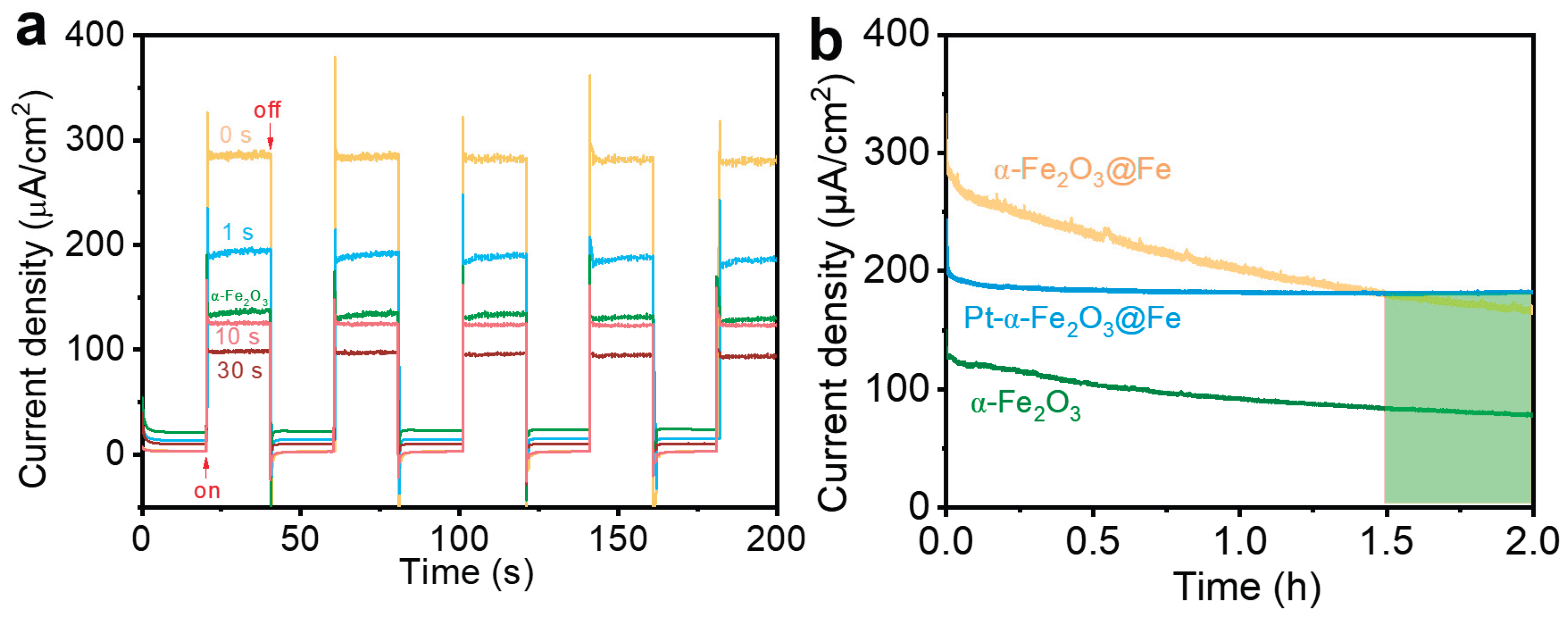

3.2. Systematic Performance Testing and Characterization of Target Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen production technologies: from fossil fuels toward renewable sources. A mini review. Energy & Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.G.; Warren, E.L.; McKone, J.R.; Boettcher, S.W.; Mi, Q.; Santori, E.A.; Lewis, N.S. Solar water splitting cells. Chemical reviews 2010, 110, 6446–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xu, W.; Meng, L.; Tian, W.; Li, L. Recent progress on semiconductor heterojunction-based photoanodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Small Science 2022, 2, 2100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisatomi, T.; Kubota, J.; Domen, K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43, 7520–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najaf, Z.; Nguyen, D.L.T.; Chae, S.Y.; Joo, O.-S.; Shah, A.U.H.A.; Vo, D.-V. N.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Van Le, Q.; Rahman, G. Recent trends in development of hematite (α-Fe2O3) as an efficient photoanode for enhancement of photoelectrochemical hydrogen production by solar water splitting. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23334–23357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuwanto, H.; Abdullah, H.; Kuo, D.-H. Nanostructuring Bi-doped α-Fe2O3 thin-layer photoanode to advance the water oxidation performance. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2022, 5, 9902–9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.; Jalil, A.; Asmadi, M.; Hassan, N.; Bahari, M.; Alhassan, M.; Izzudin, N.; Sawal, M.; Saravanan, R.; Karimi-Maleh, H. Recent advances in zinc oxide-based photoanodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 107, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Pawar, A.U.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Kang, Y.S. Highly enhancing photoelectrochemical performance of facilely-fabricated Bi-induced (002)-oriented WO3 film with intermittent short-time negative polarization. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 233, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, S.; Yu, S.; Yu, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Ping, D.; Zheng, J.Y. Strategies for enhancing the stability of WO3 photoanodes for water splitting: A review. Chemical Engineering Science 2025, 302, 120894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, X.; Yang, H.; Li, F.; Li, S.; Kang, Y.S.; Zheng, J.Y. Mechanism, modification and stability of tungsten oxide-based electrocatalysts for water splitting: A review. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2024, 99, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xie, Z.; Tong, Y.; Huang, Y. Review on BiVO4-based photoanodes for photoelectrochemical water oxidation: the main influencing factors. Energy & Fuels 2022, 36, 9932–9949. [Google Scholar]

- Bavykina, A.; Kolobov, N.; Khan, I.S.; Bau, J.A.; Ramirez, A.; Gascon, J. Metal–organic frameworks in heterogeneous catalysis: recent progress, new trends, and future perspectives. Chemical reviews 2020, 120, 8468–8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, F.; Dai, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Guo, X. A review on metal-organic frameworks for photoelectrocatalytic applications. Chinese Chemical Letters 2020, 31, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.H.; Frese, K.W. Flatband Potentials and Donor Densities of Polycrystalline α-Fe2O3 Determined from Mott-Schottky Plots. Journal of the Electrochemical Society 1978, 125, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Kang, M.J.; Song, G.; Son, S.I.; Suh, S.P.; Kim, C.W.; Kang, Y.S. Morphology evolution of dendritic Fe wire array by electrodeposition, and photoelectrochemical properties of α-Fe2O3 dendritic wire array. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 6957–6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Son, S.I.; Van, T.K.; Kang, Y.S. Preparation of α-Fe2O3 films by electrodeposition and photodeposition of Co–Pi on them to enhance their photoelectrochemical properties. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 36307–36314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ding, R.; Fu, Q.; Bi, L.L.; Zhou, X.; Yan, W.; Xia, W.; Luo, Z. A highly efficient MoOx/Fe2O3 photoanode with rich vacancies for photoelectrochemical O2 evolution from water splitting. New Journal of Chemistry 2024, 48, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Du, X.; Li, M.; Chen, H.; Hu, B.; Ding, H.; Wang, N.; Jin, L.; Liu, W. Enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting performance of α-Fe2O3 photoanodes through Co-modification with Co single atoms and gC3N4. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 12973–12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, C. Deposition of FeOOH Layer on Ultrathin Hematite Nanoflakes to Promote Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Micromachines 2024, 15, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhang, R.; Chai, Z.; Pu, J.; Kang, R.; Wu, G.; Zeng, X. Synergies of Zn/P-co-doped α-Fe2O3 photoanode for improving photoelectrochemical water splitting performance. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Zheng, J.Y.; Cha, H.G.; Jung, M.H.; Lee, K.J.; Kang, Y.S. One-dimensional ferromagnetic dendritic iron wire array growth by facile electrochemical deposition. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 1565–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, C.; Li, Y.; Han, W.; Fu, W.; He, Y.; Xie, E. Enhanced charge separation and transfer through Fe2O3/ITO nanowire arrays wrapped with reduced graphene oxide for water-splitting. Nano Energy 2016, 30, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arico, A.; Shukla, A.; Kim, H.; Park, S.; Min, M.; Antonucci, V. An XPS study on oxidation states of Pt and its alloys with Co and Cr and its relevance to electroreduction of oxygen. Applied Surface Science 2001, 172, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhu, J.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ding, K.; Chen, W. Structural and electronic properties of tungsten trioxides: from cluster to solid surface. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2011, 130, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).