1. Introduction

Cancer development involves a complex interplay of genetic alterations, environmental exposures, and cellular stress [

1]. Among the genes most frequently affected,

TP53 stands out as the single most mutated gene in human cancers, with alterations identified in approximately 50% of solid tumors [

2].

TP53 encodes the tumor suppressor protein p53, a transcription factor central to maintaining genomic integrity through its roles in DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis [

3]. Mutations affecting the DNA-binding domain (DBD), which spans exons 5 to 8, are particularly disruptive, as this region is essential for sequence-specific DNA recognition and transcriptional regulation [

4]. In addition to its canonical functions, p53 interacts with several regulatory pathways, including apoptotic mediators such as BCL-2 [

5]. Under physiological conditions, activated p53 represses

BCL2 expression to promote apoptosis, helping eliminate damaged or potentially oncogenic cells. Alterations in

TP53 can therefore compromise not only DNA damage responses but also apoptotic signaling, contributing to tumor progression and therapy resistance [

6].

The distribution and functional impact of

TP53 mutations vary extensively across cancer types, geographical regions, and populations [

7,

8]. Factors such as genetic background, lifestyle, and environmental exposures shape the mutational landscape of cancers [

9]. This heterogeneity involves both somatic and germline variants. While the present study focuses on somatic variants identified in tumor tissue, it is important to note that inherited polymorphisms can also modulate cancer risk. For instance, the germline Pro47Ser (rs1800371) polymorphism, enriched in individuals of African ancestry, has been associated with reduced p53 tumor-suppressive activity and increased susceptibility to breast cancer (BC) [

10]. Despite this diversity, African populations remain underrepresented in cancer genomics research, resulting in limited knowledge about mutation patterns and their biological implications [

11].

In Senegal, the oral cavity cancer (OCC), prostate cancer (PC) and BC represent growing public health concerns. Recent clinical and epidemiological data have documented a notable rise in their incidence, yet molecular studies focusing on

TP53 remain scarce [

12,

13,

14]. Understanding the mutational spectrum of

TP53 and its potential functional consequences is essential for advancing molecular oncology in these populations.

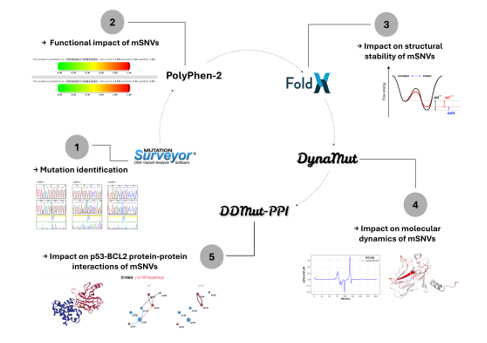

The present study aims to characterize mutations occurring in exons 5 and 6 of TP53 in Senegalese patients diagnosed with OCC, PC, and BC, using a comprehensive computational framework. Through the integration of sequence analysis, pathogenicity prediction, structural stability assessment, molecular dynamics evaluation, and protein–protein interactions (PPIs) modeling, we sought to gain insight into how these variants may influence p53 structure and function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

This study involved the retrospective analysis of anonymized DNA sequences obtained from archived diagnostic materials in Genomics Laboratory of the Faculty of Science and Technology at the Cheikh Anta Diop University. No patient-identifying information, clinical metadata, or demographic variables were used. Because all samples were pre-existing, fully anonymized, and analyzed exclusively for secondary research purposes, formal institutional ethics approval was not required, in accordance with international guidelines for retrospective studies using de-identified biological material.

2.2. Patients and Sampling

A total of 78 anonymized DNA samples corresponding to Senegalese patients diagnosed with OCC (n = 40), PC (n = 18), and BC (n = 20) were retrieved from institutional archives. These samples had been originally collected as part of routine diagnostic workflows. DNA extraction was previously performed using the Zymo Research kit following manufacturer instructions. Archived DNA samples had previously undergone PCR amplification of exons 5 and 6 using the following primer pair: Forward: 5′-GTTTCTTTGCTGCCGTCTTC-3′, Reverse: 5′-CTTAACCCCTCCTCCCAGAG-3′. Amplicons were verified on 2% agarose gel with a 100 bp SmartLadder and sequenced using Sanger sequencing at Macrogen Europe.

Exons 5 and 6 of TP53 were selected because they encode the core of the DBD, which harbors multiple mutational hotspots critical for p53 function. These exons were also the only regions consistently amplified and archived in the participating diagnostic laboratories. Although exons 7 and 8 also belong to the DBD and include known hotspots, they were unavailable in the archived sequencing datasets. Consequently, this study focuses on exons 5–6 and acknowledges this limitation. Future work will extend the analysis to exons 5–8.

2.3. Sanger Quality Control and Variant Validation

Because Sanger sequencing does not generate depth-of-coverage metrics as in NGS, quality control relied on electropherogram inspection and Mutation Surveyor v5.2 default filtering parameters, including peak morphology and symmetry, peak-to-noise ratio thresholds, automated artifact removal (dye blobs, shoulder peaks, baseline noise), forward–reverse signal concordance. Mutation Surveyor’s numerical mutation score (NM score) was used to assess confidence. Variants with NM score > 20 were accepted as high confidence following the threshold recommended by the software manufacturer, where NM scores above 20 indicate strong mutation signal reliability and minimal likelihood of artifact. Ambiguous chromatogram regions were manually inspected, and any sequence with unresolved noise or poor alignment quality was excluded. Rare variants were validated through manual chromatogram verification, forward–reverse comparison and re-alignment using Biopython’s Bio.Align module and ClustalW2 to exclude alignment artifacts.

Somatic status was inferred through a multi-step annotation strategy. First, all variants listed in COSMIC v97 were classified as somatic. Then, variants present in dbSNP build 155 with documented non-zero population allele frequencies were considered germline polymorphisms and excluded from further analysis. Finally, variants that appeared in dbSNP without allele-frequency information, as well as those absent from both COSMIC and dbSNP, were retained as somatic-like when they occurred within established TP53 hotspot regions or exhibited substitution patterns characteristic of tumor-associated mutations such as C>T transitions at CpG dinucleotides.

2.4. Computational Analyzes

2.4.1. Functional Impact Assessment

Single nucleotide missense variants (mSNVs) were evaluated using Polymorphism Phenotyping-2 (PolyPhen-2), which classifies variants as probably damaging, possibly damaging, or benign [

15]. Predictions were based on the reference sequence NP_000537.3.

2.4.2. Impact on Structural Stability

The Gibbs free energy (

) of mutant p53 was estimated using FoldX 5.0 via the Pyfolfx library to assess the effects of mutations on p53 structural stability [

16,

17].

measures protein stability, determining whether a given structure is thermodynamically favorable or unfavorable. FoldX 5.0 calculates

by decomposing energy contributions from various interaction types within the protein, including Van der Waals forces, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, backbone and sidechain entropies, and steric clashes. For each mutation, FoldX 5.0 calculates the difference in Gibbs free energy (

) by subtracting the

of the wild-type protein from that of the mutant:

. By convention: the mutant protein is significantly unstable if

> 1 kcal·mol⁻¹, neutral if between -1 and 1 kcal·mol⁻¹, significantly stable if

< -1 kcal·mol⁻¹ [

18]. The crystallographic structure 2FEJ from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) was used for this evaluation and the “RepairPDB” function was applied before mutation modeling.

2.4.3. Impact on Molecular Dynamics

Mutation-induced changes in vibrational entropy (

) and flexibility were estimated using DynaMut [

19]. It employs normal mode analysis (NMA) using the Elastic Network Contact Model (ENCoM) [

20]. ENCoM models the protein as an elastic network model where residues represent nodes and interactions are modeled as springs. The difference in vibrational entropy (

) is obtained by subtracting the ΔS_vib of the wild-type protein from that of the mutant:

. ENCoM

values were classified as stabilizing (

< –0.1 kcal.mol

-1.K

-1), neutral (–0.1 ≤

≤ +0.1 kcal.mol

-1.K

-1), or destabilizing (

> +0.1 kcal.mol

-1.K

-1), using a ±0.1 kcal

-1mol

-1 threshold commonly applied to account for model precision and to avoid overinterpreting minimally small entropic fluctuations. The same crystallographic structure 2FEJ was used as template.

2.4.4. Impact on p53-BCL2 Protein-Protein Interactions

To assess the effect of mSNVs on the p53–BCL-2 PPIs,

binding affinity changes were predicted using DDMut-PPI, based on the p53–BCL-2 complex structure 8HLL [

21]. DDMut-PPI extends DDMut with a robust Siamese network architecture incorporating graph-based signatures and existing mutagenesis data. The model was enhanced with a graph neural network to capture structural and physicochemical features of PPIs interfaces. BCL-2 was selected because p53 directly regulates apoptosis through transcriptional repression of

BCL2, making alterations in this interaction biologically relevant.

2.4.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python (SciPy and Statsmodels libraries). Differences in TP53 mutation frequencies between cancer types were first assessed using a Chi² test of independence. Because some contingency table cells contained low expected counts, pairwise comparisons between cancer types were subsequently performed using Fisher’s exact test. Differences in the distribution of mutations between TP53 exons 5 and 6 across cancer types were evaluated using a Chi² test of independence. To assess exon-specific mutation enrichment within each cancer type, exact binomial tests were performed by comparing the number of mutations observed in exon 6 relative to exon 5. For PolyPhen-2 pathogenicity predictions, variants were analyzed at the variant level and classified as damaging (possibly damaging or probably damaging) or non-damaging (benign). Differences in pathogenicity distributions between cancer types were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons of continuous structural stability and conformational dynamics metrics, including FoldX values and ENCoM-derived values, between TP53 exons 5 and 6 were conducted using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test, as these variables did not meet assumptions of normality. Two-sided p-values were reported. For all analyses involving multiple pairwise comparisons, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. An adjusted p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

A significant variation in

TP53 mutation frequency across cancer types was observed, as demonstrated by the Chi² analysis (

p = 0.015), with BC exhibiting the highest proportion of mutated cases. Pairwise comparisons further indicated that this difference was primarily driven by BC, whereas mutation frequencies in OCC and PC were not significantly different after correction for multiple testing. The elevated mutational burden observed in BC may reflect cancer-type specific biological and etiological factors. Mammary epithelial cells are subject to intense hormonal regulation and metabolic activity, particularly in estrogen-responsive contexts, which has been associated with increased oxidative stress and the generation of reactive oxygen species capable of inducing DNA damage [

22]. Previous studies have also reported a correlation between oxidative stress levels and BC aggressiveness, suggesting sustained pressure on DNA damage response pathways such as p53 [

23]. In contrast, PC progression is largely driven by androgen receptor signaling, which may impose distinct selective pressures on

TP53 compared with hormonally regulated breast tissue [

24]. OCC, on the other hand, is predominantly associated with environmental carcinogens such as tobacco, alcohol, and viral infections, particularly HPV, where

TP53 alterations are present but not uniformly required for tumor development [

25]. Consistently, OCC samples in this study displayed the lowest average mutational burden per patient, supporting a more heterogeneous mutational landscape.

Across cancer types, the spectrum of

TP53 variants differed in both composition and diversity. In OCC, we identified 39 mSNVs, one nonsense mutation, and two small indels. In contrast, PC harbored 38 mSNVs and five nonsense mutations, while BC presented 42 mSNVs and two nonsense mutations, with no indels detected in either PC or BC. Although the overall proportions of variant classes were broadly comparable, notable differences emerged in the diversity and distribution of unique variants across exons. At the variant level, OCC exhibited approximately twice as many unique nsSNVs as PC and BC (31 versus 14 and 15, respectively), despite a lower average number of mutations per patient. This pattern suggests a broader mutational heterogeneity in OCC, potentially reflecting diverse mutagenic exposures rather than recurrent hotspot-driven alterations. The presence of indels exclusively in OCC further supports this interpretation, as such variants are often associated with error-prone DNA repair mechanisms induced by environmental carcinogens. These observations are consistent with previous large-scale analyses of

TP53 mutational landscapes. In particular, Mroz et al. reported increased heterogeneity and reduced recurrence of

TP53 mutations in head and neck cancers compared with other solid tumors, based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data [

26]. Together, these findings suggest that

TP53 alterations in OCC may arise from a wider range of mutational processes, whereas PC and BC appear to be characterized by more recurrent and structurally constrained mutation patterns.

Our analyses further revealed significant exon-dependent distribution of

TP53 mSNVs across cancer types. At the global level, exon location was significantly associated with cancer type (

p = 0.007), with exon 6 showing a marked enrichment of mutations in BC (

p < 0.001), whereas no significant exon-specific difference was observed in OCC or PC. These findings suggest that selective pressures acting on the

TP53 DBD may differ across tumor contexts, with exon 6 playing a particularly prominent role in BC within the Senegalese population. This BC result contrasts with several large-scale studies reporting a predominance of exon 5 mutations within the

TP53 DBD across diverse populations. For example, in their review, Leroy et al. described exon 5 as one of the most frequently mutated regions in multiple cancer types [

27]. The enrichment of exon 6 mutations observed in our study therefore points to a potential population-specific mutational pattern. Such discrepancies may reflect differences in genetic background, environmental exposures, or selective pressures acting on p53 function in distinct populations. Notably, exon 6 in PC and BC cohort also harbored recurrent truncating mutations, including Y220* and E221*. Theses nonsense mutations are expected to severely compromise the structural integrity of the p53 DBD as they result in premature termination within a region critical for proper folding, zinc coordination, and DBD activity [

28]. Although PolyPhen-2 predictions did not reveal statistically significant differences in pathogenicity proportions across cancer types, the combined enrichment of exon 6 mutations and the presence of truncating variants support the notion that alterations affecting this exon may exert substantial functional consequences. Jointly, these findings suggest that exon 6 mutations may contribute to BC development through mechanisms that extend beyond mutation frequency alone.

At the structural and dynamic levels,

TP53 mutations identified in PC and BC displayed relatively moderate average effects when considered globally. However, a clear exon-dependent divergence emerged upon stratification. Exon 6 variants were significantly more stabilizing than exon 5 variants in PC (

p < 0.001) and BC (

p = 0.001), whereas no exon-dependent difference was observed in OCC (

p = 0.855). In parallel, ENCoM-based ΔΔ

Svib analysis uncovered a partially independent pattern: exon 5 mutations in PC induced significantly greater flexibility changes than exon 6 mutations (

p = 0.021), while no significant exon-specific differences in conformational dynamics were detected in OCC (

p = 0.353) or BC (

p = 0.917). Despite the greater mutational diversity observed in OCC,

TP53 mutations in this cancer type and exon 5 mutations across all three cancers, were predominantly destabilizing. Such destabilizing alterations are frequently associated with loss-of-function (LOF) effects, as they impair the structural integrity of the p53 DNA-binding domain, leading to reduced protein stability, defective DNA binding, and compromised transcriptional activity [

28]. Consistent with the exposure-related etiology of OCC,

TP53 mutations in this context likely arise from multiple mutational processes and exert variable, often deleterious, effects on p53 stability and conformational dynamics.

Notably, the exon 6 associated stabilization was largely driven by recurrent mSNVs such as V217L and V218M, which were shared between PC and BC cohorts. Although functional data on V218M remain limited and V217L has not been extensively characterized, stabilizing mutations of p53 have been increasingly linked to the accumulation of mutant protein and the acquisition of oncogenic gain-of-function (GOF) properties rather than restoration of tumor-suppressive activity [

29]. Such GOF effects have been implicated in enhanced tumor progression, metastatic potential, and resistance to therapy in multiple cancer contexts [

30]. The recurrence of these stabilizing mutations supports the hypothesis of selective pressure from

TP53 exon 6 favoring structurally stable mutant p53 proteins in these cancers.

Beyond their effects on p53 structural stability and conformational dynamics,

TP53 mutations may also influence tumor progression through altered PPIs. All analyzed mSNVs were predicted to stabilize the interaction between p53 and BCL-2, suggesting a general tendency toward enhanced binding affinity in the mutant context. This effect was particularly pronounced for specific variants, including R175P, H193P, R175H and R196P. Although most of these mutant residues were not located in the PPIs interface, the predicted stabilization of the p53–BCL-2 complex may have important functional implications. Increased association with BCL-2 could impair the pro-apoptotic functions of p53 by reinforcing anti-apoptotic signaling. In particular, recurrent mutations such as R175H and R196P have been extensively characterized as oncogenic

TP53 variants and are frequently associated with loss of canonical p53 transcriptional activity as well as GOF properties [

2,

29,

31]. The observation that both cancer-specific and shared

TP53 mutations enhance p53–BCL-2 interaction supports a model in which mutant p53 contributes to tumor cell survival by promoting resistance to apoptosis. In this context, stabilization of the p53–BCL-2 complex may represent an additional mechanism through which mutant p53 exerts oncogenic effects, complementing structural stabilization and altered conformational dynamics. Such effects may be particularly relevant in cancers where apoptotic escape constitutes a key driver of disease progression and therapeutic resistance.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design and the restriction to exons 5 and 6 of TP53 limit the generalization of the findings to the full mutational spectrum of the gene. Second, the analyses were based exclusively on in silico predictions, and experimental validation of the structural, functional, dynamic, and PPIs interaction effects were not performed. In addition, the absence of matched normal samples precluded direct discrimination between somatic and rare germline variants. Despite these limitations, the integrative computational approach provides valuable insights into TP53 mutational patterns in an underrepresented population and establishes a framework for future experimental and large-scale genomic studies. While restricted to bioinformatic analyses, this exploratory work

Figure 1.

Frequency of TP53 mutations across cancer types. (A) Percentage of patients carrying at least one somatic TP53 mutation among OCC (n=39), PC (n=17), and BC (n=20) groups. (B) Mean number of somatic TP53 mutations per patient in each cancer type. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

Frequency of TP53 mutations across cancer types. (A) Percentage of patients carrying at least one somatic TP53 mutation among OCC (n=39), PC (n=17), and BC (n=20) groups. (B) Mean number of somatic TP53 mutations per patient in each cancer type. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Distribution of TP53 mSNVs across exons 5 and 6. The X-axis displays all amino acid positions corresponding to exons 5 (codons 126–186) and 6 (codons 187–224). Vertical markers indicate positions where somatic mutations were detected in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Their height represents the percentage of patients carrying a mutation at that position.

Figure 2.

Distribution of TP53 mSNVs across exons 5 and 6. The X-axis displays all amino acid positions corresponding to exons 5 (codons 126–186) and 6 (codons 187–224). Vertical markers indicate positions where somatic mutations were detected in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Their height represents the percentage of patients carrying a mutation at that position.

Figure 3.

TP53 mSNVs rates normalized by exon length. Bar plots show the number of somatic TP53 mutations per 100 bp in exon 5 and exon 6 for OCC, PC, BC. Mutation counts were normalized by exon size (exon 5 = 184 bp, exon 6 = 113 bp) to account for length-dependent differences in mutation probability. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on a Poisson approximation of mutation counts.

Figure 3.

TP53 mSNVs rates normalized by exon length. Bar plots show the number of somatic TP53 mutations per 100 bp in exon 5 and exon 6 for OCC, PC, BC. Mutation counts were normalized by exon size (exon 5 = 184 bp, exon 6 = 113 bp) to account for length-dependent differences in mutation probability. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on a Poisson approximation of mutation counts.

Figure 4.

Distribution of PolyPhen-2 Predicted Functional Impact Across Cancer Types. Pie charts show the proportion of TP53 mSNVs classified by PolyPhen-2 as probably damaging, possibly damaging, or benign in OCC, PC, and BC.

Figure 4.

Distribution of PolyPhen-2 Predicted Functional Impact Across Cancer Types. Pie charts show the proportion of TP53 mSNVs classified by PolyPhen-2 as probably damaging, possibly damaging, or benign in OCC, PC, and BC.

Figure 5.

Exon-normalized rate of TP53 mSNVs predicted as ‘probably damaging’ by PolyPhen-2. Bars represent the number of probably damaging mSNVs per 100 bp in exon 5 and exon 6 for OCC, PC, and BC. Mutation counts were normalized by exon size (exon 5 = 184 bp, exon 6 = 113 bp). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals based on a Poisson approximation of mutation counts.

Figure 5.

Exon-normalized rate of TP53 mSNVs predicted as ‘probably damaging’ by PolyPhen-2. Bars represent the number of probably damaging mSNVs per 100 bp in exon 5 and exon 6 for OCC, PC, and BC. Mutation counts were normalized by exon size (exon 5 = 184 bp, exon 6 = 113 bp). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals based on a Poisson approximation of mutation counts.

Figure 6.

Structural stability impact of TP53 mSNVs predicted by FoldX across cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔG values (kcal/mol) for mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Each point represents a single variant, colored according to stability classification: stabilization ΔΔG ≤ −1 kcal/mol), neutral (−1 < ΔΔG ≤ 1 kcal/mol)), destabilization (1 < ΔΔG ≤ 5 kcal/mol)), strong destabilization (5 < ΔΔG ≤ 10 kcal/mol)), and severe destabilization (ΔΔG > 10 kcal/mol)).

Figure 6.

Structural stability impact of TP53 mSNVs predicted by FoldX across cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔG values (kcal/mol) for mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Each point represents a single variant, colored according to stability classification: stabilization ΔΔG ≤ −1 kcal/mol), neutral (−1 < ΔΔG ≤ 1 kcal/mol)), destabilization (1 < ΔΔG ≤ 5 kcal/mol)), strong destabilization (5 < ΔΔG ≤ 10 kcal/mol)), and severe destabilization (ΔΔG > 10 kcal/mol)).

Figure 7.

Comparison of FoldX ΔΔG distributions between TP53 exons 5 and 6 across cancer types. Boxplots show the distribution of ΔΔG values for mSNVs stratified by OCC, PC, and BC. Higher ΔΔG values indicate stronger destabilizing effects on p53 stability. Statistical differences between their ΔΔG distributions were assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests.

Figure 7.

Comparison of FoldX ΔΔG distributions between TP53 exons 5 and 6 across cancer types. Boxplots show the distribution of ΔΔG values for mSNVs stratified by OCC, PC, and BC. Higher ΔΔG values indicate stronger destabilizing effects on p53 stability. Statistical differences between their ΔΔG distributions were assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests.

Figure 8.

ENCoM-derived ΔΔSvib conformational dynamics predictions for TP53 mSNVs across cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔSvib values calculated using the ENCoM elastic network model for TP53 mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Positive ΔΔSvib values indicate increased molecular flexibility (destabilizing effect), whereas negative values indicate decreased flexibility (stabilizing effect). Each point represents one mSNV, colored according to its predicted impact on protein dynamics : stabilizing ΔΔSvib < –0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1), neutral ), neutral (–0.1 ≤ ΔΔSvib ≤ +0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1), and destabilizing (ΔΔSvib > +0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1).

Figure 8.

ENCoM-derived ΔΔSvib conformational dynamics predictions for TP53 mSNVs across cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔSvib values calculated using the ENCoM elastic network model for TP53 mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Positive ΔΔSvib values indicate increased molecular flexibility (destabilizing effect), whereas negative values indicate decreased flexibility (stabilizing effect). Each point represents one mSNV, colored according to its predicted impact on protein dynamics : stabilizing ΔΔSvib < –0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1), neutral ), neutral (–0.1 ≤ ΔΔSvib ≤ +0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1), and destabilizing (ΔΔSvib > +0.1 kcal.mol-1.K-1).

Figure 9.

Comparison of ENCoM ΔΔSvib distributions between TP53 exons 5 and 6 across cancer types. Boxplots show the distribution of ENCoM ΔΔSvib values for mSNVs stratified by OCC, PC, and BC. Higher ΔΔSvib values indicate stronger destabilizing effects on p53 stability. Statistical differences between their ΔΔSvib distributions were assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests.

Figure 9.

Comparison of ENCoM ΔΔSvib distributions between TP53 exons 5 and 6 across cancer types. Boxplots show the distribution of ENCoM ΔΔSvib values for mSNVs stratified by OCC, PC, and BC. Higher ΔΔSvib values indicate stronger destabilizing effects on p53 stability. Statistical differences between their ΔΔSvib distributions were assessed using two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests.

Figure 10.

Predicted impact of TP53 mSNVs on the p53–BCL-2 interaction across all cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔG values (kcal/mol) for the p53–BCL-2 complex for TP53 mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Negative ΔΔG values indicate a strengthening of the p53–BCL-2 interaction (stabilization of binding), whereas values close to zero correspond to a neutral effect. Variants were classified as stabilizing (ΔΔG ≤ −1 kcal/mol) or neutral (−1 < ΔΔG < 1 kcal/mol). No mutation reached the destabilizing range (ΔΔG ≥ 1 kcal/mol) in this dataset.

Figure 10.

Predicted impact of TP53 mSNVs on the p53–BCL-2 interaction across all cancer types. Scatter plots show ΔΔG values (kcal/mol) for the p53–BCL-2 complex for TP53 mSNVs identified in OCC (A), PC (B), and BC (C). Negative ΔΔG values indicate a strengthening of the p53–BCL-2 interaction (stabilization of binding), whereas values close to zero correspond to a neutral effect. Variants were classified as stabilizing (ΔΔG ≤ −1 kcal/mol) or neutral (−1 < ΔΔG < 1 kcal/mol). No mutation reached the destabilizing range (ΔΔG ≥ 1 kcal/mol) in this dataset.