Submitted:

22 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

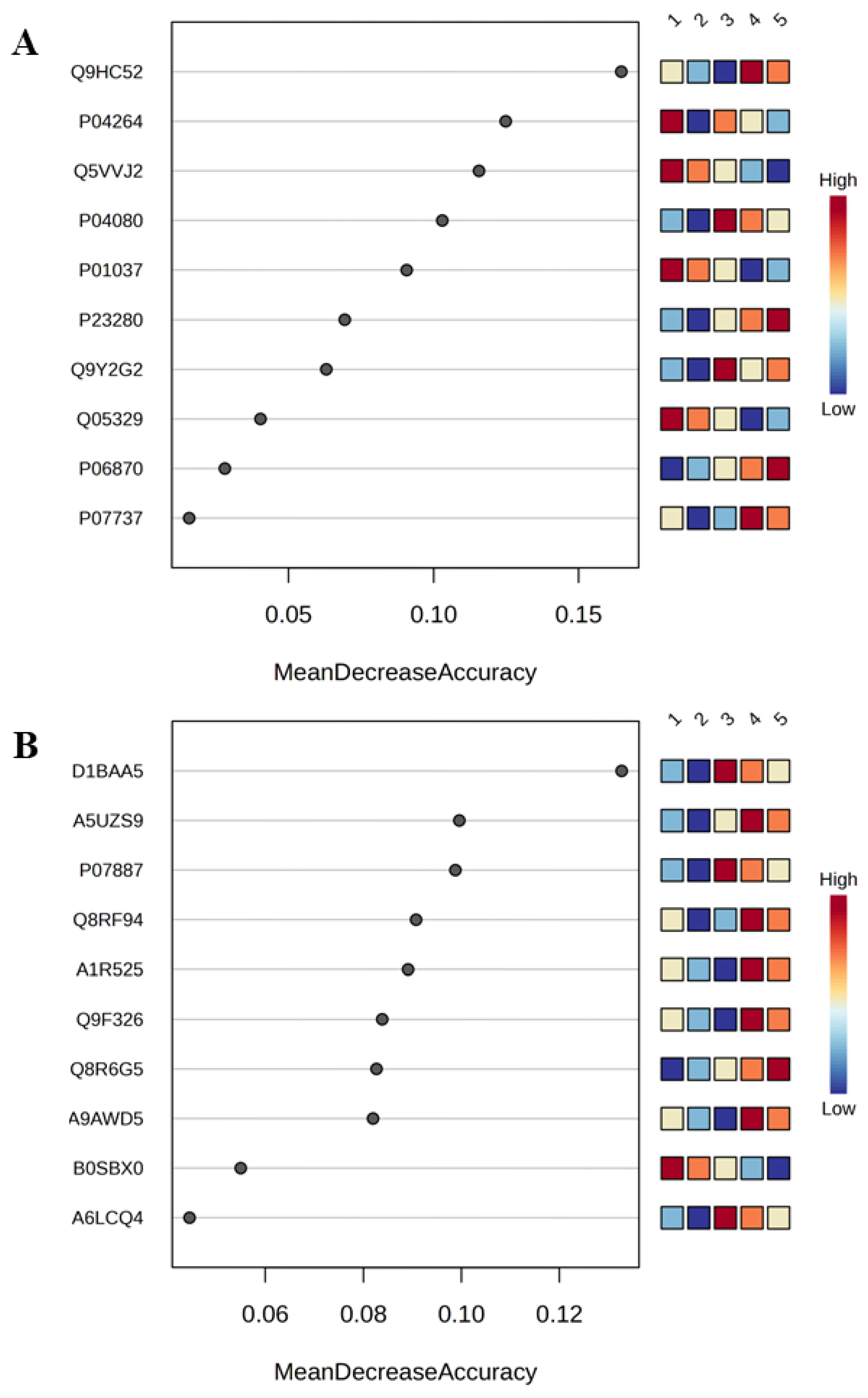

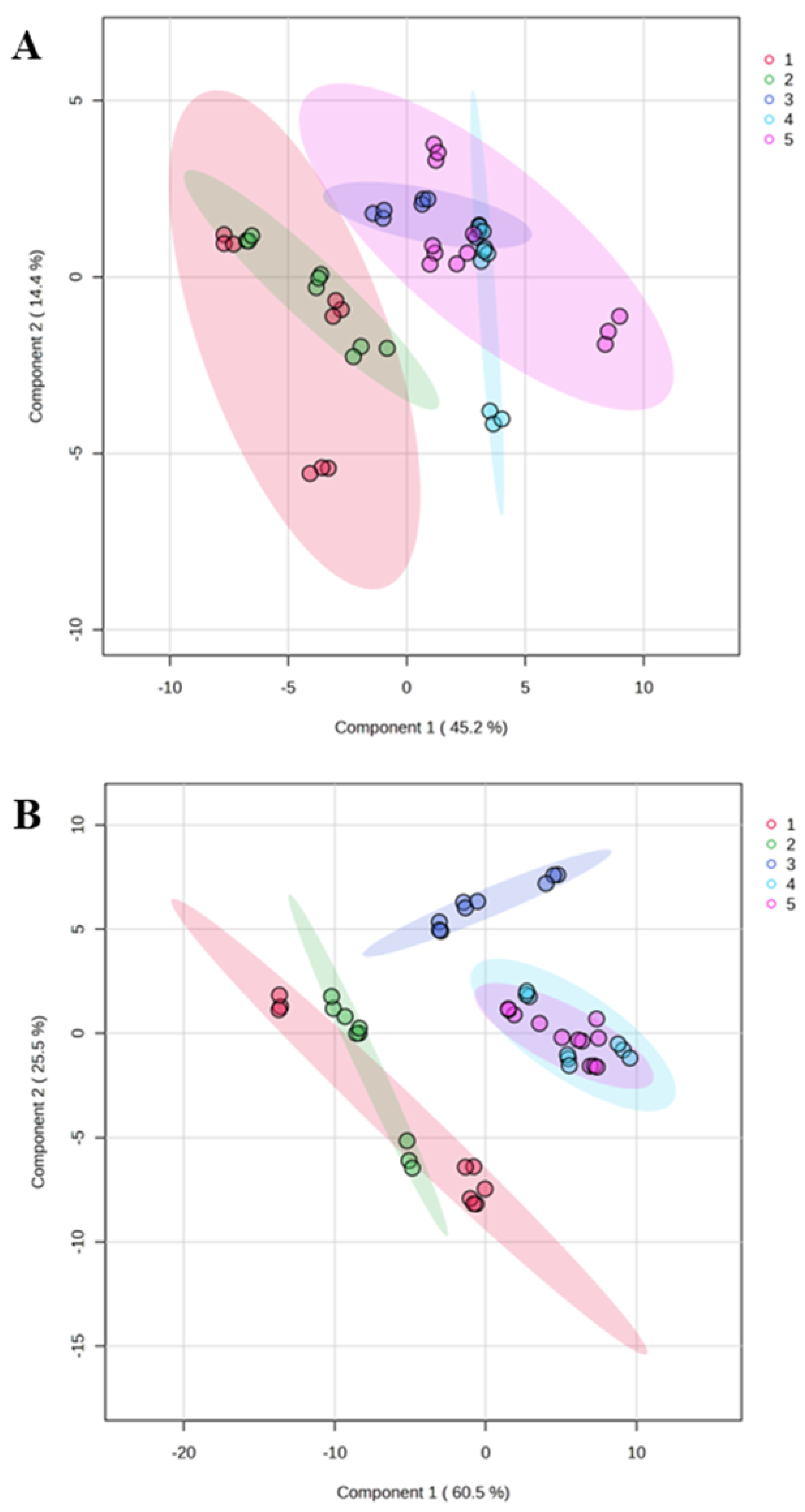

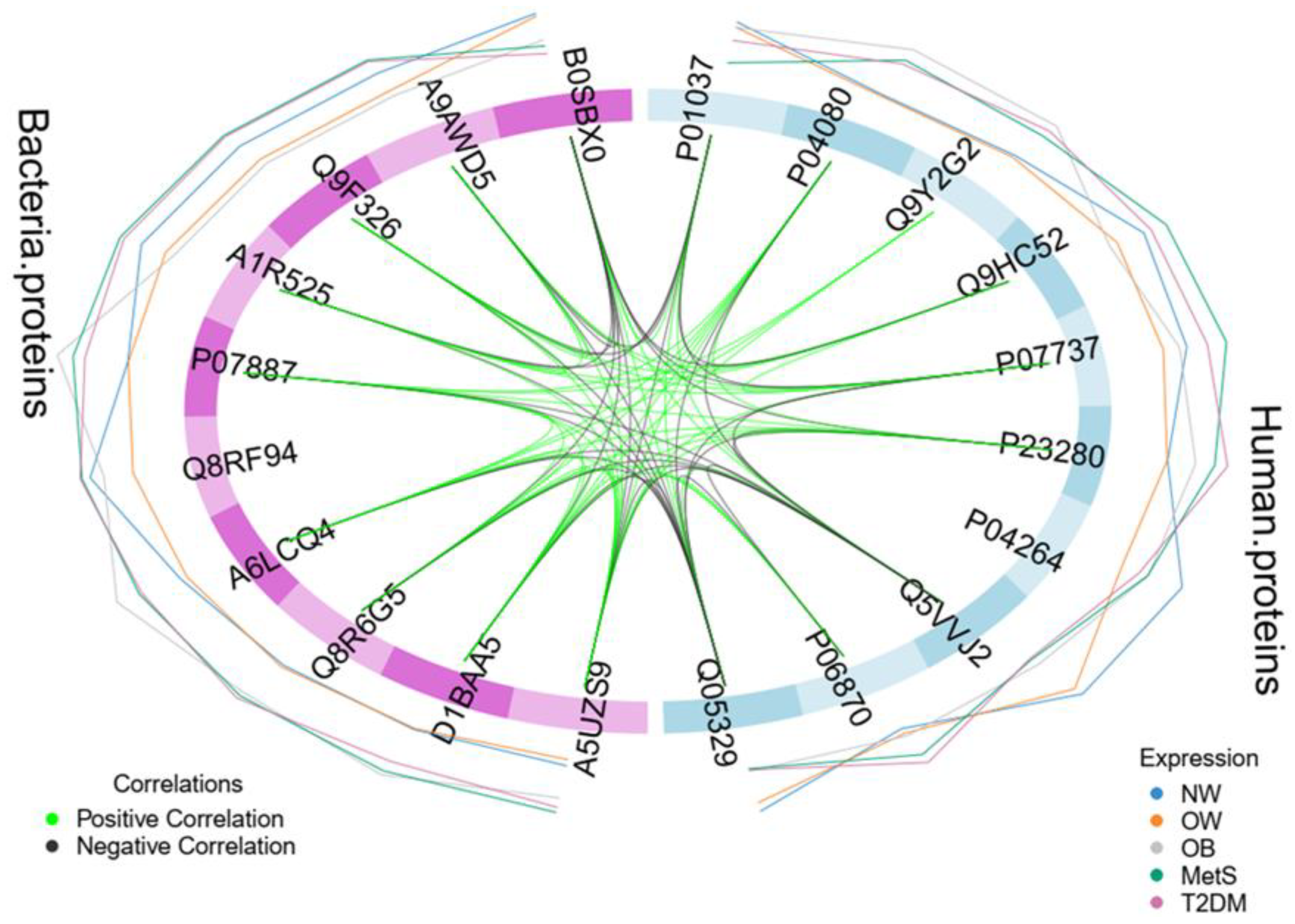

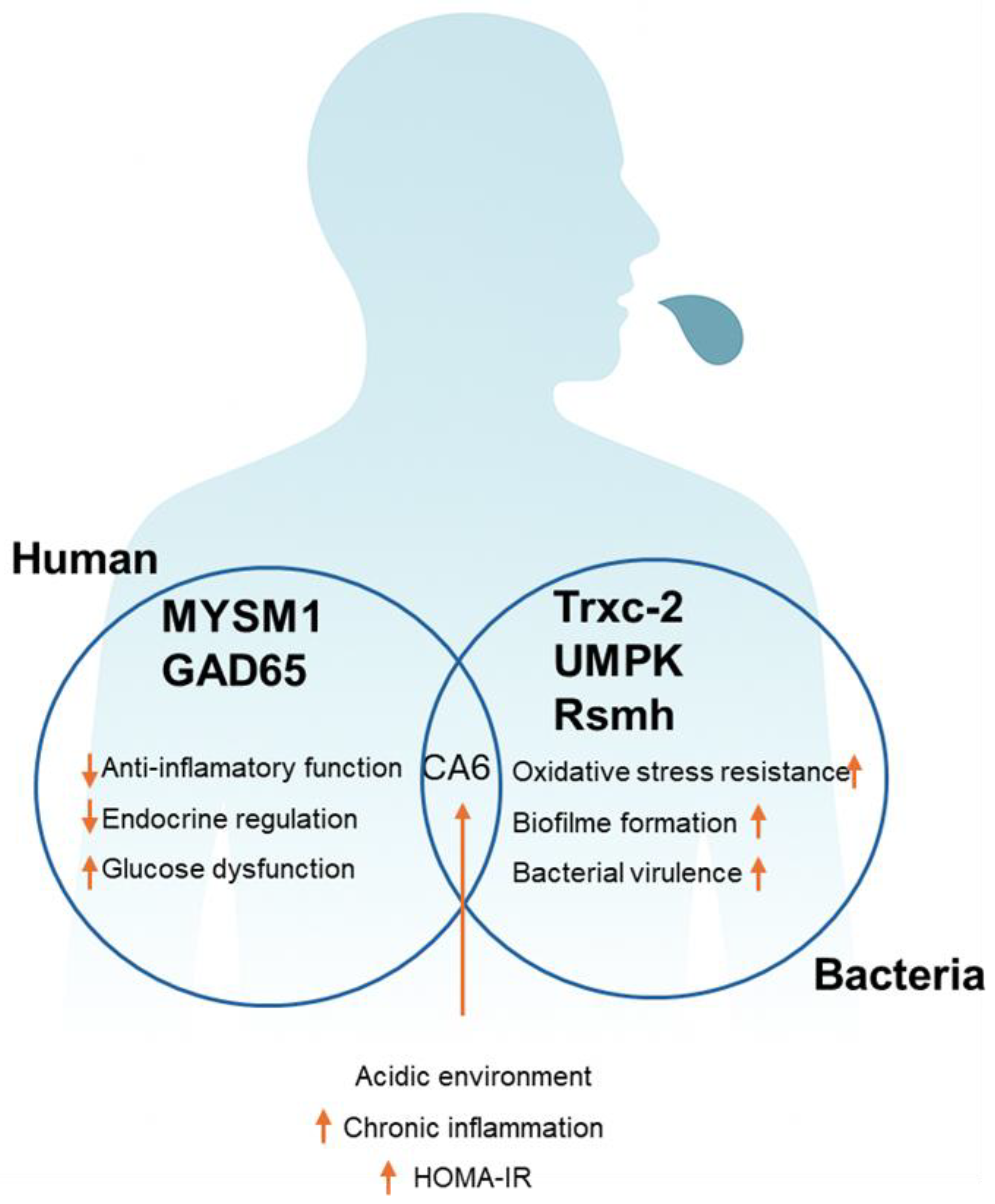

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Evaluation

3.2. Metaproteome Profiling of Saliva

3.3. Integrative Analysis of Clinical and Metaproteome Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and Overweight. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Prifti, E.; Belda, E.; Ichou, F.; Kayser, B.D.; Dao, M.C.; Verger, E.O.; Hedjazi, L.; Bouillot, J.-L.; Chevallier, J.-M.; et al. Major microbiota dysbiosis in severe obesity: Fate after bariatric surgery. Gut 2019, 68, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Almahmeed, W.; Bays, H.; Cuevas, A.; Di Angelantonio, E.; le Roux, C.W.; Sattar, N.; Sun, M.C.; Wittert, G.; Pinto, F.J.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Mechanistic insights and management strategies. A joint position paper by the World Heart Federation and World Obesity Federation. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2218–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; da Silva, M.; Bjørge, T.; Fritz, J.; Mboya, I.B.; Jerkeman, M.; Stattin, P.; Wahlström, J.; Michaëlsson, K.; van Guelpen, B.; et al. Body mass index and risk of over 100 cancer forms and subtypes in 4.1 million individuals in Sweden: The Obesity and Disease Development Sweden (ODDS) pooled cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 45, 101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.V.L.; Neta, A.d.C.P.d.A.; Ferreira, F.E.L.L.; de Araújo, J.M.; Rodrigues, R.E.d.A.; de Lima, R.L.F.C.; Vianna, R.P.d.T.; Neto, J.M.d.S.; O’flaherty, M. Predicting the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Brazil: A modeling study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1275167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamooya, B.M.; Siame, L.; Muchaili, L.; Masenga, S.K.; Kirabo, A. Metabolic syndrome: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic approaches. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [CrossRef]

- Reaven, G. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robberecht, H.; Bruyne, T.D.; Hermans, N. Biomarkers of the metabolic syndrome: Influence of selected foodstuffs, containing bioactive components. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Ngouo, A.T.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tianyi, F.-L.; Foka, A.J.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; et al. Geographic Distribution of Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components in the General Adult Population: A Meta-Analysis of Global Data From 28 Million Individuals. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 188, 109924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira Valadares, L.T.; de Souza, L.S.B.; Salgado Júnior, V.A.; de Freitas Bonomo, L.; de Macedo, L.R.; Silva, M. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Brazilian Adults in the Last 10 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defronzo, R.A. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2009, 58, 773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Szablewski, L. Changes in Cells Associated with Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resourcefiles/2021/07/IDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf.

- Prince, Y.; Davison, G.M.; Davids, S.F.G.; Erasmus, R.T.; Kengne, A.P.; Graham, L.M.; Raghubeer, S.; Matsha, T.E. The Relationship between the Oral Microbiota and Metabolic Syndrome. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.V.F.; da Silva, C.J.F.; Cataldi, T.R.; Labate, C.A.; Sade, Y.B.; Scapin, S.M.N.; Thompson, F.L.; Thompson, C.; Silva-Boghossian, C.M.D.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Proteomic and Metabolomic Interplay in the Regulation of Energy Metabolism During Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2025, 41, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, A.R.; Cantarel, B.L.; Lamendella, R.; Darzi, Y.; Mongodin, E.F.; Pan, C.; Shah, M.; Halfvarson, J.; Tysk, C.; Henrissat, B.; et al. Integrated Metagenomics/Metaproteomics Reveals Human Host-Microbiota Signatures of Crohn’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Silva, C.V.; da Silva, C.J.F.; Bacila Sade, Y.; Naressi Scapin, S.M.; Thompson, F.L.; Thompson, C.; da Silva-Boghossian, C.M.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Prospecting Specific Protein Patterns for High Body Mass Index (BMI), Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes in Saliva and Blood Plasma From a Brazilian Population. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2024, e202300238. [Google Scholar]

- Samodova, D.; Stankevic, E.; Søndergaard, M.S.; Hu, N.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Witte, D.R.; Belstrøm, D.; Lubberding, A.F.; Jagtap, P.D.; Hansen, T.; et al. Salivary proteomics and metaproteomics identifies distinct molecular and taxonomic signatures of type-2 diabetes. Microbiome 2025, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, S.J.; Araujo, M.Y.C.; dos Santos, L.L.; Romanzini, M.; Fernandes, R.A.; Turi-Lynch, B.C.; Codogno, J.S. Burden of metabolic syndrome on primary healthcare costs among older adults: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2024, 142, e2023215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, D.; Liu, C. Sources of Automatic Office Blood Pressure Measurement Error: A Systematic Review. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geloneze, B.; Vasques, A.C.J.; Stabe, C.F.C.; Pareja, J.C.; de Lima Rosado, L.E.F.P.; De Queiroz, E.C.; Tambascia, M.A. HOMA1-IR and HOMA2-IR Indexes in Identifying Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome: Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study (BRAMS). Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2009, 53, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.; Liu, Y.; Luo, G.; Yang, L. Dietary Magnesium Intake Affects the Vitamin D Effects on HOMA-Beta and Risk of Pancreatic beta-Cell Dysfunction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 84974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.V.F.; Sade, Y.B.; Scapin, S.M.N.; Leite, P.E.C.; da Silva-Boghossian, C.M.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Relevance of Obesity and Overweight to Salivary and Plasma Proteomes of Human Young Adults From Brazil. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 13981–14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santos, E.O.; Alves, N., Jr.; Dias, G.M.; Mazotto, A.M.; Vermelho, A.; Vora, G.J.; Wilson, B.; Beltran, V.H.; Bourne, D.G.; Le Roux, F.; et al. Genomic and Proteomic Analyses of the Coral Pathogen Vibrio Coralliilyticus Reveal a Diverse Virulence Repertoire. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.V.F.; Bacila Sade, Y.; Naressi Scapin, S.M.; da Silva-Boghossian, C.M.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Comparative Proteomics of Saliva of Healthy and Gingivitis Individuals From Rio de Janeiro. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2023, 17, e2200098. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnielli, C.M.; Macedo, C.C.S.; De Rossi, T.; Granato, D.C.; Rivera, C.; Domingues, R.R.; Pauletti, B.A.; Yokoo, S.; Heberle, H.; Busso-Lopes, A.F.; et al. Combining Discovery and Targeted Proteomics Reveals a Prognostic Signature in Oral Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Biswas, D.; Chauhan, A.; Saha, A.; Auromahima, S.; Yadav, D.; Nissa, M.U.; Iyer, G.; Parihari, S.; Sharma, G.; et al. A Large-Scale Targeted Proteomics of Serum and Tissue Shows the Utility of Classifying High Grade and Low Grade Meningioma Tumors. Clin. Proteom. 2023, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.C.; Gorenstein, M.V.; Li, G.Z.; Vissers, J.P.; Geromanos, S.J. Absolute Quantification of Proteins by LC-MSE: A Virtue of Parallel MS Acquisition. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2006, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Villén, J.; Gygi, S.P. The SCX/IMAC Enrichment Approach for Global Phosphorylation Analysis by Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrné, E.; Molzahn, L.; Glatter, T.; Schmidt, A. Critical Assessment of Proteome-Wide Label-Free Absolute Abundance Estimation Strategies. Proteomics 2013, 13, 2567–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, D.E.; Wiersma, W.; Jurs, S.G. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 5th ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; p. 756. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package ‘corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix, 2021.

- Stoessel, D.; Stellmann, J.-P.; Willing, A.; Behrens, B.; Rosenkranz, S.C.; Hodecker, S.C.; Stürner, K.H.; Reinhardt, S.; Fleischer, S.; Deuschle, C.; et al. Metabolomic Profiles for Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Stratification and Disease Course Monitoring. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.H.; Wang, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Hsu, K.-C.; Lee, T.-H. Machine Learning Approaches for Biomarker Discovery to Predict Large-Artery Atherosclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alladio, E.; Trapani, F.; Castellino, L.; Massano, M.; Di Corcia, D.; Salomone, A.; Berrino, E.; Ponzone, R.; Marchiò, C.; Sapino, A.; et al. Enhancing Breast Cancer Screening With Urinary Biomarkers and Random Forest Supervised Classification: A Comprehensive Investigation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 244, 116113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohart, F.; Gautier, B.; Singh, A.; Lê Cao, K.-A. mixOmics: An R Package for ‘omics Feature Selection and Multiple Data Integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghi, L.; DiMassa, V.; Harrington, A.; Lynch, S.V.; Kapila, Y.L. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontology 2000 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaouas, S.; Chala, S. The Oral Bacteriome. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, R.M.; Assafi, M.S. The association between body mass index and the oral Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes profiles of healthy individuals. Malays. Fam. Physician 2021, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.J.F.; Silva, C.V.F.D.; Cardoso, A.M.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Exploring clinical parameters and salivary microbiome profiles associated with metabolic syndrome in a population of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 175, 106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusleme, L.; Dupuy, A.K.; Dutzan, N.; Silva, N.; Burleson, J.A.; Strausbaugh, L.D.; Gamonal, J.; Diaz, P.I. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, D.J.; Marsh, P.D.; Watson, G.K.; Allison, C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Coaggregation in Anaerobe Survival in Planktonic and Biofilm Oral Microbial Communities during Aeration. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4729–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, J.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Tang, P.; Li, C.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Su, C.; Li, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum and its associated systemic diseases: Epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. J. Oral Microbiol. 2022, 15, 2145729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Gekara, N.O. The deubiquitinase MYSM1 dampens NOD2-mediated inflammation and tissue damage by inactivating the RIP2 complex. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Zhao, P.; Huang, S.; Song, Y.; Shereen, M.A.; et al. MYSM1 Represses Innate Immunity and Autoimmunity through Suppressing the cGAS-STING Pathway. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F.; Xi, W.; Zhang, T.; Gao, J.; Yang, F.; et al. MYSM1 inhibits human colorectal cancer tumorigenesis by activating miR-200 family members/CDH1 and blocking PI3K/AKT signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elding Larsson, H.; Lundgren, M.; Jonsdottir, B.; Cuthbertson, D.; Krischer, J.; DiAPREV-IT Study Group. Safety and efficacy of autoantigen-specific therapy with 2 doses of alum-formulated glutamate decarboxylase in children with multiple islet autoantibodies and risk for type 1 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, K.E.; Feduska, J.M.; Taylor, J.P.; Houp, J.A.; Botta, D.; Lund, F.E.; Mick, G.J.; McGwin, G.; McCormick, K.L.; Tse, H.M. GABA and Combined GABA with GAD65-Alum Treatment Alters Th1 Cytokine Responses of PBMCs from Children with Recent-Onset Type 1 Diabetes. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Mick, G.J.; Choat, H.M.; Lunsford, A.A.; Tse, H.M.; McGwin, G.G.; McCormick, K.L. A randomized trial of oral gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) or the combination of GABA with glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) on pancreatic islet endocrine function in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampe, C.S.; Maitland, M.E.; Gilliam, L.K.; Phan, T.-H.T.; Sweet, I.R.; Radtke, J.R.; Bota, V.; Ransom, B.R.; Hirsch, I.B. High titers of autoantibodies to glutamate decarboxylase in type 1 diabetes patients: Epitope analysis and inhibition of enzyme activity. Endocr. Pract. 2013, 19, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choat, H.M.; Martin, A.; Mick, G.J.; Heath, K.E.; Tse, H.M.; McGwin, G., Jr.; McCormick, K.L. Effect of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) or GABA with glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) on the progression of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children: Trial design and methodology. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 82, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louraki, M.; Katsalouli, M.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Kafassi, N.; Critselis, E.; Kallinikou, D.; Tsentidis, C.; Karavanaki, K. The prevalence of early subclinical somatic neuropathy in children and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes mellitus and its association with the persistence of autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) and islet antigen-2 (IA-2). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 117, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A.; Supuran, C.T.; Capasso, C. An overview on the recently discovered iota-carbonic anhydrases. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 1988–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, A.; Rashed, M.; Nocentini, A.; Bonardi, A.; Abd-Alhaseeb, M.M.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Veerakanellore, G.B.; Majrashi, T.A.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Elgendy, B.; et al. Identification of new 4-(6-oxopyridazin-1- yl) benzenesulfonamides as multi-target anti-inflammatory agents targeting carbonic anhydrase, COX-2 and 5-LOX enzymes: Synthesis, biological evaluations and modelling insights. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 2201407. [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, E.; Simões, C.; Rodrigues, L.; Costa, A.R.; Vitorino, R.; Amado, F.; Antunes, C.; do Carmo, I. Changes in the salivary protein profile of morbidly obese women either previously subjected to bariatric surgery or not. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 71, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthi, S.; Gopi, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Sarma, P.V.G.K. The Therapeutic Potential of 4-Methoxy-1-methyl-2-oxopyridine-3-carbamide (MMOXC) Derived from Ricinine on Macrophage Cell Lines Infected with Methicillin-Resistant Strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 2843–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarupa, V.; Chaudhury, A.; Krishna Sarma, P.V. Effect of 4-methoxy 1-methyl 2-oxopyridine 3-carbamide on Staphylococcus aureus by inhibiting UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide, peptidyl deformylase and uridine monophosphate kinase. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeka, P.M.; Badger-Emeka, L.I.; Thirugnanasambantham, K. Virtual Screening and Meta-Analysis Approach Identifies Factors for Inversion Stimulation (Fis) and Other Genes Responsible for Biofilm Production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Corneal Pathogen. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 12931–12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Y. Structural Insights into the Methylation of C1402 in 16S rRNA by Methyltransferase RsmI. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Gao, P.; Teng, Z.; Luo, X.; Peng, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Beyond a Ribosomal RNA Methyltransferase, the Wider Role of MraW in DNA Methylation, Motility and Colonization in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.D.; Peng, B.; Zheng, J. Studies on aminoglycoside susceptibility identify a novel function of KsgA to secure translational fidelity during antibiotic stress. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00853-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zou, L.; Lu, J.; Holmgren, A. Selenocysteine in mammalian thioredoxin reductase and application of ebselen as a therapeutic. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 127, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, H.C.; Yu, J.-J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Cap, A.P.; Chambers, J.P.; Guentzel, M.N.; Arulanandam, B.P. Thioredoxin-A is a virulence factor and mediator of the type IV pilus system in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsera, M.; Buchanan, B.B. Evolution of the thioredoxin system as a step enabling adaptation to oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, S.; Fang, Q.; Gu, H.; Hu, Y. The Thioredoxin System in Edwardsiella piscicida Contributes to Oxidative Stress Tolerance, Motility, and Virulence. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, R.T. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin target proteins: From molecular mechanisms to functional significance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1165–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).