Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Operating Principle and Rotor QZS Evaluation Mechanism

2.1. Operating Principle and Conditions

2.2. The Evaluation Mechanism of the Rotor QZS

2.3. Description of the Monolithic U-Shaped Cross-Section Rotor Configuration

3. Numerical Analysis and Parametric Design

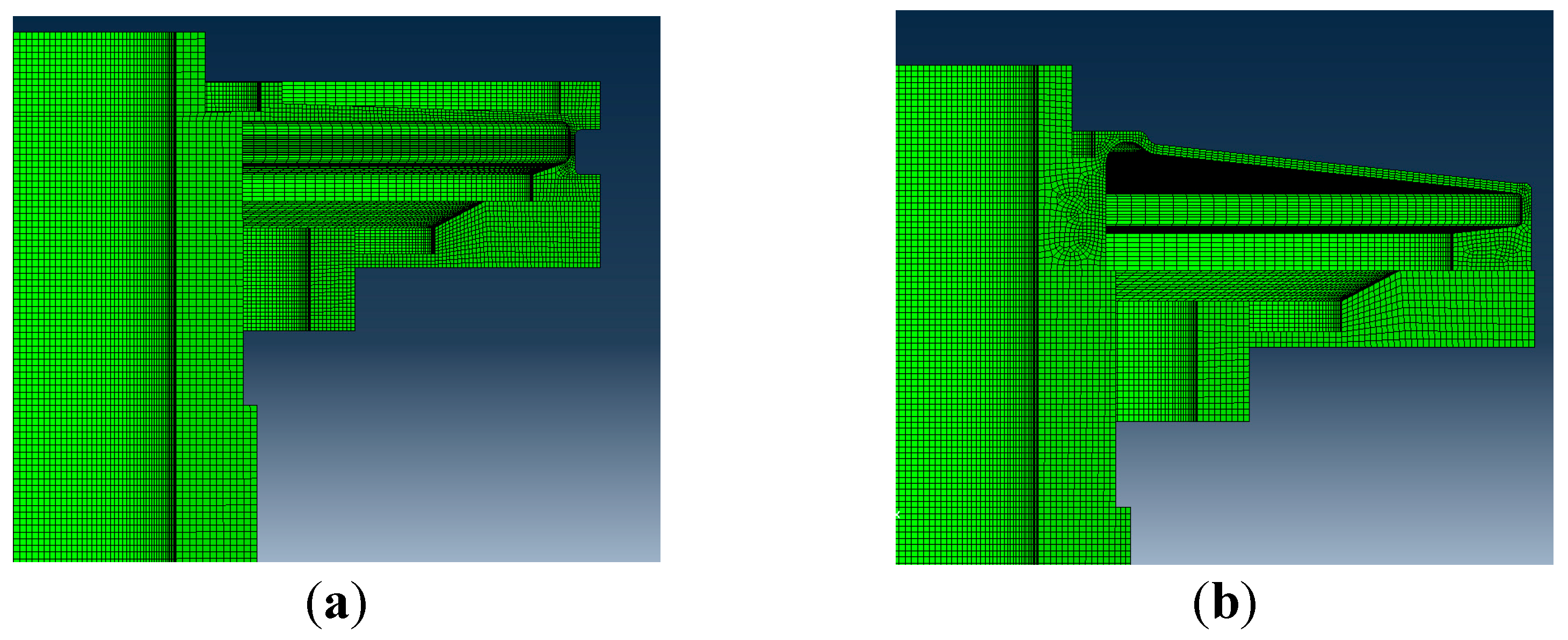

3.1. The FEM Analysis

3.2. Design of the Critical Control Parameters

4. Experiment Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lu, X.; Liu, W. Rapid motion of Janus Mg-based micromotors in urine environment by ultrasonic actuation. Colloid Surfaces A 2025, 718, 136932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Gao, M; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Miao, X. Performance evaluation of a novel disk-type motor using ultrasonic levitation: Modeling and experimental validation. Precis. Eng. 2024, 91, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difeo, M.; Pérez, N.; Castro, M.; Madrigal, J.; Rubio-Marcos, F.; Ramajo, L.; Cavalieri, F. Performance evaluation of lead-free potassium sodium niobate-based piezoceramics for ultrasonic motor design. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 13646–13653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yang, J.; Tang, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H. Optimization of flexible rotor for ultrasonic motor based on response surface and genetic algorithm. Micromachines-Basel 2025, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wang, L.; Li, P.; Liu, J. Preload multi-objective optimization method for ultrasonic motors based on NSGA-II. Processes 2024, 12, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y. Pre-pressure influences on the traveling wave ultrasonic motor performance: A theoretical analysis with experimental verification. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 115211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Che, S.; Chen, X.; Sun, H. Analysis of preload of three-stator ultrasonic motor[J]. Micromachines-Basel 2021, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Niu, R.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, C. Improving the efficiency of a hollow ultrasonic motor by optimizing the stator’s effective electromechanical coupling coefffcient. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 91, 016104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Gao, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Miao, X. Performance evaluation of a novel disk-type motor using ultrasonic levitation: Modeling and experimental validation. Precis. Eng. 2024, 91, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Q. Development of a novel resonant piezoelectric motor using parallel moving gears mechanism. Mechatronics 2024, 97, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yao, H.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z. Permanent magnet based nonlinear energy sink for torsional vibration suppression of rotor systems. Int. J. Nonlin. Mech. 2023, 149, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Hou, L.; Lin, R.; Chen, Y.; Saeed, N.; Fouly, A.; Awwad, E. On a quasi-zero stiffness vibration isolator with multiple zero stiffness points for mass load deviation. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 145, 116112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, G.; Wang, K. Miura-origami inspired quasi-zero stiffness low-frequency vibration isolator. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 295, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yao, H.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Jia, R. A track nonlinear energy sink with restricted motion for rotor systems. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 259, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, G.; Tao, Y. Nonlinear dynamics and vibration reduction properties of a quasi-zero stiffness magnetic isolator under translational and rotational coupling excitation. Mech. Syst. Signal Pr. 2025, 232, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Ji, J.; Ye, K.; Luo, Q. An innovative quasi-zero stiffness isolator with three pairs of oblique springs. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 192, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, G. A nonlinear quasi-zero stiffness vibration isolator with quintic restoring force characteristic: A fundamental analytical insight. J. Vib. Control 2023, 30, 4185–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chai, Y.; Miao, Z.; Li, F. Enhanced design of X-shaped structure for ultra-low-frequency nonlinear vibration isolation. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dy. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Tan, X.; Wu, J.; He, H. The influence of quasi-zero stiffness system parameters on response stability under quasi-periodic excitation. Nonlinear Dynam 2025, 113, 19241–19257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, G.; Wen, H.; Jin, D.; Hu, H. Design and analysis of a vibration isolation system with cam-roller-spring-rod mechanism. J. Vib. Control 2022, 28, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Analytical and experimental investigation of a high-static-low-dynamic stiffness isolator with cam-roller-spring mechanism. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 186, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Che, J.; Chen, X.; Jiang, W. Design of a combined magnetic negative stiffness mechanism with high linearity in a wide working region. Sci. China Technol. Sc. 2022, 65, 2127–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Pan, H.; Gao, J.; Lin, Q.; Tan, D. A torsion quasi-zero stiffness harvester-absorber system. Acta Mech. Sinica-Prc. 2025, 41, 524252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Gao, R. A bidirectional quasi-zero stiffness metamaterial for impact attenuation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 268, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Gao, R.; Tian, X.; Liu, S. A quasi-zero-stiffness elastic metamaterial for energy absorption and shock attenuation. Eng. Struct. 2023, 280, 115687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Gao, R.; Tian, X.; Liu, S. A 3D metamaterial with negative stiffness for six-directional energy absorption and cushioning. Thin Wall. Struct. 2022, 180, 109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jian, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, J. Design and optimization of Quasi-zero-stiffness rotor for disc ultrasonic motor. Piezoelectrics & Acoustooptics 2019, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Ma, S.; Shen, X.; Chen, L. Design of travelling-wave rotating ultrasonic motor under high overload environments: Impact dynamics simulation and experimental validation. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Lang, J.; Slocum, A. A curved-beam bistable mechanism. J. Microelectromech. S. 2004, 13, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Guo, S.; Tian, X.; Liu, S. A negative-stiffness based 1D metamaterial for bidirectional buffering and energy absorption with state recoverable characteristic. Thin Wall. Struct. 2021, 169, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Z.; Vo, D.; Suttakua, P.; Atroshchenko, E.; Bui, T.; Rungamornrat, J. Peridynamic formulations for planar arbitrarily curved beams with Euler-Bernoulli beam model. Thin Wall. Struct. 2024, 204. 112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Luo, Q.; Tong, L. Topology optimization for metastructures with quasi-zero stiffness and snap-through features. Compu. Method Appl. M. 2025, 434, 117587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh I | Mesh II | Mesh III | Mesh IV | |

| Number of grids | 148,000 | 201,500 | 298,500 | 405,500 |

| Mechanical response of the maximum stress (MPa) | 769.2 | 785.9 | 788.0 | 789.13 |

| 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).