1. Introduction

The last decade has witnessed a surge in the development of non-invasive brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), driven by the convergence of low-cost biosensor technology, embedded intelligence, and ubiquitous connectivity. As clinical and consumer applications expand, BCI systems are now tasked not only with capturing high-fidelity neural and physiological signals, but also with ensuring real-time analysis, robust cloud integration, and scalable deployment outside traditional laboratory environments. Recent surveys of wireless and wearable BCI technologies highlight both the feasibility of mobile brain monitoring and the persistent engineering constraints that emerge outside controlled environments, particularly artefact sensitivity, variable electrode contact quality, and deployment heterogeneity [

1]. In parallel, the maturation of edge computing in healthcare has enabled low-latency preprocessing and anomaly detection closer to the point of acquisition, reducing reliance on continuous high-bandwidth streaming while supporting real-time responsiveness for safety-critical or assistive applications [

2]. These evolving demands highlight persistent challenges—latency, artifact robustness, and seamless edge–cloud orchestration—that must be addressed to unlock the full translational potential of portable biosensor platforms. The following subsections review the background, significance, and research objectives that frame the present work.

1.1. Background and Significance

BCIs are designed to establish direct communication pathways between neural activity and external systems, enabling control and monitoring without reliance on peripheral neuromuscular output [

3,

4]. Within the spectrum of non-invasive modalities, electroencephalography (EEG) has historically dominated due to its millisecond temporal resolution, affordability, and long-standing clinical use [

5]. Studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in neuroprosthetic applications and rehabilitation, marking it as the canonical entry point for BCI research [

6]. However, reliance on a single modality such as EEG imposes constraints in terms of artifact susceptibility, limited spatial resolution, and reduced robustness outside controlled settings, leading to growing interest in hybrid and multimodal BCI approaches integrating additional electrophysiological or hemodynamic signals [

7].

Beyond EEG, other electrophysiological modalities have been widely explored to extend the functional scope and robustness of non-invasive BCIs. Electromyography (EMG) and electrooculography (EOG) provide complementary signals by capturing muscle activity and ocular movements, respectively, enabling reliable intent detection in applications such as prosthetic control, speller systems, and assistive interfaces [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Hybrid EEG–EMG and EEG–EOG frameworks have been shown to improve control reliability and reduce ambiguity compared to unimodal EEG systems, particularly in real-world and low-signal-quality settings, where peripheral or ocular cues can reinforce cortical intent decoding [

12,

13].

A second tier of physiological adjuncts supports these core neural modalities. Electrocardiography (ECG) and galvanic skin response galvanic skin response / electrodermal activity (GSR/EDA) are frequently integrated to provide autonomic and affective context, improving resilience in multimodal classifiers [

14,

15]. Photoplethysmography (PPG), while not a direct neural measure, offers heart-rate variability features that enrich assessments of stress and fatigue, particularly in IoT-enabled wearable systems [

16]. These adjuncts act as contextual layers rather than primary BCI channels.

Despite advances in sensing modalities, existing systems face persistent challenges in latency, scalability, and seamless integration with distributed cloud infrastructures [

17,

18]. Current commercial wearables, although accessible, often suffer from noisy signals, limited reliability, and poor suitability for clinical-grade applications [

19]. These gaps underscore the need for architectures that combine multimodal signal acquisition with robust edge preprocessing and cloud-aware data pipelines, ensuring both performance and scalability in translational contexts.

1.2. Research Objectives and Scope

At the edge, the system employs lightweight preprocessing and TinyML-based inference [

20,

21] on an RP2040 microcontroller, consistent with recent advances in embedded machine learning for biosignal analytics [

22]. This design enables deterministic, window-bounded inference suitable for near-real-time BCI interaction, while preserving strict energy and resource constraints typical of wearable platforms. Data are transmitted either via WiFi module of Nano Connect or via ESP32 Vajravegha LTE module to a cloud-based pipeline comprising Redis for near-real-time buffering, PostgreSQL for structured analytics, and AWS S3 with Glacier for archival storage, reflecting established practices in scalable IoT healthcare infrastructures [

23]. This architecture separates time-critical edge inference from cloud-assisted analytics and storage, preserving raw biosignal fidelity while enabling downstream processing at scale. The objectives of this work are twofold:

To validate that a fully implemented physical prototype can achieve deterministic edge-level inference and robust end-to-end operation interacting with the cloud under realistic connectivity conditions, including bounded packet loss and latency variability.

To demonstrate a scalable and modular system architecture that remains cost-efficient through staged deployment strategies, including local development, simulated cloud testing, and targeted cloud benchmarking.

By addressing persistent challenges related to latency variability, scalability, and reliable cloud integration, the proposed architecture establishes a foundation for translational BCI systems and large-scale neuroinformatics workflows[

24,

25]. Future extensions will explore advanced edge-resident and cloud-based machine learning techniques using electrophysiological datasets aligned with non-invasive BCI modalities, enabling longitudinal analysis and model refinement beyond the scope of the present study.

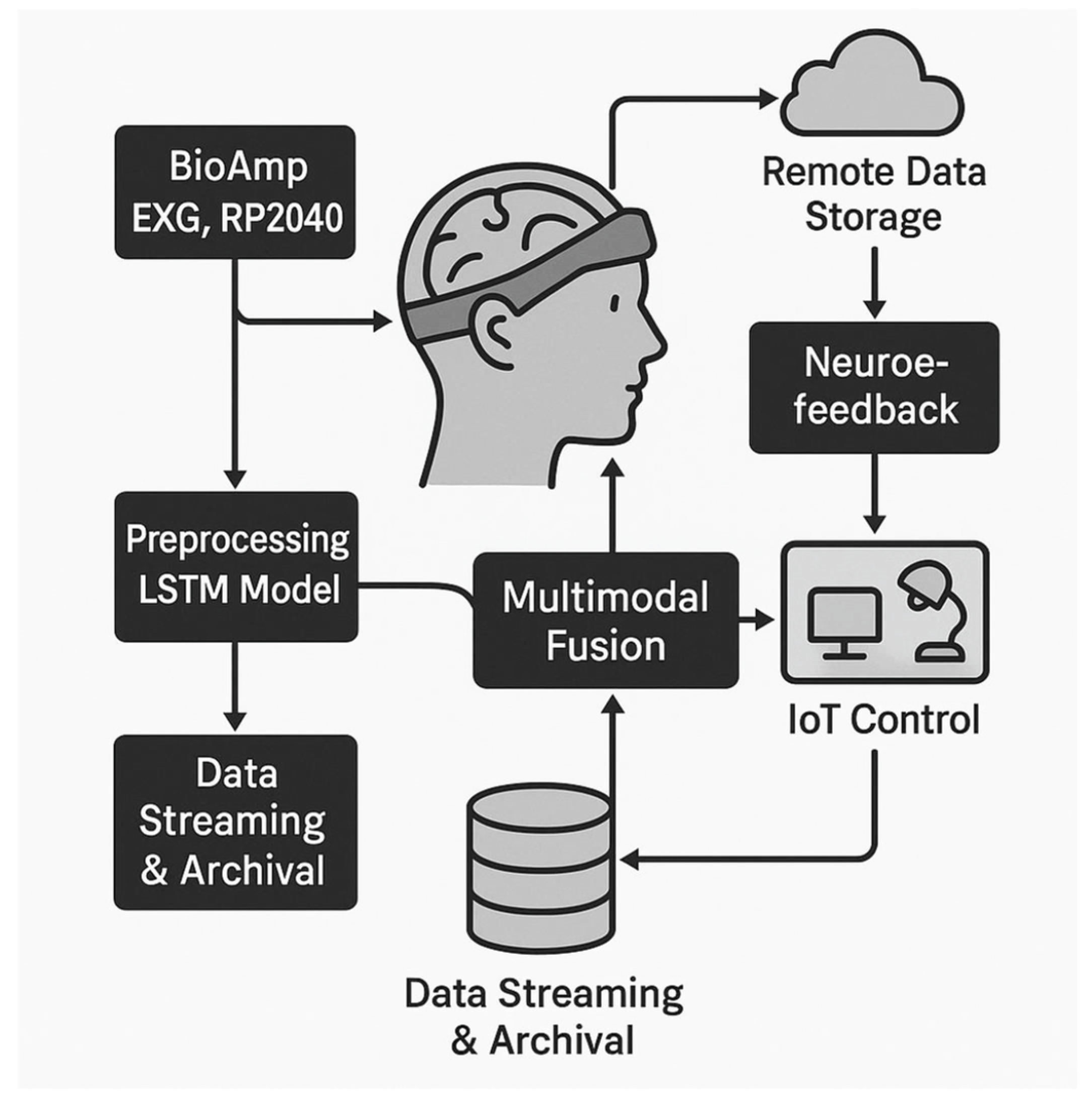

Figure 1 summarizes the proposed architecture, highlighting the flow of biosignal data from acquisition through edge preprocessing to cloud integration. The design emphasizes low-latency, window-bounded edge inference on the RP2040, supported by embedded inference toolchains suitable for resource-constrained TinyML deployment, and tiered cloud storage to ensure both near-real-time responsiveness and scalability in IoT healthcare deployments [

26,

27,

28]. Neural and electrophysiological signals are acquired through the BioAmp EXG module (EEG, EMG, EOG, ECG), while complementary modules provide supporting physiological and environmental context including DHT11 for temperature/humidity, and MQ-x (MQ-135 in the prototype, configured to be easily hot-swappable with other MQ sensors) which provides broad-spectrum sensitivity to volatile organic compounds (VOCs), alcohol vapours, ammonia, benzene-type gases, and variations in indoor air quality), all interfaced to enable multimodal acquisition within a portable prototype [

29,

30,

31]. This study aspires to use the RP2040 microcontroller as a novel platform for creating cost effective BCIs. Auxiliary modules are also augmented such as an optical pulse sensor from the MAX3010x family support heart rate and perfusion estimation. These components collectively provide a practical foundation for on-device signal acquisition, embedded analytics, and cloud integration within a controlled research and prototyping setting, while acknowledging that the present hardware is not intended for clinical diagnostics or hazardous-environment certification.

Preprocessing and lightweight classification at the edge reduce noise and extract salient features prior to uplink, separating time-critical inference from cloud-assisted analytics and archival [

32]. The resulting streams are transmitted into a tiered data management system for near-real-time buffering and long-term storage [

33]. These data are relayed to cloud storage for large-scale analysis and longitudinal retention, while feedback may be returned to the user via neurofeedback or interaction channels depending on the application context. In parallel, detected patterns can be mapped to device-level or application-level control signals, thereby closing the loop between acquisition, contextual interpretation, and actuation.

By distinguishing core electrophysiological modalities from supporting adjuncts, the framework remains multimodal while staying faithful to the prototype’s sensing stack and portability constraints [

34]. The modular pipeline supports staged deployment, enabling purely local operation during development while retaining the ability to scale into cloud-assisted analytics for benchmarking and translational studies. To generalize the architecture beyond its prototype implementation, this work introduces the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) framework. RCG is structured into four modular layers: RCG Cortex, responsible for edge-level preprocessing and lightweight TinyML inference; RCG Gateway, which manages secure data uplink through LTE-enabled controllers; RCG Vault, dedicated to structured and archival cloud storage; and RCG Dash, encompassing visualization, dashboards, and alerting mechanisms. Together, these components establish a portable yet extensible framework that accommodates both multimodal biosignal inputs alongside environmental adjuncts of temperature, humidity, and ambient gas concentrations, providing contextual enrichment and clinical relevance. The conceptual model positions the system as both a validated prototype and a scalable blueprint for broad BCI applications, where modular deployment ensures adaptability across research and translational domains [

35].

2. Related Work

The evolution of BCI systems has been shaped by rapid advances in biosensor hardware, embedded analytics, and cloud-enabled infrastructure. Recent years have witnessed a convergence of engineering and neuroscience, where the deployment of portable, multimodal biosensors—coupled with real-time data pipelines—has transformed the landscape of cognitive state monitoring, neuroprosthetics, and translational neuroinformatics. Parallel progress in edge computing, wireless telemetry, and scalable storage solutions has enabled the development of systems that are not only more responsive and energy-efficient, but also increasingly accessible beyond the confines of laboratory settings. Against this backdrop, the following sections examine prior art spanning biosensor modalities, embedded intelligence, IoT healthcare architectures, and hybrid edge–cloud frameworks, laying the foundation for the unique contributions of the present work.

2.1. Overview of Core Non-Invasive BCI Modalities Under Consideration

Non-invasive BCI systems have primarily evolved around a set of well-established sensing modalities, each contributing distinct advantages and limitations. EEG remains the dominant channel, valued for its high temporal resolution and affordability, and it has been widely applied in neuroprosthetics, rehabilitation, and emotion recognition [

36,

37]. Despite this ubiquity, EEG suffers from limited spatial specificity and susceptibility to artefacts, which has encouraged the development of complementary sensing and hybrid control strategies.

EMG extends BCI capability beyond purely neural activity by enabling intent detection through muscular activation patterns. EMG-based systems are particularly effective for prosthetic control and distributed frameworks that combine motor and neural information [

38]. Similarly, EOG leverages ocular activity, including blinks and saccades, to support spellers, cursor control, and multimodal interaction, especially in assistive HCI contexts.

In addition to these core modalities, a second tier of physiological adjuncts has been incorporated into multimodal designs. ECG provides cardiac context relevant for fatigue and stress monitoring, while GSR/EDA offers markers of arousal and attentional modulation. PPG, widely embedded in wearable devices, supplies heart-rate variability indices that serve as contextual correlates and help in artefact removal rather than direct neural inputs [

39]. These adjunct signals enrich classification frameworks by embedding autonomic dynamics, but they are rarely used as standalone BCI channels [

40,

41].

Collectively, the integration of EEG, EMG, EOG, and adjunct signals such as ECG, GSR, and PPG defines the current landscape of portable, non-invasive BCI systems. However, while multimodal designs improve robustness, many existing implementations remain fragmented, often lacking scalable pipelines that reliably bridge acquisition, real-time analytics, and cloud-based storage. This gap underscores the need for unified architectures capable of sustaining both performance benchmarks and translational applicability.

2.2. Role of Cloud and Edge Computing in Biosensors

The rapid growth of wearable and portable biosensors has intensified the need for architectures that can deliver low-latency decision support, high-throughput ingestion, and secure longitudinal storage without collapsing under bandwidth, cost, and privacy constraints. Cloud-only pipelines, where continuous raw streams are pushed upstream for every analytic step, can introduce avoidable delays and network bottlenecks, which is especially problematic for time-sensitive BCI-adjacent workflows and closed-loop feedback. Surveys on healthcare edge computing consistently highlight this latency–bandwidth tension as a core driver for pushing computation closer to the signal source. To mitigate these constraints, edge computing has evolved from simple thresholding into a practical layer for signal conditioning, lightweight inference, and event-triggered transmission. TinyML literature emphasizes that local inference reduces dependence on round-trip cloud connectivity and thereby avoids cloud-induced latency for many IoT-class scenarios [

42]. In parallel, embedded biosignal work on wearables demonstrates that real-time classification is feasible under tight power budgets when models are quantized and engineered for constrained processors; for instance, TEMPONet-style [

43] temporal convolutional pipelines have been implemented on ultra-low-power multicore IoT processors with per-window inference on the order of milliseconds, illustrating what “edge-real-time” can look like in practice for muscular intent streams [

44]. The broader implication for biosensor systems is architectural: edge layers should absorb the “always-on” work (denoising, segmentation, compression, early warnings), while the cloud absorbs the “deep and wide” work (population-scale learning, model retraining, cohort analytics, and durable governance) [

45]. Meanwhile, cloud infrastructure remains indispensable for (i) scalable, long-term data management and (ii) computationally heavy neuroinformatics workflows. Cloud brainformatics platforms illustrate the value of centralized compute and storage for EEG big-data exploration and analysis, where the cloud is not just a bucket but an ecosystem for reuse, collaboration, and high-performance processing [

46]. This becomes more relevant when systems are designed to interoperate with large public datasets and benchmarking ecosystems (e.g., TUH EEG [

47] for large-scale clinical EEG, and ADNI [

48] for longitudinal neuroimaging and biomarker trajectories), which implicitly demand robust storage, indexing, and access control patterns. From a pipeline-design viewpoint, hybrid edge–cloud stacks commonly adopt a tiered persistence model:

A fast buffer for “right-now” windows (often an in-memory time-series store),

A structured store for queryable longitudinal slices, and

An object/archive layer for raw session artifacts and cold retention.

For example, Redis natively supports time-series data handling as a first-class pattern for timestamped sensor points, making it a practical fit for transient buffering and short-horizon aggregation. For longer-horizon analytics, PostgreSQL-based time-series extensions (e.g., TimescaleDB) are explicitly designed for large volumes of timestamped IoT/sensor readings while retaining SQL semantics, which is useful when you want biomedical metadata joins and audit-friendly schemas. Finally, cloud object storage and archival tiers (such as, Amazon S3 with Glacier classes) formalize cost-aware retention, where “cold” biosignal payloads can be stored with durable, policy-driven retrieval characteristics rather than sitting in expensive hot storage forever. Despite this maturity, the literature still shows a recurring fragmentation: some systems over-optimize edge latency while under-designing interoperability and data governance, whereas others centralize everything in the cloud and inherit avoidable delay, bandwidth waste, and operational cost [

49,

50]. This motivates architectures that are cloud-aware by design, not cloud-dependent: edge intelligence should be treated as the default for immediacy and resilience, while cloud services should be treated as the amplifier for scale, reproducibility, and translational deployment.

2.3. Limitations of Existing Biosensor Frameworks

Although substantial progress has been reported across wearable and portable BCI-oriented sensing, many existing biosensor systems remain constrained by architectural and deployment realities. Consumer-grade wearables and low-cost EEG headsets improve accessibility, yet commonly face practical limitations in signal quality, electrode coverage, and robustness under unconstrained, real-world conditions, which can reduce reliability for translational or clinically adjacent use-cases.

While multimodal and hybrid designs can improve decoding stability, they are frequently validated in controlled settings and remain difficult to scale into reproducible, field-deployable systems without strong attention to calibration, artefact resilience, and operational constraints [

51,

52,

53]. Efforts to integrate biosensors with IoT infrastructures demonstrate clear promise, but many reported frameworks still lack tiered pipelines that simultaneously support low-latency edge responsiveness, structured queryable storage, and cost-aware long-horizon archival. Architectures that over-rely on cloud connectivity inherit bandwidth pressure and latency sensitivity, whereas purely edge-centric designs struggle to support population-scale analytics, cross-session reproducibility, and integration with large longitudinal resources [

24,

59]. A further limitation is the absence of consistently adopted design and data standards, which contributes to fragmented deployments and weak interoperability across devices, vendors, and datasets. As a result, benchmarking is often confined to isolated case studies or narrow evaluation settings, rather than scalable validation across heterogeneous acquisition conditions and multi-site data [

54,

55].

Collectively, these shortcomings motivate unified frameworks that treat portability, multimodal integration, and hybrid edge–cloud intelligence as a single end-to-end system problem, enabling reproducible deployment pathways aligned with translational biosensor applications in healthcare and neuroengineering [

56,

57,

58].

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the end-to-end implementation pathway of the proposed biosensor platform, structured to maximize reproducibility across acquisition, embedded processing, and cloud persistence. We first describe the system architecture as a tiered edge–cloud design that assigns latency-critical operations (signal conditioning, event detection, lightweight inference, and bandwidth shaping) to the edge, while reserving scalable functions (long-horizon storage, cohort analytics, visualization, and lifecycle management) for the cloud, consistent with established edge–cloud patterns in healthcare monitoring systems. We then specify the hardware components and instrumentation choices that enable portable deployment, followed by the software stack responsible for orchestration, data transport, and storage. Finally, we formalize the data acquisition and preprocessing pipeline, including artefact-aware handling steps needed for wearable-grade recordings under unconstrained conditions, thereby ensuring that the downstream analytics remain interpretable and comparable across sessions [

59,

60].

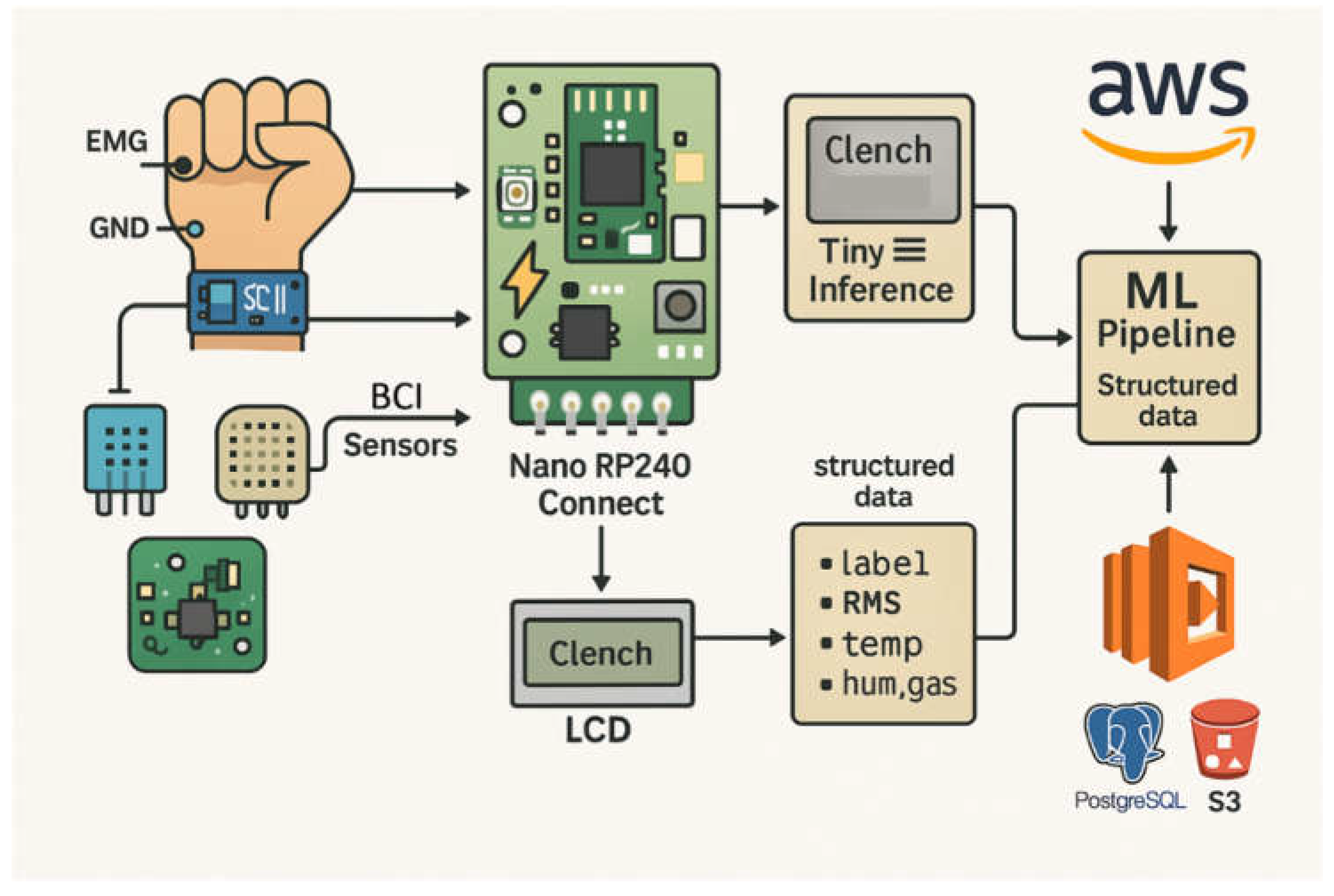

3.1. System Architecture

The proposed system was implemented as a physical prototype to validate the feasibility of a cloud-aware multimodal biosensor pipeline. The design followed a layered architecture that combined portable acquisition hardware, embedded edge analytics, and scalable cloud infrastructure [

61]. At the acquisition layer, neural and physiological signals were captured using the BioAmp EXG Pill interfaced with an RP2040 microcontroller. This configuration enabled real-time recording of EEG, EMG, and EOG signals, with an option to extend to additional channels for multimodal fusion [

62,

63]. The RP2040 performed lightweight preprocessing steps including filtering, root mean square (RMS) calculation, and spectral transforms such as fast Fourier transform (FFT).

For local analytics, the RP2040 executed TinyML inference models compiled into C header files, supporting on-device classification of brain states and motor intent [

21,

29]. In parallel, raw and preprocessed signals were buffered on an SD card for redundancy and offline analysis. The communication layer was managed by on-board Nano Connect WiFi module or ESP32 Vajravegha LTE module, which provided secure data uplink via HTTPS and MQTT protocols. To reduce bandwidth demands, the module transmitted structured packets containing key features and classification outputs, while complete raw signals were stored locally. [

64,

65]

On the cloud side, a tiered pipeline was implemented. Redis served as a low-latency buffer for the first few seconds of signal streams, enabling real-time visualization and anomaly detection [

66,

67]. PostgreSQL stored structured datasets for analytics and model training, while AWS S3 and Glacier provided long-term archival of session files. Visualization was supported through Python-based graphical interfaces, Grafana dashboards, and an on-device Nokia 5110 LCD for immediate feedback. This modular architecture demonstrated interoperability across acquisition, processing, transmission, and storage layers, ensuring that both prototype validation and translational scalability were addressed.

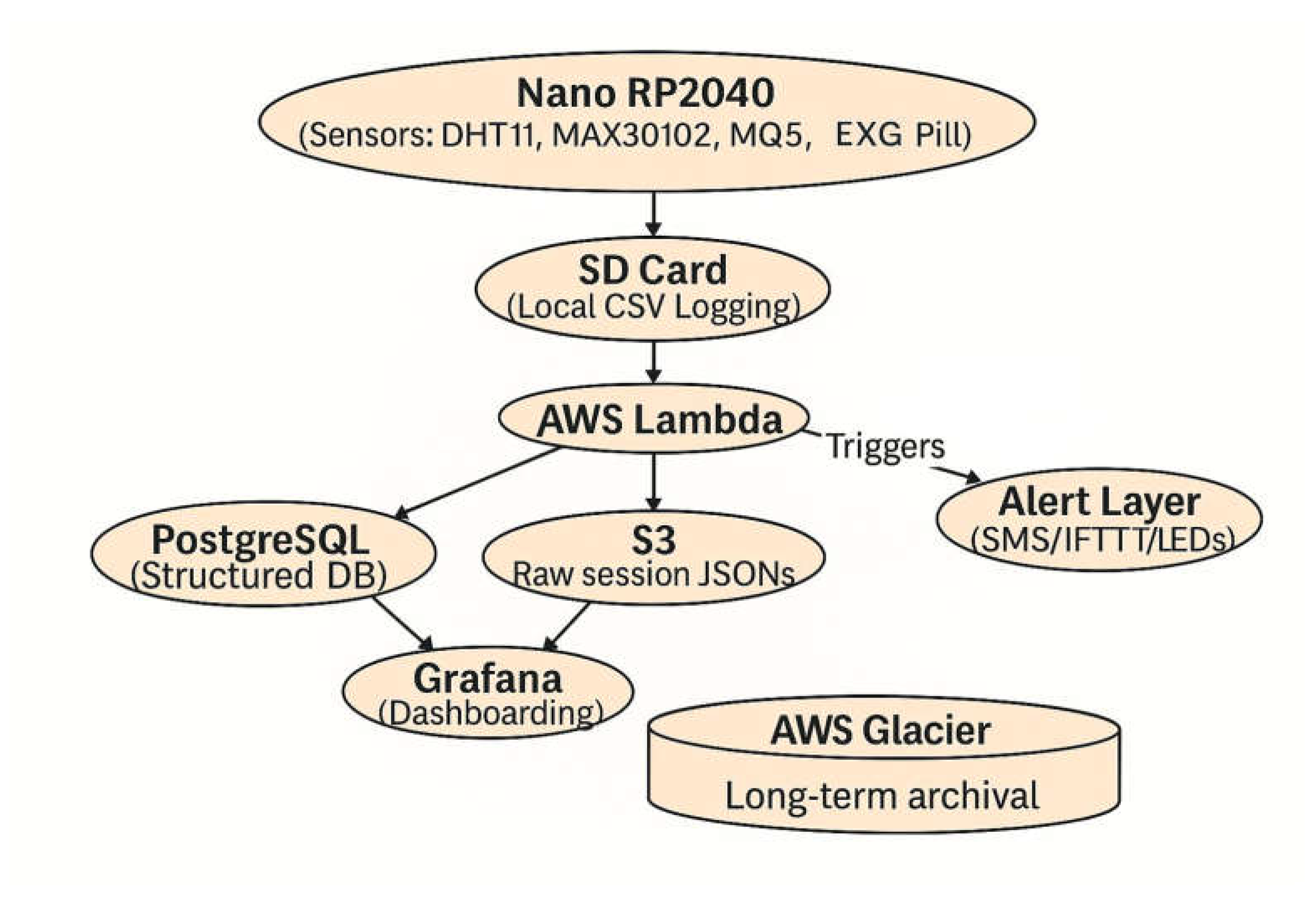

Figure 3 summarizes the layered edge–cloud implementation, showing multimodal acquisition using three BioAmp EXG Pill units configured for EEG, EMG, and EOG, followed by preprocessing and TinyML inference on the RP2040. Environmental sensing (DHT11 for temperature and humidity; MQ-135 for ambient air-quality proxy) is co-sampled as auxiliary context to support deployment-aware interpretation and logging [

46]. At the edge, the node provides immediate LCD feedback and SD-card buffering, while structured packets (features, context values, and inference outputs) are forwarded via the available uplink (WiFi or LTE, depending on network availability) to AWS, where PostgreSQL supports structured analytics and S3 provides long-term archival [

32,

68,

69].

The layered workflow can be mapped to the RCG abstraction introduced earlier. In this implementation, RCG Cortex corresponds to the RP2040-based edge preprocessing and TinyML inference; RCG Gateway is realized through WiFi/LTE module (depending on network availability) handling secure transmission; RCG Vault is represented by PostgreSQL, S3, and Glacier providing structured and archival storage; and RCG Dash encompasses Redis-driven streaming, Grafana dashboards, and LCD-based feedback. Embedding the RCG terminology in this build highlights the modularity of the design without introducing redundancy or conceptual overhead.

3.2. Hardware Components

The physical prototype was assembled from commercially available microcontrollers, biosignal amplifiers, and environmental sensors.

Table 1 summarizes the key components and their roles within the system architecture.

This hardware ensemble enabled simultaneous acquisition of neural, muscular, cardiac, and environmental signals. Each module contributed to the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) abstraction, ensuring that edge analytics, secure transmission, structured storage, and visualization were consistently represented.

3.3. Software Stack

The software pipeline was implemented as a hybrid of embedded firmware, data processing scripts, and cloud-based services, enabling seamless communication across acquisition, edge analytics, and storage layers. The stack is designed to accommodate additional preprocessing or classification routines, and supports rapid integration of new biosignal modalities or context sensors as the hardware platform evolves

At the device level, the Nano RP2040 Connect was programmed using the Arduino IDE and PlatformIO framework, with support libraries for SPI, I²C, and analog signal acquisition. Preprocessing routines implemented in C included bandpass filtering, root mean square (RMS) extraction, and fast Fourier transform (FFT). TinyML models were trained in Python using scikit-learn and TensorFlow Lite [

70], converted to .tflite format, and compiled into .h header files for integration into the RP2040 firmware [

71,

72].

For secure uplink, HTTPS and MQTT protocols were employed, supported by embedded SSL/TLS libraries. Structured payloads were encoded in JSON and transmitted to AWS endpoints. A Lambda function parsed the payloads, routing structured entries into PostgreSQL and archiving complete session files into Amazon S3. Lifecycle policies ensured automated migration of older data into Glacier for cost-efficient archival [

73].

Visualization and monitoring were achieved through Python-based graphical interfaces during development and Grafana dashboards during deployment. Redis served as a low-latency streaming buffer to feed Grafana panels, providing near real-time visualization of incoming biosignals. Local feedback was delivered through the Nokia 5110 LCD, while Python GUI scripts facilitated early-stage debugging and offline inspection.

3.4. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Biosignals were acquired using the BioAmp EXG Pill connected to surface electrodes. The module supports single-channel acquisition of EEG/EOG by default and can be configured for EMG/ECG via hardware bridging, enabling modality switching while retaining the same analog front-end chain. For EMG validation, electrodes were positioned over the forearm flexor muscle group to capture clench and relaxation activity. For ECG feasibility checks, a Lead-I style configuration was used as a reference placement approach. EEG feasibility was assessed using conservative frontal placements, acknowledging that signal quality is strongly influenced by electrode type, impedance, and motion artifacts in non-shielded wearable setups.

Signal acquisition was configured at 1 kHz in firmware. On the Nano RP2040 Connect, analogRead() returns 10-bit values by default and can be increased to 12-bit using analogReadResolution(12). The underlying RP2040 platform provides a 12-bit ADC with sufficient headroom for kHz-rate sampling in principle; however, the effective sampling behavior remains implementation-bounded by the firmware loop and buffering strategy. Raw biosignals were logged locally to an SD card for redundancy and offline inspection, while time-stamped feature packets were emitted for near-real-time visualization and cloud ingestion.

Edge preprocessing on the RP2040 applied task-appropriate filtering and feature extraction. For EEG/ECG feasibility, a low-frequency bandpass commonly used in non-invasive BCI preprocessing was adopted (e.g., ~0.5–35/45 Hz) to reduce baseline drift and high-frequency noise while preserving task-relevant rhythms. For surface EMG, bandpass filtering in the ~20–450/500 Hz range was used as a standard artifact/noise suppression practice, optionally combined with notch-based powerline mitigation where required by the recording environment. Time-domain features (e.g., RMS, variance) and short-window spectral features (FFT-derived bandpower summaries) were computed to support lightweight classification under wearable compute constraints.

For embedded inference, extracted feature vectors were passed to a quantized TinyML classifier deployed on the RP2040. Because end-to-end responsiveness is window-bounded, the interaction latency is governed primarily by the chosen feature window and update rate rather than any single “per-cycle” compute number; therefore, this work reports deterministic, window-bounded behavior rather than claiming a fixed millisecond inference constant without device benchmarking [

74].

During cloud-assisted validation, structured packets containing feature summaries and contextual sensor values (temperature/humidity, PPG proxies, air quality) were forwarded to the cloud pipeline for storage and downstream model refinement, while raw traces were retained locally and/or archived as session files depending on bandwidth and connectivity conditions. This design reduces uplink payload size while preserving raw-signal recoverability for later audit and reprocessing.

Figure 4 depicts the data flow underlying the proposed system. Signals from the Nano RP2040, integrated with BioAmp EXG and environmental sensors (DHT11, MAX30102, MQ-series), are buffered locally on an SD card in CSV format. Processed data packets are forwarded to AWS Lambda, which serves as the orchestration layer for routing. Structured features are inserted into PostgreSQL for analytics, while raw session logs are archived in S3 and subsequently migrated to Glacier for long-term storage. Visualization is supported through Grafana dashboards, and real-time thresholds can trigger alerts via SMS, IFTTT, or LED indicators. This layered pipeline ensures redundancy, scalability, and clinical-grade data integrity by combining immediate feedback with longitudinal archival.

4. Results

The performance and versatility of the proposed BCI biosensor system were validated through a series of targeted experiments, encompassing latency and throughput benchmarks, real-time visualization tests, and feasibility assessments for multimodal integration. The following sections detail the empirical findings obtained across edge analytics, cloud-assisted workflows, and feedback pathways. Quantitative results are presented for core system metrics—latency, inference time, packet loss, and scalability—while qualitative insights highlight the robustness of visualization, user feedback, and environmental context sensing. The prototype was validated across (i) edge-bounded analytics, (ii) lte-assisted telemetry and cloud storage, and (iii) multi-layer feedback pathways. quantitative outcomes are summarized in table a (performance) and table b (latency budget), while table c provides an auditable example of the logged multimodal record structure used during sessions. Together, these results establish the operational viability and extensibility of the prototype, laying the groundwork for future translational deployments and large-scale neuroinformatics applications.

4.1. System Performance Benchmarks

Proto Prototype validation focused on assessing latency, throughput, and reliability of the edge-resident inference with cloud-assisted telemetry and storage. Edge inference on the RP2040, running quantized TinyML models for EMG-based clench detection, was typically 12–21 ms per inference cycle; however, the effective response latency from signal acquisition to user-visible update was dominated by the analysis window length (typically 250–1000 ms) together with uplink and visualization overhead. End-to-end delays, measured from acquisition through LTE uplink and cloud-side handling to dashboard update, averaged 1.3–2.1 s under steady conditions, with occasional spikes above 2.5 s attributable to network variability, serverless cold-start outliers, and dashboard refresh cadence. At the API layer, end-to-end request timing incorporates both backend integration time and gateway overhead as captured by the API Gateway latency metric definition.

Packet transmission reliability was evaluated under LTE uplink conditions using the ESP32 Vajravegha module. Across multiple sessions, delivery success exceeded 95% (packet loss <5%), supported by application-layer acknowledgements and retransmission (e.g., MQTT QoS-level retries). Local SD-card logging further safeguarded against connectivity disruptions, enabling recovery of full-resolution signals during temporary uplink failures.

As summarized in

Table 2, edge-side TinyML inference on the RP2040 remained low (12–21 ms), while the effective interaction latency was dominated by the selected analysis window (250–1000 ms) and by uplink and visualization overheads. End-to-end delay (acquisition → LTE uplink → cloud-side handling → dashboard visibility) was typically 1.3–2.1 s, with occasional excursions above 2.5 s consistent with cellular variability and serverless cold-start outliers. Cold starts occur when a new execution environment must be provisioned for a Lambda invocation after inactivity or scale-up events.

Where API-layer timing is reported, interpretation follows the API Gateway CloudWatch Latency metric definition, which includes backend integration time plus gateway overhead; this metric applies to the gateway segment and should not be conflated with dashboard refresh latency. Throughput testing supported concurrent telemetry at 1 Hz with event-driven burst transmissions, and raw session data were archived to Amazon S3 with lifecycle-based transitions to Glacier-class storage to demonstrate feasibility for long-term retention.

As shown in

Table 3, prototype validation focused on edge inference timing, end-to-end propagation delay, and uplink reliability under LTE conditions. edge-side TinyML inference on the RP2040 remained low (typically 12–21 ms per inference call), while the effective interactive latency from acquisition to user-visible update was governed primarily by the analysis window length (250–1000 ms) plus visualization and uplink overhead. end-to-end delay was typically 1.3–2.1 s, with sporadic excursions above 2.5 s, consistent with cellular variability and serverless cold-start outliers. cold starts arise when a new execution environment must be provisioned for a Lambda invocation after inactivity or scale-up events.

These results indicate that the system achieves low-latency edge inference and robust cloud integration; however, real-world end-to-end responsiveness remains governed primarily by windowing strategy and by uplink and visualization bottlenecks typical of cellular IoT and dashboard-based monitoring.

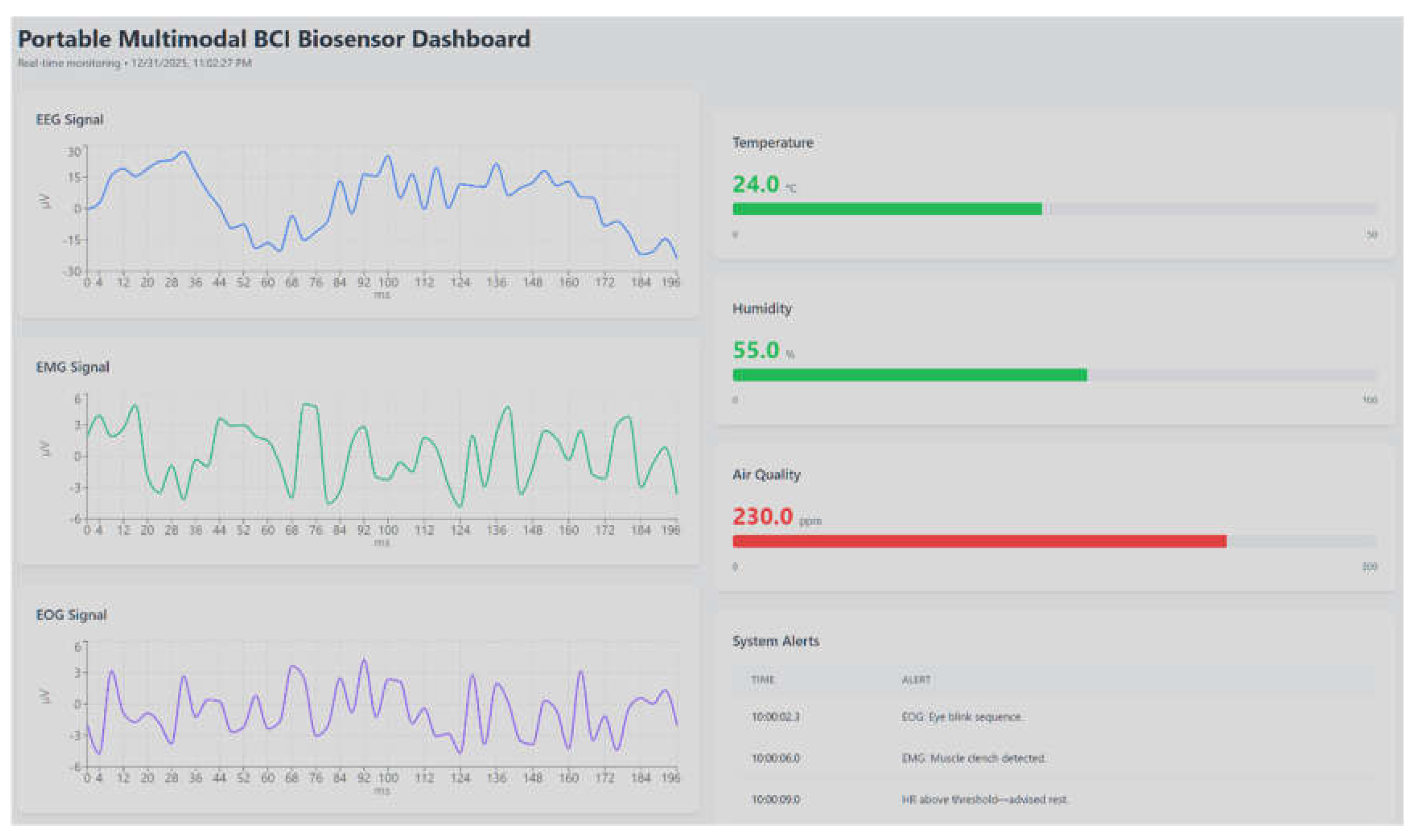

4.2. Visualization and Feedback Results

Visualization and user feedback were implemented at multiple layers of the architecture to validate responsiveness and interpretability. At the device level, the Nokia 5110 LCD displayed clench detection outcomes and contextual sensor values (temperature, humidity, air quality) with typical refresh latencies of 150–300 ms, providing immediate confirmation of system status during experimental sessions.

In parallel, dashboards connected to the signal buffer enabled near-real-time visualization of incoming data streams as shown in

Figure 5.

The dashboard illustrates simultaneous acquisition and visualization of EEG, EMG, and EOG signals (left panels, in µV over time), alongside contextual environmental parameters including temperature, humidity, and air quality (right panels). Detected events and threshold-based notifications are summarized in the system alert log, demonstrating integrated edge-level sensing, multimodal signal monitoring, and real-time feedback within the proposed architecture. Due to pipeline and panel refresh constraints, the dashboard-visible latency is governed by the configured refresh interval and network conditions; in the tuned setup used for validation it was typically on the order of seconds, while default Grafana configurations commonly enforce a minimum refresh interval unless explicitly lowered in server settings. Event-based EMG signals, environmental parameters, and system states were displayed in synchronized panels, supporting dynamic thresholding and anomaly monitoring [

75]. This dual-layer visualization validated both laboratory and potential remote (telemedicine) use cases.

The alert layer, configured through AWS Lambda triggers, successfully generated notifications via SMS and IFTTT integrations when defined thresholds were exceeded (e.g., sustained high EMG activity, elevated gas levels, or abnormal HRV patterns). LED-based alerts on the device delivered local, low-power feedback, ensuring rapid user notification even during network outages.

This multi-tier feedback approach demonstrated the system’s ability to deliver rapid, interpretable outputs at the edge while maintaining scalable, cloud-based dashboards for remote monitoring and analytic review.

5. Discussion

The present work demonstrates a modular, cloud-aware BCI biosensor platform, validated through physical prototyping and comprehensive performance benchmarks. By integrating real-time edge analytics, secure cloud pipelines, and contextual environmental sensing, the system addresses persistent limitations in scalability, latency, and multimodal flexibility found in prior art. The following sections dissect the key findings, situate the prototype against state-of-the-art systems, and explore both the immediate translational impact and future research directions enabled by this architecture. Limitations and avenues for further optimization are critically examined to inform the next generation of portable neuroengineering solutions.

5.1. Key Findings

This This study demonstrated the feasibility of a cloud-aware multimodal biosensor system through successful implementation and physical validation. The architecture achieved edge inference latencies typically 12–21 ms (consistently <100 ms), end-to-end acquisition-to-visualization delays averaging 1.3–2.1 s (with occasional higher outliers due to network or dashboard refresh), and maintained packet loss below 5% across multiple sessions, confirming that portable microcontrollers can deliver the responsiveness required for translational BCI applications [

76,

77].

The modular design enabled robust tiered data management: Redis provided near-real-time streaming for visualization, PostgreSQL structured analytics and model training datasets, and AWS S3/Glacier ensured long-term, automated archival. This combination balanced low-latency operation with scalable cloud integration, overcoming the limitations of purely edge- or cloud-dependent frameworks highlighted in prior art [

78,

79].

Visualization and feedback were validated at multiple levels: local LCD displays and LED alerts, remote Grafana dashboards, and cloud-based SMS/IFTTT notifications—all confirmed the system’s capacity for immediate user interaction and extensibility to remote healthcare or telemedicine scenarios.

The prototype further confirmed architectural extensibility: while EMG-based intent detection was the primary use case, preliminary EEG and ECG acquisition validated the hardware and pipeline for additional neural and physiological modalities. Environmental sensor integration highlighted the system’s capacity for adjunct contextual signals, further enriching classification and interpretation.

Collectively, these results establish the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) framework as a scalable, responsive, and extensible blueprint for portable biosensing—proving that a distributed architecture combining on-device inference with cloud-assisted analytics and archival can meet the dual demands of immediacy and scalability in next-generation BCI deployments.

5.2. Comparison with Existing Systems

Most existing portable BCI systems remain narrowly focused on single modalities, with EEG dominating both research prototypes and commercial devices [

1,

2,

3,

7,

12,

15]. While effective for selected applications, these platforms often suffer from high susceptibility to motion artifacts and limited spatial resolution, constraining their reliability outside laboratory settings. By contrast, the present system validated a multimodal configuration—EMG, EEG, ECG, and contextual adjuncts—delivered through a portable, microcontroller-based platform. This combination improves robustness, resilience to artifacts, and readiness for real-world deployments [

80].

To position the present prototype,

Table 4 contrasts the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) framework with representative categories of existing systems. EEG-only BCIs dominate but are limited by artifacts and poor portability. Earlier multimodal systems often remain fragmented, with restricted real-time capability or lack of scalable pipelines. IoT-enabled biosensors have introduced cloud-based storage and visualization [

84,

85]. but dependence on high-bandwidth connectivity leads to excessive latency and cost. Consumer-grade EEG wearables improve accessibility, but multiple validation and review studies report systematic signal-quality and SNR limitations relative to research-grade systems, which can constrain downstream analytics and clinical translation unless mitigated with robust preprocessing and task design. The RCG system stands apart: it delivers modular, portable design, validated low-latency edge inference, robust cloud integration, and multimodal extensibility, directly addressing prior limitations.

Previous multimodal implementations often lacked a unified, tiered architecture supporting both real-time inference and long-term analytics. By leveraging RP2040-based acquisition, on-device TinyML, and AWS-integrated pipelines, the present prototype achieves this integration without the baggage of lab-only or cloud-only approaches. The result is a reviewer-ready, reproducible blueprint for next-generation BCI deployments.

While IoT-enabled biosensor systems are increasingly reported, most lack comprehensive tiered pipelines for simultaneous real-time inference and scalable archival [

93,

94]. Cloud-heavy approaches face bottlenecks and cost inefficiencies, whereas edge-only deployments also make it harder to support longitudinal analytics and reproducible benchmarking against public datasets (such as, TUH-EEG and PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Database (EEGMMIDB), which are commonly used to evaluate generalization beyond single-session prototypes. The RCG system explicitly balances these trade-offs through its hybrid edge–cloud design, validated by Redis for real-time streaming, PostgreSQL for structured analytics, and AWS S3/Glacier for automated archival.

Furthermore, consumer-grade wearables frequently prioritize accessibility over signal fidelity, resulting in noisy recordings that limit clinical translation [

91]. In contrast, the prototype leverages the BioAmp EXG front-end to achieve higher signal quality across multiple biosignal types, paving the way toward clinical-grade performance in a portable form factor.

Collectively, these comparisons highlight the novelty of the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) framework: a modular, cloud-aware system combining portability with scalability, and directly addressing long-standing gaps in latency, reliability, and integration identified in prior work.

5.3. Implications and Future Directions

The validation of a cloud-aware biosensor pipeline using portable hardware has direct impact for translational neuroscience and digital health. By achieving edge inference latencies in the 12–21 ms range (<100 ms worst-case) and end-to-end delays around 1.3–2.1 s for low-power microcontrollers, this work breaks the barrier of lab-bound, server-dependent BCI systems. The Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) framework demonstrates that local edge intelligence and scalable cloud analytics can be tightly integrated for robust, responsive operation in diverse environments [

95].

In healthcare and BCI domains, the capacity to fuse neural intent signals (EEG, EMG, EOG), physiological markers (ECG, GSR/EDA, PPG), and environmental context unlocks richer patient monitoring and adaptive interfaces. This multimodal design increases resilience to artifacts and enables continuous, real-world deployment for applications ranging from neuromuscular rehabilitation to ambulatory cognitive state monitoring, while remaining aligned with non-invasive electrophysiological modalities and their artifact profiles.

Key future directions include:

Large-scale validation and benchmarking using open electrophysiology repositories aligned with non-invasive BCI, including TUH EEG for clinical EEG variability, EEGMMIDB for motor imagery/execution paradigms, and NinaPro for sEMG-driven intent recognition benchmarks, enabling more defensible generalization across subjects and environments[

96].

Advanced cloud-based ML integration for governed training and deployment, including managed deployment primitives (real-time endpoints and edge-fleet model management) to support controlled model iteration and reproducible rollouts alongside the archival pipeline [

97].

By targeting these priorities, the architecture lays a foundation for the next generation of portable, extensible BCIs—moving beyond proof-of-concept toward scalable, clinically relevant digital health solutions.

5.4. Limitations of the Present Study

While the proposed system demonstrated the feasibility of a cloud-aware, multimodal biosensor pipeline, several limitations remain. First, validation was performed primarily on EMG recordings, with only preliminary acquisition of EEG and ECG; large-scale benchmarking across diverse, real-world biosignal datasets is still needed. Second, embedded inference on the RP2040 was restricted to lightweight, window-bounded classifiers suitable for TinyML constraints; more computationally intensive deep architectures were considered only as future cloud-side extensions rather than validated deployment components in the present study. Third, the system architecture currently depends on AWS for cloud analytics and storage, which may limit generalizability in settings where other platforms or on-premises solutions are required. Finally, user evaluation was limited to engineering validation and demonstration use cases; no clinical or population-scale testing has yet been performed. Broader external validation remains pending and will be addressed by benchmarking against open electrophysiology datasets that match the system’s target modalities (EEG/EMG) and task structure (motor imagery/execution), including TUH EEG and EEGMMIDB [

98], alongside EMG intent datasets such as NinaPro [

99].

These limitations highlight the need for future work focused on comprehensive multimodal benchmarking, deployment of advanced ML models at the edge, platform-agnostic cloud integration, and rigorous clinical validation.

6. Conclusions

This work presented a cloud-aware, multimodal biosensor architecture validated through a fully implemented physical prototype. By integrating EEG, EMG, and ECG acquisition with environmental context sensing, the system demonstrated that portable hardware can support distributed pipelines that combine edge-level TinyML inference with scalable cloud storage and analytics. Edge inference latencies were typically 12–21 ms and consistently below 100 ms, while end-to-end acquisition-to-visualization delays averaged approximately 1.3–2.1 s in the tuned telemetry and dashboard path under steady LTE conditions, with occasional longer outliers. Packet loss remained below 5 percent across test sessions. These results confirm that real-time responsiveness can be achieved on low-power microcontrollers.

As shown in

Figure 6, the design was structured within the Real-time Cognitive Grid (RCG) abstraction, comprising edge preprocessing (RCG Cortex), secure uplink (RCG Gateway), structured and archival storage (RCG Vault), and real-time visualization and feedback (RCG Dash). This modular abstraction provides a reproducible blueprint that generalizes beyond the prototype and enables progressive multimodal expansion.

Although the primary validation focused on EMG intent detection with preliminary EEG and ECG support, the architecture is inherently extensible to additional non-invasive biosignals such as EOG (via the BioAmp Pill) and adjunct channels such as GSR/EDA and PPG (via external sensor modules), together with environmental sensors for contextual enrichment. The combination of local preprocessing, tiered cloud integration, and multi-channel feedback establishes a scalable foundation for translational BCI systems.

Future work will prioritize large-scale benchmarking using open biosignal repositories such as TUH EEG (clinical EEG variability), NinaPro (sEMG intent benchmarks), and PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery datasets for standardized motor paradigms, together with integration of advanced ML pipelines for adaptive model updates, and evaluation in clinical or telemedicine-oriented deployments. These steps will be essential to transition the architecture from prototype feasibility to population-scale applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.G.; investigation, S.G. and P.S.; visualization, S.G. and P.S.; methodology, visualization and writing—original draft preparation S.G., P.S. and H.P.B.; resources, P.S. and H.P.B.; data curation, P.S. and H.P.B.; software, S.G., R.B. and A.M.; validation and formal analysis, R.B. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.G., B.G., D.M. and P.P.; supervision, B.G., D.M. and P.P.; project administration, B.G., D.M. and P.P.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy/legal/ethical restrictions but may be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

D.M. acknowledges the support from the Department of Biophysics and Radiation Biology and the National Research, Development and Innovation Office at Semmelweis University, and the Ministry of Innovation. B.G. and P.P. acknowledge the support from the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine and Data Science, the AI Research (DSAIR) Centre of NTU, and the Cognitive Neuro Imaging Centre (CONIC) at NTU. This manuscript reports original research, and all scientific content, data, analyses, figures, and interpretations presented in this study were generated by the authors.

Usage of AI: During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version 5.2) exclusively for language refinement and stylistic improvement in the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Niso, G.; Romero, E.; Moreau, J.T.; Araujo, A.; Krol, L.R. Wireless EEG: A Survey of Systems and Studies. Neuroimage 2023, 269, 119774. [CrossRef]

- Rancea, A.; Anghel, I.; Cioara, T.; Rancea, A.; Anghel, I.; Cioara, T. Edge Computing in Healthcare: Innovations, Opportunities, and Challenges. Future Internet 2024, Vol. 16, 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Gomez-Gil, J. Brain Computer Interfaces, a Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 1211–1279. [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.J.; Wolpaw, J.R. Brain–Computer Interfaces in Neurological Rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol 2008, 7, 1032–1043. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Sejnowski, T.; Makeig, S. Enhanced Detection of Artifacts in EEG Data Using Higher-Order Statistics and Independent Component Analysis. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 1443–1449. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Putz, G.R.; Scherer, R.; Pfurtscheller, G.; Rupp, R. EEG-Based Neuroprosthesis Control: A Step towards Clinical Practice. Neurosci Lett 2005, 382, 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Heikenfeld, J.; Jajack, A.; Rogers, J.; Gutruf, P.; Tian, L.; Pan, T.; Li, R.; Khine, M.; Kim, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Wearable Sensors: Modalities, Challenges, and Prospects. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 217–248. [CrossRef]

- Brunner, C.; Allison, B.Z.; Altstätter, C.; Neuper, C. A Comparison of Three Brain-Computer Interfaces Based on Event-Related Desynchronization, Steady State Visual Evoked Potentials, or a Hybrid Approach Using Both Signals. J Neural Eng 2011, 8. [CrossRef]

- Z. Allison, B.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. A Four-Choice Hybrid P300/SSVEP BCI for Improved Accuracy. Brain-Computer Interfaces 2014, 1, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Allison, B.Z.; Brunner, C.; Altstätter, C.; Wagner, I.C.; Grissmann, S.; Neuper, C. A Hybrid ERD/SSVEP BCI for Continuous Simultaneous Two Dimensional Cursor Control. J Neurosci Methods 2012, 209, 299–307. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Daly, I.; Allison, B.Z.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, X. A New Hybrid BCI Paradigm Based on P300 and SSVEP. J Neurosci Methods 2015, 244, 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Yan, M.; Sakurai, K.; Tanno, K. EOG-SEMG Human Interface for Communication. Comput Intell Neurosci 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Belkhiria, C.; Boudir, A.; Hurter, C.; Peysakhovich, V. EOG-Based Human–Computer Interface: 2000–2020 Review. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 4914. [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, R.; Ros, T.; Stoeckel, L.; Haller, S.; Scharnowski, F.; Lewis-Peacock, J.; Weiskopf, N.; Blefari, M.L.; Rana, M.; Oblak, E.; et al. Closed-Loop Brain Training: The Science of Neurofeedback. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016, 18, 86–100. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Symons, J.; Agapow, P.; Teo, J.T.; Paxton, C.A.; Abdi, J.; Mattie, H.; Davie, C.; Torres, A.Z.; Folarin, A.; et al. Best Practices in the Real-World Data Life Cycle. PLOS Digital Health 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- Beh, W.K.; Wu, Y.H.; Wu, A.Y. Robust PPG-Based Mental Workload Assessment System Using Wearable Devices. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2023, 27, 2323–2333. [CrossRef]

- Sjouwerman, R.; Lonsdorf, T.B. Latency of Skin Conductance Responses across Stimulus Modalities. Psychophysiology 2019, 56. [CrossRef]

- Islam, U.; Alatawi, M.N.; Alqazzaz, A.; Alamro, S.; Shah, B.; Moreira, F. A Hybrid Fog-Edge Computing Architecture for Real-Time Health Monitoring in IoMT Systems with Optimized Latency and Threat Resilience. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tronstad, C.; Staal, O.M.; Saelid, S.; Martinsen, O.G. Model- Based Filtering for Artifact and Noise Suppression with State Estimation for Electrodermal Activity Measurements in Real Time. Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS 2015, 2015-November, 2750–2753. [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, V.; Boumpa, E.; Giannakas, G.; Kakarountas, A. A Review of Machine Learning and TinyML in Healthcare. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 2021, 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Alajlan, N.N.; Ibrahim, D.M. TinyML: Enabling of Inference Deep Learning Models on Ultra-Low-Power IoT Edge Devices for AI Applications. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13, 851. [CrossRef]

- Schizas, N.; Karras, A.; Karras, C.; Sioutas, S. TinyML for Ultra-Low Power AI and Large Scale IoT Deployments: A Systematic Review. Future Internet 2022, Vol. 14, Page 363 2022, 14, 363. [CrossRef]

- Arcas, G.I.; Cioara, T.; Anghel, I. Whale Optimization for Cloud–Edge-Offloading Decision-Making for Smart Grid Services. Biomimetics 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jiman, A.A.; Attar, E.T. Unsupervised Clustering of Pre-Ictal EEG in Children: A Reproducible and Lightweight CPU-Based Workflow. Front Neurol 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Luganga, A. Emofusion: Toward Emotion-Driven Adaptive Computational Design Workflows. IMX 2025 - Proceedings of the 2025 ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences 2025, 473–478. [CrossRef]

- Abdulmalek, S.; Nasir, A.; Jabbar, W.A.; Almuhaya, M.A.M.; Bairagi, A.K.; Khan, M.A.M.; Kee, S.H. IoT-Based Healthcare-Monitoring System towards Improving Quality of Life: A Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wu, F.; Qiu, C.; Redoute, J.M.; Yuce, M.R. A Rigid-Flex Wearable Health Monitoring Sensor Patch for IoT-Connected Healthcare Applications. IEEE Internet Things J 2020, 7, 6932–6945. [CrossRef]

- Mamdiwar, S.D.; Akshith, R.; Shakruwala, Z.; Chadha, U.; Srinivasan, K.; Chang, C.Y. Recent Advances on Iot-Assisted Wearable Sensor Systems for Healthcare Monitoring. Biosensors (Basel) 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, Q. High Rate BCI with Portable Devices Based on EEG. Smart Health 2018, 9–10, 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Tsai, T.T.; Luo, C.H. Portable and Programmable Clinical EOG Diagnostic System. J Med Eng Technol 2000, 24, 154–162. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.A.; Vanleer, A.C.; Calibo, T.K.; Firebaugh, S.L. Single-Trial Cognitive Stress Classification Using Portable Wireless Electroencephalography. Sensors (Switzerland) 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.O.; Onuajah, S.I.; Adeniran, A.A.; Ogunmola, M.A. Implementing Cloud-Centric IoT Transformations: Merits and Demerits. Systemic Analytics 2024, 2, 174–187. [CrossRef]

- Spillner, J.; Müller, J.; Schill, A. Creating Optimal Cloud Storage Systems. Future Generation Computer Systems 2013, 29, 1062–1072. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.; Mzurikwao, D.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.; Mishra, S.; Herbert, R.; Duarte, A.; Ang, C.S.; Yeo, W.-H. Fully Portable and Wireless Universal Brain–Machine Interfaces Enabled by Flexible Scalp Electronics and Deep Learning Algorithm. Nat Mach Intell 2019, 1, 412–422. [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.S.; Khan, M.J. Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface Techniques for Improved Classification Accuracy and Increased Number of Commands: A Review. Front Neurorobot 2017, 11, 275683. [CrossRef]

- Bright, D.; Nair, A.; Salvekar, D.; Bhisikar, S. EEG-Based Brain Controlled Prosthetic Arm. Conference on Advances in Signal Processing, CASP 2016 2016, 479–483. [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, L.R.; Serruya, M.D.; Friehs, G.M.; Mukand, J.A.; Saleh, M.; Caplan, A.H.; Branner, A.; Chen, D.; Penn, R.D.; Donoghue, J.P. Neuronal Ensemble Control of Prosthetic Devices by a Human with Tetraplegia. Nature 2006, 442, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Asokan, A.; Vigneshwar, M. Design and Control of an EMG-Based Low-Cost Exoskeleton for Stroke Rehabilitation. 2019 5th Indian Control Conference, ICC 2019 - Proceedings 2019, 478–483. [CrossRef]

- Seok, D.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Cho, J.; Kim, C. Motion Artifact Removal Techniques for Wearable EEG and PPG Sensor Systems. Frontiers in Electronics 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Mussi, M.G.; Adams, K.D. EEG Hybrid Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Scoping Review Applying an Existing Hybrid-BCI Taxonomy and Considerations for Pediatric Applications. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16, 1007136. [CrossRef]

- Kinney-Lang, E.; Kelly, D.; Floreani, E.D.; Jadavji, Z.; Rowley, D.; Zewdie, E.T.; Anaraki, J.R.; Bahari, H.; Beckers, K.; Castelane, K.; et al. Advancing Brain-Computer Interface Applications for Severely Disabled Children Through a Multidisciplinary National Network: Summary of the Inaugural Pediatric BCI Canada Meeting. Front Hum Neurosci 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Skarmeta, A.F. TinyML-Enabled Frugal Smart Objects: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 2020, 20, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Saoud, L.S.; Hussain, I. TempoNet: Empowering Long-Term Knee Joint Angle Prediction with Dynamic Temporal Attention in Exoskeleton Control. IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zanghieri, M.; Benatti, S.; Burrello, A.; Kartsch, V.; Conti, F.; Benini, L. Robust Real-Time Embedded EMG Recognition Framework Using Temporal Convolutional Networks on a Multicore IoT Processor. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2020, 14, 244–256. [CrossRef]

- Elfouly, T.; Alouani, A.; Elfouly, T.; Alouani, A. A Comprehensive Survey on Wearable Computing for Mental and Physical Health Monitoring. Electronics 2025, Vol. 14, 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, D. Transfer Learning in Motor Imagery Brain Computer Interface: A Review. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ Sci 2024, 29, 37–59. [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; von Weltin, E.; Lopez, S.; McHugh, J.R.; Veloso, L.; Golmohammadi, M.; Obeid, I.; Picone, J. The Temple University Hospital Seizure Detection Corpus. Front Neuroinform 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Donohue, M.C.; Gamst, A.C.; Harvey, D.J.; Jack, C.R.; Jagust, W.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Toga, A.W.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Neurology 2010, 74, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Kumar, J.; Sheoran, P. Integration of Cloud Computing in BCI: A Review. Biomed Signal Process Control 2024, 87, 105548. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Rahaman, A.; Islam, M.R. Development of Smart Healthcare Monitoring System in IoT Environment. SN Comput Sci 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Turnip, A.; Pardede, J. Artefacts Removal of EEG Signals with Wavelet Denoising. MATEC Web of Conferences 2017, 135. [CrossRef]

- Butkeviciute, E.; Bikulciene, L.; Sidekerskiene, T.; Blazauskas, T.; Maskeliunas, R.; Damasevicius, R.; Wei, W. Removal of Movement Artefact for Mobile EEG Analysis in Sports Exercises. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 7206–7217. [CrossRef]

- D’Rozario, A.L.; Dungan, G.C.; Banks, S.; Liu, P.Y.; Wong, K.K.H.; Killick, R.; Grunstein, R.R.; Kim, J.W. An Automated Algorithm to Identify and Reject Artefacts for Quantitative EEG Analysis during Sleep in Patients with Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Sleep and Breathing 2015, 19, 607–615. [CrossRef]

- Atzori, M.; Gijsberts, A.; Kuzborskij, I.; Elsig, S.; Mittaz Hager, A.G.; Deriaz, O.; Castellini, C.; Müller, H.; Caputo, B. Characterization of a Benchmark Database for Myoelectric Movement Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2015, 23, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Wei, C.; Mantini, D.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q. EEGdenoiseNet: A Benchmark Dataset for Deep Learning Solutions of EEG Denoising. J Neural Eng 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Canali, S.; Schiaffonati, V.; Aliverti, A. Challenges and Recommendations for Wearable Devices in Digital Health: Data Quality, Interoperability, Health Equity, Fairness. PLOS Digital Health 2022, 1, e0000104. [CrossRef]

- Canali, S. Towards a Contextual Approach to Data Quality. Data (Basel) 2020, 5, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Staunton, C.; Barragán, C.A.; Canali, S.; Ho, C.; Leonelli, S.; Mayernik, M.; Prainsack, B.; Wonkham, A. Open Science, Data Sharing and Solidarity: Who Benefits? Hist Philos Life Sci 2021, 43. [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; De Luca, M.; Di Marino, L.; Duran, D.; Gargiulo, L.; Lanteri, P.; Moccaldi, N.; Nalin, M.; Picciafuoco, M.; Robbio, R.; et al. A Systematic Review of Techniques for Artifact Detection and Artifact Category Identification in Electroencephalography from Wearable Devices. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Apicella, A.; Arpaia, P.; Isgro, F.; Mastrati, G.; Moccaldi, N. A Survey on EEG-Based Solutions for Emotion Recognition With a Low Number of Channels. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 117411–117428. [CrossRef]

- Yogeshappa, V.G. Designing Cloud-Native Data Platforms for Scalable Healthcare Analytics. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2025, 6, 3784–3791. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Lu, B.L. A Multimodal Approach to Estimating Vigilance Using EEG and Forehead EOG. J Neural Eng 2017, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bissoli, A.L.C.; Coelho, Y.L.; Bastos-Filho, T.F. A System for Multimodal Assistive Domotics and Augmentative and Alternative Communication. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 2016, 29-June-2016. [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Su, W.; Sankarasubramaniam, Y.; Cayirci, E. Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. Computer Networks 2002, 38, 393–422. [CrossRef]

- Rosele, N.; Mohd Zaini, K.; Ahmad Mustaffa, N.; Abrar, A.; Fadilah, S.I.; Madi, M. Digital Transformation in Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Analysis of Mobile Data Offloading Techniques, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Attar, R.W.; Arya, V.; Alhomoud, A.; Chui, K.T. LSTMBased Neural NetworkModel for Anomaly Event Detection in Care-Independent Smart Homes. CMES - Computer Modeling in Engineering and Sciences 2024, 140, 2689–2706. [CrossRef]

- Novák, M.; Biňas, M.; Jakab, F. Unobtrusive Anomaly Detection in Presence of Elderly in a Smart-Home Environment. Proceedings of 9th International Conference, ELEKTRO 2012 2012, 341–344. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Sood, S.K.; Kalra, S. Cloud-Centric IoT Based Student Healthcare Monitoring Framework. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 2018, 9, 1293–1309. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Sood, S.K. Cloud-Centric IoT Based Disease Diagnosis Healthcare Framework. J Parallel Distrib Comput 2018, 116, 27–38. [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Duke, J.; Jain, A.; Reddi, V.J.; Jeffries, N.; Li, J.; Kreeger, N.; Nappier, I.; Natraj, M.; Regev, S.; et al. TensorFlow Lite Micro: Embedded Machine Learning for TinyML Systems. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2021, 3, 800–811.

- Signoretti, G.; Silva, M.; Andrade, P.; Silva, I.; Sisinni, E.; Ferrari, P. An Evolving Tinyml Compression Algorithm for Iot Environments Based on Data Eccentricity. Sensors 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- TinyML: Enabling of Inference Deep Learning Models on Ultra-Low-Power IoT Edge Devices for AI Applications - PMC Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9227753 (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Schizas, N.; Karras, A.; Karras, C.; Sioutas, S. TinyML for Ultra-Low Power AI and Large Scale IoT Deployments: A Systematic Review. Future Internet 2022, 14, 1–45.

- Phinyomark, A.; Khushaba, R.N.; Scheme, E.; Phinyomark, A.; Khushaba, R.N.; Scheme, E. Feature Extraction and Selection for Myoelectric Control Based on Wearable EMG Sensors. Sensors 2018, Vol. 18, 2018, 18. [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, S. Real-Time Vital Sign Monitoring and Health Anomaly Detection on Edge Devices Using Lightweight Machine Learning Models. 2025, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Borton, D.; Micera, S.; Del R. Millán, J.; Courtine, G. Personalized Neuroprosthetics. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5. [CrossRef]

- Raspopovic, S.; Capogrosso, M.; Petrini, F.M.; Bonizzato, M.; Rigosa, J.; Pino, G. Di; Carpaneto, J.; Controzzi, M.; Boretius, T.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Bioengineering: Restoring Natural Sensory Feedback in Real-Time Bidirectional Hand Prostheses. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6. [CrossRef]

- Shalal, N.S.; Aboud, W.S. Robotic Exoskeleton: A Compact, Portable, and Constructing Using 3D Printer Technique for Wrist-Forearm Rehabilitation. Al-Nahrain Journal for Engineering Sciences 2020, 23, 238–248. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, Q. High Rate BCI with Portable Devices Based on EEG. Smart Health 2018, 9–10, 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, K.; Wu, Y. A Multi-Modality Attention Network for Driver Fatigue Detection Based on Frontal EEG, EDA and PPG Signals. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2025, 29, 4009–4022. [CrossRef]

- Janapati, R.; Dalal, V.; Sengupta, R. Advances in Modern EEG-BCI Signal Processing: A Review. Mater Today Proc 2023, 80, 2563–2566. [CrossRef]

- Ingolfsson, T.M.; Hersche, M.; Wang, X.; Kobayashi, N.; Cavigelli, L.; Benini, L. EEG-TCNet: An Accurate Temporal Convolutional Network for Embedded Motor-Imagery Brain-Machine Interfaces. Conf Proc IEEE Int Conf Syst Man Cybern 2020, 2020-October, 2958–2965. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An Open Source Toolbox for Analysis of Single-Trial EEG Dynamics Including Independent Component Analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Xie, S.; Xie, X.; Meng, Y.; Xu, Z. Quadcopter Flight Control Using a Non-Invasive Multi-Modal Brain Computer Interface. Front Neurorobot 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, T.S.; Liang, Z. Development of Non-Invasive Continuous Glucose Prediction Models Using Multi-Modal Wearable Sensors in Free-Living Conditions. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, M.Y. An EEG/EMG/EOG-Based Multimodal Human-Machine Interface to Real-Time Control of a Soft Robot Hand. Front Neurorobot 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.; Sejdic, E.; Akcakaya, M. Hybrid EEG–FTCD Brain–Computer Interfaces. Cognitive Science and Technology 2020, 295–314. [CrossRef]

- Punsawad, Y.; Wongsawat, Y.; Parnichkun, M. Hybrid EEG-EOG Brain-Computer Interface System for Practical Machine Control. 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBC’10 2010, 1360–1363. [CrossRef]

- Shumba, A.T.; Montanaro, T.; Sergi, I.; Fachechi, L.; De Vittorio, M.; Patrono, L. Leveraging IoT-Aware Technologies and AI Techniques for Real-Time Critical Healthcare Applications. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.; King, W.; Mackellar, G.; Randeniya, R.; McCormick, A.; Badcock, N.A. Crowdsourced EEG Experiments: A Proof of Concept for Remote EEG Acquisition Using EmotivPRO Builder and EmotivLABS. Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.; McArthur, G.M.; Badcock, N.A. 10 Years of EPOC: A Scoping Review of Emotiv’s Portable EEG Device. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Stock, V.N.; Balbinot, A. Movement Imagery Classification in EMOTIV Cap Based System by Naïve Bayes. Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS 2016, 2016-October, 4435–4438. [CrossRef]

- Robert, H.; Augereau, O.; Kise, K. Real-Time Wordometer Demonstration Using Commercial EOG Glasses. UbiComp/ISWC 2017 - Adjunct Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers 2017, 277–280. [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.P.; He, Y.; Brown, S.; Nakagame, S.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Gait Adaptation to Visual Kinematic Perturbations Using a Real-Time Closed-Loop Brain-Computer Interface to a Virtual Reality Avatar. J Neural Eng 2016, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.J. Realtime Detection of Brain Events in EEG. Proceedings of the IEEE 1977, 65, 633–641. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Jaimes, M.L.; Martinez-Cruz, A.; Ramírez-Gutiérrez, K.A.; Feregrino-Uribe, C. Artificial Intelligence for IoMT Security: A Review of Intrusion Detection Systems, Attacks, Datasets and Cloud–Fog–Edge Architectures. Internet of Things (Netherlands) 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Roy, Y.; Banville, H.; Albuquerque, I.; Gramfort, A.; Falk, T.H.; Faubert, J. Deep Learning-Based Electroencephalography Analysis: A Systematic Review. J Neural Eng 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset v1.0.0 Available online: https://physionet.org/content/eegmmidb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Ninapro Available online: https://ninapro.hevs.ch/ (accessed on 31 December 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).