Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Generalities

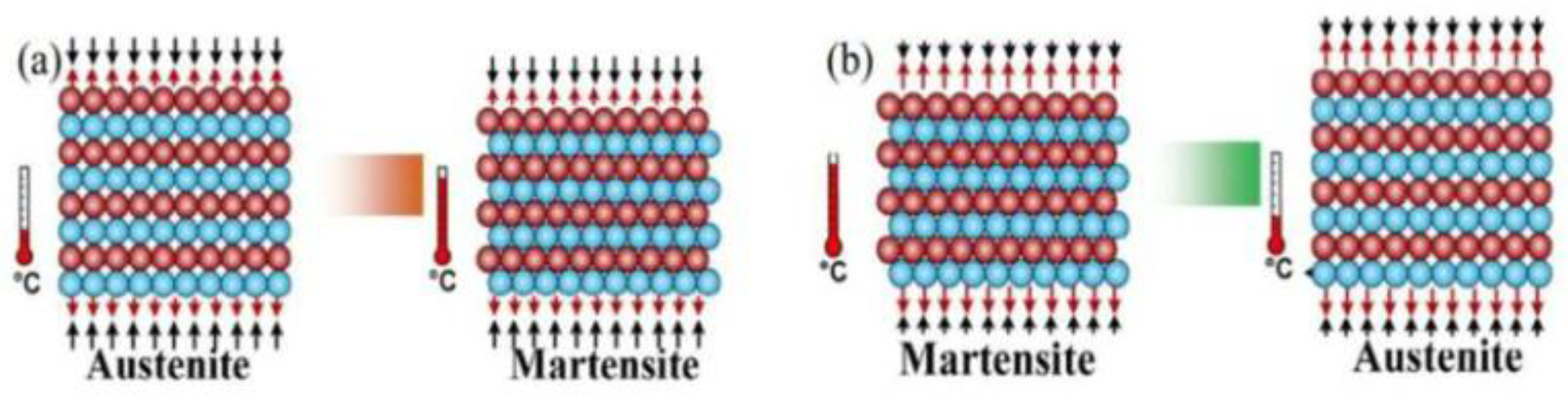

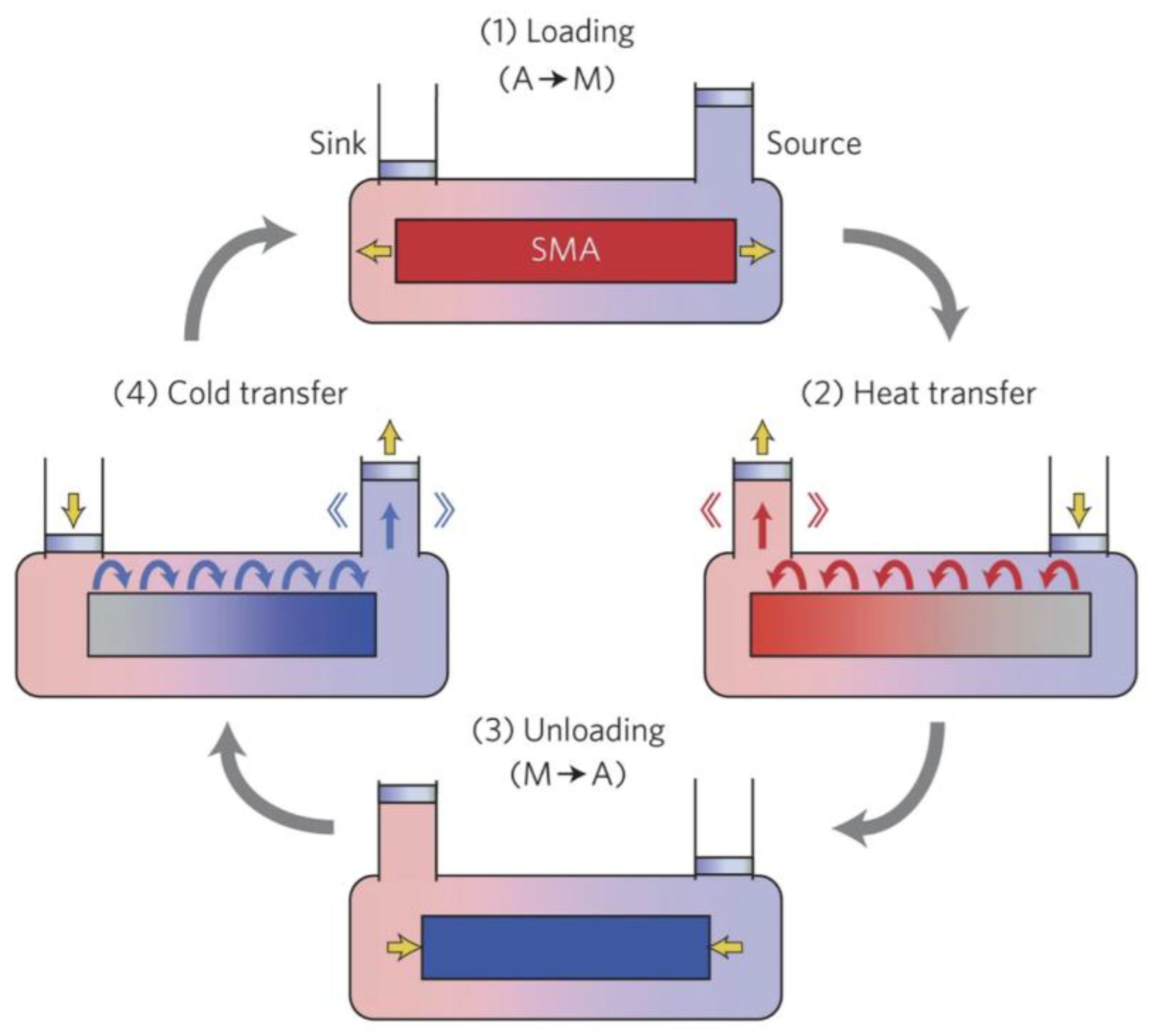

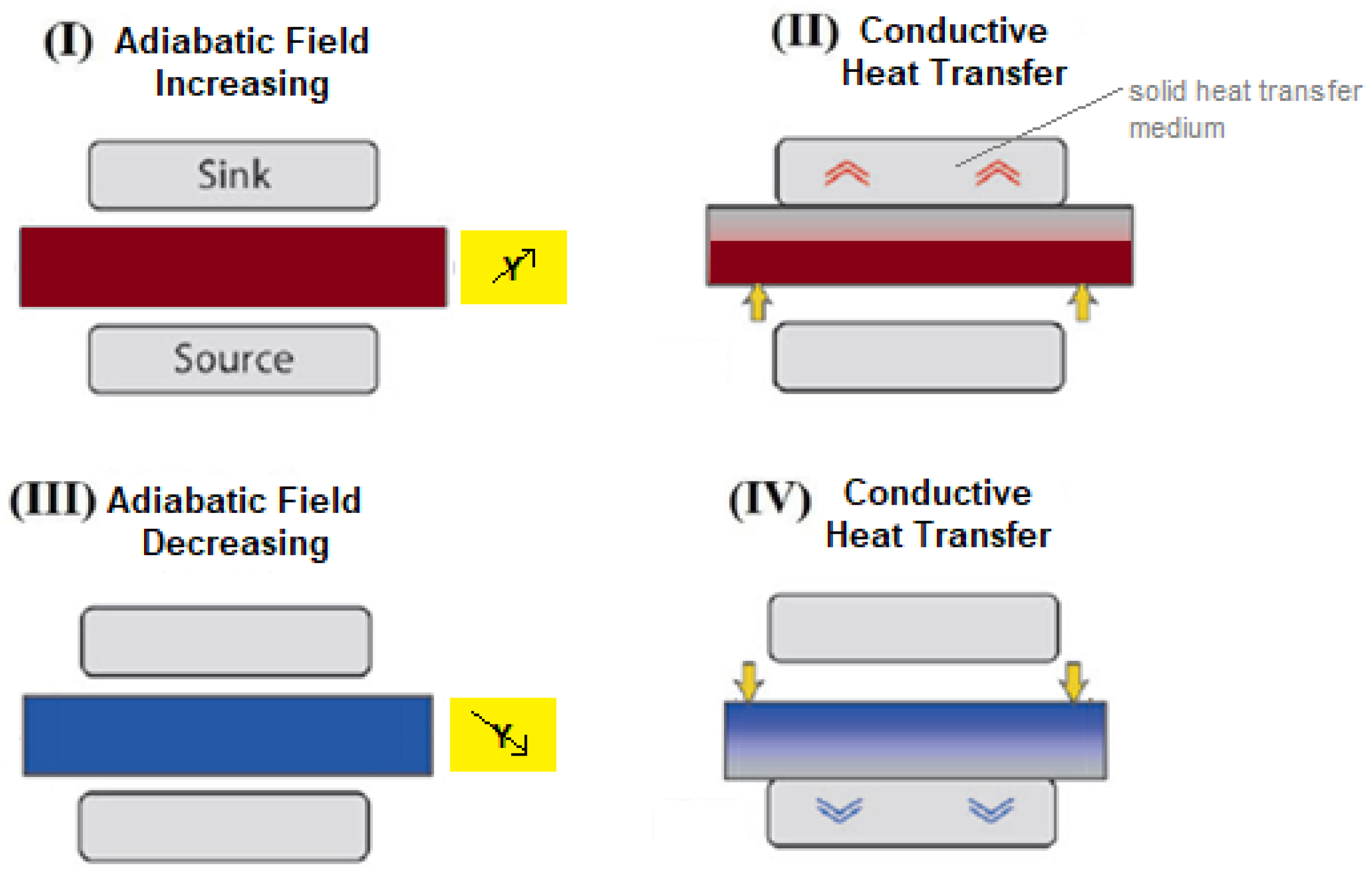

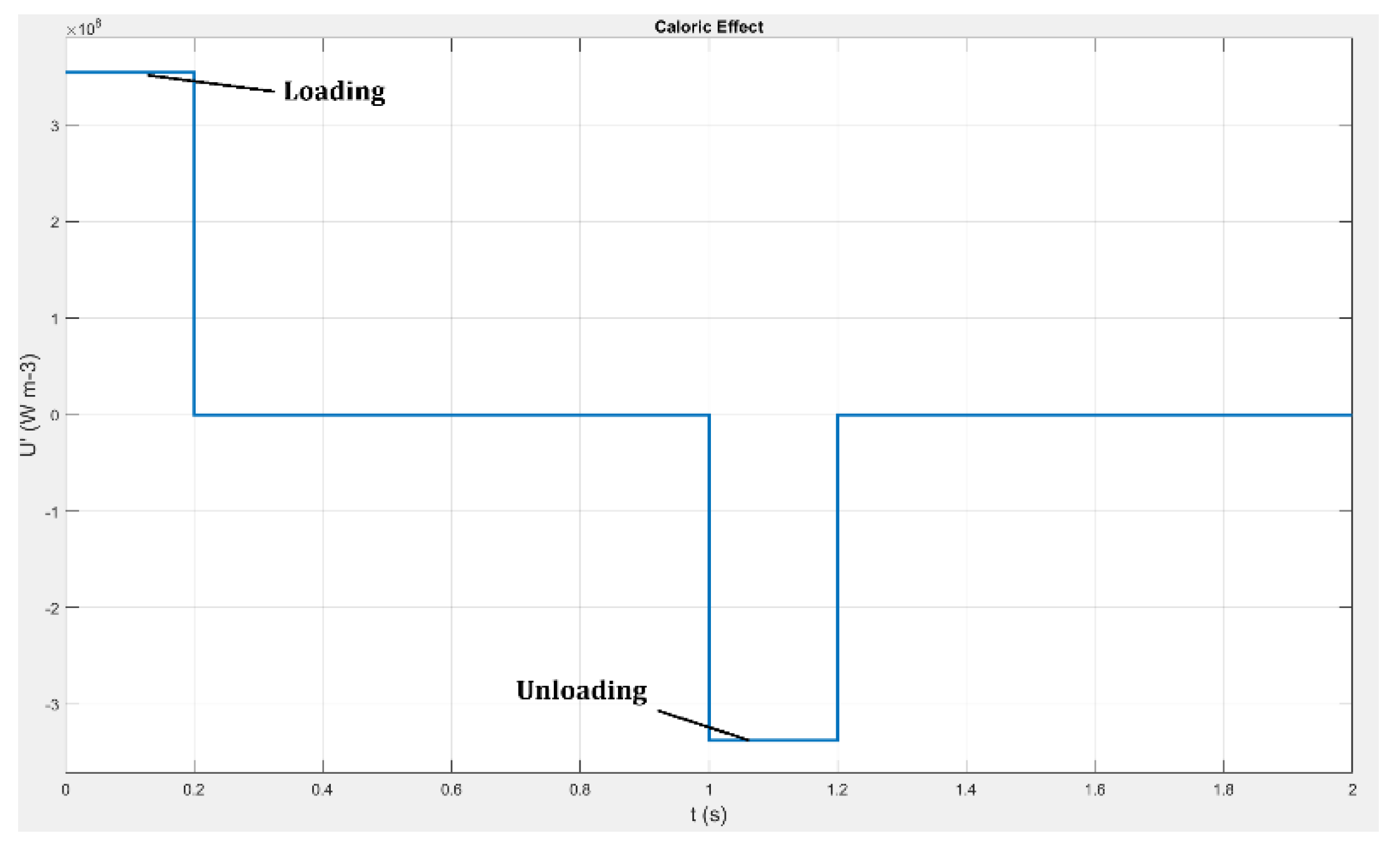

2. Elastocaloric Effect and Cycles

- Adiabatic application of the stress, i.e. loading;

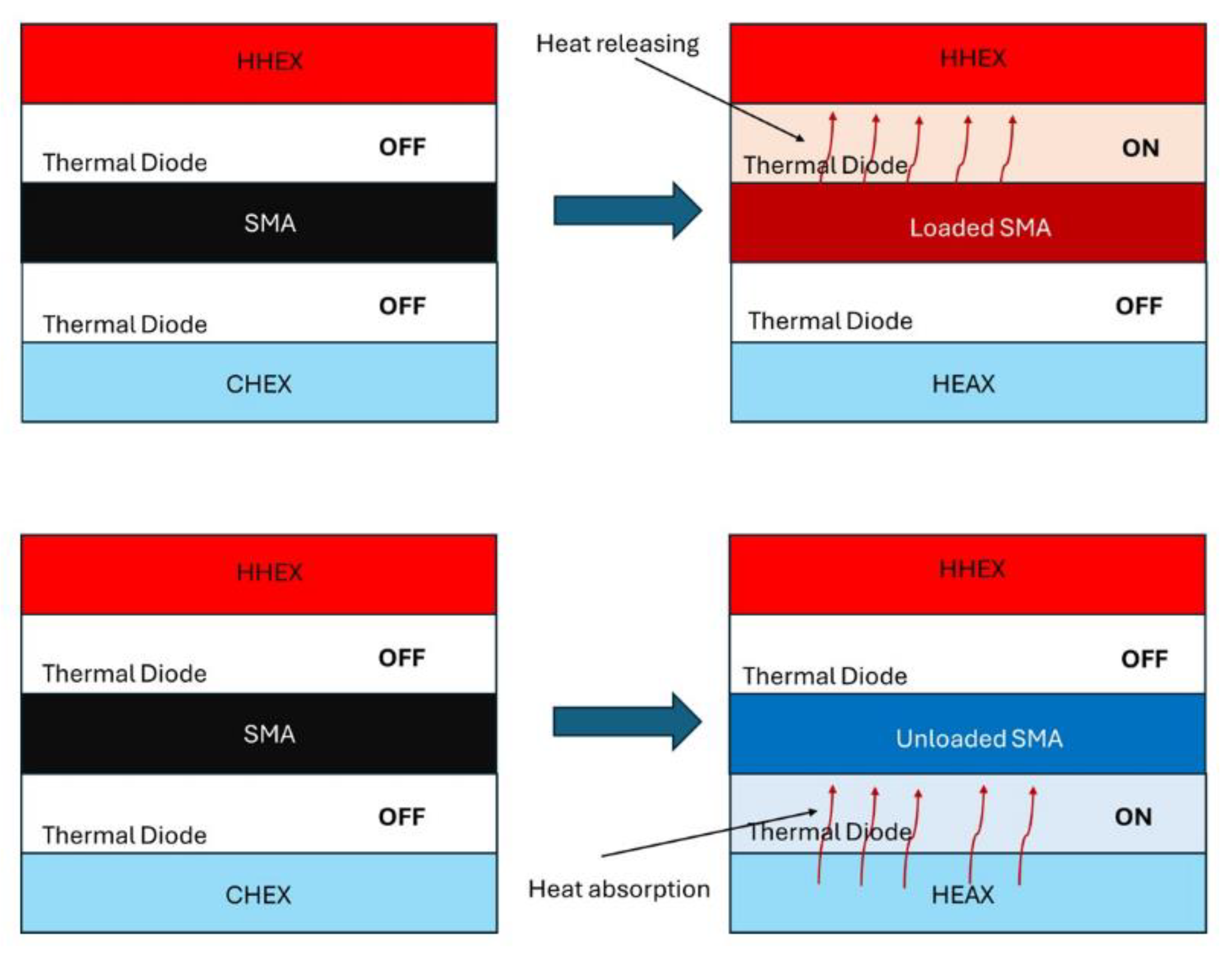

- Heat release to a Hot Heat EXchanger (HHEX);

- Adiabatic remotion of the stress, i.e. unloading;

- Heat absorption from a Cold Heat EXchanger (CHEX).

3. The system Principles and the Numerical Model

3.1. The System Principles

3.2. The Numerical Model And The Materials

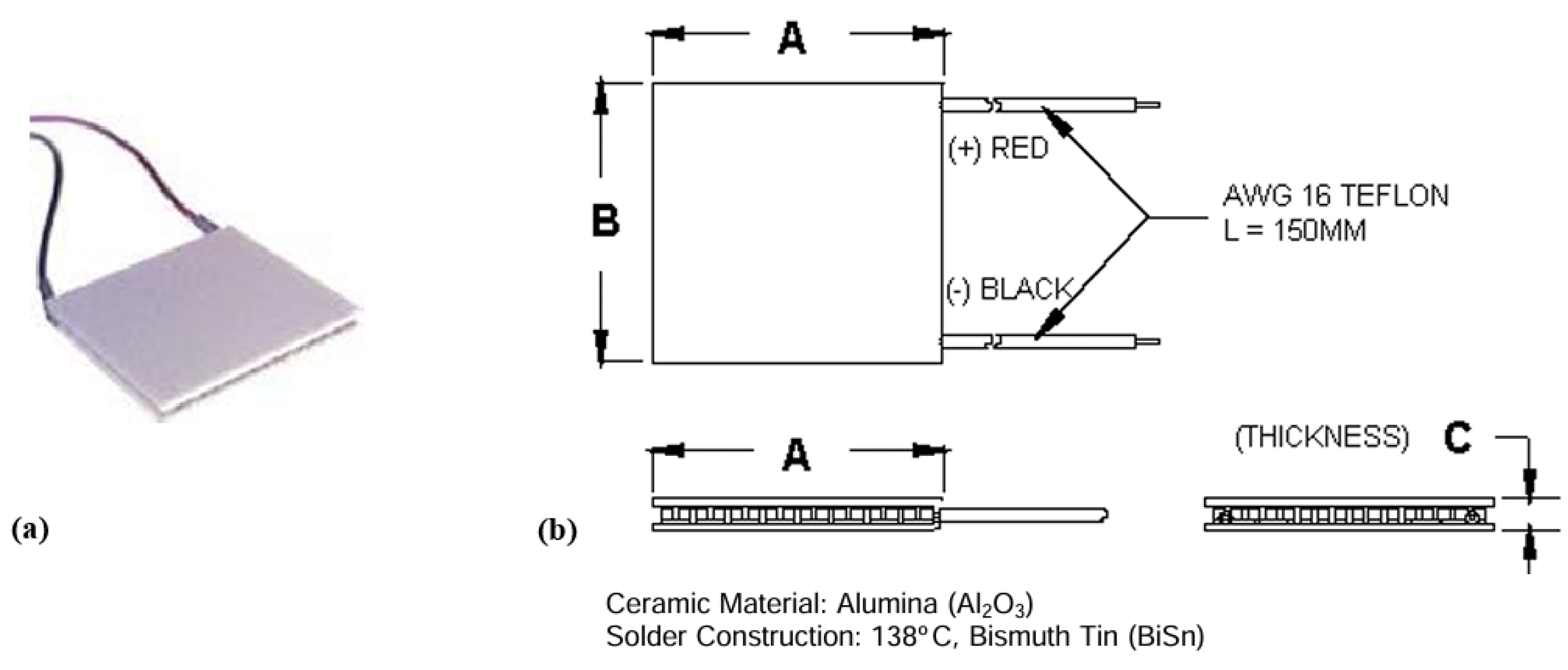

3.3. The Peltier Elements

3.4. Elastocaloric Materials

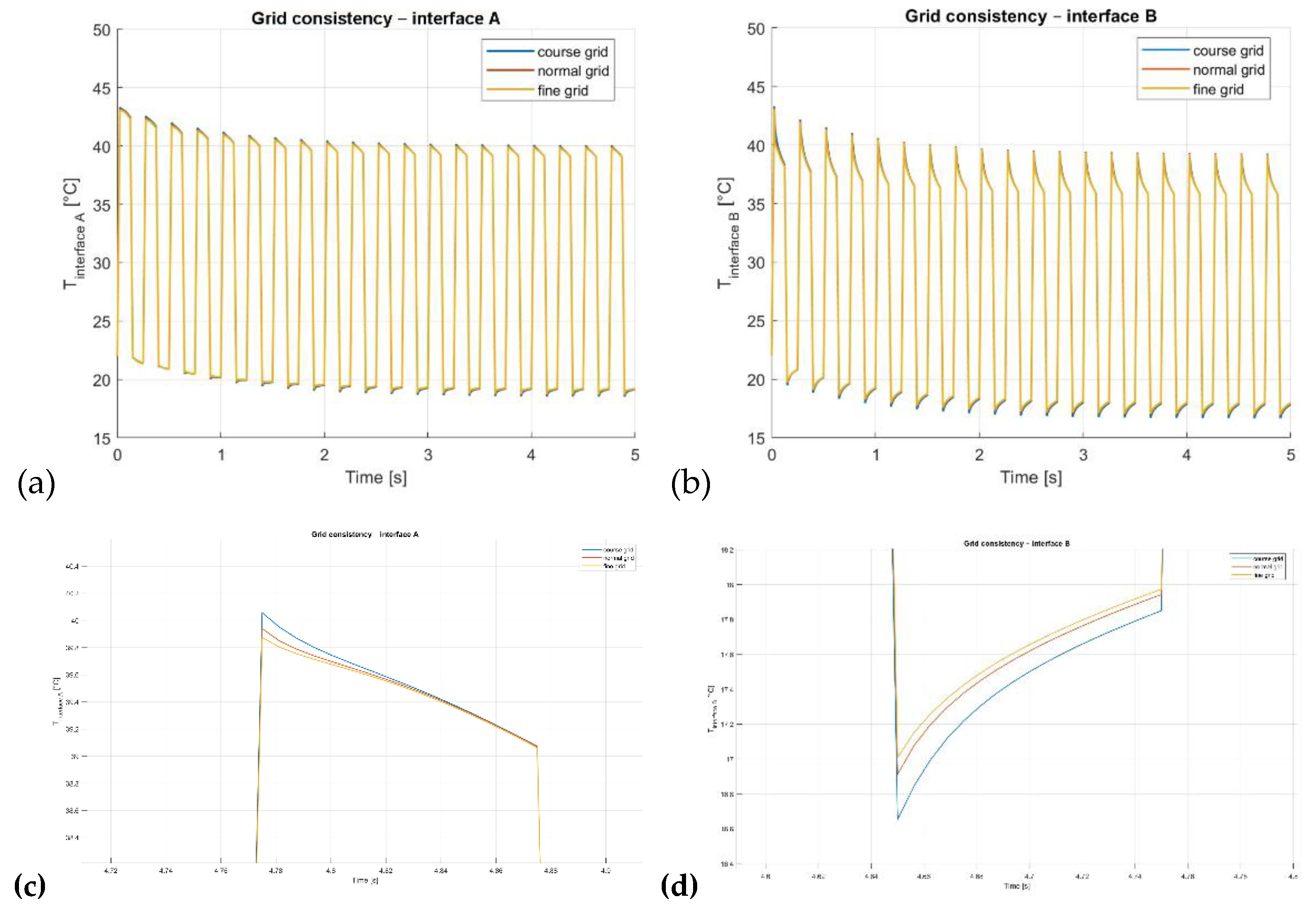

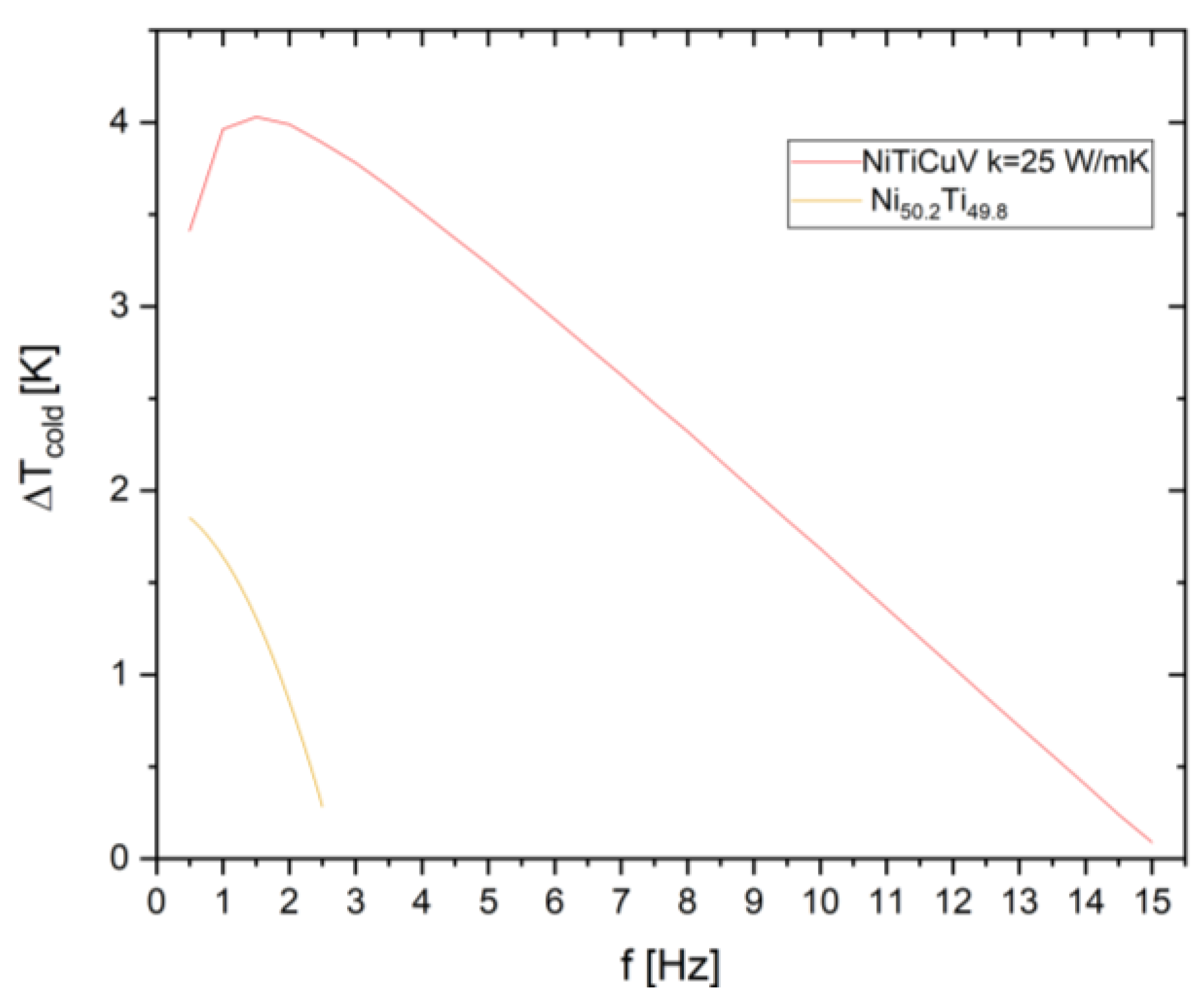

3.5. Convergence of the Solving Method and the Discretization Grid

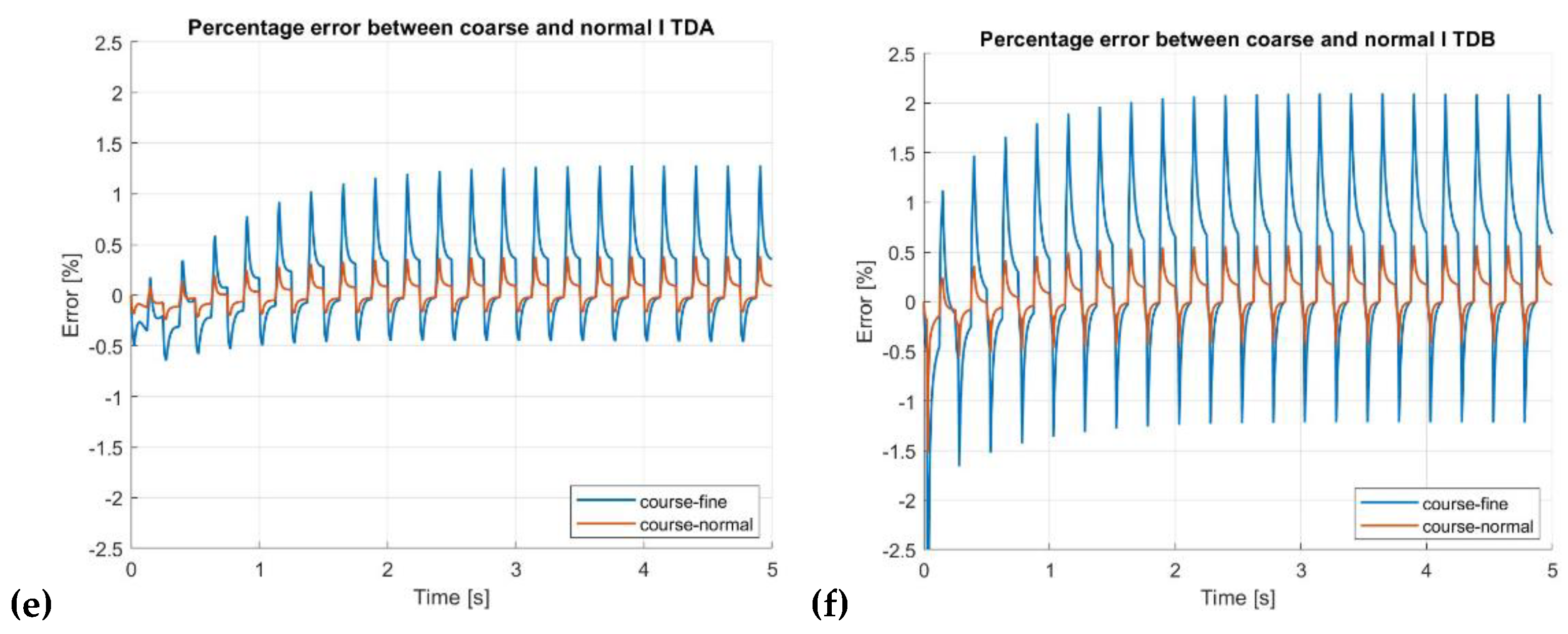

3.6. Validation of the Numerical Model with Literature Data

4. Results

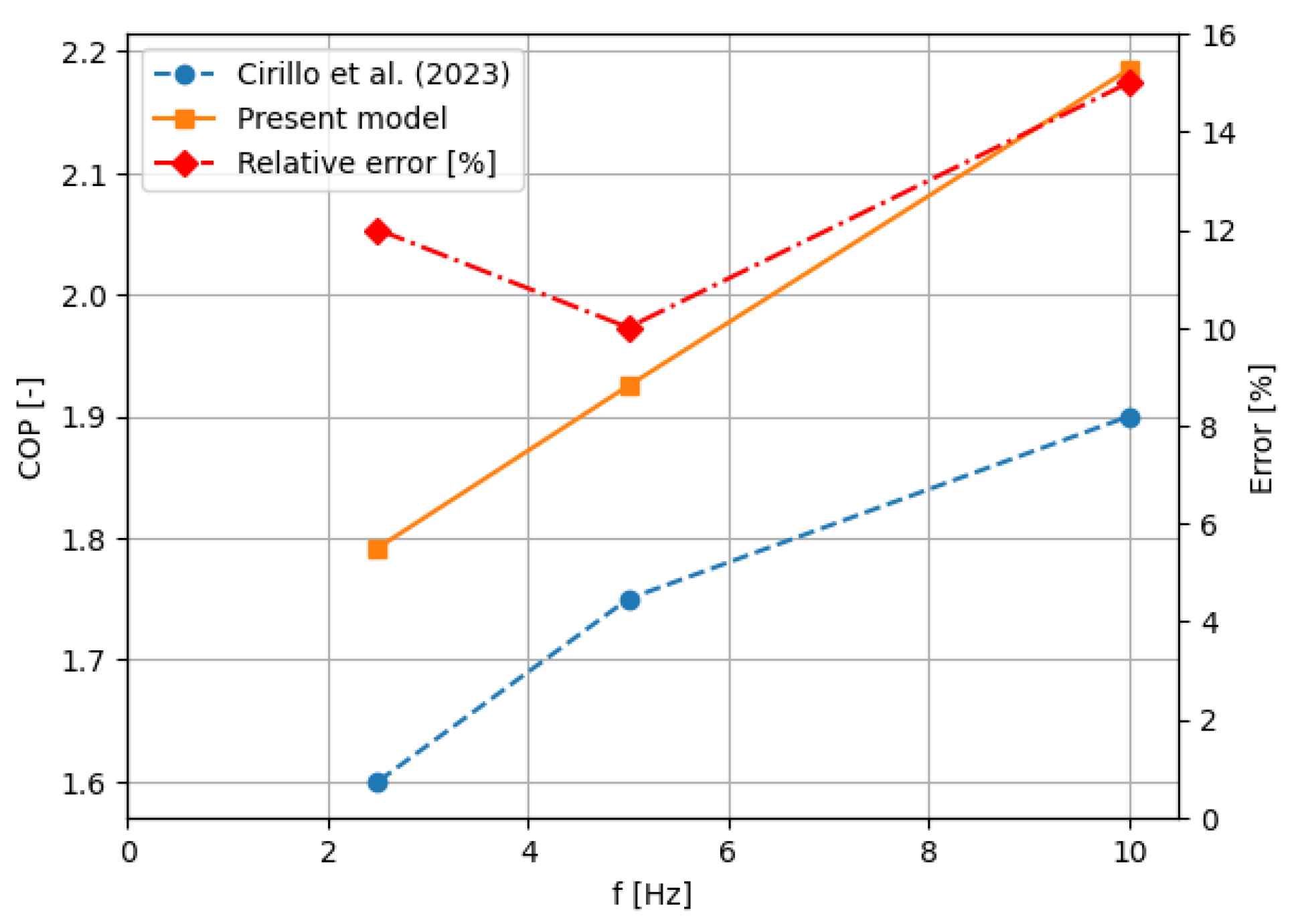

- i)

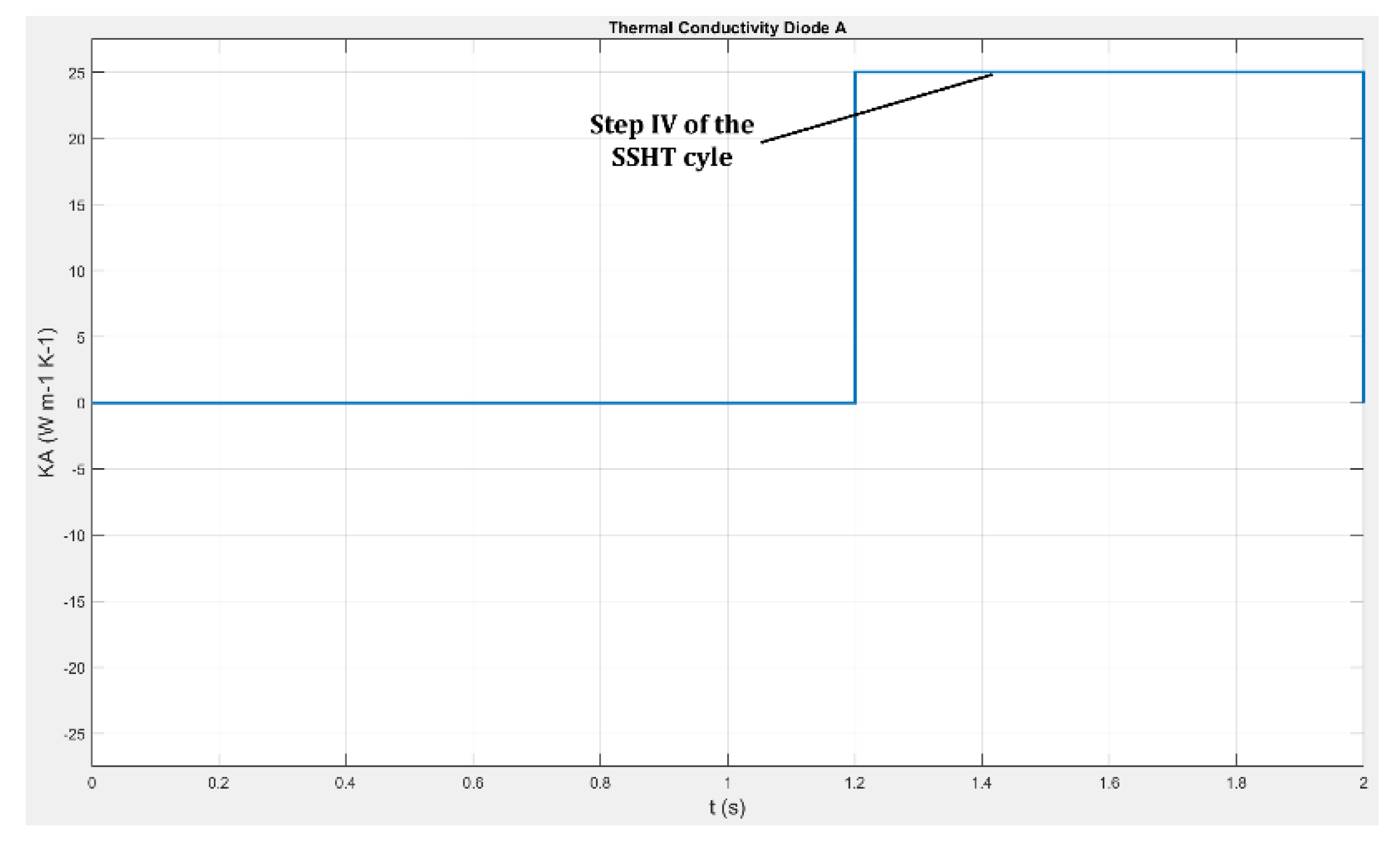

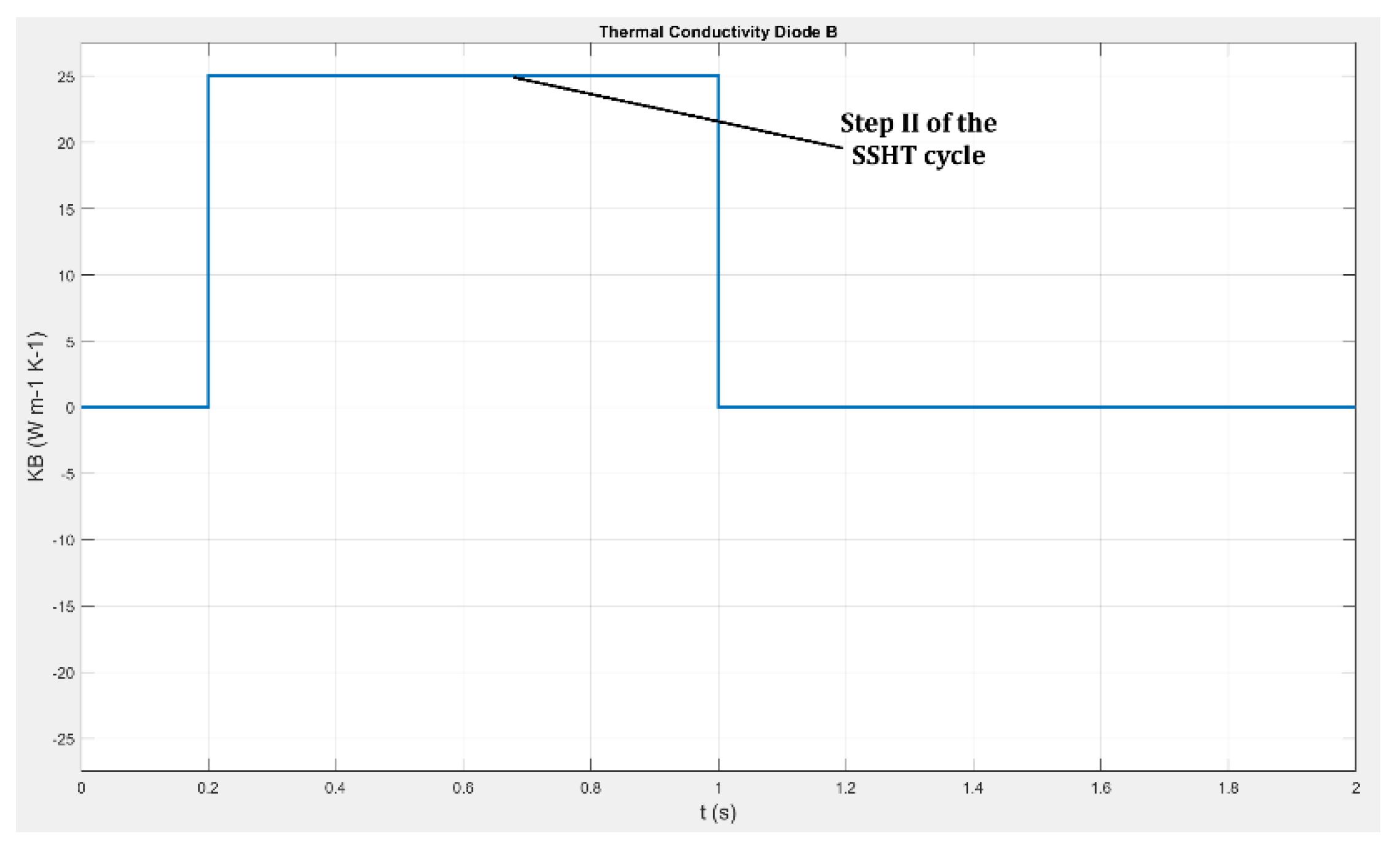

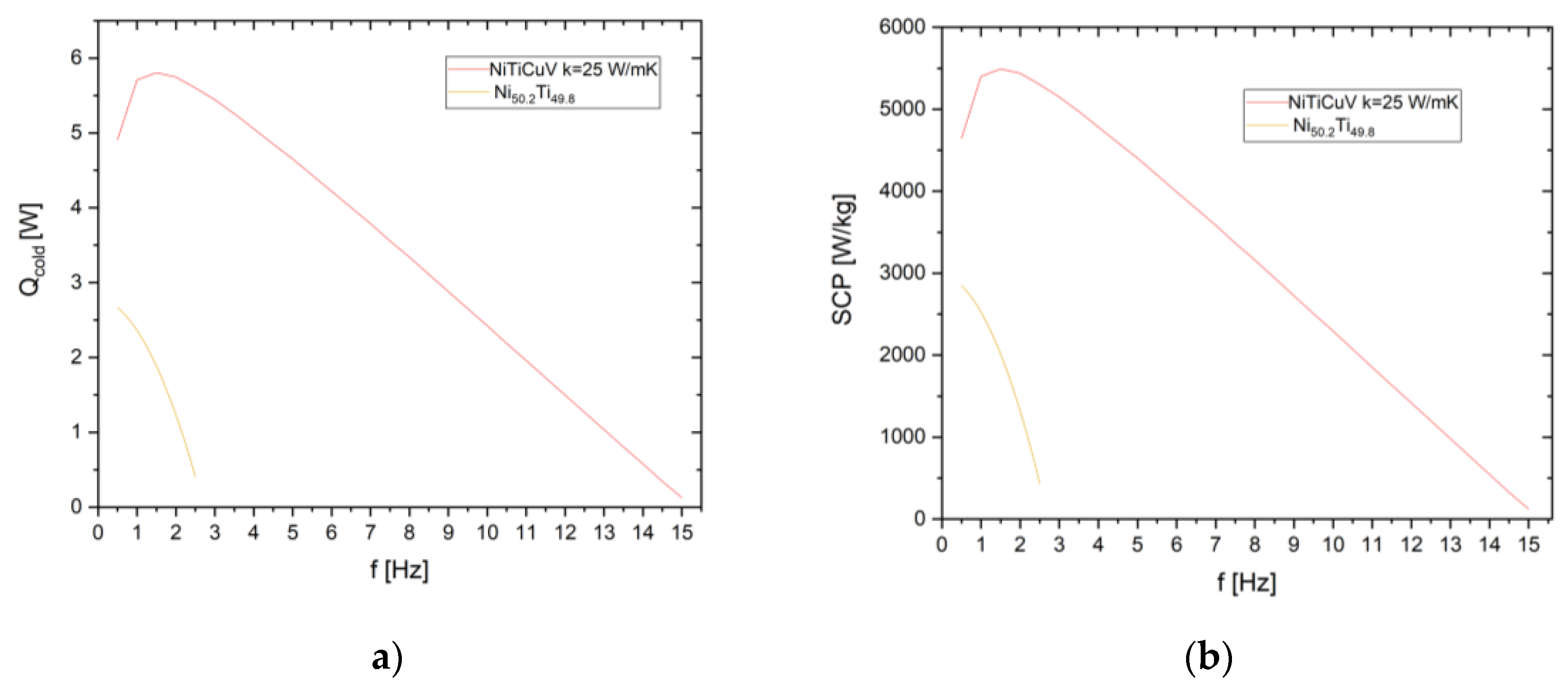

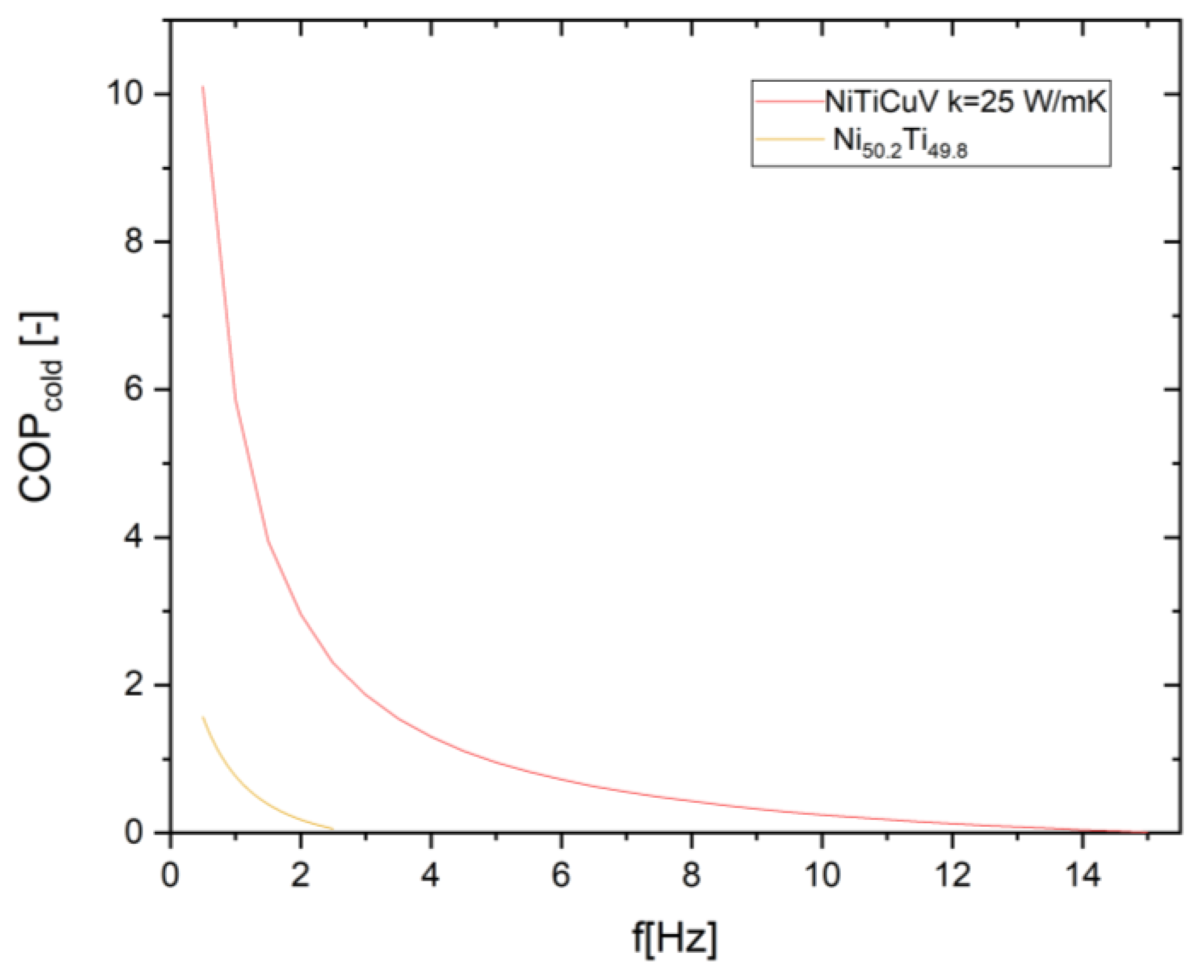

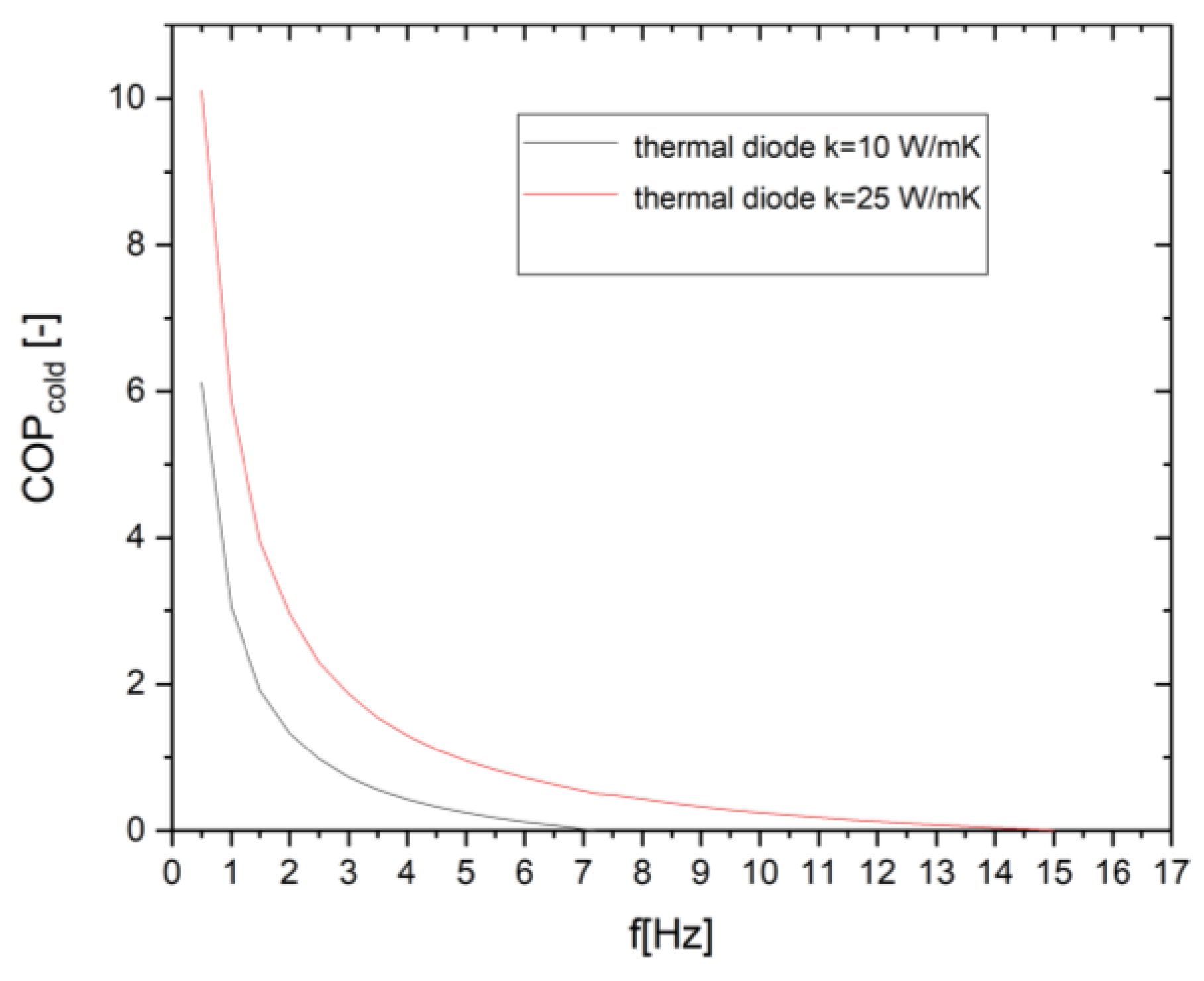

- The first campaign of simulation has focused on analyzing the energy performances provided by the SSHT heat pump in cooling mode with ideal thermal diodes, as a function of the cycle frequency for both the elastocaloric materials under test. In this campaign ITDs with 25 W m-1K-1 are implemented.

- ii)

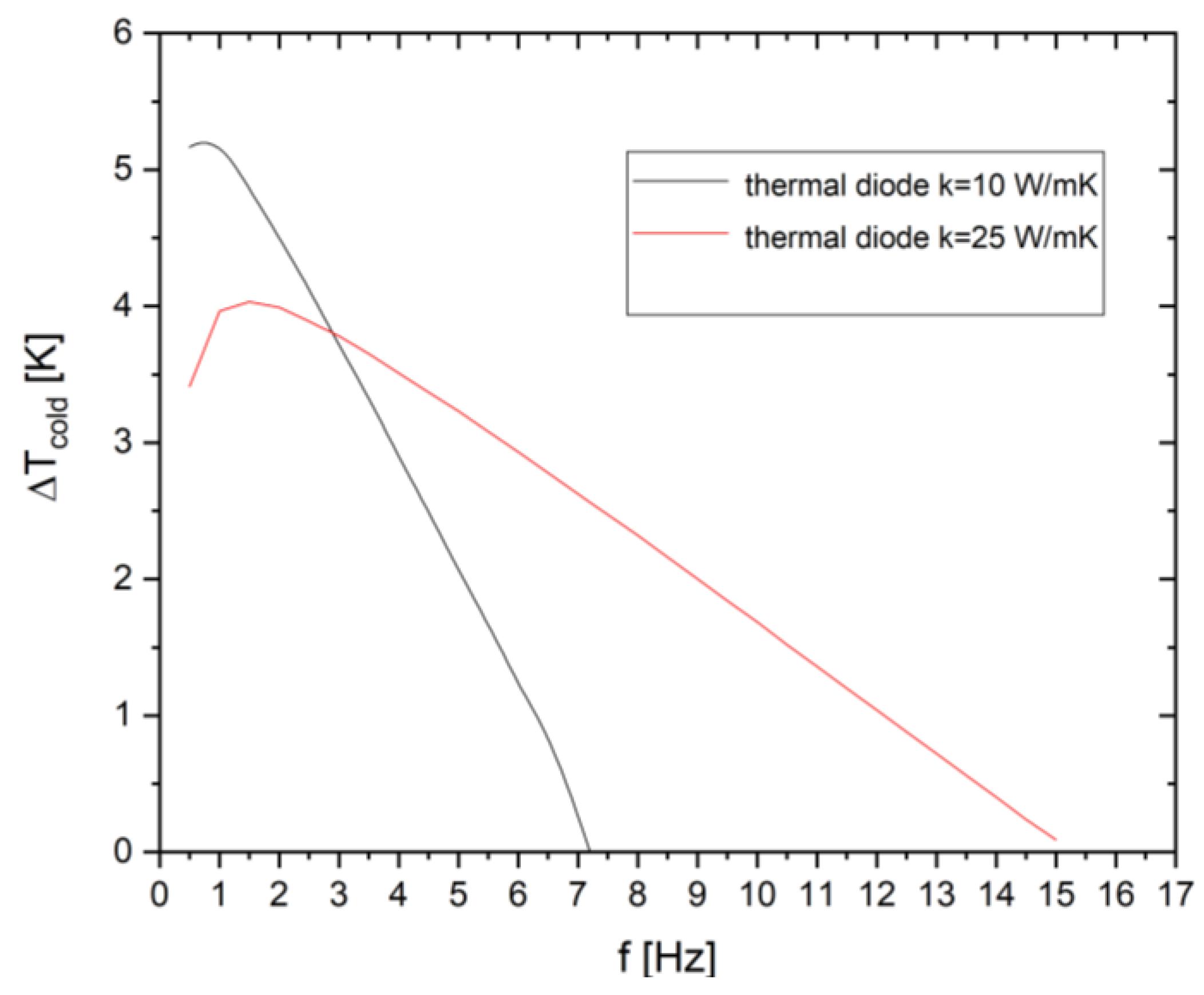

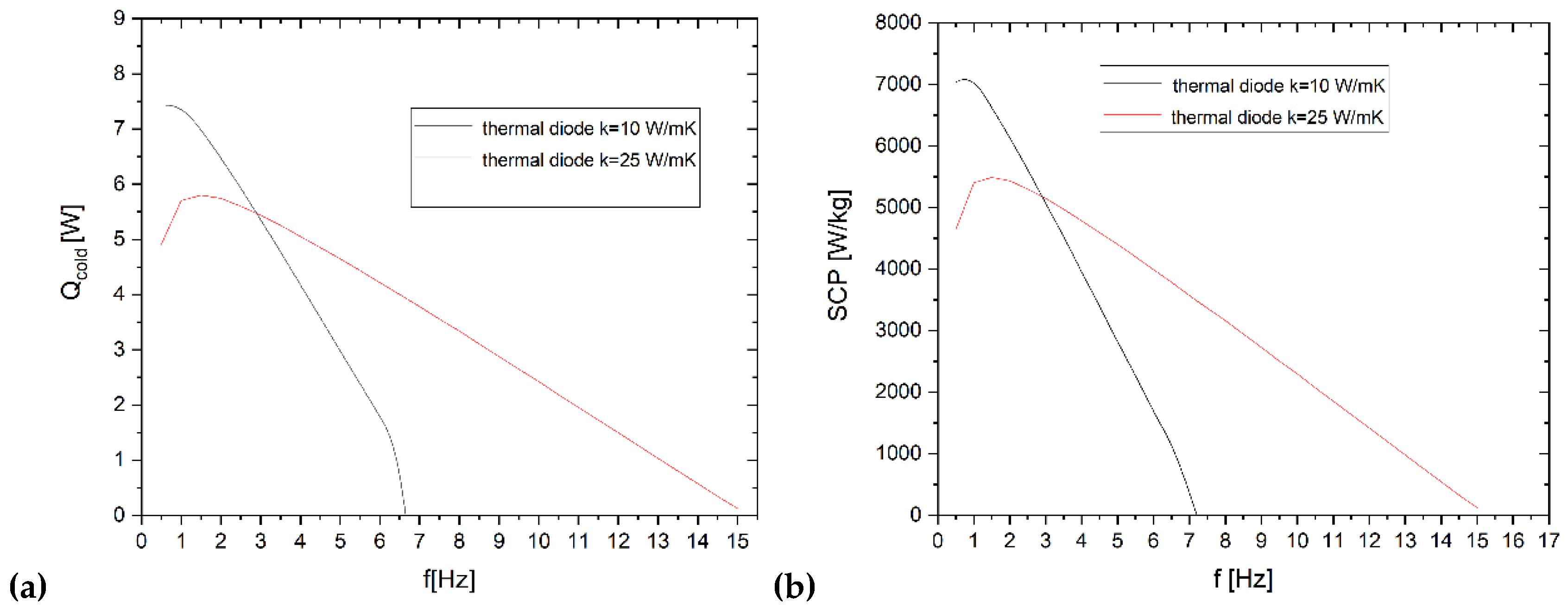

- Stemming that the quaternary NiTiCuV alloys has been chosen in the previous campaign of simulations as most performing material, the second campaign of simulations focuses on the influence of the ideal thermal diode as component for heat vechiculation: the system has been tested while mounting ITDs with different thermal conductivity: ITDs with a 2.5 times smaller thermal conductivity with respect to the former campaign were tested.

- iii)

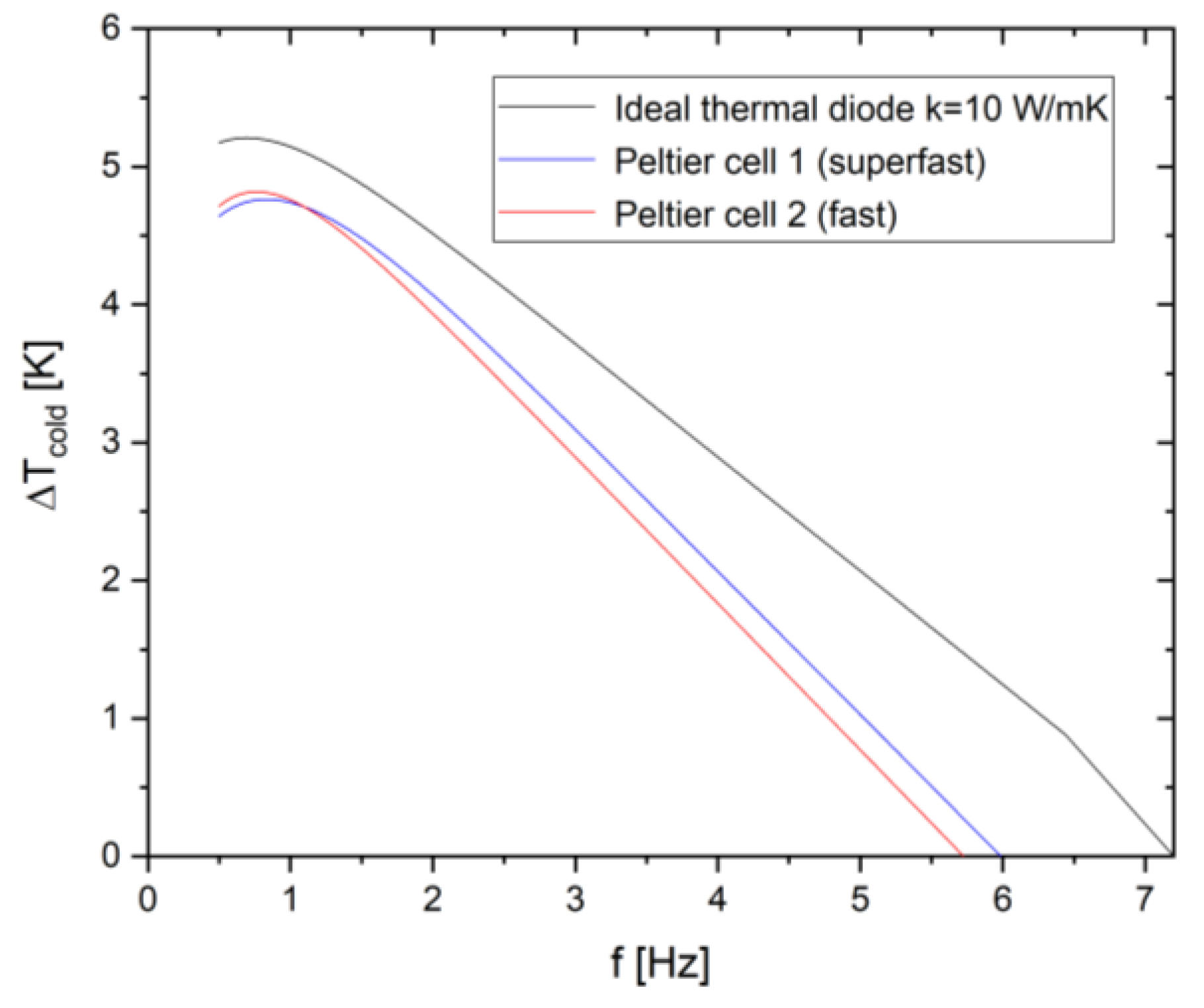

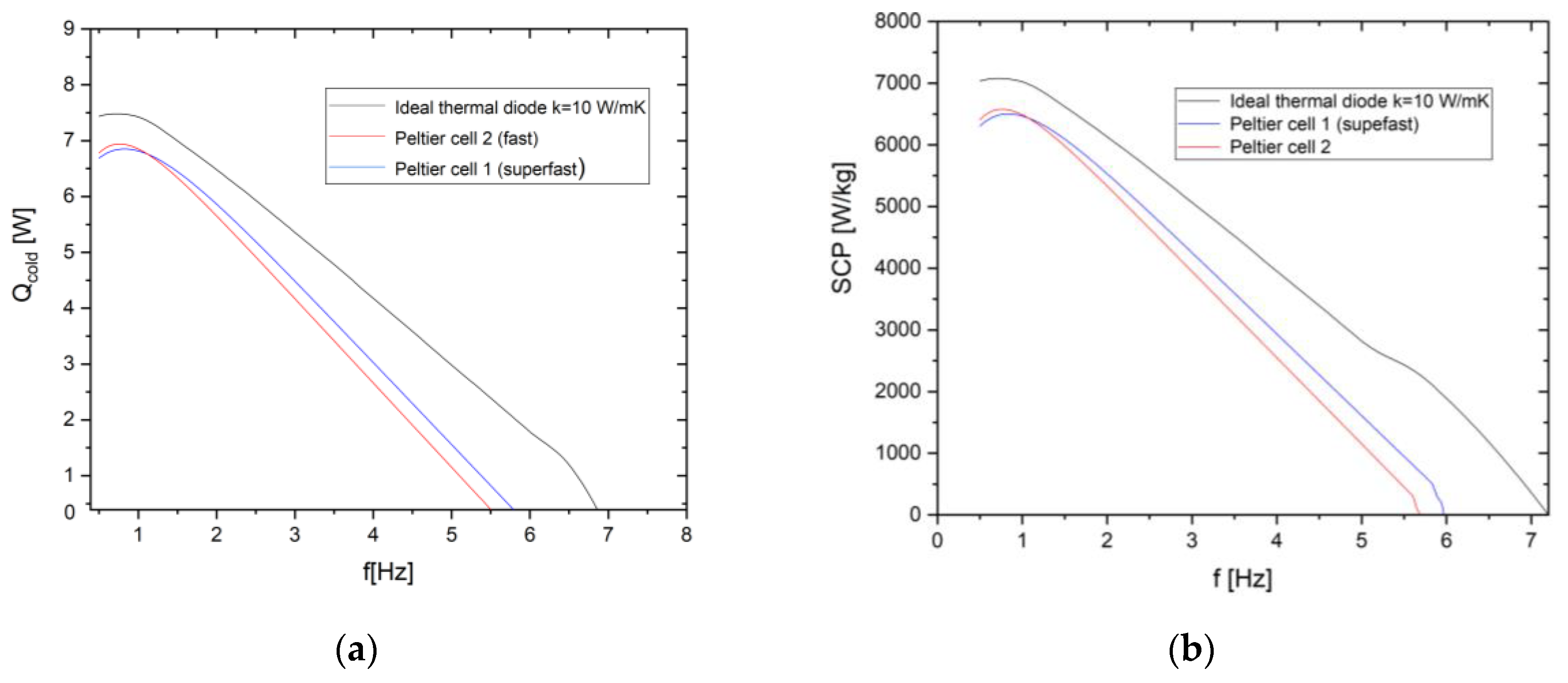

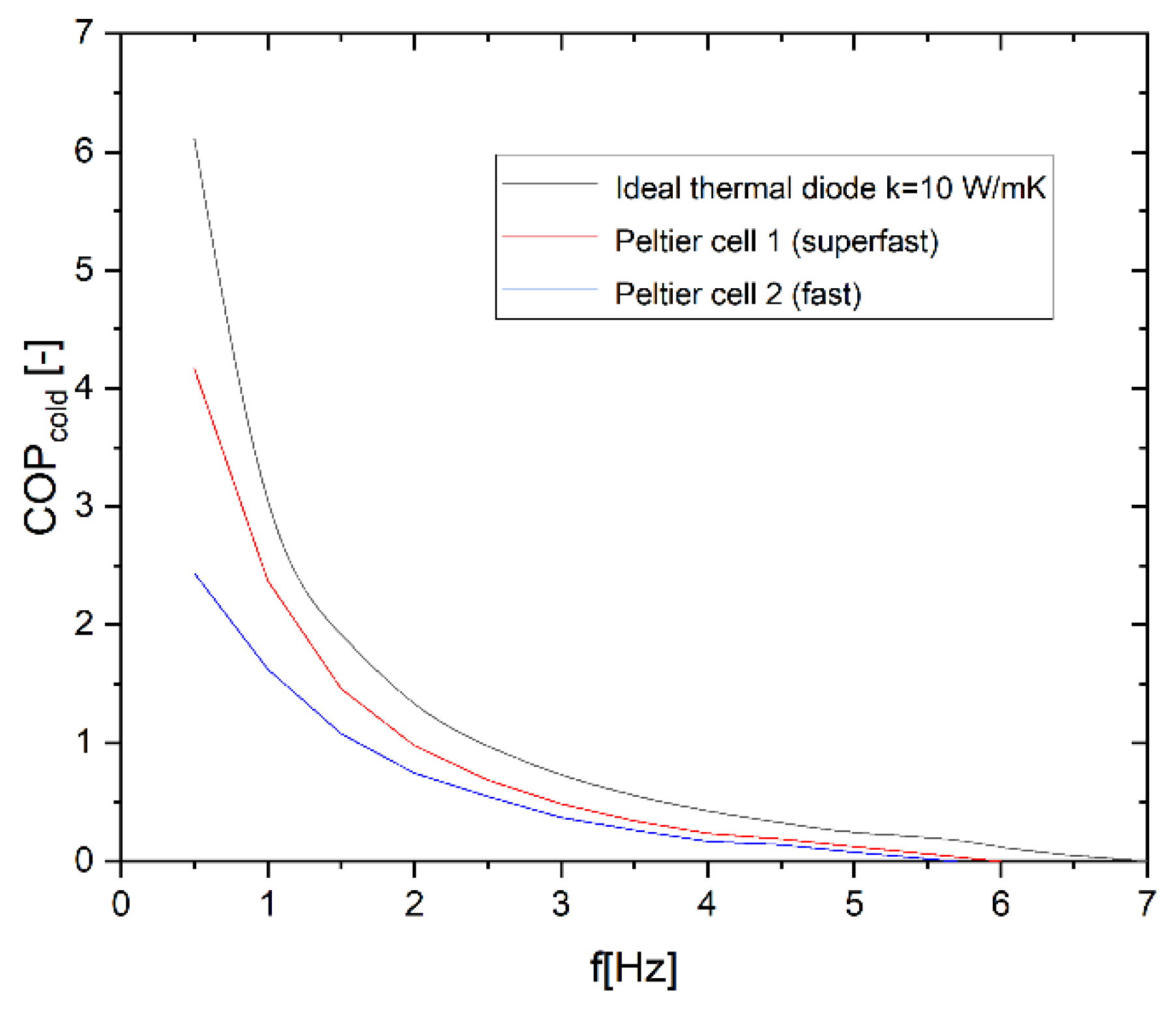

- As mentioned above, in the third campaign of simulations, two real Peltier cells types were modelled in the system to overcome the assumption of ideal thermal diodes and introduce physically realizable heat-transfer elements. Two representative Peltier modules, drawn from commercially available devices commonly used in thermal management applications, were considered, parametrized as fast and super-fast heat-switch configurations and introduced in section 3.3. As already introduced the two cells are characterized by different falling/rising ON/OFF times and an undesired small thermal conductivity during the OFF state. On the other side the thermal conductivity of the fast and superfast cells is modellable at a value around . For this reason, in this campaign of simulations the energy performances SSHT system mounting the fast and superfast Peltier elements are compared with the SSHT system performances working with ITDs with k=10

5. Conclusions

- the SSHT elastocaloric system exhibits a strong dependence on operating frequency, with cooling power and cold temperature span maximized at low frequencies and progressively degraded at higher frequencies due to limited heat-transfer time within each cycle.

- Thermal diode properties play a critical role in shaping system performance. Lower effective thermal conductivity enhances thermal confinement and increases the achievable temperature span at low frequencies, but at the cost of a reduced operational frequency range due to increased thermal resistance.

- Ideal thermal diodes provide an upper bound for system performance, enabling the highest cooling power, temperature span, and COP by eliminating switching delays and auxiliary energy consumption.

- When realistic Peltier-based heat switches are considered, a systematic reduction in performance is observed, primarily associated with finite switching dynamics and Joule losses introduced by the electrical driving of the thermoelectric modules.

- Despite these penalties, Peltier-based heat switches preserve the qualitative trends of the ideal-diode case and retain a significant fraction of the achievable performance, particularly in the low-to-moderate frequency regime.

- The electrical consumption of the Peltier modules has a limited impact on performance at low frequencies, where cooling power is relatively high, but becomes increasingly dominant at higher frequencies, leading to a rapid degradation of the system-level COP.

- Faster thermoelectric heat switches with lower electrical resistance consistently outperform slower alternatives, highlighting switching speed and electrical efficiency as key design parameters for practical SSHT implementations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Roman symbols | |

| an | analytical function |

| C | specific heat capacity, J kg-1 K-1 |

| COP | Coefficient Of Performance, - |

| D | Duty cycle, - |

| k | Thermal conductivity, W m-1 K-1 |

| I | Electrical current, A |

| Thermal power, W | |

| R | Electrical resistance of the Peltier module, Ω |

| s | entropy, J kg-1 K-1 |

| SCP | Specific Cooling Power, W kg-1 |

| T | temperature, K |

| t | time, s |

| Heat source due to elastocaloric effect, W m-3 | |

| V | Electrical tension, V |

| Input power to the system, W | |

| x | longitudinal spatial coordinate, m |

| y | orthogonal spatial coordinate, m |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | Total Seebeck effect of the Peltier module, VK-1 |

| Δ | Finite difference |

| strain, m | |

| Infinitesimal quantity | |

| density, kg m-3 | |

| Stress, MPa | |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | Initial |

| 1 | final |

| A | thermal diode A |

| ad | adiabatic |

| B | thermal diode B |

| cold | cooling |

| cycle | duration of the entire SSHT cycle |

| el | elastocaloric |

| hot | heating |

| load | loading |

| M | material |

| OFF | OFF state |

| ON | ON state |

| p | constant pressure |

| Peltier | proper of the Peltier element |

| s | solid |

| T | constant temperature |

| unload | unloading |

| Acronyms | |

| AeR | Active elastocaloric Regenerative |

| CHEX | Cold Heat EXchanger |

| COP | Coefficient Of Performance |

| eCE | elastoCaloric Effect |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HHEX | Hot Heat EXchanger |

| ITD | Ideal Thermal Diode |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| SMA | Shape Memory Alloy |

| SSHT | Solid-to-Solid Heat Transfer |

| TD | Thermal Diode |

References

- Elsayad, M. M.; Djuansjah, J.; Ataya, S.; Jang, S. H.; Meng, A.; Abdelgaied, M.; Sharshir, S. W. Case studies on elastocaloric technology-based solid-state cooling: A focus on materials and applications. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2025, 75, 107251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Cooling; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reshniak, V.; Cheekatamarla, P.; Sharma, V.; Yana Motta, S. A review of sensing technologies for new, low global warming potential (gwp), flammable refrigerants. Energies 2023, 16(18), 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W. T.; Tsai, C. H. A survey on fluorinated greenhouse gases in Taiwan: emission trends, regulatory strategies, and abatement technologies. Environments 2023, 10(7), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/573 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on fluorinated greenhouse gases, amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and repealing Regulation (EU) No 517/2014.

- Protocol, M. Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1987, 26, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, E. A. Amendment to the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer (Kigali amendment). International Legal Materials 2017, 56(1), 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, X.; Mathur, N. D. Caloric materials for cooling and heating. Science 2020, 370(6518), 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarkevich, N. A.; Zverev, V. I. Viable materials with a giant magnetocaloric effect. Crystals 2020, 10(9), 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitta, M.; Pełka, R.; Konieczny, P.; Bałanda, M. Multifunctional molecular magnets: Magnetocaloric effect in octacyanometallates. Crystals 2018, 9(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Jian, X.; Lin, X.; Yao, Y.; Tao, T.; Liang, B.; Lu, S. G. Enhanced electrocaloric effect in 0.73 Pb (Mg1/3Nb2/3) O3-0.27 PbTiO3 single crystals via direct measurement. Crystals 2020, 10(6), 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaleva, E. A.; Flerov, I. N.; Gorev, M. V.; Bondarev, V. S.; Bogdanov, E. V. Features of the behavior of the barocaloric effect near ferroelectric phase transition close to the tricritical point. Crystals 2020, 10(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, E. Y.; Yanushonite, E. I.; Eftifeeva, A. S.; Tokhmetova, A. B.; Kurlevskaya, I. D.; Tagiltsev, A. I.; Chumlyakov, Y. I. Elastocaloric effect in aged single crystals of Ni54Fe19Ga27 ferromagnetic shape memory alloy. Metals 2022, 12(8), 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, B. Influence of Stress on the Chiral Polarization and Elastrocaloric Effect in BaTiO3 with 180° Domain Structure. Crystals 2024, 14(6), 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañosa, L.; Planes, A. Elastocaloric effect in shape-memory alloys. Shape Memory and Superelasticity 2024, 10(2), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tušek, J.; Engelbrecht, K.; Millán-Solsona, R.; Mañosa, L.; Vives, E.; Mikkelsen, L. P.; Pryds, N. The Elastocaloric Effect: A Way to Cool Efficiently. Advanced Energy Materials 2015, (13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Zheng, L.; Yang, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, H. The current research status and development of elastocaloric refrigeration based on NiTi alloys. Next Materials 2024, vol. 5, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chluba, C.; Ge, W.; Lima de Miranda, R.; Strobel, J.; Kienle, L.; Quandt, E.; Wuttig, M. Ultralow-fatigue shape memory alloy films. Science 2015, 348(6238), 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Schütze, A.; Seelecke, S. Scientific test setup for investigation of shape memory alloy based elastocaloric cooling processes. International Journal of Refrigeration 2015, 54, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, P.; Žerovnik, A.; Ahčin, Ž.; Porenta, L.; Brojan, M.; Tušek, J. Elastocaloric cooling: state-of-the-art and future challenges in designing regenerative elastocaloric devices. Journal of Mechanical Engineering/Strojniški Vestnik 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, C. Y.; Chao, C. Y. Solid-state thermal diode with shape memory alloys. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2016, 93, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruederlin, F.; Bumke, L.; Chluba, C.; Ossmer, H.; Quandt, E.; Kohl, M. Elastocaloric cooling on the miniature scale: a review on materials and device engineering. Energy Technology 2018, 6(8), 1588–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruederlin, F.; Ossmer, H.; Wendler, F.; Miyazaki, S.; Kohl, M. SMA foil-based elastocaloric cooling: from material behavior to device engineering. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2017, 50(42), 424003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, H.; Hua, P.; Sheng, L. Continuous rotating bending NiTi sheets for elastocaloric cooling: Model and experiments. International Journal of Refrigeration 2023, 147, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Li, Z., Lv, C., Li, G., Huo, X., Wang, B., ... & Hou, H. Twistocaloric effect versus elastocaloric effect in shape memory alloys for low-force mechanocaloric design. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2024, 58(7), 075503. [CrossRef]

- Czernuszewicz, A.; Kaleta, J.; Lewandowski, D. Multicaloric effect: Toward a breakthrough in cooling technology. Energy conversion and management 2018, 178, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Ling, J.; Hwang, Y.; Radermacher, R.; Takeuchi, I. Thermodynamics cycle analysis and numerical modeling of thermoelastic cooling systems. International Journal of Refrigeration 2015, 56, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tušek, J.; Engelbrecht, K.; Mañosa, L.; Vives, E.; Pryds, N. Understanding the thermodynamic properties of the elastocaloric effect through experimentation and modelling. Shape Memory and Superelasticity 2016, 2(4), 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossmer, H.; Kohl, M. Elastocaloric cooling: Stretch to actively cool. Nature Energy 2016, 1(10), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, A.; Egolf, P. W. Innovative ideas for future research on magnetocaloric technologies. International journal of refrigeration 2010, 33(3), 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.; van der Meer, T. H. Application of Peltier thermal diodes in a magnetocaloric heat pump. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017, 111, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannella, G. A.; La Carrubba, V.; Brucato, V. Peltier cells as temperature control elements: Experimental characterization and modeling. Applied thermal engineering 2014, 63(1), 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomc, U.; Tušek, J.; Kitanovski, A.; Poredoš, A. A numerical comparison of a parallel-plate AMR and a magnetocaloric device with embodied micro thermoelectric thermal diodes. International journal of refrigeration 2014, 37, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEC1-12706 datasheet. Available online: https://peltiermodules.com/peltier.datasheet/TEC1-12706.pdf.

- SKHC1-07106C datasheet. Available online: https://www.digikey.com/en/products/detail/sheetak/SKHC1-071-06-C-T100-NS-TF00-ALO/12153420.

- Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Wu, E.; Li, W.; Li, L. The elastocaloric effect of Ni50. 8Ti49. 2 shape memory alloys. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2018, 51(13), 135303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A.; Frenzel, J.; Schmidt, M.; Maaß, B.; Seelecke, S.; Schütze, A.; Eggeler, G. Optimizing Ni–Ti-based shape memory alloys for ferroic cooling. Functionals Materials Letters 2017, vol. 10(n. 01), 1740001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Kirsch, S.M.; Seelecke, S.; Schütze, A. Elastocaloric cooling: From fundamental thermodynamics to solid state air conditioning. Science and Technology for the Built Environment 2016, 2374–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, L.; Greco, A.; Masselli, C. A Solid-to-Solid 2D Model of a Magnetocaloric Cooler with Thermal Diodes: A Sustainable Way for Refrigerating. Energies 2023, 16(13), 5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzacchiello, A.; Cirillo, L.; Greco, A.; Masselli, C. A comparison between different materials with elastocaloric effect for a rotary cooling prototype. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 235, 121344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).