Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data

Measurements

Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)

Depression

Covariates

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

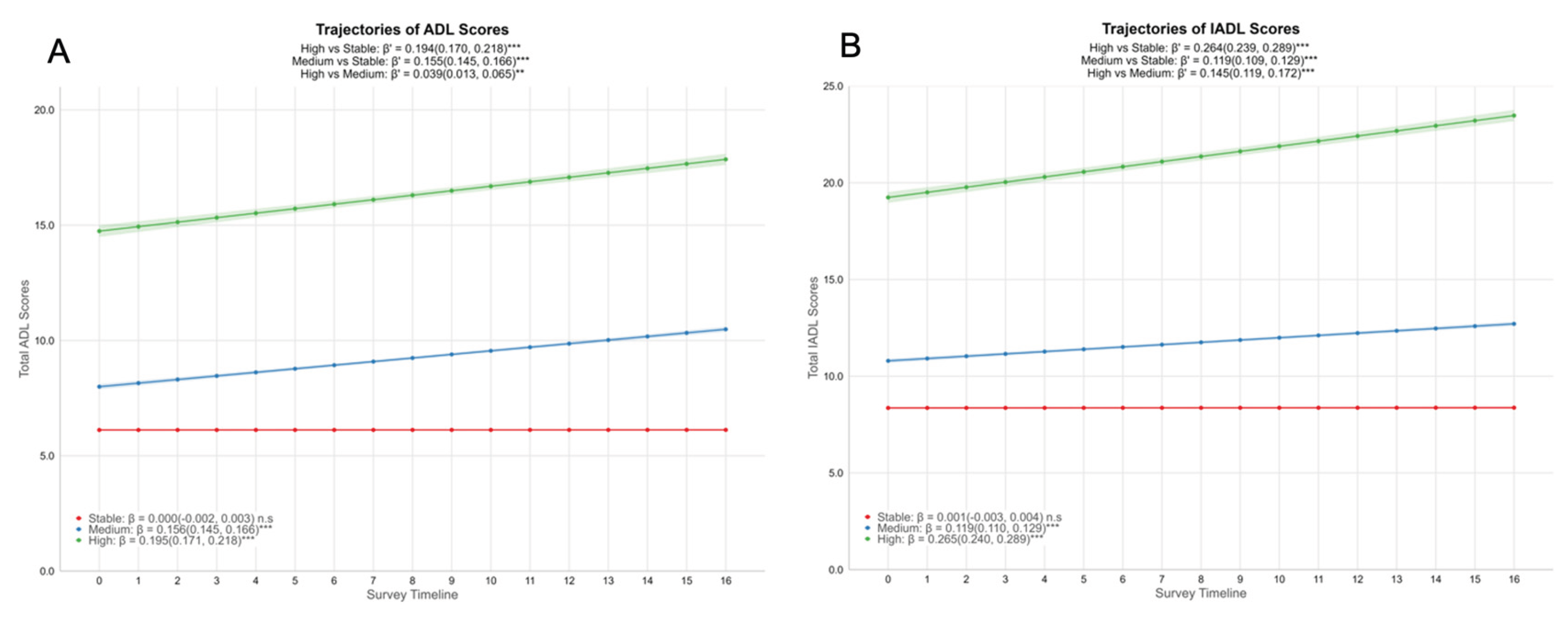

3.1. Identification of Functional Trajectories

3.2. Trajectory Clusters of Functional Decline

3.3. Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics of Trajectory Groups

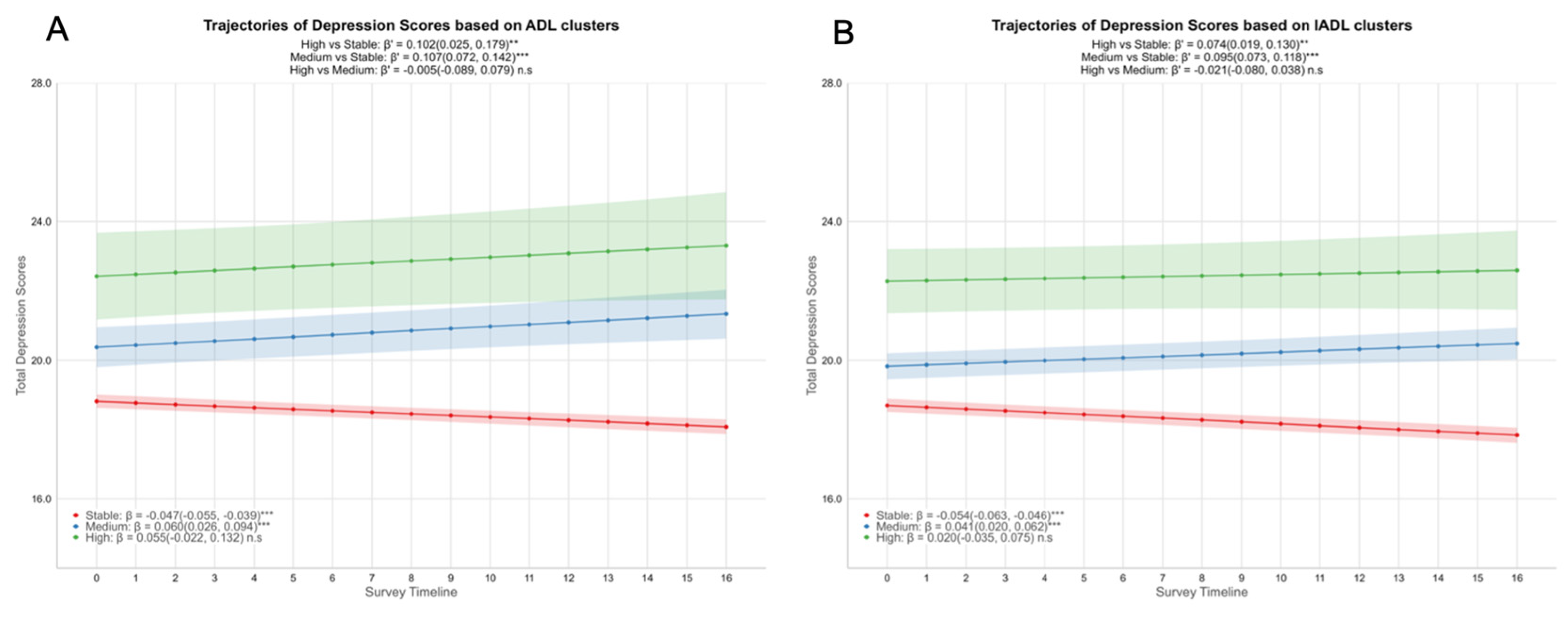

3.4. Depression Trajectories by Functional Clusters

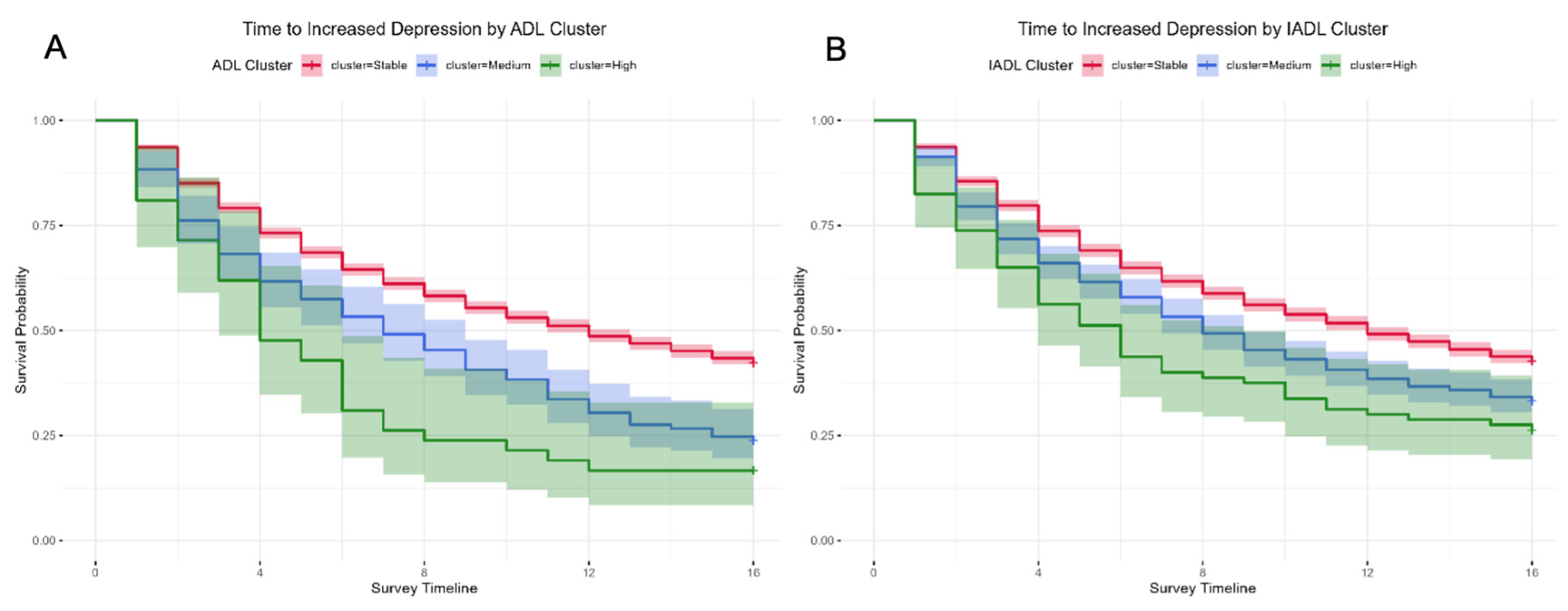

3.5. Incidence of Depression by Functional Trajectory Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WiSE | Well-being of Singapore Elderly |

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| IADLs | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| LCGA | Latent Class Growth Analysis |

| GBTM | Group-Based Trajectory Models |

| kml | k-means for longitudinal data |

| SLP | Singapore Life Panel® |

| CES-D | Centre for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale |

| CFQ | Cognitive Failures Questionnaire |

| CH | Calinski-Harabasz |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| HDB | Housing & Development Board |

References

- Longevity. Available online: https://www.population.gov.sg/our-population/population-trends/longevity/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- AshaRani, P.V.; Abdin, E.; Roystonn, K.; Devi, F.; Wang, P.; Shafie, S.; Sagayadevan, V.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Chua, B.Y.; Tan, B.; et al. Tracking the Prevalence of Depression Among Older Adults in Singapore: Results From the Second Wave of the Well-Being of Singapore Elderly Study. Depression and Anxiety 2025, 2025, 9071391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, J.W.; Guo, X.Y.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M.; Chen, C. Excess Costs of Depression among a Population-Based Older Adults with Chronic Diseases in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singapore’s Old-Age Support Ratio Nearly Halves in 10 Years, but Foreign Workforce Provides Buffer: MOM - The Business Times. Available online: https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/singapore/singapores-old-age-support-ratio-nearly-halves-10-years-foreign-workforce-provides-buffer-mom (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Proportion of One-Person Homes up amid Shrinking Household Sizes: HDB Survey - CNA. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/proportion-one-person-homes-up-shrinking-household-sizes-hdb-survey-5491071 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Ormel, J.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; Sullivan, M.; van Sonderen, E.; Kempen, G.I.J.M. Temporal and Reciprocal Relationship between IADL/ADL Disability and Depressive Symptoms in Late Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002, 57, P338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, N.; Sun, Y.; Bai, R.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, L. Exploring the Reciprocal Relationship between Activities of Daily Living Disability and Depressive Symptoms among Middle-Aged and Older Chinese People: A Four-Wave, Cross-Lagged Model. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Visaria, A.; Malhotra, R.; Chan, A. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS’ IMPACT ON CHRONIC DISEASES, FUNCTIONAL LIMITATIONS, AND MORTALITY. Innov Aging 2024, 8, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Lim, M.L.; Yap, K.B.; Ng, T.P. Changes in Depressive Symptoms and Functional Disability among Community-Dwelling Depressive Older Adults. International Psychogeriatrics 2012, 24, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edjolo, A.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Pérès, K.; Proust-Lima, C. Heterogeneous Long-Term Trajectories of Dependency in Older Adults: The PAQUID Cohort, a Population-Based Study over 22 Years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020, 75, 2396–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, J.; Murayama, H.; Ueno, T.; Saito, M.; Haseda, M.; Saito, T.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Functional Disability Trajectories at the End of Life among Japanese Older Adults: Findings from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Allore, H.; Murphy, T.; Gill, T.; Peduzzi, P.; Lin, H. Dynamics of Functional Aging Based on Latent-Class Trajectories of Activities of Daily Living. Ann Epidemiol 2013, 23, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, Y.; Abe, Y.; Takayama, M.; Arai, Y. Six-Year Transition Patterns of Activities of Daily Living in Octogenarians: Tokyo Oldest Old in Total Health Study. BMC Geriatrics 2025, 25, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.M.; Allore, H.G.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Murphy, T.E. Change in Disability after Hospitalization or Restricted Activity in Older Persons. JAMA 2010, 304, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Sun, S.; Huang, L.; Guo, Y.; Shi, Y.; Qi, S.; Ding, G.; Wen, Z.; Wang, J.; Ruan, Y.; et al. Effect of Social Participation on the Trajectories of Activities of Daily Living Disability among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A 7-Year Community-Based Cohort. Aging Clin Exp Res 2024, 36, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mésidor, M.; Rousseau, M.-C.; O’Loughlin, J.; Sylvestre, M.-P. Does Group-Based Trajectory Modeling Estimate Spurious Trajectories? BMC Med Res Methodol 2022, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peristera, P.; Platts, L.G.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Westerlund, H. A Comparison of the B-Spline Group-Based Trajectory Model with the Polynomial Group-Based Trajectory Model for Identifying Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms around Old-Age Retirement. Aging Ment Health 2020, 24, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, R.P.; Annis, I.E.; Killeya-Jones, L.A.; Fang, G. Opening the Black Box of the Group-Based Trajectory Modeling Process to Analyze Medication Adherence Patterns: An Example Using Real-World Statin Adherence Data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2020, 29, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genolini, C.; Alacoque, X.; Sentenac, M.; Arnaud, C. Kml and Kml3d: R Packages to Cluster Longitudinal Data. J. Stat. Soft. 2015, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, S.; Zola, J.; Lee, R.; Hu, J.; MacKenzie, B.; Brickman, A.; Anaya, G.; Sinha, S.; Li, A.; Elkin, P.L. Longitudinal K-Means Approaches to Clustering and Analyzing EHR Opioid Use Trajectories for Clinical Subtypes. J Biomed Inform 2021, 122, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demnitz, N.; Anatürk, M.; Allan, C.L.; Filippini, N.; Griffanti, L.; Mackay, C.E.; Mahmood, A.; Sexton, C.E.; Suri, S.; Topiwala, A.G.; et al. Association of Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms with Vascular Risk, Cognitive Function and Adverse Brain Outcomes: The Whitehall II MRI Sub-Study. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 131, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Saito, M.; Aida, J.; Cable, N.; Tsuji, T.; Koyama, S.; Ikeda, T.; Osaka, K.; Kondo, K. Association between Social Isolation and Depression Onset among Older Adults: A Cross-National Longitudinal Study in England and Japan. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balqis-Ali, N.Z.; Fun, W.H. Social Support in Maintaining Mental Health and Quality of Life among Community-Dwelling Older People with Functional Limitations in Malaysia: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Gao, J. Associations between Trajectories of Social Participation and Functional Ability among Older Adults: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1047105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Yu, H.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Su, J.; Wang, L.; Lei, X. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Trajectories and Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment among Chinese Older Adults: Results of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, 2002–2018. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithianathan, R.; Hool, B.; Hurd, M.D.; Rohwedder, S. High-Frequency Internet Survey of a Probability Sample of Older Singaporeans: The Singapore Life Panel®. The Singapore Economic Review 2021, 66, 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, S.; Levecque, K.; Bracke, P. Measurement Equivalence of the CES-D 8 in the General Population in Belgium: A Gender Perspective. Arch Public Health 2009, 67, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wu, X.; Lin, N.; Xie, X.; Cai, M.; Wang, M.; Zheng, L.; Xu, L. Different Cutoff Values for Increased Nuchal Translucency in First-Trimester Screening to Predict Fetal Chromosomal Abnormalities. Int J Gen Med 2021, 14, 8437–8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.; Tan, W.S.; Gunapal, P.P.; Wong, L.Y.; Heng, B.H. Association of Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Social Support with Depressive Symptoms among the Elderly in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap 2014, 43, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS Social Support Survey. Social science & medicine 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, M.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raymond, É. Inventory and Analysis of Definitions of Social Participation Found in the Aging Literature: Proposed Taxonomy of Social Activities. Social science & medicine 2010, 71, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; FitzGerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and Its Correlates. British journal of clinical psychology 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genolini, C.; Falissard, B. KmL: K-Means for Longitudinal Data. Computational Statistics 2010, 25, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton-Cole, R.; Ayis, S.; O’Connell, M.D.L.; Smith, T.; Sheehan, K.J. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults and in Adults With Hip Fracture: Analysis From the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2022, 77, 2453–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; Sha, K.; Liu, Y. The Effect of Cognitive Function Heterogeneity on Depression Risk in Older Adults: A Stratified Analysis Based on Functional Status. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Hou, M. Changes in Daily Living Dependency and Incident Depressive Symptoms among Older Individuals: Findings from Four Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ Ment Health 2025, 28, e301749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Phillips, C.; Coppin, A.K.; van der Linden, M.; Ferrucci, L.; Fried, L.; Guralnik, J.M. An Association between Incident Disability and Depressive Symptoms over 3 Years of Follow-up among Older Women. Aging Clin Exp Res 2009, 21, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanner Kristiansen, C.; Kjær, J.N.; Hjorth, P.; Andersen, K.; Prina, A.M. Prevalence of Common Mental Disorders in Widowhood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord 2019, 245, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Zwinge, E.; König, M. The Relationship between Home Modifications and Frailty among Older Adults: A Scoping Review Protocol. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0335822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanton, S.L.; Xue, Q.-L.; Leff, B.; Guralnik, J.; Wolff, J.L.; Tanner, E.K.; Boyd, C.; Thorpe, R.J.; Bishai, D.; Gitlin, L.N. Effect of a Biobehavioral Environmental Approach on Disability Among Low-Income Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med 2019, 179, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unützer, J.; Park, M. Strategies to Improve the Management of Depression in Primary Care. Prim Care 2012, 39, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. The Vicious Cycle of Depressive Symptoms and Disability in Older Adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2025, 29, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Meng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, H. Bidirectional Association between ADL Disability and Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults: Longitudinal Evidence from CHARLS. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardá-Espinosa, A. Time-Series Clustering in R Using the Dtwclust Package. The R Journal 2019, 11, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | ADL Cluster | p-value2 | IADL Cluster | p-value2 | ||||

| Stable | Medium | High | Stable | Medium | High | |||

| N = 4,0171 | N = 2141 | N = 421 | N = 3,6371 | N = 5561 | N = 801 | |||

| Baseline Age | 63 (59, 68) | 66 (62, 72)α | 70 (62, 74) α | <0.001 | 63 (59, 67) | 68 (63, 72) α | 71 (65, 75) α,† | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.909 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 1,919 (94.2%) | 100 (4.9%) | 19 (0.9%) | 1,791 (87.9%) | 214 (10.5%) | 33 (1.6%) | ||

| Female | 2,098 (93.9%) | 114 (5.1%) | 23 (1.0%) | 1,846 (82.6%) | 342 (15.3%) | 47 (2.1%) | ||

| Marital Status | 0.081 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married | 3,234 (94.3%) | 164 (4.8%) | 33 (1.0%) | 2,965 (86.4%) | 412 (12.0%) | 54 (1.6%) | ||

| Single | 370 (95.1%) | 15 (3.9%) | 4 (1.0%) | 343 (88.2%) | 37 (9.5%) | 9 (2.3%) | ||

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 413 (91.2%) | 35 (7.7%) | 5 (1.1%) | 329 (72.6%) | 107 (23.6%) | 17 (3.8%) | ||

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No/Primary | 1,213 (88.9%) | 124 (9.1%) | 27 (2.0%) | 932 (68.3%) | 374 (27.4%) | 58 (4.3%) | ||

| Secondary | 1,116 (96.0%) | 41 (3.5%) | 6 (0.5%) | 1,055 (90.7%) | 98 (8.4%) | 10 (0.9%) | ||

| Post-Secondary | 944 (95.9%) | 36 (3.7%) | 4 (0.4%) | 912 (92.7%) | 65 (6.6%) | 7 (0.7%) | ||

| University | 744 (97.6%) | 13 (1.7%) | 5 (0.7%) | 738 (96.9%) | 19 (2.5%) | 5 (0.7%) | ||

| Housing | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1-3 room HDB | 689 (89.2%) | 65 (8.4%) | 18 (2.3%) | 569 (73.7%) | 170 (22.0%) | 33 (4.3%) | ||

| 4-5 room HDB | 2,406 (94.3%) | 128 (5.0%) | 18 (0.7%) | 2,182 (85.5%) | 333 (13.0%) | 37 (1.4%) | ||

| Private Housing | 922 (97.2%) | 21 (2.2%) | 6 (0.6%) | 886 (93.4%) | 53 (5.6%) | 10 (1.1%) | ||

| Number of Chronic Diseases | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (1, 3) α | 3 (2, 4) α,† | <0.001 | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (1, 3) α | 3 (2, 4) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline ADL Scores | 6 (6, 6) | 7 (6, 10) α | 15 (12, 18) α,† | <0.001 | 6 (6, 6) | 6 (6, 7) α | 11 (6, 15) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline IADL Scores | 8 (8, 9) | 11 (8, 15) α | 23 (18, 27) α,† | <0.001 | 8 (8, 8) | 11 (9, 12) α | 19 (15, 24) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline Total Depression Scores | 19.0 (15.0, 23.0) | 25.0 (20.0, 29.0) α | 29.0 (25.0, 33.0) α,† | <0.001 | 19.0 (15.0, 23.0) | 22.0 (18.0, 27.0) α | 27.0 (23.0, 32.0) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline Social Support Scores | 26.0 (21.0, 29.0) | 21.0 (18.0, 27.0) α | 22.0 (17.0, 28.0) α | <0.001 | 26.0 (21.0, 29.0) | 23.0 (20.0, 28.0) α | 23.0 (17.0, 28.0) α | <0.001 |

| Baseline Social Isolation Scores | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.0) α | 3.0 (3.0, 4.0) α,† | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) α | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline Social Engagement Scores | 0.9 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.0) α | 0.1 (0.0, 1.0) α | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.6 (0.1, 1.3) α | 0.1 (0.0, 0.9) α,† | <0.001 |

| Baseline Total CFQ scores | 38.0 (33.0, 42.0) | 33.0 (30.0, 39.0) α | 30.0 (23.0, 37.0) α | <0.001 | 38.0 (33.0, 42.0) | 35.0 (30.0, 40.0) α | 30.0 (24.0, 39.0) α,† | <0.001 |

| Cluster | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Outcome; overall event rate | Log-rank p-value | Median Time (Waves) | Event Rate | ||

| ADL | Model 1 | Stable | 1 | Depression increased by 5 points or more; 58.9% event rate | <0.001 | 12 (3.0 years) | 57.7% |

| Medium | 1.46 (1.24, 1.71) *** | 7 (1.75 years) | 76.2% | ||||

| High | 1.82 (1.30, 2.57) *** | 4 (1.0 years) | 83.3% | ||||

| Model 2 | Stable | 1 | |||||

| Medium | 1.31 (1.11,1.55) ** | ||||||

| High | 1.57 (1.11, 2.22) ** | ||||||

| Model 3 | Stable | 1 | |||||

| Medium | 1.35 (1.14, 1.59) *** | ||||||

| High | 1.65 (1.17, 2.33) ** | ||||||

| IADL | Model 1 | Stable | 1 | Depression increased by 5 points or more; 58.9% event rate | <0.001 | 12 (3.0 years) | 57.4% |

| Medium | 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) ** | 8 (2.0 years) | 66.7% | ||||

| High | 1.38 (1.05, 1.80) * | 6 (1.5 years) | 73.8% | ||||

| Model 2 | Stable | 1 | |||||

| Medium | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) * | ||||||

| High | 1.21 (0.92, 1.59) | ||||||

| Model 3 | Stable | 1 | |||||

| Medium | 1.16 (1.03, 1.31) * | ||||||

| High | 1.29 (0.98, 1.70) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).