1. Introduction

1.1. Population Segmentation in Health & Healthcare Systems

Population segmentation is a critical planning and development activity in health systems, aimed at enabling more efficient system functioning. It forms a core component of value-driven strategies for improving outcomes and value in health and healthcare systems.

Segmentation uses defined criteria representing specific characteristics of the population to design “segmentation models”. The aim of segmentation models is to distribute the population into homogenous “sub-populations” with similar characteristics [

1]. These defined criteria or specific characteristics are usually chosen based on their potential impact on the health systems’ outcome/s-of-interest, and inability to address or intervene on these specific characteristics therefore, in effect, represents a risk of “non-attainment” of the outcome/s-of-interest.

Effective segmentation models enable stratification of the population into smaller sub-populations based on different levels of risk. This stratification allows for the design of more targeted “segment-specific interventions” that can address specific characteristics more appropriately and efficiently, thereby mitigating the risks of poor outcomes [

1]. Consequently, the use of segmentation models enables more targeted services planning and resource allocation, increasing overall health services and system efficiency.

Population segmentation can be implemented at the macrosystem, mesosystem, or microsystem levels of a health system, optimizing different outcomes depending on the system level [

1,

2]. For example, macrosystem segmentation models are typically applied at the level of the whole population enrolled with a health system and are usually designed by the Governance and Leadership System of health systems. Macrosystem segmentation models are focused on forming mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive subgroups based on differential levels of overall risk for key outcomes such as healthcare utilization and overall healthcare costs [

1]

In contrast, mesosystem and microsystem segmentation models focus on specific subpopulations within the health system, such as people living with chronic disease who utilize expensive healthcare services frequently, or elderly populations with varying levels of frailty and socio-economic status. These models aim to improve outcomes relevant to specific providers, programs, or organizations, often for specialized program redesign [

3,

4]. Additionally, microsystem segmentation models may employ disease-, discipline- and/or profession-based clinical or specialty criteria, to generate patient segments with different disease/sub-specialty severity, to facilitate the design of disease- or site-based care paths for provider teams. The primary goals are to optimize condition-specific outcomes and efficiently allocate specialized resources.

It is important to note that while mesosystem and microsystem segmentation models serve valuable purpose, they often have considerable overlaps and gaps in their specific characteristics and outcomes of interest. Unlike macrosystem segmentation models, they are not usually mutually exclusive or collectively exhaustive of the whole population.

1.2. International Context

With population aging and increasing chronic disease burden [

5], health systems worldwide are experiencing escalating costs and facing challenges in ensuring sustainable access to quality healthcare services. As a result, health system financing mechanisms are increasingly moving away from “fee-for-service” towards “bundled funding”, or other population-based funding mechanisms such as “capitation”, to sustain patient care outcomes within more constrained financial resources [

6,

7]. These financing policy changes effectively pass the financial risks of healthcare provision, from the level of whole health systems down to subsidiary systems or organizations, such as provider systems e.g., integrated care organizations or hospital-systems, or “third-party” organizations e.g., accountable care organizations or health insurers.

This shift in financial risk has significant implications for healthcare delivery and planning. As subsidiary provider systems and healthcare organizations take on this financial risk, they must consider macrosystem healthcare utilization and overall cost-of-care as key outcomes that the mesosystem and microsystem levels must ultimately contribute towards. This shift necessitates a rethinking and redesign of segmentation models commonly used by these entities for mesosystem and microsystem services and resource planning and allocation, especially in relation to how they work together to enable macrosystem populations segment outcomes more effectively.

1.3. Local Context

In response to these changes, we have observed a trend in Singapore where provider organizations, including hospital systems, are exploring the use of macrosystem population segmentation models for patients within their geographical catchment areas. The primary aim is to reduce the utilization of expensive hospital care and, consequently, costs-of-care [

8]. In concert, the expectation to manage financial risks has also driven Singapore hospital systems to increasingly initiate “upstream” macrosystem population segment-specific interventions. These interventions include enhanced primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention activities aimed at reducing healthcare costs and mitigating financial risks [

9].

In 2017, the National Healthcare Group (NHG), comprising three integrated care organizations—Yishun Health (YH), Central Health, and Woodlands Health—renewed its mission to prioritize community health over solely patient-centric healthcare needs. This transformation involved reorganizing Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (a 795-bed acute hospital), Yishun Community Hospital (a 428-bed sub-acute, rehabilitative, and palliative care hospital), and Admiralty Medical Centre (an ambulatory care center) into Yishun Health. As an integrated care organization serving 320,000 residents within the Yishun Zone Regional Population Health System in Northern Singapore, Yishun Health’s role expanded beyond mere healthcare service provision. Instead, it now collaborates with care partners within the zone to enhance residents’ health and well-being, integrate care, and optimize the outcomes and value of the Yishun Zone Regional Population Health System [

10]. Plans were also being developed for Yishun Health to manage healthcare utilization and cost-of-care outcomes and assume a significant portion of the financial risk of healthcare services provision for residents living within the Yishun Zone.

Operating within this context, YH initiated numerous health system and services transformation initiatives to accelerate the development of a people-centered, integrated and value-driven regional population health system. A key initiative was the development and adoption of a set of design principles for the Unified Care Model (UCM) with its subsidiary Lifelong Care and Episodic Care services models to guide the development of the YH future-state integrated and value-based Service Delivery System. Salient features of the UCM that impact population segmentation include 1) the UCM embracing the expanded purpose of meeting population health needs, measured through metrics such as resident health-related experience, quality-of-life, and levels of protective health factors, 2) patient care outcomes of provider organizations continue to be important but are subsidiary within these broader outcomes, 3) the costs of attaining outcomes will be measured across all providers to optimize resident and patient value, 4) the subsidiary integrated care models of Lifelong Care and Episodic Care subsystems seek to meet the totality of health needs of the Yishun Zone population, as well as the sporadic health needs arising from acute crisis and/or complex elective medical events respectively, and are therefore collectively exhaustive of residents with those needs within the Yishun Zone population, 5) within both the Lifelong Care and Episodic Care system are microsystems representing smaller sub-populations with distinct needs that make up the larger population e.g., people living well and living with chronic illness in Lifelong Care (mutually exclusive), patients requiring Acute Stroke care and Pneumonia within Episodic Care (non-mutually exclusive).

1.4. Care Model Implications for Health System Population Segmentation Models

Population segmentation models are increasingly utilized to optimize outcomes across various level of the health system [

11]. However, the rationale behind selecting specific criteria for population segmentation are often not immediately apparent or transparent. It is also unclear how the different population segment-specific interventions that help to achieve outcomes for their respective population segments, whether and how they are related to segment-specific interventions at the macrosystem level, and systemically, whether they come together effectively and efficiently in generating whole health system outcomes.

For instance, instead of focusing on characteristics directly impacting a person’s lifelong functional health outcomes in spite of his/her acute disease condition, a hospital provider system may deploy microsystem and mesosystem segmentation models based upon provider-centric criteria such as medical subspecialty or disease-specific criteria or requirements only, and then try to improve patient function and experience outcomes only within the context (and competencies) of a medical specialty or disease treatment pathway, leaving continuity and coordination of person-centred functional outcomes attainment that is beyond the ambit of particular medical subspecialty or disease-specific pathways to other, often less resourced, care providers elsewhere in the health system (macrosystem).

In other words, there can be different degrees of disconnect between a health system’s stated goals of person-centred outcomes and the actual criteria used for population segmentation at the microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystems level. Indeed, the causal relationship between selected characteristics for population segmentation and the health system’s desired outcomes can be complex, and in some instances, may be insufficiently examined, tenuous or even wrong.

While this does not mean that the desired person-centred outcomes are not important or not being attained, it does, however, mean that segmentation-specific interventions that are based on population segmentation models that are not needs based or that are not systemically linked to macrosystem segmentation models are unlikely to be effectively designed and even less likely to be efficient, in terms of improving person-centred whole health system outcomes.

While existing segmentation models at the mesosystem and microsystem levels remain relevant, especially for subsidiary systems and provider organizations, there’s an increasing need to ensure that mesosystem and microsystem outcomes align with the desired outcomes at the macrosystem level. This is particularly crucial in the context of broader prevention strategies and sustainable health system cost management. New approaches to population segmentation at the mesosystem and microsystem levels must address these tensions while maintaining operational efficiency and avoiding excessive cost-cutting or care rationing. They must also find a solution to ensure person-centered health outcomes and experiences. This situation therefore demands a comprehensive and systemic design approach to population segmentation.

1.5. Systemic Health System Population Segmentation—Singapore Case Study

In a well-defined health system, changes to the context and therefore the definition of the health systems’ macrosystem outcomes and its macrosystem population segmentation model will have cascading effects. The criteria for mesosystem (e.g., cohorts) and microsystem (e.g., high-risk populations) segmentation models and their interdependencies with each other within the broader macrosystem framework will each require re-definition or clarification to ensure their distinctiveness and efficiency across different levels of the health system.

The changing local context of YH has therefore driven us to embark on systemic redesign and comprehensive redefinition of our population segmentation criteria and models spanning across macrosystem, mesosystem, and microsystem levels of our regional population health system’s service delivery model based on the Unified Care Model.

We adopted population needs-based criteria [

8] to understand health determinants across the entire population to facilitate more effective delivery of person-centred health services to sub-populations or segments with similar health needs, regardless of individual disease status [

12,

13]. Recognizing the continued importance of mesosystem and microsystem segmentation models within a macrosystem population health system, we therefore also propose a clear relationship and interdependency between population needs-based health system segmentation models at the macrosystem level and utilization-based or disease-treatment based models or at the mesosystem and microsystem levels. This paper aims to:

Introduce a novel Systemic Health System Population Segmentation Model approach that is person-centred and needs-based to enable health system redesign.

Describe the Lifelong Care Segmentation and Sub-segmentation Models for the macrosystem and mesosystem levels of the Service Delivery System of a health system, based on the UCM.

Describe the Episodic Care Segmentation Model for the mesosystem and microsystem levels of the Service Delivery System of a health system, based on the UCM.

Illustrate the development process and evaluation results of these models.

This clarification will illustrate how various population segmentation models can work together to provide a systemic approach to health system design, enabling more systemic services planning and resource allocation to enhance care integration, outcomes, and value at the whole population health system level. Such an approach will facilitate more effective segment-specific integrated care delivery and service planning [

14] and provide insights that may be valuable to other health systems facing similar challenges in population health management and integrated care delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

The NHG had developed a River of Life (ROL) framework to meet health needs for the entire population segmented to five segments of care covering both lifelong care needs—Living Well, Living with Illness, Living with Frailty and Leaving well, and episodic care needs—Crisis and Complex Care [

15]. However, biological conditions e.g., presence of chronic disease and/or frailty status alone do not fully reflect the lifelong needs of the population [

16]. Also, the disease and/or frail groups could have very diverse needs which warrants further sub-segmentation to enable more targeted interventions. Furthermore, the episodic care needs are often triggered in the form of an escalation, rather than in isolation, from the base lifelong needs. YH enhance the ROL segmentation model by: 1. incorporating stage of disease trajectory and population psychosocial needs into the Lifelong Segmentation (LS) model; 2. further sub-segmenting population with chronic diseases and/or frailty into the needs-based sub-segmentation (NBSS) model and 3. incorporating sporadic needs into lifelong base needs to develop an Episodic Segmentation (ES) model [

17].

There are two major approaches for population segmentation tool development. Expert-driven approach and data-driven approach [

8]. YH adopted an expert-driven approach in the interim, while initiating the collection of more comprehensive population needs and outcomes data through our Yishun Health Population Health Survey 2022. A multidisciplinary team of internal experts was assembled, comprising clinicians, public health and health system and services planning consultants, and data scientist and data analysts. This diverse group collaboratively selected and defined both the population inclusion/exclusion criteria and the segmentation criteria, ensuring a holistic perspective in the development process.

2.1. Lifelong Care Segmentation (LS) Model Development

The development of the Lifelong Segmentation (LS) model was underpinned by the following key guiding principles: 1) Instead of using provider-centred approach such as disease condition- or healthcare utilization-based criteria, we adopted a set of person-centred and needs-based segmentation criteria. This means that the model must consider the entire population and the full spectrum of needs that influences an individual’s health outcomes. Based on literature review [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] and inputs from our team of experts, we selected segmentation criteria that consider an individual’s holistic needs across their Bio-Psycho-Social spectrum. These criteria encompass the stage of chronic illness, the presence of mental health conditions, and social issues [

17]. 2) Segments must be sufficiently discriminatory and mutually exclusive, ensuring that the population within each segment shares similar health needs. Conversely, across each segment, people should have systematically well-differentiated healthcare needs. 3) Additionally, segments must collectively be exhaustive of all residents in Yishun Zone. By adhering to these criteria, the LS aims to assist policy-makers in planning services, evaluating outcomes, and tracking progress.

We first identified the total number of residents who reside in the Yishun Zone Planning Area based on census data from the Singapore Department of Statistics (2022) [

18], and includes Singapore citizens or permanent residents who reside in the catchment area of Yishun Zone. Next, using the existing and readily available data points that reflect or serve as surrogates for the segmentation criteria mentioned above, we identified residents who visited YH in 2022 for lifelong segmentation. These data points were found within YH’s Central Data Repository (CDR), a comprehensive data repository that integrates administrative, clinical, and financial data from various data and IT source systems within the organization. A list of 38 chronic illnesses and their ICD-10 codes was used to identify if a resident had prior chronic disease diagnoses (

Table 1). All past historical primary and secondary ICD-10 diagnosis codes of the residents were included in the analysis. To ascertain if the chronic illnesses were “early” or “advanced” in terms of disease progression, we referred to the resident’s Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs), ICD-10 codes and SNOMED codes of their chronic disease diagnosis. If the chronic disease diagnosis codes indicated the presence of complications or complications were identified by clinician’s review, we defined such resident to be at an advance stage of chronic illness. To determine if a patient had mental health issues, we referred to a list of ICD-10 codes from the World Health Organization (WHO) that denoted mental and behavioural disorders. To identify social Issues, we checked if the resident had prior visits to medical social workers (MSW), or if they resided in public rental housing as a proxy of low socio-economic status (SES). Patients with Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) statuses with a cut-off score >7 were classified under the “Leaving Well” segment.

After applying above segmentation criteria, seven Lifelong Care segments with increasing complexity of lifelong care needs were derived forming our needs-based Lifelong Care Segmentation Model. The seven Lifelong Care segments (LS) are: LS1. Living Well, LS2. Living Well with Social Issues, LS3. Early Disease, LS4. Early Disease with Psychosocial Issues, LS5. Advanced Disease, LS6. Advanced Disease with Psychosocial Issues, and LS7. Leaving Well.

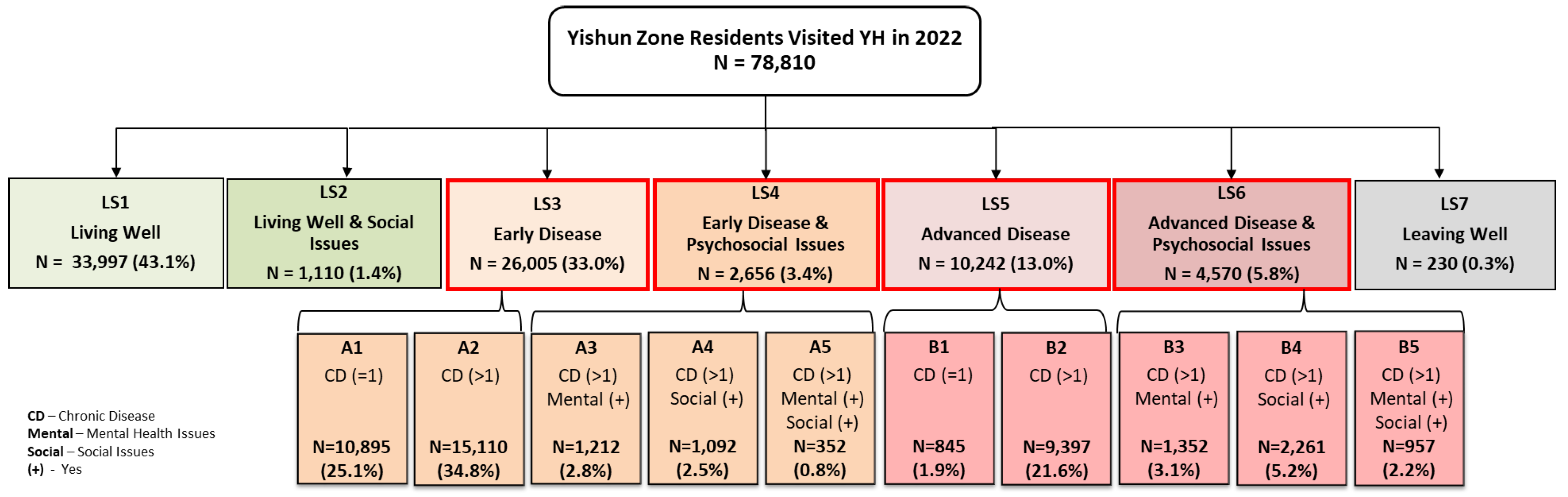

2.2. Further Needs-Based Sub-Segmentation Model (NBSSM) Development

To facilitate the design of more targeted, subsegment-specific services, for segments with more intense needs, residents with chronic diseases (categorized in LS3 to LS6) underwent further sub-segmentation using the Needs-Based Sub-Segmentation Model (NBSSM) (

Table 2). This additional layer of segmentation allowed for a more granular understanding of the diverse needs of residents living with chronic diseases, enabling the development of more tailored interventions and services.

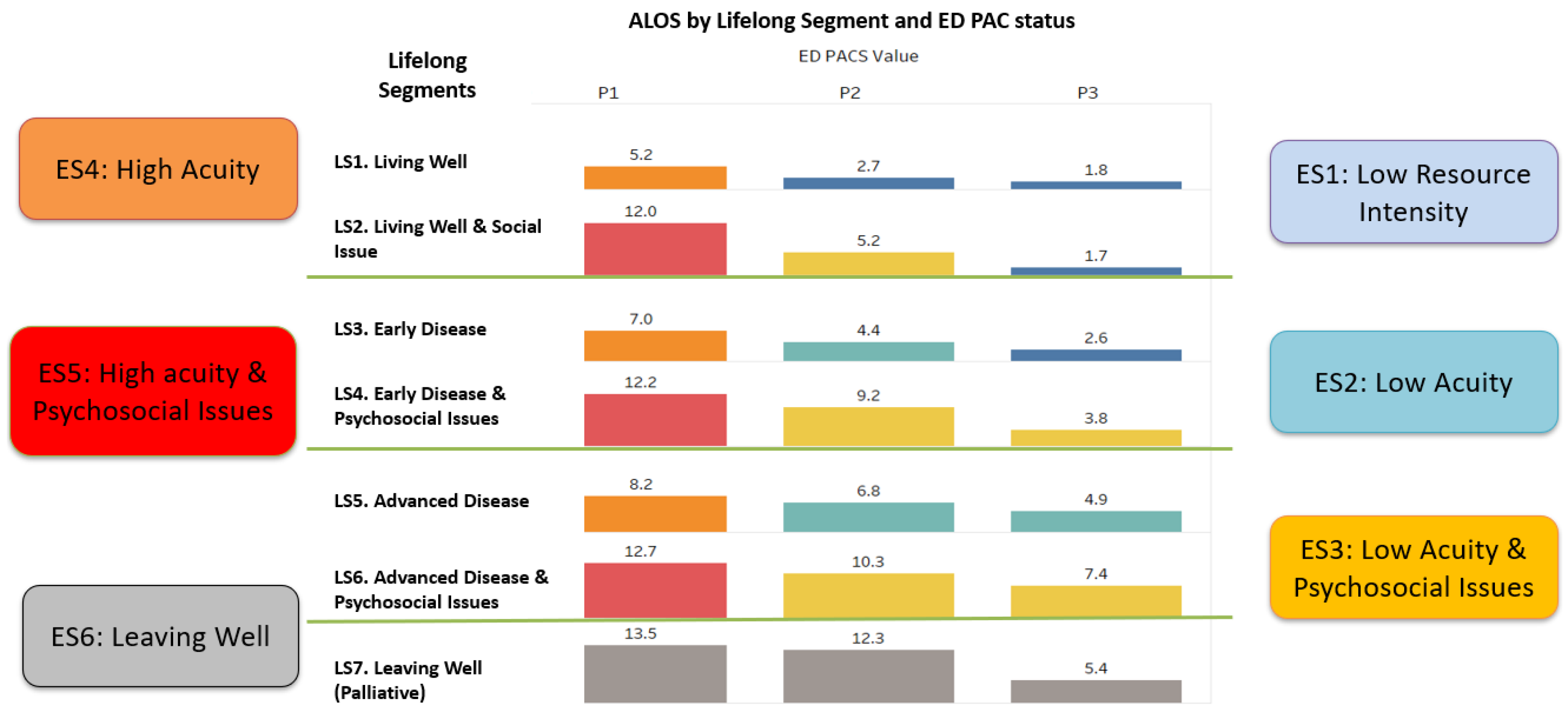

2.3. Episodic Care Segmentation (ES) Model Development

Whilst Lifelong Care segments represent the ongoing, base needs of a resident living in the community, when crisis and complex care needs occur, leading to urgent acute hospital admissions, there is an escalation of needs which under the UCM is termed i.e., episodic care needs. Therefore, the Episodic Care Segmentation (ES) model was developed as a systemic extension of the Lifelong Care Segmentation model, specifically for residents admitted to YH through the emergency department. This model incorporates different levels of episodic care needs, as quantified by the Patient Acuity Category Scale (PACS) value. By layering acute care needs over the existing Lifelong Care Segmentation model, the ES model provides a more comprehensive yet systemic view of differing patient person-centred needs during their acute episodes, facilitating more systemic and therefore effective and efficient care delivery for the whole health system. With reference to average length of stay (ALOS) as the key outcome, six Episodic Care Segments (ES) were derived, namely, ES1. Low Resource Intensity, ES2. Low Acuity, ES3. Low Acuity with Psychosocial Issues, ES4. High Acuity, ES5. High Acuity with Psychosocial Issues, and ES6. Leaving Well. (

Figure 1)

2.4. Health System Population Segmentation Model Evaluation

Evaluation was aimed at understanding the respective segmentation model’s ability to segment Yishun Zone residents into mutually exclusive groups that are relatively homogenous in terms of lifelong and episodic healthcare needs, and that these groups were meaningfully distinct—crucial in rationalising the customization of care plans and the dedication of resources to each segment.

To evaluate if the NBSSM was able to generate segments of people with uniquely distinct needs, we correlated the segments to various population health outcomes [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] or surrogates, starting with readily available data in our CDR, including healthcare utilisation and cost in the latest year that residents visited YH i.e., number and cost of visits and admissions to our hospital’s emergency department, specialist outpatient clinics, and inpatient ward, and the annual hospitalization bed days. The statistical distinction and difference between population segments across the outcome measures was also studied.

To evaluate the ability of our ES model in generating groups of patients with distinct level of episodic care needs, statistical difference between the ES using available outcome data, i.e., ALOS, inpatient admission cost and 30-day emergency readmission, were examined.

The Konstanz Information Miner (KNIME) Analytics Platform version 4.6.3 (KNIME, Zurich, Switzerland) was used for the preparation of data. SPSS version 27 was used to conduct chi-square test for categorical variables, linear regression and one-way ANOVA tests for continuous variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

During the preparation of this manuscript, Pair Chat (an AI language model developed by Open Government Products, Singapore) was used for proofreading and language improvement. The authors reviewed, verified, and edited all AI-assisted content and take full responsibility for the final content of the manuscript. No AI tools were used for analysis or generation of scientific content.

3. Results

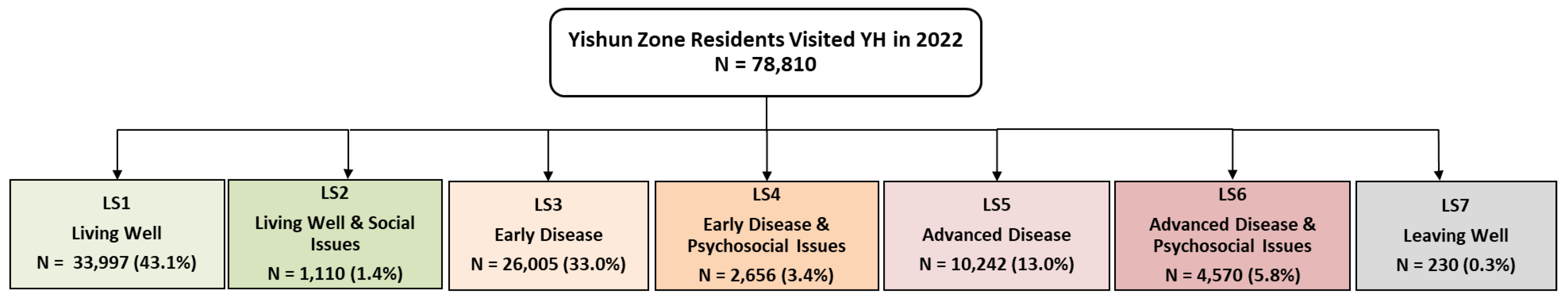

In year 2022, a total of 78,810 residents known to Yishun Health was segmented into seven Lifelong Care segments. (

Figure 2).

A large proportion of residents were Living Well (43.1%) or Living with Early Disease (33.0%) and do not have psychosocial issues. As shown in

Table 3, there was an increasing trend in age and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score with increased complexity of lifelong care needs across LS1 to LS7. CCI is the most widely used index used to determine survival rate in patients with multiple comorbidities [

25].

43,473 residents with chronic disease who had visited YH in 2022 were sub-segmented by the NBSSM (

Figure 3). Segmentation data shows that a majority of the residents with chronic disease were at an early stage and without psychosocial needs (A1 & A2). Comparatively smaller number of residents were living with mental and/or social issues (A3-A5 & B3-B5).

Table 4 shows that sub-segments of residents with complex needs were older and with higher CCI scores.

For residents who visited YH in 2022, using their healthcare utilization data from 2022 as a proxy for health outcomes,

Table 5 shows that the NBSSM correlates well with population needs which resulted in different future health outcomes. Sub-segments with higher needs i.e., residents with multiple or advance chronic illness, mental illness, and/or social issues are more likely to have statistically significantly higher number of visits to emergency department specialist outpatient clinics, inpatient admissions, annual hospitalized bed days, and annual overall healthcare costs in the subsequent year. It was also observed that mental health and/or social issues were the key risk factors associated with significantly higher healthcare utilization and cost.

Based on the Episodic Care Segmentation (ES) model, there were 14,335 emergency admissions to YH in 2022, classified into six Episodic Segments (ES1-ES6). A large proportion are at the “low acuity” spectrum with or without mental/social issues (ES1-ES3). Sub-segments with higher acuity and/or with mental/social issues are associated with longer ALOS, higher inpatient admission cost and higher rate of 30-day emergency readmission. Furthermore, the presence of mental/social issues was observed to be the key driver of poorer outcomes amongst sub-segments with similar level of acuity. (

Table 6)

4. Discussion

Population segmentation models, operating at different levels of a health system, were designed for various legitimate purposes but lacked coordination towards a common goal. The evolving global health landscape, driven by chronic diseases, aging populations, and rising public expectations, necessitates a more person-centered, needs-based integration of care with strong coordination and continuity. This shift has strained resources, leading to the cascading of cost-outcomes to and affecting subsidiary systems such as provider organizations. To address this, there is an urgent need for greater alignment of outcomes across all system levels of health systems.

Macrosystems have the potential to adopt more person-centered outcomes beyond cost and utilization. They can align more closely with individual and community needs by moving beyond cost and utilization metrics as primary concerns. This will enable health system stewards to meet rising public expectations. On the other hand, mesosystems and microsystems, which traditionally focus on specialty or disease-based outcomes, now require a more value-based and integrated approach. They need services models that can be evaluated systemically using person-centered care models like the UCM towards greater effectiveness at the whole health system level. This will provide a better value proposition to health system stewards, governments, and ultimately citizens. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity to redesign population segmentation models to help align services models. This should particularly focus on the interrelationships between models at the macrosystem, mesosystem, and microsystem levels.

In order to transform the health system service delivery model from fragmented, provider-centred [

1] services models towards the UCM, our systemic whole of Health System Population Segmentation Model comprising Lifelong Care Segmentation Model, Needs-Based Sub-segmentation Model (NBSSM) and Episodic Care Segmentation Models have demonstrated effectiveness in categorizing the Yishun Zone resident population into distinct, mutually exclusive, and collectively exhaustive groups at all levels of the Service Delivery system of the Yishun Zone Regional Population Health System. These groups, characterized by similar health needs, show strong correlations with both risk magnitude and health outcomes. This alignment underscores the models’ potential for enhancing targeted healthcare delivery and resource allocation.

The purpose of care improvement, integration and healthcare and health system redesign and transformation can therefore be thought of as the pursuit of services redesign and resource allocation that more effectively address these specific characteristics, to enhance outcomes or mitigate the risks of poor outcomes for different population segments or sub-populations. [

26,

27]. After applying the needs-based segmentation criteria, we found that a majority of the residents have lower levels of health needs, with no or early stage diseases. Their conditions could therefore be managed by primary healthcare providers. Only a comparatively smaller number of residents are living with multiple or complex medical conditions with mental and/or social issues and are therefore considered higher in health and health-related social needs. They may require more skilful service providers with a multidisciplinary team to provide integrated coordinated and continuous care in order to meet needs. It was also observed that increases in medical complexity or acuity alone did not result in significantly poorer outcome in terms of increased healthcare utilization and cost. However, residents with mental health and/or social issues were associated with significantly higher healthcare utilization and cost. This demonstrated that mental and social issues were the key risk factors for poor health outcome and that services models must emphasize the understanding of such needs and design into their services model more personalized care and support processes. Our person-centred needs-based segmentation models therefore enable health system and services planning that potentially enables better accountability assignment, resource allocation, more tailored services delivery and integrated care by different providers or institutions and outcome evaluation.

Macrosystem segmentation models can also be thought of as “demand-sided” segmentation models representing the needs of residents/patients that can be used to align or harness the care by different “supply-sided” segmentation models and their services models focusing on meeting the needs of specific cohorts of interest to a profession/specialty, a disease-type, or an institution and the services they provide e.g., acute care services.

Supply-sided mesosystem or microsystem-level patient segmentation models can generate “mutually exclusive subsegments” that exhaustively include all patients meeting the service model’s inclusion criteria. These models may individually lead to more patient-centric care for specific disease-based patient populations. However, from a systemic perspective, when taken together at the level of the macrosystem or population health system, these numerous supply-sided mesosystem and microsystem-level segmentation models cease to be mutually exclusive. Since patients are cared for by providers and processes designed for multiple overlapping patient segments, supply-sided patient segmentation models paradoxically undermine the patient-centricity they aim to create. Ultimately, this undermines the ability to achieve genuine integrated and value-driven care. [

28]. In addition, disease- and healthcare utilization-based criteria appear to have been used by provider-oriented systems to design segmentation models that are actually meant for their macrosystem or their population health systems. [

8,

14,

29]. We posit that this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the criteria driving the type and quantity of risks to outcomes-attainment at the macrosystem versus at lower levels of the system, such as at the mesosystem and microsystem levels of a population health system.

Our Systemic Health System Population Segmentation Models can clarify this and therefore help enhance whole health system planning while helping develop more targeted interventions to meet residents’ needs and improve population health outcomes at different health system levels. For instance, NBSSM assigns residents with similar needs to respective Primary Coordinating Doctors (PCD) and their care teams accountable for their lifelong health outcomes. [

30]. This model enables PCDs to estimate workload, plan resources, and design segment-specific interventions to meet residents’ needs. It also advocates a person-centered perspective by assimilating lifelong and episodic needs to improve episodic care outcomes. This systemic approach is more holistic as it considers sporadic crisis care needs alongside lifelong needs during acute hospital stays, leading to more coordinated and continuous discharge care plans supporting patients’ transition back to lifelong care in the community.

In addition, the ES model offers an innovative approach to conventional bed management and resource allocation in acute hospitals. By segmenting patients upon admission, patients can be immediately assigned to the appropriate care team with the necessary resources, such as generalists, specialists, or medical social workers, to treat and manage different levels of acuity and social issues. This improves operational efficiency, shortens unnecessary patient stays in acute hospitals, and lowers financial risks for both the hospital system and patients.

Last but not least, our Systemic Health System Population Segmentation Model approach is generalizable and can be replicated to other regional health systems or at the national level for needs-based stratification, services planning, and outcome projection, including utilization and cost. It also enables more coherent management of regional population health systems by enabling the tracking of outcomes of each population group over time, e.g., PCD owners of LS segments, owners of ES segment outcomes, and therefore the entire health system.

A limitation of our current models is the availability of needs and outcomes data which were restricted to administrative data in our electronic medical record system. As such, information about resident’s health literacy, health-related behaviours, functional status, caregiver availability, detailed mental and social issues and utilizations in other non-Yishun Health institutions were not included. Moving forward, the opportunity will be to conduct more comprehensive and in-depth needs and asset assessment such as collecting of resident functional needs and more detailed social needs to improve our Systemic Health System Population Segmentation Models. To develop a comprehensive population needs and asset assessment tool, YH has conducted a Population Health Survey to collect such needs data from our Yishun Zone residents. Data from the survey linked with administrative data from electronic medical records will be used to enhance our segmentation models. However, in order to have a sustainable and scalable data collection platform for conducting the population needs assessment and segmentation, a standardized and seamlessly connected IT transactional system is needed. It will provide data on residents’ needs and assets for care plan formation at individual level, and services and healthcare resource planning at population level. It will also allow continuous iterative refinement of the segmentation models.

5. Conclusions

Yishun Health’s person-centred and needs-based Health System Population Segmentation Models—comprising the Lifelong Care Segmentation Model, Needs Based Sub-Segmentation Model, and Episodic Care Segmentation Models—were effective in segmenting the Yishun Zone resident population into mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive groups with similar types of health needs. These population groups demonstrated distinct outcome profiles and differing magnitudes of risk, reinforcing the utility of the segmentation models in supporting more targeted and integrated care delivery.

More fundamentally, the segmentation models functioned not only as analytic tools but also as core structural mechanisms for aligning health system planning, governance, and services design around the differentiated needs of population segments. In doing so, they enabled clearer delineation of accountability, more appropriate allocation of resources, and facilitated more coherent development of care models to meet biopsychosocial needs across both lifelong and episodic care contexts.

Taken together, the lifelong, sub-segmentation and episodic segmentation models have catalysed more purposeful service integration and system redesign that takes into consideration the critical impact of psychosocial issues above and beyond disease complexity or acuity. When embedded within the broader Unified Care Model and supported by standardised performance frameworks, they serve as foundational enablers of population health system transformation—advancing care integration, value creation, and ultimately, improved health outcomes for the population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A/Prof Ng Yeuk Fan and Dr Hu Yun; Methodology, /Prof Ng Yeuk Fan, Dr Hu Yun and Lee Wah Yean; Data analysis, Lee Wah Yean; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Dr Hu Yun and A/Prof Ng Yeuk Fan; Review & Editing, Dr Hu Yun, Lee Wah Yean, Dr Teo Ken Wah and A/Prof Ng Yeuk Fan,; Visualization Dr Hu Yun and Lee Wah Yean; Supervision, A/Prof Ng Yeuk Fan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the contributions from Yishun Health clinicians and domain knowledge experts who provided inputs for the development of the various Health System Population Segmentation mentioned in this paper. They are Prof Chua Hong Choon, A/Prof Phoa Lee Lan, A/Prof Toh Hong Chuen, A/Prof Pek Wee Yang, A/Prof Tan Kok Yang, A/Prof Terence Tang, Dr Ang Yan Hoon and Dr Wong Sweet Fun.

Funding

This project received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this project as it involved analysis of existing administrative data without individual patient identifiers.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was not required as the study used existing administrative data without individual patient identifiers.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality restrictions, as they contain patients’ medical and social information. The dataset was derived from Yishun Health’s Central Data Repository (CDR) containing administrative, clinical, and financial data. Requests to access the aggregated datasets may be considered by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to approval from the relevant institutional data protection office and governance committees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lynn, J. Using Population Segmentation to Provide Better Health Care for All: The “Bridges to Health” Model. The Milbank Quaterly 2007, 85, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuil, S.I. Patient Segmentation Analysis Offeres Significant Benefits For Integrated Care And Support. Health Affaires. 2016, 35, 769–775. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J.L. Do healthcare needs-based population segments predict outcomes among the elderly? Findings from a prospective cohort study in an urbabized low-income community. BMC Geriatrics. 2020, 20, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.L. Population Segmentation Based on Healthcare Needs: Validation of a Brief Clinician-Administered Tool. Society of General Internal Medicine 2020, 36, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzman, R. Health in an ageing world--what do we know? Lancet. 2015, 385, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, M. Population-based integrated care funding values and guiding principles: An empirical qualitative study. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e24904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck da Silva Etges, A.P. Value-Based Reimbursement as a Mechanism to Achieve Social and Financial Impact in the Healthcare System. Journal of Health Economics and Outcomes Research. 2023, 10, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.L. Assessing the validity of a data driven segmentation approach: A 4 year longitudinal study of healthcare utilization and mortality. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0195243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkrishnan, R. Capitation Payment, Length of Visit, and Preventive Services: Evidence From a National Sample of Outpatient Physicians. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2002, 8, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, K.W. Health System Transformation Playbook & Yishun Health Unified Care Model: A Design, System and Complexity Thinking Enabled Approach to Health System and Services Transformation. 2022.

- Yan, S. A systematic review of the clinical application of data-driven population segmentation analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A. Person-centred care: what is it and how do we get there? Future Hospital Journal 2016, 3, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.L. Evaluation of a pratical expert defined approach to patient population segmentation: a case study in Singapore. BMC Health Service Research. 2017, 17, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NationaL Healthare Group. River of Life: NHG’s Perspectives on Population Health.; National Healthcare Group Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ravaghi, H. A scoping review of community health needs and assets assessment: concepts, rationale, tools and uses. BMC Health Services Research. 2023, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Psychodynamic Psychiatry. 2012, 40, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics. Population and Population Structure 2019. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/population-and-population-structure/latest-data. Accessed 17/11/2022.

- Arnetz, B.B. Enhancing healthcare efficiency to achieve the Quadruple Aim: an exploratory study. BMC Research Notes. 2020, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Annuals of Family Medicine. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.F. Value-based focused global population health management. Journal of Gastrointestingal Oncology. 2021, 12 (Suppl 2), S275–S289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, E.R. Measuring Population Health in a Large Integrated Health System to Guide Goal Setting and Resource Allocation: A Proof of Concept. Population Health Management. 2019, 22, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, R.G. Measuring Population Health Outcomes. Precenting Chronic Disease Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, C.S. The use of Electronic Health Records to Support Population Health: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Medical Systems. 2018, 42, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S. A systematic review of the clinical application of data-driven population segmentation analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choon, J.L. Population segmentation based on healthcare needs: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I. Person-Centered Care—Ready for Prime Time. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewner, S. Aligning population-based care management with chronic disease complexity. Nurs Outlook. 2014, 62, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.A. Liability Implications of Physician-Directed Care Coordination. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005, 3, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).