1. Introduction

The existence of gravitational waves (GWs) was first predicted theoretically by Einstein using his theory of General Relativity (GR) [

1]. Unlike electromagnetic radiation, GWs are produced by quadrupole sources rather than dipoles, allowing Einstein to describe the rate of energy loss due to GW emission. GWs arise from perturbations in the spacetime metric caused by asymmetries such as binary systems, deformations in compact objects like neutron stars (NSs), or density fluctuations during inflation. The GW signal is typically classified into three phases: inspiral, merger, and ringdown. During inspiral, a compact binary slowly loses energy via GW emission, increasing in frequency and amplitude. The merger produces the peak GW signal as the objects coalesce, followed by the ringdown, dominated by the relaxation of the remnant and emission of decaying quasinormal modes [

2].

The first direct GW detection occurred in 2015 when LIGO observed GW150914 from a binary black hole merger [

3], opening a new era of GW astronomy. Ground-based interferometers like LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA (forming the LVK collaboration) currently operate in the 10 Hz–10 kHz range and have detected over 100 compact object mergers. However, signals below 10 Hz remain inaccessible, motivating larger ground-based detectors such as the 40 km Cosmic Explorer and Einstein Telescope, as well as space-based observatories like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) [

4] and the Lunar Gravitational Wave Antenna (LGWA) [

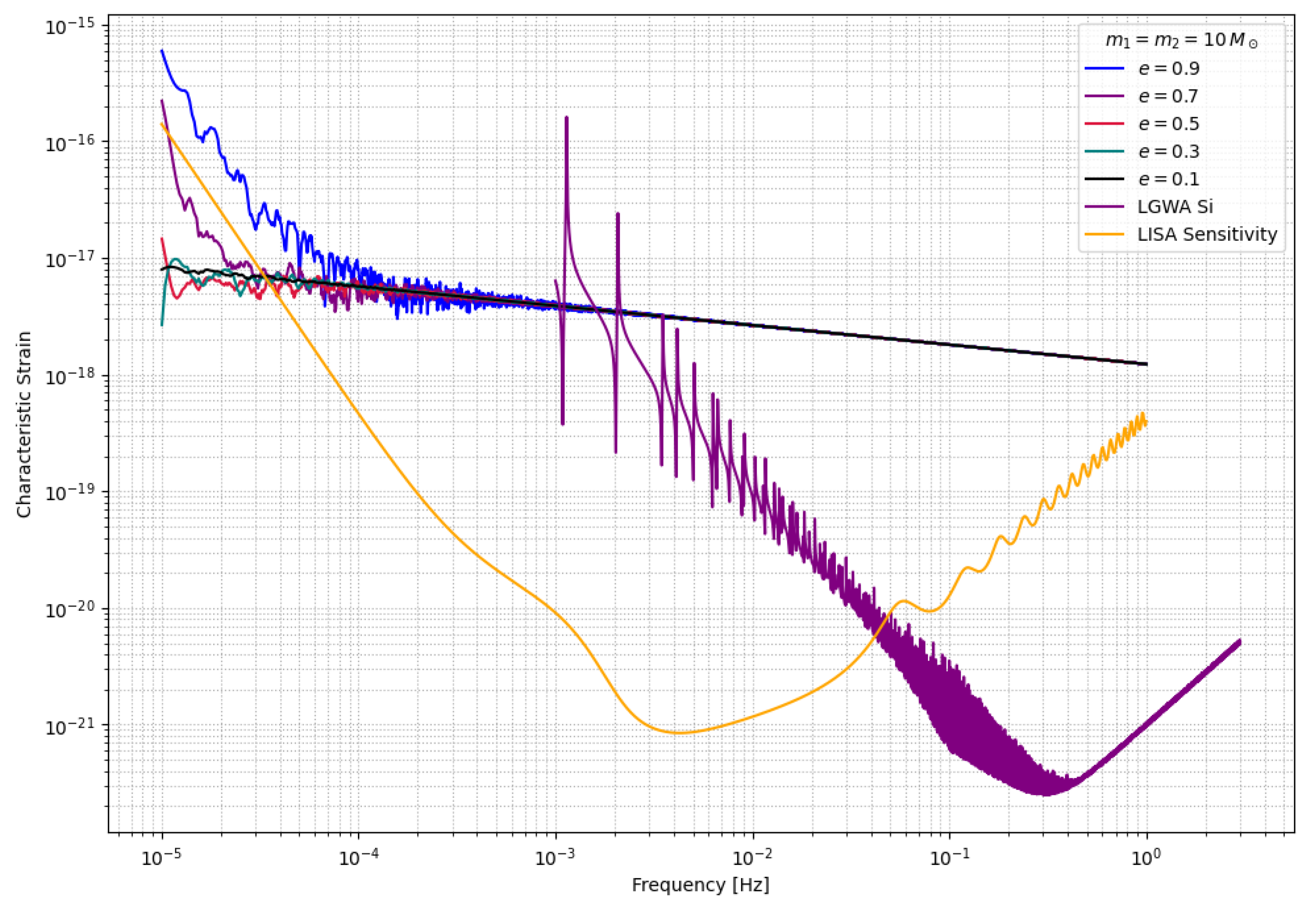

5]. These extended sensitivities are crucial for detecting eccentric binaries, whose GW emission is distributed over multiple harmonics and is more efficient than that from circular orbits [

6,

7]. The total radiation power P averaged over one orbital period is given by

where

and

are the semi-major axis and the eccentricity of the inner binary, respectively. It shows that the radiation power increases rapidly as the eccentricity increases. The total radiation power P is the sum of the power radiated in the nth harmonic

, given as

where the

is the power due to the

nth harmonic. The peak of the spectrum

is given by

where

is the orbital frequency of the inner binary and

is the magnification factor, which represents the number of harmonics. This factor can be approximated, in the range

[

6,

8], to

We can see that if eccentricity

,

, describing the peak frequency of GWs from a circular orbit, whereas for high eccentricities,

is very high and would be in the detectable range of the detector (

Hz to 10kHz). Also, since the signal from a highly eccentric orbit consists many harmonics, the signal has a broad spectrum of frequencies. We also check the strain of the wave at the

nth harmonic, given by

where

is the frequency of

nth harmonic,

D is the distance of the source. At

, we can approximate the equation and express in scaled form as

For

,

which is highly detectable in our present and future detectors. Eccentric binaries are highly efficient GW emitters and hence appear at lower frequencies compared to circular orbits. These kinds of eccentric systems must dominate the detections compared to circular orbit system but due to the circularization of the eccentric orbit by GW emission, by the time of merger, the orbit has almost completely circularized, causing it to appear in the LVK band as a binary in a circular orbit. Some residual eccentricity may remain, but has a very negligible effect on the signal.

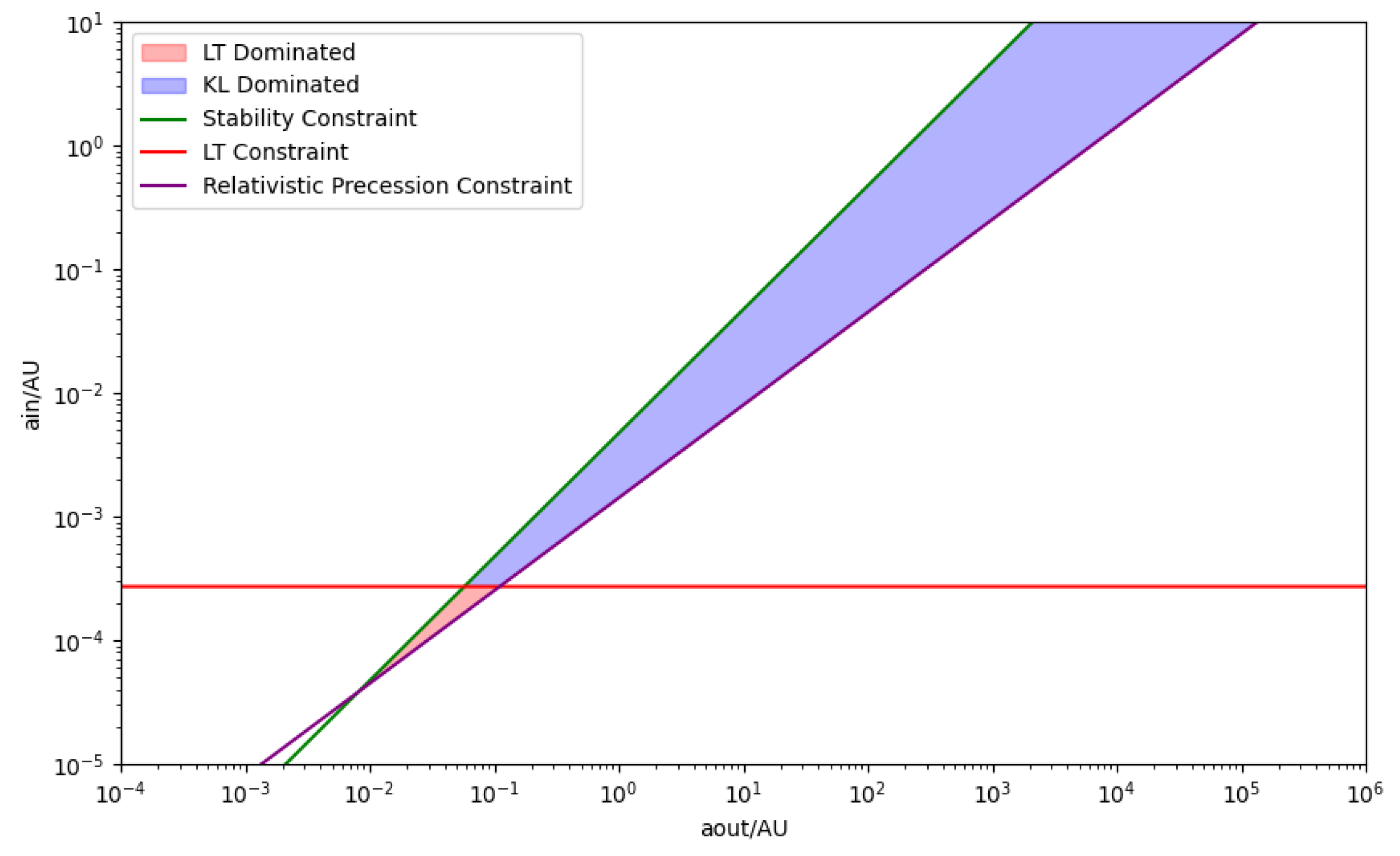

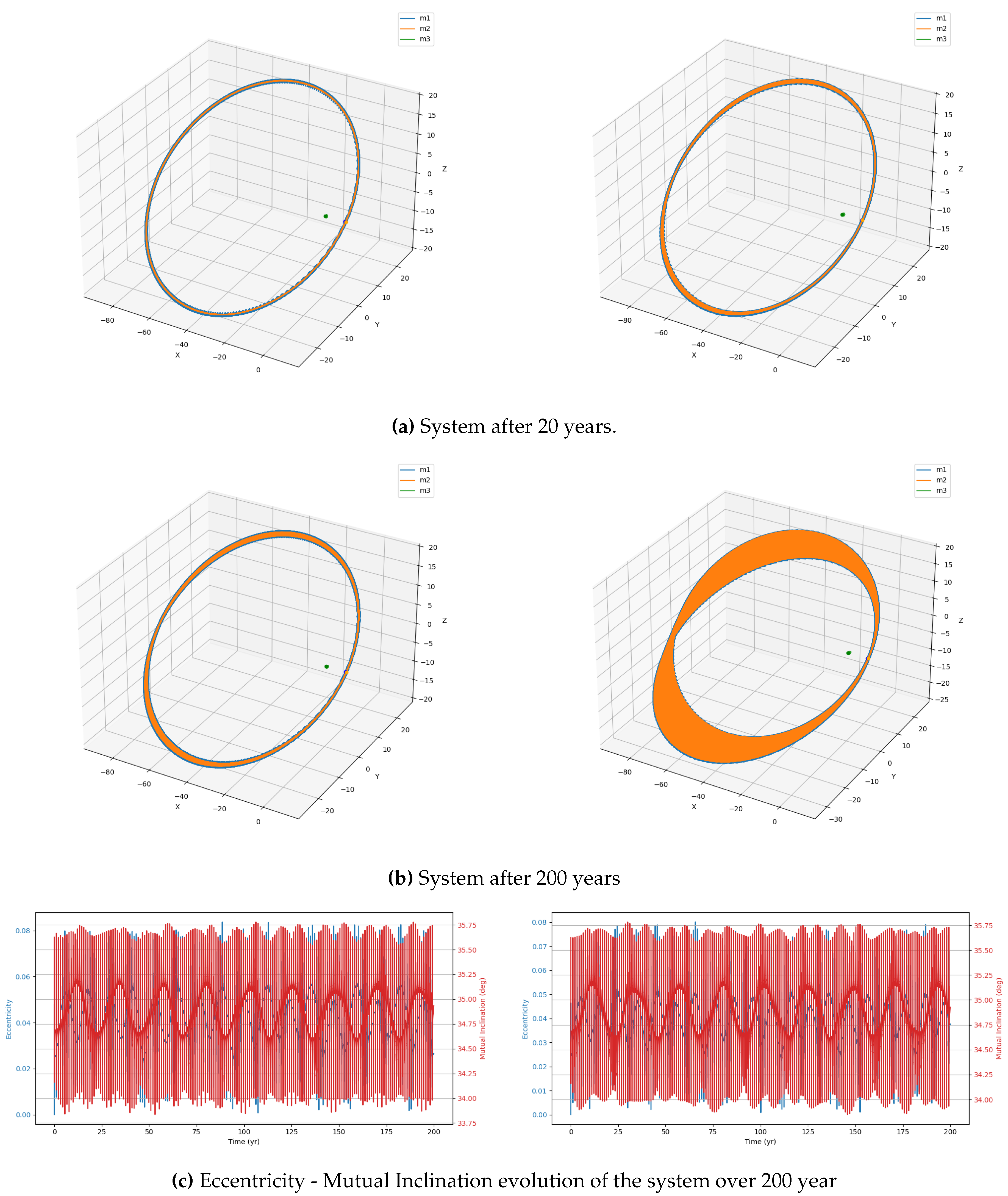

The formation of eccentric orbits can result from dynamical interactions with multiple bodies, particularly through the Kozai-Lidov (KL) mechanism in hierarchical triple systems (HTSs). The KL mechanism [

9,

10], independently identified by Yoshihide Kozai and Mikhail Lidov in the 1960s, occurs when a tertiary companion perturbs an inner binary, causing periodic exchanges between its eccentricity and inclination over timescales much longer than the orbital period. This interplay produces long-term modulations in both the inner binary’s eccentricity and the angular displacement between the inner and outer binaries.

Analytically, the Hamiltonian of a hierarchical triple system can be decomposed into contributions from the inner and outer binaries, along with a term representing their mutual interaction [

11]:

This decomposition allows separate treatment of the inner and outer binary evolutions while capturing the essential perturbative effects that drive KL oscillations.

In the context of gravitational-wave (GW) astrophysics, the KL mechanism is significant because it can maintain high eccentricities (

) for binaries entering the LIGO detection range, which may accelerate merger times. Simulations suggest that a substantial fraction of binaries in dense stellar environments are influenced by third-body perturbations, making accurate modeling of their dynamics essential. This requires integrating third-body interactions along with post-Newtonian relativistic corrections [

11], especially when predicting merger rates of eccentric binaries.

A fundamental assumption in this configuration is that the tertiary’s gravitational influence on the inner binary is weaker than the interaction between the two inner bodies. In a simple two-body Newtonian system, a bound orbit is elliptical and characterized by six orbital elements (

). In hierarchical triples, perturbations from the tertiary lead to deviations from these idealized ellipses, affecting both the inner binary’s orbital shape and orientation over time [

6].

To account for these perturbations, the concept of an osculating orbit [

12] is introduced, providing an approximate trajectory that can be described by an elliptical path defined by the aforementioned six orbital elements, derived from the system’s instantaneous position and velocity at any given moment. As for the outer orbit, this is considered as the motion of the inner binary’s center of mass as it rotates around the tertiary companion, which can also be represented as another osculating orbit. In this framework, the masses of the inner binary components are denoted

and

, while the tertiary companion has a mass

. To distinguish between the inner and outer orbits, subscripts "in" and "out" are used respectively. In such systems, the orbital periods of the inner and outer binary is given by

At a particular relative inclination

I, a secular change of orbital elements may occur where under certain conditions, an oscillation between the values of the eccentricity and relative inclination occurs with the relative equation defined as the argument between the inner and outer orbital planes [

9,

10] and is given by

which results in the secular exchange of

and

I with the conserved value [

13] of

with the condition for the KL oscillation, provided that

and the outer orbit is circular.

Note that the KL oscillation will occur even if

is not much smaller than

,

. The KL oscillation timescale [

14] is given by

When modeling an HTS system, we must also consider the general relativistic precession in the system and the Lense-Thirring, (LT) effect, which is a general relativistic correction to the precession of a gyroscope in the presence of a large rotating mass. This causes the relative orbital nodes of the gyroscope to precess[

15]. Recent studies have shown changes in KL oscillations caused due to GR effects involving a SMBH. If the third body is a rapidly rotating SMBH, then LT effect might become important in changing the evolution of eccentricity excitation from the usual KL oscillation. The effect appears in the 1.5PN order [

16,

17,

18]. For a rotating black hole, the spin angular momentum [

6,

16,

18] is given as

, where

is the spin parameter, and the outer orbital angular momentum [

16,

18] is given as

where

M is the total mass of the gyroscope and the reduced mass of the outer orbit is defined by

The timescale of the orbit-averaged precession of

around

[

16,

18] is given by

This study focuses on developing a more accurate model for GW emission from HTSs by conducting a preliminary study on the detectability of such systems in our present and future detectors and providing a theoretical framework for the evolution of the system and modeling the GWs.

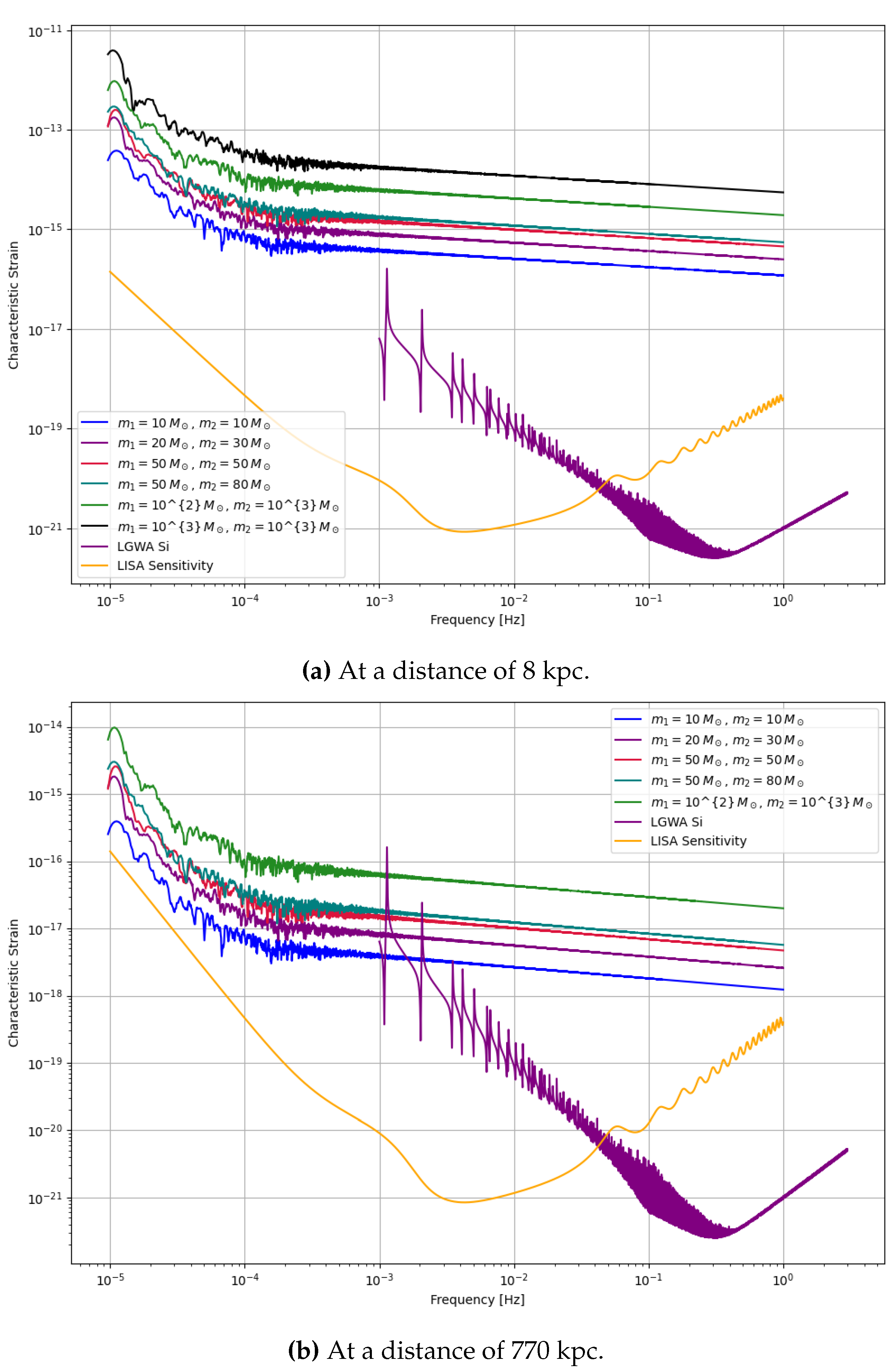

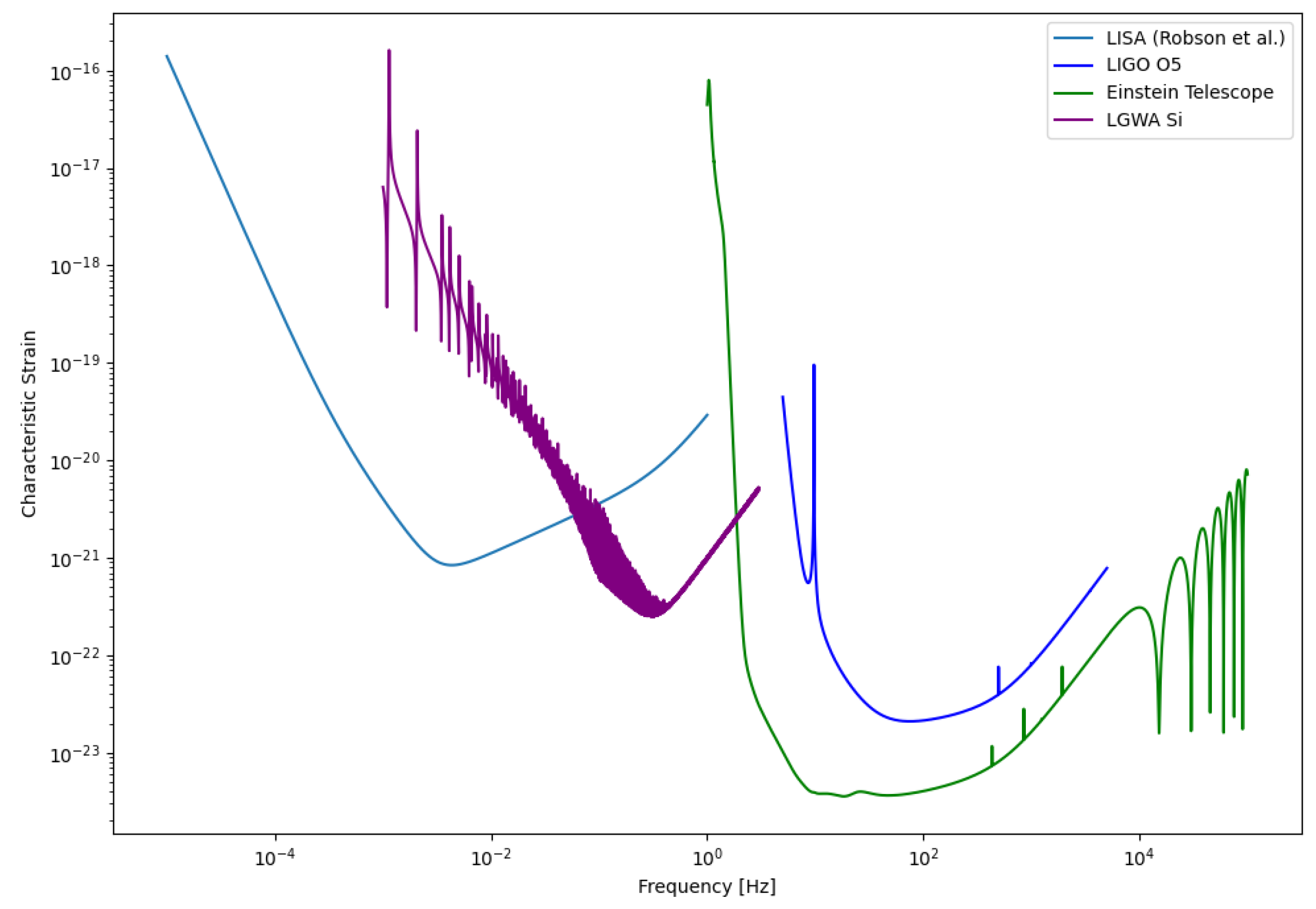

3. Detectability of HTS Through GWs

The noise curves of detectors play a crucial role in determining the detectability of various sources. These curves illustrate the sensitivity of the detector across different frequency ranges, providing valuable insights into its performance. To obtain these noise curves, we analyze noise measurements collected by sensors in the time domain. By performing a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on this data, we can calculate the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the noise. Alternatively, an analytical equation for the noise specific to the detector can also be employed. For our purposes, the analytical noise proves to be sufficient, allowing us to effectively assess the detector’s capabilities.

3.1. LISA

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) [

24] is an ambitious gravitational wave observatory set to be launched by the European Space Agency (ESA), with participation from NASA, targeting an operational period in the 2030s. Unlike ground-based detectors like LIGO and Virgo, LISA will operate in space, allowing it to detect GWs at much lower frequencies. It comprises three spacecraft arranged in an equilateral triangle with 2.5 million kilometers between each pair [

25]. LISA is designed to capture GWs produced by massive celestial events, such as mergers of supermassive black holes, inspirals of stellar-mass compact objects into supermassive black holes, and potentially signals from the early universe.

LISA’s low-frequency sensitivity opens a window to events beyond the reach of current ground-based interferometers. These events can reveal crucial insights into galaxy formation, cosmology, and fundamental physics. Orbiting the Sun in tandem with Earth, LISA’s constellation will effectively remove terrestrial noise sources, providing a pristine environment for GW detection. The data from LISA will complement observations from high-frequency detectors on Earth, expanding our understanding of the universe through multi-frequency GW astronomy. The sensitivity curve for LISA [

25] is given by

where

is the power spectral density of the noise, and

is the response function of the detector.

Here,

is given by,

where

is the single optical metrological noise, and

is the single test mass acceleration noise.

And, the response function

is given by,

Thus, the sensitivity curve

is

where

and

.

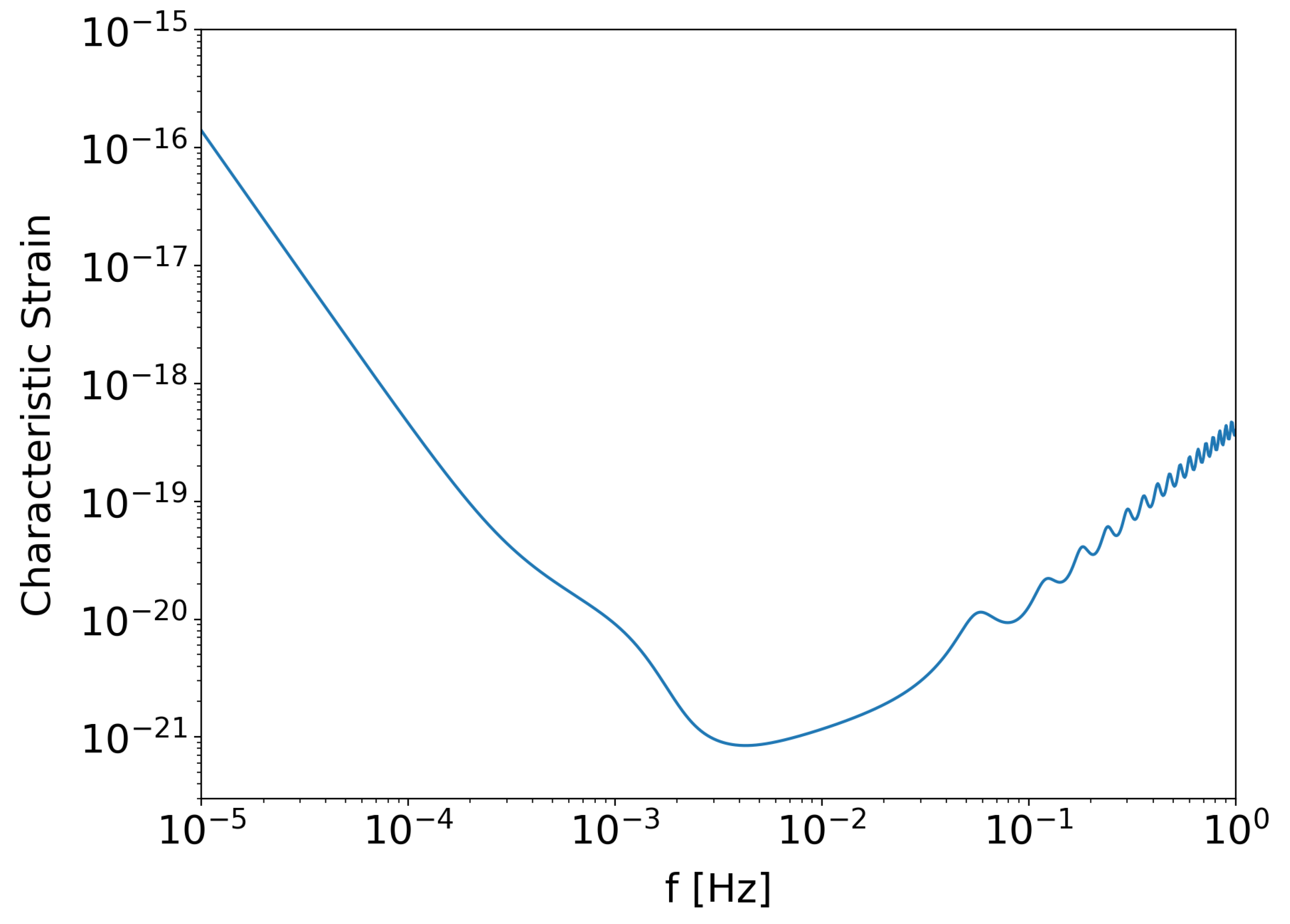

Figure 2.

Sensitivity curve of the LISA detector.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity curve of the LISA detector.

3.2. LGWA

The Lunar Gravitational-wave Antenna (LGWA) is a pioneering gravitational-wave observatory proposed for deployment on the Moon. Unlike space-based interferometers such as LISA, LGWA utilizes the Moon itself as a giant solid-state antenna for detecting GWs (GWs). The mission concept involves an array of high-precision inertial sensors—Lunar Inertial Gravitational-wave Sensors (LIGS)—deployed in permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) at the lunar poles, where seismic noise is minimal and thermal conditions are extremely stable [

5].

LGWA is designed to be sensitive in the decihertz frequency band, spanning from about 1 mHz to 1 Hz. This band bridges the gap between the millihertz sensitivity range of space-based detectors like LISA and the hertz–kilohertz range of ground-based detectors such as the Einstein Telescope and Cosmic Explorer. The lunar environment—with its cryogenic temperatures, lack of atmosphere, and seismic quietness—provides a uniquely favorable platform for low-frequency GW detection that cannot be achieved on Earth.

Through its novel detection mechanism, LGWA is expected to observe GWs from a wide range of astrophysical and cosmological sources. These include inspirals and mergers of intermediate-mass black hole binaries, binary white dwarf systems, and potentially the early inspiral phases of binary neutron stars and stellar-origin black holes, enabling early warnings for electromagnetic follow-up. LGWA also holds promise for detecting unmodeled transients such as tidal disruptions of white dwarfs, and constraining the cosmological stochastic GW background.

Unlike traditional interferometers, LGWA measures the Moon’s elastic response to passing GWs. Its sensitivity is characterized by the displacement noise of its inertial sensors and the Moon’s GW response function.

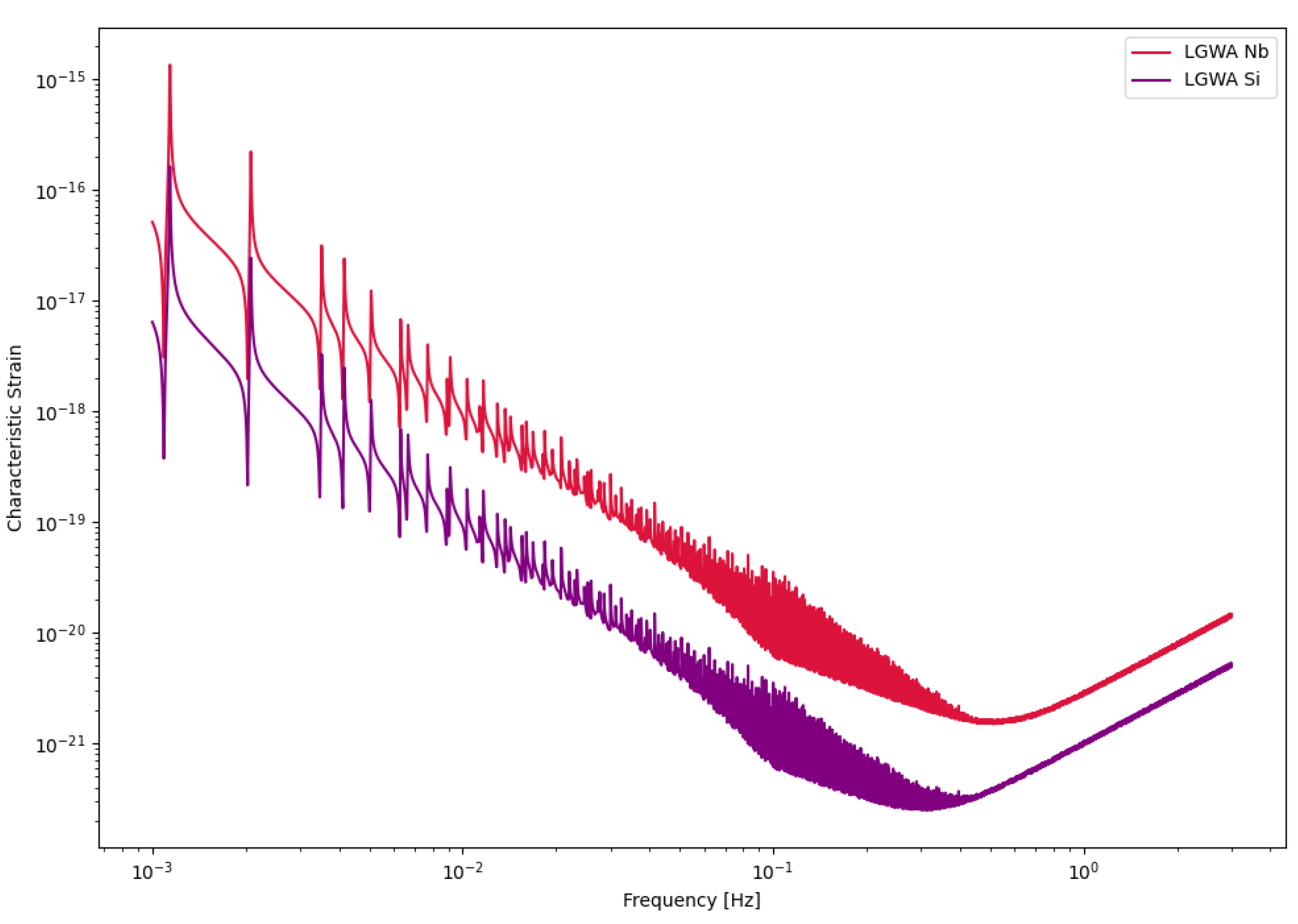

Figure 3.

Sensitivity curves of the LGWA detector.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity curves of the LGWA detector.

3.3. EccentricFD

EccentricFD is a frequency-domain waveform model implemented in the PyCBC library for simulating gravitational wave (GW) signals from eccentric binary systems. Unlike traditional quasi-circular approximants,

EccentricFD includes the effects of non-zero eccentricity at leading-order post-Newtonian (PN) accuracy, enabling the modeling of binaries formed through dynamical capture, globular cluster interactions, or hierarchical triple-induced Kozai–Lidov oscillations. These systems may retain measurable eccentricities within the LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA frequency band, and waveform models such as

EccentricFD are crucial for their detection and characterization [

26,

27,

28]. The model is computationally efficient due to its frequency-domain implementation and is widely used for injection studies and parameter estimation in the analysis of non-circular compact binary coalescences.

The construction of the

EccentricFD model is based on the stationary phase approximation, where the waveform is expressed as a sum over harmonics of the orbital frequency. The amplitude and phase of each harmonic are modified by the orbital eccentricity, which is specified at a reference frequency, typically 10 Hz. The model incorporates post-Newtonian corrections up to 3PN order in the binary’s orbital energy and gravitational wave flux. It takes as input the component masses, reference eccentricity, and luminosity distance, and returns the frequency-domain plus and cross polarizations [

27,

28].

This waveform model is used to get the frequency-domain waveform of the inner binaries from our various models and are then plotted onto the sensitivity curves of LISA and LGWA to identify whether the signal will be detectable in the detector. However, since we do not have access to the waveform response of LISA and LGWA, these plots just provide us the rough estimates of their detectability.

5. Conclusion

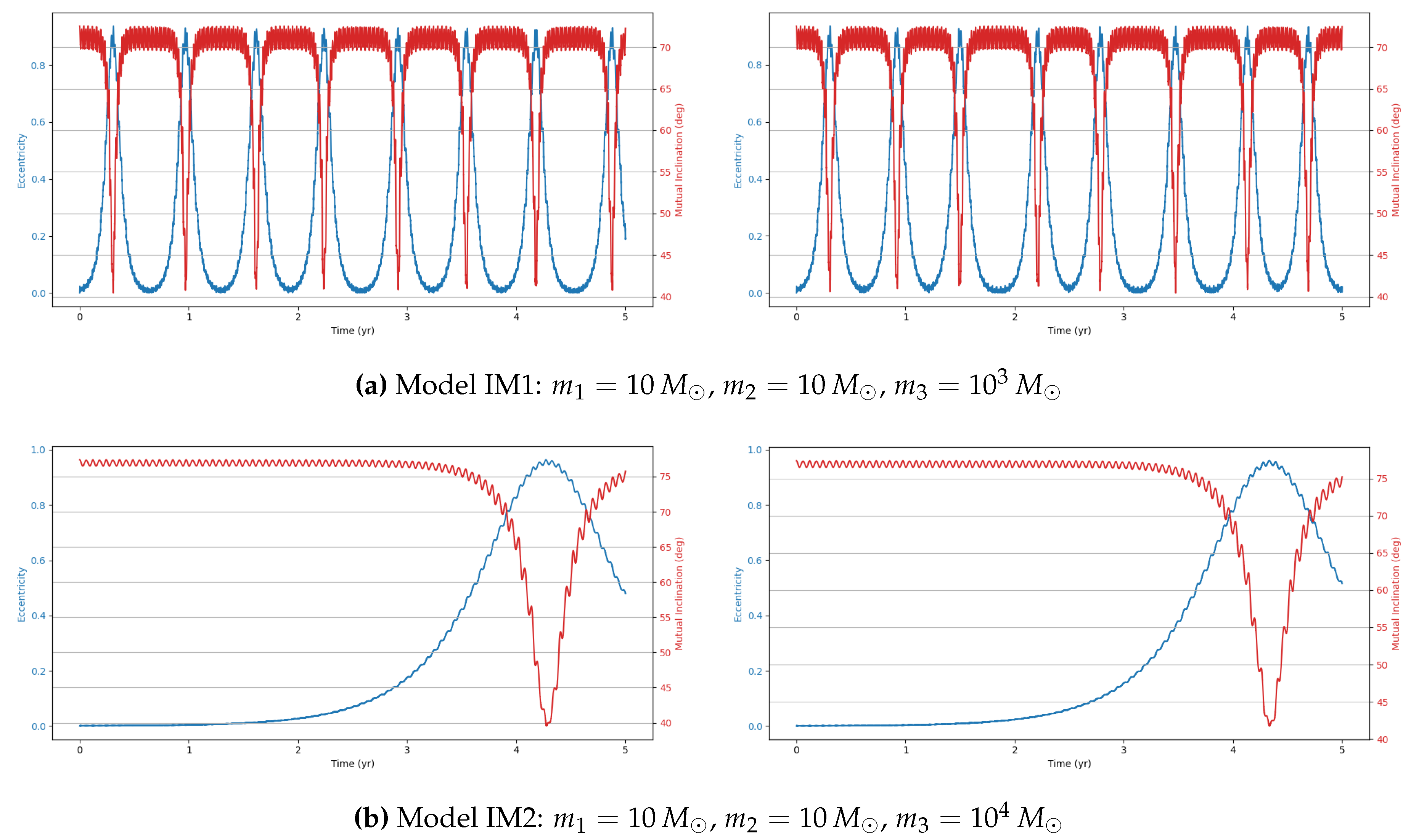

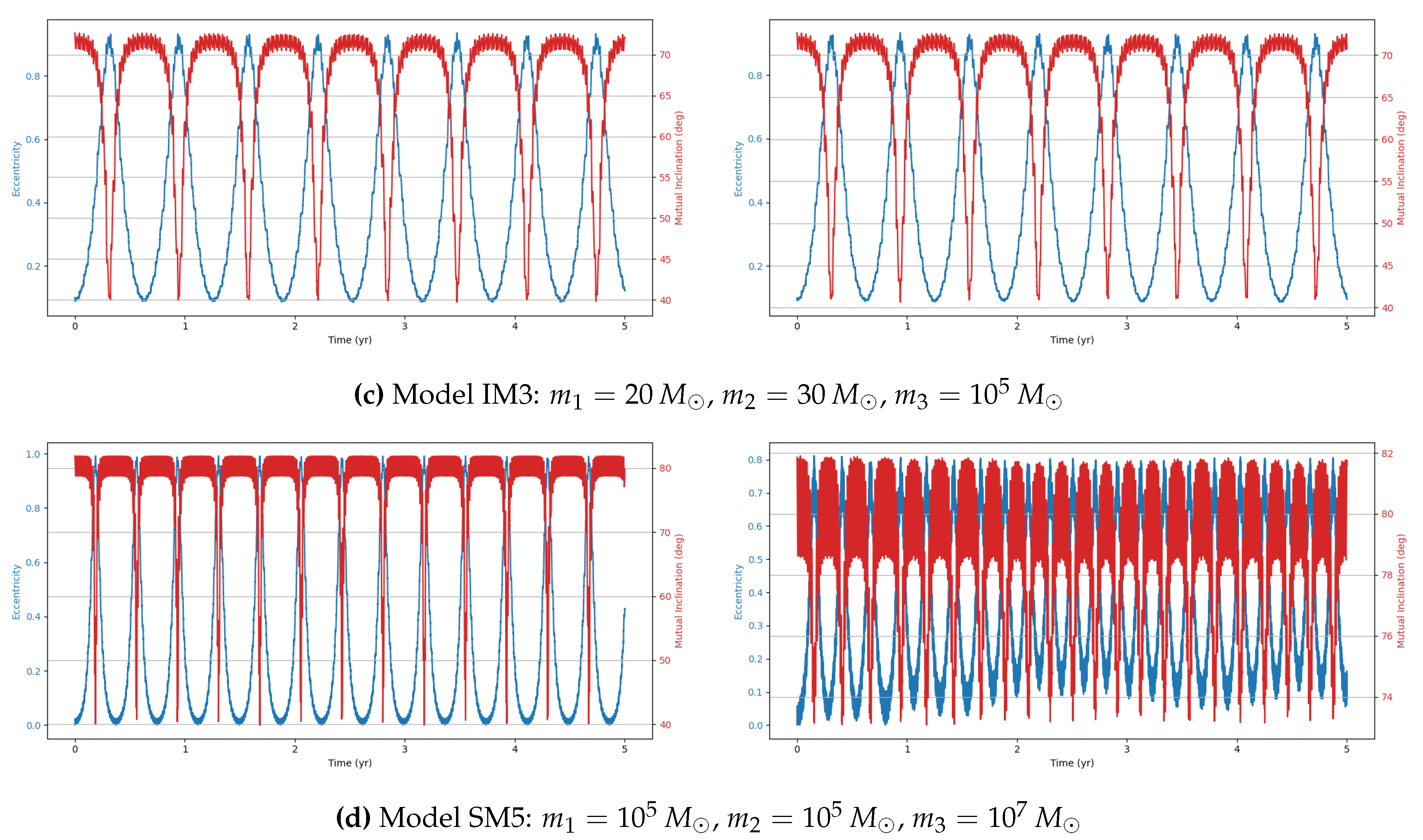

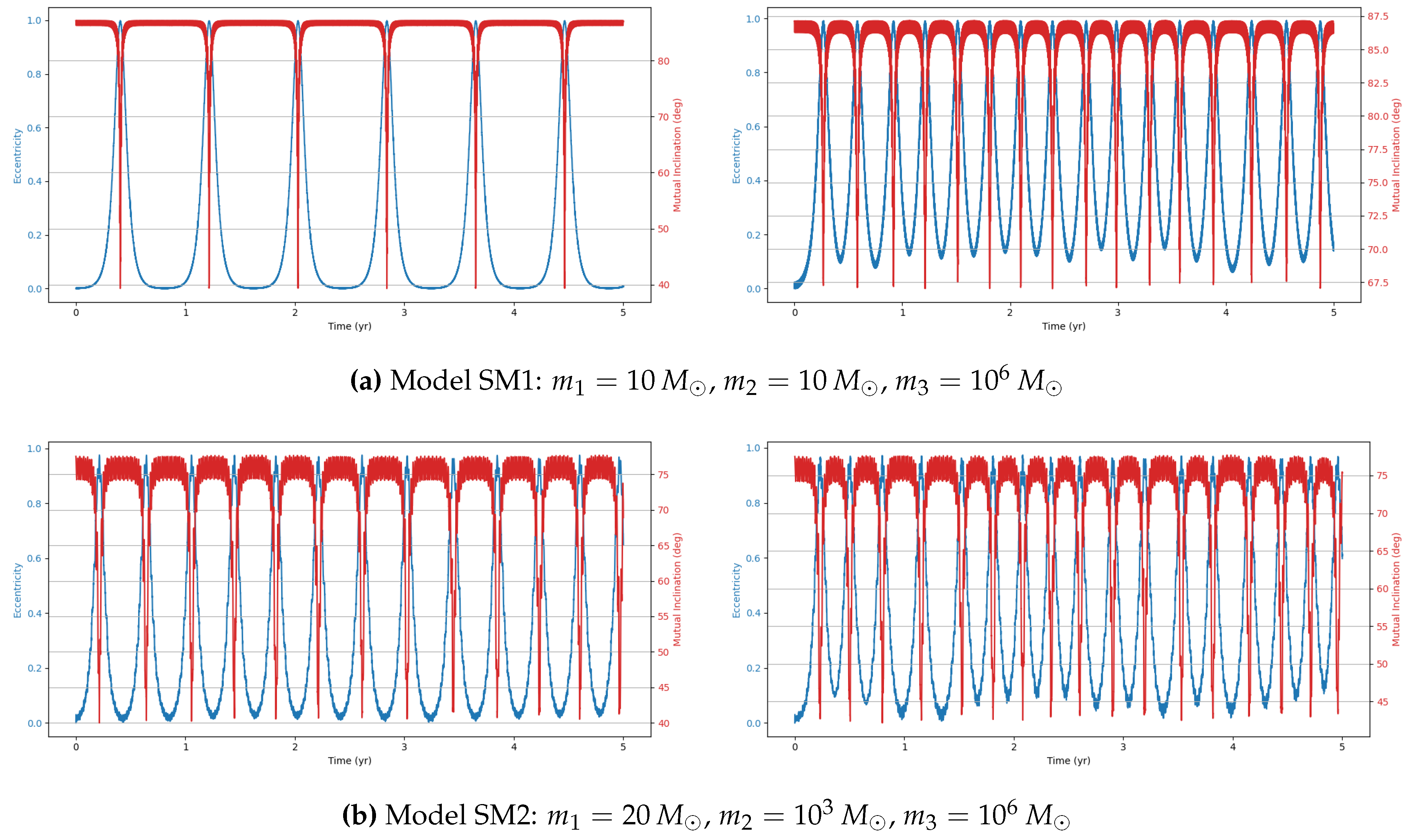

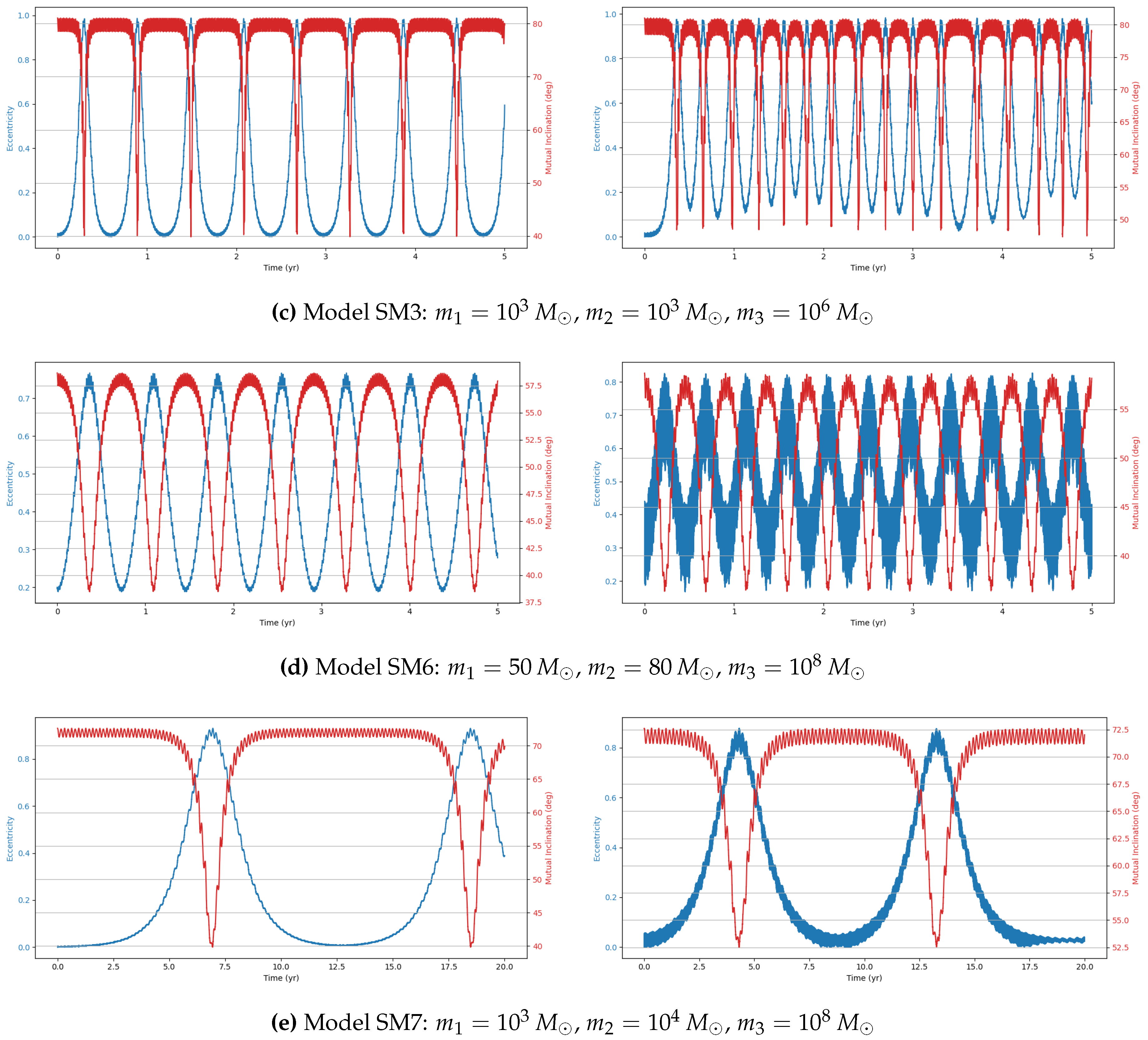

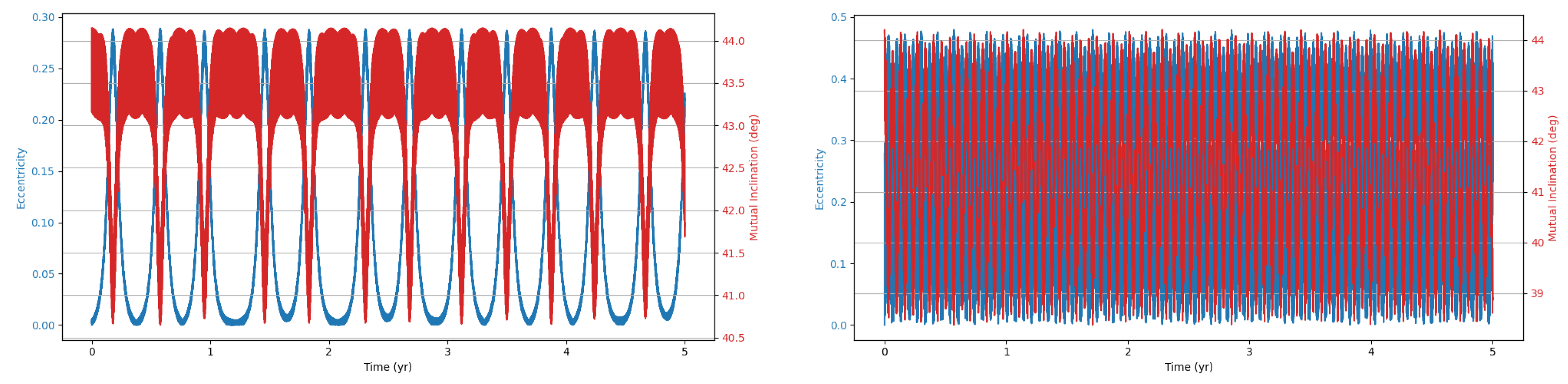

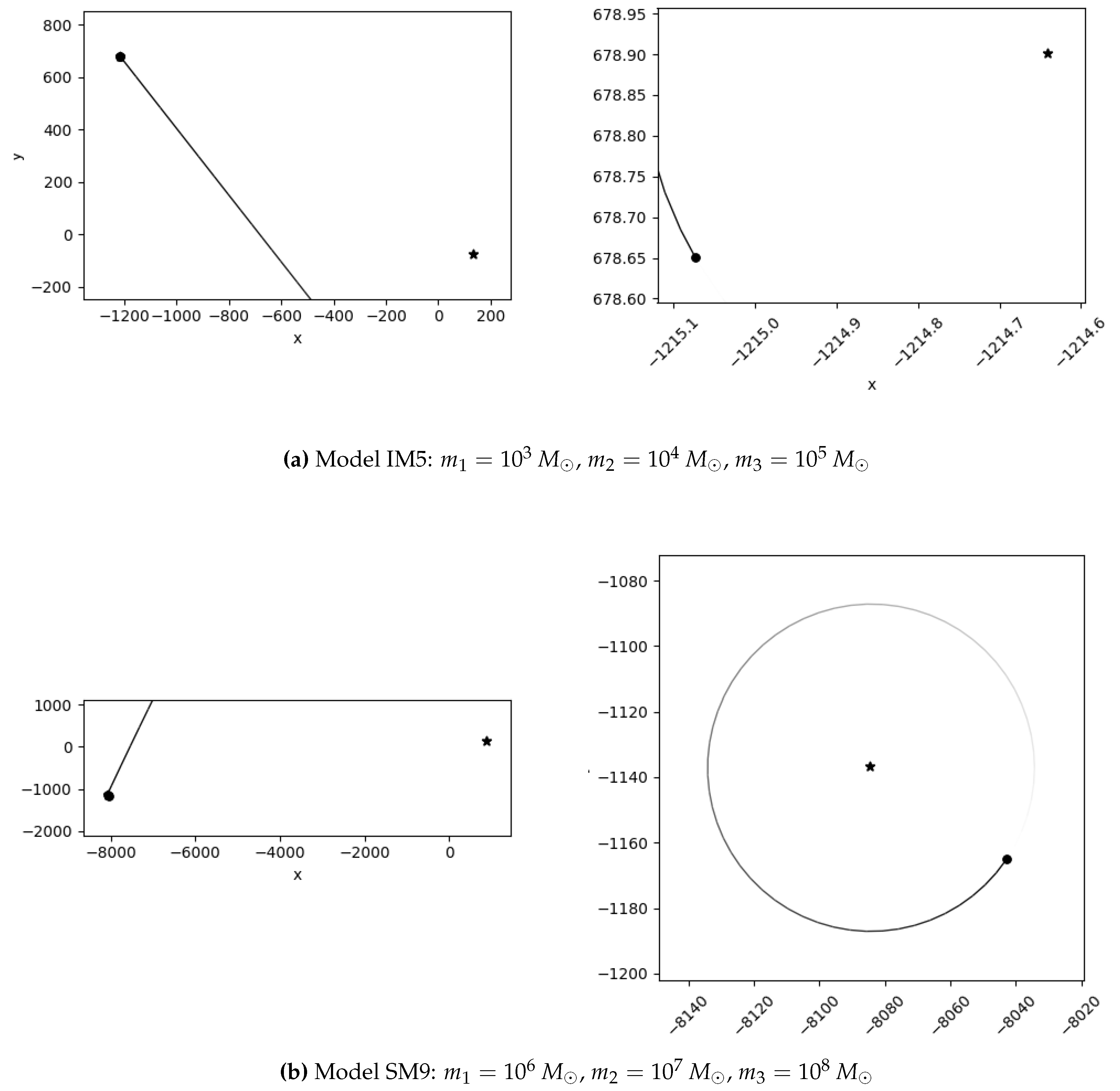

This study investigates the dynamical evolution of hierarchical triple systems (HTSs) and evaluates their gravitational wave (GW) detectability through numerical simulations. By selecting models from astrophysically relevant parameter spaces and implementing them using REBOUND and REBOUNDx, we confirm the occurrence of KL oscillations and examine the competing influence of general relativistic (GR) precession. Our results highlight the importance of including post-Newtonian corrections, as GR precession can significantly modulate both the timescales and amplitude of KL-driven eccentricity growth. Interestingly, despite choosing initial parameters expected to yield stable HTSs displaying KL oscillations, our simulations reveal both stable and unstable systems.

Within the stable systems, two distinct behaviors emerge: systems exhibiting KL oscillations and systems that do not. For systems showing KL oscillations, the impact of including 1PN dynamics increases with the tertiary mass, particularly in the supermassive black hole (SMBH) regime, where KL oscillations become more frequent. This effect arises because GR precession can partially restart the KL mechanism even under imposed constraints, though its influence is weak [

11].

We also identify notable outliers in our simulations. A stable system (IM4) does not display KL oscillations, while two unstable systems (IM5 and SM9) show unexpected chaotic behavior. In these cases, one inner binary mass is an order of magnitude larger than the other, but the tertiary mass differs: in the stable system, it is two orders of magnitude larger, whereas in the unstable systems, it is only one order larger. This suggests the existence of an additional stability constraint dependent on the mass ratios within the HTS. The stable system may lie within this constraint, explaining its stability and absence of KL oscillations, whereas the chaotic systems exceed it. Future work should aim to quantify this constraint to deepen our understanding of HTS stability.

From frequency-domain gravitational waveforms obtained using EccentricFD, we find that highly eccentric binaries driven by KL oscillations can emit GWs detectable by both current and future detectors. Specifically, LISA is well-suited to capture signals during the high-eccentricity inspiral phase, while aLIGO is more sensitive to the circularized final mergers. Proposed detectors such as LGWA, with a frequency band bridging LISA and LIGO, alongside the Einstein Telescope (ET), could identify residual eccentricity in these systems. This multi-band detectability underscores the potential for HTS-originating binaries to serve as complementary probes across a wide range of GW frequencies.

We acknowledge that our simulations of hierarchical triple systems (HTSs) are idealized and do not capture all physical effects present in realistic astrophysical environments. Additionally, the gravitational waveform curves presented here do not incorporate the detector response functions, and thus do not reflect how these signals would appear in actual observational data. Nevertheless, this study provides a foundational framework for constructing more sophisticated gravitational wave (GW) templates that include complex three-body dynamics and relativistic corrections. Ongoing development of our HTS code is aimed at incorporating higher-order PN terms, up to at least 2.5PN, to better understand the interplay between KL oscillations, GW emission, and other secular effects. These improvements will ultimately support the generation of more accurate, time-evolving GW waveforms for inner binaries embedded in hierarchical triple systems.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were stored or separately generated during the study. All data were produced and utilized in real-time within the simulation code for analysis and were not saved externally.

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

All authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.