Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

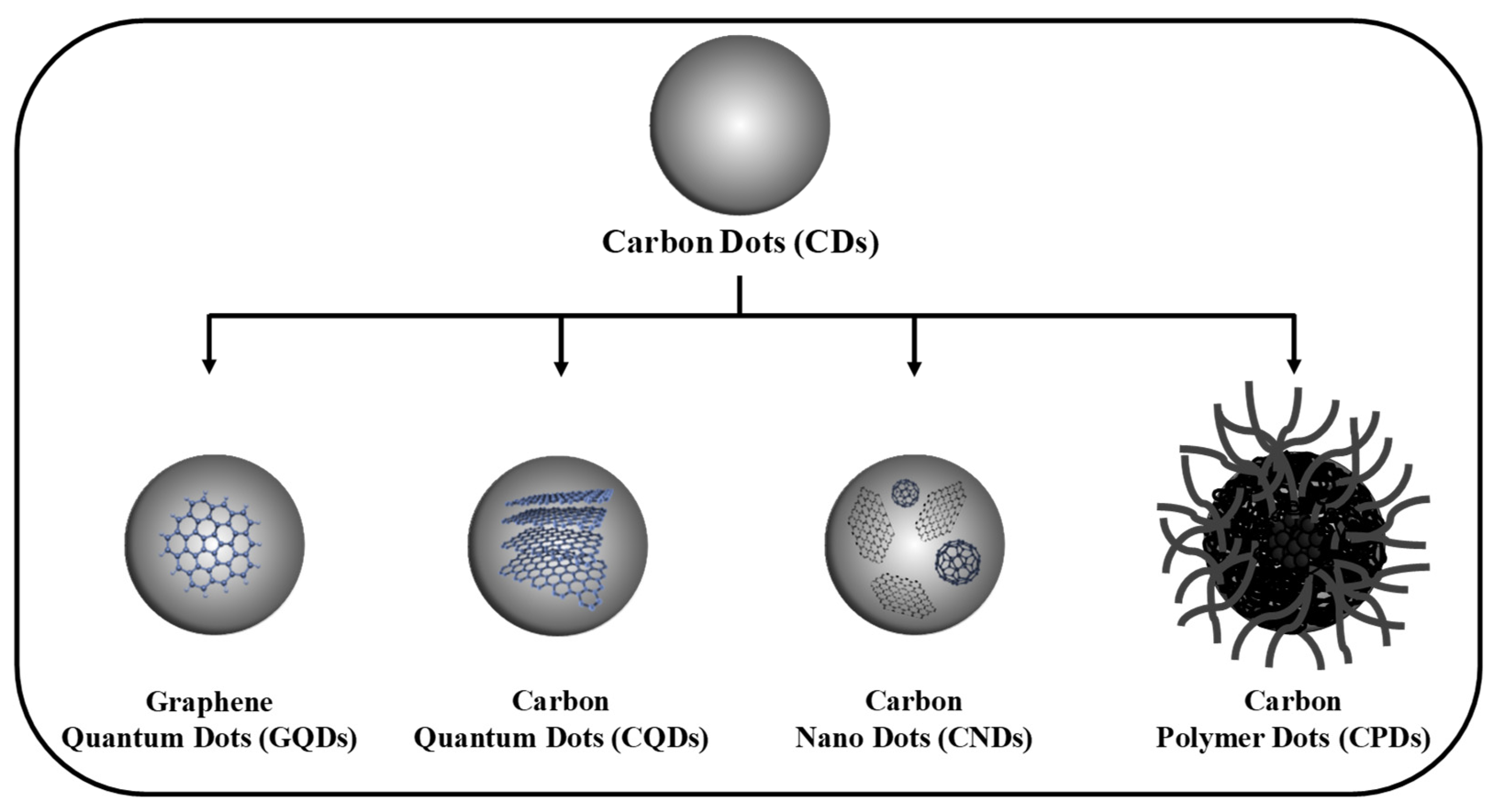

1. Introduction

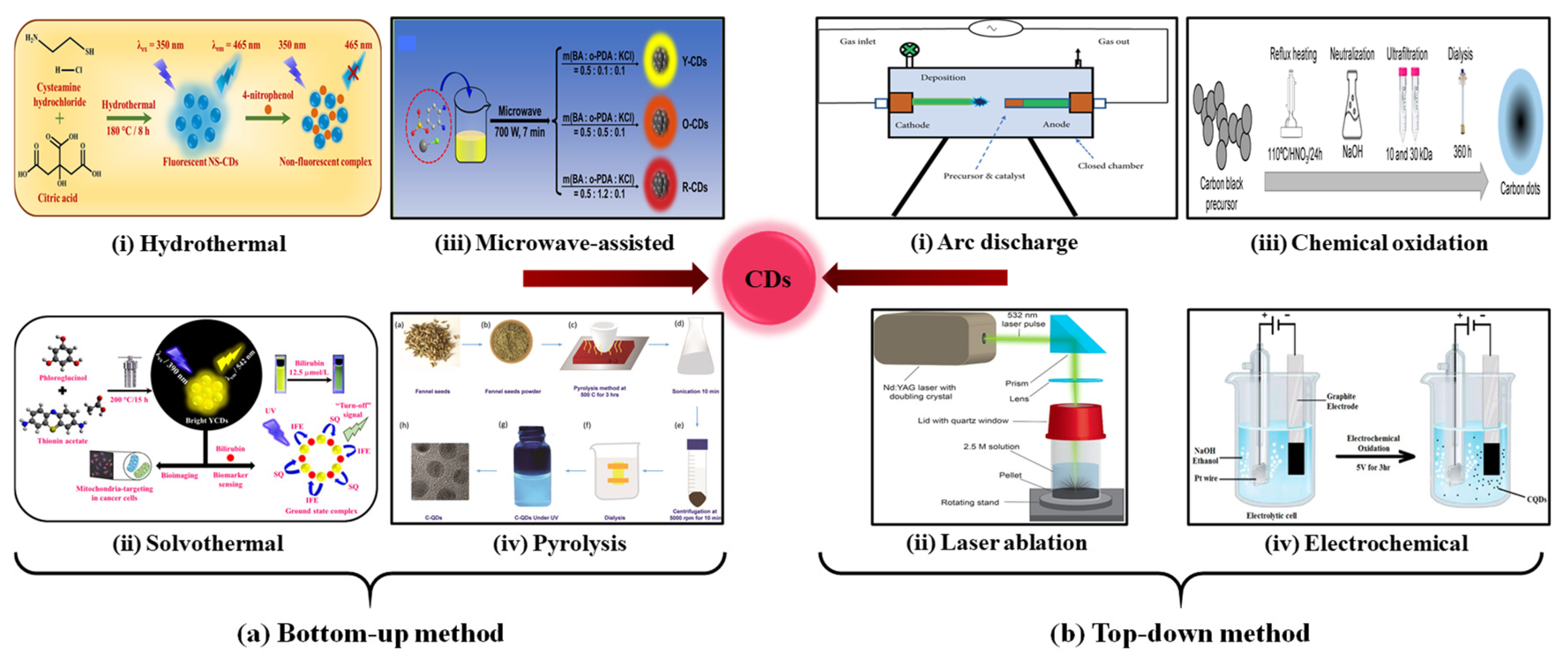

2. Synthesis Strategies of CDs

2.1. Bottom-Up Method

2.1.1. Hydrothermal/Solvothermal

2.1.2. Microwave Method

2.1.3. Pyrolysis

2.2. Top-Down Method

2.2.1. Arc Discharge

2.2.2. Laser Ablation

2.2.3. Chemical Oxidation

2.2.4. Electrochemical

3. Applications of Carbon Dots in Optical Fiber Sensors

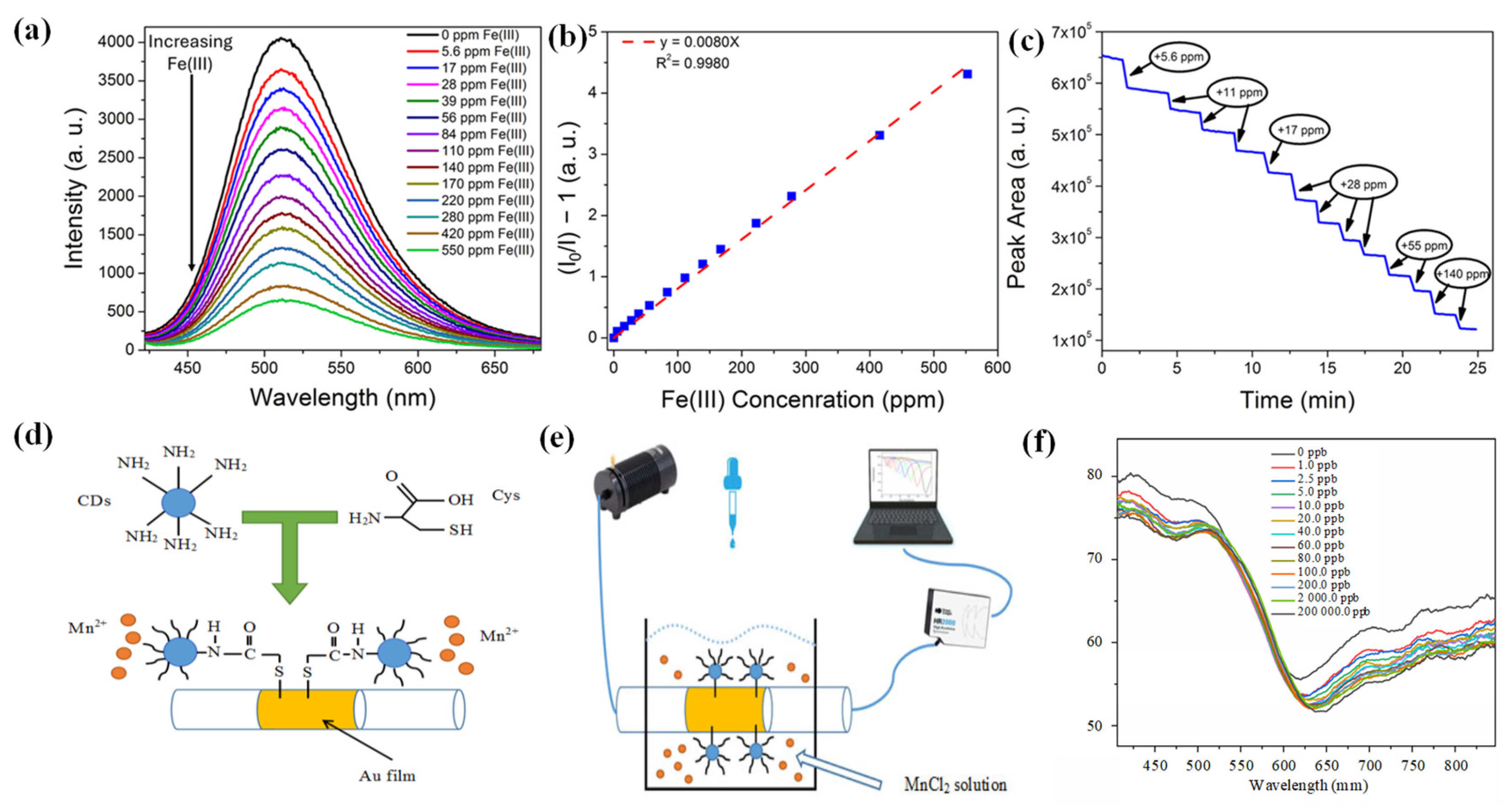

3.1. Carbon Dots for Metal Ion Sensing

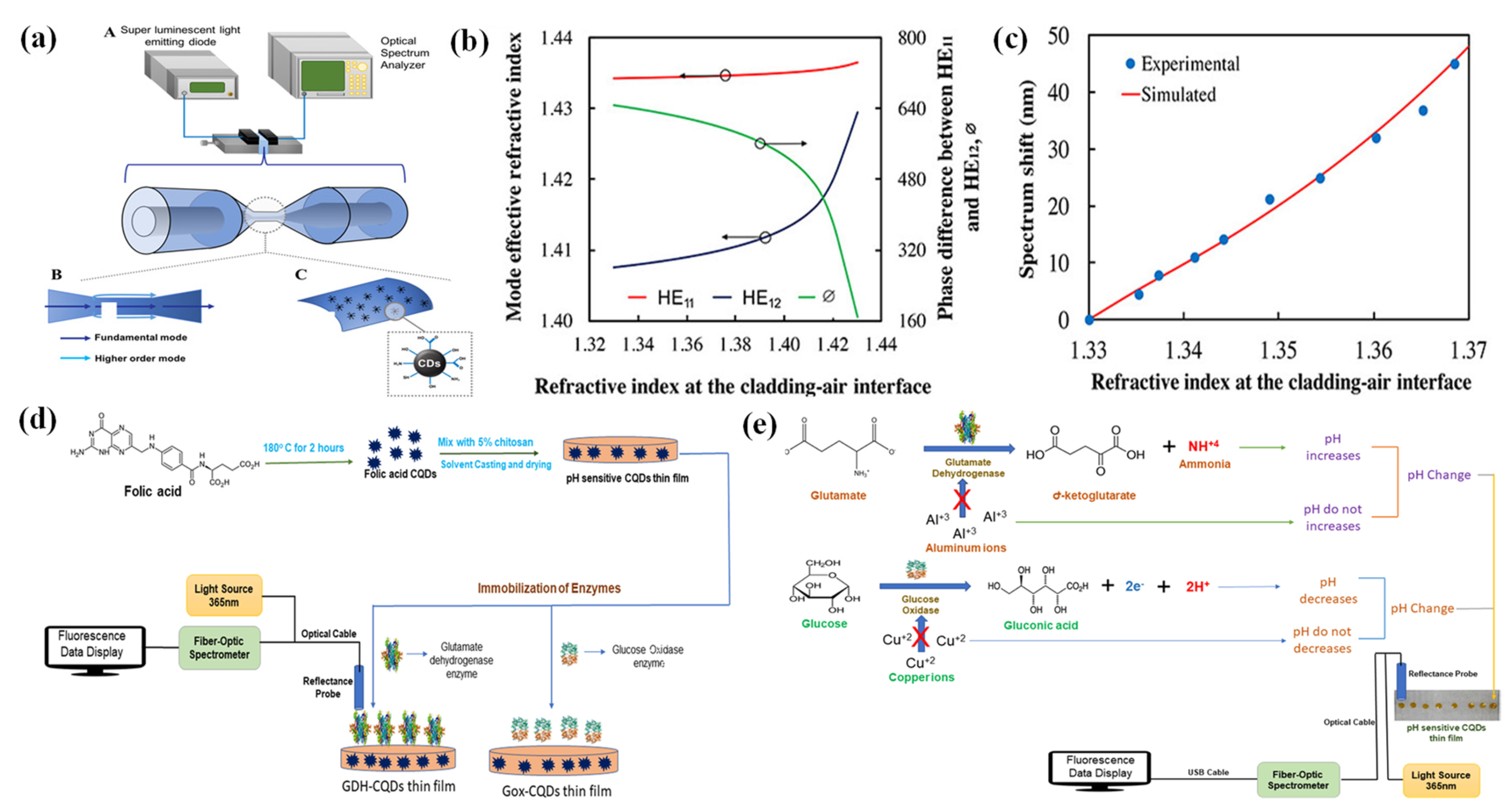

3.2. Carbon Dots for Biomarker Sensing

3.3. Carbon Dots for Other Targets

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Lone, I.A.; Rohit, J.V. Carbon dots encapsulated metal-organic frameworks: An emerging optical sensors for monitoring of environmental pollutants. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2025, 114918. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhu, S.; Feng, T.; Yang, M.; Yang, B. Evolution and synthesis of carbon dots: From carbon dots to carbonized polymer dots. Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1901316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falara, P.P.; Zourou, A.; Kordatos, K.V. Recent advances in Carbon Dots/2-D hybrid materials. Carbon 2022, 195, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhari, O.; Ntuli, T.D.; Coville, N.J.; Nxumalo, E.N.; Maubane-Nkadimeng, M.S. Supported carbon-dots: A review. Journal of Luminescence 2023, 255, 119552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.B.; Liu, M.L.; Li, C.M.; Huang, C.Z. Fluorescent carbon dots functionalization. Advances in colloid and interface science 2019, 270, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parani, S.; Choi, E.Y.; Oluwafemi, O.S.; Song, J.K. Carbon dot engineered membranes for separation–a comprehensive review and current challenges. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2023, 11, 23683–23719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lin, X.; Liao, J.; Yang, M.; Jiang, M.; Huang, Y.; Du, Z.; Chen, L.; Fan, S.; Huang, Q. Carbon dots-based dopamine sensors: Recent advances and challenges. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 35, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Lu, X.; Sun, Z.; Guo, Y.; He, H. A review on syntheses, properties, characterization and bioanalytical applications of fluorescent carbon dots. Microchimica Acta 2016, 183, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Shen, W.; Gao, Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2015, 44, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, K.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Ju, H. Nitrogen-and sulfur-codoped strong green fluorescent carbon dots for the highly specific quantification of quercetin in food samples. Materials 2023, 16, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Hong, S.; Ju, H. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, characteristics, and quenching as biocompatible fluorescent probes. Biosensors 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Lu, S. Carbon dot based multicolor electroluminescent LEDs with nearly 100% exciton utilization efficiency. Nano Letters 2023, 23, 8794–8800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanikandan, R.; Prabakaran, D.S.; Sasikumar, K.; Seok, J.S.; Lee, G.; Ju, H. Biocompatible bright orange emissive carbon dots: Multifunctional nanoprobes for highly specific sensing toxic Cr(VI) ions and mitochondrial targeting cancer cell imaging. Talanta Open 2024, 10, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhenadhayalan, N.; Lin, K.C.; Saleh, T.A. Recent advances in functionalized carbon dots toward the design of efficient materials for sensing and catalysis applications. Small 2020, 16, 1905767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkowski, M.; Zhou, Y.; Nabil Amin Mustafa, M.; Eustace, A.J.; Giordani, S. CARBON DOTS: Bioimaging and anticancer drug delivery. Chemistry–A European Journal 2024, 30, e202303982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasikumar, K.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Ju, H. Bright green fluorescent carbon dots: Smartphone-assisted sensing platform for arsenic detection in water and mitochondrial-targeted imaging. Microchemical Journal 2025, 115309. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, R.; Gong, X.; Dong, C. An efficient turn-on fluorescence biosensor for the detection of glutathione based on FRET between N, S dual-doped carbon dots and gold nanoparticles. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2019, 411, 6687–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Bu, T.; Sun, X.; Jia, P.; Wang, L. Nitrogen, silicon co-doped carbon dots as the fluorescence nanoprobe for trace p-nitrophenol detection based on inner filter effect. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2021, 244, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yu, D.; Qin, W.; Wu, X. Ultra-sensitive and stable N-doped carbon dots for selective detection of uranium through electron transfer induced UO2+(V) sensing mechanism. Carbon 2022, 198, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yu, H.; Bui, B.; Wang, L.; Xing, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.; Hu, Z.; Chen, W. Nitrogen-doped fluorescence carbon dots as multi-mechanism detection for iodide and curcumin in biological and food samples. Bioactive materials 2021, 6, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Pourasl, M.H.; Tajalli, H.; Khalilzadeh, B.; Isildak, I. Advances in biosensors for wastewater quality assessment. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2025, 195, 118622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Kaja, S.; Nag, A. Red-emitting carbon dots as a dual sensor for In3+ and Pd2+ in water. ACS omega 2020, 5, 8362–8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhuang, J.; Wei, G. Recent advances in the design of colorimetric sensors for environmental monitoring. Environmental Science: Nano 2020, 7, 2195–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Sahoo, D.; Sarkar, P.; Chakraborty, K.; Das, S. Fluorescence turn-on and turn-off sensing of pesticides by carbon dot-based sensor. New Journal of Chemistry 2019, 43, 12137–12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgaparameshwari, M.; Kaviya, K.; Prabakaran, D.S.; Santhamoorthy, M.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Mani, K.S. Designing a Simple Quinoline-Based Chromo-Fluorogenic Receptor for Highly Specific Quantification of Copper (II) Ions: Environmental and Bioimaging Applications. Luminescence 2024, 39, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeque, M.S.B.; Chowdhury, H.K.; Rafique, M.; Durmuş, M.A.; Ahmed, M.K.; Hasan, M.M.; Erbaş, A.; Sarpkaya, İ.; Inci, F.; Ordu, M. Hydrogel-integrated optical fiber sensors and their applications: A comprehensive review. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2023, 11, 9383–9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.T.; Kim, J.; Phan, T.B.; Khym, S.; Ju, H. Label-free optical biochemical sensors via liquid-cladding-induced modulation of waveguide modes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 31478–31487. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V.T.; Yoon, W.J.; Lee, J.H.; Ju, H. DNA sequence-induced modulation of bimetallic surface plasmons in optical fibers for sub-ppq (parts-per-quadrillion) detection of mercury ions in water. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 23894–23902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Li, H.; Hu, T.; Wei, L.; Qu, Y.; Cheng, T. Optical fiber sensors for heavy metal ion sensing. Journal of materials science & technology 2024, 189, 110–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.H.T.; Phan, T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ju, H. Coupling of silver nanoparticle-conjugated fluorescent dyes into optical fiber modes for enhanced signal-to-noise ratio. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 176, 112900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsherif, M.; Salih, A.E.; Muñoz, M.G.; Alam, F.; AlQattan, B.; Antonysamy, D.S.; Zaki, M.F.; Yetisen, A.K.; Park, S.; Wilkinson, T.D.; Butt, H. Optical fiber sensors: Working principle, applications, and limitations. Advanced Photonics Research 2022, 3, 2100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Tsai, Y.T.; Feng, W.K.; Lin, C.L.; Chiang, C.C. U-shaped optical fiber probes coated with electrically doped GQDs for humidity measurements. Polymers 2021, 13, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Duarte, A.J.; da Silva, J.C.E. Optical fiber sensor for Hg(II) based on carbon dots. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2010, 26, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tian, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Yin, X.; Du, Y.; Li, D. An easily fabricated high performance Fabry-Perot optical fiber humidity sensor filled with graphene quantum dots. Sensors 2021, 21, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, T.; Jaiswal, S.; Choudhary, S.; Kodgire, P.; Joshi, A. Recombinant Organophosphorus acid anhydrolase (OPAA) enzyme-carbon quantum dot (CQDs)-immobilized thin film biosensors for the specific detection of Ethyl Paraoxon and Methyl Parathion in water resources. Environmental research 2024, 243, 117855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, N.A.A.; Azeman, N.H.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Mobarak, N.N.; Masran, A.S.; Zain, A.R.M.; Mahdi, M.A.; Saputro, A.G.; Wung, T.D.K.; Luo, Y.; Bakar, A.A.A. Polymeric carbon quantum dots as efficient chlorophyll sensor-analysis based on experimental and computational investigation. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 170, 110259. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Singh, R.; Wang, Y.; Marques, C.; Zhang, B.; Kumar, S. Advances in novel nanomaterial-based optical fiber biosensors—A review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, N.A.A.; Azeman, N.H.; Luo, Y.; Bakar, A.A.A. Carbon quantum dots for optical sensor applications: A review. Optics & Laser Technology 2021, 139, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, K.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Ju, H. Inner filter effect-based highly sensitive quantification of 4-nitrophenol by strong fluorescent N, S co-doped carbon dots. Carbon Letters 2024, 34, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, K.; Prabakaran, D.S.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Ju, H. Yellow Emissive Carbon Dots–A Robust Nanoprobe for Highly Sensitive Quantification of Jaundice Biomarker and Mitochondria Targeting in Cancer Cells. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2024, 7, 6730–6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Jian, K.; Fu, L.; Zhao, X. Rapid preparation of long-wavelength emissive carbon dots for information encryption using the microwave-assisted method. Inorganic Chemistry 2023, 62, 13847–13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dager, A.; Uchida, T.; Maekawa, T.; Tachibana, M. Synthesis and characterization of mono-disperse carbon quantum dots from fennel seeds: Photoluminescence analysis using machine learning. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyancha, R.B.; Ukhurebor, K.E.; Aigbe, U.O.; Osibote, O.A.; Kusuma, H.S.; Darmokoesoemo, H. A methodical review on carbon-based nanomaterials in energy-related applications. Adsorption Science & Technology 2022, 2022, 4438286. [Google Scholar]

- Calabro, R.L.; Yang, D.S.; Kim, D.Y. Controlled nitrogen doping of graphene quantum dots through laser ablation in aqueous solutions for photoluminescence and electrocatalytic applications. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2019, 2, 6948–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, R.B.; González, L.T.; Madou, M.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Martinez-Chapa, S.O.; Mendoza, A. Synthesis, purification, and characterization of carbon dots from non-activated and activated pyrolytic carbon black. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magesh, V.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Ganapathy, D. Recent advances on synthesis and potential applications of carbon quantum dots. Frontiers in materials 2022, 9, 906838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Changotra, R.; Dasog, M.; Selopal, G.S.; Yang, J.; He, Q.S. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis via hydrothermal processing, doping strategies, integration with photocatalysts, and their application in photocatalytic hydrogen production. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2025, 44, e01386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. A Portable Optical Fiber Sensing Platform Based on Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Real-Time pH Detection. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zheng, X.; Lin, L.; Xu, H.; Xu, G. Reaction time-controlled synthesis of multicolor carbon dots for white light-emitting diodes. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 2478–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Yang, M.; Sun, H.; Yang, B. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of nitrogen-doped conjugated carbonized polymer dots with 31% efficient red emission for in vivo imaging. Small 2018, 14, 1703919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yat, Y.D.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Tan, I.S.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, S. Carbon dots and miniaturizing fabrication of portable carbon dot-based devices for bioimaging, biosensing, heavy metal detection and drug delivery applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2022, 10, 15277–15300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ye, F.; Fu, Y. Nanoscale light warriors: A review of carbon dot-based optical sensors for insecticide residue detection in food and ecosystems. Talanta 2026, 296, 128445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Suzuki, R.; Kaneda, Y.; Tanimura, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Tachibana, M. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on plant-seed-derived carbon dots. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2025, 13, 22832–22840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etefa, H.F.; Tessema, A.A.; Dejene, F.B. Carbon dots for future prospects: Synthesis, characterizations and recent applications: A review (2019–2023). C 2024, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, R.; Yukta, Y.; Mondal, J.; Kumar, R.; Pani, B.; Singh, B. Carbon dots: Synthesis, characterizations, and recent advancements in biomedical, optoelectronics, sensing, and catalysis applications. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2024, 7, 2086–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Duarte, A.J.; Davis, F.; Higson, S.P.; da Silva, J.C.E. Layer-by-layer immobilization of carbon dots fluorescent nanomaterials on single optical fiber. Analytica chimica acta 2012, 735, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, M.P.; Pardhiya, S.; Rajamani, P. Carbon dots: An excellent fluorescent probe for contaminant sensing and remediation. Small 2022, 18, 2105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Jeong, Y.K.; Ryu, J.H.; Son, Y.; Kim, W.R.; Lee, B.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, K.M. Pulsed laser ablation based synthetic route for nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots using graphite flakes. Applied Surface Science 2020, 506, 144998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, M.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, W.; Wu, X.; Guo, C. Carbon dots: Synthesis, properties and biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2021, 9, 6553–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; He, J.; Chen, L.; Meng, X.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, L.; Tu, K.; Gao, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Fan, K. Deciphering the catalytic mechanism of superoxide dismutase activity of carbon dot nanozyme. Nature communications 2023, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Travas-Sejdic, J. Simple aqueous solution route to luminescent carbogenic dots from carbohydrates. Chemistry of Materials 2009, 21, 5563–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, D.B.; Pillai, V.K. Electrochemical preparation of luminescent graphene quantum dots from multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Chemistry–A European Journal 2012, 18, 12522–12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pan, K.; Yu, H.; Wang, F.; Kang, Z. Large scale electrochemical synthesis of high quality carbon nanodots and their photocatalytic property. Dalton transactions 2012, 41, 9526–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Rooj, B.; Dutta, A.; Mandal, U. Review on recent advances in metal ions sensing using different fluorescent probes. Journal of fluorescence 2018, 28, 999–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Ullah, R.; Tuzen, M.; Ullah, S.; Rahim, A.; Saleh, T.A. Colorimetric sensing of heavy metals on metal doped metal oxide nanocomposites: A review. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2023, 37, e00187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Mishra, S.; Singh, A.K. Recent progress in the development of MOF-based optical sensors for Fe3+. Dalton Transactions 2021, 50, 7139–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Huang, J.; Ding, L. A recyclable optical fiber sensor based on fluorescent carbon dots for the determination of ferric ion concentrations. Journal of lightwave technology 2019, 37, 4815–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Xu, Q.; Chu, F.; Hou, S.; Xue, L.; Hu, A.; Dai, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, B. Fe3+ Sensing Based on Hydrogel Optical Fiber Doped with Nitrogen Carbon Dots. Journal of Electronic Materials 2024, 53, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y. The optical fiber sensing platform for ferric ions detection: A practical application for carbon quantum dots. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 364, 131857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y. Ratiometric fluorescence optical fiber sensing for on-site ferric ions detection using single-emission carbon quantum dots. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkisson, A.; Gouramanis, D.; Kim, K.J.; Burgess, W.; Siefert, N.; Crawford, S. A Synthetic Pathway for Producing Carbon Dots for Detecting Iron Ions Using a Fiber Optic Spectrometer. Sensors 2025, 25, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Yan, X.; Hu, T.; Li, H.; Cheng, T. Carbon Dots-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Manganese Ion Fiber Sensor for Multi-Use Scenarios. Photonic Sensors 2025, 15, 250311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Xia, B.; Chen, X.; Jing, X.; Wang, N.; Li, J. An ultrasensitive optical fiber SPR sensor enhanced by functionalized carbon quantum dots for Fe3+ measurement. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2025(1030), 180784. [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.H.K.; Chan, K.K.; Zhang, G.; Tjin, S.C.; Yong, K.T. Carbon dot-functionalized interferometric optical fiber sensor for detection of ferric ions in biological samples. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11, 28546–28553. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.K.; Lee, J.; Oh, E.T.; Park, H.J.; Lee, K.H. Ratiometric fluorescence sensing system for lead ions based on self-assembly of bioprobes triggered by specific Pb2+–peptide interactions. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2023, 15, 14131–14145. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, T.; Kumar, H.; Choudhary, S.; Joshi, A. Carbon quantum dot (CQD)-dithizone-based thin-film chemical sensors for the specific detection of lead ions in water resources. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2024, 10, 2858–2868. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V.T.; Tran, N.H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Yoon, W.J.; Ju, H. Liquid cladding mediated optical fiber sensors for copper ion detection. Micromachines 2018, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, T.; Choudhary, S.; Sharan Rathnam, S.; Joshi, A. Fiber-Optic Detection of Aluminum and Copper in Real Water Samples Using Enzyme–Carbon Quantum Dot (CQD)-Based Thin-Film Biosensors. ACS ES&T Engineering 2023, 4, 694–705. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, T.; Joshi, A. Chemical sensor thin film-based carbon quantum dots (CQDs) for the detection of heavy metal count in various water matrices. Analyst 2024, 149, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.E.; Kim, K.J.; Baltrus, J.P. A portable fiber optic sensor for the luminescent sensing of cobalt ions using carbon dots. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2022, 10, 16506–16516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapna, K.; Sonia, J.; Shim, Y.B.; Arun, A.B.; Prasad, K.S. Au nanoparticle-based disposable electrochemical sensor for detection of leptospirosis in clinical samples. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2022, 5, 12454–12463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, N.H.; Chee, H.Y.; Rashid, S.A.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Mahdi, M.A.; Yaacob, M.H. Carbon quantum dots functionalized tapered optical fiber for highly sensitive and specific detection of Leptospira DNA. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 157, 108696. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin, N.H.; Chee, H.Y.; Rashid, S.A.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Zan, Z.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Alresheedi, M.T.; Mahdi, M.A.; Yaacob, M.H. Enhanced detection sensitivity of Leptospira DNA using a post-deposition annealed carbon quantum dots integrated tapered optical fiber biosensor. Optical Materials 2023, 141, 113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Li, H. A new optical fiber biosensor for acetylcholine detection based on pH sensitive fluorescent carbon quantum dots. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 369, 132268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangubotla, R.; Kim, J. Fiber-optic biosensor based on the laccase immobilization on silica-functionalized fluorescent carbon dots for the detection of dopamine and multi-color imaging applications in neuroblastoma cells. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 122, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Ding, L.; Xu, B.; Liang, B.; Yuan, F. A versatile optical fiber sensor comprising an excitation-independent carbon quantum dots/cellulose acetate composite film for adrenaline detection. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 10392–10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

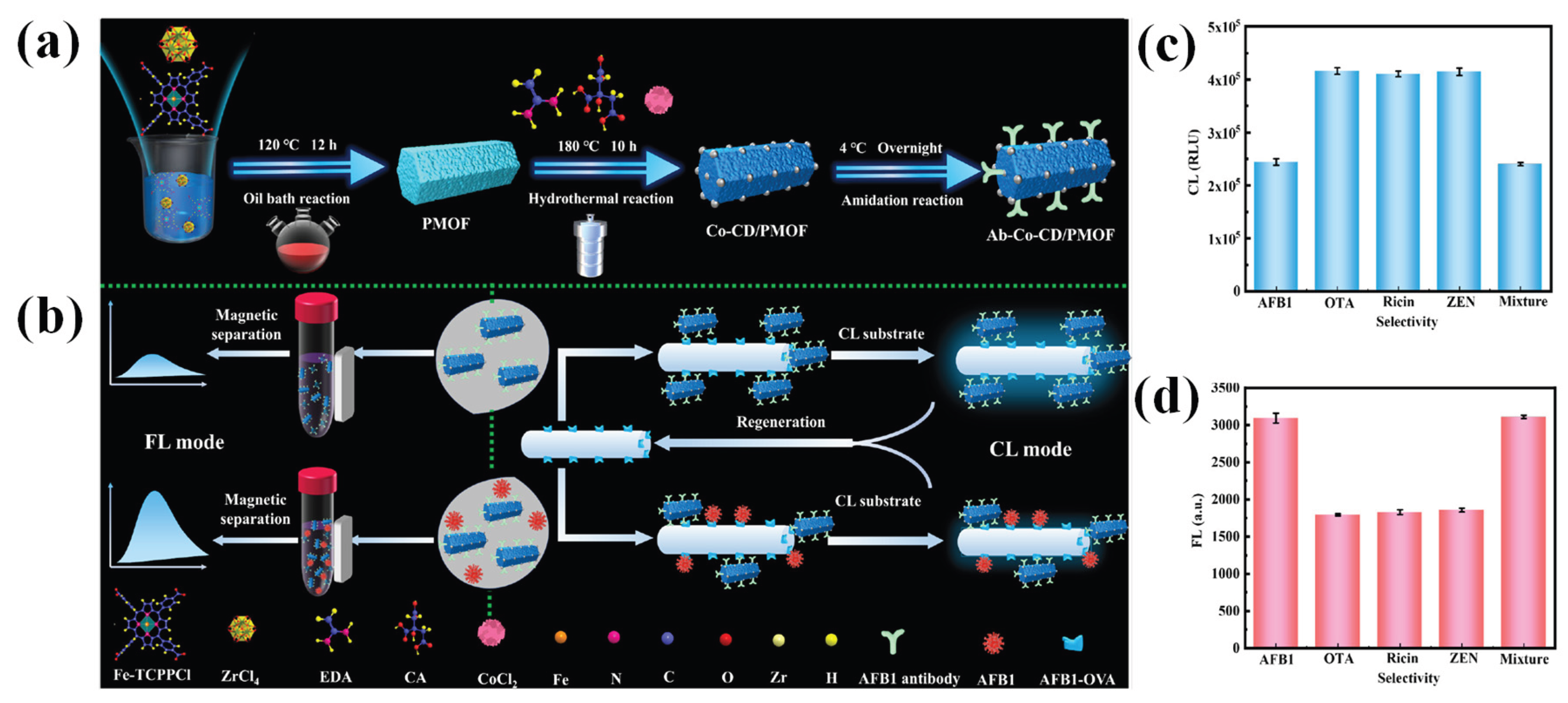

- Yi, Z.; Xiao, S.; Kang, X.; Long, F.; Zhu, A. Bifunctional MOF-encapsulated cobalt-doped carbon dots nanozyme-powered chemiluminescence/fluorescence dual-mode detection of aflatoxin B1. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 16494–16504. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Son, C.; Choi, S.; Yoon, W.J.; Ju, H. A plasmonic fiber based glucometer and its temperature dependence. Micromachines 2018, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tam, T.; Hur, S.H.; Chung, J.S.; Choi, W.M. Novel paper-and fiber optic-based fluorescent sensor for glucose detection using aniline-functionalized graphene quantum dots. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 329, 129250. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Ding, L.; Lin, H.; Wu, W.; Huang, J. A novel optical fiber glucose biosensor based on carbon quantum dots-glucose oxidase/cellulose acetate complex sensitive film. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 146, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, T.; Kumar, H.; Nagpure, G.; Joshi, A. Fiber-optic thin film chemical sensor of 2, 4 dinitro-1-chlorobenzene and carbon quantum dots for the point-of-care detection of hydrazine in water samples. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2024, 10, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Huang, J.; Ding, L.; Lin, H.; Yu, S.; Yuan, F.; Liang, B. A real-time and highly sensitive fiber optic biosensor based on the carbon quantum dots for nitric oxide detection. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2021, 405, 112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, T.; Gogoi, M.; Joshi, A. Fluorescent fiber-optic device sensor based on carbon quantum dot (CQD) thin films for dye detection in water resources. Analyst 2023, 148, 5178–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).