1. Introduction

Galaxy evolution is shaped by at least two types of constraints: internal structure and external environment. Classical environmental studies emphasise quenching, morphology and gas removal as functions of cluster-centric radius, halo mass or local density, while internal studies focus on mass, compactness and star-formation history. The homeostatic potential framework adds another dimension: it treats galaxies as systems that can cross a structural threshold where the balance between energy, stability and chemical memory changes qualitatively.

Previous work [

1] introduced

as a four-component proxy system: an energy coordinate

, a stability coordinate

, a metallicity-based memory coordinate

, and a regeneration coordinate

tied to recent star formation. A structural threshold

separates “infant” galaxies, which are still strongly coupled to their host reservoir, from “adult” galaxies, which behave more like homeostatic processors with internalised memory. Above the gate, energy input and feedback act in a different regime: memory is carried primarily by the internal configuration rather than by current energy injection.

In that picture, environment plays two roles. Below the stability gate, infant galaxies are expected to feel the host halo and local density strongly: their structural and chemical state at a given stellar mass should depend sensitively on halo mass, halo-centric radius and local galaxy density. Above the gate, much of that information should already be locked into the internal configuration. Adult galaxies should still live in haloes and groups, but their chemical memory at fixed mass should be only weakly sensitive to the present-day environment.

This paper asks whether that environmental prediction is visible in real data and in independent simulations. Specifically:

- 1.

Does the metallicity scatter at fixed stellar mass depend more strongly on environment for structurally infant galaxies than for adults?

- 2.

Is any remaining environment dependence at fixed and mass large enough to challenge the homeostatic interpretation, or does it look like a secondary modulation?

- 3.

Do hydrodynamical simulations with different feedback calibrations reproduce the same infant/adult contrast in their environment response?

To answer these questions, the analysis combines three complementary datasets:

SDSS DR8 [

2], with k-nearest-neighbour local density as an environment proxy;

GAMA DR4 [

3], with projected surface density and neighbour distances;

the EAGLE RefL0100N1504 simulation [

4,

5,

6], with host-group halo mass as an environment coordinate;

and extends the tests to the TNG suite, where local density and halo properties are available for controlled experiments. A MaNGA pilot sample provides a resolved sanity check on the behaviour of the stability proxy .

The paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 recalls the

framework and the infant/adult stability gate, and defines the environment measures used in each dataset.

Section 3 describes the SDSS, GAMA, EAGLE, TNG and MaNGA samples and the construction of homeostatic proxies.

Section 4 outlines the environment diagnostics and scatter measurements.

Section 5 presents the environment results, first for the TNG and SDSS catalogues, then for GAMA and EAGLE, with a MaNGA sanity check.

Section 6 discusses the implications for environmental quenching and non-Markovian galaxy evolution.

Section 7 summarises the main findings and outlines future tests.

2. Framework and Environment Diagnostics

2.1. Homeostatic Potential and the Stability Gate

The homeostatic framework represents galaxy state in a reduced space constructed from observables such as stellar velocity dispersion, structural compactness, gas-phase metallicity and star-formation rate. Each coordinate is normalised within bins of stellar mass, redshift and basic environment to remove trivial scaling relations and to isolate non-Markovian behaviour in the residuals. In practice, this means working with ranks or z-scores within controlled bins.

A structural threshold separates two regimes:

Infant regime (): systems are structurally young and plastic. Chemical memory is easily rewritten by recent energy injection and by external conditions.

Adult regime (): systems are more compact and dynamically stable. Memory is carried primarily by the internal configuration rather than by current energy input.

In this sense acts as a stability gate controlling whether energy behaves as a destructive eraser of memory or as a retentive influence.

2.2. Environment as an External Regulator

Environment enters the programme as an explicit external regulator rather than as the primary driver of the proxies themselves. All four components are ultimately evaluated in a space where gross trends with stellar mass, redshift and environment have been normalised out. By construction, this suppresses trivial “scale cheats” in which a simple density dependence masquerades as a homeostatic law. Any residual environment signal that survives this conditioning is therefore interpreted as a genuine modulation of the internal memory budget, not just of the overall scaling.

The environmental tests in this paper are based on three types of diagnostics, depending on the dataset:

- 1.

Local number density from a k-nearest-neighbour estimator (SDSS, TNG): , the number density inferred from the fifth neighbour in redshift or simulation space.

- 2.

Projected surface density and neighbour distances (GAMA): SurfaceDensity and DistanceTo5nn from the GAMA EnvironmentMeasures DMU.

- 3.

Host-group halo mass (EAGLE, TNG): the mass of the parent halo, complemented by group-centric distance and inner/outer flags in the simulations.

In all cases, environment is treated as a scalar external coordinate: the goal is to ask how much additional information it carries about the metallicity scatter at fixed stellar mass and internal stability, not to redefine the stability gate itself.

3. Data and Construction of Proxies

3.1. SDSS DR8: kNN Local Density

The SDSS DR8 analysis [

2] uses the

proxy sample constructed from spectroscopic data over

and a stellar-mass range

. Key ingredients are:

stellar masses from spectral energy distribution fits;

gas-phase metallicities and emission-line SFRs for defining and ;

structural and kinematic measures for and ;

a nearest-neighbour density estimate as the local environment proxy.

The working table used here, sdss_dr8_phi_hat_proxies_env_k5_v1.csv, contains galaxies with finite after all quality cuts. For consistency with the TNG analysis, a single numerical stability threshold is adopted, imported directly from the TNG300 analysis. This is a deliberate cross–redshift test: we ask whether a structural maturity scale calibrated in the simulation at still partitions the low–redshift SDSS population into regimes with distinct environmental responses. As shown below and in the robustness tests of Section , modest shifts in do not change the qualitative environment behaviour.

This splits the SDSS population into and galaxies.

3.2. GAMA DR4: Surface Density and Neighbour Distances

The GAMA DR4 sample is built from several Data Management Units (DMUs), combining stellar masses, velocity dispersions, environment measures and spectral indices into a structural master table. After quality cuts on redshift, redshift quality, stellar mass and finite environment values, the working GAMA sample for consists of galaxies.

The main environment proxies are

SurfaceDensity and

DistanceTo5nn from the

EnvironmentMeasures DMU. A GAMA-specific stability proxy

is constructed from a compactnes The infant/adult split is defined by

yielding

and

in the current analysis.

3.3. EAGLE RefL0100N1504: Host-Group Halo Mass

For the EAGLE simulation, the environment test uses the RefL0100N1504 run at and focuses on galaxies with well-defined stellar mass, structural and chemical properties, and a known host-group halo mass . The working EAGLE sample contains galaxies with finite .

A structural threshold for the environment analysis is defined as

yielding

and

.

3.4. TNG300 at : Simulation Benchmark

The simulation benchmark is the TNG300-1 run from the IllustrisTNG suite [

7,

8,

9]. The analysis uses subhaloes at snapshot 50 (

), restricted to stellar masses

to avoid resolution effects. For each subhalo, four scalar proxies

are constructed from internal kinematics, sizes, metallicities and star-formation histories, following the definitions in Paper I.

The environment catalogue is built directly from the simulation volume. Subhalo positions are converted to comoving coordinates, and a

nearest-neighbour search provides, for each galaxy, the distance

to the fifth neighbour and the corresponding local number density,

The resulting table at

contains

galaxies with finite

.

The same stability gate as above,

is adopted at this redshift. Galaxies with

are labelled infants, those with

are labelled adults. This yields

and

objects.

3.5. MaNGA Pilot Sample: Global Homeostatic Proxies

The MaNGA [

10] pilot sample consists of

datacubes for which LOGCUBE files are available locally. A manifest file records, for each cube, the

plate,

ifu,

plateifu and full path to the FITS file.

For each MaNGA galaxy, the NASA–Sloan Atlas (NSA) parameters attached to the cube are used to construct approximate global proxies :

is taken as a monotonic transform of the NSA stellar mass (e.g. ).

is built from a compactness indicator combining mass and size (e.g. mass minus a function of the half-light radius).

encodes the integrated chemical state via NSA metallicity-sensitive quantities.

At this stage a homogeneous regeneration proxy and a scalar environment proxy have not yet been attached to the MaNGA pilot set, so the main analysis uses MaNGA as a structural sanity check on the behaviour of .

4. Analysis Methodology

4.1. Normalisation and Binning Strategy

To isolate non-trivial environment effects, all homeostatic proxies are normalised within bins of stellar mass and redshift, and where appropriate within broad environment bins, so that residual trends are not driven by simple scaling with mass or survey selection.

The core environment test is based on the dispersion of the memory proxy, , at fixed stellar mass and stability:

- 1.

Split each sample into infants and adults using the appropriate .

- 2.

-

Within each regime, define environment bins:

SDSS and TNG: quantile bins in ,

GAMA: quantile bins in SurfaceDensity,

EAGLE: logarithmic bins in .

- 3.

In each environment bin, compute the standard deviation of around the mass-dependent mean relation.

4.2. Controlling for Stellar Mass

Because metallicity is strongly correlated with stellar mass, the analysis works with mass-residualised memory:

The dispersion

in each environment bin is then interpreted as the chemical-memory scatter at fixed mass.

As a complementary statistic, partial correlations between

and environment at fixed mass and stability are measured, e.g.

where

E is one of

,

SurfaceDensity or

.

4.3. Uncertainties and Robustness Tests

Uncertainties on in each environment bin are estimated via bootstrap resampling. Robustness tests include:

varying within its uncertainty;

changing the number and boundaries of environment bins;

repeating the analysis in narrower mass ranges.

5. Results

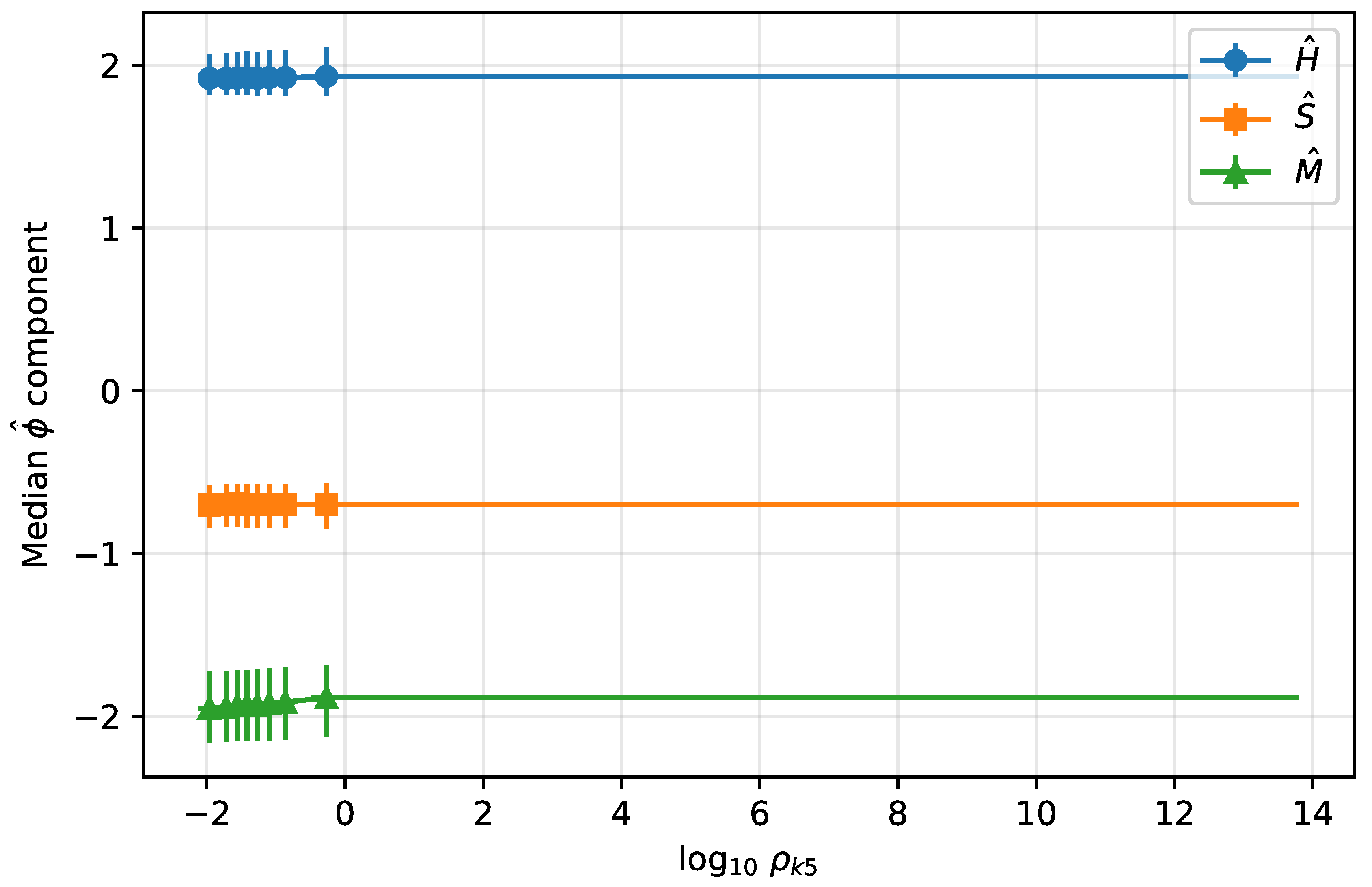

5.1. Environment and the Homeostatic Vector in TNG300

The first test is the controlled numerical universe. At (snapshot 50 of TNG300-1), the joined environment catalogue contains galaxies with finite . The stability gate at splits the sample into and objects.

Global Pearson correlations between fifth-nearest-neighbour density and the three homeostatic components are weak:

The

p-values confirm that these trends are formally detected in this large sample, but the effect sizes remain at the few-percent level. Environment carries only a small fraction of the variance in the homeostatic vector at fixed redshift and mass cut.

A more direct sanity check is the median environment inside each regime. Infant galaxies have , while adults sit at . The median structural and chemical components do move across the gate, as intended: infants are structurally less settled and chemically less mature (, ), while adults are more stable and chemically richer (, ). The environment barely shifts.

Binning

into equal-count quantile bins yields the same picture. Across five bins spanning almost four orders of magnitude in local density, the median stability component remains stable at

to three decimal places, while

and

show only gentle drifts (

Figure 1). There is no sharp environmental trigger for crossing the gate. Instead, the transition from infant to adult proceeds at almost fixed local density, with environment acting as a mild modulator of the already self-organised internal state.

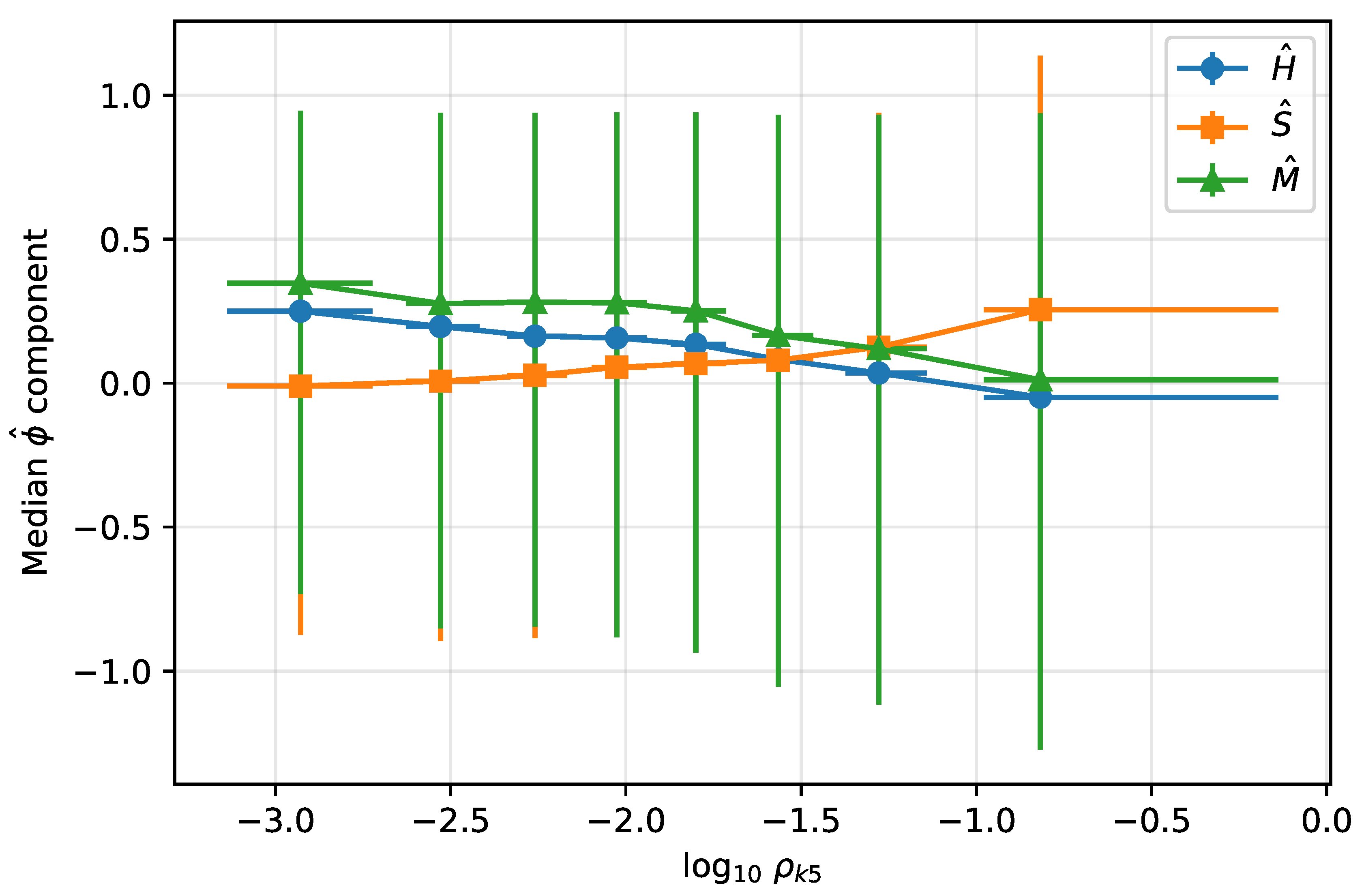

5.2. Environment and the Homeostatic Vector in SDSS DR8

The low-redshift observational sample in SDSS DR8 shows a similar structure. After applying quality cuts and the finite mask on , the working table contains galaxies. Using the same stability threshold yields and .

Global correlations between

and the homeostatic components are again small:

The signs differ slightly from TNG300, but all three absolute values remain well below

.

The median environment in each regime is also almost unchanged. Infant galaxies have , while adults sit at . By construction, and separate strongly across the gate: infants are structurally less settled and chemically poorer on average, while adults concentrate near higher stability and higher metallicity. Yet this sharp shift in internal state occurs at nearly fixed environment density.

Binning SDSS galaxies into equal-count quantiles of

confirms the same pattern as in the simulation (

Figure 2). The median

and

evolve only slowly with increasing density, and there is no clear density at which the population suddenly switches from infant to adult. The gate respects environment, but does not seem to be driven by it.

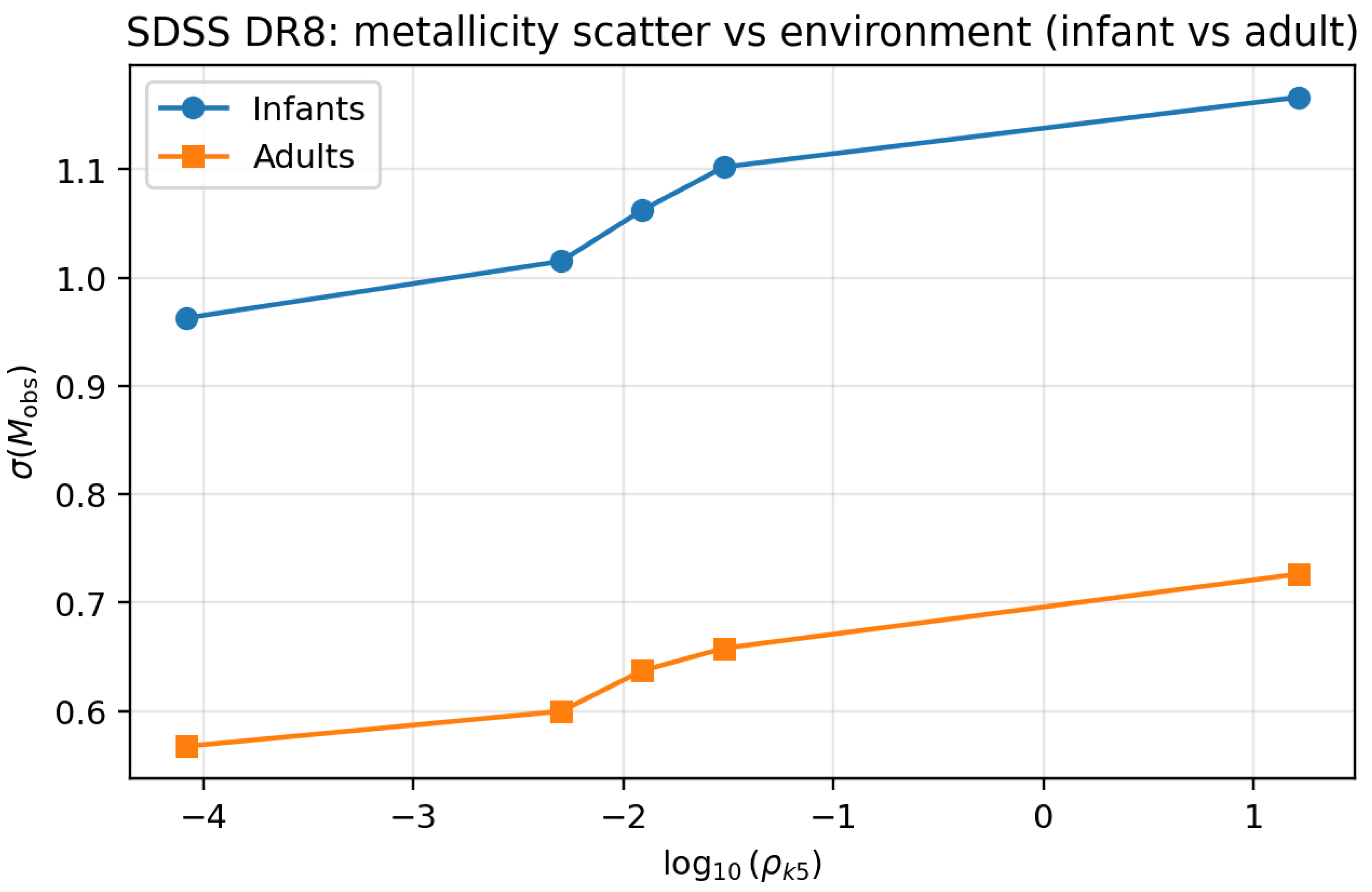

5.3. Metallicity Scatter vs Environment: SDSS, GAMA and EAGLE

The weak vector-level correlations do not by themselves answer how environment affects the memory budget. To address that, the dispersion of the metallicity-based memory proxy, , is measured as a function of environment at fixed mass and stability.

In SDSS DR8, local environment is parametrised by for the same galaxies. Using the stability threshold splits the population into infants and adults as above. Within each regime, is measured in bins of spanning field to group/cluster environments. For the infant class, the metallicity scatter is both larger overall and rises steeply with density: increases significantly from the lowest to the highest bins. For the adult class, is lower and shows a much weaker dependence on . At fixed stellar mass, kNN density is therefore a strong modulator of chemical memory before the stability gate is crossed; after that, density mostly adjusts the residual scatter. This is the clearest “environment × stability-gate” result in SDSS.

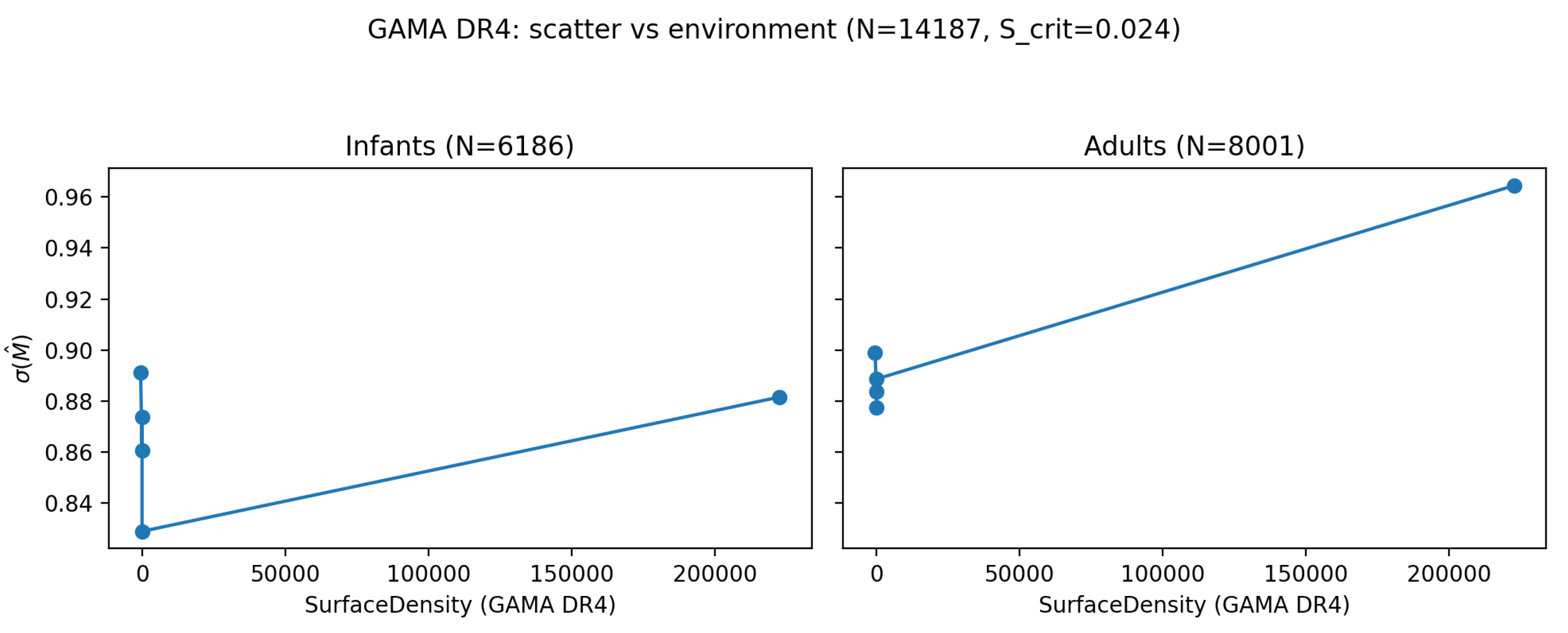

In GAMA DR4, environment is characterised using the EnvironmentMeasures DMU. The main proxy is a projected surface density . Within each stability class, the metallicity-scatter proxy is measured in five bins of spanning field, group and cluster-like environments. For infants, lies in the range – dex, with only weak, non-monotonic variation across . For adults, is essentially flat at – dex over roughly four decades in surface density, with at most a per cent enhancement in the highest-density bin. Once galaxies are conditioned on their internal stability class, local surface density is second-order for metallicity scatter at fixed mass. Most of the apparent environment imprint is already encoded in ; only the most extreme group/cluster densities measurably broaden the memory distribution.

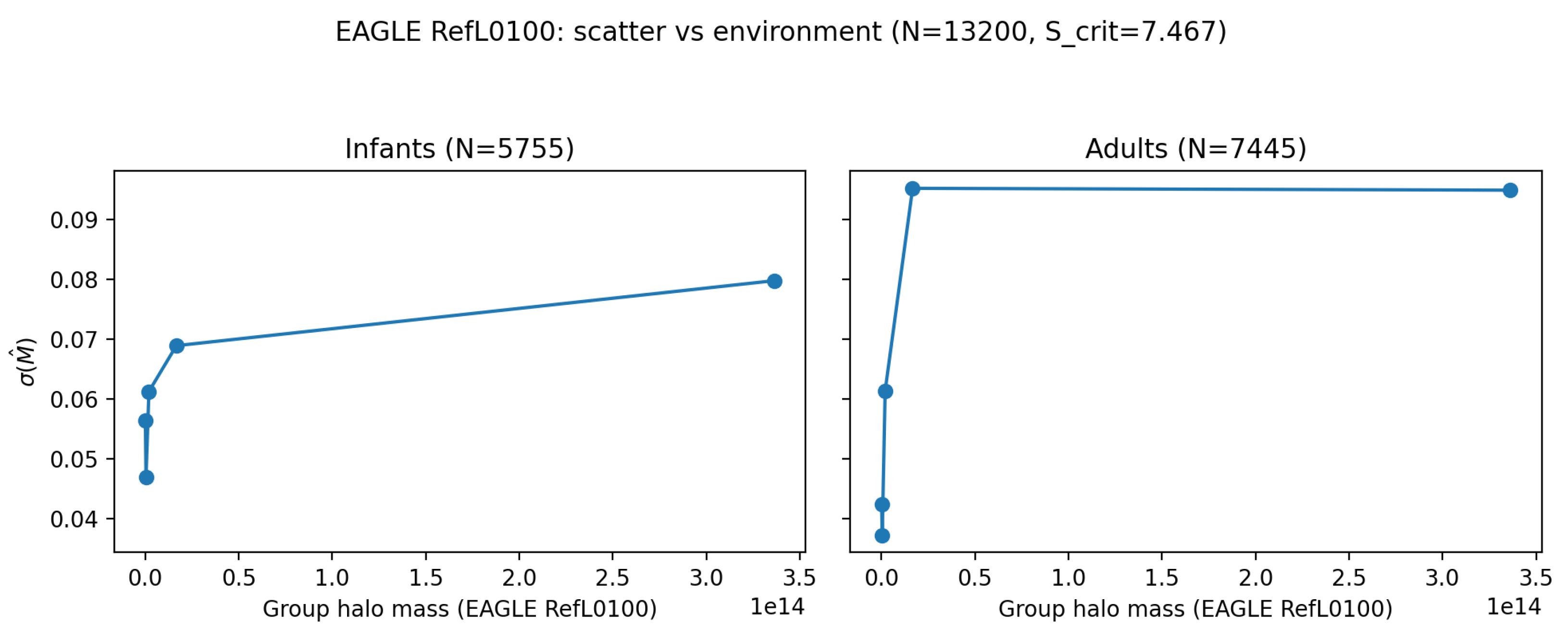

In the EAGLE RefL0100N1504 simulation, environment is captured by the host-group halo mass . Within each stability class, galaxies are binned into five logarithmic bins in with at least galaxies per bin, and is measured as a function of halo mass. For infants, is roughly constant across the full range of . For adults, shows at most mild variation at the highest halo masses. EAGLE therefore does not produce a strong tightening or broadening of the mass–metallicity relation as a function of host halo mass once internal stability is fixed. The dominant control parameter for metallicity scatter is the internal structural state, not the group-scale environment.

5.4. Joint Picture: Environment as a Weak Handle

Taken together, the TNG, SDSS, GAMA and EAGLE results tell a consistent story.

In both TNG300 and SDSS, the absolute correlations between the environment proxy and the homeostatic components remain at the level . Environment knows about the homeostatic state, but only faintly.

The stability gate defined by a single threshold in produces a large structural and chemical separation between infants and adults, while the median environment changes by only a few per cent. Most galaxies cross the gate without moving into dramatically different large-scale environments.

In SDSS, metallicity scatter responds strongly to environment only in the infant regime. In GAMA and EAGLE, the dependence of scatter on environment is weak in both regimes, with only mild broadening in the densest bins.

Environment acts more like a small tilt on the landscape than a switch that flips the system from one basin to another. The main part of the homeostatic transition appears to be governed by internal self-regulation and local structure, with environment providing only a weak handle. This is exactly the pattern expected if environment is a parameter in the homeostatic law rather than its primary driver. In combination with the “processor–to–reservoir” transition identified in [

1] these results support a unified picture in which the stability gate is primarily an internal structural transition: environment shapes how quickly systems reach it, but once across, the long–lived memory budget is set by the homeostatic state rather than by the present–day density field. In SDSS, the strong environment leverage in the infant regime is consistent with a phase where the host still writes actively on the chemical state before stability internalises that memory.

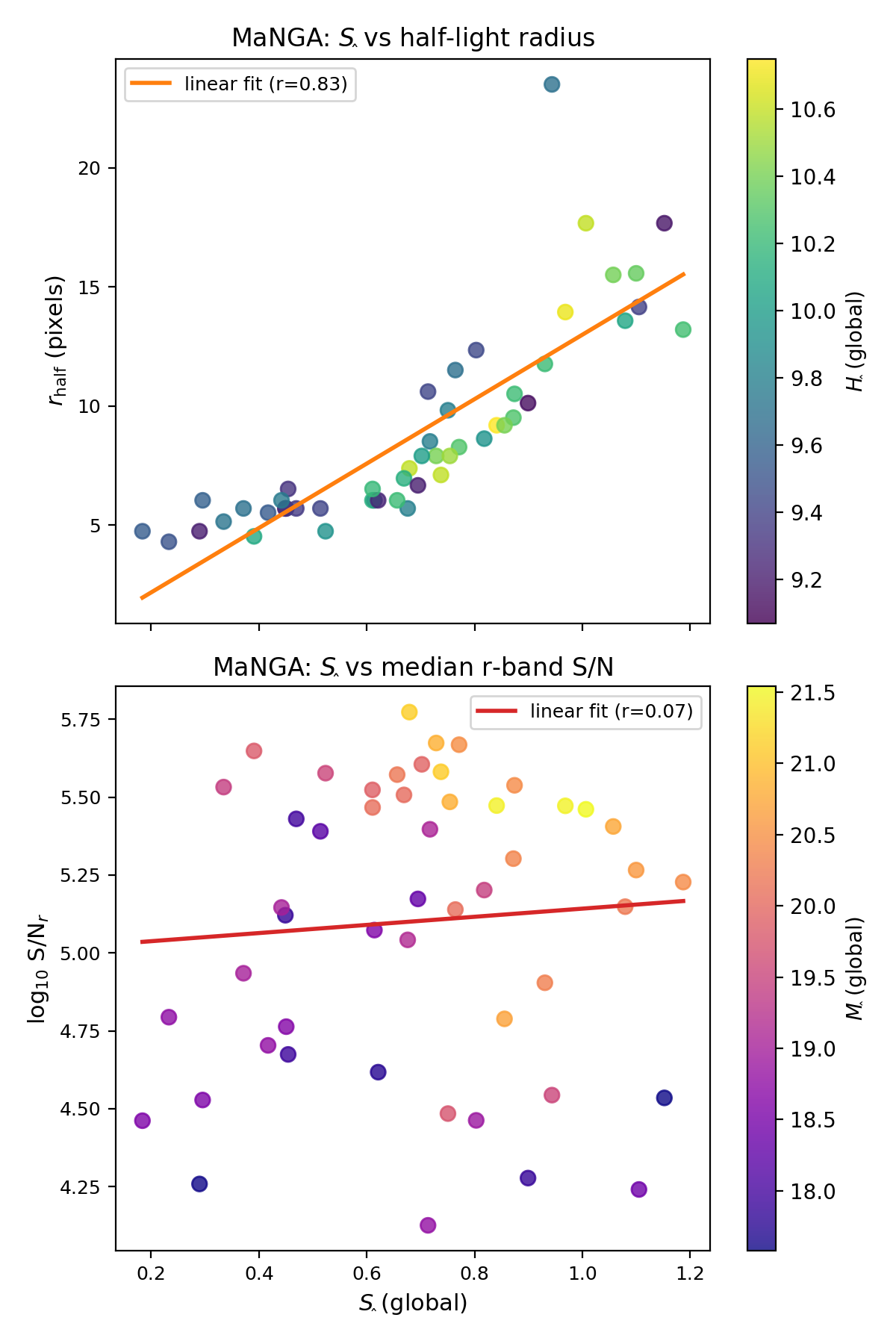

5.5. MaNGA Pilot: Structural Sanity Check

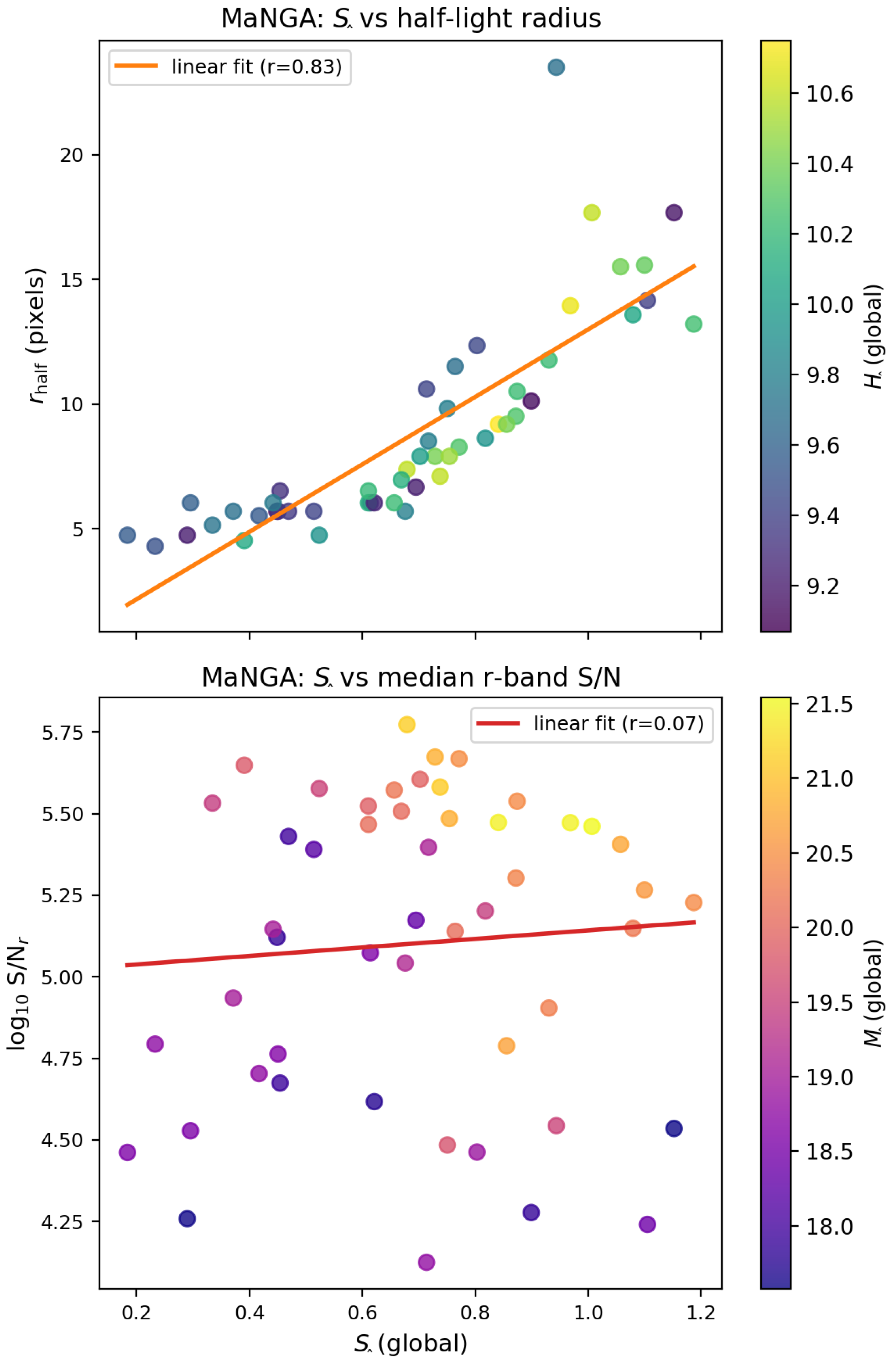

The MaNGA pilot sample currently provides global homeostatic proxies for plate-IFUs, constructed from NSA stellar masses, sizes and metallicity-sensitive quantities. At this stage a homogeneous scalar environment proxy has not yet been attached to the sample, so the MaNGA results are presented as a structural cross-check rather than a full environment test.

In the subspace, the MaNGA galaxies occupy the same region as SDSS objects of similar stellar mass, and the same stability gate at cleanly separates two regimes in the pilot set. A dedicated structural test was carried out by joining the global proxies to basic cube properties, namely half-light radius in pixels () and median r-band S/N per spaxel.

In this sample, the entropy-like component

shows a strong positive correlation with half-light radius,

while its dependence on median S/N (using

) is statistically weak,

By contrast, the mass- and memory-like components

and

correlate strongly with

,

as expected for proxies that primarily track stellar mass and luminosity. Across tertiles in

, the median half-light radius increases monotonically from

to

pixels, while the S/N distribution remains broad in each bin.

These MaNGA pilot results indicate that is not a trivial S/N artefact but behaves as a structural maturity indicator (linked to galaxy size), in a manner consistent with the SDSS and TNG benchmarks.

6. Discussion

6.1. Environment as a Modulator, Not a Primary Container

Across SDSS, GAMA, EAGLE and TNG, the same structural story emerges: once internal stability is fixed, environment mainly modulates the residual scatter in chemical memory rather than setting it from scratch.

In SDSS, local density still has visible leverage in the infant regime but only modest leverage in the adult regime. In GAMA and EAGLE, the dependence is weaker overall. This is consistent with a non-Markovian picture in which environment strongly shapes the path to the stability gate but plays a smaller role once the system has internalised its history.

The MaNGA pilot reinforces this interpretation from a different angle: the stability coordinate behaves as a structural maturity indicator tightly linked to galaxy size, with only weak dependence on S/N. The stability gate is therefore measuring something real about the internal configuration, not repackaging environment or data quality.

6.2. Relation to Classical Environmental Quenching

Classical environmental quenching studies focus on suppression of star formation in dense environments. The results here are complementary: they show that the memory of past enrichment and energy flow can be largely insulated from present-day density once structural stability is high.

A galaxy can be quenched in the classical sense while still carrying a memory pattern that is primarily set by its own structure rather than by its present host halo. Conversely, structurally young systems can exhibit strong environment imprints in their chemical scatter even if they are not yet fully quenched. Quenching and homeostatic memory regulation, while related, are not the same knob.

6.3. Limitations and Selection Effects

Several limitations should be kept in mind:

Environment proxies differ between datasets (kNN density, surface density, halo mass), which blurs direct quantitative comparisons.

The analysis focuses on relatively massive galaxies and modest redshift ranges; lower-mass systems might show stronger or different environment responses.

Scatter estimates are sensitive to measurement errors and to the chosen metallicity calibrator.

TNG environment tests are, so far, primarily vector-level and median-based; a full scatter-versus-density analysis analogous to SDSS, GAMA and EAGLE is a natural next step.

Future work could extend the analysis to lower-mass galaxies, higher redshifts, and alternative environment definitions, including filament and void classifications. Cluster-scale tests, where the intracluster medium plays the role of and clusters themselves are treated as homeostats, are an obvious next rung in the ladder.

7. Conclusions

This paper has used the homeostatic potential framework to test how environment modulates chemical memory at fixed stellar mass and internal stability. The main conclusions are:

- 1.

Structurally infant galaxies show a stronger dependence of metallicity scatter on environment than adults, consistent with a phase in which external conditions still write strongly on their chemical state.

- 2.

Once galaxies cross the stability gate, metallicity scatter depends only weakly on environment across a broad range of densities and host halo masses. Most of the environmental imprint appears to be encoded in the stability coordinate itself.

- 3.

Hydrodynamical simulations with different feedback calibrations broadly reproduce this pattern at the vector level and provide a sandbox for future environment experiments; they also reveal model-dependent behaviour in the adult regime, offering a useful target for calibration.

- 4.

A MaNGA pilot sample confirms that the entropy-like component behaves as a structural maturity indicator rather than a data-quality or environment proxy, supporting the physical interpretation of the stability gate.

In this sense, environment acts as a modulator of homeostatic potential: crucial for shaping the path to structural stability, but a secondary player once galaxies have become stable processors of their own history.

Funding

This research received no funding from any public or private entity.

Data Availability Statement

The analysis pipeline for this work, including derived proxy tables, summary products, and figure-generation scripts, is available in the

ciou_phi_hat repository at

https://github.com/Atalebe/ciou_phi_hat.

Acknowledgments

This work makes use of spectroscopic data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). The SDSS-I/II data release used here is based on SDSS DR8, while the integral-field spectroscopy is drawn from the SDSS-IV MaNGA survey. Further information on SDSS and its participating institutions can be found at

https://www.sdss.org. The analysis also uses data from the Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA) survey, specifically the DR4 value–added catalogues. GAMA is a joint European–Australasian project that combines data from a wide range of facilities; the survey and its public data releases are described at

http://www.gama-survey.org. Numerical comparisons are performed using the IllustrisTNG simulations (TNG100 and TNG300). The IllustrisTNG project is a collaboration between institutions in Germany and the United States, and the simulations were carried out on computing facilities at the Max Planck Computing and Data Facility and other partner centres. This work further uses catalogues from the EAGLE (Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments) simulations. The EAGLE project is a collaboration led by the Virgo Consortium, and the simulations were performed on computing resources in the UK and Europe; the public database is described in [

11]. The MaNGA analysis in this paper is based on the public data products produced by the MaNGA Data Analysis Pipeline (DAP). The author acknowledges the MaNGA hardware, software and survey teams for making these maps and catalogues available to the community. I thank the anonymous referee for constructive comments that helped clarify the presentation and colleagues for discussions that improved the interpretation of the homeostatic potential and the "double flip" picture.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Atalebe, S. From Processors to Reservoirs: The Stability Gate and the Homeostatic Double Flip in Galaxy Evolution. Preprints 2026, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, H.; Allende Prieto, C.; An, D.; et al. The Eighth Data Release of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey: First Data from SDSS-III. Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2011, 193(29), 1101.1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, S.P.; Bellstedt, S.; Robotham, A.S.G.; et al. Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA): Data Release 4 and the Low-Redshift Galaxy Population. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2022, 513, 439–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaye, J.; Crain, R.A.; Bower, R.G.; et al. The EAGLE Project: Simulating the Evolution and Assembly of Galaxies and their Environments. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 446, 521–554, [1407.7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, R.A.; Schaye, J.; Bower, R.G.; et al. The EAGLE Simulations of Galaxy Formation: Calibration of Subgrid Physics and Model Variations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 450, 1937–1961, [1501.01311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, S.; Helly, J.C.; Schaller, M.; et al. The EAGLE Simulations of Galaxy Formation: Public Release of Halo and Galaxy Catalogues. Astronomy and Computing 2016, 15, 72–89, [1510.01320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.; Springel, V.; Pillepich, A.; et al. The IllustrisTNG Simulations: Public Data Release. Computational Astrophysics and Cosmology 2019, 6(2), 1812.05609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, V.; Pakmor, R.; Pillepich, A.; et al. First Results from the IllustrisTNG Simulations: Matter and Galaxy Clustering. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2018, 475, 676–698, [1707.03397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillepich, A.; Springel, V.; Nelson, D.; et al. Simulating Galaxy Formation with the IllustrisTNG Model. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2018, 473, 4077–4106, [1703.02970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, K.; Bershady, M.A.; Law, D.R.; et al. Overview of the SDSS-IV MaNGA Survey: Mapping Nearby Galaxies at Apache Point Observatory. Astrophysical Journal 2015, 798(7), 1412.1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, S.; et al. The EAGLE simulations of galaxy formation: Public release of halo and galaxy catalogues. Astronomy and Computing 2016, 15, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

TNG300 snapshot at . Median simulated homeostatic components , , and as a function of fifth–nearest–neighbour density , again binned into equal count environment quantiles. Error bars show the 16th to 84th percentile range. As in the SDSS data, the structural term stays nearly constant with environment, while and change only very weakly. The weak and monotonic behaviour in both the simulation and the real universe supports our working assumption that environment modulates homeostatic state but does not set it.

Figure 1.

TNG300 snapshot at . Median simulated homeostatic components , , and as a function of fifth–nearest–neighbour density , again binned into equal count environment quantiles. Error bars show the 16th to 84th percentile range. As in the SDSS data, the structural term stays nearly constant with environment, while and change only very weakly. The weak and monotonic behaviour in both the simulation and the real universe supports our working assumption that environment modulates homeostatic state but does not set it.

Figure 2.

SDSS DR8 galaxies with fifth–nearest–neighbour density . Median global homeostatic components , , and as a function of , binned into eight equal count environment quantiles. Error bars show the 16th to 84th percentile range in each bin. For this catalogue the paper builds , , and from the observed proxies , , and by a simple internal z score. The structural component is almost flat with environment, while and show only weak trends even across almost three orders of magnitude in .

Figure 2.

SDSS DR8 galaxies with fifth–nearest–neighbour density . Median global homeostatic components , , and as a function of , binned into eight equal count environment quantiles. Error bars show the 16th to 84th percentile range in each bin. For this catalogue the paper builds , , and from the observed proxies , , and by a simple internal z score. The structural component is almost flat with environment, while and show only weak trends even across almost three orders of magnitude in .

Figure 3.

Metallicity scatter as a function of local kNN density in SDSS DR8, split into structurally infant and adult galaxies. Infants show larger overall scatter and a strong rise with density; adults show lower scatter and a much weaker environment trend.

Figure 3.

Metallicity scatter as a function of local kNN density in SDSS DR8, split into structurally infant and adult galaxies. Infants show larger overall scatter and a strong rise with density; adults show lower scatter and a much weaker environment trend.

Figure 4.

GAMA DR4 metallicity scatter as a function of projected surface density , split into infant and adult galaxies by the GAMA stability proxy. Scatter is essentially flat once stability is fixed, with only a mild broadening in the highest-density adult bin.

Figure 4.

GAMA DR4 metallicity scatter as a function of projected surface density , split into infant and adult galaxies by the GAMA stability proxy. Scatter is essentially flat once stability is fixed, with only a mild broadening in the highest-density adult bin.

Figure 5.

EAGLE RefL0100N1504 metallicity scatter as a function of host-group halo mass , shown separately for structurally infant and adult galaxies. Host halo mass produces, at most, mild scatter changes at the highest .

Figure 5.

EAGLE RefL0100N1504 metallicity scatter as a function of host-group halo mass , shown separately for structurally infant and adult galaxies. Host halo mass produces, at most, mild scatter changes at the highest .

Figure 6.

MaNGA pilot sanity check for the global proxies. Top: entropy-like component versus IFU half-light radius in pixels, coloured by . Bottom: versus median r-band S/N per spaxel, coloured by . The strong correlation between and size, combined with the weak dependence on S/N, shows that behaves as a structural maturity indicator rather than a data-quality artefact.

Figure 6.

MaNGA pilot sanity check for the global proxies. Top: entropy-like component versus IFU half-light radius in pixels, coloured by . Bottom: versus median r-band S/N per spaxel, coloured by . The strong correlation between and size, combined with the weak dependence on S/N, shows that behaves as a structural maturity indicator rather than a data-quality artefact.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).