1. Introduction: Ship Energy in the Sustainable Era

Historically, shipping has relied heavily on – abundant and until the oil shocks of the 1970s also inexpensive - fossil fuels, transitioning from coal to oil in the years to World War II. The adoption of a novel on each occasion vessel power source had been commonly driven by market considerations such as availability, cost, operational efficiency and alignment with worldwide technological advancements. In the last two decades, however, rising regulatory pressures and market-driven sustainability goals drove cost concerns largely to the sidelines, driving themselves instead of the adoption of alternative fuels. As a consequence, industry began exploring new options, such as LNG, methanol, biofuels, ammonia or hydrogen to significantly reduce emissions [

1]. This was together with either the consideration or the practical implementation of other main or supplementary energy sources for ships, stretching from the most debated nuclear power to wind-assisted propulsion systems (WAPS) to address heightened environmental pressures and fast-evolving regulatory demands [

2]. At present, a number of new fuels have had already practical applications either as sole sources of energy for vessels or on the basis of dual-fuel ship engines. However, technological, environmental and regulatory aspects are changing fast with, as an example, the most popular fuel replacement choice, Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), emerging itself as a target of Green House Gas (GHG) regulation due to its composition from methane. As a result, this popular alternative choice to oil is treated anymore as “transition fuel”, albeit with the final duration of the transition phase eventually longer than currently considered [

3].

This transition is not so much different from the transitional stages of past fuel shifts as there are already de facto parallel supply chains for alternative fuels. However, the current transition is induced by regulation with the absence of clear direction, exacerbated delays in the relevant definitive decisions in the context of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) [

4], justified as these may be due to lack of sufficient research, increases investment risks. In this context, the pattern of past transitions by which a unique vessel power source prevails for about a century until another one completely dominates seems less likely. At, the same time any sudden policy shifts due to intensifying environmental pressures could lead to rapid obsolescence of certain fuels, effectively causing “sudden death” scenarios for some of the now emerging new energy source supply chains.

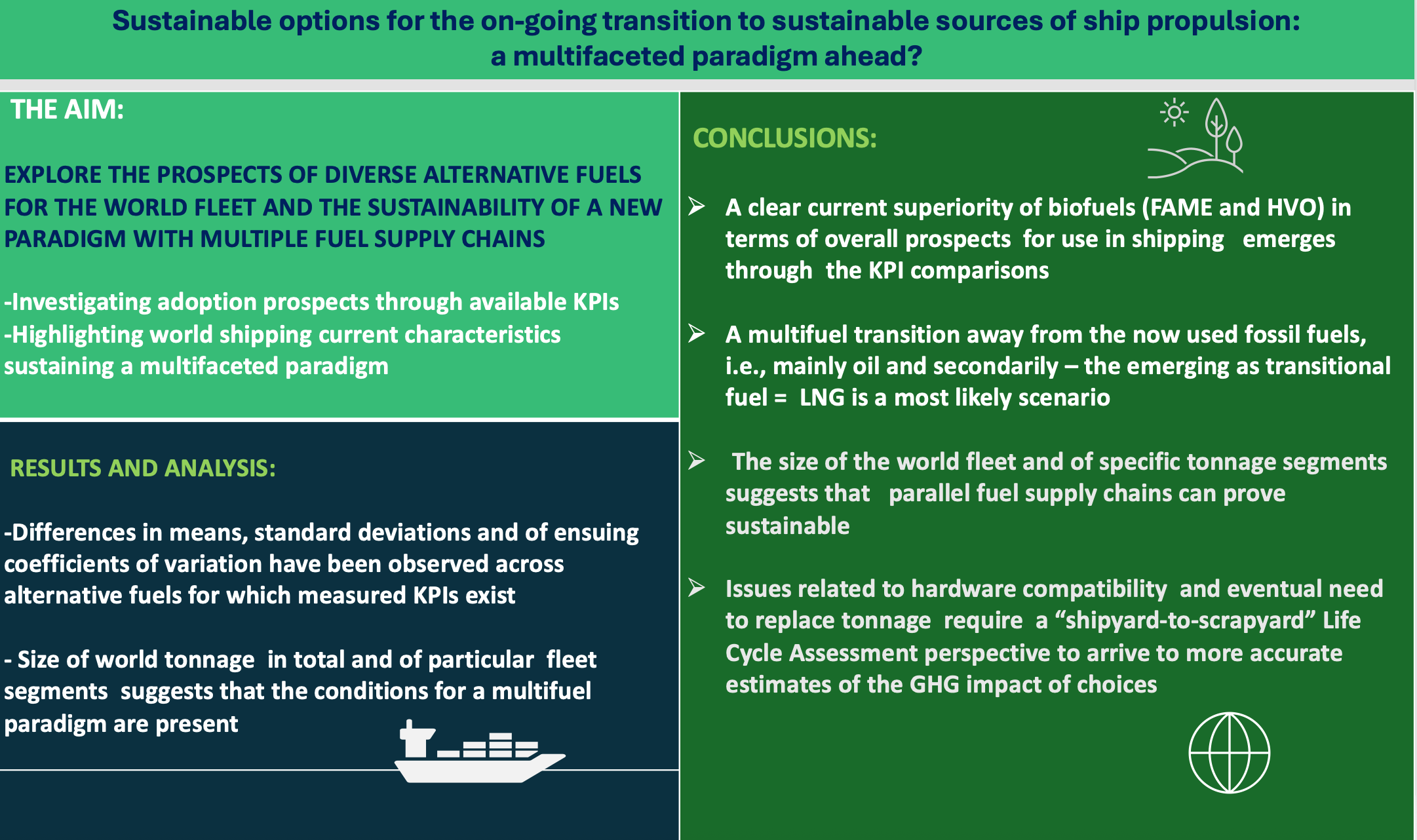

The research question of the paper explores the sustainability of supply chains of alternative fuels within an evolving regulatory and technological landscape. As key part of this process, the authors proceed to a first analysis of descriptive statistics of KPI values which have been put forward regarding ship fuel supply chains with the aim to explore differences in fuel supply chains overall readiness and in the level of their vulnerability which may remain hidden behind high average scores. The focus of the authors turns next to how the - massively different today - key attributes of the world fleet can support the co-existence of a system of multiple supply chains and to some key challenges this new paradigm may create for shipping operations.

The paper is divided into five sections. Following the introduction,

Section 2 covers the background to the emergence of new vessel energy sources as policy action on shipping emissions accelerated.

Section 3 calculates descriptive statistics from available metrics of KPIs of shipping fuel alternatives pointing to supply chains with high average scores but also to cases where high variability may imply challenges for implementation.

Section 4 lays-out the changed attributes of the world fleet which may allow the successful coexistence of parallel fuel supply chains and points to new operational needs including required new skillsets on board and in ports. The concluding fifth section summarizes prerequisites for establishing a sustainable multi-fuel system, highlighting aspects such as resource-sharing potential, exchange of complementary know-how and the necessity for common specifications to ensure scalable and resilient fuel supply chains.

2. The New Energy Challenge for Shipping: The Background

The 21st century is marked by accelerating and intensive efforts to mitigate environmental pollution including from the maritime industry [

5] through, initially partial, measures intended to improve the GHG footprint of fuel oil. Despite assessed discrepancies of current strategies [

6] the direction of policy points to the abolition of the use of fossil fuels in a not very distant future. According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), global shipping contributes roughly 2–3% of annual CO₂ emissions worldwide with later estimates verging more to the lower end of the range [

7].

As part of the IMO’s Initial GHG Strategy, the industry has been tasked with reducing annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 50% by 2050, compared to 2008 levels. This ambitious target, along with other regional efforts such as the EU’s “Fit for 55” package, aiming to cut emissions by 55% by 2030, accelerated the search for viable alternative fuels while carbon pricing, tax incentives, and subsidies encouraged early adoption to meet climate targets [

8].

Today, technological advancements like dual-fuel engines enable ships to switch between traditional marine fuels and alternatives such as LNG or methanol, providing added flexibility to shipowners. As of 2024, more than 900 LNG-capable vessels are either in operation or in order worldwide [

1,

9]. Engine manufacturers are investing heavily in ammonia and in hydrogen-capable propulsion systems also, aiming to achieve commercial readiness by 2025/2026 [

10,

11].

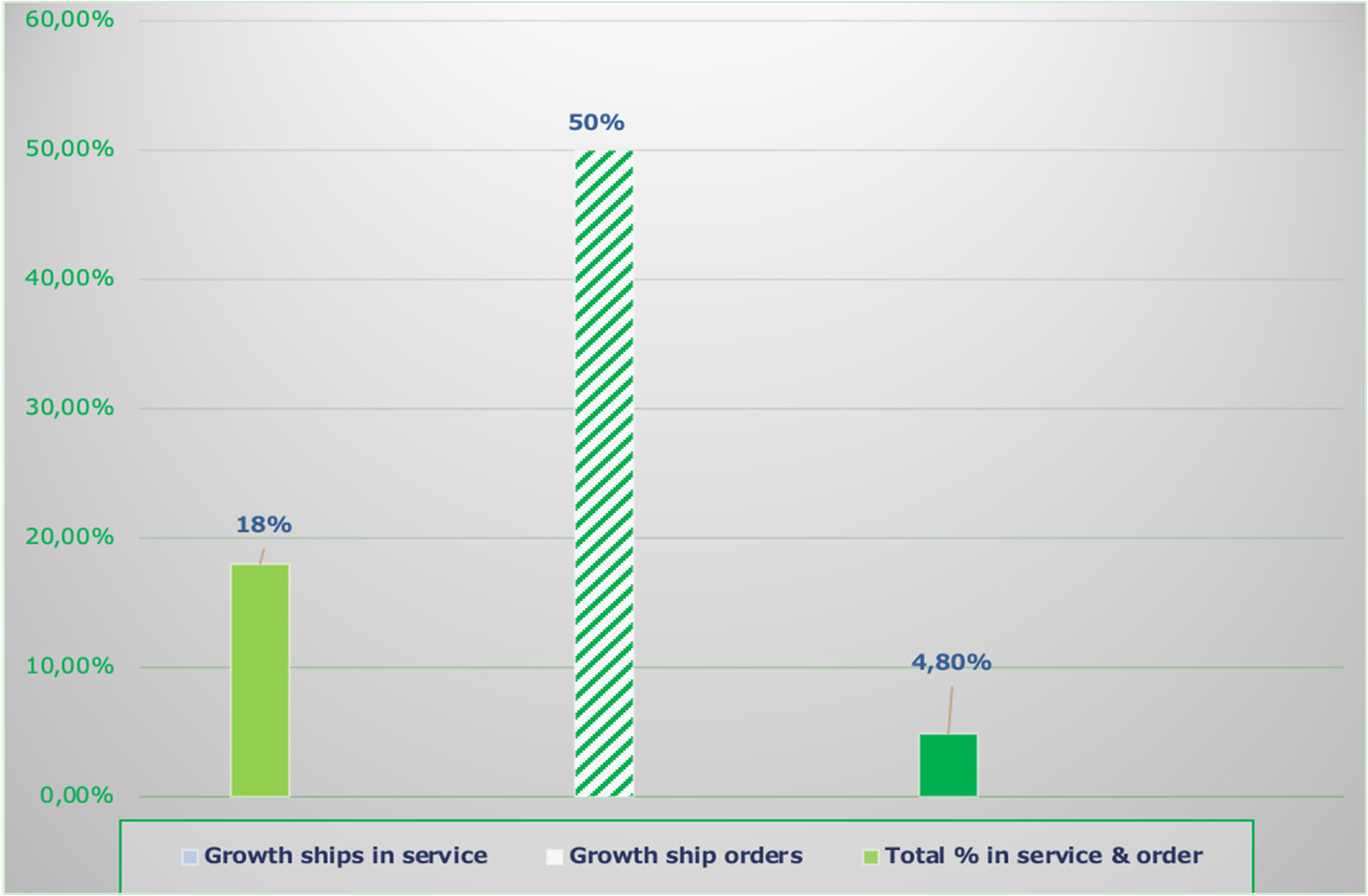

While forecasts for adoption of specific alternative fuels remain highly uncertain, several energy sources, previously considered only as distant possibilities, have now being approaching commercial viability/feasibility. In parallel, the number of vessels capable of utilizing alternative fuels has seen a significant increase with a 50% rise in orders for alternative-fueled ships in 2024. The 600 new vessels added to the orderbook over the past year brought the total to 1,737 reflecting the industry’s commitment to decarbonization [

12]. From the side of ship operators, Maersk had estimated, already in 2022, that its ordered methanol-powered vessels would be cost-comparable to fossil-fuel operations, particularly with the expected rise in carbon taxes on traditional fuels [

13]. Alongside many shipping companies, major port operators have also committed to Zero Emissions Roadmap strategies [

14].

However, rapid developments on both the technological and regulatory fronts keep fueling uncertainty about the sustainability of available solutions. While for some energy sources such as methanol and LNG, there has been direct applicability and commercial applications some others – as ammonia and hydrogen - remain in a more exploratory research phase, in view of safety, technological, and financial concerns. Additionally, there is yet no agreement on how comparative prices of alternative fuels will evolve [

15] nor whether market alignments will ensue to facilitate their broader adoption.

The question at the center of this multi-billion-dollar stake, that the market for marine fuel represents, is a strategic one involving substantial financial risk: setting up any fuel supply chain for alternative fuels requires significant capital investment not only by fuel producers and providers but from maritime infrastructure stakeholders as well. For example, to position Rotterdam as a central hub in the emerging hydrogen economy the Port of Rotterdam has allocated €140 million for hydrogen bunkering facilities with operations expected to start by 2025-2026 [

16]. Other countries, such as Norway, which are pioneers in sustainable technological innovation and in the adoption of LNG as a marine fuel, have been able to develop bunkering networks since the early 2000s [

17], supported by government incentives and/or strict environmental policies. Despite developments, the global readiness of ports for handling next-generation fuels - particularly ammonia and hydrogen - remains limited. Drawing on the lessons from the introduction of LNG as shipping fuel, it appears unlikely that full-scale solutions will be available soon; at least not without close collaboration among key stakeholders, including vessel energy source providers, producers, port authorities, engine manufacturers, classification societies and shipowners [

18].

With safety being always the first Litmus test to be passed in shipping, as alternative fuels are advancing, safety protocols, classification rules and operational standards are introduced, or evolve fast. The International Code of Safety for Ships using Gases or other Low-flashpoint Fuels Code (IGF Code) - originally created for LNG - is now being expanded to encompass additional low-flashpoint fuels such as methanol, ammonia and hydrogen with classification societies heeding fast to provide additional rules [

19].

Unlike past transitions, the current shift, driven by sustainability imperatives, leaves little room for any “trial and error” approach, which cannot be tolerated any-more. The specter of the explosion on Brunel’s “Great Eastern” little after setting to sea for the first time, killing several stokers [

20] and, from afar, its own designer, still lingers to remind how haunting journeys to shipping energy innovation may be.

At a fundamental level, a system of multiple supply chains of ships fuels seems to have already emerged. For nearly two decades, oil and LNG supply chains co-exist and in recent years they have been gradually complemented by some alternative fuels. However, these emerging supply chains differ significantly in terms of their Technological Readiness Level (TRL), a key criterion used to assess their status as viable and sustainable alternatives [

21].

[

22] proceeded to a GHG evaluation of main alternative fuels highlighting the potential in the process of shipping’s decarbonization of green hydrogen, FAME biofuel, and bio-methanol with biofuel presenting the highest stable reduction among the three. [

23] also developed a structured, data-driven framework to help policymakers and maritime stakeholders assess the potential of alternative fuels for achieving shipping decarbonization. They identify 24 sustainability criteria - spanning engineering feasibility, infrastructure readiness, economic cost, environmental performance, and socio-political. Using the Best-Worst Method (BWM), and then Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), they rank five leading fuel options: methanol, hydrogen, biofuels, ammonia, and LNG. The superiority attributed to methanol is based mainly on compatibility with existing infrastructure, low retrofitting requirements, and regulatory readiness. Safety concerns result in hydrogen and ammonia ranking lower, despite being promising for long-term decarbonization potential. Biofuels scored moderately across all criteria with future scalability remaining the basic moot point. Liquefied Natural Gas is ranking last due to methane slip and uncertainty on future regulation towards it. The authors of [

23] consider system-level implications - such as ship conversion costs, port bunkering capabilities, fuel supply stability, and stakeholder perception are brought forward to build a framework positioned to serve as a practical decision-support tool to guide/assist investments and regulatory planning. The review of marine fuels by [

24] is thoroughly, but concisely, presenting their differing properties including - critically - engine and infrastructure availability. Such recent studies confirm the ample evidence on the varying characteristics of alternative fuels along with the existence of dispersion of levels of readiness along the various criteria strengthening the motivation to explore such disparities in order to estimate the sustainability of future ship fuel supply chains as these continue to emerge even more clearly following the initial approach of this prospect by the authors in [

25].

3. Candidate Fuels for the Shipping of Tomorrow: One Answer Does Not Fit All?

While alternative fuels are mainly discussed in terms of their potential to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the production pathway has a decisive impact on their actual carbon footprint. To distinguish between various routes and levels of sustainability, a color-coding approach for the various alternatives has emerged in both academic literature and industry practice. The color associated with a specific fuel (e.g., “green,” “blue,” “grey,” “pink”) indicates the feedstock used, the energy source, and whether carbon capture or other mitigation measures are involved. For instance, “green” denotes production via renewable electricity (e.g., solar, wind); “blue” typically indicates fossil-based production coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce net emissions; “grey” (or “brown”) implies reliance on fossil resources without CCS. This categorization clarifies the life-cycle emissions and can help stakeholders - shipowners, ports, regulators - assess the true environmental benefits of different fuels [

26,

27]. This combination of generic alternative fuels with the specific method of production (whether already achieved or still at experimental level produces the colorful variability of

Table 1, next

- A.

Blue: Production from fossil sources (oil, natural gas, etc.) with CCS technology implemented to reduce net emissions.

- B.

Green: Production from renewable sources (e.g., wind, solar, sustainable biomass) resulting in very low or near-zero net GHG emissions.

- C.

Turquoise: Typically associated with methane pyrolysis, where the carbon byproduct is solid rather than CO₂, reducing GHG emissions—though the upstream energy source still matters.

- D.

Grey/Brown: Indicates fossil-based pathways without carbon capture; can also specifically refer to coal-based as “brown.”

- E.

Pink: Production powered by nuclear energy (low carbon, but not classified as renewable), often through electrolysis for hydrogen and derivative fuels.

- F.

Black Using black coal or lignite (brown coal) in the hydrogen-making process, these black and brown hydrogen are the absolute opposite of green hydrogen in the hydrogen spectrum and the most environmentally damaging.

- G.

Yellow hydrogen is a relatively new phrase for hydrogen made through electrolysis using solar power.

- H.

White hydrogen is a naturally occurring, geological hydrogen found in underground deposits and created through fracking. There are no strategies to exploit this hydrogen at present.

Source: [

1,

13,

16,

18,

26,

27,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]

3.1. Alternative Fuels: Current Applications and Future Prospects

Current market and specialist projections vary: A significant shift towards hy-drogen-based fuels and biofuels is projected while blue ammonia and e-ammonia, in-cluded in

Table 1 also, are optimistically expected to grow from 20% to 60% of ship-ping fuels by 2050. Similarly, liquefied bio-methane (LBM) is projected to account for an average of 34% of shipping fuels by 2050, with production having also been predicted to fall short of vessel needs [

11].

The expected balance between demand and supply for alternative fuels is critical. Tight supply may trigger more energy efficiency measures in shipping operations which is estimated that by themselves could reduce fuel consumption between 4% to 16% by 2030 lowering emissions by 120 million tons of CO₂ [

2]. While potentially contributing to decarbonization targets, such efficiency measures cannot be considered but a partial strategy as are further reductions in average service speed which are already the rule in the market and have been even incorporated in Worldscale [

43].

The question of choosing an alternative fuel, remains, thus, urgent, both at the level of current day-to-day vessel operations and, most critically, at the level of long-term investment decisions. On the one hand, efficient energy sources in shipping are adopted primarily to optimize energy output per unit of fuel consumed, while minimizing emissions and reducing operational costs to comply with new regulations [

44]. On the other hand, however, fluctuating fuel costs and the need for cost-effective alternatives remain critical factors in investment and decision-making [

45]. Ultimately, applicability is the most decisive factor for selection as it is the first ground criterion for the other two to play their role.

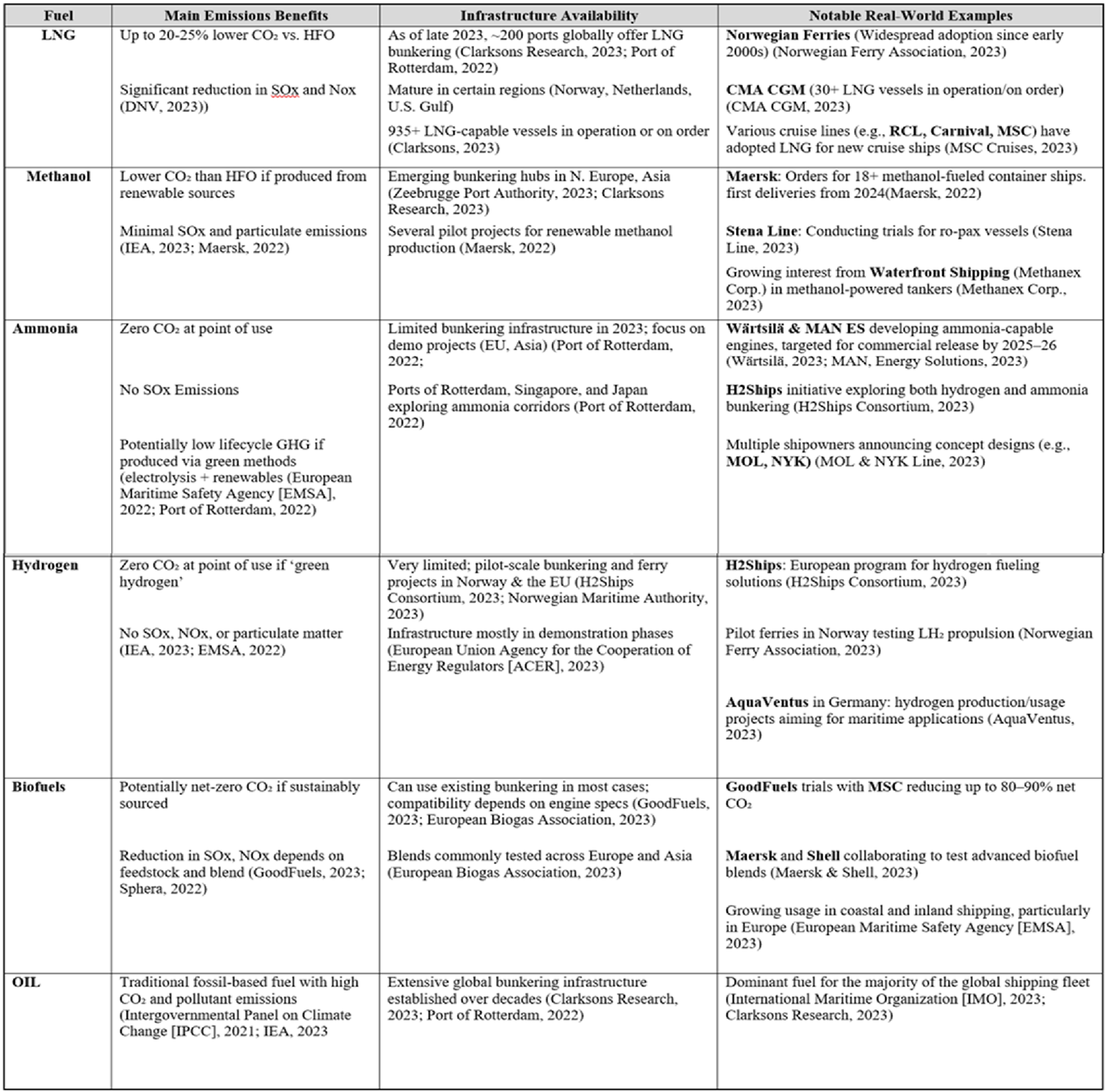

To provide a comprehensive, yet pragmatic, overview of the potential of the supply chains of alternative fuels,

Table 2 below encapsulates key benefits and existing applications of candidate fuels on the basis of recent sources mainly in reports of organizations around shipping such as classifications societies. The table highlights two core evaluation criteria along real-world application examples whereby fuels have already been tested and deployed in operational shipping contexts:

- A.

Main emissions benefits

- B.

Infrastructure availability, assessing whether the necessary fuel supply chains, bunkering facilities, and logistics networks are in place.

Several criteria have been advanced by specialist organizations to monitor fuel progress. These include criteria related to TRL, which are commonly applied in emerging products [

9]. Each alternative fuel may differ in terms of technological maturity level, in terms of resources, production readiness, port infrastructure capabilities and in terms of vessel adaptability readiness either to handle and store or to use a specific fuel for propulsion.

KPIs included in the main sources consulted for this analysis can be grouped as follows:

- i.

Well-to-Wake Emissions – Assessing total emissions from fuel production to onboard combustion [

44].

- ii.

Energy Density & Storage Requirements – Analyzing storage complexity for different fuels [

45].

- iii.

Fuel Scalability & Infrastructure Readiness – Evaluating global bunkering supply network expansion [

31].

- iv.

Economic Feasibility – Considering lifecycle costs, including production, transportation, and onboard utilization [

30].

- v.

Technology Readiness Level, used not only at a composite level but also at a more specific one e.g., TRL of propulsion (TRL P), or for Handling and Storage (TRL H&S) as in [

9].

At the level of efficiency of the supply chain of an alternative fuel, main criteria include the ability to deliver the required energy sources to vessels in a cost-effective manner [

51], reducing environmental impact [

5], overcoming logistical challenges [

26], aligning with sustainability goals and regulatory requirements [

30], suitability for fuel adoption by major shipping lines [

52], reducing logistical bottle-necks and supply chain risks [

44] and enhancing long-term price stability and regulatory compliance [

30].

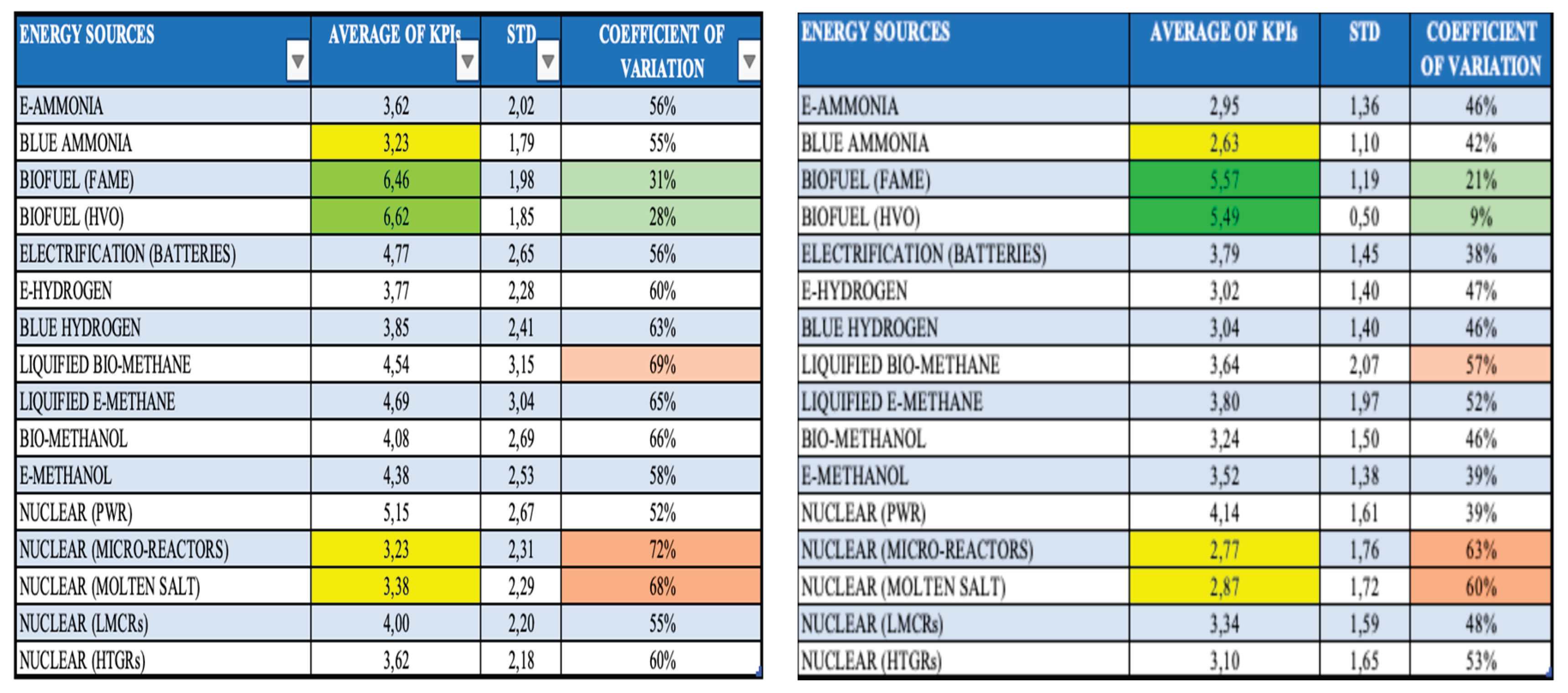

3.2. Supply Chain Prospects for Alternative Shipping Fuels: An Exploration of KPIs

Descriptive statistics have been calculated by the authors for a specific selected range for KPIs that have been advanced [

9] for each of the alternative supply chains of fuels considered. The purpose of these calculations has been to show:

a. How strong is the evaluation of the prospects of a specific shipping fuel supply chain both in absolute and relative terms i.e., compared with other fuel options?

b. Is there any strong variability among the components of such evaluations which may imply hidden risks for the sustainability of the respective supply chain?

As the mean of KPI values for a specific supply chain can be overall high or low but does not provide information on specific weaknesses

Table 3, below, includes - beyond the average of KPI values in the second column - the standard deviation and the coefficient of variation as well for Technology Readiness Level (TRL), Investment Readiness Level (IRL) and Community Readiness Level (CRL) provided for Resources, Production, Bunkering and Ports, plus 4 KPIs for Ships which are TRL Handling and Storage, TRL for Propulsion, the Investment Readiness Level (IRL) and the Community Readiness Level (CRL) on the basis of the values included in [

9].

- a)

Biofuel (FAME): Fatty Acid Methyl Ester

- b)

Biofuel (HVO): Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil

- c)

Nuclear (PWR): Pressurized-water reactor

- d)

Nuclear (LMCR): Liquid metal cooled reactors

- e)

Nuclear (HTGR): High-temperature gas-cooled reactors

Source: Calculated by authors based on the original data as in [

9]. In

Table 3b values were re-calculated through linear transformation

As is the case with the simple use of the mean, the value of the standard deviation fails to reveal by itself the relative cohesiveness of the key aspects of alternative fuel supply chains. To investigate further the resilience of these chains, the coefficient of variation CV, has been also calculated, shown in the last column of both

Table 3a,b.

Table 3a ensues from the original data which were measured in two scales by the data source - 1 to 9 and 1 to 6 - and

Table 3b ensues from the conversion of the five 1-9 series (which were fewer in the original data) to the scale of 1 to 6 - by the original data source for the remaining 8 series, through linear transformation.

Across both Tables 3a,b, shipping fuel supply chains with potential high sustainability emerge clearly through the obvious case of biofuels, a result which matches long-voiced market opinions. Top and worst achievers in terms of the mean and of CV are the same across both Tables along with some minor changes in the respective ranking - mostly by one place - with the notable exception of the last two nuclear supply chains. The CV values for both FAME and HVO biofuels highlight them as the most stable performers with the highest means of KPI values as well. In terms of the latter, the worst performer among the 16 alternatives evaluated by the primary data source, emerges to be Blue Ammonia. This fuel is ranked last and ranks even lower than the other dismal KPI mean performer on the basis of the original data i.e., nuclear propulsion through micro-reactors in terms of its reception in ports. It is interesting also to note that, in the original data, the only fuels that achieve a “top level” mark from the side of the ship in terms of community acceptance are the two biofuels with blue ammonia and all types of nuclear scoring near the bottom in this regard.

Beyond the indications provided by delving into these data on the current pro-spects of supply chains of alternative fuels, the question remains whether multiple chains can indeed be supported today or whether there are analogies with the time of the introduction of Diesel engines and oil as shipping fuel: In that era, a number of alternatives to coal had already emerged [

53], yet they were short-lived with the transition to oil bunkers being solidified rapidly constituting the standard for about the next 100 years. As multiple fuel systems co-existing at terminals can create additional costs, and technical and safety constraints as well, developments in shipping which may allow such a successful parallel existence are discussed next.

4. A Larger World Fleet: Challenges and Opportunities for Alternative Fuels

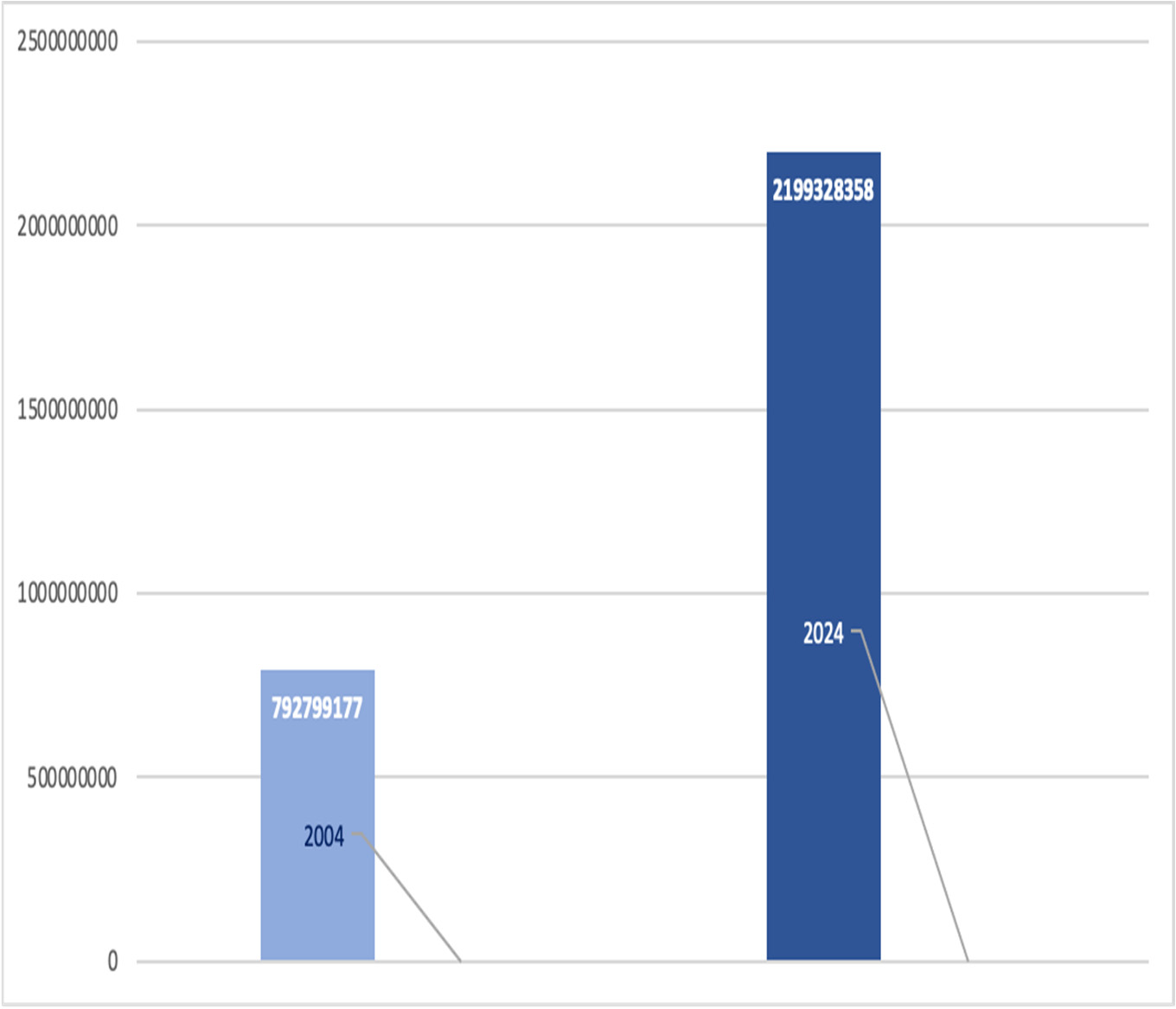

The sheer scale of the current fleet is several times larger than a century ago when diesel engines were introduced to establish oil as the dominant maritime fuel for the next one hundred years (cf.

Figure 1). While the size and the continuous growth of the world fleet might seem at a first level as sustainability challenges, they could eventually support sourcing energy from parallel - and through market size increase now viable - supply chains. By itself, the massively increased tonnage of the world fleet rising from almost 800 million [

54] to well over 2.1 billion dwt [

55] can facilitate the development of parallel and viable energy supply chains.

It must be noted that the increase of the world fleet creates also larger segments in which ships are classified by sector of shipping they operate in, e.g. in ocean-going or in short-sea routes, with the specialization being also related largely to their size. In this respect:

Ocean-going vessels are considered the most likely candidates to transition to ammonia or hydrogen in the long run, although significant technological and safety barriers remain [

56].

Short-sea vessels, particularly prevalent in Northern Europe already benefit from LNG-ready bunkering ports with, for example, the port of Zeebrugge handling already over 150 LNG bunker operations annually [

41].

Cruise operators have already been increasingly interested in methanol and LNG to match strict emission controls near coastal, tourist and ECA areas [

57].

Hence, both the absolute increase of the total tonnage and this of the number of vessels in each specific segment corroborate further the hypothesis that multiple supply chains of vessel energy sources may be supported in the future.

4.1. World Fleet Growth and Its Features: Another Scale for a Different Type of Transition?

During 2024, shipowners kept investing in alternative fuel capable vessels for a future of lower emissions. As a result, the total orderbook has grown by 50%, creating a massive total of 1737 vessels to come in service in the forthcoming years [

20]. While the prospective viability of the commercial operations of any of the emerging supply chains cannot be correlated to their current uptake, the growth trends of vessels already in service and on order, which use or will use alternative fuels, provide a strong indication of the overall alignment of the industry to sustainability requirements. Ultimately, this alignment will shape the market ground for survival, success or disappearance of related fuel supply chains, a phenomenon not unknown in the history of shipping [

53].

As illustrated in

Figure 2, next, the cumulative number of alternative fuel vessels has reached about 5% of total numbers in service and on order, with LNG-fueled vessels still accounting for most. The percentage may appear modest; however, a critical milestone has already been achieved while the overall estimate for the use of alternative to diesel fuels earlier in the decade by [

58] as mentioned also in [

24] is significantly higher by at least a factor of 2. It should also be noted that, by late 2024, the number of alternative-fueled vessels on order reached a 1:1 ratio with those already in service, demonstrating a significant dynamism as shown through the evolution of data in [

21].

4.2. Incorporating the Full Decarbonization Impact: The Next Steps

Such developments at the level of orders for new ships, highlight directly the is-sue of compatibility of new fuels and of the requirements of their operations with the current hardware both in terms of hulls and in terms of equipment; they also highlight the potential impact of the acceleration of shipbuilding and the environmental impact of a faster decommissioning process if the full “cradle to grave” impact of the decarbonization process is taken into account. While scope 3 emissions estimations which broaden the scope of calculation environmental impact have made clear inroads into other industries [

59], there had been until recently [

60] rather limited mention in the literature to this broader shipping services’ system boundary. More holistic approaches have been either rather too recent and tested on specific ship types, such as LNGs by [

61], who include in the evaluation the shipbuilding (Cradle-to-Gate), the vessel operations Gate-to-End and, finally, the scrapping process (End of Operations) as the three constituent stages of such a lifecycle. Such extended approaches succeed earlier partial extensions of the traditional well-to-wake and well-to-tank LCA approaches such as in [

62] for Panamaxes or “cradle-to-propeller” ones as in [

63].

In view of the delay, in late 2025, of the IMO deciding on definitive shipping decarbonization steps ahead, the opportunity arises for embracing such more encompassing LCA frameworks, including the key for ship-fuel transition “shipyard-to-scrapyard” life-cycle of the vessel. Otherwise, the specter of a repetition of the adoption of diesel oil and not of bio-fuel – as presented initially by the inventor of the reigning for about a century Diesel engine himself [

64] – may wield a “trial and error” introduction of new energy sources which may require additional corrections for which there is neither time or any margin to error

5. Conclusions: Operational Challenges in a Multi-Fuel Future

In this paper the authors estimated the current prospects of a significant number of alternative fuel supply chains on the basis of recent data. The results highlighted the relative superiority of readily available vessel energy sources such as biofuels compared to a number of much discussed but, apparently, not so highly evaluated, more innovative and novel to shipping fuels; the picture emerging from the descriptive statistics was clear in terms of the low evaluation of alternatives such as blue ammonia and in terms of vulnerability across most of the fuels considered apart from biofuels.

The biofuel prospect is one that the airline industry was quick to embrace [

65], securing also a rather preferential access at European level [

66] to a resource the availability and the competitive uses of which have been debated largely with the airline industry seeming better poised currently in terms of future fuels than shipping. Although the dim prospect of the production of biofuel being relatively expensive is still being put forward as a major obstacle [

67] it would be a dissonance, if this would be the only alternative to diesel sources so as not to benefit by fast accelerating new technologies as so many other fuels have already. However, no givens can be hypothesized and overall, the shipping sector will have to navigate the challenges of a multi-fuel future which - apart from the - more or less - obvious solutions as that emerge through measures of evaluation and vulnerability - remain uncertain in terms of the number and the nature of energy sources composing it.

5.1. Alternative Fuels—Alternative Challenges

The challenges emerging in the prospect of a multi-fuel future relate to economic, managerial, training and policy aspects, with the list not being exhaustive:

- a)

In terms of economic repercussions, it is possible that an intensification of the climate crisis may result in acceleration of measures which may render obsolete relatively new hardware elements of alternative fuels’ propulsion systems; in the case of older vessels this may render the ship itself obsolete due to the limited amortization period.

- b)

Any need for significant modifications in ship hardware, e.g. engine(s) - or eventually for replacement of vessels themselves due to new fuel requirements - should be considered in the context of any Life-Cycle Assessment of alternative fuels. Any such approach should extend beyond methods of production, treatment, distribution etc. of fuels through any classic LCA methodology – even an all-encompassing and detailed well-to-wake one [

12] – and should include the hardware dimension as well for all ships a view shared, along with the initial suggestion of the authors in [

25], by [

68] when analyzing the case of ammonia.

- c)

Managerial aspects involve primarily the need to secure a properly serviced network of energy sources for the fleet having to take now into account alternative fuels as well; this is especially relevant to network-based operations such as liner shipping [

69].

- d)

Electricity/battery-based solutions – currently mostly chosen in the case of small ferries/ passenger ships which operate in many, though not all, ways as in the container case discussed by [

15] - seem to point to additional constraints for ocean-going vessels. Large freight ships have reduced autonomy considering the length of their standard voyages and the current lack of global density of fuel supply chain networks.

- e)

Finally, the repercussions of parallel fuel supply chains - and of new fuels in general - for shipping operations may be substantial hindering the optimization of the latter put forward as a complementary strategy [

70]. The issue of necessary skills [

17] required for each fuel and respective propulsion system is a crucial aspect, if the industry quickly evolves into a “multi-vessel energy source” future, with potentially multiple fuel distribution networks. While prioritizing training for fuels which would likely dominate in the near term, such as LNG and methanol, to ensure seafarers are adequately prepared for the evolving energy landscape [

65] is proposed, the overall shortage of seafarers, especially at the level of officers [

71] may accentuate gaps further.

Although the analysis of data that preceded shows that some mature solutions already exist, it seems unlikely that, at the current stage, the wisdom of conservation will win over the enthusiasm and the potential gains of innovation. The much larger world fleet of today enables economies of scale and, also, the optimization of fuel distribution networks, making investment in multiple alternative energy sources more feasible. Moreover, the widespread adoption of new fuels like LNG, methanol, and ammonia can be supported by shared infrastructure investments and collaborative industry initiatives, thereby reducing individual costs and enhancing overall fleet sustainability. While definitive regulation is delayed, resource-sharing potential, exchange of complementary know-how and the necessity for common specifications emerge thus as critical to ensure scalable and resilient fuel supply chains in a timely energy-transition process.

5.2. The Need for Further Research and Smart Policy Response Amidst the Climate Crisis

The challenge of new supply chains for novel energy sources is currently acknowledged more or less explicitly. There are scant margins for delaying more coordinated actions and guidance, although 2030 targets have remained unchanged - as the slow speed of progress was realized [

6] - with 2050 being now the next net-zero time-horizon target. However, with climate phenomena adding continuously to new, devastating events across most continents, there may be additional pressure to move the goalposts, turning faster towards Zero Near-Zero GHG (ZNZ) energy sources for ship propulsion systems. Global population growth projections being close to the ten billion mark within the next fifty years [

72] make the prospect of a regulatory push for quicker introduction of ZNZ fuels quite probable. In this context there is need to support the more fragile economies so that they equip themselves with the necessary infrastructure for accommodating new fuels [

9].

From the perspective of shipping supply, the continued growth of vessel order-books is fueling the expansion of the world fleet at about three per cent annually, as per the latest measurement (55). However, the direction and technological feasibility of the shift to alternative fuels are far less predictable; in the case of accelerated intro-duction, risks may emerge, including legal liability risks, not only for fuel providers, but for shipowners/managers as well [

73].

Future policy interventions must take place within workable and efficient frameworks. The SMART-Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time framework [

74] is one suggestion in this respect with emphasis on the timeframe implied by the last term in the acronym. Overall, the next wave of policy measures should, at long-last, focus more on a holistic Life Cycle Assessment - and thus on conservation- at least equally to the currently prevailing focus on innovation. If chances to advance mild alternatives - such as biofuels which do not require massive replacement of vessel hardware - are missed, then the environmental impact of forced replacement of engines or entire vessels may prove hard to balance. A biofuel allowed-use quota for existing, older, but still sustainable if operating on alternative fuel vessels, may be seen as an incentive to avoid their premature replacement which would be a negative outcome from an LCA vantage point. Fuel shifts without a specific time-path of transition may also put infrastructure of terminal points under more pressure. Additional training for personnel onboard and on shore, including ports, is also emerging as a priority.

Research resources should urgently be dedicated to such areas of concern, especially if a Net Zero shipping fuel future - and the constraints that come with it - may come sooner than we currently think.