Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

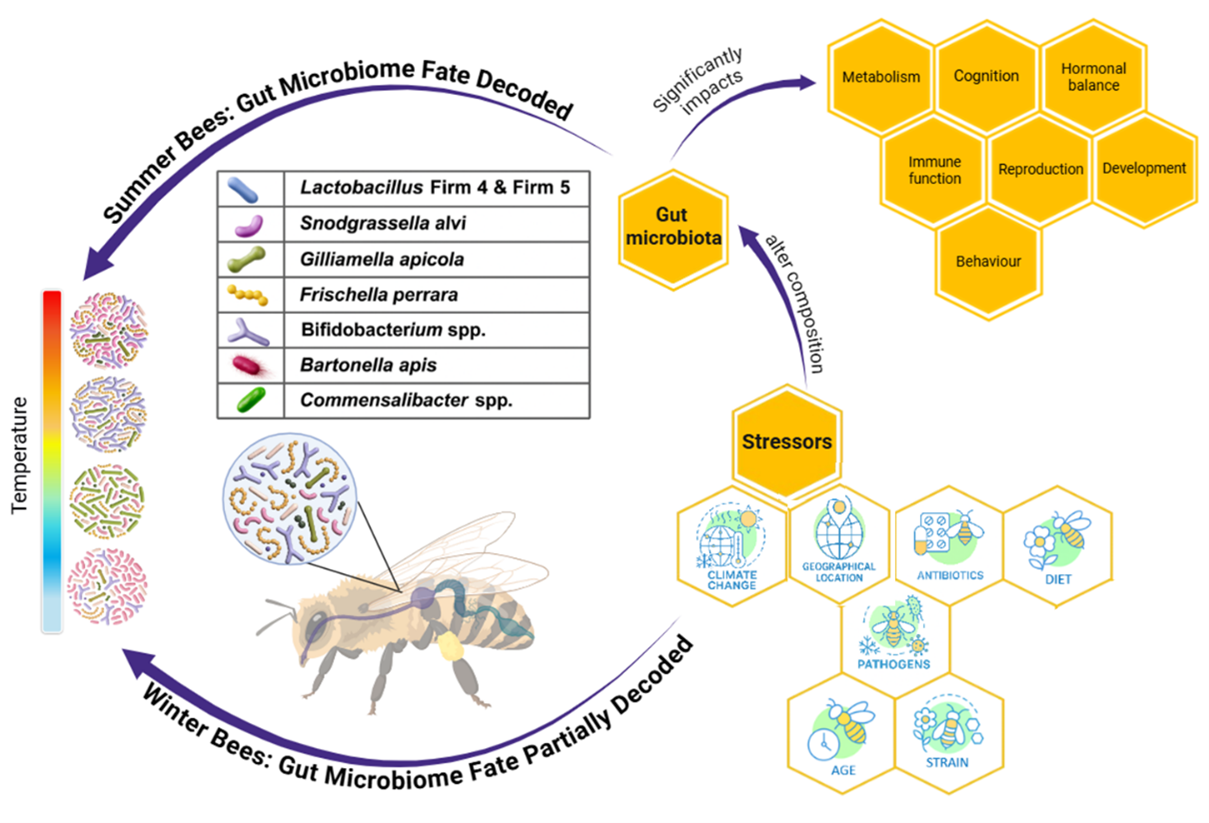

2. Functionality of the Gut Bacteria

2.1. Immune Modulation

2.2. Nutrient Utilization and Detoxification

2.3. Protection Against Pathogens

3. Microbiome Dynamics in Honey Bees Adapted to Cold Season Spells

4. Geographical and Seasonal Dynamics of the Honey Bee Gut Microbiome

5. Modulators of the Honeybee Microbiome During Overwintering

5.1. Extrinsic Stressors in Honey Bees: Implications for Overwintering Survival and Gut Microbial Shifts

5.1.1. Cold Exposure and Dietary Modulation

5.1.2. Cold Exposure and Antibiotic Stress

5.1.3. Cold Exposure and Pathogen Infestation

5.2. Intrinsic Stressors in Honey Bees: Implications for Overwintering Survival and Gut Microbial Shifts

5.2.1. Cold Stress and Honey Bee Age

5.2.2. Cold Stress and Honey Bee Strain

6. Gene Expression Under Cumulative Stress Response in Overwintering Honeybees

- How does cold-induced disruption of the gut microbiome alter immune signaling pathways and antimicrobial peptide expression, thereby influencing susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens under combined pesticide and pathogen exposure?

- To what extent does the gut microbiome contribute to metabolic reprogramming and oxidative stress resilience by modulating host gene expression related to mitochondrial function and detoxification during cold stress?

- How do combined overwintering stressors drive gut microbial dysbiosis that impacts host detoxification gene networks, and what are the downstream effects on neural health and longevity in honey bees?

| Stressor Type | Cold Stress specific or Combined | Targeted Pathways / Systems | Key Genes Affected | Expression Response | Functional Consequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Stress | Cold Stress specific | Mitochondrial metabolism, immunity | Vitellogenin,Defensin-1, Cox5a | ↑ Upregulated | Enhanced immunity, metabolic reprogramming | [37] |

| Cold Stress specific | Antifreeze protein (AFP), protein lethal (2) (I(2)efl), vitellogenin (Vg) | ↑ Upregulated | Enhanced cold resistant ability | [82] | ||

| Pathogens (DWV, bacteria) | Cold + pathogen | Cellular immune function |

Defensin-1, Hymenoptaecin, Dorsal, eater |

↑ Upregulated | Enhanced immunity | [97] |

| Antibiotics (tetracycline) | Combined with Cold | Gut microbiota, immune modulation |

Defensin-1, AMPs, Lysozyme, PGRP-LC |

↓Suppressed AMPs ↑ Detox gene variability |

Microbiome disruption, weakened immunity, impaired digestion | [72] |

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alaux, C.; Dantec, C.; Parrinello, H.; Le Conte, Y. Nutrigenomics in honey bees: digital gene expression analysis of pollen's nutritive effects on healthy and varroa-parasitized bees. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. E.; Maes, P. Social microbiota and social gland gene expression of worker honey bees by age and climate. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronstein, K. A.; Murray, K. D. Chalkbrood disease in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S20–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARS Honey Bee Health. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/br/ccd/index/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Navarro-Escalante, L.; Ashraf, A. H. M. Z.; Leonard, S. P.; Barrick, J. E. Protecting honey bees through microbiome engineering. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2025, 72, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackport, R.; Fyfe, J. C. Amplified warming of North American cold extremes linked to human-induced changes in temperature variability. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleau, N.; Bouslama, S.; Giovenazzo, P.; Derome, N. Dynamics of the honeybee (Apis mellifera) gut microbiota throughout the overwintering period in Canada. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Rosso, G.; Engel, P. Functional roles and metabolic niches in the honey bee gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 43, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, Z. Climate Change and Bees: The Effects of a changing planet. The Best Bees Company. Available online: https://bestbees.com/climate-change-and-bees/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Brar, G.; Ngor, L.; McFrederick, Q. S.; Torson, A. S.; Rajamohan, A.; Rinehart, J.; Singh, P.; Bowsher, J. H. High abundance of lactobacilli in the gut microbiome of honey bees during winter. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochet, S.; Quinn, A.; Mars, R. A.; Neuschwander, N.; Sauer, U.; Engel, P. Niche partitioning facilitates coexistence of closely related honey bee gut bacteria. eLife 2021, 10, e68583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodschneider, R.; Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 2010, 41, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, G. E.; Pietravalle, S.; Brown, M.; Laurenson, L.; Jones, B.; Tomkies, V.; Delaplane, K. S. Pathogens as predictors of honey bee colony strength in England and Wales. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133228. [Google Scholar]

- Butolo, N. P.; Azevedo, P.; Alencar, L. D.; Malaspina, O.; Nocelli, R. C. F. Impact of low temperatures on the immune system of honeybees. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 101, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, D. B.; Winslow, S. K.; Cloppenborg-Schmidt, K.; Baines, J. F. Quantitative microbiome profiling of honey bee (Apis mellifera) guts is predictive of winter colony loss in northern Virginia (USA). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Branchiccela, B.; Garrido, M.; Invernizzi, C.; Porrini, M.; Romero, H.; Santos, E.; Zunino, P.; Antúnez, K. Impact of nutritional stress on honeybee gut microbiota, immunity, and Nosema ceranae infection. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 80, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Branchiccela, B.; Romero, H.; Zunino, P.; Antúnez, K. Seasonal dynamics of the honey bee gut microbiota in colonies under subtropical climate. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 83, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Francis, J. A.; Pfeiffer, K. Anomalous Arctic warming linked with severe winter weather in Northern Hemisphere continents. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Pfeiffer, K.; Francis, J. A. Warm Arctic episodes linked with increased frequency of extreme winter weather in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corby-Harris, V.; Maes, P.; Anderson, K. E. The bacterial communities associated with honey bee (Apis mellifera) foragers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95056. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, S. B.; Léger, A.; Boudreau, L. H.; Pichaud, N. Overwintering in North American domesticated honeybees (Apis mellifera) causes mitochondrial reprogramming while enhancing cellular immunity. J. Exp. Biol. 2022, 225, jeb244440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, K. A. S.; Majeed, M. Z.; Sayed, S.; Yeo, K. Simulated climate warming influenced colony microclimatic conditions and gut bacterial abundance of honeybee subspecies Apis mellifera ligustica and A. mellifera sinisxinyuan. J. Apic. Sci. 2022, 66, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox-Foster, D. L.; Conlan, S.; Holmes, E. C.; Palacios, G.; Evans, J. D.; Moran, N. A.; Lipkin, W. I. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science 2007, 318, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crailsheim, K.; Stolberg, E. Influence of diet, age and colony condition upon intestinal proteolytic activity and size of the hypopharyngeal glands in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). J. Insect Physiol. 1989, 35, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, L. M.; Sadler, J. P.; Pritchard, J.; Hayward, S. A. L. Elevated CO2 impacts on plant-pollinator interactions: a systematic review and free air carbon enrichment field study. Insects 2021, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmon, A.; Desbiez, C.; Coulon, M.; Thomasson, M.; Le Conte, Y.; Alaux, C.; Vallon, J.; Moury, B. Evidence for positive selection and recombination hotspots in Deformed wing virus (DWV). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Chen, Y.; Rivera, R.; Carroll, M.; Chambers, M.; Hidalgo, G.; de Jong, E. W. Honey bee colonies provided with natural forage have lower pathogen loads and higher overwinter survival than those fed protein supplements. Apidologie 2016, 47, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Graham, H.; Ahumada, F.; Smart, M.; Ziolkowski, N. The economics of honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) management and overwintering strategies for colonies used to pollinate almonds. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 2524–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, A. G.; Toth, A. L. Feedbacks between nutrition and disease in honey bee health. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosch, C.; Manigk, A.; Streicher, T.; Tehel, A.; Paxton, R. J.; Tragust, S. The gut microbiota can provide viral tolerance in the honey bee. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, O.; Schmidt, K.; Engel, P. Immune system stimulation by the gut symbiont Frischella perrara in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 2576–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Salminen, S. Honeybees and beehives are rich sources for fructophilic lactic acid bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N. A. Functional and evolutionary insights into the simple yet specific gut microbiota of the honey bee from metagenomic analysis. Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P.; Kwong, W. K.; McFrederick, Q.; Anderson, K. E.; Barribeau, S. M.; Chandler, J. A.; Cornman, R. S.; Dainat, J.; De Miranda, J. R.; Doublet, V.; Emery, O.; Evans, J. D.; Farinelli, L.; Flenniken, M. L.; Granberg, F.; Grasis, J. A.; Gauthier, L.; Hayer, J.; Koch, H.; Dainat, B. The bee microbiome: impact on bee health and model for evolution and ecology of host-microbe interactions. mBio 2016, 7, e02164-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P.; Martinson, V. G.; Moran, N. A. Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11002–11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. D. Diverse origins of tetracycline resistance in the honey bee bacterial pathogen Paenibacillus larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2003, 83, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodschneider, R.; Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 2010, 41, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, J. R. Plant–pollinator interactions and phenological change: what can we learn about climate impacts from experiments and observations? Oikos 2015, 124, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, E. European foulbrood in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S5–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genersch, E. American foulbrood in honeybees and its causative agent, Paenibacillus larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrochategui-Ortega, J.; Muñoz-Colmenero, M.; Kovačić, M.; Filipi, J.; Puškadija, Z.; Kezić, N.; Parejo, M.; Büchler, R.; Estonba, A.; Zarraonaindia, I. A short exposure to a semi-natural habitat alleviates the honey bee hive microbial imbalance caused by agricultural stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F. J.; Rusch, D. B.; Stewart, F. J.; Mattila, H. R.; Newton, I. L. G. Saccharide breakdown and fermentation by the honey bee gut microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, A. C.; Nagar, A. E.; Mackinder, L. C. M.; Noël, L. M. J.; Hall, M. J.; Martin, S. J.; Schroeder, D. C. Deformed wing virus implicated in overwintering honeybee colony losses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7212–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D. B.; Webster, T. C. Apiculture and forestry (bees and trees). Agrofor. Syst. 1995, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, R. D.; Leonard, S. P.; Moran, N. A. Symbionts shape host innate immunity in honeybees. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20201184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S. K.; Ye, K. T.; Huang, W. F.; Ying, B. H.; Su, X.; Lin, L. H.; Li, J. H.; Chen, Y. P.; Li, J. L.; Bao, X. L.; Hu, J. Z. Influence of feeding type and Nosema ceranae infection on the gut microbiota of Apis cerana workers. mSystems 2018, 3, e00177-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, K., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., Zhou, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. C.; Fruciano, C.; Marchant, J.; Hildebrand, F.; Forslund, S.; Bork, P.; Hughes, W. O. H. The gut microbiome is associated with behavioral tasks in honey bees. Insectes Soc. 2018, 65, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, S.; Nastasa, A.; Chapman, A.; Kwong, W. K.; Foster, L. J. The honey bee gut microbiota: strategies for study and characterization. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 28, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kešnerová, L.; Emery, O.; Troilo, M.; Liberti, J.; Erkosar, B.; Engel, P. Gut microbiota structure differs between honeybees in winter and summer. ISME J. 2020, 14, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kešnerová, L.; Mars, R. A. T.; Ellegaard, K. M.; Troilo, M.; Sauer, U.; Engel, P. Disentangling metabolic functions of bacteria in the honey bee gut. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2003467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W. K.; Medina, L. A.; Koch, H.; Sing, K.-W.; Soh, E. J. Y.; Ascher, J. S.; Jaffé, R.; Moran, N. A. Dynamic microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1600513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killer, J.; Dubná, S.; Sedláček, I.; Švec, P. Lactobacillus apis sp. nov., from the stomach of honeybees (Apis mellifera), having an in vitro inhibitory effect on the causative agents of American and European foulbrood. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 64, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W. K.; Moran, N. A. Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, W. K.; Mancenido, A. L.; Moran, N. A. Immune system stimulation by the native gut microbiota of honey bees. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, H.; Duan, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Zheng, H. Specific strains of honeybee gut Lactobacillus stimulate host immune system to protect against pathogenic Hafnia alvei. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01896-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Maccaro, J.; McFrederick, Q. S.; Nieh, J. C. Exploring the interactions between Nosema ceranae infection and the honey bee gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Conte, Y.; Navajas, M. Climate change: impact on honey bee populations and diseases. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2008, 27, 499–510. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F. J.; Miller, K. I.; McKinlay, J. B.; Newton, I. L. G. Differential carbohydrate utilization and organic acid production by honey bee symbionts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, X. Community dynamics in structure and function of honey bee gut bacteria in response to winter dietary shift. mBio 2022, 13, e01131-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. H.; Evans, J. D.; Li, W. F.; Zhao, Y. Z.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Huang, S. K.; Li, Z. G.; Hamilton, M.; Chen, Y. P. New evidence showing that the destruction of gut bacteria by antibiotic treatment could increase the honey bee’s vulnerability to Nosema infection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zheng, M.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Niu, Q.; Ji, T. Possible interactions between gut microbiome and division of labor in honey bees. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smutin, D.; Lebedev, E.; Selitskiy, M.; Panyushev, N.; Adonin, L. Micro”bee”ota: honey bee normal microbiota as a part of superorganism. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, P. W.; Floyd, A. S.; Mott, B. M.; Anderson, K. E. Overwintering honey bee colonies: effect of worker age and climate on the hindgut microbiota. Insects 2021, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, P. W.; Rodrigues, P. A. P.; Oliver, R.; Mott, B. M.; Anderson, K. E. Diet-related gut bacterial dysbiosis correlates with impaired development, increased mortality and Nosema disease in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 5439–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, D. E.; O'Toole, P. W. A review of diet and foraged pollen interactions with the honeybee gut microbiome. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, G.; Salmela, H.; Freitak, D.; Amdam, G. Social immunity in honey bees: royal jelly as a vehicle in transferring bacterial pathogen fragments between nestmates. J. Exp. Biol. 2021, 224, jeb231076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott, J.; Craze, P. G.; Waser, N. M.; Price, M. V. Global warming and the disruption of plant-pollinator interactions. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minaud, É.; Rebaudo, F.; Davidson, P.; Hatjina, F.; Hotho, A.; Mainardi, G.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Vardakas, P.; Verrier, E.; Requier, F. How stressors disrupt honey bee biological traits and overwintering mechanisms. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockler, B. K.; Kwong, W. K.; Moran, N. A.; Koch, H. Microbiome structure influences infection by the parasite Crithidia bombi in bumble bees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02335-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, A.; Olofsson, T. C. The lactic acid bacteria involved in the production of bee pollen and bee bread. J. Apic. Res. 2009, 48, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelao, P.; Borba, R. S.; Ricigliano, V.; Spivak, M.; Simone-Finstrom, M. Honeybee microbiome is stabilized in the presence of propolis. Biol. Lett. 2020, 16, 20200003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-H.; Jung, M.-J.; Kim, P. S.; Bae, J.-W. Social status shapes the bacterial and fungal gut communities of the honey bee. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsopoulou, M. E.; McMahon, D. P.; Doublet, V.; Frey, E.; Rosenkranz, P.; Paxton, R. J. The virulent, emerging genotype B of Deformed Wing Virus is closely linked to the overwinter loss of honeybee workers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Elzen, P. J. The biology of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): gaps in our knowledge of an invasive species. Apidologie 2004, 35, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C. D. The thermology of wintering honey bee colonies. Technical Bulletins. 1971. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/uerstb/171857.html.

- Palacios, S.; Añon, G.; Arredondo, D.; Alarcón, M.; Zunino, P.; Campá, J.; Antúnez, K. Long-term monitoring of Paenibacillus larvae, causative agent of American Foulbrood, in Uruguay. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2024, 207, 108186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, M.; Békési, L.; Farkas, R.; Makrai, L.; Judge, M. F.; Maróti, G.; Tőzsér, D.; Solymosi, N. Natural diversity of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) gut bacteriome in various climatic and seasonal states. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, S. G.; Biesmeijer, J. C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W. E. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J. E.; Carver, Z.; Leonard, S. P.; Moran, N. A. Field-realistic tylosin exposure impacts honey bee microbiota and pathogen susceptibility, which is ameliorated by native gut probiotics. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00103-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J. E.; Lau, P.; Rangel, J.; Arnott, R.; De Jong, T.; Moran, N. A. The microbiome and gene expression of honey bee workers are affected by a diet containing pollen substitutes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, B. Changes in cold tolerance during the overwintering period in Apis mellifera ligustica. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, K.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Pruett, M.; Jones, V. P.; Corby-Harris, V.; Pireaud, J.; Curry, R.; Hopkins, B.; Northfield, T. D. Warmer autumns and winters could reduce honey bee overwintering survival with potential risks for pollination services. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymann, K.; Coon, K. L.; Shaffer, Z.; Salisbury, S.; Moran, N. A. Pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens strains in honey bees. mBio 2018, 9, e01649-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymann, K.; Shaffer, Z.; Moran, N. A. Antibiotic exposure perturbs the gut microbiota and elevates mortality in honeybees. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requier, F.; Leyton, M. S.; Morales, C. L.; Garibaldi, L. A.; Giacobino, A.; Porrini, M. P.; Rosso-Londoño, J. M.; Velarde, R. A.; Aignasse, A.; Aldea-Sánchez, P.; Allasino, M. L.; Arredondo, D.; Audisio, C.; Cagnolo, N. B.; Basualdo, M.; Branchiccela, B.; Calderón, R. A.; Castelli, L.; Castilhos, D.; Antúnez, K. First large-scale study reveals important losses of managed honey bee and stingless bee colonies in Latin America. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricigliano, V. A.; Anderson, K. E. Probing the honey bee diet-microbiota-host axis using pollen restriction and organic acid feeding. Insects 2020, 11, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, P.; Aumeier, P.; Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S96–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J. A.; Carroll, M. J.; Meikle, W. G.; Anderson, K. E.; McFrederick, Q. S. Longitudinal effects of supplemental forage on the honey bee (Apis mellifera) microbiota and inter- and intra-colony variability. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, V. G.; Danforth, B.; Minckley, R. L.; Rueppell, O.; Tingek, S.; Moran, N. A. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S. How climate change impacts winter weather. TIME. 13 February 2025. Available online: https://time.com/7222241/how-are-our-winters-impacted-by-climate-change.

- Simone-Finstrom, M.; Li-Byarlay, H.; Huang, M. H.; Strand, M. K.; Rueppell, O.; Tarpy, D. R. Migratory management and environmental conditions affect lifespan and oxidative stress in honey bees. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Fang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Cold stress reshapes the honey bee gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 832762. [Google Scholar]

- Soroye, P.; Newbold, T.; Kerr, J. Climate change contributes to widespread declines among bumble bees across continents. Science 2020, 367, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, M. I.; Motta, E. V. S.; Gattu, T.; Martinez, D.; Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota protects bees from invasion by a bacterial pathogen. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00394-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhauer, N.; vanEngelsdorp, D.; Saegerman, C. Prioritizing changes in management practices associated with reduced winter honey bee colony losses for US beekeepers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 753, 141629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, N.; Corona, M.; Neumann, P.; Dainat, B. Overwintering is associated with reduced expression of immune genes and higher susceptibility to virus infection in honey bees. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, A.; Forsgren, E.; Fries, I.; Paxton, R. J.; Flaberg, E.; Szekely, L.; Olofsson, T. C. Symbionts as major modulators of insect health: lactic acid bacteria and honeybees. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Xu, B. The different dietary sugars modulate the composition of the gut microbiota in honeybee during overwintering. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. R.; Swale, D. R.; Anderson, T. D. Comparative effects of technical-grade and formulated chlorantraniliprole on the survivorship and locomotor activity of the honey bee, Apis mellifera (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2582–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, A.; Huang, S. K.; Evans, J. D.; Cook, S. C.; Palmer-Young, E.; Chen, Y. P. Mediating a host cell signaling pathway linked to overwinter mortality offers a promising therapeutic approach for improving bee health. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 53, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C. M. A. P.; Harris, H. M. B.; Mattarelli, P. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Nishida, A.; Kwong, W. K.; Koch, H.; Engel, P.; Steele, M. I.; Moran, N. A. Metabolism of toxic sugars by strains of the bee gut symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio 2016, 7, e01326-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Nishida, A.; Kwong, W. K.; Koch, H.; Engel, P.; Steele, M. I.; Moran, N. A. Metabolism of toxic sugars by strains of the bee gut symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio 2016, 7, e01326-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Powell, J. E.; Steele, M. I.; Dietrich, C.; Moran, N. A. Honeybee gut microbiota promotes host weight gain via bacterial metabolism and hormonal signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114, 4775–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Steele, M. I.; Leonard, S. P.; Motta, E. V. S.; Moran, N. A. Honey bees as models for gut microbiota research. Lab Anim. 2018, 47, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor/ Stress | Microbial Changes Observed | Core Genera Affected | Mechanism/Effect | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosema ceranae infection | Decrease in microbial diversity | ↓ Lactobacillus ↑ Snodgrassella |

Gut dysbiosis, weakened immunity | [46,57] |

| Hafnia alvei infection | Strain-specific protection against pathogen | Gilliamella apicola W8136, Lactobacillus apis W8172 (effective strains) | Certain strains help clear H. alvei infection; others ineffective | [56] |

| Cold Stress (Overwintering) | Reduced diversity, altered composition | ↑ Bartonella ↓ Commensalibacter |

Lower metabolism, limited foraging | [50,93] |

| Stable detection of Gilliamella, Bartonella, Snodgrassella, Lactobacillus, Frischella, Commensalibacter, and Bifidobacterium. | ↑Bartonella, and Bifidobacterium and then decreased in winter honey bees | Host metabolism and may affect the storage of energy | [10] | |

| Hive condition, i.e., winter survival or failure. | Lower microbial abundance and altered composition in failed hives | ↓ Commensalibacter ↓ Snodgrassella in non-surviving hives |

Microbial abundance and beta diversity strongly linked to winter survival | [15] |

| Environmental habitat (Anthropization) | ↑ Pantoea and Arsenophonus in agricultural ↑ Lactobacillus Commensalibacter and Snodgrasella in semi-natural |

Enviromental -linked microbiota shifts | [41] | |

| Overwintering climate (warm vs. cold) and worker age affect | In warm climates, worker bees exhibited reduced longevity and increased fungal abundance in the hindgut, along with shifts in bacterial communities. Conversely, Cold overwintering maintained a stable microbiota and longer worker lifespan. | ↑ fungi ↑Gilliamella spp |

Overwintering conditions have a significant influence on the gut microbiome and the health of honey bee colonies. Cold indoor environments may support microbiota stability and enhance colony survival during winter | [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).