Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tested Compositions and Additives

2.2. Determination of Interfacial Tension

2.3. Determination of the Wetting Contact Angle

- Preparation of synthetic oil, consisting of 50% deasphalted crude oil and 50% deposits of heavy components with the following composition: 22.48% asphaltenes, 11.40% resins, 18.02% paraffins, and 48.10% petroleum residue – followed by normalization, which involved thermostating at 90 °C for 4 hours;

- Thorough grinding in a porcelain mortar of an equal amount of disaggregated core and synthetic oil until a homogeneous wax-like mass was obtained;

- Placing the wax-like mass into a hand press and molding a pellet with a diameter of 20 mm and a thickness of 3 mm.

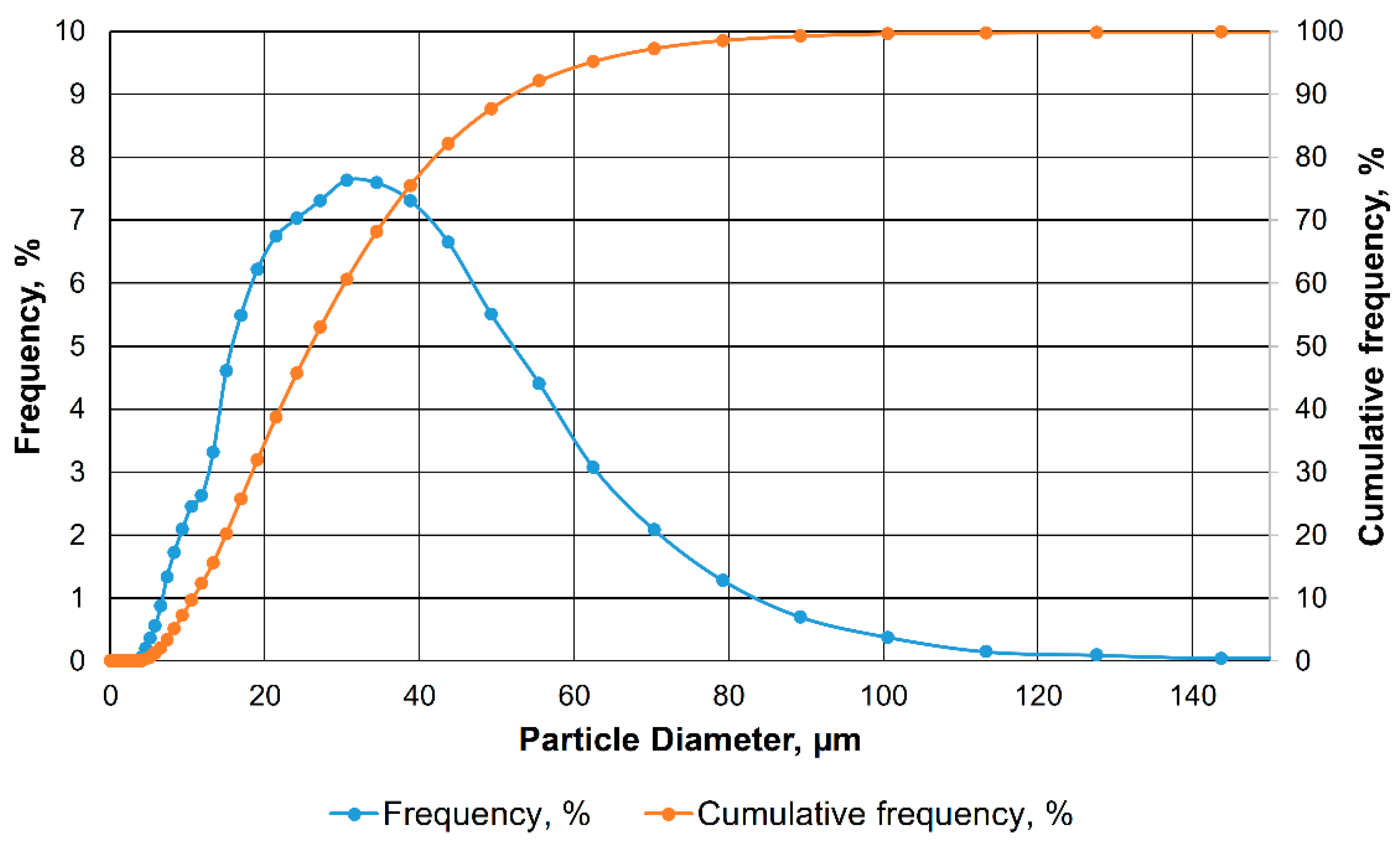

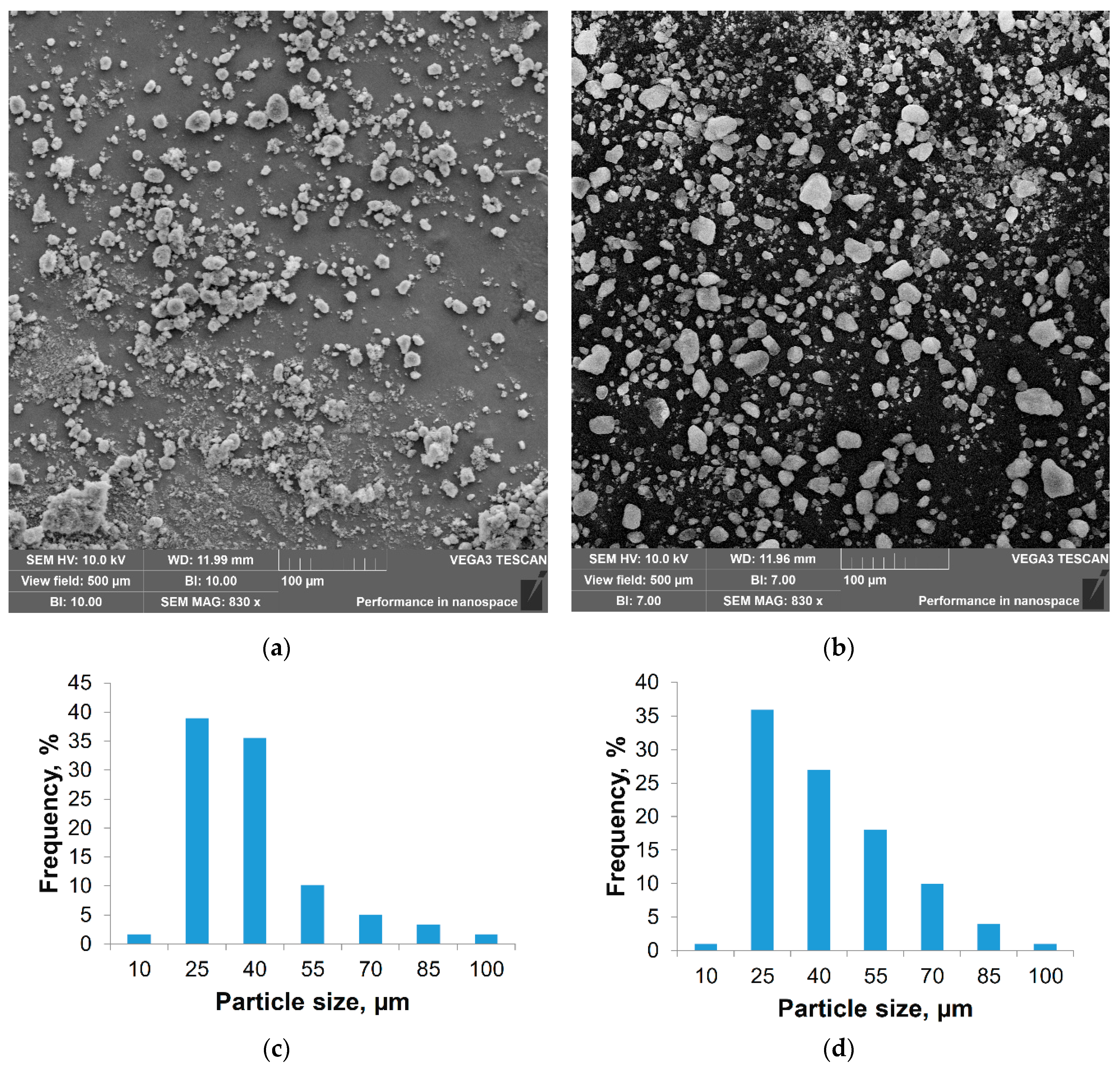

2.4. Determination of Particle Size

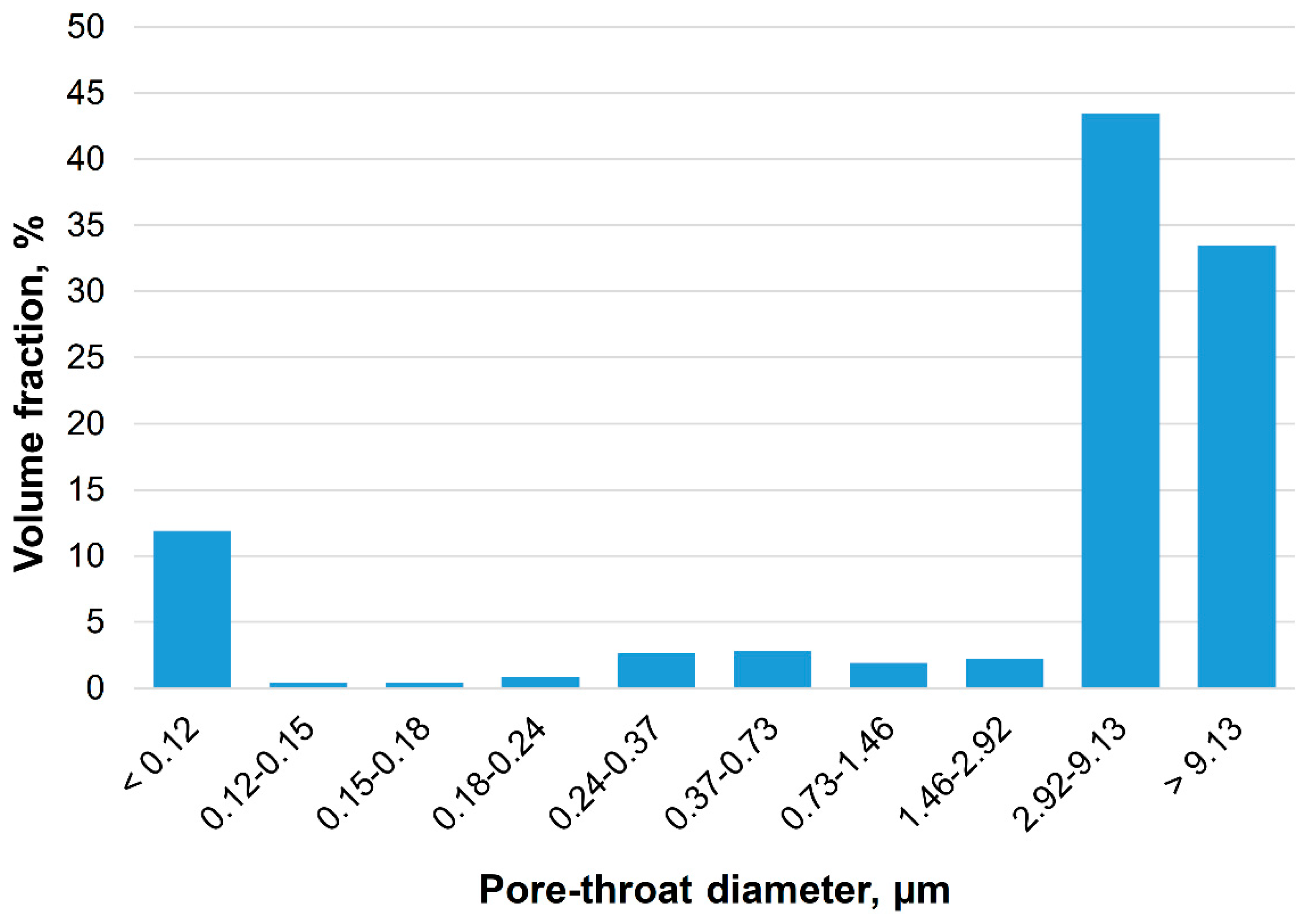

2.5. Determination of Pore Size Distribution

2.6. Determination of Sedimentation Stability of Colloidal Solutions

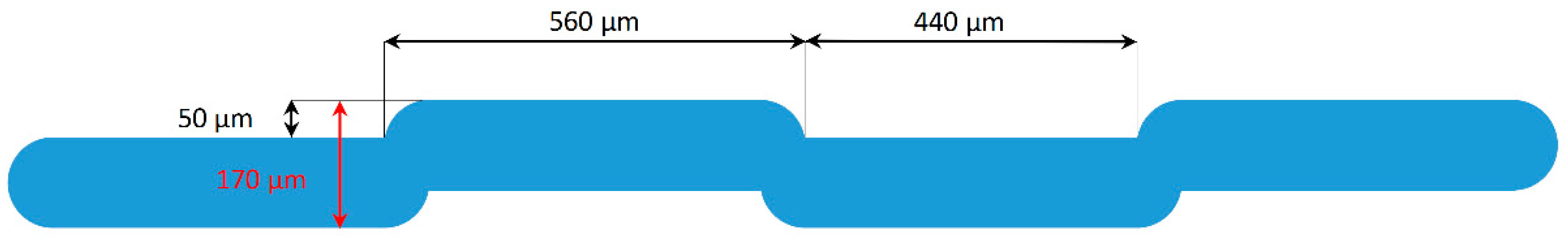

2.7. Methodology of Filtration Studies

2.8. Qualitative Determination of Surfactants Adsorbed on Nanoparticle Aggregate Surfaces

2.9. Electron Microscopy for Determining the Size of Nanoparticle Aggregates with Surfactants

3. Results and Discussion

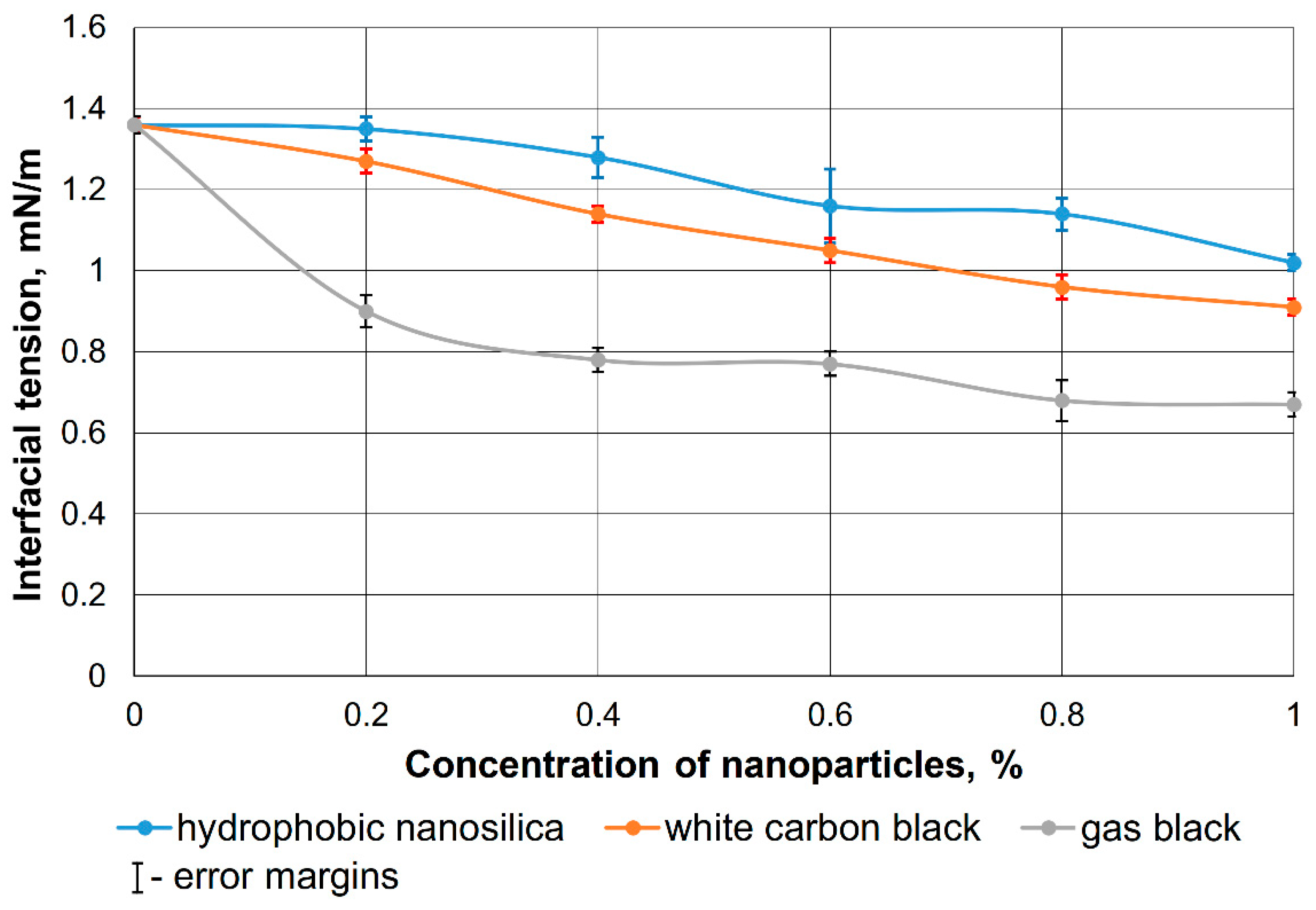

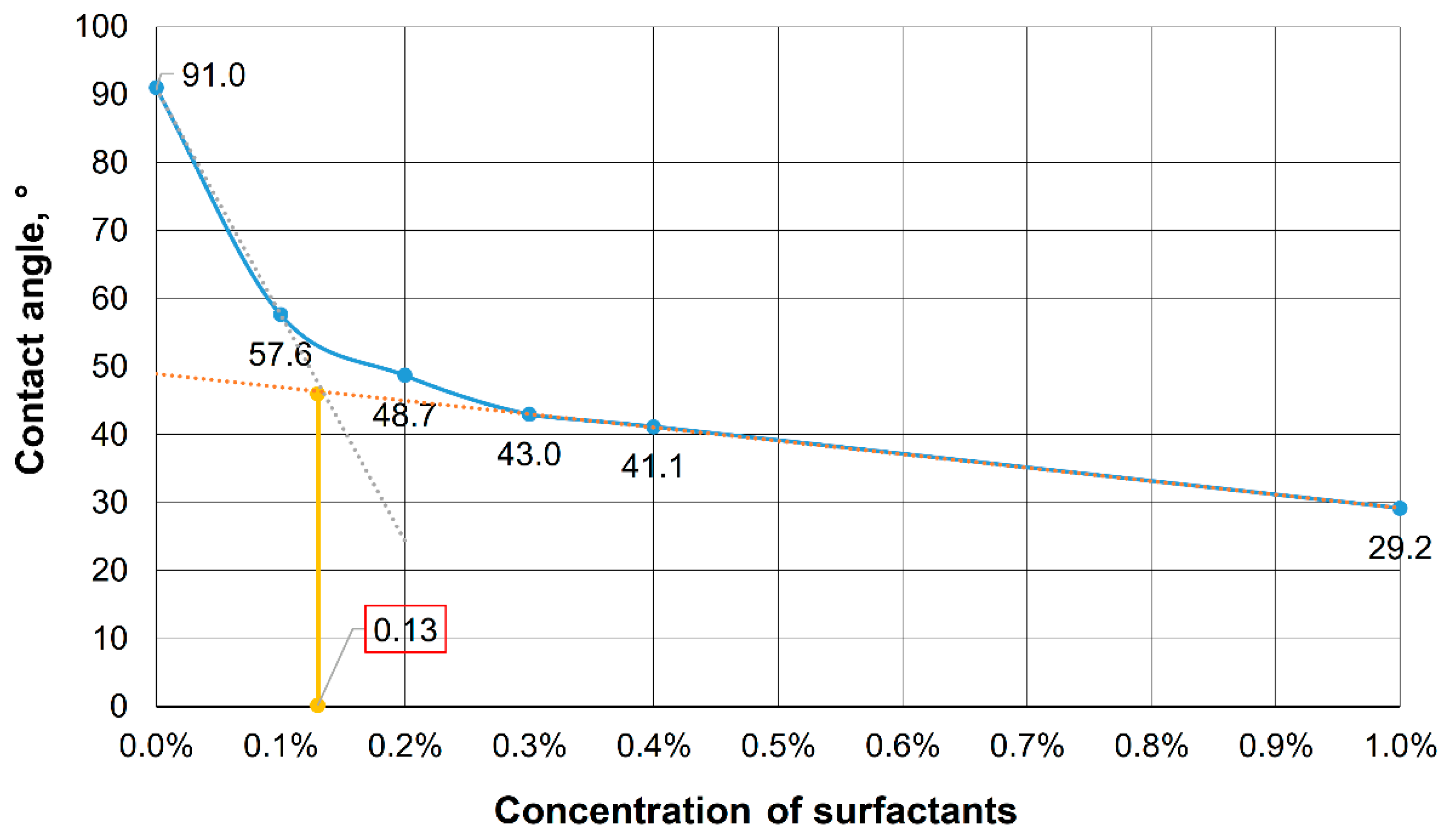

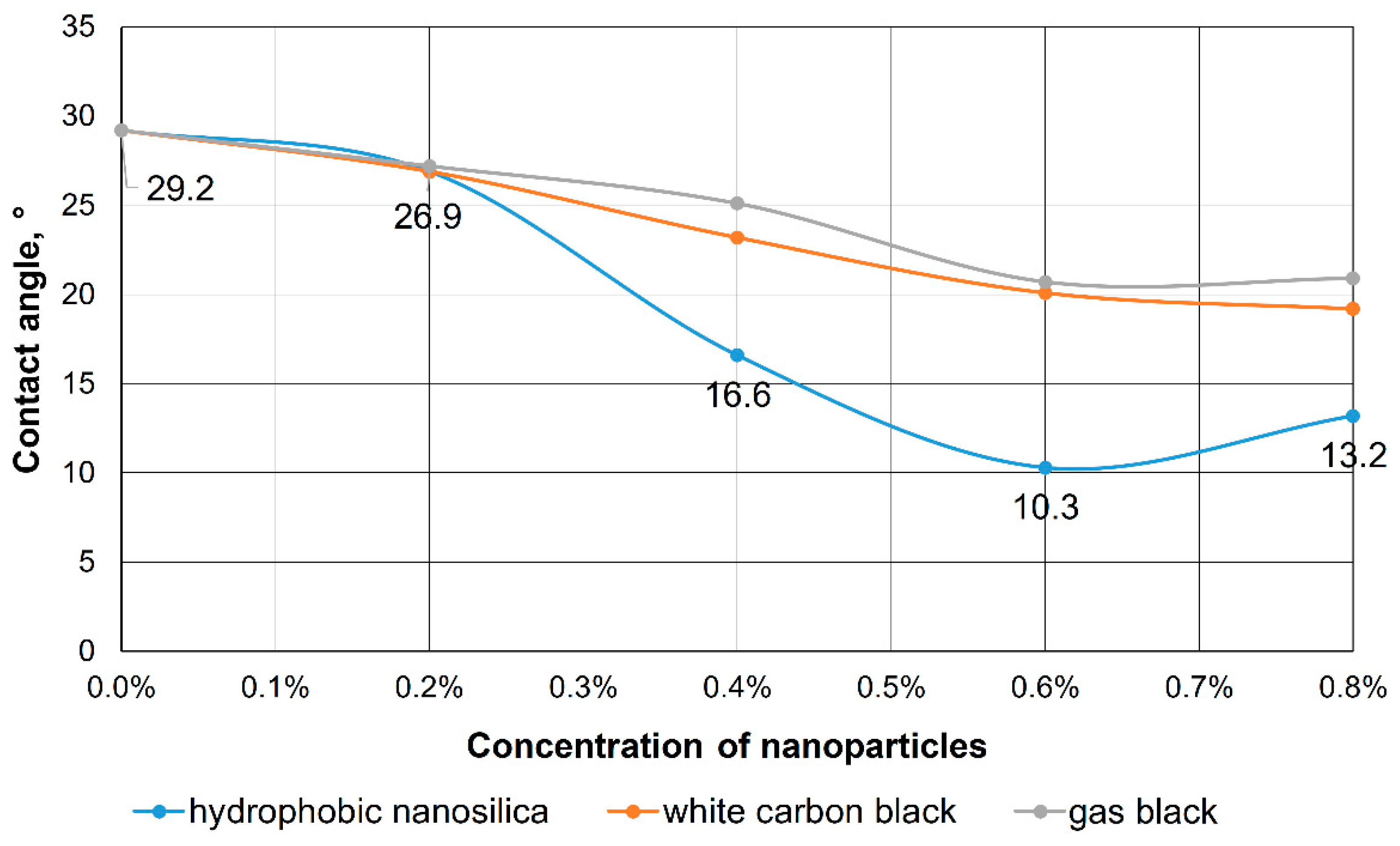

3.1. Justification of the Surfactant-Nanoparticle Composition

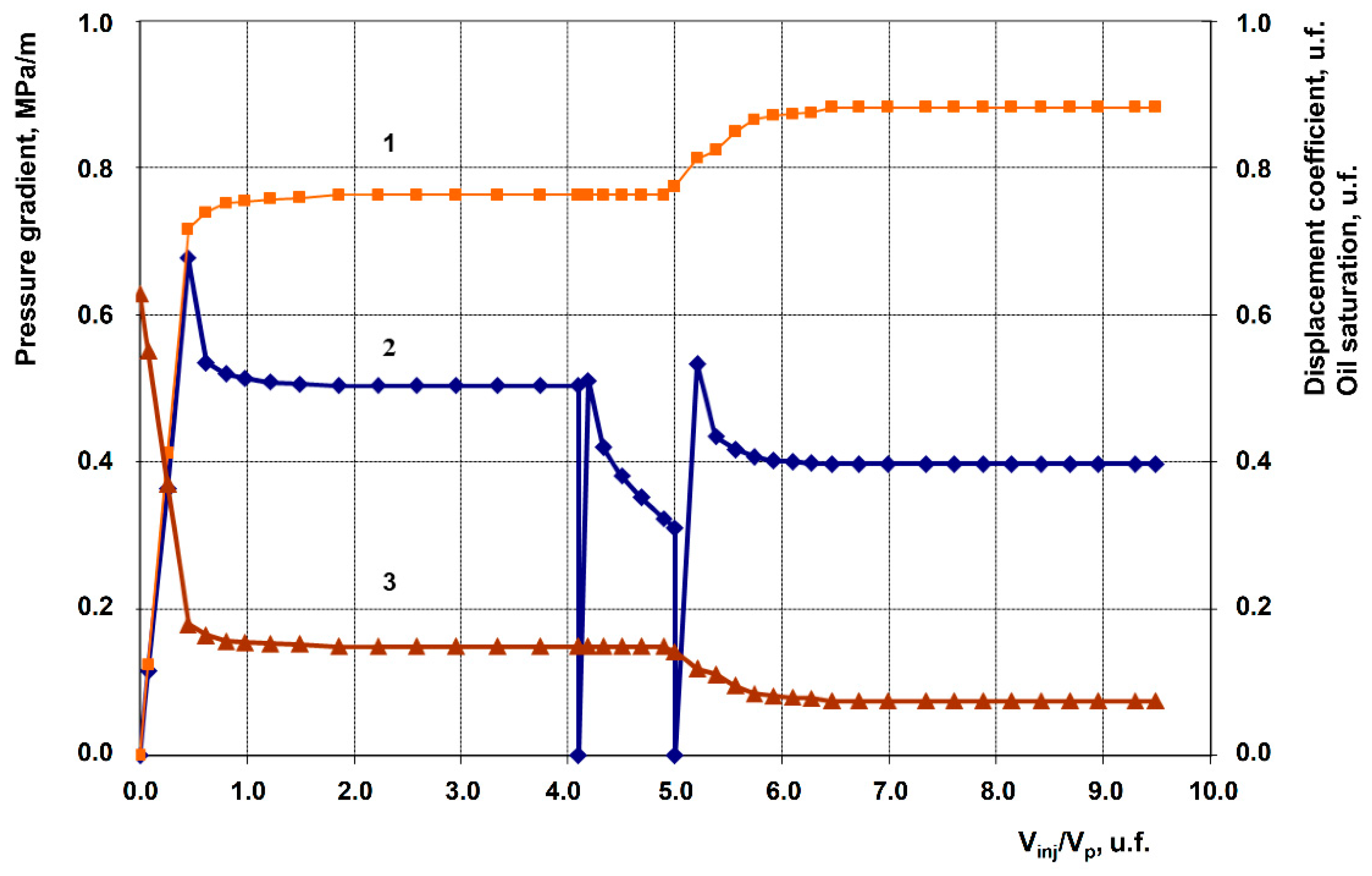

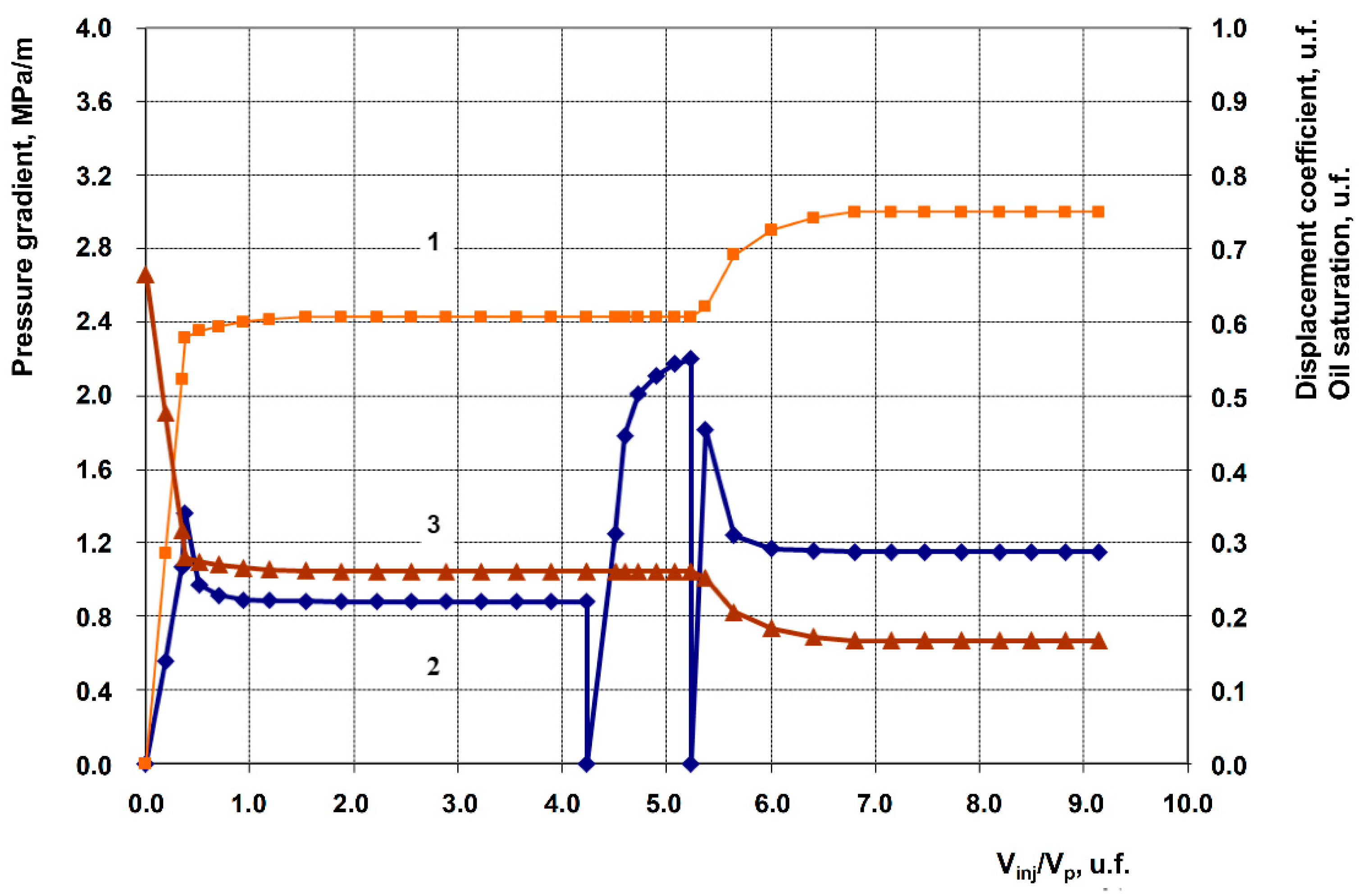

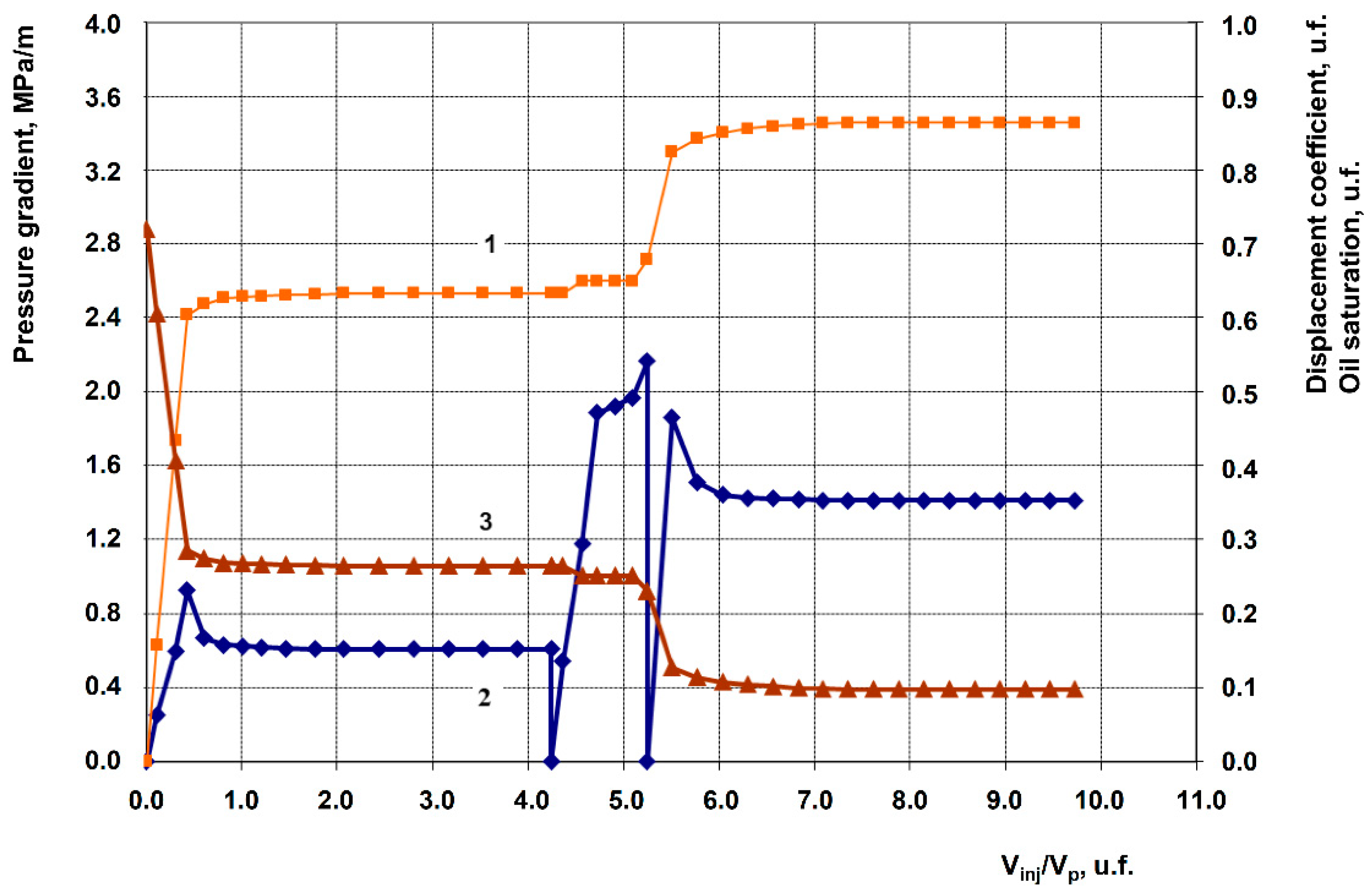

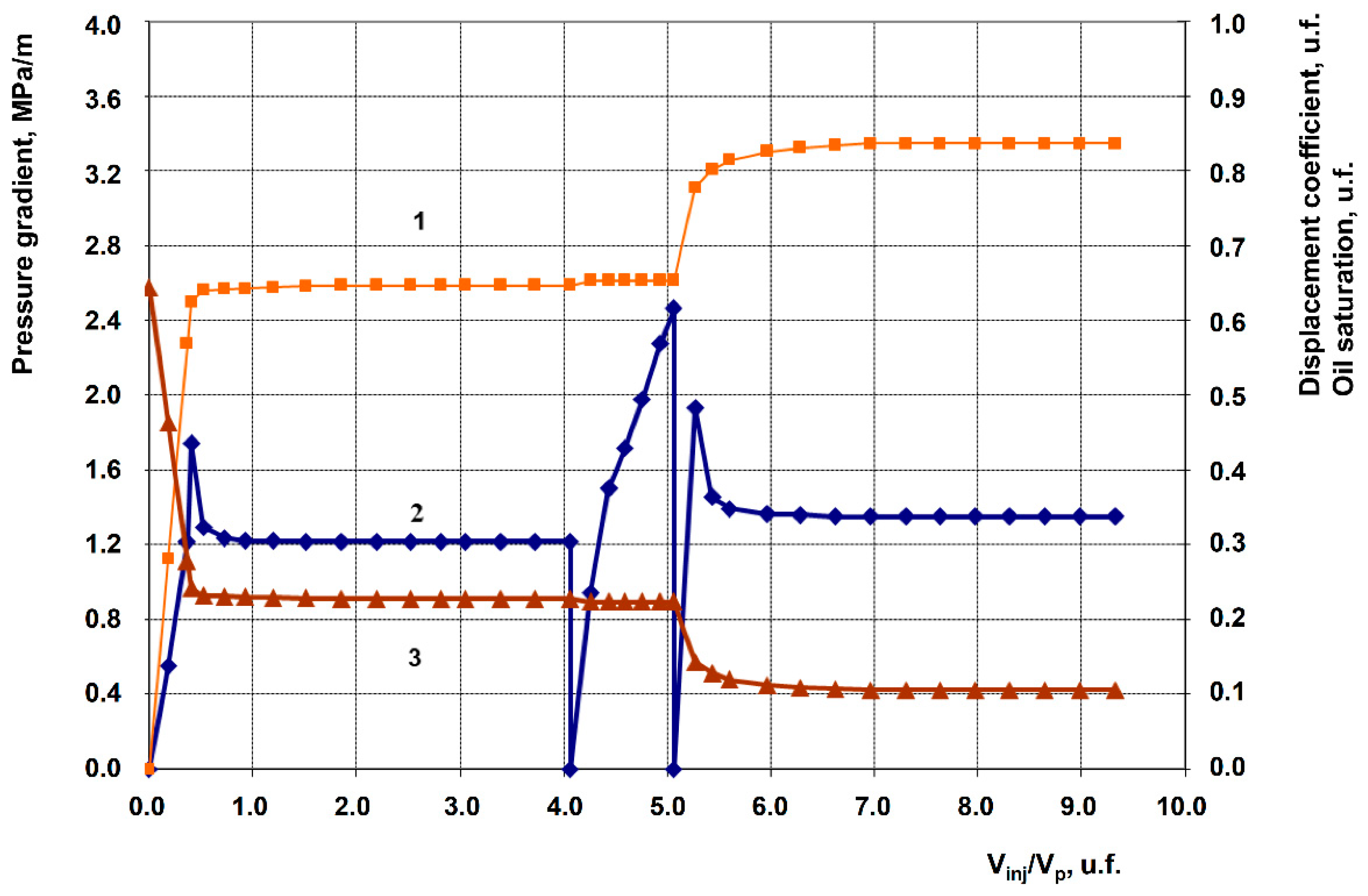

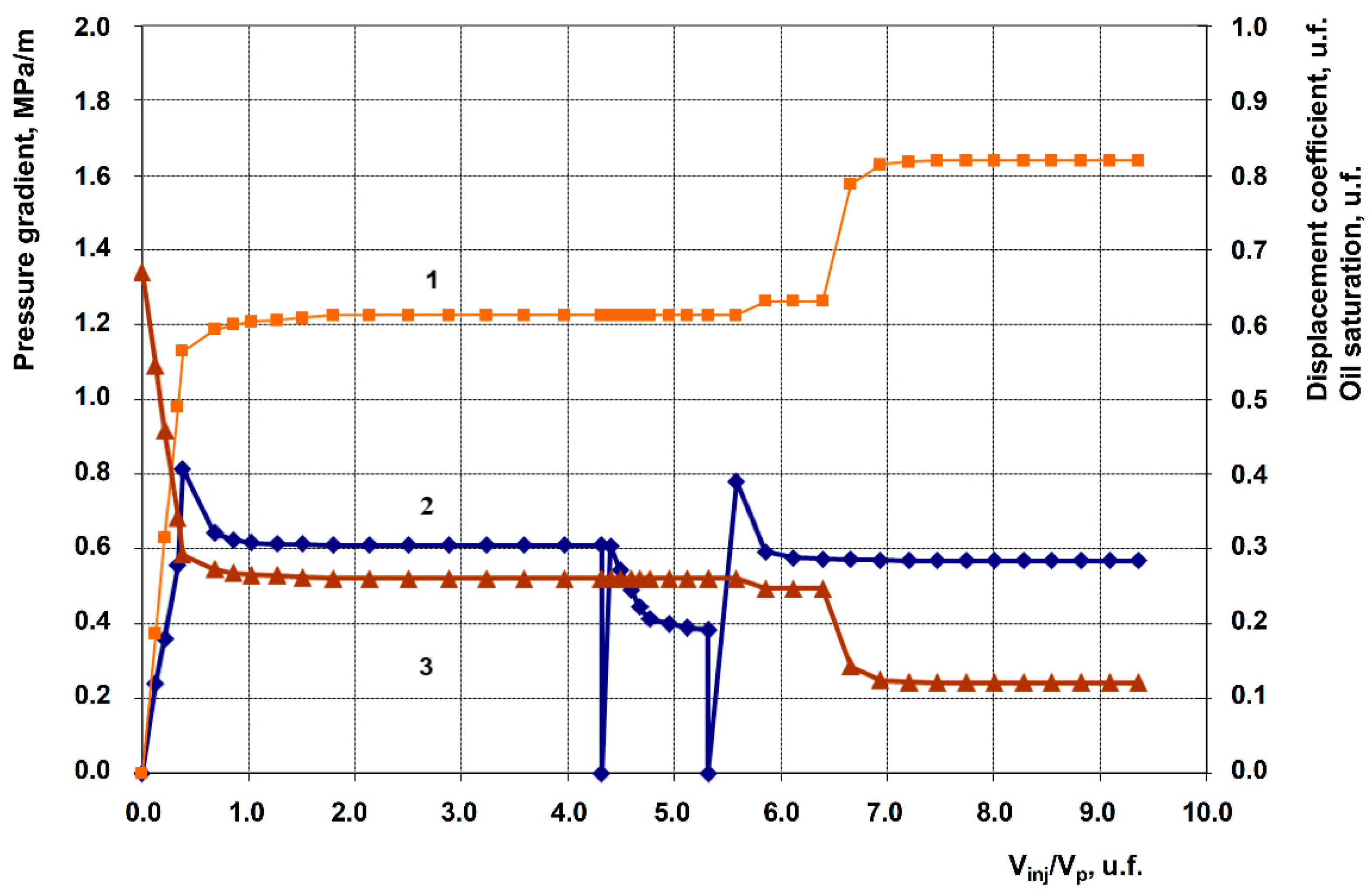

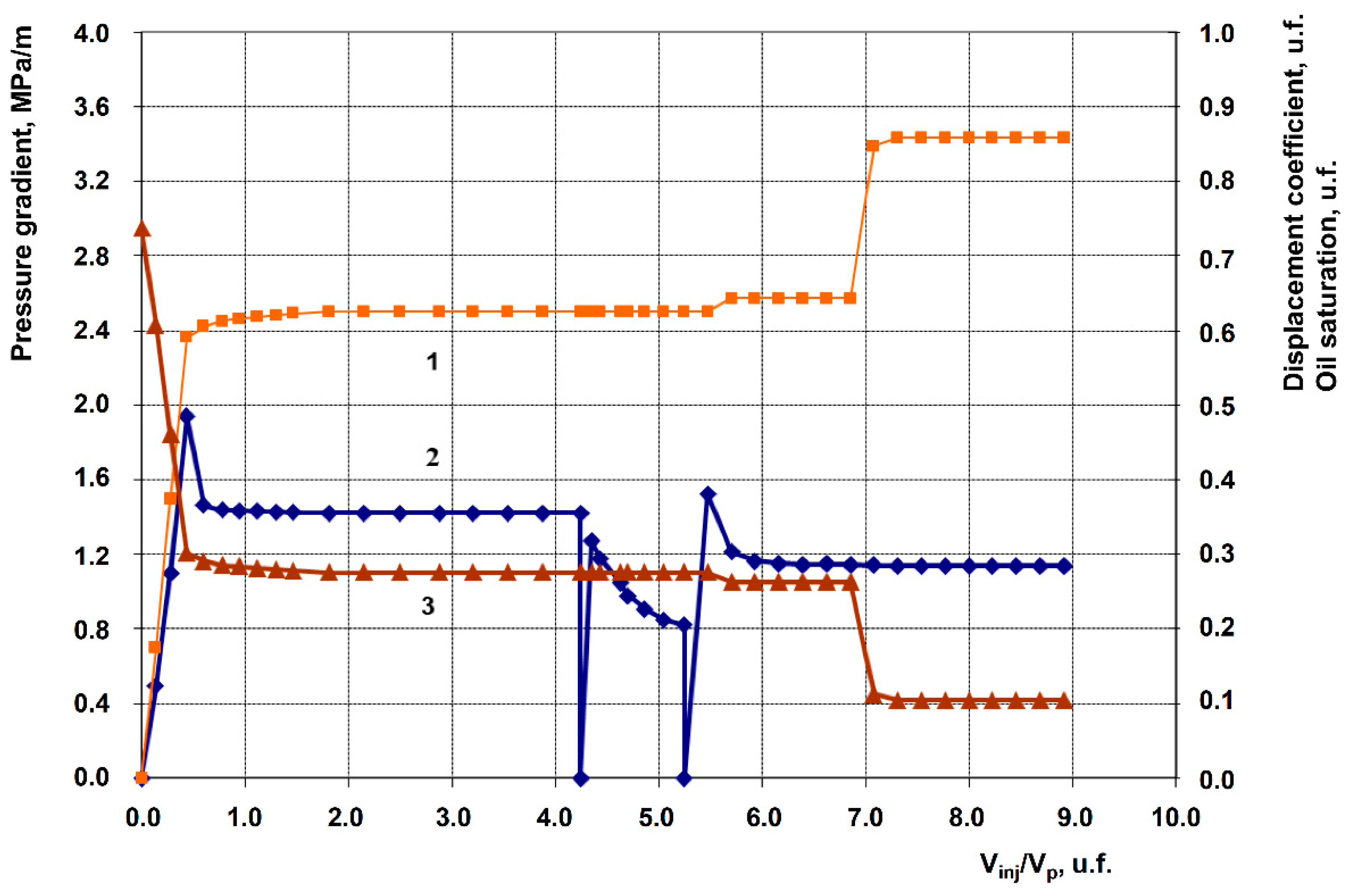

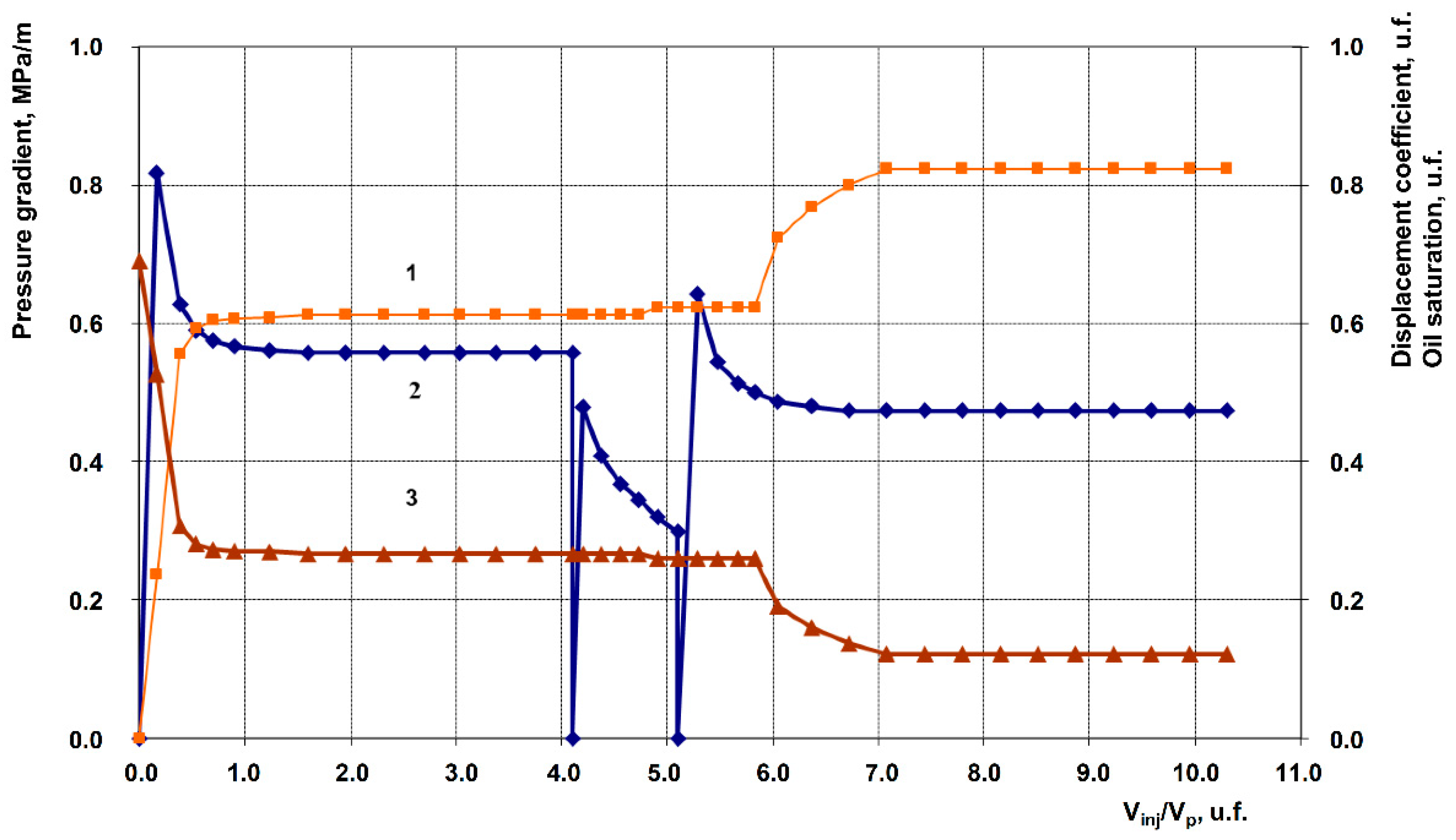

3.2. Description of Filtration Experiments

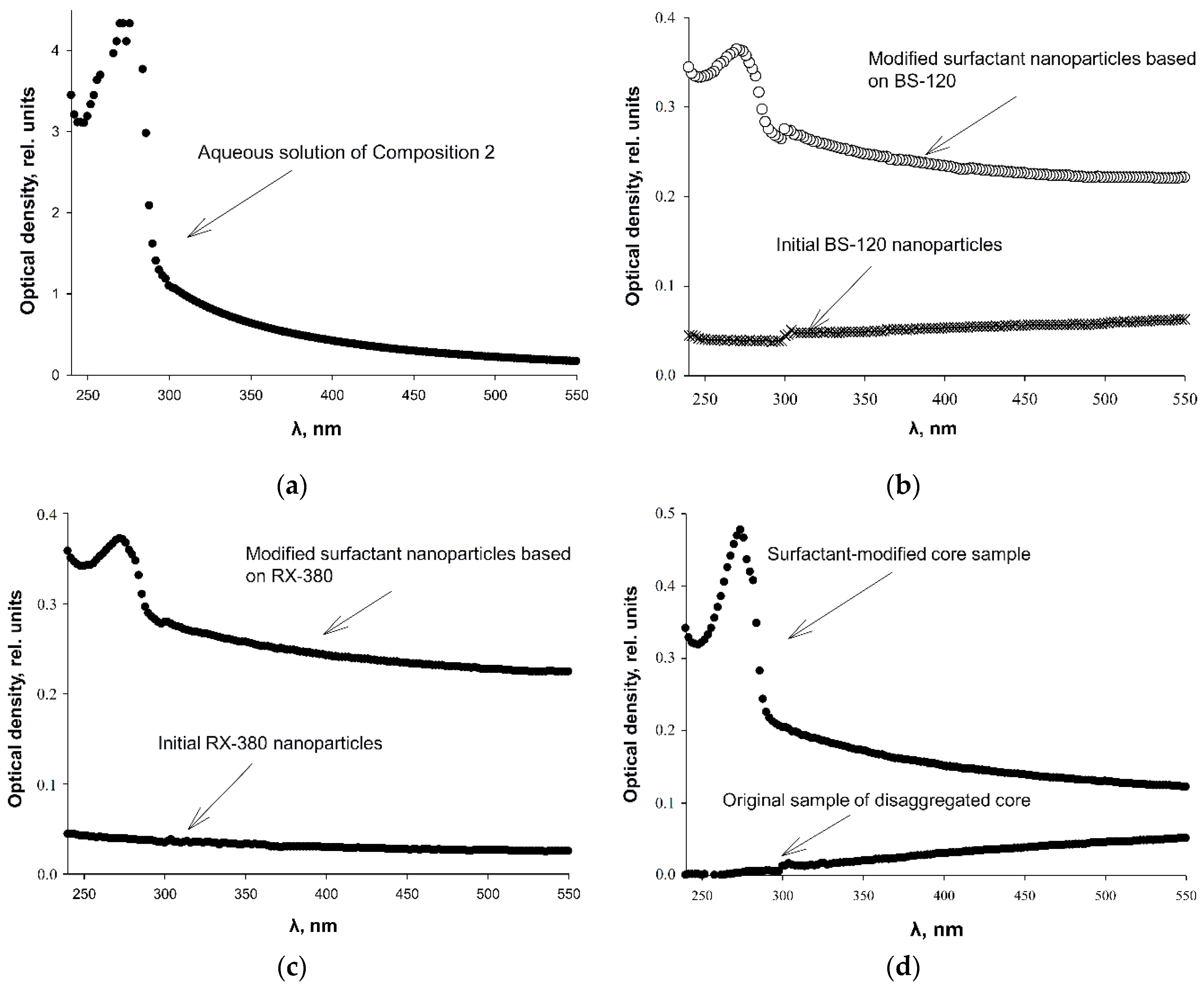

3.3. Determination of Comparative Adsorption of Surfactant Components on Nano-particle Surfaces by UV Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NS | nonionic surfactant |

| AS | anionic surfactant |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| SMLS | static multiple light scattering |

| TSI | Turbiscan Stability Index |

| PV | pore volume |

| ARPD | asphaltene-resin-paraffin deposits |

| CMC | critical micelle concentration |

References

- Alsaba, M.T.; Al Dushaishi, M.F.; Abbas, A.K. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticles Applications in the Oil and Gas Industry. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 2020, 10, 1389–1399. [CrossRef]

- Hajiabadi, S.H.; Aghaei, H.; Kalateh-Aghamohammadi, M.; Sanati, A.; Kazemi-Beydokhti, A.; Esmaeilzadeh, F. A Comprehensive Empirical, Analytical and Tomographic Investigation on Rheology and Formation Damage Behavior of a Novel Nano-Modified Invert Emulsion Drilling Fluid. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 181, 106257. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Raval, A.; Chandra, S.; Shah, M.; Sircar, A. A Comprehensive Review of the Application of Nano-Silica in Oil Well Cementing. Petroleum 2020, 6, 123–129. [CrossRef]

- Sriram, S.; Kumar, A. Separation of Oil-Water via Porous PMMA/SiO2 Nanoparticles Superhydrophobic Surface. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 563, 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Torsæter, O. Application of Nanoparticles for Oil Recovery. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1063. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, K.C.B.; Densy Dos Santos Francisco, A.; Moreira, M.P.; Nascimento, R.S.V.; Grasseschi, D. Advancements in Surfactant Carriers for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 36874–36903. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, A.A. Dynamic Modelling and Experimental Evaluation of Nanoparticles Application in Surfactant Enhanced Oil Recovery. PhD Thesis, Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology: Moscow, Russia, 2020.

- Sharma, K.P.; Aswal, V.K.; Kumaraswamy, G. Adsorption of Nonionic Surfactant on Silica Nanoparticles: Structure and Resultant Interparticle Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 10986–10994. [CrossRef]

- Zargartalebi, M.; Kharrat, R.; Barati, N. Enhancement of Surfactant Flooding Performance by the Use of Silica Nanoparticles. Fuel 2015, 143, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Alhassawi, H.; Romero-Zerón, L. New Surfactant Delivery System for Controlling Surfactant Adsorption onto Solid Surfaces. Part I: Static Adsorption Tests. Can J Chem Eng 2015, 93, 1188–1193. [CrossRef]

- Nourafkan, E.; Hu, Z.; Wen, D. Nanoparticle-Enabled Delivery of Surfactants in Porous Media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 519, 44–57. [CrossRef]

- Amirianshoja, T.; Junin, R.; Kamal Idris, A.; Rahmani, O. A Comparative Study of Surfactant Adsorption by Clay Minerals. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 101, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, M.; Barnee, S.H.R.; Shiau, B.-J.; Harwell, J.H. Improved Oil Recovery by Reducing Surfactant Adsorption with Polyelectrolyte in High Saline Brine. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 498, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Wang, Q.M.; Xu, Z.S.; Guo, Z.D.; Sun, H.Q.; Cao, X.L.; Qiao, Q. Advances in Polymer Flooding and Alkaline/Surfactant/Polymer Processes as Developed and Applied in the People’s Republic of China. J. Pet. Technol. 2006, 58, 84–89. [CrossRef]

- Islam, R. Economically and Environmentally Sustainable Enhanced Oil Recovery; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; 816 p, ISBN 978-1-119-47909-3.

- Pereira, M.L.D.O.; Maia, K.C.B.; Silva, W.C.; Leite, A.C.; Francisco, A.D.D.S.; Vasconcelos, T.L.; Nascimento, R.S.V.; Grasseschi, D. Fe3 O4 Nanoparticles as Surfactant Carriers for Enhanced Oil Recovery and Scale Prevention. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 5762–5772. [CrossRef]

- Rosestolato, J.C.S.; Pérez-Gramatges, A.; Lachter, E.R.; Nascimento, R.S.V. Lipid Nanostructures as Surfactant Carriers for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Fuel 2019, 239, 403–412. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Dai, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, M.; He, L.; Jiao, B. Reducing Surfactant Adsorption on Rock by Silica Nanoparticles for Enhanced Oil Recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 153, 283–287. [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, O.; Abushaikha, A.S. The Use of Surfactants in Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review of Recent Advances. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 3150–3178. [CrossRef]

- Almahfood, M.; Bai, B. The Synergistic Effects of Nanoparticle-Surfactant Nanofluids in EOR Applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 171, 196–210. [CrossRef]

- Eltoum, H.; Yang, Y.-L.; Hou, J.-R. The Effect of Nanoparticles on Reservoir Wettability Alteration: A Critical Review. Pet. Sci. 2021, 18, 136–153. [CrossRef]

- Sircar, A.; Rayavarapu, K.; Bist, N.; Yadav, K.; Singh, S. Applications of Nanoparticles in Enhanced Oil Recovery. Pet. res. 2022, 7, 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Cheraghian, G.; Hendraningrat, L. A Review on Applications of Nanotechnology in the Enhanced Oil Recovery Part A: Effects of Nanoparticles on Interfacial Tension. Int Nano Lett 2016, 6, 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Tavakkoli, O.; Kamyab, H.; Shariati, M.; Mustafa Mohamed, A.; Junin, R. Effect of Nanoparticles on the Performance of Polymer/Surfactant Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review. Fuel 2022, 312, 122867. [CrossRef]

- Le, N.Y.T.; Pham, D.K.; Le, K.H.; Nguyen, P.T. Design and Screening of Synergistic Blends of SiO2 Nanoparticles and Surfactants for Enhanced Oil Recovery in High-Temperature Reservoirs. Adv. Nat. Sci: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 2, 035013. [CrossRef]

- Gowtham V, M.; Deodhar, S.; Thampi, S.P.; Basavaraj, M.G. Association in Like-Charged Surfactant–Nanoparticle Systems: Interfacial and Bulk Effects. Langmuir 2024, 40, 17410–17422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, E.L.; Thakur, S.; Ervin, A.; Shields, E.; Razavi, S. Adsorption of Surfactant Molecules onto the Surface of Colloidal Particles: Case of like-Charged Species. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 676, 132142. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhong, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M. Synergistic Mechanisms Between Nanoparticles and Surfactants: Insight Into NP–Surfactant Interactions. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 913360. [CrossRef]

- Betancur, S.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Franco, C.A.; Cortés, F.B. Development of Composite Materials Based on the Interaction between Nanoparticles and Surfactants for Application in Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 12367–12377. [CrossRef]

- Agi, A.; Junin, R.; Gbadamosi, A. Mechanism Governing Nanoparticle Flow Behaviour in Porous Media: Insight for Enhanced Oil Recovery Applications. Int Nano Lett 2018, 8, 49–77. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Schechter, D.S. Surfactant Selection for Enhanced Oil Recovery Based on Surfactant Molecular Structure in Unconventional Liquid Reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107702. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Kadhum, M.J.; Harwell, J.H.; Shiau, B.-J. Using Carbonaceous Nanoparticles as Surfactant Carrier in Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Laboratory Study. Fuel 2018, 222, 561–568. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, F.; Wang, Q.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z. Flexible Responsive Janus Nanosheets. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3562–3565. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radnia, H.; Rashidi, A.; Solaimany Nazar, A.R.; Eskandari, M.M.; Jalilian, M. A Novel Nanofluid Based on Sulfonated Graphene for Enhanced Oil Recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 795–806. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Janus Sulfonated Graphene Oxide Nanosheets with Excellent Interfacial Properties for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136391. [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, H.; Binks, B.P.; Nguyen, D. Surfactant-Nanoparticle Formulations for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Calcite-Rich Rocks. Langmuir 2024, 40, 24989–25002. [CrossRef]

- Alhuraishawy, A.K.; Hamied, R.S.; Hammood, H.A.; AL-Bazzaz, W.H. Enhanced Oil Recovery for Carbonate Oil Reservoir by Using Nano-Surfactant:Part II. In Proceedings of the SPE Gas & Oil Technology Showcase and Conference, Dubai, UAE, 21-23 October 2019. [CrossRef]

- Al-Asadi, A.; Rodil, E.; Soto, A. Nanoparticles in Chemical EOR: A Review on Flooding Tests. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4142. [CrossRef]

- El-Masry, J.F.; Bou-Hamdan, K.F.; Abbas, A.H.; Martyushev, D.A. A Comprehensive Review on Utilizing Nanomaterials in Enhanced Oil Recovery Applications. Energies 2023, 16, 691. [CrossRef]

- Kandiel, Y.E.; Attia, G.M.; Metwalli, F.I.; Khalaf, R.E.; Mahmoud, O. Nanoparticles in Enhanced Oil Recovery: State-of-the-Art Review. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 2025, 15, 66. [CrossRef]

- Hosny, R.; Zahran, A.; Abotaleb, A.; Ramzi, M.; Mubarak, M.F.; Zayed, M.A.; Shahawy, A.E.; Hussein, M.F. Nanotechnology Impact on Chemical-Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Recent Developments. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 46325–46345. [CrossRef]

- Behera, U.S.; Poddar, S.; Deshmukh, M.P.; Sangwai, J.S.; Byun, H.-S. Comprehensive Review on the Role of Nanoparticles and Nanofluids in Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery: Interfacial Phenomenon, Compatibility, Scalability, and Economic Viability. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 13760–13795. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Kang, Y. A Comprehensive Review on Application and Perspectives of Nanomaterials in Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 2916–2942. [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.A.; Franco, C.A.; Zabala, R.D.; Bahamón, Í.; Forero, Á.; Cortés, F.B. Field Applications of Nanotechnology in the Oil and Gas Industry: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 19266–19287. [CrossRef]

- Kaito, Y.; Goto, A.; Ito, D.; Murakami, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Ohori, T. First Nanoparticle-Based EOR Nano-EOR Project in Japan: Laboratory Experiments for a Field Pilot Test. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Virtual, 25-29 April 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kanj, M.Y.; Rashid, Md.H.; Giannelis, E.P. Industry First Field Trial of Reservoir Nanoagents. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference, Manama, Bahrain, 25-28 September 2011. [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, S.O.; Dejam, M. A Comprehensive Review on Interaction of Nanoparticles with Low Salinity Water and Surfactant for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Sandstone and Carbonate Reservoirs. Fuel 2019, 241, 1045–1057. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.J. Status of Surfactant EOR Technology. Petroleum 2015, 1, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Volokitin, Y.; Shuster, M.; Karpan, V.; Koltsov, I.; Mikhaylenko, E.; Bondar, M.; Podberezhny, M.; Rakitin, A.; Batenburg, D.W.; Parker, A.R.; et al. Results of Alkaline-Surfactant-Polymer Flooding Pilot at West Salym Field. In Proceedings of the SPE EOR Conference at Oil and Gas West Asia, Muscat, Oman, 26-28 March 2018. [CrossRef]

- Altunina, L.K.; Kuvshinov, V.A. Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Physical and Chemical Methods for Enhanced Oil Recovery, Created at the Institute of Petroleum Chemistry SB RAS. Surfactant-Based Compositions for Enhancing Oil Recovery. Chemistry for Sustainable Development 2025, 33, 89–116. [CrossRef]

- Safarov, F.; Telin, A.; Vezhnin, S.; Fakhreeva, A.; Akhmetov, A.; Lenchenkova, L.; Yakubov, R.; Ovchinnikov, K.; Podlesnova, E.; Latypova, L. Integrated Reservoir Stimulation with Polyacrylamide Hydrogels and Surfactant Solutions for Oil Recovery Enhancement. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 1593–1608. [CrossRef]

- Esfandyari, H.; Shadizadeh, S.R.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Davarpanah, A. Implications of Anionic and Natural Surfactants to Measure Wettability Alteration in EOR Processes. Fuel 2020, 278, 118392. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, K.A.; Podlesnova, E.V.; Telin, A.G.; Safarov, F.E.; Sergeeva, N.A.; Ratner, A.A. Composition for Enhanced Oil Recovery and Method of Its Application. Russian Patent RU2800175, 1 July 1989.

- Wang, Z.; Dai, C.; Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, N.; Li, L. Anionic-Nonionic and Nonionic Mixed Surfactant Systems for Oil Displacement: Impact of Ethoxylate Chain Lengths on the Synergistic Effect. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 678, 132436. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, K.A.; Podlesnova, E.V.; Safarov, F.E.; Sergeeva, N.A.; Telin, A.G.; Kleimenov, A.V. Selection of Surfactant Compositions for Extraction Residual Oil Reserves in the Conditions of High-Temperature Reservoirs of The Neocomian Deposits of the BS Group Formations of Western Siberia. Pet. Eng. 2023, 21, 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, D.; Jiang, S. Review on Enhanced Oil Recovery by Nanofluids. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. – Rev. IFP Energies nouvelles 2018, 73, 37. [CrossRef]

- Silantiev, V.V.; Validov, M.F.; Miftakhutdinova, D.N.; Morozov, V.P.; Ganiev, B.G.; Lutfullin, A.A.; Shumatbaev, K.D.; Khabipov, R.M.; Nurgalieva, N.G.; Tolokonnikova, Z.A.; et al. Sedimentation Model of the Middle Devonian Clastic Succession of the South Tatar Arch, Pashyian Regional Stage, Volga-Ural Oil and Gas Province, Russia. Georesursy 2022, 24, 12–39. [CrossRef]

- Burkhanov, R.N.; Lutfullin, A.A.; Ibragimov, I.I.; Maksyutin, A.V. Core Column Filtration Testing Supplemented by Measurements of Oil Optical Properties. In Proceedings of the SPE Russian Petroleum Technology Conference, Virtual, 26-29 October 2020. [CrossRef]

- Meshalkin, V.; Asadullin, R.; Vezhnin, S.; Voloshin, A.; Gallyamova, R.; Deryaev, A.; Dokichev, V.; Eshmuratov, A.; Lenchenkova, L.; Pavlik, A.; et al. Engineering and Technological Approaches to Well Killing in Hydrophilic Formations with Simultaneous Oil Production Enhancement and Water Shutoff Using Selective Polymer-Inorganic Composites. Energies 2025, 18, 4721. [CrossRef]

- Levashenko, G.I.; Simonkov, V.V. Determination of the Optical Constants of Soot in Hydrocarbon Fuel Combustion Products at λ = 10.6 Μm. Physics of Combustion and Explosion 1995, 31, 70–73.

- Khlebtsov, B.N.; Khanadeev, V.A.; Khlebtsov, N.G. Determination of the Size, Concentration, and Refractive Index of Silica Nanoparticles from Turbidity Spectra. Langmuir 2008, 24, 8964–8970. [CrossRef]

- OST 39-204-86. Oil. Laboratory Method for Determining the Residual Water Saturation of Oil and Gas Reservoirs Based on the Dependence of Saturation on Capillary Pressure. Moscow, Minnefteprom, 1986.

- GOST 26450.0-85. Mineral Rocks. General Requirements for Sampling and Sample Preparation for the Determination of Reservoir Properties. Moscow, USSR State Committee for Standards (GOST), 1985.

- OST 39-195-86 Oil. Method of Determining the Coefficient of Displacement of Oil by Water in the Laboratory. Moscow, Minnefteprom, 1986.

- Mansurov, R.R.; Safronov, A.P.; Lakiza, N.V.; Leiman, D.V. Adsorption of TX-100 and SDBS on the Surface of Alumina and Maghemite Nanoparticles from Aqueous Solutions. Chim.Tech.Acta 2014, 1, 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Scale Software. Available Online: https://Antropol.Narod.Ru/Scale.Zip (Accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Startseva, R.Kh.; Parfenova, M.A.; Zaripov, R.N.; Blinov, S.A.; Fakhretdinov, R.N.; Lyapina, N.K. Modeling the Composition and Properties of Residual Oil. Pet. Chem. 1998, 38, 96–101.

- Razavifar, M.; Abdi, A.; Nikooee, E.; Aghili, O.; Riazi, M. Quantifying the Impact of Surface Roughness on Contact Angle Dynamics under Varying Conditions. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 16611. [CrossRef]

- Minakov, A.V.; Pryazhnikov, M.I.; Pryazhnikov, A.I.; Yakimov, A.S.; Denisov, I.A.; Lobasov, A.S.; Nemtsev, I.V.; Rudyak, V.Y. Application of Micro- and Nanofluidic Technologies in Enhanced Oil Recovery Tasks. Oil. Gas. Innovations 2022, 68–73.

- Kanj, M.Y.; Funk, J.J.; Al-Yousif, Z. Nanofluid Coreflood Experiments in the ARAB-D. In Proceedings of the SPE Saudi Arabia Section Technical Symposium, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 9-11 May 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ruchomski, L.; Mączka, E.; Kosmulski, M. Dispersions of Metal Oxides in the Presence of Anionic Surfactants. Colloids Interfaces 2018, 3, 3. [CrossRef]

- Safarov, F.E.; Telin, A.G.; Fakhreeva, A.V.; Bayanov, R.R.; Sergeeva, N.A.; Ovchinnikov, K.A.; Podlesnova, E.V.; Kleimenov, A.V. The Use of Sacrificial Reagents to Increase the Efficiency of Surfactant Compositions in Oil Recovery Enhancement Technologies in Conditions of High-Temperature Reservoirs of the Neocomian Deposits of the Bs Group of Western Siberia. Oil. Gas. Innov. 2024, 37–45.

- Rahman, A.F.A.; Arsad, A.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Bahari, M.B. Nano-Silica to Reduce of Surfactant Adsorption in Oil Recovery: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bondor, P.L. Applications of Carbon Dioxide in Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy Convers. Manag. 1992, 33, 579–586. [CrossRef]

| Nanoadditive | Specific surface, m2/g | Calculated mean diameter, nm |

| White carbon black BS-120 NU |

132 | 20.7 |

| Hydrophilic nanosilica HCSIL200 | 202 | 13.5 |

| Hydrophobic nanosilica RX380 | 380 | 7.2 |

| No | Parameter | Value |

| 1 | Core model length | 100–300 mm |

| 2 | Core temperature regulation range | (+25)–(+150) °C |

| 3 | Maximum overburden pressure | 70 MPa |

| 4 | Maximum reservoir pressure | 55 MPa |

| Exp. No. | Displacing agent (Post-waterflood) | Permeability, 10⁻³ μm² |

Displacement coefficient |

Increase in displacement coefficient, % | ||

| Absolute gas permeability | Oil phase permeability | Base | Post-composition injection | |||

| 1 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition, 1% in fresh water (Baseline experiment) | 258.9 | 105.9 | 0.763 | 0.882 | 11.9 |

| 2 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Hydrophilic nanosilica HSIL-200 | 201.9 | 70.2 | 0.607 | 0.750 | 14.3 |

| 3 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Hydrophobic nanosilica RX-380 | 262.3 | 117.6 | 0.633 | 0.864 | 23.1 |

| 4 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Uncompacted white carbon black | 199.5 | 62.1 | 0.647 | 0.837 | 19.0 |

| 5 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Graphene | 249.8 | 92.3 | 0.612 | 0.819 | 20.7 |

| 6 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Shungite (elutriated) | 200.3 | 67.3 | 0.626 | 0.858 | 23.2 |

| 7 | Anionic + Nonionic surfactant composition + 1% Gas black | 253.4 | 96.2 | 0.613 | 0.824 | 21.1 |

| 8 | 1% Anionic surfactant + 1% Graphene | 251.9 | 94.2 | 0.730 | 0.901 | 17.1 |

| 9 | 1% Anionic surfactant + 1% Uncompacted white carbon black | 250.8 | 93.1 | 0.622 | 0.741 | 11.9 |

| 10 | 1% Nonionic Surfactant + 1% Graphene | 252.2 | 95.6 | 0.651 | 0.745 | 9.4 |

| 11 | 1% Uncompacted white carbon black in fresh water | 239.1 | 82.7 | 0.599 | 0.599 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).