1. Introduction

The eukaryotic nucleus functions as more than a mere repository for genetic material. It is highly organized, self-organizing cellular control center and a concentrated hub of essential molecular machinery including the ribosome biogenesis and diverse transcriptional tools sequestered within the protective barrier of the nuclear envelope [

1]. The nucleus is divided into various sub-nuclear structure with most prominent being nucleolus which serves as a primary site for ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcription, processing and ribosome subunits assembly [

2]. Since nucleoli are involved in so many cellular functions, as a result, they are likely to become the primary target for virus to manipulate following infection. With restricted RNA genome, positive-sense RNA viruses must rely on host to complete their life cycles including replication, transcription, translation and assembly within cytoplasm. By utilizing virally-encoded polymerase and subverting host translation factors, these pathogens achieve rapid propagation without the need to breach hosts’ intracellular compartments. However, various studies (see below) have highlighted the traffic of positive-sense RNA virus proteins into nucleus and nucleolus.

There are two possible consequences after RNA virus proteins traffic to the nucleolus/nucleus in infected cells. First, the viral proteins localization in nucleolus result in nucleolar disruption thereby supressing cellular functions for resource competition. For example, the 3CD’ and 3CD, protease precursors of human rhinovirus (HRV) translocate into the nucleolus of infected cells to inhibit cellular RNA transcription via proteolytic mechanisms during early infection stage [

3]. In the early infection stage, coat protein of nervous necrosis virus (NNV) translocates into nucleus to sequester host polyadenylate binding protein (PABP) into nucleus to shut off cellular translation and degradate PABP via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway during later infection stage [

4]. Second, the nucleolus localizing viral proteins act as a co-ordinator to recruit and modify nucleolar proteins for viral propagation. For instance, the nsP2A of encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) binds to nucleolar chaperone B23 and translocates into the nucleolus to inhibit cellular cap-dependent mRNA translation and upregulates the viral internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-dependent translation by newly synthesized and modified ribosomes at early infection stage [

5]. In addition, viral targeting of the nucleolus interferes with ribosomal proteins, leading to nucleolar dysfunction, suppression of host mRNA translation, and the generation of heterogeneous ribosomes that preferentially support viral protein synthesis [

6].

For eukaryotic cells to function normally, the organelle proteins synthesized in cytoplasm must be transported into their destination compartments precisely and efficiently. Unlike one-way translocation of proteins to mitochondria, which localize via cleavable presequences or membrane insertions, the transport of cargo proteins between cytoplasm and nucleoplasm through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) is dependent on the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and nuclear export signal (NES) present on these cargo proteins. The NLS recognized by the corresponding nuclear transporters help NLS-containing proteins to enter the nucleus [

7]. Because many proteins also localize to the nucleus, they often possess both an NLS and nucleolar localization signal (NoLS) on their proteins. Within these proteins, these two signal sequences may even overlap but the nucleolus-retention may be governed by the association with another nucleolus bound protein or nucleolus transcribed rRNA [

8]. The NLS/NoLS sequences had been identified and studied on the viral proteins such as nucleocapsid protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRSSV) [

9], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [

10], non-structural protein nsP2 of Semliki Forest virus (SFV) [

11] and core protein of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) [

12]. Although the detailed mechanisms of viral proteins interacting with the nucleus and/or the nucleolus have not been comprehensively investigated, the mutations on NLS or NoLS motif sequences lead to impaired viral pathogenesis and replication [

11,

12].

Nodaviridae is a family of non-enveloped positive-sense single stranded RNA viruses that contain bipartite genome. This family comprises of three genus, including

Alphanodavirus which infect insects [

13],

Betanodavirus which cause disease outbreaks in marine fishes [

14] and

Gammanodavirus which infect prawns [

15]. NNV, a betanodavirus, is the etiologic agent of neurological disorders such as retinopathy and encephalopathy in wild and cultured marine fishes [

16]. NNV genome is composed of RNA1 and RNA2. RNA1 (3.1 kb) encodes RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) for viral RNAs replication and transcription. In addition, 3′-end of RNA1 transcribes a subgenome RNA3 (0.4 kb) encoding a non-structural protein B2 which suppresses host RNA interference (RNAi) function. RNA2 (1.4 kb) encodes the structural coat protein for viral particle packaging [

17]. The viral RNA replication compartment of nodavirus has been well studied in alphanodavirus flock house virus (FHV). Cryo-electron tomography revealed that replication compartments were observed as spherular invaginations of outer mitochondrial membranes, with neck of each spherule crowned by twelve-fold symmetric RdRps. Moreover, the crowns were also observed to associate with long cytoplasmic exported RNA fibrils [

18]. In betanodavirus, the viral particle assembly compartment of NNV was observed at the remodeled microtubule organizing center (MTOC) with crystalline array of virions inside protruding vesicles by transmission electron microcopy (TEM) [

19], however the information about propagation journey of nodavirus is still limited.

In this study, we trace viral proteins and viral particles subcellular localizations after NNV infection by immunocytochemistry and TEM. Our data showed translocation of B2 and coat protein into different nucleolus during early infection stage. Moreover, viral particles arranged in crytalline array surrounding the perinuclear area/remodeled MTOC and NNV particles containing vesicles fusing into inner nuclear membrane and nucleus filled with NNV virions were also observed. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an RNA virus utilizing nucleus as storehouse for NNV virions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell and Viruses

The grouper brain (GB) cells were established from orange-spotted grouper (

Epinephelus coioides) brain tissue[

20]. GB cells were cultured in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), L-glutamine (Gibco), and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) at 28℃.

The giant grouper (GG) (

Epinephelus lanceolatus) nervous necrosis virus (NNV)[

21] and yellow grouper (YG) (

Epinephelus awoara) NNV[

22] of red-spotted grouper (RG) NNV genotype were isolated from south Taiwan hatcheries. The recombinant (r) GGNNV (RdRp-Myc) and rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) were generated in our laboratory by reverse genetic approach as described previously [

23].

2.2. Immunocytochemistry

GB cells were seeded onto Deckglaser cover glass (Carolina) in 3-cm dish and mock-infected or infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) or rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc) at a MOI of 100. At indicated hpi, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4 °C. Afterwards, the cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, rinsed again with PBS and blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 2 h at room temperature (RT). After blocking, cells were incubated in primary antibodies prepared in 3% BSA in PBS using a 1:1,000 dilution for rabbit anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), a 1:1,000 dilution for anti-HA-488 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) and a 1:10 dilution for mouse anti- NNV coat protein monoclonal antibody (RG-M18) (homemade) [

24], overnight at 4 °C. The cells were washed with PBS four times and then hybridized with secondary antibody for 1 h at RT in dark. The secondary antibodies used were as follows: goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 488 polyclonal antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 647 polyclonal antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and goat anti-mouse Rhodamine Red X-conjugated AffiniPure IgG + IgM (H+L) antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), all the secondary antibodies were used at dilution of 1:1,000. After five PBS washes, the cover glass was mounted on glass slides with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) Fluormount-G (Southern Biotech) and sealed with CoverGrip coverslip sealant (Biotium). The slides were observed and images were collected with a Zeiss Observer Z1 (63× objective) inverted fluorescence microscope.

2.3. RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

GB cells were seeded onto Deckglaser cover slips (Carolina) in a 3-cm dish and next day infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at MOI of 100. At indicated time points, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Fixed cells were permeabilized using 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min and washed twice with PBS. Antisense RNA probes (100 ng each; RNA1-fluorescein and RNA2-DIG) were heat-denatured at 100 °C for 10 min and diluted in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 25% 20× SSC, and 0.002% salmon sperm DNA. Cells were first pre-hybridized with hybridization buffer at 65 °C for 2 h and then hybridized with the denatured probes at 65 °C overnight. Following hybridization, cells were washed sequentially with formamide- and SSC-based buffers at 65 °C. The cells were washed twice with 50% formamide (in 2× SSC) at 65 °C for 10 min each followed by twice 2× SSC and 0.2× SSC washes 65 °C for 5 min each. The cells were sequentially washed with 75% 0.2× SSC (in PBS), 50% 0.2× SSC (in PBS), 25% 0.2× SSC (in PBS) and 1× PBS at RT for 5 min each. The cells were then blocked with 1× Blocking solution (Roche) for 2 h at RT, stained with mouse anti-Fluorescein (FITC) IgG CF488A (for detecting rGGNNV RNA1-fluorescein) (Sigma) and sheep anti-Dioxigenin-Rhodamine, Fab fragments (Roche) (for detecting rGGNNV RNA2-DIG) prepared in 3% BSA (in Maleic acid buffer) diluted at 1:200 for 2 h at RT. Post-staining, the cells were washed three times with maleic acid buffer, twice with PBS and mounted with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) Fluormount-G (Southern Biotech) and sealed with CoverGrip coverslip sealant (Biotium). The slides were observed and images were collected with a Zeiss Observer Z1 (63× objective) inverted fluorescence microscope. RNA1 and RNA2 probes were prepared using RNA labeling kit (Roche) as described previously [

19].

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy

GB cells were cultured in the sapphire discs (Leica) inside a 3-cm glass bottom dish (Ibidi) overnight. After PBS wash, the GB cells were infected with GGNNV at a MOI of 0.01 and the cells were collected at 72 hpi. The specimens were subjected to high pressure freezing (Leica EM HPM100) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were subsequently freeze-substituted (using the Leica EM AFS2) with a fixative solution of 2% osmium tetroxide dissolved in acetone, maintained at −90 °C for 72 h, followed by a gradual increase in temperature to −20 °C over 16 h while still in the fixative. For detection of viral particles in the nucleus, GB cells were inoculated with YGNNV at MOI of 0.01 for 72 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 200 ×g for 5 min, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and post fixed in 1% tetroxide. The samples were then processed using a standard embedding protocol with Spurr’s medium for ultra-thin sectioning. Ultra-thin sections, approximately 90 nm thick, were cut using an ultramicrotome (Leica, Inc.) and subsequently stained with 4% uranyl acetate and 0.5% lead citrate. Electron micrographs were acquired with a Tecnai G2 TF20 Super TWIN TEM (Thermo Fisher, Inc.) operated at 120 kV.

3. Results

3.1. Translocation of RdRp into Mitochondria for NNV RNAs Synthesis

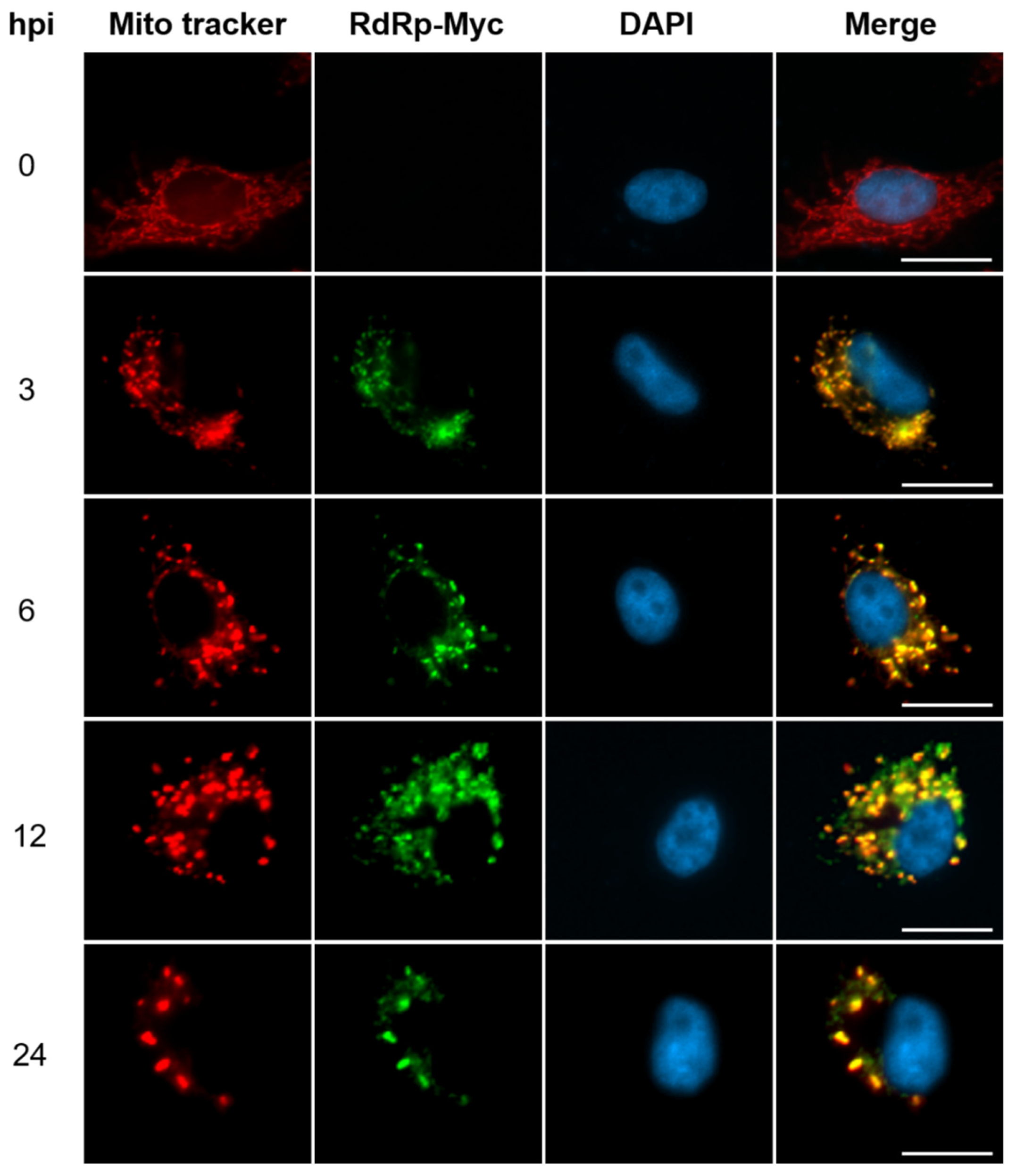

To explore the subcellular distribution of newly synthesized RdRp in GGNNV-infected GB cells, the immunocytochemistry experiment was performed. The recombinant (r) GGNNV with Myc-tag fusion to the C-terminus of RdRp was used to trace the RdRp signal using anti-Myc antibody. The mitochondria were stained with Mito tracker befor infection for comparison. During infection (3-24 hpi), the RdRp signals (green) co-localize with mitochondria signals (red) clearly suggesting that neosynthesized RdRp translocated into mitochondria in cytoplasm of infected cells. The scattered mitochondria form a crescent-shaped pattern on one side of cytoplasm. This result was supported by the previous studies[

19,

25]. At 0 h, the cells showed normal mitochondrial distribution. The RdRp-Myc signals gradually increased from 3 to 12 hpi. However, at 24 hpi, the RdRp signals declined indicating that active replication reduces at the later infection stage (

Figure 1). This result suggests that mitochondria is the compartment for NNV RdRp translocation and viral RNAs replication and transcription.

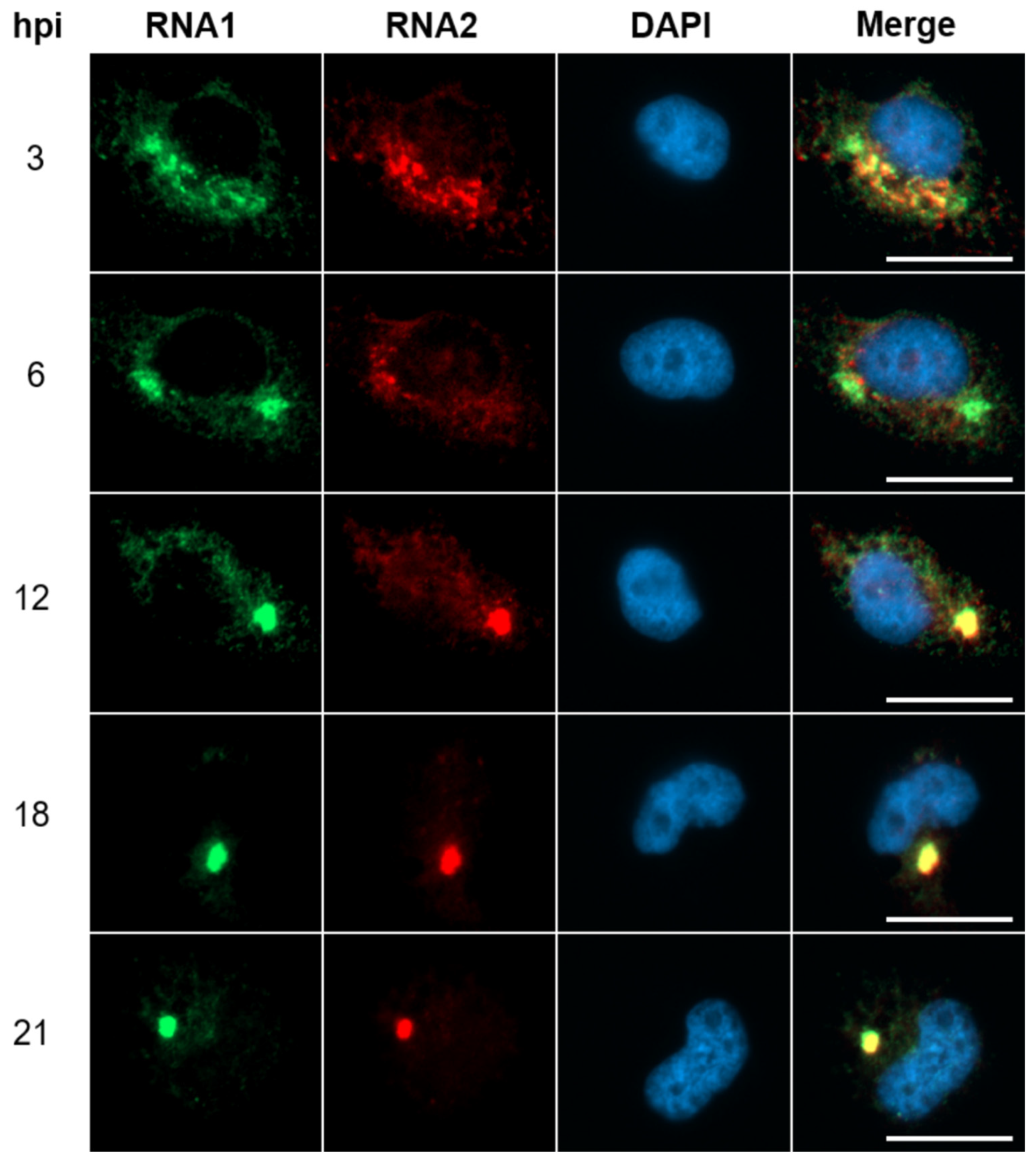

3.2. Neosynthesized NNV RNAs Move Toward Perinuclear Compartment

To explore viral replication and transcription, the neosynthesized NNV RNAs were traced with anti-RNA1 and anti-RNA2 probes by using RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in GGNNV-infected GB cells. We observed that RNA1 (green) and RNA2 (red) were colocalized in several spots in cytoplasm of infected cells at the early infection stage (3 hpi). The NNV RNAs spots were gradually merging to two different areas beside the nucleus (6 hpi), and eventually converged to one specific perinuclear compartment at later infection stage (12-21 hpi). Interestingly, NNV infection also induces nuclear reshaping to form a kidney-shaped nucleus with its inlet facing viral RNAs converging region at late infection stage (18-21 hpi) (

Figure 2). This result agrees with our previous study that NNV utilizes RNA2 as template to synthesize its coat protein in the translational factory vesicle moving toward perinuclear compartment using puromycin labelling [

19]. This result suggests that NNV RNAs are transported from sites (mitochondria) of replication/transcription moving toward perinuclear area.

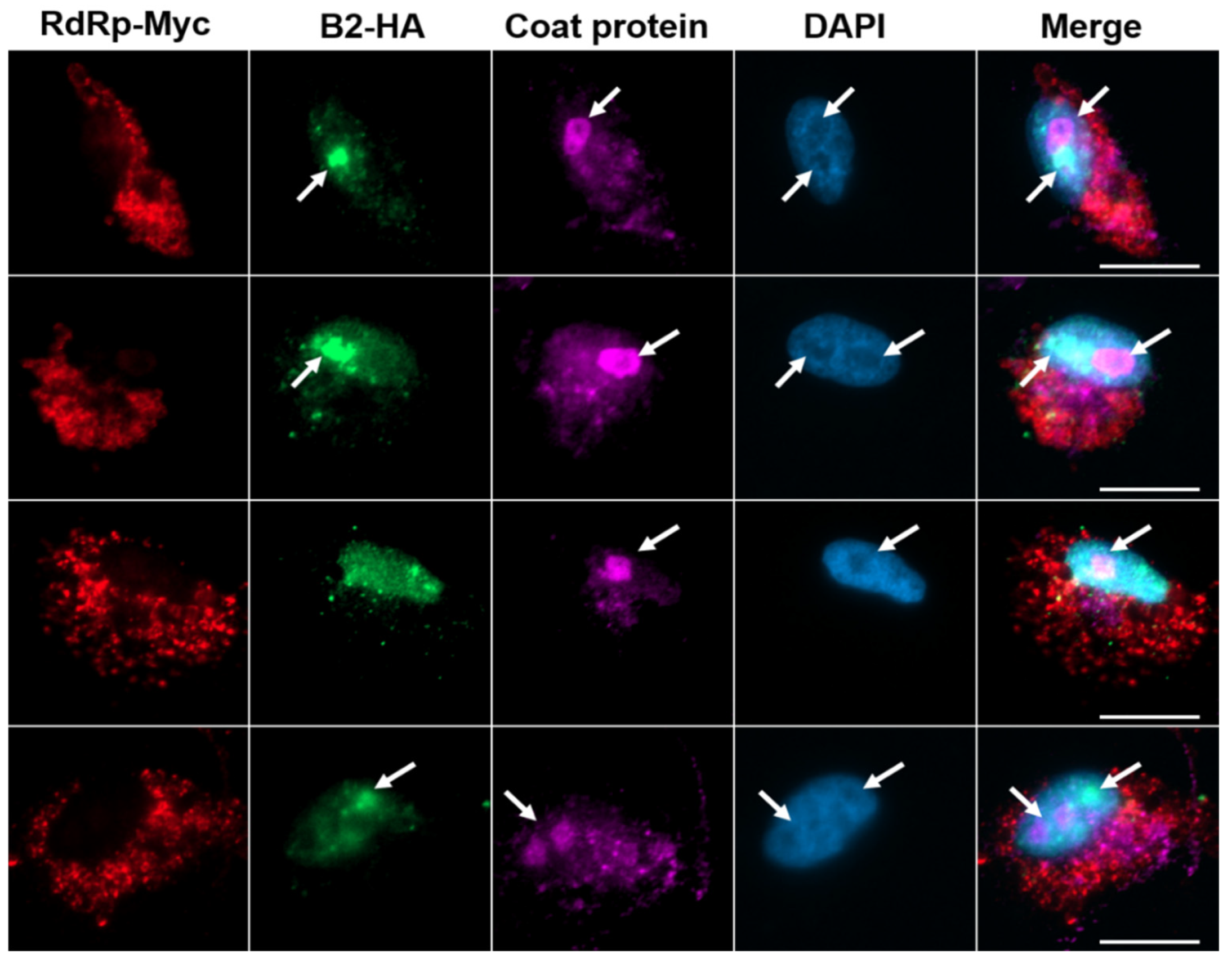

3.3. Transportation of NNV Viral Proteins into Nucleolus

We examined the subcellular distribution of NNV proteins during early stage of infection (2-8 hpi) using immunocytochemistry. For more accurate and easier detection of viral proteins, a rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) generated from reverse-genetic modification (25 Cheng et al., 2025) was utilized for infection. The rGGNNV contains a Myc-tag at the C-terminus of RdRp and a HA-tag at the C-terminus of B2 protein. The expression patterns of NNV RdRp-Myc and B2-HA fusion proteins were tracked with commercial anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. NNV coat protein was detected using anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) homemade monoclonal antibody. Our immunocytochemistry results showed that the RdRp-Myc signals (red) were localized in cytoplasm while the B2-HA signals (green) and coat protein (magenta) were observed at different areas of nucleoli (marked by white arrows) in the early infection stage (

Figure 3). It has been shown that the N-terminal amino acids from 14 to 33 of coat protein contribute to this nuceolus localization [

26]. This result suggests that the nucleolus-retention of both NNV B2 and coat protein in different areas may play critical roles to interfere cellular functions and/or help viral propagation in the early infection stage.

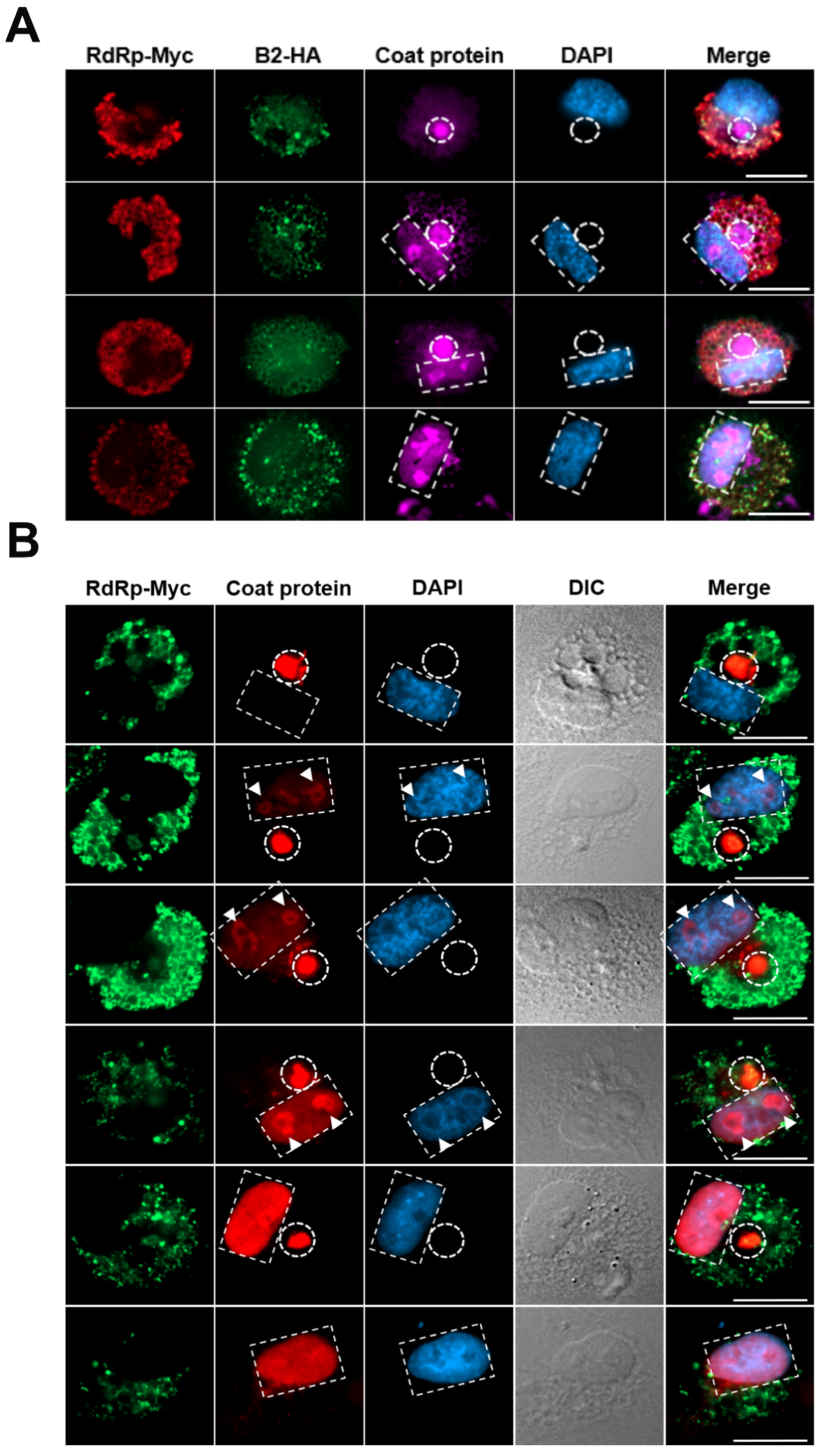

3.4. Convergence of NNV Coat Protein into Remodeled MTOC

We then examined the intracellular distribution of NNV proteins after infecting with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) on GB cells at late infection stage (18-24 hpi) by immunocytochemistry. We observed that both RdRp-Myc (red) and B2-HA (green) were distributed in the cytoplasm while coat protein (magenta) accumulated in specific perinuclear compartment and the nucleolus/nucleus. The perinuclear compartment showing the condensed coat protein signal (shown in white dotted circles) acts as translation factory and viral particle assembly center for NNV. This perinuclear compartment has been identified as remodeled Golgi-microtubule organizing center (MTOC) [

19]. In addition, the coat protein signals were observed again to fill the nucleolus and nucleus areas (shown in white-dotted rectangles) (

Figure 4A).

In another experiment, we used rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc) infected GB cells and observed its cellular localization using immunocytochemistry during late infection stage. In line with above results, we observed that RdRp-Myc (green) expression was cytoplasmic but gradually reduced afterwards. Coat protein signal (red) was concentrated at specific perinuclear remodeled MTOC (white dotted circles), gradually moved to nucleolus (white arrowheads) and eventually to nucleus (white dotted rectangles) with disappearing coat protein signal from remodeled MTOC (

Figure 4B). These results suggest that NNV coat proteins were translated and accumulated at the remodeled MTOC for viral particle assembly and then the packed viral particles were gradually transported into nucleolus and nucleus.

3.5. NNV Particles Assembly in Remodeled MTOC

To further confirm above immunocytochemistry observation, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with high pressure freezing fixation was performed. The 72 hpi, low MOI (0.01) GGNNV-infected GB cell thin section showed an infected cell with vesicles (V), swollen mitochondria (M), a nuclear envelope (NE) surrounding nucleus (N) and a perinuclear remodeled MTOC bounded by the plasma membrane (PM) The nucleus (N) displayed heterochromatin beneath the nuclear envelope (NE) (

Figure 5, upper panel). Enlarged view of white dashed box showed NNV viral particles arranged in crystalline array (whites asterisks) or circlular line (white arrowheads) enclosed within vesicles which fused together in remodeled MTOC (

Figure 5, lower panel).

3.6. NNV Particles Containing Vesicles Merging into Nucleus

The condensed coat protein signal appearing at the nucleolus and nucleus areas by immunochemistry detection was unexpected. To clarify this finding, we examined the infected cell thin sections through TEM. Considering that coat protein signal localized within nucleolus/nucleus area (

Figure 4A-B), we also examined the NNV induced nuclear changes. Interestingly, TEM analysis showcased a very unique phenomenon following GGNNV infection in GB cells, characterized by expansion of the perinuclear cisternal space (PCS) (

Figure 6A, upper left panel) and the fusion of vesicles containing NNV particles (white arrowheads) in the perinuclear white boxed region 1 (

Figure 6A, enlarged image in upper right panel), and one vesicle fusing with the inner nuclear membrane (INM) (white boxed region 2 in

Figure 6A, enlarged image in lower right panel).

We also observed enlarged perinuclear cisternal space filled with vesicles containing NNV virions (

Figure 6B, upper left panel). The zoomed-in images of white boxed region 1 and 2 showed a vesicle filled with NNV virions (white arrowhead) with multiple vesicles surrounding and NNV virions containing vesicle transiting across the outer and inner membranes of nucleus, respectively (

Figure 6B, upper right panel, lower left panel). Moreover, a high magnification view of white boxed region 3 showed a large vesicle undergoing membrane fusion with other vesicles and with inner nuclear membrane, transporting viral particles (white arrowheads) into nucleus (

Figure 6B, lower right panel). These results suggest that NNV particles exploit vesicular transport to nucleolus and nucleus for virions storage.

3.7. Storage of NNV Particles Inside Nucleus

At the late infection stage, the immunocytochemical analysis showed that RdRp localized in the cytoplasm, whereas the coat protein signal was initially concentrated at the remodeled MTOC, then progressively trafficked into nucleolus and eventually redistributed toward whole nucleus. To further substantiate these findings, TEM of YGNNV-infected GB cells was performed. In infected GB cells, we observed various vesciles surrounding the nucleus (

Figure 7, upper panel). An enlarged image of white boxed region revealed crystalline array of NNV particles completely filled inside the nucleus. The 31-34 nm NNV particles within the nucleus encapsulated by various membranes like Golgi apparatus (

Figure 7, lower panel). This result suggests that NNV utilizes privileged nucleus environment for long term storage of viral particles for successive rounds of infection in the future.

4. Discussion

Viruses are strictly intracellular parasitic organisms and rely on host resources to complete their propagation and transmission. Viruses hijack various cellular machineries at every stage of their life cycle, and change the canonical functions of a cell to support their production. Viruses also frequently exploit existing subcellular organelles or de novo compartments for their viral production and evade antiviral defenses. After GGNNV infection in GB cells, the initially neo-synthesized RdRps were translocated into outer membrane of mitochondria to produce viral RNAs (

Figure 1). The transportation of NNV RdRp into mitochondria is controlled by the mitochondrial targeting signal on the N-terminal amino acids 215 to 255 of protein A (RdRp) [

25]. Mitochondria serve as a replication and transcription viral factories which was further confirmed by the BrU labeling experiment for neo-synthesized viral RNAs in infected GB cells[

19]. Within the de novo compartment, the neo-synthesized NNV RNA1 and RNA2 along with coat protein in multiple vesicles moved toward perinuclear area as demonstrated by immunocytochemistry and RNA-FISH experiments (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4) in previous study [

19]. At later stage, RdRp signals decreased due to its degradation by host cellular defense by Mx protein through autophagolysosome in an attempt to inhibit replication [

27]. Interestingly, the initially neo-synthesized NNV B2 and coat proteins were observed to translocate into host nucleolus and nucleus in the early infection stage (

Figure 3). As the infection progresses, coat proteins are transiently retained in the nucleolus during the early infection stage, but localize to the perinuclear compartment at later infection stage (

Figure 4). These compartments were architecturally supported by the intermediate filaments of vimentin, plectin and desmin[

19]. By manipulating host intracellular trafficking pathway, the translational factory (for coat protein) vesicles eventually move to perinuclear area and associate with gamma-tubulin and trans-Golgi to form remodeled MTOC which functions as a centralized viral factory for translation and viral particles assembly (

Figure 4). These immunostaining signals were further supported by our TEM observations of the perinuclear area where virion-containing vesicles fuse together to form a reorganized multivesicular complex containing the MTOC (

Figure 5). This result was also supported by the previous study [

19]. This spatial reorganization closely resembles the viral factories observed in other RNA viruses, such as rotaviruses, which hijack the host’s microtubule network to sequester viral components away from cytoplasmic defenses [

28].

Viruses are dependent on host translation machinery and has evolved several ways to inhibit host translation and divert the translation factors along with ribosomes for their propagation. Poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) plays an important role in stimulating cap-dependent translation and ribosome recycling for subsequent rounds of translation [

29] and is commonly targeted by viruses without poly(A)-tail genome. For instance, rotavirus NS3 protein relocalizes PABP to the nucleus and induces host translation shut off by fully dissociating PABP from translation complex [

30] and bunyamwera virus (BUNV) N protein also relocates PABP inducing host translation shut off but does not accumulate itself in the nucleus [

31]. We previously reported that NNV coat protein is involved in host translation shut off by sequestering PABP into the nucleus in the early infection stage and degradation of PABP via ubiquitin-26S proteasome in the late infection stage [

4]. This result helps explain part of the function of coat proteins trafficking to nucleolus/nucleus areas. Indeed, our preliminary data also show that nucleolar localization of the B2 protein leads to shutdown of host translation. Although the redistribution signals of ectopic expression of B2 were not strong as that of ectopic expression of coat protein, B2 protein still colocalize with PABP very well in nucleolus region (Supplementary

Figure 1A). The ectopic expression of nucleolus-retentive B2 protein show completely shut off host translation detected by puromycin-labeling (Supplementary

Figure 1B).

Beyond these findings, our results demonstrate that both B2 and coat protein translocate to distinct nucleolar sub-compartments during early stages of infection (

Figure 3). Sequence analysis confirms that this translocation is driven by specific NLS/ NoLS, highlighting a potential mechanism by which viral proteins access intracellular compartments. The nucleolar targeting of coat protein via its N-terminal NLS,

23RRRANNRRR

31 has been identified previously [

26] where it interacts with B23/nucleophosmin playing an important role in NNV replication [

32]. This interaction mirrors the behavior of PRSSV N protein and core protein of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), which has been shown to interact with host nucleolar proteins such as fibrillarin and B23, respectively [

33,

34]. In PRRSV, these interactions are thought to influence host cell processes and stress responses, while in JEV-infected cells, the interaction with B23 contributes to JEV replication. Since B23 plays important role in ribosome biogenesis, cell cycle regulation, and stress responses, and owing to its interaction with NNV, we propose that the accumulation of coat protein in the nucleolus may induce assembly of heterogeneous ribosomes. This would allow the virus to bypass the lack of an IRES by creating specialized ribosomal populations that preferentially translate capped NNV transcripts over host mRNAs. In the previous study, our evidence proves that the translation initiation of NNV coat protein require RPS6 but not phosphorylated RPS6 [

19]. In another experiment, we found that RPL7a were associated with coat protein tightly which colocalized in nucleus after ectopic expression (Supplementary

Figure 2). These results suggest that the nucleolus-retention of B2 and coat protein may play a role for heterogeneous ribosome subunits biogenesis and/or assembly for their own translation. This hypothesis needs further investigation.

Our TEM results also provide insights into the mechanisms by which NNV virions, enclosed in a vesicle, traverses across nuclear membrane. These vesicles appear to fuse with inner nuclear membrane to facilitate the sequestered storage of NNV virions within the organelle (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). This process resembles a standard egress pathway transporting vesicle from cytoplasm to plasma membrane, but instead functions as a strategic translocation of virions from the cytoplasm into nucleus for long-term storage. By hijacking host transport machinery, NNV transforms the nucleus from a highly protected system into a valuable resource, utilizing privileged environment to store virions for another round of infection. This behavior closely parallels the strategy of baculoviruses, which form a large occlusion bodies (OBs) within the nuclei of infected insect cells. These structures are comprised of the polyhedrin protein and encapsulate large numbers of virions, protecting them and enabling long-term environmental persistence [

35]. Ultimately, this storage strategy represents an evolutionary adaptation for an ancestral virus like NNV. By sequestering viral particles for long-term latency, the virus compensates for a lack of specialized mechanisms to bypass more advanced host innate defenses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B., C.L., C.C.; methodology, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., C.C., C.C., Y.W., S.C., C.C.; validation, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., S.C.; formal analysis, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., C.C., C.C., Y.W., S.C., C.C. ; investigation, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., C.C., S.C.; resources, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., C.C.; software V.B., C.L.; data curation, V.B., C.L., K.F., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, V.B., S.C., and C.C.; visualization, V.B., C.L., K.F., C.L., M.C., I.L., P.W., C.C., C.C., S.C.; supervision S.C., Y.W., C.C.; project administration, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Academia Sinica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank ICOB Imaging and electron microscopy Core Facilities, Academia Sinica for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hetzer, M.W. The nuclear envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010, 2, a000539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, M.-L.; Boisvert, F.-M. The Nucleolus: Structure and Function. In The Functional Nucleus; Bazett-Jones, D.P., Dellaire, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amineva, S.P.; Aminev, A.G.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Gern, J.E. Rhinovirus 3C protease precursors 3CD and 3CD’ localize to the nuclei of infected cells. J Gen Virol 2004, 85, 2969–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.A.; Luo, J.M.; Chiang, M.H.; Fang, K.Y.; Li, C.H.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, Y.S.; Chang, C.Y. Nervous Necrosis Virus Coat Protein Mediates Host Translation Shutoff through Nuclear Translocalization and Degradation of Polyadenylate Binding Protein. J Virol 2021, 95, e0236420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminev, A.G.; Amineva, S.P.; Palmenberg, A.C. Encephalomyocarditis viral protein 2A localizes to nucleoli and inhibits cap-dependent mRNA translation. Virus Res 2003, 95, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, G. Ribosomal control in RNA virus-infected cells. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1026887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Song, W.; Qiao, J.; Ruan, H. Types of nuclear localization signals and mechanisms of protein import into the nucleus. Cell Commun Signal 2021, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscox, J.A. RNA viruses: hijacking the dynamic nucleolus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, R.R.; Schneider, P.; Fang, Y.; Wootton, S.; Yoo, D.; Benfield, D.A. Peptide domains involved in the localization of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein to the nucleolus. Virology 2003, 316, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, R.R.; Chauhan, V.; Fang, Y.; Pekosz, A.; Kerrigan, M.; Burton, M.D. Intracellular localization of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein: absence of nucleolar accumulation during infection and after expression as a recombinant protein in vero cells. J Virol 2005, 79, 11507–11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peränen, J.; Rikkonen, M.; Liljeström, P.; Kääriäinen, L. Nuclear localization of Semliki Forest virus-specific nonstructural protein nsP2. J Virol 1990, 64, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Okabayashi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wakita, T.; Yasui, K.; Hasebe, F.; Tadano, M.; Konishi, E.; Moriishi, K.; et al. Nuclear localization of Japanese encephalitis virus core protein enhances viral replication. J Virol 2005, 79, 3448–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, S.C.; Scotti, P.D.; Wigley, P.J.; Dhana, S.D. A small RNA virus isolated from the grass grub, Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). New Zealand Journal of Zoology 1980, 7, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YOSHIKOSHI, K.; INOUE, K. Viral nervous necrosis in hatchery-reared larvae and juveniles of Japanese parrotfish, Oplegnathus fasciatus (Temminck & Schlegel). Journal of Fish Diseases 1990, 13, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcier, J.; Herman, F.; Lightner, D.V.; Redman, R.M.; Mari, J.; Bonami, J. A viral disease associated with mortalities in hatchery-reared postlarvae of the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 1999, 38, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, B.L.; Langdon, J.S.; Hyatt, A.; Humphrey, J.D. Mass mortality associated with a viral-induced vacuolating encephalopathy and retinopathy of larval and juvenile barramundi, Lates calcarifer Bloch. Aquaculture 1992, 103, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, T.; Mise, K.; Takeda, A.; Okinaka, Y.; Mori, K.I.; Arimoto, M.; Okuno, T.; Nakai, T. Characterization of Striped jack nervous necrosis virus subgenomic RNA3 and biological activities of its encoded protein B2. J Gen Virol 2005, 86, 2807–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertel, K.J.; Benefield, D.; Castaño-Diez, D.; Pennington, J.G.; Horswill, M.; den Boon, J.A.; Otegui, M.S.; Ahlquist, P. Cryo-electron tomography reveals novel features of a viral RNA replication compartment. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, V.; Li, C.H.; Lai, C.S.; Fang, K.Y.; Chiang, M.H.; Chen, W.D.; Chen, W.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, Y.S.; Chen, S.C.; et al. Translation of nervous necrosis virus involves eIF4E but not RPS6 phosphorylation and viral particle assembly in remodeled microtubule-organizing center. Virol J 2025, 22, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Christopher John, J.A.; Lin, C.H.; Chang, C.Y. Inhibition of nervous necrosis virus propagation by fish Mx proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 351, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Wu, M.S.; Huang, Y.J.; Cheng, C.A.; Chang, C.Y. Recognition of Linear B-Cell Epitope of Betanodavirus Coat Protein by RG-M18 Neutralizing mAB Inhibits Giant Grouper Nervous Necrosis Virus (GGNNV) Infection. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0126121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-S.; Murali, S.; Chiu, H.-C.; Ju, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chen, S.-C.; Guo, I.-C.; Fang, K.; Chang, C.-Y. Propagation of yellow grouper nervous necrosis virus (YGNNV) in a new nodavirus-susceptible cell line from yellow grouper, Epinephelus awoara (Temminck & Schlegel), brain tissue. Journal of Fish Diseases 2001, 24, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.A.; Lai, C.S.; Liao, F.E.; Yeh, S.L.; Chiang, M.H.; Li, C.H.; Fang, K.Y.; Liao, Y.C.; Hsu, H.C.; Bajpai, V.; et al. Giant grouper nervous necrosis virus subgenomic RNA3 is transcribed by a premature termination mechanism via intragenomic RNA-RNA pairing. Virol J 2025, 22, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-S.; Chiu, H.-C.; Murali, S.; Guo, I.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; Fang, K.; Chang, C.-Y. In vitro neutralization by monoclonal antibodies against yellow grouper nervous necrosis virus (YGNNV) and immunolocalization of virus infection in yellow grouper, Epinephelus awoara (Temminck & Schlegel). Journal of Fish Diseases 2001, 24, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Chan, S.W.; Kwang, J. Membrane association of greasy grouper nervous necrosis virus protein A and characterization of its mitochondrial localization targeting signal. J Virol 2004, 78, 6498–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Dallmann, K.; Kwang, J. Identification of nucleolus localization signal of betanodavirus GGNNV protein alpha. Virology 2003, 306, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Su, Y.L.; Shie, P.S.; Huang, S.L.; Yang, H.L.; Chen, T.Y. Grouper Mx confers resistance to nodavirus and interacts with coat protein. Dev Comp Immunol 2008, 32, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichwald, C.; Arnoldi, F.; Laimbacher, A.S.; Schraner, E.M.; Fraefel, C.; Wild, P.; Burrone, O.R.; Ackermann, M. Rotavirus viroplasm fusion and perinuclear localization are dynamic processes requiring stabilized microtubules. PLoS One 2012, 7, e47947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.W.; Gray, N.K. Poly(A)-binding protein (PABP): a common viral target. Biochem J 2010, 426, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, M.; Becker, M.M.; Vitour, D.; Baron, C.H.; Vende, P.; Brown, S.C.; Bolte, S.; Arold, S.T.; Poncet, D. Nuclear localization of cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein upon rotavirus infection involves the interaction of NSP3 with eIF4G and RoXaN. J Virol 2008, 82, 11283–11293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakqori, G.; van Knippenberg, I.; Elliott, R.M. Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus S-segment untranslated regions mediate poly(A) tail-independent translation. J Virol 2009, 83, 3637–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, W.; Huang, F.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. Nervous necrosis virus capsid protein exploits nucleolar phosphoprotein Nucleophosmin (B23) function for viral replication. Virus Res 2017, 230, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, Y.; Mori, Y.; Abe, T.; Yamashita, T.; Okamoto, T.; Ichimura, T.; Moriishi, K.; Matsuura, Y. Nucleolar protein B23 interacts with Japanese encephalitis virus core protein and participates in viral replication. Microbiol Immunol 2006, 50, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Wootton, S.K.; Li, G.; Song, C.; Rowland, R.R. Colocalization and interaction of the porcine arterivirus nucleocapsid protein with the small nucleolar RNA-associated protein fibrillarin. J Virol 2003, 77, 12173–12183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, J.; Arif, B.M. The baculoviruses occlusion-derived virus: virion structure and function. Adv Virus Res 2007, 69, 99–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Newly synthesized RdRp translocate into mitochondria outer membrane for NNV RNAs replication and transcription. GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were stained with 100 nM Mito tracker (red) for 30 min prior to infection and subsequently infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at MOI of 100. The cells were fixed at 0, 3, 6, 12 and 24 hpi and cellular localization of RdRP-Myc (green) was detected using immunocytochemistry with rabbit anti-Myc antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 1.

Newly synthesized RdRp translocate into mitochondria outer membrane for NNV RNAs replication and transcription. GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were stained with 100 nM Mito tracker (red) for 30 min prior to infection and subsequently infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at MOI of 100. The cells were fixed at 0, 3, 6, 12 and 24 hpi and cellular localization of RdRP-Myc (green) was detected using immunocytochemistry with rabbit anti-Myc antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 2.

NNV RNA1 and RNA2 in viral factory vesicles move out of mitochondria toward perinuclear compartments. GB cells grown on coverslips were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at different hpi (3-21 hpi). RNA1 (green) and RNA2 (red) were detected using RNA-FISH with RNA1 (-) and RNA2 (-) probes, respectively. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; RNA FISH, RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Figure 2.

NNV RNA1 and RNA2 in viral factory vesicles move out of mitochondria toward perinuclear compartments. GB cells grown on coverslips were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at different hpi (3-21 hpi). RNA1 (green) and RNA2 (red) were detected using RNA-FISH with RNA1 (-) and RNA2 (-) probes, respectively. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; RNA FISH, RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Figure 3.

Translocation of B2 and coat protein into nucleolus at the early infection stage of GGNNV in GB cells. GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at earlier infection time points (2-7 hpi). Localization of B2-HA (green) and coat protein (magenta) was detected using mouse anti-HA 488 and mouse anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibodies, respectively. RdRp-Myc (red) was detected using rabbit anti-Myc antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed B2 and coat protein in the nucleolus (marked by white arrows) during early infection stage. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 3.

Translocation of B2 and coat protein into nucleolus at the early infection stage of GGNNV in GB cells. GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at earlier infection time points (2-7 hpi). Localization of B2-HA (green) and coat protein (magenta) was detected using mouse anti-HA 488 and mouse anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibodies, respectively. RdRp-Myc (red) was detected using rabbit anti-Myc antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed B2 and coat protein in the nucleolus (marked by white arrows) during early infection stage. Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 4.

NNV coat protein translation factories move into remodeled MTOC and nucleus. (A) GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at late infection stage (18-24 hpi). Cells were stained with rabbit anti-Myc and mouse anti-HA 488 to detect RdRp (red) and B2 (green), respectively. Coat protein (magenta) was detected using mouse anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed coat protein in viral remodeled MTOC (white-dotted circles) and viral storehouse in nucleus (white-dotted rectangles). Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at late infection stage (18-24 hpi). Cellular localization of RdRP-Myc (green) and coat protein (red) was detected using immunocytochemical staining with anti-Myc and anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibodies, respectively. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed coat protein in remodeled MTOC (white-dotted circle), translocation of coat protein to nucleolus (white arrowheads) and nucleus (white-dotted rectangles). Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DIC, Differential Interference Contrast; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 4.

NNV coat protein translation factories move into remodeled MTOC and nucleus. (A) GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc, B2-HA) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at late infection stage (18-24 hpi). Cells were stained with rabbit anti-Myc and mouse anti-HA 488 to detect RdRp (red) and B2 (green), respectively. Coat protein (magenta) was detected using mouse anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibody. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed coat protein in viral remodeled MTOC (white-dotted circles) and viral storehouse in nucleus (white-dotted rectangles). Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) GB cells grown overnight on coverslips in 3-cm dish were infected with rGGNNV (RdRp-Myc) at a MOI of 100 and fixed at late infection stage (18-24 hpi). Cellular localization of RdRP-Myc (green) and coat protein (red) was detected using immunocytochemical staining with anti-Myc and anti-NNV coat protein (RG-M18) antibodies, respectively. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Images showed coat protein in remodeled MTOC (white-dotted circle), translocation of coat protein to nucleolus (white arrowheads) and nucleus (white-dotted rectangles). Scale bar = 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DIC, Differential Interference Contrast; GB, grouper brain; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; rGGNNV, recombinant giant grouper nervous necrosis virus.

Figure 5.

Remodeled MTOC associated with array and circular viral particles in vesicles of NNV-infected cell. GB cells were infected with low MOI of GGNNV (MOI = 0.01) and imaged by TEM at 72 hpi. Upper panel: Electron micrograph shows a low-magnification view of the entire cell, with the remodeled MTOC positioned near the nuclear membrane during the viral particle assembly stage. Cellular structures such as mitochondria (M), vesicle (V) and remodeled MTOC were present inside the cytoplasm bounded by the plasma membrane (PM). The cell nucleus (N) is bounded by the nuclear envelope composed of two nuclear membranes. The white dashed box marks the cell area selected for zoom in the lower panel. Scale bar = 1 μm. Lower panel: Electron micrograph shows various empty vesicles or multiple NNV virions enclosed within a vesicular structure, organized in a circular fashion (marked by white arrowheads) or crystalline array of NNV viral particles (marked by white asterisks) at MTOC. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. GB, grouper brain; GGNNV, giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 5.

Remodeled MTOC associated with array and circular viral particles in vesicles of NNV-infected cell. GB cells were infected with low MOI of GGNNV (MOI = 0.01) and imaged by TEM at 72 hpi. Upper panel: Electron micrograph shows a low-magnification view of the entire cell, with the remodeled MTOC positioned near the nuclear membrane during the viral particle assembly stage. Cellular structures such as mitochondria (M), vesicle (V) and remodeled MTOC were present inside the cytoplasm bounded by the plasma membrane (PM). The cell nucleus (N) is bounded by the nuclear envelope composed of two nuclear membranes. The white dashed box marks the cell area selected for zoom in the lower panel. Scale bar = 1 μm. Lower panel: Electron micrograph shows various empty vesicles or multiple NNV virions enclosed within a vesicular structure, organized in a circular fashion (marked by white arrowheads) or crystalline array of NNV viral particles (marked by white asterisks) at MTOC. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. GB, grouper brain; GGNNV, giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 6.

Fusion of NNV particles containing vesicles into nucleus of GGNNV infected GB cells. GB cells were infected with low MOI of GGNNV (MOI = 0.01) and imaged by TEM at 72 hpi. (A) Upper left panel: The nuclear membrane (NE) of the nucleus (N) displayed two (outer and inner) nuclear membranes with a perinuclear cisternal space (PCS) between them. The two membranes are fused to form nuclear pores along the NE. Ultrathin section also show vesicles containing NNV virions (white boxed region 1) and a small vesicle filled with NNV particles fusing with inner nuclear membrane (white boxed region 2). Scale bar = 0.6 μm. Upper right panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 1 from the cell. Empty vesicles or vesicles containing NNV particles (white arrowheads) were observed near nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower left panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 2 shows vesicle containing NNV virions (white arrowhead) fusing (white arrow) with inner nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. (B) Upper left panel: Ultrathin section shows enlarged perinuclear cisternal space with vesicles filled with NNV virions (white boxed region 1) and virions containing vesicles merging with inner nuclear membrane (white boxed region 2, 3). Scale bar = 1 μm. Upper right panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 1 shows vesicle containing NNV virion filled vesicle (white arrowhead). Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower left panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 2 shows NNV virion (white arrowhead) vesicle passing through the outer and inner nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower right panel: A high magnification view of white boxed region 3 shows a large perinuclear space with multiple NNV virions containing vesicles fusing each other and merging into inner nuclear membrane (white arrows). Scale bar = 0.2 μm. The nucleus (N), inner nuclear membrane (INM), nuclear pore (NP), perinuclear cisternal space (PCS), plasma membrane (PM) and vesicles (V) are indicated. GB, grouper brain; GGNNV, giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 6.

Fusion of NNV particles containing vesicles into nucleus of GGNNV infected GB cells. GB cells were infected with low MOI of GGNNV (MOI = 0.01) and imaged by TEM at 72 hpi. (A) Upper left panel: The nuclear membrane (NE) of the nucleus (N) displayed two (outer and inner) nuclear membranes with a perinuclear cisternal space (PCS) between them. The two membranes are fused to form nuclear pores along the NE. Ultrathin section also show vesicles containing NNV virions (white boxed region 1) and a small vesicle filled with NNV particles fusing with inner nuclear membrane (white boxed region 2). Scale bar = 0.6 μm. Upper right panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 1 from the cell. Empty vesicles or vesicles containing NNV particles (white arrowheads) were observed near nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower left panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 2 shows vesicle containing NNV virions (white arrowhead) fusing (white arrow) with inner nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. (B) Upper left panel: Ultrathin section shows enlarged perinuclear cisternal space with vesicles filled with NNV virions (white boxed region 1) and virions containing vesicles merging with inner nuclear membrane (white boxed region 2, 3). Scale bar = 1 μm. Upper right panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 1 shows vesicle containing NNV virion filled vesicle (white arrowhead). Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower left panel: Enlarged image of white boxed region 2 shows NNV virion (white arrowhead) vesicle passing through the outer and inner nuclear membrane. Scale bar = 0.2 μm. Lower right panel: A high magnification view of white boxed region 3 shows a large perinuclear space with multiple NNV virions containing vesicles fusing each other and merging into inner nuclear membrane (white arrows). Scale bar = 0.2 μm. The nucleus (N), inner nuclear membrane (INM), nuclear pore (NP), perinuclear cisternal space (PCS), plasma membrane (PM) and vesicles (V) are indicated. GB, grouper brain; GGNNV, giant grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 7.

Accumulation of NNV particles in nucleus at the late infection stage of YGNNV in GB cells. GB cells inoculated with YGNNV at MOI of 0.01 for 72 h and ultrathin sections were imaged by TEM. Upper panel: Ultrathin section of YGNNV infected GB cell with various vacuolating vesicles and nucleus (white boxed region). Scale bar = 1 μm. Lower panel: A high magnification of white boxed region shows nucleus filled with crystalline array of NNV virions. Scale bar = 0.1 μm. Golgi stacks (G), nucleus (N) and vesicles (V) are indicated. GB, grouper brain; YGNNV, yellow grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 7.

Accumulation of NNV particles in nucleus at the late infection stage of YGNNV in GB cells. GB cells inoculated with YGNNV at MOI of 0.01 for 72 h and ultrathin sections were imaged by TEM. Upper panel: Ultrathin section of YGNNV infected GB cell with various vacuolating vesicles and nucleus (white boxed region). Scale bar = 1 μm. Lower panel: A high magnification of white boxed region shows nucleus filled with crystalline array of NNV virions. Scale bar = 0.1 μm. Golgi stacks (G), nucleus (N) and vesicles (V) are indicated. GB, grouper brain; YGNNV, yellow grouper nervous necrosis virus; hpi, hour post-infection; MOI, multiplicity of infection; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).