1. Introduction

Halarachnidae marine mites Oudemans, 1906 (Acari: Parasitiformes: Mesostigmata: Dermanyssoidea) are obligate endoparasites that infest the respiratory tract of pinnipeds (Fain 1994). As such, they are exposed to a stable host internal medium. However, mites are also challenged to cope with changing conditions of available oxygen in the nasal cavity whenever hosts dive. Hosts present a “dive response” which are a set of physiological responses that allow prolonged apneas, with a significant reduction of blood flow to several organs, bradycardia and a peripheral vasoconstriction that saves blood oxygen for the central hypoxia intolerant organs such as the lungs, heart and brain (Kaczmarek et al. 2018). So, whenever hosts dive, the available oxygen is reduced. Mite larvae oxygen uptake occurs firstly by diffusion through the cuticle since they do not have well developed trachea (Doetschman 1944).

Besides being exposed to the conditions inside the hosts, larvae can be expelled through sneezing in response to nasal inflammation and congestion of the upper respiratory mucosa of hosts when heavily infested (Furman and Smith 1973; Kim et al. 1980). Hence, after being expelled, Halarachindae larvae must survive environmental conditions like variable temperatures, dehydration or changes in salinity if they fall in the intertidal zone. Then, active crawling larvae must find the nostrils of a new host (Furman and Smith 1973). Very little information is available on the survival of mites under different stressful conditions of oxygen, humidity or salinity (but see Herzog 2025).

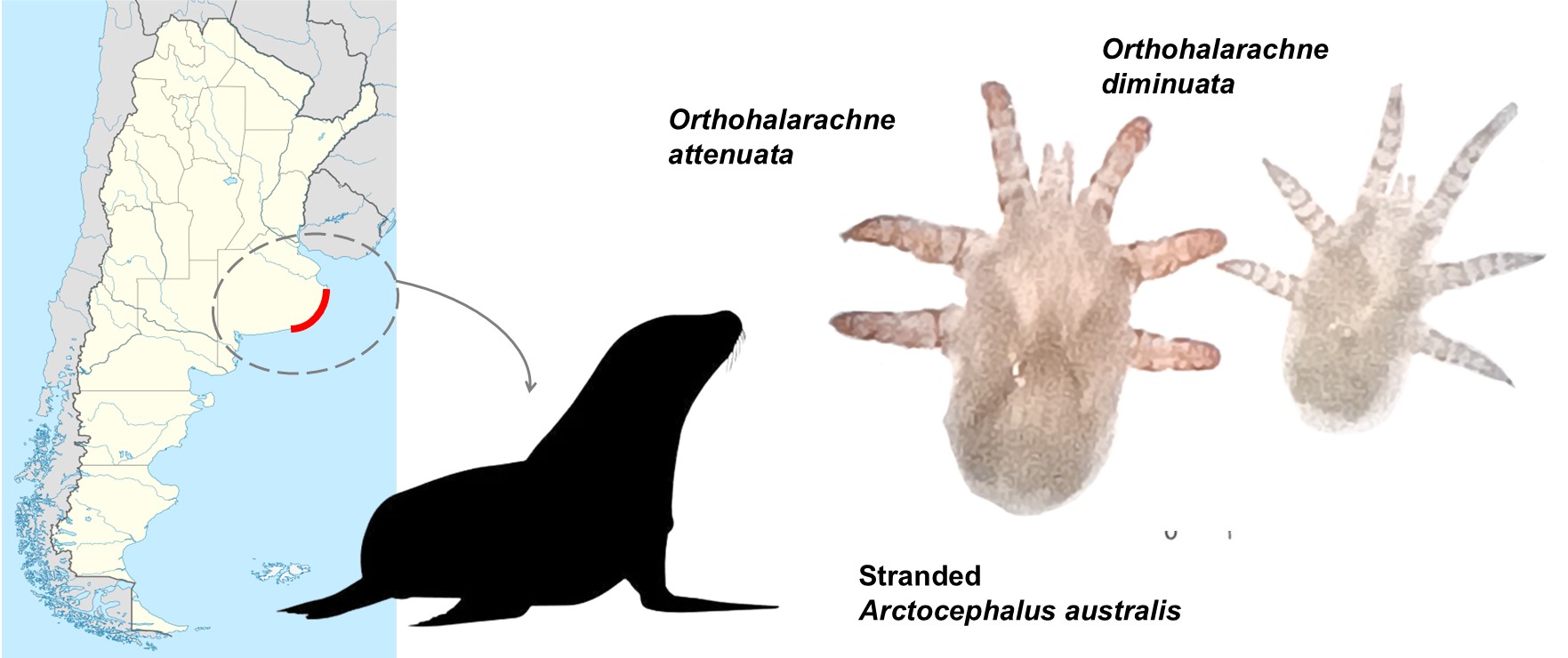

Orthohalarachne attenuata (Banks, 1910) and O. diminuata (Doetschman, 1944), are the two known species that infest Arctocephalus australis (Zimmermann, 1783) (South American fur seal) and Otaria flavescens (Shaw, 1800) (Southern sea lion) (Carnivora: Otariidae) in South America (Finnegan 1934; Katz et al. 2012; Gastal et al. 2016; Duarte-Benvenuto et al. 2022; Rivera-Luna et al. 2023; Porta et al. 2024, Castelo et al., in revision). Both mite species can co-occur in the same host but the final anchorage location of the adult stage to the host is different. Adults and larvae O. attenuata reside in the turbinates and nasopharyngeal mucosa, whereas O. diminuata adults are found in the lungs, larvae in the turbinate mucosa, and nymphs are less observable and are thought to migrate along the tract (Kim et al. 1980).

Adults are almost motionless and they live all their life attached to the respiratory mucosa of the hosts. Larvae are the dispersive stage and can exit the host during nose-to-nose contacts or be expelled to the exterior where they must survive to the environmental conditions, to locate and infest a new host (Furman and Smith 1973; Kim et al. 1980). If sneezing as a dispersal mechanism is an important way of transmission, larvae would be exposed to a wide range of temperatures besides that experienced in the inner host. It has been already shown that albeit with interspecific differences, larvae of both species can tolerate a wide range of temperatures compatible with this way of transmission (Castelo et. al., in revision). However, it is unknown if larvae can tolerate the changes in available oxygen when hosts dive or how changes in humidity and salinity influence survival whenever larvae are expelled from the hosts.

So, in this work we studied the response of O. attenuata and O. diminuata from A. australis to immersion and the survival of mite larvae when exposed to different conditions of humidity and salinity. In particular, we aim to understand the influence that different environmental conditions can exert on the survival of mite larvae. One of the working hypotheses is that larvae should be able to tolerate periods of hypoxia given that hosts dive frequently for feeding. Then, we hypothesize that there are interspecific differences in tolerance to different conditions of humidity and salinity between larvae of O. attenuata and O. diminuata. However, both species will show enough tolerance to allow them to locate new hosts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical note

No licences or permits were required for this research. Hosts used during the experiments were only those that died naturally in Mundo Marino Foundation’s Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre. During experiments the mite larvae were not harmed. After the experiments, larvae were kept in physiological solution until death.

2.2. Mites

Stranded

A. australis hosts were found in localities of Buenos Aires province coast, Argentinean Sea, Argentina, in August 2025, and taken for recovery to Mundo Marino Foundation’s Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre (

Figure 1A). Whenever a host died, they were kept in a fridge at 3°C until the performance of the necropsy to separate the respiratory system (

Figure 1B). After performing the necropsies, the turbinates and nasopharyngeal tissues were separated (

Figure 1C). Then,

O. attenuata and

O. diminuata larvae were manually collected using forceps and a paintbrush in glass Petri dishes with 0.9% NaCl saline solution (Tecsolpar®) under a stereomicroscope. Mites were taxonomically identified (Kim et al. 1980; Rivera-Luna et al. 2023; Shields et al. 2024). A piece of cloth and fabric was placed at the base of the Petri dish to allow mites to attach (

Figure 1D). Saline solution was replaced every day. Mites were kept at a room temperature of 25 ± 1ºC and a 12:12 light/dark cycle until used in the experiments. In total, mites from four different hosts were used (ID M9425 and M10025 adult females, M9625 and M9925 juvenile females)

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Response of Mites to Hypoxia and Humidity

In order to determine the ability of O. attenuata and O. diminuata to endure hypoxia conditions, we set up an experimental device consisting of a modified SB type acrylic vacuum desiccator (Sanplatec Corp., Japan). This chamber has internal dimensions of 20×20×19.5 cm with a lid fitted with a silicone gasket to ensure that the sealed chamber is completely hermetic. The lid also has a valve with a nozzle and a vacuum gauge measuring system. The chamber was modified to be fully controlled by the low cost and easy to use Arduino technology, which has already been used in the laboratory to develop other experimental devices. We used an Arduino UNO with a BMP085 pressure sensor (Bosch) to take measurements of the barometric pressure. A vacuum pump (DvrII, DOSIVAC, Argentina) was connected to the chamber’s valve system through a tube and controlled by the Arduino through a solid-state relay.

First, we studied if larvae of O. attenuata and O. diminuata are capable of surviving hypoxic conditions. To this, we exposed larvae to a chamber pressure of 100 hPa for 10 minutes. Larvae were placed in individual eppendorf type tubes of 0.5 ml, either filled with physiological solution (N = 8 O. attenuata, N = 16 O. diminuata) or in dry conditions (N = 6 O. attenuata, N = 11 O. diminuata). For the dry-conditions assays, we perforated the lids of the tubes adding a mesh fabric to prevent the mites from escaping. In each trial, tubes were placed in a rack inside the chamber. After the time elapsed, we evaluated the status of the larvae and considered that a larva was alive if it was turgid and it showed movement of appendages after gentle disturbance with a small paintbrush. If the larva was flabby and it showed no sign of movement, it was considered dead.

Given that larvae survived just fine to one exposition of hypoxic conditions, we then exposed larvae to increasing times of 60 mins (N = 13 O. attenuata, N = 12 O. diminuata), 300 mins (N = 12 O. attenuata, N = 13 O. diminuata) and 960 mins (N = 20 O. attenuata, N = 15 O. diminuata) to an air pressure of ~1 hPa. We placed larvae in the same tubes as before but only in the dry condition. The reason for only using dry conditions is that with our setup we are confident that we are manipulating air pressure. Dissolved oxygen was not directly measured since the BMP085 sensor measures air pressure. As before we evaluated the status of larvae after the exposure time elapsed.

Finally, we evaluated the effect of hypoxia and humidity on survival of larvae. To this, we placed larvae in 2ml vials with a small piece of plastic mesh netting according to the treatments depicted in

Table 1. In each vial, except for the air treatment, three drops of saline solution were introduced with a pipette, enough to cover the larva. Larvae were evaluated every 24h for 96h following the same criterion as before and its survival registered. To generate a hypoxic medium we boiled saline solution for 15 min and placed three drops of this solution with a pipette into the vials. Since the vials were closed, equilibrium with atmospheric air would not be reached. However, since we opened each flask every 24h to check for survival of larvae, air could perhaps get inside the flasks during that small amount of time that the flask was open. So, we performed another control series only with

O. attenuata larvae because it was the only species that we had enough larvae to test. In this control we exposed larvae to hypoxic saline solution as before, but larvae were checked at 24h (N = 30), 72h (N = 6) and 168h (N = 6). Since the flasks were opened only at the end of the time of exposure, we were sure that no oxygen exchange occurred until larvae were evaluated.

2.3.2. Response of Mites to Salinity

In order to study the influence of salinity on the survival of

O. attenuata and

O. diminuata larvae, three solutions with different levels of salinity were tested (

Table 2). As a control, we used 0.9% NaCl saline solution which is isosmotic to the respiratory mucosa of the host. Then, we exposed larvae to either a solution of tap water (hyposmotic solution) or salted water (hyperosmotic solution). Salted water was generated adding 35 g/L of NaCl to distilled water. Mite larvae were placed individually inside 2ml vials with a small piece of plastic mesh netting allowing them to attach. Three drops of each solution was put inside each vial to cover all the mite body. Mites were then kept at a temperature of 7 ± 1°C. Individuals were assessed for survival every 24h for 96h. As before, larvae were considered dead if no movement of appendages or lack of body turgor was registered after a gentle touch with the paintbrush.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In order to study if larvae are capable of surviving hypoxic and different humidity conditions GLM models were performed. The probability of mite larvae to survive was analyzed with a generalised linear model (GLM) with logit link function and binomial distribution. The logit link function ensures fitted values between 0 and 1, and the binomial distribution is typically used for probability data. If the mite larva showed any movement it was counted as alive with a 1, otherwise it was assumed dead and a 0 was registered.

To study the response of larvae to hypoxic conditions (100 hPa), predictors used were treatment (fixed categorical predictor with two levels, saline solution and dry) and species (fixed categorical predictor with two levels, O. attenuata and O. diminuata). Then, in order to study the influence of exposure time to hypoxic conditions on survival (1 hPa in air), the model included species as a predictor (fixed categorical predictor with two levels), time of exposure (fixed continuous predictor). The models included fixed factors and their interaction.

To study the effect of hypoxia and humidity on larvae survival, we constructed a Cox Proportional Hazards Model. We evaluated the influence of the medium (with levels air, hypoxic solution, and saline solution) on the hazard rate. As a stratification variable we included the species. Stratification allowed each species to maintain its own baseline hazard function, ensuring that the model accurately accounted for inherent species-specific differences in survival time. The response variable was the time to death (in h), with the event status (death or censoring) coded in the status variable. When evaluating the assumption of proportional hazards, we found a significant violation for the medium predictor (P = 0.047). Hence, as this indicated that the effect of the medium on the risk of mortality was not constant over the observation period, we incorporated a time dependent covariate for the medium. In this way, we explicitly modelled the interaction between the medium levels and the log of time, allowing the Hazard Ratio (HR) for each treatment to vary temporally. The concordance of the model was calculated as a measure of the discriminatory power of the model. Given that while checking survival on the hypoxic saline solution the vial was opened for a short time and it could allow some air get inside, we analysed the proportion of live larvae in saline solution, hypoxic saline solution and hypoxic control solution at 72 and 96h by means of a Fischer’s exact test with monte carlo simulations to account for small number of replicates in some of the groups.

Finally, to analyze the effect of salinity on larvae survival, we constructed a Cox model as before. In this model, the medium (with levels of saline solution isosmotic, hyposmotic and hyperosmotic) and the species (with levels O. attenuata and O. diminuata) were evaluated. In this case, the model was in accordance with the assumption of proportional hazards. The response variable was the time to death (in h), with the event status (death or censoring) coded in the status variable. The concordance of the model was calculated as a measure of the discriminatory power of the model.

All the analyses were done using the R v4.1.2 software (R Core Team 2021). The packages glmmTMB and survival were used to fit the models (Brooks et al. 2017; Therneau et. al. 2021). For testing model assumptions, we used the package DHARMa (Hartig & Lohse 2021). To test overdispersion we used the function check_overdispersion of the package performance (Lüdecke et al. 2021). Graphs were done using the package ggplot2 (Wickham et al. 2020) and ggsurvfit (Sjoberg et al. 2024). Tukey contrasts were performed with the emmeans function of the package emmeans (Lenth et al. 2020).

3. Results

3.1. Response of Mites to Hypoxia and Humidity

In the first experiment, larvae were exposed to 100 hPa for 10 minutes. Both species showed a high recovery to these conditions. In fact, all larvae recovered except one larva of

O. attenuata exposed to air. The second experiment in which larvae were exposed for different amounts of times to 1 hPa of pressure showed that time of exposure has an influence on survival similarly for both species (Supplementary

Table 1). In fact, we found that for each minute of exposure the probability of survival of an individual larva was reduced on average by 0.21% (CI : 0.04% - 0.38%).

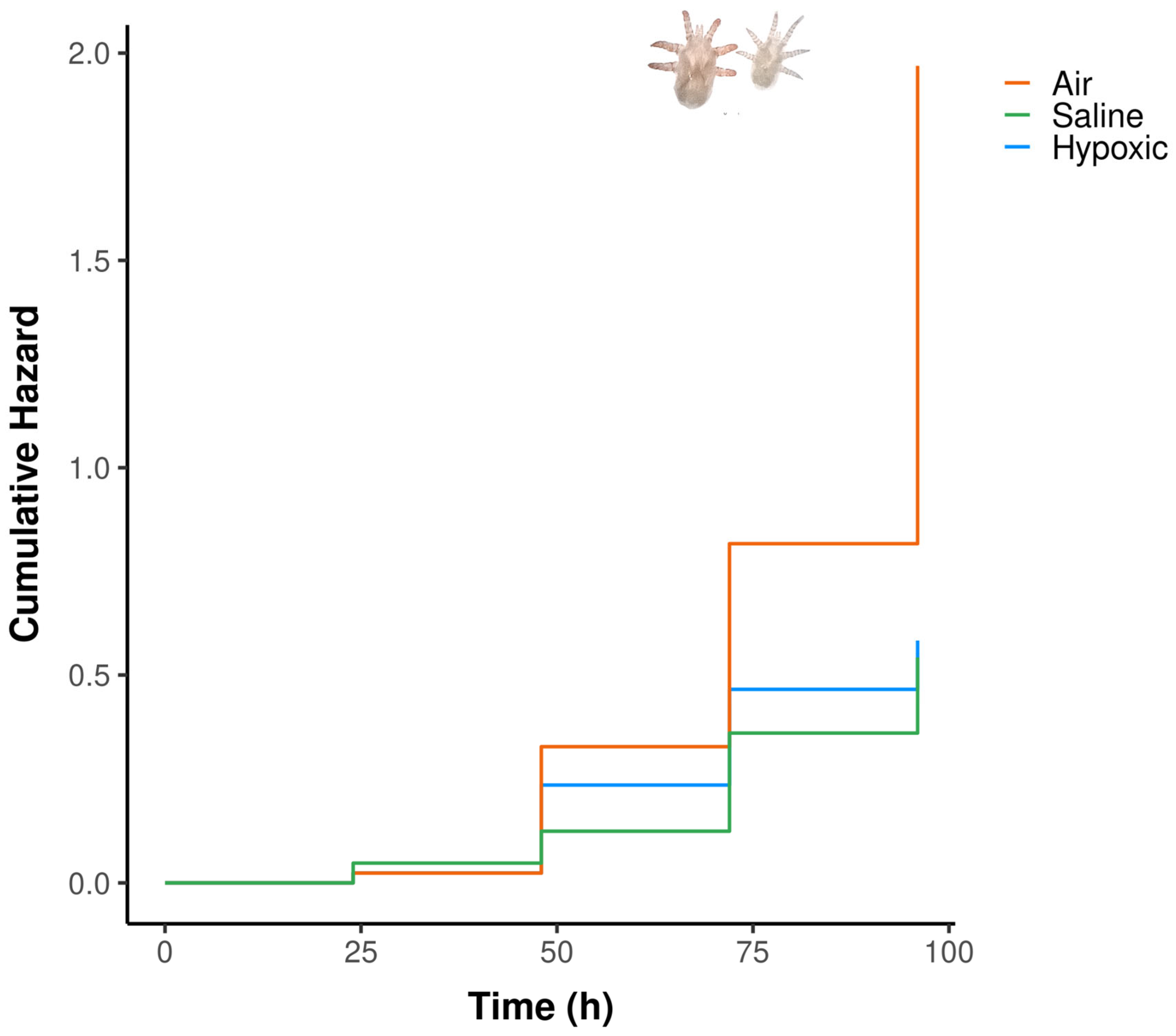

For the third experiment, in which we evaluated survival through time of larvae exposed to different treatments of hypoxia, we found a high overall significance of the model (Ꭓ

24 = 22.39, p<0.001). The air treatment showed a strong initial lower risk of dying (99.70% lower risk) compared to saline solution (β

air_1h= -5.90, p = 0.077, Hazard Ratio = 0.003, Supplementary

Table 2,

Figure 2). However, as time progressed, air treatment death hazard increases significantly compared to saline solution (β

air= 1.64, p = 0.0397, Hazard Ratio = 5.170, Supplementary

Table 2,

Figure 2). By the end of the experiment, air treatment showed the highest cumulative hazard. Hypoxic solution did not show any differences compared to saline solution (β

hypoxic_sol= 0.44, p = 0.606,

Figure 2), indicating a similar hazard ratio. The concordance of the model was 0.626 indicating a moderately good discriminatory power. Regarding the hypoxic solution, the fact that we opened the vial for every observation did not generate any inflated survival as the proportion of alive larvae between the hypoxic solution and the hypoxic control solution at 48 and 96h were similar (Fischer’s exact test P value = 0.6127).

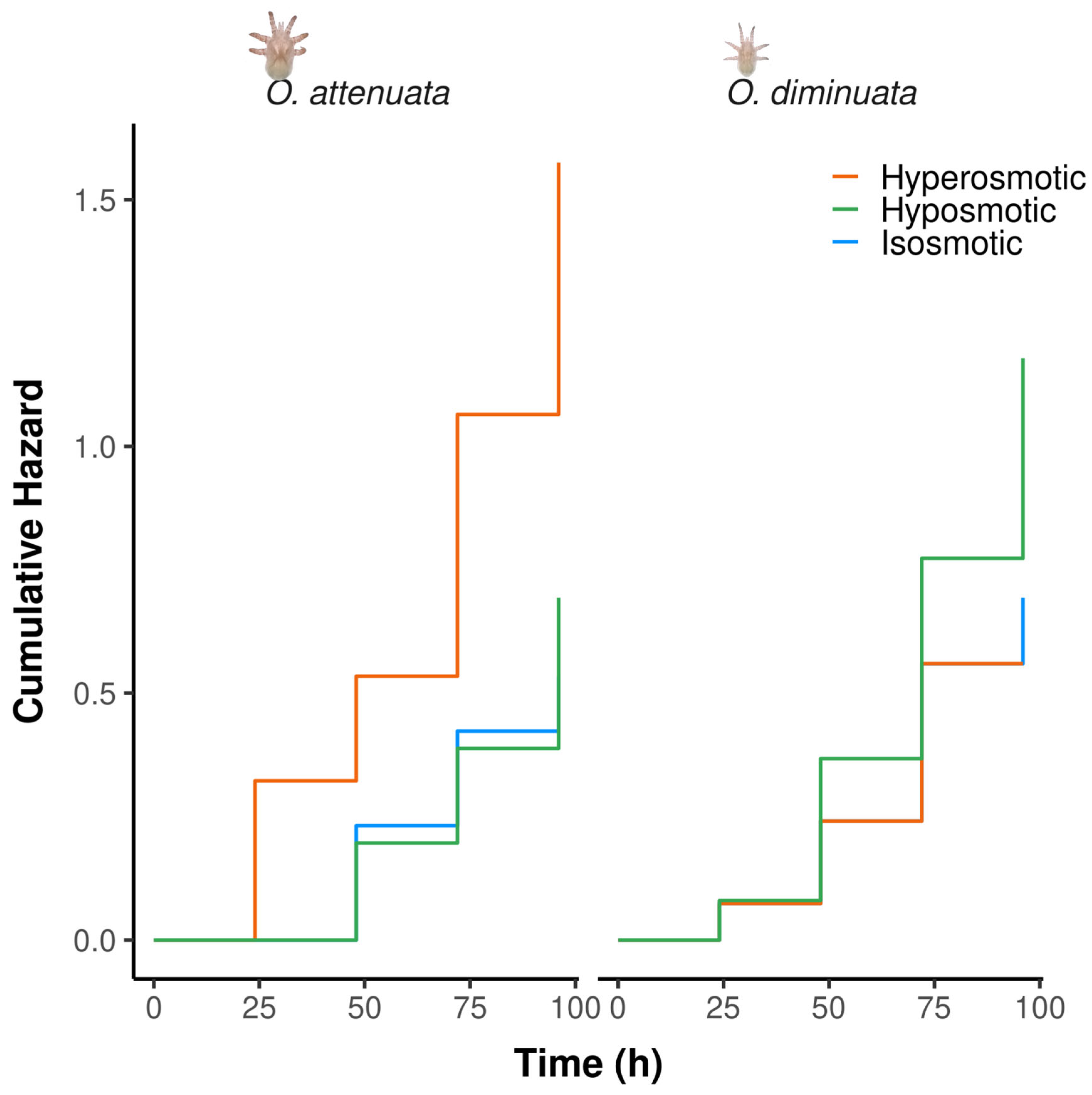

3.2. Response of Mites to Salinity

The level of salinity in the solution showed that there are differences between species in survival (

Supplementary Table S3). For

O. attenuata, hyperosmotic solution showed the highest cumulative hazard (

Figure 3). In fact, the hazard ratio between hyperosmotic solution and both isosmotic and hyposmotic solution showed that the hazard rate of

O. attenuata larvae is higher (

Table 3). On the contrary,

O. diminuata showed similar levels of hazard rates between all the treatments and similar levels of cumulative hazard (

Table 3,

Figure 3). The concordance of the model was 0.627 indicating a moderately good discriminatory power.

4. Discussion

In this work we studied the recovery response of O. attenuata and O. diminuata larvae from A. australis to simulated host immersion and their survival when exposed to different levels of humidity and salinity. We found that the larvae of both species are very resistant to hypoxia conditions. Also, both species are highly susceptible to dehydration. However, we found that O. attenuata is more sensitive to changes in salinity than O. diminuata.

We first asked if larvae could survive a short exposure to low oxygen concentration in saline solution in order to understand the effect that apnea during host immersions could generate on mite larvae inside the nasal cavities. As expected, all larvae except one recovered completely. Then, we exposed larvae to more extreme conditions during increasing exposure times. We found that both species could withstand long times under hypoxia in air (~16h) although survival decreased through time. Combined, these results indicate that larvae are well adapted to host apnea conditions during immersions. Arctocephalus australis has several immersions to locate food but their dives usually last between 6 - 8 minutes (Kooyman et al. 1981). However, exposure to air for several hours killed some larvae indicating that humidity is an important factor for survival.

So, we then studied long term survival of larvae exposed to either direct air or hypoxic saline solution in order to understand the role that humidity has on survival. Our results show that humidity rather than oxygen availability is a constraint for survival. Within the host, larvae are attached to the turbinates humid mucosa (Furman and Smith 1973). The mucosa provides food but also is the medium larvae use in order to take oxygen. Mite larvae do not have developed trachea nor a plastron as adults (Doetschman 1944). Although the respiratory mechanism is poorly studied in larvae of these mites, they probably have cuticular respiration ((Doetschman 1944)). Cuticular respiration in arthropods is common in small, aquatic, or very humid terrestrial species and depends entirely on humidity for oxygen to penetrate the thin, permeable cuticle by diffusion and diffuse into the tissues. If the cuticle dries out, diffusion stops, potentially causing asphyxia. There are several examples of aquatic insects that use cuticular respiration (Jones et al. 2019). The fact that larvae survive to hypoxic conditions could indicate that either larvae have a very low metabolism and can survive with just the smallest amount of oxygen that could have entered in the vials when we evaluated survival or that they can survive very long times without exchanging oxygen. Our control series exposing larvae to hypoxic conditions without allowing any oxygen exchange showed similar results as the hypoxic solution treatment, supporting the idea that larvae survive long times without exchanging oxygen, perhaps due to a very low metabolism. In fact, cuticular respiration poses two types of resistance for O2 diffusion from water to the tissues. On one side, a water layer just above the respiratory surface which is deficient in O2 provides resistance to diffusion (Jones et al. 2019). On the other side, the cuticle itself can act as a diffusion barrier (Jones et al. 2019). Hence, arthropods with cuticular respiration are expected to have low metabolic rates and even smaller sizes than arthropods with specific breathing structures (Jones et al. 2019; Leggett et al. 2024; Preuss et al. 2026).

Parasite mites of semi-aquatic mammals, such as pinnipeds, must complete their life cycles alternating between terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Mite larvae are the dispersal phase and are usually expelled when the hosts are ashore during their reproductive or molting season (Berta 2018). So, larvae experiment a radical environmental change from being attached to the turbinates mucosa to the exterior where they face variable temperatures and humidity conditions. Larvae must survive enough time to conditions of the beach, track down and move until reaching a new host. If larvae are expelled on dry sand during the daytime, larvae would be exposed to direct air and high temperatures. Under these conditions, larvae can survive exposure to high temperatures but must locate a host within the first few days before low humidity poses a threat to survival (Castelo et al., in revision and this work). However, larvae can also be expelled and may fall into the intertidal zone where they would be exposed to conditions very different from those inside the host, such as contact with salt marine water from the sea.

Salt water showed to be lethal for O. attenuata larvae but not for O. diminuata. Our results suggest that both species have different tolerances to osmolality. One possibility would be that oxygen diffusion would be impaired when exposed to a solution with high osmolality as salt water. However, our results on hypoxic solution suggest that both species can tolerate at least 96h without access to oxygen. Hence, O. attenuata seems to be more sensitive to changes in the osmolality of the surrounding solution than O. diminuata. Then, detailed descriptions on the cuticle of both species would provide useful information regarding the composition and thickness to better understand what kind of functional protection can the cuticle provide these larvae.

In conclusion, our study shed light on aspects of the ecophysiology of these endoparasites of pinnipeds that were until now poorly known. Both O. attenuata and O. diminuata larvae are well adapted to ordinary hypoxia situations like when the hosts are diving, showing adaptations to the host's way of life (as foraging behaviour). However, upon being released during dispersion outside the host to the land, prevailing environmental factors are a threat to their survival. Dehydration and exposure to salt water are two key factors that can limit dispersion, location, and colonization of new hosts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Analysis of variance table of fitted model for the effect of exposure time on survival of Orthohalarachne attenuata and O. diminuata larvae.; Table S2: Results of fitted model for the survival of Orthohalarachne attenuata and O. diminuata larvae exposed to direct air or hypoxic saline solution.; Table S3: Analysis of variance table of fitted model for the effect of exposure time in solutions with different salinity on survival of Orthohalarachne attenuata and O. diminuata larvae.

Author Contributions

Lucía Pérez Zippilli: Investigation, data curation, Writing - original draft preparation. José E. Crespo: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, formal analysis, methodology and software, supervision, Investigation, Writing - original draft preparation, writing - review and editing. Juan Pablo Loureiro: Funding acquisition, resources, project administration, supervision, methodology. Dolores Erviti: Investigation, data curation, methodology. Marcela K. Castelo: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, funding acquisition, resources, project administration, supervision, Investigation, Writing - original draft preparation, writing - review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Buenos Aires, Argentina (grant UBACyT 2020 N° 20020190100059BA, to Marcela K. Castelo), the Fundación Mundo Marino, and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the veterinarians and technicians of the Fundación Mundo Marino, especially to Juana Caferri and Julio Loureiro, for their help and collaboration in managing the samples. We also thank Gustavo Martínez and Juan Cruz Altube De Noia for their help during the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Berta, A. Pinnipeds. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third Edition); Würsig, B, Thewissen, JGM, Kovacs, KM, Eds.; Academic Press, 2018; pp. pp 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, ME; Kristensen, K; Benthem, KJ; van, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Magnusson, A; Berg, CW; Nielsen, A; Skaug, HJ; Mächler, M; Bolker, BM. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetschman, WH. A New Species of Endoparasitic Mite of the Family Halarachnidae (Acarina). Trans Am Microsc Soc 1944, 63, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Benvenuto, A; Sacristán, C; Reisfeld, L; Santos-Costa, PC; dA Fernandes, NCC; Ressio, RA; Mello, DMD; Favero, C; Groch, KR; Diaz-Delgado, J; Catão-Dias, JL. Clinico-pathologic findings and pathogen screening in fur seals (Arctocephalus australis and Arctocephalus tropicalis) stranded in southeastern brazil, 2018. J Wildl Dis 2022, 58, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fain, A. Adaptation, specificity and host-parasite coevolution in mites (Acari). Int J Parasitol 1994, 24, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnegan, S. On a new species of Mite of the family Halarachnidae from the southern sea lion. Discov Rep 1934, 7, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, DP; Smith, AW. In vitro development of two species of Orthohalarachne (Acarina: Halarachnidae) and adaptations of the life cycle for endoparasitism in mammals. J Med Entomol 1973, 10, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastal, SB; Mascarenhas, CS; Ruas, JL. Infection Rates of Orthohalarachne attenuata and Orthohalarachne diminuata (Acari: Halarachnidae) in Arctocephalus australis (Zimmermann, 1783) (Pinipedia: Otariidae). Comp Parasitol 2016, 83, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, KK; Cooper, SJB; Seymour, RS. Cutaneous respiration by diving beetles from underground aquifers of Western Australia (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae). J Exp Biol 2019, 222, jeb196659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, J; Reichmuth, C; McDonald, BI; Kristensen, JH; Larson, J; Johansson, F; Sullivan, JL; Madsen, PT. Drivers of the dive response in pinnipeds; apnea, submergence or temperature? J Exp Biol 2018, 221, jeb176545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, H; Morgades, D; Castro-Ramos, M. Pathological and Parasitological Findings in South American Fur Seal Pups (Arctocephalus australis) in Uruguay. Int Sch Res Not 2012, 2012, 586079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, KC; HAAS, VL; Keyes, MC. Populations, microhabitat preference and effects of infestations of two species of Orthohalarachne (Halarachnidae: Acarina) in the northern fur seal. J Wildl Dis 1980, 16, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooyman, GL; Castellini, MA; Davis, RW. Physiology of Diving in Marine Mammals. Annu Rev Physiol 1981, 43, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggett, MA; Vink, CJ; Nelson, XJ. Adaptation and Survival of Marine-Associated Spiders (Araneae). Annu Rev Entomol 2024, 69, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenth, R; Singmann, H; Love, J; Buerkner, P; Herve, M. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke, D; Ben-Shachar, MS; Patil, I; Waggoner, P; Makowski, D. performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. J Open Source Softw 2021, 6, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, AO; Loureiro, JP; Castelo, MK. First record of Orthohalarachne attenuata in Arctocephalus australis in mainland Argentina (Parasitiformes, Mesostigmata, Dermanyssoidea, Halarachnidae) with observations on its ambulacral morphology. Zookeys 2024, 1207, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, A; van de Kamp, T; Zuber, M; Hamann, E; Brunkert, L; Herzog, I; Lehnert, K; Gorb, SN. Comparative analysis of locomotory organs and tracheal system in Halarachne halichoeri: implications for marine parasite habits. Zoomorphology 2026, 145, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Luna, H; Kniha, E; Muñoz, P; Painean, J; Balfanz, F; Hering-Hagenbeck, S; Prosl, H; Walochnik, J; Taubert, A; Hermosilla, C; Ebmer, D. Non-invasive detection of Orthohalarachne attenuata (Banks, 1910) and Orthohalarachne diminuata (Doetschman, 1944) (Acari: Halarachnidae) in free-ranging synanthropic South American sea lions Otaria flavescens (Shaw, 1800). Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 2023, 21, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, MM; Roth, T; Pesapane, R. A pictorial key to the adult and larval nasal mites (Halarachnidae) of marine mammals. ZooKeys 2024, 1216, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjoberg, DD; Baillie, M; Fruechtenicht, C; Haesendonckx, S; Treis, T. R: ggsurvfit: Flexible Time-to-Event Figures. 2024. Available online: https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/ggsurvfit/html/ggsurvfit-package.html (accessed on 3 Oct 2025).

- Therneau, T. _A Package for Survival Analysis in R_. R package version 3.7-0. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

- Wickham, H; Chang, W; Henry, L; Pedersen, TL; Takahashi, K; Wilke, C; Woo, K; Yutani, H; Dunnington, D. RStudio (2020) ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics; s; pp. pp 733–740.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).