1. Introduction

Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is one of the most widely used bio-based and biodegradable polymers, particularly in the food packaging sector, due to its renewability, compostability, and good transparency [

1]. However, despite these advantages, PLA suffers from several inherent drawbacks that strongly limit its application in high-performance food contact materials. These drawbacks include low thermal stability, poor resistance to thermo-oxidative degradation, brittleness, and limited barrier properties against oxygen and moisture. Furthermore, PLA is prone to degradation during melt processing, leading to chain scission, molecular weight reduction, and deterioration of mechanical properties [

2,

3,

4]. To overcome these limitations, the incorporation of functional fillers has emerged as a promising strategy [

5,

6]. In this context,

Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary, RM) extract,

Arthrospira platensis (spirulina, SP) dry biomass, and

Ascophyllum nodosum (kelp, K) dry biomass were embedded into PLA matrix (same commercial sort ) at three different concentrations (0.5, 1, and 3 wt%). These additives are all accepted in the food industry, ensuring compatibility with food contact regulations while providing added functional value [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Rosemary extract is a well-known natural antioxidant widely used in the food industry to delay lipid oxidation. Its effectiveness is mainly attributed to phenolic diterpenes such as carnosic acid and carnosol, which are strong radical scavengers and metal chelators. When incorporated into PLA, rosemary extract is expected to act as a stabilizing agent during melt processing and service life, limiting thermo-oxidative degradation and slowing down polymer chain scission. This may result in improved thermal stability, reduced discoloration, and enhanced durability of the material [

11]. Spirulina is a microalgal biomass rich in proteins, polysaccharides, phycocyanin, carotenoids, and phenolic compounds. Many of these constituents exhibit antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. The use of spirulina in PLA is motivated by its potential multifunctionality [

12]. Besides acting as a bio-filler, it may provide radical scavenging capacity similar to that of plant extracts, while also contributing to mechanical reinforcement due to its particulate nature. Moreover, spirulina is already approved as a food ingredient, making it an attractive sustainable additive for food-contact bioplastics [

13,

14,

15].

Ascophyllum nodosum is a brown macroalga widely used in food and nutraceutical applications. Considered one of the fastest-growing plants, they can grow up to several meters in length. It contains alginates, fucoidans, polyphenols, and minerals that can interact with polymer matrices [

16]. Its incorporation into PLA is expected to improve stiffness and barrier properties through filler–matrix interactions, while its polyphenolic fraction may contribute to antioxidant protection. Kelp biomass thus represents a low-cost, renewable, and food-grade filler with potential performance-enhancing effects [

17].

Rosemary extract is expected to provide the strongest antioxidant effect, but spirulina and kelp may also contribute through their natural phenolic and pigment content. The presence of radical scavengers can mitigate chain scission during extrusion and molding, leading to better retention of molecular weight [

18]. Biomass fillers may act as reinforcing agents, potentially improving stiffness and impact resistance when well dispersed. Furthermore, the presence of solid bio-fillers can create tortuous paths for gas diffusion, improving oxygen and moisture barrier properties [

19].

The presented study shows comparison between a conventional natural antioxidant (rosemary extract) and emerging algal biomass fillers (spirulina and kelp). While rosemary extract is already known for its strong antioxidant efficiency, the present strategy investigates whether whole microalgal and macroalgal biomasses can provide comparable stabilization effects, combined with mechanical and barrier enhancements. This comparison enables the evaluation of algae-based fillers as sustainable, multifunctional alternatives to conventional plant extracts. The incorporation of Rosmarinus officinalis extract, Arthrospira platensis, and Ascophyllum nodosum into PLA at different loadings is a scientifically justified and industrially relevant strategy to overcome the intrinsic limitations of PLA. By using fillers already accepted in the food industry, this approach ensures regulatory compatibility while introducing antioxidant, reinforcing, and barrier-enhancing functionalities. The comparative assessment of rosemary extract versus algal biomasses further contributes to the development of next-generation, fully bio-based and functional packaging materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

High-molecular-weight poly(lactic acid) pellets, Ingeo™ Biopolymer 2003D, were purchased from Nature Works LLC (Minnetonka, MN, USA) with a density of 1.24 g∙cm-3 and a melt flow index of 6 g/10 min (210 °C, 2.16 kg). The dry rosemary biomass and the algal biomass in powder form with 5.8 ± 0.5% (w/w) moisture content were purchased from Hyperici Pharm SRL, Târgoviște, Romania. All reagents used in the experiment were of analytical grade and were purchased from Fisher Scientific.

The additive powders:

Rosmarinus officinalis (RM),

Arthrospira platensis - spirulina (SP), and

Ascophyllum nodosum (K) were embedded in three different concentrations (0.5, 1, and 3 wt%) by their solubilization into the mother solution of PLA in chloroform. The rosemary extract was prepared using a Soxhlet extraction method with 96% ethanol as the solvent. After the extraction process, the solution was allowed to cool, during which a substantial amount of yellowish-white precipitate formed. This precipitate was separated from the liquid phase by filtration. The collected solid was then placed in an oven and dried at 80 °C for 4 hours to ensure complete removal of residual solvent. The notation of the samples, as correlated with the experimental procedure, is presented in

Table S1 (Supplementary Material).

2.2. Sample Preparation

The PLA samples were dissolved in chloroform to obtain homogeneous solutions. The fillers were then added and the mixtures were thoroughly dispersed. Each solution was cast into a round Petri dish to form a thin film, and the solvent was allowed to evaporate at room temperature. After drying, the resulting films were cut into small chips, which served as test specimens for the subsequent measurements.

2.3. Thermal Ageing

Thermal ageing of PLA specimens was carried out in an electrical drying oven (model 15-103-0508, Fisher Scientific, Campus Drive, Mundelein, Illinois, USA) at 80 °C for three heating cycles of 8 hours each. The ageing temperature of 80 °C was selected because PLA is commonly used in food industry applications at temperatures below this threshold. Above 60–70 °C, PLA begins to soften and lose mechanical strength, making 80 °C a relevant condition for evaluating thermal stability.

2.4. Chemiluminescence

The evaluation of thermal stability in correlation with the antioxidative efficiency was accurately accomplished by both chemiluminescence procedures [

20,

21]: isothermal determinations, when the progress of oxidation is monitored at constant temperature, and nonisothermal measurements, when the collection of expelled photons is visualized over the whole temperature range is swept. The chemiluminescence (CL) spectrometer that has low error for the temperature measurements (± 0.3 °C) and photon counting (± 50 Hz sec

-1) was purchased from the Polymer Institute, Slovak Academy of Science, Bratislava, Slovakia. The selected values of heating rate used in our CL measurements are 5, 10, 15, and 20 °C min

-1, while the value of temperature applied in the isothermal CL investigation is 170 °C, when the oxidative degradation progresses at a convenient rate. This temperature is placed over the melting range (140-155 °C, according to the technical sheet of the product), allowing degradation to be inspected by isothermal CL in the liquid state.

2.5. FTIR Analysis

The spectral data were recorded on Vertex 80 infrared spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) provided with an ATR investigation system. The scanning range was 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1 at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans.

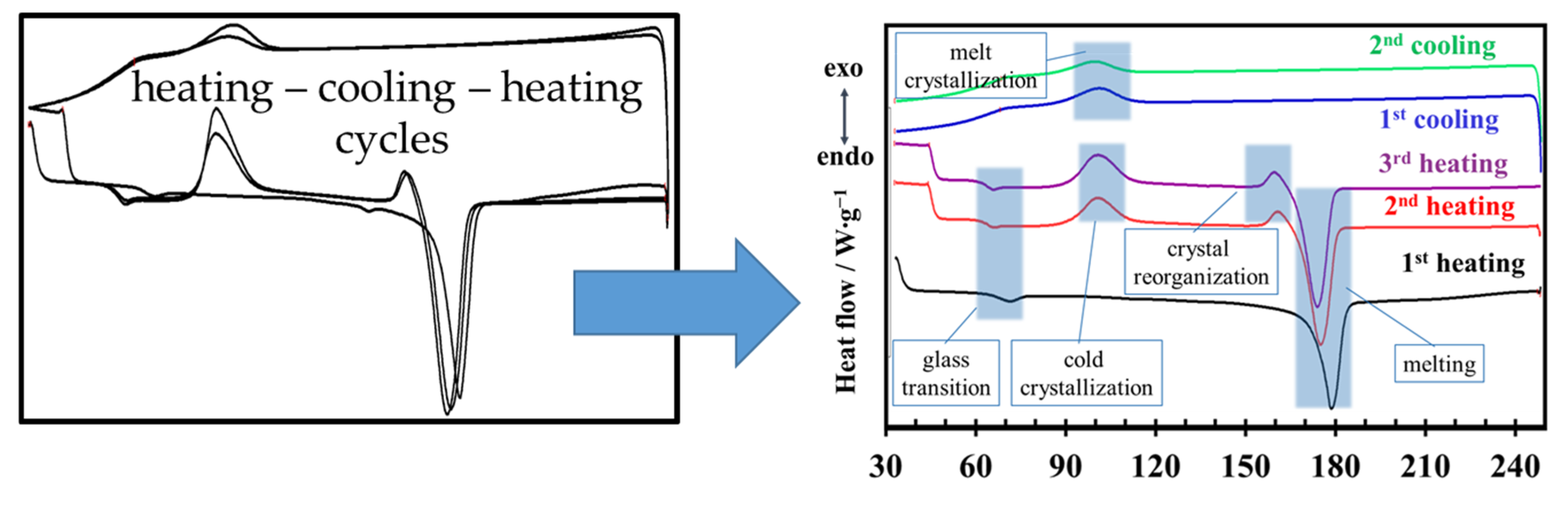

2.6. DSC Analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were performed using a DSC 3+ STARᵉ system (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland). The polymer samples were analyzed over a temperature range of 30 to 250 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min⁻¹. Approximately 10 ± 1 mg of each sample was weighed using a Secura 225D-1CEU analytical balance (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) with a precision of 1 × 10⁻⁵ g, and placed in standard 40 µL aluminum pans. An empty 40 µL aluminum pan was used as the reference. Recorded thermograms were then processed with the use of StarE software v. 20.00 (Mettler Toledo GMBH), and thus thermal characteristic parameters were calculated.

3. Results

PLA is a versatile biopolymer with a wide range of applications [

22], including medical textiles, food packaging, and polymer recycling. It also serves as an excellent substrate for composite production [

23]. During oxidative degradation, PLA exhibits a distinctive behavior characterized by two competing radical-driven processes resulting from macromolecular fragmentation: (i) oxidation, similar to that observed in hydrocarbon polymers [

24], and (ii) continuous fragmentation through a backbiting mechanism, forming cyclic oligomers [

25]. The interplay between these processes provides insight into the material’s ageing state [

26,

27]. Incorporating antioxidants into PLA formulations is a key strategy for enhancing durability [

28], as these additives improve stabilization against oxidative degradation. However, the performance of PLA modified with specific antioxidants may also reveal the polymer’s inherent tendency toward depolymerization [

29]. At elevated temperatures (≈180–250 °C), backbiting becomes the dominant degradation pathway, causing molecular weight reduction, increased melt flow index, formation of volatile cyclic lactide, and loss of mechanical and thermal properties. Furthermore, thermal analysis of additives offers valuable information regarding product quality at different stages of the circular economy [

30].

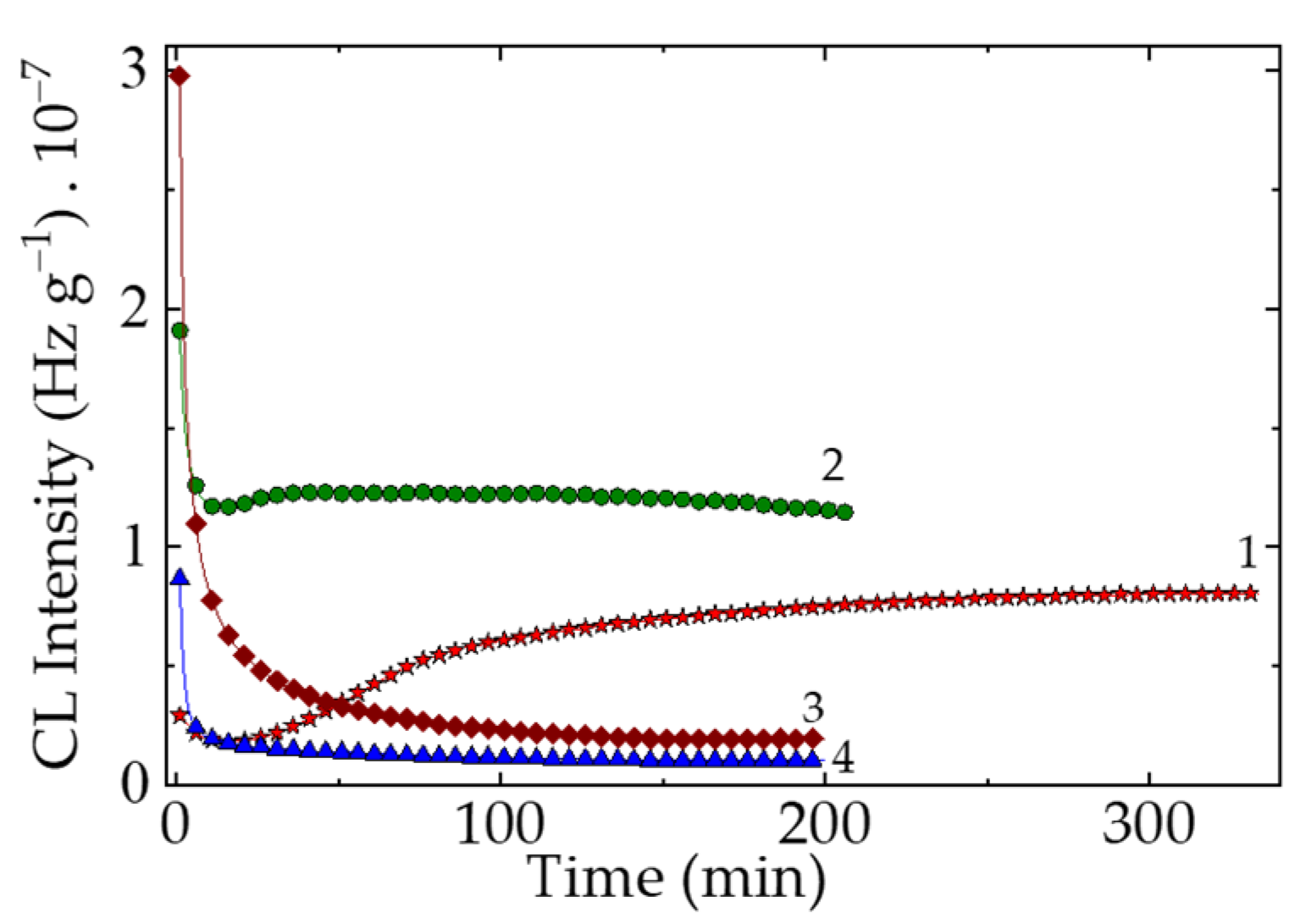

3.1. Isothermal CL Measurements

Isothermal CL measurements are used to assess the sensitivity of materials to oxidation at specific temperatures. This susceptibility is quantified by the oxidation induction time (OIT), which indicates the thermal stability of the sample. Additionally, the oxidation rate (

vox), representing the progression of degradation during the propagation stage, can be determined from the slope of the CL curve. The relative positions of the isothermal CL curves reflect the stability ranking of the samples and the reactions occurring during oxidation propagation.

Figure 1 illustrates how sample formulation influences degradation behavior, acting as a structural factor that delays oxidation by hindering the conversion of molecular fragments into hydroperoxide-derived products. The shapes of curves 2–4 suggest that the additive contributes to inhibiting free radical oxidation, whereas the pristine polymer begins to oxidize after approximately 20 minutes (

Figure 1).

The stabilization efficiency of PLA is closely linked to antioxidant activity. Antioxidants interfere with oxidation processes, shortening the time required to reach the steady ageing state and indicating how rapidly the material may degrade. In pristine PLA, oxidation and depolymerization remain in competition for more than 100 minutes, despite an oxidation induction time (OIT) of only 10 minutes. Polymer degradation alters the balance between free-radical generation and hydroperoxide accumulation, which initiates the oxidation chain. As shown in

Figure 2, pre-heating affects PLA modified with natural antioxidants by changing the relative contributions of two key processes: the antioxidative action of the additives and the accumulation and evolution of lactides and polylactides as stable end products.

The essential modifications of material structure by thermal treatment in air lead to an increase in the amount of hydroperoxide that corresponds to the activity of the additive. The comparison of oxidation period for the two states of PLA degradation suggests that the material stabilization is effectively done in the first 50 minutes of measurements.

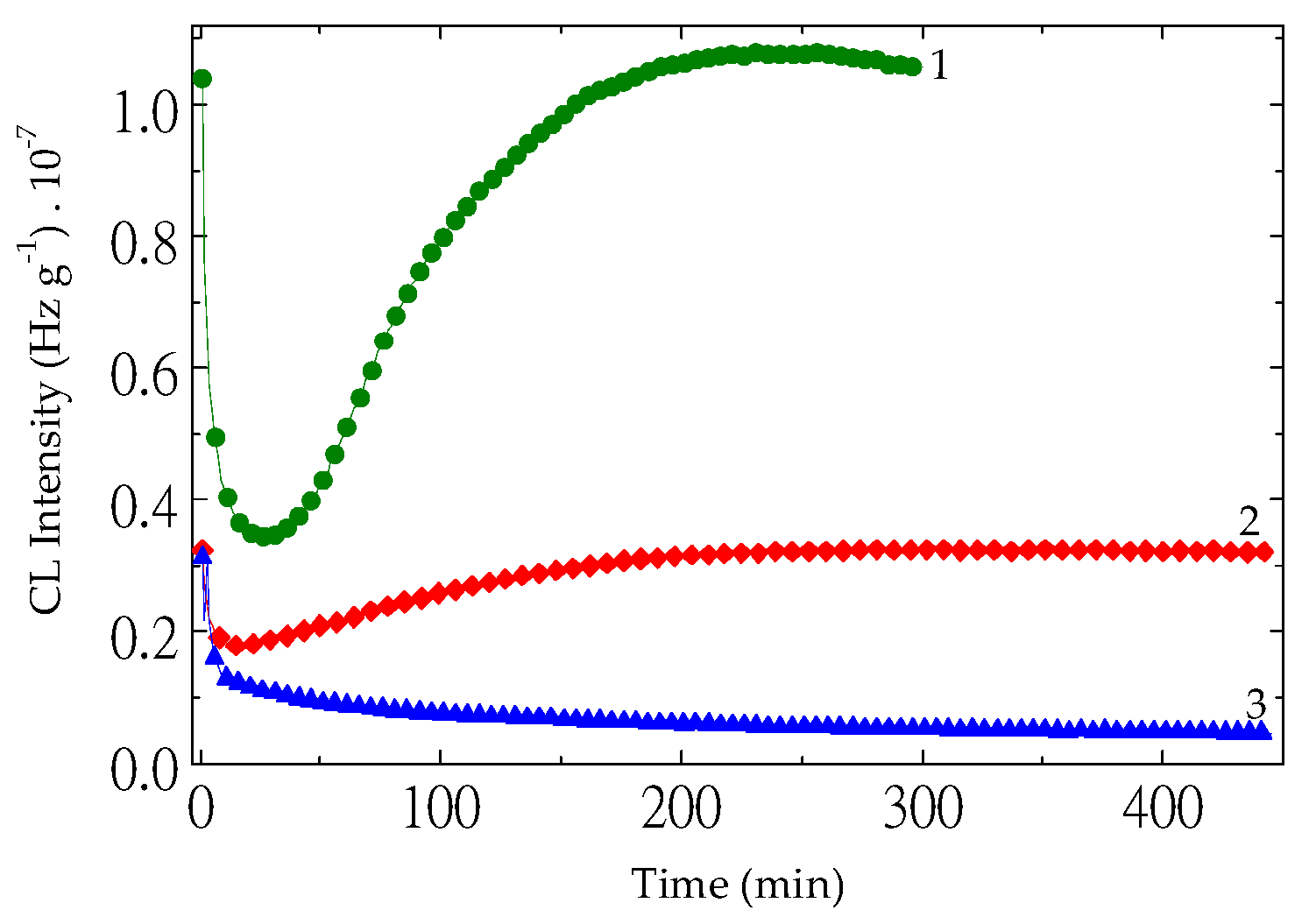

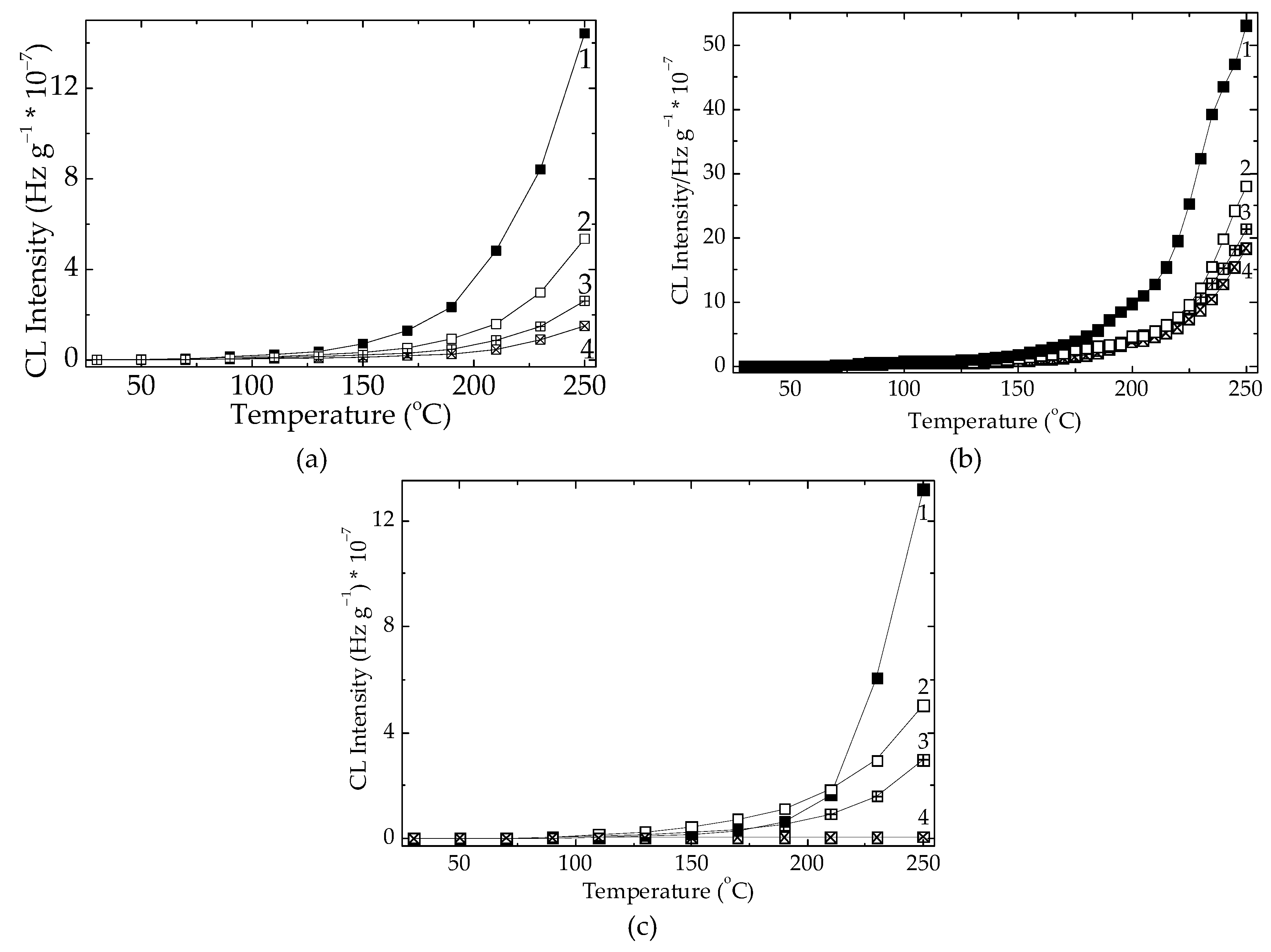

The effects of concentration brought about by each of the studied AOs are revealed in

Figure 3. The functioning of the additive indicates the opposite contributions that increase of the stabilization activities as their loadings enhance [

31]. The reason for this discrepancy involves the competition of the two ways of behavior: stabilization and inactivity, with the conversion of radical intermediates into lactides as final degradation products.

As it may be observed, there are also some dissimilarities between the progress of degradation in the PLA samples containing various loadings of additives. While the lowest concentration of SP (

Figure 3c) exhibits its antioxidant properties, determining a long OIT (41 minutes), the other measurements display a continuous decrease of the emitted photons during the CL measurements, representing the controlled thermal ageing. The other difference may be noticed between the effects brought about by K and RM. They do not interfere with the chain formation of lactones, because the substitution of an active proton is not possible. The decrease in the oxidation rates of PLA containing K and RM is probably due to the disagreement between the distinct levels of participation.

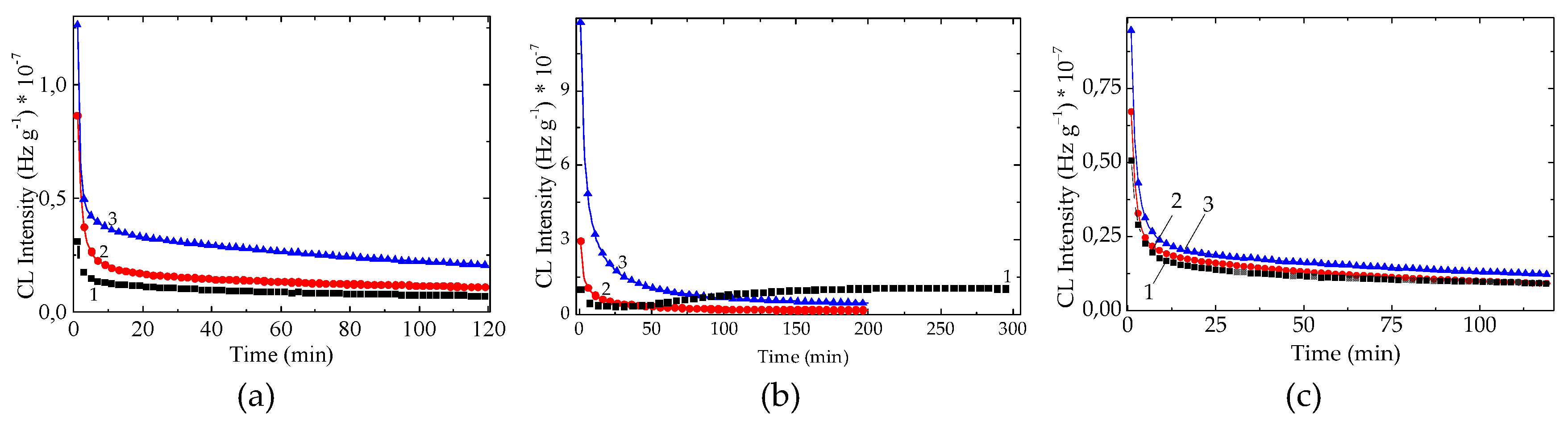

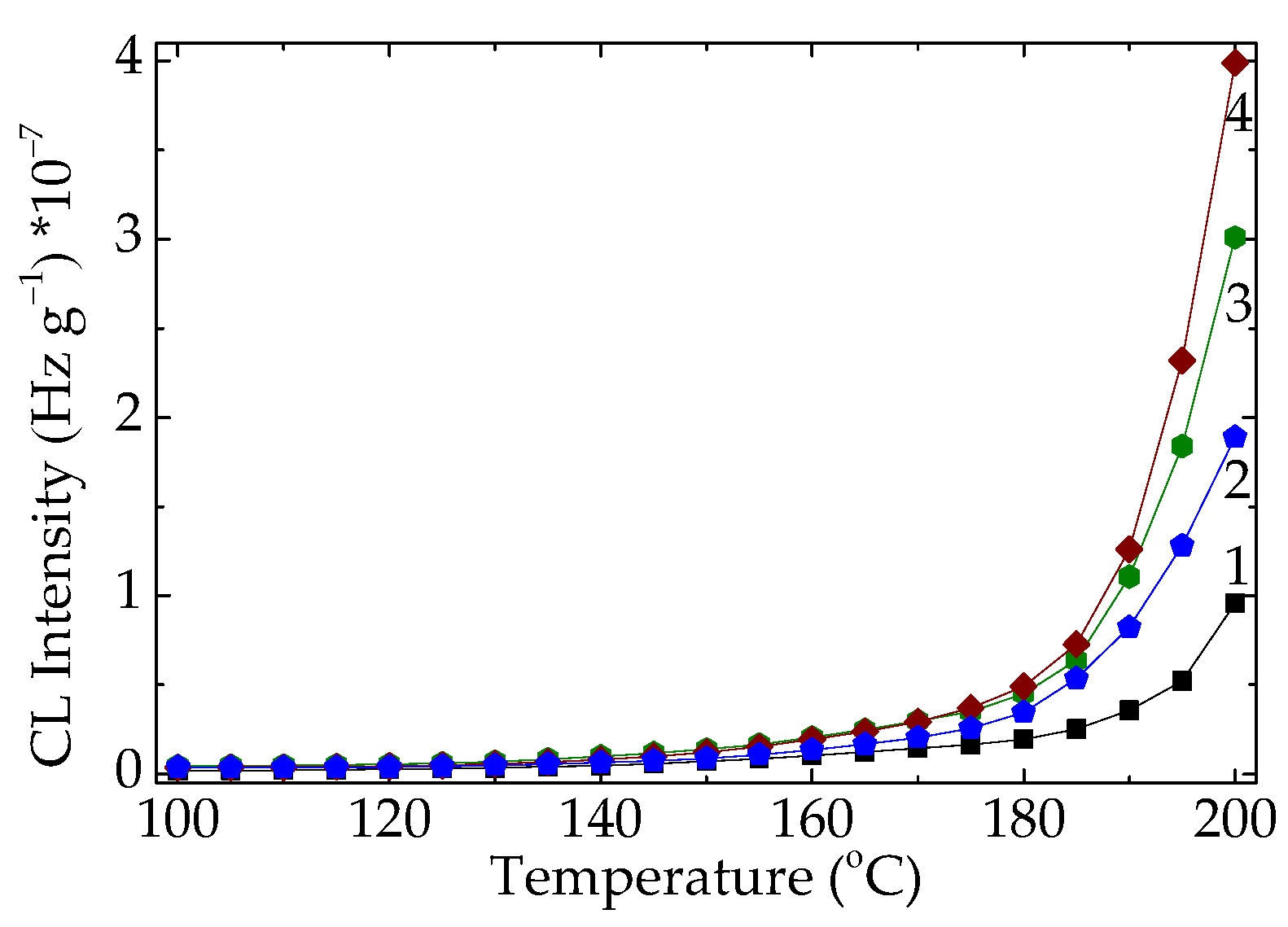

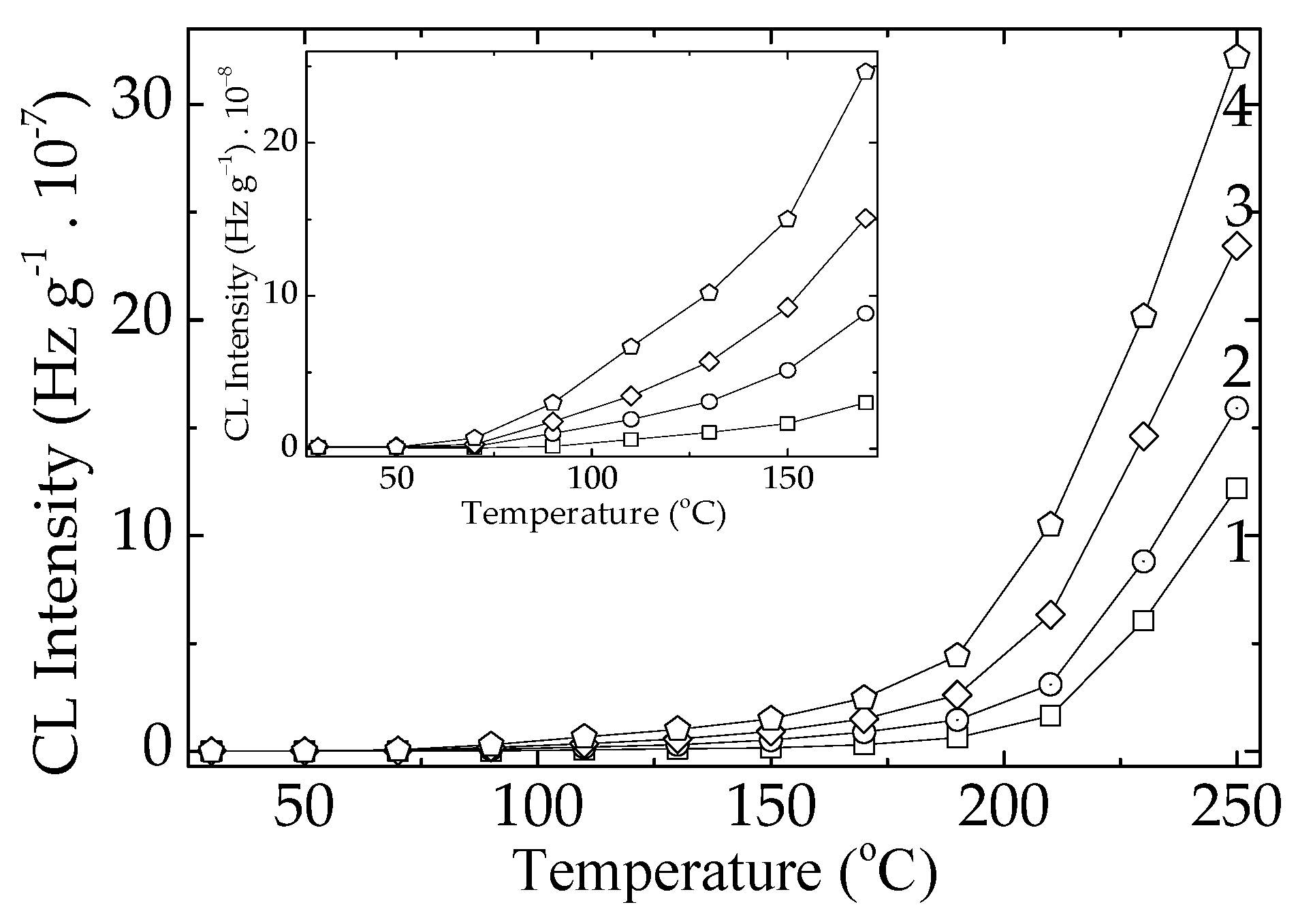

3.2. Nonisothermal CL Measurements

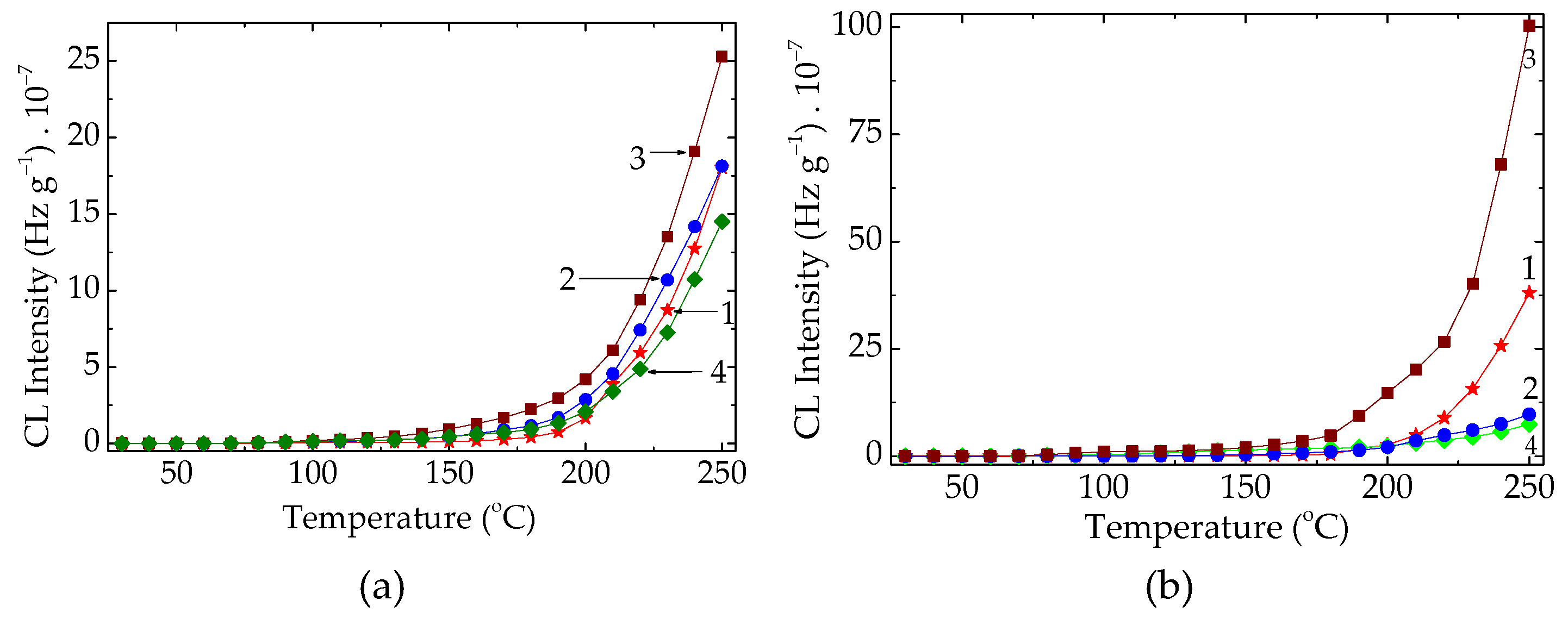

The nonisothermal CL investigation may obviously depict the behavior of inspected materials under various ageing states (

Figure 4). The scission of PLA molecules, which decreases the oxidation strength, starts effectively when the temperature of the material exceeds 100 °C, even though insignificant amounts of free radicals are formed since the low amount of heat is transferred to the sample. However, the measurable accumulation of the degradation products is certainly detected when the process temperature reaches 150 °C. The CL intensities are continuously grown, because the fragmentation of polymer molecules provides the oxidizing intermediates at any time.

The contribution of different additives to the evolution of the oxidation state of PLA specimens depends on the type of this component (

Figure 5). In fact, the relative ability shown by the studied stabilizers would prove the importance of the manufacturing procedure when a certain composition shows a peculiar interrelation between the polymer support and the added compounds. The comparison between the two formulations illustrated in

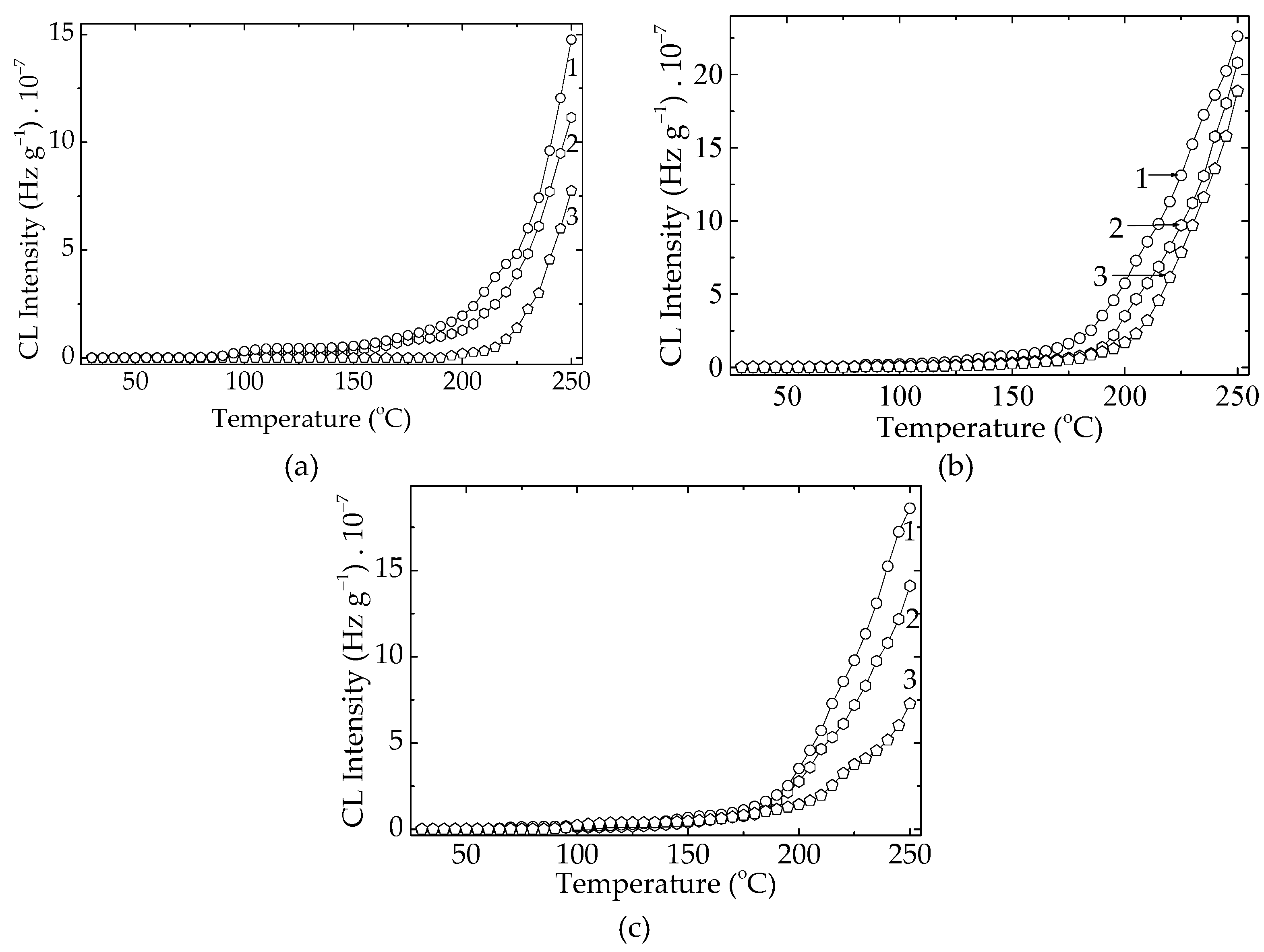

Figure 5 reveals the extension of the stability temperature range for the higher amounts of minor component (3 wt%).

Despite the unexpected behavior of rosemary extract, the other two powders enhance PLA stabilization at higher additive concentrations by shifting the degradation mechanism toward stabilization. At lower antioxidant loadings, an additional benefit is the earlier onset of CL emission, indicating the interaction of the additives with small amounts of hydrocarbon free radicals. When the concentration of herb powders increases to 3 wt%, oxidation behavior is noticeably affected, as evidenced by prolonged oxidation periods (

Figure 6). The antioxidant effect becomes more pronounced under thermal exposure by reducing the fraction of radicals that convert into lactide products, thereby improving the material’s lifespan through a mechanistic shift toward delayed oxidative degradation.

3.3. FTIR Analysis

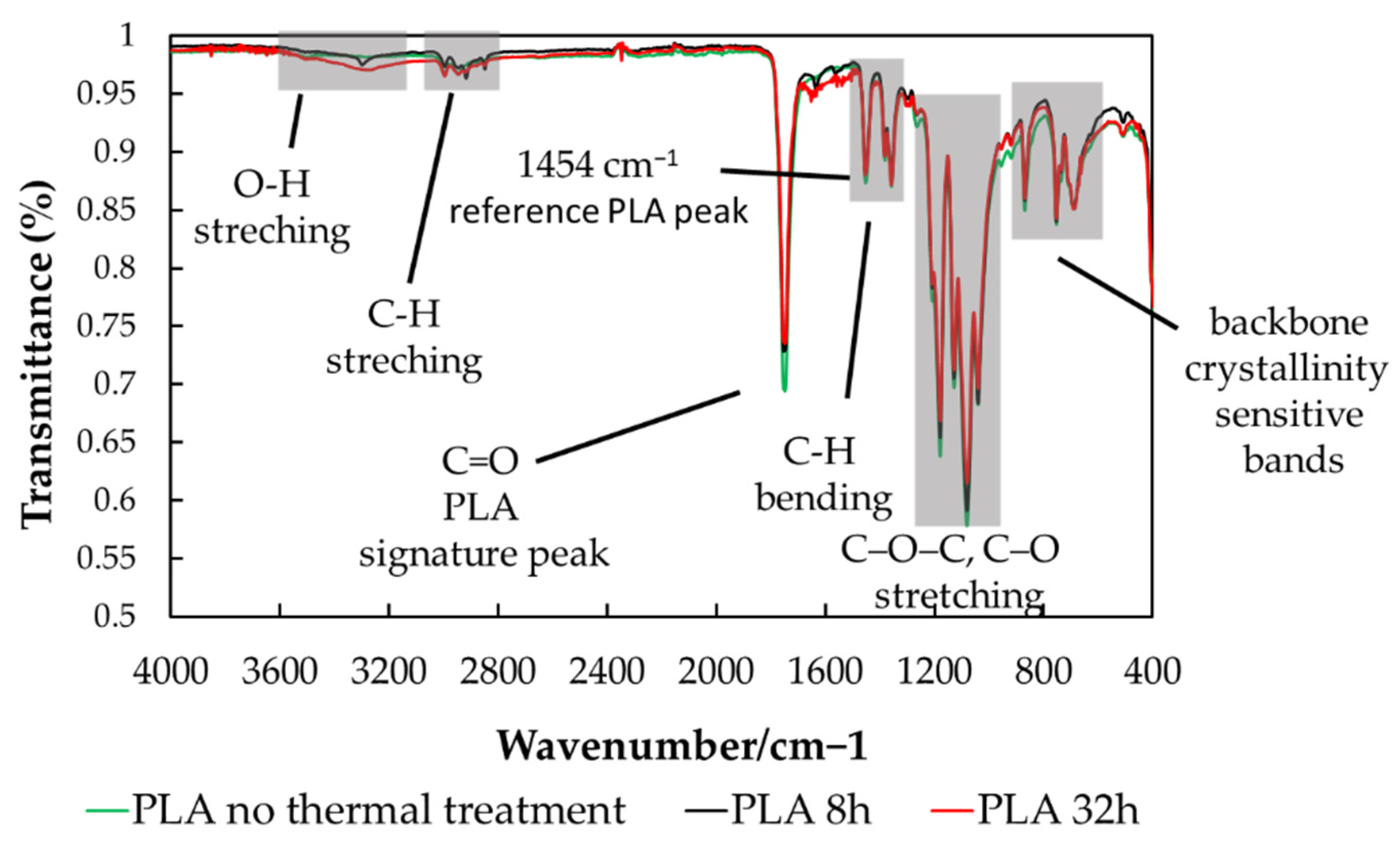

FTIR analysis was made to identify and quantify chemical and structural changes in PLA induced by moderate thermal treatment and by the presence of fillers (natural antioxidant powders), and to relate these changes to the oxidation and stability trends observed by chemiluminescence (CL) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). FTIR is used to track modifications in functional groups that are directly connected to the main degradation pathways of PLA—thermo-oxidation, chain scission, and secondary reactions leading to low-molecular products.

Figure 7 shows the IR spectra of PLA samples subjected to mild thermal treatment for 8 and 32 hours, compared with untreated PLA. Only these spectra are included to emphasize the bands characteristic of the PLA structure clearly and to avoid overcrowding the figure with overlapping spectra that display identical curve shapes. IR analysis of all samples, regardless of filler presence or thermal treatment, reveals no shifts in the characteristic PLA bands. The spectra in

Figure 7 therefore illustrate the typical PLA absorption bands, as summarized in

Table 1.

In PLA the classic FTIR marker for “backbiting”, intramolecular transesterification, and depolymerization that generates lactide cyclic oligomers, is the lactide ring-breathing band in the 930 – 940 cm−¹. When PLA experiences repeated heating-cooling, especially if it spends time molten, is wet, or contains catalysts from fillers, backbiting can increase the amount of cyclic species, and the 930 – 940 cm⁻¹ band tends to grow. No absorption band appears in the 930–940 cm⁻¹ region. ATR-FTIR analysis did not reveal spectral features associated with intramolecular transesterification depolymerization of PLA under the applied mild thermal treatment (80 °C, 8–32 h), either in neat or filled samples. Moreover, the positions of the characteristic PLA bands remain unchanged with thermal treatment and filler addition. These observations indicate that backbiting-type depolymerization, leading to cyclic oligomers or lactide, does not occur to a detectable extent under the studied conditions.

Another IR feature commonly associated with transesterification is the carbonyl stretching region. Although subtle changes in the 1700–1800 cm⁻¹ region can occur as crystallinity and morphology evolve during thermal cycling, no such changes are observed here. The shape and position of the carbonyl absorption band remain unchanged for all samples, regardless of thermal treatment or filler addition, indicating the absence of detectable transesterification-related effects.

The band at 1454 cm⁻¹, assigned to CH₃ asymmetric bending/deformation, is commonly used as an internal reference for PLA and lactide because it is present in both species and is relatively insensitive to morphological changes. Accordingly, this band was used for normalization in the absorbance ratios discussed below.

Figure 8a presents the A3280/A1454 ratio, where the band at ~3280 cm⁻¹ is associated with O–H stretching and can be correlated with the formation of hydroxyl end groups resulting from polymer degradation at sp³ carbon sites. Neat PLA exhibits higher A3280/A1454 values than the filled samples, and this ratio increases with thermal treatment time, reaching a maximum after 16 h at 80 °C. Prolonging the treatment to 32 h does not lead to a further increase, indicating a saturation in newly formed hydroxyl groups. In contrast, all filled samples show consistently lower A3280/A1454 values, suggesting a stabilizing or antioxidant effect of the fillers. No systematic differences are observed among rosemary extract, spirulina biomass, or kelp biomass, and no clear dependence on treatment time is detected. For clarity and to avoid overcrowding,

Figure 8a therefore shows only the representative case of PLA filled with spirulina biomass.

Figure 8b shows the A920/A957 ratio, used as an indicator of the relative crystalline (≈920 cm⁻¹) versus amorphous (≈956–957 cm⁻¹) contribution in PLA. Neat PLA displays the highest A920/A957 values, indicating the largest relative crystalline contribution. Thermal treatment up to 16 h increases this ratio, consistent with annealing-induced chain ordering and crystal perfection above Tg. After 32 h, a slight decrease is observed, which can be attributed to saturation of crystallization and the onset of competing effects such as chain scission, hydrolysis, or structural reorganization. All filled samples exhibit lower A920/A957 values than neat PLA, indicating a reduced relative crystalline contribution and/or an increased amorphous or interfacial constrained fraction. The evolution of this ratio with treatment time is not monotonic in the composites, which is typical of filled systems where competing effects—such as limited nucleation, restricted chain mobility near the filler surface, filler dispersion variability, and the formation of a rigid amorphous fraction—act simultaneously.

Figure 8c presents the A754/A1454 ratio to assess morphology-related changes induced by thermal treatment and filler addition. The band at ~754 cm⁻¹ lies in the fingerprint region of PLA and is associated with skeletal and backbone-related vibrations that are sensitive to chain conformation, packing, and crystallinity, even in the absence of chemical changes. For neat PLA, A754/A1454 increases slightly after thermal treatment up to 16 h, consistent with annealing-induced ordering, and then decreases after 32 h, suggesting the influence of degradation or hydrolytic effects that limit further crystallization. In contrast, all filled samples show lower and nearly constant A754/A1454 values, independent of filler type, loading, or treatment time. Notably, the evolution of A754/A1454 closely follows the trend observed for A920/A957 (

Figure 8b), indicating that both ratios reflect similar morphology-related changes induced by filler incorporation and mild thermal treatment rather than chemical degradation.

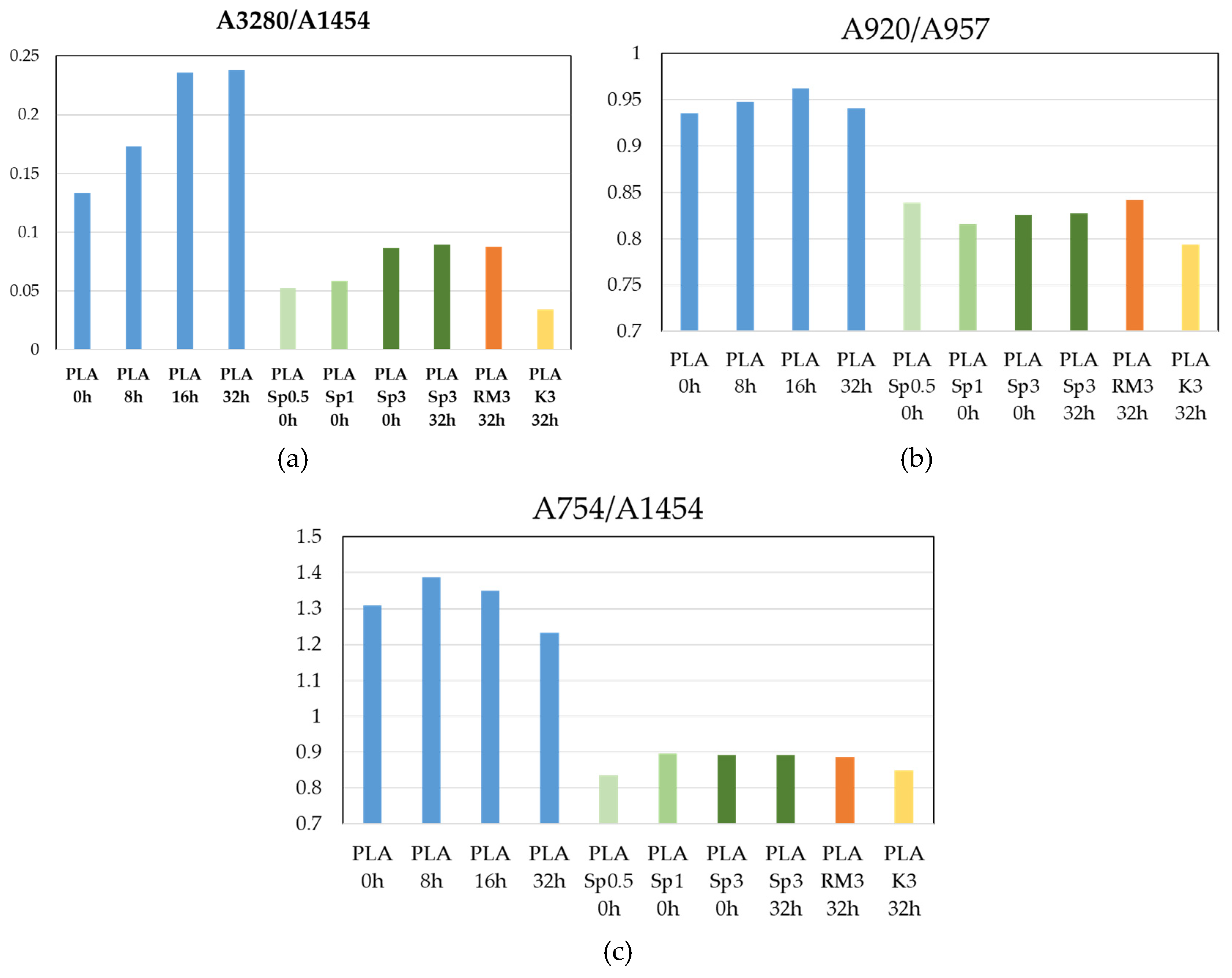

3.4. DSC Analysis

DSC analysis shows that all PLA samples—whether thermally treated or untreated, and whether filled or unfilled—exhibit the same overall thermal behavior. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the DSC thermograms recorded over successive heating–cooling cycles display a common pattern characterized by the glass transition, cold crystallization, melting during heating, and melt crystallization upon cooling. No additional thermal events are detected as a result of thermal treatment or filler incorporation; the observed differences among samples are limited to shifts in peak positions and changes in peak width or intensity within these characteristic regions.

The DSC data presented in

Figure 9 show that the glass transition occurs in the temperature range of approximately 55–75 °C. The position and shape of the glass transition differ between the first heating cycle and the subsequent second and third heating cycles. In addition, cold crystallization and pre-melting events are not observed during the first heating step. This initial heating reflects the complex thermal history of the samples, in which residual crystallinity from processing, disordered chain orientation, and non-uniform dispersion of nucleation sites, particularly in filled samples, contribute to a broad and poorly defined crystallization behavior. As a result, crystallization does not initiate uniformly throughout the material, but instead occurs over a wider temperature interval, leading to peak broadening. After the first heating–cooling cycle, a more homogeneous population of nucleation centers is established. Consequently, during the second and third heating cycles, well-defined cold crystallization and pre-melting peaks become apparent, as shown in

Figure 9.

3.4.1. Glass Transition

DSC measurements were performed on PLA samples in air over the temperature range of 30–250 °C using repeated heating–cooling cycles. For neat (unfilled) PLA (Supplementary Material,

Figure S1a), the onset temperature of the glass transition during the first heating cycle increases progressively with thermal treatment at 80 °C, from ~62 °C for the untreated sample to ~67 °C after 32 h of treatment. At the same time, the heat capacity change at Tg (ΔCp) decreases after 8 h of thermal exposure and remains nearly constant for longer treatment times. The simultaneous increase in Tg,onset and decrease in ΔCp indicate a reduction in the fraction of mobile amorphous chains and the development of a more constrained and uniformly organized amorphous phase induced by mild thermal annealing.

In contrast, during the second and third heating DSC cycles, all neat PLA samples exhibit similar Tg,onset values around ~58 °C, demonstrating that the initial differences originate from the prior thermal history and are removed after the first heating–cooling cycle. The partial recovery of ΔCp observed in the third heating cycle compared with the second suggests some relaxation and redistribution of chain constraints upon repeated thermal cycling. Overall, these results indicate that mild thermal treatment at 80 °C primarily affects the amorphous-phase organization of PLA rather than inducing permanent chemical or structural degradation.

Although the thermal history is erased after the first DSC heating–cooling cycle, thermally treated PLA samples continue to exhibit lower ΔCp values in the second and third heating steps compared with untreated PLA. This indicates that mild annealing at 80 °C induces persistent constraints in the amorphous phase, reducing the fraction of mobile amorphous chains. In contrast, untreated PLA retains a larger mobile amorphous fraction after thermal cycling, resulting in higher ΔCp values. These results suggest that the thermal treatment leads to a more constrained and structurally stabilized amorphous phase rather than reversible thermal-history effects

For the filled PLA samples, the evolution of the glass-transition onset temperature and ΔCp generally follows the same trends observed for neat PLA (

Figure S1b–m). Thermal treatment at 80 °C leads to lower Tg,onset values and higher ΔCp in the subsequent DSC heating cycles, indicating partial relaxation of the initial thermal history.

In PLA filled with kelp biomass (

Figure S1b–e), some deviations are observed. For the untreated composite, ΔCp decreases, while Tg,onset increases from ~65–66 °C in the first heating cycle to ~66–68 °C in the second and third cycles. For samples thermally treated for 8 and 16 h, Tg,onset increases from ~58–60 °C in the first heating to ~64–68 °C in the subsequent heating cycles. In the case of the 32 h–treated samples, ΔCp shows a similar evolution, while Tg,onset depends on kelp content, being lower for samples without kelp or with 1 wt% kelp and higher by approximately 2–4 °C for samples containing 0.5 wt% or 3 wt% kelp.

PLA samples containing rosemary extract (

Figure S1f-i) show trends in Tg,onset and ΔCp similar to those of neat PLA. However, for all thermally treated samples, Tg,onset is consistently higher than in unfilled PLA, independent of treatment time and DSC heating cycle. This behavior can be attributed to the presence of low–molecular weight phenolic compounds in the rosemary extract, which preferentially interact with the amorphous phase of PLA, restricting segmental mobility and leading to a persistent increase in Tg without significantly altering crystallization behavior.

For PLA/spirulina composites thermally treated for 16 and 32 h, Tg,onset increases from the second to the third DSC heating cycle, and the magnitude of this increase scales with spirulina content. This behavior suggests progressive development of a constrained amorphous interphase upon repeated thermal cycling, likely promoted by the polar biomolecular components of spirulina (e.g., proteins,pigments such as phycocyanin) that can enhance PLA–filler interactions.

Overall, these results indicate that filler affects the balance between mobile and constrained amorphous fractions in PLA, leading to filler-content-dependent modifications of the glass-transition behavior, while the general thermal response remains governed by annealing and thermal-history effects.

3.4.2. Cold Crystallization

For the neat PLA samples (

Figure S2a), the cold crystallization behavior shows systematic changes with both DSC cycling and prior thermal treatment. Between the second and third DSC heating steps, an increase in both the cold crystallization onset temperature (Tc,onset) and the cold crystallization enthalpy (ΔHc) is observed, indicating enhanced crystallization ability after repeated thermal cycling. In contrast, increasing the duration of the mild thermal treatment at 80 °C (8, 16, and 32 h) leads to a progressive decrease in both Tc,onset (~89°C) and ΔHc, suggesting that prolonged annealing reduces the amount of crystallizable material, likely due to the development of constrained amorphous regions and/or limited chain degradation that restrict crystal growth.

For PLA samples filled with kelp or spirulina biomass (

Figure S2b–e and

Figure S2j–m), both the untreated and non-pre-annealed samples show an increase in the cold-crystallization onset temperature (Tc,onset) and the cold-crystallization enthalpy (ΔHc) between the second and third DSC heating cycles, indicating enhanced crystallization upon repeated thermal cycling. For thermally treated samples (8, 16, and 32 h at 80 °C), Tc,onset, and ΔHc increase with increasing kelp or spirulina content, suggesting a filler-dependent effect on the crystallization behavior after annealing.

In contrast, PLA samples containing rosemary extract (

Figure S2f–i) exhibit a different trend. Tc,onset increases between the second and third DSC heating cycles for all compositions. For untreated and 8 h thermally treated samples, both Tc,onset, and ΔHc decrease when rosemary extract is added up to 0.5 wt% compared with neat PLA, while higher loadings (above 0.5 wt%, up to 3 wt%) lead to increasing Tc,onset, and ΔHc values. This behavior changes for samples thermally treated for 16 h or longer, indicating that prolonged annealing alters the influence of rosemary extract on cold-crystallization behavior.

3.4.3. Melting

The melting behavior of the neat PLA samples shows a systematic dependence on prior thermal treatment and DSC cycling (

Figure S3a). During the first DSC heating cycle, the melting onset temperature is observed at approximately 170 °C and increases slightly with increasing duration of the mild thermal treatment at 80 °C (8, 16, and 32 h), indicating the formation of more stable or better-organized crystalline domains. At the same time, the melting enthalpy (ΔHm, endothermic) decreases with increasing thermal treatment time, suggesting a reduction in the overall crystalline fraction or the development of less perfect crystals. In the second and third DSC heating cycles, the melting onset temperature is lower, around ~166 °C, reflecting the removal of the prior thermal history after the first heating–cooling cycle. A small increase of approximately 1–2 °C in the melting onset temperature is observed in the third heating cycle, indicating minor reorganization or perfection of crystalline structures upon repeated thermal cycling..

For the filled PLA samples, the overall trend of the melting onset temperature follows that observed for neat PLA (

Figure S3 b-m). In thermally treated PLA containing kelp biomass, the melting onset temperature decreases with increasing treatment duration up to 16 h, suggesting the formation of less stable or more heterogeneous crystalline domains. However, for samples treated for 32 h, the melting onset temperature increases again, indicating partial reorganization or stabilization of crystalline structures upon prolonged thermal exposure.

In thermally treated PLA containing kelp biomass, the melting onset temperature decreases with increasing filler content up to 1 wt%, indicating reduced crystal stability at low filler loadings. However, at higher kelp contents (above 1 wt% and up to 3 wt%), the melting onset temperature increases again, suggesting partial stabilization or reorganization of crystalline domains at higher filler concentrations. PLA samples filled with rosemary extract exhibit an opposite trend in melting onset temperature compared with kelp-filled systems, with the onset temperature increasing at low extract contents and decreasing at higher loadings. In contrast, for thermally treated PLA containing spirulina biomass, the melting onset temperature decreases monotonically with increasing filler content, showing an inverse relationship with spirulina concentration. These distinct behaviors highlight the different roles of the fillers, reflecting differences in their chemical composition and interfacial interactions with the PLA matrix, which influence crystal stability in different ways.

3.4.4. Melt Crystallization

The DSC analysis of unfilled PLA samples (

Figure S4a) show that the melt-crystallization onset temperature remains essentially unchanged with increasing duration of the thermal treatment, but shifts to slightly lower values during the second cooling step compared with the first. In contrast, the melt-crystallization enthalpy (ΔHmc) increases progressively with longer thermal treatment during sample preparation, indicating enhanced crystallization upon cooling as a result of prior thermal conditioning. The decrease in onset temperature between successive cooling steps suggests that, after the first heating–cooling cycle, crystal nucleation occurs more readily, allowing crystallization to start at lower temperatures while producing a larger crystalline fraction.

For PLA samples filled with kelp biomass, the melt-crystallization behavior follows a trend similar to that of neat PLA. In several cases, however, the crystallization peak observed during the second cooling step becomes significantly broadened, leading to reduced ΔHmc values; in some samples, the crystallization peak is no longer detectable in the second cooling cycle. This behavior suggests a reduced crystallization efficiency and increased heterogeneity in crystal formation after repeated thermal cycling.

In contrast, PLA samples containing rosemary extract show a systematic decrease in both the melt-crystallization onset temperature and ΔHmc with increasing extract content. This trend was consistently observed during both the first and second cooling steps and becomes more pronounced for samples thermally treated for 16 and 32 h. A similar pattern is also observed for PLA samples filled with spirulina biomass, particularly after longer thermal treatments (16 and 32 h). These results indicate that rosemary extract and spirulina biomass increasingly hinder melt crystallization at higher loadings, likely due to enhanced interfacial constraints and reduced chain mobility during cooling.

4. Discussion

The service lifetime of polymeric materials depends not only on their structural and compositional characteristics but also on environmental conditions that supply energy and initiate oxidative degradation processes [

36]. Antioxidants play a key role in extending material durability by interrupting oxidation chain reactions, thereby broadening both the service life and application range of polymer products [

37]. In the case of PLA, degradation proceeds primarily through random chain scission, leading to molecular fragmentation [

5,

39]. This process, which occurs mainly in the crystalline regions, results in degradation products formed via depolymerization and oxidative pathways [

39]. CL analysis provides direct insight into the oxidative degradation of polymers by monitoring photon emission during thermal exposure. Non-isothermal CL measurements indicate that significant oxidative decomposition of PLA begins at temperatures above approximately 50 °C, as evidenced in

Figure 6 and

Figure 10.

The chemiluminescence results demonstrate that oxidative degradation of PLA can be effectively delayed by the addition of low amounts of natural stabilizers, as shown in

Figure 11. The inhibition of oxidation is initiated by the scavenging of free radicals through hydrogen donation from phenolic groups, a mechanism that competes with radical reactions involving diffused oxygen [

40]. Consequently, the stabilizing efficiency depends on the strength and availability of labile protons in the polyphenolic compounds present in the studied powders. Consistent trends obtained from both isothermal and non-isothermal CL measurements allow the following ranking of antioxidant efficiency for the thermal protection of PLA:

Ascophyllum nodosum (K) < Arthrospira platensis (SP) < Rosmarinus officinalis (RM).

Previous studies have shown that thermal degradation of PLA involves the simultaneous occurrence of oxidative degradation and depolymerization, leading to different classes of degradation products [

28,

41]. While antioxidants primarily interfere with oxidation pathways, they cannot fully suppress all radical processes associated with chain scission, which explains why complete stabilization is not achieved, in contrast to highly unsaturated elastomeric systems such as styrene–isoprene–styrene (SIS) [

42,

43]. This interpretation is consistent with the FTIR and DSC results, which indicate that the fillers and extracts mainly influence chain mobility, morphology, and interfacial constraints rather than inducing or preventing chemical degradation. In particular, the absence of new IR bands, the stability of characteristic PLA absorptions, and the morphology-driven changes in FTIR band ratios (A920/A957 and A754/A1454), together with DSC-observed shifts in Tg, crystallization, and melting behavior, confirm that the dominant effects of the additives are physical rather than chemical.

The CL-derived oxidation induction times (OITs) further support this conclusion, revealing distinct stabilization efficiencies among the three additives. PLA samples containing rosemary extract exhibit the longest OITs, whereas kelp-modified samples show the shortest, indicating different capacities to delay the onset of oxidation. These differences correlate with the DSC and FTIR observations, where rosemary extract consistently increases Tg and suppresses oxidation-related hydroxyl formation, while biomass fillers introduce heterogeneous interfacial regions that affect crystallization and chain constraints. The increase in stability with increasing additive concentration up to 3 wt% (

Figure 11) confirms the effective implementation of these protection mechanisms within the studied loading range.

Taken together, the combined IR, DSC, and CL analyses demonstrate that the selected natural additives improve the thermal stability of PLA primarily by slowing oxidation kinetics and modifying amorphous-phase mobility and morphology, rather than by preventing depolymerization entirely. The role of the stabilizers is therefore best described as mitigating the inherent thermal instability of PLA under moderate and severe operating conditions, with their effectiveness governed by both antioxidant chemistry and interfacial interactions within the polymer matrix [

45].

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comparative and application-oriented assessment of the thermal and oxidative stability of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) under moderate, repetitive thermal exposure representative of food-use and pre-recycling conditions. By combining repeated thermal treatment at 80 °C with DSC, FTIR, and chemiluminescence analyses, the work offers a realistic evaluation of how food-grade additives—rosemary extract, spirulina biomass, and kelp biomass—affect PLA behavior at low loadings (0.5–3 wt%).

FTIR analysis demonstrated that neither repeated thermal exposure nor filler addition induced detectable chemical degradation of the PLA matrix, as evidenced by the stability of characteristic absorption bands and the absence of signatures associated with depolymerization or backbiting reactions. The observed variations in FTIR band ratios (A920/A957 and A754/A1454) indicate that the primary effects of thermal treatment and filler incorporation are related to morphology and chain organization, including changes in crystallinity and constrained amorphous regions, rather than chemical modification.

DSC results further confirmed that repeated mild heating influences the thermal history and morphology of PLA without fundamentally altering its thermal behavior. Neat PLA exhibited annealing-driven changes in glass transition, crystallization, and melting behavior, while filled systems showed filler-dependent modifications linked to interfacial interactions and amorphous-phase constraints. Rosemary extract consistently increased the glass-transition temperature, reflecting restricted chain mobility, whereas algal biomasses introduced heterogeneous interfacial effects that influenced crystallization kinetics, melt crystallization, and crystal stability. These trends are particularly relevant for food-contact materials subjected to multiple heating and cooling cycles during use and recycling.

Chemiluminescence measurements provided direct evidence of oxidative stabilization, revealing that all additives delayed the onset of oxidation to some extent. The antioxidant efficiency followed the order:

Ascophyllum nodosum (kelp) < Arthrospira platensis (spirulina) < Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary).

Importantly, the CL results complement the DSC and FTIR findings by demonstrating that stabilization arises from a combination of antioxidant activity and morphology-driven effects, rather than complete suppression of degradation mechanisms.

Overall, this work demonstrates that algae-based biomasses can act as multifunctional fillers in PLA, simultaneously influencing morphology, thermal response, and oxidation kinetics under realistic service-life conditions. While rosemary extract remains the most effective antioxidant, spirulina and kelp biomasses provide measurable stabilization while maintaining compatibility with food-contact requirements. The novelty of this study lies in its focus on moderate, repetitive thermal exposure relevant to real food-use and recycling scenarios, rather than extreme degradation conditions. These findings support the potential use of algae-derived fillers as sustainable, food-grade additives for extending the functional lifetime and recyclability of PLA-based materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and M.B.; methodology, T.Z., M.B.; software, T.Z., M.B., C.M.N.; validation, T.Z., M.B., A.C.; formal analysis, T.Z., M.B., C.M.N.; investigation, T.Z., M.B., C.M.N., A.C., R.M.; resources, C.M.N.; data curation, T.Z., M.B., A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors.; writing—review and editing, T.Z., M.B., C.M.N.; supervision, T.Z., C.M.N.; project administration, T.Z., C.M.N.; funding acquisition, C.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by Ministry of Education and Research – UEFISCDI, project PN-IV-P7.1-PTE-2024-0653 – contract no: 38PTE⁄2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AO |

antioxidant |

| CL |

chemiluminescence |

| Cp |

heat capacity |

| DSC |

Differential scanning calorimetry |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| Hc |

cold crystallization enthalpy |

| Hm |

melting enthalpy |

| Hmc |

melt crystallization enthalpy |

| K |

kelp (Ascophyllum nodosum)

|

| OIT |

oxidation induction time |

| OOT |

onset oxidation temperature |

| PLA |

poly(lactic) acid |

| RM |

rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) |

| SIS |

styrene–isoprene–styrene |

| SP |

spirulina (Arthrosipra platensis) |

| Tg |

glass transition temperature |

| Tc |

Crystallization temperature |

| vox

|

oxidation rate |

References

- Marano, S.; Laudadio, E.; Minnelli, C.; Stipa, P. Tailoring the barrier properties of PLA: A state-of-the-art review for food packaging applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikiaris, N.D.; Koumentakou, I.; Samiotaki, C.; Meimaroglou, D.; Varytimidou, D.; Karatza, A.; Papageorgiou, G.Z. Recent advances in the investigation of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nanocomposites: Incorporation of various nanofillers and their properties and applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvam, T.; Rahman, N.M.M.A.; Olivito, F.; Ilham, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Agricultural waste-derived biopolymers for sustainable food packaging: Challenges and future prospects. Polymers 2025, 17, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, C.M.; Bumbac, M.; Buruleanu, C.L.; Popescu, E.C.; Stanescu, S.G.; Georgescu, A.A.; Toma, S.M. Biopolymers produced by lactic acid bacteria: Characterization and food application. Polymers 2023, 15, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharescu, T.; Bumbac, M.; Nicolescu, C.M.; Blanco, I. The contribution of silica nanoparticles to the stability of styrene–isoprene–styrene triblock copolymer (SIS). II. Energetic peculiarities. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 215, 111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Râpă, M.; Stefan, L.M.; Zaharescu, T.; Seciu, A.M.; Țurcanu, A.A.; Matei, E.; Predescu, C. Development of bionanocomposites based on PLA, collagen and AgNPs and characterization of their stability and in vitro biocompatibility. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, S.D.; Androutsopoulou, C.; Hahalis, P.; Kotsalou, C.; Vantarakis, A.; Lamari, F.N. Rosemary extract and essential oil as drink ingredients: Chemical composition, genotoxicity, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antioxidant properties. Foods 2021, 10, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metekia, W.A.; Ulusoy, B.H.; Habte-Tsion, H.M. Spirulina phenolic compounds: Natural food additives with antimicrobial properties. Int. Food Res. J. 2021, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.M.; Assis, M.; de Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina application in food packaging: Gaps of knowledge and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pascual, N.; Montero, M.P.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C. Antioxidant film development from unrefined extracts of brown seaweeds Laminaria digitata and Ascophyllum nodosum. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 37, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raadt, P.D.; Wirtz, S.; Vos, E.; Verhagen, H. Short review of extracts of rosemary as a food additive. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2015, 5, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharescu, T.; Mateescu, C. Investigation on some algal extracts as appropriate stabilizers for radiation-processed polymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumbac, M.; Nicolescu, C.M.; Olteanu, R.L.; Gherghinoiu, S.C.; Bumbac, C.; Tiron, O.; Buiu, O. Preparation and characterization of microalgae styrene–butadiene composites using Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis biomass. Polymers 2023, 15, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.L.; Iyer, H.; McDonald, R.; Hsu, J.; Jimenez, A.M.; Roumeli, E. Spirulina-based composites for 3D printing. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 2878–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbac, M.; Nicolescu, C.M.; Zaharescu, T.; Gurgu, I.V.; Bumbac, C.; Manea, E.E.; Dumitrescu, C. Biodegradation study of styrene–butadiene composites with incorporated Arthrospira platensis biomass. Polymers 2024, 16, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patarra, R.F.; Paiva, L.; Neto, A.I.; Lima, E.; Baptista, J. Nutritional value of selected macroalgae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biris-Dorhoi, E.S.; Michiu, D.; Pop, C.R.; Rotar, A.M.; Tofana, M.; Pop, O.L.; Farcas, A.C. Macroalgae—A sustainable source of chemical compounds with biological activities. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darie-Niţă, R.N.; Vasile, C.; Stoleru, E.; Pamfil, D.; Zaharescu, T.; Tarţău, L.; Leluk, K. Evaluation of the rosemary extract effect on the properties of polylactic acid-based materials. Materials 2018, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulota, M.; Budtova, T. PLA/algae composites: Morphology and mechanical properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 73, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matisová-Rychlá, L.; Rychlý, J.; Slovák, K. Effect of the polymer type and experimental parameters on chemiluminescence curves of selected materials. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2003, 82, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharescu, T.; Râpă, M.; Marinescu, V. Chemiluminescence kinetic analysis on the oxidative degradation of poly(lactic acid). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 128, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Mo, F.; Liang, L.; Chen, T.; Dong, S.; Deng, C.; Wu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, X. Biodegradable polylactic acid (PLA) copolymer materials: Structural design, synthesis strategy, structure–performance relationship, and industrial application. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Elahee, G.M.F.; Fang, Y.; Yu, X.B.; Advincula, R.C.; Cao, C.C. Polylactic acid (PLA)-based multifunctional and biodegradable nanocomposites and their applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 306, 112842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadri, A.A.; Martín-Alfonso, J.E. Thermal, thermo-oxidative and thermomechanical degradation of PLA: A comparative study based on rheological, chemical and thermal properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 150, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopinke, F.-D.; Remmler, M.; Mackenzie, K.; Möder, M.; Wachsen, O. Thermal decomposition of biodegradable polyesters—II. Poly(lactic acid). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1996, 53, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.-T.; Auras, R.; Rubino, M. Processing technologies for poly(lactic acid). Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 820–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasal, R.M.; Janorkar, A.V.; Hirt, D.E. Poly(lactic acid) modifications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallstein, J.; Metzsch-Zilligen, E.; Pfaendner, R. Long-term thermal stabilization of poly(lactic acid). Materials 2024, 17, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Wang, S.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Depolymerization and re/upcycling of biodegradable PLA plastics. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13506–13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, K.; McKeown, P.; Jones, M.D. A circular economy approach to plastic waste. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 165, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; He, J.; Yu, P.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L. Recent progress in rubber antioxidants: A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 207, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kister, G.; Cassanas, G.; Vert, M. Effects of morphology, conformation and configuration on the IR and Raman spectra of various poly(lactic acid)s. Polymer 1998, 39, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aou, K. Effect of Molecular Structure on the Thermal Stability of Amorphous and Semicrystalline Poly(lactic acid); University of Massachusetts Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meaurio, E.; Zuza, E.; López-Rodríguez, N.; Sarasua, J.R. Conformational behavior of poly(L-lactide) studied by infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5790–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, P.; Mehta, R.; Berek, D.; Upadhyay, S.N. Microwave-assisted synthesis of poly(lactic acid) and its characterization using size exclusion chromatography. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2012, 49, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation rates of plastics in the environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, I. Antioxidants: A comprehensive review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, B.; Basko, M.; Bednarek, M.; Socka, M.; Kopka, B.; Łapienis, G.; Biela, T.; Kubisa, P.; Brzeziński, M. Influence of functional end groups on the properties of polylactide-based materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 130, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Aguirre, E.; Iñiguez-Franco, F.; Samsudin, H.; Fang, X.; Auras, R. Poly(lactic acid): Mass production, processing, industrial applications, and end of life. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 333–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospíšil, J.; Nešpůrek, S. Chain-breaking stabilizers in polymers: The current status. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1996, 19, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M.E.C.; Stares, S.L.; Barra, G.M.O.; Hotza, D. Effects of accelerated weathering on properties of 3D-printed PLA scaffolds. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopinke, F.-D.; Mackenzie, K. Mechanistic aspects of the thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) and poly(β-hydroxybutyric acid). J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1997, 40–41–43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, S.; Romero, F.; Suarez, L.; Tcharkhtchi, A.; Ortega, Z. A preliminary study on the use of microalgae biomass as a polyolefin stabilizer. Iranian Polymer Journal 2025, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Yi, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, W. Thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) measured by thermogravimetry coupled with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 97, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Santos, E.; Araújo, A.; Fechine, G.J.M.; Machado, A.V.; Botelho, G. The role of shear and stabilizer on PLA degradation. Polym. Test. 2016, 51, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The isothermal CL spectra recorded on the PLA-based samples (heating temperature: 170 °C). Composition: (1) neat PLA; (2) PLA/K; (3) PLA/SP; (4) PLA/RM (additive loading: 1 wt%).

Figure 1.

The isothermal CL spectra recorded on the PLA-based samples (heating temperature: 170 °C). Composition: (1) neat PLA; (2) PLA/K; (3) PLA/SP; (4) PLA/RM (additive loading: 1 wt%).

Figure 2.

Figure 2. The isothermal CL spectra recorded on the PLA samples modified with natural antioxidants (preheating time: 4 cycles of 8 h each. Heating temperature: 170 °C). Composition: (1) PLA/K; (2) PLA/SP; (3) PLA/RM (additive loading: 0.5 wt%).

Figure 2.

Figure 2. The isothermal CL spectra recorded on the PLA samples modified with natural antioxidants (preheating time: 4 cycles of 8 h each. Heating temperature: 170 °C). Composition: (1) PLA/K; (2) PLA/SP; (3) PLA/RM (additive loading: 0.5 wt%).

Figure 3.

The isothermal CL spectra recorded on unaged PLA stabilized with natural antioxidants (testing temperature: 170 °C). Additive: (a) K; (b) SP; (c) RM (concentrations: (1) 0.5 wt%; (2) 1 wt%; (3) 3 wt%).

Figure 3.

The isothermal CL spectra recorded on unaged PLA stabilized with natural antioxidants (testing temperature: 170 °C). Additive: (a) K; (b) SP; (c) RM (concentrations: (1) 0.5 wt%; (2) 1 wt%; (3) 3 wt%).

Figure 4.

The nonisothermal CL spectra obtained on the neat PLA aged at 80 °C for different heating periods (heating rate: 5 °C min−1) (heating time: (1) non; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (3) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 4.

The nonisothermal CL spectra obtained on the neat PLA aged at 80 °C for different heating periods (heating rate: 5 °C min−1) (heating time: (1) non; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (3) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 5.

The nonisothermal CL spectra were recorded on the PLA modified with three natural antioxidants after their aging for three cycles of 8 h (heating rate: 10 °C min−1). AO concentration: (a) 0.5 wt%; (b) 3 wt%. PLA modification state: (1) non; (2) K; (3) RM, (4) SP.

Figure 5.

The nonisothermal CL spectra were recorded on the PLA modified with three natural antioxidants after their aging for three cycles of 8 h (heating rate: 10 °C min−1). AO concentration: (a) 0.5 wt%; (b) 3 wt%. PLA modification state: (1) non; (2) K; (3) RM, (4) SP.

Figure 6.

The nonisothermal CL spectra of PLA/stabilizers (0.5 wt%) aged at various times (heating rate: 20 °C min-1). Added compounds: (a) RM, (b) SP, (c). Heating intervals: (1) none; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (4) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 6.

The nonisothermal CL spectra of PLA/stabilizers (0.5 wt%) aged at various times (heating rate: 20 °C min-1). Added compounds: (a) RM, (b) SP, (c). Heating intervals: (1) none; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (4) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of PLA: no thermal treatment (green line), 8 hours, and 32 hours thermal treatment.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of PLA: no thermal treatment (green line), 8 hours, and 32 hours thermal treatment.

Figure 8.

Values of ratios of: (a) absorbance measured at 3280 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 1454 cm−1 , (b) absorbance measured at 920 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 957 cm−1, and (c) absorbance measured at 754 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 1454 cm−1.

Figure 8.

Values of ratios of: (a) absorbance measured at 3280 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 1454 cm−1 , (b) absorbance measured at 920 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 957 cm−1, and (c) absorbance measured at 754 cm−1 relative to the absorbance measured at reference wavelength 1454 cm−1.

Figure 9.

DSC curve pattern of the tested PLA samples.

Figure 9.

DSC curve pattern of the tested PLA samples.

Figure 10.

The nonisothermal CL spectra ascribed to neat PLA degraded at various times (heating rate: 15 °C min-1). Heating period: (1) non; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (4) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 10.

The nonisothermal CL spectra ascribed to neat PLA degraded at various times (heating rate: 15 °C min-1). Heating period: (1) non; (2) one cycle of 8 h; (3) two cycles of 8 h; (4) four cycles of 8 h.

Figure 11.

The nonisothermal CL spectra recorded on the modified PLA samples (Heating rate: 5 °C min-1). Additive: (a) RM; (b) SP; (c) K. Additive loading: (a) 0.5 %; (b) 1 wt %; (c) 3 wt %.

Figure 11.

The nonisothermal CL spectra recorded on the modified PLA samples (Heating rate: 5 °C min-1). Additive: (a) RM; (b) SP; (c) K. Additive loading: (a) 0.5 %; (b) 1 wt %; (c) 3 wt %.

Table 1.

IR main absorption bands of PLA tested samples [

32,

33,

34].

Table 1.

IR main absorption bands of PLA tested samples [

32,

33,

34].

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) |

Assignment |

| 3500–3200 |

weak/broad O–H stretching - terminal –OH, moisture), possible oxidation intermediates |

| 2995–2945 |

–CH₃ asymmetric stretching |

| 2945–2880 |

–CH₃ symmetric stretching |

| 1749 |

very strong C=O stretching of ester group (signature peak of PLA) |

| 1454 |

CH₃ asymmetric bending – reference peak |

| 1385–1360 |

CH₃ symmetric bending |

| 1265 |

C–O–C stretching (ester) |

| 1210, 1180 |

C–O stretching |

| 1130, 1080 |

C–O–C asymmetric stretching |

| 1042 |

C–O stretching of the backbone |

| 957 |

C–O–C stretching and skeletal vibrations of the polymer backbone associated with the amorphous phase of PLA |

| 920 |

C–COO stretching vibrations associated with the crystalline phase of PLA |

| 870 |

C–COO stretching / CH₃ rocking |

| 754 |

PLA skeletal vibrations |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).