1. Introduction

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, commonly known as Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (CuTS), is a frequent compressive mononeuropathy often resulting in pain, paresthesia (numbness or tingling) in the ring and pinky fingers, and muscle weakness in the hand. The condition arises from increased pressure on the ulnar nerve as it passes superficially through the cubital tunnel at the medial aspect of the elbow.

Cubital tunnel syndrome may present with numbness, tingling, or pain involving the ring and small fingers, as well as the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand. Symptoms are frequently exacerbated at night or during specific joint positions and movements, particularly with elbow flexion. These manifestations can significantly impair quality of life and range in severity from mild weakness to marked loss of fine motor control [

1]. Ulnar nerve–related pain may result from compression at multiple potential sites, including the cervical nerve roots as they exit the spinal cord, the brachial plexus, the thoracic outlet, or more distally along the upper extremity within the arm, elbow, forearm, or wrist [

2].

The clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome primarily involves the execution of provocative maneuvers at the elbow or wrist to reproduce symptoms along the distribution of the ulnar nerve. These maneuvers include Tinel’s sign, the elbow flexion–compression test, and palpation of the ulnar nerve to assess for thickening or localized tenderness. The scratch collapse test is an additional provocative maneuver in which the examiner lightly scratches the patient’s skin over the suspected site of nerve entrapment, followed by a resisted shoulder external rotation. A positive response is characterized by a transient collapse of the arm into internal rotation against resistance [

3]. However, despite its interrater reliability, the test demonstrates limited sensitivity and thus cannot be considered a dependable diagnostic tool for excluding CuTS. Its specificity, nonetheless, is reported to be higher than that of other clinical tests such as Tinel’s sign and the flexion–compression test but it lacks sufficient reliability for the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies [

4]. Sonographic evaluation has also been investigated as a diagnostic adjunct for CuTS thanks to its high sensitivity for detecting ulnar neuropathies at the elbow. An increased cross-sectional area of the ulnar nerve at specific locations around the elbow is indicative of a positive finding. Therefore, ultrasound can serve as a valuable complementary modality for the rapid assessment and follow-up of patients with CuTS. In conclusion, no single clinical examination has achieved universal acceptance for the diagnosis of CuTS. This limitation arises from the variable diagnostic accuracy of existing tests, interrater variability, and the occurrence of positive findings in asymptomatic individuals [

5]. Accordingly, the diagnosis of CuTS should rely on a combination of clinical suspicion, physical examination, and confirmatory diagnostic testing.

The management of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome includes both nonoperative and operative approaches. Conservative treatment is typically indicated for mild to moderate cases, whereas surgical intervention is generally reserved for patients presenting with severe or refractory symptoms. A meticulous history taking is essential for identifying specific activities or movements that exacerbate symptoms and to guide individualized management. Nonoperative strategies may include the use of elbow splints or braces designed to limit motion within a range of approximately 30°–45° of flexion. These orthotic devices aim to reduce mechanical irritation of the ulnar nerve by minimizing repetitive movements and prolonged elbow flexion. However, current evidence regarding the clinical efficacy of splinting remains inconclusive. Surgical treatment is indicated in patients who fail to respond to conservative management or who exhibit significant neurological deficits. The two principal surgical techniques are in situ decompression and anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. Both procedures seek to relieve the ulnar nerve from compression and tension within the cubital tunnel, thereby restoring nerve function and alleviating symptoms. [

6]

While classic etiologies include prolonged or repetitive elbow flexion, direct trauma, and anatomical anomalies, the dramatic rise in smartphone usage has introduced new potential risk factors. Prolonged smartphone use for activities like gaming, scrolling, or texting, can lead to various musculoskeletal disorders, including what has been colloquially termed "Text Claw" or "Cell Phone Elbow." These non-medical terms describe symptoms such as cramping, aching, and pain in the upper extremities, including the neck, shoulders, arms, and hands, that stem from sustained, often static, and repetitive motions which can cause musculoskeletal disorders [

7,

8,

9]. Cell phone elbow/prolonged-phone-posture (PPP) occur due to bending or flexed posture of the elbow for long period of time, while using the phone for audio call [

10]. Recent clinical observations suggest a strong correlation between the extensive duration of cell phone use and increased pressure on the ulnar nerve [

11,

12,

13]. Specifically, maintaining a flexed elbow posture, often near the ear for calls or held in front of the body for prolonged interaction, significantly increases mechanical tension and compression within the cubital tunnel, potentially leading to nerve compromise [

14]. Despite the growing prevalence of smartphone-related upper extremity complaints, including symptoms mirroring Cubital Tunnel Syndrome, research specifically investigating this relationship remains limited compared to studies on computer-related disorders [

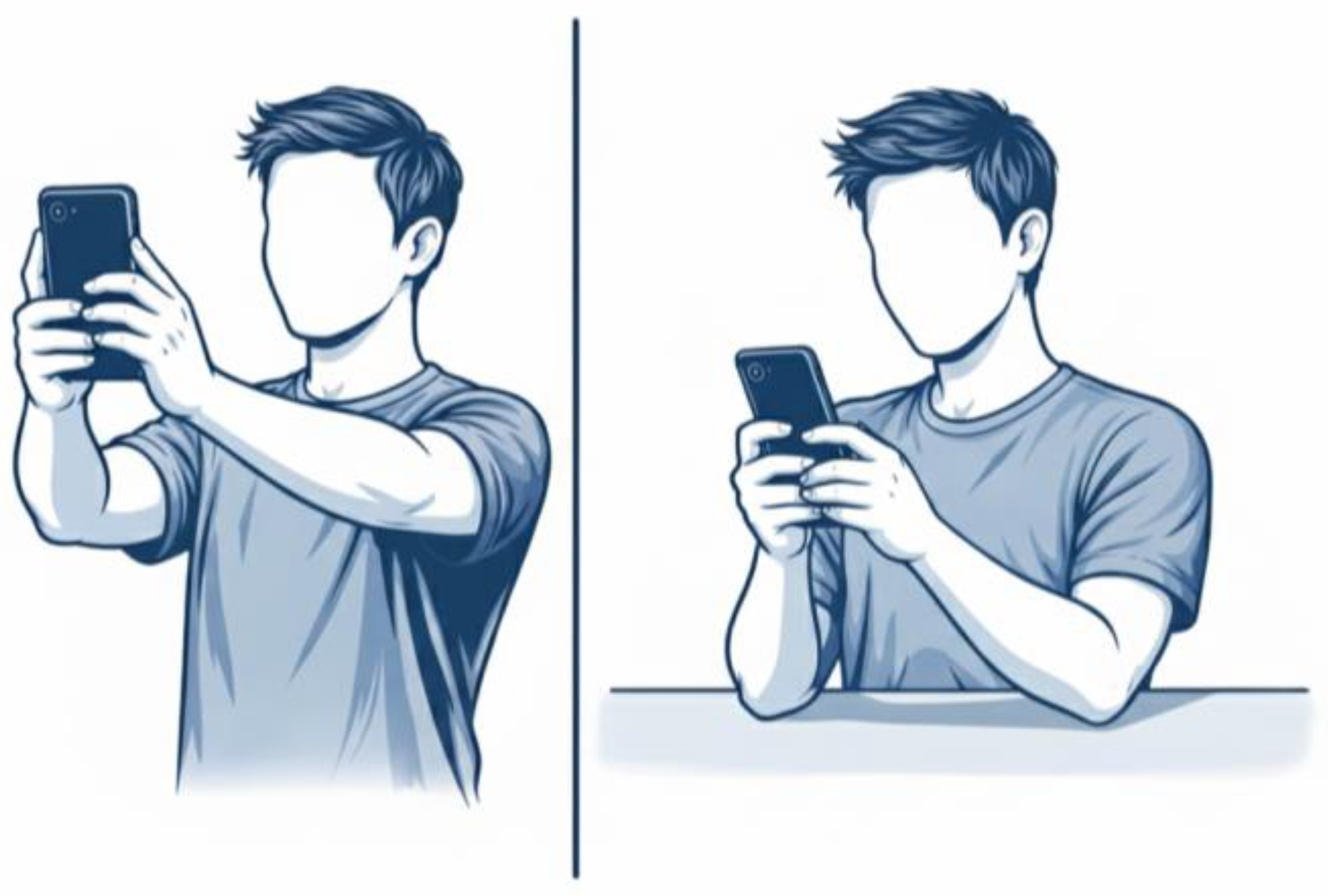

15]. The aim of this retrospective study is to investigate the significant correlation between smartphone use and the development of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Specifically, the study evaluates whether variables such as daily usage duration (in hours), body and hand posture during device use (as shown in

Figure 1) and primary type of activity performed on the smartphone are significantly correlated with the onset of this neuropathy when compared with a control group of unaffected individuals. By integrating clinical data with self-reported patterns of smartphone use, this research seeks to clarify whether modern mobile technology habits may represent an additional risk factor for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow.

2. Materials and Methods

The investigation was performed in full accordance with the ethical guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Orthopedic and Hand Surgery Unit of the “Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS (Rome, Italy)” between January 2021 and December 2024. The primary objective was to evaluate the correlation between smartphone use and the onset of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, or Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (CuTS). The study design and reporting followed the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.

2.2. Population

A total of 100 subjects were included and divided equally into two groups: Group A (CuTS group): 50 patients diagnosed with Cubital Tunnel Syndrome, confirmed by electromyographic (EMG) testing, who subsequently underwent surgical decompression. Group B (Control group): 50 randomly selected subjects without any clinical or electromyographic evidence of ulnar nerve compression. Controls were chosen to be broadly comparable to the CuTS group in terms of age distribution and general demographic profile.

Inclusion criteria were: age over 18 years, right- or left-hand dominance clearly defined, and regular smartphone use for at least one year.

Exclusion criteria included: previous elbow surgery or trauma, other local musculoskeletal or neurological disorders, ulnar nerve subluxation or dislocation, systemic neuropathic conditions (e.g., diabetes), and lack of smartphone use.

2.3. Data Collection

Clinical records were manually and independently reviewed by three authors to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the collected data. Demographic and clinical information was retrieved from hospital records and supplemented with patient questionnaires. The following variables were recorded for each participant:

Age, sex, and body mass index (BMI)

Smoking and occupational status

Dominant limb

Daily duration of smartphone use (hours/day)

Type of predominant activity (calls, social media, texting, gaming)

Usual posture during smartphone use (elbow flexed near ear, forearm resting on surface, alternating hands)

he questionnaire included both quantitative and qualitative items aimed at assessing smartphone-related ergonomic behaviors and potential risk factors. In Group A, electromyographic (EMG) findings were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis. The mean duration of daily smartphone use was self-reported and expressed as the average number of hours per day.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as frequencies or percentages.

Comparisons between groups were performed using the unpaired Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables.

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The study included a total of 100 subjects, divided equally between patients with electromyography-confirmed Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (Group A) and randomly selected controls without clinical or EMG evidence of ulnar nerve compression (Group B). The mean age was 58.7 ± 12.4 years in the CuTS group and 54.9 ± 13.2 years in the control group.

The two cohorts were demographically comparable, with no significant differences in sex distribution, BMI, smoking status, employment, or other baseline characteristics (p > 0.05). These findings indicate that the control population was well-matched to the case group, minimizing confounding related to demographic variability.

A detailed summary of demographic characteristics is reported in

Table 1.

3.2. Smartphone Use Patterns

Mean daily smartphone use was higher in the CuTS group (4.94 ± 1.8 hours/day) compared with the control group (4.04 ± 1.5 hours/day). Although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0716), it indicates a trend toward increased overall smartphone use among patients with CuTS.

More pronounced differences emerged in posture-related variables. A flexed-elbow posture, biomechanically unfavorable and known to increase strain on the ulnar nerve, was substantially more frequent in the CuTS group (82% in the “in the hand, elbow flexed” category) compared with controls (56%). Conversely, the use of a supporting surface during smartphone interaction was significantly less common in CuTS patients (16% vs. 38%). When analyzed collectively, posture distributions demonstrated a statistically significant association with CuTS diagnosis (p = 0.019), supporting the relevance of ergonomically disadvantageous positions in ulnar nerve compression.

In contrast, smartphone activity patterns did not differ significantly between groups. The distribution of video viewing, typing, and calling activities was similar between CuTS patients and controls, as confirmed by the non-significant global comparison (p = 0.858). These findings suggest that the type of activity performed is less influential than the posture adopted during smartphone use.

A comprehensive summary of smartphone-related variables including usage duration, handling posture, and activity type is provided in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the potential correlation between smartphone use and compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (Cubital Tunnel Syndrome, CuTS). Although CuTS is traditionally associated with prolonged elbow flexion, direct trauma, anatomical narrowing, or systemic neuropathies, the widespread adoption of smartphones in the past decade has introduced a new class of sustained postures and repetitive behaviors that may represent underrecognized risk factors. The results of our retrospective analysis indicate that while total smartphone time may play a contributory role, posture during device use appears to exert a significantly stronger influence on the development of ulnar nerve compression.

4.1. Interpretation of Main Findings

Our data revealed a trend toward higher daily smartphone use among patients with CuTS (4.94 h/day) compared with controls (4.04 h/day), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0716). While this suggests that duration of smartphone use alone may not be sufficient to precipitate ulnar nerve compression, the observed trend is clinically noteworthy, as greater exposure time inevitably increases the cumulative duration spent in potentially harmful upper-limb postures. Nevertheless, the most relevant difference between the two groups emerged from the posture-related variables, which demonstrated a clear and statistically significant association with CuTS. Specifically, 82% of CuTS patients reported using the smartphone with the elbow flexed, compared with 56% of controls, and supportive postures were significantly less common among affected individuals (16% vs. 38%). Such findings strongly indicate that ergonomic positioning, and particularly prolonged elbow flexion, plays a pivotal etiological role in the development of CuTS, outweighing the influence of overall daily exposure time.

The biomechanical rationale underlying this association is robust and well described in the literature. Elbow flexion is known to increase intraneural pressure, longitudinal traction, and deformation of the ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel. Andrews et al. (2018) provide comprehensive anatomical and clinical evidence that flexion beyond 90° both narrows the tunnel and elevates compression forces, impairing intraneural blood flow and potentially compromising axonal transport [

2]. Nakashian et al. (2020) similarly highlight the role of elbow position in modifying tunnel volume and neural excursion, reinforcing the concept that sustained flexion is one of the mechanical drivers of ulnar nerve irritation [

1].

Recent experimental biomechanical work further strengthens this interpretation. Nagashima et al. (2022) quantified the strain applied to the ulnar nerve across varying degrees of elbow flexion [

16]. They demonstrated that as the elbow progresses from extension to deep flexion, the ulnar nerve undergoes measurable elongation and increasing tension, even in anatomically normal specimens. This strain was not dependent on deformity but inherent to the mechanics of flexion itself, providing compelling evidence that posture alone can impose significant biomechanical stress on the nerve. Their findings align precisely with the behavioral patterns observed in our CuTS cohort, who predominantly reported postures requiring sustained flexion, such as holding the smartphone near the face or chest during one-handed use. Electrophysiological and clinical data also corroborate these observations. Halac et al. (2015) reported that habitual postures involving prolonged flexion were among the most consistently identified risk factors in symptomatic patients [

17]. This reinforces the notion that posture-driven mechanical forces play a central role in the pathogenesis of CuTS and helps situate our findings within the broader context of clinical neuropathy research.

Longer smartphone use may increase the cumulative time spent in harmful positions, but the primary pathological trigger is the flexion-induced alteration in cubital tunnel biomechanics. This interpretation is entirely consistent with both our clinical findings and established physiological principles.

In this framework, elbow posture becomes the most clinically relevant variable. The frequent adoption of a flexed-elbow position during smartphone use, particularly during activities such as browsing, messaging, and video viewing, places the ulnar nerve in a position of repeated or prolonged mechanical stress. If compounded by individual anatomical predispositions (reduced tunnel volume, ligamentous stiffness, or age-related changes), even moderate exposure may be sufficient to trigger symptomatic compression. Such a model offers a rational explanation for the observed relationship between device-handling posture and CuTS, as well as the weaker association with total daily usage time.

Ultimately, this posture-dominant interpretation underscores the importance of considering ergonomics and biomechanics in evaluating contemporary risk factors for CuTS. As smartphone use continues to increase across all age groups, the relevance of these findings becomes increasingly significant for both clinicians and public health practitioners.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Literature

The results of the study conducted at our institute suggest a possible link between excessive smartphone use and cubital tunnel syndrome. Current literature has focused mainly on musculoskeletal problems of the hand and neck related to the use of mobile devices [

18]. The study by Agarwal et al. analyzed the relationship between prolonged smartphone use and a number of orthopedic conditions, including smartphone arthritis, cell phone elbow, carpal tunnel syndrome, osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joints, and gamer's thumb [

19]. Carpal tunnel syndrome associated with excessive smartphone use has become very common nowadays. Risk factors for CTS include prolonged periods of marked flexion or extension of the wrist, frequent use of flexor muscles, and exposure to vibration, factors commonly associated with smartphone use, as reported by Athar et al. [

20]. A cross-sectional study conducted at the Faculty of Medicine, Fırat University, revealed that the risk of CTS increases by 1.292 times for each additional hour of daily smartphone use [

21]. Another condition to consider is De Quervain's tenosynovitis. Another condition to consider is De Quervain's tenosynovitis. According to Mohammad Rehan et al., the frequency of De Quervain's disease is significantly correlated with the number of text messages sent per day. As the number of messages increases, so does the incidence of a positive Finkelstein test. It goes from 40% in those who send fewer than 50 messages, to 64% in those who send 50-100, to 45.7% in those who send 100-200, and up to 80.9% in those who send more than 200. This inflammation is caused by repeated gripping, grasping, or twisting movements [

22]. As explained above, the incidence of “cell phone elbow” is on the rise, especially among younger people. Increased elbow flexion, combined with prolonged maintenance of this position, puts strain on the nerve; the nerve itself can stretch from 4.5 to 8 mm. This reduces the space available for the nerve and increases the pressure inside the cubital tunnel according to Ukkirapandian K et al [

23]. Studies have shown that flexion maintained beyond 90° significantly increases the pressure inside the cubital tunnel , reducing the physiological gliding of the ulnar nerve [

24,

25]. The literature on peripheral neuropathies suggests that chronic mechanical stress can affect nerve physiology [

26]. It is also known that during nighttime rest, the elbow may remain flexed for prolonged periods, contributing to ulnar compression [

27]. The habit of using a smartphone in bed can therefore promote incorrect postures maintained during sleep, amplifying the neuropathic risk.

4.3. Epidemiological Implications

The excessive use of smartphones (especially among younger generations) and, above all, adopting incorrect posture could become a risk factor for ulnar neuropathy, contributing to an increase in cases of “cell phone elbow”. If confirmed, this could change the epidemiological profile of cubital tunnel syndrome, meaning it would no longer be limited to cases related to work or traditional posture. The excessive use of smartphones (especially among younger generations) and, above all, adopting incorrect posture could become a risk factor for ulnar neuropathy, contributing to an increase in cases of “cell phone elbow”. If confirmed, this could change the epidemiological profile of cubital tunnel syndrome, affecting not only cases related to work or traditional posture. The study conducted by Luca Padua et al showed that prolonged phone posture (PPP) can alter the electrophysiological function of the ulnar nerve [

28]. Of course, prevention is a key weapon in reducing the incidence of this condition. As regards the role of prevention, not all authors share the same opinion. Effective prevention could be achieved by subjecting the at-risk population to electrophysiological screening, as in the study conducted by Ukkirapandian K et al [

23]. A suggestion from various authors is to reduce the duration of time spent in an incorrect posture and to find more ergonomic positions that place less strain on the nervous system.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths and limitations. Among its strengths, it addresses a timely topic by examining the association between smartphone use and cubital tunnel syndrome. Collecting participant-reported smartphone usage provides insight into behavioral correlations with symptoms. The cross-sectional design offers a clear snapshot of the population, while the well-defined sample of 100 participants enables systematic assessment and lays a foundation for future longitudinal or interventional studies. However, the study also has limitations. The relatively small sample size may reduce statistical power and limit generalizability. Smartphone usage was self-reported, making it susceptible to recall bias and potential over- or underestimation. Moreover, the cross-sectional design precludes any evaluation of the longitudinal progression of cubital tunnel syndrome.

4.5. Future Directions

Future research should focus on prospective studies to clarify the temporal progression and relationship between the amount of time spent in the incorrect elbow flexion position and cubital tunnel syndrome. To do this, wearable inertial measurement units and continuous monitoring of elbow angle could be used. Advances in electroneurophysiology methods, including quantitative EMG, high-frequency ultrasound with elastography, and MR neurography, could give us a better understanding of the microstructural alterations in nerve tissue associated with repeated mechanical stress, with a view to developing predictive models capable of diagnosing the preclinical stages of compressive neuropathy. Randomised clinical trials dealing with ergonomic interventions such as the use of hands-free devices, elbow offloading strategies and behavioural modification to reduce the degree of continuous stress on the ulnar nerve.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that smartphone use may contribute to the development of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, particularly through the adoption of sustained elbow-flexion postures during device handling. While total daily smartphone time showed only a non-significant trend toward higher exposure among patients with CuTS, posture-related variables demonstrated a clear and statistically significant association with the condition. These findings suggest that ergonomic factors, especially prolonged elbow flexion, represent the primary mechanism linking smartphone use to ulnar nerve compression, whereas time alone appears to play a secondary, cumulative role.

Given the near-universal prevalence of smartphone use, increased awareness of posture during device handling may have meaningful implications for the prevention of ulnar neuropathy. Clinicians should routinely assess smartphone habits when evaluating patients with ulnar nerve symptoms, while public-health initiatives might consider promoting ergonomic strategies such as reducing prolonged elbow flexion, using headphones, supporting the forearm during use, and alternating hands.

Further prospective, biomechanically informed research, including objective measurement of elbow position during device use and integration of ultrasonographic assessment, will be essential to confirm these associations and to better define causal pathways. Nevertheless, the present findings highlight a modifiable behavioral factor that may be relevant in the growing incidence of compressive ulnar neuropathy in the modern digital era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F and S.P.; Methodology, C.F.; Validation, C.F. and L.R.; Formal Analysis, S.P.; Investigation, G.V., C.B and D.M.; Resources, G.V.; Data Curation, C.B.; Writing and Original Draft Preparation, C.F.; Writing, Review & Editing, C.B, G.V. and D.M.; Visualization, S.P; Supervision, C.F. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective design, which involved standard surgical procedures and the use of fully anonymized clinical data, in accordance with national regulations and institutional policies. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Nakashian, M.N.; Ireland, D.; Kane, P.M. Cubital tunnel syndrome: Current concepts. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020, 13, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.; Rowland, A.; Pranjal, A.; Ebraheim, N. Cubital tunnel syndrome: Anatomy, clinical presentation, and management. J Orthop. 2018, 15, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Woods, B.; Abubakar, T.; Koontz, C.; Li, N.; Hasoon, J.; Viswanath, O.; Kaye, A.D.; Urits, I. A Comprehensive Review of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2022, 14, 38239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.; Wolff, G.; Boyd, K.U. Evaluation of the scratch collapse test for carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome—A prospective, blinded study. J Hand Surg. 2020, 45, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, R.L.; Rayan, G. Diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2011, 36, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Orio, M.; Fulchignoni, C.; De Vitis, R.; Passiatore, M.; Taccardo, G.; Marzella, L.; Lazzerini, A. Feasibility of a fascial flap to avoid anterior transposition of unstable Ulnar nerve: A cadaver study. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2023, 42, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roger Powell, M.D. “Effects of Smartphones on our Fingers, Hands and Elbows”; The Orthopaedic Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Seo, K. The comparison of cervical repositioning errors according to smartphone addiction grades. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014, 26, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Park, R.Y.; Lee, S.J.; et al. The effect of the forward head posture on postural balance in long time computer based worker. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012, 36, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- "Extended Use of Smartphone Technology Cause Repetitive Upper Limb and Related Stress-strain Injuries and it's Impact on Home-isolation Covid-19 (Pandemic) Affected Population: Short Communication" by Manashi Dey. published in Acta Scientific Orthopaedics 2022, 5.3, 76–81.

- Rossignol, A.M.; Morse, E.P.; Summers, V.M.; et al. Video display terminal use and reported health symptoms among Massachusetts clerical workers. J Occup Med. 1987, 29, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.M. The effect of carpal tunnel changes on smartphone users. J Phys Ther Sci. 2012, 24, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.U. Impact of personal computer use on musculoskeletal symptoms in middle and high school students. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2002, 23, 760–768. [Google Scholar]

- Swetha, C.; Hema, M.; Sai, L.P.M.S.R.L.R.P.A. Ulnar Nerve Entrapment Among Cell Phone Users: Cell Phone Elbow (Cubital Tunnel Syndrome). Cureus 2024, 16, e55500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J. The relationship between smartphone use and subjective musculoskeletal symptoms and university students. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015, 27, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, M.; Omokawa, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Mahakkanukrauh, P.; Hasegawa, H.; Shimizu, T.; Kawamura, K.; Tanaka, Y. A cadaveric study of ulnar nerve strain at the elbow associated with cubitus valgus/varus deformity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022, 23, 36050700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Halac, G.; Topaloglu, P.; Demir, S.; Cıkrıkcıoglu, M.A.; Karadeli, H.H.; Ozcan, M.E.; Asil, T. Ulnar nerve entrapment neuropathy at the elbow: relationship between the electrophysiological findings and neuropathic pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015, 27, 2213–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gustafsson, E.; Thomée, S.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Hagberg, M. Texting on mobile phones and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults: A five-year cohort study. Applied Ergonomics 2017, 58, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Saurabh; Bharti, Rahul. Orthopedic Problems due to Overuse of Smartphones. Journal of Orthopaedic Diseases and Traumatology 2023, 6, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, Maryam; Hashmi, Javeria; Saleem, Muhammad Meeran; Azam, Javeria; Umar, Shahood Ahmed; Eljack, Mahmmoud Fadelallah; Mohammed. Impact of excessive phone usage on hand functions and incidence of hand disorders. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 2025, 87, 1794–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaçorlu, F.N.; Balgetir, F.; Pirinçci, E.; Deveci, S.E. The relationship between carpal tunnel syndrome, smartphone use, and addiction: A cross-sectional study. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022, 68, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asad, M.R.; Ahmad, R.K.; Almalki, H.A.; Alkhathami, K.M.; Alqahtani, B. Prevalence of De Quervain's Tenosynovitis among Teenage Mobile Users: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S3341–S3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ukkirapandian, K.; Vp, S.; Pawar, A.S.; Udaykumar, K.P.; Rangasmy, M. Ulnar Nerve Entrapment Among Cell Phone Users: Cell Phone Elbow (Cubital Tunnel Syndrome). Cureus 2024, 16, e55500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gelberman, R.H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hollstein, S.B.; Winn, S.S.; Heidenreich, F.P.; Bindra, R. Changes in interstitial pressure and cross-sectional area of the cubital tunnel with flexion of the elbow. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 1988, 70, 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, B.C.; Teran, V.A.; Deal, D.N. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an analysis of the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, C.B.; Mackinnon, S.E. Pathogenesis of peripheral nerve entrapment. Hand Clinics 2002, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, M.; Anand, P.; Das, J.M. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 14 Aug 2023; p. 30855847. [Google Scholar]

- Padua, L.; Coraci, D.; Erra, C.; Doneddu, P.E.; Granata, G.; Rossini, P.M. Prolonged phone-call posture causes changes of ulnar motor nerve conduction across elbow. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 2728–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).