1. Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most frequently encountered entrapment neuropathy [

1]. It is caused by compression of the median nerve (MN) as it passes through the carpal tunnel. The clinical diagnosis of CTS lacks a widely accepted gold standard however, with diagnoses often confirmed using electrodiagnostic testing (EDX) or ultrasonography (US) in clinical practice and research settings [

1,

2].

In the Netherlands, US is the recommended as the first-choice diagnostic test because it is easily accessible and painless [

3]. Various US parameters have been suggested in the literature for confirming CTS, and an increase of the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the MN at wrist level is the most commonly used [

4,

5]; however, there is no consensus in the literature about the upper limit of normal (ULN) of this CSA. A broad range of values for the ULN have been proposed, for example 9–15 mm2 in a post-hoc analysis [

6].

A strong correlation between the dimensions of the MN, particularly the CSA, and the wrist circumference (WC) was seen in an earlier study. Other anthropometric features were not independently correlated to CSA [

7]. Another study showed a positive correlation between WC and height and weight [

8]. The average height of the Dutch population (self-reported, 20 years or older) is the tallest in the world, at 169.3 cm for women and 182.9 cm for men born in 2001 [

9]. In the general healthy Italian population, the average height is shorter: 162.6 cm and 176.5 cm for women and men, respectively [

10]. If height indeed influences WC and the CSA of the MN at the wrist level, this could lead to differences in CTS diagnosis between the Italian and Dutch population.

In this study, we investigated the sensitivity of US in patients with CTS using a Dutch WC-dependent (WCD) equation for the ULN of the MN CSA at wrist level in samples of the Italian and Dutch population. We hypothesise that the WC in the shorter Italian population would be lower and, therefore, would lead to a lower calculated ULN for the MN CSA at wrist level. As a consequence, we expected that our equation would be similarly sensitive for patients with CTS from Italy and the Netherlands.

2. Materials and Methods

In this observational study, we included patients with CTS from the Siena University Hospital (Italy) and retrospectively enrolled patients with CTS from the Netherlands (Canisius-Wilhelmina Hospital, Zuyderland Hospital and Radboud university medical centre) [

11]. We obtained written informed consent from all patients and approval was waived by the local Medical Ethics Committee.

Patients with CTS aged 18 years and older were enrolled. They were eligible for inclusion if they complained of pain and/or paraesthesia in the region innervated by the MN. Furthermore, two of the following criteria had to be present: (1) paraesthesia relieved by shaking the hand (positive Flick sign), (2) aggravation of paraesthesia by certain activities (e.g. driving a car, biking, using a phone, holding a book) and (3) nocturnal paraesthesia. We excluded patients with a history or clinical signs of polyneuropathy, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies, previous trauma or surgery to the wrist, history of rheumatoid arthritis, arthrosis of the wrist, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, alcoholism and bifid MNs. The weight and height of all patients were measured. The WC were measured at the level of the distal wrist crease using a plastic measuring tape.

All participants underwent US and EDX studies according to previously described protocols [

12,

13]. In Italy, patients were enrolled in the study if the symptoms compatible with the clinical diagnosis of CTS were confirmed by EDX evidence of delay of the distal conduction velocity of the MN. Data was collected between February 2022 and December 2022. In the Netherlands, enrolment was based on a clinical diagnosis of CTS only, so patients with normal and abnormal nerve conduction studies were included. In the Netherlands, US was performed by experienced neurophysiology technicians, while in Siena, Italy, it was conducted by an experienced rheumatologist sonographer. The CSA of the MN at the carpal tunnel was outlined using the inner margin of the hyperechoic rim. The CSA was calculated by the area measurement software of the US system. In the Netherlands, a Hitachi Aloka Arietta 850 ultrasound system was used (5–17 MHz linear array transducer), while in Siena, a MyLab X8 eXP Esaote ultrasound system (4–15 MHz and 8–24 MHz linear probes) was used.

We compared the number of wrists with CTS confirmation using fixed values for the ULN of the CSA and a WCD ULN for the CSA. The fixed ULN was set at > 9 mm2 (ULN9) in the Italian laboratory [

14] and > 11 mm2 in the Dutch laboratories (ULN11) [

15]. The WCD ULN for the CSA was calculated as y=0.88*x-4 (y = ULN of the CSA in mm2 and x = WC in cm), as described in a previous study [

7]. These results were compared to the EDX studies.

A statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics (version 26.0). We determined the distribution of our data via Q–Q plots, histograms and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For categorical variables, we used the chi-square test, while continuous variables with a non-normal distribution were analysed using the Mann–Whitney test. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 displays the biometric characteristics of the patients. In total, 260 wrists of 230 patients with CTS were included. Patients included in Italy were significantly older, while patients in the Netherlands were taller and heavier. There were no differences in gender, median WC or median CSA of the MN between the groups. In Italy, the median duration of symptoms was significantly longer.

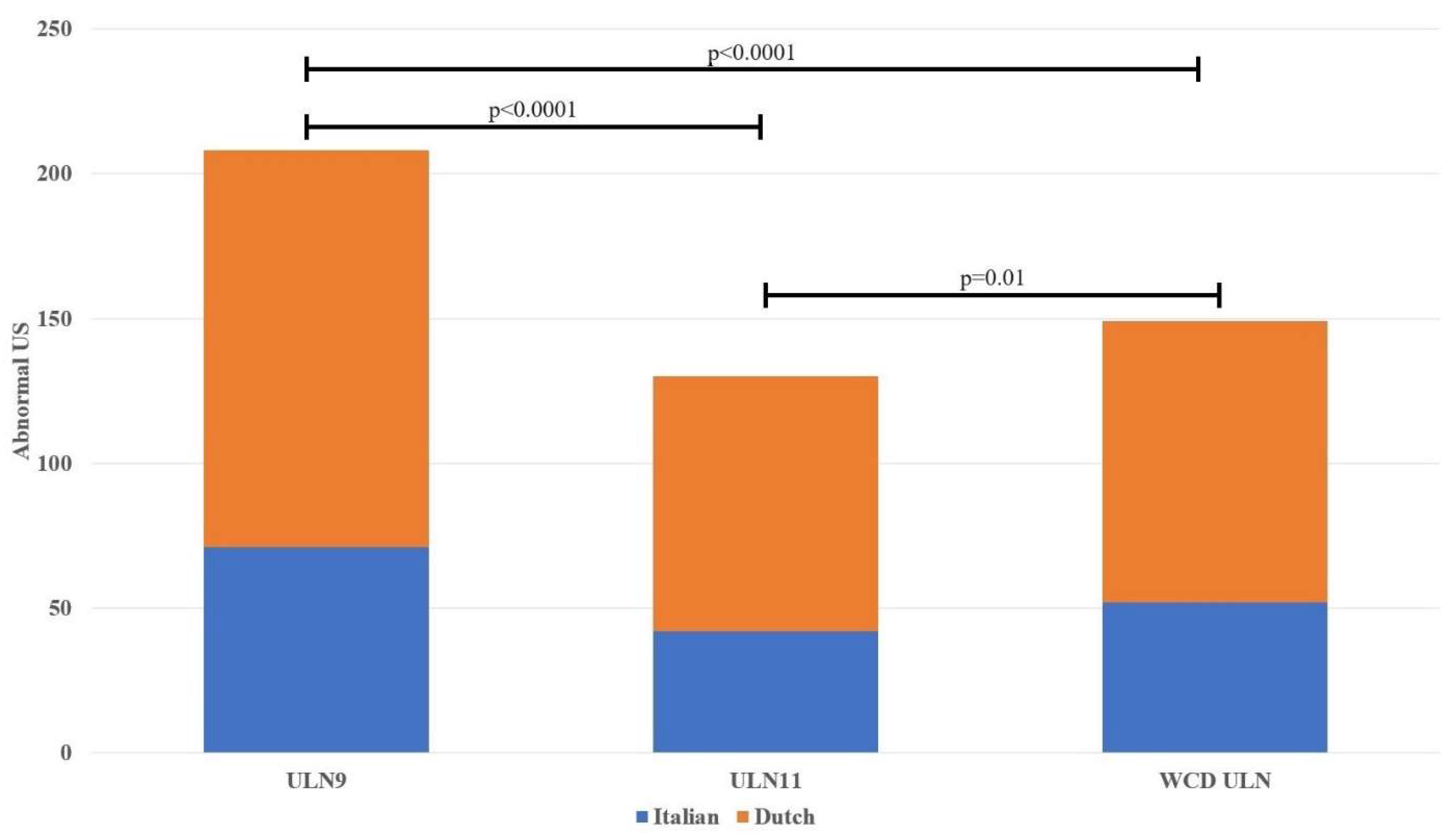

Table 2 presents the findings derived from the US and EDX studies. The relative number of abnormal wrists as determined by US (three previously defined ULN values for the MN CSA) was similar between the Italian and Dutch participants, including in the WCD results. Using the smallest ULN, the fixed ULN used in Italy, most US results were considered abnormal. A comparison of the number of abnormal US in both populations based on the different ULN values are presented in

Figure 1.

Table 3 shows the US results of a small selection of the Italian participants (n = 12) with WCs between 14.6 cm (–2 standard deviation) and 15.8 cm (–1 standard deviation).

4. Discussion

This study found that, in clinically defined patients with CTS, a Dutch WCD ULN for the MN CSA at the carpal tunnel could identify CTS with similar accuracies in both the Italian and Dutch population. The sensitivity of this method was poor in both populations, however. The application of the ULN developed by the Italian laboratory showed the highest sensitivity because of the relatively low cut-off value of 9 mm2.

It was hypothesised that the WCD formula would have a similar sensitivity in the Italian and Dutch participants despite their expected differences in WC and MN CSA. While the sensitivity was comparable, we found no differences in these anthropometric features. An earlier study showed a positive correlation between WC, height and weight [

8]. This would mean that taller people have a larger WC and consequently a larger MN CSA. While the Dutch population is the tallest in the world [

16], in this study the difference in height between the Italian and Dutch population was small. This might be partly explained by the fact that our data come from the southern provinces of the Netherlands, where the population is shorter than in the north [

9]. On the other hand, the patients enrolled in Italy came from Tuscany, where people are on average taller than those in several other Italian regions [

17]. The influence of past gene flows from southern Europe in the southern provinces of the Netherlands might also explain the similar WC and MN CSA measurements in the Dutch and Italian populations in this study. Migrational boundaries of this gene flow, especially the major Dutch rivers, could explain the differences between provinces in the Netherlands [

18]. The Dutch data from this study was obtained from people living south of the major Dutch rivers.

While many studies have gathered data for normative value of the MN CSA [

4], few studies primarily looked at population differences. In healthy participants, one study showed that, after correction for age, height and weight, the MN CSA difference between Indian and Dutch participants was still significant [

19]. A systematic review concerning normative reference values for the MN CSA identified several differences between ethnicities, but it was noted that the majority of included studies did not report sub-population ethnicity [

20]. One study compared data for patients with CTS collected by an American (USA) laboratory and an Italian laboratory, and found strong similarities between the MN CSA at forearm level. While the wrist-to-forearm ratio (WFR) was higher in the USA (because of a significantly larger mean MN CSA at wrist level), both ratios were considered elevated compared with the controls [

21]. Here, we found no difference in the MN CSA at wrist level between the Dutch and Italian participants.

One unexpected finding was the low sensitivity of the WCD equation in both the Dutch and Italian population. We do not have a good explanation for this. An earlier study showed a higher sensitivity for this equation in a different Dutch population [

7]. The age of our study population was higher than in this previous study and could play a part in the lower sensitivity. There are several approaches to improve diagnostic accuracy. A disease-specific cut-off value can be used and, as is common in nerve conduction studies as well, patients can serve as their own controls [

22]. In patients with CTS, the WFR is commonly used and, more recently, the nerve/tendon ratio showed promise as an anthropometric-independent ULN [

14,

23].

We also looked at a small selection of our Italian population (n = 12) with particularly small WCs (between 14.6 cm (–2 standard deviation) and 15.8 cm (–1 standard deviation)); these WCs were less common in the Dutch population. The Dutch WCD ULN considered the US readings of eight of these 12 patients (66.7%) to be abnormal, while the ULN9 calculation considered nine readings to be abnormal (75.0%). Conversely, using ULN11 in this subpopulation, only 25% of the scanned MNs would be classified as abnormal. As reported before, we believe that a WCD cut-off value can add value, especially in patients with CTS who have small wrists [

11].

There are several limitations to this study. First, the median duration of symptoms was significantly longer in the Italian population than in the Dutch patients. The literature has conflicting results regarding the effect of symptom duration and MN CSA at the wrist level [

24,

25,

26,

27]. As mentioned before, patients in Italy were significantly older, and it is known that the sensitivity of the MN CSA as a cut-off value is lower in older patients with CTS than in younger patients [

28,

29]. A recent expert panel advised that EDX studies should be performed in individuals aged over 70 [

30]. Furthermore, all patients in Italy had abnormal EDX results, while some of the Dutch patients were included on the basis of a clinical CTS diagnosis despite normal EDX findings. We cannot exclude the possibility of misdiagnosis in some patients in the Netherlands, which could influence the diagnostic accuracy in this study.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates that a Dutch-derived formula for determining a WCD cut-off value for the MN CSA at the carpal tunnel, among individuals diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome, yielded comparable outcomes among Italian and Dutch cohorts. This formula may offer heightened utility among individuals with diminutive wrist dimensions. We found no differences in WC or MN CSA at wrist level between these two groups. Furthermore, this observational study shows the importance of establishing local normative values for the ULN of the MN area at the wrist used to confirm the clinical diagnosis of CTS.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Federica Ginanneschi, Paolo Falsetti, Wim I.M. Verhagen and Tom B.G. Olde Dubbelink. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tom B.G. Olde Dubbelink and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval for this study were waived following consultation with the local ethics committee in Siena, as data collection was conducted as part of standard care, with no additional tests or discomfort imposed on the participating patients.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for participating and our neurophysiology technicians for their contributions to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Padua L, Coraci D, Erra C, et al Carpal tunnel syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol 2016, 15, 1273–1284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoo M, Menkes DL, Bland JDP, Burke D Nerve conduction studies and EMG in carpal tunnel syndrome: Do they add value? Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2018, 3, 78–88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (2017) Richtlijn carpaletunnelsyndroom.

- Tai TW, Wu CY, Su FC, et al Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Ultrasound Med Biol 2012, 38, 1121–1128. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchberger W, Judmaier W, Birbamer G, et al Carpal tunnel syndrome: Diagnosis with high-resolution sonography. American Journal of Roentgenology 1992, 159, 793–798. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekman R, Visser LH Sonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: A critical review of the literature. Muscle Nerve 2003.

- Olde Dubbelink TBG, De Kleermaeker FGCM, Meulstee J, et al Augmented diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for diagnosing carpal tunnel syndrome using an optimised wrist circumference-dependent cross-sectional area equation. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 577052. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kleermaeker FGCM, Meulstee J, Verhagen WIM The controversy of the normal values of ultrasonography in carpal tunnel syndrome: diagnostic accuracy of wrist-dependent CSA revisited. Neurological Sciences 2019, 40, 1041–1047. [CrossRef]

- CBS, GGD, RIVM (2019) Lichaamsgroei 1981–2018: recent vooral gewichtstoename. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2019/48/lichaamsgroei-1981-2018-recent-vooral-gewichtstoename.

- Cacciari E, Milani S, Balsamo A, et al Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 20 yr). J Endocrinol Invest 2006, 29, 581–593. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olde Dubbelink TB, GCM De Kleermaeker F, Beekman R, et al Wrist circumference-dependent upper limit of normal for the cross-sectional area is superior over a fixed cut-off value in confirming the clinical diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Claes F, Meulstee J, Claessen-Oude Luttikhuis TTM, et al Usefulness of additional measurements of the median nerve with ultrasonography. Neurological Sciences 2010, 31, 721–725. [CrossRef]

- Claes F, Kasius KM, Meulstee J, Verhagen WIM Comparing a new ultrasound approach with electrodiagnostic studies to confirm clinically defined carpal tunnel syndrome: A prospective, blinded study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 92, 1005–1011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsetti P, Conticini E, Baldi C, et al A Novel Ultrasonographic Anthropometric-Independent Measurement of Median Nerve Swelling in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: The “Nerve/Tendon Ratio” (NTR). Diagnostics 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Visser LH, Smidt MH, Lee ML High-resolution sonography versus EMG in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008, 79, 63–67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönbeck Y, Talma H, Van Dommelen P, et al The world’s tallest nation has stopped growing taller: The height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009. Pediatr Res 2013, 73, 371–377. [CrossRef]

- Miguel Martínez-carrión Ramón María-dolores J (2017) E A REGIONAL INEQUALITY AND CONVERGENCE IN SOUTHERN EUROPE. EVIDENCE FROM HEIGHT IN ITALY AND SPAIN, 1850-2000 *.

- Byrne RP, van Rheenen W, van den Berg LH, et al Dutch population structure across space, time and GWAS design. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Burg EW Van, Bathala L, Visser LH Difference in normal values of median nerve cross-sectional area between dutch and indian subjects. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 129–132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng AJT, Chandrasekaran R, Prakash A, Mogali SR A systematic review: normative reference values of the median nerve cross-sectional area using ultrasonography in healthy individuals. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hobson-Webb LD, Padua L Median nerve ultrasonography in carpal tunnel syndrome: Findings from two laboratories. Muscle Nerve. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Goedee HS, van Alfen N The use and misuse of sonographic reference values in neuromuscular disease. Muscle Nerve 2023, 68, 1–3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson-Webb LD, Massey JM, Juel VC, Sanders DB The ultrasonographic wrist-to-forearm median nerve area ratio in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Ikumi A, Yoshii Y, Kudo T, et al Potential Relationships between the Median Nerve Cross-Sectional Area and Physical Characteristics in Unilateral Symptomatic Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Patients. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Park JS, Won HC, Oh JY, et al Value of cross-sectional area of median nerve by MRI in carpal tunnel syndrome. Asian J Surg 2020, 43, 654–659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen SF, Lu CH, Huang CR, et al Ultrasonographic median nerve cross-section areas measured by 8-point “inching test” for idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: A correlation of nerve conduction study severity and duration of clinical symptoms. BMC Med Imaging 2011, 11. [CrossRef]

- Arı B, Akçiçek M, Taşcı I, et al Correlations between transverse carpal ligament thickness measured on ultrasound and severity of carpal tunnel syndrome on electromyography and disease duration. Hand Surg Rehabil 2022, 41, 377–383. [CrossRef]

- Mulroy E, Pelosi L Carpal tunnel syndrome in advanced age: A sonographic and electrodiagnostic study. Muscle Nerve 2019, 60, 236–241. [CrossRef]

- Moschovos C, Tsivgoulis G, Kyrozis A, et al The diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution ultrasound in screening for carpal tunnel syndrome and grading its severity is moderated by age. Clinical Neurophysiology 2019, 130, 321–330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi L, Arányi Z, Beekman R, et al Expert consensus on the combined investigation of carpal tunnel syndrome with electrodiagnostic tests and neuromuscular ultrasound. Clinical Neurophysiology 2022, 135, 107–116. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).