Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

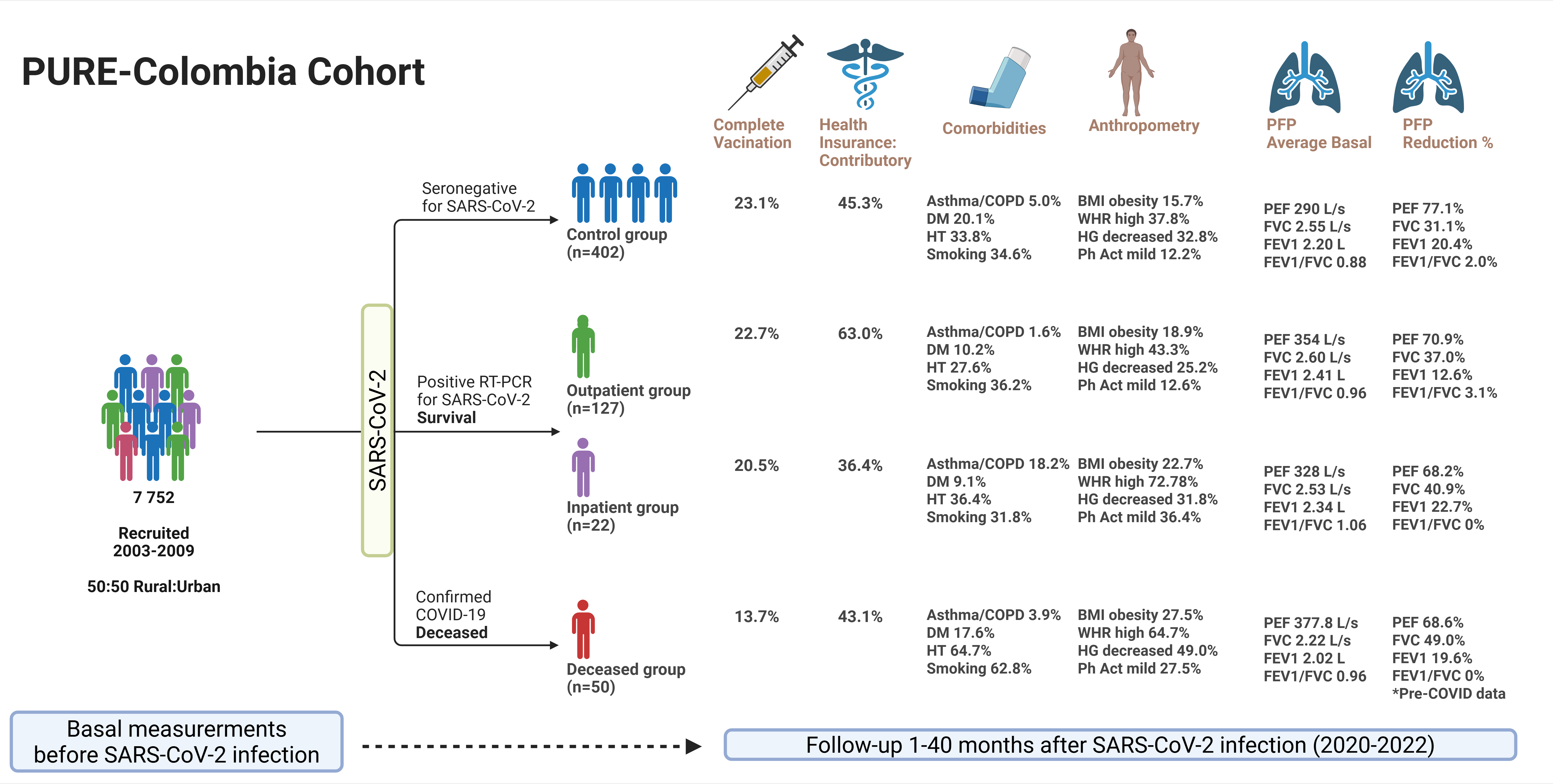

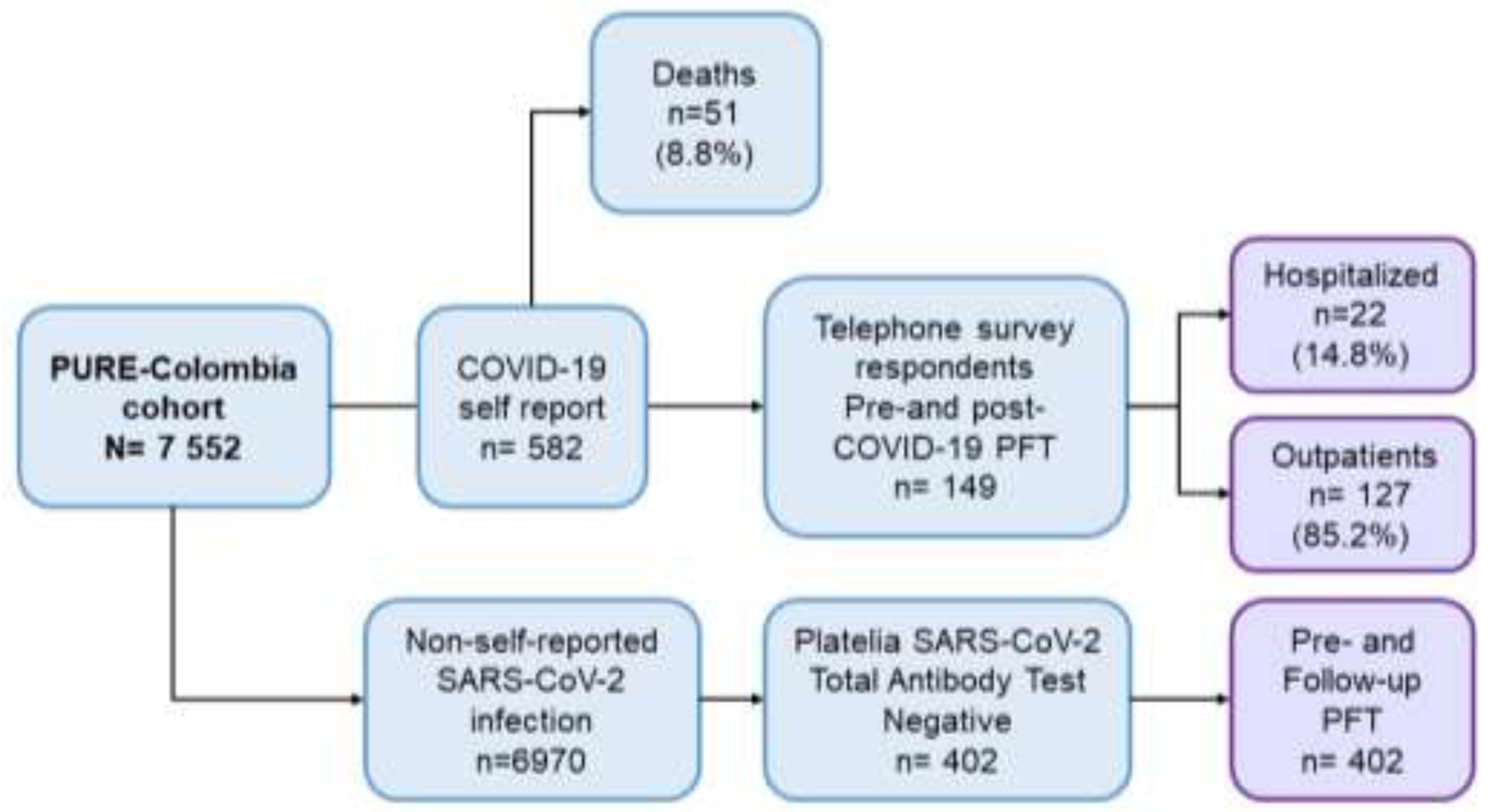

2.1. Sample

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Spirometry

2.4. Handgrip Strength (HS)

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

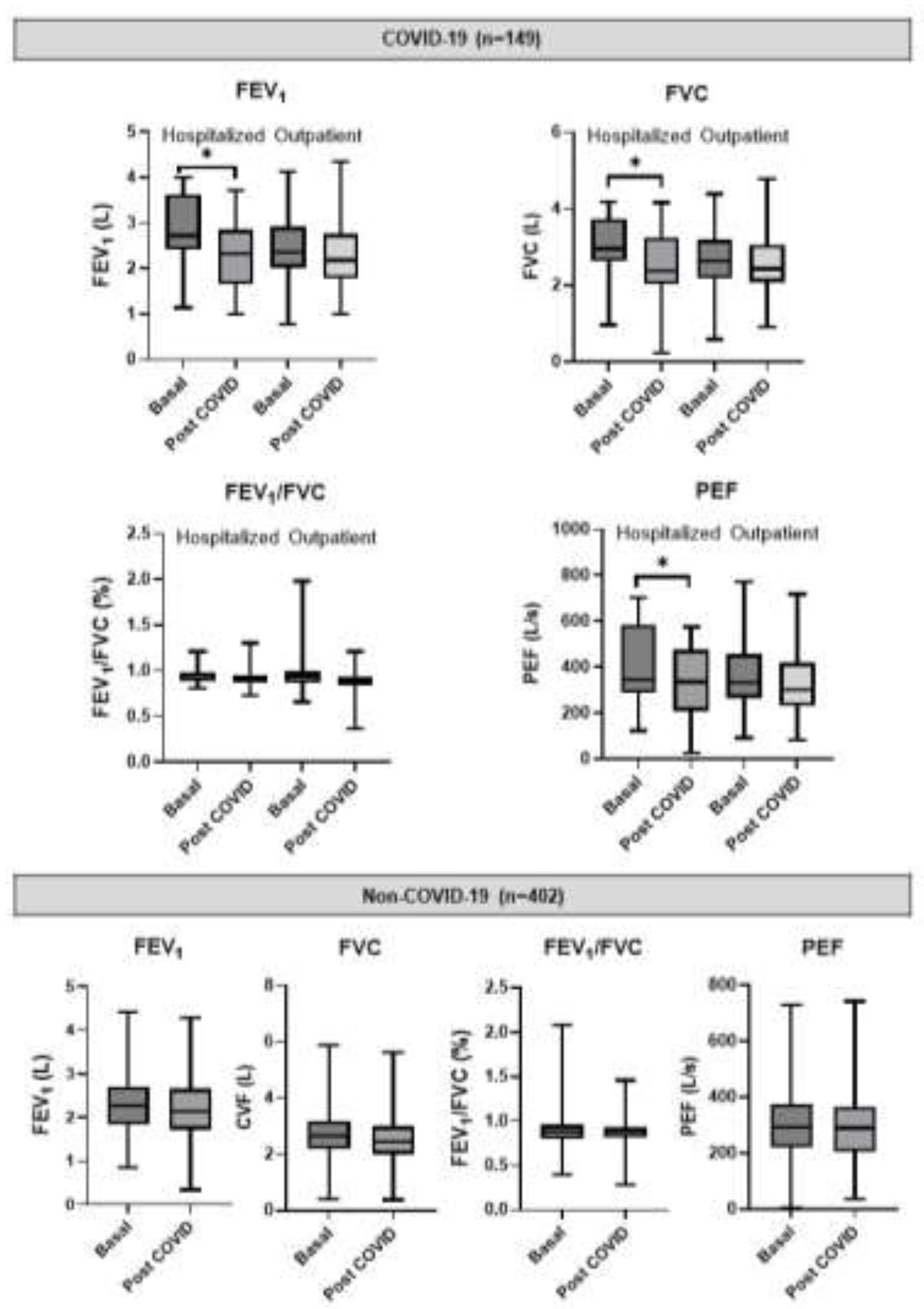

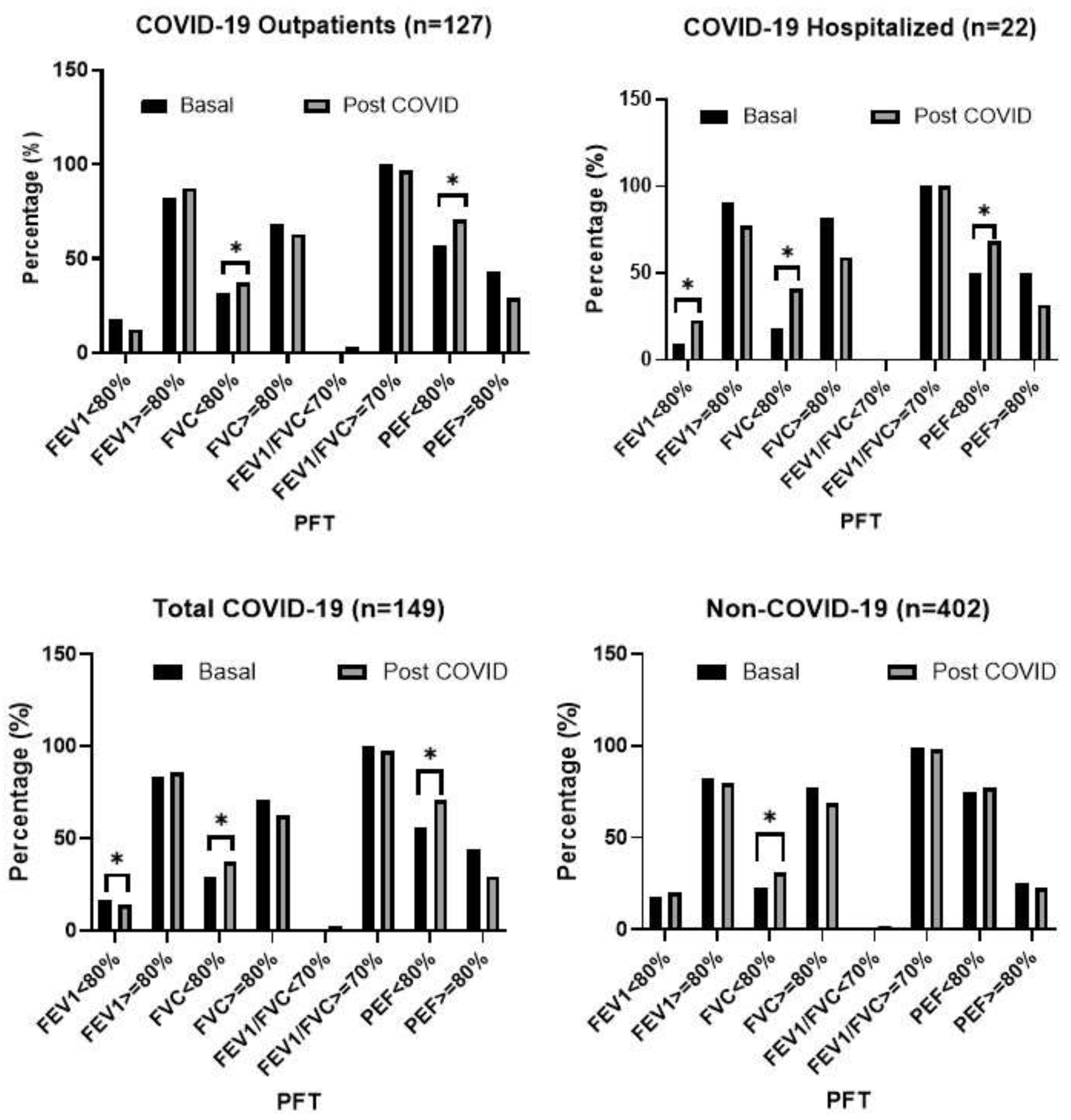

3.2. Post-COVID-19 Spirometry

3.3. Predicted Values of LFT

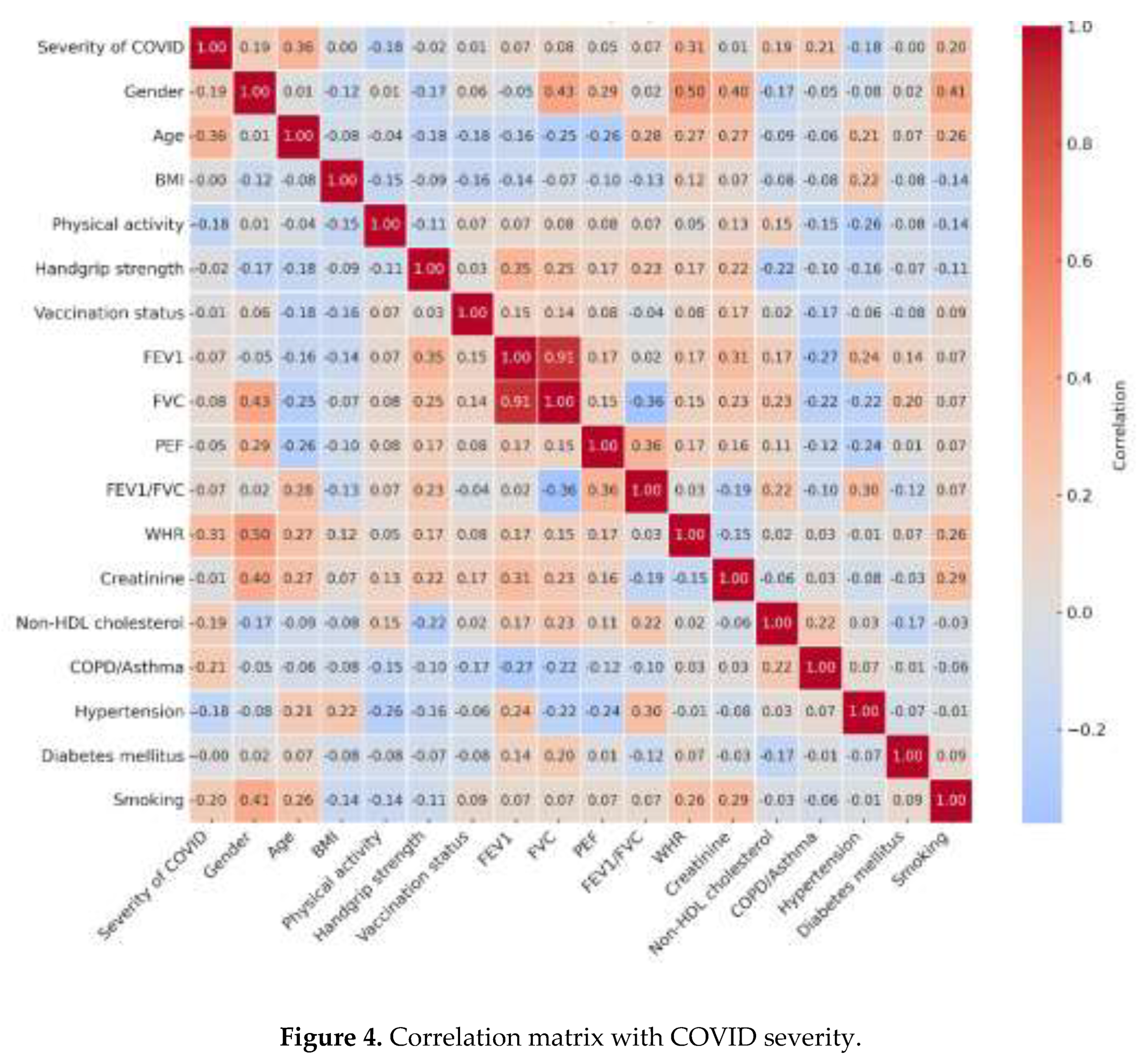

3.4. Association Between Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics with Post-COVID LF

3.5. Association Between Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics with Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| LF | Lung Function |

| PURE | Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| PFT | Pulmonary Function Test |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| PEF | Peak Expiratory Flow |

| GLI | Global Lung Initiative |

| HS | Handgrip Strength |

| WHR | Waist-to-Hip Ratio |

References

- Zhu, N; Zhang, D; Wang, W; Li, X; Yang, B; Song, J; Zhao, X; Huang, B; Shi, W; Lu, R; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382(8), 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, DS; Joynt, GM; Wong, KT; Gomersall, CD; Li, TS; Antonio, G; Ko, FW; Chan, MC; Chan, DP; Tong, MW; et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Thorax. 2005, 60(5), 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, KC; Ng, AW; Lee, LS; Kaw, G; Kwek, SK; Leow, MK; Earnest, A. 1-year pulmonary function and health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chest. 2005, 128(3), 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsin, E; Demirkol, ME. Post-COVID pulmonary function test evaluation. Turk Thorac J. 2022, 23(6), 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H; Han, X; Jiang, N; Cao, Y; Alwalid, O; Gu, J; Fan, Y; Zheng, C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020, 20(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, MK; Goyal, A; Kaur, A; Sood, N; Aggarwal, R; Gupta, N; Gupta, R; Jain, S; Kumar, A; Sharma, A; et al. Persistent respiratory symptoms and lung function abnormalities in recovered patients of COVID-19. Lung India. 2023, 40(6), 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Castro, R; Vasconcello-Castillo, L; Alsina-Restoy, X; Solis-Navarro, L; Burgos, F; Puppo, H; Vilaró, J. Respiratory function in patient’s post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology. 2021, 27(4), 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppini, N; Tana, C; Ticinesi, A; Nouvenne, A; Meschi, T; Lauretani, F; Maggio, M; Prati, B; Pedone, C; Manfellotto, D; et al. Longitudinal analysis of pulmonary function impairment one year post-COVID-19: a single-center study. J Pers Med. 2023, 13(8), 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udwadia, ZF; Koul, PA; Richeldi, L. Post-COVID lung fibrosis: the tsunami that will follow the earthquake. Lung India. 2021, 38 (Suppl 1), S41–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, MEB; Scheerder, MJ; Gijbels, K; Van Braeckel, E; Janssens, W; Van Meerbeeck, JP; Vansteenkiste, J; Vande Velde, S; Troosters, T; Decramer, M; et al. Pulmonary function 3–6 months after acute COVID-19: a systematic review and multicentre cohort study. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e27964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H; Shang, W; Liu, Q; Zhang, X; Zheng, M; Yue, M; Li, X; Yang, Y; Fan, Y; Wang, Y; et al. Lung-function trajectories in COVID-19 survivors after discharge: a two-year longitudinal cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022, 54, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y; Tan, C; Wu, J; Chen, M; Wang, Z; Luo, L; Zhou, X; Liu, X; Huang, X; Yuan, S; et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on pulmonary function in early convalescence phase. Respir Res. 2020, 21, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L; Barisione, E; Mastracci, L; Campora, M; Costa, D; Robba, C; Battaglini, D; Brunetti, I; Fiasella, S; Giacobbe, DR; et al. Extension of collagen deposition in COVID-19 postmortem lung samples and computed tomography analysis findings. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisione, E; Grillo, F; Ball, L; Bianchi, R; Grosso, M; Morbini, P; Mastracci, L; Fiocca, R; Patroniti, N; De Lucia, A; et al. Fibrotic progression and radiologic correlation in matched lung samples from COVID-19 postmortems. Virchows Arch. 2021, 478, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mara, G; Gheorghe, N; Cotoraci, C. Impact of pulmonary comorbidities on COVID-19: acute and long-term evaluations. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(5), 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemba, ELP; Okombi, FO; Moyikoua, R; Bopaka, RG; Koumeka, PP; Ossale-Abacka, KB; Moukassa, D; Mboussa, J. Post-COVID-19 pneumonia: long-term radiographic and spirometric outcomes. J Pan Afr Thorac Soc. 2024, 5(3), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero Huguet, E; García-Pachón, E; Ruiz-Manzano, J; Sánchez-Salcedo, P; Ussetti, P; de-Torres, JP; Soler-Cataluña, JJ; Martínez-García, MA. Alteración funcional pulmonar en el seguimiento precoz de pacientes con neumonía por COVID-19. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, I; Almer, S; Gustafsson, A; Karlsson, J; Andersson, M; Rosengren, A; Jernberg, T; Hansson, PO; Strandberg, E; Johansson, G; et al. Lung functions before and after COVID-19 in young adults: a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob. 2022, 1(2), 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, RR; Alnuaimi, AS; Al-Shamsi, M; AlKaabi, S; AlBlooshi, M; AlMazrouei, N; AlKaabi, A; AlHosani, F; AlZaabi, A; AlSuwaidi, J; et al. A comparison of pulmonary function pre and post mild SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthy adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2025, 25, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K; Chow, CK; Vaz, M; Rangarajan, S; Yusuf, S. The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: examining the impact of societal influences on chronic noncommunicable diseases in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Am Heart J. 2009, 158(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, CL; Marshall, AL; Sjostrom, M; Bauman, AE; Booth, ML; Ainsworth, BE; Pratt, M; Ekelund, U; Yngve, A; Sallis, JF; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35(8), 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, SA; Hu, W; Rangarajan, S; Gasevic, D; Leong, D; Iqbal, R; Casanova, A; Swaminathan, S; Anjana, RM; Kumar, R; et al. The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries. Lancet. 2017, 390(10113), 2643–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, MR; Hankinson, J; Brusasco, V; Burgos, F; Casaburi, R; Coates, A; Crapo, R; Enright, P; van der Grinten, CPM; Gustafsson, P; et al. Standardisation of lung function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005, 26(2), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M; Islam, S; Rangarajan, S; Leong, D; Kurmi, O; Teo, K; Killian, K; Dagenais, G; Lear, S; Yusuf, S; et al. Global differences in lung function by region (PURE): an international, community-based prospective study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013, 1(8), 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M; Rangarajan, S; Zaman, M; Teo, K; Killian, K; Dagenais, G; Lear, S; Yusuf, S; Seron, P; Yeates, K; et al. Differences and agreement between two portable hand-held spirometers across diverse community-based populations in the PURE study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022, 2(2), e0000141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowerman, C; Bhakta, NR; Brazzale, D; Cooper, BR; Cooper, J; Gochicoa-Rangel, L; Hall, GL; Kulkarni, T; Miller, MR; Pellegrino, R; et al. A racially neutral approach to the interpretation of lung function measurements. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023, 207, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, DP; Teo, KK; Rangarajan, S; Kutty, VR; Lanas, F; Hui, C; Quanyong, X; Zhenzhen, Q; Jinhua, T; Noorhassim, I; et al. Reference ranges of handgrip strength from 125 462 healthy adults in 21 countries. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016, 7(5), 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E; Altman, DG; Egger, M; Pocock, SJ; Gøtzsche, PC; Vandenbroucke, JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 147(8), 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E; Altman, DG; Egger, M; Pocock, SJ; Gøtzsche, PC; Vandenbroucke, JP; et al. The STROBE reporting checklist. EQUATOR Netw. 2025. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/.

- Iversen, KK; Andersen, O; Hansen, EF; Omland, LH; Mogensen, CB; Gerds, TA; Lundgren, J; Benfield, T; Jensen, JS. Lung function decline in relation to COVID-19 in the general population. J Infect Dis. 2022, 225(8), 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, KL; Helgeson, SA; Tattersall, MC; Mandler, WK; Chinchilli, VM; Blaha, MJ. COVID-19 and the effects on pulmonary function following infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2021, 39, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostancı, Ö; Karaduman, E; Çolak, Y; Yılmaz, A.K; Kabadayı, M; Bilgiç, S. Respiratory muscle strength and pulmonary function in unvaccinated athletes before and after COVID-19 infection. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2023, 308, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippoliti, L; Coppeta, L; Somma, G; Bizzarro, G; Borelli, F; Crispino, T; Ferrari, C; Iannuzzi, I; Mazza, A; Paolino, A; et al. Pulmonary function assessment after COVID-19 in vaccinated healthcare workers. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2023, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, CB; Golden, CA; Kanner, RE; Renzetti, AD. Effect of viral infections on pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 1980, 141(3), 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanson, WG; Pierce, AK; Sanford, JP. Pulmonary function in uncomplicated influenza. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969, 100(2), 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X; Jian, W; Su, Z; Chen, M; Peng, H; Peng, P; Lei, C; Li, S; Chen, R; Zhong, N; et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J. 2020, 55(6), 2001217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, DP; Thaweethai, T; Karlson, EW; Bonilla, H; Horne, BD; Mullington, JM; Wisnivesky, JP; Hornig, M; Shinnick, DJ; Klein, JD; et al. Sex differences in long COVID. JAMA Netw Open. 2025, 8(1), e2455430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Willigen, DG; Vos, M; Beenen, LFM; van der Plaat, DA; Ten Hacken, NHT; Postma, DS; Lahousse, L; van den Berge, M; Franssen, FME; Spruit, MA; et al. One-fourth of COVID-19 patients have an impaired pulmonary function after 12 months. PLoS One. 2023, 18(9), e0290893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, IO; Benitez, A; McKinnell, JA; Shah, R; Waters, M; Hunter, BD; Jeanfreau, R; Tsai, L; Neighbors, M; Trzaskoma, B; et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of adults hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025, 31(6), 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, CS; Bin Ibrahim, MA; Binti Azhar, NA; Binti Roslan, Z; Binti Harun, R; Krishnabahawan, SL; Karthigayan, AAP; Binti Abdul Kadir, RF; Binti Johari, B; Ng, DL-C; et al. Post-discharge spirometry evaluation in patients recovering from moderate-to-critical COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 16413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, AC; Palstam, A; Ashman Kröönström, L; Sunnerhagen, KS; Persson, HC. Factors associated with aspects of functioning one year after hospitalization due to COVID-19. Clin Rehabil. 2025, 39, 02692155241311852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, L; Guerini, M; Giordani, J; Levi, G; Latronico, N; Piva, S; Peli, E; Benoni, R; Pini, A; Zucchi, G; et al. 24-month assessment of respiratory function in patients hospitalized for severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Respir Med. 2024, 219, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli, A; Misuraca, C; Bianchi, A; Borsa, N; Limonta, S; Maggiolini, S; Bonardi, DR; Corsonello, A; Di Rosa, M; Soraci, L; et al. Long-term changes in pulmonary function among patients surviving COVID-19 pneumonia. Infection. 2022, 50, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietranis, KA; Izdebska, WM; Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A; Dakowicz, A; Ciołkiewicz, M; Kaniewska, K; Dzięcioł-Anikiej, Z; Wojciuk, M. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on respiratory function and diaphragm thickness in post-COVID-19 syndrome. J Clin Med. 2024, 13(2), 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. Study: waist-to-hip ratio might predict mortality better than BMI. JAMA. 2023, 330(16), 1515–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A; Caroli, A; Bonaffini, PA; Conti, C; Arrigoni, A; Mercanzin, E; Imeri, G; Anelli, M; Balbi, M; Pace, M; et al. Structural and functional pulmonary assessment in severe COVID-19 survivors after Discharge. Tomography. 2022, 8(5), 2588–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, CMSSB; Goulart, CdL; Silva, BM; Valente, J; Rezende, AG; Fernandes, E; Cubas-Vega, N; Silva Borba, MG; Sampaio, V; Monteiro, W; et al. Low handgrip strength is associated with worse functional outcomes in long COVID. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, C; Olschewski, H; Sorichter, S; Uezgoer, G; Diehm, C; Huppert, P; Iber, T; Herth, FM; Harutyunova, S; Marra, AM; et al. Impairment of inspiratory muscle function after COVID-19. Respiration. 2022, 101(11), 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockele, LF; Affonso, JVS; Rossi, D; Eibel, B. Pulmonary and functional rehabilitation improves functional capacity in post-COVID-19 patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19(22), 14899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaza-Domingues, KLT; Ramos-Milaré, ÁCFH; Lera-Nonose, DSSL; Brustolin, AÁ; de Oliveira, LF; Rosa, JS; Otofuji Inada, AY; Dias Leme, AL; Pinel, BI; Perina, BS; et al. Effect of comorbidities on mortality of patients with COVID-19. Rev Med Virol. 2025, 35(2), e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G; Dael, N; Verweij, S; Balafas, S; Mubarik, S; Oude Rengerink, K; Pasmooij, AMG; van Baarle, D; Mol, PGM; de Bock, GH; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes. Eur Respir Rev. 2025, 34(175), 240222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, M; Roberts, MJ; Bishop, NC. High grip strength attenuates risk of severe COVID-19 in males but not females with obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2023, 17(1), 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, S; Allafasghari, A; Allafasghari, A; Abouhossein, A. Handgrip strength as a prognostic factor for COVID-19 mortality among older adults. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 19927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucci, G; Lattanzi, S; Pezzella, FR; Martino, F; Cavallari, F; Salerno, G; Ricci, A; D’Alessandro, AG; Chiappetta, R; et al. Handgrip strength is associated with adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia. Intern Emerg Med. 2022, 17(7), 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, FCS; Andrade, MF; Gatti da Silva, GH; Faiad, JZ; Barrére, APN; Gonçalves, RdC; de Castro, GS; Seelaender, M. Function over mass: importance of skeletal muscle quality in COVID-19 patients. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 837719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Non-COVID-19 (n=402) | COVID-19 (n=149) | Total population (n=551) | p-value* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatients (n=127) | Hospitalized (n=22) | Total (n=149) | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 267 | 66.4 | 84 | 66.1 | 11 | 50.0 | 95 | 63.8 | 362 | 65.7 | 0.629 |

| Male | 135 | 33.6 | 43 | 33.9 | 11 | 50.0 | 54 | 36.2 | 189 | 34.3 | ||

| Age | < 60 years | 109 | 27.1 | 58 | 45.7 | 7 | 31.8 | 65 | 43.6 | 174 | 31.6 | <0.001 |

| ≥ 60 years | 293 | 72.9 | 69 | 54.3 | 15 | 68.2 | 84 | 56.4 | 377 | 68.4 | ||

| Educational level | Low 1 | 295 | 73.4 | 64 | 50.4 | 14 | 63.6 | 78 | 52.3 | 373 | 67.7 | <0.001 |

| Middle 2 | 71 | 17.7 | 30 | 23.6 | 4 | 18.2 | 34 | 22.8 | 105 | 19.1 | ||

| High 3 | 36 | 8.9 | 33 | 26.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 37 | 24.8 | 73 | 13.2 | ||

| Health insurance4 | Contributory | 182 | 45.3 | 80 | 63.0 | 8 | 36.4 | 88 | 59.1 | 270 | 49.0 | 0.005 |

| Subsidized 4 | 220 | 54.7 | 47 | 37.0 | 14 | 63.6 | 61 | 40.9 | 281 | 51.0 | ||

| Place of residence | Urban | 246 | 61.2 | 57 | 44.9 | 13 | 59.1 | 70 | 47.0 | 316 | 57.4 | 0.003 |

| Rural | 156 | 38.8 | 70 | 55.1 | 9 | 40.9 | 79 | 53.0 | 235 | 42.6 | ||

|

Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) |

Normal: 18.5-24.9 | 174 | 43.3 | 47 | 37.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 51 | 34.2 | 225 | 40.8 | 0.068 |

| Overweight: 25-29.9 | 165 | 41.0 | 56 | 44.1 | 13 | 59.1 | 69 | 46.3 | 234 | 42.5 | ||

| Obesity: ≥ 30 | 63 | 15.7 | 24 | 18.9 | 5 | 22.7 | 29 | 19.5 | 92 | 16.7 | ||

| Background | Smoking | 139 | 34.6 | 46 | 36.2 | 7 | 31.8 | 53 | 35.6 | 192 | 34.8 | 0.907 |

| COPD / asthma | 20 | 5.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 4 | 18.2 | 6 | 4.0 | 26 | 4.7 | 0.810 | |

| Hypertension | 136 | 33.8 | 35 | 27.6 | 8 | 36.4 | 43 | 28.9 | 179 | 32.5 | 0.315 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 81 | 20.1 | 13 | 10.2 | 2 | 9.1 | 15 | 10.1 | 96 | 17.4 | 0.008 | |

|

Physical activity level (min/week) |

Mild <150 | 49 | 12.2 | 16 | 12.6 | 8 | 36.4 | 24 | 16.1 | 73 | 13.2 | 0.287 |

| Moderate 150 – 750 | 146 | 36.3 | 50 | 39.4 | 8 | 36.4 | 58 | 38.9 | 204 | 37.0 | ||

| High > 750 | 207 | 51.5 | 61 | 48.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 67 | 45.0 | 274 | 49.7 | ||

| Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) | Normal5 | 250 | 62.2 | 72 | 56.7 | 6 | 27.3 | 78 | 52.3 | 328 | 59.5 | 0.046 |

| High | 152 | 37.8 | 55 | 43.3 | 16 | 72.7 | 71 | 47.7 | 123 | 40.5 | ||

|

Handgrip strength (kg) |

Normal | 270 | 67.2 | 95 | 74.8 | 15 | 68.2 | 110 | 73.8 | 380 | 69.0 | 0.162 |

| Decreased 6 | 132 | 32.8 | 32 | 25.2 | 7 | 31.8 | 39 | 26.2 | 171 | 31.0 | ||

| Vaccination status prior to COVID-19 | Complete scheme 7 | 93 | 23.1 | 116 | 91.3 | 14 | 63.6 | 31 | 20.8 | 124 | 22.5 | 0.640 |

| No vaccine dose | 289 | 71.9 | 6 | 4.7 | 6 | 27.3 | 100 | 67.1 | 389 | 70.6 | ||

| Incomplete scheme | 20 | 5.0 | 5 | 3.9 | 2 | 9.1 | 18 | 12.1 | 38 | 6.9 | ||

|

Laboratories (mg/dL) (mean ± SD) |

Creatinine | 0.9±0.2 | 0.99±0.24 | 0.97±0.22 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 161.8±45.7 | 152.0±44.0 | 170.0±33.0 | 154.0±43.1 | 160.5±45.2 | 0.079 | ||||||

| Triglycerides | 174.1±86.8 | 168.0±76.0 | 175±120 | 169.0±84.0 | 173.2±86.1 | 0.527 | ||||||

| Variable | Adjusted OR | CI95% | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (L) <80% predicted* | |||

| Hospital management during COVID-19 | 4.97 | 1.95-38.63 | 0.047 |

| Low level of physical activity | 3.85 | 1.10-12.50 | 0.039 |

| High waist-to-hip ratio | 1.65 | 1.53-22.34 | 0.040 |

| No prior or incomplete vaccination against COVID-19 | 4.21 | 1.88-18.75 | 0.044 |

| Pseudo R2 = 0.4026. Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi2 170.57 (p=<0.001). AUC= 0.892 | |||

| PEF (L/s) <80% predicted* | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 7.55 | 1.93-61.02 | 0.048 |

| Female gender | 6.91 | 1.44-33.01 | 0.015 |

| Health insurance: Subsidized | 3.53 | 1.12-11.16 | 0.031 |

| Pseudo R2 = 0.2646. Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi2 111.00 (p=<0.001). AUC= 0.848 | |||

| Variable | Adjusted OR | CI95% | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 5.99 | 1.81-19.75 | 0.003 |

| Age > 65 years | 8.77 | 5.81-20.60 | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 3.56 | 1.43-8.85 | 0.006 |

| Low level of physical activity | 2.86 | 1.97-8.42 | 0.046 |

| Decreased handgrip strength | 1.06 | 1.03-1.12 | 0.045 |

| FEV1 (L) <80% | 2.33 | 1.14-4.76 | 0.022 |

| Body Mass Index >30 kg/m2 | 2.78 | 1.09-7.11 | 0.032 |

| Pseudo R2 = 0.407. Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi2 147.83 (p=0.973). AUC= 0.902 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).