1. Introduction

In late 2019, a new virus emerged in China and spread all over the world, causing a pandemic that has since been termed ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ (COVID-19) and the virus is termed the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Being a new and hitherto unknown virus, its initial identification, symptomology, and pathogenesis took many months, leading to the loss of more than 7 million lives.1 Worldwide, governments responded with policy changes to protect their people and maintain economic stability amid the confusion and lack of adequate information.2 It has also resulted in a radical shift in individuals’ everyday habits, emphasizing public health precautions such as “extensive hygiene protocol (e.g., regular washing of hands, avoidance of face-to-face interaction, etc.), social distancing, and wearing protective masks.”3 Patients of COVID-19 have a wide range of symptoms, including fever and fatigue and others involving the respiratory, gastrointestinal and neurological systems.4 After the exposure, people develop the illness 2 to 14 days (about two weeks) later, and the wide variability in length and symptomology (asymptomatic pneumonia to multiorgan failure) made diagnosis difficult until the development of specific tests. 5–7 Many symptoms suggest “central nervous system (CNS) involvement, like taste and smell impairment, headache and dizziness, and nerve pain.” 8 Most cases of COVID-19 resolve in 1 or 2 weeks.9 Given the spectrum of disease severity, recovery time can vary, including the resolution of symptoms and the ability to return to their regular lives.10

With the initial viral type causing the worldwide pandemic, new variants with genetic changes appeared with increased infectivity and the ability to bypass vaccine protection, leading to a new class of patients appearing in hospitals. These were people who had recovered from the viral attack (no detectable virus in the body) but continued to suffer from unexplained residual or new symptoms months later. Patients had many symptoms, including “myalgia, dyspnea, abnormal chest imaging and pulmonary function tests, and cardiovascular issues.”11 Most initial cases involved older patients or those with co-morbidities, who were not well-documented or considered insignificant due to their age, ethnicity, or sex. Therefore, their symptoms were deemed psychological or imaginary.11 Over time, persistent symptoms began to be seen in younger patients or those with no co-morbidities, leading to critical evaluation of patients and their symptoms.

Most infectious diseases have no symptoms or pathology once the pathogen is cleared in the human body after an infection. Thus, when routine lab tests are negative, but patients still report symptoms, clinicians may deem them psychological, upsetting patients.12 Evidently, some post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection patients develop a wide range of persistent symptoms that do not resolve over many months.10,13 These patients are now diagnosed with “Long-haul COVID-19, Long COVID-19, or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC)”.14,15 As the study of pulmonary, cardiac, and neural complications of Long COVID-19 (LC-19) continues, the long-term morbidity remains unclear. Anecdotally, in some cases, a threshold antigen level causes an exaggerated adaptive immune response that becomes evident several days post-exposure and remains long after the initial acute disease.16 Considering the vast number of infected cases, LC-19-associated functional deficits, albeit in a small proportion of the population, represent a significant burden with severe economic implications on a national, societal, and personal level.

Purpose of the Analysis

The significance of any concept hinges on numerous factors within its field and beyond and, therefore, is constantly evolving. Hence, analysis is needed for concepts without precise definitions and characterizations to support their validity within a field. The need for a concept analysis of LC-19 is of utmost importance as the term has been subjective and poorly defined, leading to ambiguity in its use in diagnosis and healthcare systems. Diagnosis of LC-19 involves a complete assessment of presented symptoms and excluding other conditions or causes, as there are currently no standard regulations for uniformity.17 However, due to the variability of LC-19, including clinical presentation, timeline, and reactivation of latent viruses, diagnosis guidelines are challenging to healthcare personnel. The World Health Organization, using a three-round Delphi consensus method involving patients and clinicians, helped provide a case definition for long COVID and an agreement on symptoms of LC-19.18 Although this study helped resolve some of the unknowns around presentation and symptomology, a continued discussion will support future research and management of LC-19 patients. The variability in onset time, lack of clinical symptoms exclusive to the condition, and absence of identified biological characteristics have resulted in underestimating the number of cases.19

Therefore, continual efforts to create a clear definition and establish the LC-19 condition as a concept are needed to advocate for improved strategies for patients and healthcare personnel. As recommended by Berger et al., “collecting comprehensive, public, transparent, patient-centered, and multidomain clinical and epidemiological data” will be a crucial agenda worldwide to aid in these efforts.20 We use the Walker-Avant method of concept analysis to provide progress toward defining LC-19.21 By exploring the concept of LC-19 through this method, a relevant and functional definition of the term will evolve, and the impact of this concept may be recognized as it applies to healthcare.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The Walker and Avant method of concept analysis was used to define and distinguish the term LC-19 to understand and delineate it from other similar terms.21 The Walker and Avant eight-step process is a classic method used to analyze, clarify, and establish a challenging and complicated phenomenon as a concept. It includes the following steps: (1) selecting a concept; (2) determining the aim of analysis; (3) identifying all possible uses of the concept; (4) determining concept-defining attributes; (5) identifying a model case; (6) identifying a borderline case; (7) identifying antecedents and consequences of the concept; and (8) defining empirical referents of the concept. This analysis aims to understand this hitherto abstract multifaceted concept and use empirical, data-driven, health-based attributes and definitions. This paper works to systematically and logically develop the parameters and boundaries to understand the term and further study the relationships between its properties. These will help establish guidelines to aid physicians, caregivers, and other healthcare personnel. During this process, we will deconstruct the term, define it, and examine the main elements/components better to understand its application and pertinence in nursing practice.

2.2. Data Sources and Analysis

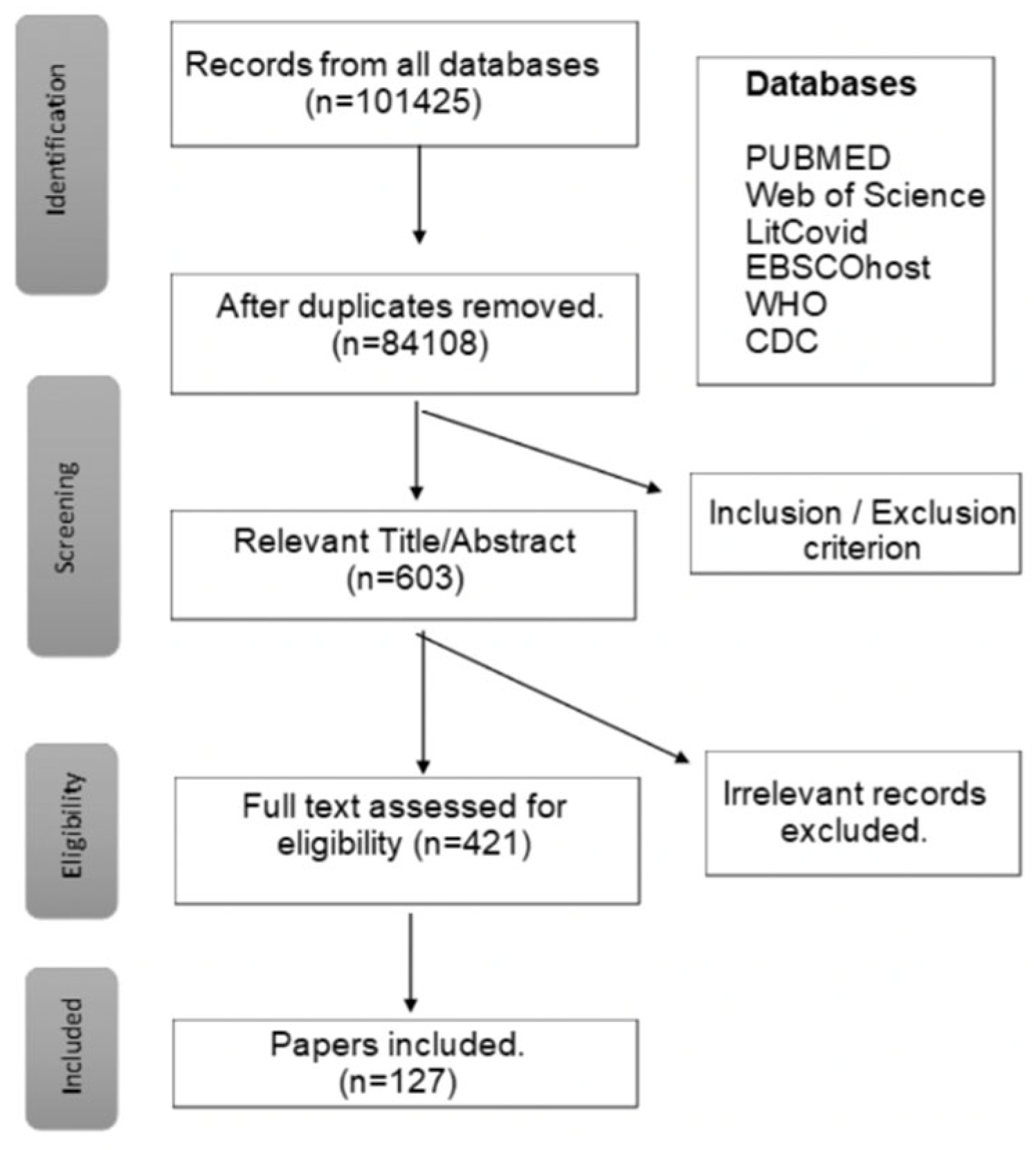

Comprehensive literature searches for the term were performed in dictionaries and online at the websites of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), and the NCBI website PubMed. Search terms used were Long COVID-19, PACS, Long-haul COVID, Post viral syndromes and prolonged COVID in the titles and abstracts. After removing duplicates, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, including full-text articles published in English, only adults, and dates between January 2021 and March 2024 to identify publications relevant to the stated purpose of the analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews, PRISMA-ScR [

22].

3. Results

Papers were identified, screened, and included in the study based on criteria presented in the flow diagram in (

Table 1). The final 127 articles were reviewed and analyzed to assess the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the LC-19 concept.

3.1. Dictionary Definitions of Long-COVID-19

The semantic meaning of the individual words in the term was assessed to aid in defining the meaning of the LC-19 concept. The terms comprising LC-19 were examined separately and together in several sources. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) definitions of “Long” include “longitude as the greatest dimension of an object, to have a yearning desire or strong wish for something, to summon or send for (obsolete), to be a member or affiliate of a particular group or category (obsolete), and senses relating to duration (for example, a long time) [

23].” As a suffix, it means “forming adverbs and (rarely) adjectives and prepositions indicating position or situation, for instance, sidelong [

23].” The OED defines COVID-19 as an “acute disease in humans caused by a coronavirus, characterized mainly by fever and cough, and can progress to pneumonia, respiratory and renal failure, blood coagulation abnormalities, and death, especially in the elderly and people with underlying health conditions [

24].” Together, the two words would signify an extended version of acute disease, which is one of the definitions of LC-19.

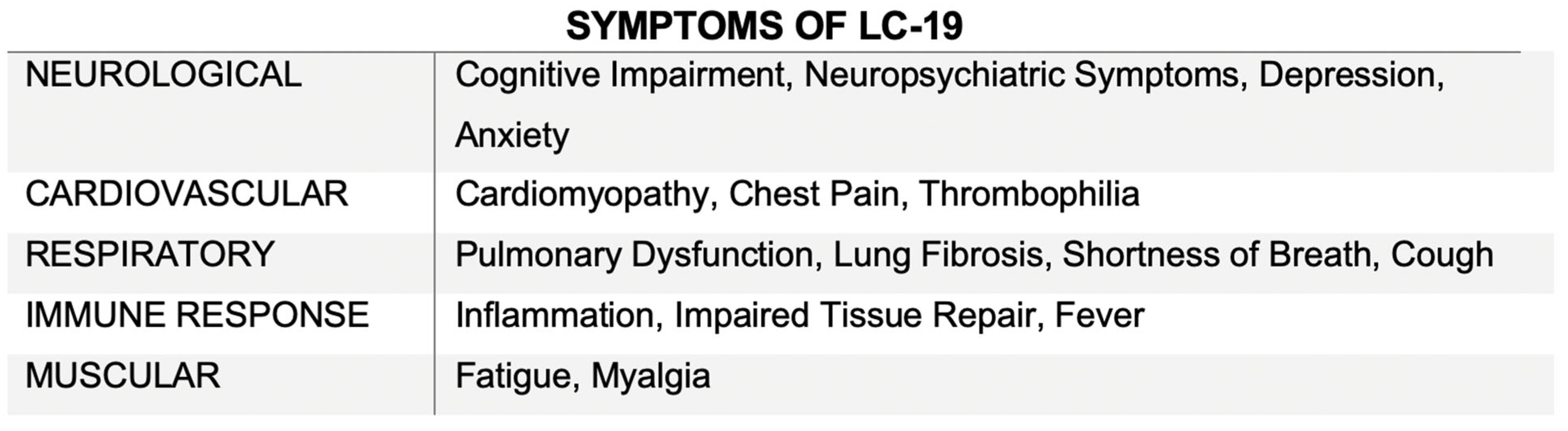

Currently, LC-19 diagnosis includes symptoms that linger or appear after recovery from an initial COVID-19 infection. Therefore, another definition is a medical condition suffered by people who have had COVID-19 and continue to feel the effects up to weeks or months, involving many organ systems after even a mild illness. Symptoms of LC-19 can vary widely and include cough, low-grade fever, fatigue/malaise, chest pain, shortness of breath, headaches, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety/depression, chest/throat pain, and gastrointestinal upset (

Table 2) [

11].

Some variable symptoms in LC-19 may be attributed to the reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, or human-herpes virus 6 [

25]. Furthermore, patients with an LC-19 diagnosis will typically have individual biological factors or co-morbidities that can contribute to long-term health concerns [

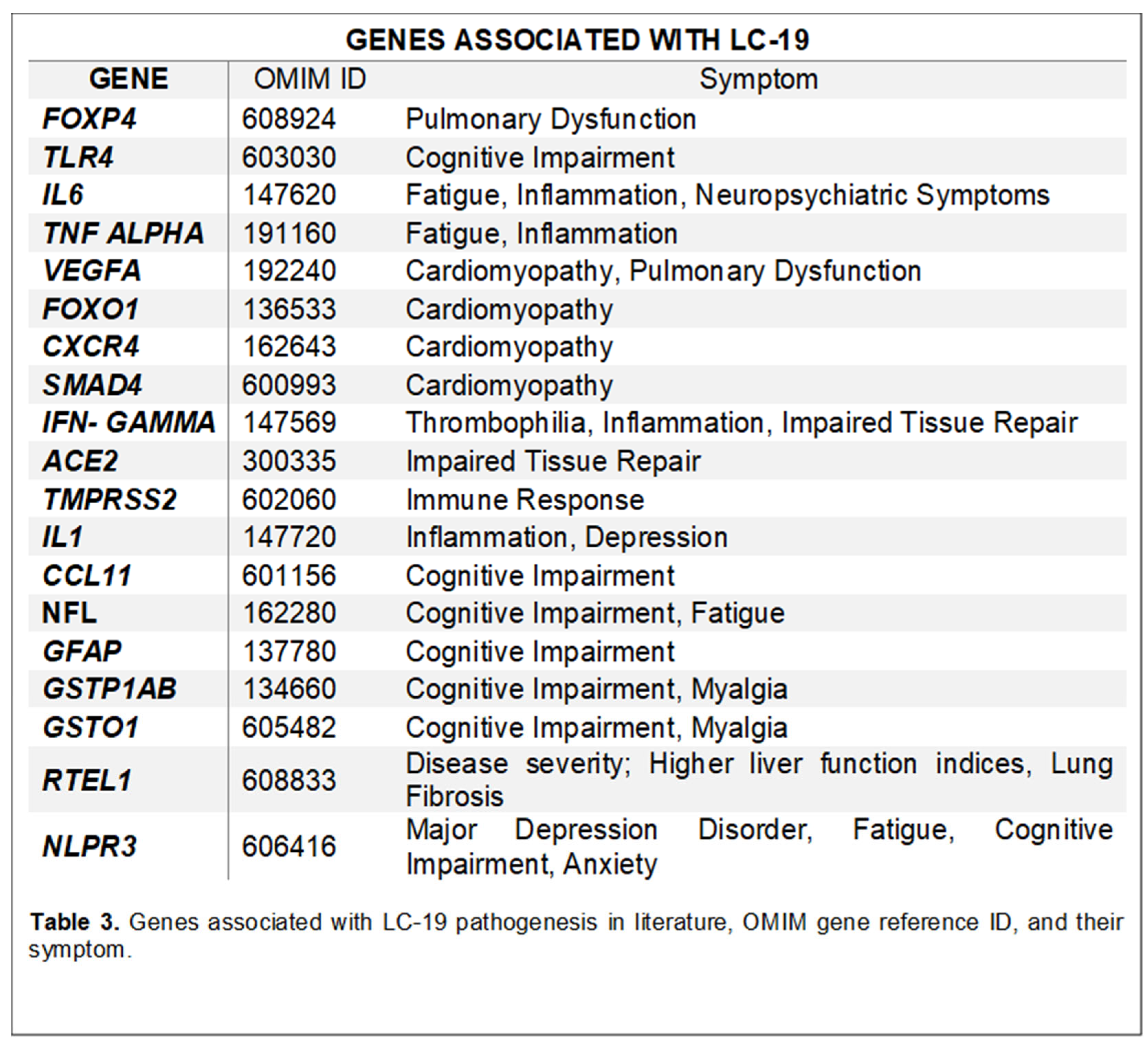

26]. Research has identified some genes associated with LC-19 symptoms to understand the variability of symptoms and begin efforts to define LC-19 (

Table 3).

3.2. Defining Attributes

As the very name indicates, LC-19 is preceded by a positive COVID-19 test or at least an exposure to the virus [

11]. A consensus was achieved regarding LC-19 by defining the most prevalent symptoms as “fatigue, shortness of breath, muscle pain, joint pain, headache, cough, chest pain, altered smell, altered taste, and diarrhea.”[

27,

28] Due to the recentness of the pandemic and its longer

-term sequelae, there is a lack of knowledge about the condition, further baffled by the seeming randomness and unpredictability of the symptoms. Distinguishing attributes of LC-19 span numerous sectors of the patient’s lives and their communities, including impacts of “limitations in health, financial status, social interactions and stigma [

29].” Therefore, this multilayered impact of LC-19 can delay the patient’s path to recovery due to the increased burden associated.

One of the defining attributes of LC-19 is its timeframe, with persistent and new sequelae usually 3 months after a diagnosis of COVID-19 [

18]. Respiratory failure, memory difficulties, kidney injury, mental health diagnoses, chronic fatigue, cough, cardiac and coagulation issues are all currently investigated to diagnose LC-19 [

30]. Eponymously, the condition persists for a prolonged period with changes in the intensity of symptoms, involving numerous, sudden flare-ups of the indications. Due to the recent nature of COVID-19 and, thus, LC-19, there is still insufficient information on the duration of the clinical manifestations and if it will be a lifelong burden to the affected individual health.

A second attribute is the condition’s effect on the patient’s inability to resume his life to pre-infection standards, which may involve the ability to hold a job, leading to financial burdens. A 2022 study reports that as many as a million working-age Americans were too sick to perform their jobs after recovering from COVID-19, working out to about a 2.6 trillion loss due to LC-19 in the US [

31]. Current research indicates that 1 in 5 people between ages 18-64 and 1 in 4 individuals 65 years and above has at least one symptom associated with LC-19 [

32]

A third attribute is the diminished quality of life and social interactions for individuals with LC-19 due to reduced work efficiency, decreased mobility, and continual symptoms [

33]. Additionally, studies indicate that LC-19 impacts the patient both socially and emotionally, including a lack of confidence, uncertainty about the future, and elevated stress. Many individuals battle with fear, loneliness, and helplessness, leading to depression [

34]. This impact is furthered when individuals are forced to go on disability, which adds a burden of shame.

3.3. Model, Borderline and Contrary Cases

As defined within the Walker and Avant guidelines, “a model case presents all the defining attributes of the condition described with a definitive example, a borderline case presents some, but not all, attributes, and a contrary case does not exhibit any of the characteristics of the concept being defined [

21]

3.3.1. Model Case:

A 34-year-old female graduate student living in Paris, France, was diagnosed with COVID-19 in August 2020. She arrived at the university outpatient clinic with a high fever, cough, myalgia, anosmia, and rash, symptoms suspected to be associated with COVID-19. She was discharged, advised to self-quarantine, and received customized care for the management of physical and psychological symptoms. During this period, her symptoms were very severe, but she managed despite a lack of better resources at her disposal at the time. Despite her acute illness, she fully recovered and returned to school and regular activities.

One year later, she suffered from breathlessness when walking, fatigue, persistent fever, myalgia, frequent neurological manifestations including ‘brain fog,’ headache, cognitive impairment, and other symptoms. Therefore, she visited accident and emergency services twice due to increasing concerns about her symptoms. She was diagnosed with persistent tachycardia and shortness of breath. After several investigations, including blood tests, ECG, and chest X-rays, she was discharged home with appropriate directions for care at home. Over the next few weeks, her symptoms’ cumulative effect became so debilitating that she remained bedbound and unable to resume professional work.

Eighteen months after her initial diagnosis, she went on to seek further advice and assessment from her respiratory physician due to concerns about potential persistent bronchial inflammation, disordered breathing, and other neurological symptoms. A follow-up assessment one month later showed no significant improvement in her clinical condition despite regular repeat investigations, at which time she was given a diagnosis of LC-19.

This model case shows all the defining attributes of LC-19, namely pulmonary issues, along with the other cardiovascular or neurological symptoms after a COVID-19 diagnosis. She is suffering on both a physical and an emotional level, making her unable to work and continue her normal routine. LC-19 is completely debilitating her, causing a detrimental effect on her quality of life.

3.3.2. Borderline Case:

Building from an example case within literature, a student (female, age 28, and Caucasian) had unexplained, debilitating symptoms causing her to take leave from school and return home with her parents. Although athletic, she was “unable to perform any physical activity, and even daily functions such as showering would leave her exhausted (post-exertional malaise) [

35].” Tests showed the patient’s vitals within a standard range [BMI: 20.2, BP: 97/51, pulse: 68, RR: 14, Temperature: 36.7 °C], but gastroenterology studies indicated impaired ability to break down easily digestible foods. She was COVID-19 negative and had never tested positive by the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Also, she tested negative for SARS-CoV

-2 through antigen detection by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence for spike and nucleocapsid protein.

Over a period of time in 2022, as her symptoms persisted with increased fatigue and discomfort, she consulted “multiple physicians (urgent care, internal medicine, infectious disease, and family medicine) [

35].” She received a diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) from the last physician utilizing CDC guidelines, which included “profound disabling fatigue for at least 6 months that remained unexplained and was accompanied by frequent sore throats, impaired cognitive function, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, headaches, and joint/muscle pain.” Additional testing ruled out other diseases that could be contributing to her symptoms, such as pneumonia and Epstein-Barr virus.

Due to the unknown cause and expression of ME/CFS and the lack of a diagnostic test, criteria for ME/CFS diagnosis were developed through the consensus of experts. The International Consensus Criteria (ICC) describes ME diagnosis criteria with patients’ symptoms across numerous categories: “post neuroimmune exhaustion, neurological impairment, immune/gastrointestinal/genitourinary impairment, and energy production/transportation impairment [

36] Historically, in diseases lacking a clear etiology and causative agent, criteria to aid diagnoses are defined based on the consensus of clinicians. Although this patient had similar symptoms to LC-19, such as fatigue and gastrointestinal issues, as she did not have a positive COVID-19 exposure, this case would be considered borderline within the LC-19 concept.

3.3.3. Contrary Case:

A contrary case example would be one of severe accidental hypothermia [

37]. In late winter 2016, as outlined in the presented case, a 34-year-old female with a history of drug use and mental health issues was discovered to be missing for seven days before being found, having considerable exposure to sub-zero temperatures. Upon arrival at the hospital, the patient was unresponsive with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 4, severe hypothermic with a rectal temperature of 23°C, heart rate of 30 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 6 breaths per minute, and unmeasurable blood pressure and pulse oxygen saturation [

37]. Cardiologic testing showed no detectable pulse and a dilated heart with a soft ascending aorta. After a heparin infusion, she was rewarmed to normal body temperature at a rate proper to improved survival and minimal neurological risk. To prevent hypothermia-induced coagulopathy, she was administered plasma and anti-coagulants to decrease the risk of post-operative bleeding.

This contrary case indicates that the patient’s condition has none of the defining attributes of LC-19. The case was from a pre-COVID period, and the patient had no symptoms of pulmonary, cardiovascular, or neurological complications generally associated with the condition.

3.4. Antecedents

Antecedents are defined as events that happen before the diagnosis of the condition. In the case of LC-19, the condition is preceded by a COVID-19 infection [

38,

39]. A positive COVID-19 test may not be deemed necessary for an LC-19 diagnosis if the patient suffered symptoms indicative of COVID-19 [

40]. These could be cases where the patient was asymptomatic or did not have access to testing. In previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients, persistent ill health seems to be very common, with ongoing symptoms including breathlessness, cough, fatigue, and mental health problems [

41]. Some “mild” COVID-19 cases remain unresolved with resulting recurrent symptoms, including persistent fatigue and breathlessness, headache, chest heaviness, muscle aches, and palpitations [

13]. Patients may have different underlying biological factors unrelated to COVID-19 etiology but ultimately connected to long-term health consequences.

A diagnosis of LC-19 can lead to the inability to perform normal daily routines and negatively affects the quality of life. The change in quality of life caused by the condition contributes to the consequences of isolation, frustration, restriction of movements, and reduced normal interactions with others in society. Therefore, these factors can also be antecedents to the LC-19 condition. Individuals with pre-existing mental health concerns, such as depression and anxiety, are more susceptible to LC-19 symptoms [

42]. Some risk factors for developing LC-19 may become antecedents, including “belonging to the female sex, belonging to certain ethnic groups (Black Afro-Caribbean, Native American, Middle Eastern or Polynesian mixed ethnicity as compared to white ethnic groups), socioeconomic deprivation, smoking, obesity, certain prescription drugs, and other comorbidities [

26]. Additionally, other antecedents to the condition could arise with continual pathology of LC-19, which might also result from malfunction of the microbiota–gut–brain axis and reactivation of latent viruses, such as Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, or human-herpes virus 6 [

25,

43]

3.5. Consequences

Consequences are the events that follow the concept’s occurrence. Although LC-19 cases are present in a small proportion of COVID-19 cases, the sheer magnitude of the pandemic makes the functional deficits in patients a significant burden. On a national level, the compromised work efficiency has severely affected the economy; societal consequences are caused by the inability to earn a livelihood and dependence on community services. Finally, the isolation and helplessness caused by the disease, with its subsequent impact on mental health and quality of life on a personal scale, is virtually immeasurable [

17]

Many people with LC-19 are unable to hold down their pre-COVID-19 jobs due to impaired health, resulting in a dependency on social services for their most basic needs. This dependency may result in loss of employment and displacement from their homes, ultimately causing shame and humiliation. Such feelings by the head of the family have a trickle-down effect on the rest of the members, inducing helplessness and emotional constriction. Brookings Metro recently published a report assessing the impact of LC-19 as the cause of 15% of labor shortage [

44]. The virus impacts survivors physically but also psychologically, and therefore, after COVID-19, and especially after a diagnosis of LC-19, it is essential to seek treatment for all changes in both body and mind. LC-19 patients report new and worsening mental health symptoms, with depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and insomnia most often reported [

34]

Intense studies on LC-19 and its associated pathogenicity, risk factors, and long-term societal effects have shown interesting and follow-up-worthy results in the consequence of healthcare disparities. The risk of LC-19 subsets varies on the intensity of the initial COVID-19 illness and between the sexes [

43]. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation report, race and ethnicity had a role to play in infections, with non-white patients more affected by COVID-19 and a higher rate of morbidity [

45]. The unequal rates among whites and non-whites of diagnosis and treatment for LC-19 indicate the inequities in the healthcare system [

46]. Whether this numerical discrepancy is real or just a consequence of the reduced availability of resources for testing and diagnosis is unclear.

3.6. Empirical Referents

A concerted effort by the WHO has resulted in developing a consensus definition of LC-19 using the Delphi process. Delphi is a consensus-seeking exercise with an iterative survey involving internal and external experts, patients, and other stakeholders (researchers, external experts, WHO staff, advocacy groups, policymakers, health and disability insurance providers, and media) [

18]. Through collaboration between a panel of experts, the Delphi protocol serves as a communication technique to develop a systemic definition of a concept, including a consensus on variables and values. A detailed questionnaire with 45 items was evaluated in two Delphi process rounds to create a final consensus definition. A clinical case definition was established using pre-defined thresholds and further refined to include values with borderline significance. The wording was adjusted in an iterative process with patients and patient-researchers [

18]

The substantial number of people affected by LC-19 has led to intense scrutiny of this condition and attempts to alleviate the suffering have resulted in LC-19 now being considered a disability under the American Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504, and Section 1557 US-HHS,2021) [

47].

3.7. Definition of the Concept

A clear definition of LC-19 emerged through this concept analysis, addressing several previously existing ambiguities. LC-19 is defined as a condition characterized by symptoms or health issues that persist or newly arise following the acute phase of a COVID-19 infection. These physical symptoms and related disabilities are further compounded by significant mental, psychological, emotional, and social impacts experienced by the individual. Thus, the term LC-19 encompasses the full range of effects resulting from this condition.

4. Impact of the Findings

Knowing the risk of LC-19 features can help plan the availability of relevant healthcare services. Compared to other more generalized post-viral syndromes, the risk of LC-19 correlates to a COVID-19 infection, suggesting a direct cause-effect relationship. This fact may help in developing and tailoring effective treatments against LC-19. Most patients have features of LC-19 in the 3- to 6-month period, and the symptoms in the first three months may help identify those at the most significant risk. One major impact of defining LC-19 as a concept would help reassign social services appropriately according to the need, improve social benefits like unemployment and disability, and coordinate methods of improving the isolation and quality of life of those affected.

A clear definition ensures robust estimates of the incidence and co-occurrence of LC-19 features, their relationship to age, gender, or severity of infection, and the extent to which they are specific to symptomatic and pathological details of COVID-19 [

48]. As recently described in the NICE (National Institute for Health Care and Excellence) guideline on managing the impact of COVID-19, researchers and healthcare workers should focus efforts on understanding the risk factors and their effect on the development of LC-19 [

49]. These analyses would provide comprehensive knowledge of the correlation between pre-existing conditions, co-morbidities, symptoms and progression of LC-19, which can be used to inform healthcare workers to help identify high-risk populations and develop mitigation strategies.

5. Conclusions/Discussion

As outlined in

Table 2, the vast range of symptoms of LC-19 makes diagnosis challenging and frustrating to patients and clinicians. Outlining the method used to define and the actual definition will result in systematic and inclusive criteria to diagnose patients with ongoing symptoms for healthcare personnel. When the LC-19 phenomenon first began, it was easier to distinguish its characteristics due to the isolated nature of COVID-19. However, due to the rapid global spread of the pandemic and the consequent exposure of the majority of the world’s population, distinguishing LC-19 from other diseases has become increasingly difficult. For instance, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) overlaps with LC-19 in terms of complexity, time frame, and some symptomology [

50,

51]. Additional overlap occurs with initial diagnoses of these two conditions being deemed psychological or quickly dismissed. For chronic fatigue syndrome, earlier termed the “Yuppie Flu,” symptoms were typically seen within a younger population and were misconstrued as a means to avoid work/responsibilities. Over time, ME/CFS has been seen to affect a broad array of populations, with a predominance of women being affected over men [

52].

A systemic review study comparing symptoms of LC-19 and ME/CFS suggests many similarities between the two conditions. Analysis of ME/CFS and LC-19 symptoms shows that “out of 29 listed ME/CFS symptoms, all but four were reported by at least one long COVID study,” suggesting numerous similarities between the two conditions regarding clinical presentation and etiologies [

53]. Thus far, LC-19 has proven more legitimate in the medical field than the ambiguous ME/CFS by acknowledging it as a disease and its potential impact.

Establishing a more precise definition of LC-19 is imperative to distinguish it from other latent virus reactivation cases or post-viral syndromes. Several organizations and societies have worked to define LC-19 based on the collection of symptoms, but more consensus is needed. A clear definition of the LC-19 condition will also help advance advocacy and research. However, it is essential to consider the dynamics of this definition as more research emerges, deepening our knowledge of the long-term impact of COVID-19 and LC-19. Community support and media exposure also play a positive role in coping with the effects of LC-19, helping to disseminate knowledge surrounding the condition. Therefore, more efforts must be conducted to define LC-19 as a distinct condition, especially compared to related chronic illnesses. A formal acknowledgment of the condition, its defining attributes, and symptoms will go a long way in legitimizing the diagnosis to reduce the social stigma and barriers to healthcare and social care networks and support.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, formal analysis, S.S. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, S.S., J.B., D.D., D.I., L.G., and L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Clemson University Creative Inquiry program and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM121342 (SC-TRIMH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Clemson University Creative Inquiry program and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM121342 (SC-TRIMH) for funding. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Public Involvement Statement

There was no public involvement in any aspect of this study.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the eight-step model proposed by Walker and Avant [

21].

Use of Artificial Intelligence

“AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript”.

References

- World Health Organization, WHO COVID-19 dashboard, COVID-19 Dashboard (2023).

- International Monetary Fund, International Monetary Fund Policy responses to COVID19., December (2020) 1–189.

- A. Haleem, M. Javaid, R. Vaishya, Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life, Curr Med Res Pract 10 (2020) 78–79. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Larsen, M.R. Martin, J.D. Martin, P. Kuhn, J.B. Hicks, Modeling the Onset of Symptoms of COVID-19, Front Public Health 8 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Di Gennaro, D. Pizzol, C. Marotta, M. Antunes, V. Racalbuto, N. Veronese, L. Smith, Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: A narrative review, Int J Environ Res Public Health 17 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Li, D.Q. Huang, B. Zou, H. Yang, W.Z. Hui, F. Rui, N.T.S. Yee, C. Liu, S.N. Nerurkar, J.C.Y. Kai, M.L.P. Teng, X. Li, H. Zeng, J.A. Borghi, L. Henry, R. Cheung, M.H. Nguyen, Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes, J Med Virol 93 (2021) 1449–1458. [CrossRef]

- S. Tian, Z. Chang, Y. Wang, M. Wu, W. Zhang, G. Zhou, X. Zou, H. Tian, T. Xiao, J. Xing, J. Chen, J. Han, K. Ning, T. Wu, Clinical Characteristics and Reasons for Differences in Duration From Symptom Onset to Release From Quarantine Among Patients With COVID-19 in Liaocheng, China, Front Med (Lausanne) 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. Mao, H. Jin, M. Wang, Y. Hu, S. Chen, Q. He, J. Chang, C. Hong, Y. Zhou, D. Wang, X. Miao, Y. Li, B. Hu, Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China, JAMA Neurol 77 (2020) 683–690. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China, JAMA Intern Med 180 (2020) 1–11.

- Carfi, Barnabei R, Landi F, Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19, JAMA 324 (2020) 603–605.

- V. Daitch, D. Yelin, M. Awwad, G. Guaraldi, J. Milić, C. Mussini, M. Falcone, G. Tiseo, L. Carrozzi, F. Pistelli, M. Nehme, I. Guessous, L. Kaiser, P. Vetter, J. Bordas-Martínez, X. Durà-Miralles, D. Peleato-Catalan, C. Gudiol, I. Shapira-Lichter, D. Abecasis, L. Leibovici, D. Yahav, I. Margalit, Characteristics of long-COVID among older adults: a cross-sectional study, International Journal of Infectious Diseases 125 (2022) 287–293. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Jackson, S. George, S. Hinchey, Medically unexplained physical symptoms, J Gen Intern Med 24 (2009) 540–542. [CrossRef]

- H.E. Davis, G.S. Assaf, L. McCorkell, H. Wei, R.J. Low, Y. Re’em, S. Redfield, J.P. Austin, A. Akrami, Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact, EClinicalMedicine 38 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P.E. Scherer, J.P. Kirwan, C.J. Rosen, Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: A metabolic perspective, Elife 11 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C. Fernández-De-las-peñas, D. Palacios-Ceña, V. Gómez-Mayordomo, M.L. Cuadrado, L.L. Florencio, Defining post-covid symptoms (Post-acute covid, long covid, persistent post-covid): An integrative classification, Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (2021) 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Janeway et al., Immunobiology: The immune system in Health and Disease, 5th edition, Garland Science; 2001, New York: , 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27125/ (accessed July 4, 2024).

- S. Srikanth, J.R. Boulos, T. Dover, L. Boccuto, D. Dean, Identification and diagnosis of long COVID-19: A scoping review, Prog Biophys Mol Biol 182 (2023) 1–7. [CrossRef]

- J.B. Soriano, S. Murthy, J.C. Marshall, P. Relan, J. V. Diaz, A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, Lancet Infect Dis 22 (2022) e102–e107. [CrossRef]

- Y. Su, D. Yuan, D.G. Chen, R.H. Ng, K. Wang, J. Choi, S. Li, S. Hong, R. Zhang, J. Xie, S.A. Kornilov, K. Scherler, A.J. Pavlovitch-Bedzyk, S. Dong, C. Lausted, I. Lee, S. Fallen, C.L. Dai, P. Baloni, B. Smith, V.R. Duvvuri, K.G. Anderson, J. Li, F. Yang, C.J. Duncombe, D.J. McCulloch, C. Rostomily, P. Troisch, J. Zhou, S. Mackay, Q. DeGottardi, D.H. May, R. Taniguchi, R.M. Gittelman, M. Klinger, T.M. Snyder, R. Roper, G. Wojciechowska, K. Murray, R. Edmark, S. Evans, L. Jones, Y. Zhou, L. Rowen, R. Liu, W. Chour, H.A. Algren, W.R. Berrington, J.A. Wallick, R.A. Cochran, M.E. Micikas, T. Wrin, C.J. Petropoulos, H.R. Cole, T.D. Fischer, W. Wei, D.S.B. Hoon, N.D. Price, N. Subramanian, J.A. Hill, J. Hadlock, A.T. Magis, A. Ribas, L.L. Lanier, S.D. Boyd, J.A. Bluestone, H. Chu, L. Hood, R. Gottardo, P.D. Greenberg, M.M. Davis, J.D. Goldman, J.R. Heath, Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae, Cell 185 (2022) 881-895.e20. [CrossRef]

- Z. Berger, V. Altiery De Jesus, S.A. Assoumou, T. Greenhalgh, Long COVID and Health Inequities: The Role of Primary Care, Milbank Quarterly 99 (2021) 519–541. [CrossRef]

- L. Walker, K. Avant, Strategies for theory construction in nursing, 4th ed., 2005.

- A.C. Tricco, E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K.K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, M.D.J. Peters, T. Horsley, L. Weeks, S. Hempel, E.A. Akl, C. Chang, J. McGowan, L. Stewart, L. Hartling, A. Aldcroft, M.G. Wilson, C. Garritty, S. Lewin, C.M. Godfrey, M.T. MacDonald, E. V. Langlois, K. Soares-Weiser, J. Moriarty, T. Clifford, Ö. Tunçalp, S.E. Straus, PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation, Ann Intern Med 169 (2018) 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Oxford English Dictionary, “Long,” (n.d.).

- Oxford English Dictionary, COVID-19, (2024).

- A. Simonnet, I. Engelmann, A.S. Moreau, B. Garcia, S. Six, A. El Kalioubie, L. Robriquet, D. Hober, M. Jourdain, High incidence of Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human-herpes virus-6 reactivations in critically ill patients with COVID-19, Infect Dis Now 51 (2021) 296–299. [CrossRef]

- A. Subramanian, K. Nirantharakumar, S. Hughes, P. Myles, T. Williams, K.M. Gokhale, T. Taverner, J.S. Chandan, K. Brown, N. Simms-Williams, A.D. Shah, M. Singh, F. Kidy, K. Okoth, R. Hotham, N. Bashir, N. Cockburn, S.I. Lee, G.M. Turner, G. V. Gkoutos, O.L. Aiyegbusi, C. McMullan, A.K. Denniston, E. Sapey, J.M. Lord, D.C. Wraith, E. Leggett, C. Iles, T. Marshall, M.J. Price, S. Marwaha, E.H. Davies, L.J. Jackson, K.L. Matthews, J. Camaradou, M. Calvert, S. Haroon, Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults, Nat Med 28 (2022) 1706–1714. [CrossRef]

- S. Lopez-Leon, T. Wegman-Ostrosky, C. Perelman, R. Sepulveda, P.A. Rebolledo, A. Cuapio, S. Villapol, More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Sci Rep 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- O.L. Aiyegbusi, S.E. Hughes, G. Turner, S.C. Rivera, C. McMullan, J.S. Chandan, S. Haroon, G. Price, E.H. Davies, K. Nirantharakumar, E. Sapey, M.J. Calvert, Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: a review, J R Soc Med 114 (2021) 428–442. [CrossRef]

- A. Aghaei, R. Zhang, S. Taylor, C.-C. Tam, C.-H. Yang, X. Li, S. Qiao, Impact of COVID-19 symptoms on social aspects of life among female long haulers: A qualitative study., Res Sq (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. Cohen, S. Ren, K. Heath, M.C. Dasmariñas, K.G. Jubilo, Y. Guo, M. Lipsitch, S.E. Daugherty, Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Retrospective cohort study, The BMJ 376 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cutler, The Costs of Long COVID, JAMA Health Forum 3 (2022). [CrossRef]

- L. Bull-Otterson, S. Baca, S. Saydah, T.K. Boehmer, S. Adjei, S. Gray, A.M. Harris, MMWR, Post–COVID-19 Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years — United States, March 2020–November 2021, n.d. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/117411.

- O. Carlile, A. Briggs, A.D. Henderson, B.F.C. Butler-Cole, J. Tazare, L.A. Tomlinson, M. Marks, M. Jit, L.-Y. Lin, C. Bates, J. Parry, S.C.J. Bacon, I. Dillingham, W.A. Dennison, R.E. Costello, A.J. Walker, W. Hulme, B. Goldacre, A. Mehrkar, B. Mackenna, T.O. Collaborative, E. Herrett, R.M. Eggo, Impact of long COVID on health-related quality-of-life: an OpenSAFELY population cohort study using patient-reported outcome measures (OpenPROMPT), 2024. https://opensafely.org/.

- L.Y. Saltzman, M. Longo, T.C. Hansel, Long-COVID stress symptoms: Mental health, anxiety, depression, or posttraumatic stress., Psychol Trauma (2023). [CrossRef]

- R.K. Straub, C.M. Powers, Chronic fatigue syndrome: A case report highlighting diagnosing and treatment challenges and the possibility of jarisch–herxheimer reactions if high infectious loads are present, Healthcare (Switzerland) 9 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B.M. Carruthers, M.I. Van de Sande, K.L. De Meirleir, N.G. Klimas, G. Broderick, T. Mitchell, D. Staines, A.C.P. Powles, N. Speight, R. Vallings, L. Bateman, B. Baumgarten-Austrheim, D.S. Bell, N. Carlo-Stella, J. Chia, A. Darragh, D. Jo, D. Lewis, A.R. Light, S. Marshall-Gradisbik, I. Mena, J.A. Mikovits, K. Miwa, M. Murovska, M.L. Pall, S. Stevens, Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria, J Intern Med 270 (2011) 327–338. [CrossRef]

- E. Hatam, A. Cameron, D. Petsikas, D. Messenger, I. Ball, A Case of Severe Accidental Hypothermia Successfully Treated with Cardiopulmonary Bypass, Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 1 (2017) 33–36. [CrossRef]

- D. Groff, A. Sun, A.E. Ssentongo, D.M. Ba, N. Parsons, G.R. Poudel, A. Lekoubou, J.S. Oh, J.E. Ericson, P. Ssentongo, V.M. Chinchilli, Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review, JAMA Netw Open 4 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Del Rio, L.F. Collins, P. Malani, Long-term Health Consequences of COVID-19, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 324 (2020) 1723–1724. [CrossRef]

- L. Kompaniyets, ; Lara Bull-Otterson, T.K. Boehmer, S. Baca, P. Alvarez, K. Hong, ; Joy Hsu, A.M. Harris, A. V Gundlapalli, S. Saydah, Post–COVID-19 Symptoms and Conditions Among Children and Adolescents — United States, March 1, 2020–January 31, 2022, 2023. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/Announcement-New-ICD-code-for-.

- F.S.O.M.M.A.P.H. Chopra V, Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19, Ann Intern Med. 174 (2021) 576–578.

- S. Wang, L. Quan, J.E. Chavarro, N. Slopen, L.D. Kubzansky, K.C. Koenen, J.H. Kang, M.G. Weisskopf, W. Branch-Elliman, A.L. Roberts, Associations of Depression, Anxiety, Worry, Perceived Stress, and Loneliness Prior to Infection With Risk of Post-COVID-19 Conditions, JAMA Psychiatry 79 (2022) 1081–1091. [CrossRef]

- J. Choutka, V. Jansari, M. Hornig, A. Iwasaki, Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes, Nat Med 28 (2022) 911–923. [CrossRef]

- Bach K, New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work _ Brookings, (2024).

- Ndugga et al, COVID-19 Cases and Deaths, Vaccinations, and treatments by race ethnicity as of fall 2022, (2022).

- Tanne, Covid-19: US studies show racial and ethnic disparities in long covid, BMJ 380 (2023) 535.

- US-HHS, ADA, Section 504, and Section 1557: Long COVID as a Disability, (2021).

- M. Taquet, Q. Dercon, S. Luciano, J.R. Geddes, M. Husain, P.J. Harrison, Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: A 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19, PLoS Med 18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- NICE 2020, COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 (NG188) Evidence review 5: interventions, 2020.

- K.J. Friedman, M. Murovska, D.F.H. Pheby, P. Zalewski, Opinion our evolving understanding of me/cfs, Medicina (Lithuania) 57 (2021) 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature, Front Med (Lausanne) 10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- N. Thomas, C. Gurvich, K. Huang, P.R. Gooley, C.W. Armstrong, The underlying sex differences in neuroendocrine adaptations relevant to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Front Neuroendocrinol. 66 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wong, Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)-A systemic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology, Medicina (Lithuania) 57 (2021). [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram pathway to filter records from database output for inclusion within this study.

Table 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram pathway to filter records from database output for inclusion within this study.

Table 2.

Common symptoms that can be associated with LC-19.

Table 2.

Common symptoms that can be associated with LC-19.

Table 3.

Genes associated with LC-19 pathogenesis in literature, OMIM gene reference ID, and their symptom.

Table 3.

Genes associated with LC-19 pathogenesis in literature, OMIM gene reference ID, and their symptom.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).