1. Introduction

The astronomical sciences are perhaps the oldest sciences created by man. In addition to the ability to see, observing the stars at night required only a certain intellect as an instrument. Over 15,000-year-old wall paintings in the Lascaux cave already show the constellation of the Pleiades. More systematic observations of the sky led, possibly not coincidentally together with the invention of writing, to the introduction of a calendar in Egypt around 5,000 years ago, which was necessary for planning agriculture. It was not until the 17th century that astronomy and astrology became more separate.

Astromineralogy still exists today not only in the purely scientific version, but also in a version dominated by astrology. Astropharmacy was also a branch of astrology until recently, at least in German-speaking countries [

1]. Even today, astromedicine, also known as astrological medicine, has nothing to do with space medicine, but is intended to help doctors practise medicine using astrological methods.

The relationship between plants and astrology should be explained with astrological botany. In more recent times, astrological biochemistry [

2] was also launched and astrophytomedicine [

3] was invented as a new sub-discipline. All of these areas are subfields of astrology, are therefore outside of the exact sciences and will not be considered further in this article.

Over time, astronomy developed into astrophysics and, with the initial progress of earth-based equipment such as telescopes, spectroscopic methods and new mathematical methods, astrochemistry, astrobiology, astrogeology, astromineralogy and many other astronomical sciences. It is interesting to note that the ideas of researchers, scholars, scientists and intellectuals were usually far ahead of the actual technical possibilities.

For example, the astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1629) described what life on the moon could be like as early as 1609 in his short story “Somnium” (The Dream of the Moon) 360 years before humans set foot on the moon. In this story, among other things, chosen people use the help of spirits and demons to reach the moon in the shadow of a solar eclipse and live there. While high temperatures prevail on the sunny side of the moon, it is very cold on the night side.

This story combines the state of science at the time with purely fictional elements and is probably one of the first serious science fiction novels in literary history [

4].

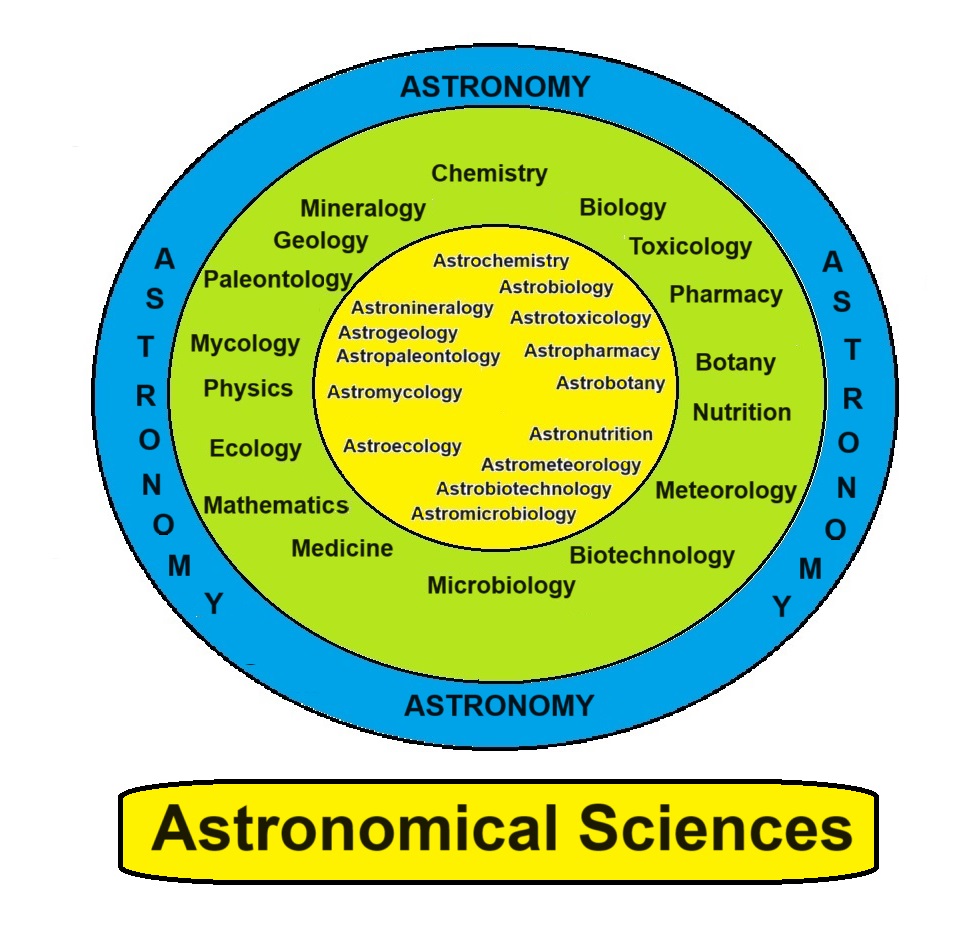

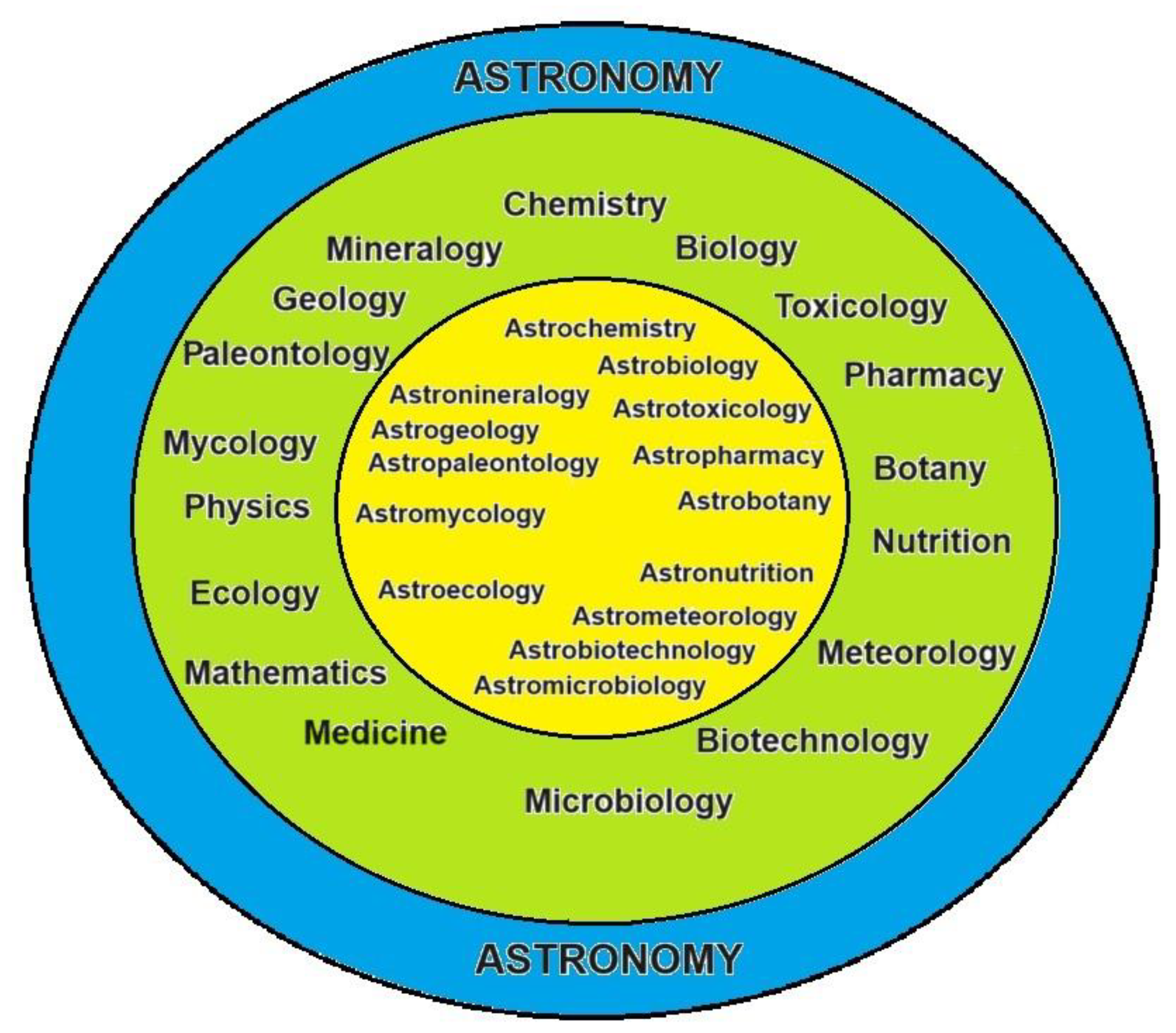

Figure 1.

The astronomical sciences.

Figure 1.

The astronomical sciences.

The outer circle is astronomy as an all-encompassing astronomical science. The deeper you go into the circle, the more specific the science becomes.

2. The Individual Astronomical Sciences

2.1. Astrobiology

Speculations about possible life on alien celestial bodies are ancient and form the intellectual beginnings of astrobiology. The inventor of the telescope Christian Huygens (1620-1695) already considered it possible that the planets could be inhabited by human-like beings with reason [

5]. The philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) even established the law of solar distance, according to which mental abilities would increase with distance from the sun. Accordingly, inhabitants of Jupiter would have been true geniuses [

6].

The term astrobiology was first used in 1935 by the astronomer Ary J. Sternfeld (1905-1980) [

7] and then in 1941 by the philosopher Lawrence J. Lafleur (1907-1966) [

8].

John Bernal (1901-1971) speculated about possible life in the universe in a lecture at the British Interplanetary Society in 1952 and coined the term cosmobiology [

9]. However, the term is rarely used.

In general, exobiology was used in the early days of space travel by Joshua Lederberg (1935-2008) [

10], but was first mentioned by G. G. Simpson in 1949 [

11].

NASA defines exobiology as the “study of the living universe”.

Exobiology attempts to detect life outside the Earth using various strategies

- -

Direct detection and possibly even transportation of a sample to Earth

- -

Detection of certain organic molecules on exoplanets using spectroscopic methods

- -

Detection of signs of extraterrestrial technology or radio signals from a distant civilization.

According to the Drake equation introduced by Frank Drake (1930-2022) [

12], which is a product of several mostly unknown factors, there could be hundreds of civilizations in the Milky Way, but also just one (our own).

Until the 1960s, the term astrobiology was the target of ridicule due to the paucity of data. G. G. Simpson said in 1964 that astrobiology would first have to show that its field of research existed at all [

13].

Astrobiology searches for traces of chemical evolution and evidence of former or extant life in our solar system. Field studies on the origin of life on Earth and the adaptation of life in very hostile places such as Antarctica are also a topic.

The only place in the solar system where life was considered at least theoretically possible outside the Earth is Mars.

The discovery of the polar ice caps and their seasonal changes in the 18th century fired the imagination of astronomers. The observations of Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910) supported the assumption that there were artificially created Martian canals. The astronomer Percival Lowell (1855-1916) in particular speculated intensively about a modern Martian civilization in his 1906 book “Mars and its Canals” [

14]. However, spectroscopic investigations showed that the Martian atmosphere could only contain small amounts of oxygen and water. This left only the existence of lichens and mosses as a possibility, until the photos taken by the first successful Mariner Mars probe in July 1965 shattered this illusion as well.

It is now fairly certain that even microbes have no chance of survival on the surface of Mars. The Wet Chemistry Laboratory of the Phoenix Mars Lander found a remarkably high concentration of 0.5 to 1 % perchlorate salts on the surface of Mars [

15]. This is three to four orders of magnitude more than on the Earth's surface. The perchlorate was presumably formed by the high UV radiation on Mars. As perchlorates are oxidizing agents, they also make bacterial life directly on the surface very unlikely. Model experiments on Earth showed that perchlorates accelerated the cell death of bacteria by a factor of 10 [

16].

In 1996, McKay and colleagues found structures in Martian meteorites that could be interpreted as fossil bacteria [

17]. These interpretations have since been refuted. The low methane concentration measured also speaks against biological processes on Mars [

18] Exoplanets have become a new focus in the search for extraterrestrial life.

In January 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) reached an orbit around the Earth at a distance of 1.5 million km at the so-called outer Lagrange point of the Sun-Earth system and can use infrared measurements to obtain information about the atmospheric composition of exoplanets that was previously impossible. In addition to carbon dioxide and methane, the atmosphere of the exoplanet K2-18b could possibly also contain large quantities of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and dimethyl disulphide (DMDS) [

19]. The latter two substances are possible biosignatures, as they are probably only produced by biological processes. Another research group subjected the collected data to further analyses and found no statistically significant evidence for DMS and DMDS [

20]. Further investigations therefore remain to be carried out.

In the distant future, the colonization of single-celled organisms via space probes on exoplanets that are basically habitable but have not yet been inhabited would be a way of spreading life beyond Earth. This could skip the first billion years that were necessary on Earth to develop the first single-celled organisms [

21]. A journey with today's probe to the next solar system would take the fastest man-made Parker Solar Probe satellite only 7000 years at around 691,000 km/h.

2.2. Astrobiotechnology

Astrobiotechnology is an interdisciplinary field of research that uses biotechnological methods and principles to solve problems in astrobiology and space travel. Central areas of application are the development of biological life support systems such as oxygen production, water treatment and food production, especially for long-term missions. This also includes the recycling of waste materials. In biotechnological experiments, microorganisms, plants or cell cultures are to be examined under the special conditions of space. The development of biotechnological instruments and methods should help to find biomolecules or traces of life in the universe. Another task is to protect other celestial bodies from contamination by terrestrial microorganisms [

22]. There is a particularly large overlap with astro-microbiology. Astrobiotechnology only came into being after the turn of the millennium [

23].

2.3. Astrobotany

Astrobotany deals with the surface and, in particular, plant life on foreign planets. The term was coined by Gavrill Tikhov (1875-1960) when he reported to the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1949 on his years of observations of the surface of Mars [

24]. The low resolution of the telescope images made flora on Mars appear conceivable. Plants in spacecraft will probably become very important as food for astronauts on long-duration space flights. It is not trivial to grow plants without gravity. The supply of light, minerals, water and insects for pollination is another problem. Experiments with plants have been carried out on board the ISS since 2000, and 20 experiments had been conducted by 2010. In 2014, lettuce seeds were activated on nutrient pads, and later the first space lettuce was harvested. In the summer of 2015, the crew of the ISS then ate romaine lettuce produced in space for the first time [

25]. The Chinese lunar probe Change'-4 made the first controlled landing on the far side of the moon. Another milestone was the first germination of plants on a foreign celestial body in the minibiosphere brought along in 2019. After 9 days, these first extraterrestrial plants froze to death in the cold of the lunar night [

26].

2.4. Astrochemistry

Astrochemistry developed as a combination of astronomy and chemistry. The first and most important method of astrochemistry is the analysis of optical spectra. The first spectrum of sunlight was recorded by Issac Newton in 1666. William H. Wollaston (1766-1828) and Joseph Fraunhofer (1787-1826) further developed the spectroscopic methods so that chemical discoveries could be made on celestial bodies by analyzing stellar spectra, which have never been approached before. Lockyer was thus able to spectroscopically discover helium in the sun in 1868 [

27]. Helium was not discovered on Earth until 1895. The proportion of helium in the earth's atmosphere is only 0.000072% by weight, compared to 26% in the sun. The element helium was then named Helios after the Greek name for the sun. On the other hand, Campbell proved in 1910 that there are only small amounts of oxygen and water in the Martian atmosphere, making higher life unlikely [

28]. The term astrochemistry was actually first mentioned in a scientific text in 1921 by the well-known astronomer Henry N. Russel (1877-1957)„ A star is hot mass of gas from core to rim, and the simplest thing in the universe is gas, escpecially hot gas. We have to do with astro-physics only, and not with astro-chemistry, except at the very lower extremity of the scale of stellar temperatures.“ [

29].

Interestingly enough, it is a statement of what astrochemistry is not or cannot be. One year later, Thomas Jaggar stated„“The basic of physical geology resides in hydrogen and the evolution of the elements just as in the case of astronomy. But astronomy its basing all is newer work on astrophysics and astrochemistry. It is frankly pure and does not worry about getting itself applied.“ [

30].

Molecules in interstellar space were identified for the first time in the 1930s. In 1940, the astronomer Rupert Wildt (1905-1976) coined the term cosmochemistry for the first time [

31].

In 2009, the simplest amino acid glycine was found [

32]. In 2010 the large fullerene molecules C

60 and C

70 were detected in a planetary nebula by means of an infrared emission spectrum. According to the intensity of the signals, the total amount should correspond somewhat to the mass of the moon [

33].

In 2012, the sugar molecule glycolaldehyde was detected in the vicinity of the star IRAS 16293-2422, 400 light years away [

34]. It can be assumed that complex organic molecules form even before planets are formed.

In addition to the term astrochemistry, there is also the term cosmochemistry, which was coined by Friedrich Paneth (1887-1958). He was the founder of the Department of Cosmochemistry at the Max Planck Institute in Mainz in 1953, which was closed in 2005. Another field of research in astrochemistry is the simulation of astrochemical processes on Earth. The simulation of the hypothetical early Earth atmosphere by Miller and Urey became particularly well known. Water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen and carbon monoxide were exposed to electrical charges. After some time, organic compounds were formed, including amino acids [

35]. The Miller-Urey experiment showed differences compared to nature. For example, the amino acids were formed in a 1:1 racemate mixture. In nature, the amino acids occur almost exclusively in the L-form. The discrepancy could be explained by naturally occurring minerals as catalysts.

The Miller-Urey experiment is basically already an astrobiological experiment. However, there is one thing that has never been achieved in any of the other experiments carried out in the almost 70 years since then: the artificial synthesis of life from inanimate matter.

2.5. Astroecology

Astroecology deals with the ecological aspects of life in space and on other celestial bodies. It looks at the interaction between potential life forms and their environment on other planets or moons. Astroecology also asks what resources, such as water, minerals and energy sources, are available on a celestial body and how they could be used for life forms. The aim is to gain insights into the possible development and spread of life in the universe and to investigate extraterrestrial ecosystems and develop strategies for the future colonization of other planets, especially Mars. It is also about considering how artificial ecosystems can be created on space missions. Astroecology is the link between classical ecology and astrobiology and can provide important insights for the search for extraterrestrial life [

36]. The term astroecology was coined as early as 1959 in a US Air Force report by Paul A. Campbell (1902-1982) [

37].

2.6. Astrogeology

Astrogeology deals with the geological structure of solid celestial bodies, with the exception of the Earth itself. As early as 1863, the archaeologist Joseph Hekekyan (1807-1875) introduced astrogeology, referring to the ancient application of geology and astronomy to agriculture [

38]. Astrogeological knowledge would also have helped in the construction of the pyramids of Giza to protect them from the annual flooding of the Nile, culminating in the paragraph „Astrogeology governs our mode or thougt. It is the type of all our metaphysical generalizations. It is the cause why the theory of numbers, geometry, chemistry, mineralogy, hydraulic and the great familys of the sciences are better cultivated among us than in rainy countries.“

This kind of astrogeology was therefore still very close to astrology. With the introduction of spectroscopic methods, the improvement of optical telescopes and, above all, the introduction of space travel, astrogeology became an exact science. The sending of space probes and subsequent investigations on foreign celestial bodies, studies of meteorites and analogies of earth geology are further astrogeological methods.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Eugen Shoemaker (1928-1997) invented the basics of planetary mapping. The Finnish geologist Kalervo Rankama (1913-1995) then used the term astrogeology for the first time in a scientific article published on April 1, 1962 [

39]. A year earlier, Shoemaker and Chao had already published a text on the Nördlinger Ries in Bavaria, probably the first serious astrogeological article [

40].

Shoemaker was shortlisted for the NASA astronaut program and became Principal Investigator for the study of lunar rocks. The crew of Apollo 11 received geological training from him in the Nördlinger Ries. Harrison Schmitt (*1935) was the first geologist to set foot on the moon during the final Apollo 17 mission and became the first practical astrogeologist ever. In an article published in 2010, Schmitt also called for further geological expeditions on the moon in order to prepare for future Mars geology. Situated between Earth and the Moon in terms of size, and with a relatively thin atmosphere, Mars should combine the geological conditions of Earth and the Moon [

41].

2.7. Astrometeorology

For a long time, astrometeorology was basically meteorological astrology and aimed to predict the weather with the help of the position and movement of the planets. The term astrometeorology was mentioned as early as 1817 by T. Drummond [

42]. As weather forecasts were vital for sowing and harvesting in ancient societies, scholars were already trying to predict the weather with astronomical observations in ancient Egypt. At that time, it was assumed that the position and movement of celestial bodies influenced the weather. As the starry sky and climate differ in winter and summer, a connection was long suspected. Aristotle and Johannes Kepler also dealt with astrometeorological concepts. However, modern meteorology no longer considers these old astrological ideas to be a valid method of weather forecasting and regards this astrometeorology as a pseudoscience.

For the weather phenomena in the albeit thin atmosphere of Mars the gas giants such as Jupiter and on Saturn´s moon Titan, there is a future need for meteorological research that could possibly turn astrometeorology into an exact science.

2.8. Astromicrobiology

Astromicrobiology is an interdisciplinary field of research that deals with the question of how life arises, develops and is distributed in the universe and is very close to astrobiology. In practice, astromicrobiologists study life on Earth under the most extreme conditions, such as in deserts, hot springs, permafrost or the deep sea. They also look for potential traces of extraterrestrial life, so-called biosignatures, in spectra. The behavior of terrestrial life under simulated conditions on Earth is being investigated, as are experiments on the ISS in orbit. Cabin hygiene and the development of antimicrobial surface coatings also play an important role.

Measures to prevent potential contamination between Earth and other celestial bodies will also be investigated. The participants of the Apollo 11 mission, which transported humans to the surface of the moon for the first time in July 1969, had to be quarantined for three weeks after landing for safety reasons [

43]. However, no germs were brought in from the moon. The term astromicrobiology was first mentioned by name in 1960 by Walter M. Bejuki (1915-2004) [

44].

2.9. Astromineralogy

The beginning of practical astromineralogy dates back to 1794, when Ernst Chladni (1756-1827) thought that ferrous stones falling from the sky were meteorites from outer space [

45]. This theory was revolutionary at the time and it took a long time for it to gain acceptance. In an article from 1817, Chladni almost poetically called the examined stones “matter fallen from heaven” [

46].

Since the founding of the IMA (International Mineralogical Association) in Washington in 1962, the study of minerals in a cosmic environment has become a new systematic astronomical science, which Walter v. Engelhardt (1910-2008) called cosmic mineralogy in 1963 [

47]. As early as 1948, P. P. Solovyev (1901-1993) coined the term astromineralogy in a reference work published only in Russian [

48]. A particular highlight of astromineralogy was the study of lunar rocks. Minerals were found that had previously been unknown on Earth. Among others, armalcolite, named after the three Apollo 11 astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins, pyroxferoite and tranquillityite were discovered [

49]. Later, this mineral was also discovered on Earth. The term astromineralogy only became generally accepted in 1992 [

50].

Determining the chemical composition of the planets in our solar system is already a major challenge. Analyzing extrasolar rock is even more difficult. In 2019, planets with a similar geophysical composition to Earth were indirectly detected near white dwarf stars. Due to the high gravity, heavy elements such as helium should quickly sink into the interior of the stars and no longer be visible. Spectral lines of heavier elements in white dwarfs are presumably impurities originating from rocky planets [

51].

2.10. Astromycology

On Earth, fungi play a unique role in the ecosystem and can be found even in the most extreme environments, such as Antarctica, the walls of nuclear power plants or in salt lakes. It is therefore not surprising that fungi can also be found in the extreme conditions of space. For example, various molds were discovered on board the ISS. With the growing exploration of space, a better knowledge of fungi in space is therefore also necessary, the main motive for creating astromycology. The word astromycology was first mentioned by Paul Stamets in 2005 [

52].

Astromycology must take into account the dangers as well as the potential opportunities for human spaceflight. Fungi are very adaptable. They are also particularly resistant to radioactive radiation and can pose a threat to the health of astronauts. Their metabolism produces products that can also lead to the decomposition of control panels and electronics in the spacecraft. One possible use of mushrooms in space are edible mushrooms, which are rich in proteins and vitamins. The oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus has a particularly short growth time and a favorable ratio of fruiting body to substrate and would therefore be a good candidate as food to accompany astronauts on long journeys [

53].

It is also conceivable to combine the production of food with the decomposition of biological waste or to use fungi to absorb radiation [

54]. The field of astromycology is still in its infancy.

2.11. Astronutrition

Even before anyone had ever been into space, scientists were already thinking about nutrition in orbit and under zero gravity conditions.

Aerospace physician James G. Gaume (1915-1996) is considered a pioneer, who set out his thoughts on nutrition in space operations as early as 1958. By the end of the 1950s, it was already clear that food was best taken along in dried form and mixed with water on board the spaceship. The special circumstances and stresses of space and microgravity lead to a change in nutrition. For example, more calcium, more vitamin D, protein and more energy must be supplied [

55]. Lack of space and resources is a major problem in space travel. Getting 1 kg of material to the ISS costs around

$30,000. Water can be 95% reused in a spacecraft. The situation is completely different for oxygen and food. There are attempts to solve this problem with algae. As early as 1954, John E. Myers suggested that algae could serve as a renewable food and oxygen producer on long journeys, e.g. to Mars. The idea was that 2.3 kg of algae could produce enough oxygen for one person [

56].

2.12. Astropaleontology

While classical palaeontology investigates fossil traces of past life on Earth, astropalaeontology extends this approach to extraterrestrial worlds such as the Moon, Mars or other planets and moons in the solar system.

Clear evidence of past life, e.g. in deeper layers of the Martian crust by a Mars rover, would be a sensation. The same applies to other biological structures that have been preserved in the rocks or sediments of alien planets. Astropaleontology is close to astrobiology, but searches for traces of past life. The methods of astropaleontology are similar to those of terrestrial paleontology, but must be adapted to the particularly extreme conditions and challenges of extraterrestrial environments [

57]. The term astropaleontology was first used in 1977 by John Armitage (1945-2015) [

58].

2.13. Astropharmacy

The term astropharmacy was first mentioned in the scientific literature in 2020 [

59]. When space travel began in the 1960s, space medicine recognized the need to provide astronauts with medication during short space flights and initially drew on the principles of aviation medicine.

In fact, around 60% of space travelers suffer from space sickness and require medical treatment. These complaints are treated with promethazine, usually for just one day. The space sickness then disappears within about 48 hours. Sleeping is difficult, the noise level of the equipment is high and the comforting cuddling with a blanket is no longer possible without gravity. This is why most space travelers take sleeping pills, usually zolpidem and melatonin.

As early as 1994, there were 200 different medicines and medical products on the American space shuttles. The ISS is also equipped for resuscitation measures and operations, and the medical checklist even includes two pregnancy tests [

60].

The use of medicines on the ISS hardly differs from the use of medicines during shorter space stays on space shuttle missions. Space sickness medication and sleeping pills are taken most frequently. In 54% of cases, headaches and musculoskeletal pain have to be treated, mostly with ibuprofen and paracetamol. 55% of astronauts need medication for allergic reactions and nasal congestion.

All long-term pharmacological examinations under microgravity conditions can currently only be carried out during space flights and on the International Space Station (ISS). The cost of a ticket for a ten-day stay there is around 50 million euros. There are therefore only three studies on pharmacokinetics that have been carried out under real space conditions. In one study, five astronauts were each given 325 mg of acetaminophen on three different missions. The uptake of the active substance was increased in the first two days, while after four days the uptake decreased [

61]. Pharmacodynamics in space, i.e. the influence of active substances on the organism under weightlessness conditions, is largely unexplored.

The ABR model (Antiorthostatic Bedrest Model) was developed in order to at least partially investigate the effects of weightlessness. Healthy test subjects lie in a bed that is top-heavy and tilted downwards at an angle of 6 to 12 degrees.

The body fluids shift from the legs towards the upper body and head, similar to a state of weightlessness. During the experiments, all activities such as eating, drinking and washing must be carried out lying down and at least one shoulder must remain in contact with the bed at all times. The test subjects are not allowed to receive visitors in their single room during the study and their correct posture is monitored with a camera [

62].

Studies using the bed rest model are available for the active ingredients ibuprofen, paracetamol (painkillers) and promethazine (motion sickness). The release and absorption of ibuprofen are increased in simulated weightlessness, but no change in elimination or bioavailability was observed. A dose adjustment therefore does not appear to be necessary in space [

63]. The pharmacokinetic properties of promethazine administered orally and intramuscularly were compared. Bioavailability is around 26% higher with oral administration. However, even after more than 60 years of space research, the results of astropharmacology research are still rudimentary. However, it is foreseeable that this will change. At the University of Nottingham, for example, there is now a working group that conducts research solely in the field of astropharmacology.

Among other things, the researchers there aim to develop microsensors to measure physiological function in space, non-invasive control of bone decalcification, clarification of the higher virulence of bacteria, new methods for simulating microgravity or quality assurance of drugs in space [

64]. Until now, the contribution of pharmacists to the health of astronauts has been rather small but it is foreseeable that the rapid development of manned spaceflight will ensure a significant increase in this role [

65].

2.14. Astrotoxicology

Toxicology is already a constant companion of pharmacology and pharmacy on Earth. The same applies to the infinite expanses of space. In contrast to toxicology on Earth, astrotoxicology must take into account the special features of the extreme conditions in terms of gravity, radiation, temperature and pressure in space, especially in the highly complex artificial system of spacecraft and, last but not least, on other celestial bodies [

66]. The first scientific article on space toxicology was published in 1965 [

67]. The term astrotoxicology was not actually mentioned at all in the scientific literature until 2003 by Feo et al. in a subordinate clause [

68].

The fields of activity of astrotoxicology are investigations of the following areas [

69]:

- -

the special toxicological conditions in spaceships

- -

the dangers posed to humans and matter by the increased radiation in space

- -

the special toxicological conditions caused by the extreme space conditions

- -

the influence of low gravity on toxicological properties in the human body

Outside the spaceship, an artificial quasi-earthly oasis created by humans in the middle of a hostile universe, large temperature differences, different gravity, vacuum, but also high pressure, radiation and extreme dryness can lead to the formation of unusual toxicological substances. The lunar dust regolith is activated by high UV and X-ray radiation and very high temperature differences, and led to lunar hay fever during the Apollo 17 mission. The same substance has practically lost its hazard potential under terrestrial conditions.

Presumably due to high UV radiation, a large concentration of perchlorates can be found on the surface of Mars, which could be an additional source of danger for future astronauts [

70]. In addition, the dust particles there are less than 2 micrometers in size and can therefore penetrate the lungs unhindered.

It is also unclear whether the human body reacts differently to toxic compounds under microgravity conditions. To date, no lethal doses LD

50 have been determined in space. However, since 1992 there have been limits for the breathing air in spacecraft (SMACs = Spacecraft Maximum Allowable Concentration) [

71] and the recycled drinking water (SWEGs = Spacecraft Water Exposure Guidelines) [

72] which were introduced by NASA.

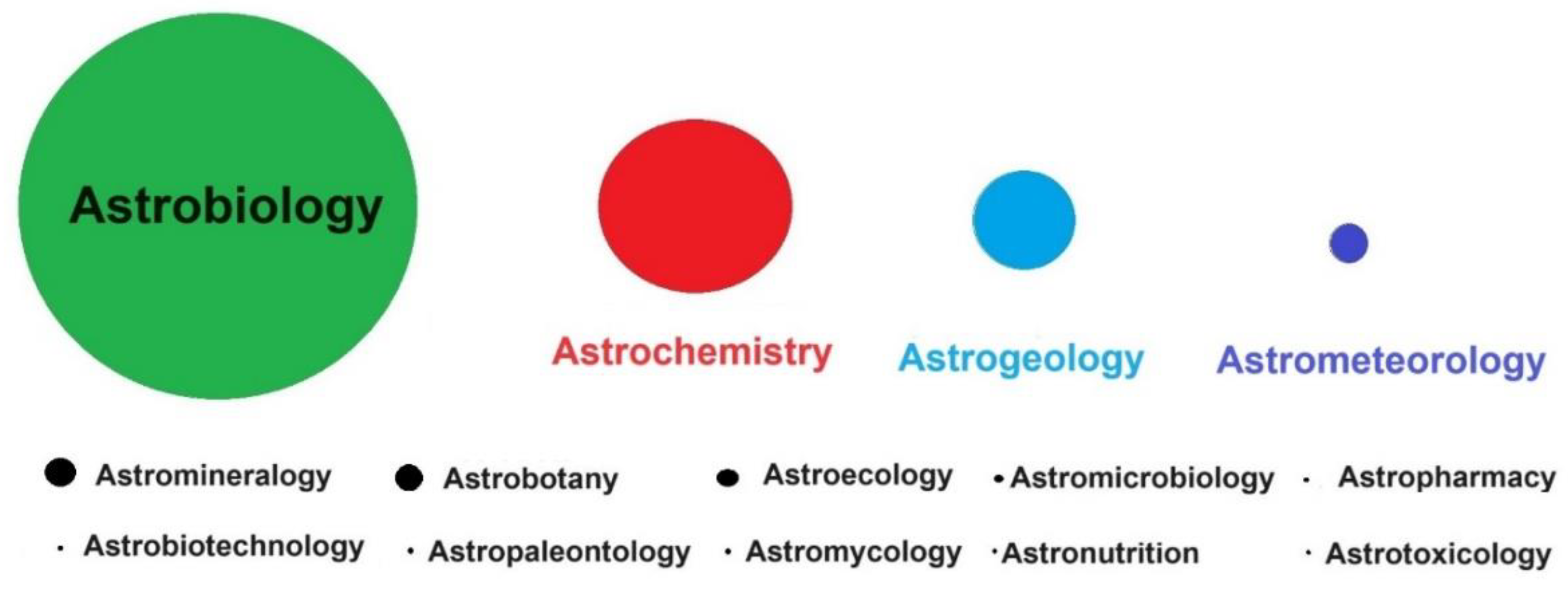

2. Comparison of the Astronomical Sciences

The number of specialist books on astrobiology and astrochemistry is almost impossible to keep track of. There are scientific journals and specialist societies that only deal with these subject areas. It is remarkable that although astrobiology only appeared in the literature in 1935, 72 years after astrogeology was first mentioned, it is much more important than the latter. According to GoogleScholar, of the all about 191,400 articles dealing with astronomical sciences, 76.4% are about astrobiology. Obviously, man's search for extraterrestrial life is much more interesting than studying plate tectonics on a moon of Jupiter. Astrobiology asks the fundamental question of whether extraterrestrial life exists, and ultimately whether we are alone in the universe. The answer to this question is currently a question of faith and therefore quasi-religious. In contrast to religion, it looks as though it could one day be answered through scientific progress. Astrochemistry accounts for a further 19,3% of all astronomical scientific publications. Third position goes to Astrogeology. Astrometeorology has a surprising high Number of Wikipedia articles in eight languages. But these articles deal with the pseudoscience that combines meteorology and astrology. Celestial bodies such as Mars, Jupiter and Saturn´s moon Titan have atmosphere in which weather phenomena could acur a forecase could be necessary in the future. Therefore the exact science of astrometeorology seems to be useful.

Figure 2.

Frequency of the various astronomical sciences on GoogleScholar.

Figure 2.

Frequency of the various astronomical sciences on GoogleScholar.

Table 1.

Astronomical sciences and their auxiliary sciences.

Table 1.

Astronomical sciences and their auxiliary sciences.

| Science |

Helping Sciences |

| Astrobiology |

Biology, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry, Geology, Microbiology |

| Astrobiotechnology |

Biotechnology, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Astrobiology |

| Astrobotany |

Botany, Physics, Biochemistry, Ecology |

| Astrochemistry |

Chemistry, Astronmoy, Physics, Mathematics |

| Astroecology |

Ecology, Astronomy, Biology, Astrobiology |

| Astrogeology |

Geology, Astronomy, Physics |

| Astrometeorology |

Meteorology, Astronomy, Mathematics |

| Astromicrobiology |

Microbiology, Astronomy, Biochemistry, Astrobiology |

| Astromineralogy |

Mineralogy, Astronomy |

| Astromycology |

Mycology, Astronomy, Microbiology, Biology, Biochemistry |

| Astronutrition |

Nutrition Science, Microbiology, Psychology, Medicine |

| Astropaleontology |

Paleontology, Astronomy, Geology, Microbiology, Ecology, Astrobiology |

| Astropharmacy |

Pharmacy, Astronomy, Medicine, Chemistry |

| Astrotoxikology |

Toxicology, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Medicine |

Table 2.

Astronomical sciences in statistical comparison (as of November 9, 2025).

Table 2.

Astronomical sciences in statistical comparison (as of November 9, 2025).

| |

|

Hits in |

|

First |

| |

Number of |

English |

Number of |

mention in |

| |

languages |

Wikipedia |

hits in |

scientific |

| Science |

in Wikipedia |

2024 |

googlescholar |

literature |

| Astrobiology |

90 |

118,586 |

146,000 |

1934 |

| Astrobiotechnology |

|

|

52 |

2002 |

| Astrobotany |

10 |

11,485 |

415 |

1949 |

| Astrochemistry |

50 |

23,200 |

37,000 |

1921 |

| Astroecology |

5 |

1,335 |

246 |

1959 |

| Astrogeology |

33 |

1,759 |

6,120 |

1863 |

| Astrometeorology |

8 |

3,649 |

807 |

1817 |

| Astromicrobiology |

2 |

2,999 |

63 |

1960 |

| Astromineralogy |

|

|

591 |

1948 |

| Astromycology |

|

|

31 |

2005 |

| Astronutrition |

|

|

10 |

1958 |

| Astropaleontology |

|

|

30 |

1977 |

| Astropharmacy |

|

|

74 |

2020 |

| Astrotoxikology |

|

|

7 |

2003 |

Areas such as astrobiotechnology, astropaleontology, astromycology, astronutrition or astrotoxicology have so far been such small sub-areas with so little research intensity that they have literally not been able to make a name for themselves.

Astropharmacy only found its way into the scientific literature in 2020, but has already received a lot of attention in the scientific literature. The expansion of manned space travel could ensure major growth in this branch of science. Astrotoxicology, which is already a neighbor of pharmacy on Earth, could also experience an upswing in its wake.

When considering the astronomical sciences, it may come as a surprise that medicine does not have its own chapter. Astromedicine originated in ancient Babylon over 4000 years ago [

73] and is convinced that there is a connection between the celestial bodies and human health. It is a pseudoscience, as no evidence for the assumptions of astromedicine has been found to date, even though GoogleScholar has 404 publications with the term astromedicine as of December 2024. The medical aspects of space travel are researched in space medicine. It examines the medical effects of microgravity on the human body, the effects of radiation exposure and isolation for astronauts.

Hubertus Strughold (1898-1986) is considered as the father of space medicine and coined the term first [

74]. On February 9, 1949, he founded the world's first institute for space medicine in Texas and did the medical groundwork for the Apollo program. He got many honors for his scientific contribution but a few years after his death documents from the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal linked him to medical experiments in which inmates of Dachau concentration camp were tortured and killed and he lost his honors posthumously [

75].

1. Outlook

Since Gagarin's first space flight in 1961, only 642 people have been in orbit and a further 130 people have been on a suborbital flight at an altitude of at least 100 km, giving them a total of 207 years of space experience (as of December 20th, 2025). In fact, there are currently more Olympic champions, dollar billionaires and Nobel Prize winners than people with space experience. However, it is foreseeable, not least due to the activities of SpaceX, that the number of space travelers will rise sharply in the coming decades and that research in orbit will increase significantly. This will significantly increase the importance of all astronomical sciences. This applies in particular to the life sciences of astrobiology, astropharmacy and astrotoxicology. It can also be assumed that completely new astronomical sciences will emerge. Because of its atmosphere, Earth was previously the only place where aerodynamics played a major role in vehicle construction and aviation. Due to the complete lack of a lunar atmosphere, there was no need for aerodynamic considerations when building the lunar module, for example. On Mars, the atmosphere consists of around 96 % carbon dioxide, 2 % argon and 2 % nitrogen, but the gas pressure is only 6 hPa, which corresponds to the air pressure on Earth at an altitude of 32 km [

76].

The frequent sandstorms there are remarkable. Such a rough but thin atmosphere with relatively low gravity requires astroaerodynamics. Although there is no specialist field of this name as yet, there are practical studies that simulate the conditions for propeller machines in the Martian atmosphere on Earth in special chambers [

77].

However, there is also a broad field for subjects outside the natural sciences in the future, such as astrosociology [

78], astroethnology [

79] or astrocriminology [

80]. In the distant future, an astrosports science could also emerge. This conceivable science is not only concerned with the athletic training required to prevent muscle and bone loss during a long-term mission to Mars [

81].

The future athletes who will one day ski down the carbon dioxide snow of Mt. Olympus on Mars or set unimagined records in the high jump and long throw in a Martian sports hall at only 33% of the Earth's gravity have certainly not yet been born. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to consider how the low gravity on Mars will give sports such as gymnastics and figure skating a new, truly astronomical dimension!

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Astrid Menzel, Patricia and Dr. Thomas Pesel for intensive discussions.

Conflict of interest

I declare having no conflict of interest.

References

- Asboga, F. (Carl Vigelius). Astromedizin, Astropharmazie und Astrodiätetik, Uranus, Leipzig, 1931.

- Dimri M.; Kush, L. Astrological Biochemistry of Vitamines. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2020, 8(1), 82-85. [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, K. Astrophytomedicine: I. Introducing a New Sub-Discipline. Inter. J. Res. Pub. Rev. 2022, 3, 152-157.

- Christianson, G. E. Kepler´s Somnium: science fiction and the Renaissance scientist. Science Fiction Studies 1976, 79-90.

- Hügens, C. Weltbeschauer, oder vernünftige Muthmaßungen, daß die Planeten nicht weniger geschmükt und bewohnt seyn, als unsere Erde. Orell, Geßner und Company, 1767.

- Kant, I. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels, Edition Reprint 1890, Norderstedt, 2017.

- Sternfeld, A. Sur les trajectoires permettant d´approcher d´un corps attractifs central à partir d´une orbite Keplérienne donnée. C. R. Acad. Sci. 1934, 198, 711-713.

- Lafleur, L. J. Astrobiology. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflats 1941, 143, 333.

- Lemarchand, G. A New Era in the Search for Life in the Universes. Bioastronomy 2000, 99, 213.

- Lederberg, J. Exobiology: Approaches to Life beyond the Earth. Science 1960, 132, 3424, 393-400. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G. G.; Simpson, L. The meaning of evolution: a study of the history of life and of its significance for man. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1949.

- Drake, F. Project Ozma. Phys. Today 1961, 14 (4), 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G. G. The Nonprevalence of Humanoids. Science 1964, 3608, 769-775. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A. R. Is Mars habitable?: A critical examination of Professor Percival Lowell´s book Mars and ist canals, with an alternative explanation. Macmillan, London, 1907.

- Hecht, M. H.; Kounaves, S. P.; Quinn, R. C.; West, S. J.; Young, S. M. M.; Ming, D. W.; Catling, D. C.; Clark, B. C.; Boynton, W. V.; Hoffman, J.; DeFlores, L. P.; Gospodinova, K.;, Kapit, J.; Smith, P. H. Detection of Perchlorate and the Soluble Chemistry of Martian Soil at the Phoenix Lander Site. Science 2009, 5936, 64-67. [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, J.; Cockell, C. S. Perchlorates on Mars enhace the bacteriocidal effects of UV light. Sci. Rep. 2017, 4662. [CrossRef]

- McKay, D. S.; Gibson, E. K.; Thomas-Keprta, K. L.; Vali, H., Romanek, C. S.; Clemett, S. J.; Chillier, X. D. F.; Maechling, C. R.; Zare, R. N. Search for Past Life on Mars: Possible Relic Biogenic Activity in Martian Meteorite ALH84001. Science 1996, 272, 5277, 924-930. [CrossRef]

- Webster. C. R.; et al. Low Upper Limit to Methane Abundance on Mars. Science 2013, 342, 6156, 355-357. [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, N,; Constantinou, S.; Holmberg, M.; Sakar, S.; Piette, A. A. A.; Moses, J. I. New Constraints on DMS and DMDS in the Atmosphere of K2-18b from JWST MIRI. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 983(2), L40. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S. P.; MacDonald, R. J.;Tsai, S. M.; Radica, M.; Wang, L. C.; Ahrer, E. M. A Comprehensive Reanalysis of K2-18b´s JWST NIRISS+ NITSpec Transmission Spectrum 2025. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.18477. [CrossRef]

- C. Gros, C. Developing ecospheres on transiently habitable planets: the genesis project. Astrophys Space Sci. 2016, 361, 324. [CrossRef]

- NASA. https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/nai/annual-reports/2004/ciw/astrobiotechnology/index.html.

- Steele, A.; Toporski, J. Astrobiotechnology. Exo-Astrobiology 2002, 518, 235-238.

- Tikhov, G. A. Astrobotany, Ala-Ata. Acad. Sci. Kazakh SSR 1949.

- Kluger, J. Why Salad in Space Matters. Time, 10 August 2015. https://time.com/3991352/lettuce-space-station.

- Castelvecchi, D.; Tatalović, M. Plant sprouts on the Moon for first time ever. Nature News 19. Jan. 2019.

- Lockyer, J. N. The Story of Helium. Nature 1896, 53, 342-346. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. W. On the Spectrum of Mars as photographed with high Dispersion. Science 1910, 21, 808, 990-992. [CrossRef]

- Russel, H. N. Stellar Evolution. Popular Astronomy 1921, 29, 541-545.

- Jaggar, T.A. A plea for geophysical and geochemical observatories. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 1922, 12, 343-353. www.jstor.org/stable/24532665.

- Wildt, R. Cosmochemistry, Scientia 1940, 34, 67, 85-90.

- Elsila, J. E.; Glavin, D. P.; Dworkin, J. P. Cometary glycine detected in samples returned by Stardust. Meteorit. Planet.2009. [CrossRef]

- Cami, J.; Bernard-Salas, J.; Peeters, E.; Malek, S. E. Detection of C60 and C70 in a young planetary nebula. 2010 Science, 329, 5996, 1180-1182. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, J. K.,;Favre, C.; Bisschop, S. E.; Bourke, T. L.; van Dishoeck, E. F.; Schmalzl, M. Detection of the simplest Sugar, Glycolaldehyd, in a solar-type Protostra with alma. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2012, 757, 50-54. [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. L.; Urey, H. C. Organic Compound Synthesis on the Primitive Earth. Science 1959, 130, 3370, 245-251. [CrossRef]

- Meurer, J. C.; Haqq, J.; de Souza Mendonça Jr. M. Astroecology: bridging the gap between ecology and astrobiology, Int. J. Astrobiol. 2024, 23, e3. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P. A. The Present Space Medicine Effort at the School of Aviation. United States Armed Forces Medical Journal 1959, 10(4), 392.397.

- Hekekyan, J. A Treatise on the Chronology of Siriadic Monuments, Demonstrating that the Egyptian Dynasties of Manetho are Records of Astrological Nile Observations which Have Been Continued to the Present Time, Privately printed, 1863.

- Rankama, K. Planetology and Geology. GSA Bulletin 1962, 73 (4), 519-520. [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, E. M.; Chao, E.C. T. New evidence for the impact of the Ries Basin, Bavaria, Germany. J. Geophys. Res. 1961, 66, 3371-3378. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, H. H. Apollo on Mars: Geologists Must Explore the Red Planet. J. Cosmol. 2010, 12, 3506-3516.

- Drummond, T. On astro-atmospherical science. The Philosophical Magazine 1817, 49 (226), 132-138. [CrossRef]

- NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/history/55-years-ago-apollo-11-astronauts-end-quarantine-feted-from-coast-to-coast.

- Bejuki, W. M. The microbiological challenge in space. In Departments in Industrial Microbiology: Volume 1 Proceedings of the Sixteenth General Meeting of the Society for Industrial Microbiology Held at State College, Pennsylvania, August 30- September 3, 1959 (pp. 45-55). Boston, MA:Springer US.

- Chladni, E. F. F. Über den Ursprung der von Pallas gefundenen und anderer Eisenmassen und über einige damit in Verbindungen stehenden Naturerscheinungen, Wittenberg, 1794.

- Chladni, R. F. F. Über einige vom Himmel gefallene Materien, die von den gewöhnlichen Meteorsteinen verschieden sind. Ann. Phys. 1817, 55, 249-276. [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, W. Tübinger Universitätsreden Nr. 16. Probleme der kosmischen Mineralogie,J. C. B. Mohr, Tübingen, 1963.

- Solovyev, P. P. Handbook of Mineralogy, 1948.

- Ramdohr, P.; Goresy, A. E. Opaque Minerals of the Lunar Rocks and Dust from Mare Tranquillitatis. Science 1970, 167, 615-618. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.; Humecki, H. J.; Germani, M. S.; Henning, T. Astromineralogy. Lect. Notes Phys. 1992, 394, p.643, Springer, Berlin.

- Doyle, A.; Young, E. D.; Klein, B.; Zuckerman, B.; Schlichting, H. E. Oxygen fugacities of extrasolar rocks: Evidence for an Earth-like geochemistry of exoplanets. Science 2019, 366, 6463, 356-359. [CrossRef]

- Stamets, P. Mycelium running: how mushrooms can help save the world. Ten speed press, 2005.

- Sanchez, C. Cultivation of Pleurotus Ostreatus and Other Edible Mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85 (5), 1321-1337. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. J.;Prasad, A. N.; Raad, R. R.; Putman, E. J.; Harrington, A. D.; Hynek, B. M. Potential health impacts, treatments and countermeasures of martian dust on future human space exploration. GeoHealth 2015, 9 (2), e2024GH001213. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Rivera-Osoria, K.; Burgess, A. J.; Kumssa, D. B.; Escriba-Gelonch, M.; Fisk, I.; Hessel. V. Modeling of Space Crop-Based Dishes for Optimal Nutrient Delivery to Astronauts and beyond on Earth. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 4 (1), 104-117. [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. Basic remarks on the use of plants as biological gas exchangers in a closed system. Journal of Aviation Medicine 1954, 23, 407.

- Vale Asari, N.; Staisińska, G.; Cid Fernandes, R.; Gomes, J. M.; Schlickmann, M. Mateus, A.: et al. The evolution of the mass–metallicity realtion in SDSS galaxies uncovered by astropaleontology. Monthly Notice of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 2009, 396(1), L71-L75. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, J. The prospect of astro-palaentology. J. Br. Interplanet. Soc. 1977, 30, 466-469.

- Hung, C.-S. International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) Jamboree integrates material research. MRS Bull. 2020, 45, 170-172. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. S.; Chait, A. NASA/TM-2010-215845/PART2, Portable Diagnostics Technology Assement for Space Missions Part 2: Market Survey, NASA, Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 2010. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/2010001108/downloads/20100011008.pdf.

- Cintron, N. M.; Putcha, L.V. Inflight pharmacokinetics of acetamin in saliva. In Results of Life Science DSOs Conducted Aboard the Space Shuttle1981-1986. NASA, 1987, pp. 19-23.

- Jean-Preau, M. Payés 16000 euros pur rester allongés pendant soixante jours, Le Parisiene 13 decembre 2017. www.leparisien.fr/sciences/payes-16-000-euros-pour-rester-allonges-pendant-soixante-jours-13-12-2017-7449186.php.

- Idkaidek, N.; Arafat, T. Effect of Microgravity on Pharmacokinetics of Ibuprofen in Humans. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 1685-1689. [CrossRef]

- Sawyers, I.; Anderson, C.; Boyd, M. J.; Hessel, V.; Wotring, V.; Williams, P. M.; Toh, L. S. Astropharmacy: Pushing the boundaries of the pharmacists role for sustaineable space exploration. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18 (9), 3612-3621. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Raza, M. A.; Noreen, M.; Iqbal, M. Z.; Raza, S. M. Astropharmacy: Roles of Pharmacist in Space. Innovation Pharm. 2022, 13 (3). [CrossRef]

- Strey K. Astrotoxicology. Preprints 2019, 201960120. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. A. Space toxicology: Low Ambient Pressure Environments and Toxicity – A New Approach to Space Cabin Toxicology. Arch. Environ. Health 1965, 11, 316-322. [CrossRef]

- Feo, J. C.; Castro, M. A.; Alford, S. R.; Aller, A. J. Interaction of Selenium Species with Living Bacterial Cells – A Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrocopy Approach. Contact in Context 2003. Cic.setleague.org/cic/v1i2/ftir_selenium.pdf.

- Strey, K. Ziemlich abgehoben: Astropharmazie und -toxikologie in der Raumfahrt. Chem. Unserer Zeit 2024, 58, 144-155. https://doi.org/ciuz.202300015 also Strey, K. Quite detached - Astropharmacy and Astrotoxicology in Space Flight. ChemistryViews 2024. [CrossRef]

- Davila, A. F.; Willson, D.; Coates, J. D.; McKay, C. P. Perchlorate on Mars: a chemical hazard and a resource for humans. Int. J. Astrobiol. 2013, 12, 321-325. [CrossRef]

- Langford, S. D.; Gazda, D. B.; Macneill, K. Spacecraft Maximum Allowable Concentrations for Human Health and Performance, NASA, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, 2024.

- Langford, S. D.; Gazda, D. B.; Macneill, K. Spacecraft Water Exposure Guidelines, NASA, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/jcs-63414-swegs-rev-a.pdf?emrc=7e9f47.

- Rumor, M. Babylonian Astro-medicine, Quadruplicities and Pliny the Elder. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 2021, 111, 47-76. [CrossRef]

- Strughold, H. O. Space medicine of the next decade as viewed by a physician and psysiologist 1950. https://utmb-ir.tdl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7d569f42-1ac0-41aa-a5e6-bec6ce3588df/content.

- Campbell, M. R.; Harsch, V. A. The controversy of Hubertus Strughold during World War II.. Life and work in the field of space medicine, 1st ed. Hubertus Strughold 2013, 96-118.

- Franz, H. B.; Trainer, M. G.; Malespin, C. A.; Mahaffy, P. R.; Atreya, S. K.; Becker, R. H.; Wong, M. H. Initial SAM calibration gas experimets on Mars: Quadrupole mass spectrometer results and implications. Planet. Space Sci. 2017, 138, 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, B.; Xiang, C.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Fan, W.; Hu, Y. Aerodynamic performance study of propellers for Mars atmospheric environment. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35, 35(12). [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. C. Astrosociology, Spaceflight 1965, 7, 71.

- Finney, B. R. Anthropology and the humanization of Space. Acta Astronaut. 1987, 15(3), 189-194. [CrossRef]

- Lampkin, J. A. Mapping the terrain of an astro-green criminology: A case for extending the green criminologicallens outside of planet earth, Astropolitics 2020, 18, 238-259. [CrossRef]

- DeVirgiliis, L.; Goode, N. J.; McDowell, K. W.; English, K. L.; Novo, R.; Botros, V.M; Ploutz-Snyder, L. L. Spaceflight and sport science: Physiological monitoring and countermeasures for astronaut-athlete on Mars exploration missions. Exp. Physiol. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).