4.1. Foundations of Hilbert’s Ramification Theory

The theory of ramification, developed by David Hilbert in his monumental 1897 report “Zahlbericht,” represents one of the most profound syntheses in algebraic number theory. At its heart lies a simple but revolutionary insight: the behavior of prime numbers in field extensions is not arbitrary but is governed by the symmetries of those extensions. This insight bridges two seemingly disparate worlds: the discrete, arithmetic realm of prime ideals and the continuous, algebraic realm of Galois groups.

4.1.1. The Fundamental Setting

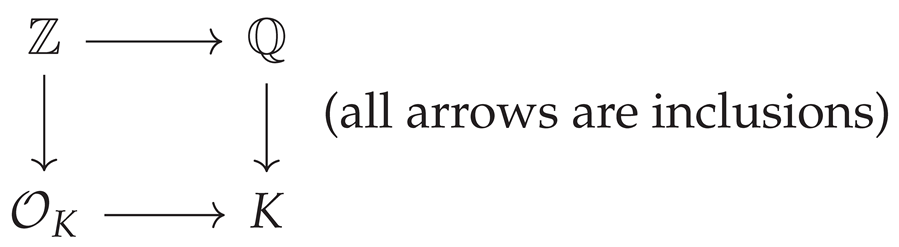

Let K be a number field—a finite extension of —and let denote its ring of integers, consisting of all algebraic integers in K. Consider a finite extension L of K, with ring of integers . Both and are Dedekind domains, meaning that every nonzero ideal factors uniquely into prime ideals. This unique factorization is the arithmetic analogue of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic and forms the bedrock upon which the theory is built.

Given a nonzero prime ideal

in

, the central question of ramification theory is: How does

decompose when extended to

? In other words, what is the factorization of the ideal

in the larger ring? The answer, provided by Dedekind’s theorem, takes the form

where the

are distinct prime ideals of

, and the

are positive integers. From this factorization emerge three fundamental invariants that encode the arithmetic behavior of

in the extension

.

4.1.2. The Three Arithmetic Invariants

The ramification index of over is the exponent with which appears in the factorization. It measures the multiplicity of the prime above . When , we say that is unramified in L; if , it is ramified. Ramification is a genuinely arithmetic phenomenon—a kind of “branching” that has no direct analogue in the theory of field extensions alone.

The

residue field degree is defined as the degree of the extension of residue fields:

Since and are finite fields (the residue fields at and ), measures how much the residue field “expands” when we pass from K to L at the prime in question. A simple but instructive way to view is as the dimension of as a vector space over .

The third invariant, g, is simply the number of distinct prime ideals appearing in the factorization. It tells us how many primes in L lie above . When , we say that is inert (it remains prime in L); when , it splits completely.

These three numbers—, , and g—are not independent. They are bound together by a fundamental relation that reflects the deep interplay between the arithmetic of the extension and its algebraic structure.

4.1.3. The Fundamental Identity

Let

denote the degree of the field extension. Then the invariants satisfy the equation

In the special case where

is a Galois extension, the Galois group

acts transitively on the set

. Consequently, all ramification indices

are equal (denote them by

e) and all residue field degrees

are equal (denote them by

f). The fundamental identity then takes the beautifully symmetric form

This identity is the first great law of ramification theory. It tells us that the degree n, which measures the algebraic complexity of the extension, is partitioned into a product of three arithmetic invariants. In essence, it is a conservation law: the total “amount” of extension (measured by n) is distributed among the three kinds of arithmetic behavior—ramification, residue field extension, and splitting.

To appreciate the identity concretely, consider a quadratic extension of , with d a square-free integer. For an odd prime p not dividing d, the law of quadratic reciprocity determines the decomposition of p:

If d is a quadratic residue modulo p, then p splits: , , .

If d is a nonresidue, then p is inert: , , .

If p divides d (and ), then p ramifies: , , . In every case, .

4.1.4. Two Perspectives on the Proof

The fundamental identity can be proved in several ways, each illuminating a different aspect of the theory. We sketch two particularly instructive approaches.

4.1.4.1 The Arithmetic Approach via Norms

The norm map

sends ideals of

to ideals of

. For a prime ideal

of

lying above

, one has

where

f is the residue field degree of

over

. The norm is multiplicative, so applying it to the factorization

gives

On the other hand, for any ideal of , one can show that . Taking yields . Comparing the two expressions gives , whence .

This proof highlights the role of the norm as a bridge between the arithmetic of L and that of K. It is elegant and concise, but it somewhat conceals the local nature of the phenomenon.

4.1.4.2 The Algebraic Approach via Module Lengths

A more structural proof proceeds by localizing at . Let be the localization of at ; it is a discrete valuation ring. Similarly, set where . The ring B is a finitely generated free A-module of rank . The key object is the quotient , which is an A-module of finite length.

Since as A-modules, we have as vector spaces over the residue field . Hence the length of as an A-module equals n.

On the other hand, by the Chinese remainder theorem,

where

now denote the extensions of the original primes to

B. The length of each summand

can be computed by considering the filtration

The successive quotients are

, each of which is a one-dimensional vector space over

and hence has dimension

over

. Since there are

such quotients, the length of

is

. Additivity of length then gives

This proof reveals the local nature of ramification: the global identity reduces to a statement about modules over a discrete valuation ring. It also introduces the powerful technique of using module length (a kind of “dimension” for modules over local rings) to measure arithmetic invariants.

4.1.5. Toward a Deeper Theory

The fundamental identity is only the beginning. It tells us that the arithmetic of a prime in an extension is controlled by three numbers, but it does not explain why these numbers take the values they do. The next step, which Hilbert took, is to bring Galois theory into the picture. When is Galois, the Galois group acts on the primes above , and this action yields a rich structure.

One defines the

decomposition group

which measures the symmetry of the prime

relative to the extension. Within it lies the

inertia group

which captures the “inertial” symmetries that act trivially on the residue field. Remarkably, the orders of these groups are precisely the invariants we have already met:

Thus, the arithmetic invariants e and f are manifested as the sizes of certain natural subgroups of the Galois group. This connection between group theory and arithmetic is the heart of Hilbert’s ramification theory.

Moreover, when the extension is unramified at (so ), the inertia group is trivial and the decomposition group is isomorphic to the Galois group of the residue field extension. In this case, there is a canonical generator of , the Frobenius element, which raises elements of the residue field to the q-th power (where q is the size of ). The Frobenius element is a central character in modern number theory, linking prime ideals to automorphisms of Galois groups and ultimately to the patterns observed in the distribution of primes.

These ideas—decomposition and inertia groups, the Frobenius element, and the further distinction between tame and wild ramification—form the core of Hilbert’s theory. They will be explored in detail in the next part of this exposition.

4.2. Hilbert’s Main Theorem of Ramification

The fundamental identity tells us how the degree of an extension is distributed among three arithmetic invariants, but it does not explain why a particular prime behaves the way it does. Why does one prime split completely while another remains inert? Why does ramification occur at certain primes and not others? To answer these questions, we must bring the Galois group into play. Hilbert’s great insight was to realize that the arithmetic of prime decomposition is encoded in the structure of the Galois group through certain natural subgroups. This leads us to the main theorem of ramification theory, which establishes a connection between group theory and arithmetic.

4.2.1. The Galois Action on Primes

Let be a finite Galois extension of number fields with Galois group . The group G acts on the ring and, consequently, on the set of prime ideals of . For a prime ideal of and an automorphism , the image is again a prime ideal of . Moreover, if lies above (i.e., ), then also lies above because fixes K pointwise. This action is transitive: given any two primes and above , there exists such that . This transitivity is a key reason why, in a Galois extension, all ramification indices and residue field degrees are equal (we denote them simply by e and f).

The stabilizer of a prime

under this action is called the

decomposition group:

The decomposition group measures the symmetries of

relative to the extension. Its importance stems from the fact that it “controls” the splitting behavior of

in

L. Indeed, the orbit-stabilizer theorem tells us that the number of primes above

is exactly the index of

in

G; that is,

But the decomposition group does more than just count primes. Since every

fixes

as a set, it induces an automorphism of the residue field

. Moreover, because

fixes

K, this induced automorphism fixes the subfield

. Thus we obtain a homomorphism

The kernel of this homomorphism is the

inertia group:

In other words, consists of those automorphisms that act trivially on the residue field. The inertia group captures the “inertial” part of the decomposition group—those symmetries that are invisible at the level of residue fields.

4.2.2. Hilbert’s Main Theorem

The groups and are not arbitrary subgroups of G; their sizes are precisely the arithmetic invariants we introduced earlier. This is the content of Hilbert’s main theorem on ramification.

Theorem 8

(Hilbert). Let be a finite Galois extension of number fields with Galois group , and let be a prime ideal of lying above a prime of . Then:

- 1.

The decomposition group has order , where e is the ramification index and f is the residue field degree of over .

- 2.

The inertia group has order e.

- 3.

-

The quotient is isomorphic to the Galois group of the residue field extension:

In particular, .

4.2.3. Detailed Proof of Hilbert’s Theorem

We now provide a complete proof of Hilbert’s theorem. The proof will proceed in several steps, combining group theory, commutative algebra, and the arithmetic of local fields.

4.2.3.1 Step 1: Transitivity and the order of

Since

G acts transitively on the set of primes above

, the orbit of

has size

g. By the orbit-stabilizer theorem, we have

But

, and by the fundamental identity

. Therefore,

This establishes the first part of the theorem.

4.2.3.2 Step 2: The inertia group and the surjectivity map

Consider the reduction modulo

map

For

, the condition

ensures that

induces an automorphism

of

that fixes

elementwise. This gives a homomorphism

The kernel of

is precisely

, by definition. Thus we have an injective homomorphism

To prove equality, we need to show that is surjective. This is the most subtle part of the proof. We will use a lifting argument based on Hensel’s lemma. First, note that the extension over is separable (since finite fields are perfect).

Now we follow Neukirch’s proof by reduction to the local case. Consider the completions and with respect to the -adic and -adic topologies. We have:

is a finite Galois extension.

There is a natural isomorphism .

The residue fields are unchanged: and .

The inertia group for the local extension corresponds to under this isomorphism.

Let us denote for simplicity:

Then is a Galois extension of complete discrete valuation fields with Galois group , and is the unique prime above .

We now prove that the homomorphism

is surjective. Let

.

Choose a primitive element of the extension . Let be a lift of (note: we are now in the complete local ring). Let be the minimal polynomial of over . Since is Galois, splits completely in .

Let be the reduction of modulo . Then is a root of . Let be the minimal polynomial of over . Since is a finite field (hence perfect), is a simple root of . Moreover, divides .

Now is another root of , hence also a root of . By Hensel’s lemma (applicable because is complete and is a simple root of ), there exists a unique root of such that .

Since is irreducible over and is its splitting field, there exists such that .

We claim that

induces

on the residue field. For any

, write

with

. Lift

h to

. Then

for some

. We have:

Reducing modulo

, and noting that

because

preserves the valuation ring, we obtain:

Thus , proving that is surjective.

Since

is exactly the same as

under the identification of residue fields, we conclude that

is surjective. Therefore

Consequently, .

4.2.3.3 Step 3: The order of the inertia group

From Step 1 we have

, and from Step 2 we have

. Therefore,

This completes the proof of the theorem.

4.2.4. Interpretations and Consequences

Hilbert’s theorem provides a group-theoretic interpretation of ramification and splitting. The inertia group measures the extent of ramification: if is trivial, then and is unramified in L; if is nontrivial, then and we have ramification. Moreover, the size of tells us exactly how much ramification occurs.

The quotient

is isomorphic to the Galois group of a finite extension of finite fields. Such extensions are always cyclic, generated by the Frobenius automorphism

. Therefore, when

is unramified (so

), we have

, and this group is cyclic. In this case, the preimage in

of the Frobenius automorphism is called the

Frobenius element at

, denoted

. It is a crucial actor in number theory, linking prime ideals to elements of the Galois group. The Frobenius element satisfies

When is abelian (i.e., the Galois group is abelian), the Frobenius element depends only on , not on the choice of above , and is denoted . This is the starting point for class field theory and modern reciprocity laws.

Another important consequence of Hilbert’s theorem is the understanding of how primes decompose in intermediate fields. If is an intermediate field, and , then the decomposition and inertia groups of over E are simply the subgroups of and corresponding to the extension under the Galois correspondence. This allows us to relate the splitting of in E to the splitting of in L, providing a powerful tool for studying the decomposition of primes in towers of fields.

4.2.5. An Example: Decomposition and inertia groups in a quadratic extension

Let

be a quadratic extension. Then

is Galois with Galois group

Let p be an odd prime, and let be a prime ideal of lying above p. We distinguish cases according to the factorization of .

Split case. If then the nontrivial automorphism exchanges and . Hence the only element of G fixing is the identity, and therefore Thus , and indeed and . Since , the inertia group is trivial:

Inert case. If is prime, then is the unique prime ideal above p. Consequently every automorphism in G fixes , and hence In this case and , so . Since , the inertia group is again trivial:

Ramified case. If p ramifies in L, equivalently if , then As is the unique prime ideal above p, we again have Here the ramification index is and the residue degree is , so the inertia group has order 2. Since , it follows that Equivalently, the nontrivial automorphism acts trivially on the residue field .

In summary, in both the inert and ramified cases the decomposition group coincides with the full Galois group G, while the inertia group distinguishes the two phenomena: it is trivial in the inert case and equal to G in the ramified case.

4.2.6. Cyclotomic Extensions: A Paradigmatic Example

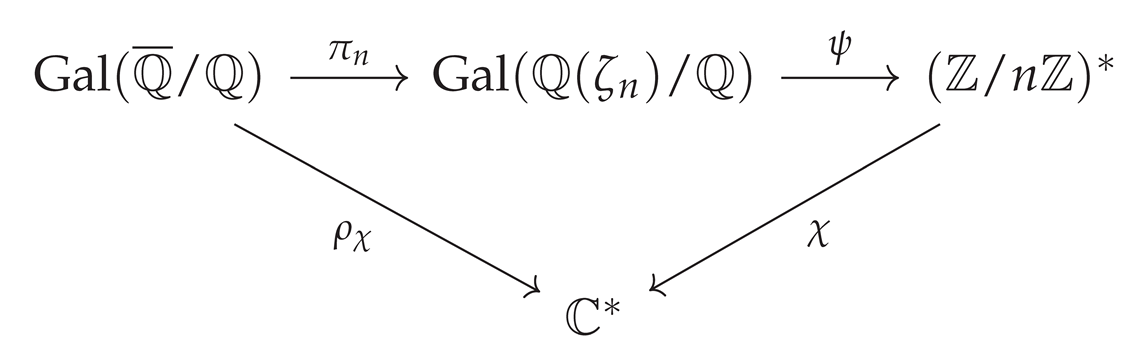

Cyclotomic extensions provide perhaps the most important class of examples in algebraic number theory where Hilbert’s theory can be applied with full precision and yields remarkably complete results. Let m be a positive integer, and consider the cyclotomic field , where is a primitive mth root of unity. The extension is Galois, and its Galois group is canonically isomorphic to , with an element corresponding to the automorphism defined by .

Let p be a rational prime. The decomposition of p in L depends crucially on the relationship between p and m. We distinguish two cases.

Case 1: . In this case p is unramified in L. The residue field degree f is the order of p modulo m, i.e., the smallest positive integer f such that . The number of primes above p is , where is Euler’s totient function, and . The decomposition group for a prime above p is cyclic of order f, generated by the Frobenius element , which corresponds to under the isomorphism . More precisely, is the automorphism . This follows from the fact that modulo , we have , and since both sides are mth roots of unity and , the congruence is actually an equality. The inertia group is trivial.

Case 2: . Write with . In this case, p is ramified in L. Specifically, the ramification index in the extension is , while the residue field degree f is the order of p modulo (i.e., the smallest positive integer f such that ). The number of primes above p is .

To understand the decomposition and inertia groups, consider the tower of fields:

The extension is unramified at p, while the extension is totally ramified at every prime lying above p. Consequently, for a prime of L lying above p, we have:

The inertia group is isomorphic to , and has order .

-

The

decomposition group consists of those automorphisms

for which

is a power of

p modulo

. More precisely, under the isomorphism

, the decomposition group corresponds to the subgroup

Under the natural isomorphism , this subgroup corresponds to , where denotes the cyclic subgroup generated by p in . Its order is .

The quotient is cyclic of order f, and is isomorphic to , where is the residue field of .

To see why p is totally ramified in , consider the minimal polynomial of over , which is the th cyclotomic polynomial . Modulo p, we have , so the only prime above p is , and .

These results illustrate the power of Hilbert’s theorem: the abstract group-theoretic definitions of decomposition and inertia groups match perfectly with explicit computations in cyclotomic fields. Moreover, the Frobenius element emerges naturally as the automorphism raising roots of unity to the pth power, providing a clear arithmetic interpretation of the Galois action.

4.2.7. Wild and Tame Ramification

Hilbert’s theorem tells us that the inertia group has order e, but it does not reveal the full structure of this group. In fact, the inertia group can be further decomposed. When the ramification index e is coprime to the characteristic of the residue field, we say the ramification is tame. In this case, the inertia group is cyclic of order e. However, when e is divisible by the residue characteristic, the ramification is wild, and the inertia group is more complicated—it is a semidirect product of a cyclic group of order prime to the characteristic and a p-group. The study of wild ramification leads to higher ramification groups, which provide a filtration of the inertia group by deeper and deeper “layers” of ramification. This finer structure is essential for understanding the behavior of primes in extensions of fields of positive characteristic, and it also appears in the study of local fields in characteristic zero.

4.2.8. Conclusion

Hilbert’s main theorem of ramification transforms the arithmetic of prime decomposition into a problem in group theory. By associating to each prime the decomposition and inertia groups, we obtain a powerful language for describing how primes split, remain inert, or ramify in a Galois extension. This language is not merely descriptive; it is predictive, allowing us to deduce splitting patterns from the structure of the Galois group and vice versa.

The theorem also lays the foundation for class field theory, where the Frobenius element becomes a key player in the Artin reciprocity law. Moreover, the distinction between tame and wild ramification leads to a rich theory of higher ramification groups, developed by Hilbert and later refined by Hasse, Herbrand.

In the next part, we will explore the Frobenius element in detail and discuss its role in the Chebotarev density theorem, which describes the statistical distribution of splitting types among primes in a Galois extension.

4.3. The Frobenius Element and the Chebotarev Density Theorem

4.3.1. The Arithmetic of Frobenius

The Frobenius element stands as one of the most important concepts in algebraic number theory. Born from Hilbert’s ramification theory, it serves as the critical bridge between the discrete arithmetic of prime ideals and the continuous symmetries of Galois groups. In its essence, the Frobenius element encodes the action of a prime ideal on the Galois group of an extension, transforming the study of prime decomposition into a problem of equidistribution in finite groups.

The Chebotarev density theorem, proved by Nikolai Chebotarev in 1925, generalizes both Dirichlet’s theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions and the prime number theorem for number fields. It states that the Frobenius elements are equidistributed in the Galois group according to the Haar measure. This result not only provides a beautiful and complete description of how primes split in Galois extensions but also lays the foundation for modern reciprocity laws and the Langlands program.

In this part, we shall develop the theory of the Frobenius element with full rigor, prove the Chebotarev density theorem, and explore its far-reaching consequences. We assume familiarity with Hilbert’s main theorem of ramification (8) and the basic theory of Dedekind zeta functions.

4.3.2. The Frobenius Element: Definition and Basic Properties

Let

be a finite Galois extension of number fields with Galois group

. Let

be a prime ideal of

lying above a prime

of

. Assume that

is unramified in

L, i.e., the ramification index

. Then by Hilbert’s theorem, the decomposition group

is isomorphic to the Galois group of the residue field extension:

Since the residue field extension is finite and separable (indeed, finite fields are perfect), it is cyclic. Let be the cardinality of the residue field. The Galois group of a finite extension of finite fields is generated by the Frobenius automorphism.

Definition 6

(Frobenius element).

TheFrobenius element is the unique automorphism corresponding to under the isomorphism . Equivalently, is the unique element of G satisfying

The Frobenius element is a central concept because it attaches to each unramified prime (and a choice of prime above it) an element of the Galois group. When the extension is abelian, i.e., G is abelian, the Frobenius element depends only on , not on the choice of . In this case, we denote it by .

Proposition 1

(Properties of the Frobenius element). Let be a prime above an unramified prime .

- 1.

The Frobenius element has order equal to the residue field degree .

- 2.

For any , we have . Hence the conjugacy class of depends only on .

- 3.

If E is an intermediate field corresponding to a subgroup under the Galois correspondence, then the Frobenius element for in is the image of under the restriction map .

Proof. (1) Since

corresponds to the generator of a cyclic group of order

f, its order is

f. (2) For any

, we have

so

satisfies the defining property of

. (3) This follows from the compatibility of the residue field extensions. □

Thus, to each unramified prime , we associate a conjugacy class consisting of all for primes above . This conjugacy class is the fundamental invariant of in the Galois extension.

4.3.3. The Chebotarev Density Theorem: Statement and Significance

Let be a finite Galois extension of number fields with Galois group . For a prime ideal of K that is unramified in L, choose a prime ideal of L lying above . The Frobenius element is well-defined up to conjugation; its conjugacy class depends only on , not on the choice of . We denote this conjugacy class by .

For a conjugacy class

, define

where

is the absolute norm. Let

be the number of all prime ideals of

K (ramified or unramified) with norm at most

x.

Theorem 9

(Chebotarev Density Theorem).

With the notation above, the natural density of the set of unramified primes of K with Frobenius conjugacy class C exists and equals . That is,

Equivalently, the Dirichlet density of this set is also .

The theorem asserts that the Frobenius elements are equidistributed among the conjugacy classes of G as varies over the unramified primes of K. In particular, for every conjugacy class C, there are infinitely many primes with , and the frequency with which they occur is proportional to the size of C. Every conjugacy class occurs as the Frobenius class for infinitely many primes. This result generalizes Dirichlet’s theorem (which corresponds to the case , ) and the prime number theorem for number fields.

4.3.4. Sketch of the Proof via Artin L-Functions

The proof requires several deep results from class field theory and analytic number theory.

4.3.4.1 Step 1: Reduction to cyclic extensions

We first reduce the problem to the case where G is cyclic. Let be a finite Galois extension of number fields with Galois group . The analytic input required for the proof of Chebotarev’s density theorem is the following statement:

For every non-trivial irreducible character χ of G, the Artin L-function is holomorphic for , admits a meromorphic continuation to , and has no zeros on the line .

Once this statement is known, Chebotarev’s density theorem follows from a standard Tauberian argument. We now explain how this analytic assertion reduces to the case of cyclic extensions.

Brauer induction. By Brauer’s induction theorem, every irreducible character

of

G can be written as a finite

-linear combination

where each

is an elementary subgroup and

is a linear character of

. Recall that an elementary subgroup is a direct product of a

p-group and a cyclic group of order prime to

p.

Artin formalism. Artin’s formalism for

L-functions yields the factorization

where

denotes the Artin

L-function associated with the linear character

of

-

Passage to cyclic extensions. Since

is linear, its kernel

has finite index in

, and the quotient

is a finite cyclic group. Let

Then is a finite cyclic extension. By Artin reciprocity, the Artin L-function coincides with the Hecke L-function attached to the corresponding Hecke character of the cyclic extension .

-

Analytic reduction. Assume the following analytic statement:

For every finite cyclic extension of number fields and every non-trivial Hecke character φ associated with , the Hecke L-function is holomorphic for , admits a meromorphic continuation to , and has no zeros on the line .

Under this assumption, each factor with non-trivial satisfies the required analytic properties. The factors corresponding to trivial linear characters give rise to Dedekind zeta functions of intermediate fields; in the Brauer decomposition of a non-trivial irreducible character , their contributions cancel in such a way that no pole at occurs. Consequently, the Artin L-function satisfies the analytic statement above for every non-trivial irreducible character of G.

Conclusion. Thus the analytic part of Chebotarev’s density theorem for arbitrary finite Galois extensions reduces to the corresponding analytic statement for Hecke L-functions attached to finite cyclic extensions.

Thus, it suffices to prove the theorem for cyclic extensions. From now on, we assume G is cyclic, generated by .

4.3.4.2 Step 2: Analytic properties of Hecke L-functions for cyclic extensions

Having reduced the problem to cyclic extensions via Brauer induction and Artin reciprocity in Step 1, we now establish the crucial analytic fact for Hecke L-functions. This is the central analytic input for the proof of Chebotarëv’s density theorem.

Let be a finite cyclic extension of number fields with Galois group . By class field theory (Artin reciprocity), there is a canonical isomorphism between the character group and the group of finite-order Hecke characters (Größencharaktere) of F with conductor dividing the conductor of . We denote by the Hecke character corresponding to .

For a finite-order Hecke character

, let

denote its conductor. The Hecke

L-function associated to

is defined for

by the Euler product

where the local factors are given by

Here is defined as the value of on a uniformizer at when ; it equals for . For , the character is ramified and the local factor is taken to be 1.

Theorem 10

(Analytic properties of Hecke L-functions for cyclic extensions). Let be a finite cyclic extension, and let ψ be a non-trivial finite-order Hecke character of F associated to this extension via class field theory. Then the L-function satisfies:

- 1.

-

Meromorphic continuation and functional equation: admits a meromorphic continuation to the entire complex plane. Since ψ is non-trivial, is in fact an entire function. Moreover, it satisfies a functional equation of the form

where is the completed L-function, obtained by multiplying by appropriate Γ-factors and a power of the discriminant, and is a complex number of absolute value 1.

- 2.

Non-vanishing on the line :For all , we have . Consequently, is holomorphic and non-zero on the closed half-plane .

Outline of the proof. The proof follows the classical analytic method of Hecke, which generalizes Dirichlet’s approach.

Meromorphic continuation and functional equation: These properties are obtained via the theory of theta series and Mellin transforms, or, in modern language, by Fourier analysis on the adele ring of F. The functional equation follows from Poisson summation.

-

Non-vanishing on the line : Let

. For

, consider

Expanding the Euler product gives

For

, we have

. For

dividing the conductor,

, so these primes contribute only to higher

k where the expression still makes sense. Using orthogonality of characters, the inner sum equals

when

(for unramified

) and is otherwise bounded. Hence,

where

is holomorphic for

.

If some with non-trivial vanished at , then would have a logarithmic singularity there. Choosing g with leads to a contradiction because the left-hand side would tend to as , while the right-hand side is bounded below.

For complete details, see [

19], Chapter VII or [

10], Chapter 5. □

4.3.4.3 Conclusion of the reduction. Theorem 10 provides exactly the analytic statement required at the end of Step 1. By Brauer induction and Artin’s formalism, the Artin L-function for any non-trivial irreducible character of factors into a product of Hecke L-functions attached to cyclic extensions. Theorem 10 guarantees each non-trivial factor is entire and non-zero on , and the trivial factors cancel. Thus is holomorphic and non-zero on , completing the analytic heart of the proof.

4.3.4.4 Step 3: Tauberian argument and conclusion

We now complete the proof of Chebotarev’s density theorem by deducing the asymptotic distribution of prime ideals from the analytic properties of Artin L-functions established in Step 2.

Let be a conjugacy class, and let denote the set of unramified prime ideals of K whose Artin symbol belongs to C. The theorem asserts that has natural density .

Consider the counting function

The key to its asymptotic behaviour is the associated Dirichlet series

which converges absolutely. Using orthogonality of characters, we can express the indicator function of

C as

valid for every unramified prime

. Hence,

For

, the logarithmic derivative of an Artin

L-function can be written as

where

is holomorphic for

(it contains the contributions of ramified primes and higher prime powers

). Consequently,

with

holomorphic for

.

From Step 2 we know the following:

For every non-trivial character , is holomorphic and non-zero on the closed half-plane . Therefore is holomorphic there.

For the trivial character , we have , the Dedekind zeta function of K, which possesses a simple pole at with residue 1. Hence has a simple pole at with residue 1.

Since , the only pole of on the line is a simple pole at with residue . Moreover, the coefficients of are non-negative.

The classical Wiener–Ikehara Tauberian theorem therefore applies to

and yields the asymptotic

A standard partial summation argument (or applying the Tauberian theorem directly to the series

) removes the logarithmic weight and gives

The prime number theorem for the number field

K states that the total number

of prime ideals with norm

satisfies

. Hence,

which is precisely the natural density of the set

. This completes the proof of the Chebotarev density theorem.

4.3.5. Consequences and Applications

The Chebotarev density theorem has a wealth of applications. We now discuss several of the most important ones.

4.3.5.1 1. Dirichlet’s theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions

Let a and m be coprime integers. Consider the cyclotomic extension of with Galois group . For a prime , the Artin symbol corresponds to the element in . Since G is abelian, each conjugacy class is a single element. The Chebotarev density theorem implies that the set of primes p for which equals a given element has natural density . This is precisely Dirichlet’s theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions: for coprime a and m, the set is infinite and has density .

4.3.5.2 2. Prime splitting in Galois extensions

The theorem provides precise asymptotics for the number of primes with a given splitting behavior in a Galois extension. In particular, the primes that split completely in a finite Galois extension are those for which the Artin symbol is the identity. Hence, their density is .

For a quadratic extension , the Galois group has two elements: the identity and the nontrivial automorphism. The Chebotarev density theorem then yields:

The density of primes that split completely (i.e., with ) is .

The density of primes that remain inert (i.e., with ) is also .

The set of ramified primes (where the Artin symbol is not defined) is finite and thus has density zero.

4.3.5.3 3. The Bauer–Neukirch theorem and characterization of extensions

A deep consequence of Chebotarev’s theorem is the Bauer–Neukirch theorem, which states that a finite Galois extension of number fields is essentially determined by the set of primes of K that split completely in L. More precisely, if L and M are two finite Galois extensions of K such that the sets of primes that split completely in L and in M differ by at most a set of density zero, then .

This result is a powerful tool in the study of Galois extensions and plays a crucial role in class field theory, where the abelian extensions of a number field are characterized by the primes that split completely in them.

4.3.5.4 4. The inverse Galois problem and Frobenius fields

The Chebotarev density theorem is an indispensable tool in the study of the inverse Galois problem, which asks whether every finite group occurs as the Galois group of a Galois extension of .

While Chebotarev’s theorem does not construct such extensions, it provides a critical verification tool. Given a candidate polynomial with splitting field L, one can use the theorem to check whether the Frobenius elements at various primes are distributed as expected for the intended Galois group G. More precisely, if one can show that for each conjugacy class C of G, the set of primes p for which the Frobenius at p (interpreted via the factorization of f modulo p) lies in C has density , then this provides strong evidence (and in practice, a proof) that .

4.3.5.5 5. Equidistribution of Frobenius elements and the Sato–Tate conjecture

Chebotarev’s theorem can be viewed as a statement about the equidistribution of Frobenius elements in the Galois group G with respect to the normalized counting measure. This viewpoint leads to far-reaching generalizations in the context of infinite Galois extensions and Galois representations.

A celebrated example is the Sato–Tate conjecture for elliptic curves. For an elliptic curve without complex multiplication, the conjecture predicts a specific distribution for the angles defined by , where . While the full conjecture lies deeper, the Chebotarev density theorem applied to the Galois representations on the Tate module implies a weaker equidistribution result, namely that the Frobenius elements are equidistributed in the ℓ-adic Lie group with respect to the Haar measure.

4.3.5.6 6. Heuristics in number theory

The Chebotarev density theorem serves as the definitive model for probabilistic heuristics in number theory. When faced with a problem about the distribution of number-theoretic objects (e.g., primes, splitting types, orders of elements), one often formulates a “naive” probability based on group theory and then uses Chebotarev’s theorem to justify that this probability is the correct asymptotic density.

Classical examples include:

Artin’s primitive root conjecture: The density of primes for which a given integer a (not a perfect square and ) is a primitive root modulo p is given by an explicit product over primes.

Splitting types of polynomials: Given an irreducible polynomial , the density of primes p for which factors into irreducible factors of specified degrees is equal to the proportion of elements in the Galois group of f with the corresponding cycle type (when the Galois group is viewed as a permutation group on the roots).

Orders of points on elliptic curves: The density of primes p for which the order of the group is divisible by a given integer m can be expressed via Chebotarev’s theorem applied to the division fields .

In each case, the heuristic probability is precisely the density predicted by Chebotarev’s theorem for the relevant Galois extension, making the theorem the bridge between group-theoretic expectation and arithmetic reality.

4.3.6. Conclusion

We have traced the development from Hilbert’s ramification theory to the Frobenius element and finally to the Chebotarev density theorem. This journey illustrates the progressive deepening of our understanding of prime numbers, from their basic properties to their intricate behavior in Galois extensions.

The Frobenius element remains a central object of study, with connections to étale cohomology, motives, and beyond. The Chebotarev density theorem continues to inspire new results, such as the Sato–Tate conjecture and its generalizations.

In the next part, we shall explore the higher ramification groups and the Artin conductor, which refine our understanding of wild ramification and play a crucial role in the functional equation of Artin L-functions.