Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Foundations and Development of Clinical Reasoning Models in Physiotherapy

3. Actual Framework for Clinical Reasoning in Physiotherapy

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APTA | American Physical Therapy Association |

| ARAT | Action Research Arm Test |

| ABC | Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale |

| BRAIN | Biopsychosocial Reasoning Approach In Neurophysiotherapy |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| ESO | European Stroke Organization |

| FAC | Functional Ambulation Category |

| GAS | Goal Attainment Scale |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health |

| MAL | Motor Activity Log |

| NDT | Neurodevelopmental Therapies |

| QST | Quantitative Sensory Testing |

| SMART | Specific, Measurable, Achievable/Attainable, Realistic/Relevant, Timed |

| VO₂max | Maximum Oxygen Consumption |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Mattingly, C. What is Clinical Reasoning? The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1991, 45, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaccia, T; Tardif, J; Triby, E; Charlin, B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: the dual-process theory. Medical Education Online 2011, 16, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlin, B; Tardif, J; Boshuizen, HPA. Scripts and Medical Diagnostic Knowledge: Theory and Applications for Clinical Reasoning Instruction and Research. Academic Medicine 2000, 75, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, K; Gilliland, SJ; Black, LL; Wainwright, SF; Christensen, N. Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapy: A Concept Analysis. Physical Therapy 2019, 99, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen JL, Ten Cate O. Prerequisites for Learning Clinical Reasoning. En: Ten Cate O, Custers EJFM, Durning SJ, editores. Principles and Practice of Case-based Clinical Reasoning Education [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018 [citado 5 de enero de 2025]. p. 47-63. (Innovation and Change in Professional Education; vol. 15). Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64828-6_4.

- Durning, SJ; Artino, AR; Schuwirth, L; Van Der Vleuten, C. Clarifying Assumptions to Enhance Our Understanding and Assessment of Clinical Reasoning: Academic Medicine 2013, 88, 442–448. [PubMed]

- Fischer, R. Public Relations Problem Solving: Heuristics and Expertise. Journal of Public Relations Research 1998, 10, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, EJFM. Medical Education and Cognitive Continuum Theory: An Alternative Perspective on Medical Problem Solving and Clinical Reasoning. Academic Medicine 2013, 88, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassirer, JP. Teaching Clinical Reasoning: Case-Based and Coached: Academic Medicine 2010, 85, 1118–1124.

- Shin, HS. Reasoning processes in clinical reasoning: from the perspective of cognitive psychology. Korean J Med Educ. 2019, 31, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, R; Higgs, J. Core components of communication of clinical reasoning: a qualitative study with experienced Australian physiotherapists. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2012, 17, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, C; Edwards, S. The bases of practice--neurological physiotherapy. Physiother Res Int. 1996, 1, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

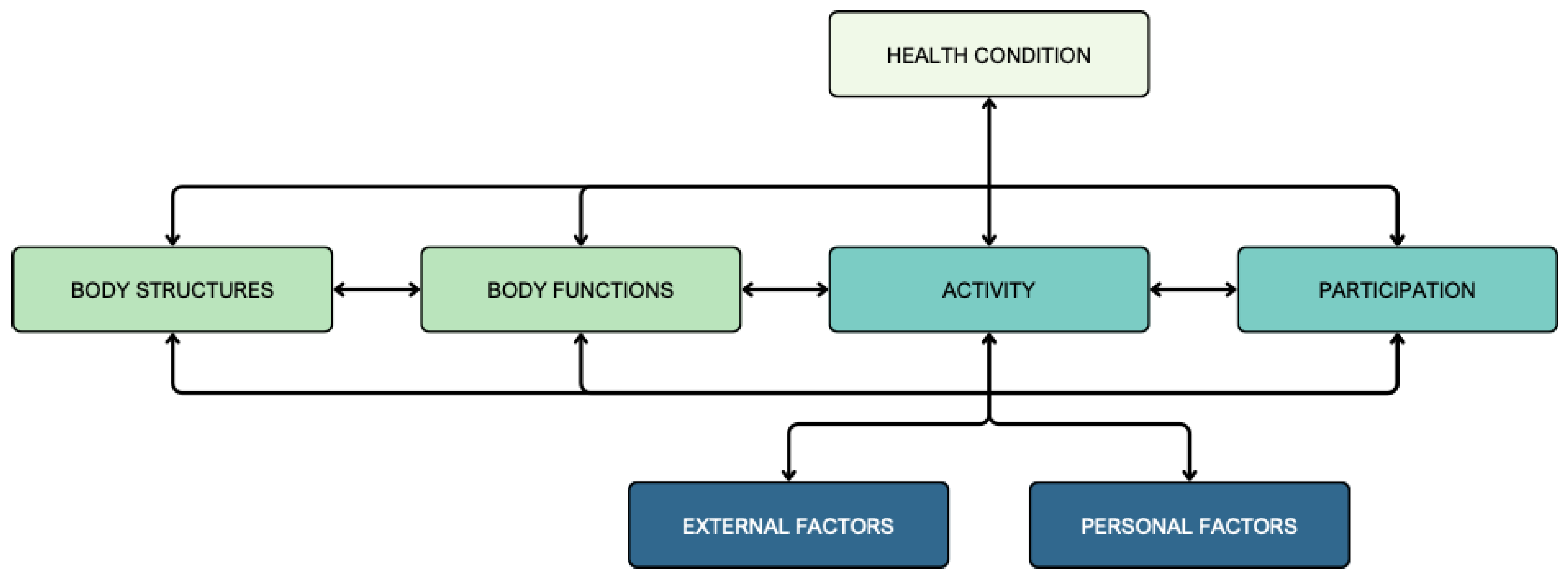

- Lexell, J; Brogårdh, C. The use of ICF in the neurorehabilitation process; Brogårdh, C, Lexell, J, Eds.; NRE, 2015; Volume 36, pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrmann, SA. The Human Movement System: Our Professional Identity. Physical Therapy 2014, 94, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan-Graham, J; Patterson, K; Zabjek, K; Cott, CA. Conceptualizing movement by expert Bobath instructors in neurological rehabilitation. Evaluation Clinical Practice 2017, 23, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsch, S; Carling, C; Cao, Z; Fanayan, E; Graham, PL; McCluskey, A; et al. Bobath therapy is inferior to task-specific training and not superior to other interventions in improving arm activity and arm strength outcomes after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2023, 69, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K; Dorsch, S; McCluskey, A; Schurr, K; Graham, PL; Cao, Z; et al. Bobath therapy is inferior to task-specific training and not superior to other interventions in improving lower limb activities after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2020, 66, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnstrom, S. Movement Therapy in Hemiplegia: A Neurophysiological Approach, 1.a ed; 1970; 200p. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington, CS. Decerebrate Rigidity, and Reflex Coordination of Movements. The Journal of Physiology 1898, 22, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walshe, FMR. On the Genesis and Physiological Significance of Spasticity and Other Disorders of Motor Innervation: With a Consideration of the Functional Relationships of the Pyramidal System. Brain 1919, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, FMR. On the Role of the Pyramidal System in Willed Movements. Brain 1947, 70, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, JW; Carmichael, ST. Broken Movement: The Neurobiology of Motor Recovery after Stroke; The MIT Press, 2017; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, KPS; Marsden, J. The management of spasticity in adults. BMJ 2014, 349, g4737–g4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etoom, M; Khraiwesh, Y; Lena, F; Hawamdeh, M; Hawamdeh, Z; Centonze, D; et al. Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Interventions on Spasticity in People With Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2018, 97, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusola, G; Garcia, E; Albosta, M; Daly, A; Kafes, K; Furtado, M. Effectiveness of physical therapy interventions on post-stroke spasticity: An umbrella review. NRE 2023, 52, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, PHFDA; Glinsky, JV; Fachin-Martins, E; Harvey, LA. Physiotherapy interventions for the treatment of spasticity in people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2021, 59, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobath, B. Adult Hemiplegia Evaluation and Treatment, 3.a ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, S. Defining the Bobath concept using the Delphi technique. Physiother Res Int. 2006, 11, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cott, CA; Graham, JV; Brunton, K. When will the evidence catch up with clinical practice? Physiotherapy Canada 2011, 63, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan-Graham, J; Cott, C; Wright, FV. The Bobath (NDT) concept in adult neurological rehabilitation: what is the state of the knowledge? A scoping review. Part I: conceptual perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation 2015, 37, 1793–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway-Cook, A; Woollacott, MH. Motor Control. Translating Research into Clinical Practice; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, 2013; Vol. 53, pp. 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Vahdat, S; Darainy, M; Ostry, DJ. Structure of Plasticity in Human Sensory and Motor Networks Due to Perceptual Learning. J Neurosci. 2014, 34, 2451–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland [Internet]. 2023 may. Available online: www.strokeguideline.org.

- Guadagnoli, MA; Lee, TD. Challenge Point: A Framework for Conceptualizing the Effects of Various Practice Conditions in Motor Learning. Journal of Motor Behavior 2004, 36, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, KS; Kramer, SF; Dalton, EJ; Hughes, GR; Brodtmann, A; Churilov, L; et al. Timing and Dose of Upper Limb Motor Intervention After Stroke: A Systematic Review. Stroke 2021, 52, 3706–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G; Stinear, C; Essers, B; Munoz-Novoa, M; Branscheidt, M; Cabanas-Valdés, R; et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework. European Stroke Journal 2023, 8, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickenbach, JE; Chatterji, S; Badley, EM; Üstün, TB. Models of disablement, universalism and the international classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps. Social Science & Medicine 1999, 48, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). WHO [Internet]. 2001 [citado 22 de septiembre de 2020]. Available online: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

- Maart S, Sykes C. Expanding on the use of The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Examples and resources. S Afr j physiother [Internet]. 17 de agosto de 2022 [citado 8 de enero de 2025];78(1). Available online: https://sajp.co.za/index.php/sajp/article/view/1614.

- Vargus-Adams, JN; Majnemer, A. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a Framework for Change: Revolutionizing Rehabilitation. J Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, TF; De Melo, LP; Dantas, AATSG; De Oliveira, DC; Oliveira, RANDS; Cordovil, R; et al. Functional activities habits in chronic stroke patients: A perspective based on ICF framework. NRE 2019, 45, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alford, VM; Ewen, S; Webb, GR; McGinley, J; Brookes, A; Remedios, LJ. The use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to understand the health and functioning experiences of people with chronic conditions from the person perspective: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation 2015, 37, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosewilliam, S; Roskell, CA; Pandyan, A. A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2011, 25, 501–514. [Google Scholar]

- Bovend’Eerdt, TJ; Botell, RE; Wade, DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil 2009, 23, 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- Bard-Pondarré, R; Villepinte, C; Roumenoff, F; Lebrault, H; Bonnyaud, C; Pradeau, C; et al. Goal Attainment Scaling in rehabilitation: An educational review providing a comprehensive didactical tool box for implementing Goal Attainment Scaling. J Rehabil Med. 2023, 55, jrm6498. [Google Scholar]

- Malec, JF. Goal Attainment Scaling in Rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1999, 9, 253–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Physical Therapy Association. A Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, Volume I: A Description of Patient Management. Physical Therapy 1995, 75, 707–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. Second Edition. American Physical Therapy Association. Phys Ther. 2001, 81, 9–746. [Google Scholar]

- American Physical Therapy Association. APTA guide to physical Therapist Practice 4.0. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kisner, C; Colby, LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, 5th ed.; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, 2007; 928p. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, AM; Mercier, C; Bourbonnais, D; Desrosiers, J; Gravel, D. Reliability of maximal static strength measurements of the arms in subjects with hemiparesis. Clin Rehabil 2007, 21, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, LT; Martins, JC; Quintino, LF; De Brito, SAF; Teixeira-Salmela, LF; De Morais Faria, CDC. A Single Trial May Be Used for Measuring Muscle Strength With Dynamometers in Individuals With Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. PM&R 2019, 11, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Kispert, CP. Clinical Measurements to Assess Cardiopulmonary Function. Physical Therapy 1987, 67, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, JJ; Dawson, AS; Chu, KS. Submaximal exercise in persons with stroke: test-retest reliability and concurrent validity with maximal oxygen consumption. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashardoust Tajali, S; MacDermid, JC; Grewal, R; Young, C. Reliability and Validity of Electro-Goniometric Range of Motion Measurements in Patients with Hand and Wrist Limitations. Open Orthop J. 2016, 10, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, IG; Yu, IY; Kim, SY; Lee, DK; Oh, JS. Reliability of ankle dorsiflexion passive range of motion measurements obtained using a hand-held goniometer and Biodex dynamometer in stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015, 27, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheo, W; Baerga, L; Miranda, G. Basic Principles Regarding Strength, Flexibility, and Stability Exercises. PM&R 2012, 4, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puce, L; Currà, A; Marinelli, L; Mori, L; Capello, E; Di Giovanni, R; et al. Spasticity, spastic dystonia, and static stretch reflex in hypertonic muscles of patients with multiple sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Noort, JC; Bar-On, L; Aertbeliën, E; Bonikowski, M; Braendvik, SM; Broström, EW; et al. European consensus on the concepts and measurement of the pathophysiological neuromuscular responses to passive muscle stretch. European Journal of Neurology 2017, 24, 981–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, I; Taghizadeh, A; Shakeri, H; Eivazi, M; Jaberzadeh, S. The relationship between isokinetic muscle strength and spasticity in the lower limbs of stroke patients. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2015, 19, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimzadeh Khiabani, R; Mochizuki, G; Ismail, F; Boulias, C; Phadke, CP; Gage, WH. Impact of Spasticity on Balance Control during Quiet Standing in Persons after Stroke. Stroke Research and Treatment 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, AS; Durward, BR; Rowe, PJ; Paul, JP. What is balance? Clin Rehabil 2000, 14, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérennou, D; Chauvin, A; Piscicelli, C; Hugues, A; Dai, S; Christiaens, A; et al. Determining an optimal posturography dataset to identify standing behaviors in the post-stroke subacute phase. Cross-sectional study. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2023, 66, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, BL; Lephart, SM. The sensorimotor system, part I: the physiologic basis of functional joint stability. J Athl Train. 2002, 37, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pickering, GT; Fine, NF; Knapper, TD; Giddins, GEB. The reliability of clinical assessment of distal radioulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg Eur 2022, 47, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beynon, A; Le May, S; Theroux, J. Reliability and validity of physical examination tests for the assessment of ankle instability. Chiropr Man Therap 2022, 30, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, AM; Bourbonnais, D; Mercier, C. Differences in the magnitude and direction of forces during a submaximal matching task in hemiparetic subjects. Experimental Brain Research 2004, 157, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukelow, SP; Herter, TM; Bagg, SD; Scott, SH. The independence of deficits in position sense and visually guided reaching following stroke. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil. 2012, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M; Kawakami, M; Okuyama, K; Ishii, R; Oshima, O; Hijikata, N; et al. Validity and Reliability of the Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament Test and the Thumb Localizing Test in Patients With Stroke. Frontiers in Neurology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, GZ; Manuguerra, M; Chow, R. How to analyze the Visual Analogue Scale: Myths, truths and clinical relevance. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2016, 13, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mücke, M; Cuhls, H; Radbruch, L; Baron, R; Maier, C; Tölle, T; et al. Quantitative sensory testing (QST). Schmerz 2021, 35, 153–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckryd, E. Pain assessment 3 × 3: a clinical reasoning framework for healthcare professionals. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2023, 23, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, S; Swanik, CB; Fu, F. Reestablishing Neuromuscular Control. En: Prentice WE, 5th, editores. Rehabilitation Techniques for Sports Medicine and Athletic Training; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2011; pp. 122–143. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas J. Neuromuscular Control Systems, Models of neuromotor control. En: Jaeger D, Jung R, editores. Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2014 [citado 30 de abril de 2025]. p. 1-9. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4614-7320-6_711-1.

- Danion, F.; Latash, M.L. (Eds.) Motor control: theories, experiments, and applications; Oxford University Press: New York, 2011; 511p. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, E.R.; Koester, J.; Mack, S.; Siegelbaum, S. (Eds.) Principles of neural science, Sixth edition; McGraw Hill: New York, 2021; 1646p. [Google Scholar]

- McMorland AJC, Runnalls KD, Byblow WD. A Neuroanatomical Framework for Upper Limb Synergies after Stroke. Front Hum Neurosci [Internet]. 16 de febrero de 2015 [citado 22 de enero de 2025];9. Available online: http://journal.frontiersin.org/Article/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00082/abstract. [CrossRef]

- Israely, S; Leisman, G; Carmeli, E. Neuromuscular synergies in motor control in normal and poststroke individuals. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2018, 29, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaimi, B; Edgley, SA; Soteropoulos, DS; Baker, SN. Changes in descending motor pathway connectivity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkey. Brain 2012, 135, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, JG; Chen, A; Ellis, MD; Yao, J; Heckman, CJ; Dewald, JPA. Progressive recruitment of contralesional cortico-reticulospinal pathways drives motor impairment post stroke. The Journal of Physiology 2018, 596, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwerin, S; Dewald, JPA; Haztl, M; Jovanovich, S; Nickeas, M; MacKinnon, C. Ipsilateral versus contralateral cortical motor projections to a shoulder adductor in chronic hemiparetic stroke: implications for the expression of arm synergies. Exp Brain Res. 2008, 185, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugl-Meyer, A; Jääskö, L; Leyman, I; Olsson, S; Steglind, S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance - PubMed. Scand J Rehabil Med 1975, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madroñero-Miguel, B; Cuesta-García, C. Spanish consensus of occupational therapists on upper limb assessment tools in stroke. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2023, 86, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S; Jaiswal, A; Norman, K; DePaul, V. Heterogeneity and Its Impact on Rehabilitation Outcomes and Interventions for Community Reintegration in People With Spinal Cord Injuries: An Integrative Review. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation 2019, 25, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, JC; Williams-Gray, CH; Barker, RA. The clinical heterogeneity of Parkinson’s disease and its therapeutic implications. Eur J of Neuroscience 2019, 49, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E; Kim, TH; Koo, H; Yoo, J; Heo, JH; Nam, HS. Heterogeneity in costs and prognosis for acute ischemic stroke treatment by comorbidities. J Neurol. 2019, 266, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, KW. Heterogeneity of Stroke Pathophysiology and Neuroprotective Clinical Trial Design. Stroke 2002, 33, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

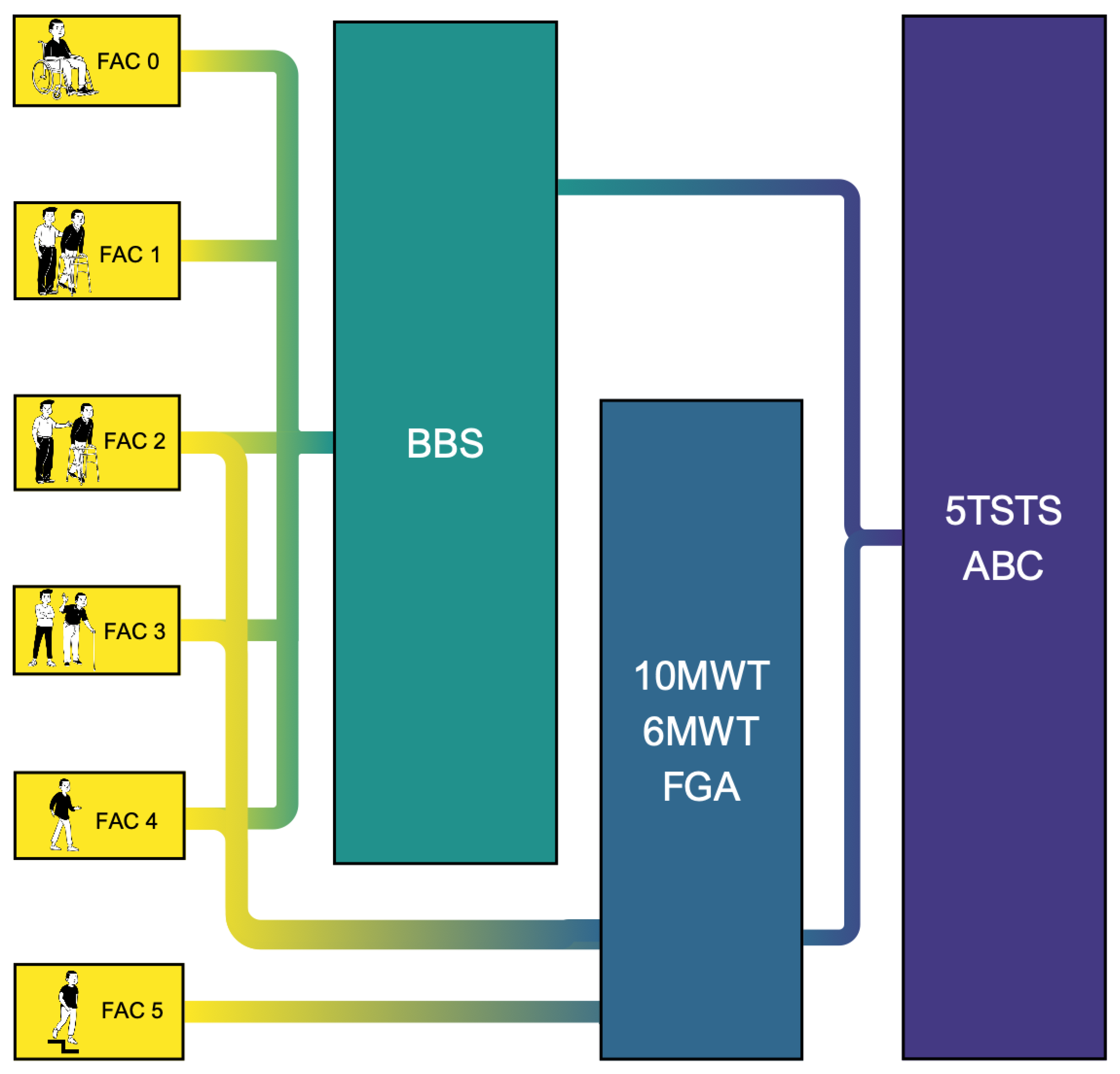

- Mehrholz, J; Wagner, K; Rutte, K; Meiβner, D; Pohl, M. Predictive Validity and Responsiveness of the Functional Ambulation Category in Hemiparetic Patients After Stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2007, 88, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, MK; Gill, KM; Magliozzi, MR. Gait Assessment for Neurologically Impaired Patients. Physical Therapy 1986, 66, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, JL; Potter, K; Blankshain, K; Kaplan, SL; O’Dwyer, LC; Sullivan, JE. A Core Set of Outcome Measures for Adults With Neurologic Conditions Undergoing Rehabilitation: A CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy 2018, 42, 174–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, M; Aamodt, G; Marit Mengshoel, A. Measuring balance in sub-acute stroke rehabilitation. Advances in Physiotherapy 2006, 8, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, JF; Nadeau, S. Standing balance assessment in ASIA D paraplegic and tetraplegic participants: Concurrent validity of the Berg Balance Scale. Spinal Cord. 2010, 48, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, AL; Crowner, BE; Earhart, GM. Functional Gait Assessment and Balance Evaluation System Test: Reliability, Validity, Sensitivity, and Specificity for Identifying Individuals With Parkinson Disease Who Fall. Physical Therapy 2011, 91, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltamaa, J; Sarasoja, T; Leskinen, E; Wikström, J; Mälkiä, E. Measuring Deterioration in International Classification of Functioning Domains of People With Multiple Sclerosis Who Are Ambulatory. Physical Therapy 2008, 88, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, JH; Hsu, MJ; Hsu, HW; Wu, HC; Hsieh, CL. Psychometric Comparisons of 3 Functional Ambulation Measures for Patients With Stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghwiri, AA; Khalil, H; Al-Sharman, A; El-Salem, K. Psychometric properties of the Arabic Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale in people with multiple sclerosis: Reliability, validity, and minimal detectable change. NRE 2020, 46, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishige, S; Wakui, S; Miyazawa, Y; Naito, H. Reliability and validity of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale-Japanese (ABC-J) in community-dwelling stroke survivors. Phys Ther Res. 2020, 23, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, G; Oates, AR; Arora, T; Lanovaz, JL; Musselman, KE. Measuring balance confidence after spinal cord injury: the reliability and validity of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2017, 40, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossier, P; Wade, DT. Validity and reliability comparison of 4 mobility measures in patients presenting with neurologic impairment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2001, 82, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, S; Mody, SH; Woodman, RC; Studenski, SA. Meaningful Change and Responsiveness in Common Physical Performance Measures in Older Adults. J American Geriatrics Society 2006, 54, 743–749. [Google Scholar]

- Scivoletto, G; Tamburella, F; Laurenza, L; Foti, C; Ditunno, JF; Molinari, M. Validity and reliability of the 10-m walk test and the 6-min walk test in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 2011, 49, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, YC; Dlugonski, DD; Pilutti, LA; Sandroff, BM; Motl, RW. The reliability, precision and clinically meaningful change of walking assessments in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013, 19, 1784–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, SS; Canning, CG; Sherrington, C; Fung, VSC. Reproducibility of measures of leg muscle power, leg muscle strength, postural sway and mobility in people with Parkinson’s disease. Gait & Posture 2012, 36, 639–642. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Solana, J; Pardo-Hernández, R; González-Bernal, JJ; Sánchez-González, E; González-Santos, J; Soto-Cámara, R; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) Scale in Post-Stroke Patients—Spanish Population. IJERPH 2022, 19, 14918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, T; Pinkowski, C; Van Wijck, F; Kim, IH; Di Bella, P; Johnson, G. Reliability and validity of arm function assessment with standardized guidelines for the Fugl-Meyer Test, Action Research Arm Test and Box and Block Test: a multicentre study. Clin Rehabil 2005, 19, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, HM; Chen, CC; Hsueh, IP; Huang, SL; Hsieh, CL. Test-Retest Reproducibility and Smallest Real Difference of 5 Hand Function Tests in Patients With Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009, 23, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oña, ED; Sánchez-Herrera, P; Cuesta-Gómez, A; Martinez, S; Jardón, A; Balaguer, C. Automatic Outcome in Manual Dexterity Assessment Using Colour Segmentation and Nearest Neighbour Classifier. Sensors 2018, 18, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, E; Lexell, J; Brogårdh, C. Test−Retest Reliability and Convergent Validity of Three Manual Dexterity Measures in Persons With Chronic Stroke. PM&R 2016, 8, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proud, EL; Bilney, B; Miller, KJ; Morris, ME; McGinley, JL. Measuring Hand Dexterity in People With Parkinson’s Disease: Reliability of Pegboard Tests. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2019, 73, 7304205050p1-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervault, M; Balto, JM; Hubbard, EA; Motl, RW. Reliability, precision, and clinically important change of the Nine-Hole Peg Test in individuals with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2017, 40, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, PW; Bode, RK; Lai, SM; Perera, S. Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: the Stroke Impact Scale. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2003, 84, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, S; Richardson, P. Occupational Therapy Outcomes for Clients With Traumatic Brain Injury and Stroke Using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2007, 61, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Peláez, M; Pardo-Hernández, R; González-Bernal, JJ; Soto-Cámara, R; González-Santos, J; Fernández-Solana, J. Reliability and Validity of the Motor Activity Log (MAL-30) Scale for Post-Stroke Patients in a Spanish Sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 14964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, M; Vaughan-Graham, J; Holland, A; Magri, A; Suzuki, M. The Bobath concept – a model to illustrate clinical practice. Disability and Rehabilitation 2019, 41, 2080–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).