1. Introduction

Globally, the World Health Organization upholds health as a human right and is fundamental to its subspecialty of Universal Health Coverage(UHC) [

1]. UHC emphasizes the expectation of accessing effective quality healthcare services at the right time and place, while bearing manageable costs[

2,

3]. Evidence-based practice (EBP) integrates the best available research and patient-centered knowledge blended with experience in the clinical field[

4,

5]. Healthcare professionals are expected to provide evidence-based care. As a result, by the time students in the healthcare profession complete their studies, they should be equally confident in applying evidence-based[

6] which is a foundation for improving the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions and enhancing the quality of physiotherapy services[

7]. Therefore, the World Confederation for Physical Therapy (WCPT) advocates that physiotherapists embrace EBP principles with an emphasis on managing patients and communities based on the best available evidence[

8,

9,

10]. While there has been an increase in international trends toward implementing EBP, the awareness and practice of EBP among physiotherapists in India have been less researched, specifically, their understanding, recommendations, and compliance[

11,

12,

13]. The majority of published literature focuses on the integration of EBP in developed Western countries, assessing the barriers and enablers for EBP integration, but neglects the challenges that are specific to the Indian context, including limited resources and institutional and cultural variations[

7,

14,

15]. Although physiotherapy plays a central role in managing non-communicable diseases, such as pre-postoperative rehabilitation of sports injuries, post-stroke rehabilitation, cardiorespiratory rehabilitation, movement disorders, women's health, and musculoskeletal disorders, there is a growing belief that EBP use is inconsistent and may lead to inferior patient outcomes[

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This study seeks to address this gap by examining how knowledge of EBP, awareness of its principles, and its implementation by physiotherapists in India respond to the global call for EBP implementation to embrace what is described as the best practice of informed decision-making concerning the realities of both relevant and desirable resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among Indian Physiotherapists from various Indian states and union territories engaged in the public sector, private hospitals, or self-employed. The ethical approval was obtained from the Departmental Research Committee, SAHS, Galgotias University (DRC/FEA/94/24) affirming the ethical standards and oversight for the research and the study was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trial Registry India CTRI/2024/09/073590. The study adhered to the principles of Helsinki[

23]. All participants provided online consent, following the General Data Protection Regulation guidelines recommended by the European Union[

24]. Data were collected using a structured online Google form. The study was reported per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations[

25].

2.2. Data Collection and Procedure

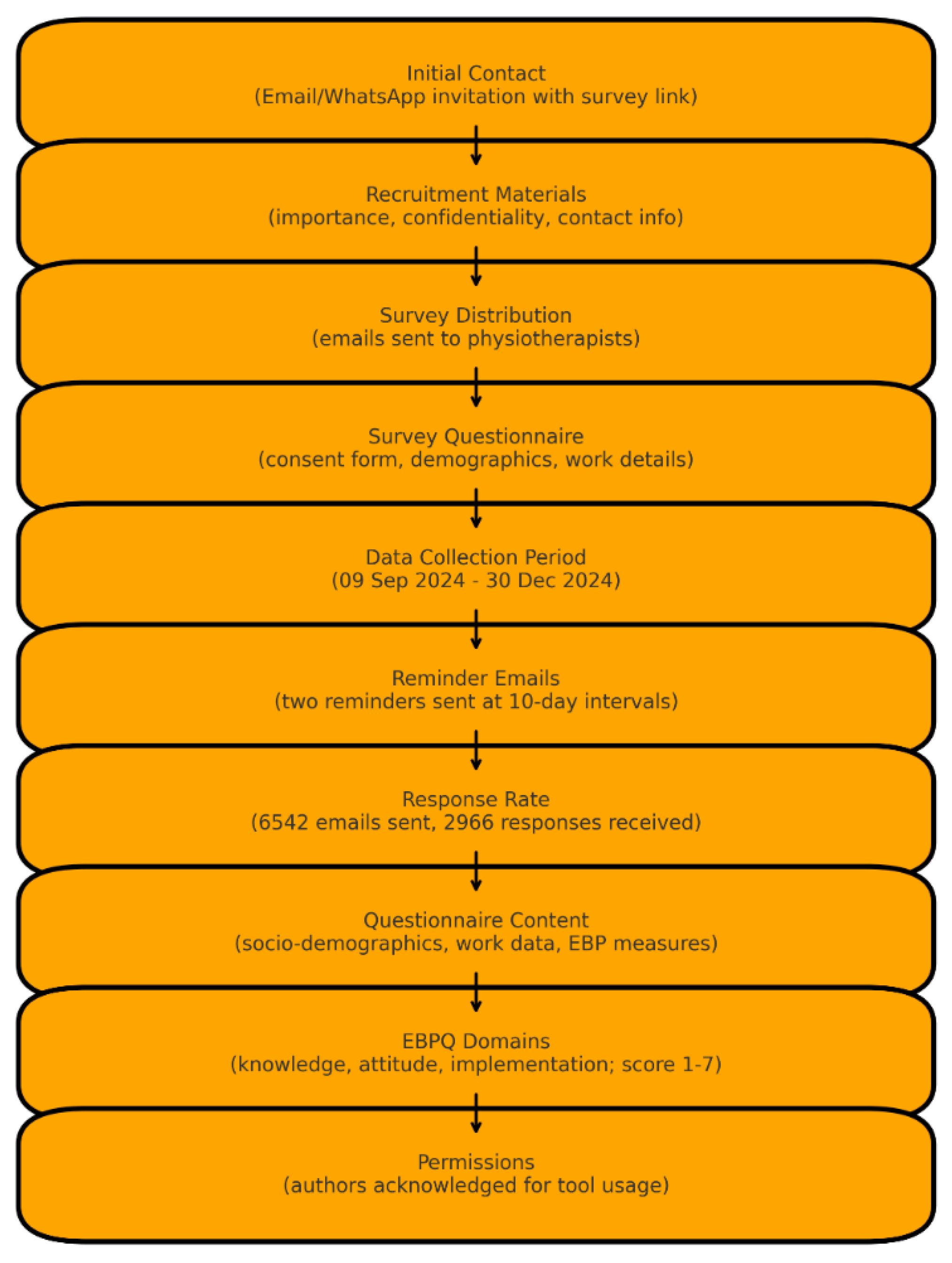

Physiotherapy professionals were initially contacted via email and social media applications (WhatsApp app), which included an invitation to participate, explanation of the study’s purpose, and a link to the online survey. Recruitment materials highlighted the importance of participation, confidentiality assurance, and contact information for queries. A web-based survey questionnaire was sent to the email IDs of Registered Physiotherapists secured from the Indian Association of Physiotherapists, Treasurer. The online survey questionnaire consisted of a consent form and questions seeking sociodemographic information, work-related characteristics, qualification status, professional licensing authority, years of clinical experience, and type of practice. Data were collected from September 9, 2024, to December 30, 2024. A reminder email was sent twice at 10-day intervals to those who did not respond by verifying the subsequent delivery to improve the response rate. Among the 6542 emails sent, 2966 opened and responded at least once. The web-based questionnaire consisted of three domains aimed at collecting sociodemographic, work-related, and evidence-based data. The Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire (EBPQ) is a reliable, valid, standardized, and geographically widely used among Allied Healthcare Professionals, and a freely accessible, easy-to-use outcome tool to assess knowledge, attitude, and implementation of EBP in clinical settings. It includes questions to evaluate three primary domains: knowledge and skills in EBP, attitude towards EBP, and implementation of EBP. Responses are scored numerically from 1-7(i.e. 1=Poor and 7= Best).). The average score is calculated for each subscale. Higher scores generally indicate greater knowledge, positive attitudes, and more frequent EBP implementation. Permission to use is granted to anyone who proviso that the authors are acknowledged for publication[

26].

2.3. Sample Size, Sampling, and Eligibility Criteria

The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft online calculator with the following assumptions and formula for single population proportion; 99% confidence interval with the margin of error kept at 5% and a response distribution rate of 40% with a total population size of 12445 registered physiotherapists with the Indian Association of Physiotherapists as per the 2021annual active members, the minimum estimated sample size was 606[

27]. A list of email IDs of registered physiotherapists was obtained from the administrative records of the IAP. We ensured that the confidentiality and privacy of participants were maintained.

2.4. Statistical Section

The data was summarized with frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. Cronbach's alpha was used to determine the internal consistency of the 24 EBP questionnaire items. Linear regression was used to determine the predictive power of demographic data for EBP scores, and all assumptions of multiple linear regression were met. Additionally, the Durbin-Watson statistic of 1.308 indicated no severe autocorrelation, and collinearity diagnostics showed no multicollinearity issues (VIF < 10). SPSS version 20 was used for the analysis, and the p-value was set at 0.05.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Survey Distribution and Data Collection Process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Survey Distribution and Data Collection Process.

3. Results

3.1. Internal Consistency of the Questionnaire

The internal consistency of the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) skills scale was assessed using Cronbach's alpha, which yielded a value of 0.789, indicating good reliability. Corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.321 to 0.621, confirming that all items contributed meaningfully to the overall scale, whereas inter-item correlations ranged from 0.212 to 0.537, demonstrating appropriate item relationships without redundancy. The analysis of Cronbach’s alpha, if an item was deleted, showed values ranging from 0.764 to 0.794, with no substantial improvement in alpha upon item removal, affirming the retention of all 24 items.

3.2. Demographic Data

The study included 2,966 physiotherapists, with females representing the majority of 1,845 (62.2%). Regarding educational qualifications, 1,228 (41.4%) held a Bachelor of Physiotherapy (BPT) degree, while 1,436 (48.4%) held a Master of Physiotherapy (MPT) degree, and 302 (10.2%) had other qualifications, including Doctorates and Diplomas. In this study, there were 913 (30.8 %) academic staff, 1, 227 (41.4 %) private practice clinicians, 116 (3.9 %) government hospital clinicians, and 710 (23.9 %) home care therapists. Regionally, physiotherapists were most represented in Maharashtra (431, 14.5%) and Tamil Nadu 379,12.8%.

The evidence-based practice (EBP) scores across demographic variables showed variations in EBP scores. Clinicians in the private sector achieved the highest EBP score (104.41 ± 9.82), followed closely by home care therapists (104.38 ± 9.16), while government hospital clinicians had the lowest (101.83 ± 9.23). Participants from Rajasthan state exhibited the highest EBP score (104.20 ± 9.80), whereas those from Jammu and Kashmir (103.35 ± 9.30) scored lower. Gender analysis showed negligible differences in scores between females (103.62 ± 9.29) and males (103.96 ± 10.05). Regarding educational qualifications, individuals with a Doctorate in Physiotherapy (PhD) demonstrated superior performance with the highest EBP score (105.18 ± 10.20), particularly excelling in the skills domain (61.30 ± 6.88), compared to those with a Master of Physiotherapy (MPT; 103.71 ± 9.66) or Bachelor of Physiotherapy (BPT; 103.49 ± 9.35). These findings highlight the influence of professional roles, geographic regions, and educational qualifications on the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices (

Table 1).

3.3. Regression Analysis with an Overall Score as the Independent Variable

Linear regression analysis revealed significant predictors of total Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) score, highlighting the influence of demographic, professional, and regional factors. Clinicians working in the private sector exhibited higher EBP scores than other practice types (B = 0.958, SE = 0.439, t = 2.185,

p = .029). Regional disparities were evident, with practitioners in Bihar (B = 13.585, SE = 6.699, t = 2.028,

p = .043), Chhattisgarh (B = 14.710, SE = 6.761, t = 2.176,

p = .030), and Haryana (B = 5.432, SE = 2.254, t = 2.410,

p = .016) demonstrating significantly higher EBP scores, whereas those in Himachal Pradesh (B = -15.553, SE = 6.750, t = -2.304,

p = .021) and Maharashtra (B = -2.508, SE = 0.930, t = -2.698,

p = .007) reported lower scores. Additionally, licensing authority affiliation significantly impacted EBP scores, with practitioners licensed by the Indian Association of Physiotherapists (B = -7.142, SE = 3.026, t = -2.360,

p = .018) and those not licensed (B = -7.720, SE = 3.084, t = -2.503,

p = .012) showing reduced EBP scores compared to their counterparts. Although other factors such as years of clinical experience (B = -0.030, SE = 0.108, t = -0.275,

p = .784) and gender (male: B = 0.189, SE = 0.358, t = 0.527,

p = .598) were included in the model, they did not show significant contributions. The model explained a modest but statistically significant variance in EBP scores (adjusted R² = 0.044,

p < .001), with an overall root mean square error (RMSE) of 9.378. These findings underscore the need to address regional and professional disparities in EBP practices, potentially through targeted training and policy reform (

Table 2). This is a figure. These schemes follow another format. If there are multiple panels, they should be listed as follows: (a) description of what is contained in the first panel; (b) description of what is contained in the second panel. Figures should be placed in the main text near the first time they are cited.

3.4. With Practice Score EBP as an Independent Variable

Linear regression analysis revealed significant predictors of the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) score, highlighting the influence of demographic, professional, and regional factors. Among the demographic factors, gender (male) was associated with higher EBP Practice scores (B = 0.25, SE = 0.11, t = 2.24, p = .026). Regional disparities were evident, with practitioners in Haryana (B = 3.42, SE = 0.70, t = 4.89, p < .001) demonstrating significantly higher EBP Practice scores, while those in Himachal Pradesh (B = -4.22, SE = 2.09, t = -2.02, p = .044) showed lower scores. Licensing authority affiliation also significantly impacted EBP scores, with practitioners licensed by the Indian Association of Physiotherapists (B = -1.95, SE = 0.94, t = -2.08, p = .037) and those not licensed (B = -1.98, SE = 0.96, t = -2.08, p = .038) reporting reduced EBP Practice scores compared to their counterparts. Other variables, such as years of clinical experience (B = 0.04, SE = 0.03, t = 1.21, p = .228) and age (B = 0.007, SE = 0.022, t = 0.30, p = .764), were not significant predictors. The model explained a modest but statistically significant variance in EBP Practice scores (R2 = 0.057, adjusted R2 = 0.043, p < .001), with an overall root mean square error (RMSE) of 2.907. These findings highlight the impact of regional and licensing factors on EBP practices, and suggest the need for tailored interventions to address these disparities.

3.5. With Attitude Score EBP (EBP)as an Independent Variable

The linear regression model evaluating predictors of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Attitude revealed a statistically significant relationship (F(43, 2922) = 2.49, p < 0.001), explaining 3.5% of the variance in EBP attitude (R² = 0.035, adjusted R² = 0.021). Significant predictors included professional licensing authority and type of practice, with clinicians in private practice demonstrating a positive association (β = 2.361, p = 0.018), whereas those licensed by the State Council and certified by the Paramedic State Council showed a negative association (β = -2.861, p = 0.004). The state of practice also influenced attitudes, with practitioners in Bihar (β = 2.887, p = 0.004) and Chhattisgarh (β = 2.2, p = 0.028) displaying significantly higher EBP attitudes, whereas Maharashtra showed a negative association (β = -2.188, p = 0.029). Other variables, such as age and years of clinical experience, were not significant predictors (P > 0.05).

3.6. With Skill Score (EBP) as an Independent Variable

The linear regression model evaluating the predictors of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) skills revealed a statistically significant relationship (F (43, 2922) = 4.295, p < 0.001), explaining 5.9% of the variance in EBP Skills (R² = 0.059, adjusted R² = 0.046). Significant predictors included type of practice, with clinicians in private practice (β = 0.702, p = 0.020) and home care therapists (β = 0.9, p = 0.009) showing positive associations. Among the state regions, practitioners in Himachal Pradesh (β = -10.18, p = 0.028) and Maharashtra (β = -2.29, p < 0.001) exhibited significantly negative associations with EBP Skills. Age was also a significant predictor (β = 0.098, p = 0.045), while years of clinical experience (β = -0.085, p = 0.253) and sex (β = -0.01, p = 0.967) were not significant predictors.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional survey provided a comprehensive evaluation of EBP awareness and knowledge and implementation achievements among 2,966 Indian physiotherapists. It showed major differences in EBP engagement across various professional roles and regions and between people with different levels of education. The EBP scores of private practice clinicians and home care therapists were higher than those of physiotherapists employed by the government hospital sector, potentially because private practitioners have better autonomy and access to treatment resources and patient-centered care practices. The adoption of EBP showed regional variations because Rajasthan, along with Bihar Chhattisgarh and Haryana, exhibited better engagement than Jammu, Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Maharashtra. EBP implementation success depends heavily on resource availability and institutional backing according to these identified differences. Furthermore, doctorate-level physiotherapists achieved superior EBP skills, whereas doctorate education was essential for developing evidence-based decision-making abilities among clinicians. Studies have demonstrated that advanced education in postgraduate programs helps healthcare providers properly understand research data along with their capability to transform scientific evidence into clinical practice for better patient results[

28,

29,

30] Prospective research should examine whether redesigning the undergraduate curriculum will address EBP knowledge deficiency during the initial physiotherapy education[

31]. The adoption of EBP showed dependence on personnel background, geographic location, and licensing body policies through regression testing[

32,

33,

34]. Traditional demographic factors including clinical experience duration and age alongside gender proved to be either minimal or sporadic in their contributions to readiness for EBP Private practice physiotherapists received more points in EBP surveys since they encounter less bureaucracy and their incentives align with staying aware of the latest evidence-based practices[

35,

36,

37].Positive attitudes toward EBP among a wide range of healthcare professionals, including nurses, physiotherapists, physicians, occupational therapists, and psychologists, have been demonstrated in previous studies [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].Research must explore the impact of private practice autonomy on EBP adoption versus the barriers that government institutions raise against evidence-based practice implementation[

22].Regional discrepancies in EBP scores highlight the impact of localized factors, such as infrastructure, access to training, and professional development opportunities. These findings emphasize the need for region-specific capacity-building programs that integrate localized challenges such as infrastructure limitations and access to training[

44,

45]

. Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that membership in professional organizations significantly enhances EBP engagement by providing access to training and research resources [

46,

47]. Policymakers should consider strengthening institutional frameworks to facilitate continuous learning and professional development[

48].Evaluation-based practice scores differ between regions due to specific factors that affect healthcare delivery infrastructure, together with training accessibility and professional growth opportunities[

49,

50,

51], which demonstrates why targeted capacity-building initiatives need to develop regional programs that address the unique problems of infrastructure and training access in specific areas[

52].Membership in professional organizations leads to better EBP engagement according to research because these organizations offer training and research assets to their members[

53]. The development of continuing learning and professional development institutional structures should be prioritized by policy directors. Despite its strengths, this study had some limitations. The cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences regarding the adoption of EBP. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of a response bias. Future qualitative studies should explore individual barriers and facilitators of EBP adoption, which may not be fully captured in survey-based research[

22,

31] longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of targeted interventions on EBP engagement among physiotherapists.

5. Conclusions

This nationwide study underscores the multifaceted factors that influence EBP adoption among Indian physiotherapists. These findings highlight the critical role of educational background, regional disparities, and practice settings in shaping EBP implementation. Targeted strategies, including curriculum enhancements, policy reforms, and regional capacity-building initiatives, are essential to fostering a more consistent and widespread adoption of EBP in physiotherapy practice across India.

Supplementary Materials

The data set information can be downloaded at:

https://figshare.com, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28254956.v1.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions is required. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, MS,AC,FK and J.S.; methodology, MS,JS,AP,RV.; software, BN, and BMW.; validation, BJ,FK,RHR,SK,KRV,AA,MMA., M.I.A and SA.; formal analysis, FK,SK,JS,KRV.; investigation, MS,SA,JS,AP,KRV,and AC.; resources, MMA,AA.; data curation, MS,JS,AP,and BJ.; writing—original draft preparation, MS,JS,AC,BJ,SA,RV,BMW,SK, M.I.A and MMA.; writing—review and editing, MS,FK,AC,JS,SA,AP,RV,BJ,RHR,BN,BMW,SK,SK,KRV,AA, M.I.A and MMA.; visualization, AC,RV,JS,SA.; supervision, AC,RHR,BJ,.; project administration, MMA,AA and AC.; funding acquisition,M.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for supporting this project through Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical approval was obtained from the Departmental Research Committee, SAHS, Galgotias University (DRC/FEA/94/24) affirming the ethical standards and oversight for the research and the study was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trial Registry India CTRI/2024/09/073590.The study adhered to the principles of Helsinki[

23]. All the participants provided online consent following the General Data Protection Regulation guideline recommended by the European Union[

24]. .

Informed Consent Statement

All the participants provided online consent following the General Data Protection Regulation guideline recommended by the European Union.

Data Availability Statement

.The data set information can be downloaded at:

https://figshare.com, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28254956.v1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the Indian Physiotherapists who voluntarily participated in this study. We would like to thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for supporting this project through Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EBP |

Evidence Based Practice |

| DRC |

Departmental Research Committee |

| CTRI |

Clinical Trial Registry India |

| UHC |

Universal Health Coverage |

References

- 2WHO, World Bank. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2021 Global Monitoring Report. 2021.

- Orem JN, Panisset U. Evidence-informed decision-making for health policy and programmes. 2021.

- Partridge ACR, Mansilla C, Randhawa H, Lavis JN, El-Jardali F, Sewankambo NK. Lessons learned from descriptions and evaluations of knowledge translation platforms supporting evidence-informed policy-making in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Heal Res Policy Syst 2020;18:1–22. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: An approach to clinical problem-solving. Br Med J 1995;310:1122–6. [CrossRef]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71–2. [CrossRef]

- Olsen NR, Bradley P, Lomborg K, Nortvedt MW. Evidence based practice in clinical physiotherapy education: A qualitative interpretive description. BMC Med Educ 2013;13. [CrossRef]

- Scurlock-Evans L, Upton P, Upton D. Evidence-based practice in physiotherapy: a systematic review of barriers, enablers and interventions. Physiotherapy 2014;100:208–19.

- Schubert A. What speech therapists, occupational therapists and physical therapist need to know to become evidence-based practitioners: A cross-sectional study. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2019;140:43–51. [CrossRef]

- Rushton A, Calvert M, Wright C, Freemantle N. Physiotherapy trials for the 21st century - Time to raise the bar? J R Soc Med 2011;104:437–41. [CrossRef]

- Physiotherapy W. Evidence-based practice Policy statement 2019.

- P Panhale V, Bellare B, Jiandani M. Evidence-based practice in Physiotherapy curricula: A survey of Indian Health Science Universities. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2017;5:101–7.

- Nolan P, Bradley E. Evidence-based practice: implications and concerns. J Nurs Manag 2008;16:388–93. [CrossRef]

- Majdzadeh R, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Gholami J, Ahghari S. Strengthening evidence-based decision-making: is it possible without improving health system stewardship? Health Policy Plan 2012;27:499–504. [CrossRef]

- ShahAli S, Kajbafvala M, Fetanat S, Karshenas F, Farshbaf M, Hegazy F, et al. Barriers and facilitators of evidence-based physiotherapy practice in Iran: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care 2023;21:1507–28. [CrossRef]

- Panhale VP, Bellare B. Evidence-based practice among physiotherapy practitioners in Mumbai, India. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2015;28:154–5. [CrossRef]

- Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HMC, Koers H, Jongert MWA, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: A practice guideline. Netherlands Hear J 2013;21:429–38. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça LDM, Schuermans J, Denolf S, Napier C, Bittencourt NFN, Romanuk A, et al. Sports injury prevention programmes from the sports physical therapist’s perspective: An international expert Delphi approach. Phys Ther Sport Off J Assoc Chart Physiother Sport Med 2022;55:146–54. [CrossRef]

- Lee KE, Choi M, Jeoung B. Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Exercise in Improving Physical Function of Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi F, Ahmed I. Role of physical therapy in women’s health. J Pak Med Assoc 2022;72:603–4.

- Nielsen G, Stone J, Matthews A, Brown M, Sparkes C, Farmer R, et al. Physiotherapy for functional motor disorders: A consensus recommendation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:1113–9. [CrossRef]

- Desmeules F, Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Champagne F, Hinse O, Woodhouse LJ. Advanced practice physiotherapy in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13. [CrossRef]

- Paci M, Faedda G, Ugolini A, Pellicciari L. Barriers to evidence-based practice implementation in physiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Heal Care J Int Soc Qual Heal Care 2021;33. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association (WMA). Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects 2009;14:233–8. [CrossRef]

- Plötz FB, Bekhof J. [The General Data Protection Regulation and clinical guidelines evaluation]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2018;162.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet (London, England) 2007;370:1453–7. [CrossRef]

- Upton D, Upton P. Development of an evidence-based practice questionnaire for nurses. J Adv Nurs 2006;53:454–8. [CrossRef]

- Bilal MA, Ur Rehman H, Mehmood K, Fazal K, Siddiqui A, Irfan S, et al. the Impact of Covid 19 Pandemic on Effective Learning - Sharing a Developing Country’S Experience. Pakistan J Radiol 2021;31:232–7.

- Hasani F, MacDermid JC, Tang A, Kho M, Alghadir AH, Anwer S. Knowledge, Attitude and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice among Physiotherapists Working in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare, vol. 8, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020, p. 354.

- Ashworth M, Schofield P, Durbaba S, Ahluwalia S. Patient experience and the role of postgraduate GP training: a cross-sectional analysis of national Patient Survey data in England. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract 2014;64:e168-77. [CrossRef]

- van der Leeuw RM, Lombarts KMJMH, Arah OA, Heineman MJ. A systematic review of the effects of residency training on patient outcomes. BMC Med 2012;10:65. [CrossRef]

- Patel H, Shah S, V P. “Joint protection first”: understanding physiotherapists’ implementation of evidence-based interventions in osteoarthritis knee management-a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2025:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gleadhill C, Bolsewicz K, Davidson SRE, Kamper SJ, Tutty A, Robson E, et al. Physiotherapists’ opinions, barriers, and enablers to providing evidence-based care: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Dalheim A, Harthug S, Nilsen RM, Nortvedt MW. Factors influencing the development of evidence-based practice among nurses: a self-report survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:367. [CrossRef]

- Pitsillidou M, Roupa Z, Farmakas A, Noula M. Factors Affecting the Application and Implementation of Evidence-based Practice in Nursing. Acta Inform Medica AIM J Soc Med Informatics Bosnia Herzegovina Cas Drus Za Med Inform BiH 2021;29:281–7. [CrossRef]

- Young JM, Ward JE. Evidence-based medicine in general practice: beliefs and barriers among Australian GPs. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:201–10. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kubaisi N, Al-Dahnaim L, Salama RE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of primary health care physicians towards evidence-based medicine in Doha, Qatar. East Mediterr Health J 2010;16:1189–97. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardsson S, Larsson ME, Eggertsen R, Olsén MF, Johansson K, Nilsen P, et al. Evaluation of a tailored, multi-component intervention for implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in primary care physical therapy: A non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14. [CrossRef]

- Silva A, Valentim D, Martins A, Padula R. Instruments to assess Evidence-Based Practice among healthcare professionals: a systematic review. 2021. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell K. Attitudes and knowledge of primary care professionals towards evidence-based practice: A postal survey. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10:197–205. [CrossRef]

- Weng Y-H, Chen C, Kuo K, Yang C-Y, Lo H-L, Chen K-H, et al. Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice in Relation to a Clinical Nursing Ladder System: A National Survey in Taiwan. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2015;12. [CrossRef]

- Clarke V, Lehane E, Mulcahy H, Cotter P. Nurse Practitioners’ Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice Into Routine Care: A Scoping Review. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs 2021;18:180–9. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal MZ, Rochette A, Mayo NE, Valois M-F, Bussières AE, Ahmed S, et al. Exploring if and how evidence-based practice of occupational and physical therapists evolves over time: A longitudinal mixed methods national study. PLoS One 2023;18:e0283860. [CrossRef]

- Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol 2006;61:271–85. [CrossRef]

- Sterba KR, Johnson EE, Nadig N, Simpson AN, Simpson KN, Goodwin AJ, et al. Determinants of evidence-based practice uptake in rural intensive care units a mixed methods study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17:1104–16. [CrossRef]

- Celebrating World EBHC Day 2024 | World EBHC Day n.d.

- Burgers JS, Grol R, Klazinga NS, Mäkelä M, Zaat J. Towards evidence-based clinical practice: an international survey of 18 clinical guideline programs. Int J Qual Heal Care J Int Soc Qual Heal Care 2003;15:31–45. [CrossRef]

- Newman K, Pyne T, Cowling A. Managing evidence-based health care: a diagnostic framework. J Manag Med 1998;12:138,151-167. [CrossRef]

- Wong ST, Johnston S, Burge F, Ammi M, Campbell JL, Katz A, et al. Comparing the Attainment of the Patient’s Medical Home Model across Regions in Three Canadian Provinces: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthc Policy 2021;17:19–37. [CrossRef]

- Hisham R, Liew SM, Ng CJ. A comparison of evidence-based medicine practices between primary care physicians in rural and urban primary care settings in Malaysia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018933. [CrossRef]

- Shibabaw AA, Chereka AA, Walle AD, Demsash AW, Kebede SD, Gebeyehu AS, et al. Evidence-Based Practice and Its Associated Factors among Health Professionals Working at Public Hospitals in Southwest Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int 2023;2023:4083442. [CrossRef]

- Merza M, Maani A. Global barriers to evidence-based health practice : Cultural , regulatory and resource challenges 2023;6:27–34.

- Khan F, Amatya B, de Groote W, Owolabi M, Syed I, Hajjioui A, et al. Capacity-building in clinical skills of rehabilitation workforce in low- and middle-income countries. J Rehabil Med 2018;50. [CrossRef]

- Evans C, Yeung E, Markoulakis R, Guilcher S. An online community of practice to support evidence-based physiotherapy practice in manual therapy. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2014;34:215–23. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).