1. Introduction

The most cost-effective and environmentally safe method of transporting oil is through pipelines. Oil moves in them at speeds of up to 3 m/s under the influence of pressure differences created by pumping stations. In theoretical studies, oil is modeled as a viscous fluid [

1,

2]. The key role of fluid viscosity is reflected across many industries, with a notable emphasis on the oil and gas sector, where hydrocarbon fluids hold paramount economic and energy significance. Moreover, fluid viscosity plays a central role in the careful design of surface equipment, the complex modeling of reservoir behavior (subsurface porous media), and the precise forecasting of oil recovery potential. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of fluid properties in oil reservoirs becomes an urgent necessity for optimizing extraction and ensuring efficient transportation [

3]. Therefore, the study of the dynamic behavior of viscous fluid in pipelines is a relevant and timely task.

Until now, little attention has been paid to the resonance properties of pipelines with fluid when waves propagate within them, taking into account the viscous properties of the fluid, due to the difficulty and complexity of the problem. In particular, the dynamic response of cylindrical shells moving along the shell axis has attracted the attention of numerous researchers [

4,

5]. Natural waves are widely used in oil transportation (as a means of non-destructive testing of surfaces and the surface layer of samples). In [

6], torsional waves in an infinitely long viscoelastic cylindrical shell filled with a viscous fluid are considered. The viscous properties of the cylindrical shell material are described by hereditary Boltzmann–Volterra integral relations with different relaxation kernels.

Several approaches have been developed for classifying petroleum products. According to the U.S. definition, heavy oil is characterized by a viscosity ranging from 10² to 10⁴ centipoise at a given reservoir temperature [

7]. These classifications are used for the transportation of crude oil.

The study of viscous fluid flow in pipes under various flow regimes is of great importance in science and engineering. All fluids in nature exhibit viscosity and offer resistance to flow. Moreover, internal friction arises as the fluid moves [

8,

9]. This slows down the movement of fluid layers relative to each other compared to low-viscosity fluids, which flow much more easily due to correspondingly lower frictional forces. Despite this distinction between low- and high-viscosity fluids, a review of high-viscosity fluid flows in pipes should generally cover the topic of viscous fluid flow in pipes and channels [

10,

11].

Single-phase viscous flow in pipes can be laminar (i.e., smooth and stable) at low Reynolds numbers, transitional from laminar to turbulent at intermediate Reynolds numbers, and turbulent (i.e., pulsating) at high Reynolds numbers. The type of flow regime that develops depends on the geometry of the pipe (i.e., bends, which can be sharp or moderate, and the cross-sectional shape—circular, square, elliptical, rectangular, etc.), the properties of the fluid, flow parameters in the system, as well as the roughness and stiffness of the pipe wall.

In addition to the need to redirect flow through curved sections, many pipeline systems may have branches and junctions that serve to distribute the flow. This applies to the transportation of oil and gas through pipelines from the production well to the refinery, cold water in the cooling system of nuclear reactors, air in the respiratory system, blood in the cardiovascular system of mammals, non-Newtonian fluids in food processing, and many other processes.

While liquids are generally considered incompressible, the transportation of gas (and air) requires taking compressibility effects into account. The discussion above demonstrates how the flow regime depends on a variety of conditions, which overall complicates the accurate description of flow in pipes, pipeline systems, and their components.

At the interface between deformable pipelines and viscous fluid, under certain ratios of physicomechanical parameters, Stoneley waves can appear [

12,

13]. In a waveguide cylindrical shell, which represents a hollow cylinder filled with fluid, two surface waves must exist: one near the outer free surface of the cylinder and the other on the “fluid–elastic body” contact surface. However, data on the dispersion properties of composite waveguides [

14,

15] indicate that these localized wave motions can be quite complex. In the case of wave propagation in viscoelastic cylindrical waveguides, all the obtained eigenvalues and eigenmodes are complex. The real and imaginary parts of the eigenfrequencies are examined. The imaginary parts of the eigenfrequencies begin to branch at certain values of the wavenumbers. It has been found that motion in the cylindrical shell becomes localized on the shell surface. The intensity of localization depends on the viscous properties of the fluid. If the localization intensity decreases, then starting from a certain wavenumber, aperiodic motions occur in the shell filled with a viscous fluid.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Statement and Solution Approach

Consider an infinitely long polymer pipeline, modeled as a viscoelastic cylindrical shell with a radius

R, constant wall thickness

, density

, and Poisson’s ratio

, filled with a viscous fluid of density

in the equilibrium state. The vibrations of such a shell under loads, whose densities are denoted as

p1 ,

p2 ,

pn can be described, following [

16,

17], by the equations:

Here, is the displacement vector of points on the middle surface of the shell. For Kirchhoff–Love shells, it has three components. In addition to axial, circumferential, and normal displacements, it also includes the rotation angles of the normal to the middle surface in the axial and circumferential directions; is the displacement vector of the fluid with axial, circumferential, and radial components, respectively (the “+” sign before pnp_npn and the “–“ sign before the last component of the inertial term indicate that a positive displacement is considered in the direction toward the center of curvature); is the relaxation kernel, and is the instantaneous elastic modulus.

The vibration amplitudes are assumed to be small, which allows the main relations to be written within the framework of linear theory. The system of linearized equations of motion for a viscous barotropic fluid can be expressed as [

18]:

Here, in equations (2), = is the velocity vector of the fluid particles; and P are the perturbations of density and pressure in the fluid; and а0 are the density and the speed of sound in the fluid at rest; are the kinematic and dynamic viscosity coefficients; for the second viscosity coefficient the relation =is adopted; are the components of the stress tensor in the fluid.

Equations (2), together with the corresponding kinematic and dynamic boundary conditions, will be satisfied on the middle surface (r=R), as appropriate for a thin-walled shell. Relations (1) and (2) form a closed system of hydro-viscoelasticity equations for a cylindrical shell containing a viscous compressible fluid. Thus, for shells obeying the Kirchhoff–Love hypothesis, the coupled vibrations of the shell and the fluid must be analyzed—either harmonic in the axial coordinate z and exponentially decaying in time, or harmonic in time and decaying along z.

2.2. Solution Methodology

We assume that the integral terms in (1) are small; therefore, the function

can be represented in the form

where

is a slowly varying function of time, and

is a real constant. Then, applying the

“freezing” procedure [

19], the integro-differential equation (1) can be rewritten in the following form:

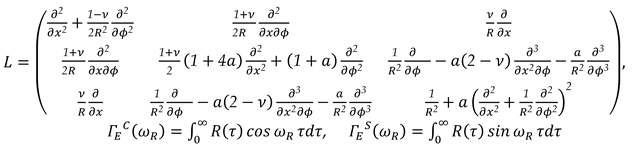

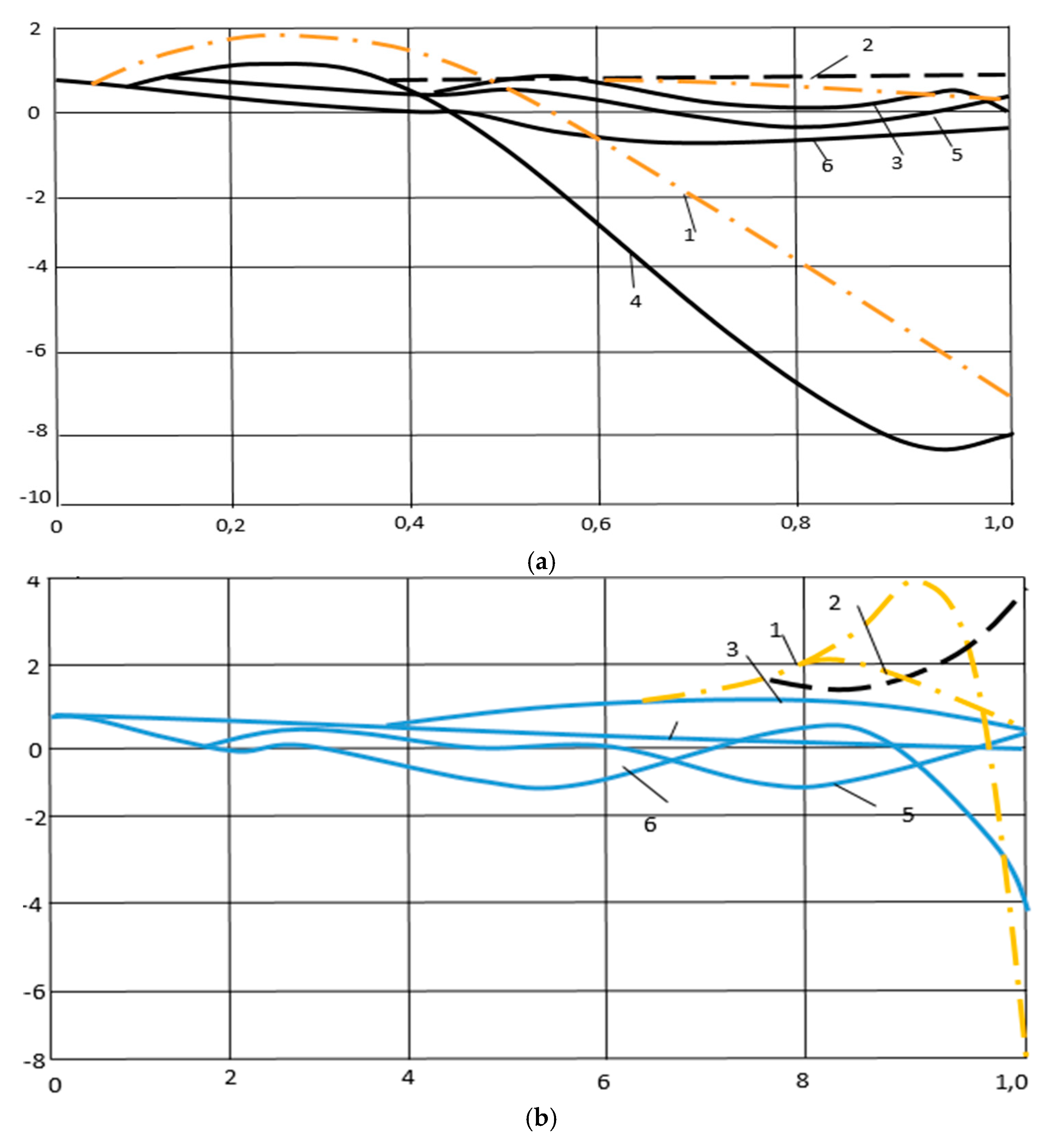

where, for Kirchhoff–Love shells,

— respectively, the cosine and sine Fourier transforms of the material’s relaxation kernel. As an example of a viscoelastic material, we take a three-parameter relaxation kernel

where ρ is the density of the shell material, E is the Young’s modulus, and ν is the Poisson’s ratio.

We now introduce the dimensionless axial coordinate and multiply system (3) by R2. Expanding equations (2) and (3) in coordinate form, it is easy to see that relations (2) and (3) split into independent boundary-value problems:

— longitudinal and transverse vibrations:

Let the wave process be periodic in

z and decaying in time. Then a real wavenumber k is prescribed, while the complex frequency is the desired eigenvalue. The solutions of the boundary-value problems (2)–(5) for the main unknowns, which satisfy the above constraints on their dependence on time and the axial coordinate

z, should be sought in the form [

19,

20]:

where .

Expression (6) can be written in the form

where ,,, ,,,are amplitude complex vector functions; k is the wavenumber; C is the phase velocity; ω is the complex frequency; m is the circumferential wavenumber (the number of circumferential waves), taking values m=1,2,3,…m = 1, 2, 3, ….

The case m=0 corresponds to axisymmetric vibrations. This approach makes it possible to seek the solution of the problem independently for each fixed value of the circumferential wavenumber mmm. Thus, C, k, and ω are unknown real and complex spectral parameters, depending on the type of problem. To clarify their physical meaning, we consider two cases:

- 1.

; C = CR +iCi. In this case, solution (6) has the form of a sinusoid in x, whose amplitude decays in time.

- 2.

; C = CR. Then, at each point x, the oscillations are steady, but they decay along the x-direction.

In the axisymmetric case, the conditions , =0 must hold on the axis r=0.If the outer surface г=R is assumed to be fixed, then ur=uz=uφ=0.

A superposition of solutions of the form (6) yields a standing wave that decays exponentially in time, describing the natural vibrations of a finite-length fluid–shell system with boundary conditions. For an infinitely long shell, by analogy with this type of motion (6), we refer to such oscillations as natural or free vibrations.

In the case of a time-stationary process that decays along the coordinate, on the contrary, the real frequency

is known, while the desired quantity is the complex wavenumber

k. Unlike natural vibrations, these oscillations will be referred to as steady-state. The real parts of ω in the first case and of

k in the second case have the physical meaning of the temporal and spatial frequencies of the process, respectively. The imaginary parts correspond to the decay rates of the wave processes in time and along

z, respectively [

13]. The quantity 1/Im(k) is sometimes defined as the propagation length of a decaying wave. In the purely elastic limit, the propagation length is infinite. The degree of decay of a wave process over a time period is characterized by the logarithmic decrement

Similarly, the spatial decrement is given by

It is also possible to introduce the concepts of phase velocities for natural and steady-state motions:

The quantities Cс and Cу have the physical meaning of the zero-state propagation velocities for natural and steady-state vibrations, respectively, and, unlike in the purely elastic (real) case, they do not coincide at the same frequencies.

Two types of vibrations (natural and steady-state) correspond to two different problem statements. In the nonstationary case, these are the Cauchy problem for an infinite shell and a boundary-value problem for a semi-infinite interval of the variable Z [

21].

By substituting solutions (7) into the system of differential equations (2)–(6), we obtain a system of ordinary differential equations with complex coefficients, which is solved using the Godunov orthogonal sweep method in combination with the Müller method [

7] in complex arithmetic. Torsional vibrations of a cylindrical shell containing a viscous fluid were considered in [

8].

2.3. Longitudinal–Transverse Vibrations

Let us consider the longitudinal–transverse natural vibrations of a viscoelastic shell of circular cross-section containing a fluid with viscous properties. The present paper is a continuation of the study conducted in [

4]. The problem formulation is given in [

4], and all notations and equations coincide with those previously introduced.

Examine an infinitely long viscoelastic cylindrical shell of radius

R1 , constant thickness

h, density

, Young’s modulus

, and Poisson’s ratio

. Consider the longitudinal–transverse natural vibrations of a viscoelastic shell of circular cross-section containing a fluid that possesses viscous properties. The problem of longitudinal–transverse natural vibrations of a viscoelastic cylindrical shell containing a viscous fluid reduces to the following system of ordinary differential equations with four equations:

with boundary conditions

Here and are the viscosity coefficients of a Newtonian viscous fluid ( -in the absence of bulk viscosity), is the density, p is the pressure, and C0 is the adiabatic speed of sound in the fluid.

The pressure parameter

p appearing in the first equation (1) is determined from the system of ordinary differential equations through the main unknowns of the viscous fluid and is computed numerically in the course of the calculations.

The spectral problem (1)– (2), as in the case of longitudinal–transverse vibrations, is solved using the orthogonal sweep method.

In [

4], for solving the frequency equation with a complex parameter in the case of torsional vibrations, Müller’s method is applied. In the present work, Müller’s method is also used to solve the frequency equation for longitudinal–transverse vibrations obtained by the orthogonal sweep method. Several frequency modes of complex natural vibrations are determined depending on various parameters. In addition, based on the Gauss method, the corresponding vibration modes of the cylindrical shell filled with a viscous fluid are constructed.

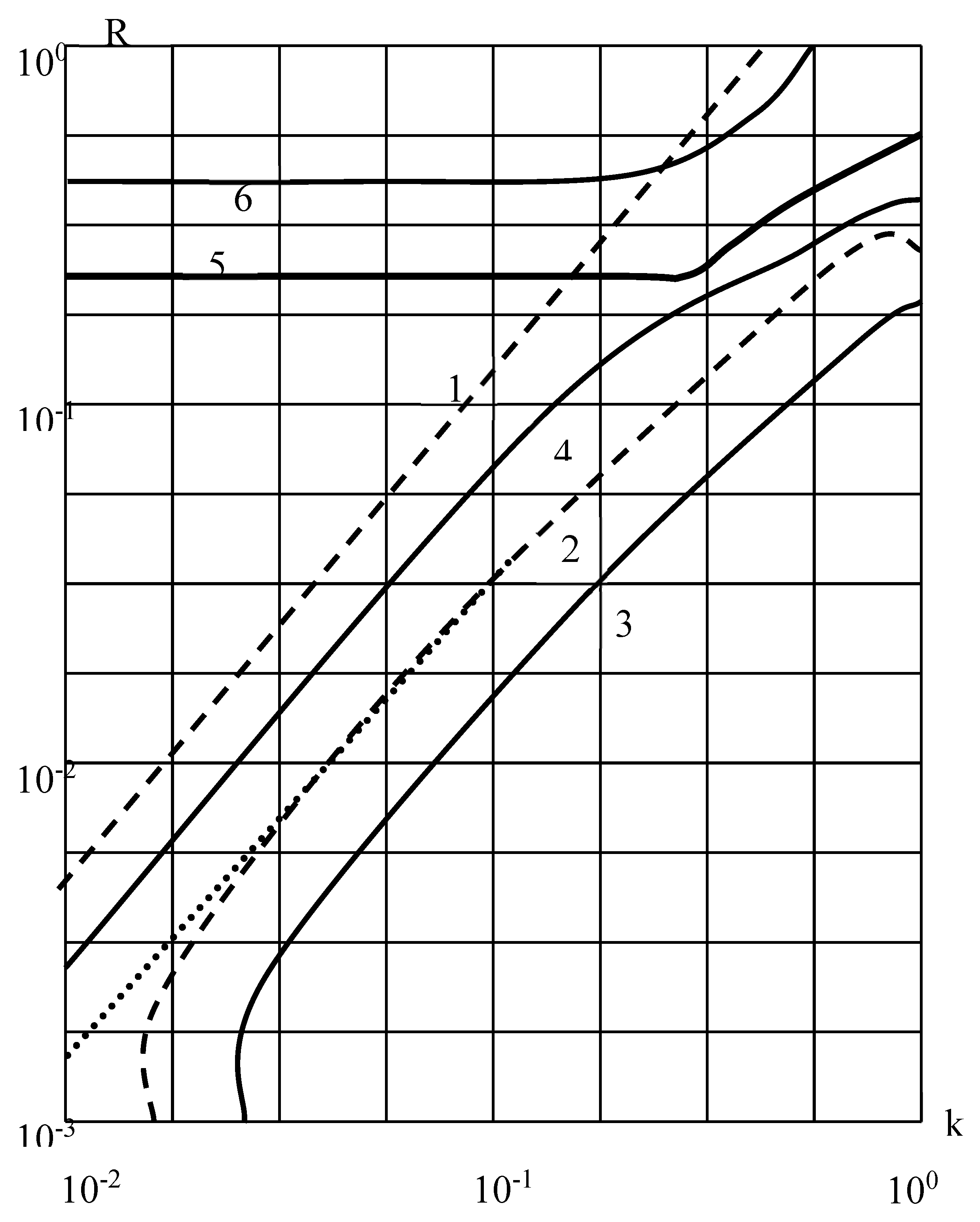

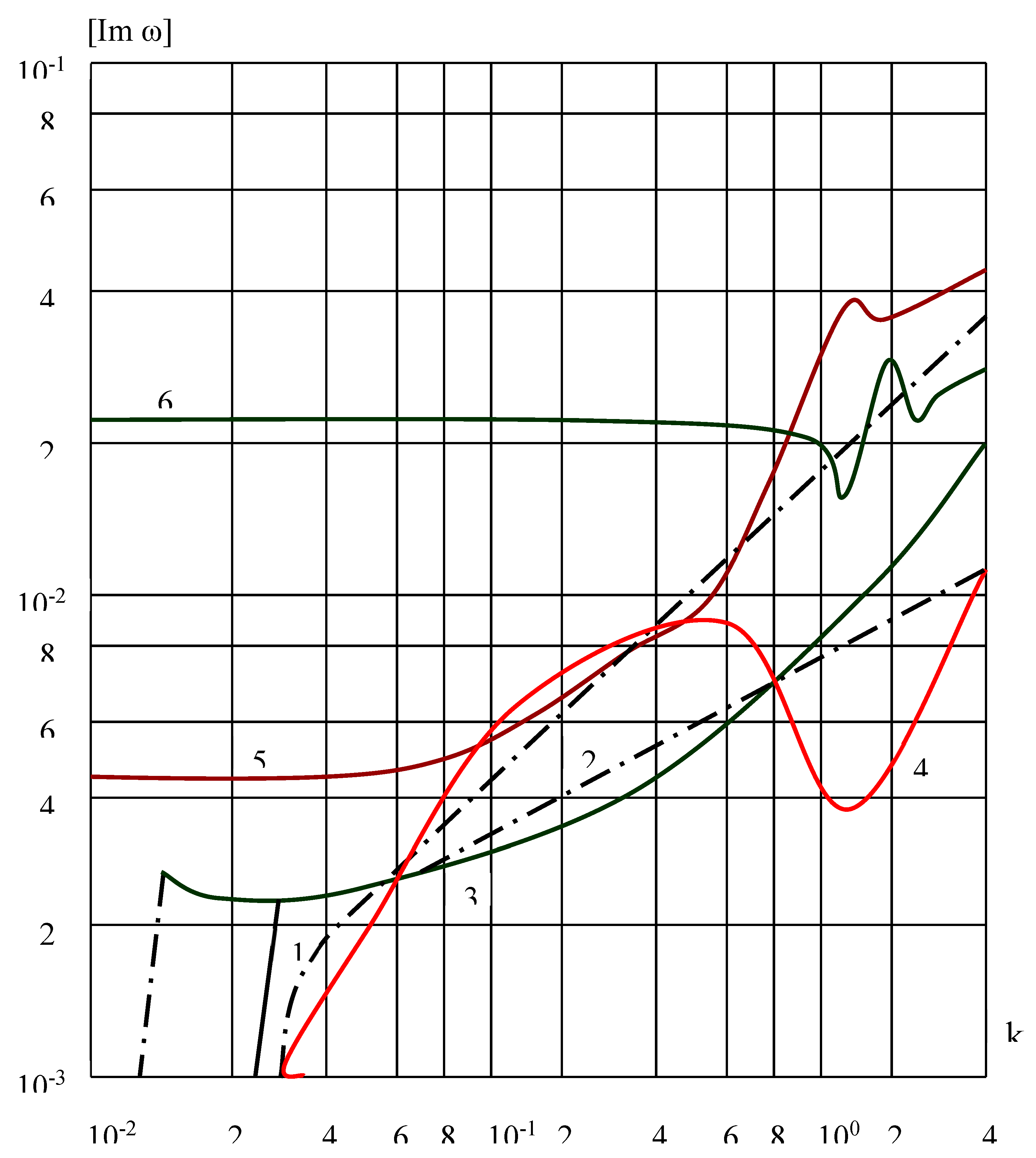

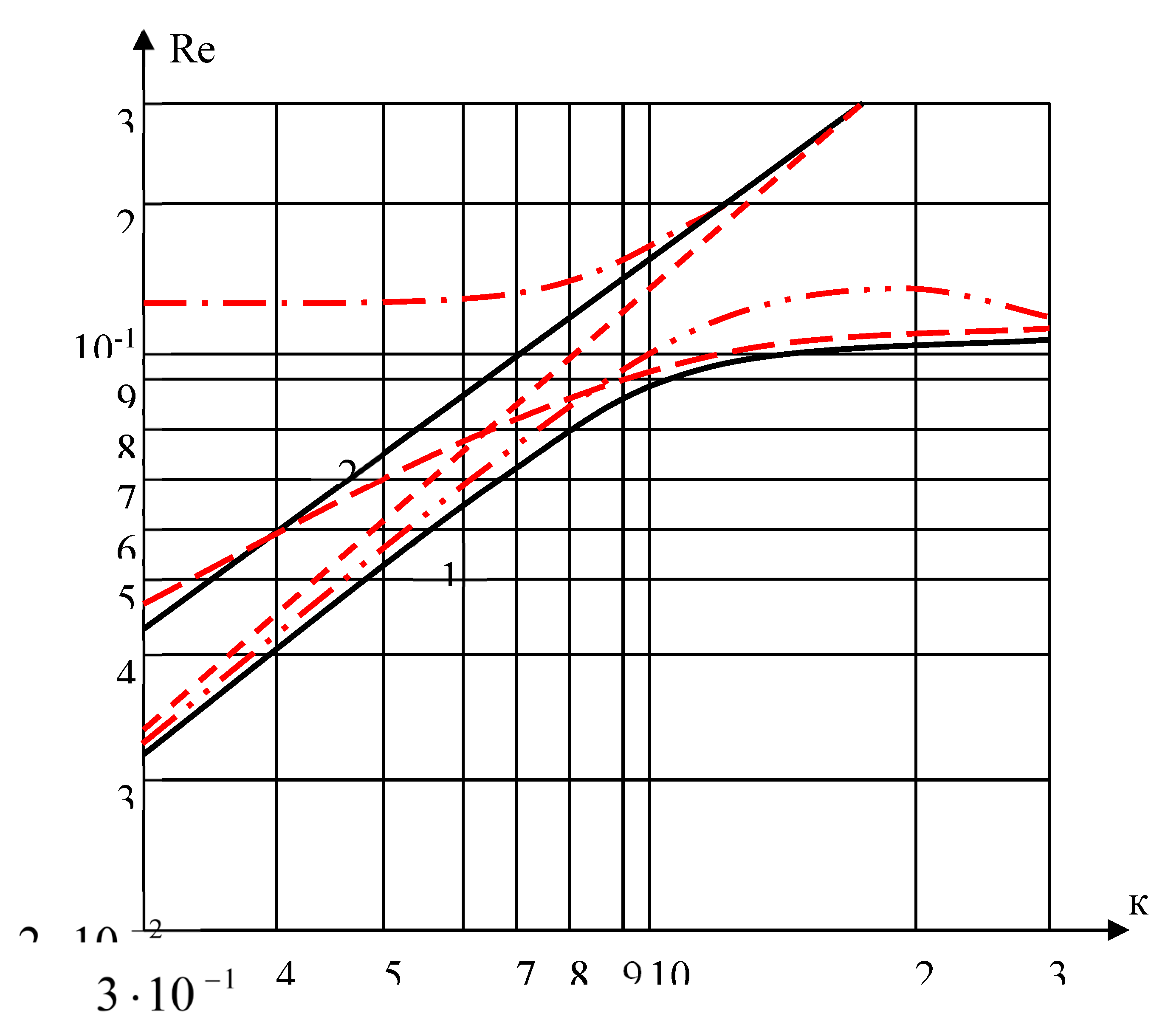

Let us examine the natural vibrations of a cylindrical shell with viscous fluid based on the system of ordinary differential equations (1)–(3). The dispersion relations, represented as complex functions, are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Figure 1 shows the change in the real part (

) of the complex frequency as a function of the wavenumber

k for a compressible fluid (C

0=0.1- solid lines) and an incompressible fluid

(

-dashed–dotted lines). The corresponding eigenmodes of vibrations for

k=0, 1 and

k=2 are shown in

Figure 3. For the cylindrical shell, the relaxation kernel is taken in the form

where А=0.01;

. For calculating the cylindrical shell with viscous fluid, the following parameter values are used:

In the computations, all parameters (lengths, time, and mass densities) appearing in equation (1) are reduced to a dimensionless form ().

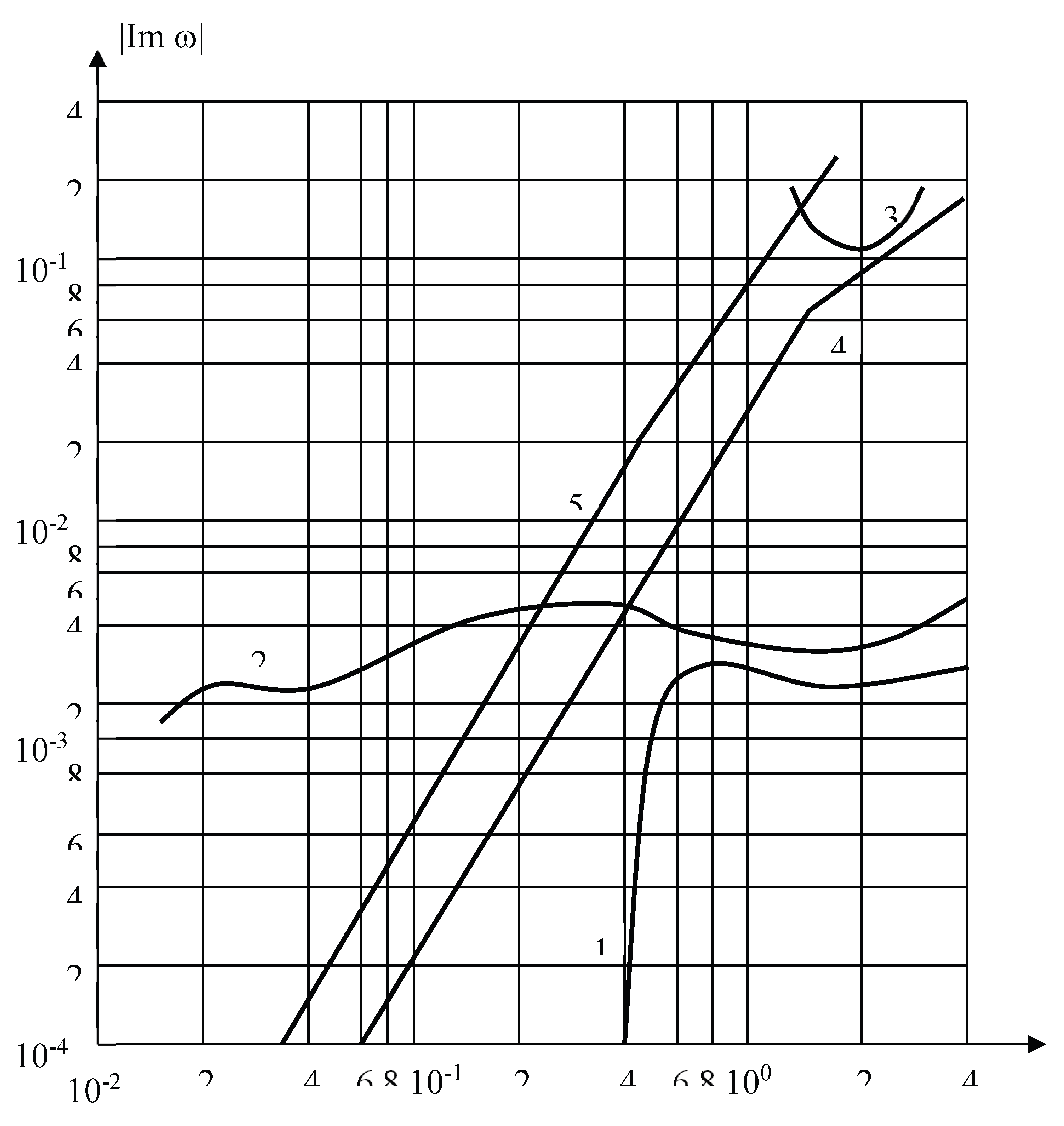

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the dispersion relations for a cylindrical shell with incompressible and compressible fluid. For the incompressible fluid, two modes are identified, which predominantly correspond to the longitudinal (curve 1) and transverse (curve 2) vibrations of the cylindrical shell.

From the dispersion equation, infinitely many imaginary roots can be obtained, corresponding to aperiodic motions. The dashed lines 1 and 2 in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, as well as the dotted lines, correspond to an ideal incompressible fluid.

It should be noted that the dispersion relations for a shell with viscous fluid and for a shell without fluid, for a given shell density

, remain valid for longitudinal vibrations of the shell over the entire range of wavenumber variation. When the viscosity of both the fluid and the shell is taken into account, the corresponding real parts of the eigenfrequencies decrease by up to 17%.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 above show four modes of the real and imaginary parts of natural frequencies (curves 3, 4, 5, 6).

In the case where the shell and the liquid have viscous properties, then the real and imaginary parts of the natural frequencies increase monotonically depending on the wave number, i.e., the mechanical system is dissipative-homogeneous [

11]. When considering the viscous properties of a liquid, the corresponding natural frequencies decrease due to the appearance of a boundary layer.

When the shell is elastic, the corresponding relaxation kernel is zero, then the imaginary parts of the natural frequencies of mechanical systems (cylindrical shell with liquid) change non-monotonically (

Figure 2). The previously discovered “Troyanovsky-Safarov” mechanical effect [

12,

13] for dissipative-inhomogeneous mechanical systems has been confirmed. In the works [

14,

15,

22], the natural frequencies of an elastic cylindrical shell with an ideal fluid were found. The dispersion equations of a cylindrical shell with a viscous fluid have a countable set of complex roots.

It is known that in the torsional oscillations of a cylindrical shell with incompressible fluid, there are two real modes, and in the longitudinal - transverse oscillations of a cylindrical shell with incompressible fluid - an unlimited number of modes of oscillations.

Figure 4 shows the dispersion curves (1,2) for dissipative-inhomogeneous mechanical systems with the following shell and liquid parameters:

. The viscous properties of the shell coincide with the accepted ones above. In

Figure 4, the real parts of the complex frequency are marked with solid lines, and the imaginary parts of the frequency are marked with dashed lines. Two-point dashed lines correspond to the vibrations of the dry shell.

Figure 5 shows the dispersion curves for dissipative-inhomogeneous mechanical systems with the following shell and liquid parameters:

.

Let the partial frequencies of the longitudinal and transverse oscillations of a cylindrical shell with an ideal fluid intersect at density = 8 and v* = 0. At v*, lying near the intersection point of the imaginary parts of the frequency, it turns out, both modes of oscillation are strongly influenced.

Thus, the oscillations of structurally inhomogeneous mechanical systems with similar modes lead to energy intensity, which is expressed in the “Troyanovsky-Safarov” synergistic effect.

Comparison of the obtained results with the results obtained from works [

23,

24], with the same system parameters, differs up to 8%.

3. Results

The numerical solution of the coupled hydro–viscoelastic problem yields dispersion relations in the form of complex eigenfrequencies as functions of the axial wavenumber

. The results, presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, reveal the main features of wave propagation, attenuation, and modal interaction in the shell–fluid system.

Figure 1 demonstrates the dependence of the real part of the complex frequency

on the wavenumber

for compressible and incompressible fluids. For a compressible fluid, the dispersion curves are smooth and monotonic, whereas for an incompressible fluid, two clearly separated branches are observed. The first branch corresponds mainly to longitudinal vibrations of the shell, while the second branch is associated with transverse vibrations. At small values of

, the frequencies are primarily governed by the global stiffness of the coupled shell–fluid system. With increasing

, bending effects become dominant, resulting in a more rapid growth of

,particularly for transverse-dominated modes.

Figure 2 presents the imaginary part of the complex frequency

as a function of the wavenumber, which characterizes temporal damping. When both the shell and the fluid exhibit viscous properties,

increases monotonically with

, indicating dissipative-homogeneous behavior of the mechanical system and stronger attenuation at higher spatial frequencies. In contrast, for an elastic shell interacting with a viscous fluid, the imaginary part varies non-monotonically with

, reflecting complex energy exchange mechanisms between the shell and the fluid that are absent in purely elastic or purely viscous models.

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b show the real part of the frequency for different shell radii, demonstrating that an increase in radius shifts the dispersion curves downward due to reduced structural stiffness, while the qualitative modal structure remains unchanged.

Figure 4 compares dispersion curves of a shell filled with an incompressible viscous fluid and a dry shell, where solid lines denote the real parts of the frequency and dashed lines represent the imaginary parts. The presence of fluid leads to a noticeable reduction in the real part of the eigenfrequencies and a significant increase in attenuation, with these effects becoming more pronounced at larger wavenumbers.

Figure 5 illustrates the behavior of the imaginary part of the frequency near the intersection of longitudinal and transverse modes, where both modes are strongly affected and a sharp increase in attenuation is observed, indicating intensive energy dissipation in the coupled system. Quantitatively, accounting for both shell viscoelasticity and fluid viscosity results in a reduction of the real part of the eigenfrequencies by up to 17 percent compared to the purely elastic case. Comparison with available reference results shows deviations not exceeding 8 percent, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the numerical procedur

4. Discussion

The obtained results provide a detailed insight into the dynamic behaviour of viscoelastic cylindrical shells interacting with viscous fluids. The analysis demonstrates that the combined effects of shell viscoelasticity and fluid viscosity fundamentally alter both wave propagation and attenuation characteristics compared to classical elastic models.

One of the key observations is the monotonic growth of the imaginary part of the eigenfrequency when both the shell and the fluid exhibit dissipative properties. This behaviour indicates that the mechanical system does not exhibit internal resonance or instability within the considered parameter range. Instead, energy dissipation increases steadily with increasing spatial frequency, which is a desirable feature for applications involving vibration suppression and noise reduction.

The reduction of the real part of the eigenfrequencies due to viscoelastic effects highlights the importance of accounting for material memory in polymer pipelines and similar structures. Neglecting viscoelasticity can lead to overestimation of natural frequencies and, consequently, unsafe design assumptions, especially in systems operating at medium and high frequencies.

The comparison between compressible and incompressible fluid models shows that compressibility plays a critical role in determining the number and nature of propagating modes. Compressible fluids introduce additional acoustic-type modes, which interact with structural vibrations and lead to more complex dispersion patterns. In practical terms, this means that pressure wave effects cannot be ignored in high-speed flow or transient loading conditions.

The non-monotonic behavior of attenuation observed in elastic shells with viscous fluids confirms the presence of the Troyanovsky–Safarov effect, previously reported for dissipative-inhomogeneous mechanical systems. The present results extend this effect to viscoelastic shells and show that it persists even when both constituents of the system contribute to dissipation. This synergistic interaction leads to localized amplification of damping near mode intersection points, where longitudinal and transverse modes strongly interact.

From a physical standpoint, these intersections correspond to energy exchange between different deformation mechanisms. Near such points, small changes in material or fluid parameters can result in significant variations in attenuation, which should be carefully considered in design and control applications.

The observed boundary-layer effects emphasize the role of fluid viscosity in modifying the effective dynamic stiffness of the shell. Even relatively small viscosity values lead to noticeable changes in attenuation and mode shapes, particularly for higher modes. This finding is especially relevant for polymer pipelines transporting highly viscous fluids, where neglecting fluid viscosity may lead to inaccurate predictions of vibration decay.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the dynamic response of fluid-filled viscoelastic shells cannot be adequately described by simplified elastic or inviscid models. Accurate prediction of natural frequencies, wave propagation velocities, and damping characteristics requires a fully coupled hydro–viscoelastic formulation.

These findings provide a solid theoretical basis for further studies on finite-length shells, transient wave processes, and stability analysis under dynamic loading. They also offer practical guidance for the design of pipeline systems, vibration isolation components, and shell structures operating in fluid environments where both material memory and fluid viscosity are significant.

5. Conclusions

1. Analyzing the dependence of energy dissipation on the wave number, it should be noted that there are two opposite trends: with the growth of the wave number at a fixed amplitude v, the tangential stresses рzφ increase linearly, and, as the numerical results show, simultaneously, the localization of the fluid movement amplitudes near the shell occurs, as a result of which the mass of the fluid involved in the movement, as well as the tangential stresses рrφ, decrease.

2. For low viscosity, the frequencies Re k of both modes are close to each other in the low-frequency region, and at high frequencies, the phase velocity Cу of the first mode tends to the velocity of the dry shell. The damping coefficients increase linearly, and for the second mode, this coefficient is always greater than for the first. In the case of greater viscosity, the frequency Rek2,1 is significantly greater than the frequency Rek2,2 across the entire ω-variation range, and the phase velocity Cу tends to infinity with increasing C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology were carried out by Ruziyev Tulkin. Software development and validation were performed by Safarov Ismoil. Formal analysis and investigation were conducted by Teshayev Mukhsin. Resources and data curation were provided by Rakhmanov Bahodir. The original draft was written by Ruziyev Tulkin, while review and editing were handled by Teshayev Mukhsin. Visualization was prepared by Marasulov Abdurakhim. Supervision was provided by Ablokulov Sherzod. Project administration was managed by Safarov Ismoil, and funding acquisition was secured by Nurova Firuza. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Contributions are defined in accordance with the CRediT taxonomy, and authorship is limited to those who made substantial contributions to the reported work.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was not funded by any organization.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the institutional support provided by Tashkent Chemical-Technological Institute; the Bukhara Branch of the V.I. Romanovsky Institute of Mathematics of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan; Bukhara State Technical University; Bukhara State Pedagogical Institute; Urgench State University; and the International Kazakh-Turk University named after Khoja Ahmed Yassawi. The authors also thank colleagues and staff for administrative and technical assistance that supported the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abukhalifeh, H.; Lohi, A.; Upreti, S.R. A Novel Technique to Determine Concentration-Dependent Solvent Dispersion in Vapex. Energies 2009, 2, 851–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ke, W.; Kong, D.; Wu, K.; Chen, Z. Non-Newtonian Flow Characteristics of Heavy Oil in the Bohai Bay Oilfield: Experimental and Simulation Studies. Energies 2017, 10, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, V.; Chowdari, G.S.; Reddy, K.S.; Chattaraj, R. A predictive model for estimating the viscosity of short-term-aged bitumen. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2016, 19, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadloo, M. S. Application of support vector machines for accurate prediction of convection heat transfer coefficient of nanofluids through circular pipes. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow 2020, 31(8), 2660–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowane, A.J.; Babu, V.M.; Rokni, H.B.; Moore, J.D.; Gavaises, M.; Wensing, M.; Gupta, A.; McHugh, M.A. Effect of Composition, Temperature, and Pressure on the Viscosities and Densities of Three Diesel Fuels. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 5529–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giwa, S.O.; Sharifpur, M.; Goodarzi, M.; Alsulami, H.; Meyer, J.P. Influence of base fluid, temperature, and concentration on the thermophysical properties of hybrid nanofluids of alumina—Ferrofluid: experimental data, modeling through enhanced ANN, ANFIS, and curve fitting. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 143, 4149–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehring, R.; Hess, R.W.; Kamionski, M. The heavy oil resources of the United States; Rand Corporation, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Durdiyev, D.; Safarov, I.; Teshaev, M. Propagation of Waves in a Fluid in a Thin Elastic Cylindrical Shell. WSEAS Trans. Fluid Mech. 2024, 19, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz’, A.N. Wave propagation in a cylindrical shell containing a viscous compressible liquid. Int. Appl. Mech. 1980, 16, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alade, O.; Ademodi, B.; Sasaki, K.; Sugai, Y.; Kumasaka, J.; Ogunlaja, A. Development of models to predict the viscosity of a compressed Nigerian bitumen and rheological property of its emulsions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 145, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.; Akhmedov, A.; Adilova, S. Theoretical and engineering solutions of the controlled vibration mechanisms for precision engineering. AIP Conference Proceedings 2022, 2637, 060001. [Google Scholar]

- Safarov, I.I.; Teshaev, M.Kh. Unsteady Motions of Spherical Shells in a Viscoelastic Medium. Tomsk State University. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 2023, 83, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarov, I.; Teshaev, M.; Romanovsky, V.I.; Institute of Mathematics. Dynamic damping of vibrations of a solid body mounted on viscoelastic supports. Izv. VUZ. Appl. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 31, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarov, I.; Teshaev, M. Control of resonant oscillations of viscoelastic systems. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2024, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarova, G. L. Propagation of normal axisymmetric waves in elastic cylinders made of compliant materials, filled with and surrounded by a fluid. Applied Mechanics 2004, 40(5), 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Vasin, S. V.; Tamurov, N. G. Influence of viscous fluid compressibility on the natural vibrations of an elastic cylindrical shell interacting with a fluid. Applied Mechanics 1983, 19(7), 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bagno, A.M. Propagation of longitudinal waves in a prestressed compressible cylinder containing a liquid. Int. Appl. Mech. 1980, 16, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaev, I.; Shomurodov, J. Wave processes in an extended underground pipeline interacting with soil according to a bilinear model. AIP Conference Proceedings 2022, 2432, 030049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardonov, B.M.; Mirzaev, I.; Hojmetov, G.H.; An, E.V. Theoretical Values of the Interaction Parameters of the Underground Pipeline with the Soil. AIP Conference Proceedings 2022, 2637, 030009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudainazarov, S.; Mavlanov, T.; Umarova, F.; Sabirjanov, T. The natural vibrations of shell structures taking into account dissipative properties and structural heterogeneity. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 402, 07023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusanov, K. Selecting Control Parameters of Mechanical Systems with Servoconstraints. E3S Web of Conferences 2021, 264, 04085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusanov, K. Stabilization of mechanical system wich nonholonomic servo-constraints. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 883, 012164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdiev, D.K.; Totieva, Z.D. The problem of determining the one-dimensional kernel of viscoelasticity equation with a source of explosive type. JIIP 2019, 28, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdiev, D.K.; Totieva, Z.D. The problem of determining the one-dimensional matrix kernel of the system of viscoelasticity equations. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 8019–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).