1. Introduction: From Neglected Zoonosis to Global Health Emergency

The recent (2003) advent of monkeypox as a threat to public health worldwide, and its dissemination in 2022 demonstrates an evolutionary transition of orthopoxvirus epidemiology and transmission dynamics. In this region, MPXV was first detected in laboratory monkeys in 1958 and in humans (a groomer applying monkey skinning) in 1970 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], though had thus far over >50 years been relatively static throughout Central and West Africa with occasional outbreaks typified by limited human-to-human transmission through contacts often related to contact with animals. The 2022 epidemic broke with the past, and with sustained human-to-human transmission in over 120 countries, has resulted in more than 100000 laboratory-confirmed cases reported worldwide by August, 2024 [

3]. These epidemiological changes have been paralleled by characteristic virological and clinical transitions. The current circulating Clade IIb strain contains specific genetic signatures indicating rapid human adaptation, as disease presentations have transformed from traditional centrifugal rashes to mostly anogenital lesions, especially among MSM [

4,

5]. Finally, diagnostic ability, antiviral treatment and vaccine utilization have changed the therapeutic environment. However, knowledge gaps remain regarding long-term immunity; optimal treatment regimens and resource allocation are not yet available. This integrative review provides a synthesis of the latest evidence in 3 key interrelated domains: (1) Viral evolution and genetic adaptation; (2) Immunopathogenesis and host response; and (3) Clinical management and public health response. In characterizing mpox through this multidimensional lens, we intend to present a holistic framework for consideration of the emerging threat and for discussion of future pandemic preparedness.

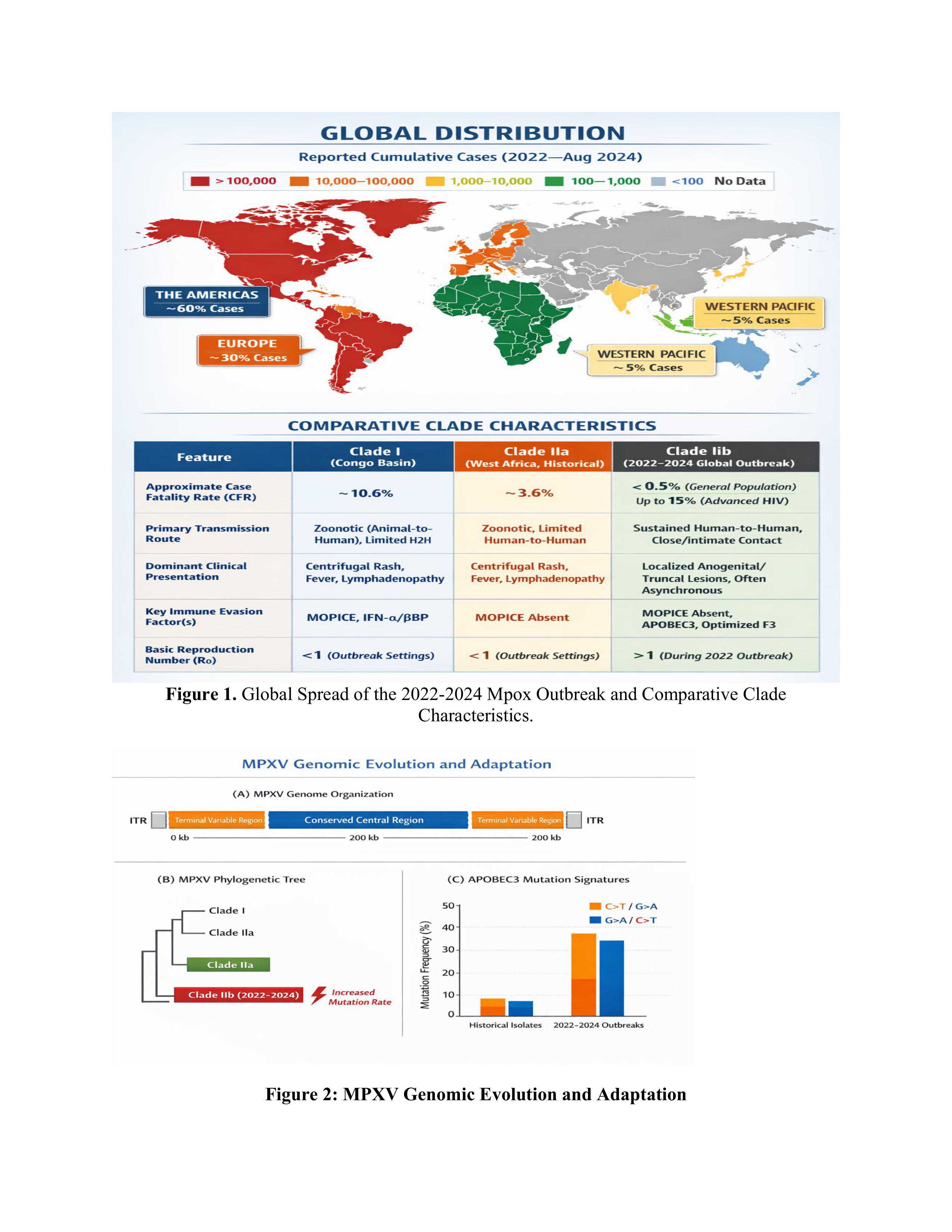

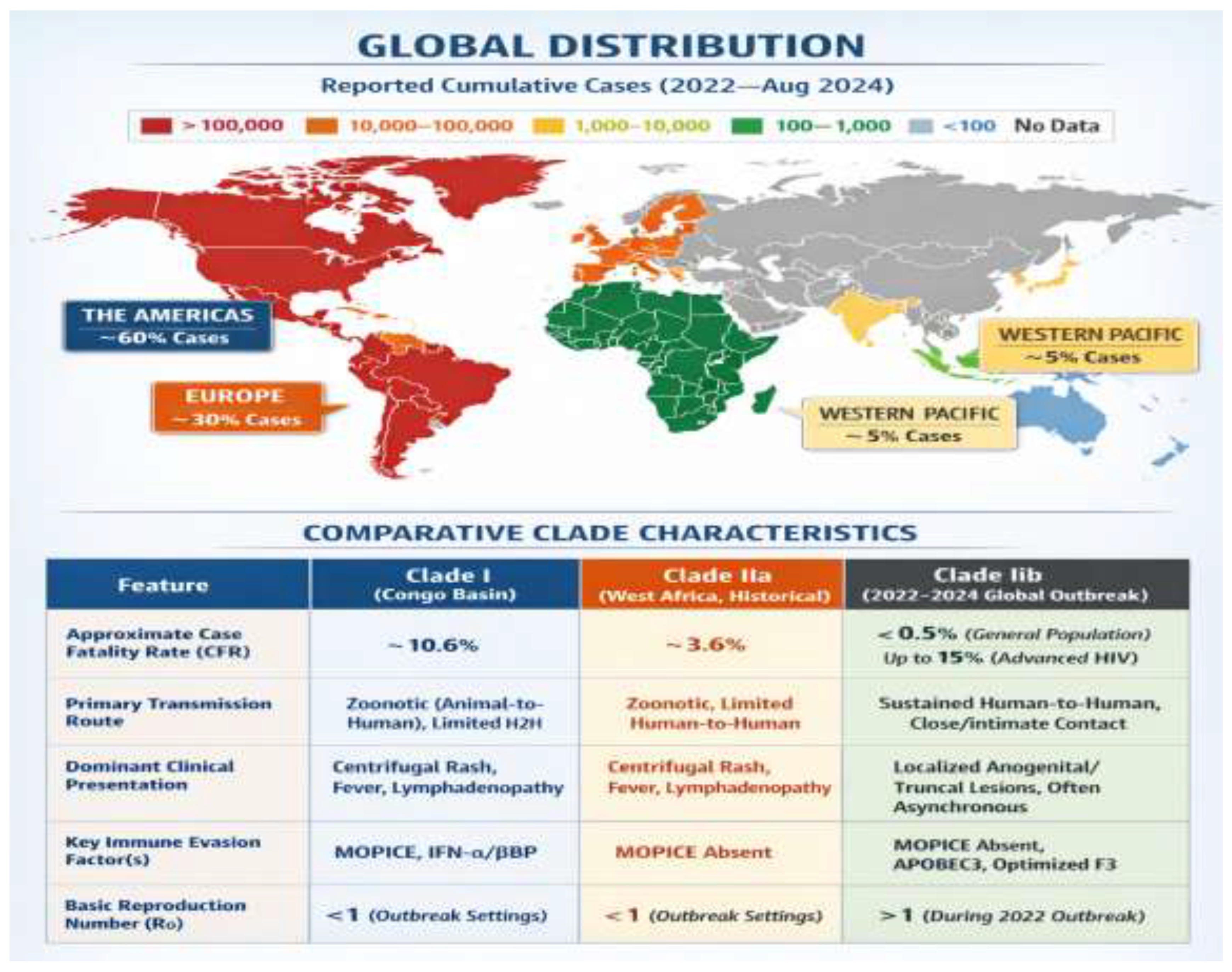

Global distribution of reported mpox cases since 2022 through August 2024, with the Americas and Europe emerging as epicentres of the Clade IIb epidemic bound by now to traditional endemic countries in Africa. (Bottom Panel) Comparative table between the main MPXV clades, showing the various virological and epidemiological changes of globally disseminated Clade IIb with decreased CFR, stable human to human transmission and modified clinical presentation.

2. Viral Evolution and Genetic Adaptation

2.1. Genomic Architecture and Clade Divergence

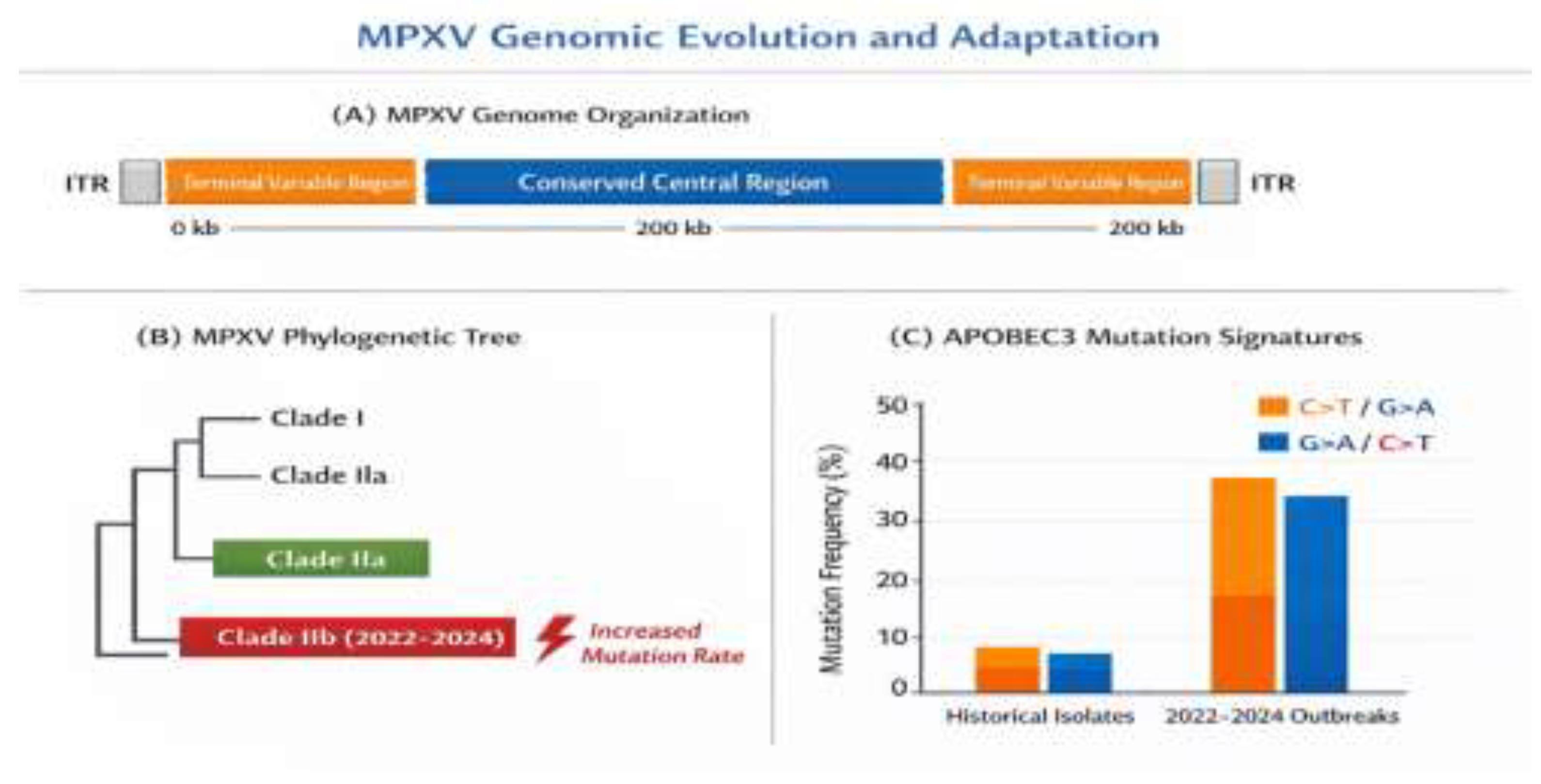

MPXV has a vast (≈197 kb) double-stranded DNA genome that follows the typical Orthopoxvirus structure pattern: a conserved central core flanked by variable terminal regions that contain inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) (

Figure 1A). A 385 kbp central region (≈101 kb, between C10L and A25R ORFs) is 96.3% identical to variola virus and houses genes for the core structural proteins and replication machinery [

6]. On the other hand, the extremities possess clade-specific virulence genes and host range determinants that are widely different between clades.

Two major clades of MPXV have traditionally been identified, the Central African (Clade I) clade from the Congo Basin with case fatality rates (CFR) of 10.6% and the West African (Clade II) clade with CFR of 3.6% [

7]. The 2022 worldwide epidemic was caused by a Clade II offspring, referred to as Clade IIb, which presents characteristic evolutionary signatures indicative of rapid human adaptation.

2.2. APOBEC3-Driven Hypermutation and Human Adaptation

Attractive candidates for the 2022 outbreak strains are their high mutation rate (estimated to be ~6-12-fold higher comparing with pre-2022 lineages,

Figure 1B) [

8]. Genomic analysis of 2022–2024 isolates demonstrate typical APOBEC3-mediated mutation signatures, which are associated with 46 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP) exhibiting significant preference for GA>AA (26 substitutions) and TC>TT (15 substitutions) transitions [

9]. Enrichments of mutations in genes encoding immune evasion proteins and host interaction factors indicate intense selective pressure during continued human-to-human transmission. The functional implications of these mutations are complex. Mutations are found in genes coding for: (1) viral envelope proteins necessary to enter cells (A35R, H3L), (2) immune inhibitors (MOPICE, F3), and (3) host range [

10]. This is consistent with comparisons of receptor binding affinity and immunogenicity for closely related H9N2 wildtype and recent variant AIV isolates, where an increased infectivity correlated with reduced antibody reactivity to HA trimers (Guo et al., 2016).

2.3. Evolution of Virulence Factors

Genomic comparisons reveal significant variation in virulence factor repertoire among clades. (2017/01) The Central African clade encodes the Monkeypox Inhibitor of Complement Enzymes (MOPICE), a 24 kDa protein that is secreted and acts as a cofactor for factor I-dependent cleavage of C3b and C4b [

11]. This complement-evasion mechanism is lacking in Clade II strains, which may have led to their reduced virulence. Nevertheless, clade IIb has evolved compensatory mutations within other immune evasion pathways such as increased type I interferon antagonism by F3 protein optimization and enhanced inhibition of apoptosis by the modification to Bcl-2 homologue [

12].

Figure 2.

MPXV Genomic Evolution and Adaptation.

Figure 2.

MPXV Genomic Evolution and Adaptation.

This figure illustrates the genomic evolution and adaptation of the Monkeypox virus (MPXV), highlighting key features across three sections:

(A) MPXV Genome Organization: The figure illustrates the overall organization of the MPXV genome, including two terminal variable regions and central conserved region that is ∼200 kb in length. ITR (Inverted Terminal Repeats) are likewise shown on both termini.

(B) MPXV Phylogenetic Tree: This figure illustrates the genetic relationship of various MPXV clades, with Clade I, Clade IIa and Clade IIb (which occurred during the 2022–24 outbreaks) shown to be related. The 2022-2024 Clade IIb is specifically characterized by a “higher mutation rate” than previous isolates.

(C) APOBEC3 Mutation Signatures: This bar chart displays the frequency of mutations in MPXV genomes that occurred during endemic versus 2022-2024 outbreaks. It illustrates a striking higher frequency of mutations, predominantly in the G>A/C>T substitution signatures (highlighted in orange), during the recent than historical outbreaks. This is suggestive of potential implications of APOBEC3-induced mutations in viral evolution.

3. Immunopathogenesis of Severe Mpox

3.1. Infection Mechanism: Cellular Entry and Dissemination

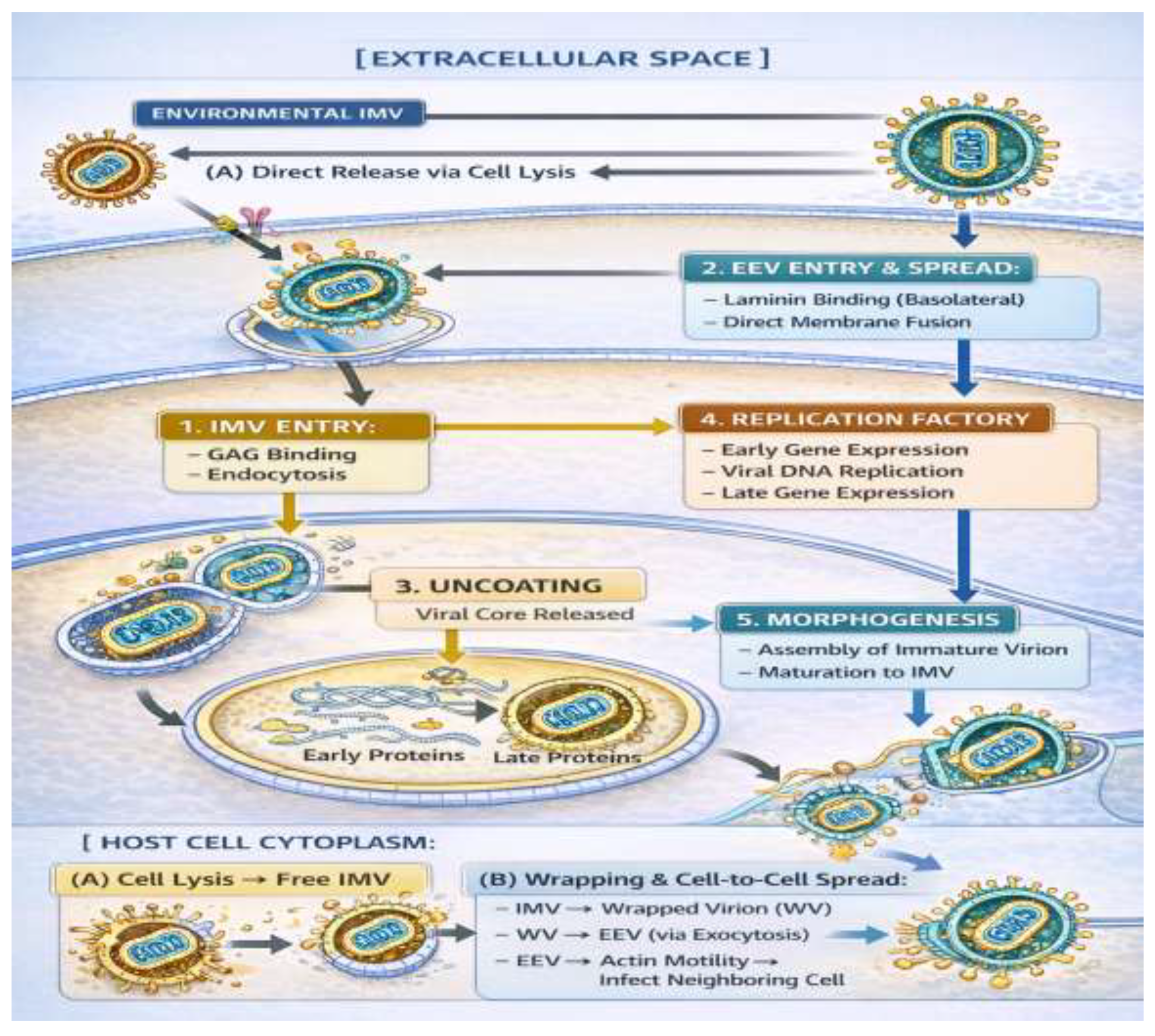

The MPXV infection cycle starts by attachment of viral particles with target cells, and two different infectious virion forms are involved in the process: intercellular mature virions (IMVs) and extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) [

13,

50]. Environmentally stable IMVs are believed to initiate infection by attaching to cell-surface GAGs (e.g., heparan sulphate), and later one or more entry receptors where they elicit macropinocytosis or clathrin-mediated endocytosis [

51,

52]. In the endosome, acidification of the lumen drives fusion between the IMV membrane and that of the endosome, ultimately resulting in release of viral core into the cytoplasm. In contrast, EEVs, which are released from infected cells and important for systemic dissemination, have a second host-derived envelope with viral proteins like A33 or B5. These proteins are responsible for efficient cell-to-cell spread and long-range movement by binding to receptors like laminin present on the basolateral surface of epithelial cells [

53]. The EEV entry route may circumvent the endosomal way and fuse directly at the plasma membrane. It is this duality of entry modes that confers the broad cellular tropism of MPXV, which in addition to keratinocytes and fibroblasts includes immune cells such as mononuclear phagocytes and dendritic cells (which allow initial replication at the site of inoculation and subsequent nodingal or haematogenous dissemination to secondary sites) [

54].

Figure 3.

The Monkeypox Virus (MPXV) Life Cycle within a Host Cell.

Figure 3.

The Monkeypox Virus (MPXV) Life Cycle within a Host Cell.

Schematic representation of the MPXV replication cycle. The virus gains entry by means of two primary pathways: (1) through Intracellular Mature Virion (IMV), by endocytosis, or (2) Extracellular Enveloped Virus (EEV), by direct fusion. Replication takes place in cytoplasmic factories, after uncoating (3). New virions are formed during morphogenesis (5). Mature IMVs are then released from cell lysis for an environmental response or enveloped to form EEVs. EEVs rely on actin-based motility to spread effectively from cell-to-cell (6), an important factor in lesion formation and systemic dissemination. Critical processes, such as apoptosis inhibition (by F1) and innate immune sensing (by F3), may take place at the same time in the infected cell.

3.2. Pathogenic Mechanism: From Cellular Hijacking to Systemic Disease

Upon entry, the viral core makes factories in the cytoplasm and activates a highly controlled transcriptional program. MPXV productively exploits host cell systems to synthesize its DNA and generate virions, all the while expressing elaborate immunomodulatory proteins that undermine the host response to establish an environment favorable for replication [

55]. The inhibition of the host apoptotic response is its pivotal pathogenic feature. Viral proteins, including F1 (a Bcl-2 homolog), are capable of blocking and repressing host pro-apoptotic proteins to avoid apoptotic collapse at a premature point prior to ensuring efficient production of viruses yet maintaining cellular sensibility towards the environment [

12,

56]. At the same time, MPXV ablates essential innate immune signals. The viral dsRNA-binding protein F3 not only sequesters viral PAMPs, but also directly antagonizes the key host kinases including PKR to dampen the ISR and prevent host translation arrest [

14]. With disease pathogenesis, lytic release of virions and viral proteins in concert with secretion of immunomodulating factors set off a damaging cascade. Necrosis and ballooning degeneration of infected epithelial cells occur to cause vesicle and pustule formation. The virus also provokes a strong chemokine response (e.g., CCL2, CXCL8) that attracts monocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes to the lesion inflammatory milieu [

57]. Systemic spread, generally characterized by viraemia, results in secondary sites of infection within the skin, mucous membranes and occasionally organs such as spleen, liver and lung. The disease severity is a consequence of not only direct viral cytopathic effect in tissues, but also an uncontrolled host immune response leading up to pathologic cytokine storm in severe conditions [

21].

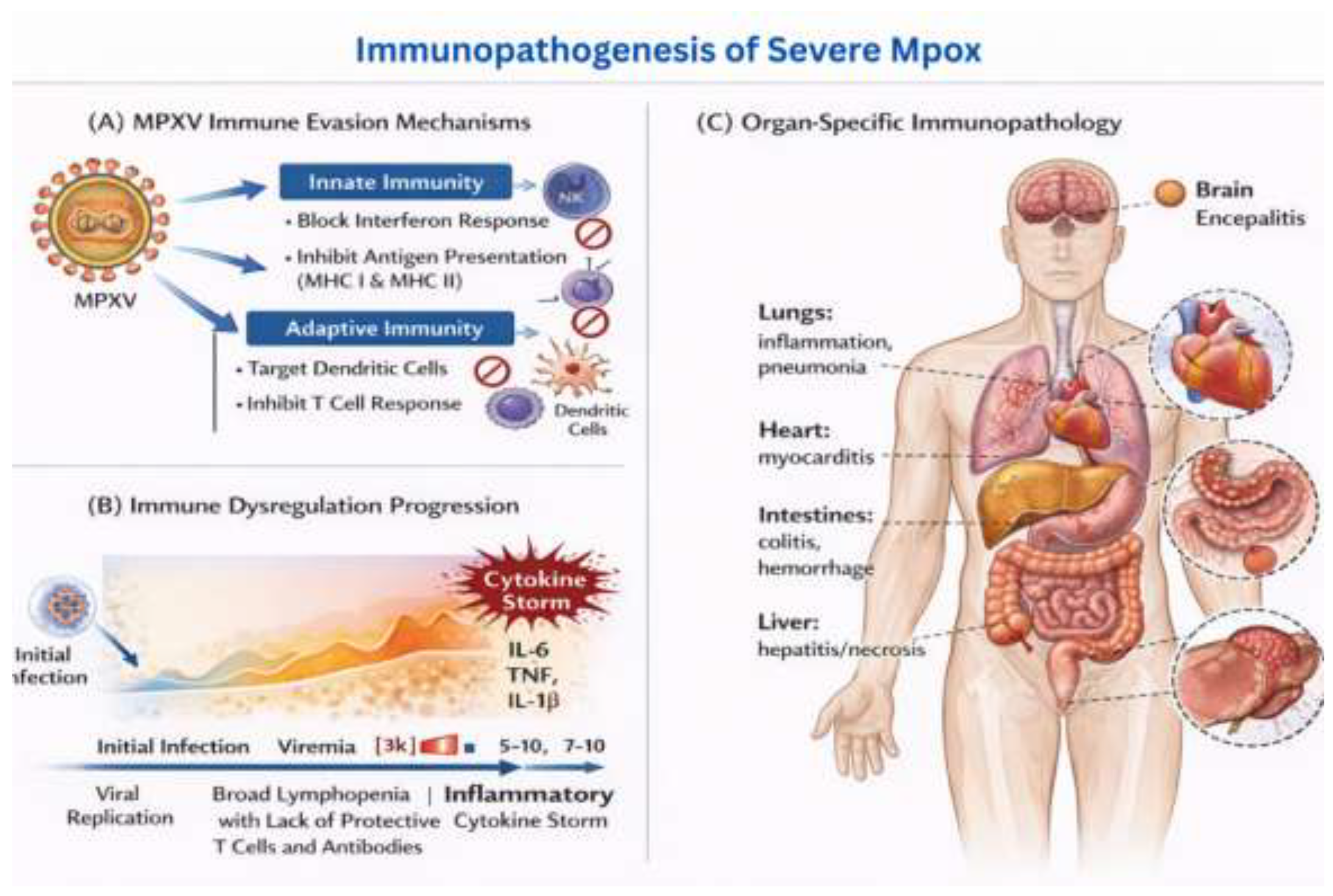

3.3. Viral Entry and Initial Immune Evasion

The MPXV infection is initiated by two distinct types of virions, the intracellular mature virion (IMV) and the extracellular enveloped virion (EEV), that engage different entry routes and trigger dissimilar immune responses [

13]. Initial immune evasion is achieved by a number of viral proteins that inhibit signaling through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (

Figure 2A). F3 protein (homologue of VV E3) is a key player in the innate immune suppression as it binds the viral double-stranded RNA and inhibits activation of PKR, RIG-I and MDA5 [

14]. This inhibition prevents downstream IRF3/7 activation and IFN-stimulated gene induction, leading to an “open” environment for initial viral replication. Moreover, viruses of clade I produce interferon-α/β binding proteins that serve as cytokine decoys and are further responsible for inhibiting antiviral responses [

15].

3.4. Dysregulation of Cellular Immunity

Acute mpox is associated with dramatic derangement of the innate and adaptive cellular immune response. NKT have marked expanded numbers, but with functional impairment including reduced degranulation and decreased cytokine production (IFN-y, TNF-a), disordered chemotaxis (down-modulation of CCR5, CXCR3 and CCR6) [

16]. This NK cell dysfunction correlates with disease severity and longer duration of viral shedding. T cell responses are also impaired through numerous processes. MPXV-infected D dendritic cells shut down MHC class II antigen presentation and chemokine receptor expression, which in turn suppresses T cell homing and activation [

17]. In addition, viral proteins hamper T cell receptor (TCR) signaling via alternate antigen-presenting pathways and consequently impede virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses [

18].

3.5. Complement System Subversion and Antibody Responses

The complement cycle is a key battlefront in MPXV pathogenesis. MOPICE, which is carried by Clade I isolates, itself shows cofactor activity for the factor I mediated cleavage of C3b to iC3b blocking the formation of the C3 convertase and therefore complement activation [

19]. In Clade II infections, strategies of complement evasion include the recruitment of host complement regulatory proteins to the virus envelope. The antibody responses in mpox are complicated and possibly of a double-edged nature. Although neutralizing antibodies are involved in virus clearance [

20], there is accumulating evidence for the phenomenon of ADE, and it may occur under certain conditions. Antistrike orthopoxvirus antibodies present due to prior smallpox vaccination or natural infection might facilitate virus entry into Fc receptor-expressing cells, and could thus account for the increased severity seen in some previously vaccinated subjects.

3.6. Cytokine Storm and End-Organ Damage

The transition to severe illness is also characterized by a relative unbalanced host cytokine production, dominated by a typical switch from Th1 toward Th2 dominance (

Figure 2B). Patients with severe disease have increased IL-2, IL-4, and IL-8 but decreased TNF-α and IL-12 [

21]. This cytokine enlargement contributes to widespread myeloid hyperplasia, thymotic, splenic damage, and multi-organ injury by direct cytopathic effects as well as immunopathologic processes.

Figure 4.

Immunopathogenesis of Severe Mpox.

Figure 4.

Immunopathogenesis of Severe Mpox.

This figure illustrates the immune response and organ-specific immunopathology associated with severe Monkeypox (Mpox) infection.

(A) MPXV Immune Evasion Mechanisms: The diagram highlights how MPXV evades the host’s immune system by targeting both innate and adaptive immune responses. MPXV stops the interferon response, which is an important part of the body’s natural defences. It also inhibits antigen presentation by MHC I and MHC II molecules, which reduces immune cells’ ability to recognise infected cells. Additionally, MPXV targets dendritic cells and inhibits T cell responses, further undermining the immune system’s ability to fight the infection.

(B) Immune Dysregulation Progression: This section shows the progression of immune dysregulation following MPXV infection. The initial infection causes viral replication and viremia (the presence of viruses in the bloodstream). As the infection progresses, it triggers a “cytokine storm” characterised by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β. This inflammatory response contributes to broad lymphopenia (depletion of protective T cells and antibodies), worsening the immune dysfunction and promoting severe inflammation.

(C) Organ-Specific Immunopathology: The final part of the figure shows the effects of severe MPXV infection on different organs of the body. In the lungs, inflammation and pneumonia occur, while the heart may suffer from myocarditis. The intestines experience colitis and haemorrhages, and the liver may develop hepatitis or necrosis. The brain can also be affected, leading to encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), which further complicates the disease’s pathology.

4. Clinical Spectrum and Diagnostic Approaches

4.1. Evolving Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of mpox has undergone significant evolution during the 2022-2024 outbreak (

Table 1). While classic symptoms including fever (91%), rash (96%), and lymphadenopathy (79%) remain prevalent, their distribution and progression have changed substantially.

The most notable difference is the higher rate of anogenital lesions (67%) that can be the first or single manifestation, especially in MSM populations [

22]. This limited presentation has resulted in frequent misdiagnosis for these as routine STIs with a delayed approach to isolation and management. Also, the classical centrifugal rash pattern is not often seen and most patients develop rash mainly on the trunk or localized rashes.

4.2. Special Populations and Risk Stratification

Immunocompromised persons, especially those with advanced HIV (CD4 <200 cells/μL), have more severe and prolonged courses of illness [

23]. These patients have higher prevalence of necrotic lesions, bacterial superinfection and systemic infection such as pneumonia and sepsis. The case fatality rate for these individuals is near 15% as opposed to <0.5% in the immunocompetent [

24]. Other groups with high risk are pregnant women (Vertical transmission: 3-5%), children less than 8 years old and patients with atopic dermatitis or other skin barrier disorders [

25]. These populations merit closely monitoring and early antiviral treatment.

4.3. Diagnostic Modalities and Challenges

PCR examination of material from the lesions continues to be the diagnostic test against which all others are compared, with 97.9% sensitivity and 99.2% specificity [

26]. However, a high-quality sampling technique is essential as swabs from the root of lesions give highly significantly higher viral loads than those from follicular surface. Blood PCR is less sensitive (72.6%) but may be utilized in the viremic stage or in patients without lesions to sample. Serology has little role in the acute disease, as it shows delayed antibody production and cross-reactions between OPVs [

27]. But they have crucial functions in epidemiological monitoring and vaccine immunogenicity evaluations. Point-of-care screening with rapid antigen tests seems to be a promising approach, however their sensitivity is not sufficient at present (70.1%) for routine clinical use.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Performance Characteristics.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Performance Characteristics.

| Test |

Sample Type |

Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

Time to Result |

Best Use Case |

| Lesion PCR |

Swab from base |

97.9% (96.3-99.2) |

99.2% (97.5-100) |

4-24 hours |

Confirmed diagnosis |

| Blood PCR |

Whole blood/plasma |

72.6% (66.0-78.3) |

97.4% (94.0-99.5) |

4-24 hours |

Systemic infection |

| Serology (IgM) |

Serum |

77.4% (69.0-84.6) |

88.3% (81.2-93.8) |

24-48 hours |

Retrospective diagnosis |

| Rapid Antigen |

Lesion exudate |

70.1% (61.9-77.9) |

84.7% (78.0-90.2) |

15-30 minutes |

Field screening |

5. Therapeutic Advances and Management Strategies

5.1. Antiviral Therapeutics: Mechanisms and Efficacy

However, the therapeutic armamentarium for mpox has opened appreciably and a number of agents have shown clinical efficacy (

Table 3). Tecovirimat (ST-246), a small molecule that targets the VP37 envelope wrapping protein is currently the first-line treatment for moderate to severe disease [

28]. Clinical research shows improvement rates of 88% and symptom relief within 4-6 days of use. Notably, tecovirimat seems to be safe also in special populations such as pregnancy or immunocompromised hosts, despite the need for an active surveillance for resistance development. Et-PMPD (Brincidofovir) The lipid-linked prodrug derivative of cidofovir, brincidofovir is better tolerated and has lower renal toxicity based on preclinical trials [

29]. Hepatotoxicity (transaminases>2 the upper limit in 25% of patients) and gastrointestinal intolerance, however, diminish its applicability. Cidofovir is held back for severe cases because of its nephrotoxicity and IV route.

5.2. Immunomodulatory Approaches

Apart from direct antivirals, a wide range of immunomodulatory interventions have been proposed for severe cases. IVIG has been successfully used in critically ill patients including in those with evidence of cytokine storm or immune complex-mediated disease [

30]. The process probably implies an effect on receptors (Fc, and others), on complement factors, and the anti-idiotypic activity of pathological antibodies. The selective modulation of cytokines is a relatively new strategy. However, neither are supported by controlled trial evidence at this time [

31]. These are agents that you might consider in concert with an infectious disease and/or critical care expert.

5.3. Supportive Care and Complication Management

Supportive care is still the cornerstone of mpox treatment. Pain It can be challenging to manage pain, in particular for proctitis and severe cutaneous lesions that frequently require multimodal analgesia with topical anaesthetics, gabapentinoids and opioids in severe cases [

32]. A second-line bacterial infection of skin lesions affects approximately 15% of hospitalised patients and should be quickly recognised and covered with specific antimicrobials. Ocular disease is infrequent (<5%) but can result in permanent visual loss if not treated adequately. Trifluoridine ophthalmic solution is active against MPXV in vitro and is the treatment of choice for ocular disease [

33]. Patients with periocular lesions or ocular symptoms should undergo periodic ophthalmologic examination.

6. Vaccination Strategies and Challenges

6.1. Vaccine Platforms and Efficacy

Three vaccines are available against mpox, differing in their properties and cross-reactivity (

Table 4). The modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine (MVA-BN, trade as JYNNEOS/IMVANEX) is the hall mark of current mpox prophylaxis [

34]. This non-replicating viral vector vaccine has an 85% efficacy against symptomatic disease after the second dose and excellent safety profile even in immunocompromised populations. ACAM2000, a second-generation replicating vaccinia vaccine, is cross-protective against mpox with unacceptable toxicities including progressive vaccinia in immunosuppressed hosts and myopericarditis (1:175) [

35]. Consequently, it is limited to only healthy individuals with no contraindications. A replicating attenuated vaccine (LC16m8) licensed in Japan provides intermediate safety and has efficacy in animal models [

36]. Nonetheless, it is impractical in general practice due to the limited global availability and experience.

6.2. Vaccination Implementation and Equity Concerns

The worldwide rollout of the early mpox vaccinations has revealed stark inequality in pandemic response. High income countries purchased around 78% of the total available doses of MVA-BN by advance purchase agreements, whereas endemic African countries faced severe shortage [

37]. This inequity not only sustained suffering in previously impacted areas, but also left the door open to ongoing viral evolution and possible reseeding of outbreaks. It occurred to us that, in affected countries, strategies from post-exposure prophylaxis of known contacts would move towards less reactive pre-exposure vaccination of high-risk groups typically men having sex with men (MSM) with multiple partners or living with HIV [

38]. This risk-based strategy has been successful in containing outbreaks but should be carefully implemented to prevent stigmatizing affected communities.

6.3. Durability of Protection and Booster Considerations

It is not known how long immunity provided by the vaccines will last. Observations from smallpox vaccination imply that cross-protection against mpox may last decades, with 10- to 50-fold initial reductions in antibody titers occurring in the first two to five years [

39]. With MVA-BN, neutralizing antibodies peak at 4 weeks after second dose and are detectable for at least 2 years; the relationship to clinical protection is not yet well-defined. Booster vaccination approaches are also being studied especially of immunocompromised subjects who can make suboptimal primary responses. Early data suggests that a third dose at 6 to 12-month increases neutralising antibody titres and can expand cross-clade immunity [

40].

7. Public Health Implications and Future Directions

7.1. Surveillance and Early Warning Systems

The mpox outbreak highlights the necessity for strong, equitable surveillance. Classical syndromic surveillance will need to be supplemented by genomic sequencing, in order to follow viral evolution on line [

41]. Wastewater surveillance that has been capable of detecting MPXV RNA in multiple outbreak contexts provides an additional method for community level surveillance [

42]. Strengthening of laboratory capacity and diagnostics among low- and middle-income countries is also necessary to contribute effectively to global surveillance networks. Investments in point of care testing platforms and regional reference laboratories would increase early detection and containment capacities.

7.2. Stigma Reduction and Community Engagement

The unequal burden of mpox on MSM and the LGBTQ+ communities underscores a longstanding struggle against stigma related to health. Accurate public health messaging should be sensitive to the need to prevent damaging stereotypes [

43]. Community-based organizations have been instrumental in responding to the outbreak, via peer education, vaccination outreach programs and reducing stigma. Future preparedness initiatives must involve affected communities in the planning and implementation process. This involves the participation of lay representatives in guideline development, maintaining service availability and ensuring privacy with regards to data collection and reporting.

7.3. Research Priorities and Knowledge Gaps

Despite advances, significant knowledge gaps persist. Priority research areas include:

Long-term immunity: Duration of immunity: longevity of protection after natural infection or vaccination, correlates of immune protection, and infectious dose [

44].

Asymptomatic transmission: Prevalence and contribution to outbreak dynamics, particularly in high-risk settings [

45].

Antiviral resistance: Mechanisms, risk factors, and alternative therapeutic approaches for resistant strains [

46].

Animal reservoirs: Maintenance and transmission cycles in wildlife, potential for reverse zoonosis, and One Health interventions [

47].

Neuroinvasive potential: Frequency and mechanisms of neurological complications, long-term sequelae [

48].

7.4. Policy Recommendations for Pandemic Preparedness

The mpox experience offers several lessons for future pandemic response:

Equitable resource allocation: Create international guiding principles for equitable distribution of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics during public health emergencies [

49].

Flexible regulatory pathways: Maintain mechanisms for emergency use authorization while ensuring rigorous post-authorization safety monitoring.

Integrated health systems: Strengthen primary care capacity for early detection and management of emerging infections.

Multisectoral collaboration: Formalize partnerships between public health, veterinary, environmental, and social services for comprehensive One Health approaches.

Community resilience: Invest in Community-Based Organizations as Critical Partners for Health Promotion and Outbreak Response.

8. Conclusions

The world-wide mpox outbreak of 2022-2024 is teaching us something about emerging diseases. MPXV has proven an impressive ability to adapt to and become human transmissible through rapid evolution, as well as a seemingly large hole in global health infrastructure. The intersection of viral genetic mutations, evolving patterns of transmission and social determinants of health created a perfect storm for pandemic spread. Clinical care has been revolutionised by efficacious antivirals and vaccines; however, access has not been equitable. The immunopathogenesis of severe disease, especially in immunosuppressed hosts, highlights intricate network of viral evasion strategies and host defense responses. When I look into the future, mpox is a warning and an opportunity. And as an alarm, it underscores the ongoing threat of zoonotic spillover and the fallout from inequities in health. As a chance, it offers as a model system to study viral adaptation, to test countermeasures and to build up preventive pandemic plans. We can control today’s outbreaks and prevent those of tomorrow only by investing in science, equity, and global cooperation.

References

- Ladnyj ID, et al. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972; 46:593-7.

- Foster SO, et al. Human monkeypox. Bull World Health Organ. 1972; 46:569-76.

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing—11 May 2023. 2023.

- Thornhill JP, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—April-June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:679-91. [CrossRef]

- Patel A, et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak. BMJ. 2022;378: e072410. [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov SN, et al. Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology. 2002; 297:172-94. [CrossRef]

- Bunge EM, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox: a potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16: e0010141. [CrossRef]

- Isidro J, et al. Phylogenetic characterization and signs of microevolution in the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2022; 28:1569-72.

- Luna N, et al. Monkeypox virus (MPXV) genomics: a mutational and phylogenomic analyses of B.1 lineages. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023; 52:102551. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, et al. Genomic annotation and molecular evolution of monkeypox virus outbreak in 2022. J Med Virol. 2023;95: e28036. [CrossRef]

- Liszewski MK, et al. Structure and regulatory profile of the monkeypox inhibitor of complement: comparison to homologs in vaccinia and variola and evidence for dimer formation. J Immunol. 2006; 176:3725-34. [CrossRef]

- Andrei G, Snoeck R. Differences in pathogenicity among the mpox virus clades: impact on drug discovery and vaccine development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023; 44:719-39. [CrossRef]

- Moss B. Poxvirus cell entry: how many proteins does it take? Viruses. 2012; 4:688-707. [CrossRef]

- Arndt WD, et al. Evasion of the innate immune type I interferon system by monkeypox virus. J Virol. 2015; 89:10489-99. [CrossRef]

- del Mar Fernández de Marco M, et al. The highly virulent variola and monkeypox viruses escape secreted inhibitors of type I interferon. FASEB J. 2010; 24:1479-88.

- Song H, et al. Monkeypox virus infection of rhesus macaques induces massive expansion of natural killer cells but suppresses natural killer cell functions. PLoS One. 2013;8: e77804. [CrossRef]

- Humrich JY, et al. Vaccinia virus impairs directional migration and chemokine receptor switch of human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007; 37:954-65.

- Hammarlund E, et al. Monkeypox virus evades antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses by suppressing cognate T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008; 105:14567-72. [CrossRef]

- Hudson PN, et al. Elucidating the role of the complement control protein in monkeypox pathogenicity. PLoS One. 2012;7: e35086. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina NA, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection by human antibodies isolated from survivors. Cell Rep. 2018; 24:1802-15. [CrossRef]

- Johnston SC, et al. Cytokine modulation correlates with severity of monkeypox disease in humans. J Clin Virol. 2015; 63:42-5. [CrossRef]

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2022; 400:661-9. [CrossRef]

- Curran KG, et al. HIV and sexually transmitted infections among persons with monkeypox—eight U.S. jurisdictions, May 17-July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71:1141-7. [CrossRef]

- Ogoina D, et al. Clinical course and outcome of human monkeypox in Nigeria. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71: e210-4. [CrossRef]

- Adler H, Taggart R. Monkeypox exposure during pregnancy: what does UK public health guidance advise? Lancet. 2022; 400:1509. [CrossRef]

- Li H, et al. The evolving epidemiology of monkeypox virus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022; 68:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Karem KL, et al. Characterization of acute-phase humoral immunity to monkeypox: use of immunoglobulin M enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of monkeypox infection during the 2003 North American outbreak. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005; 12:867-72. [CrossRef]

- Grosenbach DW, et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:44-53. [CrossRef]

- Chimerix. Brincidofovir prescribing information. 2021.

- Bloch EM, et al. The potential role of passive antibody-based therapies as treatments for monkeypox. mBio. 2022;13: e02862-22. [CrossRef]

- Fink DL, et al. Clinical features and management of individuals admitted to hospital with monkeypox and associated complications across the UK: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023; 23:589-97. [CrossRef]

- Adler H, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022; 22:1153-62. [CrossRef]

- Doan S, et al. Severe corneal involvement associated with mpox infection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023; 141:402-3. [CrossRef]

- Rao AK, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71:734-42. [CrossRef]

- Halsell JS, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003; 289:3283-9. [CrossRef]

- Saijo M, et al. LC16m8, a highly attenuated vaccinia virus vaccine lacking expression of the membrane protein B5R, protects monkeys from monkeypox. J Virol. 2006; 80:5179-88. [CrossRef]

- Adetifa I, et al. Mpox neglect and the smallpox niche: a problem for Africa, a problem for the world. Lancet. 2023; 401:1822-4. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Interim advice on risk communication and community engagement during the mpox outbreak in Europe. 2022.

- Mack TM, et al. A prospective study of serum antibody and protection against smallpox. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972; 21:214-8. [CrossRef]

- Overton ET, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic smallpox vaccine in vaccinia-naive and experienced human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals: an open-label, controlled clinical phase II trial. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2: ofv040. [CrossRef]

- GISAID Initiative. Genomic epidemiology of monkeypox virus. 2023.

- Wolfe MK, et al. Detection of monkeypox virus DNA in wastewater from urban and rural areas, California, 2022. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2023; 10:37-41.

- World Health Organization. Reducing stigma associated with mpox. 2022.

- Grifoni A, et al. Defining antigen targets to dissect vaccinia virus and monkeypox virus-specific T cell responses in humans. Cell Host Microbe. 2022; 30:1662-70. [CrossRef]

- Accordini S, et al. People with asymptomatic or unrecognised infection potentially contribute to monkeypox virus transmission. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4: e209. [CrossRef]

- Duraffour S, et al. KAY-2-41, a novel nucleoside analogue inhibitor of orthopoxviruses in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Doty JB, et al. Assessing monkeypox virus prevalence in small mammals at the human-animal interface in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Viruses. 2017; 9:283. [CrossRef]

- Sejvar JJ, et al. An overview of monkeypox virus and its neuroinvasive potential. Ann Neurol. 2022; 92:527-31. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Framework for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics. 2022.

- Moss B. Poxvirus membrane biogenesis. Virology. 2015;479-480:619-26.

- Bengali Z, Satheshkumar PS, Moss B. Orthopoxvirus species and strain differences in cell entry. Virology. 2012;433(2):506-12. [CrossRef]

- Lustig S, Fogg C, Whitbeck JC, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Moss B. Combinations of polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies to proteins of the outer membranes of the two infectious forms of vaccinia virus protect mice against a lethal respiratory challenge. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13454-62. [CrossRef]

- Chiu WL, Lin CL, Yang MH, Tzou DL, Chang W. Vaccinia virus 4c (A26L) protein on intracellular mature virus binds to the extracellular cellular matrix laminin. J Virol. 2007;81(4):2149-57. [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund E, Dasgupta A, Pinilla C, Norori P, Früh K, Slifka MK. Monkeypox virus evades antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses by suppressing cognate T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14567-72. [CrossRef]

- Sivan G, Martin SE, Myers TG, Buehler E, Szymczyk KH, Ormanoglu P, et al. Human genome-wide RNAi screen reveals a role for nuclear pore proteins in poxvirus morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(9):3519-24. [CrossRef]

- Graham SC, Bahar MW, Cooray S, Chen RA, Whalen DM, Abrescia NG, et al. Vaccinia virus proteins A52 and B14 Share a Bcl-2-like fold but have evolved to inhibit NF-kappaB rather than apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(8):e1000128. [CrossRef]

- Johnston SC, Johnson JC, Stonier SW, Lin KL, Kisalu NK, Hensley LE, et al. Cytokine modulation correlates with severity of monkeypox disease in humans. J Clin Virol. 2015; 63:42-5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).