1. Introduction

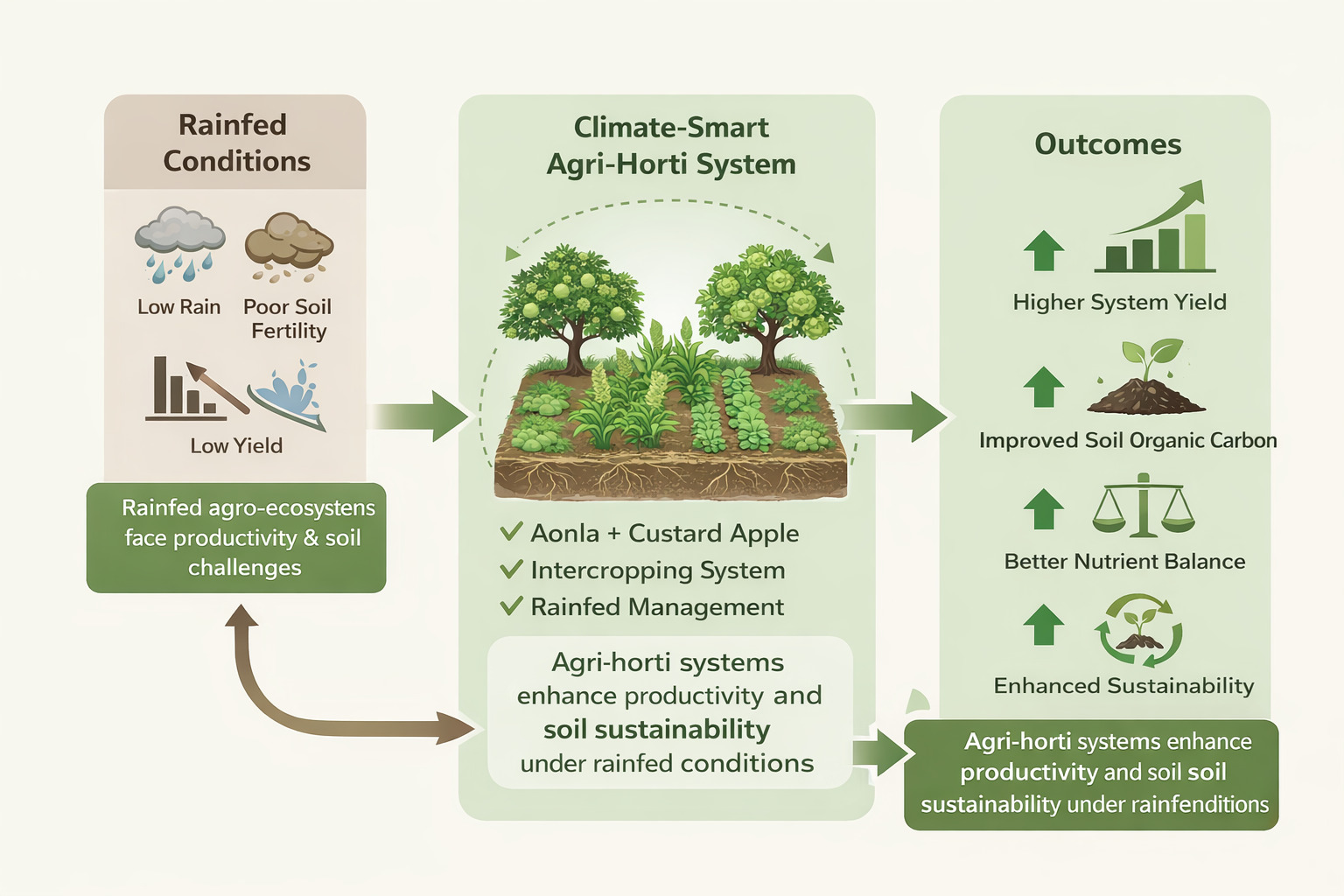

Agriculture plays a crucial role in India’s economy by supporting livelihoods, ensuring food security and contributing substantially to national income. However, agricultural production is increasingly constrained by climate change, manifested through rising temperatures, erratic rainfall patterns, and a higher frequency of extreme weather events. These climatic stresses have intensified land degradation, posing a significant challenge to sustainable agricultural development. It has been reported that nearly 29% of India’s total geographical area (96.4 million ha) is affected by land degradation due to soil erosion, deforestation, salinity, wind erosion, overgrazing, frost action, and anthropogenic pressures such as mining, urbanization, and industrialization (Periasamy and Shanmugam, 2022).

At the global level, agricultural expansion and intensification are among the major drivers of deforestation, contributing approximately 11% of total forest loss. These concerns highlight the need for land-use systems that enhance agricultural productivity while maintaining environmental integrity. Agroforestry, which integrates trees with crops and/or livestock, has emerged as a sustainable land-use option capable of addressing these challenges. Agroforestry systems operate across multiple spatial scales and are recognized for improving resource-use efficiency, ecological stability, and socio-economic resilience (Van Noordwijk, 2019; Cardinael et al., 2021). The inclusion of trees in agricultural landscapes modifies the microclimate by reducing temperature extremes, enhancing soil moisture retention, and mitigating the adverse impacts of climatic variability, thereby reducing production risks.

Aonla (Phyllanthus emblica L.) is a hardy deciduous fruit tree native to the Indian subcontinent and well adapted to diverse agro-climatic conditions. Its tolerance to drought and poor soil fertility makes it particularly suitable for rainfed and marginal environments (Bhatia et al., 2022). The fruit is valued for its high nutritional and medicinal attributes, especially its exceptional vitamin C content and antioxidant properties (Singh et al., 2019). Owing to these characteristics, aonla-based agroforestry systems have gained attention for their potential to enhance farm income while promoting ecological sustainability.

Custard apple (Annona squamosa L.), commonly known as sugar apple, is an important fruit crop of tropical and subtropical regions. In India, it is predominantly cultivated in semi-arid and rainfed areas where its low input requirement and adaptability to harsh climatic conditions make it an important livelihood crop for resource-poor farmers (ICAR, 2025). Custard apple fruits are rich in carbohydrates, vitamin C, dietary fibre, potassium, magnesium, and antioxidants, contributing to their growing recognition as functional foods. Additionally, various plant parts have been traditionally used for their pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial activities (Verma et al., 2025).

The global population is projected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030 and 9.7 billion by 2050, intensifying the demand for food production under limited natural resources (United Nations, 2022). This scenario necessitates diversification of cropping systems and the adoption of resilient production strategies capable of sustaining productivity under climate stress. Intercropping has been identified as an effective approach to improve land-use efficiency and resource utilization, particularly in orchard-based production systems.

Intercropping involves the simultaneous cultivation of two or more crops on the same land unit in a defined spatial arrangement (Das et al., 2019). Fruit crops are perennial and require several years to reach full bearing capacity, during which substantial inter-row spaces remain underutilized. The introduction of suitable intercrops during this juvenile phase enhances resource-use efficiency, provides additional income, and improves soil health. Intercrops also act as cover crops, suppress weed growth, reduce soil erosion, and benefit from the irrigation and nutrient inputs applied to the orchard system (Bakshi et al., 2019). The incorporation of crop residues further improves soil organic matter content and nutrient cycling, contributing to long-term sustainability.

In rainfed and dryland regions, agri-horticultural systems integrating compatible intercrops can improve water-use efficiency, conserve soil fertility, and stabilize farm income, thereby enhancing system resilience (Singh et al., 2020). The success of such systems depends on the selection of intercrops that minimize competition with fruit trees for water, nutrients, and light. Pulses and millets, owing to their short duration, drought tolerance, and low nutrient requirements, are particularly suitable for integration into orchard-based systems. Several studies have reported yield advantages of intercropping over sole cropping due to improved overall system productivity (Willey, 1979).

Despite the recognized benefits of agroforestry and intercropping systems, scientific information on the integration of pulses and millets which are primarily grown as rainfed crops within aonla- and custard apple-based agri-horticultural systems is limited. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the performance of selected intercrops under aonla- and custard apple-based agri-horti systems in terms of growth, yield, resource-use efficiency, and economic viability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Site Specification and Characteristics

The present study, on Climate-Smart Aonla and Custard Apple Agri-Horti Systems for Enhanced Yield and Soil Sustainability under Rainfed Conditions was conducted during December 2022–23 to 2024–25 at the AICRPDA Research Farm, Agricultural Research Station, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU), Kovilpatti, Thoothukudi district, Tamil Nadu, India. The experimental site is located in the southern agro-climatic zone of Tamil Nadu, geographically positioned at 9.4646° N latitude and 77.7987° E longitude, with an altitude of approximately 90 m above mean sea level (Appendix A.1).

The region experiences a semi-arid tropical climate, characterized by hot days and moderately cool nights. Based on thirty years of climatological data, the relative humidity ranges from 48.2 to 80.3%. The mean maximum and minimum temperatures are 35.3 °C and 22.4 °C, respectively. The area receives an average annual rainfall of 732.7 mm, distributed over approximately 42 rainy days. The average evapotranspiration rate is 6.5 mm day⁻¹, with a mean sunshine duration of 6.9 hours day⁻¹ and an average wind velocity of 5.7 km h⁻¹. During the NEM where the cropping was done experienced with the mean maximum and minimum temperatures are 32.3 °C and 21.4 °C, respectively. The area receives an average seasonal rainfall of 407.4 mm, distributed over approximately 22 rainy days. The average evapotranspiration rate is 4.1 mm day⁻¹, with a mean sunshine duration of 5.5 hours day⁻¹ and an average wind velocity of 3.5 km h⁻¹. However, the weather parameters including soil moisture prevailed during the cropping periods was depicted in the (Appendix B)

2.1.2. Soil Properties of the Experimental Site

The soil of the experimental site sampled at a depth of 0–15 cm and the soil physico-chemical characteristics of the soil done as per the standard analytical procedures. It was found clayey in texture and slightly alkaline in reaction, with a pH ranging from 8.14 to 8.17 and non – saline (EC 0.10 and 0.13 dS m⁻¹). The soil organic carbon content was in the range of 3.02 to 5.18 g kg⁻¹. Available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents were low, low and high with 160 to 168, 11.3 to 11.5 and 434 to 446 kg ha⁻¹, respectively. The soil field capacity ranged from 33.9 to 35.8 per cent and a permanent wilting point of 14 per cent.

2.1.3. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experiment was laid out in a split-plot design with three replications. The main-plot treatments consisted of two horti-fruit tree species, namely aonla (Phyllanthus emblica L.) cv. NA-7 (M₁) and custard apple (Annona squamosa L.) cv. APK-1 (M₂). The sub-plot treatments comprised four intercrops: blackgram (Vigna mungo L.) cv. VBN-11 (S₁), greengram (Vigna radiata L.) cv. VBN-5 (S₂), cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.) cv. Pusa Navbahar (S₃), and foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) cv. CO-7 (S₄). Five years old Aonla and custard apple was maintained with spacing of 5.0 x 5.0 m and the intercrops viz., Clusterbean sown at 45 x15 cm, Blackgram / greengram sown at 30 x 10 cm and Foxtail millet with 22.5 x 10 cm.

The recommended dose of fertilizers applied was 12.5 kg N, 25 kg P₂O₅, and 12.5 kg K₂O ha⁻¹ for blackgram, greengram, and cluster bean; and 44 kg N and 22 kg P₂O₅ ha⁻¹ for foxtail millet. For custard apple, fertilizers were applied at 0.25:0.12:0.25 kg N: P₂O₅: K₂O tree⁻¹ year⁻¹ along with 50 kg FYM tree⁻¹ year⁻¹, while aonla received 0.25:0.16:0.30 kg N: P₂O₅: K₂O tree⁻¹ year⁻¹ along with 50 kg FYM tree⁻¹ year⁻¹ during the minth of Sept to Oct coincide with the onset of North East Monsoon. Each experimental plot had a gross area of 80 m² and a net plot area of 60 m². Standard agronomic practices were followed to raise a healthy crop, and all cultural operations were carried out uniformly across treatments. The intercropping geometry adopted in the experiment is illustrated in (Appendix C).

2.2. Assessment Measures of Crop Performance

2.2.1. Growth Characteristics and Yield of Intercrops

Five plants were randomly tagged in each net plot for recording biometric observations. Observations on germination percentage, plant population per square metre, plant height (cm), days to first flowering, and leaf area index were recorded at appropriate crop growth stages. Grain and haulm yield of the intercrops were measured in kgs and expressed on a hectare basis following standard procedures.

2.2.2. SPAD-502 Measurements

SPAD-502 measurements were taken following the procedure described by Peng et al. (1993) using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Soil-Plant Analysis Development section, Minolta Camera Co. Ltd., Japan). Readings were recorded on the uppermost fully expanded leaves of five randomly selected plants at the flowering stage of the intercrops. The mean of these readings was computed for each plot and expressed as SPAD units.

2.2.3. Light Interception (Lux Meter)

Light intensity was measured using a hand-held lux meter between 10:30 and 11:00 a.m. at the flowering stage of the intercrops. In each plot, a single measurement was recorded above the fruit tree canopy. At ground level, light intensity readings were taken at five randomly selected locations and the mean value was computed. Based on the above-canopy and ground-level measurements, the percentage of light interception by the entire canopy was estimated.

2.2.4. Crop Equivalent Yield (CEY):

The yields of different intercrops were converted into equivalent yield of a single reference crop based on the prevailing market price of the produce.

where:

Yi = Yield of the iᵗʰ intercrop (kg ha⁻¹)

Pi = Market price of the iᵗʰ intercrop (₹ kg⁻¹)

Pr = Market price of the reference (base) crop (₹ kg⁻¹)

2.2.5. Land Equivalent Ratio (LER)

The relative land area under sole crop that would be required to produce the equivalent yield under a mixed or an intercropping system at the same level of management

where,

La and Lb are LER of crop a and crop b respectively;

Yab : yield of crop a in intercropping;

Yba : yield of crop b in intercropping;

Yaa : yield of crop a in pure stand ;

Ybb : yield of crop b in pure stand

2.2.6. Rainwater Use Efficiency:

RWUE indicates the efficiency with which rainfall is converted into economic yield under rainfed conditions and is calculated as

where,

2.3. Assessment of Tree Parameters

Four trees per treatment were randomly selected for recording observations on various growth parameters and fruit yield. Growth parameters were measured at the time of sowing of the intercrops, while fruit yield was recorded at the stage of fruit maturity. The methods adopted for measuring these attributes are described below.

2.3.1. Tree Height (m)

Tree height from base to tip of the tree was measured with the help of wooden rod and expressed in meters.

2.3.2. Tree Diameter (cm)

Tree diameter was measured in cm at breast height i.e., 1.37 m above the ground level with the help of tree caliper.

2.3.3. Crown Spread (m2)

The crown spread was measured in meters by holding the measuring tape beneath the canopy of the tree at points vertically under the tips of most extending branches from east to west and north to south directions. The average of the two was taken as crown spread. Crown spread was calculated using the following formula

where;

D1 = Crown spread in N-S direction (m)

D2 = Crown spread in E-W direction (m)

2.3.4. Fruit Yield Tree (kg)

The total fruit harvested per tree was weighed and expressed as fruit yield kgha-1.

2.4. Economic Analysis

Gross and net returns were quantified for all the treatment combinations. The cost of inputs, labour wages and current market rate of farm produce were used for working out the economics. The benefit cost ratio for each treatment was also assessed by using the following formula.

Gross return (Rs.ha-1) = Economic yield (kg ha-1) x Market value of the produce (Rs. kg-1)

Net return (Rs.ha-1) = Gross return (Rs.ha-1) – Cost of cultivation (Rs.ha-1)

Benefit: Cost ratio = Gross return (Rs. ha-1) / Cost of cultivation (Rs. ha-1)

2.5. System Profitability (Rs/ha/day)

System Profitability is the total net return realized per hectare area per year and divided by 365.

2.6. Relative Economic Efficiency

Relative Economic Efficiency (REE) is an economic indicator used to compare the profitability of an intercropping system with that of a sole cropping system. It expresses how efficiently an intercropping system utilizes resources to generate additional net returns. Higher the economic efficiency better the system. REE is calculated as:

where,

DNR- Net return obtained under improved/diversified system

ENR- Net return in the existing system.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from field observations and laboratory analyses were statistically analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the procedure described by Gomez and Gomez (1984). The analysis was performed using R software. The standard error of difference (SEd ±) and critical difference (CD) at the 5 percent level of significance were computed to test the significance of treatment effects, while non-significant differences were denoted as NS.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Component / Intercrops

3.1.1. Plant Population and Height of Intercrops

No significant difference was observed between the Aonla and Custard apple based systems of intercrops population. However, at harvest and it ranged from 12 to 42 plants m⁻², with significant variation among the intercrops. Foxtail millet recorded the highest population (40–41 plants m⁻²), followed by blackgram and greengram (30 plants m⁻² each). The variation in plant population may be attributed to differences in seed size, germination ability, early seedling vigour, and adaptability to rainfed conditions. Foxtail millet, owing to its small seed size, rapid germination, and strong early establishment, maintained a higher plant stand (Ramesh et al., 2023). In contrast, blackgram and greengram are more sensitive to soil moisture fluctuations during emergence, which may have resulted in comparatively lower plant populations (Sharmili & Manoharan, 2018).

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Plant height of intercrops responded positively under both Aonla and Custard apple based intercropping systems (

Figure 5). The Custard apple based system recorded higher mean plant height (50.8 to 117.7 cm) than the Aonla based system (48.1 to 110.2 cm), likely due to its open and diffused canopy that enhances light penetration and reduces competition for moisture and nutrients (Singh et al., 2020; Bhadani et al.

, 2023). Among intercrops, foxtail millet attained the greater plant height (117.7 cm), followed by cluster bean (61.8 cm), owing to rapid vertical growth, partial shade tolerance, and efficient resource use (Aravind et al., 2023). Clusterbean’s moderate shade tolerance and drought resilience further supported its growth under tree-based systems (Kushwah et al.

, 2017; Arif et al.

, 2022). Blackgram recorded the lowest plant height (48.1 cm), possibly due to its sensitivity to competition for light and nutrients, especially under the Aonla canopy (Banerjee et al.

, 2021). The interaction effect showed that Custard apple + foxtail millet produced the maximum plant height (120.7 cm), followed by Aonla + foxtail millet, attributable to favorable canopy structure and complementary growth behavior (Aravind et al., 2023). The minimum height of 48.3 cm was observed in Aonla + blackgram, likely due to combined shading effects and poor adaptability of blackgram (Srivastav et al.

, 2023).

Custard apple based intercropping also promoted earlier flowering. Blackgram and greengram flowered earlier (32 to 33 days) under Custard apple than under Aonla (32 to 34 days), likely due to a moderated microclimate reducing stress and accelerating crop development (Basu et al., 2023). Clusterbean and foxtail millet flowered in 36 to 38 days under both the systems.

3.1.2. Leaf Area Index, SPAD Value and Light Intensity (%)

Leaf Area Index (LAI) is a key physiological indicator of crop canopy development and radiation interception, with direct implications for photosynthetic performance, biomass production, and yield. Likewise, chlorophyll content, commonly assessed using SPAD readings, serves as an effective proxy for leaf nitrogen status and photosynthetic capacity, thereby influencing overall crop productivity. In the present investigation, neither LAI nor chlorophyll content exhibited significant variation between Aonla and Custard apple based agri-horti systems. Across the three years of study, LAI values ranged from 1.8 to 2.5 under the Aonla based system and from 1.9 to 2.6 under the Custard apple based system (

Figure 6). Similarly, SPAD values varied from 27.3 to 31.2 in the Aonla system and from 27.9 to 31.5 in the Custard apple system (

Figure 7). The absence of significant differences in LAI and chlorophyll content between the two agri-horti systems may be attributed to comparable availability of growth resources for the intercrops. Despite differences in canopy architecture, both tree-based systems likely ensured adequate light penetration, soil moisture, and nutrient supply, supporting normal leaf expansion and chlorophyll synthesis and thereby resulting in minimal variation in LAI and SPAD values (Asangi et al.

, 2019).

However, significant variation was observed among the intercrops with respect to LAI and chlorophyll content. Green gram and cluster bean consistently recorded higher LAI (2.5 to 2.6) across both agri-horti systems, irrespective of the tree species. The comparatively higher LAI in green gram and cluster bean may be attributed to their inherent growth characteristics, including profuse branching and rapid leaf expansion, which promote enhanced canopy development (Thirumal et al., 2023; Hussain et al., 2022). Additionally, as leguminous crops, these intercrops benefit from biological nitrogen fixation, which supports sustained vegetative growth and greater leaf area development, even under partial shade conditions (Kebede, 2021).

Chlorophyll content, as indicated by SPAD values, was highest in foxtail millet (31.2 to 31.5), which was statistically comparable to cluster bean (29.4 to 30.2) under both agri-horti systems. This response can be attributed to their efficient nitrogen uptake and utilization, resulting in enhanced chlorophyll synthesis and retention (Nadeem et al., 2018). Furthermore, foxtail millet, being a C4 crop, exhibits superior photosynthetic efficiency and greater chlorophyll stability, enabling it to maintain higher SPAD values under variable light environments typical of tree-based systems (Jiao Mao et al., 2024).

With respect to light availability (

Figure 8), the Custard apple based agri-horti system allowed significantly greater light penetration (mean value of 66.7%) compared to the Aonla based system (mean value of 55.9%). This difference is likely associated with the relatively open and less dense canopy architecture of Custard apple trees. Enhanced light availability during the cropping period under the Custard apple system may have stimulated photosynthetic activity and chlorophyll retention in intercrops, thereby supporting higher LAI and SPAD values, particularly in light-responsive crops as already reported by Asangi et al.

, 2019.

3.1.3. Grain Yield and Blackgram Equivalent Yield of Intercrops

The Aonla- and Custard apple based agri-horti systems exerted a significant influence on the grain and haulm / stover yields of the intercrops. Overall, higher mean intercrop yields were recorded under the Custard apple based system, where grain yields ranged from 850 to 3565 kg ha⁻¹ and haulm / stover yields from 1731 to 6265 kg ha⁻¹. In comparison, the Aonla based system recorded grain yields of 830 to 3322 kg ha⁻¹ and haulm / stover yields of 1910 to 6490 kg ha⁻¹ (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The superior intercrop productivity observed under the Custard apple based agri-horti system may be attributed to improved light availability and a more favourable microclimatic environment beneath the tree canopy (Jagdish, 2023). The relatively open canopy architecture of custard apple facilitates greater light penetration, which enhances leaf area development, chlorophyll content, and photosynthetic efficiency of intercrops, thereby supporting higher biomass accumulation and assimilate production and ultimately resulting in increased grain and haulm yields compared to the Aonla based system (Asangi et al.

, 2019).

Among the intercrops, cluster bean produced the highest average grain yield (3322 to 3565 kg ha⁻¹) and haulm yield (5743 to 5952 kg ha⁻¹), irrespective of the fruit tree species, followed by foxtail millet, which recorded grain yields of 2155 to 2295 kg ha⁻¹ and haulm yields of 2625 to 2925 kg ha⁻¹. The lowest yields were obtained with blackgram. Overall, the Custard apple based system resulted in a 2.4 to 6.8% increase in grain yield and a 3.5 to 10.3% increase in haulm / straw yield over the Aonla based system.

Interaction effects revealed that the Custard apple + cluster bean combination recorded the higher grain and haulm yields, which were statistically at par with the Aonla + cluster bean combination. These were followed by Custard apple + foxtail millet and Aonla + foxtail millet. The superior performance of cluster bean and foxtail millet based combinations under both agri-horti systems may be attributed to its higher shade tolerance and efficient utilization of nutrients and water, enabling stable productivity under varying light environments (Pannase et al., 2023). In contrast, the lowest yields were observed under Aonla + blackgram and Aonla + greengram combinations, which may be due to greater canopy shading, reduced photosynthetically active radiation, and increased interspecific competition, adversely affecting flowering, pod formation, and seed filling in these crops (Manoharan et al., 2023).

The blackgram equivalent yield followed trends similar to those observed for individual intercrop yields. The Custard apple based agri-horti system recorded a higher mean blackgram equivalent yield (1143 kg ha⁻¹) compared to the Aonla based system yield of 1087 kg ha⁻¹. Among the intercrops, cluster bean registered the highest blackgram equivalent yield range of 1384 to 1485 kg ha⁻¹, followed by foxtail millet (1293 to 1377 kg ha⁻¹), while the lowest equivalent yield was recorded with blackgram (

Figure 11). Interaction analysis further indicated that the Custard apple + cluster bean combination achieved the highest blackgram equivalent yield, reflecting optimal complementarity between tree canopy structure and intercrop growth (Hemalatha et al., 2025). Conversely, the lowest equivalent yields under Aonla + blackgram and Aonla + greengram combinations may be attributed to heightened interspecific competition and reduced photosynthetic efficiency, leading to lower yield realization. Similar observations have been found by Patle et al., 2020.

3.1.4. Rain Water Use Efficiency of Intercrops

Rainwater Use Efficiency (RUE), expressed as the ratio of crop yield to total rainfall received during the cropping season, differed significantly among the intercrops evaluated. Cluster bean recorded the highest mean RUE (7.76 kg ha mm⁻¹) over the three years of experimentation (

Figure 12). The significantly higher RUE observed in cluster bean can be attributed to its superior capacity to convert available rainfall into economic yield. This crop possesses a well-developed root system and an efficient canopy architecture, which facilitate enhanced soil moisture extraction and reduced evaporative losses (Ramanjineyulu et al., 2024). Moreover, it’s relatively higher leaf area index and sustained chlorophyll content support efficient photosynthesis under rainfed conditions, thereby improving biomass accumulation per unit of rainfall received. Among the agri-horti combinations, the Aonla + cluster bean system recorded a high RUE (7.24 kg ha mm⁻¹), likely due to complementary interactions between the tree and intercrop. Partial shading under the aonla canopy may have moderated soil temperature and minimized surface evaporation, resulting in improved soil moisture conservation and enhanced water uptake efficiency of cluster bean, ultimately leading to higher yield per unit of rainfall. These finding also corroborated with Kokila et al., 2024.

In contrast, greengram and blackgram exhibited markedly lower RUE values, each recording less than 2.0 kg ha mm⁻¹. The lower RUE in these crops may be attributed to their comparatively shallow root systems and limited tolerance to intermittent moisture stress under rainfed conditions. Restricted canopy development and reduced photosynthetic efficiency under suboptimal soil moisture further constrained effective utilization of rainfall, leading to lower yield realization per unit of rainwater received. Amarapalli, 2022 and Thakur et al., 2017 also found similar findings.

3.2. Tree Component Results

3.2.1. Growth Parameters of Aonla and Custard Apple

Growth parameters of trees measured at key developmental stages were significantly influenced by cropping systems. In general observation from this trial, trees grown under agri–horti system (aonla or custard apple intercropped with annual crops) recorded higher tree height, stem girth, collar diameter, and canopy spread than those under sole planting, likely due to improved soil fertility, moisture conservation, and microbial activity that enhanced nutrient availability and biomass accumulation. Among fruit species, aonla consistently exhibited superior growth over custard apple, attributable to its vigorous growth habit, deeper root system, and better adaptation to rainfed conditions (Kour et al., 2019). Intercrop type further affected tree performance, with greengram / blackgram intercropping producing the maximum improvement in growth parameters of trees, owing to their short duration and nitrogen-fixing ability, particularly (Bernard et al., 2024; Rajarathinam et al., 2025). In contrast, foxtail millet intercropping resulted in the lowest growth values, possibly due to its rapid early growth and greater competition for water and nutrients. Overall, pulse-based intercropping enhanced tree vigour and sustainability in agri–horti systems under rainfed conditions (Sharmili et al., 2021).

3.2.2. Height of Custard Apple and Aonla Tree

Tree height of custard apple and aonla exhibited a positive response under intercropping systems throughout the experimental period (2022–23 to 2024–25). Overall, progressive increases in tree height were observed across successive years, with aonla and custard apple attaining maximum heights of 508 cm and 391 cm, respectively, during 2024–25. This represented net height increments of 132 cm in aonla and 108 cm in custard apple compared to the initial measurements recorded in 2022–23 under Aonla / Custard apple + blackgram intercropping system (

Figure 13). The sustained increase in tree height under intercropping may be attributed to favourable modifications in the soil–plant environment induced by intercrops, including enhanced nutrient availability, increased soil biological activity, and improved soil moisture retention over time (Bhavanasi Dharani and Balram Pusam, 2020; Ileana, 2021). In addition, intercropping likely reduced soil surface evaporation and improved infiltration of rainfall received during the growing season, thereby creating a more favourable rhizosphere for continuous tree growth.

Among the intercrop treatments, the maximum height increment in both fruit species was recorded under the Aonla / Custard apple + blackgram system. This response may be associated with the leguminous nature of blackgram, which contributes to soil nitrogen enrichment through biological nitrogen fixation and improves soil organic carbon levels via root biomass and leaf litter addition (Ajahanturon et al., 2025). This was followed by the Aonla / Custard apple + greengram combination, which resulted in height increments of 118 cm in aonla and 108 cm in custard apple. The beneficial effect of greengram intercropping can be attributed to its rapid early growth, relatively low nutrient demand, and efficient nitrogen contribution to the soil. Moreover, the faster decomposition of greengram residues likely enhanced nutrient recycling and soil moisture retention, with soil moisture levels reaching up to 12.03 per cent in greengram based systems. Similar findings also in agreement with the studies of Murtaza Hussain Shah et al., 2017.

In contrast, trees grown under sole cropping exhibited comparatively lower height increments, recording of only 110 cm in aonla and 94 cm in custard apple over the same period. The least height increment in both fruit species was observed under intercropping with cluster bean or foxtail millet across the three years of study. This reduced growth may be attributed to the aggressive root systems, rapid biomass accumulation, higher water and nutrient requirements, and longer field duration of these crops, which intensified competition for resources with tree roots and consequently restricted height growth. Sathiya et al., 2025 and Kumar et al., 2024 found the same results.

3.2.3. Stem Girth and Collar Diameter of Custard Apple and Aonla Tree

Stem girth and collar diameter of both aonla and custard apple exhibited a positive response under intercropping systems throughout the experimental period (2022–23 to 2024–25). The observed improvements in these secondary growth parameters can be attributed to enhanced soil physical conditions, improved nutrient availability, and sustained assimilate supply promoted by compatible intercrops (Moreira et al., 2024). Intercropping improve soil structure and stimulate microbial activity, thereby facilitating better root proliferation and cambial activity, which is reflected in increased stem girth and collar diameter (Dugassa et al., 2023). Across the study period, the aonla + intercrop systems recorded higher mean stem girth (28.1 to 32.0 cm) and collar diameter (58.6 to 69.3 cm) compared to the corresponding custard apple + intercrop systems. This response may be attributed to the inherently vigorous growth habit of aonla and its stronger responsiveness to improved nutrient and moisture regimes created under intercropping conditions (Thimmegowda et al., 2022).

The maximum progressive increments in stem girth and collar diameter were recorded under the aonla + blackgram and custard apple + blackgram combinations, with respective increases of 5.00 cm and 9.10 cm in aonla, and 5.80 cm and 10.00 cm in custard apple, respectively (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). These increments were statistically comparable to those observed under greengram intercropping. The superior performance of these legume-based systems can be linked to effective biological nitrogen fixation and rapid residue decomposition, which enhance soil nitrogen availability and stimulate cambial activity responsible for radial stem growth (Akchaya et al.

, 2025). In addition, the shallow rooting pattern and short duration of blackgram / greengram reduce competition for water and nutrients, enabling greater assimilate allocation towards stem thickening. The symbiotic association of legume roots with Rhizobium spp. further enhances plant-available nitrogen, increases soil organic carbon, and improves soil structure, collectively creating a fertile soil environment that supports sustained secondary growth of tree stems (Ananda et al.

, 2022; Gou et al.

, 2023; Sahoo et al.

, 2025).

In contrast, under sole cropping conditions recorded comparatively lower increments, with increases of only 4.6 cm and 5.2 cm in aonla, and 6.20 cm and 7.90 cm in custard apple for stem girth and collar diameter, respectively, over the study period. Reduced radial growth under sole cropping may be attributed to limited organic matter inputs, lower microbial activity, and less efficient nutrient recycling, which collectively constrained secondary growth despite advancing tree age (Schmidt et al., 2025). The minimum increments in stem girth and collar diameter for both fruit species were observed when intercropped with cluster bean or foxtail millet. This response may be due to their comparatively higher nutrient and water requirements and more extensive root systems. These findings underscore the importance of selecting compatible intercrops, as certain crop combinations may not confer the expected intercropping benefits when resource demands overlap (Erena and Melkamu, 2023).

3.2.4. Canopy Spread (cm) of Custard Apple and Aonla Tree

Canopy spread of aonla and custard apple exhibited relatively narrow variations across the experimental period (2022–23 to 2024–25). Canopy development was largely governed by species-specific genetic architecture and long-term growth dynamics, with intercropping exerting only a moderating influence during the early to mid-bearing stages (Ma et al.

, 2024). Overall, aonla recorded a wider canopy spread in both directions, ranging from 306 to 356 cm in the north–south orientation and from 307 to 331 cm in the east–west orientation. These values corresponded to progressive increases of 54 to 81 cm and 65 to73 cm, respectively form the 2022-23 (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). The broader canopy development in aonla can be attributed to its naturally expansive branching pattern, deeper and more extensive root system facilitates efficient exploitation of soil moisture and nutrients, thereby supporting sustained lateral canopy expansion over successive seasons (Patel et al.

, 2025; Awasthi et al.

, 2025).

The relatively greater progressive increase in aonla canopy spread also indicates higher morphological plasticity in response to the improved soil environment created under agri–horti systems (Freitas and Silva, 2022; Mehta et al., 2025). In contrast, custard apple exhibited comparatively smaller canopy spreads, ranging from 227 to 242 cm in the north–south direction and from 213 to 238 cm in the east–west direction, with progressive increments of 31–59 cm and 21–42 cm, respectively. This comparatively restrained canopy development may be attributed to its compact growth habit, sparse branching, and slower lateral shoot extension. Consequently, custard apple canopy expansion appears less responsive to short-term intercropping effects and more dependent on inherent growth characteristics and long-term developmental patterns (Bisht et al., 2025; Aditya Gaurha et al., 2024).

3.2.5. Fruit Yield of Custard Apple and Aonla Tree and Its Blackgram Equivalent Yield

Custard apple consistently produced higher fruit yields than aonla across all intercropping systems during the three years study period. Average fruit yield of custard apple ranged from 2674 to 3306 kg ha⁻¹, whereas aonla recorded comparatively lower yields of 1980 to 2538 kg ha⁻¹. The superior fruit productivity of custard apple may be attributed to its early bearing habit, higher flower-to-fruit conversion efficiency, and lower sink limitation under rainfed conditions (Rathod et al., 2024). In addition, custard apple exhibits greater adaptability to seasonal fluctuations in soil moisture and efficiently partitions assimilates towards fruit biomass, resulting in higher productivity per unit area (Murali et al., 2024).

The maximum fruit yield of 3306 kg ha⁻¹ was recorded under the custard apple + blackgram intercropping system, representing a 19.11% increase over custard apple grown as a sole crop. This treatment was statistically at par with the custard apple + greengram and significantly superior to other intercrop combinations (

Figure 18). The enhanced performance under blackgram and greengram intercropping can be attributed to the short duration and shallow rooting pattern of these legumes, which minimize competition for water and nutrients while simultaneously improving soil nitrogen availability through biological nitrogen fixation. The resulting improvement in nutrient availability during critical flowering and fruit development stages, thereby enhancing fruit yield under rainfed conditions (Masina et al.

, 2024; Adam et al.

, 2025; Shen et al.

, 2024). Similarly, aonla intercropped with blackgram or greengram also exhibited a yield advantage over its associations with cluster bean and foxtail millet, which may be attributed to increased competition for soil moisture and nutrients under the latter combinations, particularly during peak demand periods (Wei et al.

, 2025).

The blackgram equivalent yield of the tree component yield also varied markedly among the systems. Custard apple based systems recorded higher equivalent yields, ranging from 1337 to 1653 kg ha⁻¹, compared with 891 to 1142 kg ha⁻¹ in aonla based systems during the three-year period. The highest blackgram equivalent yield of 1653 kg ha⁻¹ was obtained under the custard apple + blackgram system, reflecting a 21.97% increase over the sole custard apple. This treatment was statistically comparable to custard apple + greengram and superior to all other intercrop combinations. The higher equivalent yields observed under custard apple based agri–horti systems emphasize their superior economic efficiency, arising from both enhanced fruit productivity and the added economic value of the pulse intercrops. These results highlight the suitability of legume-based agri–horti systems, particularly those involving blackgram and greengram, for improving productivity and sustainability under rainfed conditions (Kalaimegam et al., 2025; Sathiya et al., 2025).

Similarly, aonla intercropped with blackgram or greengram recorded higher blackgram equivalent yields than its combinations with cluster bean and foxtail millet, further emphasizing the advantage of pulse-based intercropping. Overall, the findings demonstrate that legume-based intercrops create a mutually beneficial micro-environment that enhances fruit yield and system productivity, with custard apple showing a stronger positive response than aonla due to its higher physiological efficiency and growth behaviour under rainfed agro-ecosystems (Ileana, 2021; Janke et al., 2024).

3.2.6. Rain Water Use Efficiency of Aonla and Custard Apple Tree

With respect to rainwater use efficiency (RWUE), the custard apple based agri–horti system recorded the highest mean RWUE, ranging from 5.69 to 7.02 kg ha mm⁻¹, with significantly higher values observed under the custard apple + blackgram combination and statistically comparable performance under the custard apple + greengram system (

Figure 19). The superior RWUE of custard apple may be attributed to its deeper and more efficient root system, enhanced stomatal regulation, and better synchronization of vegetative and reproductive growth with rainfall events, enabling more effective conversion of available rainwater into economic yield (Kowitcharoen et al.

, 2025; Marappan et al.

, 2025). The markedly higher RWUE observed under the custard apple + blackgram system further reflects complementary interactions between the tree and the legume intercrop. The results also aligned with the studies of Marotti et al., 2022; Franco-Navarro et al.

, 2022. Biological nitrogen fixation by blackgram improves soil nutrient availability, which in turn enhances photosynthetic efficiency and yield per unit of rainwater received (Qiu

et al., 2022; Liu et al.

, 2022).

In contrast, the aonla-based agri–horti system recorded a comparatively lower mean RWUE, ranging from 4.29 to 5.45 kg ha mm⁻¹ during the experimental period (2022–23 to 2024–25). This lower efficiency may be attributed to a relatively weaker fruit yield response to rainfall in aonla compared to custard apple, resulting in reduced conversion of rainfall into economic yield and, consequently, lower RWUE values (Singh et al., 2019).

3.3. Performance of Cropping System

3.3.1. System Productivity Based on Blackgram Equivalent Yield (kg/ha):

System productivity in intercropping represents the combined yield advantage achieved by cultivating two or more components on the same land unit and reflects the efficiency with which available resources such as light, water, nutrients, and space are utilized relative to sole cropping. In the present study, system productivity was expressed as blackgram equivalent yield (BEY), integrating the yield contributions of both intercrops and fruit trees. The results clearly demonstrated that custard apple based intercropping systems exhibited superior system productivity, with BEY values ranging from 1337 to 3019 kg ha⁻¹, whereas the aonla based systems recorded comparatively lower values, ranging from 891 to 2447 kg ha⁻¹ over the study period (

Figure 20). The higher productivity observed under custard apple based systems may be attributed to enhanced light penetration, improved rainwater infiltration, and more efficient nutrient cycling, which together created a favourable microclimate for intercrop growth and yield expression (Vishwakarma

et al., 2024; Chandrakar

et al., 2014).

Among the different intercropping combinations, custard apple + cluster bean recorded the highest system productivity (3019 kg ha⁻¹), representing a 55.71% increase over custard apple grown as a sole crop. The superior performance of this combination can be attributed to the cluster bean, being a vigorous legume with high biomass production potential, likely enhanced soil fertility and contributing substantially intercrop yield (Akchaya et al., 2025; Fuchs et al., 2024). This treatment was statistically at par with custard apple + foxtail millet, indicating comparable efficiency in resource utilization. Foxtail millet’s rapid early growth, efficient water-use efficiency, and ability to exploit residual soil moisture likely contributed to higher grain and biomass yields, thereby enhancing overall system productivity (Aravind et al., 2023).

A similar trend was observed in aonla-based systems, indicating that intercropping, irrespective of the tree species, improved land-use efficiency compared to sole cropping. However, the relatively lower productivity of aonla-based systems may be attributed to denser canopy architecture and greater competitive demand for light and nutrients, which constrained intercrop performance under these systems.

3.3.2. Rain Water Use Efficiency for the Intercropping System

Aonla and custard apple grown under different intercropping systems exerted a significant influence on rainwater use efficiency (RWUE). Across the agri–horti systems evaluated on the basis of system productivity, custard apple based intercropping systems recorded higher mean RWUE values, ranging from 3.06 to 6.50 kg hamm⁻¹, compared with 2.13 to 5.31 kg ha mm⁻¹ under aonla based systems. The superior RWUE observed in custard apple based systems may be attributed to favourable tree–crop interactions that enhanced rainfall utilization efficiency. In particular, the custard apple + cluster bean combination exhibited pronounced improvements in RWUE due to the cluster bean, being a drought-resilient legume, efficiently exploits surface soil moisture and improves soil structure and moisture retention through its root system thereby supporting improved tree growth and higher yield per unit of rainfall received (Ramanjineyulu et al., 2024; Munde et al., 2011).

Among all combinations, custard apple + cluster bean recorded the highest average RWUE (6.50 kg hamm⁻¹), representing a 52.9% increase over custard apple grown as sole crop. A similar trend of enhanced RWUE under intercropping was also observed in aonla-based systems, indicating the positive role of compatible intercrops in improving water-use efficiency under rainfed conditions. The substantial improvement in RWUE under intercropping systems compared to sole cropping highlights improved land and water-use efficiency. Intercrops provide effective ground cover, reduce evaporative losses, and enhance rainwater infiltration, thereby promoting better conservation and utilization of rainfall within agri–horti systems (Li et al., 2025).

3.3.3. Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) for the Intercropping System

Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) is a key index for evaluating land-use efficiency in intercropping systems, as it compares the productivity of component crops grown together with that of the same crops grown separately. In the present study, both aonla and custard apple based intercropping systems consistently recorded LER values exceeding 1.0, demonstrating superior land-use efficiency. This advantage can be attributed to complementary utilization of growth resources such as light, soil moisture, nutrients, and space by the tree and intercrop components (Lal et al., 2018).

Among the treatment combinations, the custard apple + blackgram system recorded the highest mean LER of 2.00, indicating a 100% increase in land-use efficiency over sole cropping (

Figure 21). This superior performance may be attributed to the complementary growth behaviour of the two components. The wider spacing, deeper root system, and relatively open canopy architecture of custard apple allow adequate light penetration, thereby sustaining higher photosynthetic efficiency of the intercrop and creating a favourable micro-environment. (Adam et al.

, 2025; Duchene et al.

, 2017). Furthermore, biological nitrogen fixation by blackgram enhances soil fertility, indirectly supporting tree growth and productivity. These synergistic interactions resulted in markedly higher land-use efficiency compared with sole cropping (Sheelendra Kumar et al.

, 2020).

Similarly, the aonla + blackgram system achieved a high LER value of 1.90, reaffirming strong complementarity and improved resource-use efficiency under these agri horti systems over the three years of experimentation. Owing to these synergistic effects, blackgram-based intercropping consistently resulted in higher fruit yield advantage, improved rainwater use efficiency, and the greatest LER values in both fruit-based systems during the study period. Collectively, the combined effects of improved microclimate, biological nitrogen fixation, and enhanced nutrient cycling contributed to superior land-use efficiency in intercropping systems compared with sole cropping (Mehta et al., 2020; Rhonda et al., 2020).

3.3.4. Economics of Aonla- and Custard Apple–based Intercropping Systems

The cost of cultivation, gross returns, net returns, and benefit–cost (B:C) ratio were estimated for all treatments over three consecutive years of experimentation. The cost of cultivation varied considerably among cropping systems due to differences in input requirements, intercrop management practices, labour intensity, and nutrient and plant protection needs. Overall, the cost of cultivation ranged from ₹30,425 to ₹66,350 ha⁻¹. The observed variation in economic performance of intercropping systems can be attributed to differences in input costs, system productivity, market value of intercrops, and overall resource-use efficiency (

Table 1).

The highest average cost of cultivation was incurred in the aonla / custard apple + clusterbean system (₹66,350 ha⁻¹), followed by the aonla / custard apple + foxtail millet system. In contrast, the lowest costs were recorded under sole fruit cropping, with custard apple (₹30,425 ha⁻¹) and aonla (₹31,417 ha⁻¹). The higher cultivation cost associated with cluster bean-based systems may be attributed to increased expenditure on seed, labour-intensive intercultural operations, and relatively higher nutrient and crop protection inputs. Similarly, foxtail millet based systems incurred additional costs due to intercrop management compared to sole fruit crops (Surendra et al., 2024; Maner et al., 2024).

Gross return analysis revealed that the custard apple + clusterbean system generated the highest three-year average gross returns (₹1,81,160 ha⁻¹), followed by custard apple + foxtail millet (₹1,72,460 ha⁻¹). The superior gross returns under these systems can be attributed to the additive yield advantage obtained from simultaneous harvesting of fruit and intercrops from the same land unit. Clusterbean, being a high-value legume, contributes substantially to system income due to its high yield potential and favourable market price (Surendra et al., 2024). Likewise, foxtail millet, a low-input and drought-tolerant crop, provides stable yields under rainfed conditions (Aravind et al., 2023). In contrast, the lowest gross returns were obtained from sole cropping of aonla (₹53,460 ha⁻¹) and custard apple (₹80,240 ha⁻¹). Under sole systems, inter-row space remains underutilized for a substantial part of the year, resulting in lower productivity per unit area and reduced economic returns (Dharani and Mishra, 2020).

Likewise custard apple + foxtail millet system realized the highest average net income (₹1,28,610 ha⁻¹), followed by custard apple + clusterbean (₹1,14,810 ha⁻¹). These systems generated additional net returns of ₹78,795 ha⁻¹ and ₹64,995 ha⁻¹, respectively, over sole custard apple cropping (₹49,815 ha⁻¹). The superior net returns from the custard apple + foxtail millet system may be attributed to its optimal balance between moderate cultivation cost and consistently high combined yields, resulting in greater profit margins. Foxtail millet requires relatively lower investment. Although clusterbean-based systems generated higher gross returns, their relatively higher cost of cultivation reduced net income, thereby explaining their lower profitability compared to foxtail millet–based systems.

Correspondingly, the highest B:C ratio was recorded in the custard apple + foxtail millet system (3.93), closely followed by custard apple + blackgram (3.92) and custard apple + greengram (3.82). Higher B:C ratios in these systems indicate more efficient conversion of investment into economic returns (Ileana, 2021). Pulses and millet-based intercrops are characterized by lower input requirements, early maturity, and minimal competition with fruit trees, enabling higher profitability without proportionate increases in production costs (Laxmi et al., 2020). In contrast, relatively lower B:C ratios were observed in aonla + clusterbean (2.21) and custard apple + clusterbean (2.73), primarily due to higher input costs and market price fluctuations, despite higher gross returns. Sole cropping of aonla and custard apple resulted in the lowest profitability, with B:C ratios of 1.70 and 2.64, respectively. The poor economic performance under sole fruit cropping reflects inefficient utilization of inter-row space and available resources, leading to lower returns per unit area (Naveen Kumar, 2020). This finding is further supported by earlier reports indicating that clusterbean alone exhibits a modest B:C ratio (1.21), underscoring its limited profitability when not integrated into more efficient agri–horti systems (Bajwan et al., 2023).

3.3.5. System Profitability

System profitability, expressed as net return per hectare per day (₹ ha⁻¹ day⁻¹), varied significantly among the intercropping systems and clearly reflected the economic advantage of agri–horti diversification under rainfed conditions. Custard apple–based systems consistently recorded higher daily profitability than aonla-based systems. Among all treatments, custard apple + foxtail millet achieved the highest average system profitability (₹352.4 ha⁻¹ day⁻¹), followed by custard apple + clusterbean (₹314.6 ha⁻¹ day⁻¹) and custard apple + blackgram (₹306.4 ha⁻¹ day⁻¹) (

Figure 22).

The superior profitability of the custard apple + foxtail millet system was primarily attributed to the short duration, early maturity, low cultivation cost, and efficient utilization of residual soil moisture by foxtail millet, resulting in rapid income generation and higher daily returns (Nadeem et al., 2020). Similarly, the favourable performance of the custard apple + blackgram system can be explained by its moderate input requirement, short crop duration, stable market price, and minimal competitive interaction with the tree component (Vishwakarma et al., 2024).

In contrast, sole cropping of aonla and custard apple recorded the lowest profitability, yielding only ₹60.4 and ₹136.8 ha⁻¹ day⁻¹, respectively, due to underutilization of inter-row space and limited income generation over time. These results clearly demonstrate that integration of suitable intercrops substantially enhances daily economic returns and reinforces the economic sustainability of diversified agri–horti systems under rainfed conditions (Neetesh et al., 2023).

3.3.6. Relative Economic Efficiency (REE)

Relative Economic Efficiency (REE) quantifies the profitability of an intercropping system relative to sole cropping, reflecting the efficiency of resource use in generating additional net returns. In the present study, the choice of intercrop significantly influenced REE, with aonla-based systems outperforming custard apple–based systems. Among the treatments, aonla + foxtail millet recorded the highest REE (341.2%), indicating a more than threefold increase in economic efficiency over sole aonla cultivation. This was followed by aonla + clusterbean (264.7%) and aonla + blackgram (263.3%) (

Figure 23).

The exceptionally high REE of aonla + foxtail millet can be attributed to the crop’s short duration, low input requirement, high market acceptability, rapid ground coverage, and efficient rainfall utilization, resulting in higher grain yield at minimal cost (Gobikashri et al., 2025). Similarly, aonla + clusterbean benefitted from the legume’s grain and haulm value, biological nitrogen fixation, and low competitive interaction, enhancing net returns (Hussain et al., 2022). The aonla + blackgram system also demonstrated high REE due to moderate management costs, stable market prices, and efficient early-season exploitation of soil resources without adversely affecting tree growth (Murmu et al., 2022). These results highlight that integrating suitable intercrops with aonla substantially improves economic efficiency under rainfed conditions.

3.3.7. Changes in Soil Fertility

Baseline soil analysis at the initiation of the experiments during 2022–23, 2023–24, and 2024–25 revealed pH values of 8.16, 8.17, and 8.15; organic carbon (OC) 3.02, 4.12, and 5.18 g/kg; available nitrogen (N) 160, 164, and 167 kg/ha; available phosphorus (P) 11.3, 11.1, and 11.3 kg/ha; and available potassium (K) 434, 435, and 438 kg/ha, respectively. Post-harvest analysis indicated a slight decline in soil pH (–0.21 to –0.35 units) (

Figure 24), likely due to organic acid release from decomposing leaf litter, intercrop residues, and root exudates, causing localized acidification under otherwise alkaline conditions (Zhang et al.

, 2021; Tang et al.

, 2025).

In contrast, soil organic carbon exhibited consistent improvement, increasing by 1.05–1.76 g/kg at 2024-25 over initial values of 2022-23 (

Figure 25). The enhancement in OC is attributed to continuous biomass inputs from tree litter, pruned materials, root residues, and intercrop biomass, particularly from pulses, which contribute additional below-ground carbon and enhance soil biological activity through nitrogen fixation and nodulated root turnover (Rathore et al.

, 2022; Lorenz and Lal, 2022).

Available nitrogen and potassium also increased over the three years, by 9 to11 kg/ha and 8 to 14 kg/ha, respectively, with the most pronounced improvements observed in pulse-based intercropping systems (

Figure 26 and

Figure 28). The increase in N is primarily due to biological nitrogen fixation by leguminous intercrops such as blackgram and greengram, along with mineralization of N-rich residues and nodules, whereas the enhancement in K results from recycling of potassium-rich leaf litter and plant residues (Murphy et al.

, 2017; Zhao

et al., 2022).

Available phosphorus, however, remained relatively stable across all intercropping systems, (

Figure 27) indicating that native or applied P was either immobilized or utilized by crops without significant accumulation or depletion in the soil (Helfenstein et al.

, 2024).

5. Conclusions

Integration of annual intercrops with Aonla and Custard apple under rainfed conditions significantly enhanced system productivity, economic returns, and resource-use efficiency. Custard apple–based systems consistently outperformed Aonla, owing to a more open canopy, improved light penetration, and favorable microclimatic conditions. Among intercrops, clusterbean and foxtail millet achieved the highest grain, haulm, and blackgram equivalent yields, while pulses (blackgram, greengram) promoted tree growth, soil fertility, and nitrogen enrichment through biological fixation. Rainwater use efficiency and land equivalent ratio were maximized under Custard apple + clusterbean and Aonla + foxtail millet combinations, indicating efficient utilization of water and land resources. Relative Economic Efficiency peaked at 341.2% in Aonla + foxtail millet, highlighting substantial economic gains over sole cropping. Soil analysis revealed slight pH reduction, increased organic carbon, and improved nitrogen and potassium levels, particularly under pulse-based intercropping, whereas phosphorus remained stable. Overall, legume- and millet-based agri–horti systems enhanced crop-tree complementarity, system productivity, profitability, and sustainability under rainfed agro-ecosystems.

Author Contributions

K. B. Sridhar, K. A. Gopinath, and J. V. N. S. Prasad contributed to the conceptualization of the study. M. Joseph and S. Manoharan conducted the investigation, developed the methodology, and prepared the original draft, with primary responsibility for data organization and management. B. Bhakiyathu Saliha assisted in manuscript review, editing, and validation. Data curation was performed by G. Guru, V. Sanjivkumar, and A. Selvarani. Software analysis was carried out by M. Manikandan, and project administration was overseen by Vinod Kumar Singh.

Funding

This research was funded by All India Coordinated Project on Dryland Agriculture (AICRPDA), CRIDA, Hyderabad.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by the lndian Council of Agricultural Research, Department of Agricultural Research and Education, Government of lndia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AICRPDA |

All India Coordinated Research Project on Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad |

| APK |

Aruppukottai |

| CEY |

Crop Equivalent Yield |

| CO |

Coimbatore |

| et al., |

Co workers |

| kg ha⁻¹ |

Kilogram per hectare |

| km h⁻¹ |

Kilometre per hour |

| LAI |

Leaf Area Index |

| LER |

Land Equivalent Ratio |

| mm day⁻¹ |

Millimetre per day |

| N: P₂O₅: K₂O |

Nitrogen: Phosphorus: Potassium |

| REE |

Relative economic efficiency |

| RWUE |

Rainwater Use Efficiency |

| SPAD-502 |

Soil-Plant Analysis Development section, Minolta Camera Co. Ltd., Japan |

| TNAU |

Tamil Nadu Agricultural University |

| VBN |

Vamban |

Appendix A

Figure 1.

(a) Location map of the experimental field at AICRPDA Main centre, Kovilpatti, Tamil Nadu, India. (b) Aerial view of AICRPDA Main centre research field.

Figure 1.

(a) Location map of the experimental field at AICRPDA Main centre, Kovilpatti, Tamil Nadu, India. (b) Aerial view of AICRPDA Main centre research field.

Appendix B

Figure 2.

Weather parameters including soil moisture content during the cropping periods from 2022-23, 2023-24 and 2024-25.

Figure 2.

Weather parameters including soil moisture content during the cropping periods from 2022-23, 2023-24 and 2024-25.

Appendix C

Figure 3.

Layout of Aonla and Custard Apple based Agri-Horti Systems.

- Custard Apple;

- Aonla ; …… Intercrops

Figure 3.

Layout of Aonla and Custard Apple based Agri-Horti Systems.

- Custard Apple;

- Aonla ; …… Intercrops

References

- Adam, A.M.; Giller, K.E.; Rusinamhodzi, L.; Rasche, F.; Koomson, E.; Marohn, C.; Cadisch, G. Enhancing the resilience of intercropping systems to changing moisture conditions in Africa through the integration of grain legumes: A meta-analysis. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 321, 109663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurha, A.; Sahu, G.; Singh, P.; Verma, S. Morphological characterization of indigenous custard apple (Annona squamosa L.) genotypes at Dharsiwa block of Chhattisgarh. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icer, S.U.A.O.; Turon, M.J.; Koly, S.Z.; Shamsuzzoha; Mallick, S.; Das, R.C.; Monira, S.; Ali, I.; Saha, A.; Syfullah, K. Influence of Spacing on Growth and Yield of Blackgram Varieties. Acta Bot. Plantae 2025, 4, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarapalli, G. Studies on the Effect of Water Stress on Root Traits in Green Gram Cultivars. Legum. Res. - Int. J. 2022, 45, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, M.R.; Vaiahnav, S.; Naide, P.R.; Aruna, N.V.; Vishwanath. Long Term Benefits of Legume Based Cropping Systems on Soil Health and Productivity. An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2022, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, K.; Vadivel, N.; Kumar, G.S.; Ravichandran, V.; Bharathi, C. Performance of Foxtail Millet based Intercropping System for Improving the Productivity, Sustainability and Economics in Western Zone of Tamil Nadu Under Irrigated Conditions. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2023, 35, 1824–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Kumar, A.; Pourouchottamane, R. Pearl Millet and Cluster Bean Intercropping for Enhancing Fodder Productivity, Profitability and Land Use Efficiency. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2022, 51, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, O.P.; Singh, I.S.; More, T.A. Performance of intercrops during establishment phase of aonla (Emblica officinalis) orchard. The Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2011, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi, P. Intercropping in fruit orchards: A way forward for doubling the farmer’s income. International Journal of Agriculture Sciences 2019, 0975–3710. Available online: https://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217.

- Banerjee, P.; Venugopalan, V.K.; Nath, R.; Althobaiti, Y.S.; Gaber, A.; Al-Yasi, H.; Hossain, A. Physiology, Growth, and Productivity of Spring–Summer Black Gram (Vigna mungo L. Hepper) as Influenced by Heat and Moisture Stresses in Different Dates of Sowing and Nutrient Management Conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Chakraborty, P.K.; Nath, R.; Chakraborty, P.K. Thermal indices: Impact on phenology and seed yield of spring-summer greengram [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] under different dates of sowing. J. Pharm. Phytochem 2018, 2, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yumbya, B.M.; Kitonyo, O.M.; Kinama, J.M. Green Gram-sorghum Intercropping: Effects on Crop Microclimate, Competition, Resource Use Efficiency and Yield in Southeastern, Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadani, M.; Das, D.K.; Rai, T.M.; Bhadani, S.K. Effect of Morphological Characteristics of Fruit Orchards on Soil Physio-chemical Properties. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2023, 35, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.K.; Sharma, K.; Pant, K.S.; Singh, S.; Prakash, P.; Kumar, P.; Saakshi; Sharma, H. Economic Profitability and Carbon Stock Potential of Cereals and Pulses Under Harar and Aonla Based Agroforestry Systems in The Low Hill Zone of Himachal Pradesh. Int. J. Econ. Plants 2022, 9, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharani, B.; Pusam, B. Influence of Inter Cropping Systems on Physio-Chemical Properties of Soil in Aonla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn L.) Plantation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 3039–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharani, B.; Mishra, S. Studies on Economic Feasibility and Suitability of Intercrops in Aonla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn L.) Plantation. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, M.S.; Mahajan, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Sharma, V.K. A high-quality genome assembly of Annona squamosa (custard apple) provides functional insights into an emerging fruit crop. DNA Res. 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinael, R.; Cadisch, G.; Gosme, M.; Oelbermann, M.; van Noordwijk, M. Climate change mitigation and adaptation in agriculture: Why agroforestry should be part of the solution. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 319, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakar; Lal, Hem; Chandrakar, Komal; Ujjaini, Manas; Yadav, K. C. The effect of fertilization on growth & yield of rain fed blackgram in custard apple based agri-horti-system with alley cropping pattern on vindhyan soil. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ 2014, 4, 2250–3153. [Google Scholar]

- Kour, D.; Wali, V.K.; Bakshi, P.; Bhat, D.J.; Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, V.; Sinha, B.K. Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management Strategies on Nutrient Status and Soil Microbial Population in Aonla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) Cv. Na-7. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Anup; Layek, Jayanta; Babu, Subhash; Krishnappa, R.; Thoithoi Devi, M.; Kumar, Amit; Patel, D. P.; et al. “Division of Crop Production ICAR Research Complex for NEH Region Umiam–793 103, Meghalaya, India.” Technical bulletin (2019).

- Thirumal, Dhivyalakshmi; Sharmili, K.; Praveena Katharine, S.; Silambarasan, M.; Dinesh Kumar, P.; Kousalya, A.; Gobikashri, N. Scientific Study on Vrikshayurvedic Farming in Greengram. Biological Forum – An International Journal 2023, 15, 525–528. [Google Scholar]

- Dugassa, M. Intercropping as a multiple advantage cropping system: Review. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2023, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Padilla, Y.G.; Álvarez, S.; Calatayud, Á.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Gómez-Bellot, M.J.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Alcalá, I.; Penella, C.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; et al. Advancements in Water-Saving Strategies and Crop Adaptation to Drought: A Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.; Silva, P. Sustainable Agricultural Systems for Fruit Orchards: The Influence of Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria on the Soil Biodiversity and Nutrient Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K.; Kraus, D.; Houska, T.; Kermah, M.; Haas, E.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Scheer, C. Intercropping Legumes Improves Long Term Productivity and Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobikashri, N.; Kumar, K.U.; Nivetha, C.; Punithkumar, S.; Kousalya, A.; Flora, G.J.; Dhivyalakshimi, T.; Jeyasingh, R.A.I. A brief review on world of foxtail millet: From botanical characteristics to market trends. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical procedures for agricultural research; John wiley & sons, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, X.; Reich, P.B.; Qiu, L.; Shao, M.; Wei, G.; Wang, J.; Wei, X. Leguminous plants significantly increase soil nitrogen cycling across global climates and ecosystem types. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 4028–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, P.; Ravi, R.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Boominathan, P.; Selvanayaki, S.; Radha, P.; Baranidharan, K.; Divya, M. Assessment of Yield Performance of Cluster Bean cultivars in Melia dubia-based Agroforestry Systems. Legum. Res. - Int. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, H.; Kumar, P.; Banyal, V.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, N. Driving sustainability in fruit-based cropping Systems: Intercropping impacts on growth, soil health, microbial dynamics and yield stability. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Li, C.; Cai, Y.; Song, X.; Zhao, X. Intercropping increases plant water availability and water use efficiency: A synthesis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 379, 109360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Ali, M.; Ghoneim, A.M.; Shahzad, K.; Farooq, O.; Iqbal, S.; Nawaz, F.; Ahmad, S.; Bárek, V.; Brestic, M.; et al. Improvement in growth and yield attributes of cluster bean through optimization of sowing time and plant spacing under climate change scenario. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 29, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAR–AICRP on Arid Zone Fruits case report “Post-Harvest Management of Custard Apple Enhanced livelihood of Tribal Communities in Southern Rajasthan”. ICAR 2025.

- Ileana, D. Custard Apple-Best Companion Fruit Crop for Mixed Fruit Cropping. International Journal of Researches in Biosciences and Agriculture Technology. International Journal of Research in Bioscience & Agriculture Technology (IJRBAT) 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, Ishwarya; Krishna, A; Madhavi Lata, A; Madhavi, A. Evaluation of pulses and millets in agri-silvi system. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2020, 9, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Jagdish, 2023. Unleashing the potential of custard apple intercropping to double farmer’s income. AgriFarming. Available online: https://www.agrifarming.in/unleashing-the-potential-of-custard-apple-intercropping-to-double-farmers-income.

- Janke, R.R.; Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Al Hamdi, A.; Rehman, A. Organic Management and Intercropping of Fruit Perennials Increase Soil Microbial Diversity and Activity in Arid Zone Orchard Cropping Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ren, J.; Liu, S.; Qiao, Z.; Cao, X. Effects of Nitrogen Application Rate on Yield and Quality of Different Genotypes of Foxtail Millet. Phyton 2024, 93, 3487–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfenstein, J.; Ringeval, B.; Tamburini, F.; Mulder, V.L.; Goll, D.S.; He, X.; Alblas, E.; Wang, Y.; Mollier, A.; Frossard, E. Understanding soil phosphorus cycling for sustainable development: A review. One Earth 2024, 7, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akchaya, K.; Parasuraman, P.; Pandian, K.; Vijayakumar, S.; Thirukumaran, K.; Mustaffa, M.R.A.F.; Rajpoot, S.K.; Choudhary, A.K. Boosting resource use efficiency, soil fertility, food security, ecosystem services, and climate resilience with legume intercropping: a review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1527256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Contribution, Utilization, and Improvement of Legumes-Driven Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Agricultural Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokila, A.; Nagarajaiah, C.; Hanumanthappa, D.C.; Shivanna, B.; Sathish, K.; Mahadevamurthy, M. Effect of Tree Canopy Cover on Soil Moisture Dynamics in Different Agroforestry Systems under Semi-arid Condition. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, K.; Vadivel, N.; Kumar, G.S.; Ravichandran, V.; Bharathi, C. Performance of Foxtail Millet based Intercropping System for Improving the Productivity, Sustainability and Economics in Western Zone of Tamil Nadu Under Irrigated Conditions. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2023, 35, 1824–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitcharoen, L.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Setha, S.; Komkhuntod, R.; Srilaong, V.; Kondo, S. Physiological changes of fruit and C/N ratio in sugar apples (Annona squamosa L.) under drought conditions. Acta Hortic. 2017, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Pareek, N.; Rathore, V.; Nangia, V.; Kumawat, A.; Kumar, A.; Pareek, B.; Meena, M. Performance of Cluster Bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) under Varying Levels of Irrigation and Nitrogen. Legum. Res. - Int. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, A.S.; Rawat, G.S.; Gupta, S.; Patil, D.; Prajapati, N. Production and profitability assessment of clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L. Taub.) based intercropping systems under different row arrangement. Legum. Res. - Int. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Meena; Kumar, S.; Meena, R.; Pal, V.; Lawate, P. Effect of Crop Diversification on Growth and Yield of Pearlmillet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) under Custard Apple (Annona squamosa L.) Based Rainfed Agri-Horti System. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 12, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Qi, G.; Yin, M.; Kang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lv, H.; et al. Water-saving strategies in intercropping systems: Integrated effects of water regulation and planting patterns on root-canopy coordination and agricultural water productivity. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration. In Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration in Terrestrial Biomes of the United States; Springer: Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, G.; Tian, J.; Jia, Y.; Chu, Y.; Yue, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Assessing and Quantifying the Carbon, Nitrogen, and Enzyme Dynamics Effects of Inter-row Cover Cropping on Soils and Apple Tree Development in Orchards. HortScience 2024, 59, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, Sagar & Sairam, Masina & Kalasare, Rajesh & Gaikwad, Dinkar & Raghava, Chabolu Venkata & Krishna, Tadiboina Gopala & Sahoo, Upasana. (2024). Role of Legume-based Intercropping System in Soil Health Improvement.

- Maner, K.; Bhosale, S.; Jain, A.; Kadam, J. Economics of production and disposal of Aonla in Sindhudurg district of Maharashtra. Int. J. Agric. Ext. Soc. Dev. 2024, 7, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marappan, K.; Sadasivam, S.; Natarajan, N.; Arumugam, V.A.; Lakshmaiah, K.; Thangaraj, M.; Gopal, M.G.; Asokan, A. Underutilized fruit crops as a sustainable approach to enhancing nutritional security and promoting economic growth. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1618112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotti, I.; Whittaker, A.; Bağdat, R.B.; Akin, P.A.; Ergün, N.; Dinelli, G. Intercropping Perennial Fruit Trees and Annual Field Crops with Aromatic and Medicinal Plants (MAPs) in the Mediterranean Basin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugassa, M. Intercropping as a multiple advantage cropping system: Review. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2023, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, B.; Gonçalves, A.; Pinto, L.; Prieto, M.A.; Carocho, M.; Caleja, C.; Barros, L. Intercropping Systems: An Opportunity for Environment Conservation within Nut Production. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munde, G.R.; Hiwale, B.G.; Nainwad, R.V.; Dheware, R.M. Effect of intercrops on growth and yield of custard apple. 2011, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Murmu, Suren; Padhi, Gayatri Kumari; Murmu, Paritosh; Roy, Debjit; Dhara, Pratap Kumar. Potential of Different Fruit-Based Agroforestry Models for Improving Livelihood in Humid and Subtropical Regions of India. Indian J Ecol 2022, 49, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Bokern, D.; Peeters, A.; Westhoek, H. doi:10.1079/9781780644981.0018, (18–36), CABI, The role of legumes in bringing protein to the table., (2017).

- Shah, M.H.; Dutt, V.; Bhat, S.; Dar, Z.A.; Khanday, M.U.D. Characteristics of Soil under Greengram-Plum based Agroforestry System in Kashmir Valley, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Wang, R.; Han, J.; Shen, Q.; Chang, F.; Diao, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, X. Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) Beauv.] Grown under Low Nitrogen Shows a Smaller Root System, Enhanced Biomass Accumulation, and Nitrate Transporter Expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Hassan, M.U.; Wang, R.; Diao, X.; Li, X. Adaptation of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) to Abiotic Stresses: A Special Perspective of Responses to Nitrogen and Phosphate Limitations. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.N. Effect of Intercropping on Fruit Crops: A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayana, H.N.; Umesh, K.; Ramu, M.S. Production and value addition of climate-smart millets: An economic analysis in eastern dry zone of Karnataka, India. The Pharma Innovation. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]