Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Types of Symmetries in Nuclear Physics

2.1. Fundamental Space-Time Symmetries

2.2. Collective Symmetries

2.3. Isospin Symmetry and Charge Symmetry

2.4. Pseudospin, F-Spin, and Other Specialized Symmetries

2.5. Chiral Symmetry and QCD-Inspired Symmetries

2.6. Symmetry Breaking and Restoration in Nuclei

3. Experimental Methodologies and Technical Capabilities

3.1. Heavy-Ion Collisions and the Symmetry Energy

3.2. Charge-Exchange Reactions and Spin-Isospin Probes

3.3. Beta Decay and Weak-Interaction Observables

3.4. Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy and Lifetime Measurements

3.5. Parity-Violating Electron Scattering

3.6. Radioactive Ion Beams and Exotic Nuclei

3.7. Precision Mass Measurements and Isospin Structure

3.8. Experimental Limitations and Systematic Uncertainties

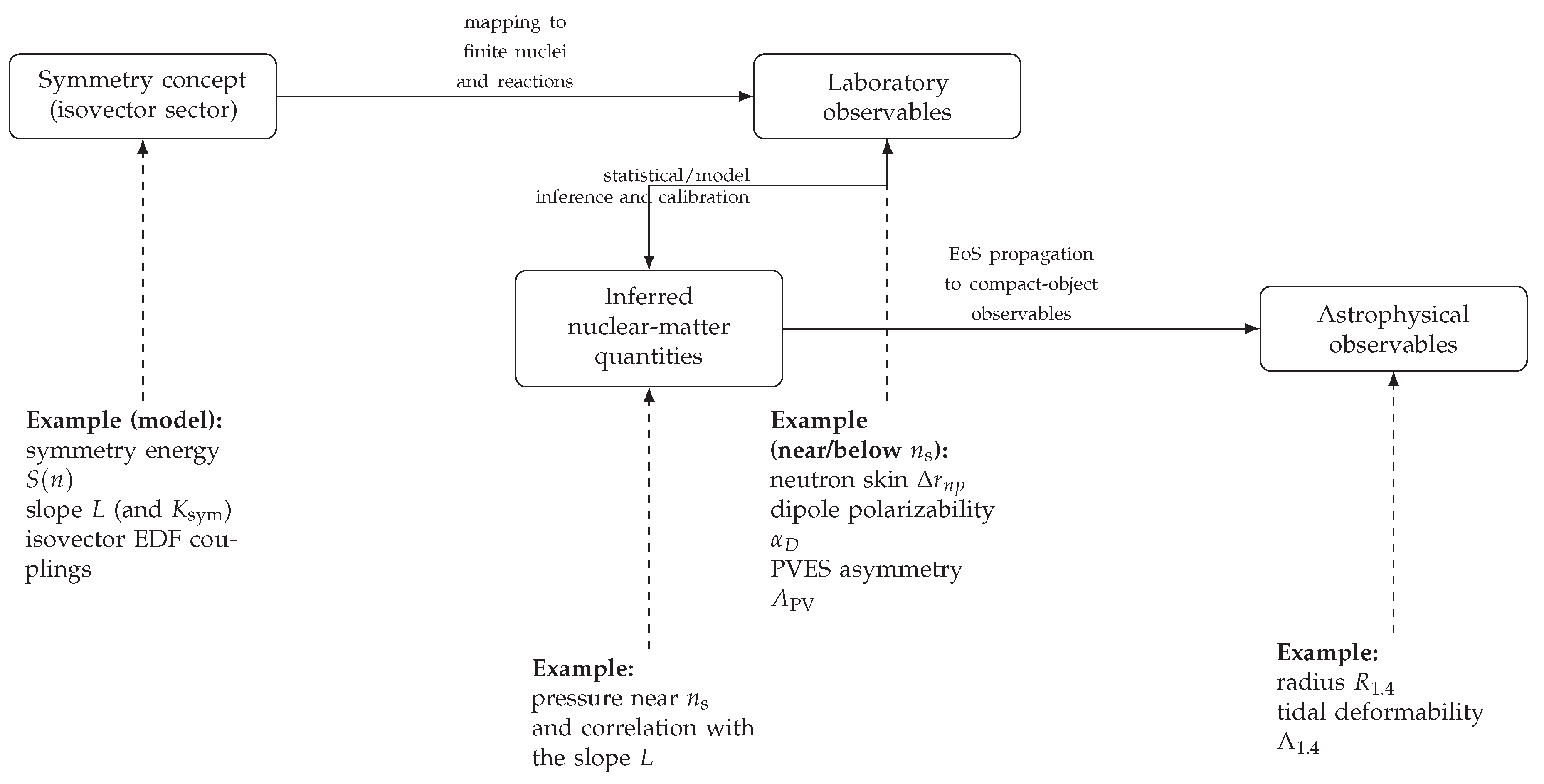

4. Symmetry Energy and Nuclear Astrophysics

4.1. Symmetry Energy at and Below Saturation Density

4.2. Heavy-Ion Collisions and Symmetry Energy at Finite Temperature

4.3. Symmetry Energy, Neutron Stars, and Dense Matter

4.4. Multimessenger Constraints and Consistency Across Scales

5. Precision Symmetry Tests and Frontiers Beyond the Standard Model

5.1. Time-Reversal Violation and Electric Dipole Moments

5.2. Neutrinoless Double-Beta Decay and Lepton-Number Violation

5.3. Parity Violation and Electroweak Symmetry Tests

5.4. CPT Symmetry and Precision Antimatter Spectroscopy

5.5. Radioactive Molecules as Precision Symmetry Probes

5.6. Future Directions in Symmetry Tests

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noether, E.; Tavel, M.A. Invariante Variationsprobleme. Nachr. Ges. Wiss. Göttingen, Math.-Phys. Kl. English translation;Transp. Theory Stat. Phys. 1971, 1, 183–207.. 1918, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chupp, T.E.; Fierlinger, P.; Ramsey-Musolf, M.J.; Singh, J.T. Electric dipole moments of atoms, molecules, nuclei, and particles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019, 91, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Ramsey-Musolf, M.J.; van Kolck, U. Electric Dipole Moments of Nucleons, Nuclei, and Atoms: The Standard Model and Beyond. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2013, 71, 21–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, M.S.; Budker, D.; DeMille, D.; Kimball, D.F.J.; Derevianko, A.; Clark, C.W. Search for New Physics with Atoms and Molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. Über den Bau der Atomkerne. I. Z. Phys. 1932, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E.P. On the Consequences of the Symmetry of the Nuclear Hamiltonian on the Spectroscopy of Nuclei. Phys. Rev. 1937, 51, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A.; Opper, A.K.; Stephenson, E.J. Charge Symmetry Breaking and QCD. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2006, 56, 253–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M.A.; Lenzi, S.M. Coulomb energy differences between high-spin states in isobaric multiplets. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2007, 59, 497–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeucci, T.N.; Goulding, C.A.; Carey, T.A.; et al. The (p,n) reaction as a probe of beta decay strength. Nucl. Phys. A 1987, 469, 125–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterfeld, F. Nuclear spin and isospin excitations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1992, 64, 491–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, M.; Sakai, H.; Wakasa, T. Spin–isospin responses via (p,n) and (n,p) reactions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2006, 56, 446–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P. Collective Motion in the Nuclear Shell Model. I. Classification Schemes for States of Mixed Configurations. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1958, 245, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.P. Collective Motion in the Nuclear Shell Model. II. The Introduction of Intrinsic Wave-Functions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1958, 245, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.J.; Wood, J.L. Fundamentals of Nuclear Models: Foundational Models; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launey, K.D.; Dytrych, T.; Draayer, J.P. Symmetry-Guided Large-Scale Shell-Model Theory. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2016, 89, 101–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietralla, N.; von Brentano, P.; Lisetskiy, A.F. Experiments on multiphonon states with proton–neutron mixed symmetry in vibrational nuclei. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2008, 60, 225–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginocchio, J.N. Pseudospin as a Relativistic Symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Isacker, P.; Heyde, K.; Jolie, J.; Sevrin, A. The F-spin symmetric limits of the neutron-proton interacting boson model. Ann. Phys. 1986, 171, 253–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, A.E.L.; van Isacker, P. The symmetry energy in nuclei and in nuclear matter. Eur. Phys. J. A 2007, 32, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebeler, K.; Holt, J.D.; Menéndez, J.; Schwenk, A. Nuclear Forces and Their Impact on Neutron-Rich Nuclei and Neutron-Rich Matter. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2015, 65, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drischler, C.; Furnstahl, R.J.; Meléndez, J.A.; Phillips, D.R. How Well Do We Know the Neutron-Matter Equation of State at the Densities Inside Neutron Stars? A Bayesian Approach with Correlated Uncertainties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 202702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Maza, X.; Paar, N. Nuclear Equation of State from Ground and Collective Excited State Properties of Nuclei. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2018, 101, 96–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, C.J.; Ahmed, Z.; Jen, C.-M.; et al. Weak Charge Form Factor and Radius of 208Pb through Parity Violation in Electron Scattering. Phys. Rev. C 2012, 85, 032501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.B.; Stone, J.R.; Camera, F.; Danielewicz, P.; Gandolfi, S.; Hebeler, K.; Horowitz, C.J.; Lee, J.; Lynch, W.G.; et al. Constraints on the symmetry energy and neutron skins from experiments and theory. Phys. Rev. C 2012, 86, 015803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Steiner, A.W. Constraints on the Symmetry Energy Using the Mass-Radius Relation of Neutron Stars. Eur. Phys. J. A 2014, 50, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Prakash, M. The Physics of Neutron Stars. Science 2004, 304, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, M.; Hempel, M.; Klähn, T.; Typel, S. Equations of State for Supernovae and Compact Stars. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Abbott; B.P; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annala, E.; Gorda, T.; Kurkela, A.; Vuorinen, A. Gravitational-Wave Constraints on the Neutron-Star Matter Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 172703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.E.; Watts, A.L.; Bogdanov, S.; Ray, P.S.; Guillot, S.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Ballantyne, D.R.; Belloni, T.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Bilous, A.V.; et al. A NICER View of PSR J0030+0451: Millisecond Pulsar Parameter Estimation. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 887, L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.A.; Krastev, P.G.; Wen, D.H.; Zhang, N.B. Towards Understanding the Astrophysical Effects of Nuclear Symmetry Energy. Eur. Phys. J. A 2019, 55, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattoyev, F.J.; Piekarewicz, J.; Horowitz, C.J. Neutron Skins and Neutron Stars in the Multimessenger Era. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 172702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Rubio, B.; Gelletly, W. Spin–isospin excitations probed by strong, weak and electromagnetic interactions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2011, 66, 549–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, H.; Rubio, B.; Gelletly, W.; Blank, B. Gamow–Teller Transitions — a Mirror Reflecting Nuclear Structure. Acta Phys. Pol. B 2012, 43, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Fujita, Y.; Adachi, T.; et al. Isospin mixing of the isobaric analog state studied in a high-resolution 56Fe(3He,t)56Co reaction. Phys. Rev. C 2013, 88, 054329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, F.; Fujita, Y.; Fujita, H.; Cappuzzello, F.; Ganioğlu, E.; et al. High-resolution study of the Gamow–Teller (GT-) strength in the 64Zn(3He,t)64Ga reaction. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 99, 054322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaum, K. High-accuracy mass spectrometry with stored ions. Phys. Rep. 2006, 425, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.; Moore, I.D.; Pearson, M.R. Laser spectroscopy for nuclear structure physics. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2016, 86, 127–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, Y.A.; Bosch, F. Beta decay of highly charged ions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2011, 74, 016301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palit, R.; Saha, S.; Sethi, J.; Trivedi, T.; Sharma, S.; Naidu, B.S.; Jadhav, S.; Donthi, R.; Chavan, P.B.; Tan, H.; Hennig, W. A high speed digital data acquisition system for the Indian National Gamma Array at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2012, 680, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korten, W.; Atac, A.; Beaumel, D.; Bednarczyk, P.; Bentley, M.A.; Benzoni, G.; Boston, A.; Bracco, A.; Cederkäll, J.; Cederwall, B.; et al. (the AGATA Collaboration) Physics opportunities with the Advanced Gamma Tracking Array: AGATA. Eur. Phys. J. A 2020, 56, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, A.; Spieker, M.; Werner, V.; Ahn, T.; Anagnostatou, V.; Cooper, N.; Derya, V.; Elvers, M.; Endres, J.; Goddard, P.; Heinz, A.; Hughes, R.O.; Ilie, G.; Mineva, M.N.; Petkov, P.; Pickstone, S.G.; Pietralla, N.; Radeck, D.; Ross, T.J.; Savran, D.; Zilges, A. Mixed-Symmetry Octupole and Hexadecapole Excitations in the N=52 Isotones. Phys. Rev. C 2014, 90, 051302(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelbaum, E.; Hammer, H.-W.; Meißner, U.-G. Modern Theory of Nuclear Forces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 1773–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dine, M.; Kusenko, A. The Origin of the Matter–Antimatter Asymmetry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 76, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riotto, A.; Trodden, M. Recent Progress in Baryogenesis. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 1999, 49, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.D.; Yang, C.N. Question of Parity Conservation in Weak Interactions. Phys. Rev. 1956, 104, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Ambler, E.; Hayward, R.W.; Hoppes, D.D.; Hudson, R.P. Experimental Test of Parity Conservation in Beta Decay. Phys. Rev. 1957, 105, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüders, G. On the Equivalence of Invariance under Time Reversal and under Particle–Antiparticle Conjugation for Relativistic Field Theories. Dan. Mat. Fys. Medd. 1954, 28(No. 5). [Google Scholar]

- Pauli, W. Exclusion Principle, Lorentz Group and Reflection of Space-Time and Charge. In Niels Bohr and the Development of Physics; Pauli, W., Ed.; Pergamon Press: London, UK, 1955; pp. 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- et al.; Navas; S; et al. (Particle Data Group) Review of Particle Physics. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.J.; Xu, X.X.; Lin, C.J.; Lee, J.; Hou, S.Q.; Yuan, C.X.; Li, Z.H.; José, J.; et al.; He; J.J; et al. (RIBLL Collaboration) β-Decay Spectroscopy of 27S. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 99, 064312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M.A.; Lenzi, S.M.; Simpson, S.A.; Diget, C.Aa. Isospin-Breaking Interactions Studied through Mirror Energy Differences. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 92, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, N. Coulomb Effects in Nuclear Structure. Phys. Rep. 1983, 98, 273–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrman, J.B. On the Displacement of Corresponding Energy Levels of 13C and 13N. Phys. Rev. 1951, 81, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.G. An Analysis of the Energy Levels of the Mirror Nuclei, 13C and 13N. Phys. Rev. 1952, 88, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCormick, M.; Audi, G. Evaluated Experimental Isobaric Analogue States from T=1/2 to T=3 and Associated IMME Coefficients. Nucl. Phys. A 2014, 925, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Heenen, P.-H.; Reinhard, P.-G. Self-consistent mean-field models for nuclear structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 121–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harakeh, M.N.; van der Woude, A. Giant Resonances: Fundamental High-Frequency Modes of Nuclear Excitation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-19-851733-7. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, U.; Colò, G. The Compression-Mode Giant Resonances and Nuclear Incompressibility. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2018, 101, 55–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarewicz, J. Pygmy Dipole Resonance as a Constraint on the Neutron Skin of Heavy Nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2006, 73, 044325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savran, D.; Aumann, T.; Zilges, A. Experimental Studies of the Pygmy Dipole Resonance. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2013, 70, 210–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, P.-G.; Nazarewicz, W. Information Content of a New Observable: The Case of the Nuclear Neutron Skin. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 81, 051303(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamii, A.; Poltoratska, I.; von Neumann-Cosel, P.; Fujita, Y.; Adachi, T.; Bertulani, C.A.; et al. Complete Electric Dipole Response and the Neutron Skin in 208Pb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 062502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarewicz, J.; Agrawal, B.K.; Colò, G.; Nazarewicz, W.; Paar, N.; Reinhard, P.-G.; Roca-Maza, X.; Vretenar, D. Electric Dipole Polarizability and the Neutron Skin. Phys. Rev. C 2012, 85, 041302(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginocchio, J.N. Relativistic symmetries in nuclei and hadrons. Phys. Rep. 2005, 414, 165–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Meng, J.; Zhou, S.-G. Hidden Pseudospin and Spin Symmetries and Their Origins in Atomic Nuclei. Phys. Rep. 2015, 570, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iachello, F.; Arima, A. The Interacting Boson Model; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Coquard, L.; Pietralla, N.; Rainovski, G.; Ahn, T.; Bettermann, L.; Carpenter, M.P.; Janssens, R.V.F.; Leske, J.; Lister, C.J.; et al. Evolution of the Mixed-Symmetry 21,ms+ Quadrupole-Phonon Excitation from Spherical to γ-Soft Xe Nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 82, 024317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, M.; Horiuchi, H.; Kanada-En’yo, Y.; Lee, D.; Meißner, U.-G. Microscopic Clustering in Light Nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, T.; Delfino, A.; Tomio, L.; Yamashita, M.T. Universal Aspects of Light Halo Nuclei. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2012, 67, 939–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyde, K.; Wood, J.L. Shape Coexistence in Atomic Nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1467–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauendorf, S.; Macchiavelli, A.O. Overview of neutron–proton pairing. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2014, 78, 24–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederwall, B.; Ghazi Moradi, F.; Bäck, T.; Johnson, A.; Blomqvist, J.; Clément, E.; et al. Evidence for a Spin-Aligned Neutron–Proton Paired Phase from the Level Structure of 92Pd. Nature 2011, 469, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmi, I. Simple Models of Complex Nuclei: The Shell Model and Interacting Boson Model; Harwood Academic Publishers: Chur, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. Nuclear Forces from Chiral Lagrangians. Phys. Lett. B 1990, 251, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Effective Chiral Lagrangians for Nucleon–Pion Interactions and Nuclear Forces. Nucl. Phys. B 1991, 363, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machleidt, R.; Entem, D.R. Chiral Effective Field Theory and Nuclear Forces. Phys. Rep. 2011, 503, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, H. Nuclear currents in chiral effective field theory. Eur. Phys. J. A 2020, 56, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, H.-W.; König, S.; van Kolck, U. Nuclear Effective Field Theory: Status and Perspectives. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P.; Schuck, P. The Nuclear Many-Body Problem. In Theoretical and Mathematical Physics; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; ISBN 3-540-09820-8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.A.; Chen, L.W.; Ko, C.M. Recent Progress and New Challenges in Isospin Physics with Heavy-Ion Reactions. Phys. Rep. 2008, 464, 113–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, V.; Colonna, M.; Greco, V.; Di Toro, M. Reaction Dynamics with Exotic Beams. Phys. Rep. 2005, 410, 335–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.B.; Liu, T.X.; Shi, L.; et al. Isospin Diffusion and the Nuclear Symmetry Energy in Heavy-Ion Reactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 062701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aumann, T.; Bertulani, C.A.; Schindler, F.; Typel, S. Peeling Off Neutron Skins from Neutron-Rich Nuclei: Constraints on the Symmetry Energy from Neutron-Removal Cross Sections. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 262501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, P.; Lacey, R.; Lynch, W.G. Determination of the Equation of State of Dense Matter. Science 2002, 298, 1592–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-A.; Ramos, À.; Verde, G.; Vidaña, I. Topical Issue on Nuclear Symmetry Energy. Eur. Phys. J. A 2014, 50, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, B.-A.; Chen, L.-W.; Yong, G.-C.; Zhang, M. Circumstantial Evidence for a Soft Nuclear Symmetry Energy at Suprasaturation Densities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 062502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.-G.; Yong, G.-C.; Chen, L.-W.; Li, B.-A.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, G.-Q.; Xu, N. Probing Nuclear Symmetry Energy at High Densities Using Pion, Kaon, Eta and Photon Productions in Heavy-Ion Collisions. Eur. Phys. J. A 2014, 50, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, G.; Gaitanos, T.; Colonna, M.; Di Toro, M.; Wolter, H.H. Isospin Effects on Subthreshold Kaon Production at Intermediate Energies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 202301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, G.-C.; Li, B.-A.; Chen, L.-W. Neutron–Proton Bremsstrahlung from Intermediate-Energy Heavy-Ion Reactions as a Probe of the Nuclear Symmetry Energy? Phys. Lett. B 2008, 661, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russotto, P.; Gannon, S.; Kupny, S.; Lasko, P.; Acosta, L.; Adamczyk, M.; Al-Ajlan, A.; Al-Garawi, M.; Al-Homaidhi, S.; et al. Results of the ASY-EoS Experiment at GSI: The Symmetry Energy at Suprasaturation Density. Phys. Rev. C 2016, 94, 034608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Chiga, N.; Isobe, T.; Kondo, Y.; Kubo, T.; Kusaka, K.; Motobayashi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Ohnishi, J.; Okuno, H.; Otsu, H.; Sako, T.; Sato, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Sekiguchi, K.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, R.; Yoneda, K. SAMURAI Spectrometer for RI Beam Experiments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2013, 317, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Ahn, D.S.; Ahn, J.K.; Bae, J.; Bae, Y.; Bok, J.S.; Choi, S.W.; Do, S.; Heo, C.; Huh, J.; Hwang, J.; Jang, Y.; Kang, B.; Kim, A.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, C.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, H.M.; Yang, H.M.; et al. Status of LAMPS at RAON. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2023, 541, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, M.; Akimune, H.; Daito, I.; Fujimura, H.; Fujita, Y.; Hatanaka, K.; Ikegami, H.; Katayama, I.; Nagayama, K.; Matsuoka, N.; Morinobu, S.; Noro, T.; Yoshimura, M.; Sakaguchi, H.; Sakemi, Y.; Tamii, A.; Yosoi, M. Magnetic Spectrometer Grand Raiden. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1999, 422, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveling, R. Opportunities with the K600 Magnetic Spectrometer During Phase 1 of the iThemba LABS RIB Project. In Exotic Nuclei IASEN-2013: Proceedings of the First International African Symposium on Exotic Nuclei; Cherepanov, E., Penionzhkevich, Y., Kamanin, D., Bark, R., Cornell, J., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2015; pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.-W.; Tsang, M.B.; Wolter, H.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Aichelin, J.; et al. Understanding Transport Simulations of Heavy-Ion Collisions at 100A and 400A MeV: Comparison of Heavy-Ion Transport Codes under Controlled Conditions. Phys. Rev. C 2016, 93, 044609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, M.; Pereira, J.; Bazin, D.; Ayyad, Y.; Cerizza, G.; Fox, R.; Zegers, R.G.T. Development of a novel MPGD-based drift chamber for the NSCL/FRIB S800 spectrometer. JINST 2020, 15, P03025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimbara, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, K.; et al. High-Resolution Study of Gamow–Teller Transitions with the 37Cl(3He,t)37Ar Reaction. Phys. Rev. C 2012, 86, 024312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langanke, K.; Martínez-Pinedo, G. Nuclear Weak-Interaction Processes in Stars. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 819–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.C.; Towner, I.S. Superallowed 0+→0+ nuclear beta decays: 2020 critical survey, with implications for Vud and CKM unitarity. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 102, 045501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, J.; Ponsaers, J.; Raabe, R.; Huyse, M.; Van Duppen, P.; et al. β-Decay Studies with an Implantation Technique. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2008, 266, 4652–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, B.; Borge, M.J.G. Nuclear Structure at the Proton Drip Line: Advances with Nuclear Decay Studies. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2008, 60, 403–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfützner, M.; Karny, M.; Grigorenko, L.V.; Riisager, K. Radioactive Decays at Limits of Nuclear Stability. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 567–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, O.; Davinson, T.; Griffin, C.J.; Woods, P.J.; et al. The Advanced Implantation Detector Array (AIDA). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2023, 1050, 168166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.Y. The GAMMASPHERE. Nucl. Phys. A 1990, 520, 641c–655c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralithar, S.; Rani, K.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.P.; et al. Indian National Gamma Array at Inter University Accelerator Centre, New Delhi. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2010, 622, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.Y.; Clark, R.M.; et al. GRETINA: A gamma ray energy tracking array. Nucl. Phys. A 2004, 746, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis, S.; et al. The performance of the Gamma-Ray Energy Tracking In-beam Nuclear Array GRETINA. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2013, 709, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald, A.; Möller, O.; Petkov, P. Developing the Recoil Distance Doppler-Shift technique towards a versatile tool for lifetime measurements of excited nuclear states. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2012, 67, 786–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régis, J.-M.; Fraile, L.M.; Rudigier, M.; et al. γ–γ fast timing with high-performance LaBr3(Ce) scintillators. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2024, 141, 104152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonev, D.; et al. Transition probabilities in 31P and 31S: A test for isospin symmetry. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 821, 136603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androić, D.; Armstrong, D.S.; Asaturyan, A.; Averett, T.; Balewski, J.; Beaufait, J.; et al. (Q(weak) Collaboration). First determination of the weak charge of the proton. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 141803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al.; Adhikari; D; et al. (PREX Collaboration) Accurate determination of the neutron skin thickness of 208Pb through parity-violation in electron scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 172502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Adhikari; D; et al. (CREX Collaboration) Precision determination of the neutral weak form factor of 48Ca. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 042501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamyan, S.; Ahmed, Z.; et al.; Albataineh; H; et al. (PREX Collaboration) Measurement of the Neutron Radius of 208Pb through Parity Violation in Electron Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 112502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, E.; Paar, N. Implications of Parity-Violating Electron Scattering Experiments on 48Ca (CREX) and 208Pb (PREX-II) for Nuclear Energy Density Functionals. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 836, 137622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, Y.A.; Bishop, S.; Blaum, K.; Bosch, F.; Brandau, C.; Chen, L.X.; et al. Nuclear physics experiments with ion storage rings. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2013, 317, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, M.; Litvinov, Y.A. Heavy-ion storage rings and their use in precision experiments with highly charged ions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2020, 115, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, X.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Litvinov, Yu.A.; Xu, H.S.; et al. Bρ-defined isochronous mass spectrometry: An approach for high-precision mass measurements of short-lived nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, L051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, A.; Glasmacher, T. In-beam nuclear spectroscopy of bound states with fast exotic ion beams. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2008, 60, 161–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, K.; Winther, A. Electromagnetic Excitation: Theory of Coulomb Excitation with Heavy Ions; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Blaich, T.; et al. A large area detector for high-energy neutrons (LAND). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1992, 314, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.; et al. The Modular Neutron Array (MoNA). Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Exotic Nuclei and Atomic Masses (ENAM 2001); AIP Conf. Proc. 2003, 680, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, B.; et al. MoNA—The Modular Neutron Array at the NSCL. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2003, 505, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Kondo, Y. Large acceptance spectrometers for invariant mass spectroscopy of exotic nuclei and future developments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2016, 376, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, D.; Pearson, J.M.; Thibault, C. Recent Trends in the Determination of Nuclear Masses. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 1021–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, H.-J. Penning trap mass spectrometry of radionuclides. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 349–350, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, F.; Litvinov, Yu.A.; Stöhlker, T. Nuclear physics with unstable ions at storage rings. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2013, 73, 84–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.L.; Wang, M.; Litvinov, Yu.A.; et al. Precision isochronous mass measurements at the storage ring CSRe in Lanzhou. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2011, 654, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyad, Y.; Bazin, D.; Beceiro-Novo, S.; Cortesi, M.; Mittig, W. Physics and technology of time projection chambers as active targets. Eur. Phys. J. A 2018, 54, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, D.; Ahn, T.; Ayyad, Y.; et al. Low energy nuclear physics with active targets and time projection chambers. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2020, 114, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnlein, A.; Diefenthaler, M.; Sato, N.; Schram, M.; Ziegler, V.; Fanelli, C.; Hjorth-Jensen, M.; Horn, T.; Kuchera, M.P.; et al. Colloquium: Machine learning in nuclear physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 031003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, P.; Lee, J. Symmetry energy II: Isobaric analog states. Nucl. Phys. A 2014, 922, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Lim, Y. Constraining the symmetry parameters of the nuclear interaction. Astrophys. J. 2013, 771, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, R.; Drischler, C.; Tews, I.; Margueron, J. Constraints on the nuclear symmetry energy from asymmetric-matter calculations. Phys. Rev. C 2021, 103, 045803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Qian, Z.; Xing, R.Y.; Niu, J.R.; Sun, B.Y. Nuclear fourth-order symmetry energy and its effects on neutron star properties in the relativistic Hartree-Fock theory. Phys. Rev. C 2018, 97, 025801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Typel, S.; Brown, B.A. Neutron radii and the neutron equation of state in relativistic models. Phys. Rev. C 2001, 64, 027302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-W.; Ko, C.M.; Li, B.-A. Nuclear matter symmetry energy and the neutron skin thickness of heavy nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 72, 064309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, W.G.; Tsang, M.B. Decoding the density dependence of the nuclear symmetry energy. Phys. Lett. B 2022, 830, 137098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, M.D. Constraining the density dependence of the symmetry energy using the multiplicity and average pT ratios of charged pions. Phys. Rev. C 2017, 95, 014601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.B.; Friedman, W.A.; Gelbke, C.K.; Lynch, W.G.; Verde, G.; Xu, H.S. Isotopic scaling in nuclear reactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 5023–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demorest, P.B.; Pennucci, T.; Ransom, S.M.; Roberts, M.S.E.; Hessels, J.W.T. A two-solar-mass neutron star measured using Shapiro delay. Nature 2010, 467, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, J.; Freire, P.C.C.; Wex, N.; Tauris, T.M.; Lynch, R.S.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Kramer, M.; Bassa, C.; Dhillon, V.S.; Driebe, T.; et al. A massive pulsar in a compact relativistic binary. Science 2013, 340, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; et al.; Abbott; T.D; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) GW170817: Measurements of Neutron Star Radii and Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaev, T.A.; Berger, R. Polyatomic Candidates for Cooling of Molecules with Lasers from Simple Theoretical Concepts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 063006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, C.; Afach, S.; Ayres, N.J.; Baker, C.A.; Ban, G.; Bison, G.; Bodek, K.; Bondar, V.; Burghoff, M.; et al. Measurement of the permanent electric dipole moment of the neutron. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 081803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.M.; Dzuba, V.A.; Flambaum, V.V. Parity and time-reversal violation in atomic systems. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2015, 65, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinski, M.J.; Poon, A.W.P.; Rodejohann, W. Neutrinoless double-beta decay: Status and prospects. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2019, 69, 219–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Menéndez, J. Status and future of nuclear matrix elements for neutrinoless double-beta decay: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017, 80, 046301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flambaum, V.V.; DeMille, D.; Kozlov, M.G. Time-reversal symmetry violation in molecules induced by nuclear magnetic quadrupole moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spevak, V.; Auerbach, N.; Flambaum, V.V. Enhanced T-odd, P-odd electromagnetic moments in reflection asymmetric nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 1997, 56, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaczewski, J.; Engel, J. Nuclear time-reversal violation and the Schiff moment of 225Ra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 232502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P.A.; Nazarewicz, W. Intrinsic reflection asymmetry in atomic nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1996, 68, 349–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.H.; Dietrich, M.R.; Kalita, M.R.; Lemke, N.D.; Bailey, K.G.; Bishof, M.N.; Greene, J.P.; Holt, R.J.; Korsch, W.; Lu, Z.-T.; Mueller, P.; O’Connor, T.P.; Singh, J.T.; et al. First measurement of the atomic electric dipole moment of 225Ra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 233002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaczewski, J.; Engel, J.; Kortelainen, M.; Becker, P. Correlating Schiff moments in the light actinides with octupole moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 232501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Cadenas, J.J.; Martín-Albo, J.; Menéndez, J.; Mezzetto, M.; Monrabal, F.; Sorel, M. The search for neutrinoless double-beta decay. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 2023, 46, 619–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, J.; Valle, J.W.F. Neutrinoless double-β decay in SU(2)×U(1) theories. Phys. Rev. D 1982, 25, 2951–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Burlac; N; et al. (LEGEND Collaboration) Early results of the LEGEND-200 experiment. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2025, 1080, 170779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Gando; A; et al. (KamLAND-Zen Collaboration) KamLAND-Zen 800. Proc. Sci. 2022, ICHEP2022, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Abgrall; N; et al. (LEGEND Collaboration) LEGEND-1000 Preconceptual Design Report. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; Adhikari; G; et al. (nEXO Collaboration) nEXO: Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay Search Beyond 1028 Year Half-Life Sensitivity. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 2022, 49, 015104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolf, M.J.; Donnelly, T.W.; Dubach, J.; Pollock, S.J.; et al. Intermediate-energy semileptonic probes of the hadronic neutral current. Phys. Rep. 1994, 239, 1–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D.H.; McKeown, R.D. Parity-violating electron scattering and nucleon structure. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2001, 51, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Mantry, S.; Marciano, W.J.; Souder, P.A. Low-energy measurements of the weak mixing angle. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2013, 63, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Alves, B.X.R.; et al.; Baker; C.J; et al. (ALPHA Collaboration) Observation of the hyperfine spectrum of antihydrogen. Nature 2017, 548, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, M.; Alves, B.X.R.; et al.; Baker; C.J; et al. (ALPHA Collaboration) Characterization of the 1S–2S transition in antihydrogen. Nature 2018, 557, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, S.; Smorra, C.; Mooser, A.; et al. High-precision comparison of the antiproton-to-proton charge-to-mass ratio. Nature 2015, 524, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorra, C.; Sellner, S.; Borchert, M.J.; et al. A parts-per-billion measurement of the antiproton magnetic moment. Nature 2017, 550, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, V.; Ang, D.G.; et al.; DeMille; D; et al. (ACME Collaboration) Improved limit on the electric dipole moment of the electron. Nature 2018, 562, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairncross, W.B.; Gresh, D.N.; Grau, M.; et al. Precision measurement of the electron’s electric dipole moment using trapped molecular ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaev, T.A.; Hoekstra, S.; Berger, R. Laser-cooled RaF as a promising candidate to measure molecular parity violation. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 052521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symmetry Class | Representative Symmetries | Physical Origin and Description | Key Phenomena and Observables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental space–time and discrete symmetries | Time translations; spatial translations; rotations; discrete C, P, T (and combinations such as , ) | Exact invariances associated with space–time structure for an isolated system; discrete-symmetry conservation/violation depends on the interaction (with invariance ensured in local Lorentz-invariant QFT under standard assumptions) | Conservation of energy, momentum, and angular momentum; parity- and time-reversal-violation tests (e.g., EDMs, parity-violating observables) |

| Isospin and charge symmetries | SU(2) isospin; charge independence; charge symmetry () | Approximate internal symmetry of the strong interaction treating protons and neutrons as an isospin doublet; broken by Coulomb and charge-symmetry/charge-independence breaking terms | Isobaric analogue states (IAS); charge-exchange reactions; superallowed and allowed decay; IMME systematics; probes of isospin breaking (MED, isospin mixing) |

| Collective and group-theoretical symmetries | SU(3); | Emergent (often approximate) symmetries arising from correlated many-body motion | Rotational bands; vibrational spectra; collective modes (including giant resonances); quadrupole collectivity |

| Specialized symmetries | Pseudospin; F-spin; clustering symmetries; seniority/pairing | Approximate or emergent regularities in specific regions of the nuclear chart and/or within restricted model spaces | Near-degenerate single-particle doublets; mixed-symmetry states; seniority systematics and pairing gaps; isoscalar pairing |

| Chiral and QCD-inspired symmetries | Approximate chiral symmetry; chiral EFT expansion | Approximate chiral symmetry of QCD and its spontaneous breaking; basis for low-energy nuclear forces and currents | Long-range pion exchange; consistent nuclear forces and electroweak currents; uncertainty quantification in chiral EFT |

| Symmetry breaking and restoration | Mean-field breaking of rotational symmetry and particle-number global symmetry; explicit isospin breaking (Coulomb) | Efficient approximations that break symmetries at the mean-field level, restored by quantum correlations (projection, configuration mixing) | Deformation; pairing condensates; projection methods; configuration mixing; restoration of good quantum numbers; shape coexistence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).