1. Introduction

Food microbiology plays a crucial role in food safety, as many processed products are subject to microbial challenges that can compromise their quality, safety and shelf life [

1]. Vegetable creams, which have gained popularity as healthy and convenient foods [

2], present a favorable environment for microbial growth due to their nutritional composition, water activity and moderate pH [

3]. The prevalence of the

Bacillus cereus group in ready-to-eat (RTE) food products such as vegetable spreads available in the retail trade in Poland [

4] and South Korea [

5] was recently investigated. Therefore, ensuring the safety and microbiological stability of these products is essential for their market acceptance and to prevent public health risks as was clearly reflected in the World Health Organization (WHO) strategic planning meeting on food safety [

6].

Emerging strategies to control microbial growth in minimally processed foods include the use of bacteriocins and non-thermal processing technologies such as high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) [

7,

8,

9]. Bacteriocin AS-48, produced by

Enterococcus faecalis, is a class IIc cyclic enterocin which has bactericidal activity against a large number of Gram-positive bacteria of importance in food, such as

Listeria,

Bacillus and

Clostridium sp. [

10], making it an effective tool for microbial control in food [

11,

12]. On the other hand, HHP is a technology widely used in the food industry to inactivate pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms without significantly altering the organoleptic and nutritional characteristics of the products [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Although both bacteriocins and HHP have been shown to be effective independently, recent studies suggest that the combination of both technologies could offer a synergistic effect [

17], increasing the reduction of microbial load and reducing the emergence of resistant microorganisms and food-relevant microorganisms such as

Listeria monocytogenes [

18]. However, the effects of these combined strategies on the microbiota of specific foods, especially under conditions of temperature abuse, have not yet been widely explored.

The aim of the present study was to determine the impact of bacteriocin AS-48 and HHP treatment, both individually and in combination, on the microbial load and bacterial diversity in a commercial vegetable cream composed mainly of pumpkin and carrot. The application of culture-independent next-generation sequencing technologies may provide accurate and novel data on the effects of such treatments in food systems. In addition, how a temperature abuse event during storage affects the microbial stability and bacterial diversity of this product is analysed. The findings of this study provide relevant information on the efficacy of these preservation strategies in a model food, providing new perspectives for the development of more efficient and safer preservation systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Puree Samples

The refrigerated, ready-to eat carrot and pumpkin puree was purchased in a well-known supermarket in Jaén (Spain) just before processing. The puree was distributed in polyethylene-polyamide bags (preparing a total of 96 bags, 10 g each) to allow two replicates per sampling point and treatment (controls, bacteriocin, high-hydrostatic pressure, and bacteriocin + high-hydrostatic pressure). Samples were stored refrigerated at 4°C for up to 30 days. At day 2, half of the samples were incubated for 24 h at room temperature (simulating a temperature abuse event) and then refrigerated again.

2.2. Enterocin AS-48 Treatment

Enterocin AS-48 was prepared as described elsewhere [

19]. Samples were supplemented with enterocin AS-48 to a final concentration of 50 µg/g (or 7.5% vol/vol of an equivalent solution without bacteriocin for control and HHP-treated samples), mixed well and stored refrigerated at 4°C for up to 30 days.

2.3. High-Hydrostatic Pressure Treatments

High-hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatments were carried out by using a Stansted Fluid Power LTD HP equipment (SFP, Harlow, UK) suited with a 2.5 L vessel capable of operating in a pressure range of 0 to 700 megapacals (MPa). The system was suited with an electrical heating unit (SFP) operating in a temperature range from room temperature up to 90 °C. The following HHP treatment were applied for 8 min: 600 MPa at 55 °C. Come-up speed was 75 MPa/min. Decompression was almost immediate. Pressurization fluid was water with added 10% propylenglycol (Panreac, Madrid, Spain). Control and bacteriocin-treated samples (without HHP treatment) were run in parallel. Right after treatments, all samples were placed on an ice basket for 30 min and then stored at 4 °C for up to 30 days.

2.4. Microbiological Analysis

At specific times during incubation (days 0, 2, 3, 7, 15, 30), duplicate samples were drawn for each treatment and analyzed. The content of each bag was mixed individually with 20 mL sterile saline solution and homogenized in a Stomacher 400 (Seward, Worthing, UK) for 1 min. Homogenates were serially diluted in sterile saline solution and plated in triplicate on trypticase soya agar (TSA; Scharlab, Barcelona) for total aerobic mesophiles and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The mean viable cell count was expressed as log colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of sample.

2.5. DNA Extraction

For each sampling point and in duplicate, aliquots (5 mL) of each homogenate prepared as described in the previous section were mixed in sterile 50 mL test tubes and centrifuged at 600x g for 5 min to remove solids. An aliquot (1.5 mL) of the resulting supernatant was then transferred to an Eppendorf test tube and centrifuged at 13.500× g for 5 min to recover microbial cells. The pellets were resuspended in 0.5 mL of sterile saline each. Then, propidium monoazide (PMA, GenIUL, S.L, Barcelona, Spain) was added to block subsequent PCR amplification of DNA from dead cells [

20,

21]. DNA from PMA-treated cells was extracted by using a DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Madrid, Spain). The resulting DNA from the two replicates from each bag and from the same sampling point was pooled into a single sample. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA was determined by QuantiFluor® ONE dsDNA system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.6. DNA Sequencing and Analysis

The 16S rDNA V3-V4 regions were amplified following Illumina Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation protocol (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) targeting the 16S rDNA gene V3 and V4 region. Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences were added to the gene-specific sequences. The following 16S rDNA gene amplicon PCR primer sequences were used: forward primer: 50TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG; and reverse primer: 50GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC [

22]. Microbial genomic DNA (5 ng/ μL in 10 mM Tris pH 8.5) was used to initiate the protocol. After 16S rDNA gene amplification, the multiplexing step was performed using Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina). A total of 1 μL of the PCR product was run on a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 chip to verify the size (expected size ~550 bp). After size verification, the libraries were sequenced using a 2 x 300 pb paired-end run on a MiSeq Sequencer according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). Sequencing data were processed using nf-core/ampliseq version 2.13.0 [

23] of the nf-core collection of workflows [

24], utilising reproducible software environments from the Bioconda [

25] and Biocontainers [

26] projects. Data quality was evaluated with FastQC [

27] and summarized with MultiQC [

28]. Sequences were processed sample-wise (independent) with DADA2 [

29] to eliminate PhiX contamination, discard reads with >2 expected errors, correct errors, and remove PCR chimeras. Taxonomic classification was performed by DADA2 and the database ‘Silva 138.2 prokaryotic SSU’ [

30]. Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASV) sequences, abundance and DADA2 taxonomic assignments were loaded into QIIME2 [

31]. Subsequent analyses, conducted through QIIME2, included assessments of alpha and beta diversity as well as interactive visualizations of the microbial taxonomic composition. Final outputs were structured into R-compatible objects for further statistical analysis and custom data exploration.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of data corresponding to the culture-dependent microbiological analysis was determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. Data on bacterial diversity were compared by Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Different Treatments and Storage Time on Microbial Loads

Control samples subjected to temperature abuse (CAB) displayed viable counts of 2.54 and 2.05 log CFU/g during days 1 and 2 of storage, respectively (

Table 1). From day 3 of storage until the end of storage, a significant increase in viable counts occurred (p < 0.05), reaching values between 6.47 and 7.73 log CFU/g. In contrast, counts in control samples not subjected to abusive temperature (C) remained stable throughout storage, with values between 1.9 and 2.9 log CFU/g.

The bacteriocin treated samples (B) showed significantly lower viable counts (p < 0.05) at the end of storage (day 30) compared to control samples. However, bacteriocin treated samples only showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to control samples not subjected to abusive temperature (C) at days 3, 7 and 15 of storage. Interestingly, viable counts did not increase in the bacteriocin-treated samples after temperature abuse (BAB), and decreased below detectable levels at days 15 and 30.

Treatments with HHP (H) and bacteriocin in conjunction with HHP (BH) significantly reduced viable counts below the detection limit (<1.0 log CFU/g) for the whole storage period. These treatments also reduced viable counts below detection limits in the samples with temperature abuse (HAB, BHAB).

3.2. Bacterial Diversity

Most of the treated samples did not yield bacterial DNA of sufficient quantity/quality for amplicon sequencing, and therefore they were excluded from the bacterial diversity analysis. The number of reads assigned to Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) after taxonomic classification and filtering of unwanted taxa and alpha biodiversity indices (Shannon, Simpson and Chao) are shown in

Table 2. The numbers of reads ranged from 65,732 to 166,157. All sequenced samples show similar Shannon, Simpson and Chao-1 indices, except the untreated control samples not subjected to abusive temperature, whose values are lower from day 3 to the end of storage. In addition, it is worth mentioning the sample CAB3 with a value of the Chao-1 biodiversity index higher than the rest of the samples.

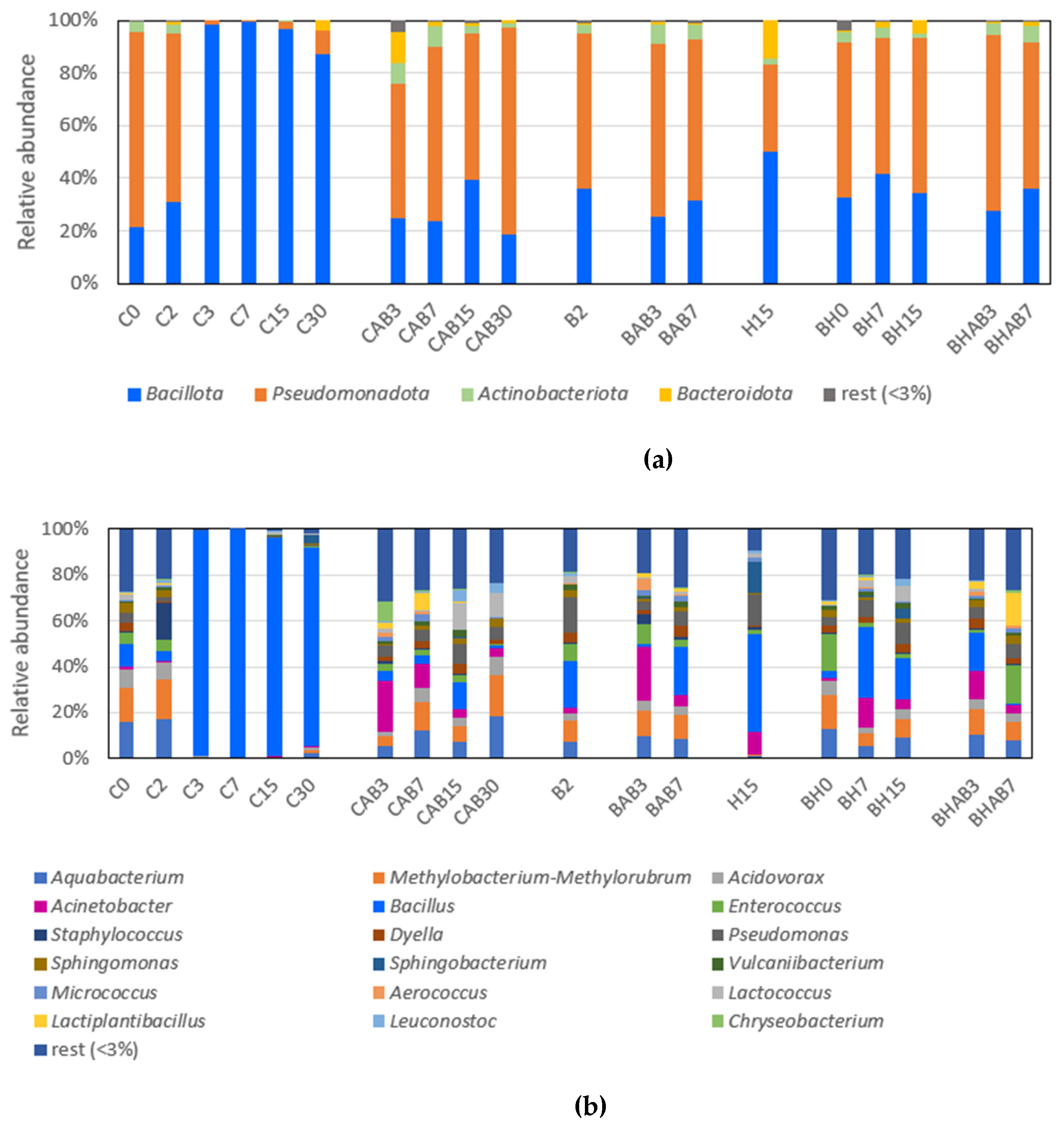

Taxonomic analysis indicated that

Pseudomonadota and

Bacillota were the main two phyla represented in the samples, followed by

Actinobacteriota and

Bacteoidota (Fig. 1A). During the first 2 days of refrigerated storage

Pseudomonadota was the most abundant phylum, followed by

Bacillota (

Figure 1A). The

Pseudomonadota group was mainly represented by members of the genera

Aquabacterium,

Methylobacterium-Methylorubrum and

Acidovorax (

Figure 1B). From day 3 until the end of the storage,

Bacillota (represented mainly by genus

Bacillus) became the predominant ASV, reaching relative abundances above 99%. By contrast, the control samples subjected to abusive temperature (CAB) showed high relative abundances of

Pseudomonadota along with an increase of

Actinobacteriota and

Bacteroidota.

Acinetobacter, along with

Aquabacterium,

Methylobacterium- Methylorubrum, Pseudomonas and

Chryseobacterium were the main representative genera detected in CAB samples.

The few samples treated with bacteriocin or bacteriocin plus high hydrostatic pressure that could be analysed showed taxonomic profiles at phylum level resembling the control samples at early storage, with Pseudomonadota being the most abundant phylum, followed by Bacillota. Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium-Methylorubrum, Aquabacterium, Acinetobacter, Enterococcus or Bacillus were among the most represented ASVs.

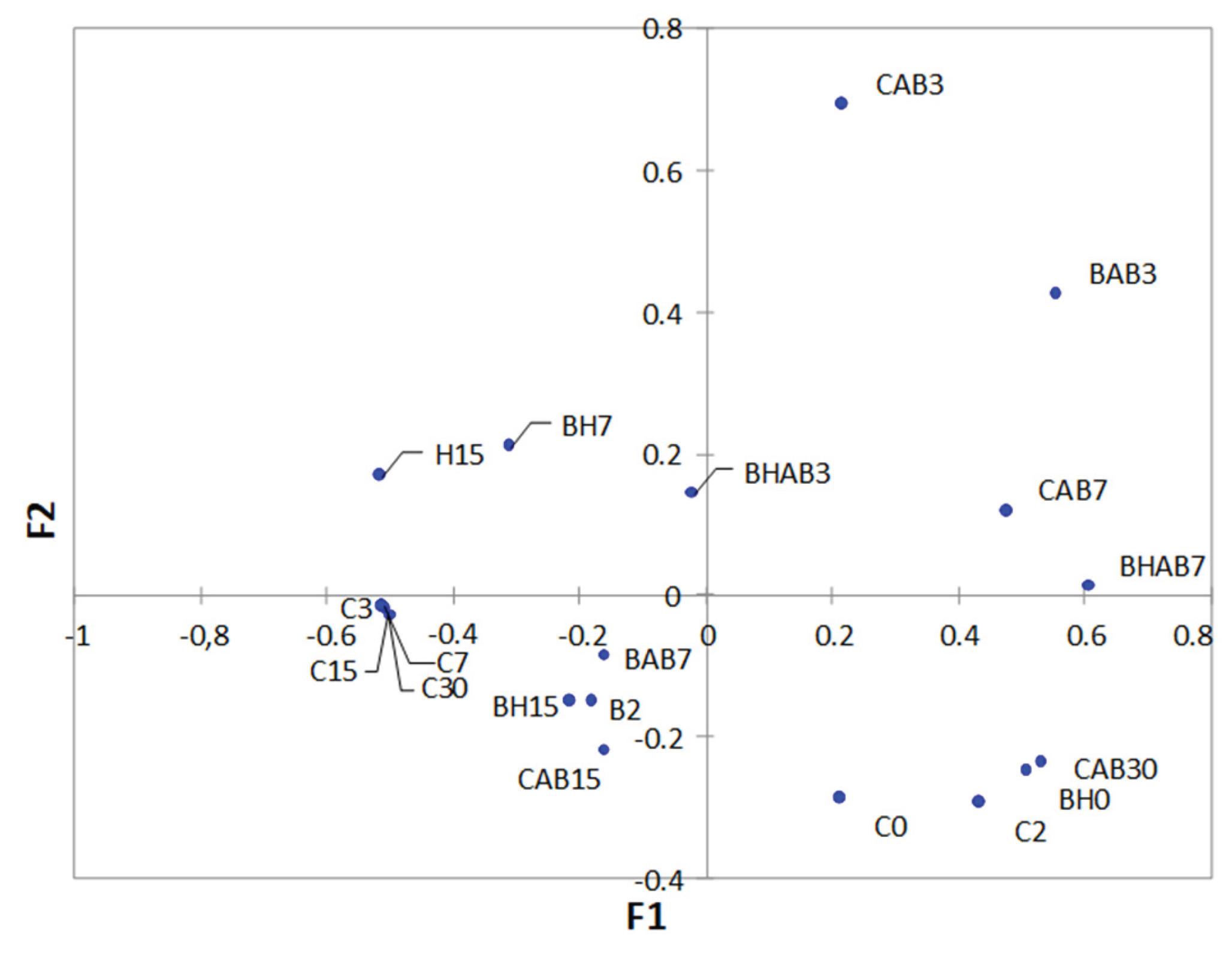

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) showed the differences in bacterial diversity at genus level between samples subjected to different treatments, storage times and temperature conditions (

Figure 2). A subgroup formed by the control samples taken from day 3 of storage and not subjected to abusive temperature (C3, C5, C7 and C30) can be observed, which are clearly distant from the rest of the samples. Furthermore, the storage times showed in some cases an influence on the bacterial composition regardless of the type of treatment to which they were subjected, as in the case of the subgroups formed by the samples taken at the beginning of storage (C0, C2 and BH0).

4. Discussion

The results obtained in the present study indicated that the concentrations of total aerobic mesophilic bacteria (TAM) in the vegetable puree remained low during storage. However, TAM rapidly increased with a 24-h temperature abuse period (emulating a cold chain break event), reaching up to 7.73 log CFU/g. The negative effect on the microbiological safety of food when experiencing a break in the cold chain has been demonstrated by previous studies. [

32] reported similar results in a study with courgette puree. An increase in temperature during storage (from 4 °C to room temperature) led to an increase in TAM counts from 3.9 to 7.8 log CFU/g. Similar results regarding high levels of contamination of vegetable foods by TAM were reported by [

33] although there are also studies in which such TAM values in vegetables were lower [

34].

Previous studies already reported the high efficacy of HHP treatments on vegetables such as pumpkin [

35]. Our study has shown that the use of HHP treatment at 55 ºC (alone or in combination with bacteriocin) resulted in the reduction of TAM counts in the puree below the limit of detection throughout storage, preventing bacterial proliferation during temperature abuse conditions. This would be expected considering the low initial microbial load of the puree samples and the enhanced antimicrobial activity obtained when HHP treatments are applied in combination with moderate heat [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Importantly, the combination of HHP treatments with heat has also been reported to improve inactivation of bacterial endospores [

40,

41,

42], which may represent one of the main risks in ready-to-eat slightly processed vegetable foods.

Although not as effective as HHP, bacteriocin treatment also resulted in the reduction of TAM, obtaining values below the detection limit by the end of storage. Interestingly, addition of AS-48 to the puree samples was an effective barrier against bacterial proliferation in the puree samples during temperature abuse conditions. The effectiveness of enterocin AS-48 has already been tested for the biopreservation of ready-to-eat vegetable foods against aerobic mesophilic endospore-forming bacteria by [

43] and in several types of vegetable foods [

11,

12,

44]. Similar to nisin [

41], enterocin AS-48 improves microbial inactivation and reduces the recovery of survivors when tested in combination with HHP treatments [

45]. However, a synergistic effect of AS-48 and HHP treatment could not be demonstrated in the carrot and pumpkin puree given the very low TAM concentrations in the puree.

The analysis of bacterial diversity showed that the control samples showed a high proportion of Pseudomonadota at the beginning of storage, with a progressive change in refrigeration conditions without temperature abuse towards a greater abundance of Bacillota, with Bacillus appearing as the clearly dominant genus. We could speculate that the observed changes could be due to reactivation of psychrotrophic Bacillus strains, displacing other members of the bacterial community that may be present in the samples. However, under conditions of temperature abuse, the microbiota was characterised by a persistence of Pseudomonadota and the increase in relative abundance of Acinetobacter (among others). In contrast, the rest of the treated samples (irrespective of treatment) showed mostly a microbiological profile dominated by the phylum Pseudomonadota with a reduced presence of Bacillota and less development of undesirable genera such as Bacillus throughout storage.

The results reported here highlight the efficacy of HHP and bacteriocins in the inactivation of potentially pathogenic microorganisms in food matrices, as is the case of the genus

Acinetobacter whose relative abundance in samples subjected to temperature abuse was reduced in treated samples compared to control samples. At the same time, the results obtained could be considered alarming, considering the risks of spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria [

46] and outbreaks caused by pathogens present in vegetables, such as the recent case reported by [

47], in which a virulent strain of the genus

Bacillus associated with vegetable food was isolated from a food outbreak and caused three deaths. Being a soil bacterium,

Bacillus can spread easily to vegetable foods. A previous study reported a prevalence of 20% for

Bacillus cereus in cooked chilled foods containing vegetables, and most of the

B. cereus strains isolated were psychrotrophic [

48]. Most worrying, members of

Bacillus can produce different toxins [

49,

50], among which cereulide may cause multi-organ failure [

51]. Regarding

Acinetobacter, previous studies have reported the presence of this bacterium from drinking water and foods [

52], including vegetables [

53].

Acinetobacter has been reported in carrot wash water [

54], and multidrug-resistant (MDR)

A. baumannii and

A. lwoffii have been detected in carrots originating from crops irrigated with water from the Jakara River in Nigeria, into which domestic, hospital, commercial, and industrial sewage is discharged [

55]. While most

Acinetobacter spp. are non-pathogenic environmental organisms, those species adapted to clinical environments are now causing serious health problems [

56]. Further studies are needed involving isolation of

Bacillus and

Acinetobacter strains from the purees and characterization of their potential for production of toxins and spread of antibiotic resistance genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and R.P.P.; formal analysis, A.G., J.R.L. and M.J.G.B.; investigation, R.L.L. and R.P.P.; resources, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., J.R.L.; writing—review and editing, A.G., J.R.L. and R.P.P.; supervision, R.L.L. and R.P.P.; project administration, A.G. and R.L.L.; funding acquisition, A.G. and R.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by University of Jaén, grant number AGR230” and “The APC was funded by University of Jaén”.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Jaén research group AGR230.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Łepecka, A.; Zielińska, D.; Szymański, P.; Buras, I.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Assessment of the Microbiological Quality of Ready-to-Eat Salads—Are There Any Reasons for Concern about Public Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekkenhorst, L. C.; Sim, M.; Bondonno, C. P.; Bondonno, N. P.; Ward, N. C.; Prince, R. L.; Devine, A.; Lewis, J. R.; Hodgson, J. M. Cardiovascular Health Benefits of Specific Vegetable Types: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Ibáñez, I.; Gil, M. I.; Allende, A. Ready-to-eat vegetables: Current problems and potential solutions to reduce microbial risk in the production chain. LWT 2016, 85, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Maćkiw, E.; Korsak, D.; Postupolski, J. Prevalence of Bacillus cereus in food products in Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2023, 31, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.; Yim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Oh, D.; Kim, S.; Seo, K. Quantitative Prevalence and Toxin Gene Profile of Bacillus cereus from Ready-to-Eat Vegetables in South Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015, 12, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy for Food Safety: Safer Food for Better Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42559.

- Aganovic, K.; Hertel, C.; Vogel, R. F.; Johne, R.; Schlüter, O.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Jäger, H.; Holzhauser, T.; Bergmair, J.; Roth, A.; Sevenich, R.; Bandick, N.; Kulling, S. E.; Knorr, D.; Engel, K.; Heinz, V. Aspects of high hydrostatic pressure food processing: Perspectives on technology and food safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3225–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. I.; Griffiths, M. W.; Mittal, G. S.; Deeth, H. C. Combining nonthermal technologies to control foodborne microorganisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 89, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gálvez, A.; Abriouel, H.; López, R. L.; Omar, N. B. Bacteriocin-based strategies for food biopreservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 120, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Suárez, C.; Cebrián, R.; Gasca-Capote, C.; Sorlózano-Puerto, A.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Maqueda, M.; Valdivia, E. Antimicrobial Activity of the Circular Bacteriocin AS-48 against Clinical Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.; Grande, M. J.; Abriouel, H.; Maqueda, M.; Omar, N. B.; Valdivia, E.; Martínez-Cañamero, M.; Gálvez, A. Application of the broad-spectrum bacteriocin enterocin AS-48 to inhibit Bacillus coagulans in canned fruit and vegetable foods. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, M. G.; Pulido, R.; Del Carmen López Aguayo, M.; Gálvez, A.; Lucas, R. The Cyclic Antibacterial Peptide Enterocin AS-48: Isolation, Mode of Action, and Possible Food Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22706–22727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M. F. Microbiology of pressure-treated foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolumar, T.; Orlien, V.; Sikes, A.; Aganovic, K.; Bak, K. H.; Guyon, C.; Stübler, A.; De Lamballerie, M.; Hertel, C.; Brüggemann, D. A. High-pressure processing of meat: Molecular impacts and industrial applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 20, 332–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, K. M.; Kelly, A. L.; Fitzgerald, G. F.; Hill, C.; Sleator, R. D. High-pressure processing – effects on microbial food safety and food quality. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, V.; Martínez-Monteagudo, S. I.; Gupta, R. Principles and Application of High Pressure–Based Technologies in the Food Industry. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Liao, X. High pressure processing plus technologies: Enhancing the inactivation of vegetative microorganisms. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2024, 110, 145–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komora, N.; Maciel, C.; Pinto, C. A.; Ferreira, V.; Brandão, T. R.; Saraiva, J. M.; Castro, S. M.; Teixeira, P. Non-thermal approach to Listeria monocytogenes inactivation in milk: The combined effect of high pressure, pediocin PA-1 and bacteriophage P100. Food Microbiol. 2019, 86, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriouel, H.; Valdivia, E.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Maqueda, M.; Gálvez, A. A simple method for semi-preparative-scale production and recovery of enterocin AS-48 derived from Enterococcus faecalis subsp. liquefaciens A-48-32. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 55, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocker, A.; Sossa-Fernandez, P.; Burr, M. D.; Camper, A. K. Use of Propidium Monoazide for Live/Dead Distinction in Microbial Ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5111–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizaquível, P.; Sánchez, G.; Aznar, R. Quantitative detection of viable foodborne E. coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella in fresh-cut vegetables combining propidium monoazide and real-time PCR. Food Control 2011, 25, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F. O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.; Blackwell, N.; Langarica-Fuentes, A.; Peltzer, A.; Nahnsen, S.; Kleindienst, S. Interpretations of Environmental Microbial Community Studies Are Biased by the Selected 16S rRNA (Gene) Amplicon Sequencing Pipeline. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 550420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P. A.; Peltzer, A.; Fillinger, S.; Patel, H.; Alneberg, J.; Wilm, A.; Garcia, M. U.; Di Tommaso, P.; Nahnsen, S. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüning, B.; Dale, R.; Sjödin, A.; Chapman, B. A.; Rowe, J.; Tomkins-Tinch, C. H.; Valieris, R.; Köster, J. Bioconda: sustainable and comprehensive software distribution for the life sciences. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Veiga Leprevost, F.; Grüning, B. A.; Aflitos, S. A.; Röst, H. L.; Uszkoreit, J.; Barsnes, H.; Vaudel, M.; Moreno, P.; Gatto, L.; Weber, J.; Bai, M.; Jimenez, R. C.; Sachsenberg, T.; Pfeuffer, J.; Alvarez, R. V.; Griss, J.; Nesvizhskii, A. I.; Perez-Riverol, Y. BioContainers: an open-source and community-driven framework for software standardization. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2580–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. In Babraham Bioinformatics; Babraham Institute: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B. J.; McMurdie, P. J.; Rosen, M. J.; Han, A. W.; Johnson, A. J. A.; Holmes, S. P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F. O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J. R.; Dillon, M. R.; Bokulich, N. A.; Abnet, C. C.; Al-Ghalith, G. A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E. J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J. E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C. J.; Brown, C. T.; Callahan, B. J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A. M.; Chase, J.; Caporaso, J. G. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinebretiere, M.; Berge, O.; Normand, P.; Morris, C.; Carlin, F.; Nguyen-The, C. Identification of Bacteria in Pasteurized Zucchini Purees Stored at Different Temperatures and Comparison with Those Found in Other Pasteurized Vegetable Purees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4520–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, B.; Szczech, M. Differences in microbiological quality of leafy green vegetables. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2022, 29, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kłapeć, T.; Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Cholewa, A.; Cholewa, G.; Dutkiewicz, J. Microbiological characterization of vegetables and their rhizosphere soil in Eastern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2016, 23, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, C.; Song, Y.; Chen, D.; Ni, Y.; Li, Q. The effect of high hydrostatic pressure on the microbiological quality and physical–chemical characteristics of Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) during refrigerated storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 21, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M. F.; Kilpatrick, D. J. The Combined Effect of High Hydrostatic Pressure and Mild Heat on Inactivation of Pathogens in Milk and Poultry. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J. R.; Grande, M. J.; Pérez-Pulido, R.; Galvez, A.; Lucas, R. Impact of High-Hydrostatic Pressure Treatments Applied Singly or in Combination with Moderate Heat on the Microbial Load, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Bacterial Diversity of Guacamole. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.I.; Griffiths, M.W.; Mittal, G.S.; Deeth, H.C. Combining nonthermal technologies to control foodborne microorganisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 89, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Liu, Q.; Denoya, G. I.; Yang, C.; Barba, F. J.; Yu, H.; Chen, X. High Hydrostatic Pressure-Based Combination Strategies for Microbial Inactivation of Food Products: The Cases of Emerging Combination Patterns. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 878904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadhi, C.; Simonin, H.; Prévost, H.; De Lamballerie, M.; Maaroufi, A.; Mejri, S. Inactivation of Bacillus sporothermodurans LTIS27 spores by high hydrostatic pressure and moderate heat studied by response surface methodology. LWT 2012, 50, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ju, X. Exploiting the combined effects of high pressure and moderate heat with nisin on inactivation of Clostridium botulinum spores. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 72, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tola, Y. B.; Ramaswamy, H. S. Combined effects of high pressure, moderate heat and pH on the inactivation kinetics of Bacillus licheniformis spores in carrot juice. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, M. J.; Abriouel, H.; Lucas-López, R.; Valdivia, E.; Ben-Omar, N.; Martínez-Cañamero, M.; Gálvez, A. Efficacy of enterocin AS-48 against bacilli in ready-to-eat vegetable soups and purees. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2339–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J. R.; Grande-Burgos, M. J.; De Filippis, F.; Pulido, R. P.; Ercolini, D.; Galvez, A.; Lucas, R. Determination of the effect of the bacteriocin enterocin AS-48 on the microbial loads and bacterial diversity of blueberries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Árbol, J. T.; Pulido, R. P.; Burgos, M. J. G.; Gálvez, A.; López, R. L. Inactivation of leuconostocs in cherimoya pulp by high hydrostatic pressure treatments applied singly or in combination with enterocin AS-48. LWT 2015, 65, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, C. S.; Tetens, J. L.; Schwaiger, K. Unraveling the Role of Vegetables in Spreading Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria: A Need for Quantitative Risk Assessment. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018, 15, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, J.; Gherman, I.; Day, A.; Cook, P. E. Bacillus cytotoxicus—A potentially virulent food-associated microbe. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 132, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choma, C.; Guinebretiere, M.; Carlin, F.; Schmitt, P.; Velge, P.; Granum, P.; Nguyen-The, C. Prevalence, characterization and growth of Bacillus cereus in commercial cooked chilled foods containing vegetables. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, R.; Jessberger, N.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Märtlbauer, E.; Granum, P. E. The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus cereus. Toxins 2021, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, J.; Ornelis, V. F. M.; Madder, A.; Rajkovic, A. Bacillus cereus food intoxication and toxicoinfection. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3719–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jia, K.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Q. Cereulide and Emetic Bacillus cereus: Characterizations, Impacts and Public Precautions. Foods 2023, 12, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Acinetobacter spp. in food and drinking water – A review. Food Microbiol. 2020, 95, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F. M.; Marina, M.; Pieckenstain, F. L. The communities of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) leaf endophytic bacteria, analyzed by 16S-ribosomal RNA gene pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 351, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausdorf, L.; Fröhling, A.; Schlüter, O.; Klocke, M. Analysis of the bacterial community within carrot wash water. Can. J. Microbiol. 2011, 57, 447–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiru, M.; Enabulele, O. I. Incidence of Acinetobacter in fresh carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus). Zenodo 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Nielsen, T. B.; Bonomo, R. A.; Pantapalangkoor, P.; Luna, B.; Spellberg, B. Clinical and Pathophysiological Overview of Acinetobacter Infections: a Century of Challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 409–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |