3.2.1. Forestland

3.2.1.1 Forestland Remaining Forestland

3.2.1.1.1 Category Description

There are two broad sub-divisions to forest land remaining forestland, namely, the Miombo woodland, and the plantations. Plantations are further sub-divided into two: Pines and Eucalyptus plantations. The distribution of Miombo woodland, Pine plantations and Eucalyptus plantations is 89%, 3%, and 8%, respectively [

2]. Miombo woodland in Malawi is defined as a tropical and subtropical dry forest ecosystem dominated by tree species from the Brachystegia, Julbernardia, and Isoberlinia genera. It is characterized by a mix of deciduous and semi-evergreen trees, with an understory of grasses and shrubs [

28]. Plantations included within forest land remaining forest land are commercial plantations (Pine and Eucalyptus).

3.2.1.1.2 Emissions and removals from forestland remaining forestland

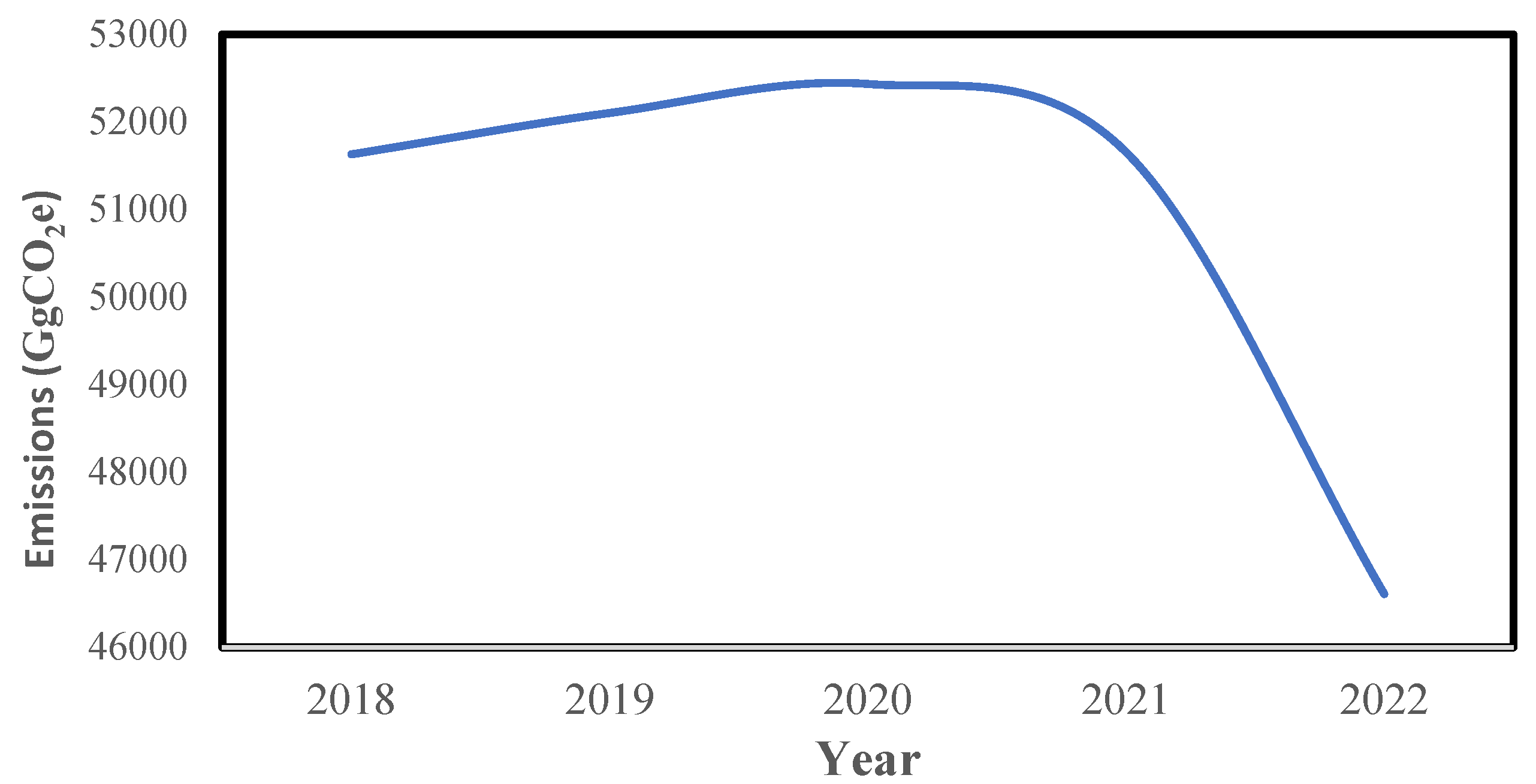

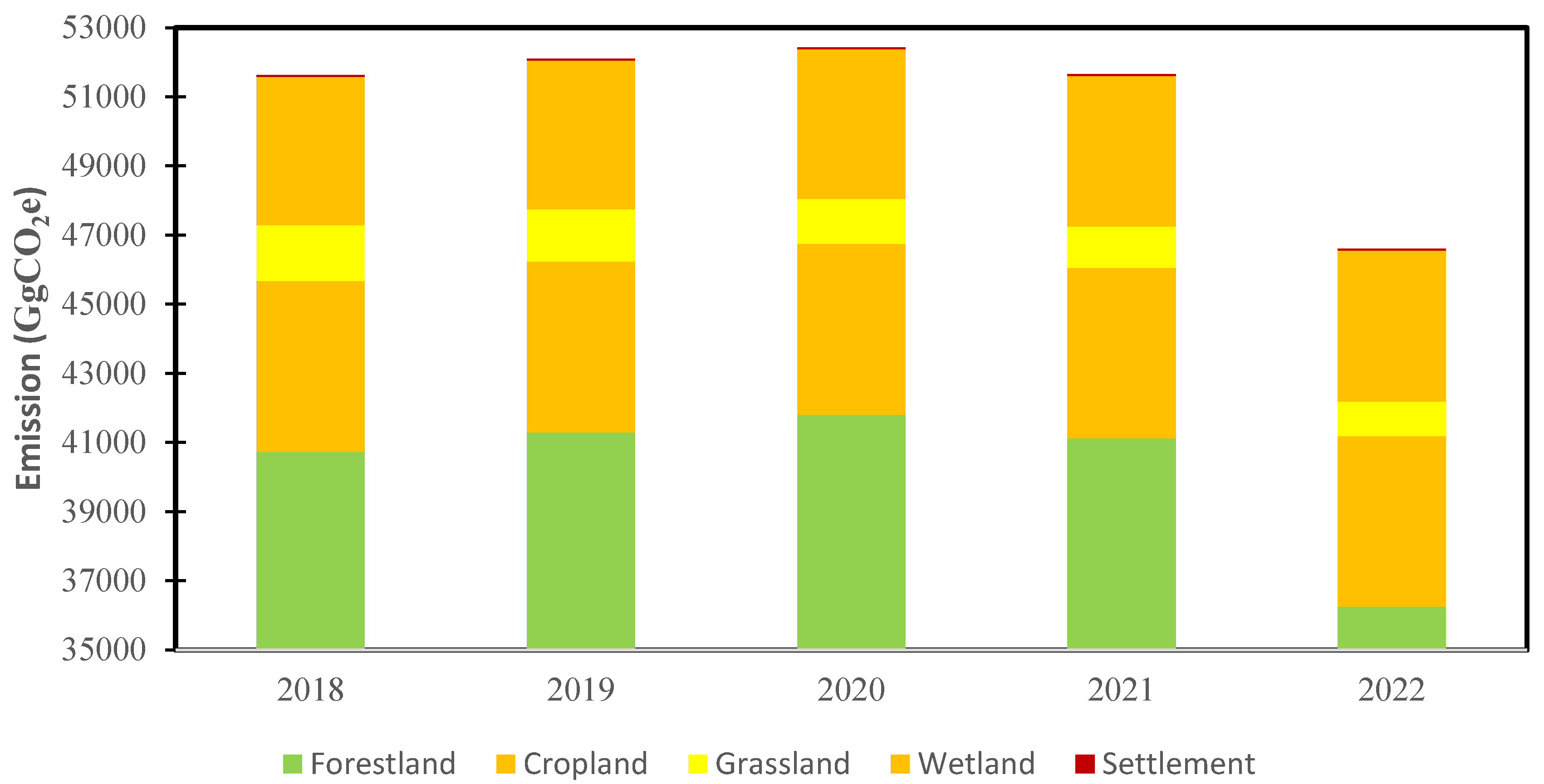

Summary of emissions and removals from forestland remaining forestland are depicted in

Table 5. The emissions data for ‘forestland’ remaining ‘forestland’ from 2018 to 2022 show a gradual decline from 33,830.53 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 33,494.63 GgCO₂e in 2022. This downward trend suggests a steady reduction in net emissions, which could be attributed to improved forest conservation efforts, enhanced carbon sequestration, or reduced deforestation and degradation [

29]. The consistent decrease, averaging around 84 GgCO₂e per year, indicates that forest management strategies, such as afforestation, reforestation, and reduced logging, may be having a positive impact [

10]. However, the decline is relatively small, implying that while progress is being made, additional efforts may be needed to accelerate carbon sequestration or further minimize emissions from forest degradation [

30]. Continuous monitoring and strengthening of sustainable forest management practices will be crucial to maintaining and enhancing this trend. Mitigation interventions implemented in areas hit-hard by the climate-induced catastrophes (cyclones Freddy, Idai and Chido) such as tree planting and conservation of regeneration would go a long way in enhancing carbon increase [

31].

3.2.1.2 Land converted to forestland

3.2.1.2.1 Category description

Land converted to forestland includes the sub-categories, (i) grassland converted to forest land, (ii) cropland converted to forest land, and (iii) wetlands converted to forest land [

2].

Grassland converted to forestland contains forest established on land that was previously non-forest. These conversions include (a) commercial plantations and environmental plantings, (b) forest that has regrown on land that was previously converted from a forest to grassland, and (c) regeneration from natural seed sources on land protected by State or Territory vegetation management policies.

Cropland converted to forest land contains forest that has regrown on land that was previously converted from forest land to the land use identified.

Wetlands converted to forestland comprises land on marsh have been detected to emerge with trees [

2].

3.2.1.2.2 Annual area (ha) and Annual net emissions for land converted to forestland

The annual area in hectares for the land converted to forestland category is shown in

Table 6. On the other hand, the annual net emissions for the land converted to forestland category are shown in

Table 7. The emissions data for land converted to forestland from 2018 to 2022 show a steady decline from 2,995.90 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 2,577.44 GgCO₂e in 2022, indicating a reduction of approximately 104 GgCO₂e per year. This downward trend suggests that newly established forests are increasingly acting as carbon sinks, sequestering more carbon over time as trees mature and accumulate biomass. The decline in emissions may also reflect improved afforestation and reforestation efforts, natural regeneration, or better land-use practices that enhance carbon absorption [

32]. However, the gradual decrease suggests that while progress is being made in converting land to forest, the rate of carbon sequestration is still limited, possibly due to factors such as species selection, soil conditions, or initial land degradation [

33]. Strengthening forest restoration initiatives and ensuring sustainable management of newly forested areas could further enhance carbon sequestration and contribute to long-term climate mitigation goals [

34].

3.2.1.2.3 Annual area burnt and net emissions for burning biomass in forestland

The annual area burnt and net emissions for burning biomass in forestland are presented in

Table 8. The emissions data for burning biomass in forestland from 2018 to 2022 show significant fluctuations, with a peak at 5,227.17 GgCO₂e in 2020. This is followed by a decline to 4,755.77 GgCO₂e in 2021, and a drastic drop to 96.27 GgCO₂e in 2022. The increase from 2018 to 2020 suggests intensified forest fires, slash-and-burn practices, or increased biomass burning due to deforestation or land clearing [

35]. However, the sharp reduction in 2022 indicates a major shift, potentially due to improved fire management strategies, stricter regulations, or favourable climatic conditions that reduced fire occurrences. Arguably, this could also typify the less anthropogenic activities subjected to forest (wood harvesting, forest fires for forest produce’s extraction) due to the lockdown that was imposed during the peak of the COVID 19 pandemic [

36]. The extreme variability highlights the sensitivity of forest emissions to human activities and environmental factors, emphasizing the need for sustainable forest fire management, early warning systems, and policies that mitigate biomass extraction and burning to maintain forest carbon stocks and reduce emissions [

37].

3.2.1.3 Harvested Wood Products

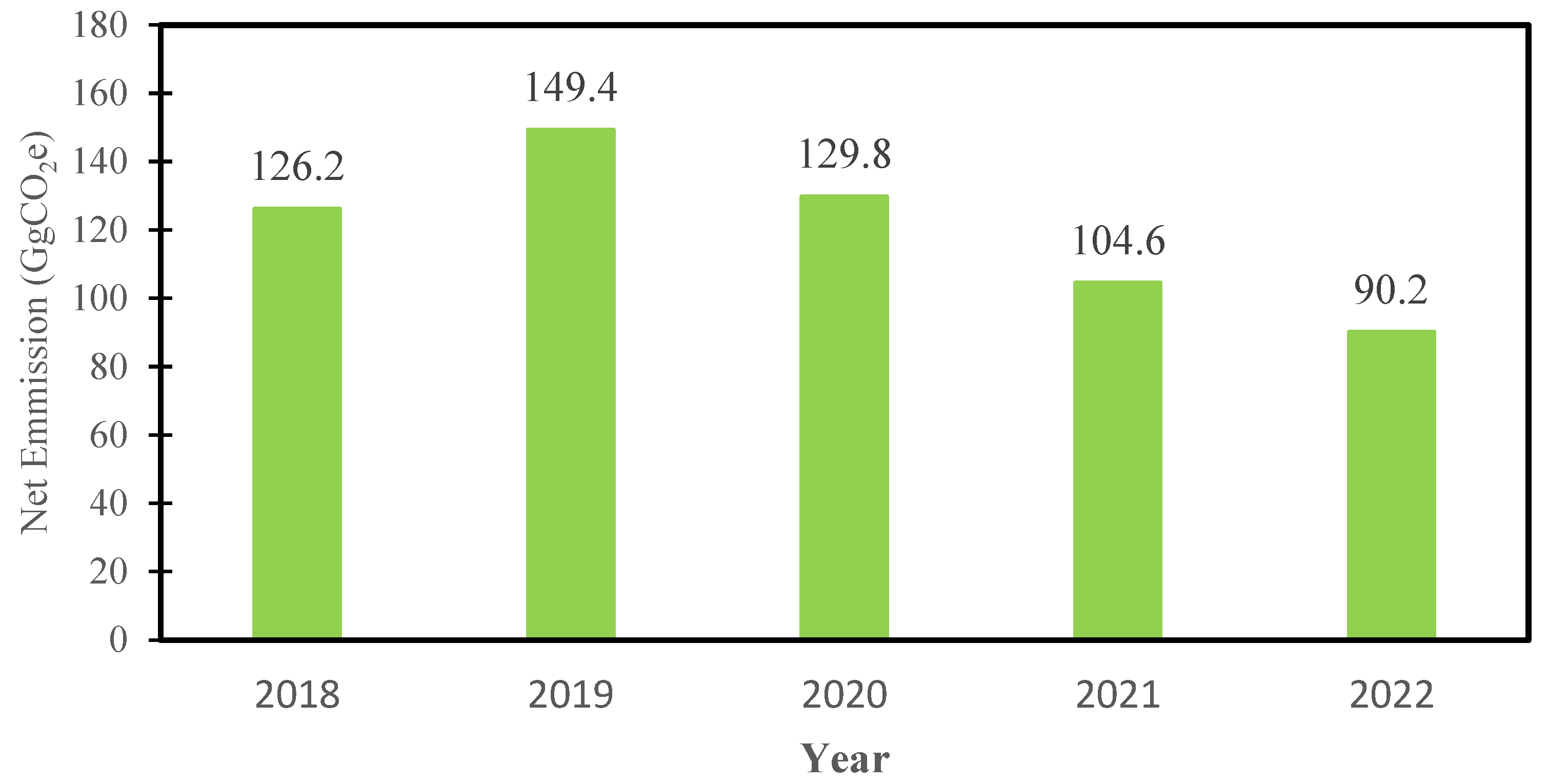

Malawi applies the stock-change approach for harvested wood products (HWP) in use. The net emissions from harvested wood products are presented in

Figure 5. The emissions data for harvested wood products in forestland from 2018 to 2022 exhibit fluctuations, with emissions rising from 126.2 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 149.4 GgCO₂e in 2019, then decreasing to 90.2 GgCO₂e by 2022. This trend suggests variability in the amount of wood harvested, with higher emissions in years of increased logging or timber extraction, followed by a reduction as harvesting activity decreased or more sustainable practices were implemented [

10]. The spike in 2019 could reflect an increase in timber demand or forest management practices that emphasized harvesting. Conversely, the subsequent decline may indicate a reduction in wood extraction, possibly due to changes in the market, improved forest management, or the adoption of policies promoting reforestation and sustainable timber harvesting [

2]. The overall reduction in emissions by 2022 highlights the potential for forest management strategies to limit carbon release from harvested wood products, underlining the importance of promoting sustainable forestry practices to balance economic needs with environmental goals [

38,

39].

3.2.2. Cropland

3.2.2.1 Cropland remaining cropland

3.2.2.1.1 Category description

The cropland remaining cropland sub-category includes continuous cropping lands and lands that are cropped in rotation with pastures. Croplands are of high land value with a high return on production and moderate to high soil nutrient status and are therefore not generally converted to forest land or grassland but remain as cropland [

10]. Anthropogenic emissions and removals on croplands occur because of changes in management practices from changes in crop type and from changes in land use. Permanent changes in management practices generate changes in the levels of soil carbon or woody biomass stocks over the longer term. Changes in carbon stock levels during the transition period to a new stock equilibrium are recorded under cropland [

2].

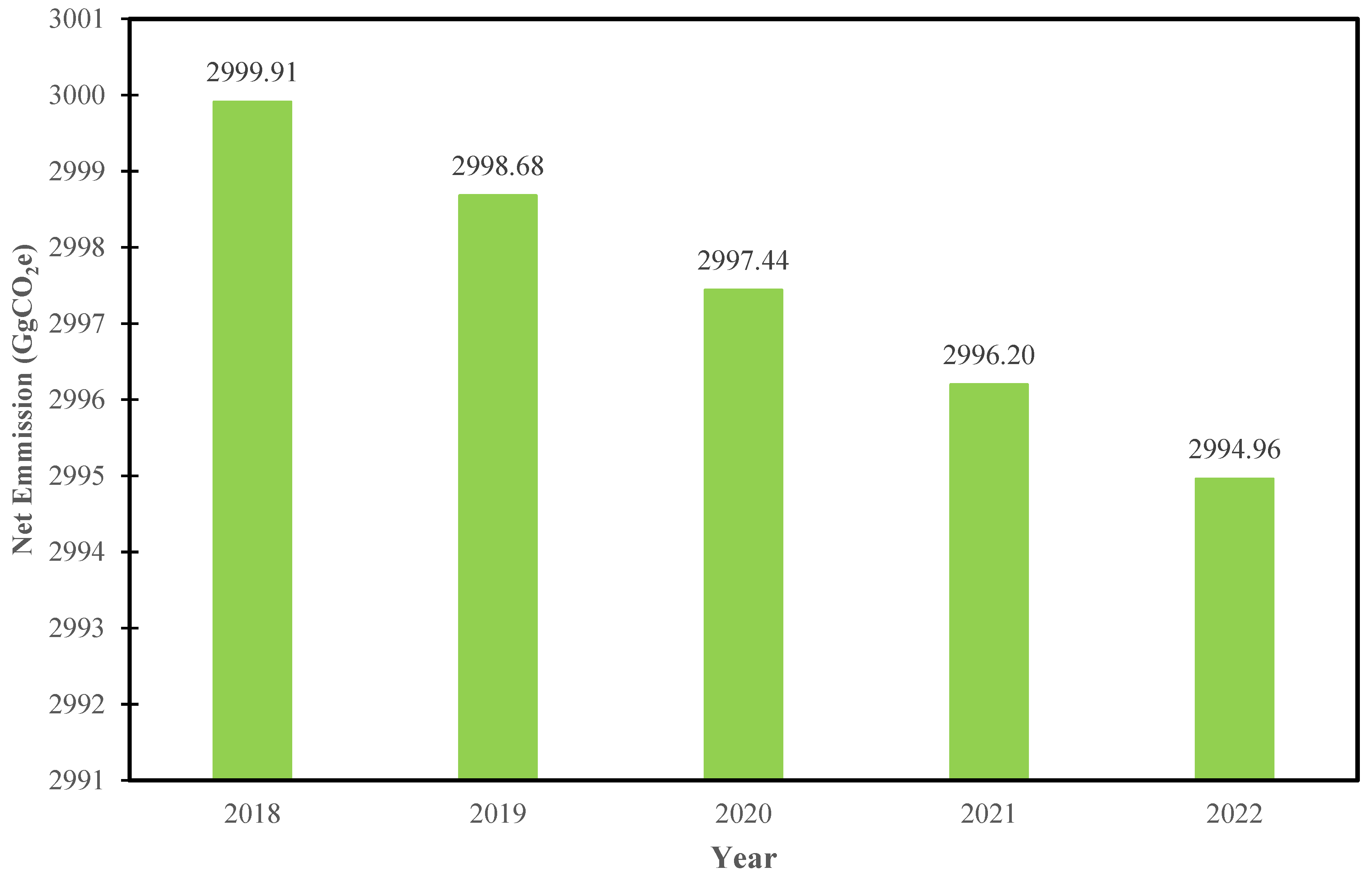

3.2.2.1.2 Net emissions (GgCO2e) from cropland remaining cropland

Summary of net emissions from cropland remaining cropland are given in

Figure 6. The emissions data for cropland remaining cropland from 2018 to 2022 show a very gradual decline from 2,999.91 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 2,994.96 GgCO₂e in 2022, indicating a minor annual reduction of approximately 1 GgCO₂e per year. This stability suggests that agricultural practices, soil carbon dynamics, and land-use management have remained largely unchanged over the years. The slight decrease in emissions could be attributed to marginal improvements in sustainable farming techniques, such as conservation agriculture, reduced tillage, or enhanced soil carbon sequestration [

40]. However, the minimal reduction implies that more significant interventions such as large-scale adoption of agroforestry, cover cropping, or improved fertilizer management, are needed to achieve substantial emission reductions [

10]. Continuous monitoring and investment in climate-smart agricultural practices could further enhance carbon sequestration and improve the sustainability of cropland management [

41].

3.2.2.2 Land converted to cropland

3.2.2.2.1 Category description

Within the land converted to cropland sub-category, Malawi reports emissions for forestland converted to cropland, and wetlands converted to cropland subcategories. The wetland converted to cropland subcategory includes the conversion of wetlands to cropping, and irrigated cropping [

2].

3.2.2.2.2 Annual area (ha) and Annual net emissions for land converted to cropland

The annual area in hectares for the land converted to cropland category is shown in

Table 9. On the other hand, the annual net emissions for the land converted to cropland category are shown in

Table 10. The emissions data for land converted to cropland from 2018 to 2022 show a steady decline from 181.63 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 148.61 GgCO₂e in 2022, reflecting an annual reduction of approximately 8 GgCO₂e. This declining trend suggests a decrease in land conversion to cropland, possibly due to reduced deforestation for agricultural expansion, improved land-use planning, or a shift towards more sustainable farming practices. The decrease may also indicate better soil management and conservation measures that help maintain or enhance soil carbon stocks [

10]. However, while this reduction is positive in terms of emission control, it could also be linked to factors such as land degradation, reduced agricultural expansion, or shifts in economic priorities affecting land use [

2]. Strengthening sustainable agricultural policies, promoting agroforestry, and enhancing soil carbon sequestration strategies could further reduce emissions while ensuring food security and productive land use [

40].

3.2.2.2.3 Annual area burnt and net emissions for burning biomass in cropland

The annual area burnt and net emissions for burning biomass in cropland are presented in

Table 11. The emissions data for burning biomass in cropland from 2018 to 2022 show a slight, but consistent increase from 1,768.80 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 1,778.67 GgCO₂e in 2022, with an average annual rise of approximately 2–3 GgCO₂e. This upswing trend suggests that agricultural biomass burning, such as the burning of crop residues, has remained a common practice. This could possibly be due to traditional land-clearing methods, limited access to alternative residue management techniques, or increasing agricultural activity [

10]. The steady increase in emissions highlights the need for improved sustainable practices, such as residue incorporation, mulching, or bioenergy production, to reduce carbon release and enhance soil fertility [

33]. Without interventions, continued biomass burning could contribute to long-term soil degradation and air pollution. Encouraging farmers to adopt climate-smart agriculture and promoting policies that regulate biomass burning could help curb emissions while maintaining agricultural productivity [

41].

3.2.3 Grassland

3.2.3.1 Grassland remaining grassland

3.2.3.1.1 Category description

The grassland remaining grassland category encompasses all grassland areas not classified under land converted to grassland. Areas that undergo rotational use between grassland and cropland are recorded under either forestland converted to cropland or cropland remaining cropland [

2]. Anthropogenic emissions and removals in grasslands result from shifts in management practices, particularly in pasture and grazing management, savanna fire management, and changes in sparse woody vegetation that do not qualify as forests. Grassland remaining grassland is categorized into three components corresponding to these practices. Long-term alterations in management can lead to changes in soil carbon levels or woody biomass stocks. As these changes occur, carbon may either be emitted or sequestered. However, these effects are temporary rather than permanent. Over time, the net emissions or removals from a modified management practice stabilise, reaching an equilibrium of approximately zero emissions, unless further changes disrupt the balance [

10].

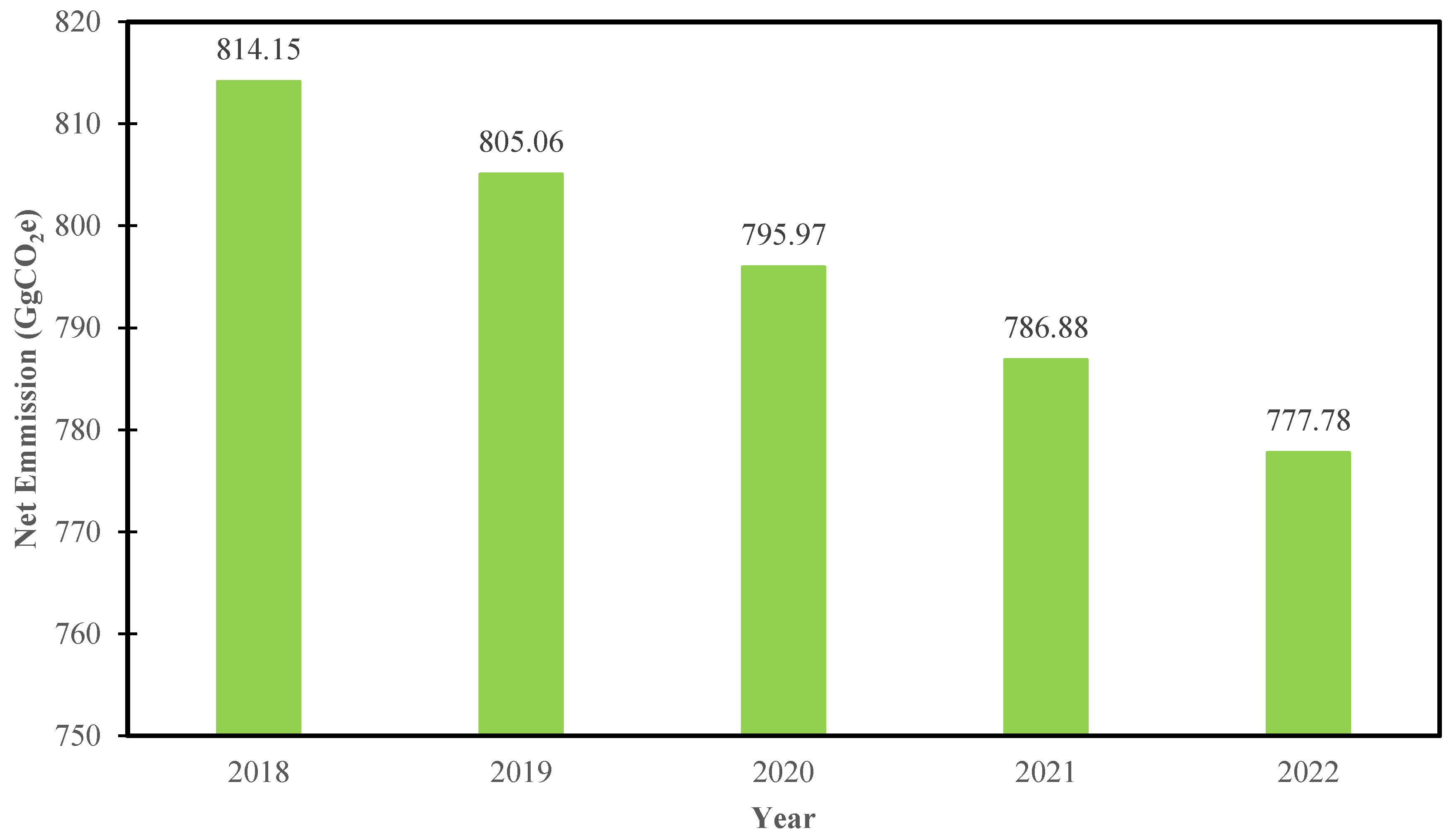

3.2.3.1.2. Net Emissions (GgCO2e) from Grassland Remaining Grassland

Summary of net emissions from grassland remaining grassland are provided in

Figure 7. The emissions data for grassland remaining grassland from 2018 to 2022 show a gradual decline from 814.15 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 777.78 GgCO₂e in 2022, with an average annual reduction of approximately 9 GgCO₂e. This decreasing trend suggests improved management of grasslands, potentially through better grazing practices, fire management, or natural regeneration that enhances carbon sequestration [

37]. The reduction in emissions could also indicate a shift towards more sustainable land-use strategies, such as rotational grazing or reduced biomass burning [

34]. However, the decline may also be influenced by changes in land cover, such as grassland degradation or conversion to other land uses, which could have long-term ecological consequences. To sustain and further reduce emissions, it is essential to strengthen grassland conservation efforts, promote ecosystem restoration, and implement policies that encourage carbon-friendly land management practices [

10].

3.2.3.2. Land Converted to Grassland

3.2.3.2.1. Category Description

In the land converted to grassland subcategory, Malawi reports emissions from forestland converted to grassland and wetlands converted to grassland. Net emissions resulting from conversions between croplands and grasslands are accounted for under croplands remaining croplands, as pasture and grazing rotations are commonly integrated into cropping systems [

2].

3.2.3.2.2. Annual Area (ha) and Net Emissions for Land Converted to Grassland

The annual area in hectares and net emissions for the land converted to grassland category are shown in

Table 12. The emissions data for land converted to grassland from 2018 to 2022 show a steady decline from 51.77 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 42.36 GgCO₂e in 2022, reflecting an annual reduction of approximately 2–3 GgCO₂e. This drop off trend suggests a decrease in land conversion to grassland, which may be due to reduced deforestation, shifts in land-use policies, or improved land management practices that enhance soil carbon sequestration [

10]. The declining emissions could also indicate a transition toward more stable ecosystems with lower carbon release from soil disturbance [

2]. However, this trend may also reflect a reduction in available land for grassland expansion, potentially due to competing land uses such as agriculture or urbanisation. To maximize the climate benefits of grasslands, further efforts in sustainable grazing, fire control, and soil restoration should be encouraged to enhance carbon storage and mitigate emissions [

37].

3.2.3.2.3. Annual Area Burnt and Net Emissions for Burning Biomass in Grassland

The annual area burnt and net emissions for burning biomass in grassland are presented in

Table 13. The emissions data for biomass burning in grassland from 2018 to 2022 show a significant and consistent decline from 747.48 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 182.75 GgCO₂e in 2022. This sharp reduction suggests a decrease in the frequency or intensity of grassland fires, likely due to improved fire management practices, reduced human-induced burning, or changes in climate conditions affecting fire occurrence. The decline may also be attributed to shifts in land-use practices, such as better grazing management or policies discouraging uncontrolled burning [

10]. While the reduction in emissions is a positive indicator for climate mitigation, it is important to assess whether it has any unintended ecological consequences, such as excessive fuel buildup that could lead to more intense wildfires in the future [

2]. Strengthening controlled burning strategies, promoting sustainable grazing, and enhancing natural firebreaks could help maintain the ecological balance while minimizing carbon emissions [

42].

3.2.4. Wetland

3.2.4.1. Wetland Remaining Wetland

3.2.4.1.1. Category Description

The estimates in this category are guided by the Environment Management Act No. 19 of 2017 and the 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines [

11]. In this category, the Malawi inventory includes estimates for biomass burning on tropical savannas that are categorised as wetlands [

2].

3.2.4.1.2. Net Carbon Dioxide Emissions (GgCO2e) from Wetland Remaining Wetland

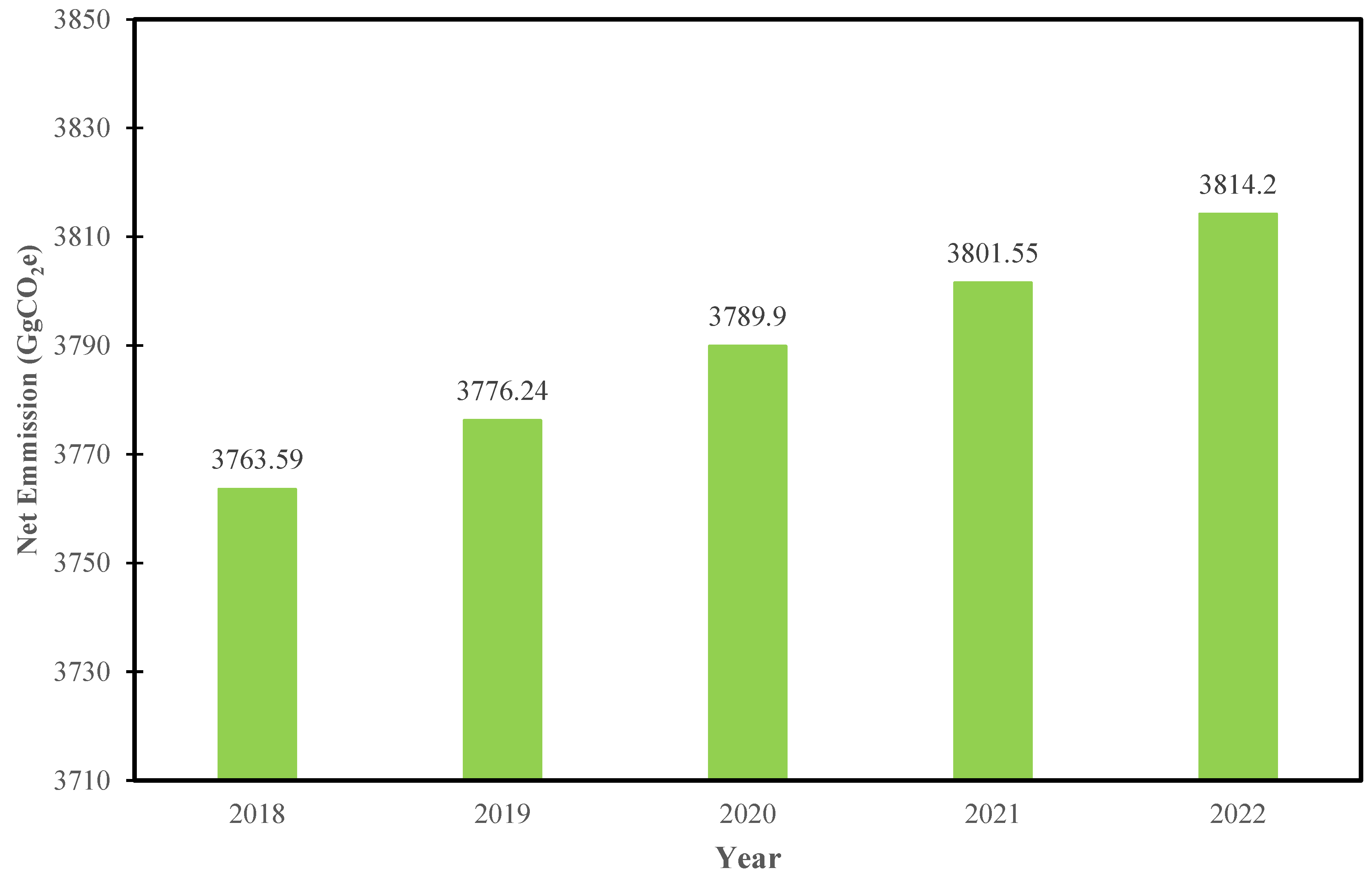

Summary of net emissions from wetland remaining wetland are given in

Figure 8. The emissions data for wetland remaining wetland from 2018 to 2022 show a gradual increase in emissions, rising from 3,763.59 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 3,814.20 GgCO₂e in 2022. This steady upward trend suggests that the wetlands are releasing more carbon over time, potentially due to factors such as increasing degradation, changes in water levels, or disturbances from land-use practices like drainage or agriculture. Wetlands are significant carbon sinks, but when disturbed, they can become net carbon emitters due to the release of stored carbon from organic soils [

2]. The consistent rise in emissions could reflect increased human activity in these areas, such as land conversion, or natural factors like climate change affecting water regimes [

10]. To mitigate this, effective wetland conservation strategies, including improved water management and restoration projects, are crucial to preserving their carbon sequestration capacity and reducing future emissions [

38].

3.2.4.2. Land Converted to Wetland

3.2.4.2.1. Category Description

This category includes the subcategory forest land converted to wetlands (flooded land). Forest conversion occurs when forests are cleared for the construction of reservoirs or other areas classified as flooded lands under the forest land converted to wetlands subcategory in the IPCC 2006 Guidelines [

11]. Emissions are reported for land clearing activities associated with flooding [

2].

3.2.4.2.2. Annual Area (ha) And Net Emissions for Land Converted to Wetland

The annual area in hectares and net emissions for the land converted to wetland category are shown in

Table 14. The emissions data for land converted to wetland from 2018 to 2022 show a steady increase, rising from 522.31 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 551.86 GgCO₂e in 2022. This consistent upward trend suggests that land conversions into wetlands, possibly driven by human activities such as drainage or reclamation for agricultural or developmental purposes, are leading to higher carbon emissions. Wetland conversions can release significant amounts of stored carbon from organic soils, as draining or disturbing these areas exposes previously sequestered carbon to oxidation, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions [

10]. The gradual increase in emissions highlights the need for better land-use planning and stronger regulations to prevent the degradation of wetlands. Additionally, promoting the restoration and preservation of wetlands can mitigate emissions, as healthy wetlands function as critical carbon sinks, contributing to climate change mitigation [

2].

3.2.5. Settlement

3.2.5.1. Settlement Remaining Settlement

3.2.5.1.1. Category Description

The settlements remaining settlements subcategory encompasses urban areas and infrastructure that have not undergone land use conversion. To prevent double counting, it excludes woody vegetation classified as forest land [

11]. This subcategory accounts only for net emissions from changes in sparse woody vegetation, such as those resulting from modifications in urban parks and gardens [

2].

3.2.5.1.2. Area and Net Emissions of Sparse Woody Vegetation, Settlements Remaining Settlements

The key input data and estimated net emissions for settlement remaining settlements are presented in

Table 15. The emissions data for settlement remaining settlement from 2018 to 2022 show minimal fluctuations, with emissions ranging from 19.47 GgCO₂e to 20.15 GgCO₂e over the five-year period. The slight variation in emissions indicates a stable level of emissions from settled areas, with relatively consistent land use and low changes in land cover. Settlements, being largely urbanized, tend to have stable emissions because the land-use patterns in these areas do not change significantly, and the main emission sources are typically from energy consumption, waste management, and transportation rather than land conversion [

10]. The small increase in 2022 could reflect urban expansion or increased emissions from infrastructure development or changes in waste management practices [

2]. This stability highlights the need for continued efforts in promoting sustainable urban planning, energy efficiency, and low-carbon technologies to keep emissions in settlement areas under control while supporting urban growth [

42].

3.2.5.2. Land Converted to Settlement

3.2.5.2.1. Category Description

The land converted to settlements category comprises areas where forestland has been cleared and transformed into settlements, reflecting land-use change driven by urbanization and infrastructure development [

11].

3.2.5.2.2. Annual Area (ha) for Land Converted to Settlement and Annual Net Emissions for Land Converted to Settlement

The annual area in hectares for the land converted to wetland category and annual net emissions for land converted to settlement are given in

Table 16. The emissions data for land converted to settlement from 2018 to 2022 show a consistent decline, decreasing from 39.55 GgCO₂e in 2018 to 38.27 GgCO₂e in 2022. This gradual decrease suggests a reduction in the amount of land being converted into settlements or potentially more sustainable urban development practices being implemented. Lower emissions could reflect urban planning initiatives that focus on reducing land use change, improving building designs, and using energy-efficient technologies, which mitigate emissions typically associated with land conversion, such as those from vegetation clearing or soil disturbance [

10]. The reduction might also indicate a shift towards higher-density developments rather than extensive sprawl [

29]. However, the decreasing trend in emissions is modest, so it is important to continue promoting sustainable land-use policies and smart growth strategies to minimize the environmental impact of urban expansion while accommodating population growth [

40].