1. Introduction

The imperative to address climate change has positioned environmental policy at the forefront of the global governance agenda. Following the Paris Agreement of 2015, nations have committed to limiting the rise in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with the aim of limiting warming to 1.5°C [

1]. Achieving these targets requires coordinated action across multiple policy dimensions, encompassing greenhouse gas mitigation, adaptation to climate impacts, economic transformation, and institutional capacity building [

2]. However, evaluating and comparing national climate policy performance presents substantial methodological challenges, as countries pursue diverse pathways shaped by their unique economic structures, resource endowments, and governance capabilities [

3].

The multidimensional nature of climate policy defies simple ranking approaches. A country may demonstrate exceptional performance in renewable energy deployment while lagging in emissions reduction or exhibit strong governance frameworks without commensurate adaptation capacity. This complexity necessitates analytical frameworks that integrate heterogeneous criteria, accommodate trade-offs among competing objectives, and provide transparent, theoretically grounded comparisons [

4]. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods offer promising approaches to address these challenges, yet their application to cross-national climate policy evaluation remains underdeveloped [

5].

This paper develops and applies a Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) framework for evaluating national climate policy performance across 187 countries. Drawing on established decision-theoretic foundations [

6,

7] and leveraging publicly available data from the Global Carbon Project, ND-GAIN Index, and World Bank, the proposed Climate Policy Performance Index (CPPI) integrates four fundamental dimensions: mitigation effectiveness, adaptation capacity, economic readiness, and governance quality. The framework advances beyond existing indices by providing explicit utility functions, axiomatic foundations, and comprehensive sensitivity analysis.

Multi-Attribute Utility Theory emerged from the foundational work of von Neumann and Morgenstern [

8] on expected utility and was systematically developed by Keeney and Raiffa [

6] in their seminal treatise on decisions with multiple objectives. The theory provides a rigorous framework for constructing preference functions over alternatives characterised by multiple attributes, enabling decision-makers to quantify trade-offs and aggregate diverse criteria into coherent evaluations. Central to MAUT are axioms of preferential independence and utility independence, which permit decomposition of complex multiattribute utility functions into tractable additive or multiplicative forms [

9].

Dyer [

10] provides a comprehensive review of MAUT methodology, emphasising the distinction between value functions that measure the strength of preference under certainty and utility functions that capture risk attitudes under uncertainty. The additive utility model,

U(x) = Σwᵢuᵢ(xᵢ), remains the most widely applied form, requiring mutual preferential independence among attributes—a condition that preferences over any subset of attributes are independent of fixed levels of remaining attributes [

6]. When this condition holds, single-attribute utility functions can be assessed independently and aggregated through weighted summation, substantially simplifying practical application.

Applications of MAUT span diverse domains, including infrastructure planning [

11], healthcare resource allocation [

12], and environmental management [

13]. Ananda and Herath [

14] applied MAUT to evaluate public risk preferences in forest land-use choices, demonstrating the methodology's capacity to integrate stakeholder values with technical performance metrics. In the energy sector, MCDA approaches have been extensively employed for technology assessment [

15], renewable energy planning [

16], and sustainability evaluation [

17]. However, the systematic application of MAUT to cross-national comparisons of climate policy remains notably absent from the literature.

Several indices currently assess national climate performance, each with distinct methodological approaches and coverage. The Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI), developed by Germanwatch, NewClimate Institute, and Climate Action Network, evaluates 63 countries and the European Union across four categories: greenhouse gas emissions (40%), renewable energy (20%), energy use (20%), and climate policy (20%) [

18]. Published annually since 2005, the CCPI combines quantitative indicators from the International Energy Agency and UNFCCC with qualitative expert assessments of national climate policies. Notably, no country has achieved the highest performance category, with Denmark consistently ranking fourth (the highest occupied position) in recent editions [

19].

The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Country Index takes a complementary approach, measuring climate vulnerability and adaptation readiness across 185 countries [

20]. Vulnerability assessment encompasses six life-supporting sectors—food, water, health, ecosystem services, human habitat, and infrastructure—while readiness captures the economic, governance, and social dimensions that enable investment in adaptation [

21]. The ND-GAIN methodology employs 45 indicators aggregated through simple averaging, providing comprehensive coverage but lacking explicit preference modelling or trade-off analysis.

Additional frameworks include the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) from Yale and Columbia Universities, which tracks environmental health and ecosystem vitality across 180 countries [

22], and the Low Carbon Economy Index from PwC, which focuses specifically on the decarbonization progress of G20 nations [

23]. While these indices provide valuable comparative information, they share common methodological limitations: reliance on ad hoc weighting schemes without theoretical justification, absence of explicit utility or preference modelling, limited sensitivity analysis, and restricted country coverage (particularly the CCPI's focus on major emitters only).

Multi-criteria decision analysis has gained substantial traction in sustainability assessment, though applications predominantly focus on project or technology evaluation rather than cross-national comparison. Diaz-Balteiro et al. [

24] review MCDA applications in renewable energy, identifying the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) as the most frequently employed method, used in nearly 50% of studies that incorporate social criteria. Løken [

25] surveys decision analysis approaches in energy planning, noting the growing use of outranking methods (ELECTRE, PROMETHEE) alongside value-based techniques for accommodating incommensurable criteria.

Recent applications demonstrate MCDA's utility for sustainability assessment at various scales. Wulf et al. [

26] developed the HELDA software tool, implementing multiple MCDA methods for energy technology sustainability assessment, emphasising the need for transparent criteria weighting and sensitivity analysis. Jóhannesson et al. [

27] combined systems dynamics modelling with MCDA and stakeholder engagement for Icelandic energy transition planning, illustrating the methodology's potential for integrating diverse sustainability themes. Shmelev and Rodríguez-Labajos [

28] applied MCDA to evaluate sustainable development indicators across European cities, though without the explicit utility-theoretic foundations that characterise MAUT.

In the context of climate policy evaluation, Konidari and Mavrakis [

29] proposed a multi-criteria framework for assessing climate change mitigation policy instruments, applying the AHP to weight environmental effectiveness, economic efficiency, and political feasibility. Roumasset and colleagues [

30] developed a social welfare approach to climate adaptation investment prioritisation, incorporating economic efficiency alongside equity considerations. However, these applications typically address policy instrument selection within individual countries rather than systematic cross-national performance comparison.

Despite substantial progress in both MAUT methodology and climate performance assessment, a significant gap exists at their intersection. Existing climate indices lack the theoretical rigour of utility-based frameworks and rely on ad hoc weighting schemes without axiomatic justification or explicit preference modelling. Conversely, MAUT applications in sustainability remain confined to project-level analysis, with no systematic application to cross-national climate policy evaluation. Furthermore, the integration of adaptation capacity and governance quality with mitigation performance remains underdeveloped in existing frameworks.

This paper addresses these gaps through three principal contributions. First, we develop a comprehensive MAUT framework explicitly designed for climate policy evaluation, providing axiomatic foundations, specified utility functions, and transparent aggregation procedures. Second, we construct the Climate Policy Performance Index (CPPI) covering 187 countries—substantially expanding coverage beyond the 63-country CCPI—by leveraging open-source data from established repositories. Third, we conduct extensive sensitivity analysis across alternative weighting schemes, utility function specifications, and aggregation methods, demonstrating the robustness and limitations of the proposed framework.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study developed and applied a Multi-Attribute Utility Theory framework to evaluate the performance of national climate policies across 187 countries. The resulting Climate Policy Performance Index (CPPI) integrates four dimensions—mitigation, adaptation, economic capacity, and governance—providing a theoretically grounded alternative to existing ad hoc indices. Several key findings emerge from the analysis.

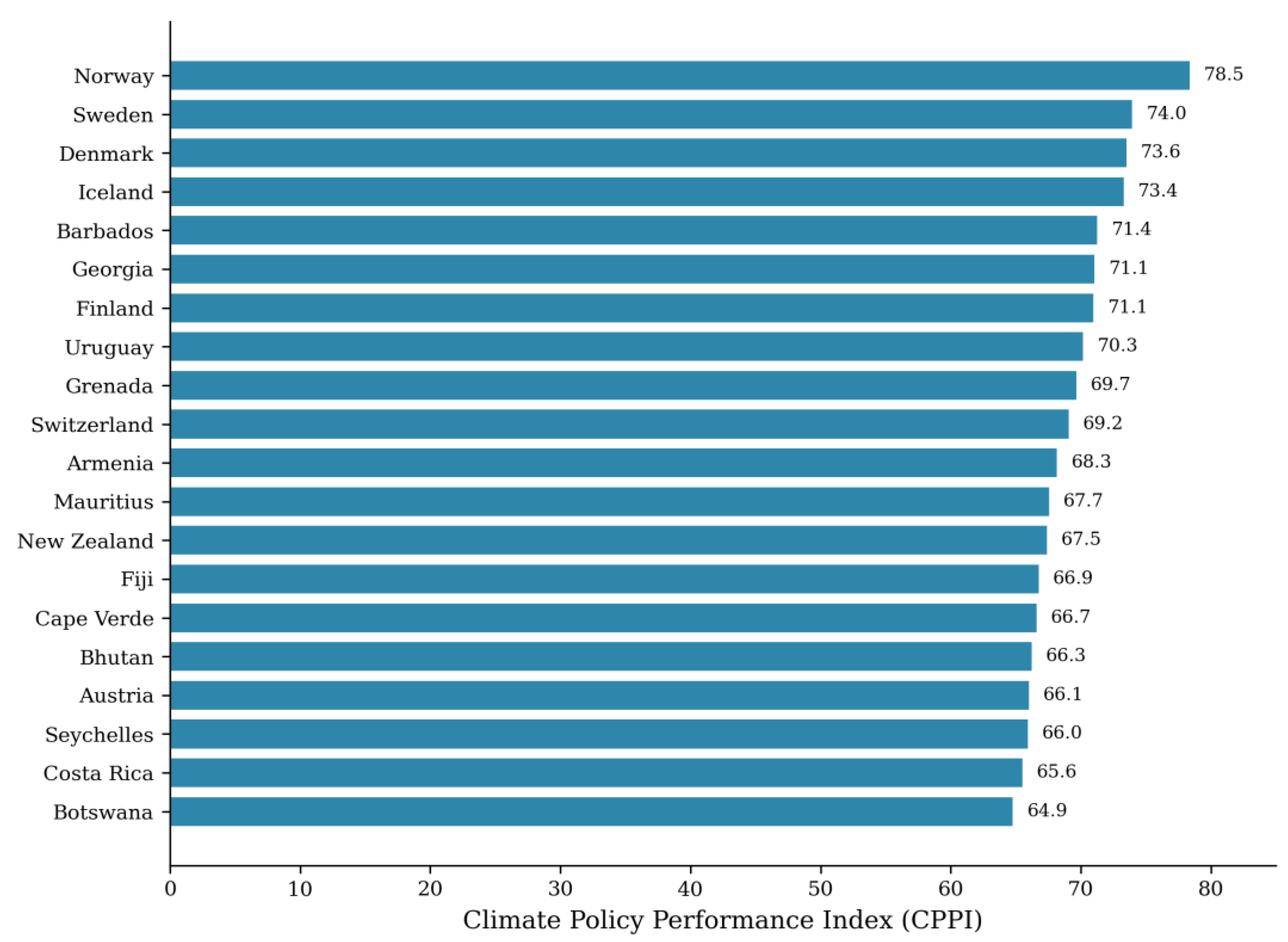

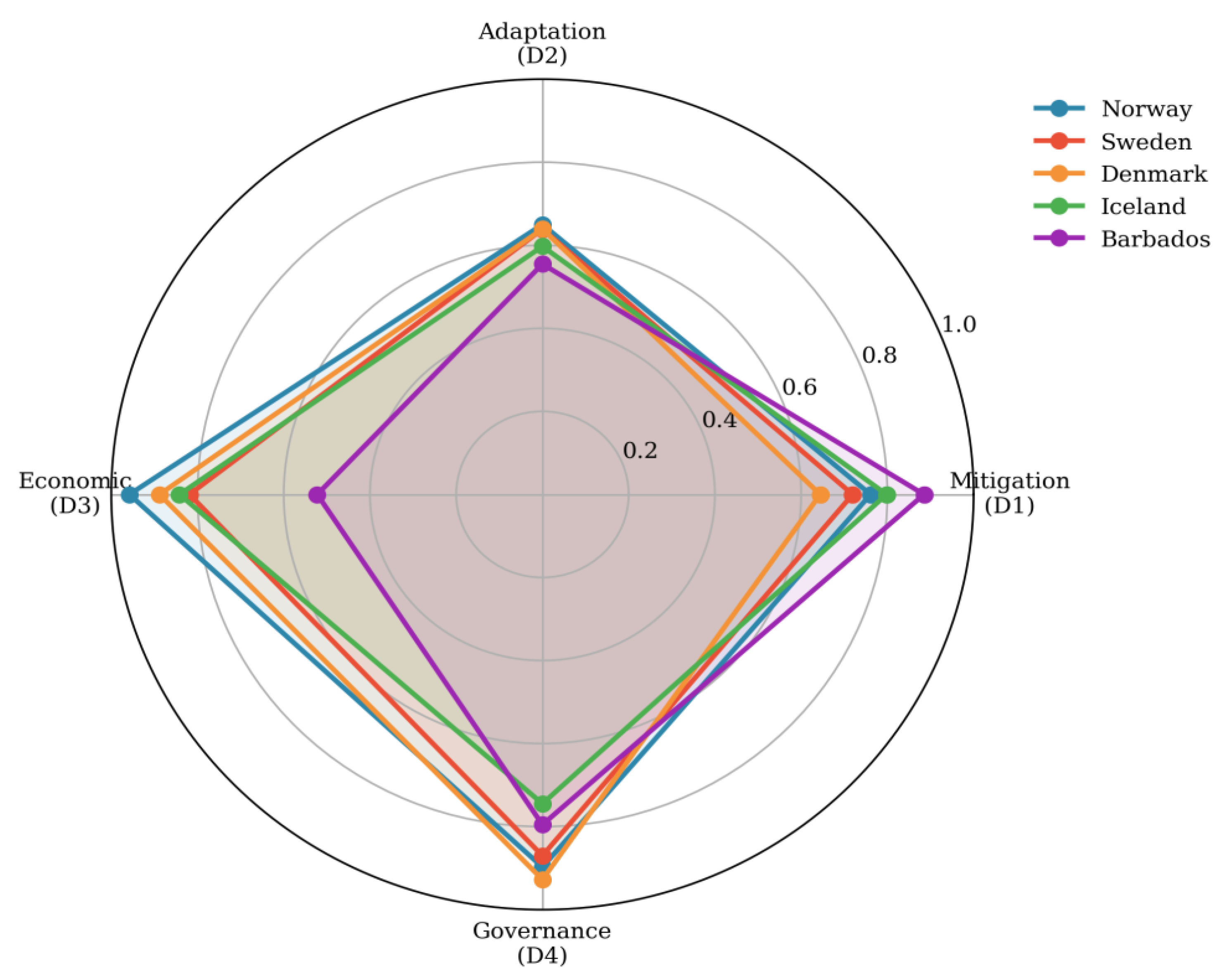

First, Norway emerges as the global leader (CPPI = 78.46), followed by Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. These Nordic countries achieve high scores by balancing excellence across four dimensions: moderate-to-low emissions, strong deployment of renewable energy, robust adaptation capacity, and high-quality governance institutions. This finding contrasts with indices that focus solely on emissions, in which low-income countries with minimal industrial activity often rank highest despite limited institutional capacity for sustained climate action.

Second, the analysis reveals distinct performance archetypes among high-ranking countries. Norway and Denmark exemplify the 'balanced performer' archetype with consistently high scores across dimensions. Uruguay represents the 'mitigation leader' pathway, achieving exceptional D1 scores (0.945) through low emissions and high renewable penetration, compensating for moderate governance capacity. Singapore illustrates an alternative 'governance-economy' pathway, where world-class institutions (D4 = 0.926) and economic readiness (D3 = 0.955) offset weaker mitigation performance (D1 = 0.393). These diverse pathways underscore that climate policy success admits multiple configurations, challenging one-size-fits-all policy prescriptions.

Third, the bottom of the ranking reveals two distinct failure modes. Fossil-fuel-dependent economies (Qatar, Kuwait, Trinidad and Tobago) exhibit near-zero mitigation scores despite strong economic indicators, whereas countries facing governance deficits (Turkmenistan, Venezuela) perform poorly across multiple dimensions. This bifurcation suggests that remedial strategies must be tailored to specific national circumstances—emissions reduction for petrostates versus institutional strengthening for governance-challenged countries.

4.2. Comparison with Existing Climate Indices

The CPPI both converges with and diverges from established indices in instructive ways. Compared with the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI), our framework identifies the Nordic countries as leaders but yields notably different rankings for several country groups. The CCPI's exclusive focus on major emitters (63 countries) excludes many small island states and low-income countries that perform well under CPPI's broader coverage. Moreover, the CCPI deliberately leaves its top three positions vacant to signal that no country meets the Paris Agreement targets—a normative stance that our utility-theoretic approach does not impose.

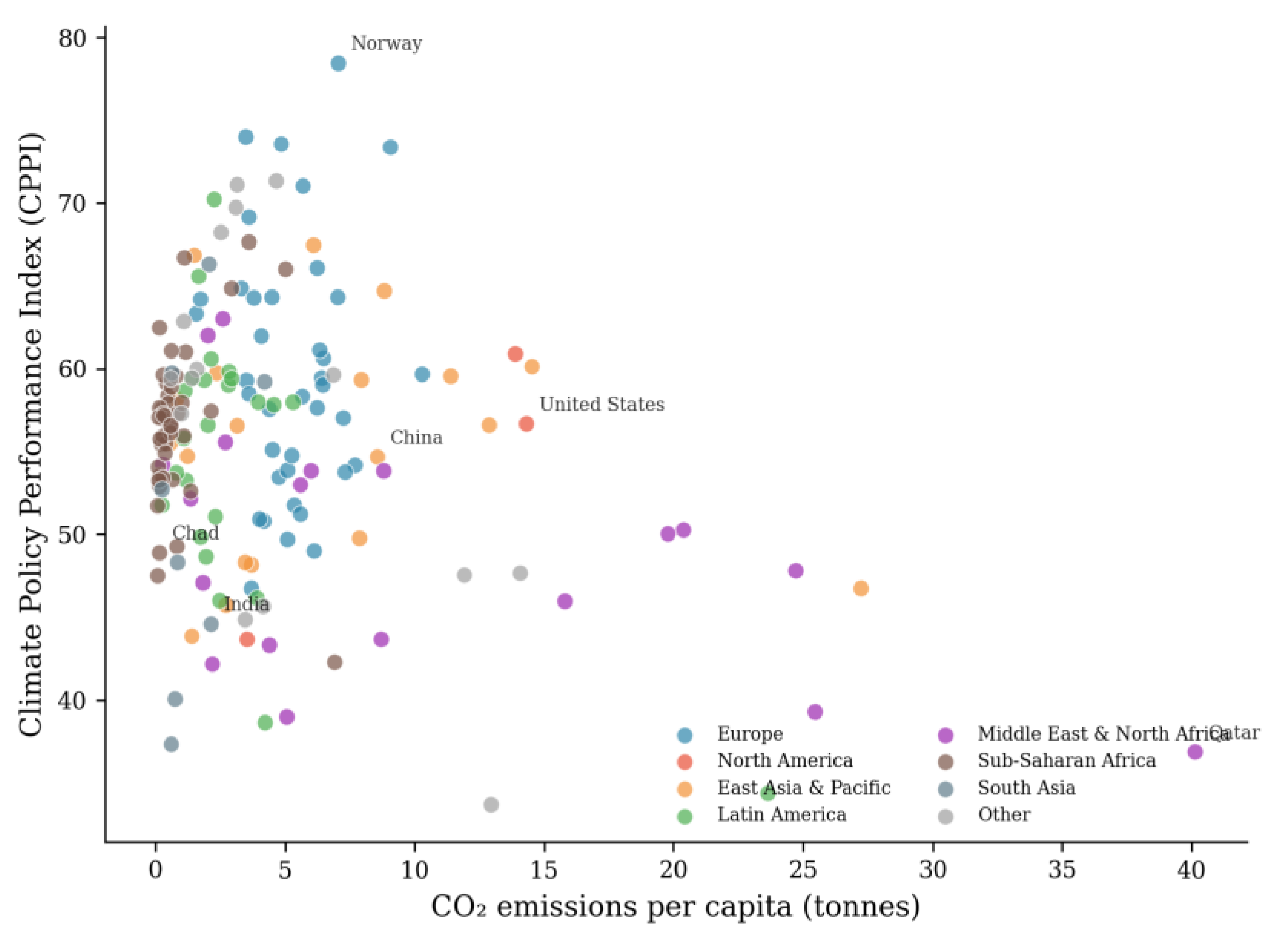

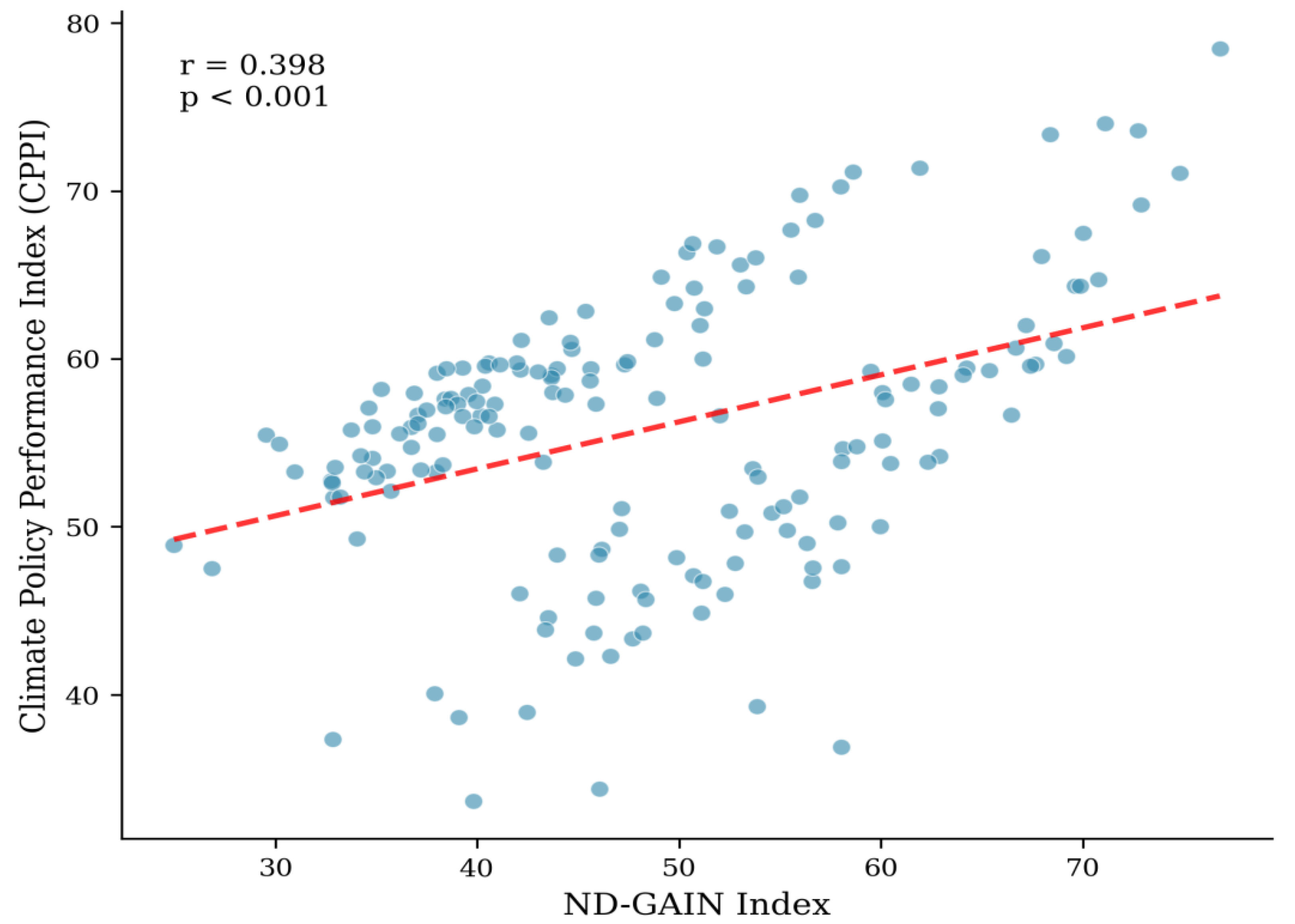

The moderate correlation between CPPI and ND-GAIN (r = 0.398) indicates these indices capture related but distinct constructs. ND-GAIN emphasises vulnerability and adaptation readiness without explicit mitigation assessment, while CPPI integrates both dimensions. Countries with high ND-GAIN scores but moderate CPPI rankings (e.g., Singapore, Australia) typically exhibit strong adaptation capacity, but this capacity is undermined by high emissions. Conversely, low-emission developing countries (Rwanda, Bhutan) achieve higher CPPI rankings than their ND-GAIN positions would suggest, reflecting the credit CPPI assigns to mitigation performance.

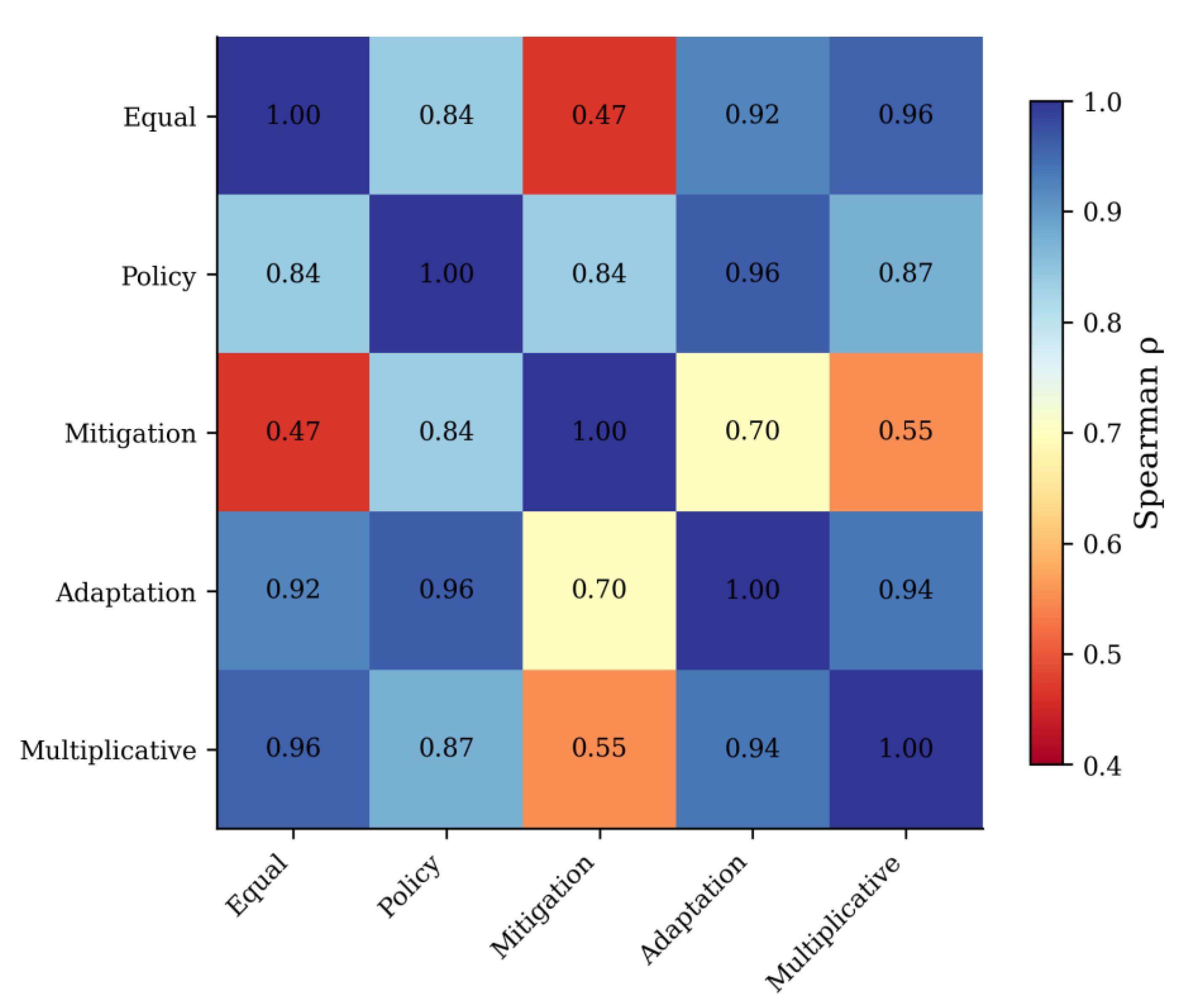

A critical methodological distinction concerns the transparency of weighting. Existing indices typically employ fixed, expert-determined weights without systematic sensitivity analysis. The CPPI framework explicitly models weight uncertainty through four alternative schemes (equal, policy-aligned, mitigation-focused, adaptation-focused) and multiplicative aggregation. The high rank correlations among most schemes (ρ > 0.83) provide reassurance that rankings are reasonably robust, while the lower correlation with mitigation-focused weights (ρ = 0.47 vs. equal) reveals the substantive impact of normative choices regarding dimension priority.

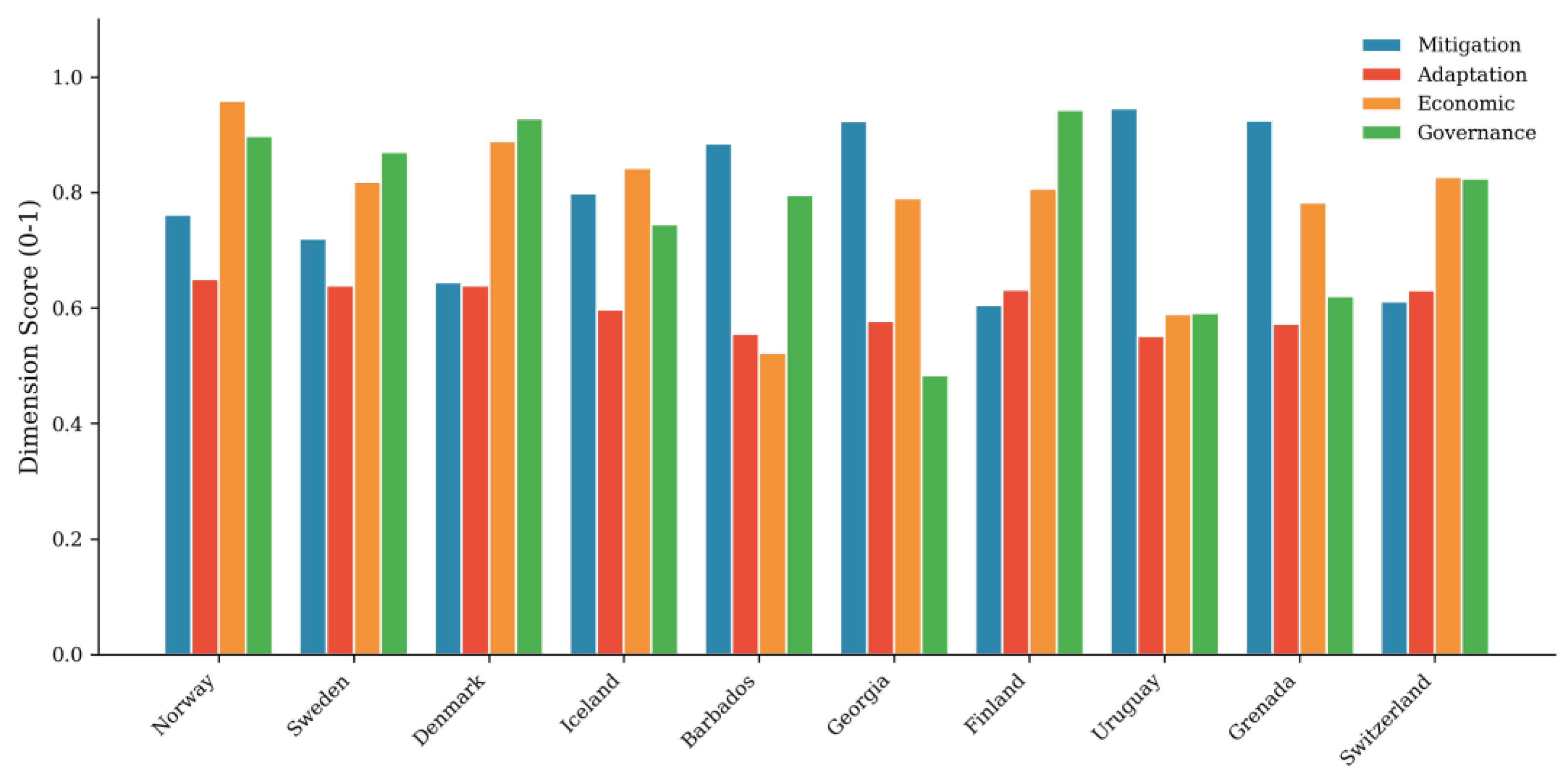

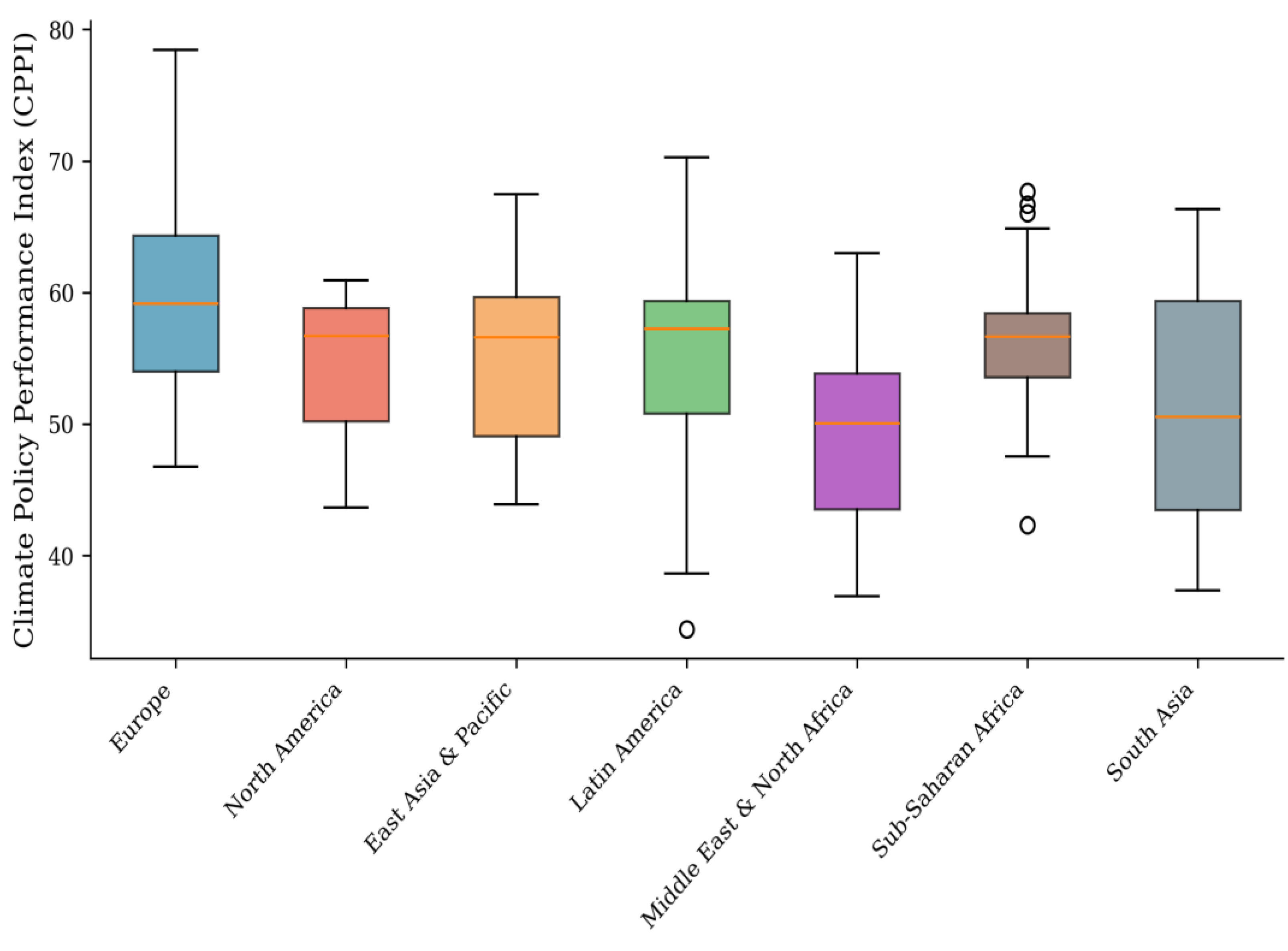

4.3. Regional Patterns and the Development-Climate Nexus

The regional analysis reveals a nuanced relationship between development status and climate performance. Europe leads with the highest mean CPPI (59.92), driven primarily by strong governance and adaptation capacity rather than emissions performance alone. Sub-Saharan Africa achieves the third-highest regional mean (56.56) through exceptional mitigation scores (D1 = 0.971) that compensate for weaker institutional dimensions—a pattern reflecting low per capita emissions rather than deliberate climate policy success. This finding cautions against interpreting high mitigation scores in low-income contexts as policy achievements; they often reflect development deficits rather than climate leadership.

The Middle East and North Africa region ranks lowest (CPPI = 49.12), primarily due to weak mitigation performance in fossil fuel-exporting economies. This regional pattern aligns with broader research on the relationship between resource dependence and climate policy ambition. The 'resource curse' literature suggests that hydrocarbon wealth creates structural barriers to decarbonization through vested interests, Dutch disease effects, and reduced incentives for economic diversification [

37]. Our findings provide empirical support for this hypothesis at the national level.

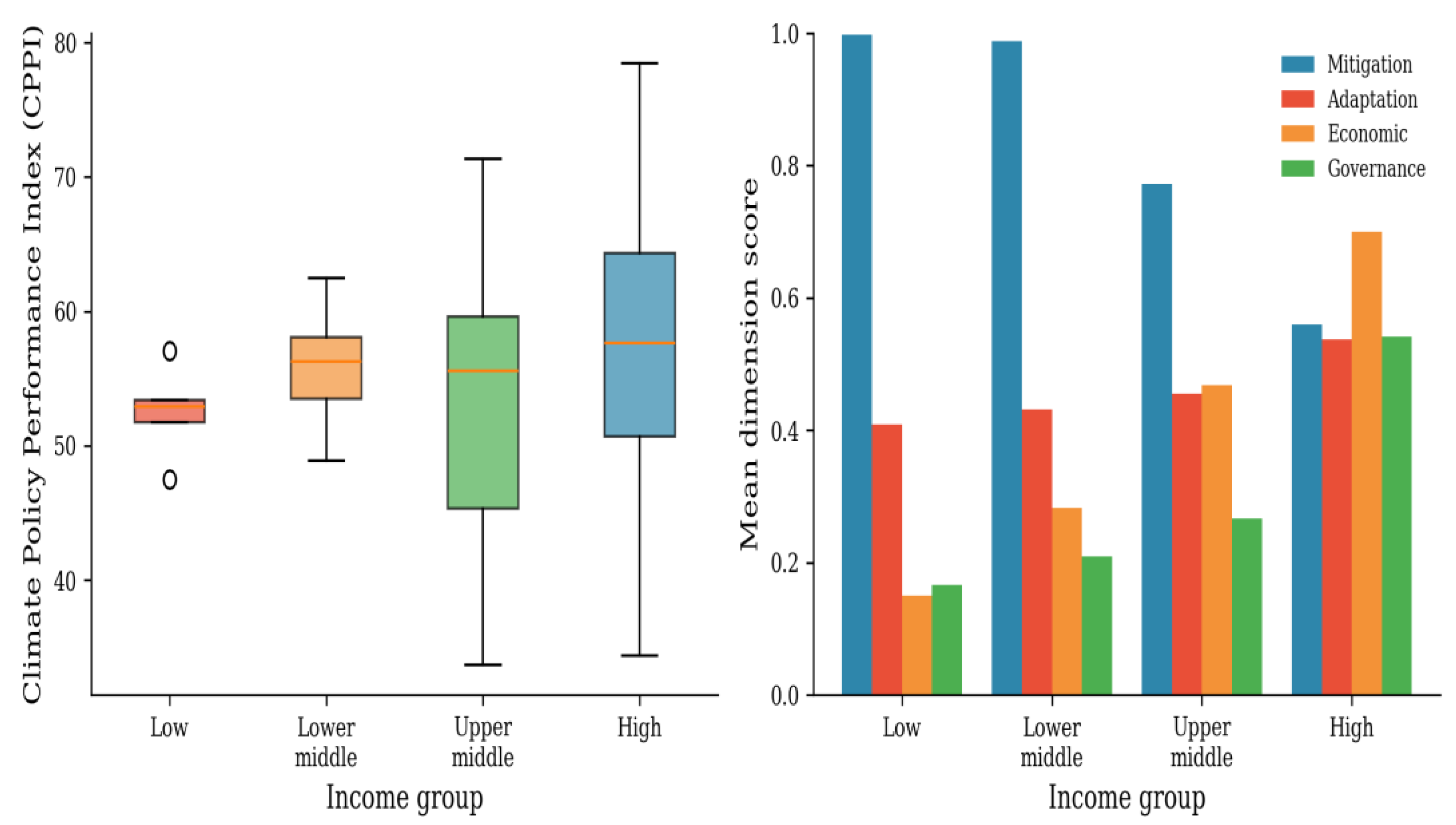

The non-monotonic relationship between income and CPPI merits particular attention. High-income countries achieve the highest mean score (57.09) but exhibit substantial internal variation, with Qatar and Kuwait among the lowest performers globally. Lower-middle-income countries achieve comparable aggregate performance (56.05) through fundamentally different dimension profiles. This finding challenges simplistic narratives that frame climate action as a luxury of wealthy nations; institutional quality and policy commitment appear at least as important as economic resources in determining climate performance.

4.4. European Union Performance and Policy Coherence

The EU-27 analysis reveals considerable internal heterogeneity despite common policy frameworks. Nordic members (Sweden, Denmark, Finland) occupy top-10 positions globally, whereas Central and Eastern European members cluster in the middle ranks. This variation persists despite uniform exposure to EU climate directives, suggesting that supranational policy frameworks interact with national institutional capacity to produce divergent outcomes. Recent research on EU decarbonization pathways confirms this heterogeneity, identifying distinct national trajectories shaped by energy system path dependencies and governance effectiveness [

38].

The EU-27 mean CPPI of 58.12 significantly exceeds the global average (55.86), confirming the region's relative climate leadership. However, the within-EU standard deviation (6.94) indicates that this aggregate performance masks substantial variation across member states. Bulgaria and Hungary score below 51, while Nordic leaders exceed 71—a 20-point gap within a nominally integrated policy space. This dispersion has implications for EU climate governance, suggesting that uniform targets may impose disproportionate burdens on lower-capacity members while leaving higher-capacity members insufficiently challenged.

The dimension-level analysis reveals that EU performance advantages are concentrated in governance (D4) and adaptation (D2), rather than in mitigation (D1). Several EU member states exhibit moderate mitigation scores despite strong institutional frameworks, reflecting continued reliance on fossil fuels in their national energy mixes. Research on EU energy transitions indicates that policy discourse often outpaces actual decarbonization progress, with rhetorical commitments exceeding observed emission reductions [

39]. The CPPI results corroborate this discourse-action gap, identifying countries where strong governance has not yet translated into proportionate emissions performance.

4.5. Policy Implications

The CPPI framework yields several policy-relevant insights. First, the identification of multiple high-performance pathways suggests that effective climate policy need not follow a single template. Countries with limited governance capacity but favourable renewable resources (e.g., Uruguay, Costa Rica) can achieve strong aggregate performance through mitigation excellence, whereas governance-strong countries can leverage institutional quality to offset historical emissions burdens. This finding supports differentiated national strategies within common global targets.

Second, the sensitivity analysis reveals that weight selection substantively affects country rankings, particularly for nations with unbalanced dimension profiles. Policymakers should recognise that index rankings reflect implicit value judgments about the relative importance of mitigation versus adaptation, current performance versus institutional capacity. The CPPI framework makes these trade-offs explicit, enabling informed interpretation rather than treating rankings as objective facts.

Third, the contribution of the governance dimension to aggregate performance underscores the importance of institutional quality for climate outcomes. Countries cannot purchase climate performance through wealth alone; effective governance translates resources into policy implementation. This finding aligns with research demonstrating that governance quality mediates the relationship between economic capacity and development outcomes [

40]. Climate policy interventions should therefore attend to institutional strengthening alongside technical measures.

Fourth, the framework's global coverage (187 countries) enables assessment of nations excluded from major-emitter-focused indices. Small island developing states, low-income African nations, and post-Soviet states are systematically evaluated, revealing both unexpected leaders (Barbados, Georgia, Armenia) and underperformers (Turkmenistan) that escape scrutiny in narrower indices. This expanded coverage supports more equitable global climate governance by including all parties to international agreements.

4.6. Limitations

Several limitations warrant acknowledgement. First, the framework relies exclusively on publicly available data, constraining indicator selection to variables with broad country coverage. Important climate policy dimensions—including policy implementation quality, climate finance flows, and technological innovation capacity—lack consistent cross-national measurement and therefore remain unrepresented. The renewable energy indicator, available for only 77 countries with complete data, particularly limits the comprehensiveness of the mitigation dimension.

Second, the additive utility model assumes preferential independence among dimensions—a strong assumption that may not hold empirically. Countries achieving high scores through compensation (high mitigation offsetting weak governance) may represent fundamentally different policy configurations than balanced performers. The multiplicative aggregation variant partially addresses this concern by penalising unbalanced profiles, but more sophisticated interaction modelling could capture dimension complementarities more accurately.

Third, the weight elicitation procedures remain normatively contested. While we present four alternative schemes and conduct extensive sensitivity analysis, the 'correct' weights ultimately depend on value judgments about climate policy priorities. Stakeholder-based weight elicitation through Analytic Hierarchy Process or swing weighting could enhance legitimacy but would introduce additional complexity and potential inconsistency.

Fourth, the cross-sectional design captures a single temporal snapshot, precluding assessment of performance trajectories or policy effectiveness over time. Countries undertaking ambitious but recent reforms may score poorly on current indicators despite promising trends. A longitudinal extension of the CPPI framework could address this limitation, although data availability constraints may require the use of shorter time series for some indicators.

Fifth, consumption-based emissions accounting—which allocates emissions to final consumers rather than territorial producers—might yield substantially different mitigation rankings for trade-intensive economies. Countries that have outsourced emissions-intensive production while maintaining high consumption levels may appear stronger under territorial accounting than their true climate footprint warrants. Data limitations preclude consumption-based analysis at present, though this remains an important direction for methodological refinement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; methodology O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; software O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; validation O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; formal analysis O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; investigation TO.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; resources O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; data curation O.L., K.P., O.P.; writing—original draft preparation O.P., O.L., K.P., K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; writing—review and editing O.L., K.P., O.P.; visualization K.J., Z.P. O.D., Y.V. and N.K.; supervision O.L., K.P., O.P.; project administration O.L., K.P.; funding acquisition O.P., K.J., Z.P., Y.V. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

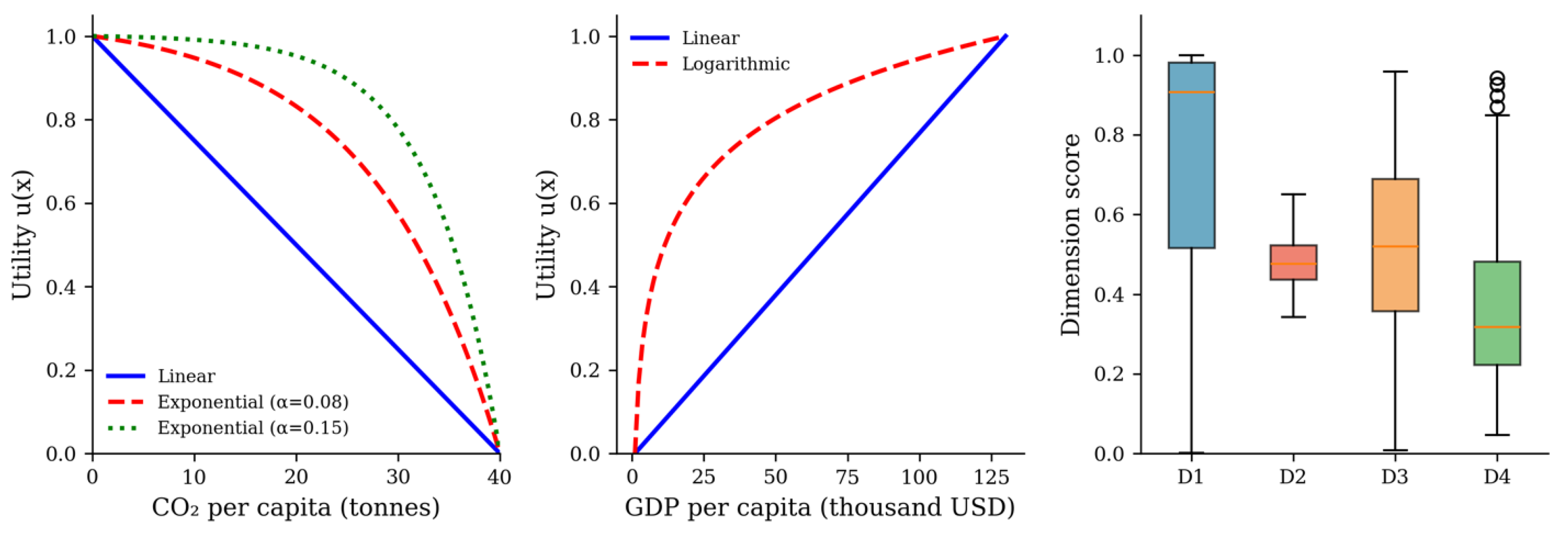

Figure 1.

Distribution of Climate Policy Performance Index scores across 187 countries. Dashed line indicates mean (55.86); dotted line indicates median (56.62).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Climate Policy Performance Index scores across 187 countries. Dashed line indicates mean (55.86); dotted line indicates median (56.62).

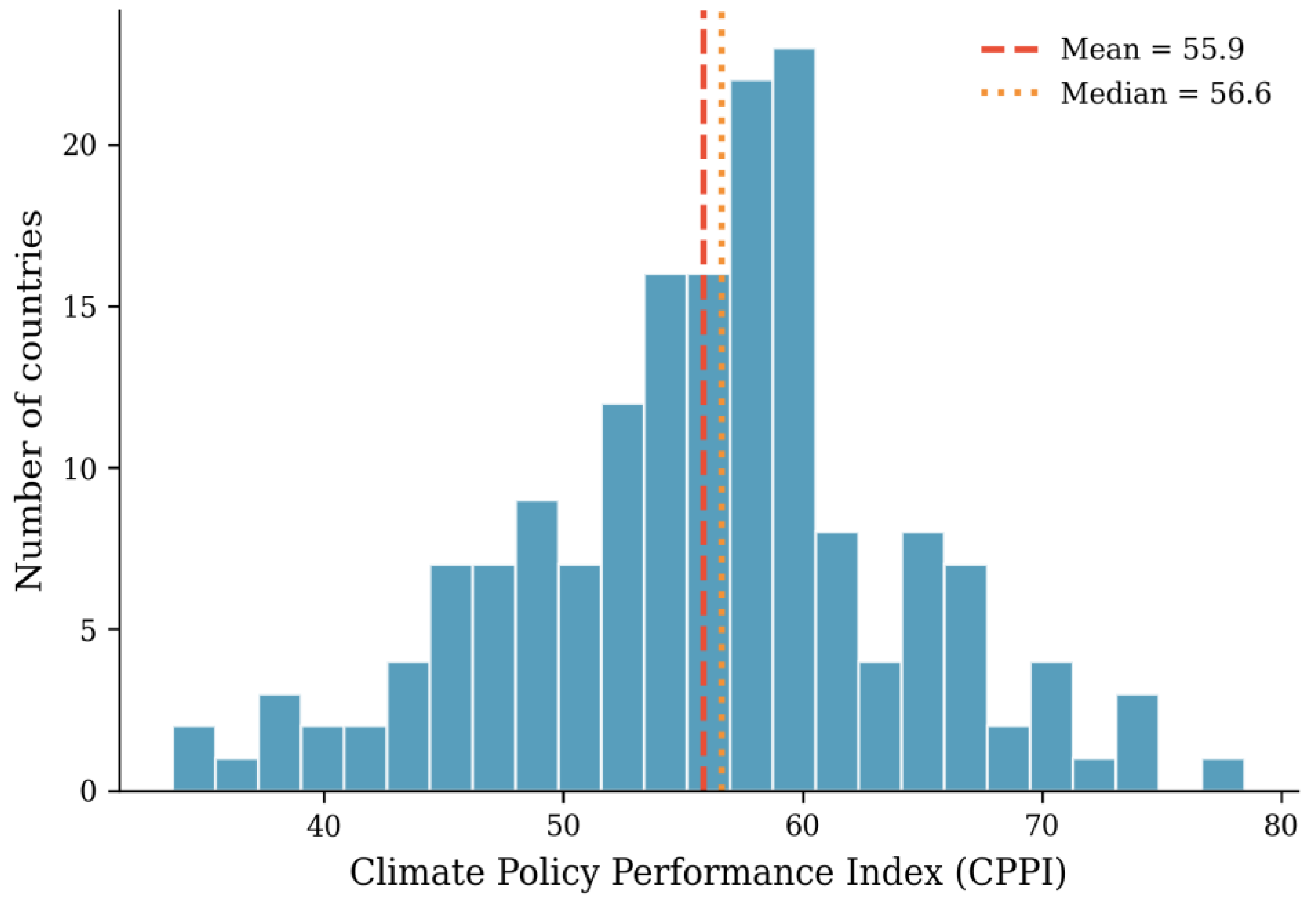

Figure 2.

Top 20 countries ranked by Climate Policy Performance Index (policy-aligned weights).

Figure 2.

Top 20 countries ranked by Climate Policy Performance Index (policy-aligned weights).

Figure 3.

Dimension scores for top 10 countries. D1 = Mitigation; D2 = Adaptation; D3 = Economic; D4 = Governance.

Figure 3.

Dimension scores for top 10 countries. D1 = Mitigation; D2 = Adaptation; D3 = Economic; D4 = Governance.

Figure 4.

Distribution of CPPI scores by world region. Box plots show median, interquartile range, and outliers.

Figure 4.

Distribution of CPPI scores by world region. Box plots show median, interquartile range, and outliers.

Figure 5.

Relationship between CPPI and CO₂ emissions per capita. Points coloured by region; selected countries labelled.

Figure 5.

Relationship between CPPI and CO₂ emissions per capita. Points coloured by region; selected countries labelled.

Figure 6.

CPPI scores by income group. (A) Distribution of overall CPPI scores. (B) Mean dimension scores by income classification.

Figure 6.

CPPI scores by income group. (A) Distribution of overall CPPI scores. (B) Mean dimension scores by income classification.

Figure 7.

Dimension profiles for top 5 countries. D1 = Mitigation; D2 = Adaptation; D3 = Economic; D4 = Governance.

Figure 7.

Dimension profiles for top 5 countries. D1 = Mitigation; D2 = Adaptation; D3 = Economic; D4 = Governance.

Figure 8.

Spearman rank correlations between alternative weighting schemes.

Figure 8.

Spearman rank correlations between alternative weighting schemes.

Figure 9.

Relationship between CPPI and ND-GAIN Climate Adaptation Index (r = 0.398, p < 0.001).

Figure 9.

Relationship between CPPI and ND-GAIN Climate Adaptation Index (r = 0.398, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Variable definitions and data sources.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and data sources.

| Variable |

Definition |

Unit |

Source |

| Mitigation dimension |

| CO₂ per capita |

Annual CO₂ emissions per person |

tonnes/capita |

GCP 2024 |

| Renewables share |

Renewable energy in primary energy mix |

% |

EI 2024 |

| Carbon intensity |

CO₂ emissions per kWh of electricity |

gCO₂/kWh |

EI 2024 |

| Adaptation dimension |

| ND-GAIN Index |

Overall climate adaptation performance |

0–100 |

ND-GAIN 2024 |

| Vulnerability |

Exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity |

0–1 |

ND-GAIN 2024 |

| Readiness |

Economic, governance, and social preparedness |

0–1 |

ND-GAIN 2024 |

| Economic context |

| GDP per capita |

Gross domestic product per person |

USD |

WDI 2024 |

| Population |

Total population |

persons |

WDI 2024 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (N = 187 countries with complete MAUT data).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (N = 187 countries with complete MAUT data).

| Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Median |

Max |

| CO₂ per capita (t) |

4.61 |

5.51 |

0.06 |

3.14 |

40.13 |

| Renewables share (%)* |

15.62 |

15.50 |

0.01 |

11.15 |

82.08 |

| ND-GAIN Index |

48.30 |

11.15 |

24.99 |

46.60 |

76.79 |

| Vulnerability |

0.43 |

0.09 |

0.25 |

0.42 |

0.64 |

| Readiness |

0.40 |

0.15 |

0.12 |

0.38 |

0.80 |

| GDP per capita (USD)** |

18,928 |

19,691 |

670 |

12,482 |

128,153 |

Table 3.

Mean values by income group.

Table 3.

Mean values by income group.

| Income Group |

N |

CO₂/capita |

Renewables (%) |

ND-GAIN |

Vulnerability |

| High income |

75 |

7.64 |

16.93 |

58.57 |

0.35 |

| Upper middle income |

46 |

2.87 |

11.16 |

45.30 |

0.42 |

| Lower middle income |

37 |

0.54 |

— |

37.06 |

0.53 |

| Low income |

6 |

0.12 |

— |

33.20 |

0.56 |

Table 4.

Mean values by region.

Table 4.

Mean values by region.

| Region |

N |

CO₂/capita |

Renewables (%) |

ND-GAIN |

| Europe |

39 |

5.25 |

22.09 |

60.83 |

| North America |

3 |

10.58 |

16.54 |

60.26 |

| East Asia & Pacific |

21 |

6.77 |

12.04 |

52.03 |

| Middle East & N. Africa |

19 |

10.40 |

3.43 |

49.63 |

| Latin America |

24 |

3.26 |

24.40 |

44.94 |

| South Asia |

8 |

1.43 |

11.03 |

40.79 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

49 |

0.87 |

3.65 |

38.17 |

Table 5.

Pairwise correlations.

Table 5.

Pairwise correlations.

| |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

| (1) CO₂ per capita |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

| (2) Renewables share |

−0.27 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

| (3) ND-GAIN Index |

0.48 |

0.41 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

| (4) Vulnerability |

−0.45 |

−0.31 |

−0.85 |

1.00 |

|

|

| (5) Readiness |

0.43 |

0.40 |

0.95 |

−0.64 |

1.00 |

|

| (6) GDP per capita |

0.73 |

0.14 |

0.80 |

−0.67 |

0.80 |

1.00 |

Table 6.

Attribute hierarchy for climate policy evaluation.

Table 6.

Attribute hierarchy for climate policy evaluation.

| Dimension |

Attribute |

Variable |

Direction |

| D₁ Mitigation |

A₁₁ Emissions intensity |

CO₂ per capita |

− |

| |

A₁₂ Clean energy |

Renewables share |

+ |

| |

A₁₃ Decarbonization |

Carbon intensity of electricity |

− |

| D₂ Adaptation |

A₂₁ Vulnerability |

ND-GAIN vulnerability score |

− |

| |

A₂₂ Readiness |

ND-GAIN readiness score |

+ |

| |

A₂₃ Adaptive capacity |

ND-GAIN adaptive capacity |

+ |

| D₃ Economic |

A₃₁ Development level |

GDP per capita |

+ |

| |

A₃₂ Economic readiness |

ND-GAIN economic readiness |

+ |

| D₄ Governance |

A₄₁ Governance quality |

ND-GAIN governance score |

+ |

| |

A₄₂ Social readiness |

ND-GAIN social readiness |

+ |

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics for CPPI and dimension scores (N = 187)

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics for CPPI and dimension scores (N = 187)

| Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

Median |

| CPPI (Policy weights) |

55.86 |

8.03 |

33.67 |

78.46 |

56.62 |

| D1: Mitigation |

0.757 |

0.248 |

0.001 |

0.998 |

0.818 |

| D2: Adaptation |

0.482 |

0.069 |

0.351 |

0.650 |

0.488 |

| D3: Economic |

0.523 |

0.210 |

0.150 |

0.958 |

0.519 |

| D4: Governance |

0.373 |

0.210 |

0.115 |

0.943 |

0.345 |

Table 9.

Top 15 countries by Climate Policy Performance Index

Table 9.

Top 15 countries by Climate Policy Performance Index

| Rank |

Country |

CPPI |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| 1 |

Norway |

78.46 |

0.761 |

0.650 |

0.958 |

0.897 |

| 2 |

Sweden |

74.02 |

0.719 |

0.639 |

0.819 |

0.870 |

| 3 |

Denmark |

73.59 |

0.644 |

0.639 |

0.888 |

0.927 |

| 4 |

Iceland |

73.38 |

0.798 |

0.597 |

0.842 |

0.745 |

| 5 |

Barbados |

71.36 |

0.885 |

0.555 |

0.522 |

0.795 |

| 6 |

Georgia |

71.14 |

0.923 |

0.577 |

0.790 |

0.483 |

| 7 |

Finland |

71.06 |

0.604 |

0.632 |

0.807 |

0.943 |

| 8 |

Uruguay |

70.26 |

0.945 |

0.551 |

0.589 |

0.591 |

| 9 |

Grenada |

69.75 |

0.924 |

0.572 |

— |

0.620 |

| 10 |

Switzerland |

69.17 |

0.611 |

0.630 |

0.827 |

0.824 |

| 11 |

Armenia |

68.26 |

0.938 |

0.555 |

0.684 |

0.426 |

| 12 |

Mauritius |

67.67 |

0.912 |

0.520 |

0.760 |

0.439 |

| 13 |

New Zealand |

67.48 |

0.641 |

0.589 |

0.857 |

0.725 |

| 14 |

Fiji |

66.86 |

0.964 |

0.510 |

— |

0.498 |

| 15 |

Cape Verde |

66.70 |

0.974 |

0.544 |

0.520 |

0.425 |

Table 10.

Bottom 20 countries by Climate Policy Performance Index

Table 10.

Bottom 20 countries by Climate Policy Performance Index

| Rank |

Country |

CPPI |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| 168 |

Libya |

44.24 |

0.547 |

0.413 |

0.463 |

0.115 |

| 169 |

Brunei |

44.19 |

0.252 |

0.528 |

0.847 |

0.477 |

| 170 |

Pakistan |

44.08 |

0.940 |

0.351 |

0.239 |

0.181 |

| 171 |

Mongolia |

43.52 |

0.573 |

0.475 |

0.551 |

0.245 |

| 172 |

Oman |

43.08 |

0.266 |

0.535 |

0.739 |

0.381 |

| 173 |

Iraq |

42.75 |

0.641 |

0.415 |

0.458 |

0.177 |

| 174 |

Kazakhstan |

42.10 |

0.361 |

0.515 |

0.698 |

0.305 |

| 175 |

Russia |

41.77 |

0.384 |

0.537 |

0.682 |

0.215 |

| 176 |

Saudi Arabia |

41.15 |

0.172 |

0.499 |

0.779 |

0.394 |

| 177 |

Bahrain |

40.08 |

0.104 |

0.520 |

0.716 |

0.463 |

| 178 |

Iran |

39.79 |

0.422 |

0.449 |

0.480 |

0.214 |

| 179 |

Kuwait |

38.84 |

0.035 |

0.520 |

0.852 |

0.456 |

| 180 |

Venezuela |

38.65 |

0.714 |

0.424 |

— |

0.165 |

| 181 |

Bangladesh |

37.35 |

0.946 |

0.368 |

0.179 |

0.158 |

| 182 |

Qatar |

36.88 |

0.001 |

0.516 |

0.946 |

0.517 |

| 183 |

Trinidad & Tobago |

34.38 |

0.081 |

0.480 |

0.598 |

0.348 |

| 184 |

Turkmenistan |

33.67 |

0.377 |

0.451 |

0.612 |

0.115 |

Table 11.

Regional summary statistics

Table 11.

Regional summary statistics

| Region |

N |

Mean |

SD |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| Europe |

39 |

59.92 |

7.72 |

0.598 |

0.547 |

0.694 |

0.601 |

| Other |

27 |

57.24 |

11.19 |

0.829 |

0.475 |

0.612 |

0.379 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

48 |

56.56 |

4.81 |

0.971 |

0.439 |

0.315 |

0.222 |

| East Asia & Pacific |

19 |

55.62 |

7.01 |

0.636 |

0.507 |

0.637 |

0.448 |

| Latin America |

24 |

54.67 |

7.97 |

0.817 |

0.456 |

0.460 |

0.267 |

| North America |

3 |

53.75 |

8.99 |

0.451 |

0.536 |

0.705 |

0.564 |

| South Asia |

8 |

51.04 |

10.26 |

0.750 |

0.421 |

0.374 |

0.300 |

| MENA |

19 |

49.12 |

7.36 |

0.538 |

0.485 |

0.604 |

0.333 |

Table 12.

CPPI statistics under alternative weighting schemes

Table 12.

CPPI statistics under alternative weighting schemes

| Scheme |

w(D1) |

w(D2) |

w(D3) |

w(D4) |

Mean |

SD |

| Equal |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

53.12 |

9.03 |

| Policy |

0.35 |

0.30 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

55.86 |

8.03 |

| Mitigation |

0.50 |

0.25 |

0.10 |

0.15 |

60.11 |

10.35 |

| Adaptation |

0.25 |

0.50 |

0.10 |

0.15 |

53.61 |

6.95 |

| Multiplicative |

— |

— |

— |

— |

48.73 |

12.84 |

Table 13.

Correlations between CPPI and input indicators

Table 13.

Correlations between CPPI and input indicators

| Indicator |

r |

p-value |

N |

| ND-GAIN Index |

0.398 |

<0.001 |

187 |

| ND-GAIN Readiness |

0.491 |

<0.001 |

187 |

| ND-GAIN Vulnerability |

−0.197 |

0.007 |

187 |

| CO₂ per capita |

−0.275 |

<0.001 |

187 |

| GDP per capita |

0.178 |

0.024 |

161 |

| Renewables share |

0.312 |

0.006 |

77 |

Table 14.

EU-27 member states ranked by CPPI (top 10)

Table 14.

EU-27 member states ranked by CPPI (top 10)

| EU Rank |

Country |

Global Rank |

CPPI |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| 1 |

Sweden |

2 |

74.02 |

0.719 |

0.639 |

0.819 |

0.870 |

| 2 |

Denmark |

3 |

73.59 |

0.644 |

0.639 |

0.888 |

0.927 |

| 3 |

Finland |

7 |

71.06 |

0.604 |

0.632 |

0.807 |

0.943 |

| 4 |

Netherlands |

17 |

65.96 |

0.535 |

0.623 |

0.855 |

0.782 |

| 5 |

Austria |

19 |

65.90 |

0.606 |

0.617 |

0.810 |

0.673 |

| 6 |

Ireland |

22 |

64.89 |

0.528 |

0.597 |

0.877 |

0.737 |

| 7 |

Luxembourg |

23 |

64.60 |

0.448 |

0.618 |

0.949 |

0.840 |

| 8 |

Germany |

25 |

63.82 |

0.466 |

0.606 |

0.863 |

0.778 |

| 9 |

France |

27 |

63.18 |

0.593 |

0.574 |

0.777 |

0.636 |

| 10 |

Portugal |

28 |

62.83 |

0.694 |

0.539 |

0.636 |

0.529 |