1. Introduction

Vascular anomalies (VAs), represented by hemangiomas and vascular malformations, include a broad spectrum of disorders that, despite a high prevalence of approximately 2.2% worldwide, present a significant diagnostic challenge [

1,

2,

3]. These disorders encompass nearly 100 distinct subtypes with vastly different pathogenic mechanisms and clinical courses [

4]. However, they often exhibit strikingly similar visual appearances. For example, it could be a severe challenge for clinicians to distinguish between a deep infantile hemangiomas and a venous malformation, particularly in primary care and resource-limited settings. Misdiagnosis is critical, as therapeutic approaches differ markedly; a strategy effective for a tumor may be ineffective or harmful for a malformation [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for intelligent systems capable of assisting clinicians in both precise differentiation and evidence-based treatment planning.

The recent surge in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs/LLMs) [

9,

10,

11,

12] has sparked hope for automated “generalist” medical assistants [

13,

14]. Ideally, such models would ingest lesion images and patient history to output comprehensive clinical decisions. However, current state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-source models struggle in this specialized domain. Our preliminary investigations reveal that generic MLLMs fail to capture the subtle, fine-grained visual features required to distinguish VA subtypes. Furthermore, direct post-training of these large models on medical data faces two hurdles: first, the scarcity of high-quality, aligned image-text pairs in this niche field limits effective feature alignment [

15]; second, aggressive instruction tuning [

16] carries the risk of

catastrophic forgetting, where the model’s inherent reasoning and generalization capabilities are degraded in favor of rote memorization of the training set with formatted instructions [

17,

18,

19].

Most critically, clinical decision-making is not merely a classification task; it must be evidence-based and transparent. Standard “black-box” end-to-end models (e.g. static tuned MLLMs) cannot dynamically interact with updated clinical guidelines. A reliable diagnostic system requires the visual acuity to identify the disease and the cognitive flexibility to retrieve and apply current medical standards.

To address aforementioned challenges, we propose HevaDx, an evidence-based agentic system bridging perception and reasoning, for the diagnosis and treatment recommendations of hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Our core insight is that visual diagnosis and clinical reasoning, while related, require different optimization strategies. Visual diagnosis relies on high-fidelity feature extraction [

20], while treatment recommendation relies on logical deduction and knowledge retrieval . Therefore, rather than forcing a single MLLM to handle both, we design a cooperative agentic system. We employ a lightweight, visually-specialized model (DINOv2) [

21] to extract subtle lesion features for precise diagnosis. This diagnostic output, combined with patient history, is then fed into an LLM (Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct) [

22] equipped with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [

23,

24,

25]. This allows the LLM to leverage its superior reasoning capabilities to synthesize the diagnosis, patient history and retrieved clinical guidelines, ensuring recommendations are both accurate and clinically grounded. Experimental results demonstrate that HevaDx achieves a top-3 accuracy of

94.8% for diagnosis and

83.3% for treatment recommendations.

Our contributions are threefold:

We construct a high-quality, expert-annotated cohort of 7,565 VA cases to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of SOTA open-source MLLMs. This large-scale benchmarking empirically exposes the significant limitations of generalist models in specialized diagnostics.

We introduce HevaDx, a novel modular system that explicitly decouples the clinical workflow into a visual specialist and a reasoning specialist. By combining a lightweight, adaptable visual encoder with a knowledge-augmented LLM, we achieve superior diagnostic accuracy.

We establish a rigorous pipeline for dataset construction, incorporating strict quality control, Region of Interest (ROI) annotation, and class balancing strategies, mitigating the long-tail distribution problem inherent in clinical data. We also validate that a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) mechanism enhances clinical safety by transforming opaque model outputs into transparent, evidence-based reasoning chains grounded in medical guidelines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Large-Scale VA Dataset

2.1.1. Data Collection and Annotation

The dataset used in this study is independently curated by the Departments of Plastic Surgery and Laser Aesthetics at the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. All images were collected from patients with vascular anomalies who attended the outpatient clinic between January 2019 and August 2025. Clinical photographs were acquired using a Canon EOS 80D DSLR camera equipped with an EF 50 mm f/1.4 USM prime lens in a standardized photography studio under controlled lighting, ensuring high-resolution and consistent visualization of lesion areas. All samples were obtained retrospectively from routine clinical practice. Each case was confirmed by pathological examination or by senior clinicians in accordance with the Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations (2024 Edition) [

5]. For each patient, lesion images were paired with corresponding patient history, diagnostic information, and treatment recommendations. Diagnostic labels and treatment recommendations were independently annotated by at least two senior plastic surgeons or dermatologists. In instances where the two experts provided inconsistent diagnostic categories or treatment suggestions, a third senior expert adjudicated and issued the final annotation. All data were anonymized prior to analysis, ensuring that no patient-identifiable information was retained.

2.1.2. Quality Control and Dataset Statistics

After initial data collection, all images and corresponding patient information underwent a rigorous quality control process. Images with poor resolution, blurring, improper framing, or incorrect labeling were excluded from the dataset. Cases with incomplete clinical records or formatting inconsistencies were also removed to ensure that the final dataset maintained high integrity and reliability for downstream analysis. This quality check process was performed independently by five trained research staff members, and any discrepancies were resolved by a senior clinician.

Following quality control, the final dataset comprised a total of 7565 patients with various vascular anomalies. The distributions of diagnosis and treatment options are summarized in

Figure 1. The most common diagnosis was infantile hemangioma (6395 cases, 84.5%), followed by port-wine stain (601 cases, 7.9%), venous malformation (287 cases, 3.8%), and other low-frequency categories (combined as 282 cases, 3.7%)

1. Top treatment options included topical medication (3232 cases, 42.7%), laser therapy (1105 cases, 14.6%), oral medication (1005 cases, 13.3%), and injection/sclerotherapy (933 cases, 12.3%). Surgical interventions, interventional therapies, electrocoagulation, and observation/follow-up accounted for the remaining cases. Additionally, females (5213, 68.9%) outnumbers males (2352, 31.1%) in our dataset.

By applying this systematic processing and annotation workflow, we ensured the accuracy, completeness, and reliability of the dataset for subsequent benchmarking and method development.

Table 1 presents the complete summary of the dataset statistics.

2.2. Evaluations on Advanced Open-source MLLMs

The diagnosis of VA relies on the precise interpretation of fine-grained visual cues—specifically color depth, texture patterns, boundary morphology, and anatomical correlation—features often underrepresented in the massive, web-crawled datasets used to train generalist models. Given that these models lack domain-specific instruction alignment, a systematic evaluation of their zero-shot inference capabilities is critical. The evaluations serves two purposes: first, to establish a rigorous performance baseline and identify potential hallucinations in specialized contexts; and second, to provide empirical evidence guiding the architectural design of our proposed system.

We randomly sampled 480 cases from our VA dataset for evaluation, ranging from common hemangiomas to rare vascular malformations and simulating the challenging long-tail distribution encountered in real-world clinical practice. Our model selection criteria balanced SOTA performance with clinical deployability. We restricted the parameter space to the 4B–32B range, which facilitates practical clinical deployment

2. We evaluated two distinct categories of model architectures: (1)

general-purpose models including Qwen2.5-VL series [

26], Kimi-VL-16B [

27] and LLaVA-v1.5-7B [

28]; (2)

medical-specialized models like MedGemma series [

29] and LLaVA-Med-v1.5-Mistral-7B [

30]. We report the top-1 and top-3 accuracy for both diagnosis and treatment recommendations. See

Section 4.1 for detailed results.

2.3. The HevaDx System

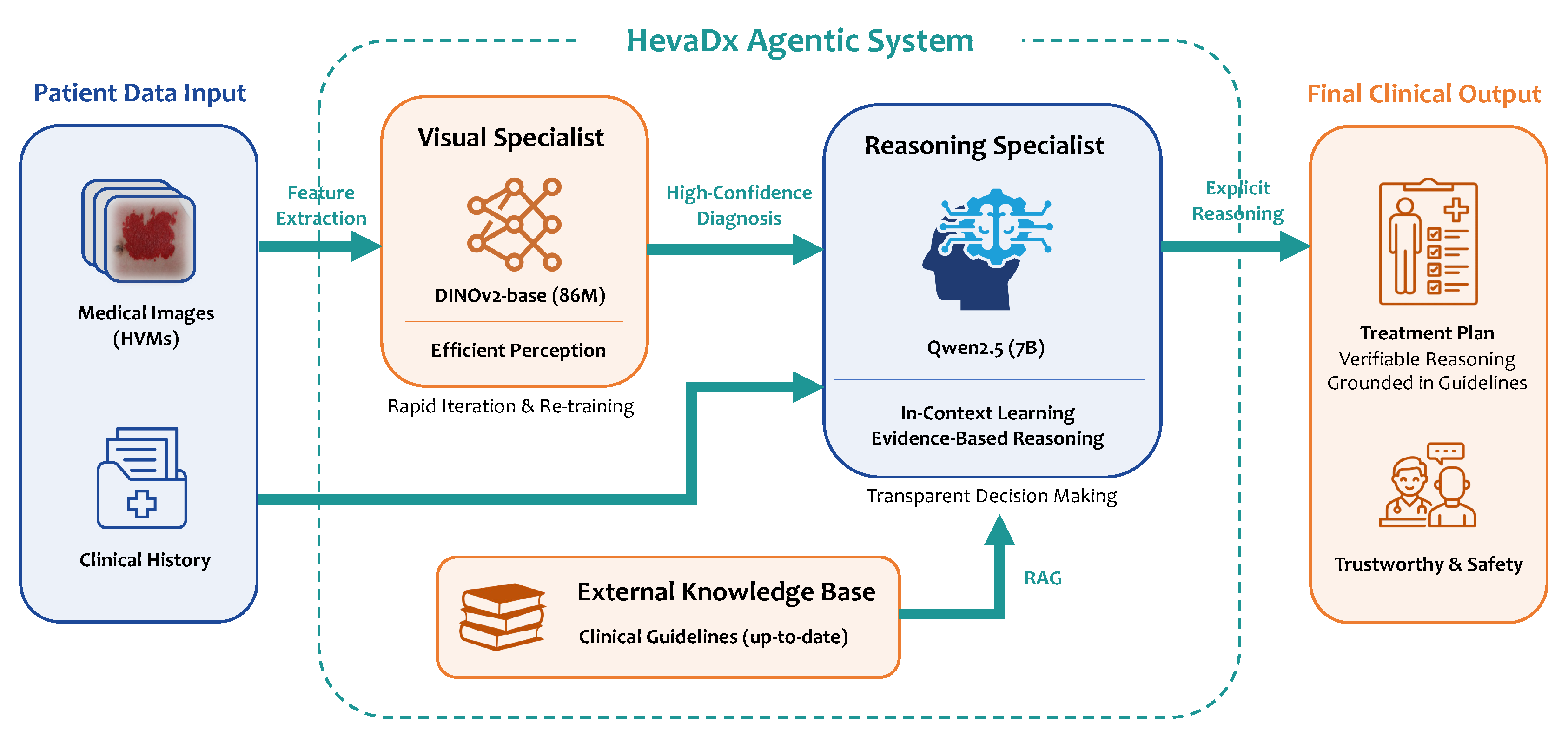

To address the limitations identified in the previous evaluation—specifically the trade-off between visual precision and reasoning capability—we propose HevaDx, a modular agentic system. Unlike traditional end-to-end architectures that attempt to optimize a single network for both perception and logic, HevaDx decouples the clinical workflow into two specialized components: a lightweight visual specialist for precise disease identification and a knowledge-augmented reasoning specialist for evidence-based treatment planning.

Figure 2.

Overview of the HevaDx agentic system. HevaDx decouples the clinical workflow into two specialized components: a lightweight visual specialist for precise disease identification and a knowledge-augmented reasoning specialist for evidence-based treatment planning.

Figure 2.

Overview of the HevaDx agentic system. HevaDx decouples the clinical workflow into two specialized components: a lightweight visual specialist for precise disease identification and a knowledge-augmented reasoning specialist for evidence-based treatment planning.

2.3.1. The Visual Specialist: Efficient Perception with DINOv2

The diagnosis of vascular anomalies hinges on the detection of subtle morphological cues, such as the depth of red discoloration, the texture of the lesion surface, and boundary distinctness. MLLMs often struggle with these details due to the domain gap [

31] between natural and medical imagery. To overcome this, we employ DINOv2 [

21], a self-supervised vision transformer, as our dedicated visual backbone.

We selected DINOv2-base to harness the powerful visual feature extraction capabilities it obtained from massive pre-training. By fine-tuning this lightweight model with our VA cases, we ensure the model captures the fine-grained pathological visual features. Furthermore, the lightweight nature of the model (86M parameters) offers a critical practical advantage: adaptivity. As clinical data accumulation is a continuous process, medical AI systems require frequent updates. Retraining a massive MLLM is computationally expensive, whereas our decoupled visual specialist can be rapidly iterated and re-trained as new patient data becomes available, ensuring the diagnostic module remains current with minimal computational cost.

2.3.2. The Reasoning Specialist: Transparent, Evidence-Based Decision Making

Once a high-confidence diagnosis is established by the visual specialist, the focus shifts to therapeutic management—a task requiring logical deduction rather than visual pattern recognition. For this, we utilize an LLM (Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct

3) [

22] as our reasoning specialist.

Our approach diverges from standard methods by strictly avoiding instruction-tuning on the LLM. Aggressive fine-tuning on limited medical data often degrades a model’s general reasoning capabilities (

catastrophic forgetting). Instead, we leverage the model’s inherent

in-context learning (ICL) capabilities [

32,

33,

34]. The system operates by feeding the diagnostic output from the visual specialist, along with the patient’s clinical history, into the LLM. Crucially, we augment this input with relevant, up-to-date clinical guidelines retrieved from an external knowledge base. This design ensures two key clinical requirements: evidence-based reasoning and transparency. Specifically, by grounding the generation process in retrieved guidelines, the system minimizes hallucinations [

35,

36] and ensures recommendations align with current medical standards. Also, unlike “black-box” end-to-end models, HevaDx produces explicit reasoning chains. Clinicians can verify exactly how a reasoning trajectory reach a specific treatment recommendation, fostering trust and safety in the clinical decision-making process.

3. Data Preprocessing and Setup

3.1. Dataset Stratification and Balancing

To prevent model bias toward high-prevalence diseases and ensure robust evaluation across the spectrum of vascular anomalies, we implemented a strict data balancing strategy. From our full dataset, we selected six representative disease categories with sufficient sample sizes: Port-wine Stain (PWS), Infantile Hemangioma (IH), Venous Malformation (VM), Verrucous Hemangioma (VH), Verrucous Venous Malformation (VVM), and Nevi.

We employed stratified sampling to construct an independent test set that reflects the diversity of the disease spectrum. Specifically, we randomly selected a fixed number of cases for each category, resulting in a total of 96 test samples: PWS (), IH (), VM (), VH (), VVM (), and Nevi (). The remaining images constituted the training set. To address the long-tail distribution inherent in medical data, we applied a class balancing strategy during training set construction. For common disease categories exceeding 200 samples, we performed Random Undersampling to cap the count at 200. For minority classes with fewer than 200 samples, we retained all available high-quality images and applied Random Oversampling (duplication) to approximate a balanced distribution.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Prior to training, we performed rigorous data cleaning and fine-grained annotation to maximize signal-to-noise ratio.

Region of interest (ROI) annotation: We manually annotated bounding boxes for all lesion images. This step forces the model to focus its attention on the relevant pathological features, eliminating interference from background factors (e.g., clothing, medical equipment, or unrelated skin areas).

Quality control: We conducted a secondary review to filter out low-quality samples. Images where the lesion location was ambiguous, or the diagnosis was clinically controversial, were excluded to prevent label noise.

Following this curation process, the final verified training set comprised the following distribution: PWS (), IH (), VM (), VH (), VVM (), and Nevi ().

3.3. Implementation Details

Visual Specialist Training: We trained the DINOv2-base model as our visual specialist. The training process was accelerated using a single NVIDIA A100 GPU (80GB). We utilized the AdamW optimizer [

37,

38] with a learning rate of

. The model was trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 16.

Reasoning Specialist Setup: For the reasoning component, we employed a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework. We constructed a specialized external knowledge base derived from the physician-summarized Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations (2024 Edition) [

5]. This ensures that the LLM’s (Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct) treatment recommendations are grounded in the latest clinical evidence.

Metrics: To comprehensively assess system performance, we report the top-1 and top-3 accuracy for both the diagnosis task and the treatment recommendation task. The evaluation was conducted using the independent test set described in

Section 3.1. Note that since the reasoning specialist need to receive diagnostic results from the visual specialist to make further actions,

the top-1 and top-3 accuracy for treatment recommendations are both based on the top 1 diagnosis.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Evaluations on MLLMs

The evaluation results shown in

Table 2 reveal that while general-purpose models demonstrate a stronger baseline than specialized medical variants, current architectures remain insufficient for clinical deployment. Surprisingly, the generalist Qwen2.5-VL-32B outperformed the medically pre-trained MedGemma-27B by a obvious margin in diagnostic accuracy (58.1% vs. 35.6%), suggesting that the advantages of tuning in general medicine dataset cannot be generalized to specific disease areas (e.g. VA). A diagnostic accuracy of roughly 58% implies that nearly half of the cases are still misclassified, highlighting the inability of standard visual encoders to resolve the fine-grained morphological details necessary for differentiating complex vascular anomalies.

Moreover, a critical capability collapse occurs when shifting from visual diagnosis to therapeutic planning. Despite achieving moderate diagnostic success, the best-performing model could only recommend the correct treatment in 16.3% of cases. This steep decline underscores a fundamental reasoning gap: existing end-to-end models often fail to translate visual findings into evidence-based management strategies. This disconnect between perception and logic empirically validates the necessity of our proposed HevaDx system, which explicitly decouples visual feature extraction from clinical reasoning to bridge the divide between accurate diagnosis and reliable treatment.

4.2. Results of Evaluations on HevaDx

4.2.1. Main Results

As shown in

Table 3, our proposed HevaDx achieved superior performance across all metrics, significantly surpassing the capabilities of the advanced MLLMs evaluated in

Section 4.14. Specifically, the system attained a top-1 diagnostic accuracy of 75.0% and a remarkable top-3 accuracy of 94.8%, demonstrating that the specialized DINOv2 backbone effectively resolves the fine-grained visual ambiguity of vascular anomalies. Most notably, the system bridged the previously identified reasoning gap in therapeutic decision-making: Treatment top-1 accuracy surged to 62.5%, and top-3 accuracy reached 83.3%. These results confirm that decoupling visual perception from clinical reasoning, when

augmented with retrieved guidelines, provides a far more reliable foundation for medical decision-making than standard end-to-end approaches.

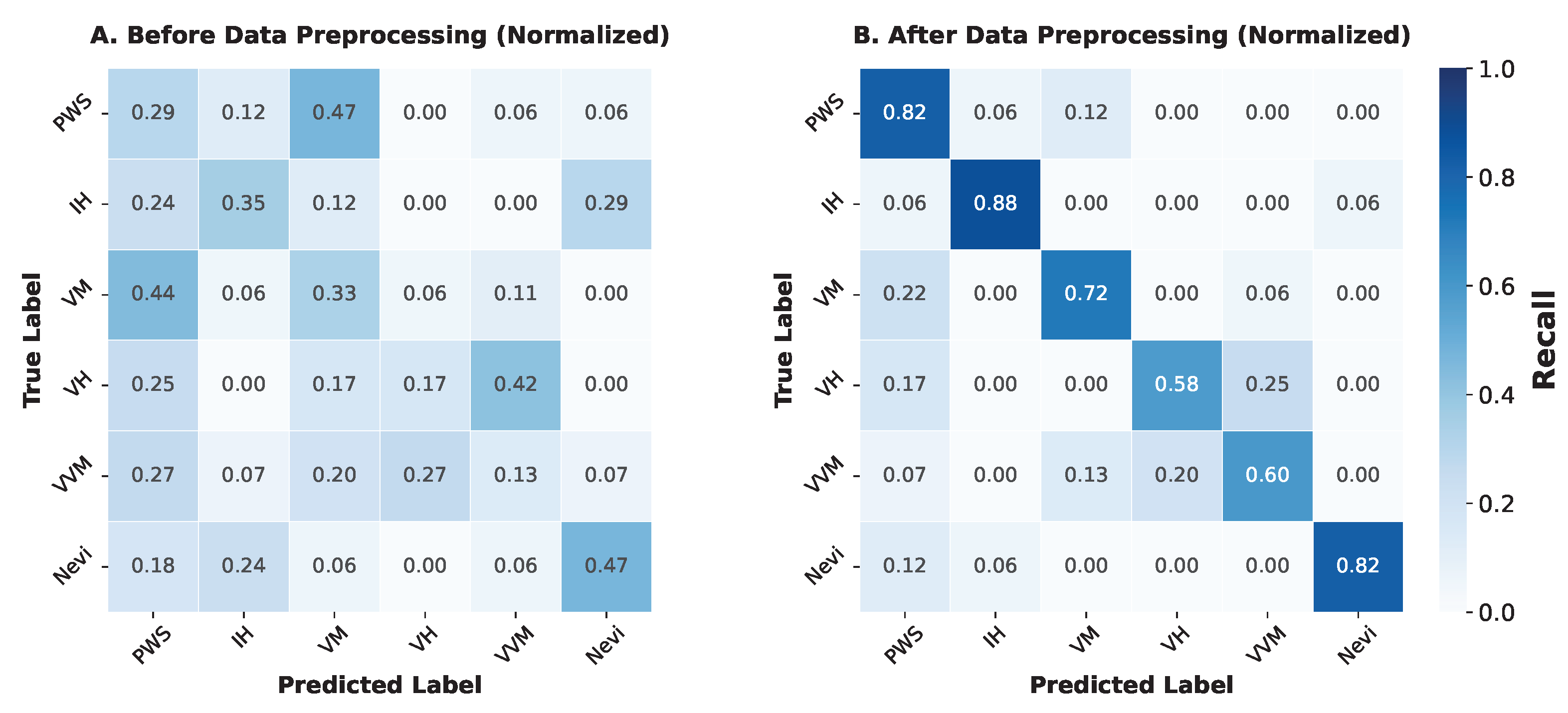

4.2.2. Ablation Study on Data Preprocessing

To quantify the impact of our rigorous data curation pipeline—specifically the region-of-interest (ROI) annotation and class balancing—we conducted a comparative analysis between a model trained on raw, noisy data and one trained on our refined dataset.

-

Resolution of Clinical Mimicry: The normalized confusion matrices further elucidate how preprocessing mitigates phenotypic confusion. As shown in

Figure 3 A (Before Preprocessing), the baseline model struggled with clinical mimicry, appearing unable to distinguish intrinsic lesion features from background noise. For instance, in the raw setting, PWS was frequently misclassified as VM (8 out of 17 cases), resulting in a recall of only 0.29. Similarly, VVM was heavily confused with PWS and VH, achieving a recall of just 0.13.

In contrast,

Figure 3 B (After Preprocessing) demonstrates strong diagonal dominance, indicating robust correct classification. The rigorous ROI annotation forced the visual encoder to attend to fine-grained texture and boundary features rather than background artifacts. Consequently, the confusion between PWS and VM was drastically reduced (only 2 misclassified), raising the PWS recall to 0.82. Although some confusion persists between the highly similar “verrucous” subtypes (VH and VVM), the overall class separability has been significantly enhanced, confirming that high-quality data curation is a prerequisite for resolving the long-tail distribution in vascular anomaly diagnosis.

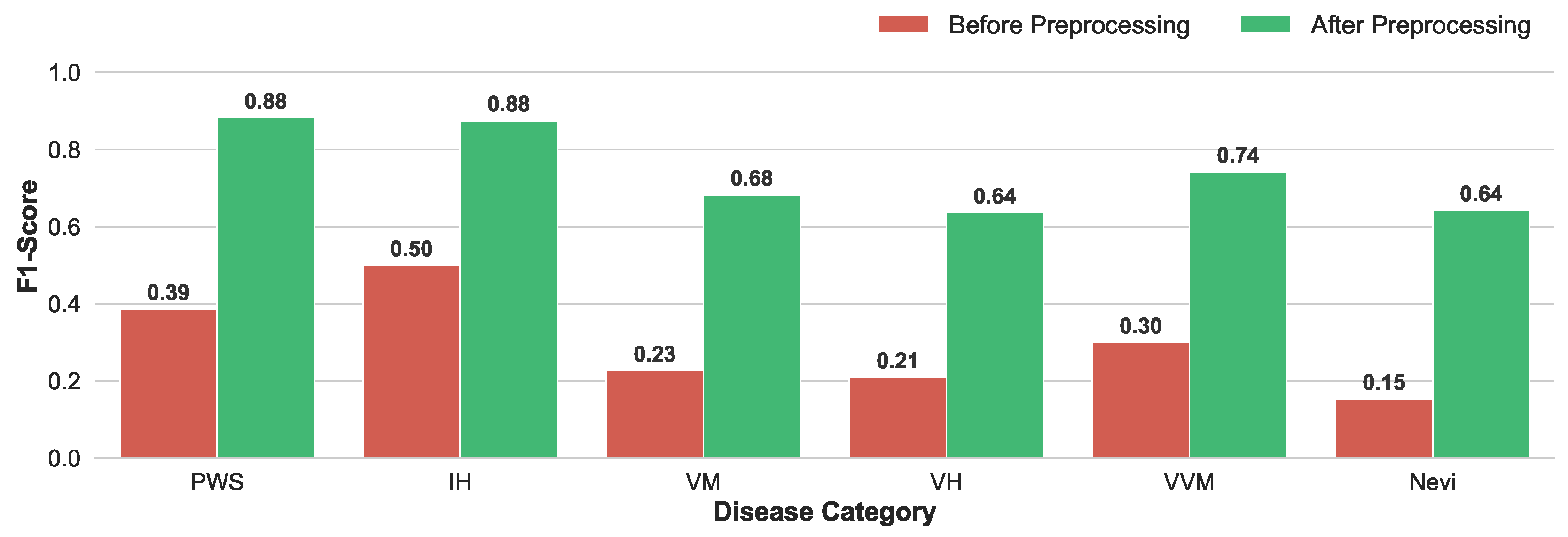

Enhancement of Discriminative Capability: The quantitative improvement is visualized in

Figure 4. The model trained on preprocessed data exhibited dramatic performance gains across all disease categories. Notably, the F1-score for PWS surged from 0.39 to 0.88, and IH improved from 0.50 to 0.88. Even for morphologically complex subtypes like VH, which previously suffered from extremely low recognition (F1=0.21), the preprocessing strategy restored the model’s discriminative capability, raising the F1-score to 0.64.

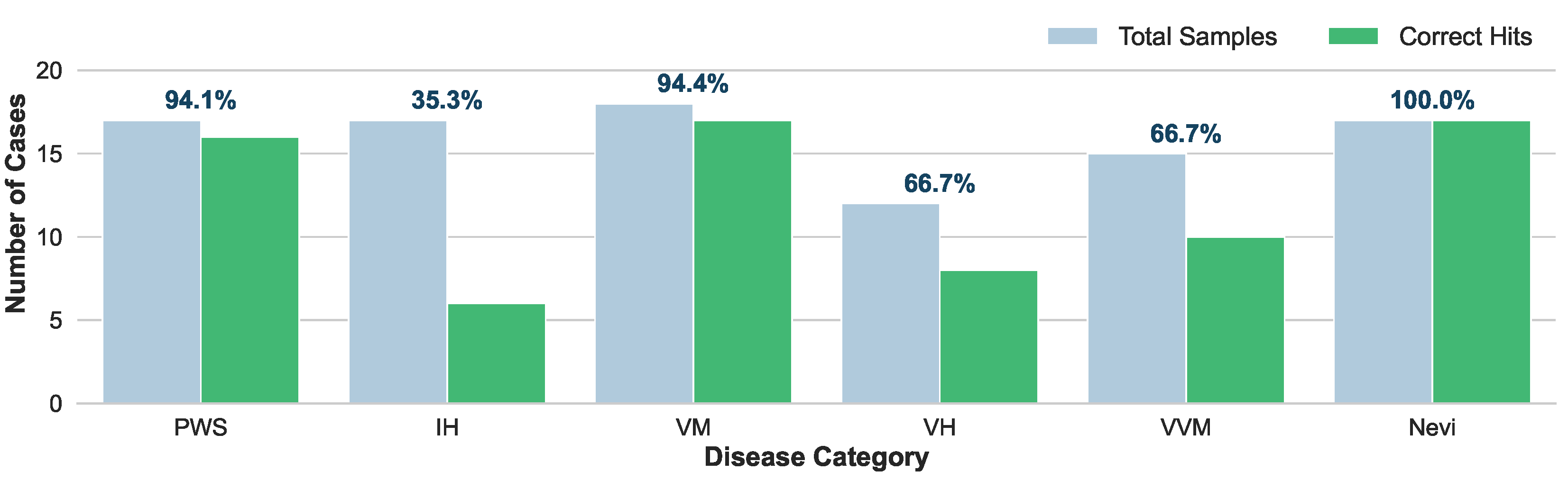

4.2.3. Qualitative Analysis on Reasoning Specialist

To strictly isolate and evaluate the logical deduction capabilities of our reasoning specialist, we conducted a controlled experiment where the ground-truth diagnostic labels were directly provided to the reasoning specialist. This setup effectively bypasses visual perception errors, allowing us to assess HevaDx’s ability to map a confirmed diagnosis to an appropriate therapeutic regimen based on retrieved guidelines.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, HevaDx demonstrates high efficacy in disease categories with highly standardized treatment protocols. For Nevi (

), it achieved 100% accuracy (17/17 hits). Since surgical excision is the dominant gold standard for Nevi, the model easily aligned with clinical consensus. For VM and PWS, HevaDx achieved 94.4% (17/18) and 94.1% (16/17) accuracy, respectively. Specifically, for PWS, the guideline recommendation is overwhelmingly “Laser Therapy”, and for VM, it is “Injection / Sclerotherapy”. The system’s high success rate here confirms its ability to correctly retrieve and apply strong evidence from the provided guidelines.

In contrast, IH represents a complex decision boundary, achieving a significantly lower top-1 accuracy of 35.3% (6/17). This discrepancy is not a failure of reasoning, but a reflection of clinical complexity. The ground truth for IH varies widely among “Oral Medication” (), “Topical Medication” (), “Surgery” (), and “Observation / Follow-up” (), often depending on subtle patient-specific factors (e.g., age, tumor depth, growth phase) that may be detailed in the medical history. The model displayed a distinct preference for “Oral Medication” (Propranolol) (predicting 14/17 cases), which is the first-line systemic therapy in current guidelines. While this lowered top-1 accuracy against a diverse ground truth, it reflects a safe and guideline-adherent baseline. Importantly, when expanding the evaluation to top-3 accuracy, the system achieved a remarkable 95.8% success rate across all categories. This indicates that even when the model’s primary recommendation differs from the specific clinical choice, the correct treatment is almost invariably captured within its top candidates.

To summarize, unlike “black-box” end-to-end models that might hallucinate treatments based on statistical correlations, our reasoning specialist grounds its decisions in explicit textual evidence. The high top-3 accuracy confirms that the system effectively narrows the search space to clinically valid options. For complex cases like IH, the system serves as a “safety net”, proposing the standard-of-care (e.g., oral medication) while allowing the clinician to refine the final choice based on specific patient nuance.

5. Discussion

Our study provides a critical reassessment of the application of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) in specialized medical domains. The comparative evaluation in

Section 4.1 revealed that current “generalist” state-of-the-art models, despite their massive parameter counts, struggle significantly with the fine-grained visual classification of VAs, achieving a diagnostic accuracy of only roughly 58%. More concerning was the “reasoning gap”, where treatment recommendation accuracy plummeted to 16.3% due to a lack of domain-specific grounding. In contrast, our proposed HevaDx system demonstrates that a modular, agentic architecture is superior for this task. By decoupling perception from reasoning, HevaDx achieved a top-3 diagnostic accuracy of 94.8% and a treatment accuracy of 83.3%. This validates our core hypothesis: specialized visual encoders (DINOv2) are necessary to resolve clinical mimicry, while Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is essential for bridging the gap between identifying a lesion and prescribing an evidence-based therapy.

Furthermore, our ablation studies underscore that high-quality data curation is as critical as model architecture. The dramatic improvement in F1-scores across all disease categories—particularly for morphologically complex subtypes like Verrucous Hemangioma (improvement from 0.21 to 0.64)—confirms that rigorous Region of Interest (ROI) annotation and class balancing are prerequisites for handling long-tail medical distributions. Beyond accuracy, the qualitative analysis of the reasoning specialist highlights the system’s value as a transparent clinical assistant. While the model exhibited lower top-1 agreement in complex, multimodal treatment scenarios like Infantile Hemangioma (35.3%), its high top-3 accuracy and strict adherence to first-line guidelines (e.g., oral medication) indicate that it functions effectively as a safety net. Unlike opaque end-to-end models, HevaDx provides verifiable reasoning chains grounded in established guidelines, fostering the trust required for clinical collaboration.

Despite these promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, while HevaDx has significantly improved diagnostic accuracy compared to baseline AI models, it still lags behind the nuanced diagnostic and treatment planning capabilities of experienced board-certified clinicians, particularly in handling edge cases. Second, our experiments were conducted retrospectively on a curated dataset; the system has not yet been deployed in a real-world clinical setting. Prospective testing is required to validate its efficacy in live workflows, which also necessitates a thorough discussion of the ethical implications surrounding AI-assisted diagnosis and liability. Third, the current iteration covers only six major disease categories. For the system to be comprehensively useful, further continuous data collection and model iteration are needed to encompass the full spectrum of vascular anomalies. In summary, this work proposes a complete methodology for AI-assisted clinical diagnosis—from dataset construction to data cleaning and agentic systems development—providing valuable empirical insights and an effective framework for future research in medical AI.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we addressed the critical gap between general-purpose AI capabilities and the specialized requirements of diagnosing vascular anomalies. Our comprehensive evaluation revealed that while large foundation models possess strong general reasoning, they falter in the specific tasks of distinguishing VA subtypes and formulating safety-critical treatment plans. We proposed HevaDx, a novel agentic system that decouples perception and reasoning to overcome these bottlenecks. By combining a dedicated visual encoder with a guideline-retrieving language model, our system achieves state-of-the-art performance while ensuring the transparency and interpretability essential for clinical adoption. Furthermore, our experimental results demonstrate that a rigorous pipeline for dataset construction and data cleaning is essential for medical diagnostic tasks. Ultimately, HevaDx demonstrates that a modular, evidence-based approach is superior to "black-box" end-to-end paradigms for complex medical decision-making, paving the way for trustworthy AI assistants in dermatology and plastic surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yize Zhang, Yajing Qiu and Xiaoxi Lin; methodology, Yize Zhang; software, Yize Zhang; validation, Yize Zhang and Yajing Qiu; formal analysis, Yize Zhang and Yajing Qiu; investigation, Yize Zhang, Yajing Qiu and Xiaoxi Lin; resources, Yize Zhang and Yajing Qiu; data curation, Yize Zhang and Yajing Qiu; writing—original draft preparation, Yize Zhang; writing—review and editing, Yize Zhang, Yajing Qiu and Xiaoxi Lin; visualization, Yize Zhang; supervision, Yize Zhang, Yajing Qiu and Xiaoxi Lin; project administration, Yize Zhang, Yajing Qiu and Xiaoxi Lin; funding acquisition, Xiaoxi Lin. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the fund of the Clinical Cohort of complex vascular malformations and related syndromes for Genetics-Based Targeted Therapies from the Top Priority Research Center of Shanghai——Plastic Surgery Research Center, Shanghai (No. 2023ZZ02023), and the AI for Science Seed Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 2025AI4S-HY03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (protocol code SH9H-2019-T164-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Clinical Cohort of complex vascular malformations and related syndromes for Genetics-Based Targeted Therapies from the Top Priority Research Center of Shanghai——Plastic Surgery Research Center, Shanghai (No. 2023ZZ02023), and the AI for Science Seed Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 2025AI4S-HY03). We thank all the reviewers for their valuable feedback throughout the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VA |

Vascular Anomaly |

| PWS |

Port-wine Stain |

| IH |

Infantile Hemangioma |

| VM |

Venous Malformation |

| VH |

Verrucous Hemangioma |

| VVM |

Verrucous Venous Malformation |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| MLLM |

Multimodal Large Language Model |

| RAG |

Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| SOTA |

State-of-the-art |

| ICL |

In-Context Learning |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

References

- Kanada, K.N.; Merin, M.R.; Munden, A.; Friedlander, S.F. A prospective study of cutaneous findings in newborns in the United States: correlation with race, ethnicity, and gestational status using updated classification and nomenclature. The Journal of pediatrics 2012, 161, 240–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.B.; Richter, G.T. Vascular Anomalies. Clinics in perinatology 2018, 45, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queisser, A.; Seront, E.; Boon, L.M.; Vikkula, M. Genetic Basis and Therapies for Vascular Anomalies. Circulation research 2021, 129, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunimoto, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Jinnin, M. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies and Molecular Biology. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (CSSVA); C.S. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hemangiomas and vascular malformations (2024 edition). Journal of Tissue Engineering and Reconstructive Surgery 2024, 20, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sebaratnam, D.F.; Rodríguez Bandera, A.L.; Wong, L.C.F.; Wargon, O. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: Management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2021, 85, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X. Pathogenesis of Port-Wine Stains: Directions for Future Therapies. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, A.K.; Alomari, A.I. Management of venous malformations. Clinics in plastic surgery 2011, 38, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.H.; Ma, C.Y.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, M.; Gu, P.; Xia, S.; Li, W.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Multimodal Large Language Models: Performance and Challenges Across Different Tasks. ArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Gan, W.; Chen, Z.; Wan, S.; Yu, P.S. Multimodal large language models: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). IEEE, 2023; pp. 2247–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.J.; Kan, S.X.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Gu, Y.X.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y.L. Multimodal large language models in medical research and clinical practice: Development, applications, challenges and future. Neurocomputing 2026, 660, 131817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Tang, H. Multimodal Large Language Models for Medicine: A Comprehensive Survey. ArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Wu, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. An Agentic System for Rare Disease Diagnosis with Traceable Reasoning. ArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y. A Survey of LLM-based Agents in Medicine: How far are we from Baymax? In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. ArXiv 2022. abs/2203.02155. [Google Scholar]

- van de Ven, G.M.; Soures, N.; Kudithipudi, D. Continual Learning and Catastrophic Forgetting. ArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ding, L.; Fang, M.; Tao, D. Revisiting Catastrophic Forgetting in Large Language Model Tuning. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, 2024, 4297–4308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Peng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Lu, C. CauSight: Learning to Supersense for Visual Causal Discovery. ArXiv 2025. abs/2512.01827. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. ArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.V.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision. ArXiv 2023. abs/2304.07193. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F.; Dong, G.; et al. Qwen2.5 Technical Report. ArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Kuttler, H.; Lewis, M.; tau Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. ArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, M.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. ArXiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.C.; Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Bei, Y.Q.; Zou, H.P.; Luo, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Towards Agentic RAG with Deep Reasoning: A Survey of RAG-Reasoning Systems in LLMs. ArXiv 2025. abs/2507.09477. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-VL Technical Report. ArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.T.A.; Yin, B.; Xing, B.; Qu, B.; Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Du, C.; Wei, C.; Wang, C.; et al. Kimi-VL Technical Report. ArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. ArXiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sellergren, A.; Kazemzadeh, S.; Jaroensri, T.; Kiraly, A.P.; Traverse, M.; Kohlberger, T.; Xu, S.; Jamil, F.; Hughes, C.; Lau, C.; et al. MedGemma Technical Report. ArXiv 2025. abs/2507.05201. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wong, C.; Zhang, S.; Usuyama, N.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Naumann, T.; Poon, H.; Gao, J. LLaVA-Med: Training a Large Language-and-Vision Assistant for Biomedicine in One Day. ArXiv 2023. abs/2306.00890. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S.C.H. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Dai, D.; Zheng, C.; Wu, Z.; Chang, B.; Sun, X.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Sui, Z. A Survey on In-context Learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. ArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Gui, L.; He, Y. The Mystery of In-Context Learning: A Comprehensive Survey on Interpretation and Analysis. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alansari, A.; Luqman, H. Large Language Models Hallucination: A Comprehensive Survey. ArXiv 2025. abs/2510.06265. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Enhancing LLM Factual Accuracy with RAG to Counter Hallucinations: A Case Study on Domain-Specific Queries in Private Knowledge-Bases. ArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Fixing Weight Decay Regularization in Adam. ArXiv 2017. abs/1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. CoRR 2014. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

Low-frequency categories (less than 25 cases) were grouped into an “Rare Types” category. |

| 2 |

The selected range and open-source nature enable local deployment on standard enterprise-grade hardware (e.g., single NVIDIA A100 or RTX 4090), facilitating data privacy compliance within hospital intranets. |

| 3 |

The reasoning specialist receives textual diagnostic results from the visual specialist. |

| 4 |

Note that due to data balancing ( Section 3.1), we have narrowed down the range of diseases that need to be identified for the diagnostic task. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).