1. Introduction

Skin cancer represents one of the most common malignancies worldwide, with melanoma being the most lethal form of skin cancer [

1]. Early detection and accurate diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions are crucial for optimal patient outcomes, yet diagnostic accuracy varies significantly among healthcare providers [

2]. The Health Resources and Services Administration predicts an increase in the gap between the supply and demand of full-time dermatologists in the United States over the next 12 years [

3]. A recent study has shown that, in a 25-year period starting in 1991, dermatologist visit rates have increased by 68%, and dermatologist visit length has increased by 39% [

4]. Currently, dermatologic complaints account for 20% of all physician visits in the United States [

5]. The shortage of dermatologists, particularly in underserved areas, has created a need for innovative patient-facing diagnostic tools that can assist in the evaluation of concerning skin lesions. [

6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising technology to augment clinical decision-making in dermatology. Traditional AI approaches in dermatology have primarily focused on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained on large datasets of skin lesion images [

7,

8,

9]. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated excellent performance for well-defined lesion classification tasks, they may be limited in conditions requiring integration of clinical context, patient history, and morphological patterns—such as inflammatory skin conditions and complex dermatoses where visual appearance alone is insufficient for accurate diagnosis [

10,

11,

12,

13]

Recent advancements in generative AI and multimodal large language models (LLMs) have introduced new possibilities for clinical applications. Unlike traditional image-only models such as CNNs, multimodal LLMs can process and integrate diverse data types, including clinical images, patient history, and contextual information, to potentially provide more comprehensive diagnostic assessments. Multimodal large language models (LLMs) such as SkinGPT-4 and PanDerm have demonstrated more comprehensive diagnostic reasoning than unimodal CNNs, which are limited to visual pattern recognition alone [

14,

15,

16]. Broader medical literature also highlights that multimodal generative AI models can generate narrative reports, synthesize patient histories, and provide tailored recommendations, which addresses the need for integration of clinical context in complex diagnostic scenarios [

17,

18,

19,

20].

The development of domain-specific AI models trained on specialized medical data represents a significant evolution from general-purpose AI systems. DermFlow, a proprietary dermatology-trained multimodal LLM, was specifically designed to address the unique challenges of dermatologic diagnosis by incorporating extensive dermatology-specific training data that can both cover a wide range of dermatologic conditions and be integrated end-to-end into clinical workflow.

This study aims to evaluate the diagnostic performance of DermFlow in specifically assessing pigmented skin lesions compared to both clinician assessments and a general-purpose multimodal LLM, Claude Sonnet 4 (Claude) provided only with images. By analyzing real-world clinical cases with histopathologic confirmation, we seek to determine the potential utility of specialized AI models in dermatologic practice. Our principal findings demonstrate that intelligent history intake dramatically improves AI diagnostic accuracy, with potential implications for clinical decision support in dermatology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

This retrospective study was conducted at Indiana University Health clinics, including Eskenazi Health and IU Health, from February 2023 to May 2025.

2.2. Participants

Images were included in the study if they: (1) were from patients seen at Indiana University Health or affiliated clinics between February 2023 and May 2025 with pigmented skin lesions documented in the electronic medical record (EMR); (2) were taken prior to initial biopsy; (3) were associated with a clinician’s pre-biopsy diagnosis; and (4) had histopathological confirmation.

Images were excluded from the study if they: (1) were of lesions that were not visibly pigmented; (2) were taken after the initial biopsy; (3) were obstructed, of low-quality, or blurry; or (4) did not include images where the lesion was readily apparent.

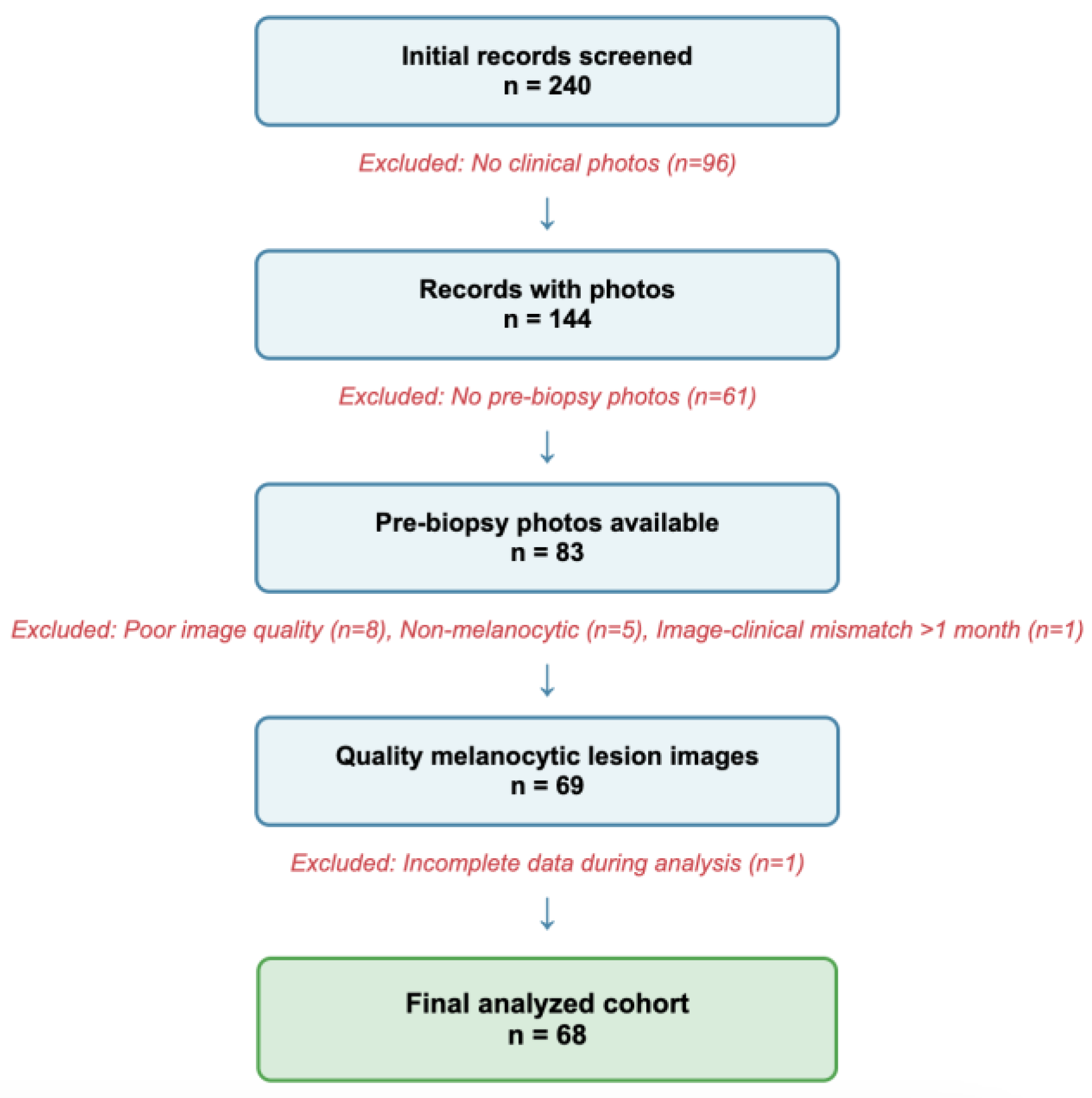

A flowchart of the rigorous screening process is displayed in

Figure 1.

2.3. Data Collection

Clinical data and clinical images were extracted from the EMR using a standardized data collection form and entered into a secure REDCap database. Variables collected included demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), clinical history (personal history of skin cancer, immunosuppressive conditions, family history, etc.), lesion characteristics (location, morphology, duration, changes), clinician differential diagnoses, and histopathologic diagnoses.

2.4. AI Model Evaluation

De-identified patient histories and clinical images were input into DermFlow (Delaware, USA), a dermatology-trained multimodal LLM specifically designed for dermatologic applications. Clinical images only were input into Claude 4 Sonnet, a general-purpose multimodal LLM that serves as the foundation for DermFlow.

Each model was instructed to output a maximum of 4 differential diagnoses, ranked by likelihood, that were determined to have >85% likelihood. In addition, each model was allowed to provide an additional 1-2 diagnoses that are potentially life-threatening, highly morbid, rapidly progressive, or with potential systemic or other organ involvement (safety diagnoses).

2.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was diagnostic accuracy for correctly categorizing lesions as benign, atypical, or malignant, with histopathologic diagnosis serving as the gold standard. Two levels of accuracy were assessed: whether the #1 ranked diagnosis correctly categorized the lesion as benign, atypical, or malignant (top diagnosis accuracy); and whether any diagnosis in the differential correctly categorized the lesion type (any-diagnosis accuracy). This approach focuses on clinically relevant categorization rather than exact specific diagnosis matching, as the critical clinical decision is distinguishing malignant and atypical lesions from benign lesions.

Secondary outcomes included decision-to-biopsy rates and agreement between AI models and clinicians. Decision-to-biopsy recommendation was determined if the AI model’s differential diagnosis included a diagnosis in the atypical or malignant categories. The clinician’s decision-to-biopsy was 100%, as decision to biopsy was a requirement for inclusion of an image in this study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 31.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, with categorical variables presented as frequencies and percentages. For diagnostic performance metrics, proportions with 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Wilson score method, which provides more accurate intervals for proportions near the boundaries (0% or 100%). Statistical significance for comparing diagnostic accuracy proportions between methods was assessed using two-proportion z-tests. Inter-rater agreement was evaluated using Cohen's kappa coefficient (κ), with interpretation according to Landis and Koch criteria: κ < 0.20 (slight), 0.20-0.40 (fair), 0.40-0.60 (moderate), 0.60-0.80 (substantial), and > 0.80 (almost perfect). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Clinical Context

This study analyzed a clinically enriched cohort of 68 pigmented lesions that warranted both clinical photography and histopathologic evaluation due to clinical concern for malignancy (

Table 1). This represents the population where AI diagnostic assistance would be most clinically valuable - lesions with sufficient clinical suspicion to merit biopsy.

A total of 68 pigmented lesions were analyzed. 49 lesions (72.1%) were histopathologically confirmed as malignant melanoma, 15 lesions (22.1%) classified as atypical, and 4 lesions (5.9%) classified as benign. 39 lesions (57.4%) were indicated with a clinical marker, such as a surgical marking pen, in preparation for biopsy or excision.

3.2. Diagnostic Performance

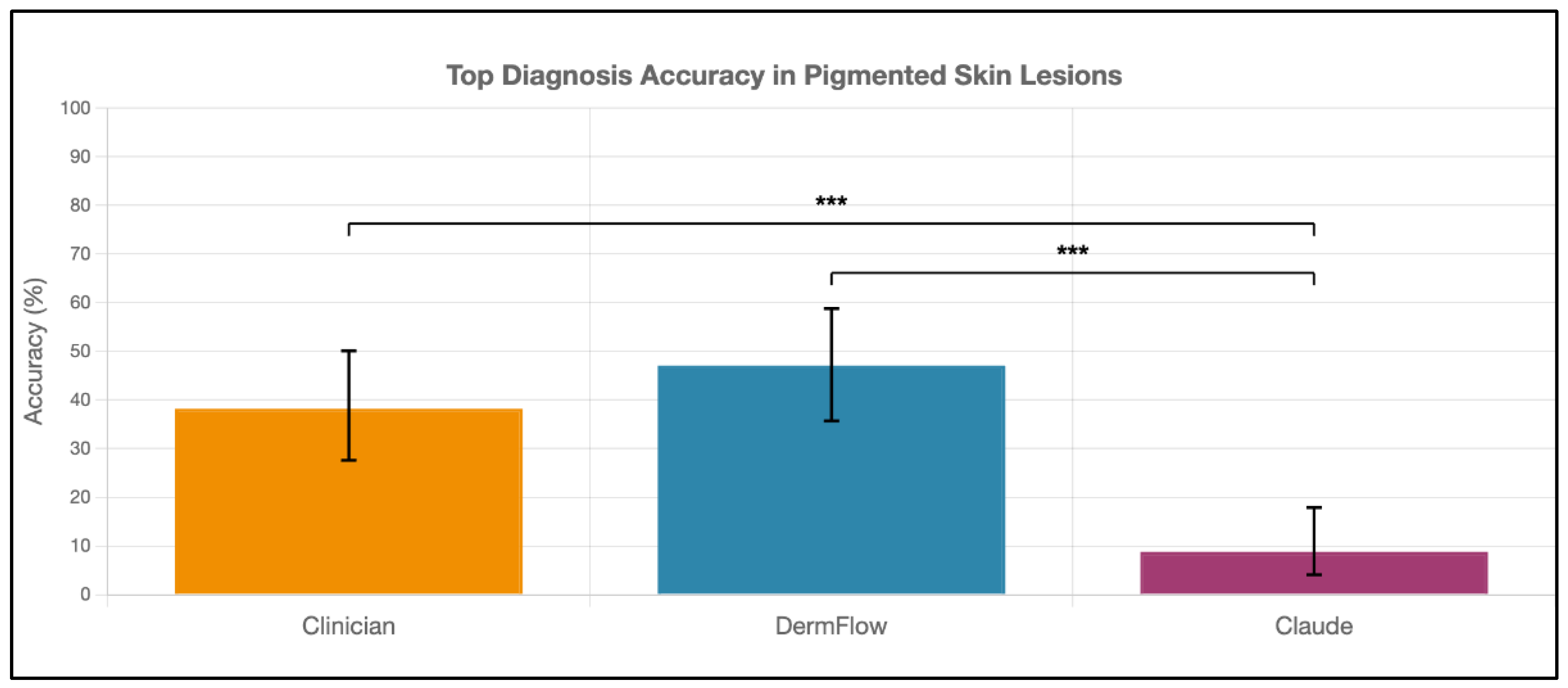

DermFlow demonstrated superior or similar diagnostic accuracy compared to both Claude and clinician assessments across multiple metrics. For top diagnosis accuracy, DermFlow achieved 47.1% (95% CI: 34.8-59.7%) compared to clinicians at 38.2% (95% CI: 26.7-50.8%) and Claude at 8.8% (95% CI: 3.2-17.6%) (

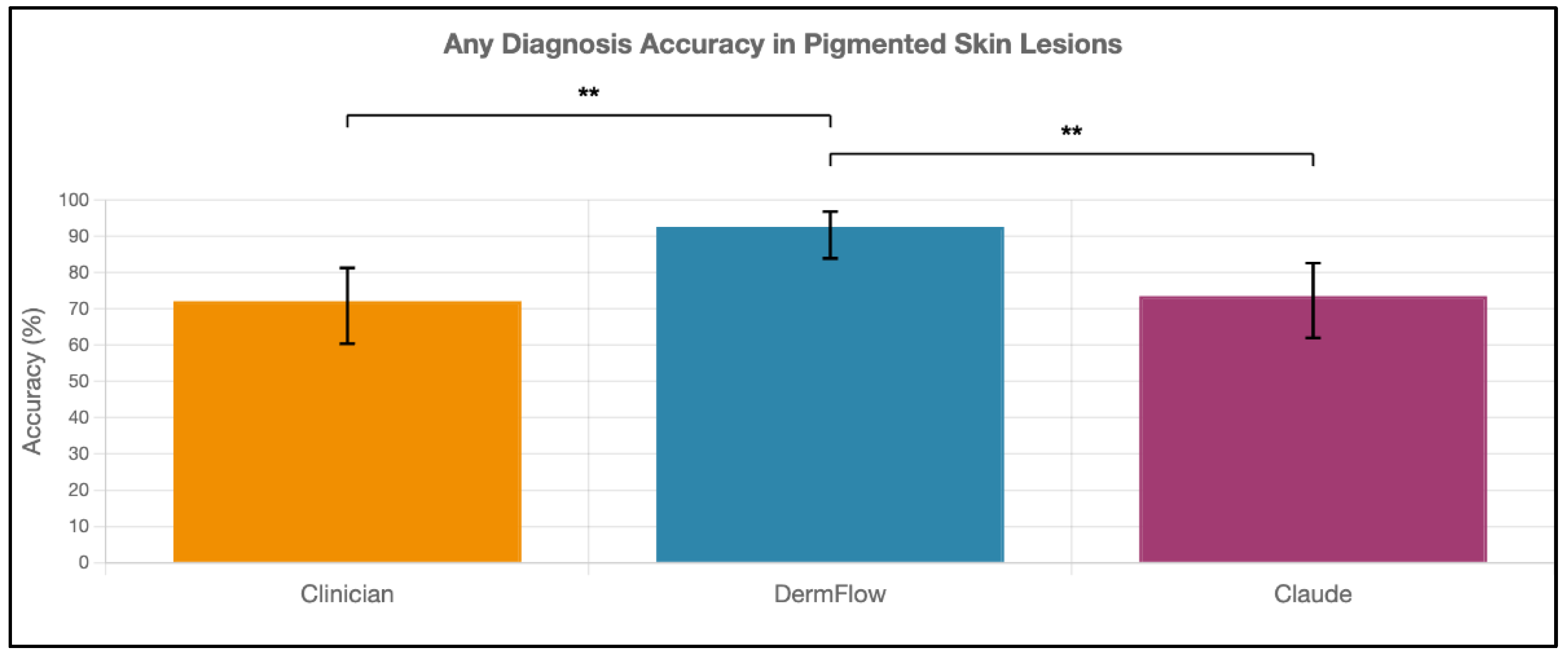

Figure 2). When considering any diagnosis within the differential, DermFlow's performance increased dramatically to 92.6% (95% CI: 84.3-97.1%) outperforming both clinicians at 72.1% (95% CI: 60.8-81.9%) and Claude at 73.5% (95% CI: 61.8-83.4%) (

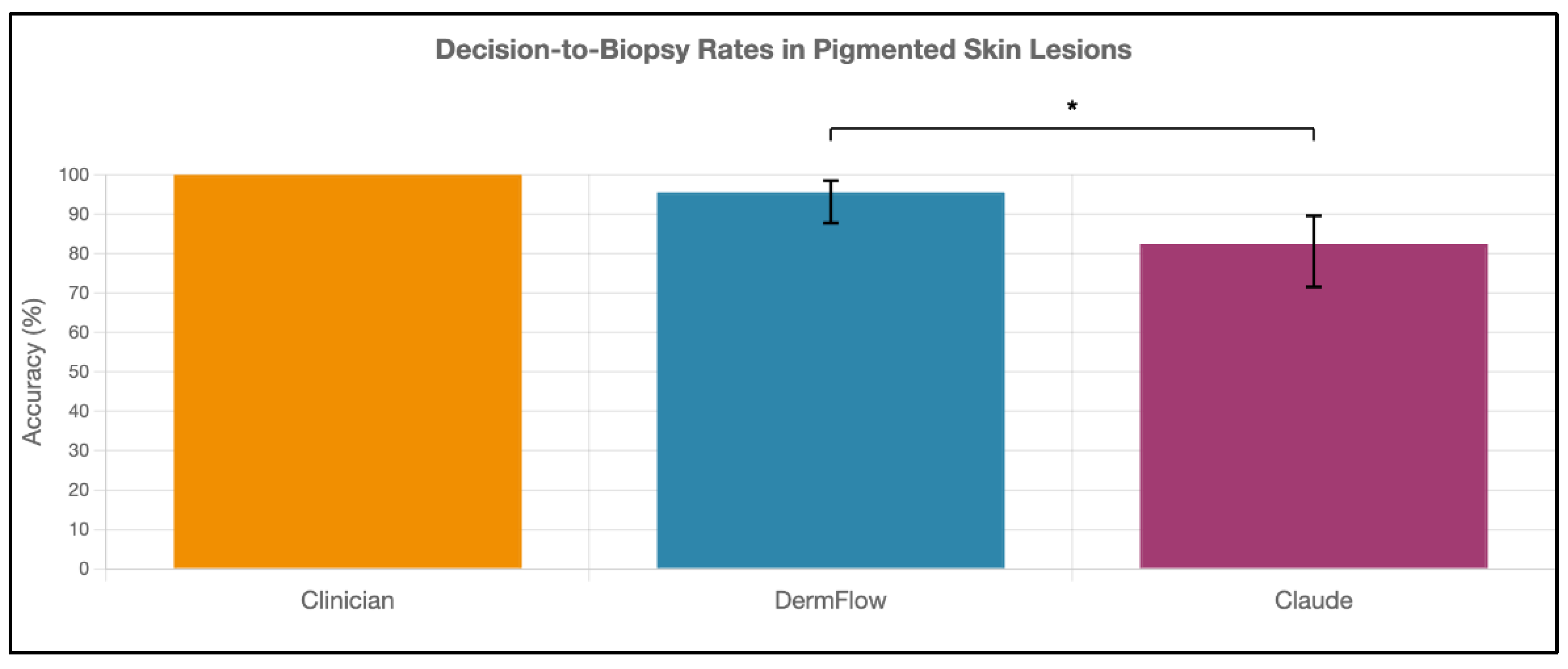

Figure 3). For decision-to-biopsy rates in this high-suspicion cohort, clinicians recommended biopsy for 100% of cases (as this was a requirement for inclusion into the study), DermFlow recommended biopsy for 95.6% (95% CI: 89.4-98.5%) of cases, and Claude recommended biopsy for 82.4% (95% CI: 70.2-90.5%) of cases (

Figure 4).

The diagnostic performance metrics sensitivity and PPV were calculated in

Table 2. However, the small sample sizes in atypical and benign lesions prevent meaningful analysis of specificity and NPV.

3.3. Inter-Rater Agreement Analysis

Agreement between AI models and clinicians was assessed using Cohen's kappa coefficient across multiple diagnostic measures (

Table 3). For top diagnosis accuracy, DermFlow showed slight agreement with clinicians (κ = 0.045, 52.9% observed agreement). Agreement between DermFlow and Claude 4 was poor (κ = -0.050, 50.0% observed agreement), indicating performance worse than chance agreement. The highest agreement was observed between clinicians and Claude 4 (κ = 0.196, 67.6% observed agreement), though this remained in the slight agreement range.

Any-diagnosis accuracy agreement patterns could not be assessment because most differential diagnoses produced by clinicians, DermFlow, and Claude included 2 or more diagnostic categories.

For biopsy recommendations, meaningful agreement analysis was only possible between the two AI models since clinicians recommended biopsy for 100% of cases by study design. DermFlow and Claude 4 showed poor agreement for biopsy recommendations (κ = -0.076, 77.9% observed agreement), despite both models having high individual biopsy recommendation rates.

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

Performance varied across different patient and lesion characteristics for both top diagnosis accuracy (

Table 4) and any-diagnosis accuracy (

Table 5). DermFlow maintained superior performance compared to Claude across all subgroups analyzed.

Notable findings include superior performance for head lesions across all methods, with clinicians showing particularly strong performance (top diagnosis accuracy = 71.4%, any-diagnosis accuracy = 92.0%) in this anatomical region. Additionally, the presence of a clinical marker in the analyzed image resulted in higher diagnostic accuracy, although increasing the sample size will be needed to detect significant changes.

3.4.1. Sex-Based Analysis

DermFlow maintained consistent performance across sex, with minimal variation in both top diagnosis accuracy (male: 51.7%, female: 43.6%) and any-diagnosis accuracy (male: 93.1%, female: 92.3%). Clinicians and Claude showed similar consistency across sex groups, suggesting that sex does not significantly influence diagnostic performance for any of the evaluated methods.

3.4.2. Anatomical Location Analysis

Head and face lesions (n=14) demonstrated superior performance across all methods for both accuracy metrics. For top diagnosis accuracy, clinicians achieved their highest performance on head/face lesions (71.4%), followed by DermFlow (64.3%) and Claude (14.3%). This pattern was even more pronounced for any-diagnosis accuracy, where DermFlow achieved perfect performance (100.0%) on head/face lesions, with clinicians (92.9%) and Claude 4 (85.7%) also showing their best regional performance.

Lower extremity lesions (n=19) proved most challenging across all methods, with DermFlow showing its lowest top diagnosis accuracy (21.1%) in this region, though it maintained strong any-diagnosis accuracy (89.5%). This anatomical variation may reflect both imaging challenges in lower extremity photography and the clinical complexity of pigmented lesions in these locations.

3.4.3. Clinical Marker Analysis

The presence of clinical markers in images appeared to benefit AI performance more than clinical assessment. DermFlow showed improved performance when markers were present for both top diagnosis accuracy (53.8% vs 37.9%) and any-diagnosis accuracy (94.9% vs 89.7%). Clinician performance remained virtually unchanged regardless of marker presence (38.5% vs 37.9% for top diagnosis; 74.4% vs 69.0% for any diagnosis). This finding is expected, as the pre-operative diagnosis is typically made prior to addition of a clinical marker.

3.4.4. Consistency Across Subgroups

DermFlow demonstrated remarkably consistent any-diagnosis accuracy across all analyzed subgroups (range: 87.5% to 100.0%), reinforcing its potential clinical utility across diverse patient populations and lesion characteristics. This consistency is particularly important for clinical implementation, as it suggests reliable performance regardless of patient demographics or lesion location.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

Our findings provide compelling evidence for the critical importance of intelligent clinical history integration in AI-assisted dermatologic diagnosis. The dramatic 5-fold difference in top diagnosis accuracy between DermFlow (47.1%) and Claude 4 Sonnet (8.8%) demonstrates that the ability to systematically gather and integrate clinical context represents a fundamental advancement over image-only AI approaches, regardless of the underlying model sophistication. This interpretation is consistent with previous research that found higher diagnostic accuracy in multimodal AI models compared to unimodal models [

18,

21,

22,

23].

While landmark studies by Esteva et al. and Haenssle et al. demonstrated impressive performance with image-only CNN approaches that excel at visual pattern recognition [

8,

9], our results suggest that diagnostic accuracy may be significantly enhanced when AI systems can systematically integrate clinical context alongside image analysis, addressing a capability gap that purely image-based systems cannot fill regardless of their visual analysis sophistication.

Perhaps most clinically significant is DermFlow's exceptional any-diagnosis accuracy of 92.6%, which substantially exceeded both clinicians (72.1%, p < 0.01) and Claude 4 (73.5%, p < 0.01). This metric reflects the model's ability to include the correct lesion categorization somewhere within its differential diagnosis, even when not ranked as the top possibility. This comprehensive diagnostic reasoning mirrors how experienced dermatologists approach challenging cases and provides substantial clinical value, as appropriate management can be initiated when the correct diagnosis category is recognized within the differential [

14,

15,

24].

DermFlow's exceptional any-diagnosis accuracy of 92.6% represents a paradigm shift from previous AI dermatology research, which has been predominantly focused on image classification without clinical context integration [

7,

8,

9,

25]. This finding suggests that AI systems capable of intelligent history-taking and clinical reasoning integration can achieve performance levels that approach or exceed the comprehensive diagnostic reasoning that characterizes expert clinical practice.

4.2. Clinical Context Integration: A Fundamental Advance

The superior performance of DermFlow compared to Claude supports our primary working hypothesis that systematic clinical context integration would enhance diagnostic accuracy beyond what is achievable with image analysis alone. The magnitude of improvement suggests several important insights about the nature of dermatologic diagnosis and the role of clinical reasoning in expert performance.

Importantly, our study design allows us to isolate the specific contribution of clinical context integration, as both systems utilize sophisticated multimodal AI capabilities for image analysis. The performance difference therefore reflects the value added by systematic history-taking and clinical reasoning integration rather than differences in underlying AI sophistication or training datasets.

This finding aligns with established principles from cognitive psychology research demonstrating that expert clinical reasoning relies heavily on pattern recognition combined with systematic integration of contextual information [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].The ability of DermFlow to systematically gather and integrate clinical history—including lesion duration, changes over time, family history, and patient risk factors—mirrors the comprehensive assessment approach that characterizes expert dermatologic practice.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice and Diagnostic Workflows

These results have significant implications for clinical practice that extend beyond dermatology to broader questions of AI integration in clinical diagnosis. The demonstrated value of systematic clinical context integration suggests potential applications that could address current challenges in healthcare delivery.

4.3.1. Systematic History-Taking Enhancement

DermFlow's intelligent history-taking capabilities could serve as a clinical decision support tool that ensures comprehensive data collection even in busy clinical environments. Unlike human clinicians, who may inadvertently omit important history elements due to time constraints or cognitive load, AI systems can systematically ensure that all relevant clinical context is gathered and appropriately weighted in diagnostic reasoning.

4.3.2. Addressing Geographic and Expertise Disparities

The superior performance of AI-assisted diagnosis with intelligent history-taking suggests potential for extending expert-level diagnostic reasoning to settings with limited dermatologic expertise. Primary care providers could leverage such systems to ensure comprehensive assessment of concerning lesions, potentially reducing diagnostic delays and improving triage decisions.

4.4. Limitations

There are limitations to this study. Firstly, the high prevalence of malignancy in our cohort (72.1% melanoma) reflects selection bias due to the pre-selection of concerning lesions and differs significantly from typical dermatology screening populations where melanoma prevalence is typically 0.1-0.2% [

31,

32]. Given that images and histopathology results of benign, non-concerning pigmented skin lesions are typically not obtained, we were only able to create an enriched dataset that provides a rigorous test of AI performance in challenging diagnostic scenarios where clinical decision-making is most critical. As a result, specificity and NPV could not be calculated. This limitation could be addressed by conducting prospective studies in dermatology clinics, where all or most pigmented skin lesions of concern can be assessed in real clinical practice.

Secondly, the images used in this study were extracted from patient charts. These images were not captured with the intention of analysis of diagnostic accuracy, which differentiates this study from other AI model validation studies and prevents meaningful comparison with these studies [

33,

34,

35].

Thirdly, these results come from academic medical centers in Indiana and may not generalize to other practice settings, depending on notetaking and image-capturing practices by clinicians, other clinical protocols, and specific patient populations.

Fourthly, sample size constraints limit power for subgroup analysis. Only 19 non-malignant cases (15 atypical and 4 benign) severely limit specificity analysis and comparison to malignant cases, and small numbers in some anatomical subgroups (neck n=5) prevents meaningful statistical analysis.

Fifthly, LLMs are known to inherently underperform in diagnosing conditions in which visual cues and patterns are the primary diagnostic determinants, which may explain the overall modest performance levels observed across all methods in this challenging melanoma-heavy cohort, especially in comparison to literature values for the sensitivity of CNNs that suggest outperformance of DermFlow significantly [

36,

37,

38]. However, it is important to note that these CNNs often are restricted to high-quality photographs that may require capture by a clinician, which decreases the models’ utility as a patient-facing tool. Additionally, these validation studies are often conducted with curated images that are captured with the intention of being used for diagnostic validation.

To address these limitations, future studies can include (1) conducting prospective studies in dermatology clinics, where all or most pigmented skin lesions of concern can be assessed in real clinical practice; (2) testing diagnostic accuracy of DermFlow using images and clinical data from other medical institutions outside of Indiana; (3) increasing the sample size to increase power for subgroup analysis; and (4) directly comparing diagnostic accuracy of CNNs and DermFlow using the same image and history dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M., N.J., S.K.Q.; methodology, J.M., N.J., S.K.Q.; N.J.; software, N.J.; validation, J.M., N.J., A.Z., S.K.Q.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, J.M., A.Z.; resources, N.J., data curation, J.M., A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M., N.J., A.Z., S.K.Q.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, J.M., N.J., S.K.Q.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded, in part, with support from the Short-Term Training Program in Biomedical Sciences Grant funded, in part, by T35 HL 110854 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University School of Medicine (IRB #27390, approved May 16, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Given the retrospective nature of the study using de-identified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this research study is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded, in part, with support from the Short-Term Training Program in Biomedical Sciences Grant funded, in part, by T35 HL 110854 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AI

LLM

Claude |

Artificial Intelligence

Large Language Model

Claude 4 Sonnet |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Siegel, R.L., et al., Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin, 2025. 75(1): p. 10-45.

- Carli, P., et al., Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2004. 50(5): p. 683-9. [CrossRef]

- Administration, H.R.S. Health workforce projections. 2025 [cited 2025 July 10]; Available from: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections.

- Conway, J., et al., High Demand: Identification of Dermatology Visit Trends from 1991-2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys. FC20 Dermatology Conference, 2020. 4(6). [CrossRef]

- Statistics, N.C.f.H. Ambulatory Care Use and Physician office visits. 2024 December 12, 2024 [cited 2025 July 10]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm.

- Feng, H., et al., Comparison of Dermatologist Density Between Urban and Rural Counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol, 2018. 154(11): p. 1265-1271. [CrossRef]

- Brinker, T.J., et al., Deep learning outperformed 136 of 157 dermatologists in a head-to-head dermoscopic melanoma image classification task. Eur J Cancer, 2019. 113: p. 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A., et al., Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature, 2017. 542(7639): p. 115-118. [CrossRef]

- Haenssle, H.A., et al., Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol, 2018. 29(8): p. 1836-1842. [CrossRef]

- Haenssle, H.A., et al., Man against machine reloaded: performance of a market-approved convolutional neural network in classifying a broad spectrum of skin lesions in comparison with 96 dermatologists working under less artificial conditions. Ann Oncol, 2020. 31(1): p. 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Haenssle, H.A., et al., Skin lesions of face and scalp - Classification by a market-approved convolutional neural network in comparison with 64 dermatologists. Eur J Cancer, 2021. 144: p. 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S., et al., Assessment of deep neural networks for the diagnosis of benign and malignant skin neoplasms in comparison with dermatologists: A retrospective validation study. PLoS Med, 2020. 17(11): p. e1003381. [CrossRef]

- Schielein, M.C., et al., Outlier detection in dermatology: Performance of different convolutional neural networks for binary classification of inflammatory skin diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2023. 37(5): p. 1071-1079. [CrossRef]

- Luo, N., et al., Artificial intelligence-assisted dermatology diagnosis: From unimodal to multimodal. Comput Biol Med, 2023. 165: p. 107413. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S., et al., A multimodal vision foundation model for clinical dermatology. Nat Med, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., et al., Pre-trained multimodal large language model enhances dermatological diagnosis using SkinGPT-4. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 5649. [CrossRef]

- Meskó, B., The Impact of Multimodal Large Language Models on Health Care's Future. J Med Internet Res, 2023. 25: p. e52865. [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P. and M.P. Lungren, The Current and Future State of AI Interpretation of Medical Images. N Engl J Med, 2023. 388(21): p. 1981-1990. [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.M., et al., Multimodal generative AI for medical image interpretation. Nature, 2025. 639(8056): p. 888-896. [CrossRef]

- Soni, N., et al., A Review of the Opportunities and Challenges with Large Language Models in Radiology: The Road Ahead. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2025. 46(7): p. 1292-1299. [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A., CareAssist GPT improves patient user experience with a patient centered approach to computer aided diagnosis. Sci Rep, 2025. 15(1): p. 22727. [CrossRef]

- Katal, S., B. York, and A. Gholamrezanezhad, AI in radiology: From promise to practice - A guide to effective integration. Eur J Radiol, 2024. 181: p. 111798. [CrossRef]

- Sosna, J., L. Joskowicz, and M. Saban, Navigating the AI Landscape in Medical Imaging: A Critical Analysis of Technologies, Implementation, and Implications. Radiology, 2025. 315(3): p. e240982. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A., et al., Development and Assessment of an Artificial Intelligence-Based Tool for Skin Condition Diagnosis by Primary Care Physicians and Nurse Practitioners in Teledermatology Practices. JAMA Netw Open, 2021. 4(4): p. e217249. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M., et al., Assessment of Accuracy of an Artificial Intelligence Algorithm to Detect Melanoma in Images of Skin Lesions. JAMA Netw Open, 2019. 2(10): p. e1913436. [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.J., et al., Visual perception, cognition, and error in dermatologic diagnosis: Key cognitive principles. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2019. 81(6): p. 1227-1234. [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, E.J., R. Sidlow, and C.J. Ko, Visual perception, cognition, and error in dermatologic diagnosis: Diagnosis and error. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2019. 81(6): p. 1237-1245. [CrossRef]

- Marcum, J.A., An integrated model of clinical reasoning: dual-process theory of cognition and metacognition. J Eval Clin Pract, 2012. 18(5): p. 954-61. [CrossRef]

- Norman, G., et al., Dual process models of clinical reasoning: The central role of knowledge in diagnostic expertise. J Eval Clin Pract, 2024. 30(5): p. 788-796. [CrossRef]

- Norman, G., M. Young, and L. Brooks, Non-analytical models of clinical reasoning: the role of experience. Med Educ, 2007. 41(12): p. 1140-5. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M., et al., Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 6(6): p. Cd012352.

- Waldmann, A., et al., Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol, 2012. 148(8): p. 903-10. [CrossRef]

- Combalia, M., et al., Validation of artificial intelligence prediction models for skin cancer diagnosis using dermoscopy images: the 2019 International Skin Imaging Collaboration Grand Challenge. Lancet Digit Health, 2022. 4(5): p. e330-e339. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.H., et al., Analysis of Artificial Intelligence-Based Approaches Applied to Non-Invasive Imaging for Early Detection of Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel), 2023. 15(19). [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, M., et al., Artificial intelligence in the detection of skin cancer: State of the art. Clin Dermatol, 2024. 42(3): p. 280-295. [CrossRef]

- Collenne, J., et al., Fusion between an Algorithm Based on the Characterization of Melanocytic Lesions' Asymmetry with an Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks for Melanoma Detection. J Invest Dermatol, 2024. 144(7): p. 1600-1607.e2. [CrossRef]

- Maureen Miracle, S., et al., The Role of Artificial Intelligence With Deep Convolutional Neural Network in Screening Melanoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Quasi-Experimental Diagnostic Studies. J Craniofac Surg, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sabir, R. and T. Mehmood, Classification of melanoma skin Cancer based on Image Data Set using different neural networks. Sci Rep, 2024. 14(1): p. 29704. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).