1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Medical imaging is essential in modern medical diagnosis, serving as a key tool for clinicians to assess patient conditions and develop treatment strategies [

1]. With the increasing availability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT), large and complex imaging datasets have been accumulated in clinical practice. The challenge lies in how to efficiently and accurately diagnose these datasets. Traditional imaging diagnosis heavily relies on the experience and expertise of clinicians, which is time-consuming and susceptible to subjective bias and fatigue. To improve diagnostic accuracy and consistency, exploring the integration of artificial intelligence to assist in imaging diagnosis, has become a significant research direction in the field of medical imaging [

2].

1.2. Definition and Development of Large Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) are a type of deep learning-based artificial intelligence model, specializing in natural language processing and generation [

3]. By pre-training on extensive text datasets, LLMs can understand and generate complex natural language text. These models have achieved breakthroughs in areas such as dialogue systems, machine translation, and text generation in recent years [

4]. In the medical field, LLMs show great potential for analyzing, summarizing, and interpreting complex medical literature and clinical reports.

1.3. Research Objectives

Although LLMs excel in natural language processing, they face challenges in the highly specialized field of medical imaging diagnosis, such as incomplete coverage of medical knowledge and the need for improved diagnostic accuracy. To address these issues, this study proposes a medical imaging diagnosis assistance system (LLM-RAG-MID), integrating LLM with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology. This system can dynamically retrieve relevant medical literature, guidelines, and case data in real time, enhancing the coverage of specialized knowledge and the reliability of diagnostic outcomes.

The main contributions of this research are:

First, we developed an LLM-based medical imaging diagnosis assistance system that can automatically identify, analyze, and classify a variety of typical medical imaging lesions, thereby assisting clinicians in making efficient diagnoses.

Second, by incorporating RAG technology, we significantly expanded the system’s medical knowledge coverage, improving the scientific validity and reliability of diagnostic suggestions.

Finally, we validated the system using three clinical cases: ependymoma, low-grade glioma, and cirrhosis with multiple intrahepatic nodules (including regenerative nodules, low-grade dysplastic nodules, and possible early hepatocellular carcinoma). The results show that the system performs well in terms of diagnostic accuracy and consistency, with its conclusions highly aligned with clinical expert assessments, demonstrating substantial application potential.

1.4. Paper Structure

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of the MRI diagnostic features of intraspinal ependymoma, low-grade glioma, and cirrhosis with multiple intrahepatic nodules, while analyzing the traditional imaging diagnosis’s heavy dependence on clinical experience and highlighting its limitations.

Section 3 details the proposed method, explaining the design and implementation of the LLM-based and LLM-RAG-MID system, including aspects such as model training, dataset processing, and the functionalities of the system’s modules.

Section 4 outlines the experimental setup, presenting the experiments conducted on ependymoma, low-grade glioma, and cirrhosis with multiple intrahepatic nodules, and discussing the experimental design, dataset selection, evaluation metrics, and the system’s performance in real-world applications.

Section 5 provides a comprehensive analysis of the experimental results, highlighting the system’s strengths and weaknesses, offering insights into potential improvements, and evaluating the practical value of the research within clinical medical imaging diagnostics. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions and significance of the research, and suggesting potential future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. MRI Diagnosis of Intraspinal Ependymoma

Ependymoma is a central nervous system tumor originating from ependymal cells, commonly found in the intracranial ventricles and spinal canal. intraspinal ependymomas are most frequently observed in adults and are often located within the spinal cord or near the central canal [

5]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is an essential imaging modality for diagnosing intraspinal ependymoma [

6]. Multi-sequence imaging (such as T1WI, T2WI, FLAIR, and contrast-enhanced scans) aids in assessing tumor location, morphology, signal characteristics, and identifying features such as hemorrhage, cystic changes, or calcifications, as well as the involvement of surrounding tissues [

7]. By integrating clinical and imaging findings, this condition can be differentiated from other spinal canal lesions, such as spinal astrocytomas, hemangioblastomas, and ependymal cysts.

2.2. Diagnosis of Low-Grade Gliomas in the Brain

Low-grade gliomas (LGGs) are WHO grade II tumors, often characterized by slow growth and non-specific clinical symptoms [

8]. MRI is a critical tool for diagnosing low-grade gliomas, with sequences like T2WI and FLAIR typically showing high-signal lesions, and contrast-enhanced scans usually lacking significant enhancement. Key observations include the presence of tumor-associated edema, mass effect, and space-occupying lesions [

9]. Differential diagnosis includes distinguishing LGGs from high-grade gliomas, demyelinating lesions, cavernous hemangiomas, and other brain parenchymal lesions.

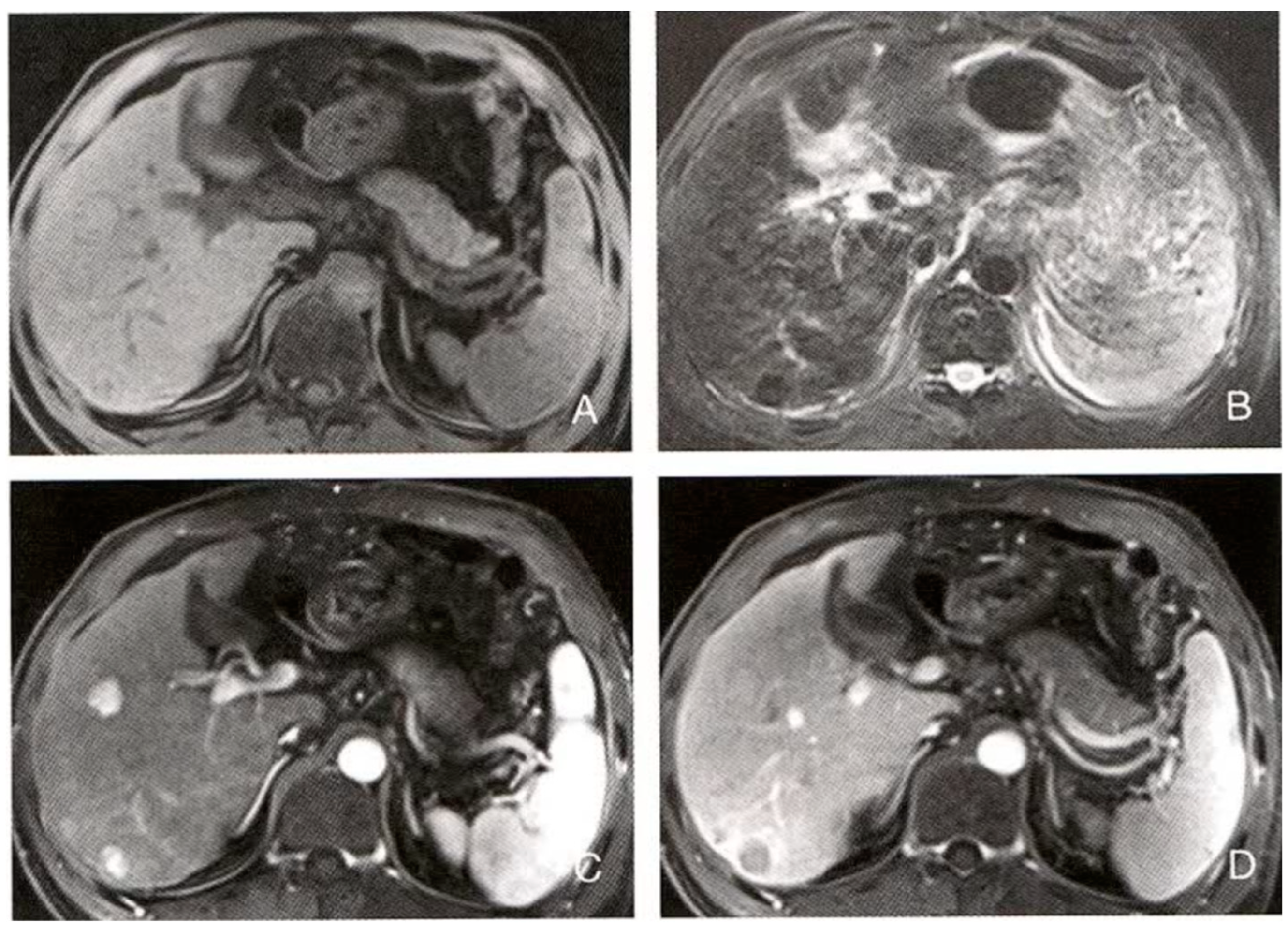

2.3. Diagnosis of Cirrhosis and Multiple Intrahepatic Nodules

Cirrhosis is a pathological condition involving chronic liver damage progressing to fibrosis and the formation of regenerative nodules. In cirrhosis, various nodular lesions appear within the liver, including regenerative nodules, dysplastic nodules, and potential early or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) nodules [

10]. CT/MRI multi-phase contrast-enhanced scans, particularly liver-specific MRI contrast agents, help in differentiating the nature of these nodules [

11,

12]. HCC typically shows significant enhancement in the arterial phase, followed by a “washout” effect in the portal venous or delayed phase. In contrast, regenerative nodules generally lack specific enhancement patterns, while low-grade dysplastic nodules may present features bridging benign lesions and early-stage HCC. Combining patient history, liver function tests, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels further improves diagnostic accuracy [

13].

2.4. Challenges in Traditional Imaging and the Role of LLMs

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for early intervention, optimizing treatment strategies, and improving patient outcomes. However, traditional imaging diagnosis heavily relies on clinician expertise and is susceptible to overlapping imaging features and cognitive biases, which can lead to misdiagnosis or missed diagnoses. Large Language Models (LLMs), by automatically integrating medical literature and clinical knowledge, provide objective support for lesion differential diagnosis, reducing cognitive load and improving accuracy [

14,

15]. While LLM has made strides in report generation and knowledge-based question answering, their application in pure imaging diagnosis for complex lesions such as intraspinal ependymomas, low-grade gliomas, and cirrhosis-related nodules remains unexplored. This study seeks to investigate the potential applications of LLMs in medical imaging diagnosis, offering new perspectives for precise assisted diagnosis.

3. System Design and Implementation

3.1. System Architecture Overview

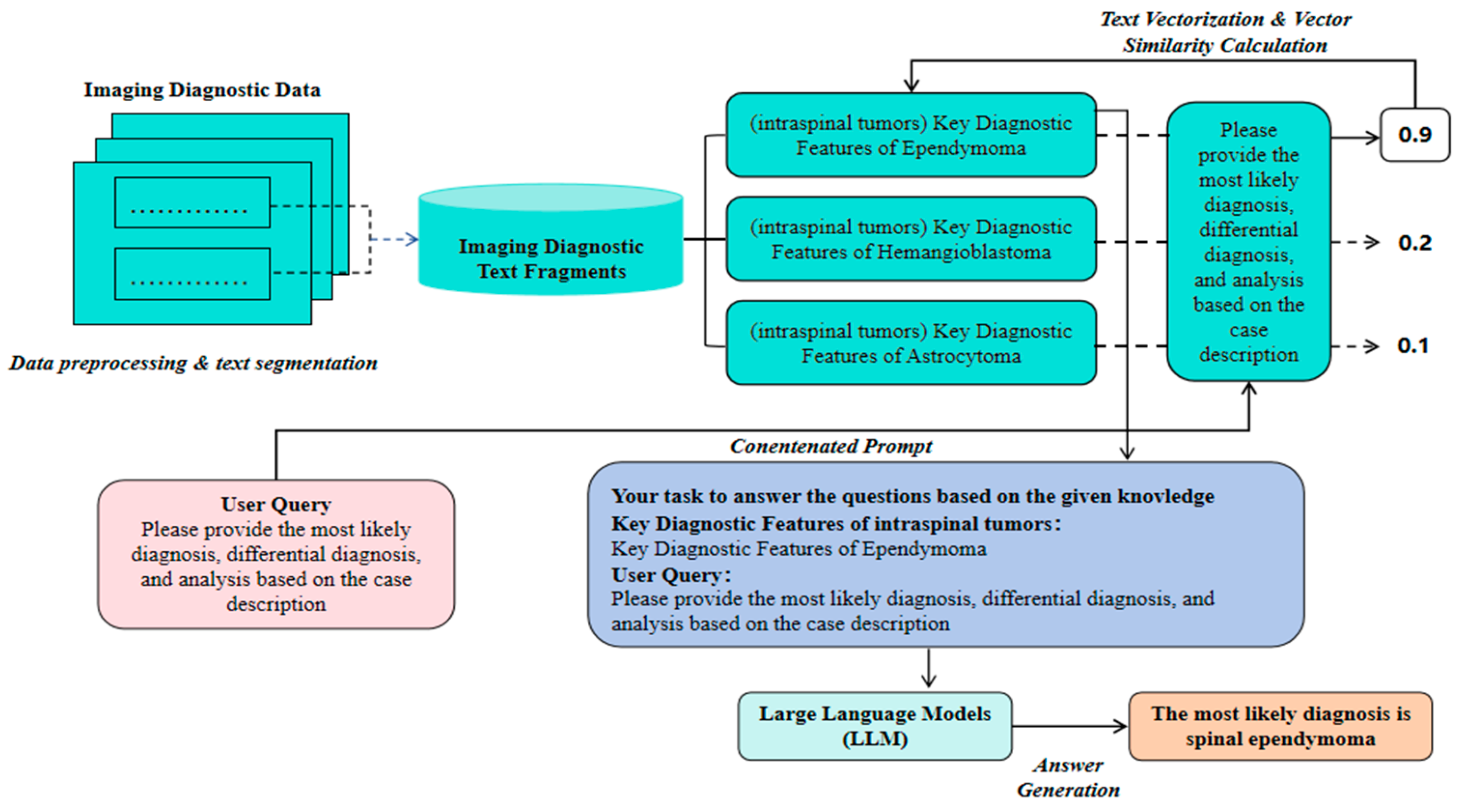

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, medical imaging diagnosis is increasingly integrating advanced technologies such as deep learning and Large Language Models (LLMs) to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of lesion recognition and diagnostic decision-making. As the baseline method in this study, we first evaluate the accuracy of an LLM-based image diagnosis text generation model (i.e., a general LLM parsing medical imaging diagnostic descriptions and independently outputting diagnostic results). This approach is relatively simple and initially demonstrates the LLM’s ability to understand and generate clinical text. However, due to the absence of external knowledge base support, this model fails to adequately cover specialized terminology and complex cases, often resulting in “hallucinations” or missing key information, making it difficult to handle complex features effectively. Overall, purely relying on LLM-based medical imaging diagnosis (referred to hereafter as LLM-MID) lacks sufficient diagnostic accuracy, reasoning, and comprehensive differential diagnosis, as well as clinical feasibility. To address these limitations, we propose a medical imaging diagnosis assistance system that combines LLM and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology (referred to hereafter as LLM-RAG-MID). This system focuses on text data processing and analysis, aiming to automatically identify and classify lesion types in medical imaging reports and generate diagnostic suggestions. LLMs have robust natural language understanding and generation abilities, enabling them to capture semantic and contextual information from large-scale pre-training corpora and produce fluent and reasonably accurate diagnostic text. RAG technology enhances the decision-making process by dynamically retrieving the most up-to-date medical evidence from external knowledge bases and domain literature, thereby reducing “hallucinations” and knowledge gaps in specialized contexts. Combining these technologies allows the system to leverage LLMs’ advantages in semantic reasoning and language generation while benefiting from the external knowledge expansion and refinement provided by RAG, significantly improving diagnostic accuracy in medical imaging reports and better meeting clinical application needs. As shown in

Figure 1, The system architecture comprises several key modules: text preprocessing and segmentation, vectorization and similarity calculation, knowledge fusion, and generation.

3.2. Text Preprocessing and Cutting

Text Preprocessing:

First, relevant text data are extracted from the medical image report, including medical history description, symptom report, and image diagnosis description. In order to ensure the consistency and accuracy of the text data, the preprocessing step includes:

Denoising: removes non-critical information and noisy data from the text, such as patient identifying information or duplicate content.

Standardisation: Harmonisation of medical terminology to ensure that different forms of terminology used by different doctors are treated consistently.

Segmentation: Split the text into separate words or phrases for subsequent analysis and vectorisation.

Text cutting:

The preprocessed text data is cut and divided into several semantic paragraphs or sentence fragments. The purpose of cutting is for better vectorisation and similarity calculation to ensure that the core information of the text can be accurately matched during retrieval.

Let the text data be:

where

indicates a sentence or paragraph in the text.

The set of cut text fragments can be represented as:

where

is a fragment cut from the original text.

3.3. Vectorization and Similarity Calculation

Towards quantification:

For each cut text fragment

, it is converted into a vector representation

using a pre-trained word embedding model such as BERT models [

16] or other similar deep learning models. The formula for vectorisation is as follows:

where,

is the word embedding function provided by the pre-trained model for converting text fragments into high dimensional vectors.

Similarity calculation:

In the inference phase of the system, the input text snippets need to be matched with the text snippets in the pre-stored medical knowledge base. For this purpose, the cosine similarity between the input fragment and each fragment in the knowledge base is calculated. The formula for calculating the cosine similarity is given below:

where

and

denote the vector representation of an input text fragment and a fragment in the knowledge base, respectively,

denotes the dot product operation of a vector, and

denotes the vector’s paradigm.

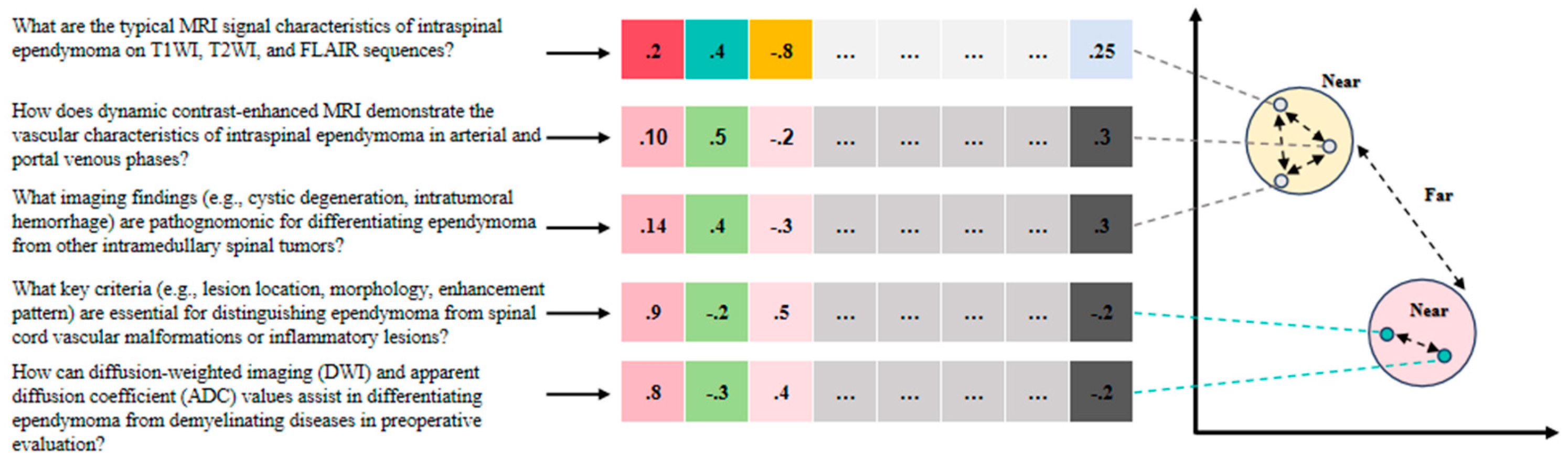

The training process for the vectorization model involves constructing pairs of related and unrelated medical imaging diagnostic queries. For example: “What are the typical MRI signal characteristics of intraspinal ependymoma on T1WI, T2WI, and FLAIR sequences?” and “How does dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrate the vascular characteristics of intraspinal ependymoma in arterial and portal venous phases?” are related queries. “What imaging findings (e.g., cystic degeneration, intratumoral hemorrhage) are pathognomonic for differentiating ependymoma from other intramedullary spinal tumors?” and “How can diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values assist in differentiating ependymoma from demyelinating diseases in preoperative evaluation?” are unrelated queries (

Figure 2). Through similarity calculation, the system can identify the most relevant knowledge fragments to the input text for subsequent knowledge fusion and generation.

3.4. Knowledge Fusion

Retrieval Enhancement Generation:

In the RAG framework, the knowledge fusion module integrates a number of knowledge fragments with the highest degree of similarity to provide contextual support for LLM generation. Assuming that the top most relevant snippets retrieved from the knowledge base are , then these snippets will be fed into the LLM along with the input text snippet for generating the final diagnostic recommendations.

Integration Strategies:

The goal of knowledge fusion is to effectively combine the retrieved medical knowledge with the semantic content of the input text to improve the expertise and accuracy of the generated answers. Fusion strategies include:

The retrieved snippet is spliced directly after the input text to form an extended input. For example, the extended input may be represented as:

where

denotes the expanded input and

denotes the splicing operation.

3.5. Generating Diagnostic Recommendations Using LLM

Overview of the generation process:

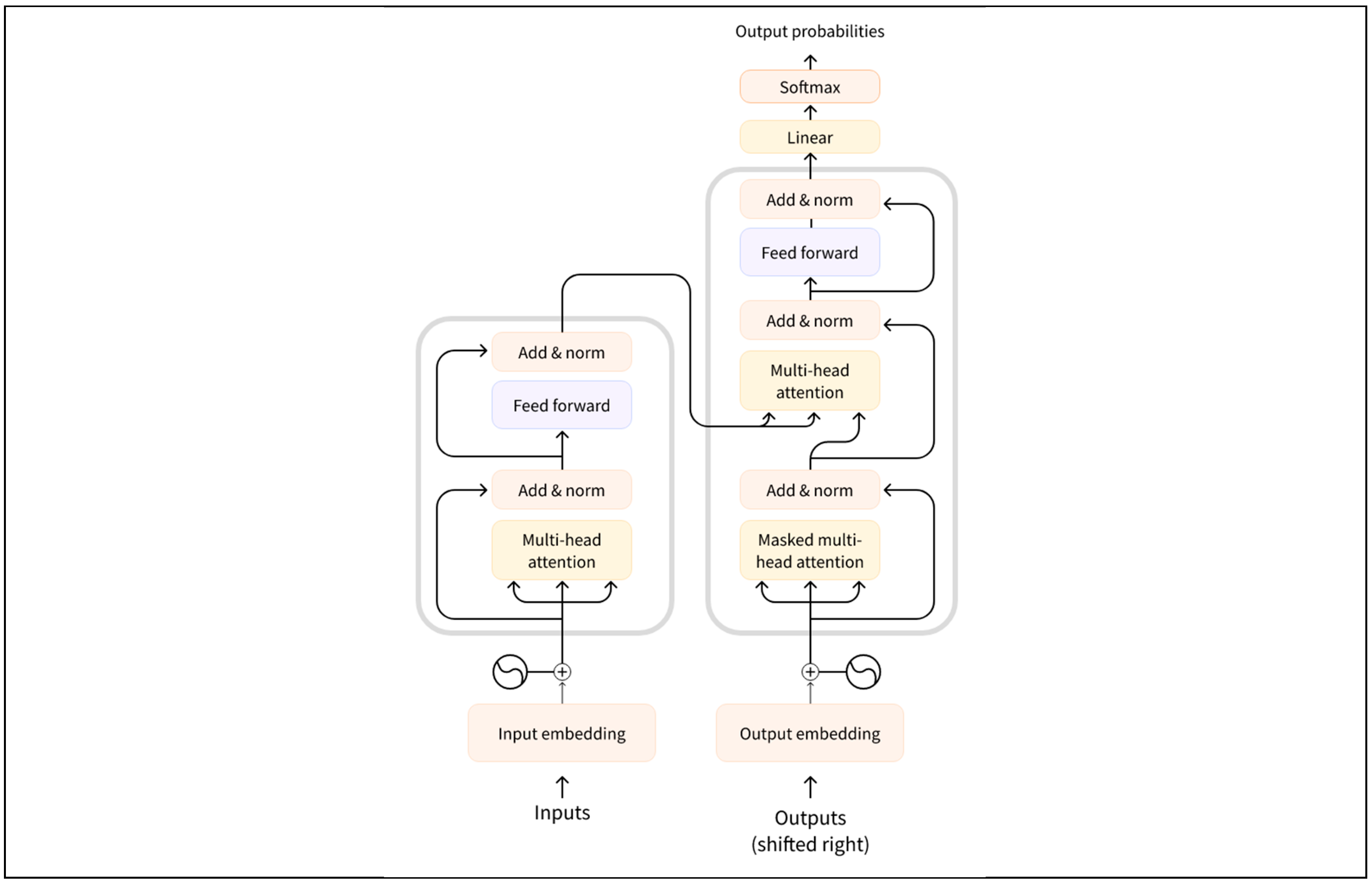

This study utilises a Large Language Model (LLM) based on the Transformer architecture to generate diagnostic suggestions. As shown in

Figure 3, The Transformer model efficiently captures the relationships between elements in a sequence through a self-attention mechanism (self-attention) and generates contextually relevant output. The following section describes the Transformer-based generation process in detail, including how the fused inputs are used to generate diagnostic recommendations.

3.5.1. Key Components of Large Languge Models

The key network architecture of large language models lies in the Transformer. The core components of the Transformer are the self-attention mechanism and the multi-attention mechanism [

17,

18].The input to the model is a set of vector representations and the output is the generated result after multiple layers of encoding and decoding processes.The Transformer architecture consists of the following key components [

19]:

Encoder: encodes the input sequence into a set of hidden vector representations.

Decoder: step-by-step generation of the target sequence based on the output of the encoder and input from the decoder itself (usually previously generated words or tokens).

Self-Attention mechanism (SAM): captures interdependencies between words at different positions in a sequence.

Multi-Head Attention mechanism (MHAM): enhances the model’s ability to capture different relationships in a sequence by computing multiple attention heads in parallel.

3.5.2. Coding Phase

In the encoding stage, the fused input is passed to the encoder part of the Transformer. The encoder converts the input sequence into a set of hidden states , the

Each hidden state

is calculated by the following formula:

where,

denotes the contextual information related to

computed through the self-attention mechanism, and

is the layer normalisation operation for stabilising the training process.

The specific calculations for the self-attention mechanism are as follows:

a. Calculation of attention scores:

For each element of the input sequence , compute its query vector , key vector and value vector , respectively : where is the learnable weight matrix.

b. Calculation of attention weights:

The similarity between query vectors and key vectors is computed using dot product and converted to attention weights by Softmax function:

where

is the dimension of the key vector and

denotes the attentional weight of the input

to

.

c. Calculation of weighted sums:

Combining the attention weights and value vectors yields a context vector for the input

:

The hidden state processed by the self-attention mechanism contains contextual information about each element in the input sequence, providing rich semantic information for the decoding phase.

3.5.3. Decoding Phase

In the decoding phase, the decoder progressively generates diagnostic suggestions . Each generated token is computed on the basis of the previously generated tokens and the encoder output by means of self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms.

The decoder is calculated as follows:

a. Self-attention mechanisms:

For each token

input to the decoder, its contextual representation is first computed through the self-attention mechanism:

where

denotes all previously generated tokens and

is the context vector of the current token.

b. Cross-attention mechanisms:

Then, the output of the encoder is combined with the current hidden state of the decoder using a cross-attention mechanism to obtain an enhanced contextual representation:

where

denotes the contextual information related to the encoder output computed through the cross-attention mechanism.

c. Generate output tags:

Finally, the decoder generates the probability distribution of the current marker

by means of a linear transformation and a Softmax function, and samples or selects the most probable marker from it as output:

where

is the weight matrix of the decoder output layer.

The generated diagnostic proposal is a coherent text consisting of multiple tokens covering the lesion type, disease stage and other relevant diagnostic information.

3.5.4. Enhancing Generation with RAG

During the decoding process, the RAG module enhances the decoder’s performance by retrieving relevant medical literature or knowledge fragments, providing additional context. These retrieved knowledge fragments are encoded as vectors and combined with the input sequence encodings to form an augmented input. This approach results in more professional and reliable diagnostic suggestions.

In summary, this study utilizes the self-attention and multi-head attention mechanisms of the Transformer model to achieve automatic generation of medical imaging report texts. By integrating RAG technology, the system effectively incorporates relevant information from medical knowledge bases, generating accurate, coherent, and clinically applicable diagnostic suggestions.

3.6. Evaluation and Feedback

To assess the diagnostic performance of the LLM-MID and LLM-RAG-MID methods, a multi-dimensional evaluation strategy was adopted. Both methods were applied to the same clinical symptoms and imaging findings, and their diagnostic conclusions and differential diagnosis lists were recorded. The evaluation focused on diagnostic accuracy (whether the diagnosis aligns with the actual lesion and typical clinical presentation), comprehensiveness of differential diagnosis (whether key differential diseases are considered), reasoning process rationality (alignment with existing medical knowledge and logical consistency), and clinical feasibility. This comprehensive assessment aims to evaluate the practical value of LLM-MID and LLM-RAG-MID in medical imaging diagnostic scenarios.

4. Experimental Setup

To comprehensively evaluate the overall performance of the LLM and LLM-RAG-MID proposed in this study, a series of comparative experiments were designed, focusing on four dimensions: diagnostic accuracy, reasoning, comprehensiveness in differential diagnosis, and clinical feasibility. The experimental setup and data selection closely align with real-world clinical scenarios to derive more practical conclusions.

In the baseline experiment, we used a pre-trained Large Language Model (LLM) to analyze and infer medical imaging report texts and generate diagnostic suggestions directly. The base model selected for this experiment is based on the ERNIE 3.5 LLM solution [

https://yiyan.baidu.com/]. In this baseline experiment, all medical imaging reports and relevant clinical information were de-identified and input into the LLM, after which the output diagnostic text was recorded and evaluated. This approach allows us to test the inherent potential and limitations of “pure LLM” in medical imaging diagnosis tasks, providing a comparison benchmark for subsequent configurations.

In the enhanced configuration, we introduce a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) module, which works alongside the aforementioned large language model to make diagnostic decisions. All research data come from de-identified case materials and adhere to ethical review and privacy protection regulations. Further details on data preprocessing and the experiment setup are provided in the appendix.

4.1. Case Design

To ensure the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the experiments, three main medical imaging diagnostic scenarios—epidural ependymoma, low-grade glioma in the brain, and cirrhosis with multiple intrahepatic nodules—were selected for case testing. These cases were carefully selected from the literature to simulate common yet diagnostically challenging imaging scenarios encountered in clinical practice, thereby comprehensively evaluating the system’s diagnostic assistance capabilities.

Please provide the most likely diagnosis based on the case descriptions listed in

Table 1.

4.2. Experimental Procedure

4.2.1. Data Preprocessing:

Preprocess all text data (such as imaging report descriptions and clinical notes) by tokenizing, removing noise characters, and standardizing terminology.

Input the preprocessed text into the LLM models on different platforms, ensuring a consistent data input format for the subsequent generation of diagnostic suggestions.

4.2.2. Model Inference:

a. LLM Solo Experiment: Directly input the preprocessed text into the LLM to obtain its initial interpretation and diagnostic suggestions.

b. LLM-RAG Joint Experiment: Prior to LLM generation, use the RAG module to retrieve matching reference fragments from relevant medical literature and guidelines. Combine the retrieved professional information with the original input and feed it into the LLM to generate more accurate and comprehensive diagnostic suggestions.

4.2.3. Result Recording and Analysis:

Record the results for each experimental case, including the diagnostic suggestions and explanations provided by the system. Conduct blinded evaluations by medical experts to ensure objectivity and reliability. The evaluation criteria include diagnostic accuracy, reasoning, comprehensiveness in differential diagnosis, and clinical feasibility. Compare the results of different configurations (LLM-MID vs. LLM-RAG-MID) to quantify the impact of RAG technology on improving diagnostic performance.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

In this section, the experimental results will be presented and analyzed for three scenarios: intraspinal ependymoma, low-grade glioma in the brain, and cirrhosis with multiple nodules. The evaluation focuses on changes in diagnostic accuracy, rationality, comprehensiveness in differential diagnosis, and clinical feasibility with and without RAG technology support, expert comparisons of initial diagnoses and diagnostic analysis, and case-specific analysis.

5.1. Case 1

5.1.1. LLM-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnosis is spinal cord tumor. It is recommended to perform further pathological examination to clarify the tumor’s nature and formulate a targeted treatment plan.

a. Diagnostic Basis:

The patient has an oval-shaped lesion in the spinal cord at the center, with cystic changes and hemorrhage inside the tumor, which is characteristic of spinal cord tumors. The enhanced scan shows significant enhancement with clear borders, supporting the diagnosis of spinal cord tumor. The notable swelling and surrounding edema of the spinal cord indicate that the lesion exerts significant pressure and causes inflammation in the spinal cord. This may lead to neurological dysfunction, such as bilateral lower limb weakness.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Myelitis: May cause spinal cord swelling and inflammation, but typically does not present with the intramedullary oval-shaped lesion, cystic changes, and hemorrhage seen in this case. ②. Spinal Vascular Malformation: Can lead to spinal cord swelling, but generally does not involve intramedullary lesions, and the lesion is vascular in nature. ③. Multiple Sclerosis: A demyelinating disease that can cause spinal cord dysfunction, but the lesions are typically multiple, and do not present as an intramedullary oval-shaped lesion with cystic changes and hemorrhage.

5.1.2. LLM-RAG-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnosis is spinal ependymoma. It is recommended to proceed with prompt surgery for definitive pathological diagnosis and to develop an individualized treatment plan based on the latest clinical guidelines and research. Post-surgery rehabilitation is required to promote neurological function recovery, with regular follow-up to monitor for recurrence or progression.

a. Diagnostic Basis:

The patient is a 59-year-old female, within the typical age range for spinal ependymoma (40-60 years). The symptom of progressive bilateral lower limb weakness aligns with the clinical presentation of spinal ependymoma.

The lesion is centrally located in the spinal cord, consistent with common locations for spinal ependymomas. The tumor shows cystic changes and hemorrhage, with significant enhancement on contrast scans, clear borders, and surrounding edema, all matching the imaging characteristics of spinal ependymoma.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Spinal Astrocytoma: May cause spinal cord swelling and dysfunction but is more common in children and adolescents. The imaging usually shows irregular shapes, less cystic degeneration, and minimal hemorrhage, with uneven enhancement and unclear borders. This patient’s age and imaging features do not align with spinal astrocytoma. ②. Hemangioblastoma: A vascular tumor more common in younger individuals, presenting with large cysts and small nodules with significant enhancement. This patient lacks these imaging characteristics. ③. Spinal Cavernous Hemangioma: Known for recurrent bleeding, with mixed signal intensity on imaging, indicating old hemorrhage and minimal enhancement. The patient lacks a bleeding history and the imaging features are inconsistent. ④. Spinal Metastasis: Typically presents with a history of primary tumors and rapid symptom progression. Imaging shows significant enhancement and notable surrounding edema. This patient has no history of primary tumors and her symptoms are progressing slowly. ⑤. Myelitis: Acute or subacute onset, often with an infection or autoimmune history. Imaging shows spinal cord swelling, signal changes, with no obvious mass lesion, and may show irregular enhancement. The patient’s gradual onset and the clear space-occupying lesion on imaging rule out this diagnosis.

5.1.3. Diagnostic Strategy and Decision Optimization

Based on the detailed analysis of the imaging characteristics, the LLM-RAG-MID system integrated imaging findings and clinical information more thoroughly after training, optimizing the diagnostic process. The traditional LLM diagnosis summarized the condition as “spinal cord tumor,” but did not specify the type of tumor. Its differential diagnosis included myelitis, spinal vascular malformation, and multiple sclerosis, diseases that could cause spinal cord swelling or dysfunction but did not match the key features of this case. The improved diagnosis clearly identified spinal ependymoma as the most likely diagnosis, based on the patient’s age, progressive bilateral lower limb weakness, and imaging showing a centrally located intramedullary lesion with cystic changes, hemorrhage, and significant enhancement. The enhanced differential diagnosis focused on more relevant diseases, such as spinal astrocytoma, hemangioblastoma, spinal cavernous hemangioma, and spinal metastasis, providing a detailed analysis of the differences between each disease and this case. This resulted in a more targeted, logically rigorous, and professionally advanced diagnosis, providing a solid foundation for developing an effective treatment plan.

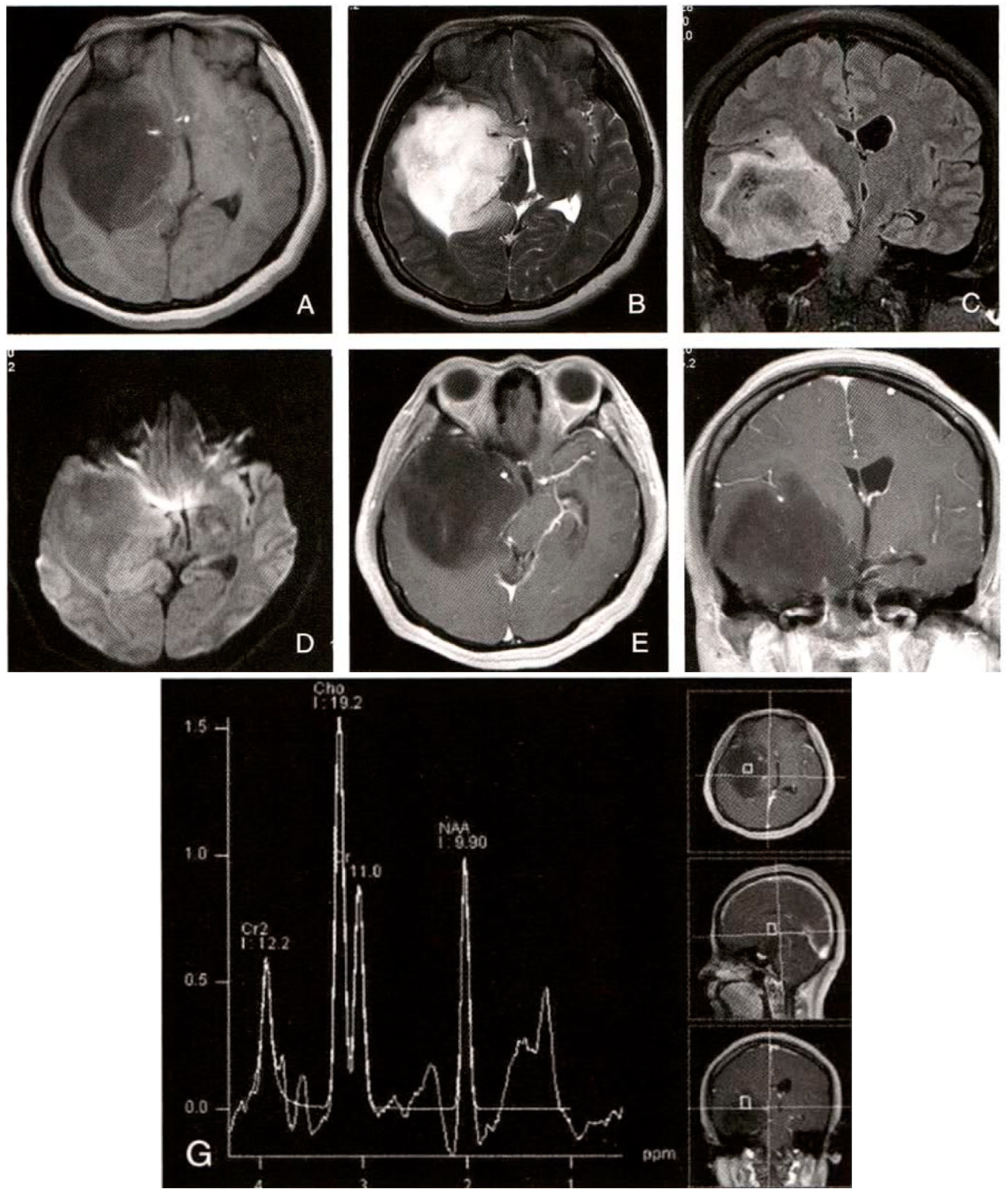

5.2. Case 2

5.2.1. LLM-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnoses are cerebral cysticercosis (particularly in the viable cyst stage) or brain glioma (although cysticercosis seems more likely considering the MRS results). The final diagnosis should integrate the patient’s medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and possibly cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

a. Diagnostic Basis:

Patient’s age and symptoms: The patient is a young female with a 3-month history of headache and seizures, suggesting a central nervous system disorder. MRI findings: The lesion is located in the right temporal lobe. T1WI shows uniform low signal, T2WI and FLAIR show uneven high signals, suggesting fluid content or cystic changes. No significant enhancement on the contrast scan suggests the lesion is not vascular or actively inflammatory. Surrounding edema and mass effect indicate significant pressure on surrounding tissue. MRS results: The NAA peak is significantly reduced, and the Cho peak is significantly increased, with Cho/NAA = 1.94. This pattern is typical for cysticercosis, especially when the cysts are viable, as cysticercosis contains large amounts of choline, while neuronal damage decreases NAA.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Brain Glioma: Usually shows irregular signal changes on MRI, possibly with cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, or necrosis. Gliomas, particularly malignant ones, typically show significant enhancement. MRS may also show increased Cho and decreased NAA peaks, but not as markedly as in cysticercosis. ②. Brain Abscess: Often presents with an infection history and ring-like enhancement on MRI with central liquefaction. Clinical symptoms may include fever, headache, and nausea. ③. Cerebral Hemorrhage or Infarction: Cerebral hemorrhage shows high signal on T1WI (subacute phase) and low signal on T2WI (acute phase) with significant mass effect. Infarction shows low signal on T1WI and high signal on T2WI, usually with cerebrovascular disease evidence. ④. Brain Metastasis: Typically has a history of primary tumors in other locations. MRI shows nodular lesions with enhancement on contrast scans.

5.2.2. LLM-RAG-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnosis is low-grade astrocytoma (WHO grade II). Key differential diagnoses include cysticercosis and other intracranial tumors. Detailed history-taking, careful analysis of imaging features, and necessary laboratory tests will help clarify the diagnosis.

a. Diagnostic Basis:

The patient is 35 years old, which falls within the typical age range for low-grade astrocytoma (30-40 years). Symptoms: Recurrent seizures and persistent headaches, which are consistent with the typical symptoms of low-grade astrocytoma. The disease duration is 2 years with slow progression, consistent with low-grade astrocytoma’s typical course. No history of epidemiological exposure or systemic symptoms, which helps exclude cysticercosis. MRI findings: The lesion is located in the white matter of the cerebral hemisphere (e.g., frontal or temporal lobe), showing isointense or low signal on T1WI, high signal on T2WI, and high signal on FLAIR, with indistinct borders and infiltrative growth, difficult to distinguish from surrounding brain tissue. Mild to moderate finger-like edema with mild mass effect. Enhancement scan: No significant enhancement or only mild patchy enhancement, consistent with low-grade astrocytoma. MRS features: A significant reduction in the NAA peak indicates neuronal damage or loss. The Cho peak is significantly increased, suggesting increased cell membrane synthesis and turnover, with active cell proliferation. The Cho/NAA ratio is elevated, typically greater than 1, supporting a tumor diagnosis.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Cysticercosis: No history of undercooked pork consumption or living in endemic areas. Symptoms: No systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, or elevated eosinophils. Imaging features: Cysticercosis usually presents with multiple lesions, widely distributed, with cysts showing a “head stage” (dot sign), whereas low-grade astrocytoma is a single lesion with no “head stage.” Lab tests: No cysticercosis antibodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid, and no elevated eosinophils in peripheral blood. ②. Other Intracranial Tumors: High-grade astrocytoma, meningioma, lymphoma, etc., may show different imaging features, such as clearer borders, more prominent enhancement, and greater mass effect. However, based on the clinical presentation, imaging features, and MRS results, these tumors can be ruled out.

5.2.3. Diagnostic Strategy and Decision Optimization

In the improved diagnosis, a more professional and accurate diagnostic approach was shown. Initially, cysticercosis was favored as the most likely diagnosis, mainly based on the patient’s MRI and MRS results. However, this judgment overlooked typical epidemiological and imaging features of cysticercosis, such as multiple cystic lesions, the “head stage” (dot sign), and the patient’s possible infection history. In the improved RAG configuration, LLM correctly identified low-grade astrocytoma (WHO grade II) as the most likely diagnosis. This conclusion was based on multi-dimensional analysis: accurate clinical feature assessment: the physician noted the patient’s age and symptoms matched the typical presentation of low-grade astrocytoma, such as recurrent seizures and persistent headaches, with slow disease progression and no infection-related systemic symptoms. Detailed imaging feature analysis: The improved diagnosis fully utilized MRI and contrast scan details, identifying a single solid lesion with indistinct boundaries, infiltrative growth, and finger-like edema, all of which were consistent with low-grade astrocytoma, ruling out cysticercosis. Proper interpretation of MRS metabolic features: The physician correctly interpreted the significantly lowered NAA peak and the increased Cho peak as metabolic characteristics of a tumor, recognizing that an elevated Cho/NAA ratio typically indicates active cell proliferation, not parasitic infection. Rigorous differential diagnosis: The physician systematically excluded cysticercosis and other intracranial tumors, providing strong opposing evidence, such as the lack of epidemiological exposure, no multiple cystic lesions, absence of the “head stage,” and no abnormal lab results.

5.3. Case 3

5.3.1. LLM-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnosis is hepatocellular carcinoma (Hepatocellular Carcinoma, HCC) with multiple intrahepatic nodules, including typical HCC nodules, hypervascular nodules, and necrotic cystic nodules. Key differential diagnoses include intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, liver metastasis, cirrhotic nodules, and hepatic hemangioma.

a. Diagnostic Basis:

Patient information and clinical presentation: The patient is a 36-year-old male with a 2-month history of fatigue. Although his age is not typical for liver cancer, clinical and imaging findings are more critical. Liver morphology and parenchymal changes: The liver edge is undulating, and the liver parenchyma shows diffuse small nodules, suggesting potential diffuse liver disease. MRI signal characteristics: The diffuse small nodules show isointense to slightly high signal on T1WI and isointense to slightly low signal on T2WI. No enhancement in the arterial phase, and isointense or slightly low signal in the portal venous and equilibrium phases, suggesting cirrhosis or small non-active nodules. The right anterior liver lobe nodule shows uniform signal with significant enhancement in the arterial phase and isointense signal in the portal venous phase, consistent with typical enhancement patterns for hepatocellular carcinoma. The right posterior liver lobe nodule shows uneven signal with a “nodule within a nodule” appearance, significant enhancement in the arterial phase, and reduced enhancement in the portal venous phase, suggesting necrosis or cystic degeneration, a common feature in hepatocellular carcinoma.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC): Typically shows a mass at the liver edge with low signal on T1WI, high signal on T2WI, and mild enhancement in the arterial phase, with uneven enhancement in the portal venous or delayed phase. The enhancement pattern of ICC differs from that of HCC, and bile duct dilation is more common. ②. Liver Metastasis: Usually has a history of primary tumors, with multiple round or oval lesions showing smooth edges, low signal on T1WI, high signal on T2WI, and “target sign” or ring-like enhancement on contrast scans. ③. Cirrhotic Nodules: May present as multiple liver nodules, but usually smaller, homogeneous, with minimal enhancement, and lacking the characteristic enhancement pattern of HCC. ④. Hepatic Hemangioma: Shows low signal on T1WI, high signal on T2WI, and a “blooming artifact” appearance, with “fast in, slow out” enhancement on contrast scans, which is distinct from the enhancement pattern of HCC.

5.3.2. LLM-RAG-MID Diagnostic Result:

The most likely diagnosis is hepatocellular carcinoma (advanced stage) with cirrhosis and multiple intrahepatic nodules (including regenerative nodules, low-grade dysplastic nodules, and possibly early hepatocellular carcinoma nodules).

a. Diagnostic Basis:

The patient is a middle-aged male with persistent fatigue, which is a common clinical feature of hepatocellular carcinoma.

The undulating liver edge suggests cirrhosis. The right anterior liver nodule exhibits the typical “fast in, fast out” enhancement pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma. The right posterior liver nodule shows uneven signal with a “nodule within a nodule” appearance, with arterial phase enhancement and reduced signal in the portal venous phase, highly suggestive of hepatocellular carcinoma. The diffuse small nodules likely represent regenerative nodules or low-grade dysplastic nodules in the context of cirrhosis.

b. Differential Diagnosis:

①. Regenerative Nodules: Typically smaller than 3mm, homogeneous in signal, isointense on T1WI and T2WI, with no or mild enhancement. While the diffuse small nodules here show some characteristics of regenerative nodules, the right anterior and posterior liver nodules do not fit this diagnosis. ②. Low-Grade Dysplastic Nodules: Similar signal characteristics to regenerative nodules but slightly larger, with no significant enhancement. The nodules in this case show enhancement, ruling out this diagnosis. ③. High-Grade Dysplastic Nodules: May show mild enhancement but lack “washout.” The nodules in this case exhibit the characteristic “fast in, fast out” enhancement pattern, ruling this out. ④. Other Liver Tumors: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, liver metastasis, etc., show different enhancement patterns and signal characteristics from hepatocellular carcinoma and lack the “nodule within a nodule” appearance.

5.3.3. Diagnostic Strategy and Decision Optimization

The diagnosis generated with the RAG configuration showed significant improvements in professionalism, accuracy, and comprehensiveness. The improved diagnosis clearly identified “hepatocellular carcinoma (advanced stage) with cirrhosis and multiple intrahepatic nodules (including regenerative nodules, low-grade dysplastic nodules, and possibly early hepatocellular carcinoma nodules),” emphasizing the advanced stage of HCC and providing a detailed description of the multiple intrahepatic nodules, demonstrating a deep understanding of liver disease complexity. The diagnostic basis is more systematic and rigorous. The physician integrated clinical features with imaging findings, highlighting cirrhosis and thoroughly analyzing the imaging characteristics and pathological significance of each nodule, thus improving diagnostic accuracy. The differential diagnosis is more thorough and logically sound. The physician systematically excluded benign or premalignant lesions, such as regenerative nodules, low-grade dysplastic nodules, and high-grade dysplastic nodules, based on imaging features and enhancement patterns, providing strong supporting evidence to exclude these possibilities. Additionally, the diagnosis considered other liver tumors, reflecting a comprehensive approach to differential diagnosis. Finally, the expression is more academic and professional. The improved diagnosis used specialized medical terminology, making the expression clear, accurate, and logically rigorous, in line with academic writing conventions, facilitating better communication in clinical and research settings.

Overall, these three case analyses show that the improvements made through learning documents significantly enhanced the diagnostic ability of the large language model (LLM), particularly in terms of accuracy, differential diagnosis comprehensiveness, and clinical decision support. By integrating key medical information using deep learning, the system accurately synthesizes clinical presentation, imaging features, and auxiliary test results, promoting multidisciplinary consultations and optimizing treatment pathways. The improved diagnosis reflects a higher level of professionalism, more comprehensive content, stronger evidence, and more academic expression, providing robust support for clinical decision-making and academic research.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a medical imaging diagnosis assistance system (LLM-RAG-MID) that combines Large Language Models (LLM) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) technology, and its effectiveness has been validated through a series of experiments. The results show that the RAG module can rapidly retrieve and integrate relevant specialized knowledge and literature for the current case, making the diagnostic process more efficient and significantly improving the system’s diagnostic accuracy and rationality, particularly excelling in handling complex cases. The RAG configuration’s potential to reduce labor costs makes it highly valuable for practical clinical applications, ensuring its clinical feasibility. This feature is especially suited for clinical environments that require rapid processing of large volumes of cases, such as radiology departments in large hospitals or specialized clinics, where high-quality diagnostic suggestions can be generated quickly.

The performance of the RAG module largely depends on the size and quality of the knowledge base. Future work will focus on building a more comprehensive and high-quality medical knowledge base, integrating multi-source medical literature, case data, and clinical guidelines, to further optimize and expand the diagnostic assistance system proposed in this study, enhancing its retrieval capability and diagnostic accuracy.

References

- Hussain S, Mubeen I, Ullah N, et al. Modern diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: a review. BioMed research international, 2022, 2022(1): 5164970. [CrossRef]

- Peng Z, Ren X. Application and Development of Artificial Intelligence-based Medical Imaging Diagnostic Assistance System. International Journal of Biology and Life Sciences, 2024, 6(1): 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Lu Z, Peng Y, Cohen T, et al. Large language models in biomedicine and health: current research landscape and future directions. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2024, 31(9): 1801-1811. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Jeyyab M, Alrosan S, Alkhawaldeh I. Harnessing large language models in medical research and scientific writing: A closer look to the future: Llms in medical research and scientific writing. High Yield Medical Reviews, 2023, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Sąsiadek M, Romanowski C, Jacków-Nowicka J. Imaging of intramedullary tumours of the spinal cord. Polish Journal of Radiology, 2024, 89: e531. [CrossRef]

- Hu L L, Liang S, Zhong P, et al. Analysis of Spinal Pilocytic Astrocytoma in 12 Case Reports and Literature Review. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology, 2024, 108(1): 82. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Chauhan, A.; Raj, G.; et al. Imaging Features of Intramedullary Spinal Cord Lesions with Histopathological Correlation. Asian J. Oncol. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Norman S, Juthani R G, Magge R. Foundations of the diagnosis and management of low-grade gliomas. World Neurosurgery, 2022, 166: 306-312. [CrossRef]

- Habib A, Jovanovich N, Hoppe M, et al. MRI-based radiomics and radiogenomics in the management of low-grade gliomas: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2021, 10(7): 1411. [CrossRef]

- Möller K, Safai Zadeh E, Görg C, et al. Focal liver lesions other than hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Diagnostic challenges. Journal of translational internal medicine, 2023, 10(4): 308-327. [CrossRef]

- Gao F, Cai P, Liu C, et al. Research progress in imaging characteristics of precancerous nodules in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Zhonghua gan Zang Bing za zhi= Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi= Chinese Journal of Hepatology, 2020, 28(1): 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Renzulli M, Braccischi L, D’Errico A, et al. State-of-the-art review on the correlations between pathological and magnetic resonance features of cirrhotic nodules. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Joo I, Kim S Y, Kang T W, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of hepatobiliary phase hypointense nodules without arterial phase hyperenhancement at gadoxetic acid–enhanced MRI: a multicenter study. Radiology, 2020, 296(2): 335-345. [CrossRef]

- Hu M, Qian J, Pan S, et al. Advancing medical imaging with language models: featuring a spotlight on ChatGPT. Physics in Medicine & Biology, 2024, 69(10): 10TR01. [CrossRef]

- D’Antonoli T A, Stanzione A, Bluethgen C, et al. Large language models in radiology: fundamentals, applications, ethical considerations, risks, and future directions. Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, 2024, 30(2): 80. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; et al. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Nielsen I E, Tripathi A, et al. Transformers in time-series analysis: A tutorial. Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing, 2023, 42(12): 7433-7466. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, A.; et al. AttentionViz: A Global View of Transformer Attention. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).