Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- An overview of the RAG architecture and its advantages over standalone language models.

- A survey of RAG applications in healthcare across tasks such as question answering, summarization, and evidence retrieval.

- A review of domain specific and standard evaluation metrics.

- A detailed discussion of challenges, including retrieval instability, generation latency, domain shift, and limited transparency.

- A synthesis of emerging directions such as multimodal retrieval, continual learning, federated architectures, and clinically aligned evaluation strategies.

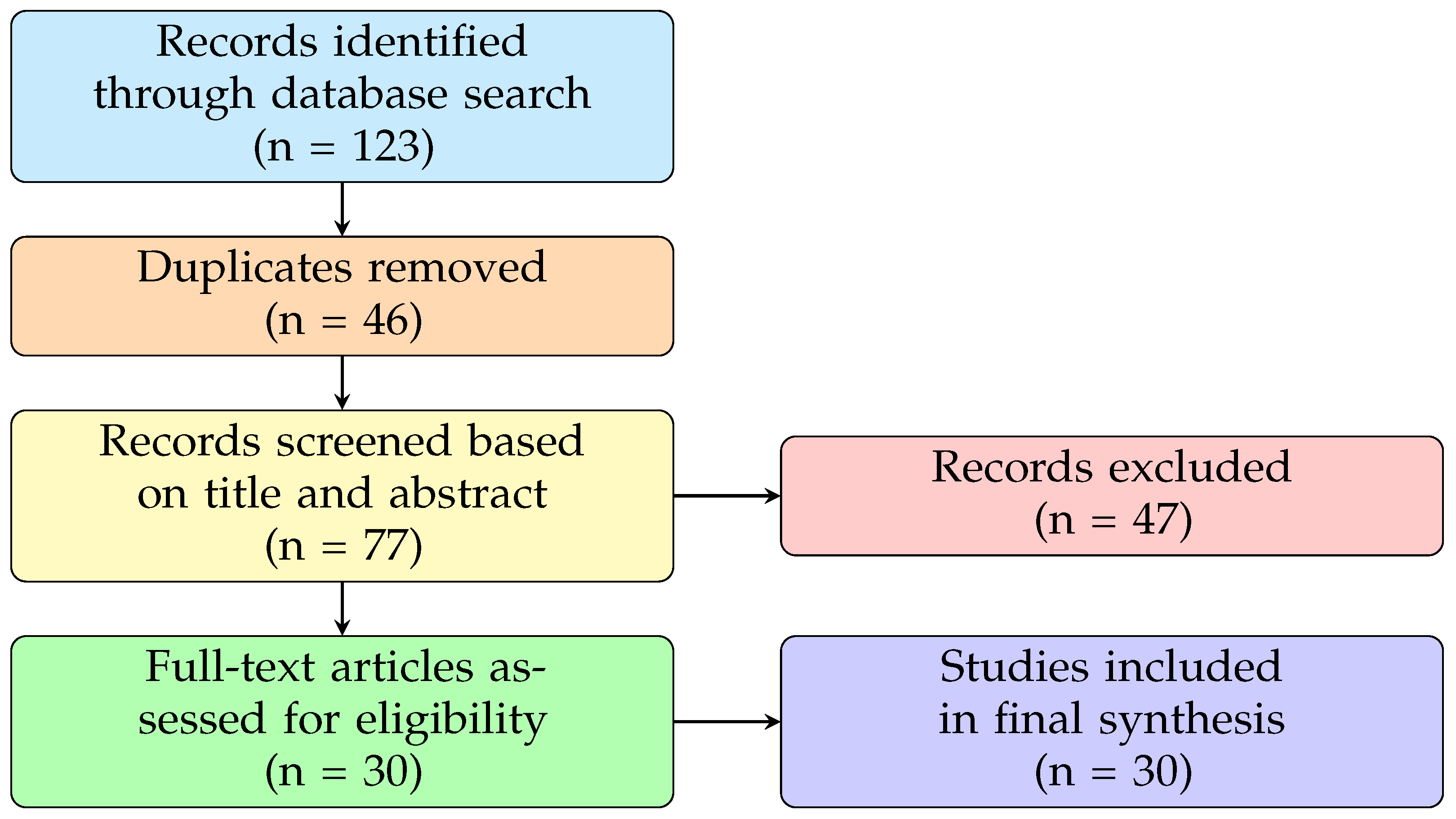

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies applying RAG or retrieval-augmented LLMs within healthcare domains.

- Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, or high-quality preprints published in English.

- Publications presenting empirical results or detailed implementation frameworks.

- Studies unrelated to healthcare or not utilizing RAG-based models.

- Editorials, opinion articles, or conceptual papers lacking experimental validation.

- Publications without full-text access or written in languages other than English.

2.2. Data Retrieval and Screening

2.3. Taxonomy Development

2.4. Research Objectives (RO)

- RO1: To assess the effectiveness of RAG in supporting clinical workflows and enhancing interpretability.

- RO2: To identify key gaps in current literature and propose directions for future RAG research that align with clinical needs, safety, and explainability.

3. Background and Fundamentals

3.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation: Foundations

- Sparse Retrieval: This approach relies on lexical overlap between the query and documents. Common methods include Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) [19] and BM25 [20]. TF-IDF assigns higher importance to terms that appear frequently in a document but rarely across the corpus, while BM25 improves upon TF-IDF by incorporating term frequency saturation and document length normalization. Sparse retrievers are fast, interpretable, and require no training. However, they struggle to capture semantic similarity and are sensitive to lexical variations. It is an important limitation in the medical domain, where abbreviations, synonyms, and varied terminology are frequent.

- Dense Retrieval: Unlike sparse retrieval, dense retrievers use neural encoders to map both queries and documents into a shared embedding space, enabling semantic similarity matching. These models are typically trained on large datasets using contrastive learning objectives, allowing them to capture meaning beyond exact word overlap. Popular dense retrievers include dense passage retrieval (DPR) [21]. In clinical settings, dense retrieval is useful for handling synonyms, abbreviations, and contextually rich queries. However, dense retrievers are more computationally expensive, require training data, and can be less interpretable than their sparse counterparts.

| Key Points | TF-IDF | BM25 | DPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Sparse (lexical) | Sparse (lexical) | Dense (neural) |

| Retrieval Method | Term frequency weighting | Probabilistic scoring with term normalization | Bi-encoder with semantic embeddings |

| Similarity Metric | Cosine similarity | BM25 score | Dot product or cosine similarity |

| Training Requirement | None | None | Supervised (Q-A pairs) |

| Context Sensitivity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Efficiency | Fast | Fast | Moderate (GPU preferred) |

| Scalability | High | High | Moderate |

| Memory Usage | Low | Low | High |

| Output Quality | Lexical match only | Improved over TF-IDF via ranking | Context-aware semantic relevance |

| Typical Use Cases | Baseline IR, filtering | Search engines, ranking tasks | RAG, QA, chatbots |

| Dependencies | Bag-of-words model | Bag-of-words + heuristics | Pretrained LLMs (e.g., BERT) |

| Key Points | Sparse Retrieval | Dense Retrieval |

|---|---|---|

| Retrieval Mechanism | Lexical token overlap | Learned embedding similarity |

| Input Representation | Bag-of-Words (BoW) vectors | Neural embeddings (contextual) |

| Similarity Metric | BM25, TF-IDF (exact match) | Dot product or cosine similarity |

| Training Requirement | No training needed | Requires supervised training |

| Speed | Fast (index lookup) | Slower (approximate nearest neighbor search) |

| Semantic Matching | Low (sensitive to term variation) | High (captures semantic context) |

| Memory Usage | Low (compact index) | High (due to large vector storage) |

| Interpretability | High (term-level match explanation) | Low (black-box embeddings) |

| Common Tools | BM25, TF-IDF, Elasticsearch | DPR |

| Suitability for Healthcare | Useful for structured queries and known terminology | Effective for unstructured clinical text and synonyms |

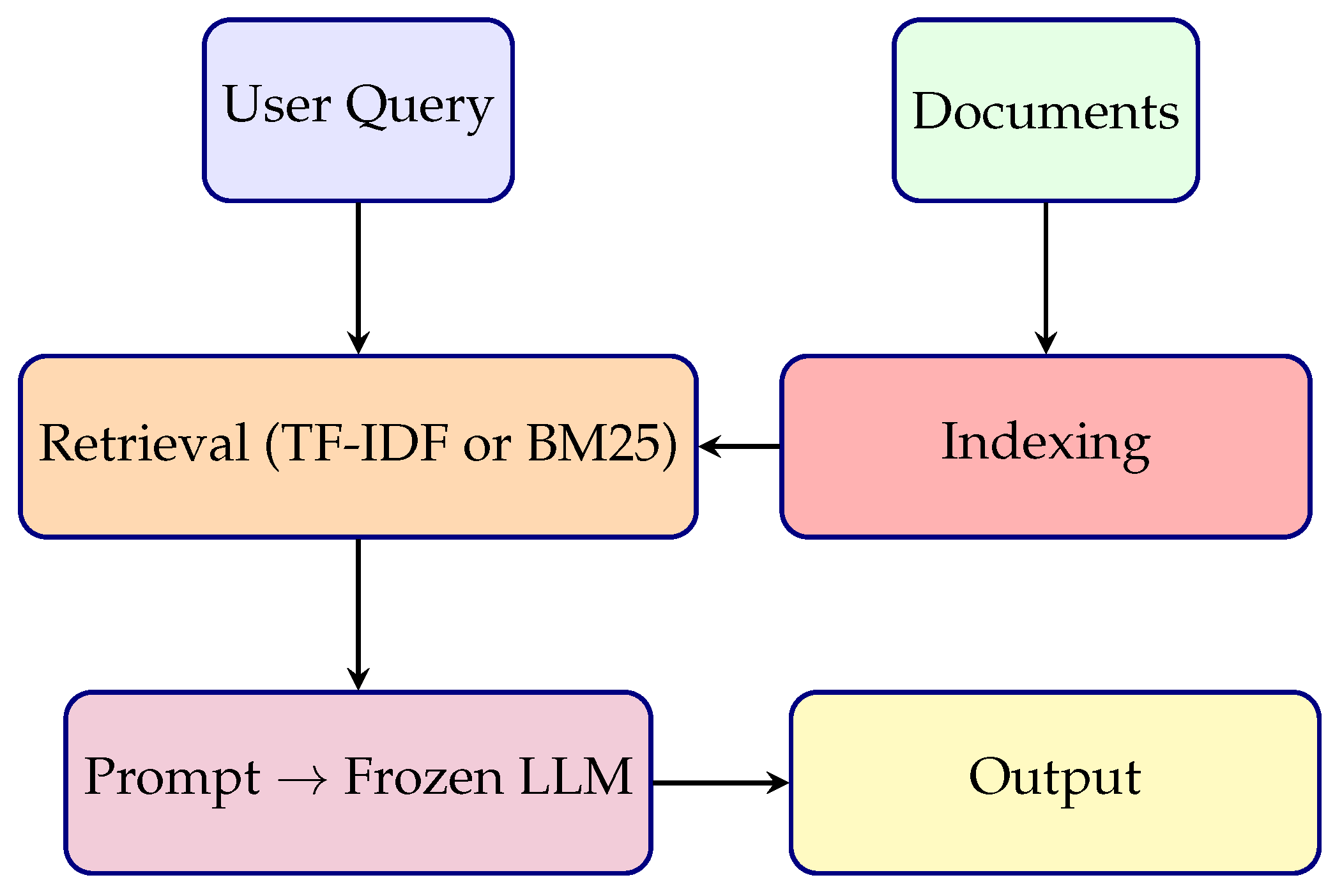

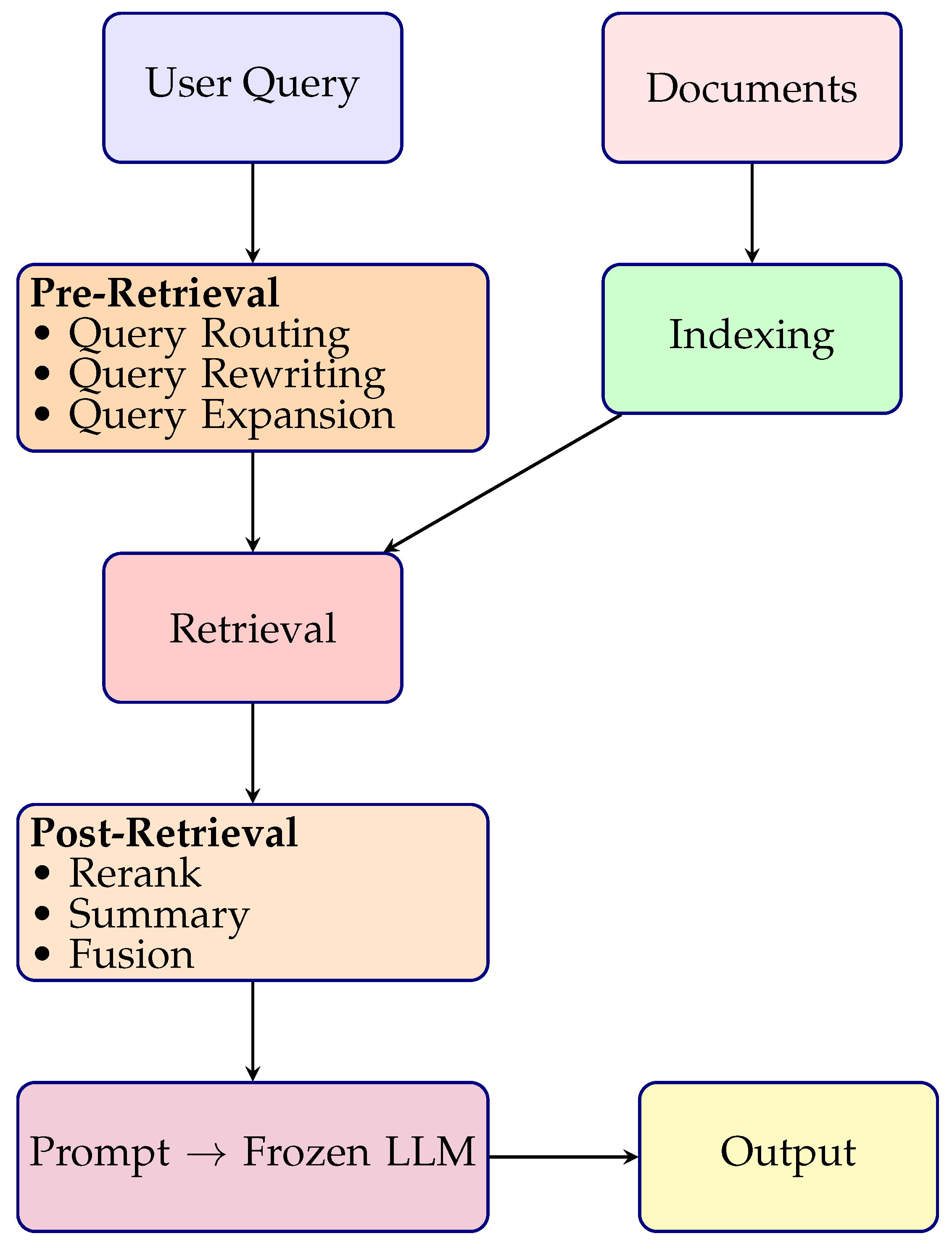

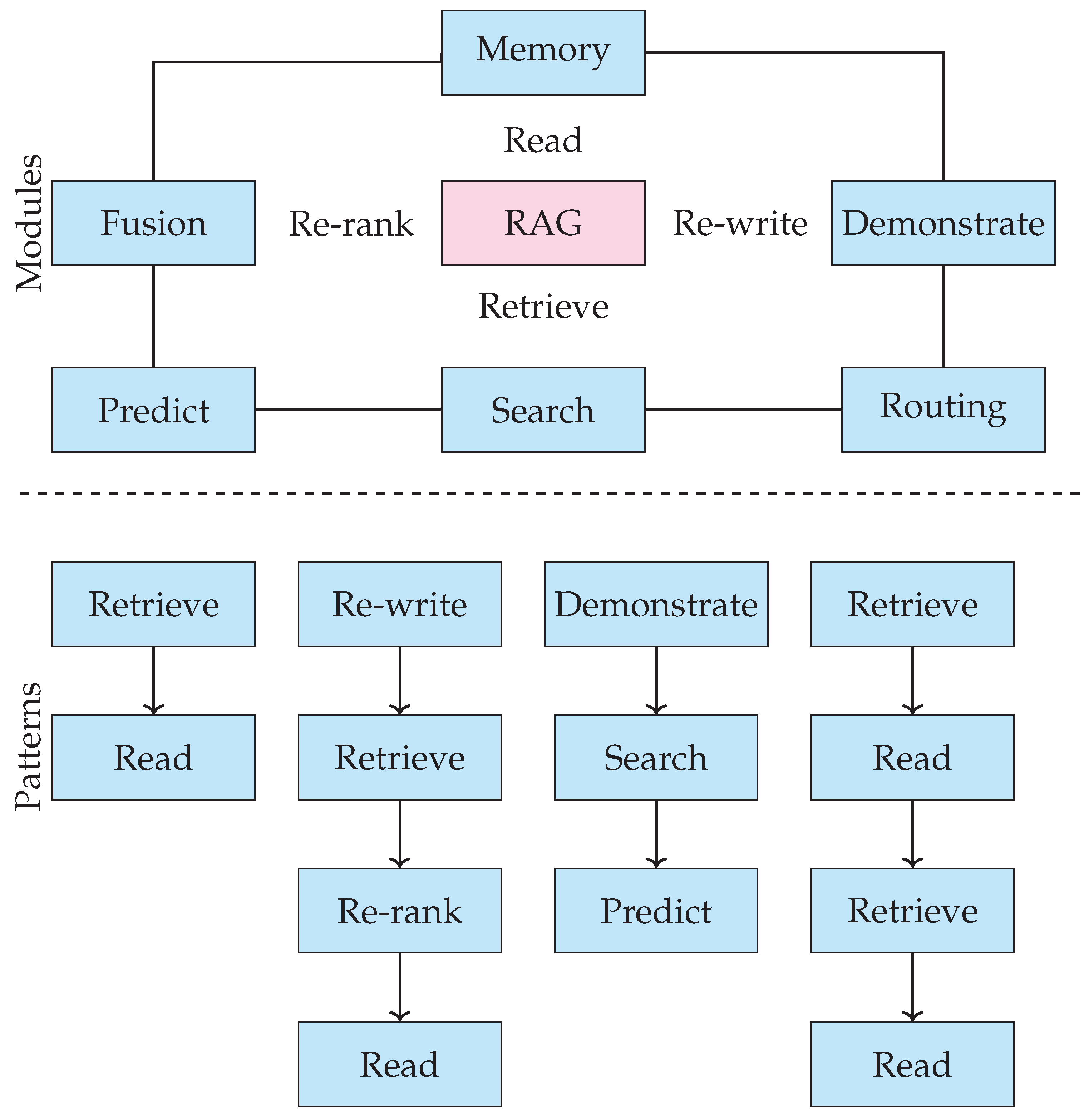

3.2. RAG Variants

4. Related Work

4.1. General Clinical Applications of RAG

4.2. RAG Chatbots for Patient Interaction

4.3. Specialty-Focused RAG Models

4.4. RAG for Signal and Time-Series Tasks

4.5. Graph-Based and Ontology-Aware RAG Frameworks

4.6. RAG with Blockchain and Secure Architectures

4.7. Radiology-Specific Retrieval-Augmented QA

5. Applications

5.1. Diagnostic Assistance

5.2. Summarization of EHRs and Discharge Notes

5.3. Medical Question Answering

5.4. Patient Education and Conversational Agents

5.5. Clinical Trial Matching

5.6. Biomedical Literature Synthesis

6. Evaluation Framework: Metrics and Benchmarks

6.1. Domain-Specific Metrics for Clinical Validation

- FactScore assesses factual alignment between generated outputs and reference data, particularly for medical summaries and treatment plans [62].

- RadGraph-F1 measures overlap between generated and reference entity-relation graphs in radiology reports, ensuring structural and factual correctness [63].

- MED-F1 quantifies alignment of extracted entities with standard clinical terminology and is frequently applied to tasks like medical named entity recognition, particularly in datasets such as CheXpert [64].

6.2. Generation Quality Metrics

- BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) measures the degree of n-gram overlap between the generated and reference text. It is defined as:where denotes modified n-gram precision, are weights (commonly uniform), and BP is the brevity penalty to discourage overly short outputs.

- ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation), particularly ROUGE-L, evaluates the longest common subsequence between generated and reference texts, and is frequently used in summarization tasks involving clinical documents.

- F1 Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, particularly relevant for span-based extraction and classification tasks.

- BERTScore compares contextual token embeddings between candidate and reference texts using models such as BioBERT, offering semantic alignment beyond surface-level matching.

6.3. Retrieval Relevance Metrics

- Recall@k measures the fraction of relevant documents retrieved within the top-k results:

- Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) evaluates the average inverse rank of the first relevant document:

- Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (nDCG@k) considers both the relevance and position of retrieved documents:

6.4. Factual Consistency Metrics

- FEVER Score quantifies the correctness of generated claims against retrieved evidence. It has been adapted from open-domain fact-checking to biomedical domains.

- Faithfulness Metrics evaluate the consistency of generated responses with retrieved or reference content, using either entailment-based models or domain-specific factuality checkers.

- Response Time (Latency): Critical for real-time applications such as triage or bedside decision support, where generation delay can impact clinical workflow.

- Source Traceability: Refers to the model’s ability to link generated content back to specific retrieved sources, thereby enhancing transparency, auditability, and user trust.

6.5. Benchmark Datasets

- MedQA (USMLE): A multiple-choice question dataset derived from medical licensing exams, focused on clinical knowledge assessment [65].

- PubMedQA: Consists of biomedical abstracts paired with yes/no/maybe questions, requiring grounded reasoning and evidence-based answers [66].

- MIMIC-IV: A comprehensive, de-identified EHR dataset supporting tasks such as summarization, question answering, and document retrieval [17].

- MedDialog: A multilingual dataset of doctor-patient conversations, suitable for training and evaluating medical dialogue systems [67].

7. Challenges and Limitations

7.1. Retrieval Challenges in Clinical Contexts

7.2. Latency and Real-Time Applicability

7.3. Explainability and Source Attribution

7.4. Privacy, Compliance, and Governance

7.5. Evaluation Bottlenecks in Clinical Contexts

7.6. Multimodal Limitations

7.7. Infrastructure and Scalability Constraints

7.8. Continual Learning and Knowledge Drift

7.9. Lack of Human-in-the-Loop

7.10. Bias and Fairness Concerns

8. Discussion and Future Directions

8.1. RAG with Knowledge Graphs

8.2. Continual Learning and Dynamic Retrieval

8.3. Multimodal Integration

8.4. Federated and Privacy-Preserving RAG

8.5. Task-Specific Evaluation Frameworks

8.6. Human-in-the-Loop RAG Systems

8.7. RAG for Low-Resource Settings

8.8. Explainable RAG Pipelines

8.9. Clinical Workflow Integration

8.10. Bias Mitigation and Fairness Audits

9. Conclusion

References

- Neha, F.; Bhati, D. A Survey of DeepSeek Models. Authorea Preprints.

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nature Medicine 2025, 31, 943–950. [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhang, S.; Poon, H.; Liu, T.Y. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings in bioinformatics 2022, 23, bbac409. [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.; Li, K. Large Language Models in Medical Chatbots: Opportunities, Challenges, and the Need to Address AI Risks. Information 2025. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Altosaar, J.; Ranganath, R. ClinicalBert: Modeling Clinical Notes and Predicting Hospital Readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.05342 2019.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474.

- Ng, K.K.Y.; Matsuba, I.; Zhang, P.C. RAG in health care: a novel framework for improving communication and decision-making by addressing LLM limitations. Nejm Ai 2025, 2, AIra2400380. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10997 2023, 2.

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Geng, Y.; Fu, F.; Yang, L.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, J.; Cui, B. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for AI-Generated Content: A Survey, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2402.19473].

- Gaur, M. Knowledge-Infused Learning. PhD thesis, University of South Carolina, 2022.

- Spasic, I.; Nenadic, G. Clinical text data in machine learning: systematic review. JMIR medical informatics 2020, 8, e17984. [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2020, 404, 132306.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Kotei, E.; Thirunavukarasu, R. A systematic review of transformer-based pre-trained language models through self-supervised learning. Information 2023, 14, 187. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng, S.; Pollard, T.J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B.; et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Scientific data 2023, 10, 1.

- Lu, Q.; Dou, D.; Nguyen, T. ClinicalT5: A generative language model for clinical text. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, 2022, pp. 5436–5443.

- Bafna, P.; Pramod, D.; Vaidya, A. Document clustering: TF-IDF approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 International conference on electrical, electronics, and optimization techniques (ICEEOT). IEEE, 2016, pp. 61–66.

- Amati, G. BM25. In Encyclopedia of database systems; Springer, 2009; pp. 257–260.

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.S.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W.t. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. In Proceedings of the EMNLP (1), 2020, pp. 6769–6781.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. Modular rag: Transforming rag systems into lego-like reconfigurable frameworks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21059 2024.

- Zhu, Y.; Ren, C.; Xie, S.; Liu, S.; Ji, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, T.; He, L.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; et al. Realm: Rag-driven enhancement of multimodal electronic health records analysis via large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.07016 2024.

- Izacard, G.; Lewis, P.; Lomeli, M.; Hosseini, L.; Petroni, F.; Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Joulin, A.; Riedel, S.; Grave, E. Atlas: Few-shot learning with retrieval augmented language models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–43.

- Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Millican, K.; Van Den Driessche, G.B.; Lespiau, J.B.; Damoc, B.; Clark, A.; et al. Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 2206–2240.

- Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, S.Y.; Miao, C. Medrag: Enhancing retrieval-augmented generation with knowledge graph-elicited reasoning for healthcare copilot. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, 2025, pp. 4442–4457.

- Wang, C.; Long, Q.; Xiao, M.; Cai, X.; Wu, C.; Meng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y. Biorag: A rag-llm framework for biological question reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.01107 2024.

- Wang, G.; Yang, G.; Du, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, X. ClinicalGPT: large language models finetuned with diverse medical data and comprehensive evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09968 2023.

- Gu, Y.; Tinn, R.; Cheng, H.; Lucas, M.; Usuyama, N.; Liu, X.; Naumann, T.; Gao, J.; Poon, H. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH) 2021, 3, 1–23.

- S, S.K.; G, J.W.K.; E, G.M.K.; J, M.R.; Singh A, R.G.; E, Y. A RAG-based Medical Assistant Especially for Infectious Diseases. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), 2024, pp. 1128–1133. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Viviani, M. Enhancing Health Information Retrieval with RAG by prioritizing topical relevance and factual accuracy. Discover Computing 2025, 28, 27. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Guo, J.; Feng, T.; Ruan, C. Improving the RAG-based personalized discharge care system by introducing the memory mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 17th International Conference on Computer Research and Development (ICCRD). IEEE, 2025, pp. 316–322.

- Hammane, Z.; Ben-Bouazza, F.E.; Fennan, A. SelfRewardRAG: enhancing medical reasoning with retrieval-augmented generation and self-evaluation in large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Xu, R.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xu, H. Evaluation of the integration of retrieval-augmented generation in large language model for breast cancer nursing care responses. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 30794. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.L.; Dao, C.T.; Wang, L.; Shuai, Z.; Phan, T.N.M.; Ding, J.E.; Liao, C.C.; Hu, P.; Han, X.; Hsu, C.H.; et al. MEDPLAN: A Two-Stage RAG-Based System for Personalized Medical Plan Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.17900 2025.

- Aminan, M.I.; DARNELL, S.S.; Delsoz, M.; Nabavi, S.A.; Wright, C.; Kanner, E.; Jerkins, B.; Yousefi, S. GlaucoRAG: A Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Model for Expert-Level Glaucoma Assessment. medRxiv 2025, pp. 2025–07.

- Thompson, W.E.; Vidmar, D.M.; Freitas, J.K.D.; Pfeifer, J.M.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Chen, R.; Altay, G.; Manghnani, K.; Nelsen, A.C.; Morland, K.; et al. Large Language Models with Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Zero-Shot Disease Phenotyping, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2312.06457].

- Benfenati, D.; De Filippis, G.M.; Rinaldi, A.M.; Russo, C.; Tommasino, C. A retrieval-augmented generation application for question-answering in nutrigenetics domain. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 246, 586–595. [CrossRef]

- Ziletti, A.; DAmbrosi, L. Retrieval augmented text-to-SQL generation for epidemiological question answering using electronic health records. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop; Naumann, T.; Ben Abacha, A.; Bethard, S.; Roberts, K.; Bitterman, D., Eds., Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Pyae, M.S.; Phyo, S.S.; Kyaw, S.T.M.M.; Lin, T.S.; Chondamrongkul, N. Developing a RAG Agent for Personalized Fitness and Dietary Guidance. In Proceedings of the 2025 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON). IEEE, 2025, pp. 600–605.

- Cheetirala, S.N.; Raut, G.; Patel, D.; Sanatana, F.; Freeman, R.; Levin, M.A.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Dawkins, O.; Miller, R.; Steinhagen, R.M.; et al. Less Context, Same Performance: A RAG Framework for Resource-Efficient LLM-Based Clinical NLP. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.20320 2025.

- Kulshreshtha, A.; Choudhary, A.; Taneja, T.; Verma, S. Enhancing Healthcare Accessibility: A RAG-Based Medical Chatbot Using Transformer Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on IT Innovation and Knowledge Discovery (ITIKD). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–4.

- Shafi, F.R.; Hossain, M.A. Llm-therapist: A rag-based multimodal behavioral therapist as healthcare assistant. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2024-2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference. IEEE, 2024, pp. 2129–2134.

- Sree, Y.B.; Sathvik, A.; Akshit, D.S.H.; Kumar, O.; Rao, B.S.P. Retrieval-augmented generation based large language model chatbot for improving diagnosis for physical and mental health. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Electrical, Control and Instrumentation Engineering (ICECIE). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Sinha, K.; Singh, V.; Vishnoi, A.; Madan, P.; Shukla, Y. Healthcare Diagnostic RAG-Based Chatbot Triage Enabled by BioMistral-7B. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Innovation for Sustainability (EmergIN). IEEE, 2024, pp. 333–338.

- Nayinzira, J.P.; Adda, M. SentimentCareBot: Retrieval-augmented generation chatbot for mental health support with sentiment analysis. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 251, 334–341. [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Song, J.; Kim, M.G.; Yu, H.W.; Choe, E.K.; Chai, Y.J. Thyro-GenAI: A Chatbot Using Retrieval-Augmented Generative Models for Personalized Thyroid Disease Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 2450. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Thongprayoon, C.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Garcia Valencia, O.A.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Integrating retrieval-augmented generation with large language models in nephrology: advancing practical applications. Medicina 2024, 60, 445. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Sun, S.; Owens, J.; Galvez, V.; Gologorskaya, O.; Lai, J.C.; Pletcher, M.J.; Lai, K. Development of a liver disease–specific large language model chat interface using retrieval-augmented generation. Hepatology 2024, 80, 1158–1168. [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Subburam, D.; Lowe, K.; Santos, A.; Zhang, J.; Hwang, S.; Saduka, N.; Horev, Y.; Su, T.; Cote, D.; et al. ChatENT: Augmented Large Language Model for Expert Knowledge Retrieval in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. medRxiv 2023 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, P.; Sano, A. Zero-Shot ECG Diagnosis with Large Language Models and Retrieval-Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd Machine Learning for Health Symposium; Hegselmann, S.; Parziale, A.; Shanmugam, D.; Tang, S.; Asiedu, M.N.; Chang, S.; Hartvigsen, T.; Singh, H., Eds. PMLR, 10 Dec 2023, Vol. 225, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 650–663.

- Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wang, C. Enhancing treatment decision-making for low back pain: a novel framework integrating large language models with retrieval-augmented generation technology. Frontiers in Medicine 2025, 12, 1599241.

- Rani, M.; Mishra, B.K.; Thakker, D.; Khan, M.N. To Enhance Graph-Based Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) with Robust Retrieval Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 18th International Conference on Open Source Systems and Technologies (ICOSST). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Qi, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.; Menolascina, F.; Grau, V. Medical graph rag: Towards safe medical large language model via graph retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04187 2024.

- Edge, D.; Trinh, H.; Cheng, N.; Bradley, J.; Chao, A.; Mody, A.; Truitt, S.; Metropolitansky, D.; Ness, R.O.; Larson, J. From local to global: A graph rag approach to query-focused summarization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16130 2024.

- Sophaken, C.; Vongpanich, K.; Intaphan, W.; Utasri, T.; Deepho, C.; Takhom, A. Leveraging Graph-RAG for Enhanced Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies in Dentistry. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Information Technology (InCIT). IEEE, 2024, pp. 606–611.

- Shi, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Iwinski, H.; Wattenbarger, M.; Wang, M.D. Retrieval-augmented large language models for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients in shared decision-making. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, 2023, pp. 1–10.

- Su, C.; Wen, J.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhong, Z.; Hossain, M.S. Hybrid RAG-empowered multi-modal LLM for secure data management in Internet of Medical Things: A diffusion-based contract approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jabarulla, M.Y.; Oeltze-Jafra, S.; Beerbaum, P.; Uden, T. MedBlock-Bot: A Blockchain-Enabled RAG System for Providing Feedback to Large Language Models Accessing Pediatric Clinical Guidelines. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 38th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS). IEEE, 2025, pp. 845–850.

- Tayebi Arasteh, S.; Lotfinia, M.; Bressem, K.; Siepmann, R.; Adams, L.; Ferber, D.; Kuhl, C.; Kather, J.N.; Nebelung, S.; Truhn, D. RadioRAG: Online Retrieval-augmented Generation for Radiology Question Answering. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2025, p. e240476. [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Krishna, K.; Lyu, X.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Koh, P.W.; Iyyer, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hajishirzi, H. Factscore: Fine-grained atomic evaluation of factual precision in long form text generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14251 2023.

- Jain, S.; Agrawal, A.; Saporta, A.; Truong, S.Q.; Duong, D.N.; Bui, T.; Chambon, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lungren, M.P.; Ng, A.Y.; et al. Radgraph: Extracting clinical entities and relations from radiology reports. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.14463 2021.

- Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ko, M.; Yu, Y.; Ciurea-Ilcus, S.; Chute, C.; Marklund, H.; Haghgoo, B.; Ball, R.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. Chexpert: A large chest radiograph dataset with uncertainty labels and expert comparison. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 590–597. [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Pan, E.; Oufattole, N.; Weng, W.H.; Fang, H.; Szolovits, P. What disease does this patient have? a large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6421. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Dhingra, B.; Liu, Z.; Cohen, W.W.; Lu, X. Pubmedqa: A dataset for biomedical research question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.06146 2019.

- He, X.; Chen, S.; Ju, Z.; Dong, X.; Fang, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, R.; et al. MedDialog: Two Large-scale Medical Dialogue Datasets, 2020, [arXiv:cs.LG/2004.03329].

| No. | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | General Clinical Applications of RAG | Broad applications of RAG for tasks like clinical summarization, decision support, and guidelines. |

| 2 | RAG Chatbots for Patient Interaction | Conversational agents enhanced by retrieval for providing personalized medical advice. |

| 3 | Specialty-Focused RAG Models | RAG frameworks tailored for domains such as cardiology, nephrology, or oncology using specialty-specific knowledge bases. |

| 4 | RAG for Signal and Time-Series Tasks | Integration of RAG with biosignals like ECG, EEG, or wearable data for diagnostic interpretation. |

| 5 | Graph-Based and Ontology-Aware RAG Frameworks | Use of structured clinical ontologies or knowledge graphs for enhanced retrieval and explainability. |

| 6 | RAG with Blockchain and Secure Architectures | Incorporation of privacy-preserving, decentralized data retrieval using blockchain-enhanced architectures. |

| 7 | Radiology-Specific Retrieval-Augmented QA | RAG systems designed for image-report alignment, report generation, and visual question answering in radiology. |

| Keypoints | Naïve RAG | Advanced RAG | Modular RAG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Simple two-stage pipeline: retrieval + generation | Three-stage pipeline: pre-retrieval, retrieval, post-retrieval | Fully decomposed pipeline with plug-and-play components |

| Query Processing | Uses raw user query | Query rewriting, expansion, or routing applied before retrieval | Modular query handling with flexible preprocessing units |

| Retriever Type | Dense retrievers (e.g., DPR) | Hybrid retrievers combining dense + sparse (e.g., BM25 + dense) | Modular and replaceable retrievers (dense, sparse, hybrid, trainable) |

| Post-Retrieval Handling | No reranking or filtering | Reranking, summarization, and filtering of retrieved chunks | Dedicated modules for reranking, deduplication, and compression |

| LLM Role | Frozen LLM processes retrieved documents directly | Frozen LLM with prompt-adaptive input conditioning | Swappable LLM head (frozen, fine-tuned, adapter-based) |

| Training Flexibility | No training of retriever or generator | Retriever may be fine-tuned; generator remains frozen | Independent or joint training of all modules (retriever, reranker, generator) |

| Transparency | Low interpretability; retrieval-to-generation is a black box | Some transparency with reranking scores or summarization | High transparency; traceable intermediate outputs for each module |

| Use Case Suitability | Basic Q&A and document retrieval tasks | High-stakes applications like medical QA, EHR summarization | Production-ready systems, customizable deployments, and MLOps integration |

| Latency | Low due to fewer stages | Moderate to high depending on pre/post processing complexity | Configurable latency depending on module choices |

| Customization | Minimal | Moderate pipeline-level customization | Full customization at component level |

| RAG Variant | Training Strategy | Retriever Type | Advantages / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | No training; static retrieval | Sparse (e.g., TF-IDF) | Simple; fast; no task alignment; poor factual grounding |

| Modular | Independent training of R and G | Dense dual encoders (e.g., DPR) | Modular, scalable; lacks feedback from generator |

| Advanced | Joint + feedback loops | Hybrid (dense + sparse), knowledge-enhanced | Factual, dynamic, and adaptable; complex to implement |

| Open-domain | Pretrained on general corpora | Generic (e.g., Wikipedia) | Broad scope; risks hallucination and low domain relevance |

| Domain-specific | Tuned on medical corpora | Biomedical (e.g., PubMed, MIMIC) | High clinical accuracy; limited generalization outside domain |

| Challenge | Cause | Consequence | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Shift & Retrieval Noise | Heterogeneous EHR styles, outdated or mixed-quality sources | Retrieval mismatch, irrelevant or unsafe generations | Domain-adaptive retrievers, curated clinical corpus, context filters |

| Latency | Sequential retrieval and generation over large corpora | Delayed responses in real-time clinical scenarios | Lightweight retrievers, caching, on-device or edge retrieval |

| Lack of Explainability | no attribution linking sources to generated content | Low clinician trust, limited transparency | Source highlighting, rationale extraction, evidence traceability |

| Privacy & Compliance Risks | Inadequate de-identification, unrestricted protected health information access | Legal violations, re-identification risk | Secure indexing, redaction, audit trails, access control |

| Weak Clinical Retrieval | General retrievers overlook domain-specific semantics | Missed context, hallucinated content | Biomedical retrievers (e.g., BioBERT), ontology-guided search (UMLS) |

| Noisy & Unstructured Clinical Text | Abbreviations, typos, incomplete or inconsistent notes | Imprecise embeddings, factual drift | Preprocessing pipelines, clinical QA models, structured input templates |

| Evaluation Limitations | Generic NLP metrics, lack of clinical gold standards | Poor assessment of safety, factuality, and utility | Domain-specific metrics (FactScore, MED-F1), expert-in-the-loop evaluations |

| Multimodal Limitations | Text-only retrieval ignores imaging, labs, genomics | Incomplete or narrow decision support | Multimodal encoders, joint indexing, cross-modal retrieval |

| Infrastructure Constraints | High storage/compute requirements, poor connectivity | Limited feasibility in low-resource settings | Model compression, retriever distillation, offline retrieval setups |

| Knowledge Drift | Static models and outdated retrieval indices | Obsolete or harmful recommendations | Continual learning, live corpus updates, dynamic retrievers |

| Lack of Human Oversight | Fully automated pipelines without expert feedback | Errors propagate unchecked, especially in diagnosis | Feedback interfaces, clinician-in-the-loop retrieval and validation |

| Bias and Fairness | Skewed training corpora, underrepresented populations | Health disparities, biased or unsafe outputs | Diverse data curation, fairness evaluation, inclusive retriever tuning |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).