Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Photocatalyst Synthesis

2.1.1. CN-Precursors Synthesis

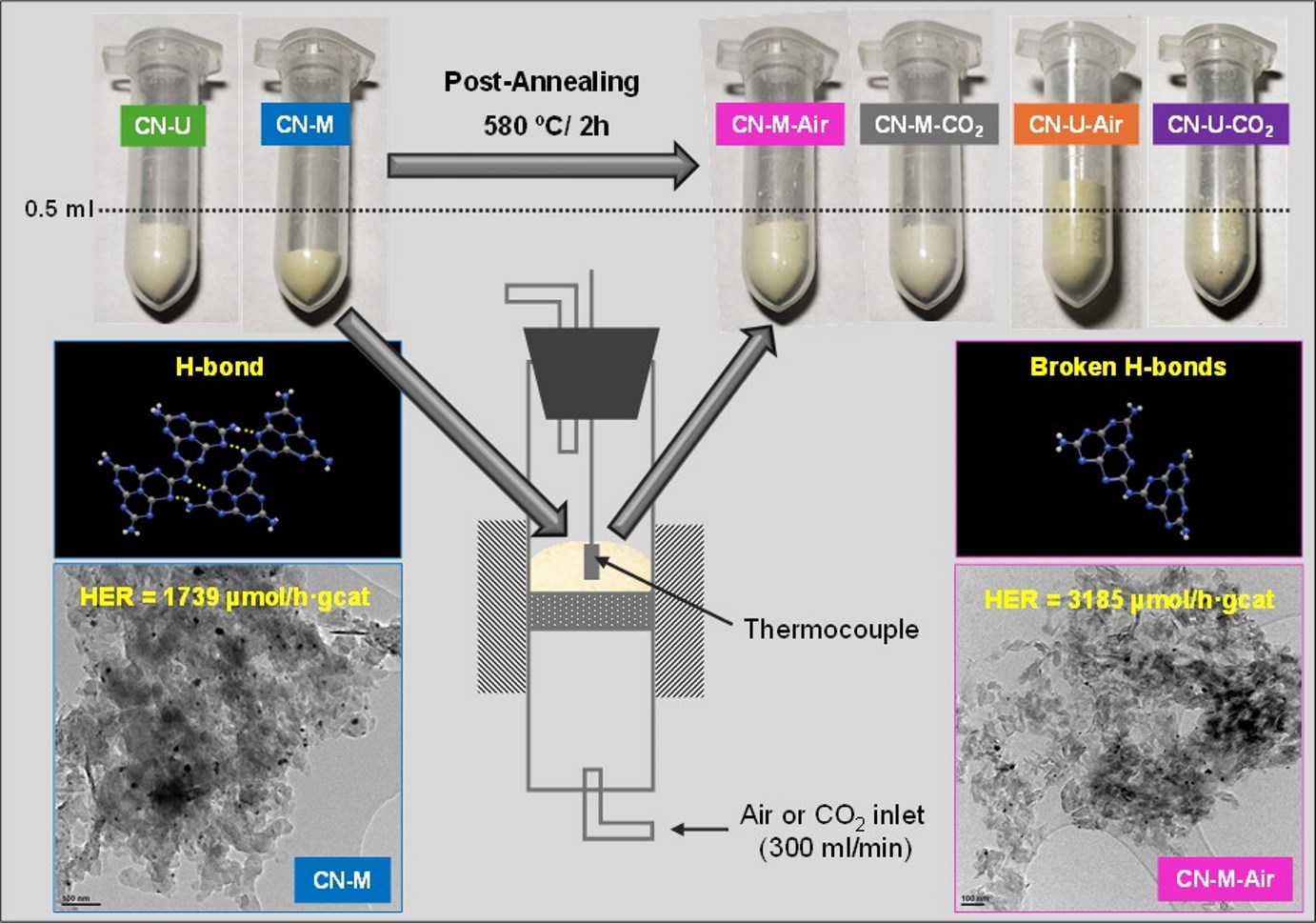

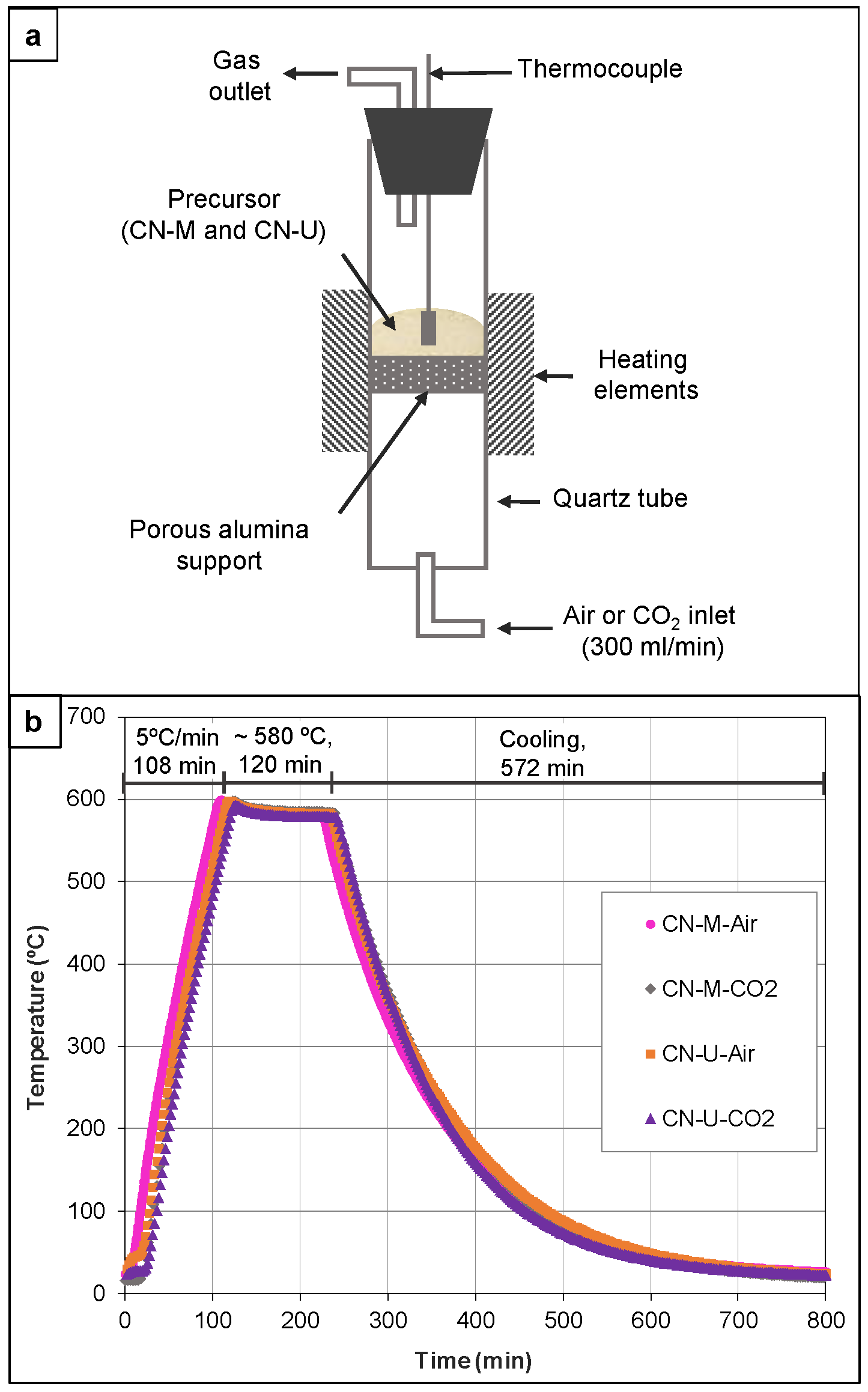

2.1.2. Post-Annealing of CN-Precursors

2.1.3. Co-Catalyst Deposition

2.2. Photocatalyst Characterization

2.3. Photocatalytic Activity Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Photocatalyst

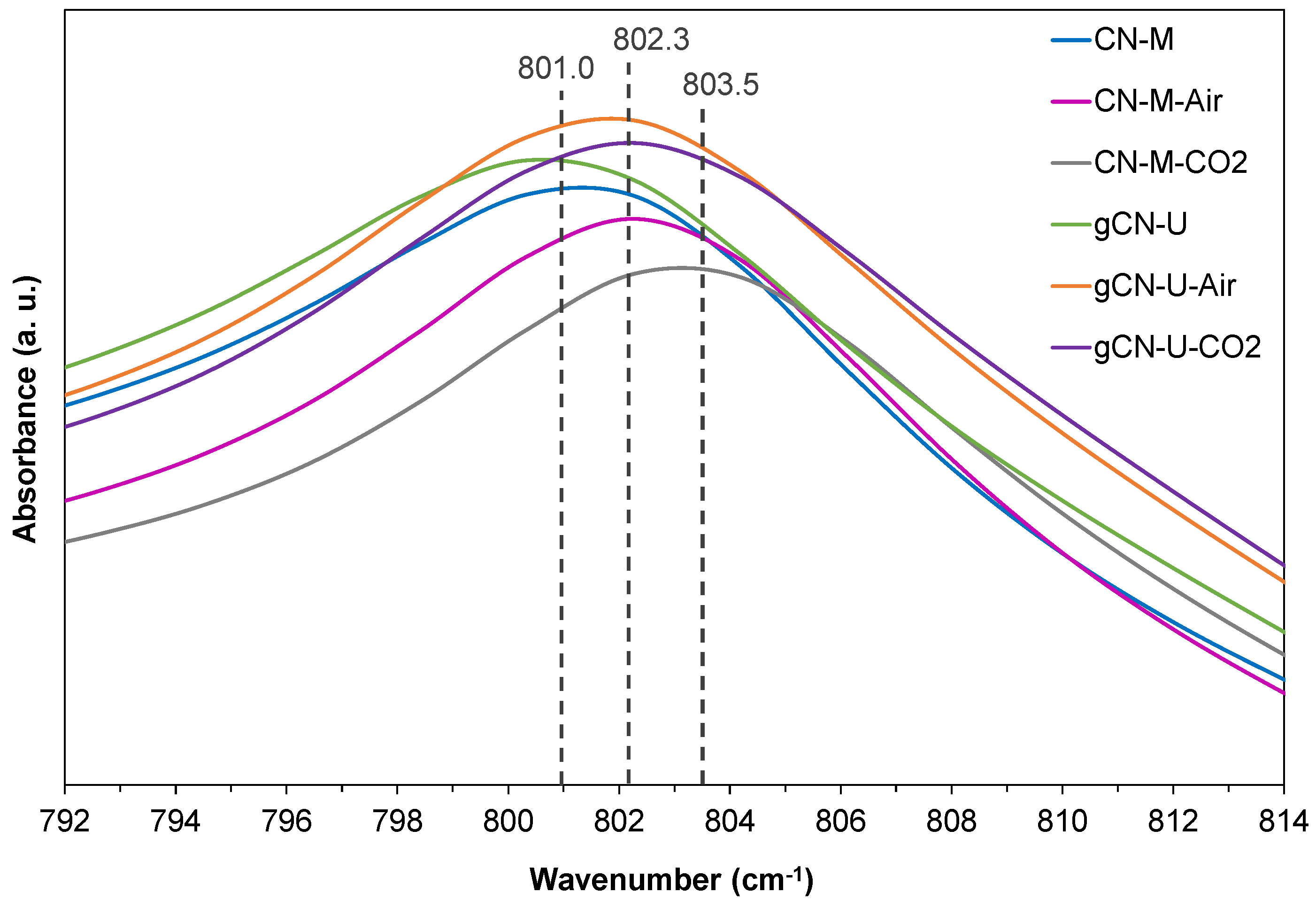

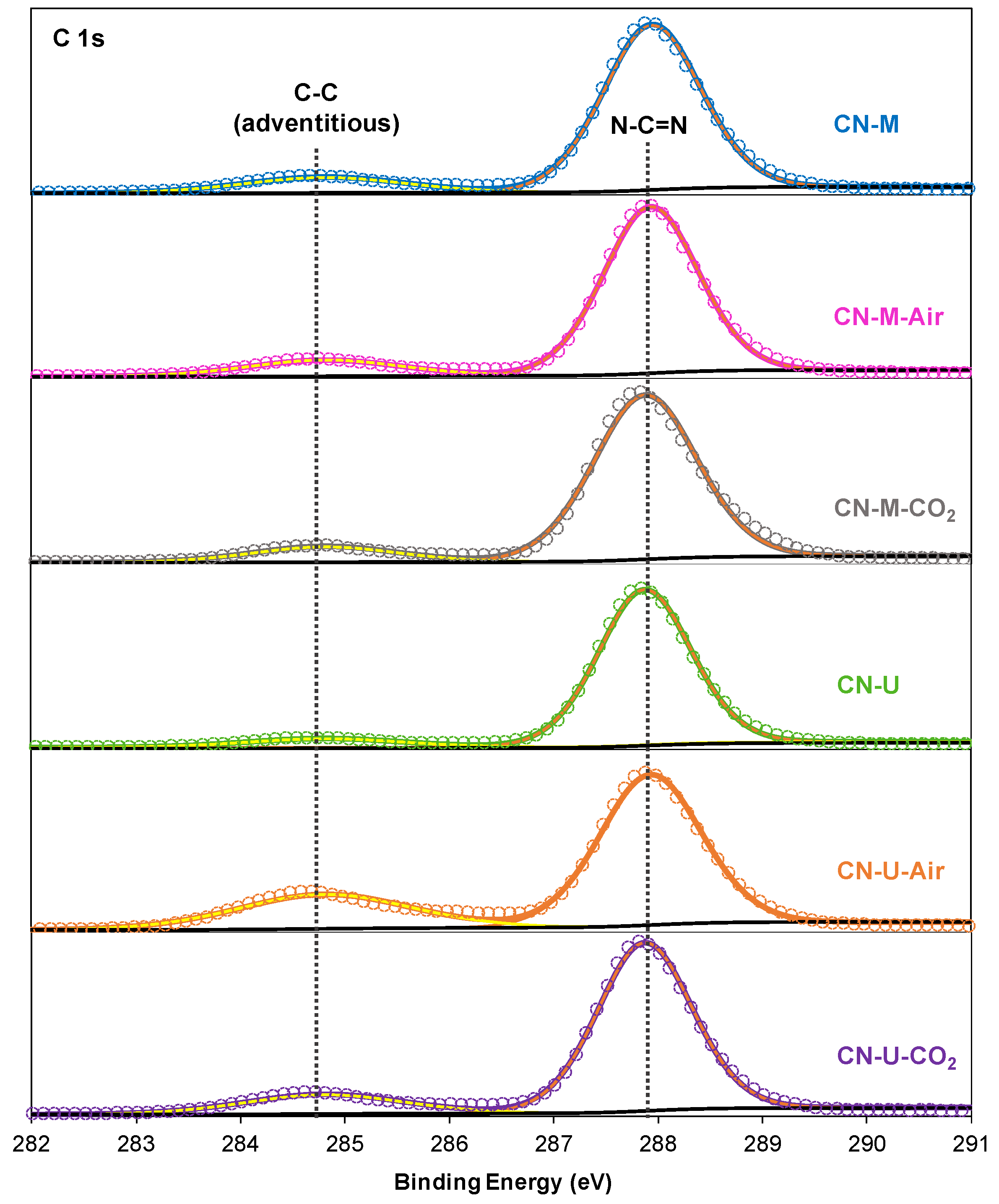

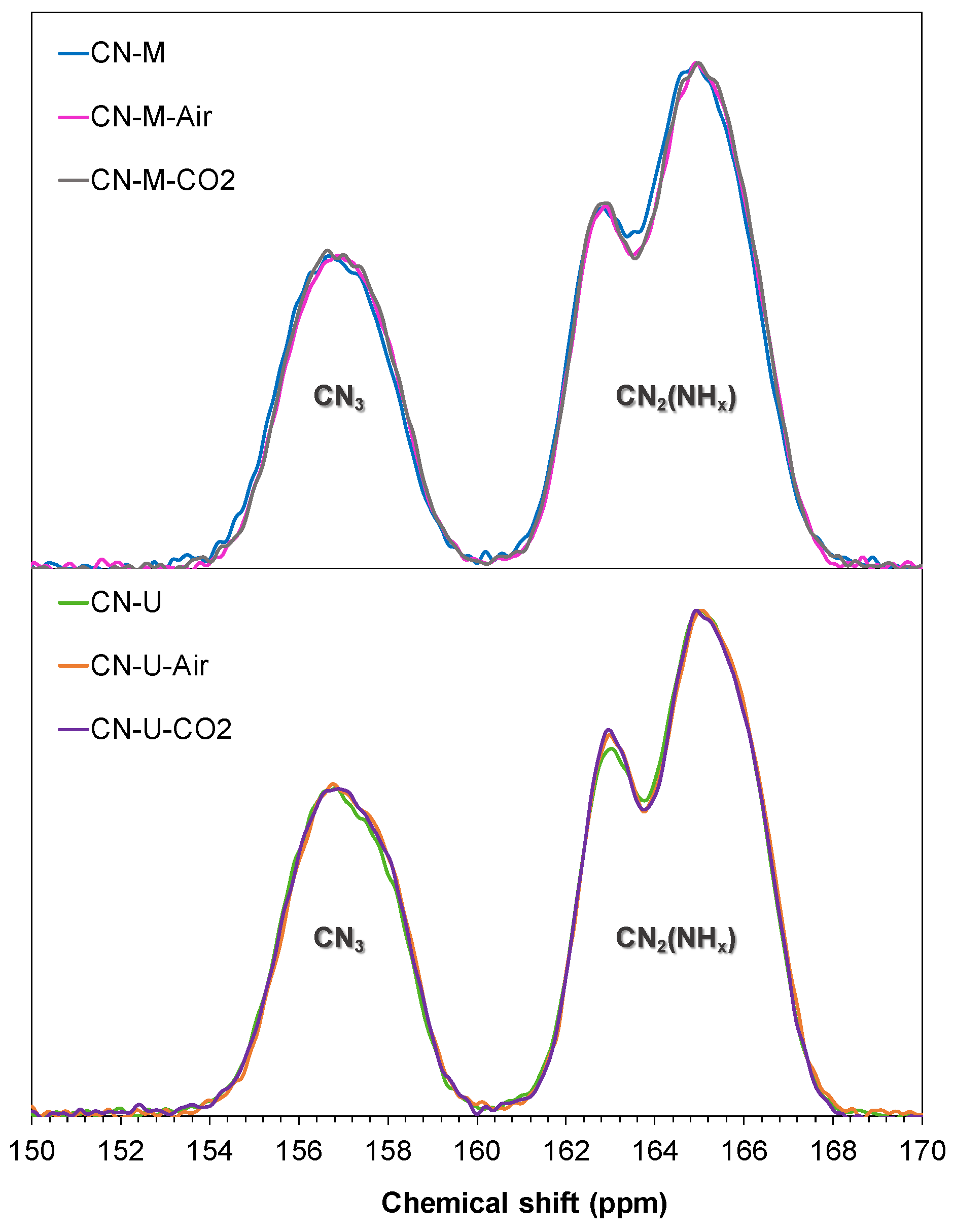

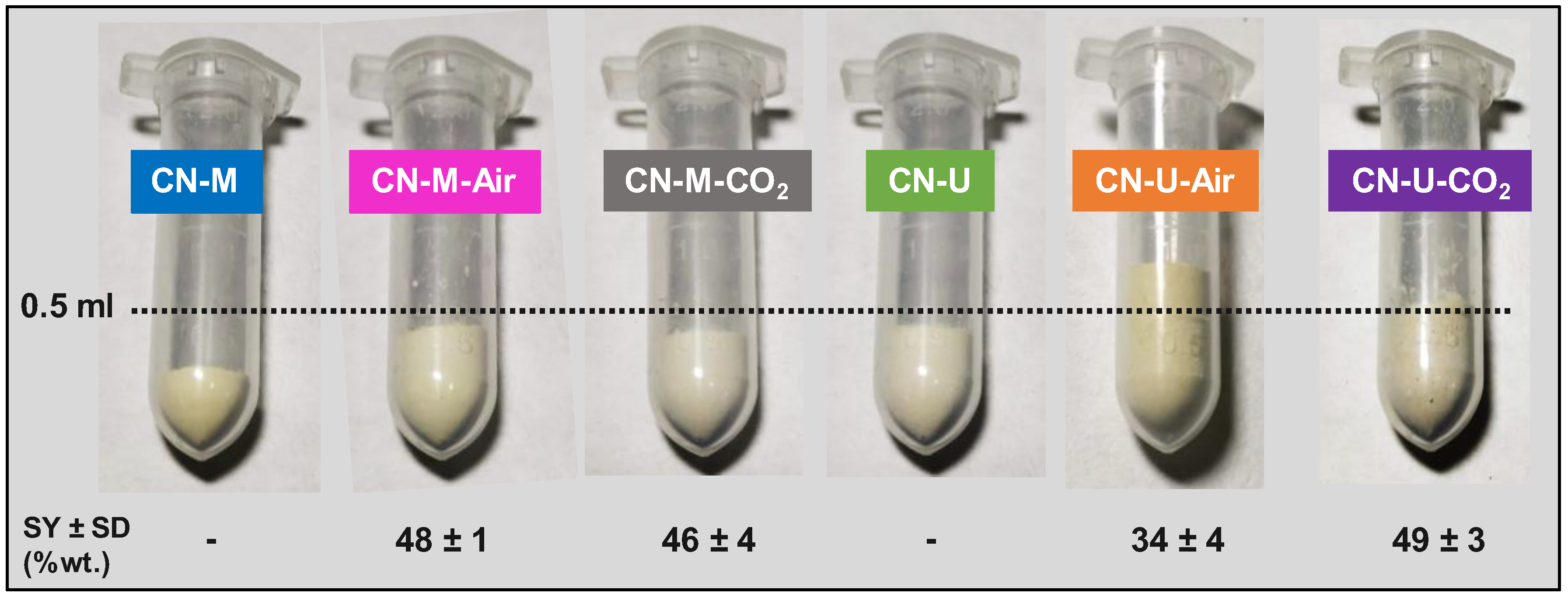

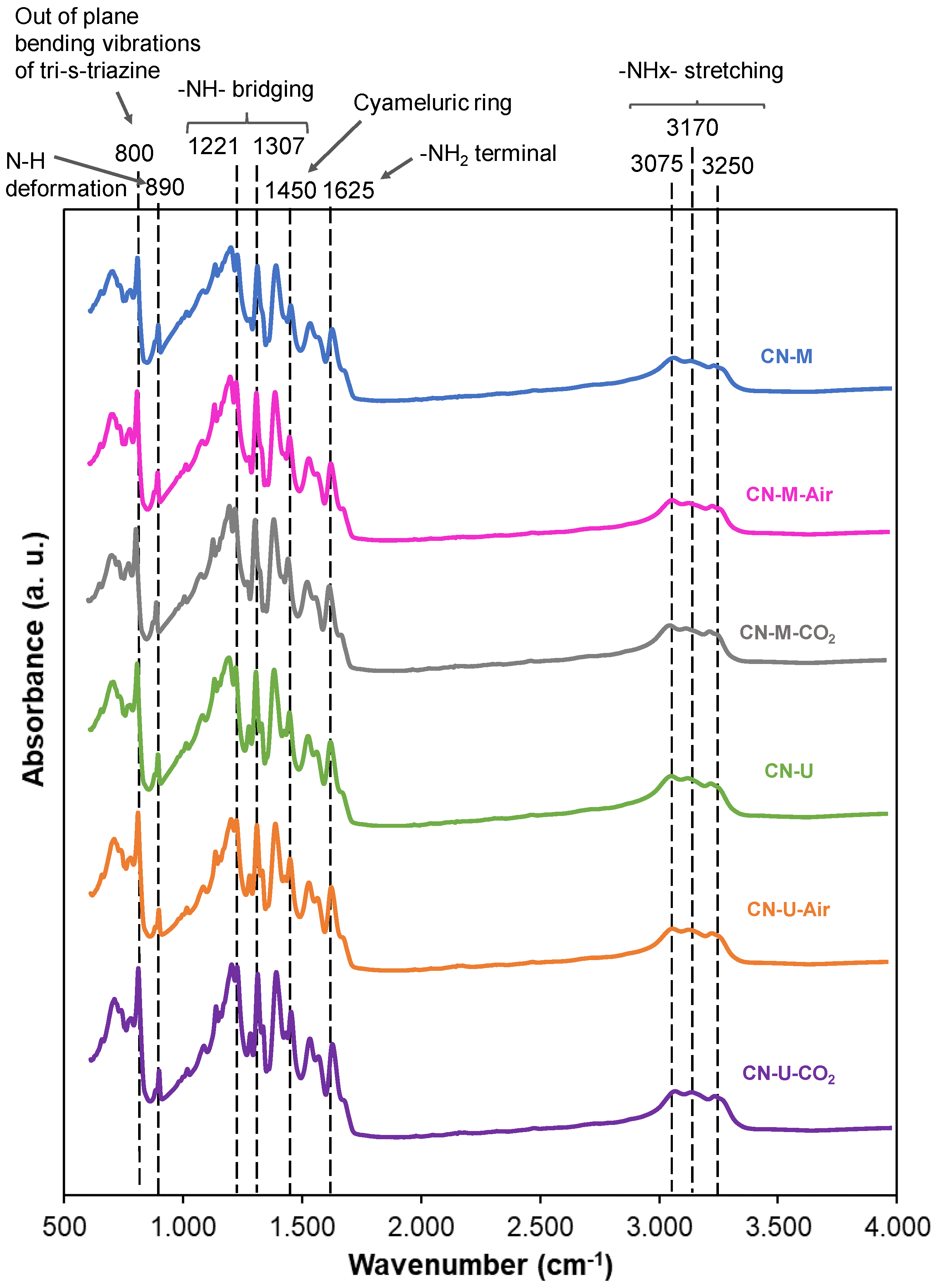

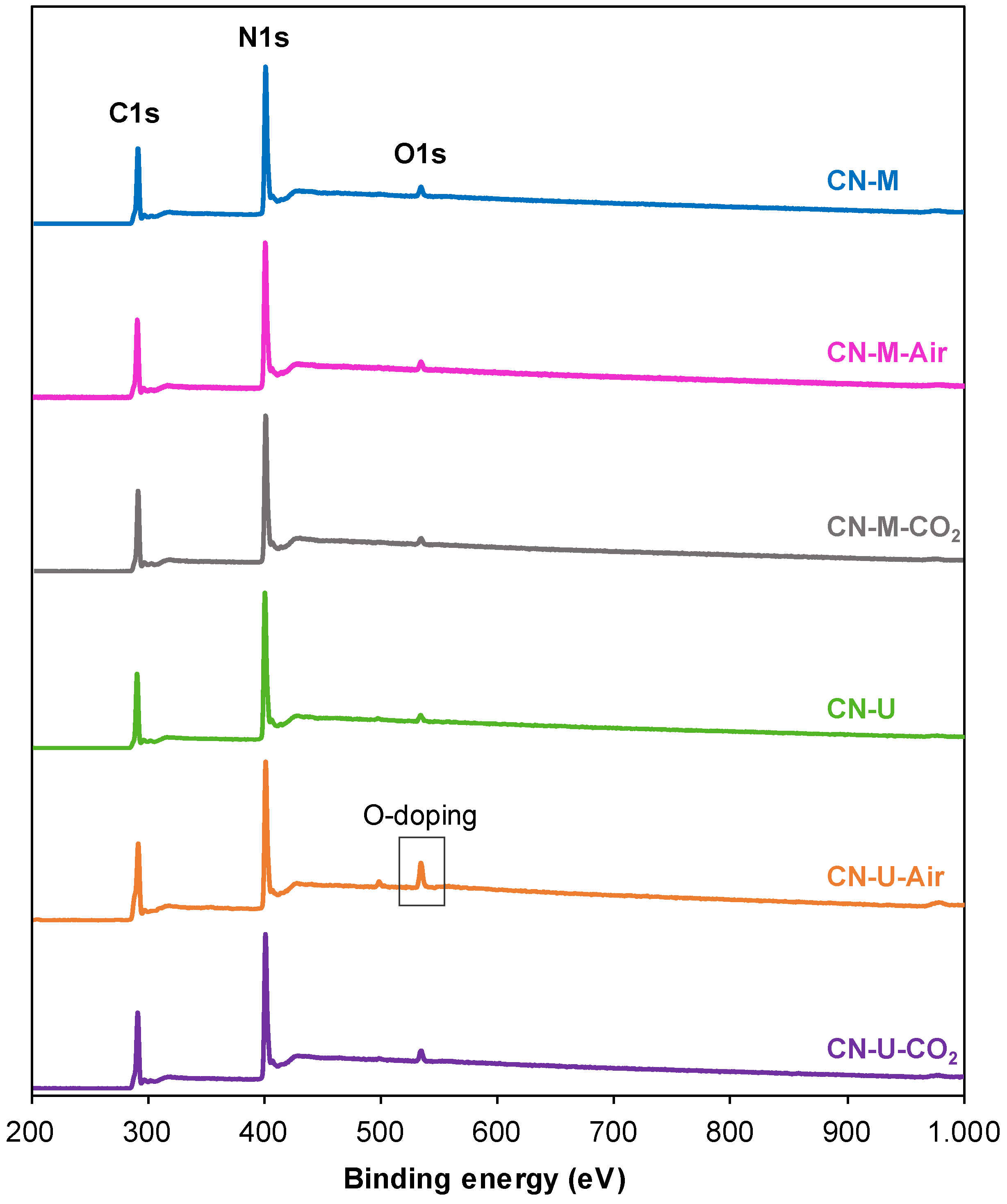

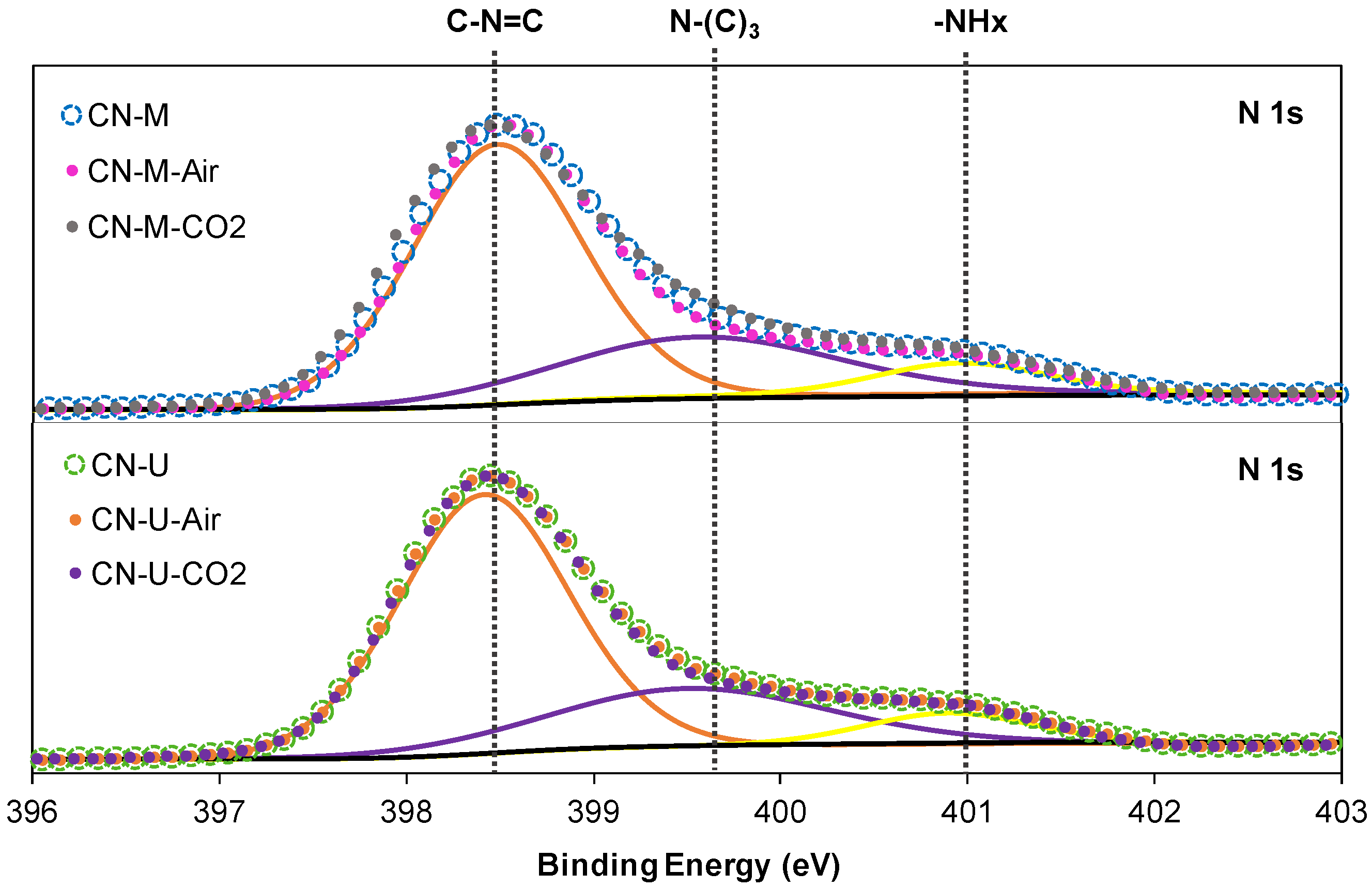

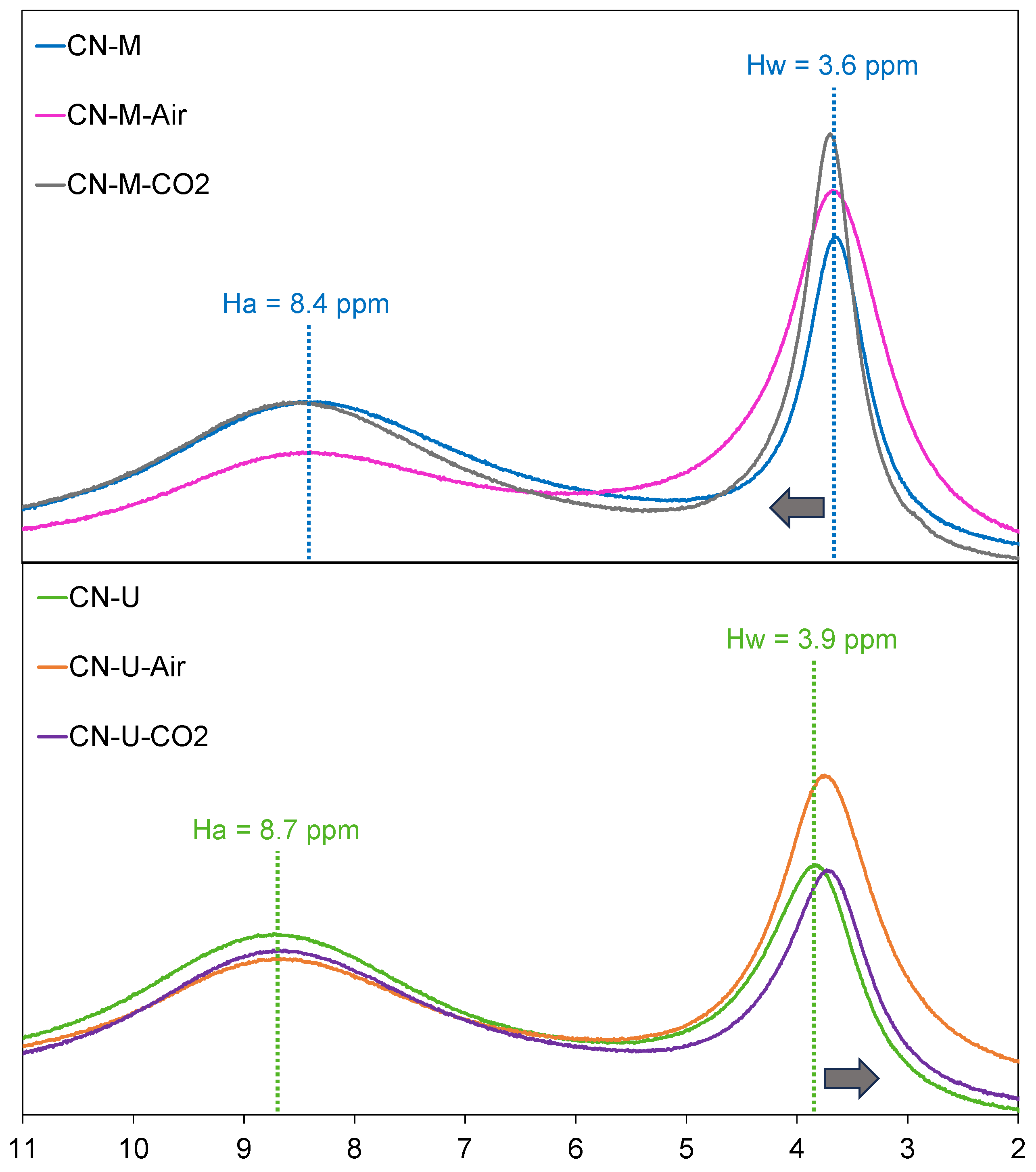

3.1.1. Chemical Structure Characterization (Elemental Analysis, FTIR, XPS and NMR)

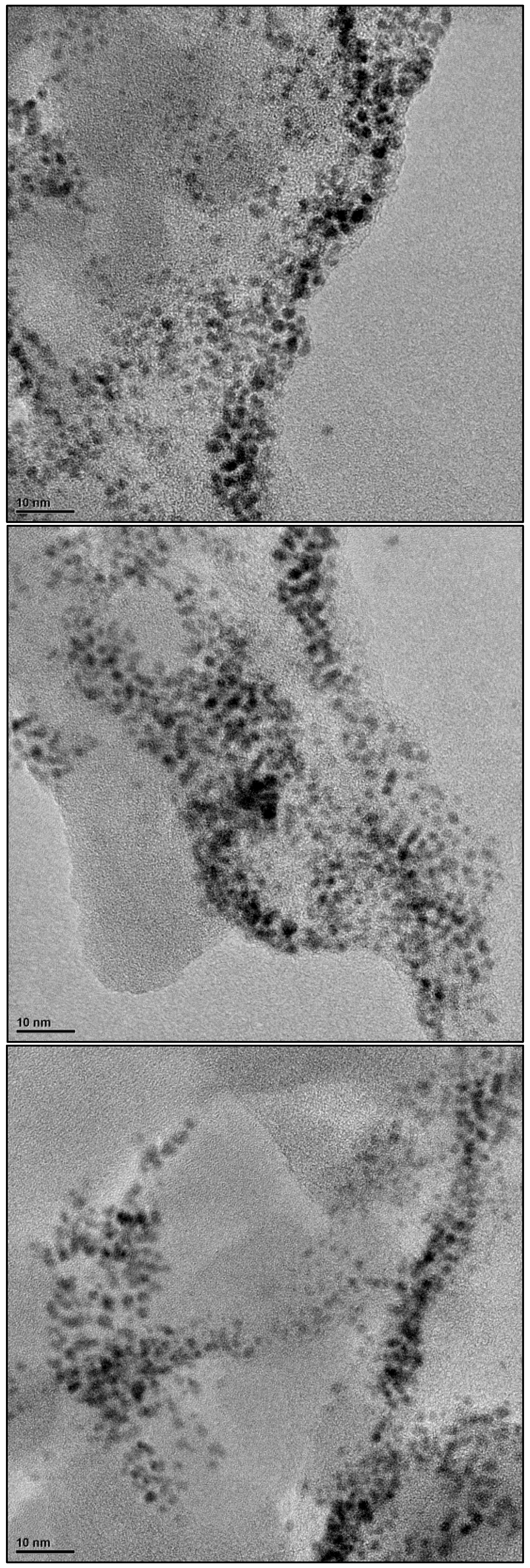

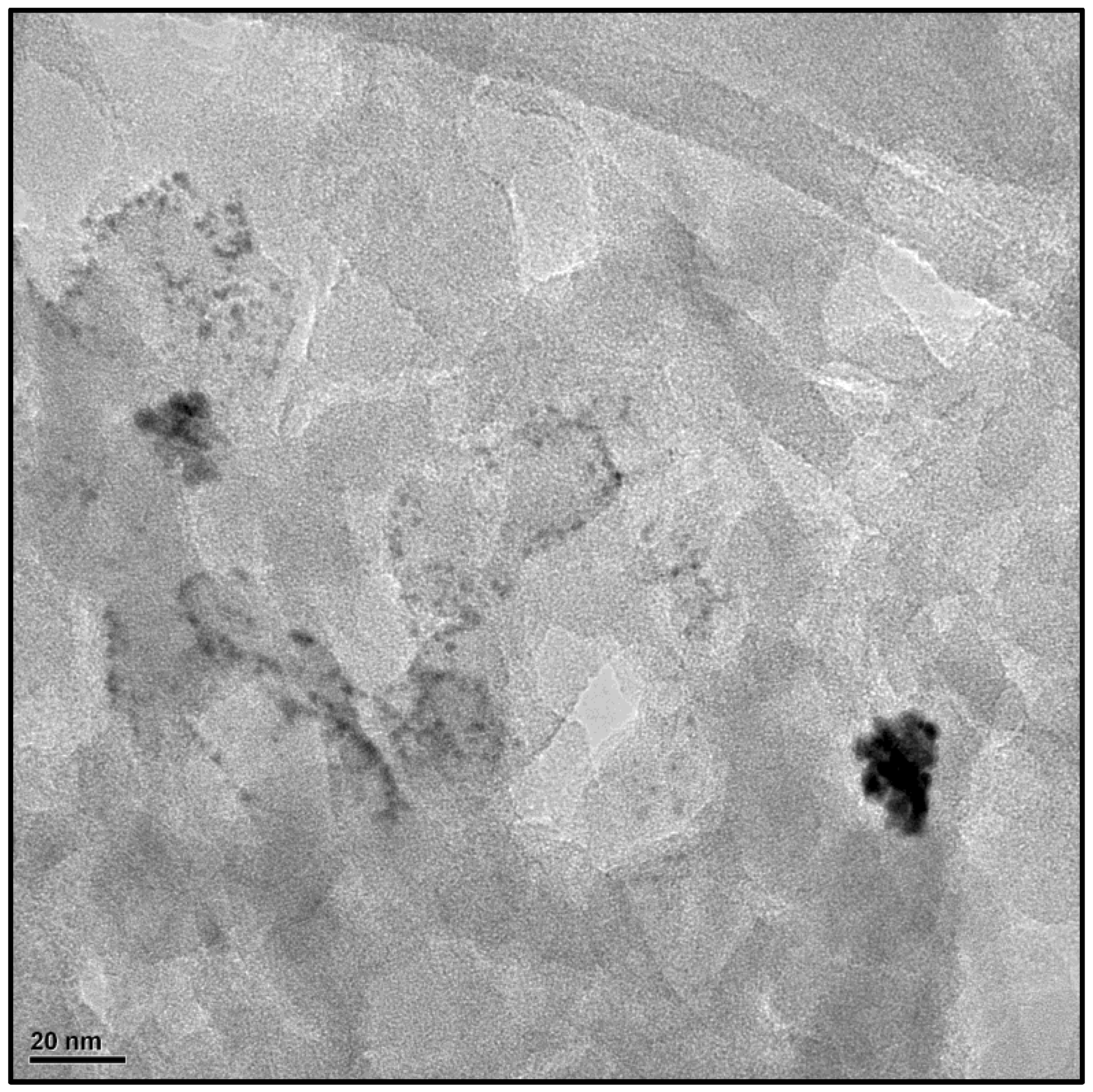

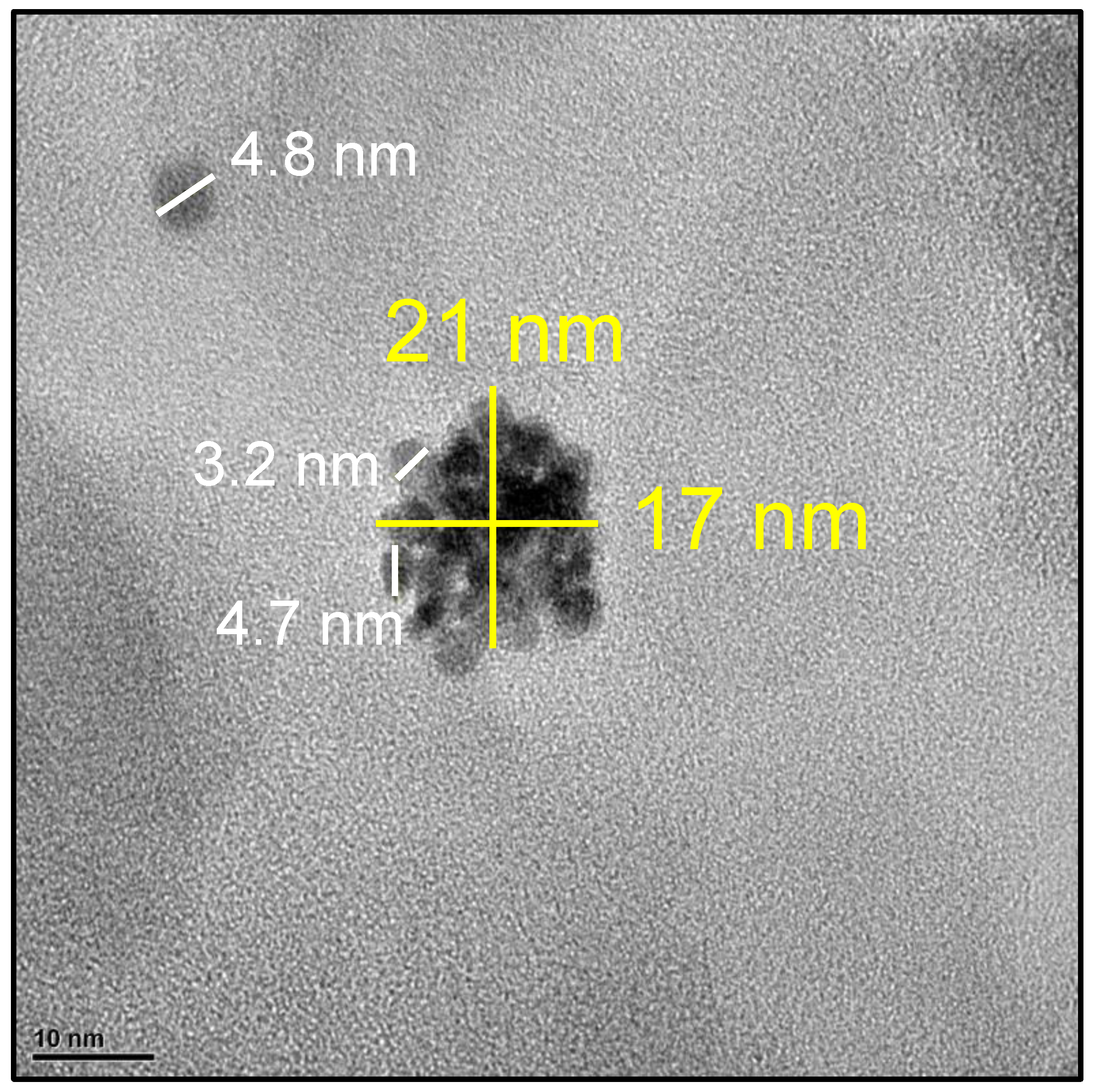

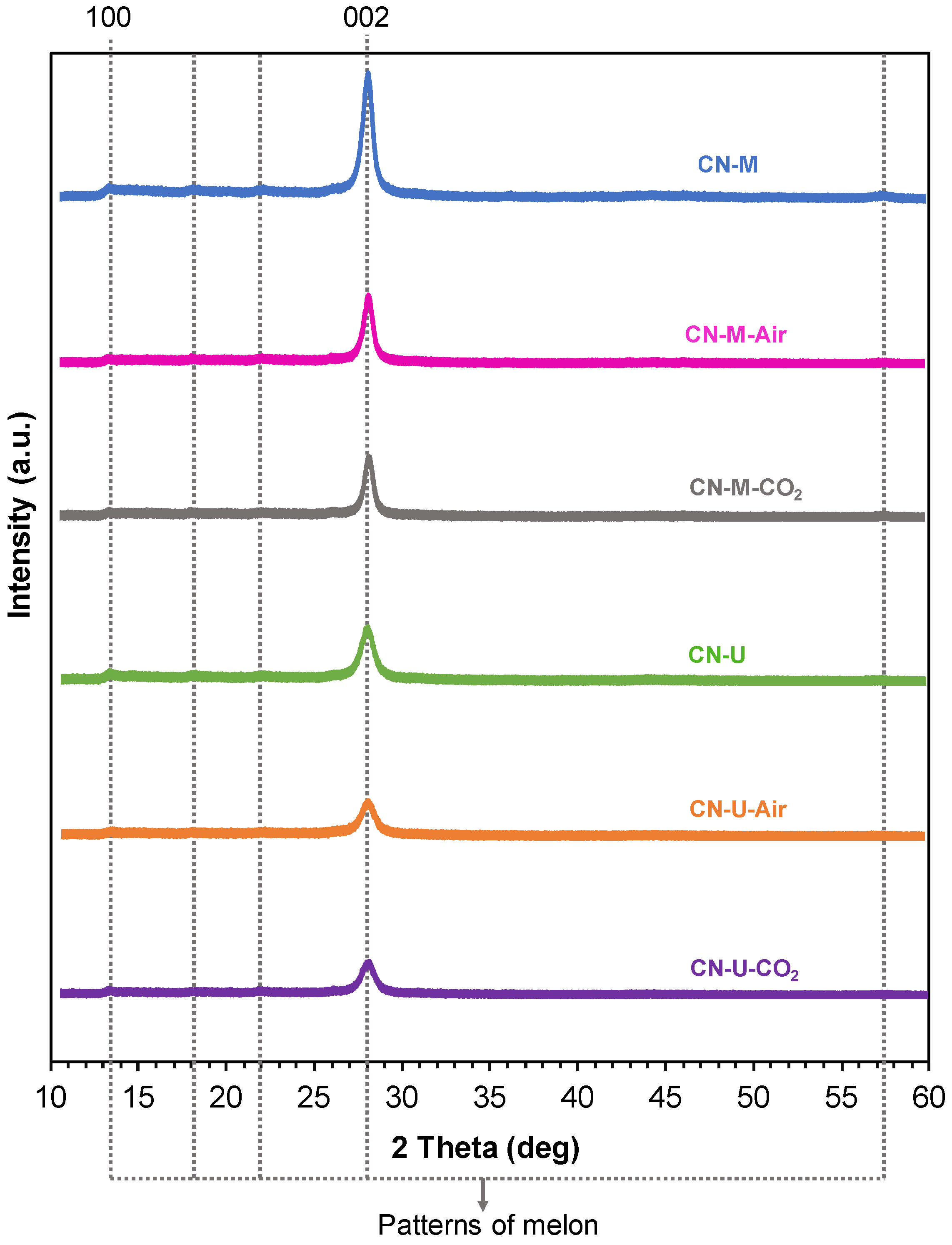

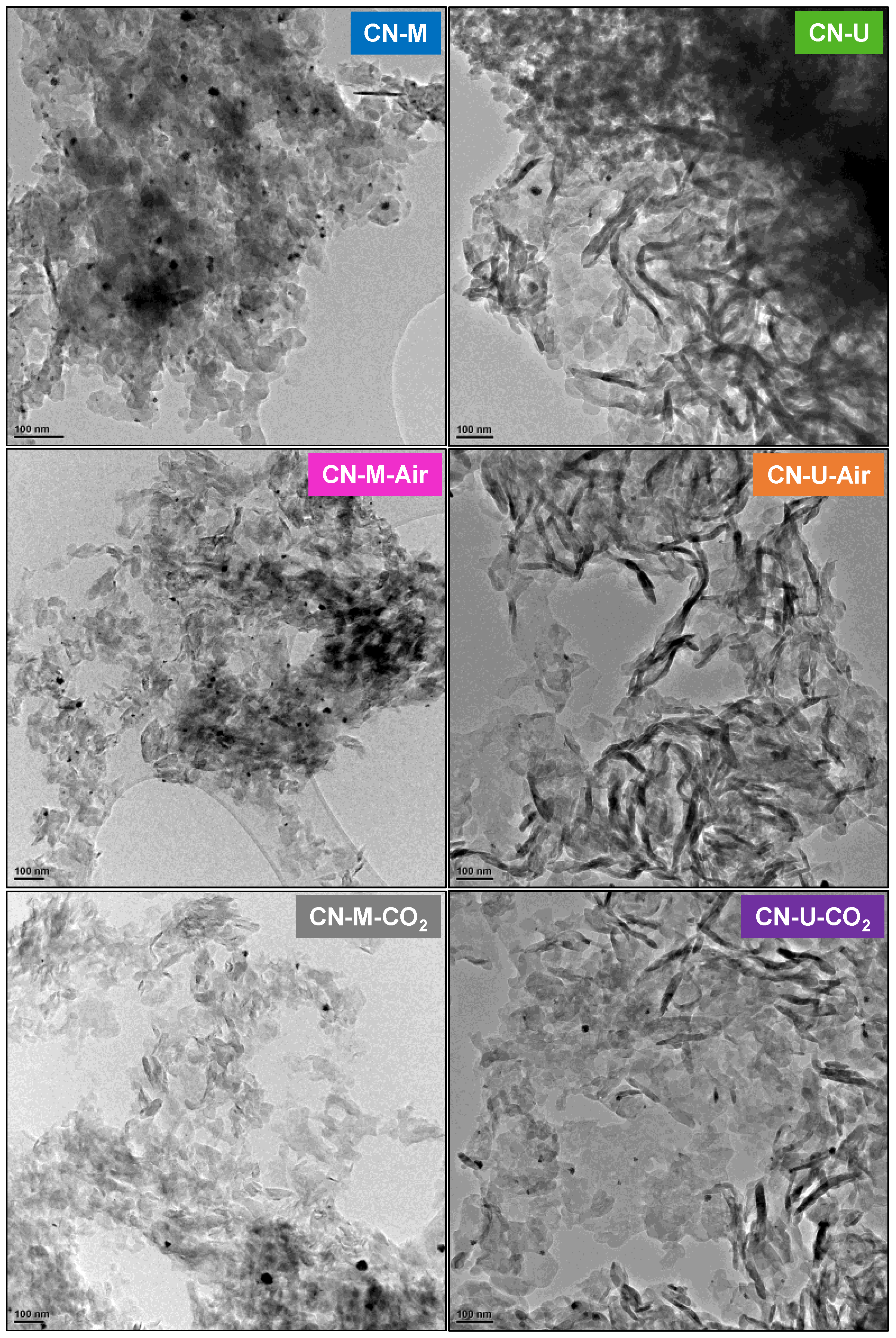

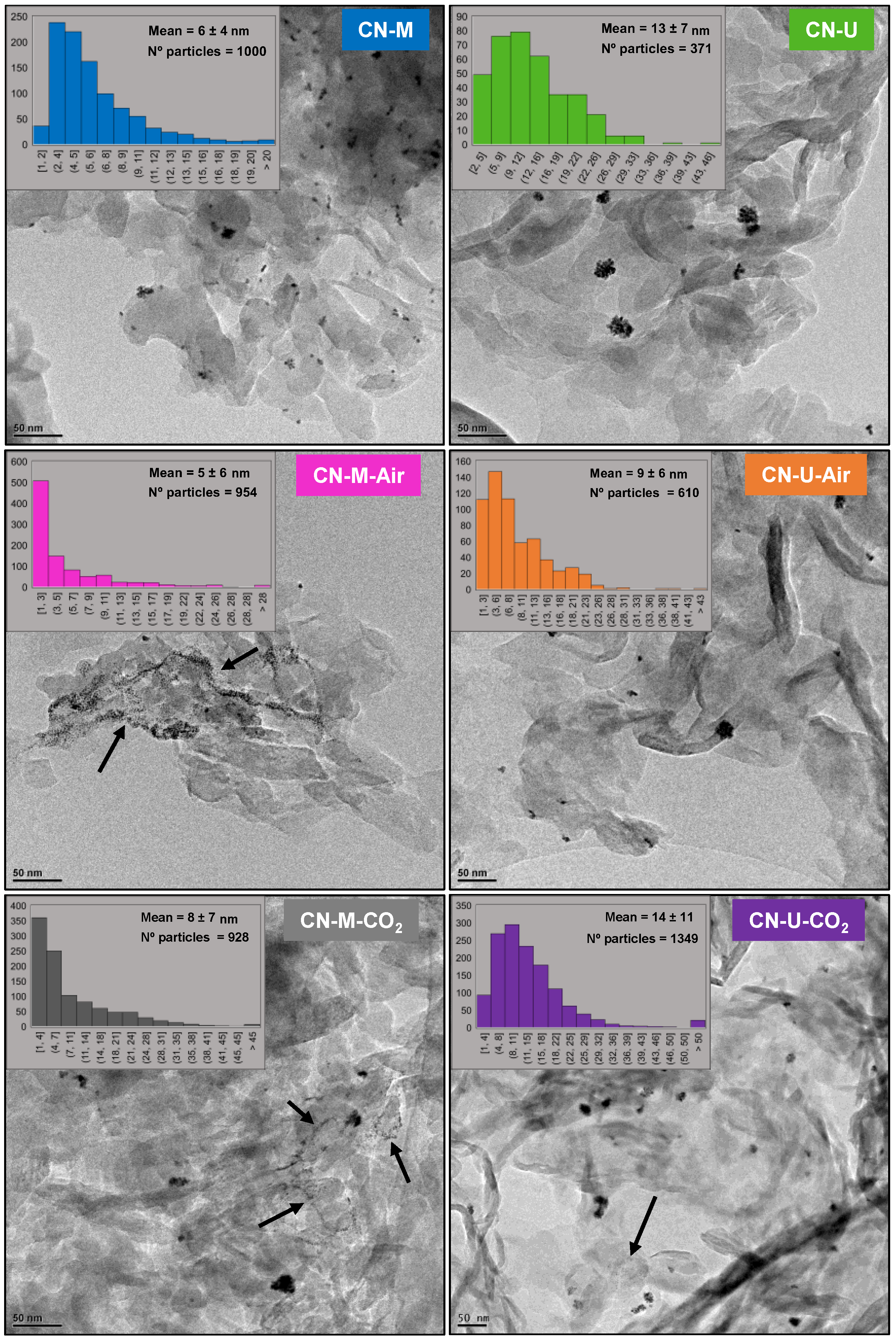

3.1.2. Structural and Textural Characterization (XRD, HRTEM and BET Area)

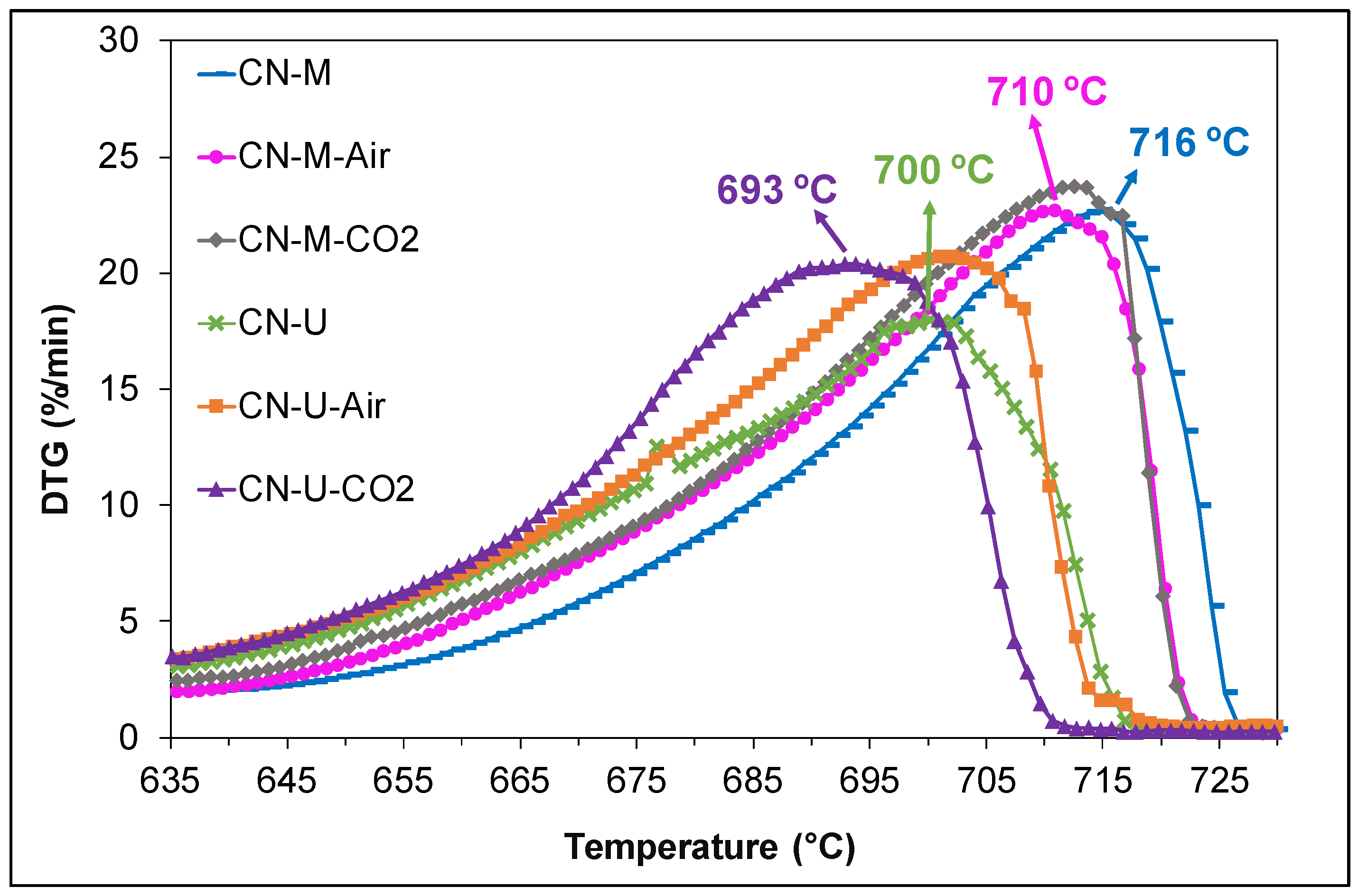

3.1.3. Thermal Stability (TGA)

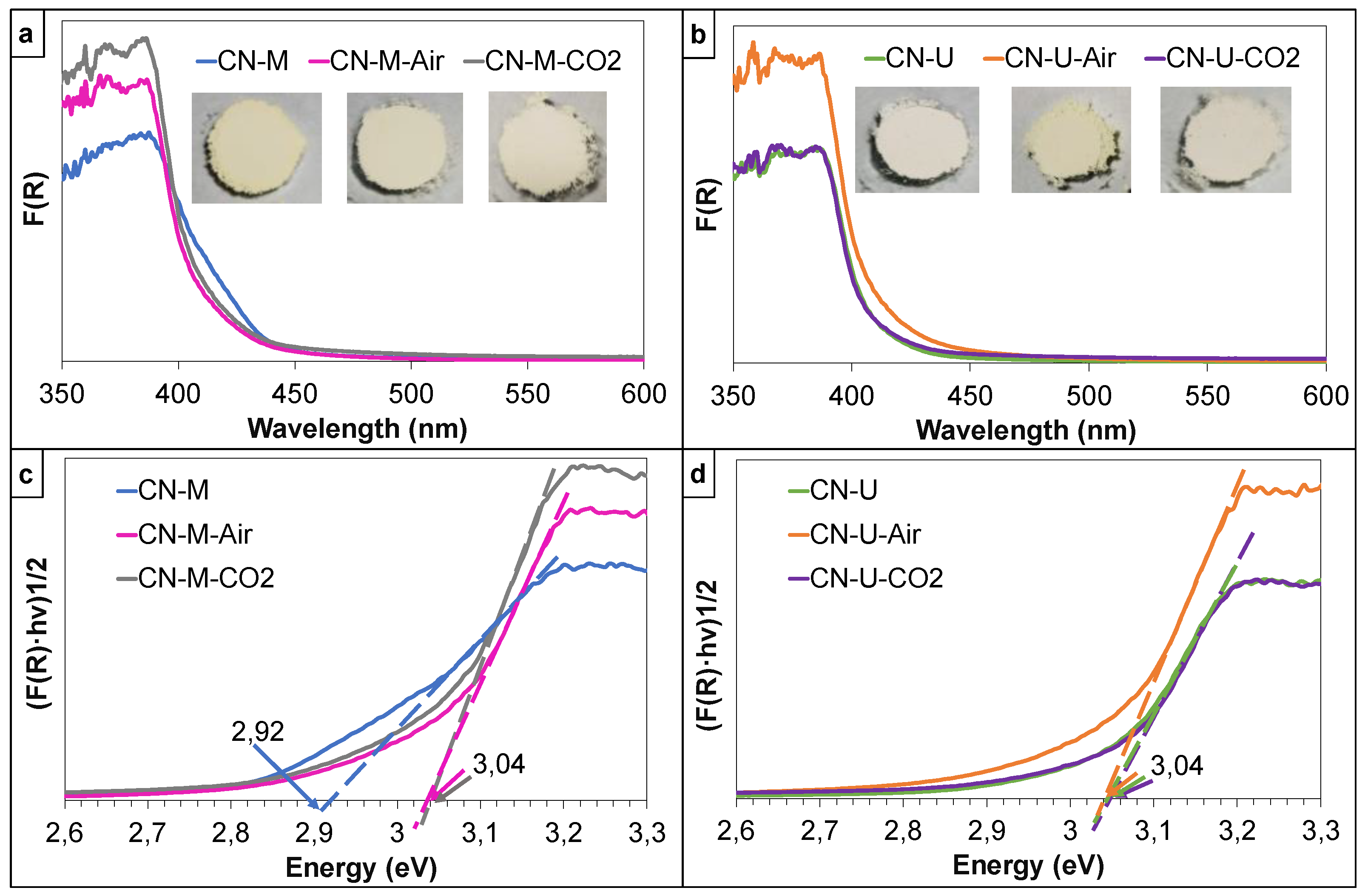

3.1.4. UV-VIS Absorption Properties

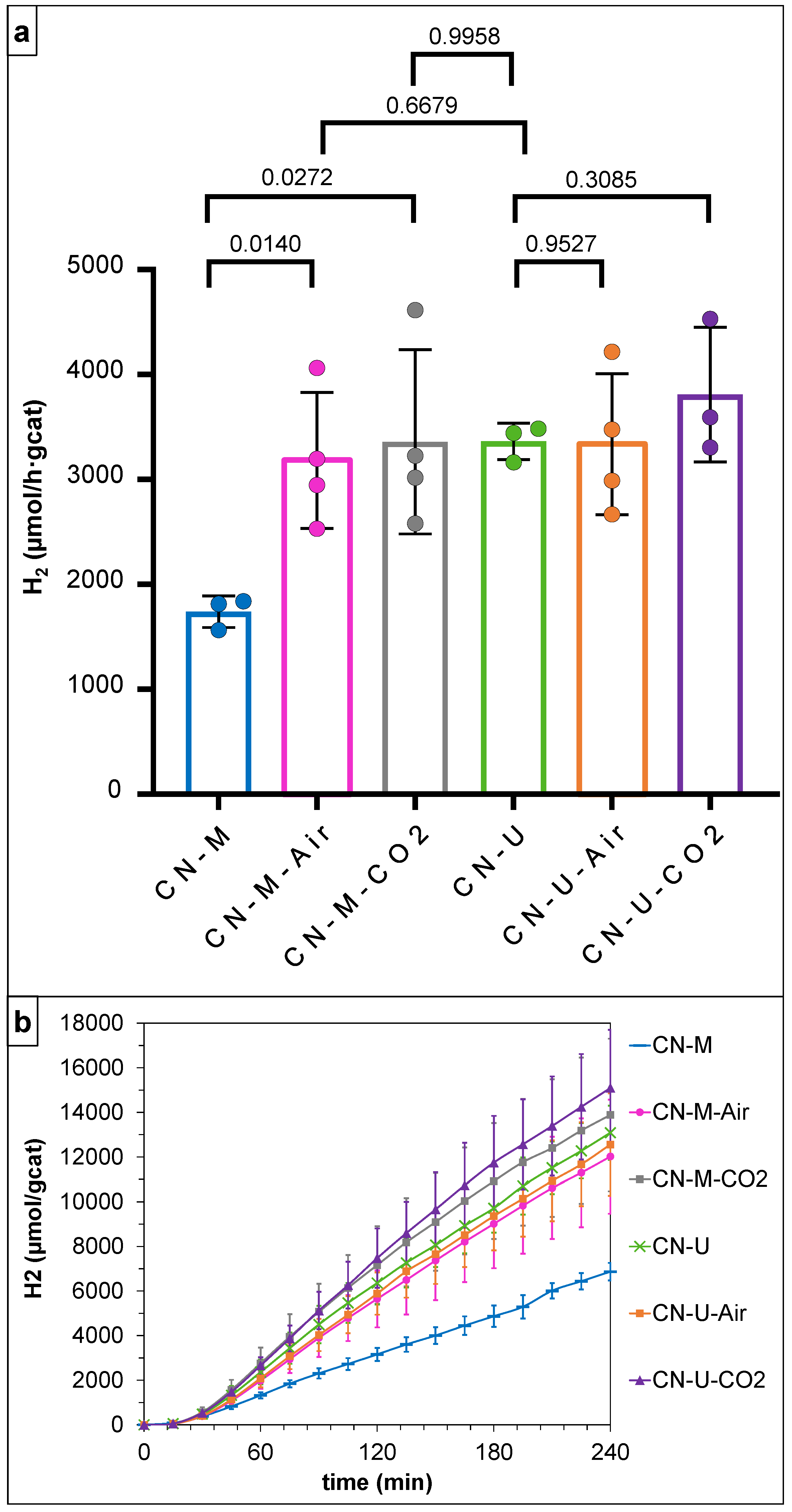

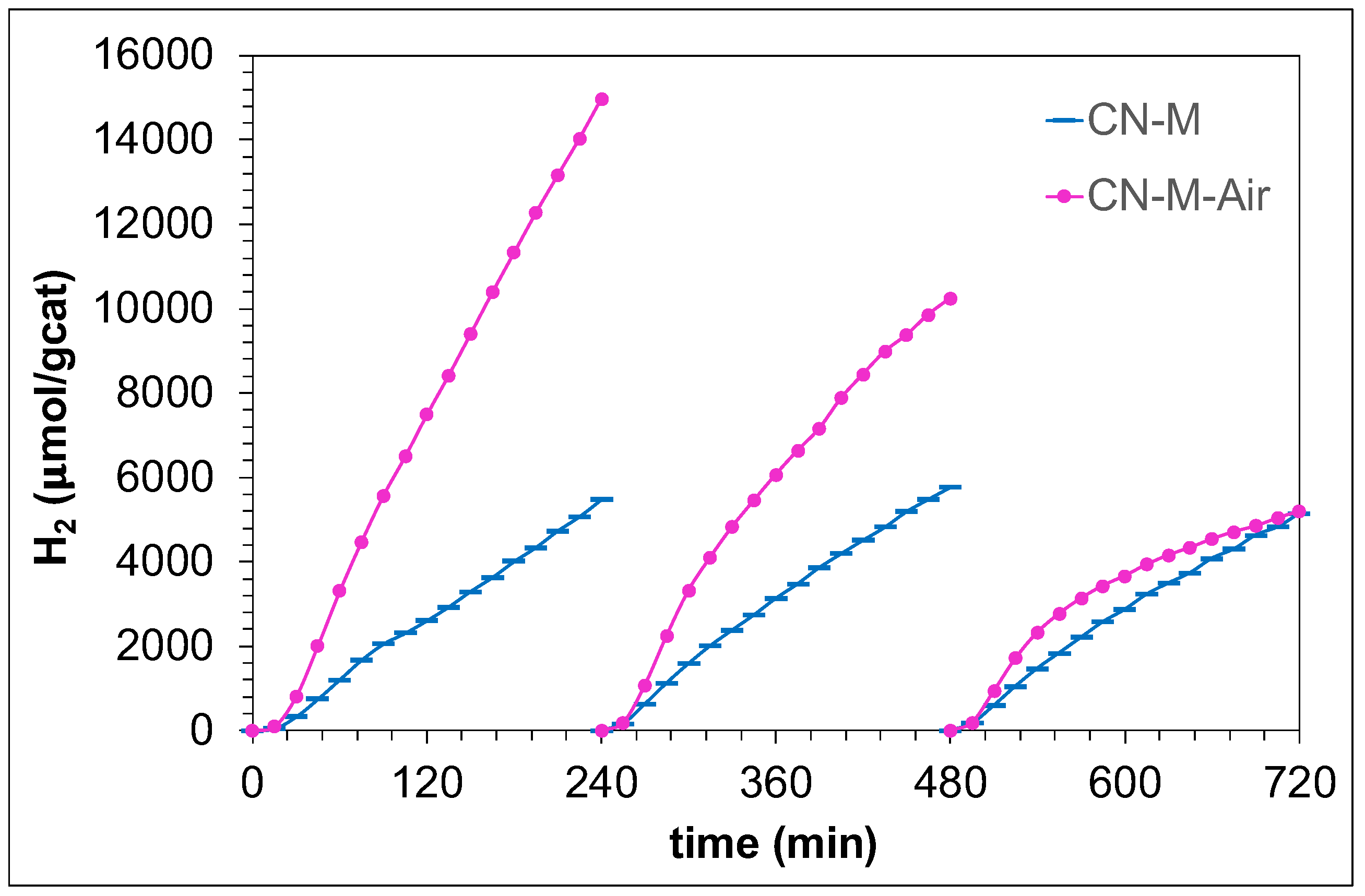

3.2. Photocatalytic H2 Production Activity

3.3. Correlation Between Structure Properties and the Photocatalytic Activity

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

| Precursor | Gas | Furnace SP (°C) | Dwell (min) | Pt (wt.%) | TEOA (vol.%) | Indicent light (nm) | HER (μmol/h·g) |

Impr. factor |

Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melamine | - | - | - | 3 | 13 | λ > 320 | 1739 | - | This work |

| Air | 580 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ > 320 | 3185 | 1.83 | This work | |

| CO2 | 580 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ > 320 | 3361 | 1.93 | This work | |

| Air | 540 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ > 320 | 4749 | 2.11 | Catal. Today (2024) [3] | |

| CO2 | 540 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ > 320 | 3896 | 1.77 | Catal. Today (2024) [3] | |

| Air | 520 | 270 | 3 | 12 | λ > 400 | 1508 | 11.7 | Adv. Energy Mater. (2016) [13] | |

| St. Air | 550 | 120 | 1 | 10 | λ > 420 | ~750 | 10 | Appl. Catal. B-Environ. (2018) [62] | |

| Urea | - | - | - | 3 | 13 | λ ≥ 320 | 3364 | - | This work |

| Air | 580 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ ≥ 320 | 3338 | 0.99 | This work | |

| CO2 | 580 | 120 | 3 | 13 | λ ≥ 320 | 3811 | 1.13 | This work | |

| N2 | 670 | 120 | 1.1 | 10 | λ > 420 | ~ 5000 | ~ 4 | Appl. Catal. B-Environ. (2022) [64] | |

| Dicyandiamide | Ar | 540 | 120 | 6 | 10 | λ ≥ 440 | ~ 150 | ~ 9 | Adv. Mater. (2016) [8] |

| Dicyandiamide | Ar | 620 | 120 | 3 | 10 | AM 1.5 λ ≥ 200 |

9.6 | 15.5 | Appl. Catal. B-Environ. (2018) [65] |

| Dicyandiamide | Air | 550 | 120 | 3 | 10 | λ > 400 | 2.0 | 12.5 | RSC Adv., (2020) [66] |

| Cyanamide | Air | 550 | 120 | 3 | 10 | visible light | 13.7 | 2.15 | Nanoscale, (2015) [67] |

References

- Florentino-Madiedo, L.; Díaz-Faes, E.; Barriocanal, C. Relationship between gCN Structure and Photocatalytic Water Splitting Efficiency. Carbon 2022, 187, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca, M.; Rychtowski, P.; Wróbel, R.; Mijowska, E.; Kaleńczuk, R.J.; Zielińska, B. Surface Properties Tuning of Exfoliated Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Multiple Photocatalytic Performance. Solar Energy 2020, 207, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, M.F.; Olivas, C.; Díaz-Faes, E.; Barriocanal, C. Evaluation of Water Splitting Efficiency of G-C3N4 Thermally Etched/Exfoliated under Air and CO2 Atmospheres. Catalysis Today 2024, 427, 114412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Shi, J.; Wen, L.; Dong, C.-L.; Huang, Y.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, S.; Diao, Z.; Shen, S.; Guo, L. Disordered Nitrogen-Defect-Rich Porous Carbon Nitride Photocatalyst for Highly Efficient H2 Evolution under Visible-Light Irradiation. Carbon 2021, 181, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustkhah, E. The Effects of Bandgap and Porosity on Catalysis and Materials Characteristics of Layered Carbon Nitrides. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 8415–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Zou, G.; Huang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, G.; Geng, D. Advances in Constructing Polymeric Carbon-Nitride-Based Nanocomposites and Their Applications in Energy Chemistry. Sustainable Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 611–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Liu, G.; Cheng, H.-M. Nitrogen Vacancy-Promoted Photocatalytic Activity of Graphitic Carbon Nitride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 11013–11018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yin, L.-C.; Kang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.; Cheng, H.-M. Selective Breaking of Hydrogen Bonds of Layered Carbon Nitride for Visible Light Photocatalysis. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 6471–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ho, W.; Lv, K.; Zhu, B.; Lee, S.C. Carbon Vacancy-Induced Enhancement of the Visible Light-Driven Photocatalytic Oxidation of NO over g-C3N4 Nanosheets. Applied Surface Science 2018, 430, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, B.; Hong, Z.; Lin, B.; Gao, B.; Chen, Y. A Facile Approach to Synthesize Novel Oxygen-Doped g-C3N4 with Superior Visible-Light Photoreactivity. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12017–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yin, L.-C.; Kang, X.; Liu, G.; Cheng, H.-M. An Amorphous Carbon Nitride Photocatalyst with Greatly Extended Visible-Light-Responsive Range for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Advanced Materials 2015, 27, 4572–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papailias, I.; Todorova, N.; Giannakopoulou, T.; Ioannidis, N.; Boukos, N.; Athanasekou, C.P.; Dimotikali, D.; Trapalis, C. Chemical vs Thermal Exfoliation of G-C3N4 for NOx Removal under Visible Light Irradiation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 239, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, R.; Xing, Y.; Li, J.; Song, S.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Jin, R. Macroscopic Foam-Like Holey Ultrathin g-C3N4 Nanosheets for Drastic Improvement of Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. Advanced Energy Materials 2016, 6, 1601273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, W.; Qiu, B.; Zhu, Q.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Self-Modified Breaking Hydrogen Bonds to Highly Crystalline Graphitic Carbon Nitrides Nanosheets for Drastically Enhanced Hydrogen Production. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 232, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, R.; Han, P.; Hou, B.; Peng, S.; Ouyang, C. A New Concept: Volume Photocatalysis for Efficient H2 Generation __ Using Low Polymeric Carbon Nitride as an Example. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020, 279, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Cheng, H.-M. Graphene-Like Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Improved Photocatalytic Activities. Advanced Functional Materials 2012, 22, 4763–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Li, L.; An, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Microstructure of Carbon Nitride Affecting Synergetic Photocatalytic Activity: Hydrogen Bonds vs. Structural Defects. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 204, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B. Band-Gap Determination from Diffuse Reflectance Measurements of Semiconductor Films, and Application to Photoelectrochemical Water-Splitting. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2007, 91, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fujitsuka, M.; Kim, S.; Wang, Z.; Majima, T. Unprecedented Effect of CO2 Calcination Atmosphere on Photocatalytic H2 Production Activity from Water Using G-C3N4 Synthesized from Triazole Polymerization. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2019, 241, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Fan, J.; Xue, Y.; Chang, H.; Masubuchi, Y.; Yin, S. Synthesis of Graphitic Carbon Nitride from Different Precursors by Fractional Thermal Polymerization Method and Their Visible Light Induced Photocatalytic Activities. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 735, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T. The First Synthesis and Characterization of Cyameluric High Polymers. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2001, 202, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, V.W.; Moudrakovski, I.; Botari, T.; Weinberger, S.; Mesch, M.B.; Duppel, V.; Senker, J.; Blum, V.; Lotsch, B.V. Rational Design of Carbon Nitride Photocatalysts by Identification of Cyanamide Defects as Catalytically Relevant Sites. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotsch, B.V.; Döblinger, M.; Sehnert, J.; Seyfarth, L.; Senker, J.; Oeckler, O.; Schnick, W. Unmasking Melon by a Complementary Approach Employing Electron Diffraction, Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy, and Theoretical Calculations—Structural Characterization of a Carbon Nitride Polymer. Chemistry – A European Journal 2007, 13, 4969–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, S.; Wang, N.; Zou, Z. High-Yield Synthesis of Millimetre-Long, Semiconducting Carbon Nitride Nanotubes with Intense Photoluminescence Emission and Reproducible Photoconductivity. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3687–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, D.; Silva, M.; Silva, L. Assessment of Reaction Parameters in the Polymeric Carbon Nitride Thermal Synthesis and the Influence in Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Fang, W.Q.; Wang, H.F.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.G. Surface Hydrogen Bonding Can Enhance Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 14089–14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.-P.; Wang, L.-C.; Luo, J.; Nie, Y.-C.; Xing, Q.-J.; Luo, X.-B.; Du, H.-M.; Luo, S.-L.; Suib, S.L. Synthesis and Efficient Visible Light Photocatalytic H2 Evolution of a Metal-Free g-C3N4/Graphene Quantum Dots Hybrid Photocatalyst. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2016, 193, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, B.; Irran, E.; Senker, J.; Kroll, P.; Müller, H.; Schnick, W. Melem (2,5,8-Triamino-Tri-s-Triazine), an Important Intermediate during Condensation of Melamine Rings to Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Synthesis, Structure Determination by X-Ray Powder Diffractometry, Solid-State NMR, and Theoretical Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10288–10300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Selective Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange in Graphitic Carbon Nitrides: Probing the Active Sites for Photocatalytic Water Splitting by Solid-State NMR. Journal of materials chemistry A 2021, v. 9, 3985–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-Q.; Xiao, Y.-H.; Yu, Y.-X.; Zhang, W.-D. The Role of Hydrogen Bonding on Enhancement of Photocatalytic Activity of the Acidified Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Hydrogen Evolution. Journal of Materials Science 2018, 53, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sergeyev, I.V.; Aussenac, F.; Masters, A.F.; Maschmeyer, T.; Hook, J.M. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR Spectroscopy of Polymeric Carbon Nitride Photocatalysts: Insights into Structural Defects and Reactivity. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018, 57, 6848–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trébosc, J.; Wiench, J.W.; Huh, S.; Lin, V.S.-Y.; Pruski, M. Solid-State NMR Study of MCM-41-Type Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Fang, W.Q.; Wang, H.F.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.G. Surface Hydrogen Bonding Can Enhance Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 14089–14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Vorobyeva, E.; Mitchell, S.; Fako, E.; López, N.; Collins, S.M.; Leary, R.K.; Midgley, P.A.; Hauert, R.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Single-Atom Heterogeneous Catalysts Based on Distinct Carbon Nitride Scaffolds. National Science Review 2018, 5, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyborski, T.; Merschjann, C.; Orthmann, S.; Yang, F.; Lux-Steiner, M.-C.; Schedel-Niedrig, T. Crystal Structure of Polymeric Carbon Nitride and the Determination of Its Process-Temperature-Induced Modifications. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2013, 25, 395402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, F.; Callear, S.K.; Carins, G.M.; Irvine, J.T.S. Structural Investigation of Graphitic Carbon Nitride via XRD and Neutron Diffraction. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 2612–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Si, Y.; Zhou, B.-X.; Fang, Q.; Li, Y.-Y.; Huang, W.-Q.; Hu, W.; Pan, A.; Fan, X.; Huang, G.-F. Doping-Induced Hydrogen-Bond Engineering in Polymeric Carbon Nitride To Significantly Boost the Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17341–17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, P.; Li, S.; Guo, H.; Hu, X.; Fang, Y.; Duan, R.; Chen, Q. Synthesis of Nitrogen Vacancy-Riched Ultrathin Polymeric Carbon Nitride Nanosheets via Ethanol-Ethylene Glycol Ultrasonic Exfoliation and Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Activity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 676, 132113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Ou, M.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, S.; Wu, Z. Efficient and Durable Visible Light Photocatalytic Performance of Porous Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Air Purification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 2318–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Calvo, P.; Marchal, C.; Cottineau, T.; Caps, V.; Keller, V. Influence of the Gas Atmosphere during the Synthesis of G-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Production from Water on Au/g-C3N4 Composites. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 14849–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Yang, D.; Xiao, T.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, Z. Biomimetic Fabrication of G-C3N4/TiO2 Nanosheets with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity toward Organic Pollutant Degradation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 260, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, J.M.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, J.; Hwang, S.-J.; Park, S. New Insight of the Photocatalytic Behaviors of Graphitic Carbon Nitrides for Hydrogen Evolution and Their Associations with Grain Size, Porosity, and Photophysical Properties. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 218, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devthade, V.; Kulhari, D.; Umare, S.S. Role of Precursors on Photocatalytic Behavior of Graphitic Carbon Nitride. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 9203–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C. A Comparison of Graphitic Carbon Nitrides Synthesized from Different Precursors through Pyrolysis. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2017, 332, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, S.; Nashim, A.; Parida, K.M. Facile Synthesis of Highly Active G-C3N4 for Efficient Hydrogen Production under Visible Light. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 7816–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.S.; Jorge, A.B.; Suter, T.M.; Sella, A.; Corà, F.; McMillan, P.F. Carbon Nitrides: Synthesis and Characterization of a New Class of Functional Materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 15613–15638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Diez-Cabanes, V.; Fan, D.; Peng, L.; Fang, Y.; Antonietti, M.; Maurin, G. Tailoring Metal-Ion-Doped Carbon Nitrides for Photocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 2562–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.J.; Qiu, K.; Shevlin, S.A.; Handoko, A.D.; Chen, X.; Guo, Z.; Tang, J. Highly Efficient Photocatalytic H2 Evolution from Water Using Visible Light and Structure-Controlled Graphitic Carbon Nitride. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2014, 53, 9240–9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.-Q.; Bao, S.-J.; Lu, S.; Xu, M.; Long, D.; Pu, S. Tuning and Thermal Exfoliation Graphene-like Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Superior Photocatalytic Activity. Ceramics International 2016, 42, 18521–18528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Raizada, P.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Thakur, V.K.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Singh, P. C-, N-Vacancy Defect Engineered Polymeric Carbon Nitride towards Photocatalysis: Viewpoints and Challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 111–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Calvo, P.; Marchal, C.; Cottineau, T.; Caps, V.; Keller, V. Influence of the Gas Atmosphere during the Synthesis of G-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Production from Water on Au/g-C3N4 Composites. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 14849–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Activation of n → Π* Transitions in Two-Dimensional Conjugated Polymers for Visible Light Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 29981–29989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, F.; Zhao, Z. The Multiple Effects of Precursors on the Properties of Polymeric Carbon Nitride. International Journal of Photoenergy 2013, 2013, 685038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, S.-P. Band Gap of C3N4 in the GW Approximation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 11072–11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; White, E.R.; Clancy, A.J.; Rubio, N.; Suter, T.; Miller, T.S.; McColl, K.; McMillan, P.F.; Brázdová, V.; Corà, F.; et al. Fast Exfoliation and Functionalisation of Two-Dimensional Crystalline Carbon Nitride by Framework Charging. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018, 57, 12656–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savateev, A.; Pronkin, S.; Epping, J.D.; Willinger, M.G.; Wolff, C.; Neher, D.; Antonietti, M.; Dontsova, D. Potassium Poly(Heptazine Imides) from Aminotetrazoles: Shifting Band Gaps of Carbon Nitride-like Materials for More Efficient Solar Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidhambaram, N.; Ravichandran, K. Single Step Transformation of Urea into Metal-Free g-C3N4 Nanoflakes for Visible Light Photocatalytic Applications. Materials Letters 2017, 207, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Dong, G.; Ho, W. Construction and Activity of an All-Organic Heterojunction Photocatalyst Based on Melem and Pyromellitic Dianhydride. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liang, S. Recent Advances in Functional Mesoporous Graphitic Carbon Nitride (Mpg-C3N4) Polymers. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10544–10578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, S.; Lu, G.; Li, S. Eosin Y-Sensitized Graphitic Carbon Nitride Fabricated by Heating Urea for Visible Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution: The Effect of the Pyrolysis Temperature of Urea. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 7657–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ge, F.; Yan, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, H. Synthesis of Carbon Nitride in Moist Environments: A Defect Engineering Strategy toward Superior Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2021, 54, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Song, R.; Geng, J.; Jing, D.; Zhang, Y. Facile Preparation with High Yield of a 3D Porous Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Dramatically Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution under Visible Light. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 238, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Safaei, J.; Ismail, A.F.; Jailani, M.F.A.M.; Khalid, M.N.; Noh, M.F.M.; Aadenan, A.; Nasir, S.N.S.; Sagu, J.S.; Teridi, M.A.M. The Influences of Post-Annealing Temperatures on Fabrication Graphitic Carbon Nitride, (g-C3N4) Thin Film. Applied Surface Science 2019, 489, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Guo, Y.; He, X.; Gao, P.; Hou, G.; Hou, J.; Song, C.; Guo, X. Intermediate-Induced Repolymerization for Constructing Self-Assembly Architecture: Red Crystalline Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Notable Hydrogen Evolution. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2022, 310, 121323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, W.; Qiu, B.; Zhu, Q.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Self-Modified Breaking Hydrogen Bonds to Highly Crystalline Graphitic Carbon Nitrides Nanosheets for Drastically Enhanced Hydrogen Production. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 232, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Wen, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, S. Graphitic Carbon Nitride with Thermally-Induced Nitrogen Defects: An Efficient Process to Enhance Photocatalytic H2 Production Performance. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 18632–18638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Huang, C.; Wang, X. Post-Annealing Reinforced Hollow Carbon Nitride Nanospheres for Hydrogen Photosynthesis. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | C (wt.%) | H (wt.%) |

N (wt.%) | O (wt.%) |

C/N (a. r.)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN-M | 35.7 | 1.6 | 62.2 | 1.1 | 0.67 |

| CN-M-Air | 35.7 | 1.6 | 61.8 | 1.1 | 0.67 |

| CN-M-CO2 | 35.7 | 1.6 | 61.8 | 1.1 | 0.67 |

| CN-U | 35.3 | 1.6 | 61.3 | 1.6 | 0.67 |

| CN-U-Air | 35.4 | 1.6 | 60.7 | 1.7 | 0.68 |

| CN-U-CO2 | 35.6 | 1.6 | 61.4 | 1.3 | 0.68 |

| Scheme | 2. ringa. | ACN2(NHx)/ ACN3 |

|---|---|---|

| CN-M | 80 | 2.0 |

| CN-M-Air | 77 | 2.0 |

| CN-M-CO2 | 78 | 2.0 |

| CN-U | 77 | 1.9 |

| CN-U-Air | 78 | 1.9 |

| CN-U-CO2 | 77 | 1.8 |

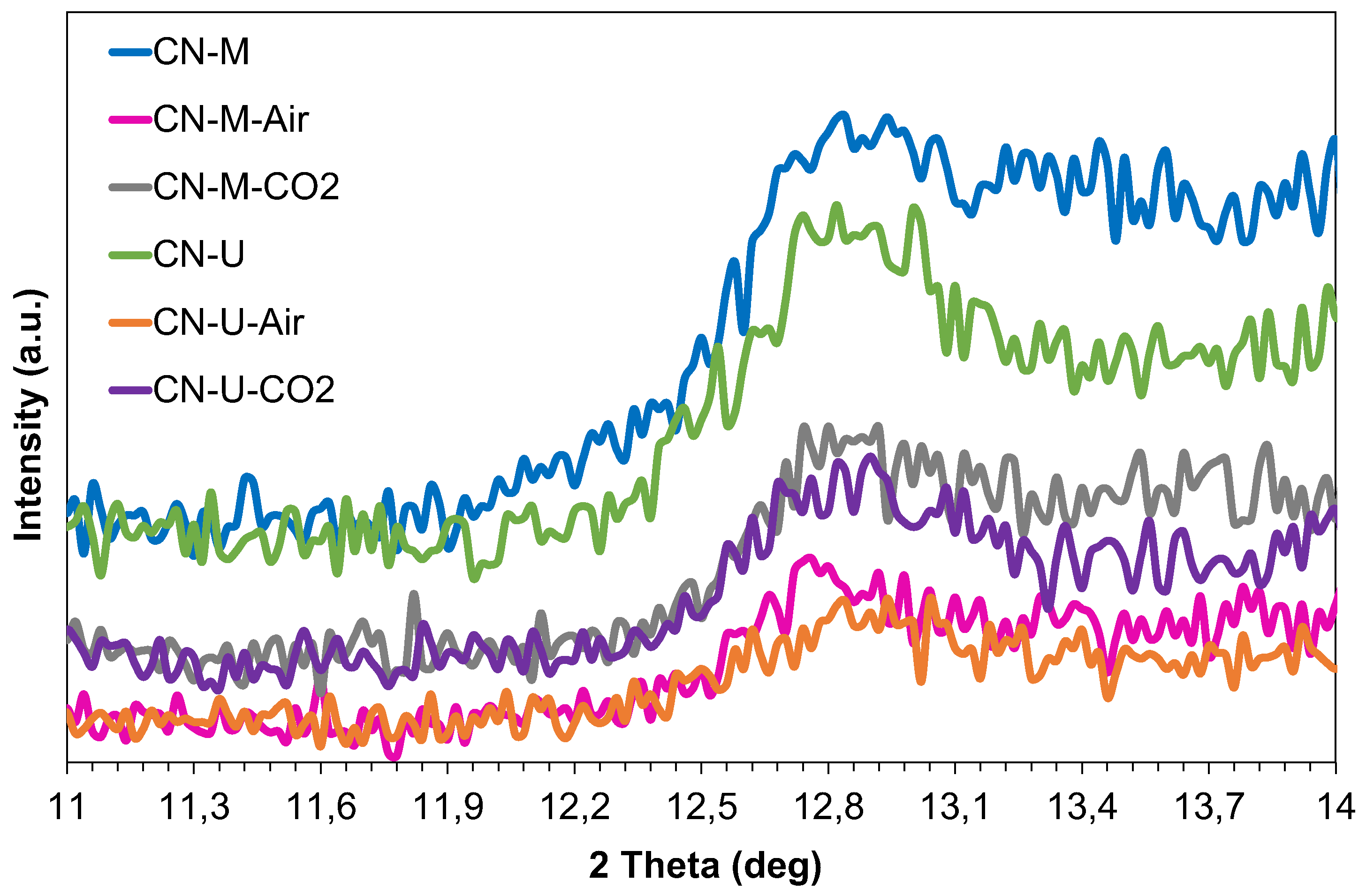

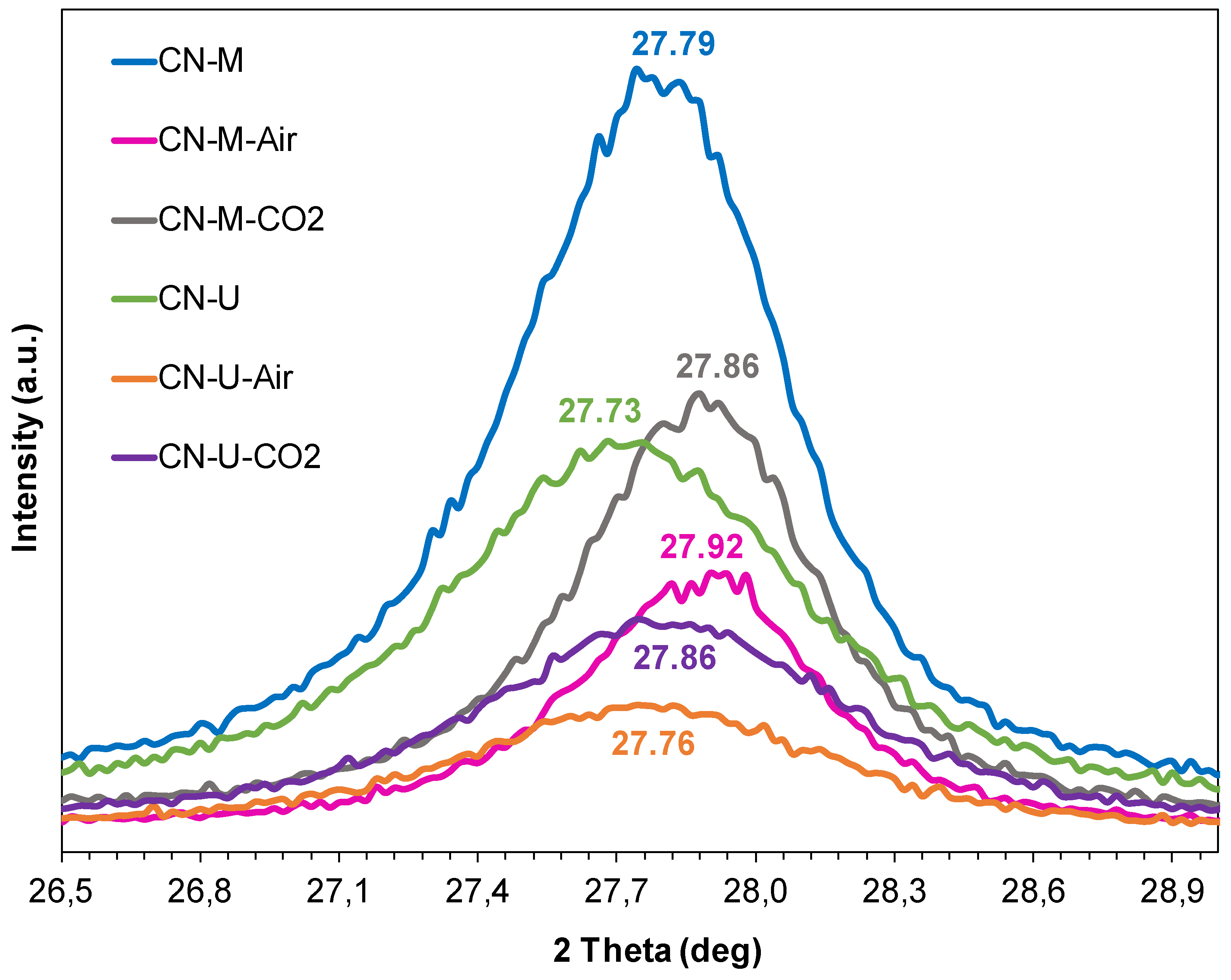

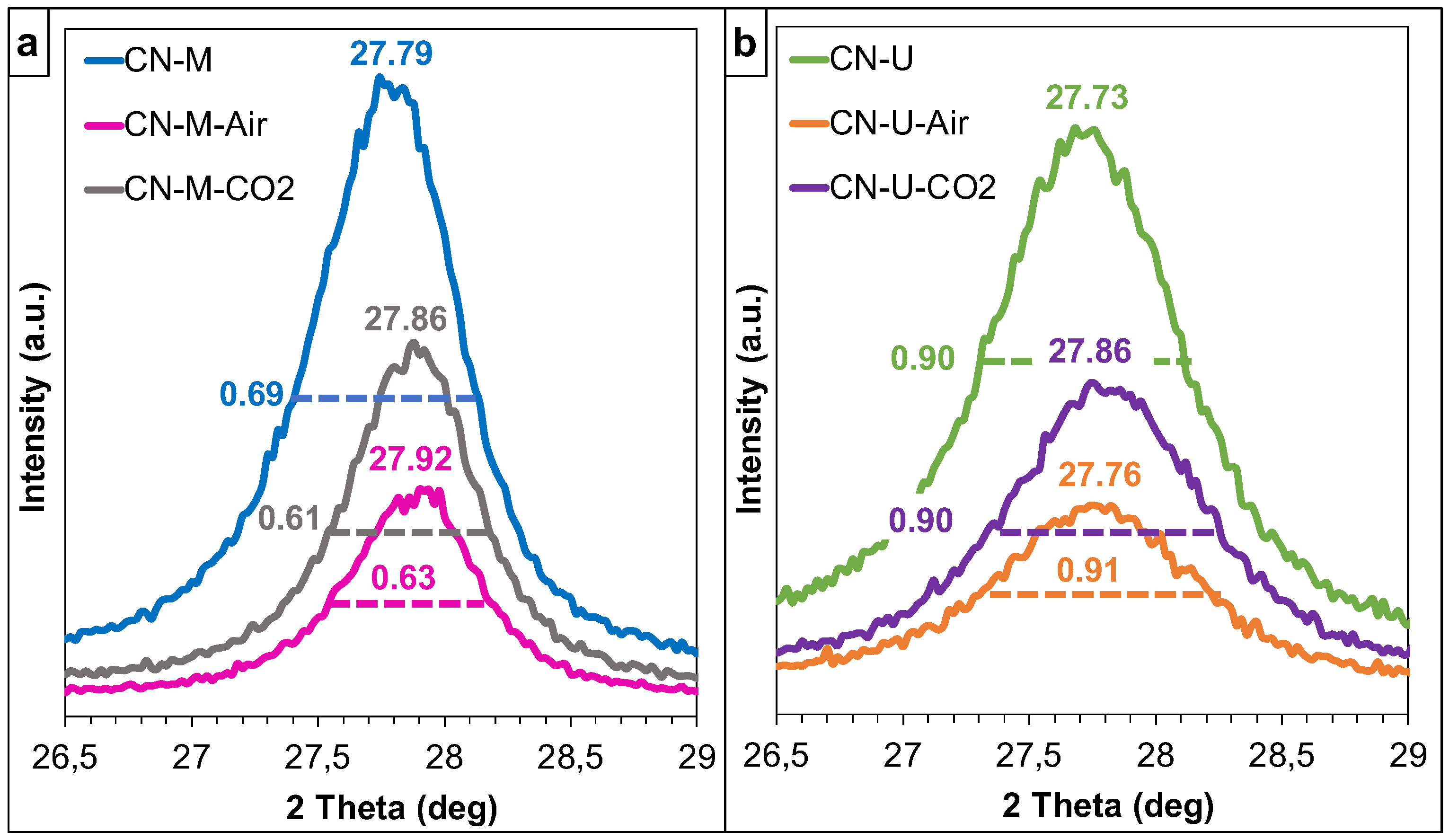

| Sample | dTSTZN (Å) | dSTZN (Å) | dinterlayer (Å) | Thickness of stacks (nm) | No. layers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN-M | 6.89 | 5.01 | 3.21 | 9.2 | 29 |

| CN-M-Air | 6.92 | 5.05 | 3.20 | 9.7 | 30 |

| CN-M-CO2 | 6.93 | 5.02 | 3.19 | 10.0 | 31 |

| CN-U | 6.93 | 4.98 | 3.21 | 7.1 | 22 |

| CN-U-Air | 6.88 | 5.04 | 3.21 | 6.8 | 21 |

| CN-U-CO2 | 6.94 | 4.99 | 3.20 | 7.0 | 22 |

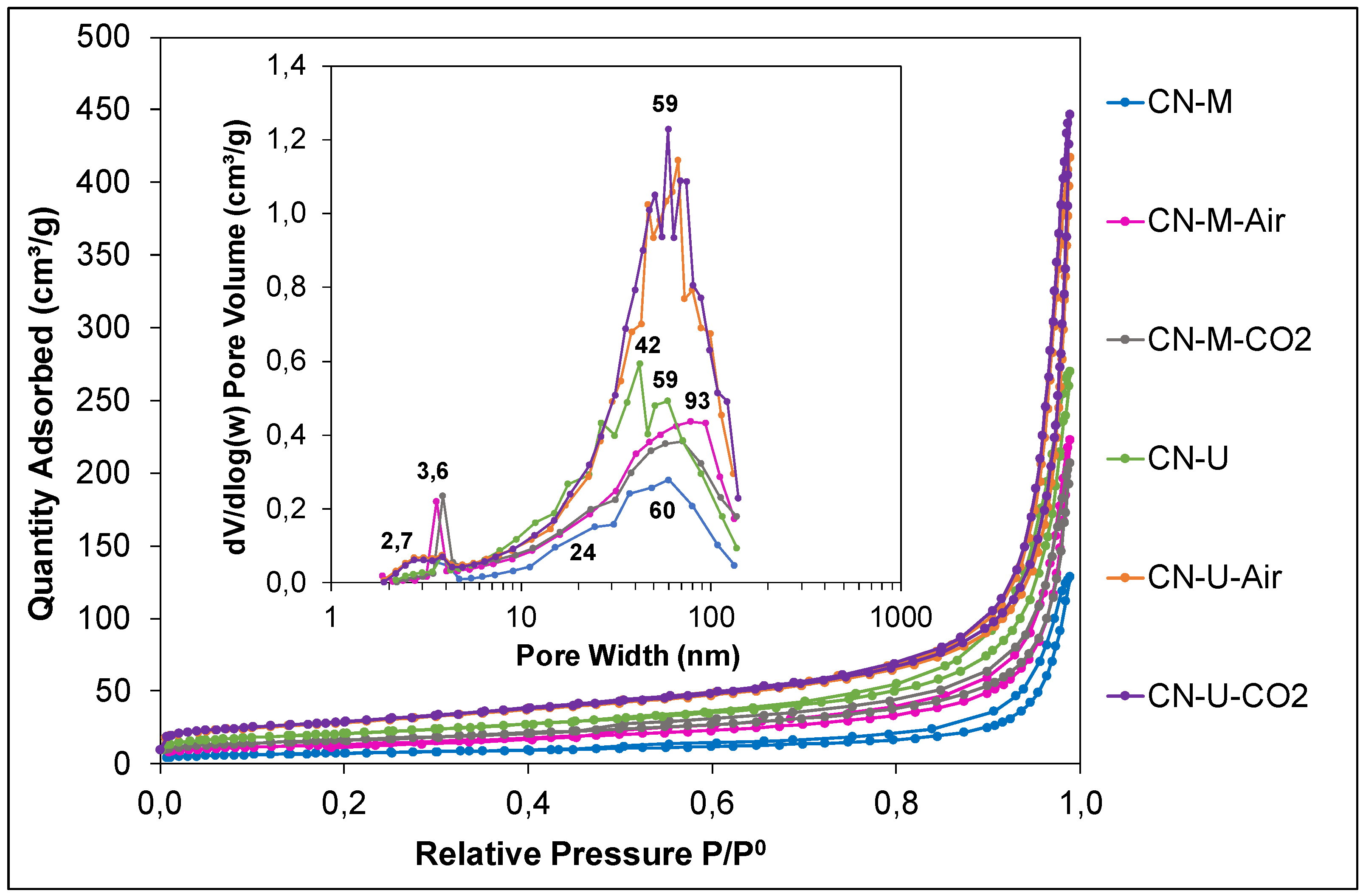

| Sample | SBET (m2/g) | Total pore volume (cm3/g) | Peak pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN-M | 26.3 | 0.108 | 60 |

| CN-M-Air | 47.7 | 0.180 | 93 |

| CN-M-CO2 | 58.4 | 0.177 | 70 |

| CN-U | 74.2 | 0.266 | 42 |

| CN-U-Air | 100.3 | 0.299 | 67 |

| CN-U-CO2 | 102.5 | 0.316 | 59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).