1. Introduction

Countries, counties, and individual households must have sufficient resources within their boundaries to achieve an adequate standard of living. An adequate standard of living encompasses basic needs such as housing, food, and higher-quality products and services, including electricity, appliances, sanitation, internet access, and healthcare [

1]. These basic needs are enshrined in South Africa’s constitution.

1 The ability to meet these needs often depends on a region’s location and socioeconomic conditions. When comparing countries in the global North and the global South, there are existing disparities directly proportional to the socioeconomic status of the different nations [

2]. Countries in the global south are often considered less developed, facing poorer socioeconomic conditions than their northern counterparts. This can often be linked to historical and sociopolitical factors. Various disparities create significant challenges, particularly regarding resource constraints, which refer to limitations that hinder the ability to perform specific tasks due to a lack of necessary resources [

3]. Nations such as India, Brazil, Pakistan, and many African countries are characterized as underdeveloped, struggling with inadequate housing and sanitation, and having a high rural population [

2]. For individuals in these impoverished communities, fulfilling basic living needs is often a daunting challenge. Moreover, accessing higher-order products and services, such as quality education and healthcare, and participation in political and social affairs becomes significantly more difficult, further exacerbating these issues [

4]. When designing solutions to address these challenges, the most critical need is to prioritize food security.

1.1. Food Security

Exploring the food security concept can provide an in-depth understanding of the state of food availability within particular settings. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) describes people as food secure when there is access to adequate, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences [

5]. A four-pillar framework is used to assess the extent to which individuals are food secure: availability, access, utilization, and stability. The availability pillar examines food availability in sufficient quantities, and the accessibility pillar determines whether individuals or households have the economic and physical means to access the food [

6]. In South Africa, the second pillar, although the country is food secure at a national level, is still faced with an existential hunger crisis at a household level. The food utilization pillar deals with the preparation and consumption of quality food in adequate quantities, and the stability pillar refers to the steady supply of food, which economic, environmental, and political factors can determine. Most African nations (global south countries) are marked by poverty and poor socioeconomic status, which threaten food security in the continent.

1.2. Factors Threatening Food Security

One of the leading threats to food security in the world, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, is environmental degradation and loss of soil productivity [

7]. Environmental degradation results from improper land use activities carried out on the land. As a medium through which food is produced, degraded land reduces food production, threatening food security [

8]. Land degradation reduces the soil’s productive ability and can contribute to greenhouse gas emissions due to the nonsequestering of carbon [

9]. To combat land degradation, it is believed that farmers should apply regenerative practices that can further help prevent environmental destruction.

What makes food security a serious issue for Sub-Saharan Africa is the high number of its food-insecure rural population, whose majority rely heavily on agriculture for their livelihoods (9). Countries within this region face accelerated population growth, reduced production levels to match population needs, and a lack of institutional support and education on best production practices [

8,

10]. Many of these nations are dominated by a small-scale sector that provides most of the produce for local markets [

10]. It is forr this reason that small-scale farmers require interventions from various stakeholders to apply the best production practices and sustainable techniques.

In contrast to its other African counterparts, South Africa consists of a dualistic agricultural sector, one being a well-developed commercial sector producing 90 percent of food for export and local market, and a small-scale sector catering mainly to the informal market [

11]. For this particular study, the small-scale sector is characterized by farmers who produce limited quantities of food on small pieces of land and mainly contribute to the livelihoods of rural communities [

12]. These rural settings face land degradation from poor soil management practices [

13] and lack of access to markets, capital, and education [

14].

1.3. Conservation Agriculture

The challenges faced by rural communities require a multi-stakeholder solution designed by different experts from natural resource management, policymakers, and the farmers themselves. From a natural resource management or farming perspective, conservation agriculture (CA) is presented as a solution for improving production for long-term sustainability, soil rejuvenation, and climate-smart agriculture [

15]. CA is a practice that involves three principles of no-tillage, or reduced tillage, soil cover by mulch or planting cover crops, and diversification of crops by rotational farming or intercropping [

16]. CA has benefits such as improving soil organic matter and soil biodiversity [

17], improving soil fertility over time, and acting as a drought buffer [

18]. The adoption of CA varies according to an area’s environmental conditions and must be adapted accordingly. It is a practice that requires high knowledge to be implemented correctly [

16]. Exploring the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality as an area of focus, the researchers sought to study the perceptions of small and medium-scale farmers that practice CA practices to determine conservation agriculture’s role in enhancing food security.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

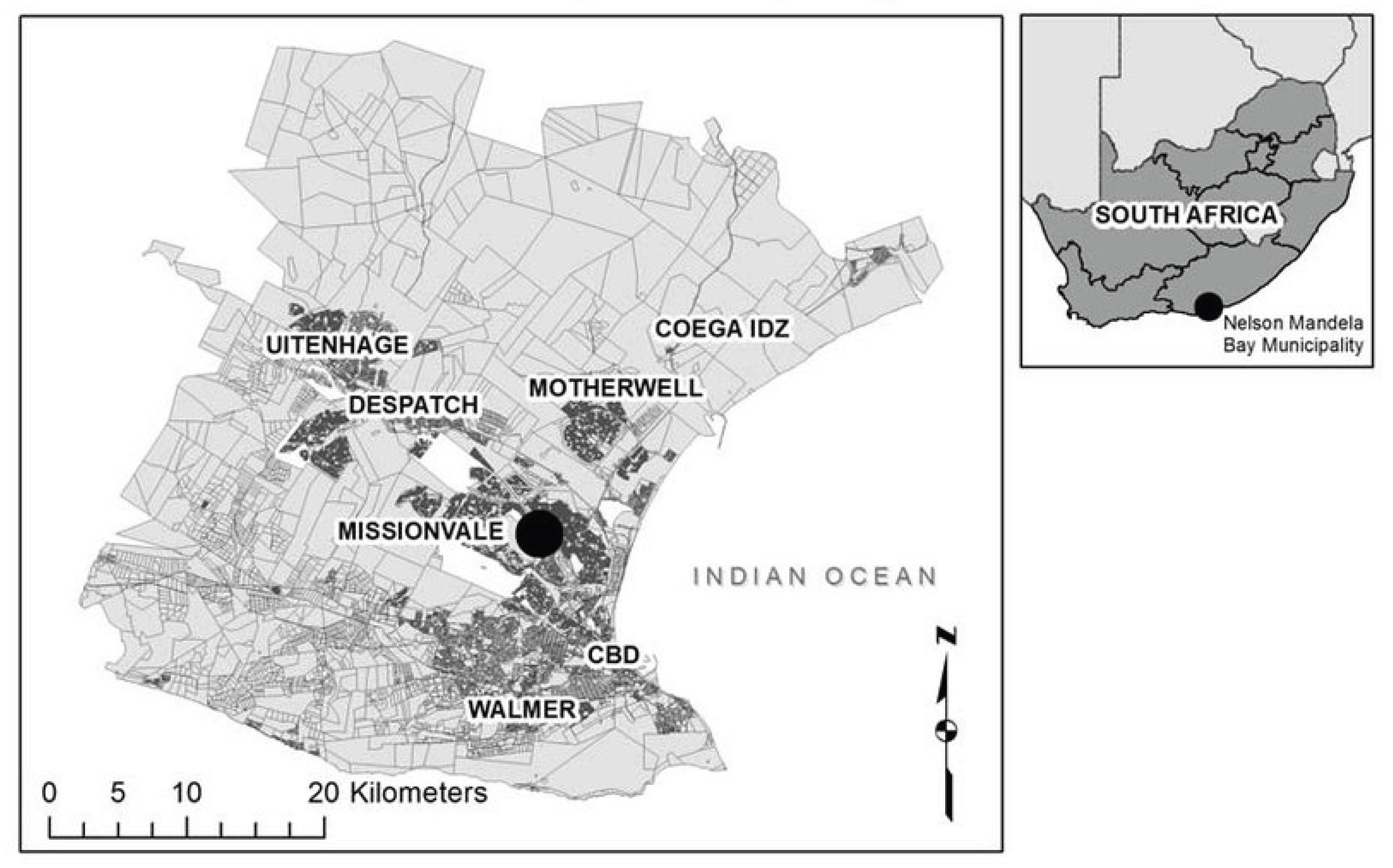

The study was conducted in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (NMBM), which falls within the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The Eastern Cape province is one of the poorest provinces in the country, with many black communities living in extreme poverty [

20]. The highest population where extreme poverty prevails is in rural settings, areas where rural-urban migration occurs due to poverty and the search for better livelihoods [

21]. Characterized as one of the province’s two metropolitan municipalities, NMBM is located along the country’s south coast [

22]. Areas such as Port Elizabeth, Uitenage, and Dispatch are encompassed within the NMBM, which spans an area of 1959.02 square kilometers. Like most rural areas, some areas in NMBM suffer from poverty-related challenges, where people do not have adequate infrastructure and other essential needs for survival [

23]. The NMBM Integrated Report reported that the population within the municipality is 1,263,051 [

22]. The population is expected to increase as it continues to rise.

Figure 1.

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality [

19].

Figure 1.

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality [

19].

2.2. Sampling

The target population for the study was small to medium-scale farmers who practice conservation agriculture (CA). These CA practitioners had to be small- and medium-scale farmers involved in market trade. The study utilized a purposive sampling approach to select participants with the desired traits to be included [

24]. A snowballing approach was also used to recruit participants, as CA practitioners are limited. Snowballing is a convenience sampling approach that can be utilized when a few participants who share the same traits required for the study are limited [

25]. Before data collection commenced, ethical clearance was obtained from the Nelson Mandela University Research Ethics Committee for studies involving humans (REC-H), Reference Number: 2024-RECH-1025-1851.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using an interview schedule to understand the experiences and perceptions of farmers and individuals who chose to adopt CA. Interview schedules are utilized when a researcher seeks to have in-depth conversations that will yield various outcomes that can be used to develop themes [

26]. The responses were analyzed using COSTAQDA. This computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) analyzes qualitative data. Data were analyzed using an interpretive approach, wherein knowledge is constructed through the lived experiences of individuals rather than through quantifiable data obtained from experiments or questionnaires [

27]. The data analysis resulted in the development of themes from the combined responses of participants.

3. Results and Discussion

The findings revealed both the conservation agriculture (CA) practices implemented by participants and the underlying motivations guiding their adoption. These practices were primarily employed to reverse long-term environmental degradation, prevent further ecological harm, and enhance resilience to environmental stressors such as climate change and water scarcity. The core practices centered on maintaining continuous soil cover through mulching and cover cropping, minimizing or eliminating soil disturbance, and adopting crop diversification strategies. Eighty percent of the participants reported deliberate and structured adoption of CA, aligning closely with its three foundational principles defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). In contrast, the remaining twenty percent employed CA concepts more selectively, integrating only those elements aligned with their specific farm objectives and resource availability rather than adhering to the whole CA framework. This partial adoption reflects a pragmatic approach, where farmers tailor agricultural techniques to suit their operational context. The following responses illustrate these differences in application:

“...Those are the three principles: one is minimal soil disturbance, the second one is permanent organic soil cover, and the third one is diverse cropping systems. So, those are the three principles defined by the FAO, and they also have complementary practices that go with that like integration of animals, integrated pest, disease, wheat, and soil fertility management…” _ R1

“Since sugarcane is a monocrop, it follows a monoculture system where the soil often is not given a chance to rest. To address this, I introduced a strategy of pulling out the cane every seven years, aligning with a ratoon crop’s typical lifespan. While it does not always happen perfectly, I aim to stick to this practice. After removing the cane, I rest the field for a year to allow the soil, microorganisms, and overall ecosystem to regenerate.”_ R2

The contrasting practices are evident in the participant narratives presented above. One demonstrates full adherence to Conservation Agriculture (CA) principles, while the other selectively omits one or more core components. This selective or partial adoption is a strategic choice influenced by the farmer’s unique objectives, agroecological context, and the availability of on-farm resources. Such variability in application is not necessarily indicative of non-compliance but reflects the adaptive strategies farmers employ to meet context-specific needs. Swanepoel (2021) supported this perspective and found that the same CA principles yielded divergent outcomes depending on environmental conditions. In humid regions, certain practices led to suboptimal results, whereas the same approaches were more effective in arid settings. This underscores the importance of flexibility in implementation and validates the rationale behind partial adoption, particularly in diverse agroecological zones where a rigid application of all CA principles may not be feasible or beneficial.

3.1. Contribution to Food Security

CA is used as a strategy to conserve the soil and other components of the ecosystem. Most practitioners cautioned that CA should not be seen as a trend that is followed for economic gain but rather as a response to the common threats in the agricultural sector, including environmental degradation, climate change, and food insecurity. This is corroborated by [

28], who applaud small farmers for continually applying CA practices while producing food without degrading the environment over time. During the interview with the study participants, a representative from Farming God’s Way, a biblically anchored agricultural organization that teaches the practice of farming solely based on CA principles, asserted the following:

‘..Not many want to listen because it is all about the rands and cents. Farmers will not hear about conservation farming practices because they are about profit margins. Effectively, they have been very short-sighted. After all, they are not thinking about future generations. They are thinking about money..”_R3

When defining food security, it is not enough that food is available and accessible; it must be nutritious and suitable for consumption. This speaks to the food security definition’s food utilization pillar. Quality foods must be consumed for a healthy life. There are universal concerns regarding the amount of chemicals contained in food due to the mass adoption of industrial agriculture, which relies on the heavy use of agricultural chemicals, especially on a commercial scale. There lies an opportunity to produce both cash crops and field crops in an environmentally sustainable way. One such approach to achieve this is through the application of CA, which is a sustainable approach to farming that indirectly advocates for the anti-use of chemical inputs [

29]. Supporting our argument are lessons from the study participants, who indicated that they do not utilize chemicals in their farming practices as they damage the soil structure. Instead, composting and biological pest control strategies were proclaimed as best practices. The following are some of the responses from the participants regarding the use of chemicals.

“…And the compost is not only a food source for the garden, it is there to form a buffer for pests and disease inside the soil. To help balance the pH inside the soil and help the plant take up those necessary carotenoids and flavonoids full of antioxidants for you and me to eat…”_R4

“…If you listen to Dr Zach Bush, somebody that I recommend you Google, you will never touch Roundup in your life again. There are so many dangerous chemicals out there, so I would say, to be honest, I have probably been on the farm for the last 15/20 years, and I have made more of an impact and been more conscious about biological farming than the past generations were…”_R5

“…I think it is because we do not have much knowledge. I think we need to be empowered to use chemicals and products that can enhance the production of our products. The only reason is that we do not have much knowledge and understanding of the use of chemicals…” _R6

The diverse motivations behind participants’ decisions to adopt or reject conservation agriculture (CA) suggest significant opportunities to promote this sustainable practice. While health concerns and the pursuit of knowledge are dominant themes, many decisions are also shaped by contextual and circumstantial factors. For example, Participant R6 refrains from using chemical inputs not out of conviction but due to a lack of knowledge and understanding, highlighting the potential for uptake if adequate guidance and support are provided.

3.2. Economic Considerations

Two key factors arise from the findings on the economic aspect of CA. The first one is the input costs that go into crop production. Costs associated with conventional practices, such as procuring chemical inputs and their high prices, can create agrochemical resistance [

30]. The machinery used for land preparation costs can be high [

31]. The following responses illustrate the economic constraints associated with conventional approaches in farming:

“…Number one, we do not plow, so we do not have to pay off someone for a tractor and a plow. Number two, we do not have to hire a tractor, plow, or plowman with the cattle. So those expenses are not covered by our farm. Number three, we do not have to buy lime to correct the soil’s acidity; we are using wood ash, God’s all-sufficiency, and we do not have to, so that cost is not there. We do not have to buy chemical fertilizer whose price is increasing every year, and the input of your fertilizer has to be increased every year because of the negative salts left behind from the previous year…” _R7

“…if we are going to degrade our natural resources even further. We should allow that! Our profitability will go down the drain if we do not change it. All of those factors, including the financial, social, and bio-physical sustainability of existing conventional production systems, are highly compromised and not sustainable. In other words, our food production is highly compromised at this stage…”_R8

These responses show that conventional practices are not sustainable in the long term. They result in the loss of inputs and some ecosystem services, particularly provisioning services such as food and water, as soils are gradually degraded due to the continuous use of agrochemicals, which often leads to eutrophication. Although CA is associated with long-term growth in soil productivity and crop improvement, the initial implementation is often costly. Resource-constrained producers, like smallholders, often lack CA equipment, initial capital for required inputs, and knowledge of CA practices (31). Although CA can have many merits when applied correctly, these economic challenges prevent CA adoption.

“…I think in all sincerity, to farm properly and from a conservation point of view in the region, it does cost more money; there is no denying that. Moreover, money is always a challenge for everyone because, you know, everyone farms by numbers. However, when you choose this way of farming and this lifestyle, you make peace with the fact that it will cost you extra and that income will not be as lucrative as you would if you go completely commercial. However, in principle, I will not go commercial, so the challenge is the cost factor by all accounts and the cost factor…”_R9

“…I think many farmers quit too quickly, like after one or two years, which is too quick. You need to decide when you go to conservation agriculture first and understand that this is a lifelong process. It is a lifelong journey; you are not going to stop even after you have failures after one or two seasons, you are not going to stop. This is the right way, and you need to know that you will build up your soil into agroecology, etcetera, but that will take time. You need to be careful and monitor it, not stopping after one year or two years, or when you realize nothing has happened or very little has happened…”_R10

The statements presented by the participants (R9 and R10) illustrate that when implementing CA, the motivation should not be driven mainly by economic gain. Long-term dedication to the cause is required for every individual concerned about sustainable agriculture. Research indicates that the evidence and visibility of the effects of CA can take time to manifest, and they are contextual [

29]. For some individuals, such as the resource-constrained groups, which are characterized by low socioeconomic status and often require immediate results, fully adopting CA could be challenging, requiring support from the government, non-government organizations (NGOs), the private sector, and other relevant players.

3.3. Stakeholder Involvement

The collaboration between policymakers and scholars is essential for implementing a knowledge-intensive and critically formulated multi-stakeholder framework. A study examining the collaboration between researchers, extension services, farmer organizations, and governmental departments showed that stakeholder collaboration fosters transformative farming [

32]. This collaboration needs a proactive and goal-oriented approach. Supporting this claim was the emphasis made by the respondents on the important role different stakeholders can play.

“...Yes, we have collaborated with the Department of Social Development. The Department of Agriculture also had extension officers to assist us where we needed assistance. For example, we had cabbages, and aphids were eating our cabbages, and then they came in to check on us. They advised us to mix the dishwashing liquid and cayenne pepper …”_R11

“A key priority is establishing institutions that adopt appropriate approaches, create meaningful opportunities, and allocate adequate resources to support such programs. It is essential for extension officers and the Department of Agriculture, whether at provincial, district, or local municipal levels, to take the lead in initiating these programs. This involves ensuring that the right individuals, equipped with relevant training and expertise, are tasked with developing clear strategies to guide the implementation and direction of both the broader program and the specific conservation agriculture (CA) initiatives.”_R12

Such collaborations require diverse knowledge contributions from various stakeholders, making collective effort essential. Scholars’ expertise can play a crucial role in informing policymakers, ultimately leading to the development and implementation of mandatory policies that are applicable to all relevant parties. These policies should be the result of stakeholder consensus, aimed at advancing the interests of smallholder producers and enhancing community food security.

5. Conclusions

Food insecurity emerges as a persistent and pressing challenge at the household level in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality. Given agriculture’s potential to address such insecurity, CA has been introduced as a sustainable farming approach to improve food production while conserving the environment. The study, conducted among small- to medium-scale farmers, revealed that CA holds significant promise as a viable farming method for improving food production and environmental sustainability. However, several challenges hinder its widespread adoption. Chief among these is the high initial costs of implementation and the delayed realization of returns, making it particularly burdensome for the farmers it aims to support. For many resource-poor farmers, the financial demands of adopting CA are beyond reach. A collaborative, multi-stakeholder approach is essential to address these challenges and fully leverage the potential of CA. Government entities, non-governmental organizations, research institutions, and private sector partners must work together to create an enabling environment for CA adoption that directly supports food security in resource-constrained communities. We further recommend the following:

The government should introduce targeted subsidies to assist farmers with the initial costs of adopting CA practices, including equipment, seeds, and training.

Expand agricultural extension services to provide hands-on training and continuous support for farmers adopting CA, focusing on building local knowledge and adapting techniques to specific ecological conditions.

Foster partnerships between government departments, universities, NGOs, and the private sector to design context-specific CA programs informed by research and community needs.

Establish local demonstration plots to showcase the long-term benefits and practical applications of CA, encouraging peer-to-peer learning among farmers. The Farming Gods Way Group has successfully demonstrated this, developing a successful model that has been implemented across Africa and other parts of the world.

Integrate CA into provincial agricultural development strategies and ensure that policies promote inclusivity, especially for women and youth in agriculture.

Implement systems to monitor the progress and outcomes of CA projects, ensuring accountability, knowledge sharing, and adaptation of evidence-based practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Data curation, Yongamela Magadla; Formal analysis, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Investigation, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Methodology, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Project administration, Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Resources, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Supervision, Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Validation, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe; Writing – original draft, Yongamela Magadla; Writing – review & editing, Yongamela Magadla and Qinisani Nhlakanipho Qwabe.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the REC-H Ethics Committee of Nelson Mandela University, reference number: 2024-RECH-1025-1851.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to all the participants who generously shared their time, experiences, and insights, making this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CA |

Conservation Agriculture |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| REC-H |

Research Ethics Committee - Human |

References

- Hickel, J.; Sullivan, D. How much growth is required to achieve good lives for all? Insights from needs-based analysis. World Development. Perspectives 2024, 35(100612), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitadze, N. The Global North-Global South Relations and their Reflection on the World Politics and International Economy. Journal of Social Sciences 2019, 8(1), 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chena, S.; Shen, T. Resource constraints and firm innovation: When Less is More? Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment 2023, 21, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S. Codesign in resource limited societies: theoretical perspectives, inputs, outputs and influencing factors. Research in Engineering Design 2022, 33, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Security. Policy Brief. Agriculture and Development Economics Division (ESA). Issue 2. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp, J.; Modeley, W.G.; Termine, P.; Burlingame, B. Viewpoint: The case for a six-dimensional food security framework. Food Policy 2022, 106, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; Van Wijk, M.; Hammond, J.; Descheemaeker, K.; Van de Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.T.; Taulya, G.; Chikowo, R.; Andersson, J.A. Small farms and development in Sub–Saharan Africa: Farming for food, for income or for lack of better options? Food Security 2021, 13, 1431–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U.; Neubacher, F.; Rahut, D.B.; Do, M.H.; Paudel, G.P. Security risks from climate change and environmental degradation: implications for sustainable land use transformation in the Global South. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2023, 63(101322), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.H.; Mohamed, A.A.; Mohamed, F. H. Enhancing food security in sub-Saharan Africa: Investigating the role of environmental degradation, food prices, and institutional quality. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 17(101241), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E. The Food Security Conundrum of sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Security 2020, 26(100431), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantsi, S.; Cloete, K.; Möhring, A. Productivity gap between commercial farmers and potential emerging farmers in South Africa: Implications for land redistribution policy. Applied Animal Husbandry & Rural Development 2021, 14, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah, L.N.; Simatele, M.D. Food Security and Coping Strategies of Rural Household Livelihoods to Climate Change in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5(692185), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya, S.; Holmes, J. K. C.; Gambiza, J. Drivers of Degradation of Croplands and Abandoned Lands: A Case Study of Mac;ubeni Communal Land in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Land 2023, 12(606), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngumbela, X.G.; Khalema, E. N.; Nzimakwe, T. I. Local worlds: Vulnerability and food insecurity in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2020, 12(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. A system approach to conservation agriculture. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2015, 70(4), 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francaviglia, R.; Almagro, M.; Vicente, J.L.V. Conservation Agriculture and Soil Organic Carbon: Principles, Processes, Practices, and Policy Options. Soil Systems 2023, 7(17), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Das, T. K.; Sharma, D. K.; Gupta, K. Potential of conservation agriculture for ecosystem services: A review. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2019, 89(10), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufa, A. H.; Kanyamuka, J. S.; Alene, A.; Ngoma, H.; Marenya, P. P.; Thierfelder, C.; Banda, H.; Chikoye, D. Analysis of adoption of conservation agriculture practices in Southern Africa: mixed methods approach. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyongwana, P. Q.; Heijne, D.; Tele, A. The Vulnerability of Low-income Communities to Flood Hazards, Missionvale, South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology 2015, 51, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Five Facts About Poverty in South Africa. 2019. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12075 (accessed on 02 May 2025).

- Currin, B. Insights into Township & Non-Township Populations in South Africa using the Marketing All Products Survey. 2024. Available online: https://geoscope-sa.com/2024/09/12/insights-into-township-non-township-populations-in-south-africa-using-the-marketing-all-products-survey/ (accessed on 03 May 2025).

- Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality. Integrated development plan 2022/23 – 2026/27. 2022. Available online: https://www.nelsonmandelabay.gov.za/DataRepository/Documents/executive-summary-of-2024-25-third-edition-idp_Kx5Jw.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Mpolweni, N.; Kabange, M.; Fagbadebo, O. M. Integrated development plan strategies for service delivery in Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review 2024, 12(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S. J. Purposeful Sampling: Advantages and Pitfalls. Prehosp Disaster Med 2024, 39(2), 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 2017, 14(3), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakilla, C. Strengths and Weaknesses of Semi-Structured Interviews in Qualitative Research: A Critical Essay. 1-5. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pervin, N.; Mokhtar, M. The Interpretivist Research Paradigm: A Subjective Notion of a Social Context. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 2022, 11(2), 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Loeper, W.; Musango, J.; Brent, A.; Drimie, S. Analysing Challenges Facing Smallholder Farmers in South Africa and Conservation Agriculture: A System Dynamics Approach. South African Journal for Economics and Management Sciences 2016, 5, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Baudron, F.; Setimela, P.; Nyagumbo, I.; Mupangwa, W.; Mhlanga, B.; Lee, N.; Gérard, B. Complementary practices supporting conservation agriculture in southern Africa. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2018, 38(16), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J. A.; Swanepoel, P. A.; Smith, H.; Smit, E. H. A history of Conservation Agriculture in South Africa. South African Journal of Plant and Soil 2021, 38(3), 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzangwa, L.; Mnkeni, P. N. S.; Chiduza, C. Assessment of Conservation Agriculture Practices by Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Agronomy 2017, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modirwa, M. S.; Oladele, O. I. Knowledge and Attitude Towards Collaboration in Agricultural Innovation Systems Among Stakeholders in the North West Province, South Africa. South African Journal for Agricultural Extension 2017, 45(1), 10–19. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

Section 26(1) of the South African Constitution gives everyone the right to access adequate housing. Similarly, Section 27(1) states that everyone has a right to (a) health care services, including reproductive health care; (b) sufficient food and water; and (c) social security, including, if they are unable to support themselves and their dependents, appropriate social assistance. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |