Submitted:

18 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

For a long time, glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation were opposed to each other. Glycolysis work when there is a lack of oxygen, the mitochondria supply ATP in oxygen environment. In recent decades, it has been discovered that glycolysis in vivo works always and the final product is lactate. Lactate can accumulate and is the transport form for pyruvate. In this review, we look at how obligate lactate formation during glycolysis affects the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and mitochondrial respiration. We conclude that fatty acid β-oxidation is a prerequisite for obligate lactate formation during glycolysis, which in turn promotes and enhances the anaplerotic functions of the TCA cycle. In this way, a supply of two types of substrates for mitochondria is formed: fatty acids as the basic energy substrates, and lactate as an emergency substrate for the heart, skeletal muscles, and brain. High steady-state levels of lactate and ATP, supported by β-oxidation, stimulate gluconeogenesis and thus supporting the lactate cycle. It is concluded that mitochondrial fatty acids β-oxidation and glycolysis constitute a single interdependent system of energy metabolism of the human body.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A Quick Critical Look at the Energy Metabolism from the Point of View of the New Paradigms

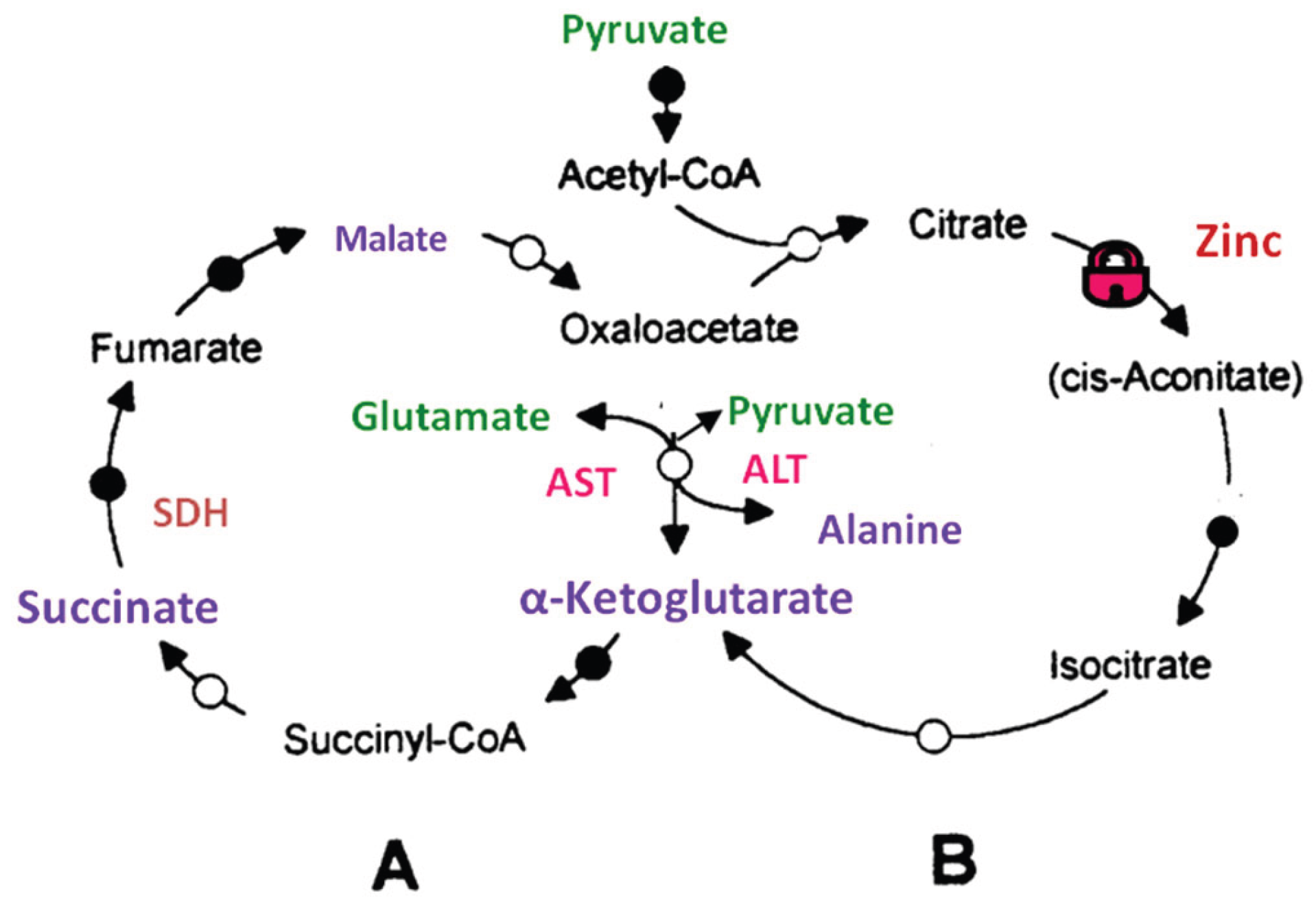

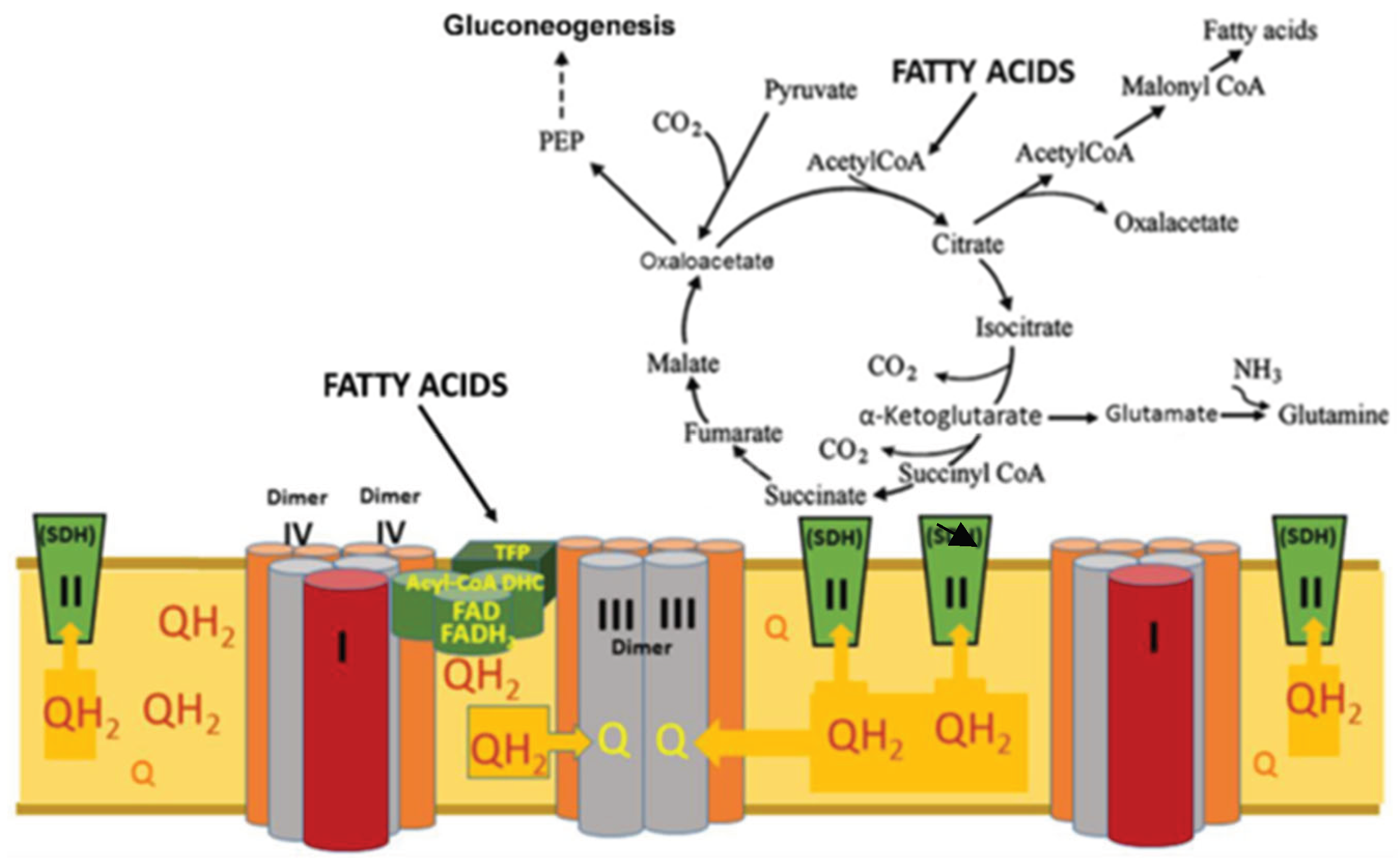

2.1. Glycolysis, Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle and the Mitochondrial Substrates

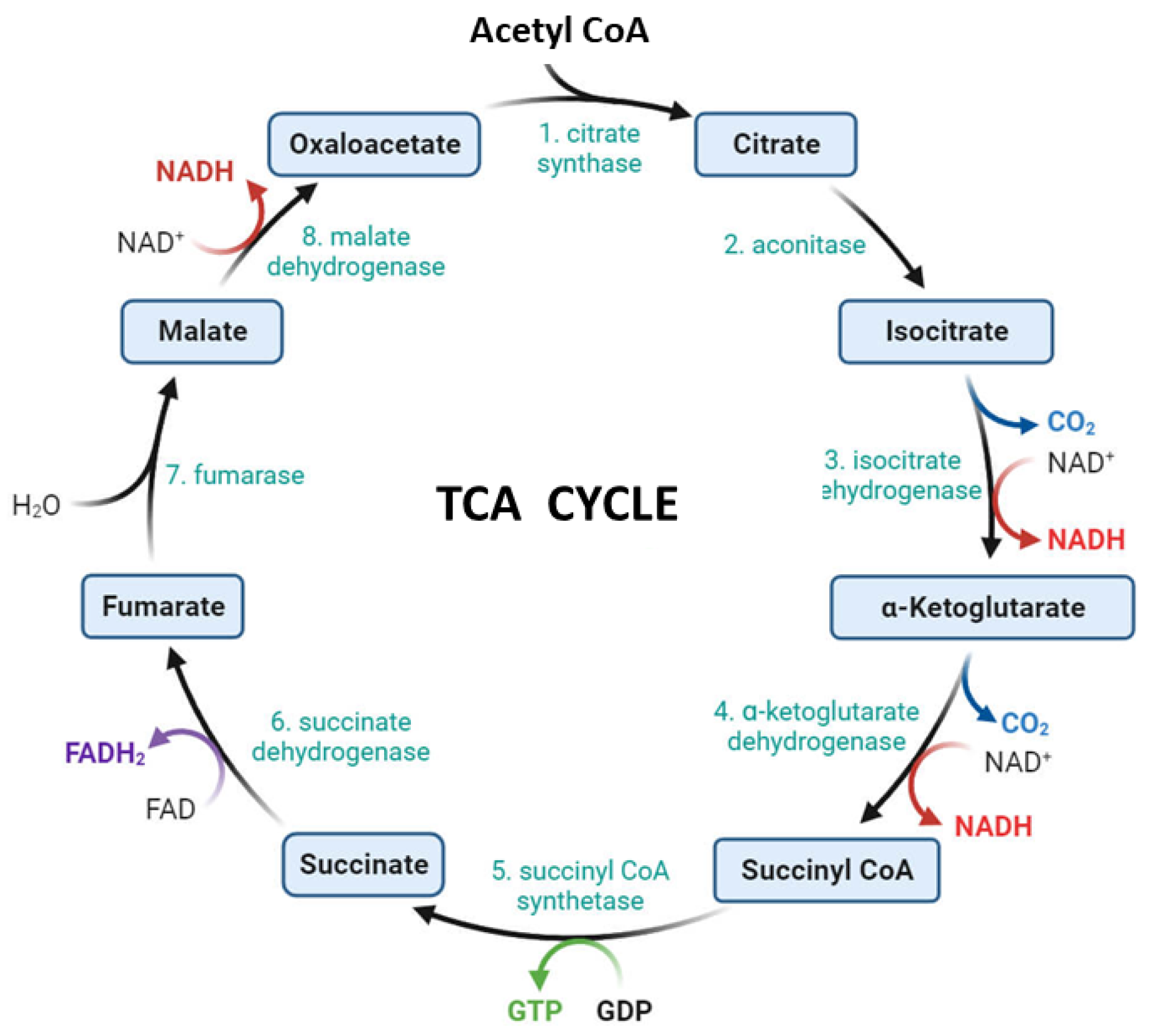

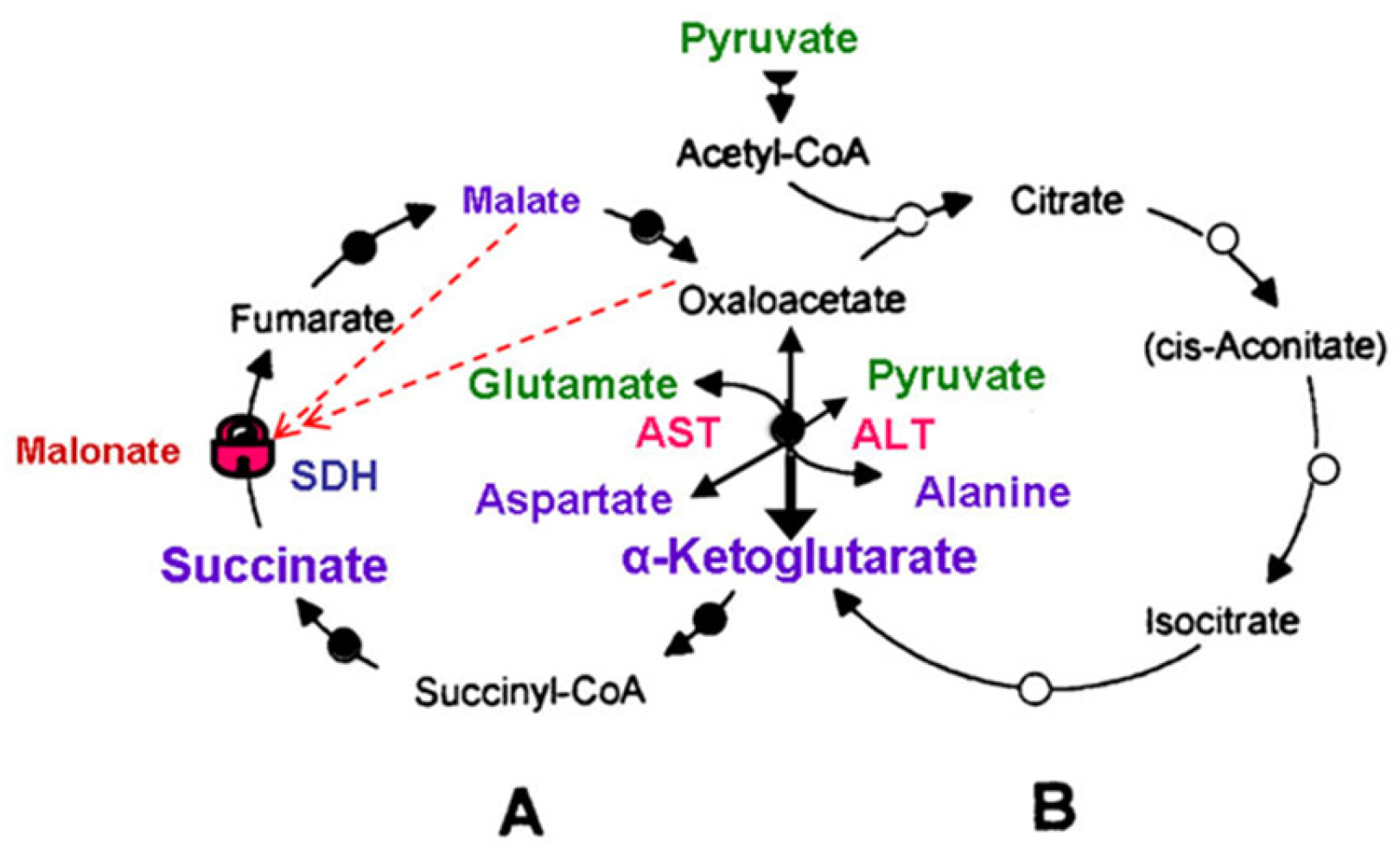

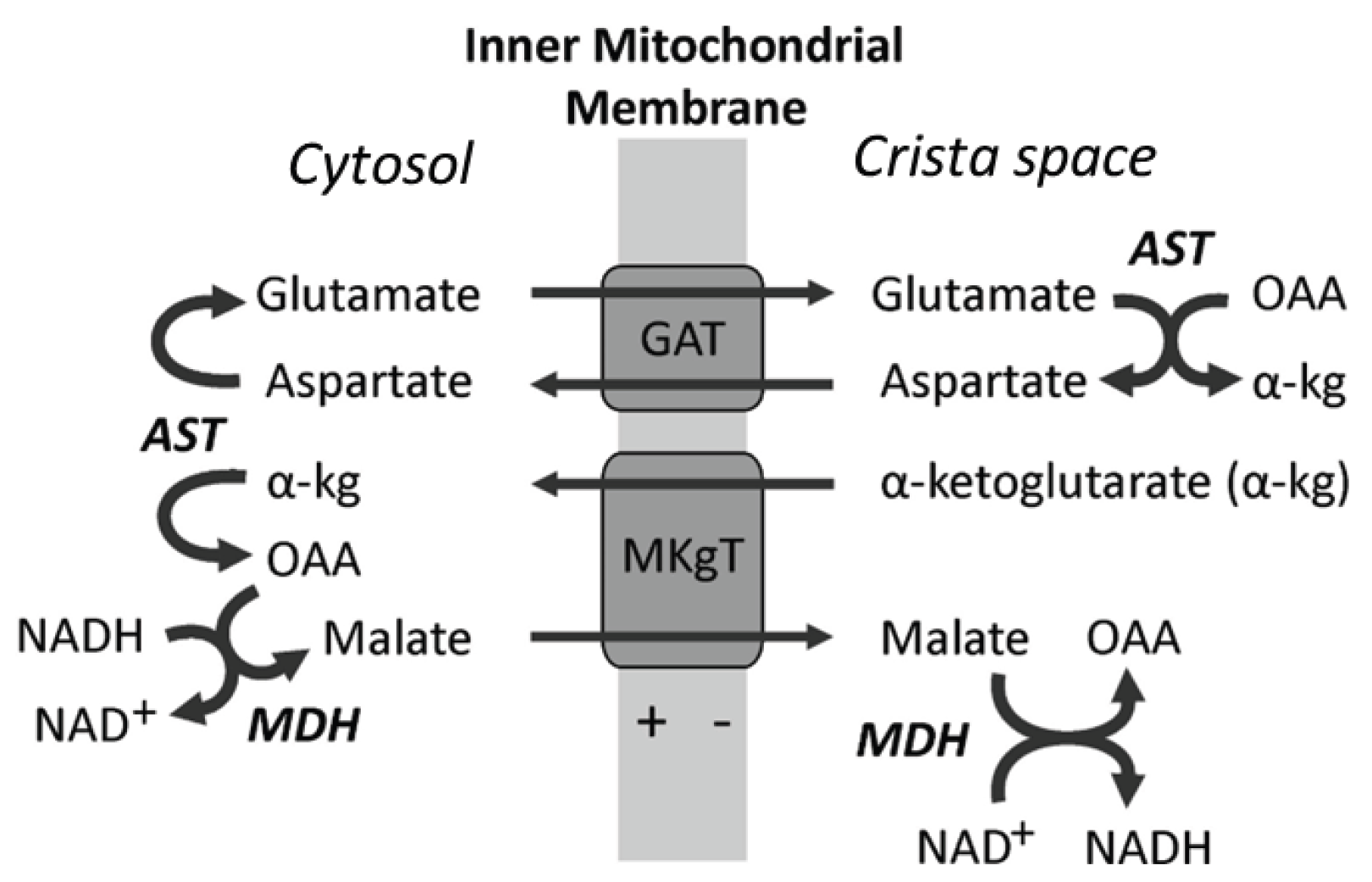

2.2. The Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle)

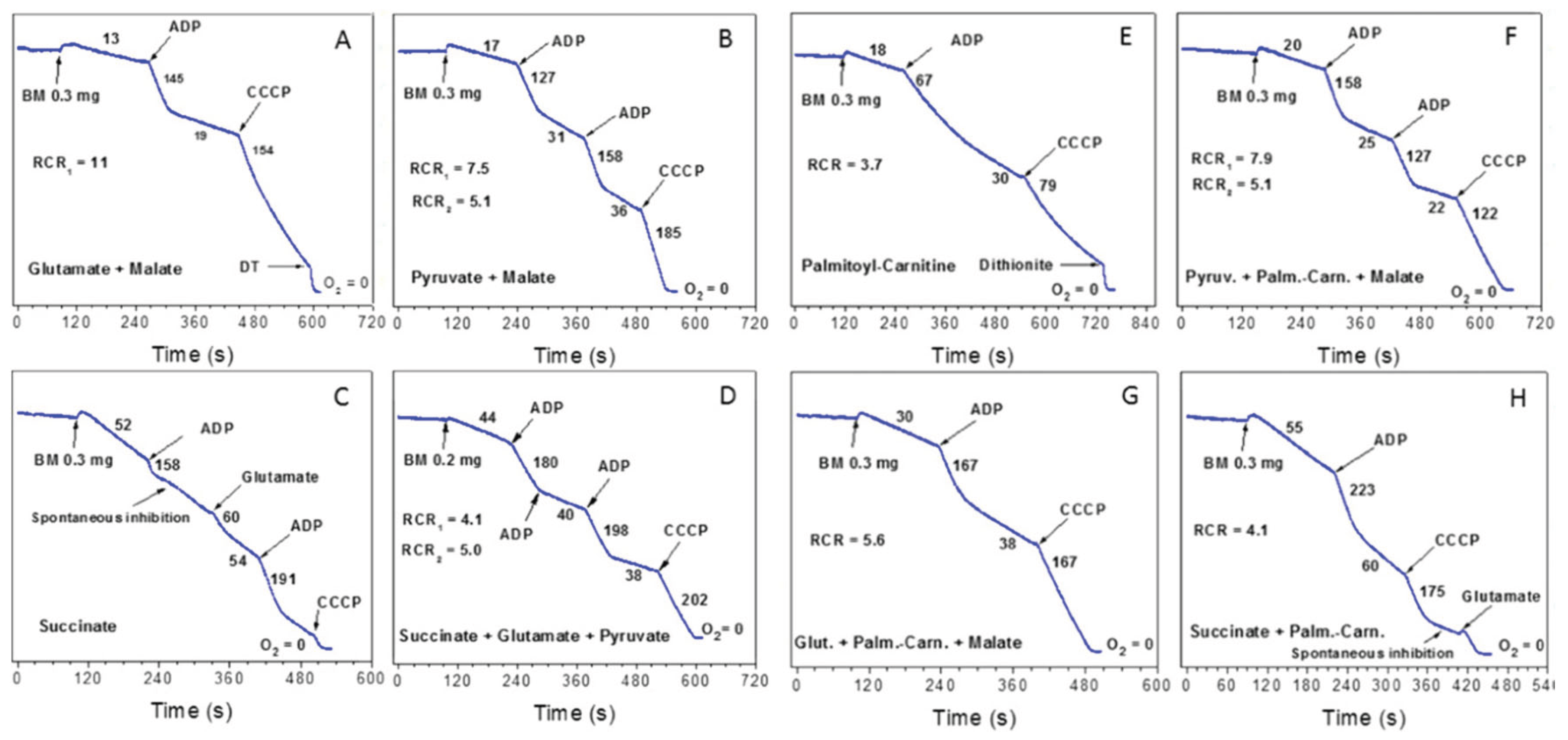

3. Respiratory Functions of the Isolated Mitochondria

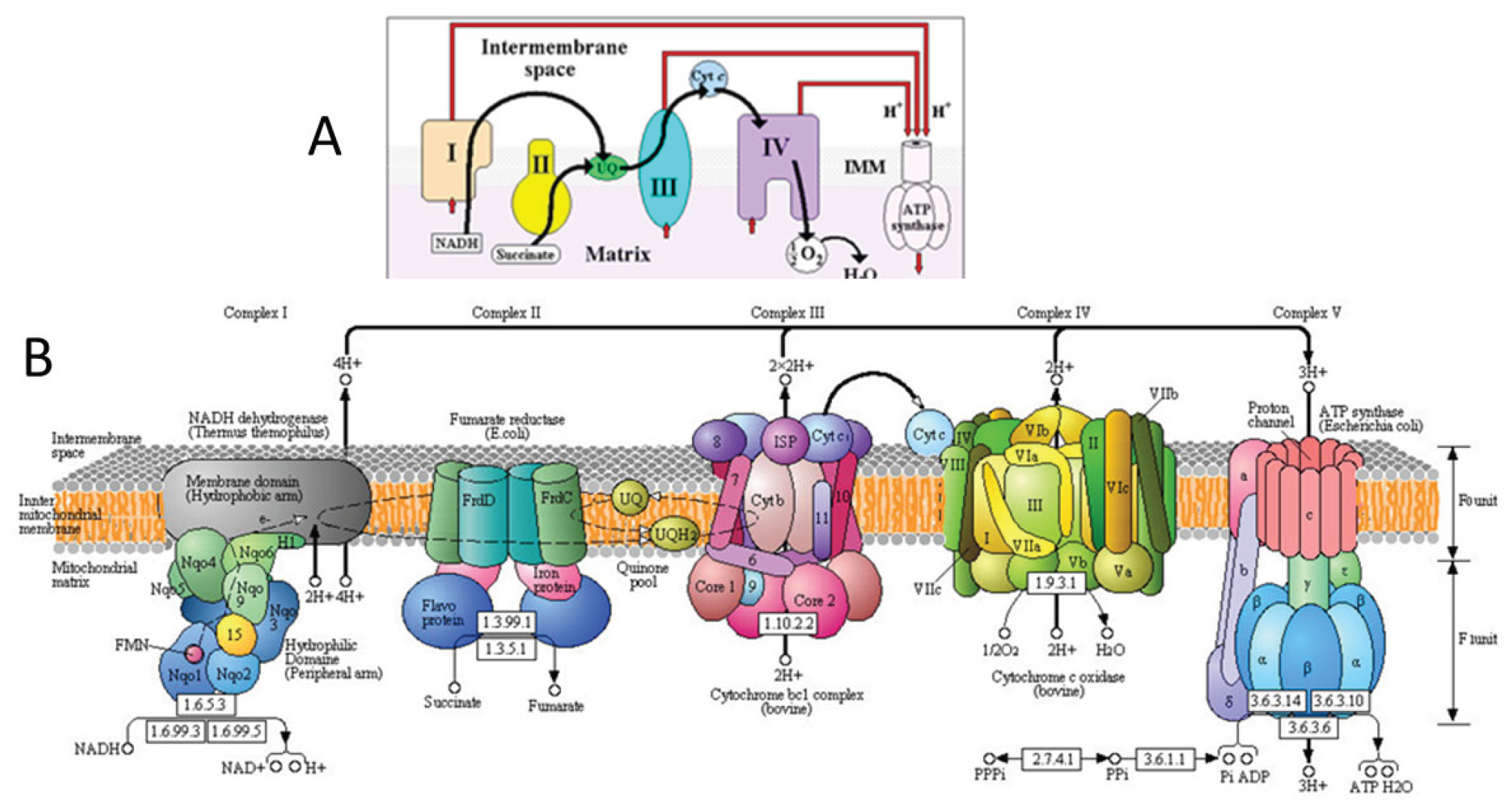

4. Respirasome

4.1. History

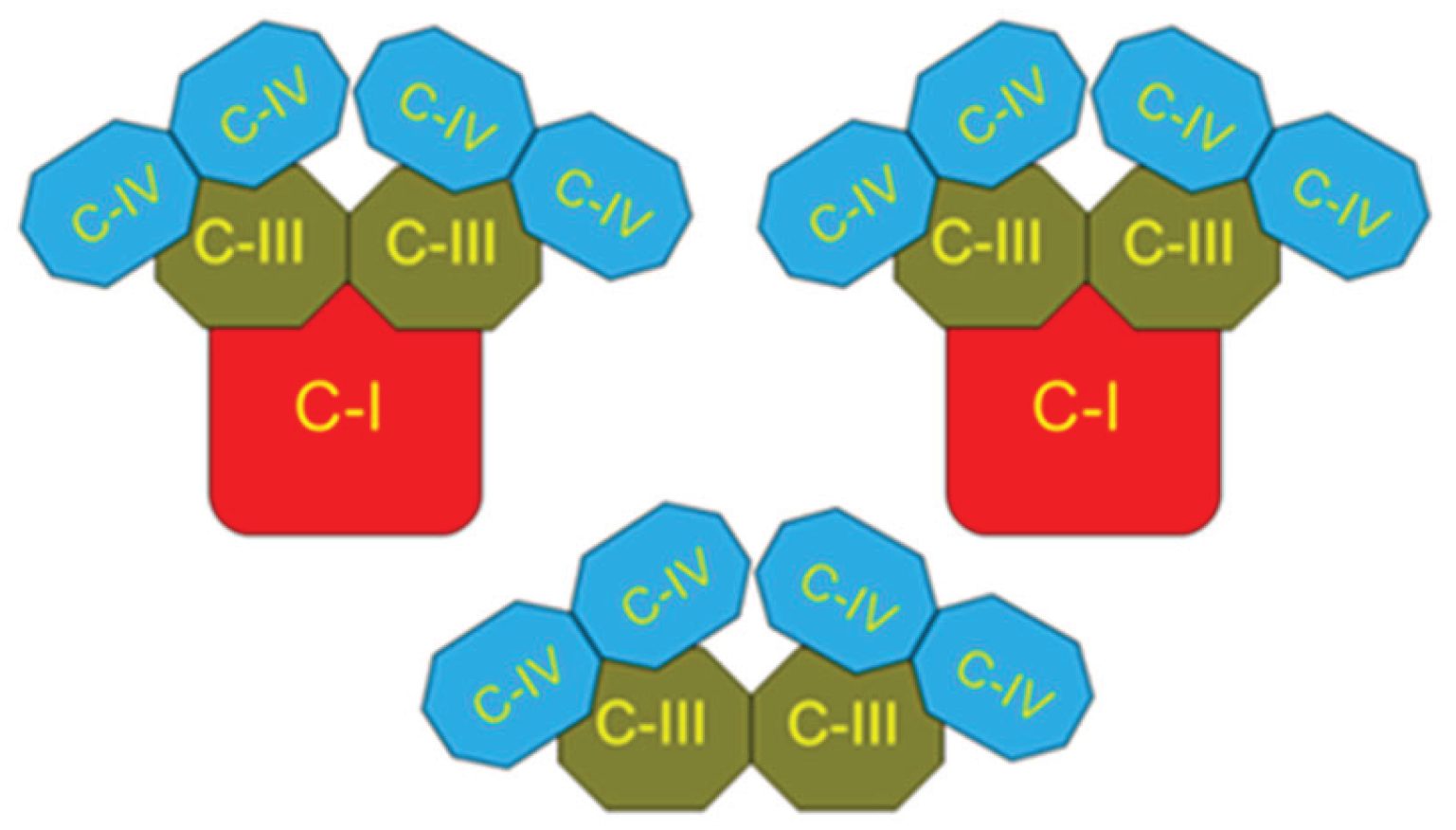

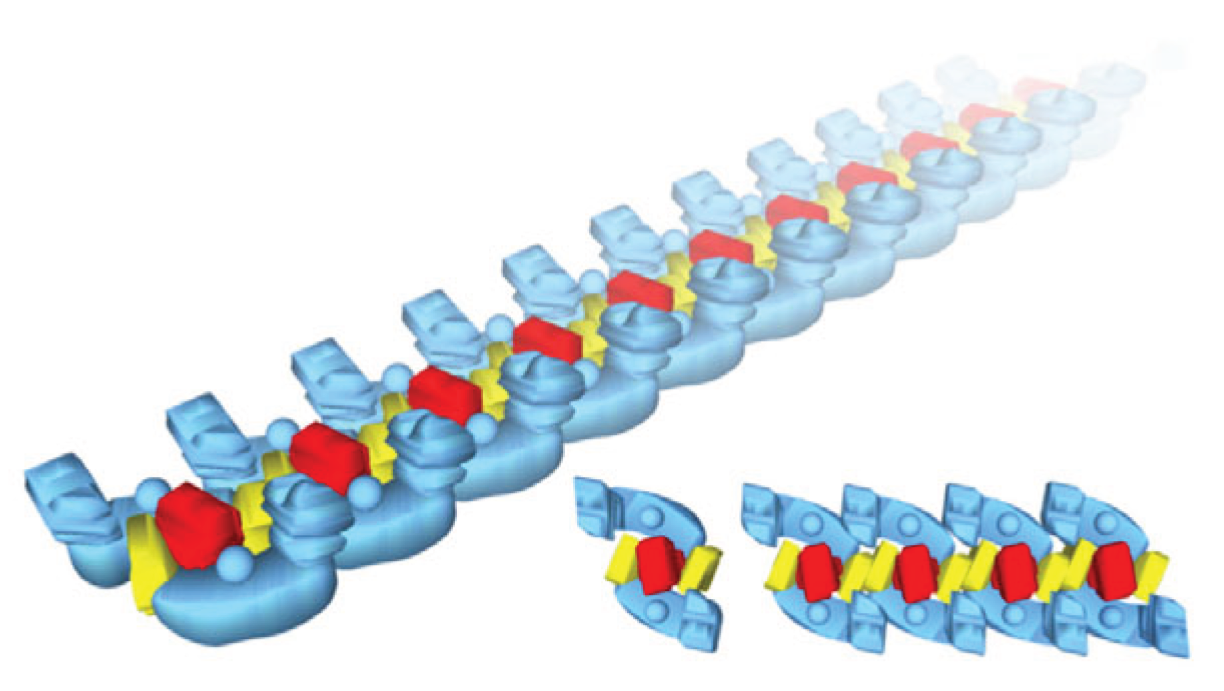

4.2. Respirasome Structure

5. The Key Roles of Fatty Acids β-Oxidation and Lactate Accumulation and Oxiation in Human’s Metabolsim

5.1. Fatty Acids β-Oxidation

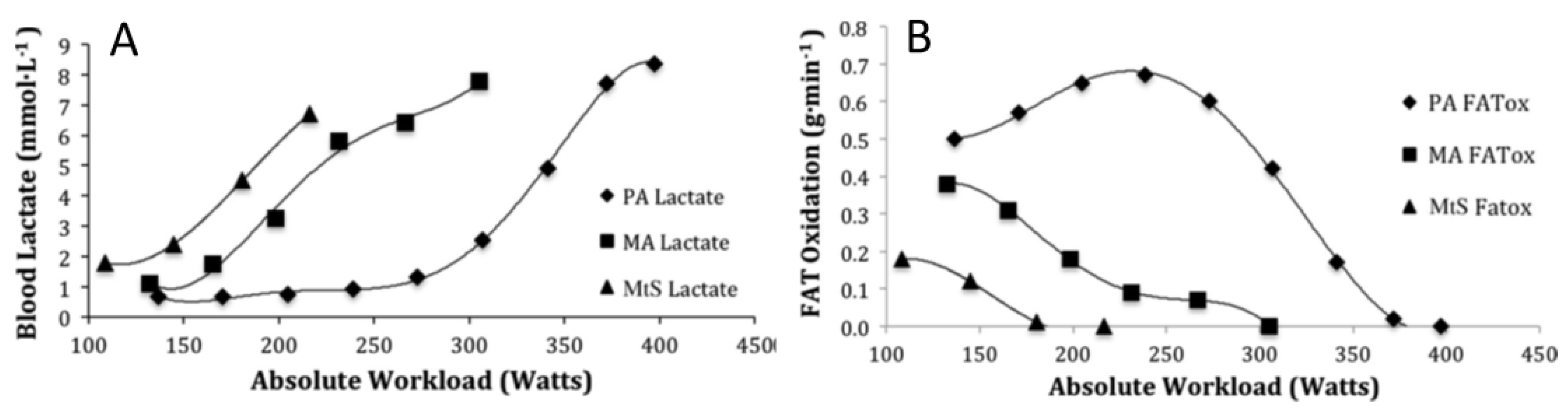

5.2. Oxidation of Lactate and Fatty Acids During Exercise

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swigonova, Z.; Mohsen, A.W.; Vockley, J. Acyl-CoA dehydrogenases: Dynamic history of protein family evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 2009, 69, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagger, H.; Pfeiffer, K. Supercomplexes in the respiratory chains of yeast and mammalian mitochondria. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagger, H. Respiratory chain supercomplexes. IUBMB Life 2001, 52, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mohsen, A.W.; Mihalik, S.J.; Goetzman, E.S.; Vockley, J. Evidence for association of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 29834–29841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.V. The Structure of the Cardiac Mitochondria Respirasome Is Adapted for the Oxidation of Fatty Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, A. R.; Holland, J.T.; Victoria, D.; Kolling, D.R.; Dikanov, S.A.; R. Gilbreth, R.; Lhee, SN.; Kuras, R.; Kuras, M.G. The Q-cycle reviewed: How well does a monomeric mechanism of the bc(1) complex account for the function of a dimeric complex? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1777, 1001–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M. D. Mitochondrial generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the source of mitochondrial redox signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Okamura-Ikeda, K.; Tanaka, K. Purification and characterization of short-chain, medium-chain, and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenases from rat liver mitochondria. Isolation of the holo- and apoenzymes and conversion of the apoenzyme to the holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izai, K.; Uchida, Y.; Orii, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Hashimoto, S.T. Novel fatty acid beta-oxidation enzymes in rat liver mitochondria. I. Purification and properties of very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAndrew, R.P.; Wang, Y.; Mohsen, A.W.; He, M.; Vockley, J.; Kim, J.J. Structural basis for substrate fatty acyl chain specificity: crystal structure of human very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 9435–9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensenauer, R.; He, M.; Willard, J.M.; Goetzman, E.S.; Corydon, T.J.; et al. Human acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-9 plays a novel role in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 32309–32316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouws, J.; Nijtmans, L.; S. M. Houten, S.M.; van den Brand, M.; Huynen, M.; et al. Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase 9 is required for the biogenesis of oxidative phosphorylation complex I. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladden, L.B. Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A.; Arevalo, J.A.; Osmond, J.A.; Leija, A.D.; Curl, R.G.; C.C.; Tovar, A.P. Lactate in contemporary biology: a phoenix risen. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 1229–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.V.; Mayorov, V.I.; Dikalov, S.I. Role of Fatty Acids β-Oxidation in the Metabolic Interactions Between Organs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, W.C.; Recchia, F.A.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1093–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogatzki, M.J.; Ferguson, B.S.; Goodwin, M.L.; Gladden, L.B. Lactate is always the end product of glycolysis. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.C.; Perham, R.N. Purification of 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase multienzyme omplexes from ox heart by new method. Biochem. J. 1980, 191, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeles, Moshe. Corticonics: Neural Circuits of the Cerebral Cortex; Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991; ISSN ISBN 0521374766. [Google Scholar]

- Panov, A.; Schonfeld, P.; Dikalov, S.; Hemendinger, R.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Brooks, B.R. The Neuromediator Glutamate, through Specific Substrate Interactions, Enhances Mitochondrial ATP Production and Reactive Oxygen Species Generation in Nonsynaptic Brain Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14448–14456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, L.; Magistretti, P.J. Neuroenergetics: calling upon astrocytes to satisfy hungry neurons. The Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. Muscle Fuel Utilization with Glycolysis Viewed Right Side Up. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2025, 1478, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Adina-Zada, A.; Zeczycki, T.N.; Attwood, P.V. Regulation of the structure and activity of pyruvate carboxylase by acetyl CoA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 519, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, M. Pyruvate Carboxylase, Structure and Function. Subcell. Biochem. 2017, 83, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panov, A.; Orynbayeva, Z.; Vavilin, V.; Lyakhovich, V. Fatty Acids in Energy Metabolism of the Central Nervous System. Review Article. BioMed. Res. Intern. 2014, 472459. [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff, M.; Nelson, D.; Daikhin, Y.; Erecinska, M. Tricarboxylic acid cycle in rat brain synaptosomes. Fluxes and interactions with aspartate aminotransferase and malate/aspartate shuttle. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 27414–27420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnakumari, L.; Murthy, C.R. Activities of pyruvate dehydrogenase, enzymes of citric acid cycle, and aminotransferases in the subcellular fractions of cerebral cortex in normal and hyperammonemic rats. Neurochem. Res. 1989, 14, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. Lactate as a fulcrum of metabolism. Redox Biol. 2020, 35, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G. A. The Science and Translation of Lactate Shuttle Theory. Cell. Metab. 2018, 27, 757–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D. A. Lactate oxidation at the mitochondria: a lactate-malate-aspartate shuttle at work. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erecinska, M.; Nelson, D. Effects of 3-nitropropionic acid on synaptosomal energy and transmitter metabolism: relevance to neurodegenerative brain diseases. J. Neurochem. 1994, 63, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazanov, L.A.; Jackson, J.B. Proton-translocating transhydrogenase and NAD- and NADP-linked isocitrate dehydrogenases operate in a substrate cycle which contributes to fine regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in mitochondria. FEBS Letters 1994, 344, 109–l16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, L.C.; Franklin, R.B. Bioenergetic theory of prostate malignancy. The Prostate 1994, 25, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.; Orynbaeva, Z. Bioenergetic and antiapoptotic properties of mitochondria from cultured human prostate cancer cells PC-3, DU145 and LNCaP. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panov, A. Practical Mitochondriology. Pitfalls and Problems in Studies of Mitochondria; Lexington, KY, 2013; ISBN 9781483963853. [Google Scholar]

- Panov, A.; Orynbayeva, Z. Determination of mitochondrial metabolic phenotype through investigation of the intrinsic inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase. Analyt. Biochem. 2018, 552, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.; Dikalov, S. Brain energy Metabolism. In Encyclopedia in Biochemstry, 3rd Edition ed; 2021; pp. Pages 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.V.; Mayorov, V.I.; Dikalova, A.E.; Dikalov, S.I. Long-Chain and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids in Energy Metabolism of Murine Kidney Mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, Y. The mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 1015–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, T.; Mills, D.J.; Popot, J.L.; Kuhlbrandt, W. Arrangement of electron transport chain components in bovine mitochondrial supercomplex I1III2IV1. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 4652–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhleip, A.; Flygaard, R.K.; Baradaran, R.; Haapanen, O.; Gruhl, T.; et al. Structural basis of mitochondrial membrane bending by the I-II-III(2)-IV(2) supercomplex. Nature 2023, 615, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Maldonado, M.; Padavannil, A.; Guo, F.; Letts, J.A. Structures of Tetrahymena’s respiratory chain reveal the diversity of eukaryotic core metabolism. Science 2022, 376, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, J.S.; Mills, D.J.; Vonck, J.; Kuhlbrandt, W. Functional asymmetry and electron flow in the bovine respirasome. Elife 2016, 5, e21290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 56th Edition; Weast, Robert C., Ed.; CRC Press; pp. 1975–1976.

- Chretien, D.; Benit, P.; Ha, H.H.; Keipert, S.; El-Khoury, R.; et al. Mitochondria are physiologically maintained at close to 50 degrees C. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadov, S.; Jang, S.; Chapa-Dubocq, X.R.; Khuchua, Z.; Camara, A.K. Mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes in mammalian cells: structural versus functional role. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milenkovskaya, E.; Dowhan, W. Cardiolipin-dependent formation of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2014, 179, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci, S.; Trombetti, F.; Pagliarani, A.; Ventrella, V.; Algieri, C.; et al. Molecular and Supramolecular Structure of the Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation System: Implications for Pathology. Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellino, I.; Sazanov, L.A. SCAF1 drives the compositional diversity of mammalian respirasomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gu, J.; Guo, R.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M. Structure of Mammalian Respiratory Supercomplex I(1)III(2)IV(1). Cell. 2016, 167, 1598–1609.e1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.; Mayorov, V.; Dikalov, S. Metabolic Syndrome and beta-Oxidation of Long-Chain Fatty Acids in the Brain, Heart, and Kidney Mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brischigliaro, M.; Cabrera-Orefice, A.; Arnold, A.; Viscomi, C.; Zeviani, M.; Fernandez-Vizarra, E. Structural rather than catalytic role for mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes. Elife 2023, 12, RP88084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, P.; Moe, A.; Adelroth, A.P. Structure and Mechanism of Respiratory III-IV Supercomplexes in Bioenergetic Membranes. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9644–9673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultema, J.B.; Braun, H.P.; Boekema, E.J.; Kouril, R. Megacomplex organization of the oxidative phosphorylation system by structural analysis of respiratory supercomplexes from potato. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudkina, N.V.; Kouril, R.; Peters, K.; BraunBoekema, H.P. Structure and function of mitochondrial supercomplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2021, 1797, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Zong, S.; Wu, M.; Gu, J.; Yang, M. Architecture of Human Mitochondrial Respiratory Megacomplex I(2)III(2)IV(2). Cell. 2017, 170, 1247–1257 e1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, J.B.; Rydstrom, J. Physiological roles of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1988, 254, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, C.L.; Perevoshchikova, I.V.; Hey-Mogensen, M.; Orr, A.L.; Brand, M.D. Sites of reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria oxidizing different substrates. Redox. Biol. 2013, 1, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevoshchikova, I.V.; Quinlan, C.L.; Orr, A.O.; Gerencser, A.A.; Brand, M.D. Sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production during fatty acid oxidation in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61C, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elustondo, P.A.; White, A.E.; Hughes, M.E.; Brebner, K.; Pavlov, E.; Kane, D.A. Physical and functional association of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) with skeletal muscle mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25309–25317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Oldford, C.; Mailloux, R.J. Lactate dehydrogenase supports lactate oxidation in mitochondria isolated from different mouse tissues. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinok, O.; Poggio, J.L.; Stein, D.E.; Bowne, W.B.; Shieh, A.C.; et al. Malate-aspartate shuttle promotes l-lactate oxidation in mitochondria. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Freire, M.; de Cabo, R.; Bernier, M.; Sollott, S.J.; Fabbri, E.; et al. Reconsidering the Role of Mitochondria in Aging. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Millan, I.; Brooks, G.A. Assessment of Metabolic Flexibility by Means of Measuring Blood Lactate, Fat, and Carbohydrate Oxidation Responses to Exercise in Professional Endurance Athletes and Less-Fit Individuals. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ying, Z.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Zhang, J.; Heller, M.; et al. Evaluation of specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues: comparison between men and women. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vina, J.; Borras, C.; Gambini, J.; Sastre, J.; Pallardo, F.V. Why females live longer than males? Importance of the upregulation of longevity-associated genes by oestrogenic compounds. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 2541–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, J.W.; Melvin, R.G.; Miller, J.T.; Katewa, S.D. Sex differences in survival and mitochondrial bioenergetics during aging in Drosophila. Aging Cell. 2007, 6, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panov, A.V.; Darenskaya, M.A.; Dikalov, S.I.; Kolesnikov, S.I. Metabolic syndrome as the first stage of eldership; the beginning of real aging. In Update in Geriatrics; Published; Somarnyotin, Somchai, Ed.; 14th April 2021; pp. Pp. 37–67. ISBN 978-1-83962-309-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).