Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Experimental Design

Animals and Their Treatment

Measurement of Plasma Glucose, Cholesterol and Triglycerides

FFA Extraction and Determination by Gas Chromatography (GC).

Mitochondria Preparation

Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR)

ATP Biosynthesis

Western Blot Analysis of UCPs, IF1 and Mitochondrial Respiratory Complex V

Statistical Analysis

Results

General Characteristics of Animals

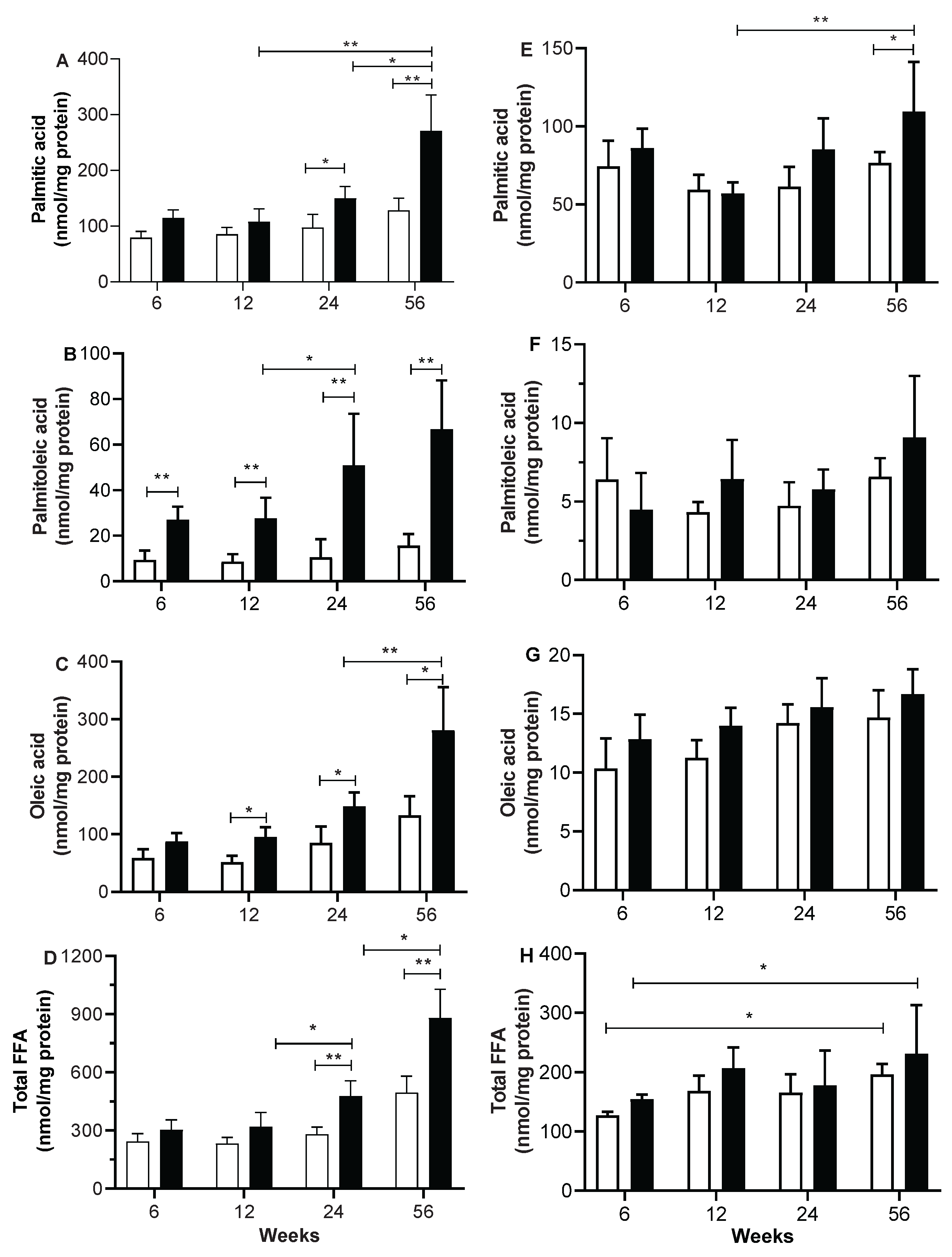

Skeletal and Heart Muscle FFA Content

Mitochondria Oxygen Consumption Rates (OCR)

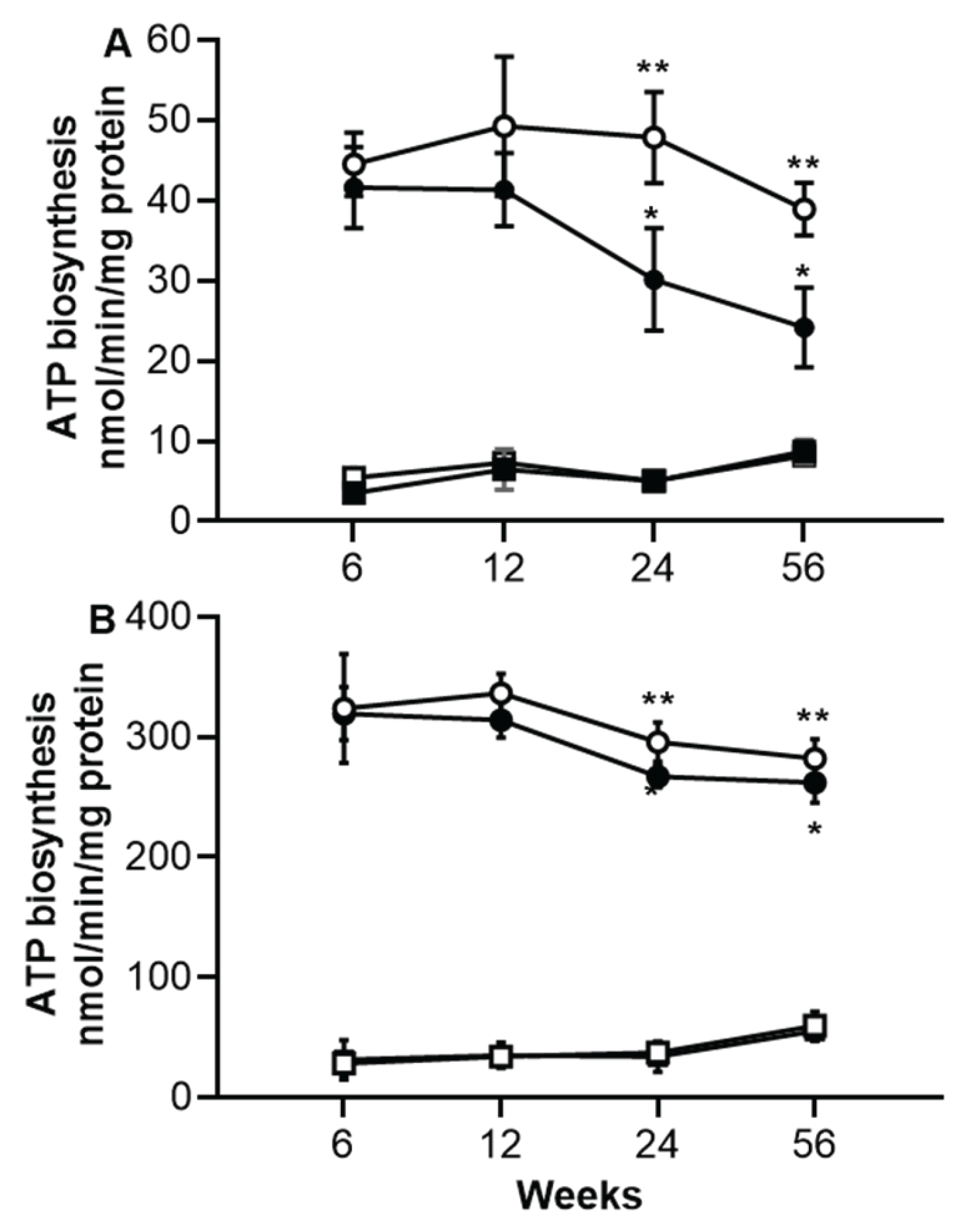

ATP Biosynthesis in Skeletal and Heart Muscles

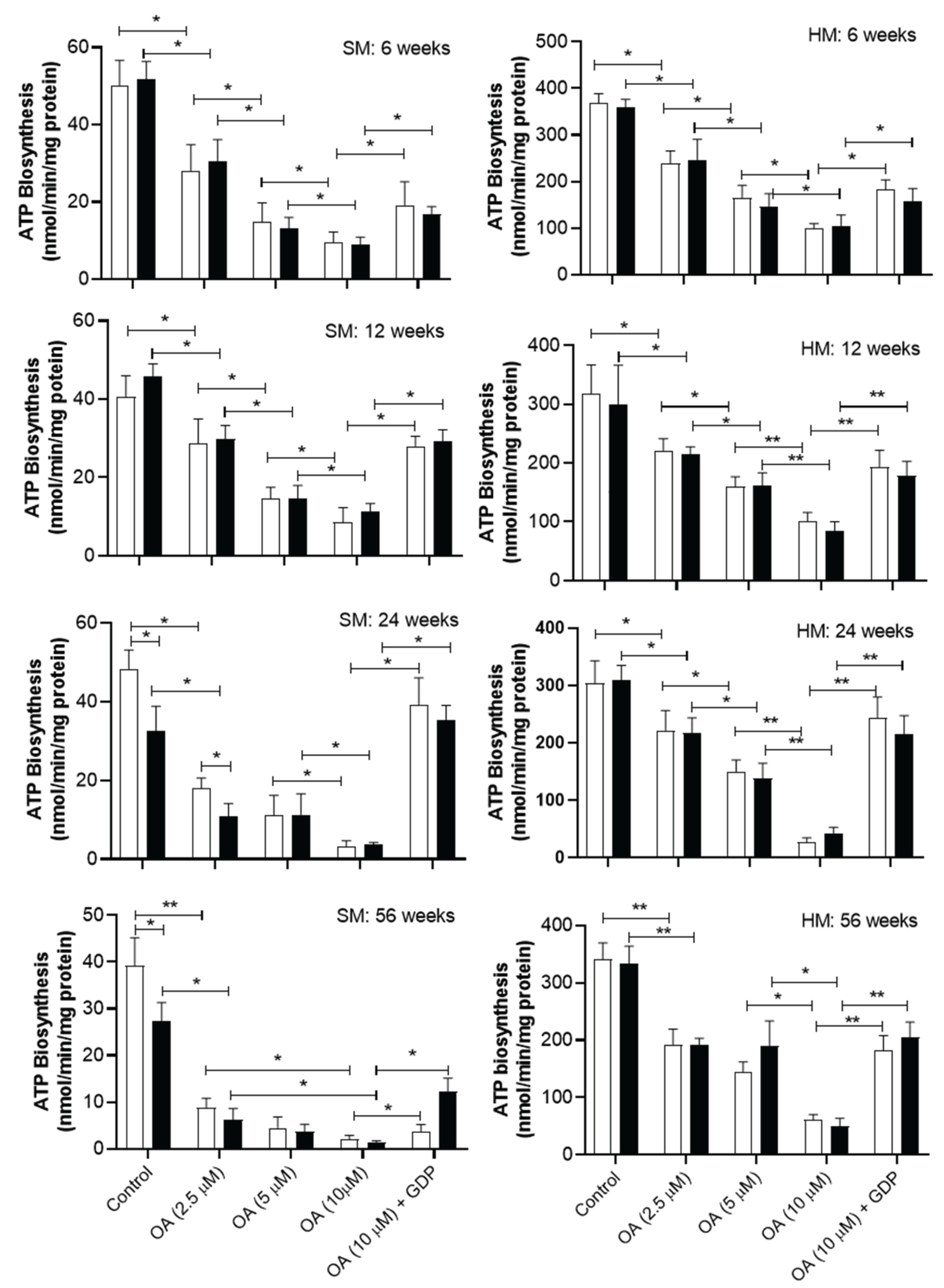

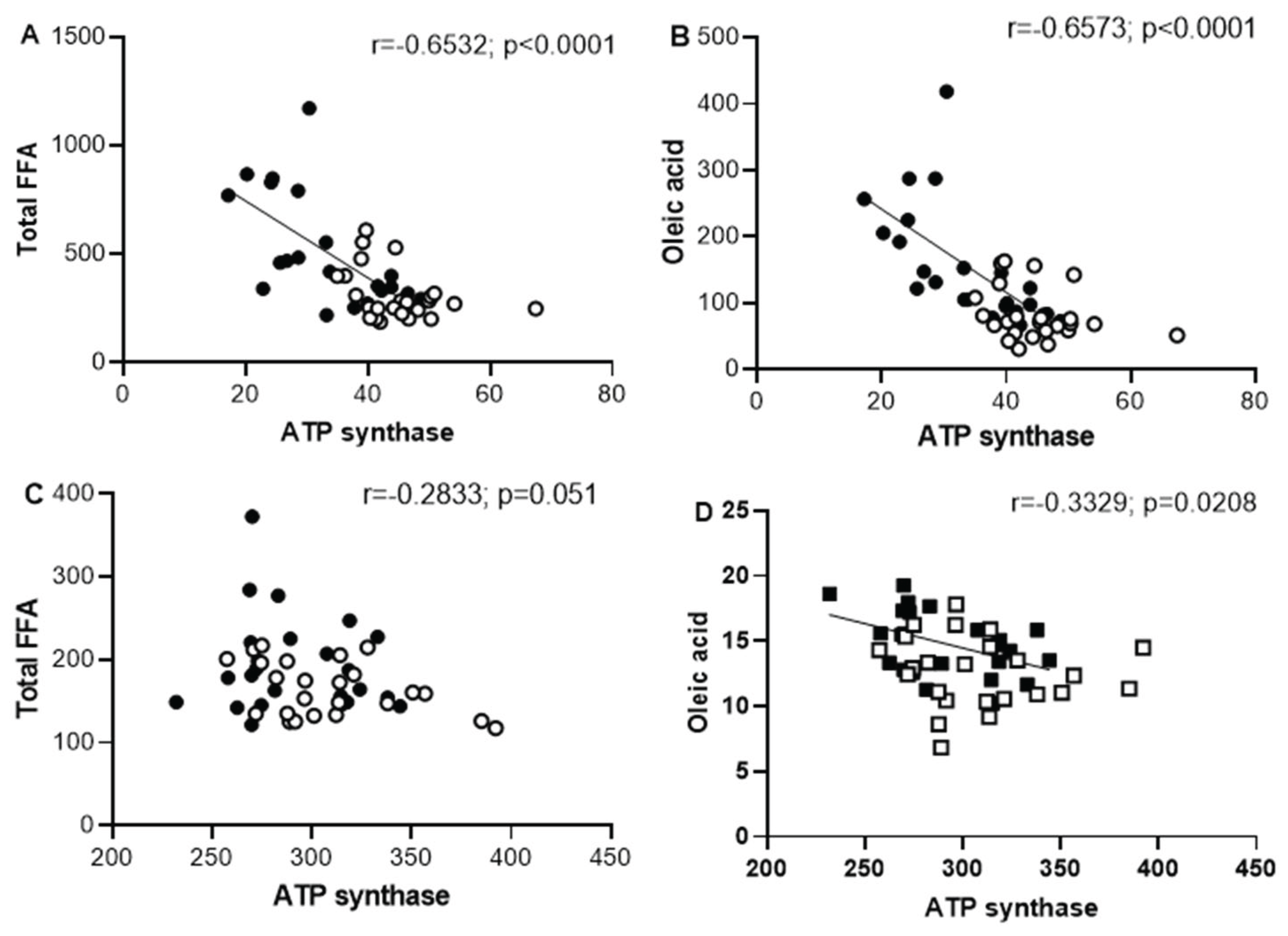

Effect of Oleic Acid on ATP Synthase Activity in Skeletal and Heart Muscles

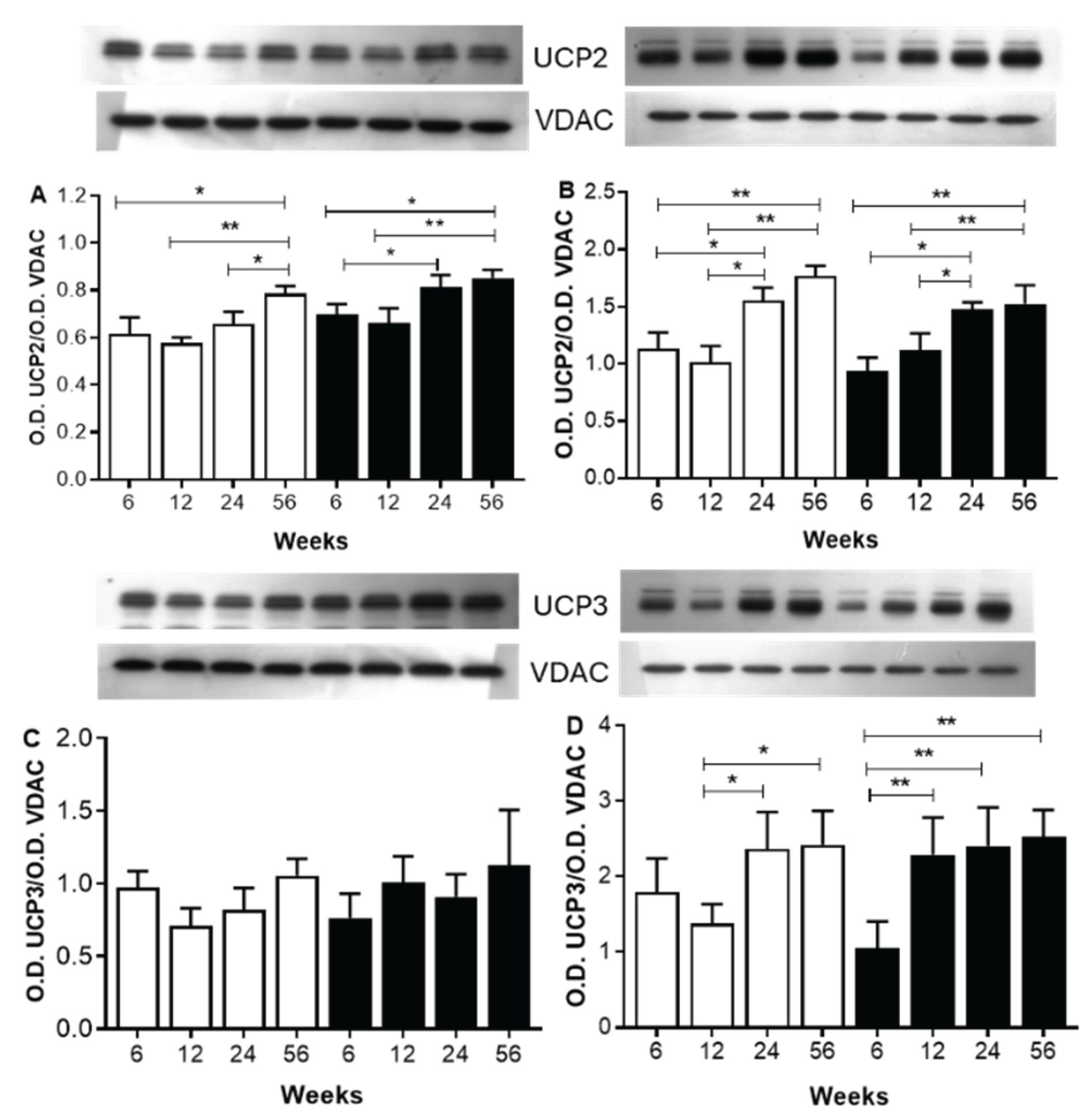

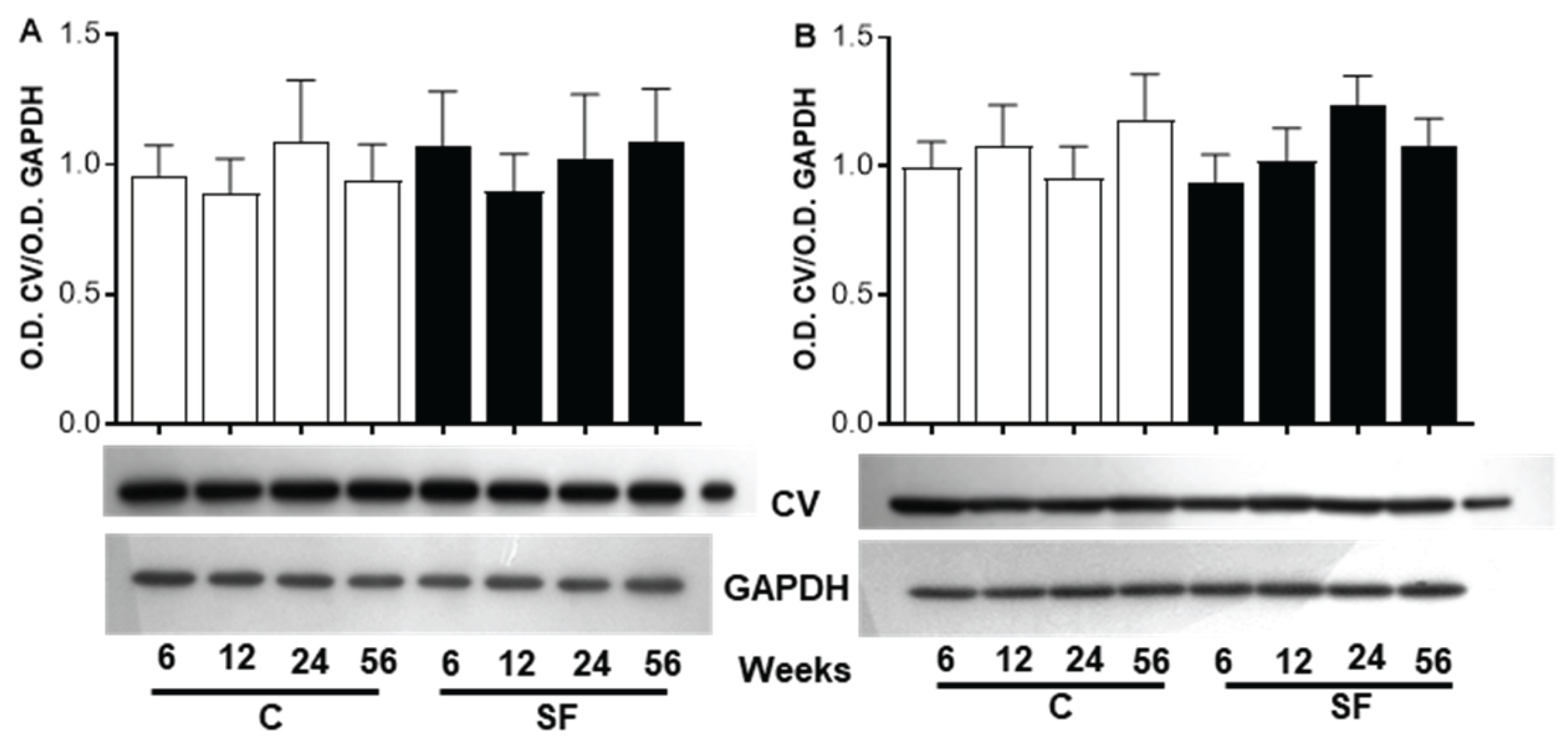

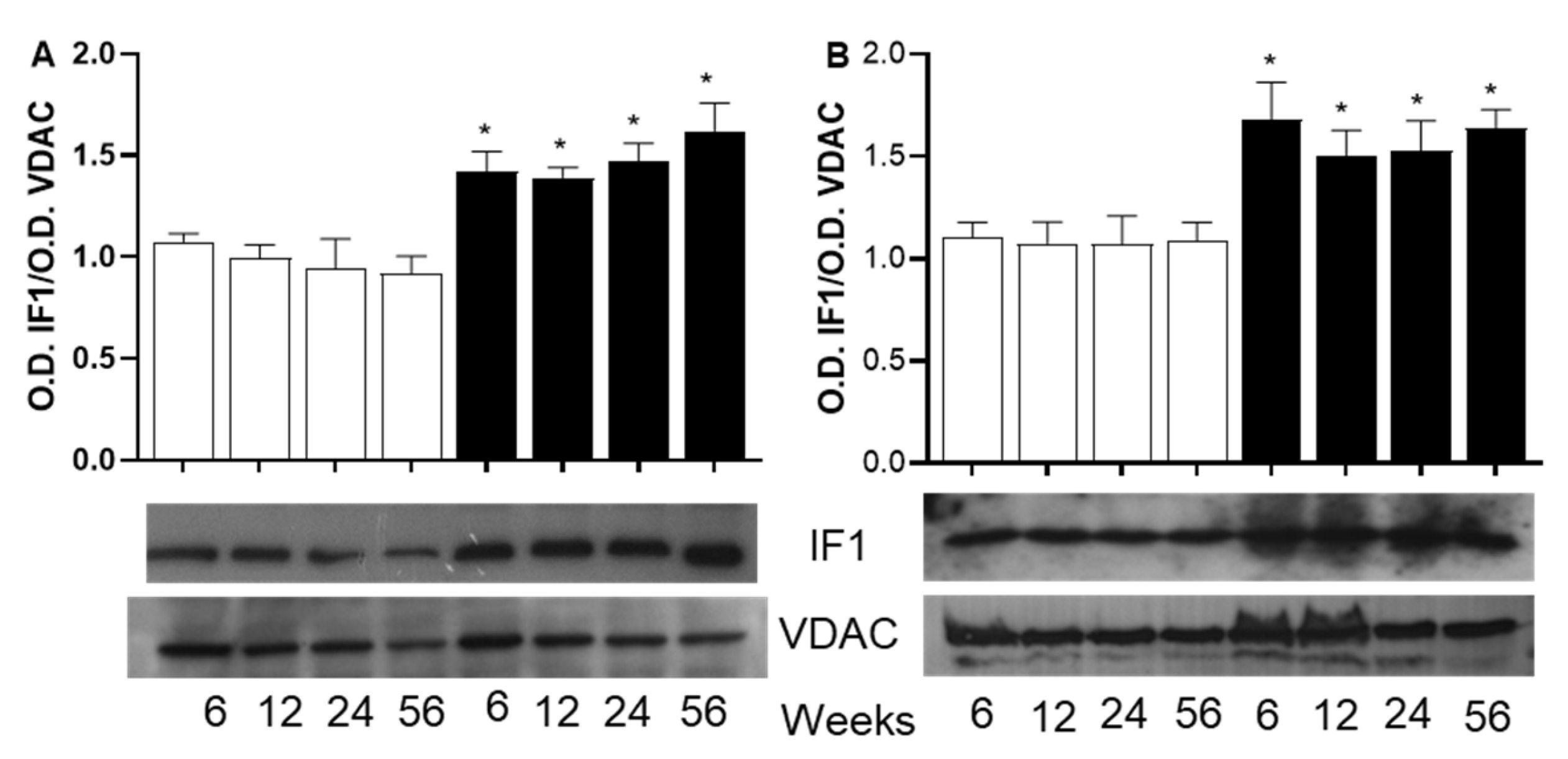

Analysis of Protein Involved in ATP Biosynthesis

Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Shao, S.C. Kolwicz, P. Wang, N.D. Roe, O. Villet, K. Nishi, Y.-W.A. Hsu, G. V. Flint, A. Caudal, W. Wang, M. Regnier, R. Tian, Increasing Fatty Acid Oxidation Prevents High-Fat Diet–Induced Cardiomyopathy Through Regulating Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy. Circulation 2020, 142, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Nesci, S. Rubattu, UCP2, a Member of the Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins: An Overview from Physiological to Pathological Roles. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. Bertholet, A.M. Natale, P. Bisignano, J. Suzuki, A. Fedorenko, J. Hamilton, T. Brustovetsky, L. Kazak, R. Garrity, E.T. Chouchani, N. Brustovetsky, M. Grabe, Y. Kirichok, Mitochondrial uncouplers induce proton leak by activating AAC and UCP1. Nature 2022, 606, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Križančić Bombek, M. Čater, Skeletal Muscle Uncoupling Proteins in Mice Models of Obesity. Metabolites 2022, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Čater, L.K. Križančić Bombek, Protective Role of Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins against Age-Related Oxidative Stress in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Della Guardia, L. Luzi, R. Codella, Muscle-UCP3 in the regulation of energy metabolism. Mitochondrion 2024, 76, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Nabben, J. Hoeks, Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 3 and its role in cardiac- and skeletal muscle metabolism. Physiol Behav 2008, 94, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. D. Lopaschuk, Q.G. Karwi, R. Tian, A.R. Wende, E.D. Abel, Cardiac Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ Res 2021, 128, 1487–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Boudina, Y.H. Han, S. Pei, T.J. Tidwell, B. Henrie, J. Tuinei, C. Olsen, S. Sena, E.D. Abel, UCP3 Regulates Cardiac Efficiency and Mitochondrial Coupling in High Fat–Fed Mice but Not in Leptin-Deficient Mice. Diabetes 2012, 61, 3260–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, M. Mao, Z. Zuo, Palmitate Induces Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism Disorder and Cellular Damage via the PPAR Signaling Pathway in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Volume 2022, 15, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas de Mello, G.K. Ferreira, G.T. Rezin, Abnormal mitochondrial metabolism in obesity and insulin resistance, in: Clinical Bioenergetics, Elsevier, 2021: pp. 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, S. Xu, X. Zhang, Z. Yi, S. Cichello, Skeletal intramyocellular lipid metabolism and insulin resistance. Biophys Rep 2015, 1, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. J. Berry, E. Mjelde, F. Carreno, K. Gilham, E.J. Hanson, E. Na, M. Kaeberlein, Preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential is necessary for lifespan extension from dietary restriction. Geroscience 2023, 45, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Sun, W.Y. Yang, Z. Tan, X.Y. Zhang, Y.L. Shen, Q.W. Guo, G.M. Su, X. Chen, J. Lin, D.Z. Fang, Serum Levels of Free Fatty Acids in Obese Mice and Their Associations with Routine Lipid Profiles. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Volume 2022, 15, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. de O. Lemos, R.S. Torrinhas, D.L. Waitzberg, Nutrients, Physical Activity, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Setting of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Owesny, T. Grune, The link between obesity and aging - insights into cardiac energy metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev 2023, 216, 111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. El Hafidi, A. Cuéllar, J. Ramı́rez, G. Baños, Effect of sucrose addition to drinking water, that induces hypertension in the rats, on liver microsomal Δ9 and Δ5-desaturase activities. J Nutr Biochem 2001, 12, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramírez, M. Chávez-Salgado, J.A. Peñeda-Flores, E. Zapata, F. Masso, M. El-Hafidi, High-sucrose diet increases ROS generation, FFA accumulation, UCP2 level, and proton leak in liver mitochondria, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301 (2011). [CrossRef]

- P. Owesny, T. Grune, The link between obesity and aging - insights into cardiac energy metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev 2023, 216, 111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Drew, S. Phaneuf, A. Dirks, C. Selman, R. Gredilla, A. Lezza, G. Barja, C. Leeuwenburgh, Effects of aging and caloric restriction on mitochondrial energy production in gastrocnemius muscle and heart, American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory. Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2003, 284, R474–R480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. C. Cardoso-Saldaña, N.E. Antonio-Villa, M. del R. Martínez-Alvarado, M. del C. González-Salazar, R. Posadas-Sánchez, Low HDL-C/ApoA-I index is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and coronary artery calcium: a sub-analysis of the genetics of atherosclerotic disease (GEA) study. BMC Endocr Disord 2024, 24, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. H. FOLCH, J., LEES, M., & SLOANE STANLEY, A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar]

- S. C. Tserng, K. Y., Kliegman, R. M., Miettinen, E. L., & Kalhan, A rapid, simple, and sensitive procedure for the determination of free fatty acids in plasma using glass capillary column gas-liquid chromatography. J Lipid Res 1981, 22, 852–858. [Google Scholar]

- M. El Hafidi, I. Pérez, J. Zamora, V. Soto, G. Carvajal-Sandoval, G. Baños, Glycine intake decreases plasma free fatty acids, adipose cell size, and blood pressure in sucrose-fed rats, American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory. Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2004, 287, R1387–R1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. E. Vázquez-Memije, V. Izquierdo-Reyes, G. Delhumeau-Ongay, The insensitivity to uncouplers of testis mitochondrial ATPase. Arch Biochem Biophys 1988, 260, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. Bradford, A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. J. Garcı́a, I. Ogilvie, B.H. Robinson, R.A. Capaldi, Structure, Functioning, and Assembly of the ATP Synthase in Cells from Patients with the T8993G Mitochondrial DNA Mutation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 11075–11081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Front Nutr 9 ( 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Blaak, Characterisation of fatty acid metabolism in different insulin-resistant phenotypes by means of stable isotopes. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2017, 76, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Ceja-Galicia, C.L.A. Cespedes-Acuña, M. El-Hafidi, Protection Strategies Against Palmitic Acid-Induced Lipotoxicity in Metabolic Syndrome and Related Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. Adeva-Andany, N. Carneiro-Freire, M. Seco-Filgueira, C. Fernández-Fernández, D. Mouriño-Bayolo, Mitochondrial β-oxidation of saturated fatty acids in humans. Mitochondrion 2019, 46, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Abdul-Ghani, F.L. Muller, Y. Liu, A.O. Chavez, B. Balas, P. Zuo, Z. Chang, D. Tripathy, R. Jani, M. Molina-Carrion, A. Monroy, F. Folli, H. Van Remmen, R.A. DeFronzo, Deleterious action of FA metabolites on ATP synthesis: possible link between lipotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and insulin resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008, 295, E678–E685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Mei, M. Park, D.A. York, C. Erlanson-Albertsson, Fatty acids and glucose in high concentration down-regulates ATP synthase β-subunit protein expression in INS-1 cells. Nutr Neurosci 2007, 10, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Rzheshevsky, Decrease in ATP biosynthesis and dysfunction of biological membranes. Two possible key mechanisms of phenoptosis. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2014, 79, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Long, X. Zhang, Q. Sun, Y. Liu, N. Liao, H. Wu, X. Wang, C. Hai, Evolution of metabolic disorder in rats fed high sucrose or high fat diet: Focus on redox state and mitochondrial function. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2017, 242, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Schrauwen, M. Hesselink, UCP2 and UCP3 in muscle controlling body metabolism. Journal of Experimental Biology 2002, 205, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hespel, Hyperglycemic diet and training alter insulin sensitivity, intramyocellular lipid content but not UCP3 protein expression in rat skeletal muscles. Int J Mol Med 25 ( 2010. [CrossRef]

- E.E. Pohl, A. E.E. Pohl, A. Rupprecht, G. Macher, K.E. Hilse, Important Trends in UCP3 Investigation. Front Physiol 10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y. HE, N. WANG, Y. SHEN, Z. ZHENG, X. XU, Inhibition of high glucose-induced apoptosis by uncoupling protein 2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med 2014, 33, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Pheiffer, C. Jacobs, O. Patel, S. Ghoor, C. Muller, J. Louw, Expression of UCP2 in Wistar rats varies according to age and the severity of obesity. J Physiol Biochem 2016, 72, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramírez, M. Chávez-Salgado, J.A. Peñeda-Flores, E. Zapata, F. Masso, M. El-Hafidi, High-sucrose diet increases ROS generation, FFA accumulation, UCP2 level, and proton leak in liver mitochondria. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2011, 301, E1198–E1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramirez, O. Lopez-Acosta, M. Barrios-Maya, M. El-Hafidi, Uncoupling Protein Overexpression in Metabolic Disease and the Risk of Uncontrolled Cell Proliferation and Tumorigenesis. Curr Mol Med 2018, 17, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.E. Hilse, A. K.E. Hilse, A. Rupprecht, M. Egerbacher, S. Bardakji, L. Zimmermann, A.E.M.S. Wulczyn, E.E. Pohl, The Expression of Uncoupling Protein 3 Coincides With the Fatty Acid Oxidation Type of Metabolism in Adult Murine Heart, Front Physiol 9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- P. Schrauwen, J. Hoeks, G. Schaart, E. Kornips, B. Binas, G.J. Vusse, M. Bilsen, J.J.F.P. Luiken, S.L.M. Coort, J.F.C. Glatz, W.H.M. Saris, M.K.C. Hesselink, Uncoupling protein 3 as a mitochondrial fatty acid anion exporter. The FASEB Journal 2003, 17, 2272–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, N.N. H. Zhang, N.N. Alder, W. Wang, H. Szeto, D.J. Marcinek, P.S. Rabinovitch, Reduction of Elevated Proton Leak Rejuvenates Mitochondria in the Aged Cardiomyocyte, (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. D. MacLellan, M.F. Gerrits, A. Gowing, P.J.S. Smith, M.B. Wheeler, M.-E. Harper, Physiological Increases in Uncoupling Protein 3 Augment Fatty Acid Oxidation and Decrease Reactive Oxygen Species Production Without Uncoupling Respiration in Muscle Cells. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Della Guardia, L. Luzi, R. Codella, Muscle-UCP3 in the regulation of energy metabolism. Mitochondrion 2024, 76, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Ciapaite, S.J.L. Bakker, M. Diamant, G. Van Eikenhorst, R.J. Heine, H. V. Westerhoff, K. Krab, Metabolic control of mitochondrial properties by adenine nucleotide translocator determines palmitoyl-CoA effects. FEBS J 2006, 273, 5288–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Yang, Q. Long, K. Saja, F. Huang, S.M. Pogwizd, L. Zhou, M. Yoshida, Q. Yang, Knockout of the ATPase inhibitory factor 1 protects the heart from pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. G. Pavez-Giani, P.I. Sánchez-Aguilera, N. Bomer, S. Miyamoto, H.G. Booij, P. Giraldo, S.U. Oberdorf-Maass, K.T. Nijholt, S.R. Yurista, H. Milting, P. van der Meer, R.A. de Boer, J. Heller Brown, H.W.H. Sillje, B.D. Westenbrink, ATPase Inhibitory Factor-1 Disrupts Mitochondrial Ca2+ Handling and Promotes Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy through CaMKIIδ. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Guo, Z. Front Oncol 13 ( 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Domin, M. Pytka, J. Niziński, M. Żołyński, A. Zybek-Kocik, E. Wrotkowska, J. Zieliński, P. Guzik, M. Ruchała, ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1—A Novel Marker of Cellular Fitness and Exercise Capacity? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Diabetes 67 ( 2018. [CrossRef]

| Animals | C | SF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks | 6 | 12 | 24 | 56 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 56 | |

| Variables | |||||||||

| Body mass (g) | 284.8±20.1 | 384.15±2.7 | 552±33.5 | 575.7±46.4 | 259.1±17.7 | 388±35.3 | 572.9±37.4$ | 716.8±50.3*$ | |

| Intrabdominal fat (g) | 2.3±0.9 | 4.3±0.79 | 5.9±1.2 | 8.6±2.9 | 3.4±0.7 | 8.6±1.5*$ | 14.9±2.6*$ | 25.6±5.96*$ | |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 0.8±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 0.9±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.2±0.1* | 1.4±0.2* | 1.8±0.3*$ | 1.7±0.2*$ | |

| Total FFA (µM) | 243.2±40.8 | 248.9±38.9 | 312.8±106.1 | 479.6±113.2 | 353.7±41.7 | 319.7±74.4 | 461.1±87.7*$ | 830.2±202.3*$ | |

| Glucose (mM) | 6.2±0.8 | 4.8±1.9 | 4.9±2.1 | 5.8±0.7 | 5.5±1.1 | 4.6±1.8 | 4.9±1.9 | 6.2±0.7 | |

| Cholesterol (mM) | 1.3±0.2 | 1.5±0.1 | 1.4±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 | 1.4±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.6±0.3 | |

| Animals | C | SF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks | 6 | 12 | 24 | 56 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 56 | |

| OCR | |||||||||

| Mitochondria from skeletal muscle | |||||||||

| State III | 121.0±7.2 | 108.2±16.0* | 79.2±7.1* | 69.9±10.8** | 115.6± 9.15 | 101.1±13.6 | 70.9±13.0$ | 50.08±7.1$$ | |

| State IV | 22.6±5.3 | 23.1±6.5 | 20.8±2.8 | 21.4±3.2 | 22.1±3.1 | 22.1±4.4 | 26.1±2.3& | 27.4±2.8&& | |

| Mitochondria from heart muscle | |||||||||

| State III | 118.8±10.2 | 98.6±9.2 | 89.5±24.8* | 61.7±8.9** | 95.6±14.8 | 92.1±18.2 | 60.4±9.7$ | 50.8±16.4$$ | |

| State IV | 22.4±3.3 | 21.7±2.8 | 18.5±3.4 | 19.3±3.8 | 21.4±4.6&& | 22.8±3.5& | 21.3±2.4& | 23.0±6.6& | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).