Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection Criteria, Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Microbiological Methods

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

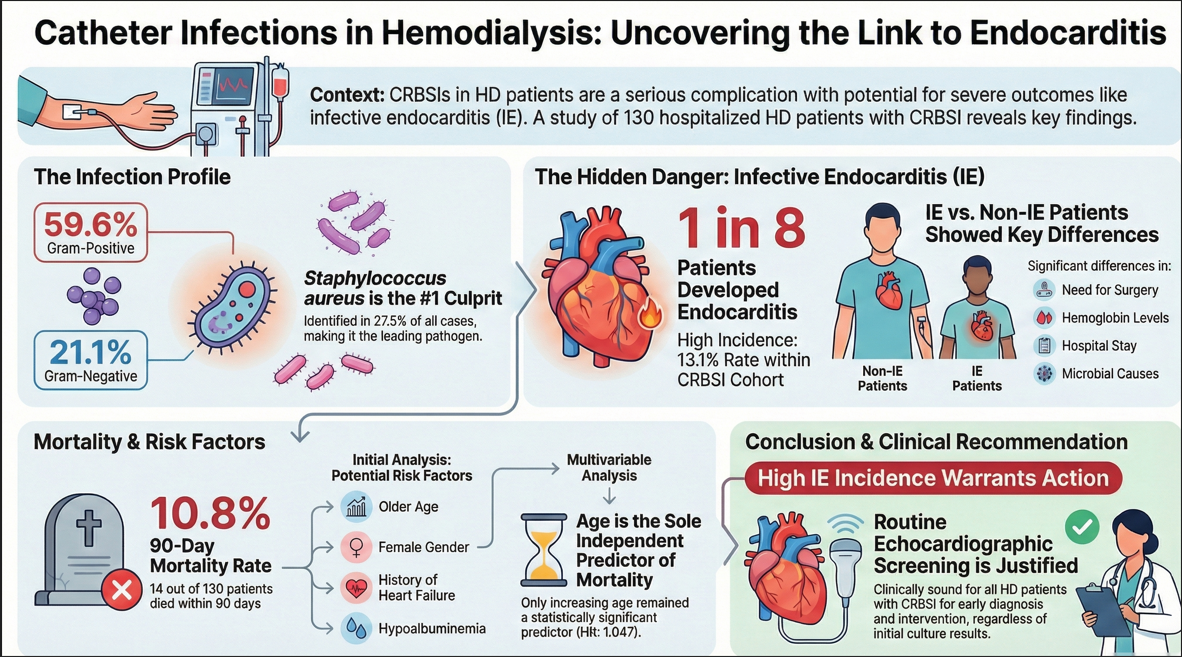

3.1. Demographic Data and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Microbiology Profiles

3.3. Comparison Between Non-IE and IE Patients

3.4. Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRBSI | Catheter-related bloodstream infections |

| CVC | Central venous catheter |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| IE | Infective endocarditis |

| ADPKD | Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease |

Appendix A

- Probable: Symptoms subside with antibiotic therapy with or without catheter removal, and organisms grow only in blood culture with no growth from the catheter tip or not done.

- Possible: Defervescence of symptoms after antibiotic treatment or catheter removal in the absence of laboratory confirmation of bloodstream infection in a symptomatic patient with no other apparent source of infection.

- •

- Blood culture positive for IE:

- ○

- Typical microorganisms consistent with IE from 2 separate blood cultures: Viridans streptococci, Streptococcus bovis, HACEK group, Staphylococcus aureus; or Community-acquired enterococci, in the absence of a primary focus

- ○

- Microorganisms consistent with IE from persistently positive blood cultures, defined as follows: At least 2 positive cultures of blood samples drawn >12 h apart; or

- ○

- All of 3 or a majority of >4 separate cultures of blood (with first and last sample drawn at least 1 h apart)

- ○

- Single positive blood culture for Coxiella burnetii or antiphase I IgG antibody titer >1:800

- •

- Evidence of endocardial involvement,

- •

- Echocardiogram positive for IE(transesophageal echocardiography recommended in patients with prosthetic valves, rated at least “possible IE” by clinical criteria, or complicated IE [paravalvular abscess]; transthoracic echocardiography as first test in other patients), defined as follows:

- ○

- Oscillating intracardiac mass on valve or supporting structures, in the path of regurgitant jets, or on implanted material in the absence of an alternative anatomic explanation; or

- ○

- Abscess; or

- ○

- New partial dehiscence of prosthetic valve

- •

- New valvular regurgitation (worsening or changing of pre-existing murmur not sufficient)

- Predisposition, predisposing heart condition or injection drug use,

- Fever, temperature >380C

- Vascular phenomena, major arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts, mycotic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, conjunctival hemorrhages, and Janeway’s lesions

- Immunologic phenomena: glomerulonephritis, Osler’s nodes, Roth’s spots, and rheumatoid factor

- Microbiological evidence: positive blood culture but does not meet a major criterion as noted abovea or serological evidence of active infection with organism consistent with IE

- Echocardiographic minor criteria eliminated

- Microorganisms demonstrated by culture or histologic examination of a vegetation, a vegetation that has embolized, or an intracardiac abscess specimen; or

- Pathologic lesions; vegetation or intracardiac abscess confirmed by histologic examination showing active endocarditis

- 2 major criteria; or

- 1 major criterion and 3 minor criteria; or

- 5 minor criteria

- 1 major criterion and 1 minor criterion; or

- 3 minor criteria

- Firm alternate diagnosis explaining evidence of infective endocarditis; or

- Resolution of infective endocarditis syndrome with antibiotic therapy for <4 days; or

- No pathologic evidence of infective endocarditis at surgery or autopsy, with antibiotic therapy for <4 days; or

- Does not meet criteria for possible infective endocarditis, as above

References

- Lok, C.E.; Huber, T.S.; Lee, T.; Shenoy, S.; Yevzlin, A.S.; Abreo, K.; Allon, M.; Asif, A.; Astor, B.C.; Glickman, M.H.; et al. KDOQI Clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 Update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, S1–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Yang, Y.S.; Chang, C.Y.; Chen, K.Y.; Lai, J.J.; Lin, J.C.; Chang, F.Y. Microbiological features, clinical characteristics and outcomes of ınfective endocarditis in adults with and without hemodialysis: a 10-year retrospective study in Northern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen Kumar, V.; van der Linden, M.; Menon, T.; Nitsche-Schmitz, D.P. Viridans and bovis group Streptococci that cause infective endocarditis in two regions with contrasting epidemiology. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 304, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, C.A.; Allon, M. Complications of hemodialysis catheter bloodstream infections: impact of infecting organism. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 50, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fysaraki, M.; Samonis, G.; Valachis, A.; Daphnis, E.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Falagas, M.E.; Stylianou, K.; Kofteridis, D.P. Incidence, clinical, microbiological features and outcome of bloodstream infections in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fram, D.; Okuno, M.F.P.; Taminato, M.; Ponzio, V.; Manfredi, S.R.; Grothe, C.; Belasco, A.; Sesso, R.; Barbosa, D. Risk factors for bloodstream infection in patients at a Brazilian hemodialysis center: a case-control study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.; Clark, E.; Dipchand, C.; Hiremath, S.; Kappel, J.; Kiaii, M.; Lok, C.; Luscombe, R.; Moist, L.; Oliver, M.; et al. Hemodialysis tunneled catheter-related infections. Can. J. Kidney Heal. Dis. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravani, P.; Palmer, S.C.; Oliver, M.J.; Quinn, R.R.; MacRae, J.M.; Tai, D.J.; Pannu, N.I.; Thomas, C.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Craig, J.C.; et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.R.; Kallen, A.J.; Arduino, M.J. Epidemiology, surveillance, and prevention of bloodstream infections in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 56, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgaard, L.S.; Nørgaard, M.; Jespersen, B.; Jensen-Fangel, S.; Østergaard, L.J.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Søgaard, O.S. Risk and prognosis of bloodstream infections among patients on chronic hemodialysis:a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elderia, A.; Kiehn, E.; Djordjevic, I.; Gerfer, S.; Eghbalzadeh, K.; Gaisendrees, C.; Deppe, A.C.; Kuhn, E.; Wahlers, T.; Weber, C. Impact of chronic kidney disease and dialysis on outcome after surgery for infective endocarditis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Behdad, S.; Shahsanaei, F. Infective endocarditis and its short and long-term prognosis in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2021, 46, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; He, H.; Wang, L. Risk factors for catheter-associated bloodstream infection in hemodialysis patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, F.; Peighambari, M.M.; Kohansal, E.; Sadeghpour, A.; Moradnejad, P.; Shafii, Z. Comparative analysis of infective endocarditis in hemodialysis versus non-hemodialysis patients in Iran: implications for clinical practice and future research. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Sexton, D.J.; Mick, N.; Nettles, R.; Fowler, V.G.; Ryan, T.; Bashore, T.; Corey, G.R. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000, 30, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, K.L.; Chertow, G.M.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Ishani, A.; Israni, A.; Ku, E.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Obrador, G.T.; et al. US Renal Data System 2022 Annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 81, A8–A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazes, I.; Solignac, J.; Lassalle, M.; Mercadal, L.; Couchoud, C. Twenty years of the French renal epidemiology and information network. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyahi, N.; Koçyiğit, İ.; Ateş, K.; Süleymanlar, G. Current status of renal replacement therapy in Turkey: a summary of 2020 Turkish Society of nephrology registry report. Turkish J. Nephrol. 2022, 31, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, C.S.; Vaz, F.B.; Campos, R.P. Bacteremia and mortality among patients with nontunneled and tunneled catheters for hemodialysis. Int. J. Nephrol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, F.; Feidjel, R.; Laalaoui, R. Hemodialysis catheter-related infection: rates, risk factors and pathogens. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenara-Tejederas, M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A.; Moyano-Franco, M.J.; de Cueto-López, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Salgueira-Lazo, M. Tunneled catheter-related bacteremia in hemodialysis patients: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. A 14-year observational study. J. Nephrol. 2023, 36, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, C.A.; Allon, M. Management of the hemodialysis patient with catheter-related bloodstream infection. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo Bell, E.C.; Chapon, V.; Bessede, E.; Meriglier, E.; Issa, N.; Domblides, C.; Bonnet, F.; Vandenhende, M.A. Central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections: epidemiology and risk factors for hematogenous complications. Infect. Dis. Now 2024, 54, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, V.G.; Justice, A.; Moore, C.; Benjamin, D.K.; Woods, C.W.; Campbell, S.; Reller, L.B.; Corey, G.R.; Day, N.P.J.; Peacock, S.J. Risk factors for hematogenous complications of intravascular catheter-associated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, J.M.; Salazar-Ospina, L.; Roncancio, G.E.; Jiménez, J.N. Staphylococcus aureus colonization increases the risk of bacteremia in hemodialysis patients: a molecular epidemiology approach with time-dependent analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.S.; Park, S.Y.; Bang, D.W.; Lee, M.H.; Hyon, M.S.; Lee, S.S.; Yun, S.; Song, D.; Park, B.W. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of infective endocarditis: impact of haemodialysis status, especially vascular access infection on short-term mortality. Infect. Dis. (Auckl). 2021, 53, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pericàs, J.M.; Llopis, J.; Jiménez-Exposito, M.J.; Kourany, W.M.; Almirante, B.; Carosi, G.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Fortes, C.Q.; Giannitsioti, E.; Lerakis, S.; et al. Infective endocarditis in patients on chronic hemodialysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentata, Y.; Haloui, I.; Haddiya, I.; Benzirar, A.; El Mahi, O.; Ismailli, N.; Elouafi, N. Infective endocarditis in hemodialysis patients: a 10-year observational single center study. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 23, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, N.; Agrawal, S.; Garg, A.; Mohananey, D.; Sharma, A.; Agarwal, M.; Garg, L.; Agrawal, N.; Singh, A.; Nanda, S.; et al. Trends and outcomes of infective endocarditis in patients on dialysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ju, P.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Xue, F. Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes of infective endocarditis between haemodialysis and non-haemodialysis patients in China. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, S.W.; Chen, J.J.; Lee, T.H.; Kuo, G. Surgical versus medical treatment for infective endocarditis in patients on dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, A.; Havers-Borgersen, E.; Østergaard, L.; Petersen, J.K.; Bruun, N.E.; Weeke, P.E.; Kristensen, S.L.; Voldstedlund, M.; Køber, L.; Fosbøl, E.L. Hemodialysis and its impact on patient characteristics, microbiology, cardiac surgery, and mortality in infective endocarditis. Am. Heart J. 2023, 264, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermel, L.A.; Allon, M.; Bouza, E.; Craven, D.E.; Flynn, P.; O'Grady, N.P.; Raad, I.I.; Rijnders, B.J.; Sherertz, R.J.; Warren, D.K. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Total N:130 |

Non Infective Endocarditis n=113 |

Infective endocarditis N:17 |

p | |

| Age in years | 55.5±16.69 | 54.6±17.1 | 52.7±13.9 | 0.664 |

| Sex Female/Male, (Female%) | 55/77 | 46/67 (40.7%) | 9/8 (52.9%) | 0.341 |

| CKD etiology | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (30%) | 34 (30.1%) | 5 (29.4%) | 0.436 |

| Hypertension | 33 (25.4%) | 31 (27.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis |

11 (8.5%) |

9 (8%) |

1 (7.7%) |

|

| ADPKD | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.5%) | 0 | |

| Obstructive reasons | 9 (6.9%) | 7 (6.2%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Others | 14 (10.8%) | 13 (11.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Unknown | 20 (15.4%) | 15 (13.3%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

|

Diabetes mellitus yes/no, (yes%) |

55 (42.3%) | 48/65 (42.5%) | 7/10 (41.2%) | 0.919 |

| Hypertension yes/no, (yes%) | 79 (60.8%) | 69/44 (61.1%) | 10/7 (58.8%) | 0.860 |

| Heart failure, yes/no, (yes%) | 13 (10%) | 10/103 (8.8%) | 3/14 (17.6%) | 0.377 |

| Tunelled catheter, yes/no, (yes%) | 100 (77%) | 85/27 (75.9%) | 14/3 (82.4%) | 0.761 |

| Renal transplantation, yes/no, (yes%) | 25 (19.2%) | 23/90 (20.4%) | 2/15 (11.8%) | 0.524 |

| Catheter time, days | 45 (15-225) | 30 (7-4015) | 75 (25-2740) | 0.520 |

| Vegetation, yes/no, (yes%) | 16 (10.8%) | 2/87 (1.8%) | 14/3 (82.4%) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy, yes/no, (yes%) | 6 (4.6%) | 5/108 (4.4%) | 1/126(5.9%) | 0.576 |

| Embolism yes/no, (yes%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0/113 | 4/13 (23.5%) | <0.001 |

| Surgery yes/no, (yes%) | 4 (3.1%) | 1/112 (0.9%) | 3/14 (17.6%) | 0.007 |

| Mortality in 90 days, yes/no, (yes%) | 14 (10.8%) | 11/102 (9.7%) | 3/14 (17.6%) | 0.394 |

| Mortality in hospital, yes/no, (yes%) | 6 (4.6%) | 5/108 (4.4%) | 1/16 (5.9%) | 0.576 |

| Culture of catheter | 0.123 | |||

| Negative cultures | 21 | 15 (16.1%) | 6 (37.5%) | |

| G-positive | 65 | 57 (53.8%) | 8 (56%) | |

| G-negatif | 23 | 21 (30.1%) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| White blood cells, X103/mL | 9.745 (6.3-13.2) | 9.73 (0.64-44.7) | 10.4 (2.9-20.2) | 0.782 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.2 (8.28-10.8) | 9.4 (6-17) | 8.4 (6.4-11) | 0.036 |

| Lymphocyte, X103/mL | 1.035 (595-1715) | 1.05 (0.06-13) | 1.01 (0.2-2.56) | 0.890 |

| Platelet, X103/mL | 178.5 (134.5-257.8) | 183 (29-496) | 165 (71-431) | 0.557 |

| Neutrophil, X103/mL | 6.88 (44.2-10.7) | 6.8 (0.41-7.3) | 7.4 (1.7-18.8) | 0.866 |

| CRP, mg/L | 109 (55.8-167.3) | 111 (14.7-230) | 107 (44-309) | 0.532 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.4 (3.02-3.6) | 3.4 (1.4-4.8) | 3.2 (2.6-4.2) | 0.120 |

| Hospitalization days | 17.5 (14-29) | 16 (3-165) | 35 (11-105) | <0.001 |

| Distribution of microbial isolates from catheter tip culture | Distribution of microbial isolates from blood culture | ||||

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Negative cultures | 21 | 18.3 | Negative cultures | 31 | 25 |

| Stap Aureus | 30 | 27.5 | Stap Aureus | 31 | 25 |

| G-positive | 35 | 32.1 | G-positive | 34 | 27.4 |

| G-negatif | 23 | 21.1 | G-negatif | 27 | 21.8 |

| Fungus | 1 | 0.8 | |||

| Total | 109 | Total | 124 | ||

| Distribution of microbial isolates from catheter tip culture | ||

| Number | ||

| Negative cultures | 21 | |

| Gram-positive | Staphylococcus aureus | 30 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 15 | |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 2 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 4 | |

| Streptococus mitis | 1 | |

| Kocuria rhizophila | 1 | |

| Diphtheroid basil | 1 | |

| Micrococcus luteus | 1 | |

| Streptecocus oralis | 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 | |

| Enterococcus hirae | 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 7 | |

| Gram-negative | Enterobacteriaceae spp | 1 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 | |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 5 | |

| Enterobacter asburiae | 2 | |

| Rhizobium radiobacter | 1 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 | |

| Moraxella osloensis | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | |

| Pantoea agglomerans | 1 | |

| Distribution of microbial isolates from blood culture | ||

| Number | ||

| Negative cultures | 31 | |

| Gram-positive | Staphylococcus aureus | 31 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 16 | |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 2 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 6 | |

| Streptococus mitis | 1 | |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 1 | |

| Diphtheroid basil | 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 7 | |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 | |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | |

| Klebsiella spp | 1 | |

| Ochrobactrum anthropi | 1 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 | |

| Enterobacteriaceae spp | 1 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 | |

| Enterobacter kobei | 2 | |

| Enterobacter asburiae | 1 | |

| Rhizobium radiobacter | 1 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 5 | |

| Moraxella osloensis | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | 1 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 | |

| Pantoea agglomerans | 1 | |

| Gemella morbillorum | 1 | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | |

| Fungi | Candida glabrata | 1 |

|

Survivors N=116 |

Died N=14 |

P | |

| Age in years | 53.1±16.7 | 64.9±13.1 | 0.012 |

| Sex female/male, (female%) | 45/71 (38.8%) | 10/4 (71.4%) | 0.020 |

| CKD etiology | 0.342 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (31%) | 3 (21.4%) | |

| Hypertension | 29 (25%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 11 (9.5%) | 0 | |

| ADPKD | 4 (3.4%) | 0 | |

| Obstructive reasons | 9 (7.8%) | 0 | |

| Others | 11 (9.5%) | 3 (21.4%) | |

| Unknown | 16 (13.8%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus yes/no, (yes%) | 51/65 (44%) | 4/10 (28.6%) | 0.271 |

| Hypertension yes/no, (yes%) | 73/43 (62.9%) | 6/8 (42.9%) | 0.146 |

| Heart failure, yes/no, (yes%) | 9/107 (7.8%) | 4/10 (28.6%) | 0.035 |

| Tunelled catheter, yes/no, (yes%) | 89/26 (77.4%) | 10/4 (71.4%) | 0.738 |

| Renal transplantation, yes/no, (yes%) | 23/93 (19.8%) | 2/12 (14.3%) | 0.999 |

| Catheter time, days | 30 (7-4015) | 195 (8-2740) | 0.089 |

| Vegetation, yes/no, (yes%) | 13/84 (11.2%) | 3/6 (21.4%) | 0.076 |

| Malignancy, yes/no, (yes%) | 5/111 (4.3%) | 1/13 (7.1%) | 0.502 |

| Embolism yes/no, (yes%) | 4/112 (3.4%) | 0/14 | 0.998 |

| Surgery yes/no, (yes%) | 2/114 (1.7%) | 2/12 (14.3%) | 0.057 |

| Culture of catheter |

0.879 |

||

| Negative cultures | 19 (20%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| G-positive | 56 (58.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | |

| G-negatif | 20 (21.1%) | 3 (21.4%) | |

| White blood cells, X103/mL | 9.3 (0.64-44.7) | 10.7 (1.29-22.9) | 0.311 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.1 (6-17) | 9.6 (7.5-11.2) | 0.350 |

| Lymphocyte, X103/mL | 1.09 (0.06-13.1) | 1.01 (0.35-2.39) | 0.273 |

| Platelet, X103/mL | 179 (29-496) | 195 (64-415) | 0.176 |

| Neutrophil, X103/mL | 6.5 (0.41-7.3) | 9.5 (1.1-20.3) | 0.937 |

| CRP, mg/L | 106 (14.7-309) | 157 (44-226) | 0.059 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.4 (1.4-4.8) | 3.2 (2.1-3.7) | 0.045 |

| Hospitalization days | 17.5 (3-165) | 19 (6-69) | 0.383 |

| Echocardiografic Results | |||

| Ejection fraction % | 65 (27-69) | 60 (30-65) | 0.324 |

| Aortic root (cm) | 2.9±0.3 | 2.9±0.3 | 0.632 |

| Left atrium (cm) | 3.9 (2.6-5.3) | 4.5 (3.4-8.5) | 0.164 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (cm) | 4.7±0.6 | 4.8±0.95 | 0.582 |

| Left ventricular end-sistolic diameter (cm) | 3 (1.8-5.5) | 2.9 (2.7-5.1) | 0.789 |

| Interventricular septum thickness (cm) | 1.2 (0.8-2.1) | 1.1 (1.1-1.3) | 0.314 |

| Left ventricular posterior wall thickness (cm) | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.977 |

| Mitrale E wave (m/s) | 0.8 (0.4-2.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.4) | 0.194 |

| Mitrale A wave (m/s) | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.65 (0.4-1.2) | 0.141 |

| Aort velosility (m/s) | 1.5 (1.1-4.5) | 1.2 (1.1-1.7) | 0.130 |

| Aortic apex gradient (mmHg) | 9 (4.8-81) | 8 (4.8-11.6) | 0.501 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation maximum velocity (m/s) | 2.5 (1.8-5.7) | 2.9 (2.2-3.3) | 0.232 |

| Pulmonary Velocity (m/s) | 1 (0.7-1.8) | 1.1 (0.8-1.2) | 0.995 |

| Segmental movement defect | 20/76 (17.2%) | 3/6 (21.4%) | 0.187 |

| Pericardial effusion (yes/no, yes%) | 21/76 (21.6%) | 1/8 (11.1%) | 0.681 |

| Pulmonary arterial pressure (mmHg) | 37 (28-104) | 45.5 (31-55.6) | 0.225 |

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | 1.010-1.094 | 1.051 | 0.015 | 1.0-1.096 | 1.047 | 0.048 |

| Sex, reference category male | 1.167-13.336 | 3.944 | 0.027 | |||

| Heart failure | 1.240-18.241 | 4.756 | 0.023 | |||

| Catheter duration time | 1.000-1.002 | 1.001 | 0.094 | |||

| Vegetation | 0.718-14.537 | 3.231 | 0.126 | |||

| Need for surgery | 1.225-73.665 | 9.500 | 0.031 | |||

| CRP | 0.999-1.017 | 1.008 | 0.072 | |||

| Albumin | 0.121-0.914 | 0.332 | 0.033 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).