1. Introduction

Climate change is profoundly transforming agricultural systems by altering temperature regimes, reducing water availability, and increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events [

1,

2]. These changes directly threaten crop yields and agricultural productivity, thereby posing growing risks to global food security and to the livelihoods of farmers, particularly in vulnerable regions [

2]. Strengthening farmers’ adaptive capacity is therefore critical for sustaining agricultural production, which requires effective climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies. However, despite substantial efforts to promote adaptive practices, the factors shaping farmers’ adaptation processes remain insufficiently understood [

3]. Among these, institutional capacities play a pivotal role in enabling adaptation [

4], while farmers’ perceptions of public institutions strongly influence their responses to climate risks and their willingness to adopt adaptive strategies [

3,

5]. Understanding these dynamics is essential to advancing the Sustainable Development Goals by aligning climate action with sustainable agricultural development in policy and practice.

Adaptation to climate change requires individuals, communities, businesses, and governments at multiple levels to adjust in order to reduce vulnerability to adverse effects [

6,

7]. Social responses must both mitigate negative impacts and foster sustainable development [

7]. Many adaptation strategies emerge spontaneously at the local level, reflecting sector-specific needs and capacities [

5,

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In agriculture, practices such as rainwater harvesting, crop rotation, zero tillage, residue incorporation, mixed cropping, and the use of organic fertilizers or compost have proven effective in reducing climate impacts while enhancing productivity and sustainability [

5,

6,

7,

10,

12].

According to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, livelihoods in rural areas—notably those of small- and medium-scale farmers and Indigenous communities—are projected to face increasing vulnerability due to diminishing agricultural productivity, shrinking farmable land, and reduced water availability, particularly in Andean and mountainous contexts [

13]. Farmers’ willingness to adopt such adaptive practices is critical for managing agricultural lands under changing climatic conditions. Understanding farmers’ opinions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding climate-smart practices is thus essential to fostering adaptive behaviors [

4,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, farmers’ decisions are complex, shaped both by individual characteristics and by broader external factors [

6]. Institutional conditions—such as access to credit, extension services, and technical education—are particularly influential, as they provide material and organizational support that can foster trust [

6,

18]. Importantly, this trust depends on farmers’ perceptions of institutional performance and legitimacy [

3].

Public agencies play a pivotal role in climate change adaptation by safeguarding community well-being, shaping social expectations, and governing the adaptive capacities of communities [

3,

18,

19,

20]. While sometimes perceived as barriers, public agencies can also catalyze adaptation by fostering social networks, enhancing cooperation between state and civil society, and facilitating multi-stakeholder engagement [

18,

20,

21]. The quality of these relationships is crucial, as farmers’ trust in institutions can determine both their motivation and their ability to respond effectively to climate challenges [

14,

18,

19,

20,

22]. Trust not only supports the implementation of adaptation strategies but also serves as a predictor of behavioral responses and the adoption of innovative practices.

Trust in agricultural agencies is a critical element for fostering cooperation and ensuring effective environmental governance. Conceptually, trust functions as a mechanism that simplifies complex situations and reduces uncertainty, enabling individuals to act with confidence [

3,

23]. At both individual and institutional levels, trust facilitates interactions between citizens and authorities, encouraging compliance with norms and engagement in public initiatives [

3,

22,

23]. From this perspective, trust reflects expectations about institutional performance and citizens’ willingness to delegate responsibilities, which in turn shape attitudes toward sustainability, participation in environmental programs, and the effectiveness of climate governance [

3,

14].

Central Chile is recognized as one of the regions most vulnerable to climate change, particularly in rural areas where smallholder farmers practicing traditional agriculture face structural limitations to adaptation [

13,

24,

25]. Climate projections indicate warming of 2–4 °C and precipitation reductions of up to 40% over the coming decades, trends already evident through increased heatwaves and sustained drying [

26,

27]. These climatic shifts threaten ecosystem services, agricultural productivity, and rural livelihoods, with direct implications for food and water security [

24,

28,

29]. Given that this region is a major contributor to national agricultural output, the vulnerability of annual crops, fruits, and vegetables is particularly concerning, as current cultivation practices have not adapted sufficiently to counteract the predicted impacts [

24,

29,

30]. Although Chile has advanced in climate policy, including the Framework Law on Climate Change (2022), the urgency of locally grounded adaptation measures is especially acute in small-scale agricultural sectors, where climate impacts and socioeconomic vulnerability converge. To address these challenges, a network of public agencies manages programs targeting food security, water management, forest restoration, fire prevention, technical assistance, innovation, and financing; however, participation remains voluntary, and without farmers’ engagement and perceived relevance of climate risks, these instruments are often underutilized.

This study adopts a socio-ecological and governance perspective to examine how institutional trust and local perceptions influence land-use management decisions, with particular attention to farmers’ willingness to adopt adaptive agricultural practices in response to climate change. We focus on the case of the Alhué district in central Chile, a socially vulnerable territory strongly affected by climate change. By examining this context, the study seeks to contribute empirical evidence to the debate on the role of institutional trust in shaping adaptive behaviors in rural communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

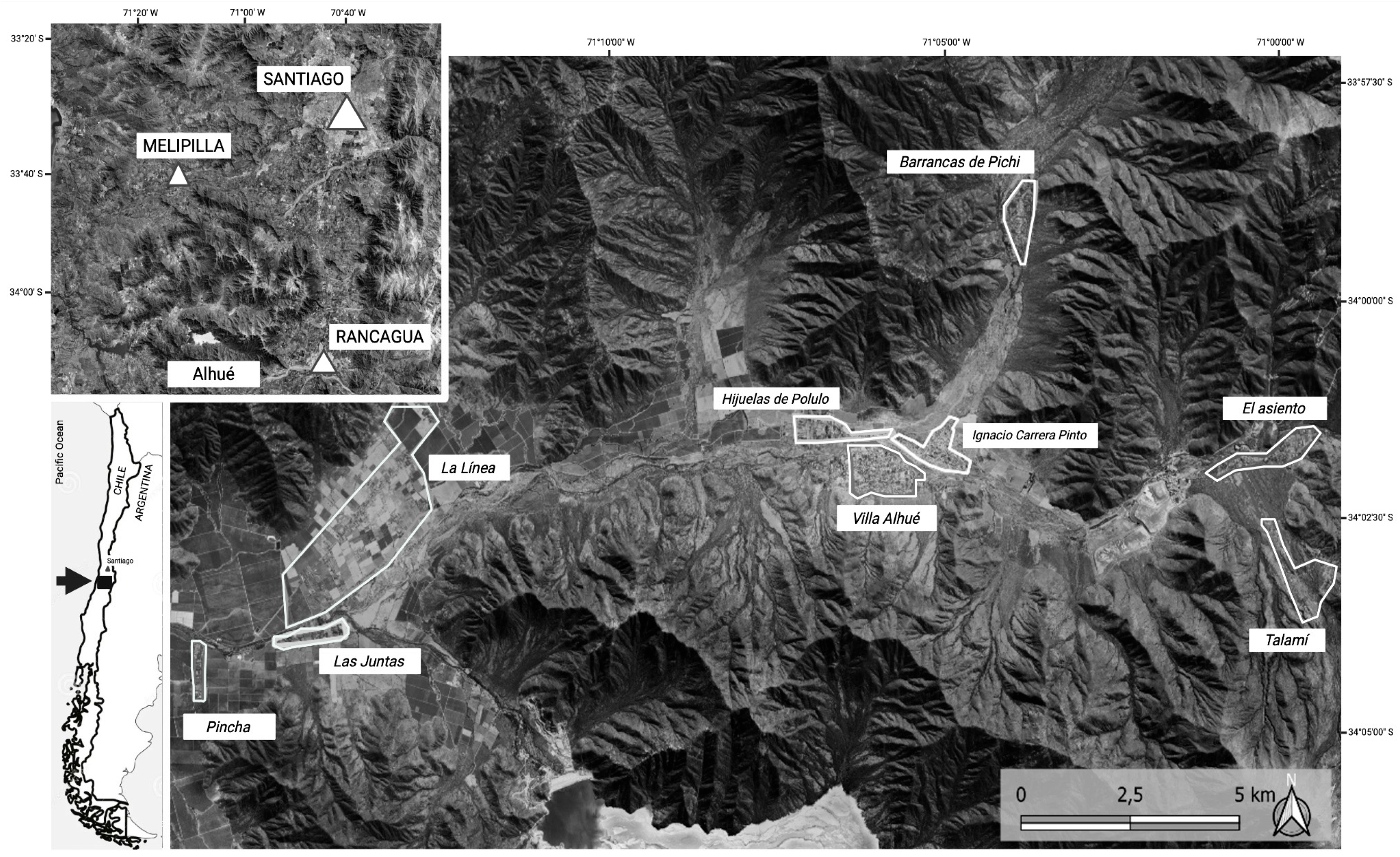

Alhué is a district located in the province of Melipilla, within the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, in central Chile (

Figure 1). Its relative isolation within the valleys of the Altos de Cantillana in the Coastal Mountain Range has contributed to the preservation of a rich cultural and ecological heritage [

31,

32]. At the same time, this isolation, coupled with high vulnerability to climate change, makes Alhué a case study for analyzing the implications of public agencies’ efforts to promote local adaptation. Alhué has a population of 6,444 inhabitants distributed in nine main sectors: Barrancas de Pichi, El Asiento, Hijuelas de Polulo, La Línea, Las Juntas, Pincha, Población Ignacio Carrera Pinto, Talamí, and Villa Alhué (

Figure 1).

The local economy is predominantly based on agriculture, livestock rearing, mining, and public services [

31,

32]. Agricultural households in rural Chilean contexts, such as Alhué, tend to exhibit an aging demographic profile, reflecting higher proportions of older adults and the out-migration of younger cohorts, and are characterized by lower levels of formal education relative to urban populations, even though educational attainment has improved among younger generations. Meanwhile, salaried agricultural workers show somewhat younger age structures but still face challenges in accessing higher education, with relatively low shares of post-secondary educational attainment in the sector [

33,

34].

Alhué also harbors valuable native vegetation dominated by sclerophyllous and deciduous forests, endemic of central Chile. In recent decades, however, these ecosystems have been increasingly displaced by vineyards and fruit plantations, altering ecological dynamics and land-use patterns [

35,

36]. Alhué harbors valuable ecosystems that sustain several endemic species facing critical conservation challenges, while also providing key ecosystem services that contribute in multiple ways to human well-being [

36]. In terms of environmental governance, a conservation landscape concept was developed and institutionalized in the Communal Development Plan [

32,

37]. This plan aimed to integrate sustainability principles into communal land-use planning through participatory workshops with the local community.

Local farmers are generally value-driven and rule-following, engaging with institutions when provided with relevant training and technical support [

31,

38]. Landholders in Alhué tend to have a positive perception of environmental public agencies, such as the National Forest Corporation (CONAF), and this perception is closely linked to their level of knowledge of forest regulations [

38]. Residents also demonstrate deep ecological knowledge of their surrounding woodlands [

32]. While the relative isolation of Alhué’s smallholders fosters strong traditional knowledge and partial self-sufficiency, it also constrains their integration into markets, services, and institutional frameworks that could enhance agricultural intensification and broader climate adaptation.

Overall, Alhué represents a unique socio-ecosystem of central Chile’s rural challenges, where ecological richness, socioeconomic vulnerability, and climate pressures converge. This combination makes it an ideal setting for examining how public institutions and local perceptions interact to shape adaptation pathways in smallholder agriculture.

2.2. Sampling Strategy

Sampling followed a systematic protocol with random selection in the nine settlements of Alhué, which comprised: (i) semi-urban settlements characterized by higher demographic density, access to basic services, local markets, and administrative presence, such as Villa Alhué and Ignacio Carrera Pinto; (ii) rural settlements strongly influenced by agroindustrial and mining activities, including Pincha, Las Juntas, La Línea, Las Hijuelas de Polulo, and El Asiento; and (iii) rural settlements distinguished by their high landscape naturalness, the presence of protected areas, and dispersed housing patterns, such as Barrancas de Pichi and Talamí. In each visited household, one adult respondent was invited to participate in the questionnaire. Ethical principles were ensured by obtaining informed consent from all participants (011494/2020-Comité de Ética, Universidad de Santiago de Chile,)

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire administered to residents engaged in local agricultural activities, including subsistence farming, commercial production, and salaried agricultural work. The questionnaire collected information on: (i) willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices (outcome variable); (ii) trust in Chilean environmental agencies (key explanatory variable); and (iii) a set of control variables, including (a) local knowledge of environmental leverage points, (b) perceptions of climate change impacts, and (c) respondents’ sociodemographic and occupational characteristics.

i) Outcome variable: Willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices: We assessed farmers’ willingness to adopt agricultural practices aimed at improving farm management and mitigating the impacts of climate change in Alhué. We focused on crop rotation, no-till cultivation, mixed cropping, rainwater harvesting, incorporation of crop residues or stubble, and the use of organic fertilizers or compost, drawing on practices identified in similar studies conducted in other regions [

5,

6,

10,

12,

39]. To facilitate comprehension, illustrative images were provided for each practice to help respondents visualize both the concept and its potential application in real contexts. Following a Likert-type structure, participants were asked: “How willing are you to adopt [the agricultural practice]?” Responses were recorded on a six-point ordinal scale, ranging from 1 = “Totally unwilling” to 6 = “Totally willing.” An overall index of willingness to adopt adaptive practices was obtained by calculating the mean across all practices.

ii) Explanatory variable: Trust in Chilean environmental agencies: The level of trust was assessed for a set of national and local agencies, including the Institute for Agricultural Development (INDAP), Local Development Program (PRODESAL), Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI), Office of Agricultural Studies and Policies (ODEPA), National Forest Corporation (CONAF), Agricultural and Livestock Service (SAG), Alhué Environmental Office (OFMA), Foundation for Agricultural Innovation (FIA), Center for Natural Resources Information (CIREN), and Institute for Agricultural Research (INIA). To facilitate recognition, respondents were provided with illustrative sheets displaying the official logo of each agency. Participants were then asked: “To what extent do you trust [environmental agency]?” Responses were recorded on a six-point ordinal scale, ranging from 1 = “No trust at all” to 6 = “Complete trust.” An overall trust index was constructed by averaging the scores across all agencies, also following a Likert-type structure.

iii) Control variables

a) Knowledge of environmental governance leverage points. This variable aimed to assess farmers’ knowledge of key elements in governance systems, as such knowledge may influence their willingness to adapt to climate change. We measured the level of knowledge about actions implemented in Alhué that relate to leverage points in governance systems [

40]. Leverage points are understood as actions capable of generating or triggering substantial and transformative impacts on system functioning [

40]. The set of actions considered included: nature sanctuaries or national reserves; nurseries or greenhouses; native forest reforestation activities, actions, or plans; beekeeping ordinance or recycling legislation; fire alarm systems; recycling and/or composting processes; environmental education activities and workshops; municipal environmental committee; local organizations for nature defense; Community Development Direction (DIDECO) actions; organic and/or agroecological agricultural practices; and initiatives integrating local community knowledge for nature protection. Respondents were asked: “Do you know if [the action] has been implemented in Alhué?” If they answered yes, they were prompted to provide further information. Answers were coded as 1 when the information provided was correct. The knowledge index was constructed by summing the scores across all actions.

b) Perception of climate change impacts: One of the psychological dimensions that influence adaptation decisions is the perception of climate change impacts [

41]. To capture this dimension, respondents were asked to report perceived changes in Alhué over the past 20 years, using native vegetation, crops and agricultural activity, abundance of fauna (including birds and native animals), and insect abundance as proxies. Responses for each proxy were recorded on a six-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 = “Totally decreased” to 6 = “Totally increased”. An index of perceived climate change impacts was constructed by averaging the scores across proxies.

c) Demographic and socioeconomic attributes. Respondents were asked about their age, level of schooling, household income, gender, and locality of residence. Household income was measured in categorical ranges of Chilean pesos (CLP), as follows: 1 = Less than CLP $300,000; 2 = CLP $301,000–500,000; 3 = CLP $501,000–800,000; 4 = CLP $801,000–1.2 million; 5 = CLP $1.2–2 million; 6 = CLP $2–3 million; 7 = More than CLP $3 million. These categories follow the household social registry, distributed by quintiles, and implemented by the Ministry of Social Development and Family through the CASEN Survey.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To construct the indexes, we applied principal component analysis (PCA) to identify variables that could be grouped into common factors and used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the reliability and internal consistency of each set of variables.

To estimate associations, we fitted a set of ordered logistic regression models to examine the relationship between willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices and trust in environmental agencies, while controlling for relevant covariates. A squared term of the trust variable was included to capture potential non-linear associations. Regression models were estimated using the Huber–White robust variance estimator to obtain consistent standard errors in the presence of possible model misspecification. We also clustered the standard errors by settlement of residence to account for intragroup correlation, thereby relaxing the assumption of independent observations.

Model selection was based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) for small sample sizes [

42]. Models were ranked according to their AICc values, and the best-fitting (core) model was identified as the one with the lowest AICc. In addition, we retained as candidate models all models with ΔAICc < 2 relative to the top-ranked model.

3. Results

The sample of farmers who responded to the questionnaire was characterized primarily by middle-aged adults (45–64 years). Most respondents reported monthly household incomes between CLP 301,000 and 500,000. In terms of education, the majority had completed secondary education. Regarding knowledge of environmental governance leverage points, respondents exhibited a moderate level of awareness, with an average score of 6 on a 12-point scale, reflecting the number of actions related to leverage points recognized by each individual.

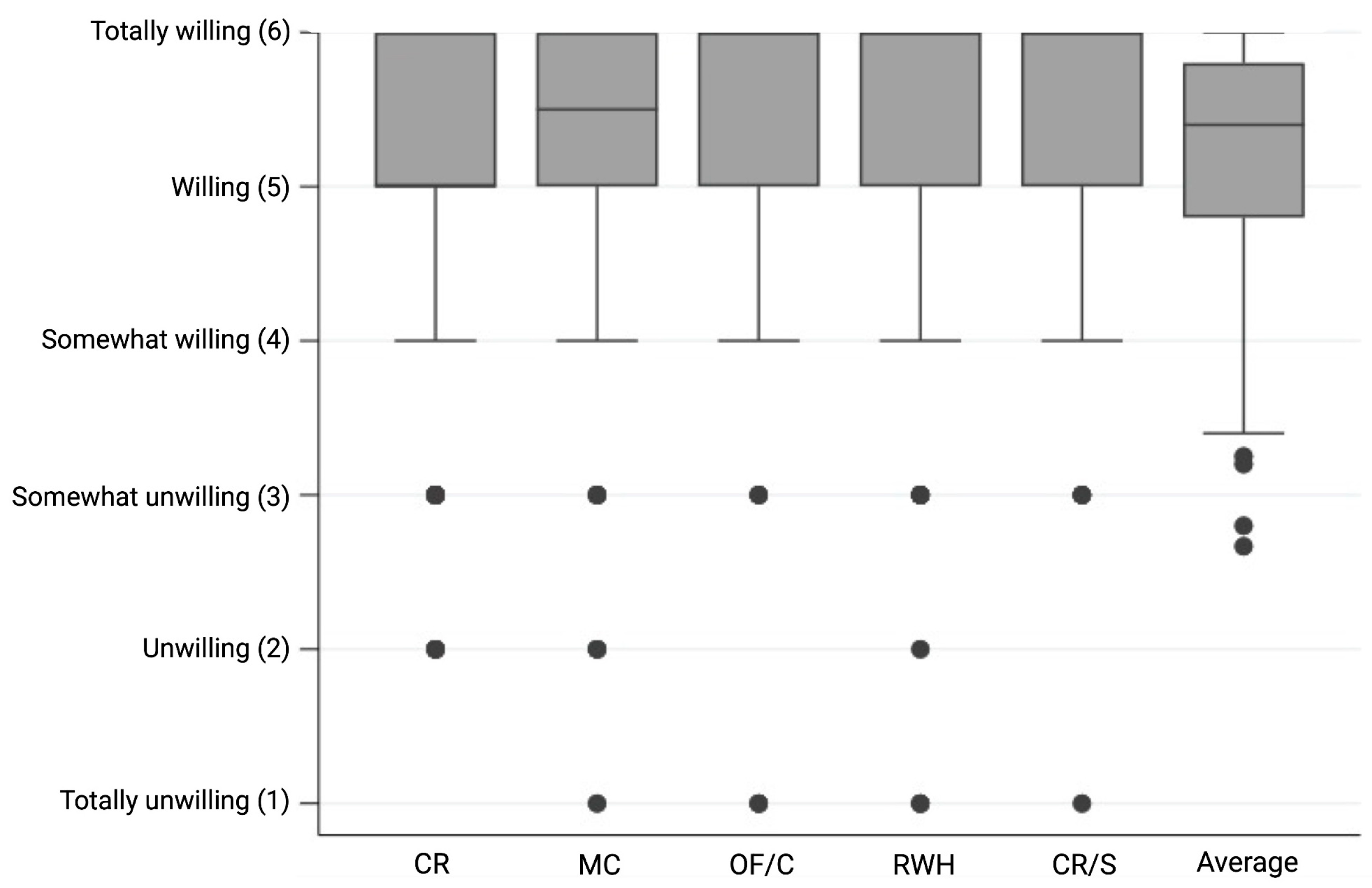

Willingness to adopt adaptive practices showed an average value of 4.9 (SD = 0.9; median = 5, range = 2–6) on the six-point scale (

Table 1). Item-level statistics indicated mean scores of 5.1 (SD = 1.1, median = 5, range = 2–6) for crop rotation, 5.2 (SD = 1.1, median = 5, range = 1–6) for mixed cropping, 5.4 (SD = 1.0, median = 6, range = 1–6) for organic fertilization, 5.1 (SD = 1.2, median = 6, range = 1–6) for rainwater harvesting, and 5.4 (SD = 0.9, median = 6, range = 1–6) for the incorporation of crop residues into the soil (

Figure 2). Differences across practices were not statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ² = 4.1, p = 0.34). All five practices loaded on a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.95), with internal consistency reflected by Cronbach's α of 0.79.

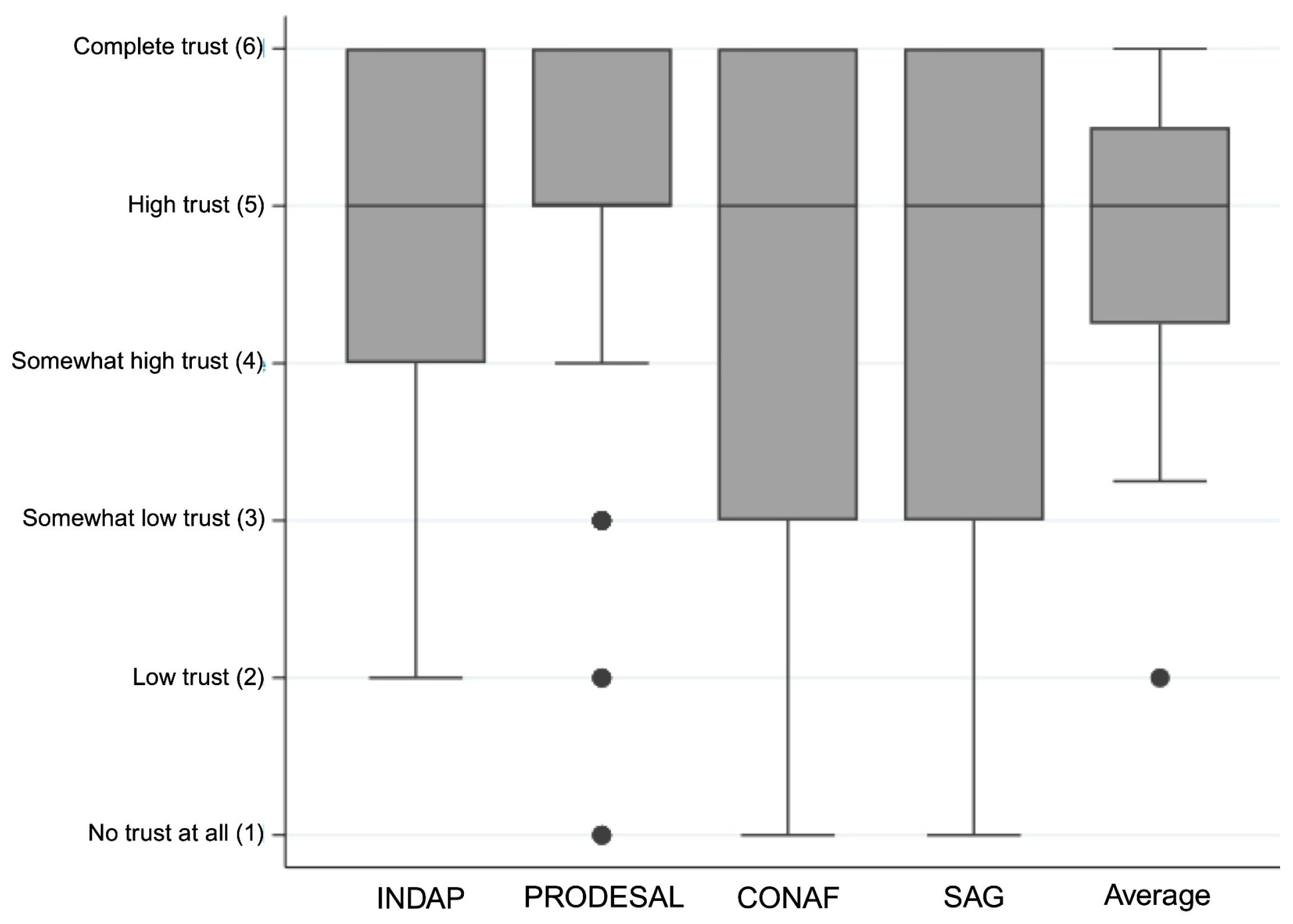

Trust in environmental agencies averaged 4.3 (SD = 1.2; median = 5, range = 1–6). Item-specific results showed mean scores of 4.8 (SD = 1.0, median = 5, range = 2–6) for INDAP, 5.0 (SD = 1.1, median = 5, range = 1–6) for PRODESAL, 4.3 (SD = 0.9, median = 5, range = 1–6) for CONAF, and 4.4 (SD = 0.9, median = 4, range = 1–6) for SAG (

Figure 3). Trust differed significantly among agencies (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ² = 16.5, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that PRODESAL scored higher than INDAP (Mann–Whitney U test: z = 1.8, p = 0.07), CONAF (z = 3.2, p = 0.001), and SAG (z = 3.5, p < 0.001), whereas INDAP scored higher than CONAF (z = 2.0, p = 0.04) and SAG (z = 2.4, p = 0.01). No significant differences were observed between CONAF and SAG (z = 0.09, p = 0.92). All four trust items loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.3), with Cronbach’s α = 0.74.

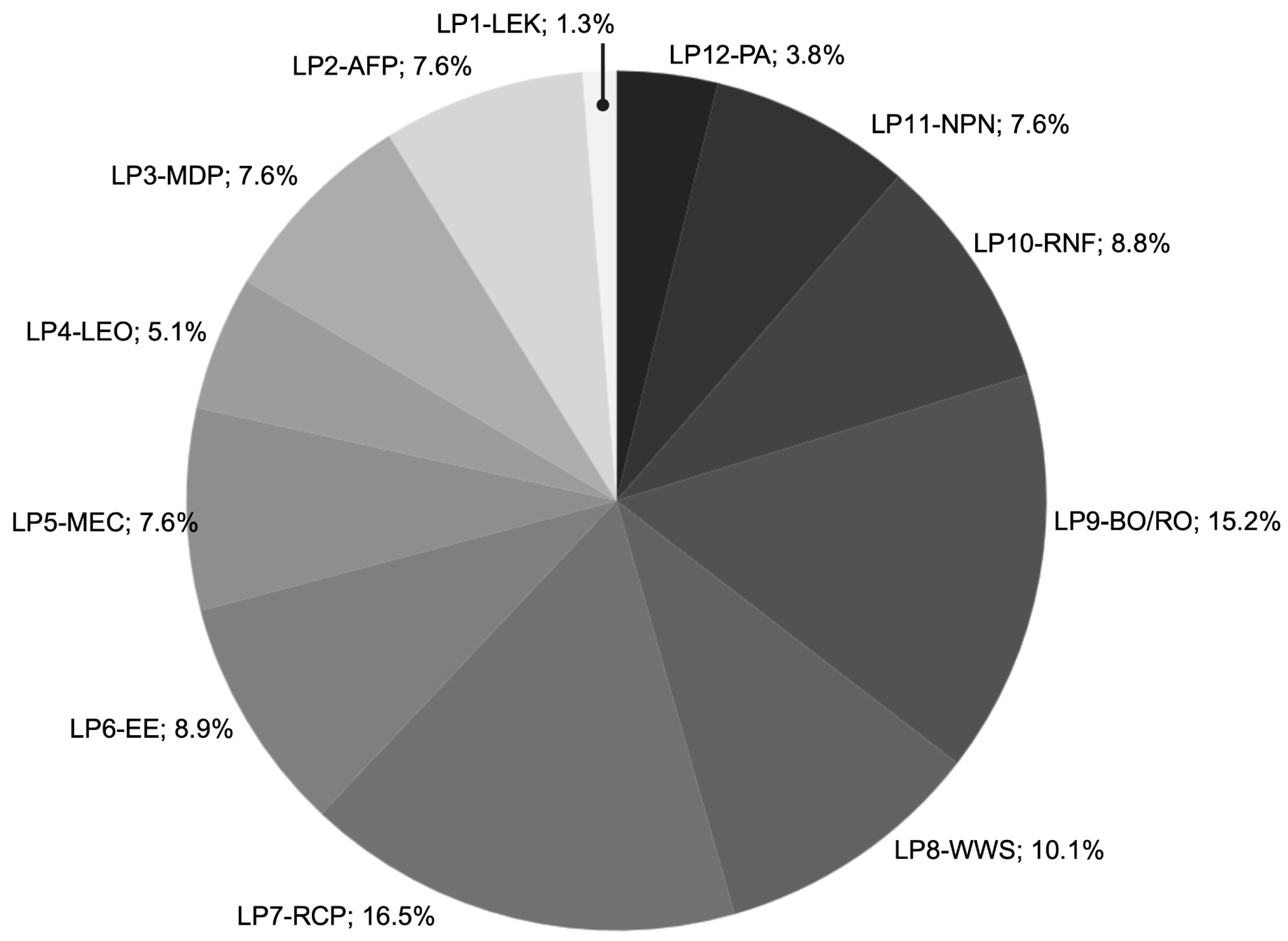

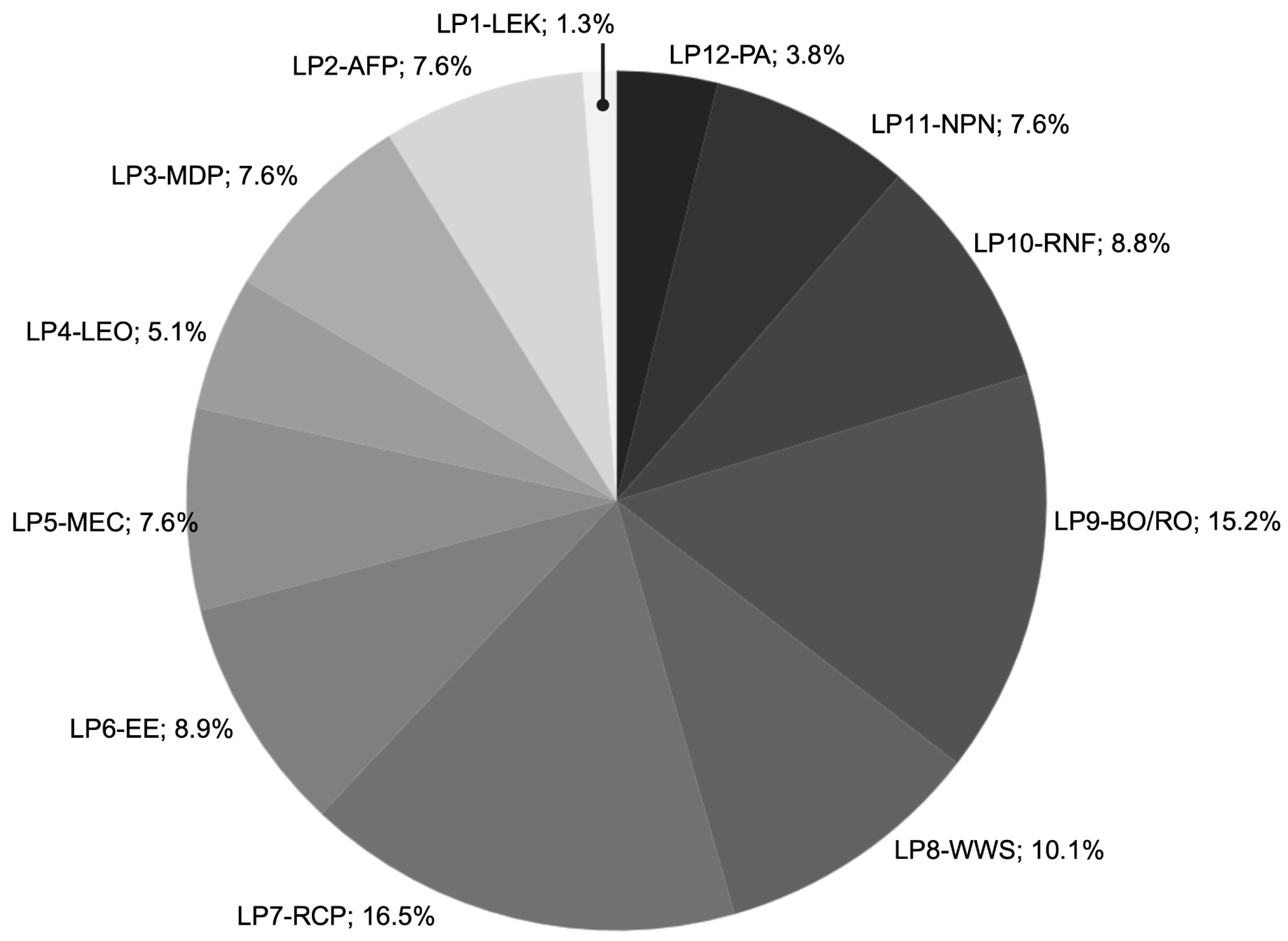

Respondents reported a moderate level of knowledge regarding environmental leverage point actions implemented in the district (mean = 5.9, SD = 2.8; range = 1–12). The most frequently recognized actions were primarily associated with shallower leverage points. Recycling and/or composting processes emerged as the most widely recognized action (n = 13; 16.5%), followed by the municipal beekeeping or recycling ordinance (n = 12; 15.2%). The wildfire early warning system ranked third in terms of recognition (n = 8; 10.1%) (

Figure 4). By contrast, actions linked to the deepest leverage points were substantially less recognized. Integration of local ecological knowledge for environmental management, organic and agroecological farming practices, and the Municipal Development Plan designated as a “Conservation Landscape” (IUCN Category V) were recognized by only 1.3% (n = 1), 7.6% (n = 6), and 7.6% (n = 6) of respondents, respectively.

3.1. Association Between Trust in Agencies and Willingness to Adopt Agricultural Practices

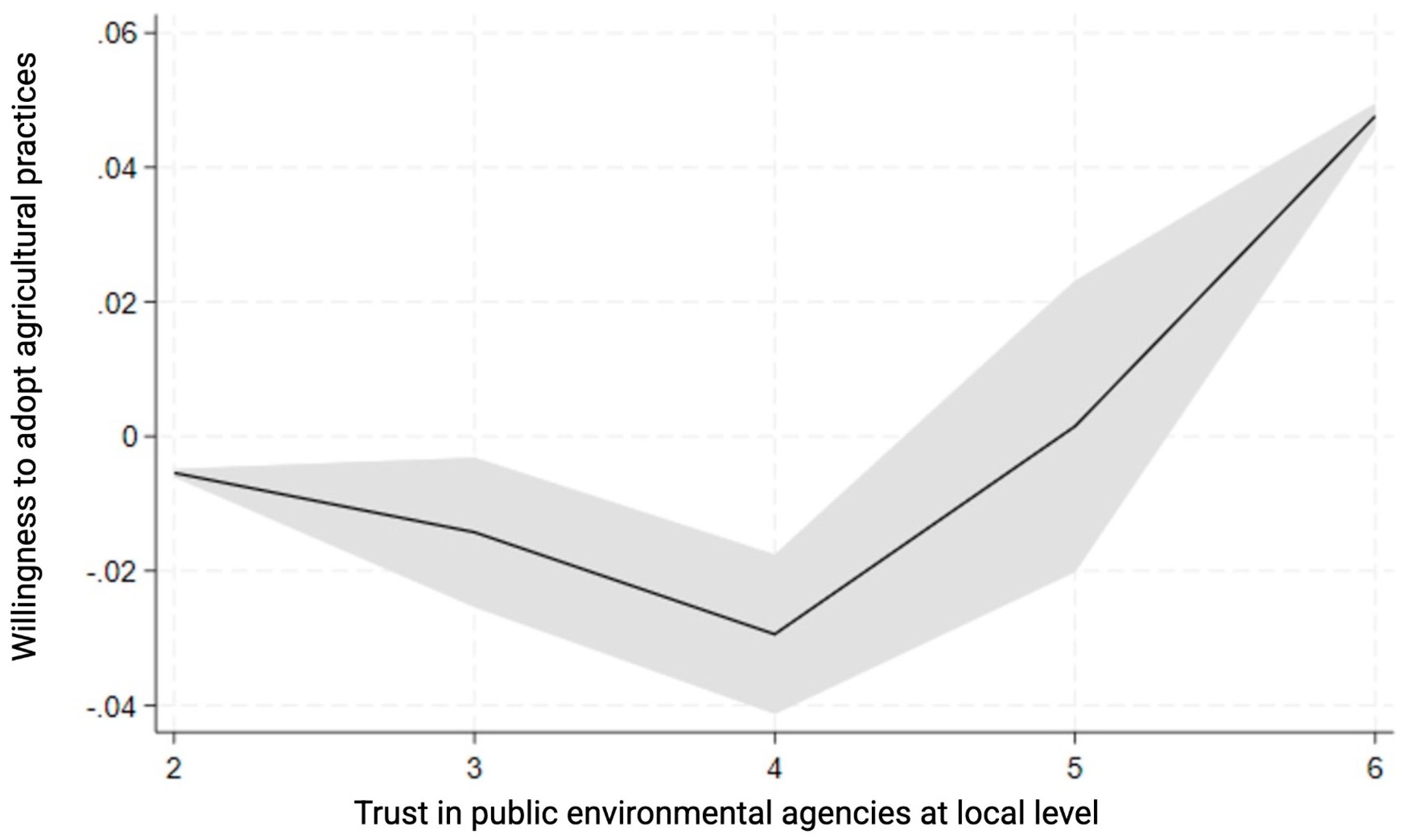

Model selection based on the AIC consistently identified a nonlinear (U-shaped) relationship between trust in environmental agencies and willingness to adopt adaptive practices (Appendix 1). The best adjusted model suggested that the linear term for trust was negative (β = –1.59, SD=0.47, 95% CI= -2.5 - -0.7, p<0.001), whereas the quadratic term was positive (β² = 0.22, SD=0.07, 95% CI= 0.1 - 0.4, p<0.001) (

Table 2;

Figure 5). The turning point occurred at a trust level of approximately 3.6 (on a 1–6 scale). Below this threshold, higher trust was associated with lower willingness, whereas above it, greater trust increased the probability of adopting adaptive practices. Overall, the estimated coefficients were robust, as no variations in sign, magnitude, or significance were observed across the set of candidate models.

The main model also suggested that a higher willingness to adopt adaptive agricultural practices is associated with younger individuals (coef.=-0.84, SD=0.09, 95% CI= -1.1 - 0.7, p<0.001), higher level of knowledge of environmental leverage points (coef.= 0.14, SD=0.02, 95% CI= 0.1 - 0.2, p<0.001), and higher schooling (coef.=0.59, SD=0.27, 95% CI= 0.1 - 1.1, p=0.01) (

Figure 5).

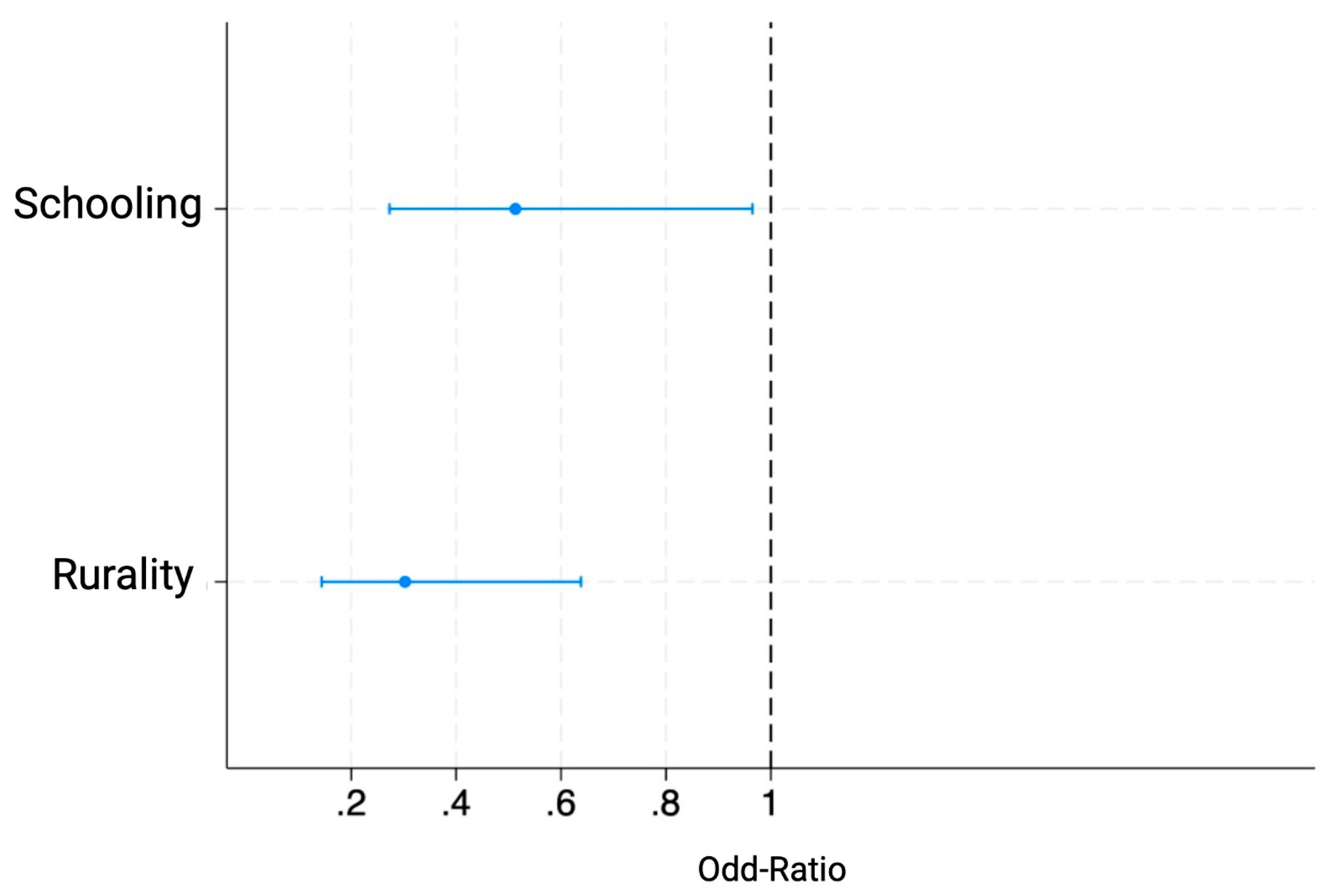

To further characterize the U-shaped pattern, we classified individuals into two groups corresponding to the negative section of the curve (coded as 0; trust index < 3.6) and the positive section (coded as 1; trust index > 3.6), and fitted a series of logistic regression models (Appendix 2). The best-fitting model, based on AICc, showed that individuals in the positive section of the curve had lower schooling (odd ratio = 0.52, SD = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.3 - 0.9, p = 0.03) and were more likely to reside in rural settlements (odd ratio = 0.30, SD = 0.1, 95% CI = 0.1– 0.6, p = 0.002) compared with those in the negative section (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

This study offers new insights into the social–institutional dynamics that underpin farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change. Especially the relationships between farmers and environmental agencies are key since they collaborate and foster informal processes, making these interactions play a key role in adaptive capacity to different contexts or situations. Farmers in Alhué exhibited both a high willingness to adopt adaptive agricultural practices and substantial trust in environmental agencies—two pillars of local resilience. However, the relationship between trust and willingness to adapt was nonlinear, following a U-shaped pattern that reveals trust does not uniformly enhance adaptation. Instead, adaptation behavior appears to depend on differentiated relationships between farmers and institutions, challenging the conventional view that institutional trust straightforwardly promotes adaptive action. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing heterogeneity in social and institutional contexts when designing and implementing climate adaptation policies.

Farmers in Alhué exhibited a generally high willingness to adopt adaptive agricultural practices—an essential dimension of adaptive capacity reflecting readiness to modify management decisions in response to evolving climatic conditions [

43]. This pattern aligns with prior evidence showing that farmers directly experiencing climate-related impacts tend to display stronger adaptive intentions [

8,

9]. Nonetheless, a small subset of respondents expressed skepticism and barriers about both the reality of climate change and the need for adaptive action, a trend consistent with observations in other agricultural contexts [

44]. Such heterogeneity underscores that adaptation decisions are not uniform and emerge from a complex interplay of cognitive, experiential, structural, and institutional factors—including economic constraints, access to technology, policy support, perceived risks, and sociodemographic characteristics [

14,

15,

16].

Within this multifactorial landscape, our findings highlight trust in public environmental agencies as a critical and often overlooked determinant of farmers’ willingness to adapt. Importantly, the trust assessed here refers to trust in the institutions themselves—their credibility, competence, and perceived alignment with farmers' interests—rather than trust in specific adaptation measures. Conceptualized in this way, institutional trust operates as an adaptive resource of its own: it reduces uncertainty, lowers transaction and learning costs, and strengthens expectations that adaptation programs will be effective, accessible, and sustained over time. Our results coincide with previous work that demonstrate how trust in climate-related institutions is central to shaping behavioral responses and the uptake of adaptation measures [

3,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Similarly, studies show that trust in institutional intermediaries mediates farmers’ use of climate information and long-term planning [

22], while institutional credibility more broadly represents a foundation for resilience in agrarian systems [

19].

Importantly, one plausible explanation for these results is that institutional trust among small farmers is ontogenetic, shaped progressively through their historical interactions with public agencies as an outcome of a process of socialization [

3,

18,

22,

23], rather than being a fixed attitudinal trait. Local experiences with extension programs, infrastructure projects, subsidies, training activities, and regulatory processes shape farmers’ expectations regarding institutional reliability and fairness [

3,

14]. In fact, our results also suggest that education appears to be a key factor to trust in public environmental agencies. Positive experiences—such as timely delivery of resources, transparent communication, or visible program success—tend to reinforce trust, whereas experiences perceived as ineffective, inequitable, or poorly managed erode it. Our results reinforce the notion that farmers’ experiential pathways may play a central role in shaping institutional trust, which in turn conditions farmers’ willingness to engage in climate adaptation initiatives.

Taken together, our findings reinforce that institutional trust—shaped by both personal and collective histories of interaction—constitutes a cornerstone of adaptive capacity. Strengthening institutional credibility and legitimacy may therefore be as essential as expanding access to technologies or financial incentives. This calls for adaptation programs that not only deliver technical solutions but also cultivate sustained, transparent, and responsive relationships with rural communities [

3,

18]. Such an approach would better align with an emerging understanding of adaptation as a socio-institutional process, where trust, history, and local experience are as consequential as biophysical and economic factors.

The influence of trust may appear intuitive but unclear, while our findings reveal that farmers’ willingness to adopt adaptive practices to climate change is high and strongly shaped by their trust in public environmental agencies. This relationship follows a U-shaped pattern, indicating that willingness to adapt initially decreases as trust increases, but rises again at higher trust levels. This nonlinear association reflects the existence of distinct farmer profiles in their interactions with environmental agencies, each displaying different pathways toward adaptation. These insights advance our understanding of how trust dynamics condition adaptive behavior in agriculture, highlighting the central role of institutional relationships in fostering climate resilience.

Our results suggest that the influence of institutional trust on the willingness to adopt agricultural practices is mediated by farmers’ education levels and their type of settlement. These patterns likely reflect structural differences in how individuals’ dispositions are formed. Specifically, they may be linked to the socialization processes through which people acquire political and social beliefs, values, and attitudes that shape trust, closely intertwined with the characteristics of their community and territorial contexts—dimensions captured in our variables for education and settlement type [

3,

23,

41,

45]. For instance, farmers with higher levels of schooling may be more responsive to external signals such as institutional performance, given the central role of schools as socializing agents in the development of individual trust [

3,

23]. Moreover, higher education is generally associated with a better understanding of complex climate-related phenomena, mitigation measures, and knowledge about their effectiveness. This, in turn, may lead to higher expectations regarding how public agencies should address climate change adaptation strategies [

3,

14].

Moreover, ontogenetic factors shaping the relationship between willingness to adapt and trust may also be socially transmitted. These dynamics are partially captured by settlement type, acknowledging that rural and urban areas undergo different socialization processes with environmental institutions. Farmers’ trust judgments are formed not only through direct interactions with agencies but also through shared narratives and collective memories embedded in local communities and producer networks. As highlighted in research on social learning and the diffusion of adaptation behaviors [

3,

5,

14], trust perceptions can spread through peer influence, shaping community-level expectations regarding institutional performance. Consequently, the historical performance of public agencies within a given territory may generate positive or negative trust spillovers, amplifying or dampening farmers’ willingness to adopt adaptive strategies beyond the effects of individual experiences alone.

If the observed relationship between trust and willingness to adapt is consistent across other contexts and adaptation practices, it carries significant implications for both science and environmental policy. First, the nonlinear pattern identified here suggests that adaptation strategies should move beyond the assumption of homogeneous farmer groups and instead recognize distinct profiles that differ in their relationships with public agencies. Current adaptation policies—typically designed at central levels and downscaled to local territories—often presume a uniform willingness to adopt among smallholders. While such an assumption may facilitate resource allocation, it risks overlooking important heterogeneities. Our findings indicate that farmers with low levels of trust in public agencies are less likely to adopt adaptive practices, whereas those with high trust are more inclined to do so. Engaging low-trust farmers may therefore require greater investment and more context-specific approaches to effectively foster participation in climate adaptation programs.

Second, adaptive programs that assume homogeneous farmer groups may unintentionally exacerbate socially and environmentally maladaptive outcomes. Without prior efforts to address variations in trust, farmers with low institutional trust may be less able to sustain their livelihoods through agriculture, thereby increasing their vulnerability to climate change. Moreover, life-course and experiential factors shaping farmers’ relationships with institutions may condition their responses to adaptive strategies—elements that should be explicitly incorporated into the design and implementation of adaptation policies. Third, the nonlinear relationship between trust and willingness to adapt also carries important implications for territorial management modeling and for the economic valuation of adaptive efforts in cost–benefit analyses. Current program designs often assume a uniform behavioral response among farmers, regardless of differences in institutional trust. However, if some farmers are less willing to adopt adaptive measures due to lower trust, such models may overestimate benefits and underestimate costs—a distortion that could be particularly consequential in vulnerable and low-income rural territories.

The case of Alhué in Chile illustrates how these mechanisms operate in highly vulnerable territories, offering lessons that may inform adaptation strategies in similar regions worldwide. However, understanding whether the observed relationships between trust and willingness to adapt—and their associated policy implications—hold across other contexts within Chile and beyond requires close collaboration between scientists and practitioners. Such collaboration is essential to address a persistent blind spot in understanding the social determinants of adaptation to climate change. Advancing this knowledge demands analytical frameworks that integrate downscaling and territorial integration, thereby linking local adaptive dynamics with higher-level governance processes. Local-level assessments, complemented by cross-scale comparisons, are necessary to capture the contextual complexities that shape farmers’ adaptive behavior. Our findings contribute to this effort by illuminating how social, cultural, political, and economic factors condition management outcomes, inform the legitimacy and acceptability of governance arrangements, and ultimately help ensure that management interventions are both culturally appropriate and socially equitable [

22].

Developing robust, context-specific evidence on adaptation practices at multiple scales enables researchers, policymakers, and communities to better align strategies and maximize the effectiveness of investments in climate adaptation. Local empirical findings such as ours should therefore be integrated into multi-level governance that guide social–ecological systems toward desired trajectories. In this sense, our study contributes to bridging upscaling and downscaling perspectives, helping to elucidate and overcome the barriers that constrain the implementation of adaptive management across contexts and scales.

Author Contributions

N.T.T, J.L.L., C.G., C.L., L.F.F, J.A.S., and F.Z.R.; methodology, N.T.T., L.M., M.R., A.B., J.C.A., C.A., and F.Z.R.; data collection, N.T.T., L.M., M.R., A.B., J.C.A., and F.Z.R; formal analysis, N.T.T., L.M. and F.Z.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T.T and F.Z.R.; writing—review and editing, N.T.T, L.M., M.R., A.B., J.C.A., C.A., J.L.L., C.G., C.L., L.F.F, J.A.S., and F.Z.R.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Study site: District of Alhué, Metropolitan Region, Chile. The figure shows the location of the local settlements surveyed in this study.

Figure 1.

Study site: District of Alhué, Metropolitan Region, Chile. The figure shows the location of the local settlements surveyed in this study.

Figure 2.

Willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices among small farmers in Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure presents the median willingness scores for five agricultural practices commonly associated with climate change adaptation—crop rotation (CR), mixed cropping (MC), application of organic fertilizers or compost (OF/C), rainwater harvesting (RWH), and incorporation of crop residues or stubble (CR/S)—as well as the mean value of the overall willingness index across respondents. Willingness was measured on a six-point ordinal scale (1 = Totally unwilling, 2 = Unwilling, 3 = Somewhat unwilling, 4 = Somewhat willing, 5 = Willing, 6 = Totally willing). All five practices loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.95) and exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Figure 2.

Willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices among small farmers in Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure presents the median willingness scores for five agricultural practices commonly associated with climate change adaptation—crop rotation (CR), mixed cropping (MC), application of organic fertilizers or compost (OF/C), rainwater harvesting (RWH), and incorporation of crop residues or stubble (CR/S)—as well as the mean value of the overall willingness index across respondents. Willingness was measured on a six-point ordinal scale (1 = Totally unwilling, 2 = Unwilling, 3 = Somewhat unwilling, 4 = Somewhat willing, 5 = Willing, 6 = Totally willing). All five practices loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.95) and exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Figure 3.

Trust in environmental agencies among small farmers in Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure displays the median trust scores for four public environmental agencies—Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario (INDAP), Programa de Desarrollo Local (PRODESAL), Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF), and Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG)—as well as the mean value of the overall trust index across respondents. Trust was measured on a six-point ordinal scale: (1 = No trust at all, 2 = Low trust, 3 = Somewhat low trust, 4 = Somewhat high trust, 5 = High trust, 6 = Complete trust).. Trust in the four agencies loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.3) and showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.74).

Figure 3.

Trust in environmental agencies among small farmers in Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure displays the median trust scores for four public environmental agencies—Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario (INDAP), Programa de Desarrollo Local (PRODESAL), Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF), and Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG)—as well as the mean value of the overall trust index across respondents. Trust was measured on a six-point ordinal scale: (1 = No trust at all, 2 = Low trust, 3 = Somewhat low trust, 4 = Somewhat high trust, 5 = High trust, 6 = Complete trust).. Trust in the four agencies loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.3) and showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.74).

Figure 4.

Actions associated with environmental governance leverage points recognized by residents of Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported being aware of each action associated with specific environmental governance leverage points. Leverage points (LP) are ordered from deeper to shallower levels of intervention. The actions included are: LP1 – Integration of Local Ecological Knowledge for environmental management (LP1-LEK); LP2 – Organic and Agroecological Farming Practices (LP2-AFP); LP3 – Municipal Development Plan, “Conservation Landscape” IUCN Type V (LP3-MDP); LP4 – Local Environmental Organizations (LP4-LEO); LP5 – Municipal Environmental Committee (LP5-MEC); LP6 – Environmental Education (LP6-EE); LP7 – Recycling and/or Composting Processes (LP7-RCP); LP8 – Wildfire Early Warning System (LP8-WWS); LP9 – Municipal Beekeeping Ordinance or Recycling Ordinance (LP9-BO/RO); LP10 – Reforestation of Native Forest (LP10-RNF); LP11 – Native Plant Nursery (LP11-NPN); and LP12 – Protected Areas (LP12-PA).

Figure 4.

Actions associated with environmental governance leverage points recognized by residents of Alhué, Chile (n=79). The figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported being aware of each action associated with specific environmental governance leverage points. Leverage points (LP) are ordered from deeper to shallower levels of intervention. The actions included are: LP1 – Integration of Local Ecological Knowledge for environmental management (LP1-LEK); LP2 – Organic and Agroecological Farming Practices (LP2-AFP); LP3 – Municipal Development Plan, “Conservation Landscape” IUCN Type V (LP3-MDP); LP4 – Local Environmental Organizations (LP4-LEO); LP5 – Municipal Environmental Committee (LP5-MEC); LP6 – Environmental Education (LP6-EE); LP7 – Recycling and/or Composting Processes (LP7-RCP); LP8 – Wildfire Early Warning System (LP8-WWS); LP9 – Municipal Beekeeping Ordinance or Recycling Ordinance (LP9-BO/RO); LP10 – Reforestation of Native Forest (LP10-RNF); LP11 – Native Plant Nursery (LP11-NPN); and LP12 – Protected Areas (LP12-PA).

Figure 5.

Association between trust in public environmental agencies and willingness to adopt agricultural practices for climate change adaptation among small farmers in Alhué, Chile.

Figure 5.

Association between trust in public environmental agencies and willingness to adopt agricultural practices for climate change adaptation among small farmers in Alhué, Chile.

Figure 6.

Odds ratios comparing farmers on the negative vs. positive slope of the U-shaped trust–willingness association.

Figure 6.

Odds ratios comparing farmers on the negative vs. positive slope of the U-shaped trust–willingness association.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the models.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the models.

| Variables |

Definition |

Median

(min-max)

|

Mean

(Std. Dev.)

|

| I.: Outcome variable |

|

|

|

| Willingness to adopt climate change adaptation practices |

Willingness to adopt agricultural practices for climate change adaptation, measured on a 6-point scale (1 = no willingness, 6 = complete willingness), based on farmers’ responses regarding the adoption of specific agricultural practices. |

5

(2-6) |

4.9

(0.9) |

| I. Explanatory variables: |

|

|

|

| Trust in public environmental agencies |

Trust in public environmental agencies, measured on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all trustworthy to 6 = extremely trustworthy. |

5

(1-6) |

4.3

(1.2) |

| II. Control variables |

|

|

|

| Age |

Age group, classified into four categories: 1 = youth (15–29 years), 2 = young adults (30–44 years), 3 = middle-aged adults (45–64 years), and 4 = older adults (65 years and above |

3

(1-4) |

3.1

(0.9) |

| Income |

Economic income, measured using a closed-ended question with the following categories: 1 = less than $300,000; 2 = $301,000–$500,000; 3 = $501,000–$800,000; 4 = $801,000–$1,200,000; 5 = $1,200,001–$2,000,000; 6 = $2,000,001–$3,000,000; 7 = more than $3,000,000. |

3

(1-7) |

2.9

(1.5) |

| Gender |

Sex of respondent. 1=Female, 0=male |

43% |

|

| Knowledge of environmental governance leverage points |

Knowledge of key elements in governance systems (policies, areas of citizen participation, and strategic locations in the area), based on dichotomous responses of 'know' (yes = 1) and 'do not know' (no = 0). |

6 (1-12) |

6

(2.9) |

| Perception of climate change impacts |

Perception of local climate change impacts, assessed using perceived changes in native vegetation, crops and agricultural activity, abundance of fauna (including birds and native animals), and insect abundance as proxies. Responses for each proxy were recorded on a six-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 = “Totally decreased” to 6 = “Totally increased”. |

3 (1-5) |

3.1 (0.9) |

| Rurality |

Type of settlement of residence, coded as 1 = rural (Pincha, Las Juntas, La Línea, Barrancas de Pichi, El Asiento, and Talamí) and 0 = urban (Hijuelas de Poluto, Villa Alhué, and Ignacio Carrera Pinto). |

53% |

|

| Schooling |

Education level, classified into four categories: 0 = no formal education, 1 = primary education, 2 = secondary education, and 3 = higher or university education. |

2

(1-3)

|

1.8

(0.8) |

Table 2.

Association between trust in public environmental agencies and willingness to adopt agricultural practices for climate change adaptation among small farmers in Alhué, Chile. The table reports coefficients, standard errors (in parentheses), and 95% confidence intervals from ordered logistic regressions for the best-fitting model based on the Akaike Information Criterion (see Appendix 1 for the full set of models). Definitions and descriptive statistics are provided in

Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.1, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

Table 2.

Association between trust in public environmental agencies and willingness to adopt agricultural practices for climate change adaptation among small farmers in Alhué, Chile. The table reports coefficients, standard errors (in parentheses), and 95% confidence intervals from ordered logistic regressions for the best-fitting model based on the Akaike Information Criterion (see Appendix 1 for the full set of models). Definitions and descriptive statistics are provided in

Table 1. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.1, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

| Variables |

|

Coefficient |

95% Conf. Interval |

| |

|

(Standard error) |

Min |

Max |

| I. Explanatory variables: |

|

|

|

|

| Trust in public environmental agencies |

[a] |

-1.59 (0.47)*** |

-2.52 |

-0.67 |

| Square of Trust in public environmental agencies |

[b] |

0.22 (0.066)*** |

0.09 |

0.35 |

II. Control variables |

|

|

|

|

| Age |

[c] |

-0.84 (0.09)*** |

-1.05 |

-0.65 |

| Income |

[d] |

-0.43(0.26) |

-0.96 |

0.08 |

| Knowledge of environmental governance leverage points |

[f] |

0.14 (0.02)*** |

0.108 |

0.19 |

| Schooling |

[h] |

0.59(0.27)** |

0.05 |

1.13 |