Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

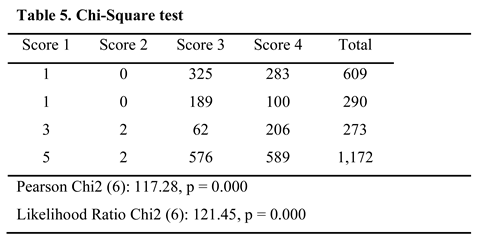

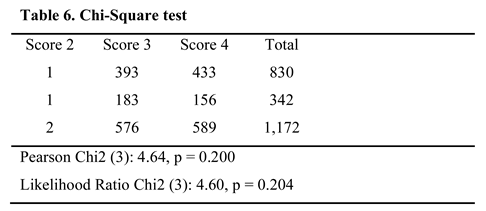

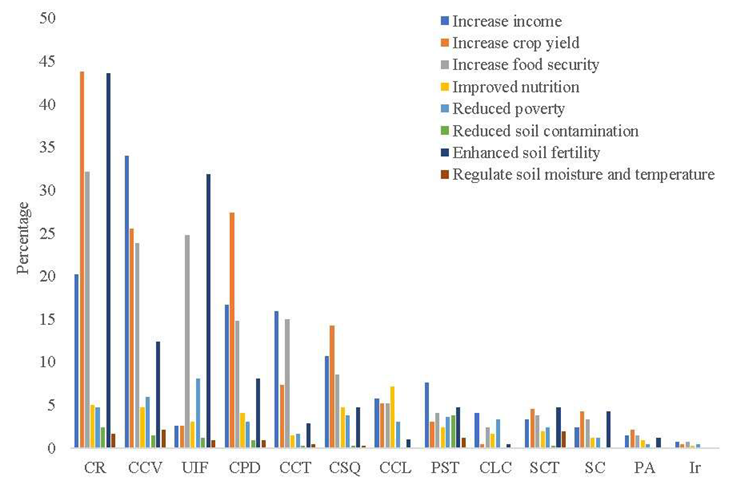

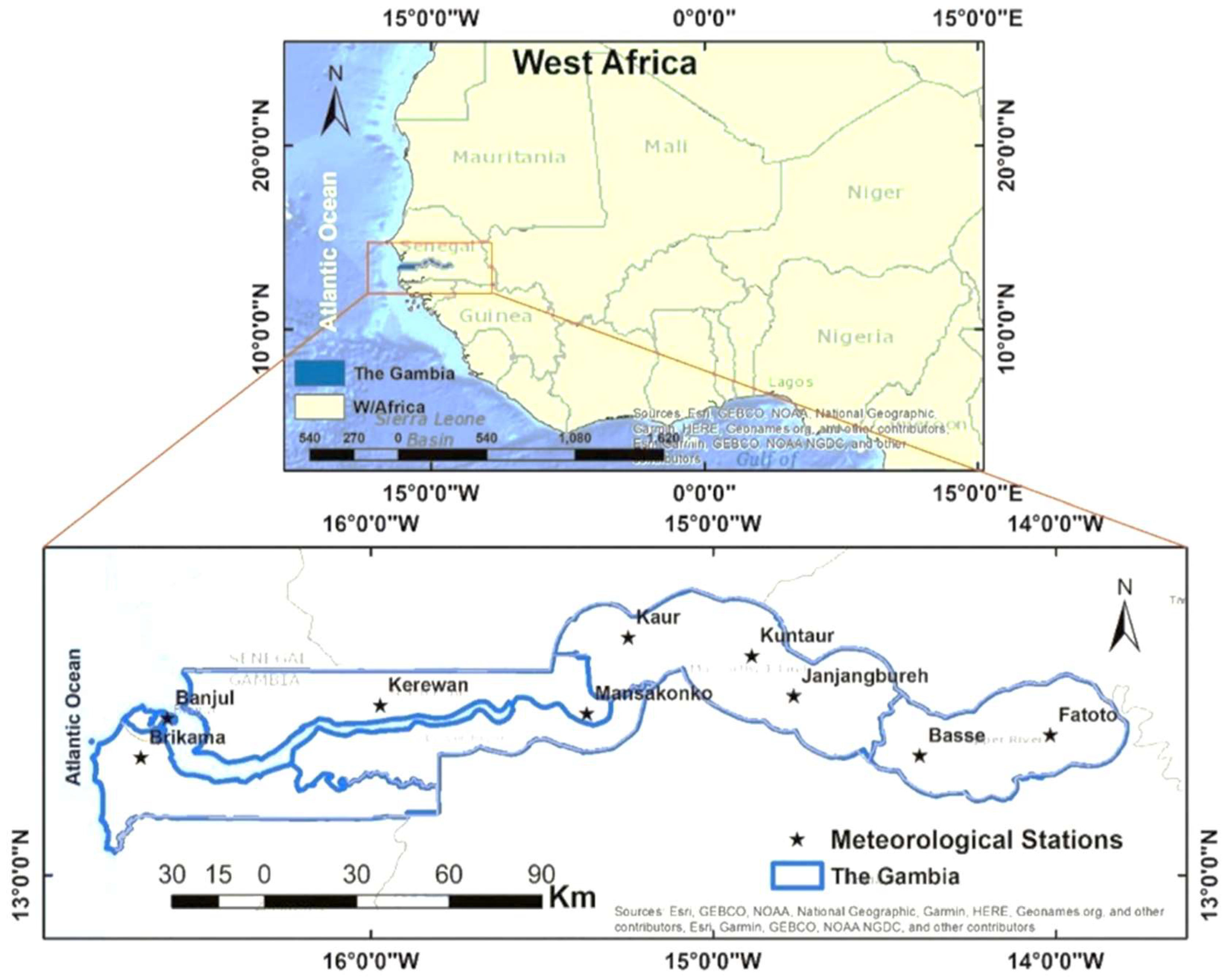

Agricultural systems face increasing challenges due to climate change, necessitating effective adaptation and mitigation strategies. This study investigates smallholder farmers' perceptions of the efficacy of these strategies in The Gambia, employing a mixed-method approach that includes a Perception Index (PI), Effectiveness Score (ES), Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) and statistical analysis. A structured survey was conducted among 420 smallholder farmers across three agricultural regions. Farmers rated adaptation and mitigation strategies using a Likert scale, and a PI was developed to quantify their responses. The index was 0.66, indicating a moderate level of perceived effectiveness. Additionally, ES was calculated to assess the performance of various strategies, while IPA categorized strategies based on their adoption and perceived impact. Chi-square tests and factor analysis were applied to explore differences in perceptions. Findings reveal that strategies such as crop diversification, pesticide application, irrigation, and use of inorganic fertilizers are widely adopted and perceived as effective. The IPA matrix identified key strategies needing improvement, particularly those with high importance but low performance. Barriers to adoption include limited financial resources (77%), lack of government support (64%), and insufficient knowledge (52%), with no significant gender-based differences in perceptions. The study underscores the need for policy interventions that integrate farmers' perceptions to enhance climate resilience. Targeted investments in adaptive technologies, financial support, and knowledge-sharing platforms can improve adoption and effectiveness. This research provides valuable insights into the interplay between farmer perceptions, adaptation strategies, and agricultural sustainability in The Gambia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Effectiveness Score (ES)

2.3.2. Perception Index (PI)

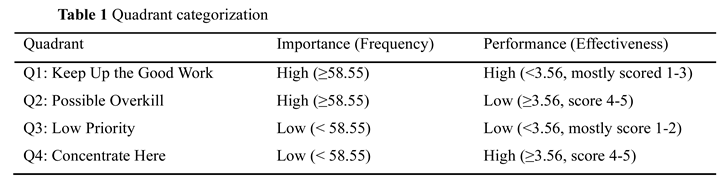

2.3.3. Importance Performance Analysis (IPA)

3. Results

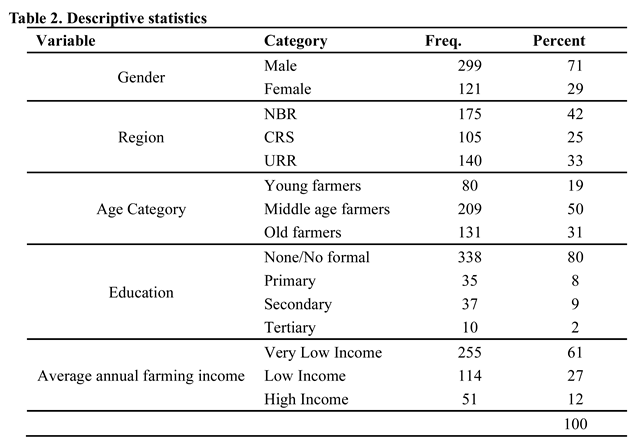

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

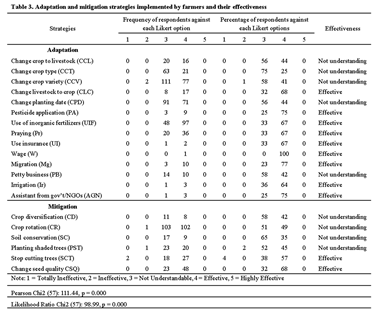

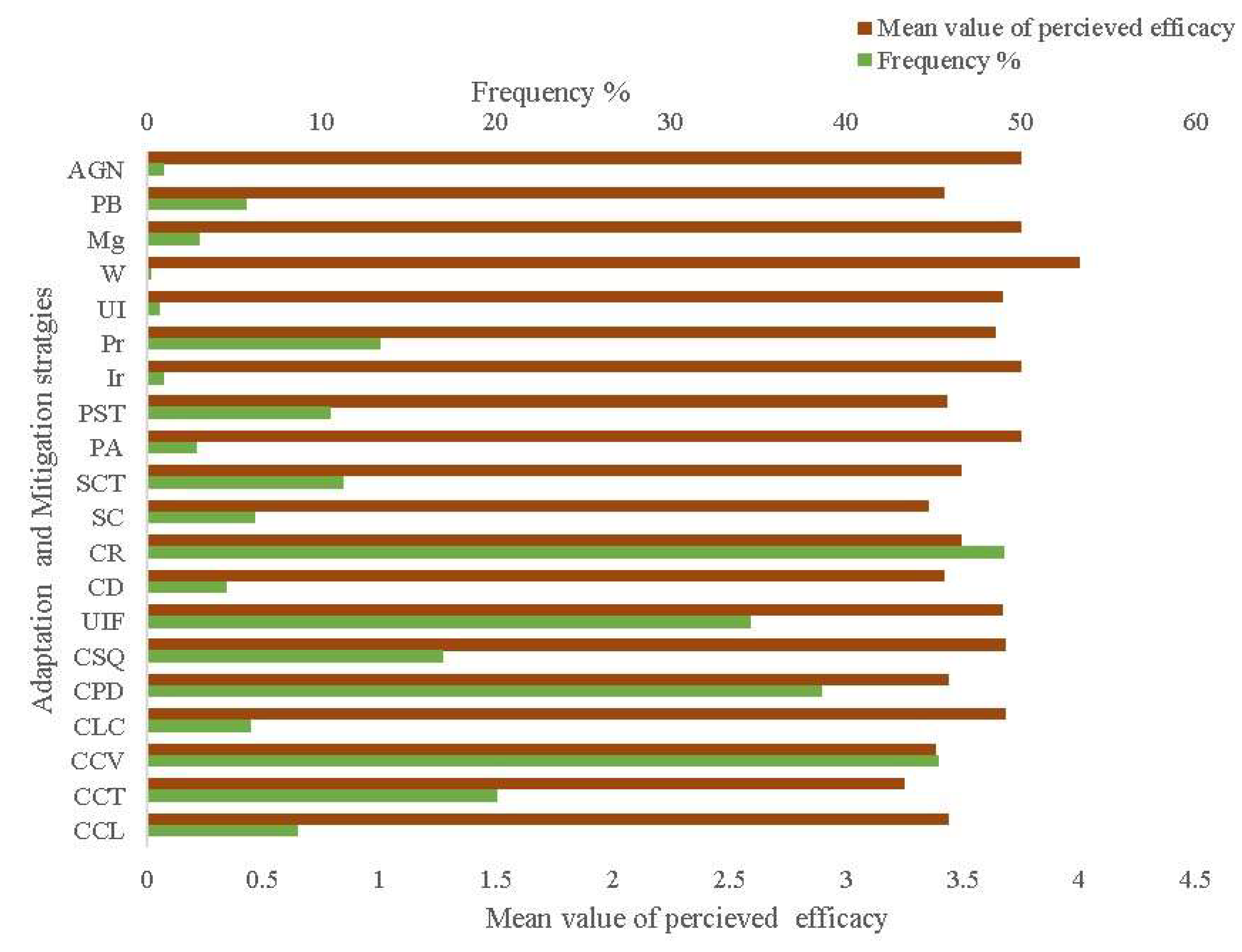

3.2. Farmers’ Perceptions of Different Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies

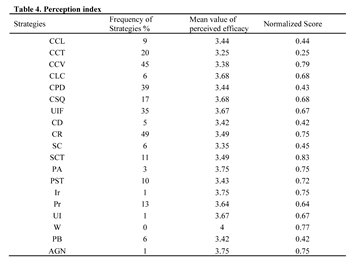

3.3. Analysis of the Perception Index

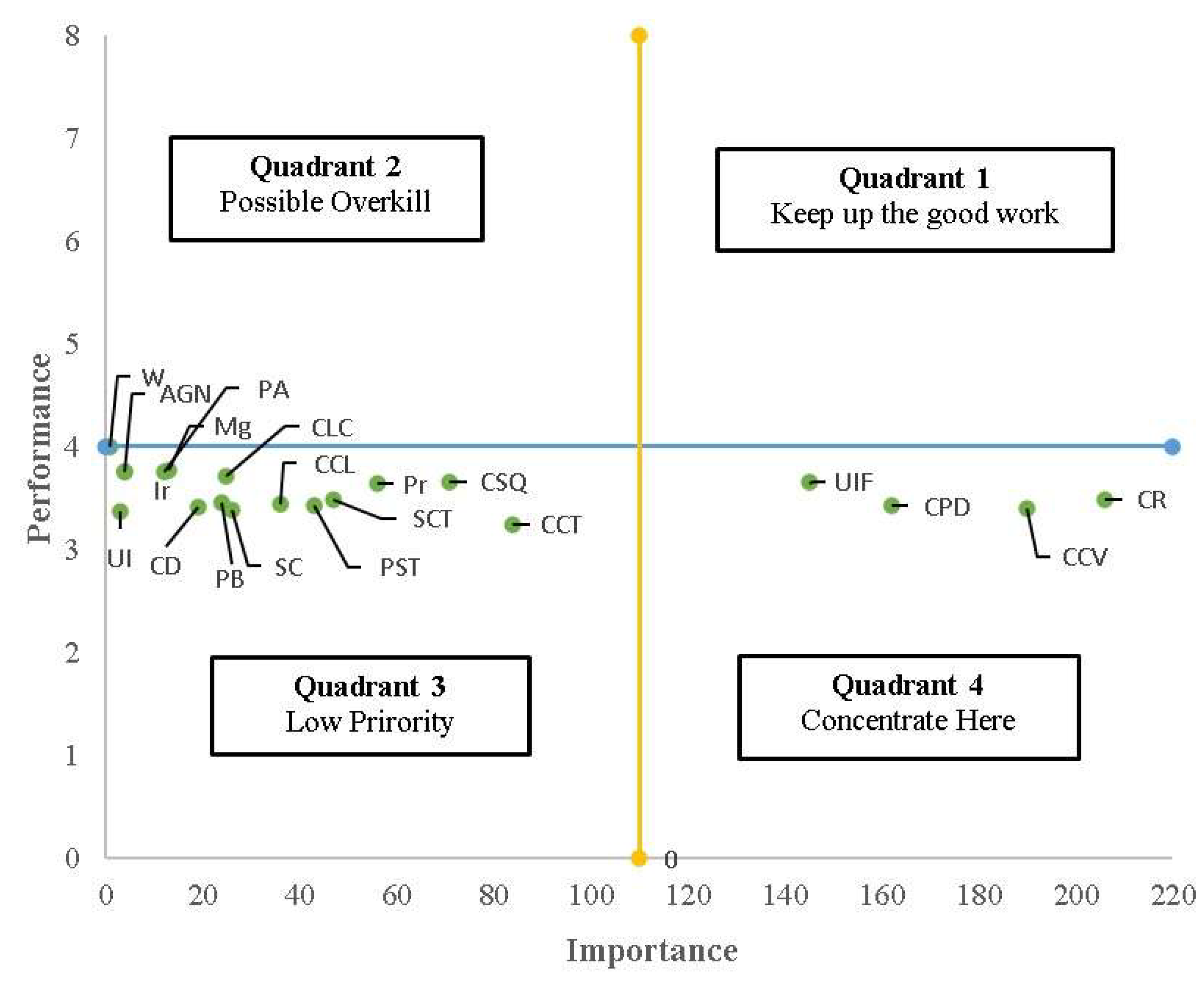

3.4. Importance Performance Analysis Matrix

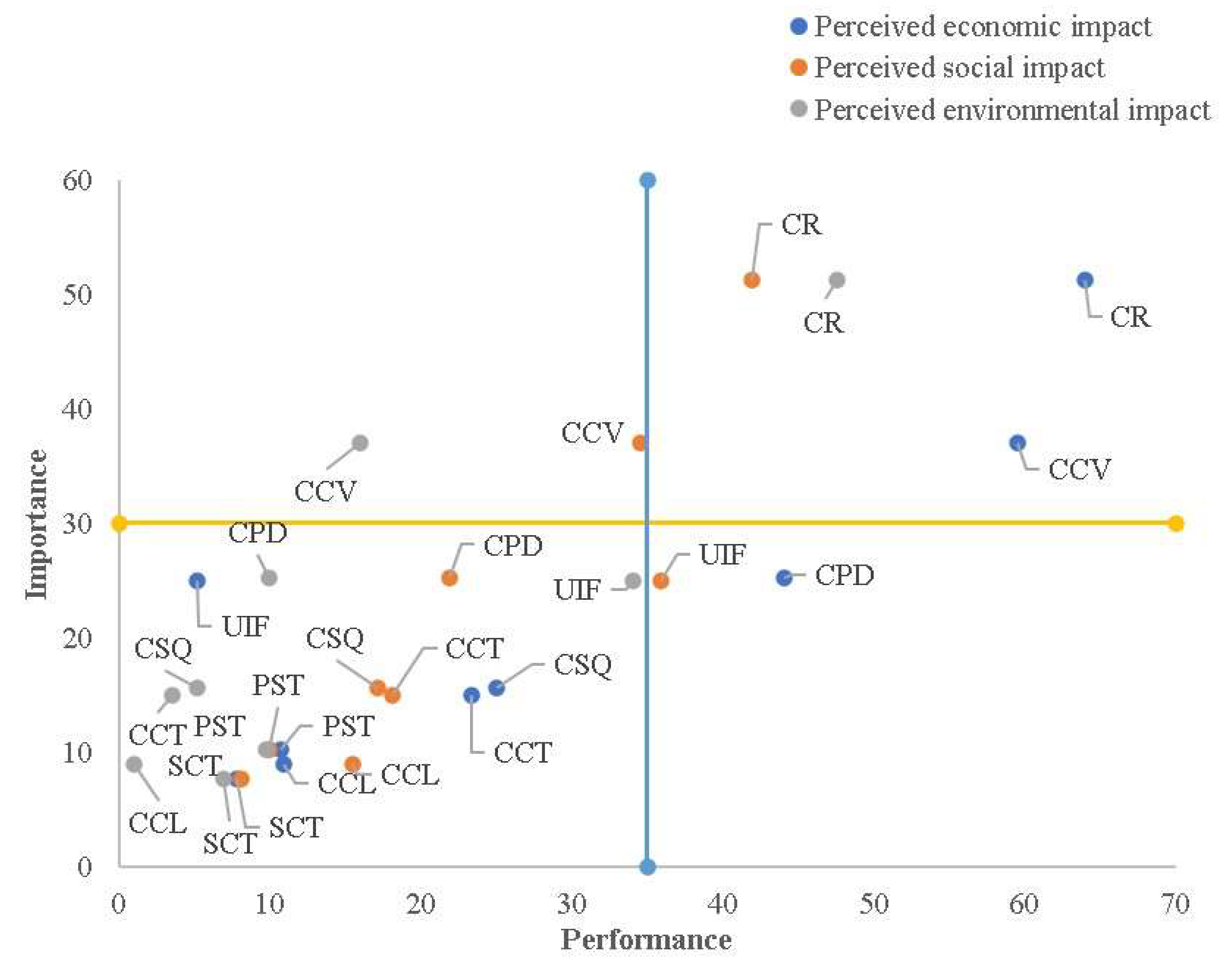

3.5. Perceived Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes of These Strategies

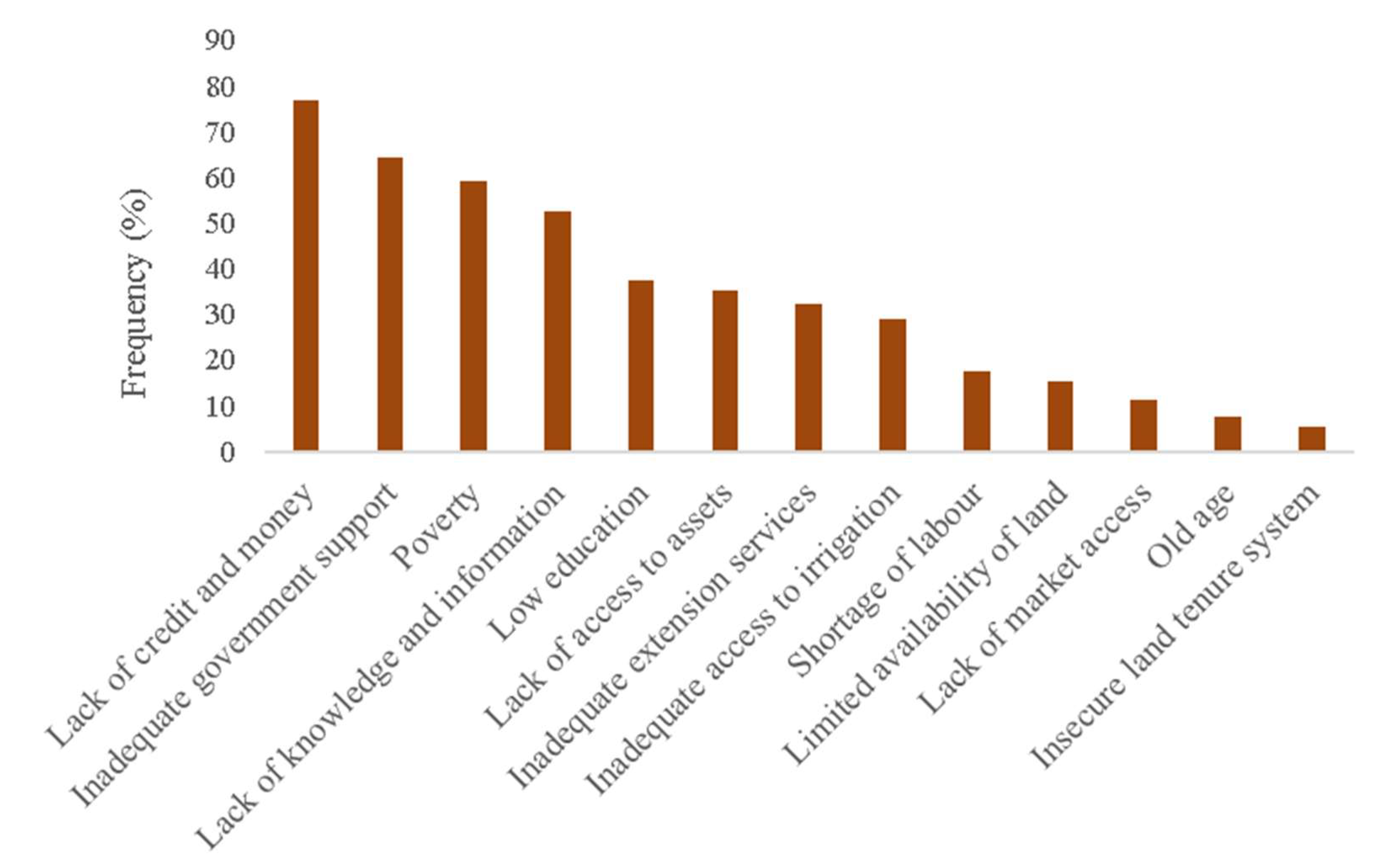

3.6. Challenges of Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Code Availability

Ethic Approval

Informed Consent

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGN | Assistant from government /NGOs |

| CCL | Change crop to livestock |

| CCT | Change crop type |

| CCV | Change crop variety |

| CD | Crop diversification |

| CLC | Change livestock to crop |

| CPD | Change planting date |

| CR | Crop rotation |

| CSQ | Change seed quality |

| IPA | Importance Performance Analysis |

| Ir | Irrigation |

| Mg | Migration |

| NS | Normalized Score |

| PA | Pesticide application |

| PB | Petty business |

| PE | Percentage of effective |

| PHE | Percentage of highly effective |

| PHI | Percentage of highly ineffective |

| PI | Percentage of ineffective |

| PI | Perception Index |

| PNU | Percentage of not understanding |

| Pr | Praying |

| PST | Planting shaded trees |

| SC | Soil conservation |

| SCT | Stop cutting trees |

| UI | Use Insurance |

| UIF | Use of inorganic fertilizers |

| W | Wage |

References

- F. Lambarraa-Lehnhardt, S. F. Lambarraa-Lehnhardt, S. Ceesay, M. B. O. Ndiaye, D. Thiaw, and M. Sawaneh, “Climate risk perception and adaptation strategies of smallholder farmers in The Gambia,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 506, Dec. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Abbass, M. Z. K. Abbass, M. Z. Qasim, H. Song, M. Murshed, H. Mahmood, and I. Younis, “A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures,” Jun. 01, 2022, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Verma et al., “Climate change adaptation: Challenges for agricultural sustainability,” 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- P. Kopeć, “Climate Change—The Rise of Climate-Resilient Crops,” Feb. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- R. Akhtar and M. M. Masud, “Dynamic linkages between climatic variables and agriculture production in Malaysia: a generalized method of moments approach,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 29, no. 27, pp. 41557–41566, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation in the food and agriculture sector. technical background document from the expert consultation, held on 5 to 7 March 2008 FAO, Rome.

- T. Sinore and F. Wang, “Impact of climate change on agriculture and adaptation strategies in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis,” Feb. 29, 2024, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- A. Braimoh, C. A. Braimoh, C. Roncoli, and A. C. Segnon, “Climate change adaptation options to inform the planning of agriculture and food systems in The Gambia: A systematic approach for stocktaking.” [Online]. Available: https://era.ccafs.cgiar.

- B. Bayo and S. Mahmood, “Geo-spatial analysis of drought in The Gambia using multiple models,” Natural Hazards, vol. 117, no. 3, pp. 2751–2770, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Amuzu, B. P. J. Amuzu, B. P. Jallow, A. T. Kabo-Bah, and S. Yaffa, “The climate change vulnerability and risk management matrix for the coastal zone of The Gambia,” Hydrology, vol. 5, no. 1, Mar. 2018). [CrossRef]

- E. S. Sanneh, A. H. E. S. Sanneh, A. H. Hu, C. W. Hsu, and M. Njie, “Prioritization of climate change adaptation approaches in the Gambia,” Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 1163–1178, Nov. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. W. Carr et al., “Addressing future food demand in The Gambia: an increased crop productivity and climate change adaptation close the supply-demand gap?,” Food Secur, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 691–704, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Belford, D. Huang, Y. N. Ahmed, E. Ceesay, and L. Sanyang, “An economic assessment of the impact of climate change on the Gambia’s agriculture sector: a CGE approach. Int J Clim Chang Strateg Manag, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Sanneh, A. H. E. S. Sanneh, A. H. Hu, C. W. Hsu, and M. Njie, “Prioritization of climate change adaptation approaches in the Gambia,” Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 1163–1178, Nov. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Berrang-Ford et al., “Tracking global climate change adaptation among governments,” Jun. 01, 2019, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- C. Singh et al., “Interrogating ‘effectiveness’ in climate change adaptation: 11 guiding principles for adaptation research and practice,” 2022, Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- R. Roy et al., “Determining synergies and trade-offs between adaptation, mitigation and development in coastal socio-ecological systems in Bangladesh,” Environ Dev, vol. 48, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5°C,” Sep. 20, 2019, American Association for the Advancement of Science. [CrossRef]

- N. P. Simpson et al., “Adaptation to compound climate risks: A systematic global stocktake,” iScience, vol. 26, no. 2, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Camara et al., “Impact of land tenure on deforestation control and forest restoration in Brazilian Amazonia,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 18, no. 6, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. De Gregorio et al., “Climate change opportunities reduce farmers’ risk perception: Extension of the value-belief-norm theory in the context of Finnish agriculture. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Ikehi, F. O. M. E. Ikehi, F. O. Ifeanyieze, F. M. Onu, T. E. Ejiofor, and C. U. Nwankwo, “Assessing climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies and agricultural innovation systems in the Niger Delta,” GeoJournal, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 209–224, Feb. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. W. Carr et al., “Climate change impacts and adaptation strategies for crops in West Africa: A systematic review,” 2022, Institute of Physics. [CrossRef]

- L. Berrang-Ford et al., “Tracking global climate change adaptation among governments,” Jun. 01, 2019, Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- “Preliminary Report THE GAMBIA 2024 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS (2024).” https://www.gbosdata.

- “The Gambia Bureau of Statistics 2023.

- Ali Bah, “Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics in Central River Region of the Gambia, West Africa from 1984 to 2017,” American Journal of Modern Energy, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 2019; 5. [CrossRef]

- F. Lambarraa-Lehnhardt, S. F. Lambarraa-Lehnhardt, S. Uthes, P. Zander, and A. Benhammou, “How improving the technical efficiency of Moroccan saffron farms can contribute to sustainable agriculture in the Anti-Atlas region,” Studies in Agricultural Economics, vol. 124, no. 3, pp. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. Islam, M. Z. M. S. Islam, M. Z. Hossain, and M. B. Sikder, “Drought adaptation measures and their effectiveness at Barind Tract in northwest Bangladesh: a perception study,” Natural Hazards, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 1253–1276, Jul. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. A. Martilla and J. C. James, “Importance-Performance Analysis,” 1977. The Journal of Marketing. [CrossRef]

- E. Azzopardi and R. Nash, “A critical evaluation of importance-performance analysis,”. Tour Manag, 2013; 35, 222–233. [CrossRef]

- A. Sörensson and Y. von Friedrichs, “An importance-performance analysis of sustainable tourism: A comparison between international and national tourists,” Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 2013; 21. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Warner, A. L. A. Warner, A. Kumar, and A. J. Lamm, “Using importance-performance analysis to guide extension needs assessment,” J Ext, vol. 54, no. 2016; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. R. Bacon, “A comparison of approaches to Importance-Performance Analysis,” 2003.

- A. R. Bagagnan, I. A. R. Bagagnan, I. Ouedraogo, and W. M. Fonta, “Perceived climate variability and farm level adaptation in the Central River Region of The Gambia,” Atmosphere (Basel), vol. 10, no. 7, Jul. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Charles Boliko, “FAO and the Situation of Food Security and Nutrition in the World,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Braimoh, C. A. Braimoh, C. Roncoli, and A. C. Segnon, “Climate change adaptation options to inform planning of agriculture and food systems in The Gambia: A systematic approach for stocktaking.” [Online]. Available: https://era.ccafs.cgiar.

- R. H. Taplin, “Competitive importance-performance analysis of an Australian wildlife park,” Tour Manag, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 2012; 33, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Wong, N. M. S. Wong, N. Hideki, and P. George, “The use of importance-performance analysis (IPA) in evaluating Japan’s e-government services,” 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Shieh and H. H. Wu, “Applying importance-performance analysis to compare the changes of a convenient store,” Qual Quant, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 20 May; 09. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Hosseini and A. Ziaei Bideh, “A data mining approach for segmentation-based importance-performance analysis (SOM-BPNN-IPA): A new framework for developing customer retention strategies,” Service Business, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 295–312, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Phadermrod, R. M. B. Phadermrod, R. M. Crowder, and G. B. Wills, “Importance-Performance Analysis based SWOT analysis.” International journal of information management, 44, 194-203. [CrossRef]

- B. I. Kanyangale and C. H. Lee, “Integrating Locals’ Importance-Performance Perception of Adaptation Behaviour into Invasive Alien Plant Species Management Surrounding Nyika National Park, Malawi,” Forests, vol. 14, no. 9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Rohit et al., “Exploring farmers’ communication pattern and satisfaction regarding the adoption of Agromet advisory services in semi-arid regions of southern India,” Front Sustain Food Syst, vol. 2023; 7. [CrossRef]

- P. Roudier, B. Sultan, P. Quirion, and A. Berg, “The impact of future climate change on West African crop yields: What does the recent literature say?,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1073–1083, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Jalloh, G. C. Nelson, T. S. Thomas, R. Zougmoré, and H. Roy-Macauley, “West African Agriculture and Climate Change: A Comprehensive Analysis Issue Brief,” 2013.

- J. Knox, T. Hess, A. Daccache, and T. Wheeler, “Climate change impacts on crop productivity in Africa and South Asia,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 7, no. 2012; 3. [CrossRef]

- L. Dibba, A. Diagne, S. C. Fialor, and F. Nimoh, “DIFFUSION AND ADOPTION OF NEW RICE VARIETIES FOR AFRICA (NERICA) IN THE GAMBIA.” In African Crop Science Journal (Vol. 20).

- A. Diagne, E. A. Diagne, E. Amovin-Assagba, K. Futakuchi, and M. C. S. Wopereis, “Estimation of cultivated area, number of farming households and yield for major rice-growing environments in Africa.,” in Realizing Africa’s rice promise, CABI, 2013, pp. 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Arouna, J. C. Lokossou, M. C. S. Wopereis, S. Bruce-Oliver, and H. Roy-Macauley, “Contribution of improved rice varieties to poverty reduction and food security in sub-Saharan Africa,” Glob Food Sec, vol. 14, pp. 54–60, Sep. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Anderson, “International Institute for Environment and Development Tracking adaptation and measuring development: Enabling evaluation of the effectiveness of climate change adaptation.

- K. Van Der Geest and K. Warner, “Editorial: Loss and damage from climate change: emerging perspectives,” 2015. International Journal of Global Warming.

- J. Bayala, J. Sanou, Z. Teklehaimanot, A. Kalinganire, and S. J. Ouédraogo, “Parklands for buffering climate risk and sustaining agricultural production in the Sahel of West Africa,” Curr Opin Environ Sustain, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 28–34, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mbow, P. Smith, D. Skole, L. Duguma, and M. Bustamante, “Achieving mitigation and adaptation to climate change through sustainable agroforestry practices in Africa,” Curr Opin Environ Sustain, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 8–14, Feb. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. T. Partey, R. B. Zougmoré, M. Ouédraogo, and B. M. C: Campbell, “Developing climate-smart agriculture to face climate variability in West Africa: Challenges and lessons learnt, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Araya, J. P. Mitchell, J. W. Hopmans, and T. A. Ghezzehei, “Long-term impact of cover crop and reduced disturbance tillage on soil pore size distribution and soil water storage,” SOIL, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 177–198, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Charles Boliko, “FAO and the Situation of Food Security and Nutrition in the World,” 2019. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology.

- S. Awuni, F. Adarkwah, B. D. Ofori, R. C. Purwestri, D. C. Huertas Bernal, and M. Hajek, “Managing the challenges of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in Ghana,” , 2023, Elsevier Ltd. 01 May. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).