Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Define a Stylized New Zealand Based, Low-Lying, Coastal, Dairy Farm as a Case Study

- A rain-fed (i.e. non-irrigated) pastoral dairy farm at the national average size of 162 hectares (Statistica 2025 a), with the national average stock rate of 2.76 dairy cows/ha (Statistica 2025 b). An average operating profit of NZD$3300/ha. This is based on average national operating profits reported over the previous seven years (see Dairy NZ 2025).

- A farm located in an area already at risk of periodic river flooding and where the local/ regional council already operates some form of flood protection (e.g., stop banks) or drainage system from which people benefit

- Generally flat land such that the distance from groundwater to the surface of the land is similar across the farm.

- A farm operating on land that initially responds well to drainage interventions. Our cost and operating profit assumptions are based on this.

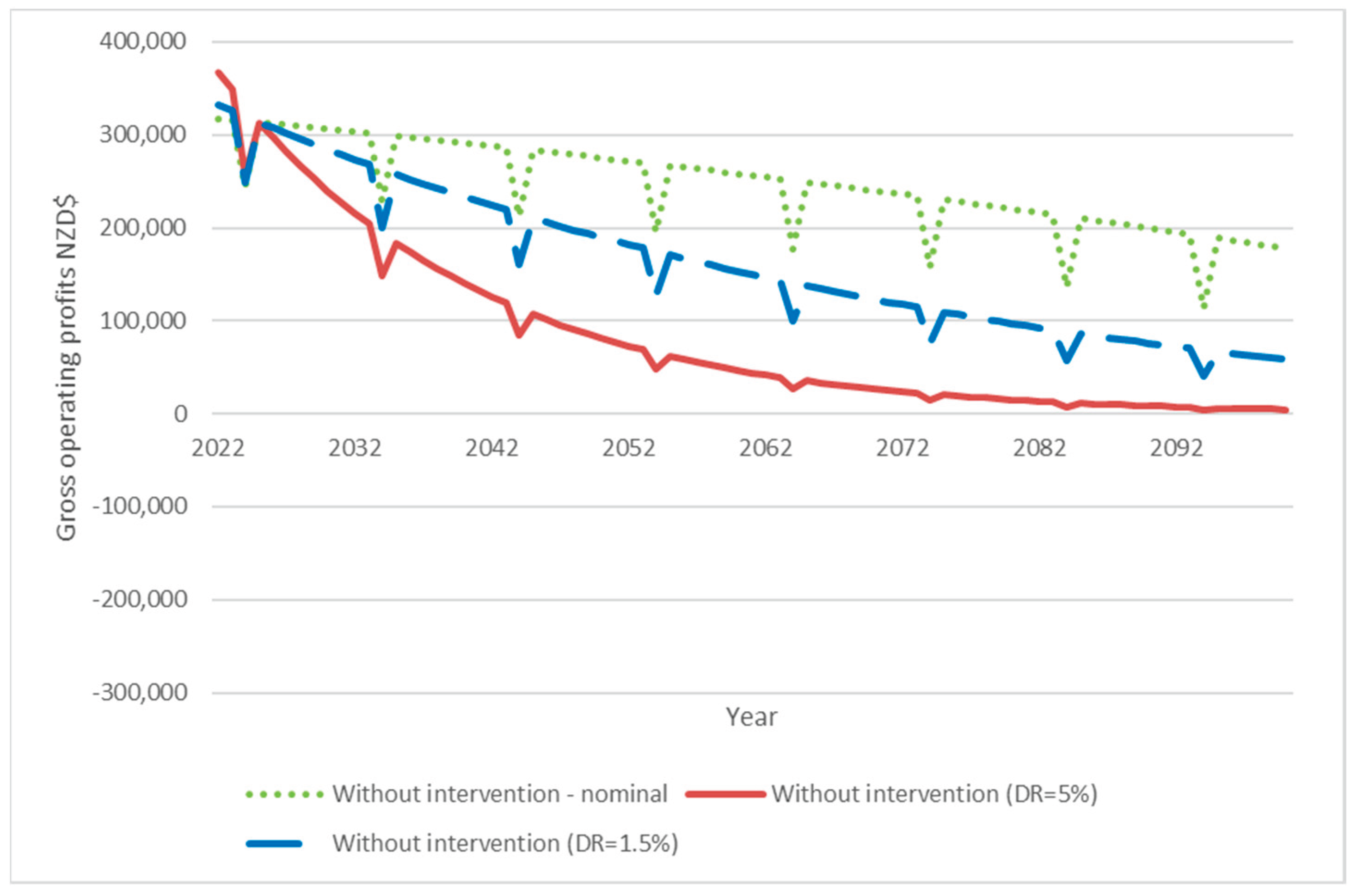

2.2. Consider Slow Onset Threats – Rising Groundwater

- Groundwater starting at 1m (GW1) below the ground surface of coastal land and rising at 4.5 mm per year to sit at around 0.7 metres from the surface by year 2100, without intervention.

- Groundwater starting at 0.7m below the ground surface of the coastal land rising at 4.5 mm per year, to sit around 0.4 metres from the surface by year 2100, without intervention.

Potential Impact on Operational Profits

2.3. Consider Sudden Onset Threats – River Flooding

2.4. Consider Adaptation Actions

- Approaches that enhance the absorptive capacity of systems to manage negative events using predetermined coping responses in order to preserve and restore essential structures and functions. Actions under this approach enable farming systems to cope with the impacts of a shock in the short run.

- Approaches that enhance the adaptive capacity of systems to adjust or modify so they can moderate harm and or benefit from opportunities, in order to continue functioning without major qualitative changes. Actions under this approach enable farming systems to better cope with climate change over the medium run through incremental change.

- Approaches that fundamentally change systems (transformational capacity). Actions under this approach involve long-term structural or systematic change, such as developing new production systems or investing in institutional change.

2.4.1. Absorptive Capacity Responses

Wintering-Off

2.4.2. Adaptive Capacity Responses

- Over time, sea level rise exacerbates fluvial flood risk, so land may require higher drainage services (Class A drainage) to prevent overflow.

- Ongoing sea level rise can potentially increase river stage such that Class A does not prevent overflow, so pumping is required as well. In such cases, we assume pump services are required for 25 per cent of land every year to help recover from regular flooding.

- Research conducted on farms to manage diffuse pollution (Matthews et al. 2024) which applies to a generic earth excavation value of NZD $10/m3 inclusive for earth moving, equipment transport and labor.

- The Waikato River Authority’s estimates fencing at NZD $9.20 per meter for 3-wire electric fencing in the Waikato in 2022 (Waikato River Authority 2022) and adjust for inflation to assume a cost of $10 per meter. We assume fencing is established on both sides of the drainage ditch and lasts 20 years (this is a general assumption as in some areas fencing may only be needed on one side of paddocks some areas may need on both sides).

- Data from Waikato River Authority (2022) indicates fence installation costs (e.g., labor, land preparation, transportation etc.) to be in the order of NZD $5,815.38/km in 2022. We update these costs to 2024 values (Appendix G) although values will vary according to landscape, any pre-existing access to equipment and availability of ‘free’ labor (e.g., farmer labor) (Appendix G).

- Tall fescue is planted as part of standard pasture renewal today

- Tall fescue is planted as part of standard pasture renewal in 20 years’ time

- Ryegrass is actively removed and replaced at cost by tall fescue.

- Today 15% of land is converted

- Yr 20 30% of land is converted

- Yr 40 45% of land is converted

- Yr 60 60% of land is converted.

- Consultations conducted by NIWA to assess the costs of wetlands construction in New Zealand (see Matthews et al. 2024) reveal that landscaping (vegetating) for constructed wetlands for farm management purposes to be around NZD$48,000 /ha (personal communication), while

- Saltmarsh restoration in the Bay of Plenty is reported to be between NZD $20,000 and NZD $190,000/ha, with an average cost of NZD $30,000/ha, not including the cost of the land (Bulmer et al. 2025 citing Bay of Plenty Regional Council as a personal communication). These costs are indicative pricing estimated via common approach of planting (e.g., average speed of planting), labor conditions (e.g., if the planting is a volunteer labor based, the hourly rates are generated by New Zealand minimum wage). Therefore, these costs are also useful guidance for other non-tidal species.

- Bayraktarov et al. (2016) estimated average cost of mangrove restoration to be in the value of USD$52,000/ha.

- Cumulative carbon sequestration rates of 0.64 tC/ha/y for restored saltmarsh and 0.89 tC/ha/y for mangrove (Bulmer et al., 2024).

- tonnes of CO2 stored in the wetland can generate 1 tonne of accumulated carbon (Parker et al. 2024; Brasell 1996).

2.4.3. Transformative Capacity Responses

- Today 15% of land is converted

- Yr 20 30% of land is converted

- Yr 40 45% of land is converted

- Yr 60 60% of land is converted.

- An agrivoltaic system would be expected to lower financial returns to the dairy farmer compared to conventional farming, and consequently

- Due to the relatively high return to farmers of dairy farming, agrivoltaic approaches are likely to be better suited to non-productive dairy areas or might better suit the installation of panels on shed roofs, rather than agrivoltaics production per se (Brent et al. 2023; Vaughan et al. 2023).

2.5. Estimate Economic Impacts

3. Results

3.1. Gross Values Without Change in Management

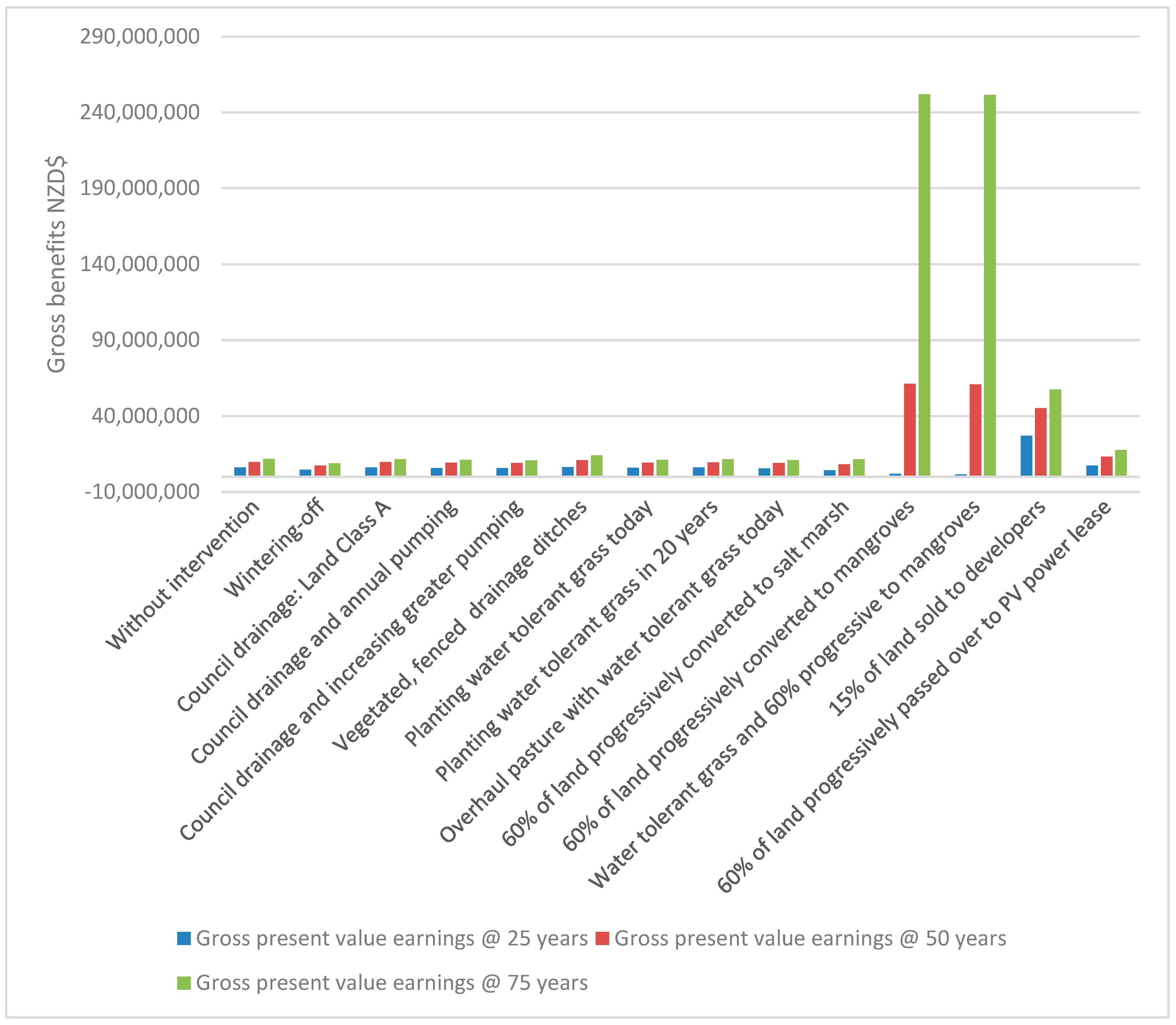

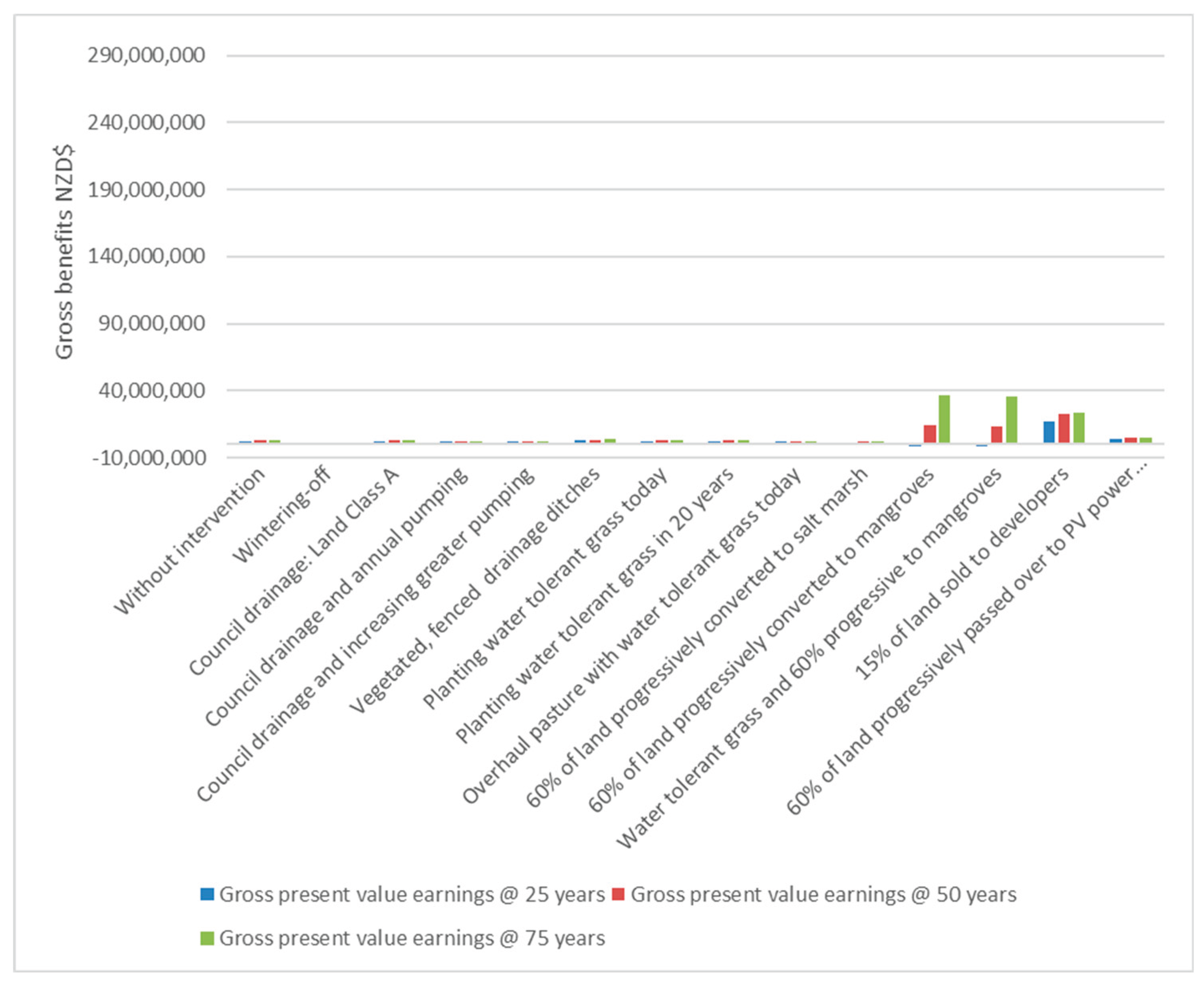

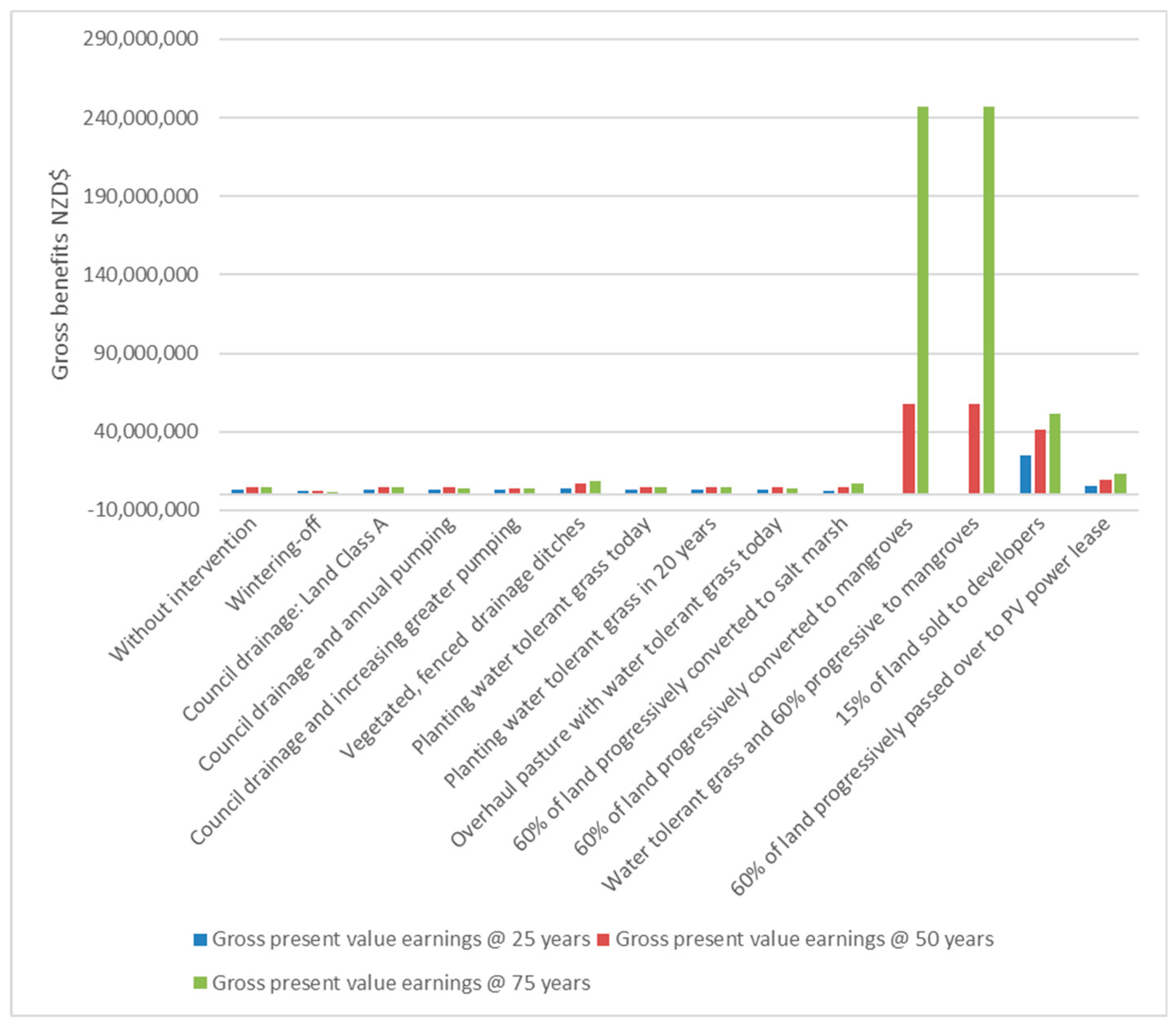

3.2. Gross Values with Change

|

GW=1000 DR=5% |

GW=700 DR=5% |

GW=1000 DR=1.5% |

GW=700 DR=1.5% |

||

| 1 | Without intervention | 5,717,885 | 2,953,884 | 11,772,004 | 4,756,297 |

| 2 | Wintering off | 4,362,463 | 1,598,462 | 8,748,402 | 1,732,695 |

| 3 | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 5,608,498 | 2,844,497 | 11,566,366 | 4,550,659 |

| 4 | Council upgrades and pumping | 5,368,375 | 2,604,374 | 11,029,015 | 4,013,308 |

| 5 | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 5,318,944 | 2,554,943 | 10,779,651 | 3,763,944 |

| 6 | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches …? | 6,232,614 | 3,833,860 | 13,977,163 | 8,609,193 |

| 7 | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 5,427,662 | 2,802,650 | 11,172,048 | 4,509,017 |

| 8 | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 5,618,528 | 2,914,876 | 11,421,582 | 4,654,534 |

| 9 | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 5,148,212 | 2,523,198 | 10,892,598 | 4,229,567 |

| 10 | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 4,465,110 | 2,376,144 | 11,460,710 | 6,882,212 |

| 11 | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 38,316,957 | 36,227,992 | 251,988,764 | 247,410,267 |

| 12 | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 38,052,304 | 36,068,387 | 251,511,343 | 247,163,038 |

| 13 | Sale of land to developers | 26,079,681 | 23,730,280 | 57,491,499 | 51,528,148 |

| 14 | Lease of land for PV power | 7,494,274 | 5,405,309 | 17,640,932 | 13,062,435 |

| GW=1000 DR=5 |

GW=700 DR=5 |

GW=1000 DR=1.5 |

GW=700 DR=1.5 |

||

| 1 | Without intervention | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| 2 | Wintering off | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| 3 | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 |

| 4 | Council upgrades and pumping | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 5 | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 |

| 6 | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches …? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 7 | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 8 | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 7 | 7 | 9 | 8 |

| 9 | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 10 | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 13 | 13 | 8 | 6 |

| 11 | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | Sale of land to developers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | Lease of land for PV power | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

3.2. Net Benefits of Change

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Gross present value earnings @ 75 years | Ranks gross benefits | NPV @75 years | NPV rank @ 75 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Without intervention | 5,717,885 | 6 | ||

| 2. | Wintering off | 4,362,463 | 14 | -1,355,422 | 13 |

| 3. | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 5,608,498 | 8 | -109,387 | 7 |

| 4. | Council upgrades and pumping | 5,368,375 | 10 | -349,510 | 9 |

| 5. | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 5,318,944 | 11 | -349,510 | 9 |

| 6. | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches | 6,232,614 | 5 | 514,729 | 5 |

| 7. | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 5,427,662 | 9 | -290,223 | 8 |

| 8. | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 5,618,528 | 7 | -99,357 | 6 |

| 9. | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 5,148,212 | 12 | -569,673 | 11 |

| 10. | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 4,465,110 | 13 | -1,252,775 | 12 |

| 11. | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 38,316,957 | 1 | 32,599,072 | 1 |

| 12. | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 38,052,304 | 2 | 32,334,419 | 2 |

| 13. | Sale of land to developers | 28,915,651 | 3 | 23,197,766 | 3 |

| 14. | Lease of land for PV power | 7,494,274 | 4 | 1,776,389 | 4 |

| Gross present value earnings @ 75 years | Ranks gross benefits | NPV @75 years | NPV rank @ 75 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Without intervention | 2,953,884 | 6 | ||

| 2. | Wintering off | 1,598,462 | 14 | -1,355,422 | 13 |

| 3. | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 2,844,497 | 8 | -109,387 | 7 |

| 4. | Council upgrades and pumping | 2,604,374 | 10 | -349,510 | 9 |

| 5. | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 2,554,943 | 11 | -349,510 | 9 |

| 6. | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches | 3,833,860 | 5 | 879,976 | 5 |

| 7. | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 2,802,650 | 9 | -151,234 | 8 |

| 8. | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 2,914,876 | 7 | -39,008 | 6 |

| 9. | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 2,523,198 | 12 | -430,686 | 11 |

| 10. | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 2,376,144 | 13 | -577,740 | 12 |

| 11. | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 36,227,992 | 1 | 33,274,108 | 1 |

| 12. | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 36,068,387 | 2 | 33,114,503 | 2 |

| 13. | Sale of land to developers | 26,566,250 | 3 | 23,612,366 | 3 |

| 14. | Lease of land for PV power | 5,405,309 | 4 | 2,451,425 | 4 |

| Gross present value earnings @ 75 years | Ranks gross benefits | NPV @75 years | NPV rank @ 75 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Without intervention | 11,772,004 | 6 | ||

| 2. | Wintering off | 8,748,402 | 14 | -3,023,602 | 13 |

| 3. | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 11,566,366 | 7 | -205,638 | 6 |

| 4. | Council upgrades and pumping | 11,029,015 | 11 | -742,989 | 10 |

| 5. | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 10,779,651 | 13 | -742,989 | 10 |

| 6. | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches | 13,977,163 | 5 | 2,205,159 | 5 |

| 7. | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 11,172,048 | 10 | -599,956 | 9 |

| 8. | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 11,421,582 | 9 | -350,421 | 8 |

| 9. | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 10,892,598 | 12 | -879,406 | 12 |

| 10. | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 11,460,710 | 8 | -311,294 | 7 |

| 11. | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 251,988,764 | 1 | 240,216,760 | 1 |

| 12. | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 251,511,343 | 2 | 239,739,339 | 2 |

| 13. | Sale of land to developers | 63,837,880 | 3 | 52,065,876 | 3 |

| 14. | Lease of land for PV power | 17,640,932 | 4 | 5,868,928 | 4 |

| Gross present value earnings @ 75 years | Ranks gross benefits | NPV @75 years | NPV rank @ 75 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Without intervention | 4,756,297 | 7 | ||

| 2. | Wintering off | 1,732,695 | 14 | -3,023,602 | 13 |

| 3. | Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 4,550,659 | 9 | -205,638 | 8 |

| 4. | Council upgrades and pumping | 4,013,308 | 12 | -742,989 | 11 |

| 5. | Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 3,763,944 | 13 | -992,353 | 12 |

| 6. | Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches | 8,609,193 | 5 | 3,852,896 | 5 |

| 7. | Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 4,509,017 | 10 | -247,280 | 9 |

| 8. | Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 4,654,534 | 8 | -101,763 | 7 |

| 9. | Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 4,229,567 | 11 | -526,730 | 10 |

| 10. | Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 6,882,212 | 6 | 2,125,916 | 6 |

| 11. | Progressive conversion to mangroves | 247,410,267 | 1 | 242,653,970 | 1 |

| 12. | Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 247,163,038 | 2 | 242,406,741 | 2 |

| 13. | Sale of land to developers | 57,874,529 | 3 | 53,118,232 | 3 |

| 14. | Lease of land for PV power | 13,062,435 | 4 | 8,306,138 | 4 |

Appendix B. Examples of Responses to Climate Change and Sea Level Rise

| Hazard | General impact to farm | Examples of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Rising water tables, seawater intrusion | Increasing waterlogging of soil over time, reducing pasture productivity. Potential soil salinisation. | Drainage ditches, tile drains, pumps, salt-tolerant species, land conversion, raised pasture beds, seasonal cut and carry pasture production systems, controlled water table systems, alternative land use. |

| Greater storm surges | Periodic intense saturation of land, including saltwater, affecting pasture and damaging infrastructure. | Higher stop banks, pumps, coastal barriers, relocation of vulnerable infrastructure, salt-tolerant species, improved early warning systems. |

| Flooding | Periodic inundation from rainfall or swollen rivers, reducing productivity and damaging farm assets. | Higher stop banks, pumps, floodplain zoning, elevated buildings/infrastructure, pasture rotation, flood-compatible land use. |

Appendix C. Dry Matter Production for Perennial Rye Grass and the Distance of Groundwater from the Land Surface Equation

Appendix D. Scenarios and Responses Explored

| Response | Absorptive, adaptive or transformative actions | |

|---|---|---|

| No action | Absorptive | |

| farmers maintain production by wintering-off livestock for 4 months every year? | Absorptive | |

| farmers hold the line by upgrading the Council level of flood control and drainage service from none to Land Class A? | Adaptive | |

| farmers hold the line by upgrading the Council level of flood control and drainage service and paying to pump of 15% more land each 25 years? | Adaptive | |

| farmers could hold the line through Council upgrades level of service alone, pumping of 25% of land each year and increasing pumped area by 15% more every 25 years …? | Adaptive | |

| farmers hold the line through 1 km of vegetated, fenced drainage ditches? | Adaptive | |

| farmers plant water tolerant grass as part of standard pasture renewal today to cope with future rising groundwater? | Adaptive | |

| Farmers overhaul (replant at cost) existing pasture and plant water tolerant grass …? | Adaptive | |

| farmers plant water tolerant grass in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal? | Adaptive | |

| 15% of highest water table/most flood-prone land is converted to saltmarsh every 25 yrs and farming elsewhere continues unchanged? | Transformative | |

| 15% of highest water table/most flood-prone land is converted to mangrove every 25 yrs and farming elsewhere continues unchanged? | Transformative | |

| 15% of highest water table/most flood-prone land is converted to wetlands every 25 yrs and water tolerant grass is planted as well? | Transformative | |

| 15% of prime land is sold to developers and farming elsewhere continues unchanged? | Transformative | |

| 15% of highest water table/most flood-prone land is leased for PV power at $4k/ha every 25 yrs and farming elsewhere continues unchanged? | Transformative |

| Impact of flood hazard | Impact on groundwater rise hazard (waterlogging | Other impacts | Assumption related to operating profits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation 1: Wintering off | reduced losses (stock protected) | no change | basic operating profit remains but waterlogged pasture losses remain | |

| Adaptation 2: Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | no flooding now | no change | basic operating profit remains but waterlogged pasture losses remain | |

| Adaptation 3: Council upgrades and pumping | no flooding now | no change | basic operating profit remains but waterlogged pasture losses remain | |

| Adaptation 4: Council upgrades and progressively higher pumping | no flooding now | no change | basic operating profit remains but waterlogged pasture losses remain | |

| Adaptation 5: Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches | no change | no waterlogging | basic operating profits remains at same level as Year 1 | |

| Adaptation 6: Water tolerant grass today | no change | reduced waterlogging | productivity reduced by less preferred pasture but mitigated by lower waterlogging losses | |

| Adaptation 7: Water tolerant grass in 20 years' time | no change | reduced waterlogging | productivity reduced by less preferred pasture but mitigated by lower waterlogging losses | |

| Adaptation 8: Water tolerant grass replanted at cost | no change | reduced waterlogging | productivity reduced by less preferred pasture but mitigated by lower waterlogging losses | |

| Adaptation 9: Convert some land to salt marsh over time | no change | no change | environmental benefits | basic operating profit/ha remains the same as without action |

| Adaptation 10: Convert some land to mangroves over time | no change | no change | environmental benefits | basic operating profit/ha remains the same as without action |

| Adaptation 11: Convert some land to mangroves over time + water tolerant grass | no change | no waterlogging | environmental benefits | productivity in remaining farm reduced by less preferred pasture but mitigated by lower waterlogging losses |

| Adaptation 12: Sell some land to developers | no change | no change | basic operating profit/ha for remaining farm remains the same as without action | |

| Adaptation 13: Lease some land for PV power | no change | no change | basic operating profit/ha for remaining farm remains the same as without action |

Appendix E. Net Present Value Equation

Appendix F. The Land Class Categories

| Level of service | Annual drainage cost | Annual pumping cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher ↕ Lower |

Land Class A drainage and Land Class A pumping | NZD $68.17/ha | NZD $289.43/ha pumped* |

| Land Class A drainage | NZD $68.17/ha | ||

| Land Class B drainage | NZD $42.26/ha | ||

| Normal | [not targeted] | [not targeted] | |

Appendix G. Assumed Cost to Install Fencing of Drainage Ditches

| Item | Cost NZD$ | Total cost per 1000 metres of watercourse | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-wire electric fence | 10/m | 10000 | |

| Digger | 180.95/hour | 2533.3 |

$166.75 per hour, adjusted for inflation Assumes 1 day (7 hours) per side of the river - a total of 2 days |

| Transportation | 399.34 | 399.34 | $368, adjusted for inflation |

| Labour | 74.88/hour for contractor; 131.03/hour for driver | 2,882.74 |

$69 per hour for contractor, plus $120.75 per hour for driver, adjusted for inflation Assumes 1 day (7 hours) per side of the river - a total of 2 days |

| TOTAL (2022 values) | 5,815.38 | ||

| TOTAL (2024 values) | 6,221.44 | adjusted for inflation. |

Appendix H. Net Present Values of Responses

| GW=1000 DR=5% |

GW=700 DR=5% |

GW=1000 DR=1.5% |

GW=700 DR=1.5% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wintering off | -1,355,422 | -1,355,422 | -3,023,602 | -3,023,602 | |

| Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | -109,387 | -109,387 | -205,638 | -205,638 | |

| Council upgrades and pumping | -349,510 | -349,510 | -742,989 | -742,989 | |

| Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | -349,510 | -349,510 | -742,989 | -992,353 | |

| Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches …? | 514,729 | 879,976 | 2,205,159 | 3,852,896 | |

| Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | -290,223 | -151,234 | -599,956 | -247,280 | |

| Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | -99,357 | -39,008 | -350,421 | -101,763 | |

| Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | -569,673 | -430,686 | -879,406 | -526,730 | |

| Progressive conversion to salt marsh | -1,252,775 | -577,740 | -311,294 | 2,125,916 | |

| Progressive conversion to mangroves | 32,599,072 | 33,274,108 | 240,216,760 | 242,653,970 | |

| Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 32,334,419 | 33,114,503 | 239,739,339 | 242,406,741 | |

| Sale of land to developers | 20,361,796 | 20,776,396 | 45,719,495 | 46,771,851 | |

| Lease of land for PV power | 1,776,389 | 2,451,425 | 5,868,928 | 8,306,138 |

| GW=1000 DR=5 |

GW=700 DR=5 |

GW=1000 DR=1.5 |

GW=700 DR=1/5 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wintering off | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | |

| Council upgrades from none/Class B to Land Class A | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | |

| Council upgrades and pumping | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Council upgrades and increasing extents of pumping | 9 | 9 | 10 | 12 | |

| Vegetated, fenced drainage ditches …? | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Water tolerant grass planted today as part of standard pasture renewal | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | |

| Water tolerant grass planted in 20 years’ time as part of standard pasture renewal | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | |

| Replacing pasture with water tolerant grass at cost | 11 | 11 | 12 | 10 | |

| Progressive conversion to salt marsh | 12 | 12 | 7 | 6 | |

| Progressive conversion to mangroves | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Progressive conversion to mangroves plus water tolerant grass | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Sale of land to developers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Lease of land for PV power | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Appendix I. Water-Tolerant Grasses Species - Tall Fescue (Festuca Arundinacea)

| Operating profit NZD$ | Perennial ryegrass monoculture | Fall fescue monoculture | Reduction in profit with tall fescue % |

|---|---|---|---|

| At milk price $4.10/kg MS | 707 | 643 | - 9.95 |

| At milk price $6.40/kg MS | 3,781 | 3,611 | - 4.71 |

| At milk price $8.50/kg MS | 6,588 | 6,321 | - 4.22 |

| 1 | Based on a 1988 value of USD$ 15,230,769 p.a. converted to 1988 New Zealand dollars (USD$:NZD in 1988 was approximately 1:1.4333 (https://www.poundsterlinglive.com/bank-of-england-spot/historical-spot-exchange-rates/usd/USD-to-NZD-1988. Accessed 8 September 2025) and then converted to present values using the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation calculator (https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/about-monetary-policy/inflation-calculator). |

References

- Asian Development Bank (2017) Guidelines for the economic analysis of projects. Mandaluyong City, Philippines. Available online at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32256/economic-analysis-projects.pdf. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Amanambu, A., Obarein, A., Mossa, J., Li, L., Ayeni, S., Balogun, O., Oyebamiji, A. and Ochege, F. (2020) Groundwater system and climate change: Present status and future considerations. Journal of Hydrology, Volume 589, October 2020, 125163. [CrossRef]

- Anon (2023) The whole story. Available online at: https://www.thewholestory.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Solar-farming-final.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- ANZ Bank (2025) Agribusiness rates, fees and agreements. Available online at: https://www.anz.co.nz/rates-fees-agreements/agri/. Accessed 29 July 2025.

- ASB Bank (2025) Business and rural loan interest rates and fees. Available online at: https://www.asb.co.nz/business-loans/interest-rates-fees.html. Accessed 29 July 2025.

- Auckland Council (Undated) Map of Te Arai Drainage District land classification – Rodney drainage districts land classification. Available online at: https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/property-rates-valuations/Documents/map-rodney-drainage-districts-land-classification.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2025.

- Bakker, J.P. (2012) Restoration of salt marshes. Restoration ecology: the new frontier, 248-262.

- Bandh, S. A., Shafi, S., Peerzada, M., Rehman, T., Bashir, S., Wani, S. A., and Dar, R. (2021) Multidimensional analysis of global climate change: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(20), 24872-24888. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktarov E., Saunders M.I., Abdullah, S., Mills, M., Beher, J., Possingham, H.P., Mumby, P.J., Lovelock, C.E. (2016) The cost and feasibility of marine coastal restoration. Ecological Applications 26:1055–1074. [CrossRef]

- Befus, K., Barnard, P. L., Hoover, D. J., Finzi Hart, J., and Voss, C. I. (2020) Increasing threat of coastal groundwater hazards from sea-level rise in California. Nature Climate Change, 10(10), 946-952. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, A., and Känzig, D. R. (2024) The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Change: Global vs. Local Temperature.

- Bosserelle, A. L., and Hughes, M. W. (2024) Practitioner perspectives on sea-level rise impacts on shallow groundwater: Implications for infrastructure asset management and climate adaptation. Urban Climate, 58, 102195. [CrossRef]

- Bosserelle, A. L., Morgan, L. K., and Hughes, M. W. (2022) Groundwater rise and associated flooding in coastal settlements due to sea-level rise: a review of processes and methods. Earth's Future, 10(7), e2021EF002580. [CrossRef]

- Brasell, R. (1996) New Zealand's Net Carbon Dioxide Emission Stabilisation Target. Agenda. Vol. 3, No. 3 (1996), pp. 329-340 (12 pages). ANU. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43199385. Accessed 27 March 2025. [CrossRef]

- Braun, R. and Patton. A. (2024) Growth responses to waterlogging stress among cool-season grass species. Grass and Forage Science. Short Communication. Accessed 3 September 2025. [CrossRef]

- Brent, A. and Iorns, C. (2024) Solar farms can eat up farmland—but ‘agrivoltaics’ could mean the best of both worlds. Using agricultural land for both renewable electricity generation and farming can bring economic benefits for farmers. 10 June. Available online at: https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/news/2024/06/solar-farms-can-eat-up-farmlandbut-agrivoltaics-could-mean-the-best-of-both-worlds. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- Brent, A., Vaughan, A., Fitzgerald, M., Wright, E. and Kueppers, J. (2023) Agrivoltaics: Integrating Solar Energy Generation with Livestock Farming in the Canterbury Region of Aotearoa New Zealand. 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Technology and Engineering (i-COSTE) | 979-8-3503-2971-1/23/$31.00 ©2023 IEEE |. [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, R. H., Stewart-Sinclair, P. J., Lam-Gordillo, O., Mangan, S., Schwendenmann, L., and Lundquist, C. J. (2024) Blue carbon habitats in Aotearoa New Zealand—opportunities for conservation, restoration, and carbon sequestration. Restoration ecology, 32(7), e14225. [CrossRef]

- Caretta, M.A., A. Mukherji, M. Arfanuzzaman, R.A. Betts, A. Gelfan, Y. Hirabayashi, T.K. Lissner, J. Liu, E. Lopez Gunn, R. Morgan, S. Mwanga, and S. Supratid (2022) Water. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 551–712. [CrossRef]

- Carleton, T. A., and Hsiang, S. M. (2016). Social and economic impacts of climate. Science, 353(6304), aad9837.

- Cobourn K (2023) Climate change adaptation policies to foster resilience in agriculture: Analysis and stocktake based on UNFCCC reporting documents. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers.

- Cox, S.C., Ettema, M.H.J., Chambers, L.A., Easterbrook-Clarke, L.H. and Stevenson, N.I. (2023) Dunedin groundwater monitoring, spatial observations and forecast conditions under sea-level rise. Lower Hutt, N.Z.: GNS Science. GNS Science report 2023/43. 111 p.;. [CrossRef]

- Craig, H., Wild, A., and Paulik, R. (2023) Dairy farming exposure and impacts from coastal flooding and sea level rise in Aotearoa-New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 98, 104079. [CrossRef]

- Dairy Australia (2025) Pasture Options. Available online at: https://www.dairyaustralia.com.au/feeding-and-farm-systems/pastures/pasture-options. Accessed 1 September 2025.

- DairyNZ (2024 a) Tall fescue. Available online at: https://www.dairynz.co.nz/feed/pasture-species/tall-fescue/. Accessed 3 April 2025.

- DairyNZ (2024 b) Ryegrass. Available online at: https://www.dairynz.co.nz/feed/pasture-species/ryegrass/#:~:text=Production%20of%20perennial%20ryegrass%2Dbased,ryegrass%20pastures%20can%20last%20indefinitely. Accessed 17 December 2024.

- DairyNZ (2024 c) New Zealand Dairy Statistics. Available online. Accessed 8 September 2025.

- DairyNZ (2015) Waterway Technote: Drains. Available online at: https://www.dairynz.co.nz/media/ztbb3v40/drains-waterway-technote.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2025.

- DairyNZ (2025) Farm economics. Available online at: https://connect.dairynz.co.nz/EconTracker/. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- Dao, P., Heuzard, A., Le, T., Zhao, J., Yin, R., Shang, C. and Fan, C. (2024) The impacts of climate change on groundwater quality: A review. Science of The Total Environment. Volume 912, 20 February 2024, 169241. [CrossRef]

- Department of Conservation, (2007) The economic values of Whangamarino Wetland. May. Available online at: https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/conservation/threats-and-impacts/benefits-of-conservation/economic-values-whangamarino-wetland.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2025.

- Department of Conservation (Undated) Wetlands protection guide. Available online at: https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/habitats/wetlands/wetlands-protection/. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Easton, H., and Fitzgerald, R. (1994) Tall fescue in Australia and New Zealand, New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 37:3, 405-417. [CrossRef]

- EQC (2023) Natural Hazard Risk Tolerance Literature Review. A companion document to Toka Tū Ake EQC’s Risk Tolerance Methodology July.

- ESCAP (2019) The Disaster RiskScape across Asia-Pacific. Pathways for Resilience, Inclusion and Development. Asia Pacific Report 2019. Available online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/APDR%202019%20Annexes_0.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2018) The future of food and agriculture – Alternative pathways to 2050. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome. Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e51e0cf0-4ece-428c-8227-ff6c51b06b16/content. Accessed 22 April 2025.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (Undated) Expected annual loss. Available online at: https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/expected-annual-loss. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- Forest and Bird (2023) Bring back wetlands.30 May. Available online at: https://www.forestandbird.org.nz/resources/bring-back-wetlands. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Foundation for Sustainable Development (2021) Ecosystem Services Valuation Database. Available online at: https://www.esvd.net/. Accessed 3 April 2025.

- Frisk, C. A., Xistris-Songpanya, G., Osborne, M., Biswas, Y., Melzer, R., and Yearsley, J. M. (2022). Phenotypic variation from waterlogging in multiple perennial ryegrass varieties under climate change conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 954478. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, P. P., Tang, Q., Wang, J., Zhang, C., Xu, X., Zhang, R., ... & Ratcliffe, J. L. (2026). Ecohydrological resilience to short-term warming in a high-altitude peatland under different water table levels. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 116, 108065. [CrossRef]

- Garrett, L. (2023) Potential for paludiculture in New Zealand. Considerations for the Lower Waikato. Report prepared for NIWA: Future Coasts Aotearoa May.

- Gibson, P, Lewis, H., Campbell, I., Rampal, N., Fauchereau, N., and Harrington, L. (2025) Downscaled Climate Projections of Tropical and Ex-Tropical Cyclones Over the Southwest Pacific. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. No. 130. e2025JD043833. [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V. (1991). Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 89(4), 379-398. [CrossRef]

- Habel, S., Fletcher, C. H., Barbee, M. M., & Fornace, K. L. (2024) Hidden threat: the influence of sea-level rise on coastal groundwater and the convergence of impacts on municipal infrastructure. Annual Review of Marine Science, 16(1), 81-103. [CrossRef]

- Hack, K. (2008) Chapter II.6 - Hot isostatic pressing of Al–Ni alloys. In The SGTE Casebook. Thermodynamics At Work. Second Edition. Woodhead Publishing.

- Hamlington B., Bellas-Manley A., Willis J., Fournier, S., Vinogradova, N., Nerem, R., Piecuch, C., Thompson, P. and Kopp, R. (2024) The rate of global sea level rise doubled during the past three decades. Commun Earth Environ 5:601. [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, K., Fitzharris, B., Bates, B. C., Harvey, N., Howden, S., Hughes, L., Salinger, J., and Warrick, R. A. (2007) Australia and New Zealand. In Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 507-540). Cambridge University Press.

- Horstman, E.M., Lundquist, C.J., Bryan, K.R., Bulmer, R.H., Mullarney, J.C., Stokes, D.J. (2018) The Dynamics of Expanding Mangroves in New Zealand. In: Makowski, C., Finkl, C. (eds) Threats to Mangrove Forests. Coastal Research Library, vol 25. Springer, Cham. International Carbon Action Partnership (2025) New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme. Available online at: https://icapcarbonaction.com/system/files/ets_pdfs/icap-etsmap-factsheet-48.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2025. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp.. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. A. (2012) Ecological restoration of the Wairio Wetland, Lake Wairarapa: Water table relationships and cost-benefit analysis of restoration strategies. MSc thesis Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington.

- Karri, R. R., Ravindran, G., Pingili, V., Mubarak, N. M., Ruslan, K. N., & Tan, Y. H. (2026). Integrating the Food-Energy-Water Nexus: Strategies for climate change mitigation with SDG alignment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 116, 108070. [CrossRef]

- Kerrisk, J. and Thomson, N. (1990) Effect of intensity and frequency of defoliation on growth of ryegrass, tall fescue and phalaris. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association 51: 135-138. [CrossRef]

- Ketabchi, H., Mahmoodzadeh, D., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., and Simmons, C. T. (2016) Sea-level rise impacts on seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers: Review and integration. Journal of Hydrology, 535, 235-255. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, W.T. (1988) Preserving the Whangamarino wetland: an application of the contingent valuation method. Massey University, NZ.

- Kumar, C. (2012) Climate Change and Its Impact on Groundwater Resources. RESEARCH INVENTY: International Journal of Engineering and Science. ISSN: 2278-4721, Vol. 1, Issue 5 (October 2012), PP 43-60. October.

- Lee, J., Clark, D., Clark, C., Waugh, C., Roach, C., Minnée, E., Glassey, C., Woodward, S., Woodfield, D. and Chapman, D. (2017) A comparison of perennial ryegrass- and tall fescue-based swards with or without a cropping component for dairy production: Animal production, herbage characteristics and financial performance from a 3-year farmlet trial. Grass Forage Sci. pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Vecchi, G., Smith, J. and Knutson, T. (2019) Causes of large projected increases in hurricane precipitation rates with global warming. Climate and Atmospheric Science. Vol. 2. Article number: 38. Available online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-019-0095-3#:~:text=The%20Clausius%2DClapeyron%20relation%20indicates,degree%20Celsius%20increase%20in%20temperature. ACCESSED 27 March 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J., Howard, T., Pardaens, A., Tinker, J., Holt, J., Wakelin, S., Milne, G., Leake, J., Wolf, J., Horsburgh, K., Reeder, T., Jenkins, G., Ridley, J., Dye, S. and Bradley, S. (2009) UK Climate Projections science report: Marine and coastal projections.

- MacKenzie, D., Brent, A. Hinkley, J. and Burmester, D. (2024) AgriPV Systems: Potential Opportunities for Aotearoa–New Zealand. A GIS Suitability Analysis. Paper presented to the AgriVoltaics World Conference 2022, Piacenza, Italy. [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.E., Friess, D.A., Peacock, M., Grinham, A., Taillardat, P., Rosentreter, J.A., Webb, J., Iram, N., Al-Haj, A.N., Macreadie, P.I. (2022) Methane and nitrous oxide emissions complicate the climate benefits of teal and blue carbon wetlands. One Earth 5, 1336-1341. [CrossRef]

- Maliva R (2021) Sea Level Rise and Groundwater. In: Climate Change and Groundwater: Planning and Adaptations for a Changing and Uncertain Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 113–153.

- Manda, A. K., and Klein, W. A. (2019) Adaptation strategies to address rising water tables in coastal environments under future climate and sea-level rise scenarios. In Coastal zone management (pp. 403-409). Elsevier.

- Martinkova, M. and Kysely, J. (2020) Overview of Observed Clausius-Clapeyron Scaling of Extreme Precipitation in Midlatitudes. Atmosphere. Vol. 11. No. 8. 86. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Y., Holland, P., Matheson, F., Craggs, R. and Tanner, C. (2024) Evaluating the Cost-Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure for Mitigating Diffuse Agricultural Contaminant Losses. Land. Vol. 13. No. 6. 748; [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D. (2023) Salt marsh a carbon sink opportunity. 16 March. RNZ. Available one at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/ldr/486092/salt-marsh-a-carbon-sink-opportunity. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Miller, A. (2020) Economics of Utility-Scale Solar in Aotearoa New Zealand: Forecasting Transmission and Distribution Network Connected 1 MW to 200 MW Utility-Scale Photovoltaic Solar to 2060. Prepared for the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. May.

- Milne, G. and Fraser, T. (1990) Establishment of 1600 hectares in dryland species around Oamaru/ Timaru. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association 52: 133-137. [CrossRef]

- Mimura, N., Pulwarty, R., Duc, D., Elshinnawy, I., Redsteer, M., Huang, H., Nkem, J. and Sanchez Rodriguez, R. (2014) Adaptation planning and implementation. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 869-898.

- Ministry for Primary Industries (2019) Climate Issues Facing Farmers Sustainable Land Management and Climate Change Research Programme. Prepared for the Ministry for Primary Industries. ISBN No: 978-1-98-859440-8 (online) April.

- Ministry for the Environment (2020 b) National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management. New Zealand.

- Ministry for the Environment (2020 a) Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020. New Zealand.

- Ministry for the Environment (2010) Part One: Climate change impacts on flooding. Available online at: https://environment.govt.nz/publications/preparing-for-future-flooding-a-guide-for-local-government-in-new-zealand/part-one-climate-change-impacts-on-flooding/. Accessed 13 May 2024.

- Ministry for the Environment (2021) Managing our wetlands A discussion document on proposed changes to the wetland regulations. New Zealand.

- Morgan, L. (2024) Sea-level rise impacts on groundwater: exploring some misconceptions with simple analytic solutions. Hydrogeology Journal (2024) 32:1287–1294 . [CrossRef]

- Morris, J., Beedell, J., and Hess, T. (2016) Mobilising flood risk management services from rural land: principles and practice. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 9(1), 50-68. [CrossRef]

- Mui NT, Zhou M, Parsons D and Smith, RW (2021) Aerenchyma formation in adventitious roots of tall fescue and cocksfoot under waterlogged condition. Agronomy 11, 2487. [CrossRef]

- Naish, T., Lawrence, J., Levy, R., Bell, R., van Uitregt, V. B., Hayward, B., Priestley, R., Renwick, J., and Boston, J. (2024 a) A Sea Change is Needed For Adapting to Sea-Level Rise in Aotearoa New Zealand. Policy Quarterly, 20(4), 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Naish, T., Levy, R., Hamling, J., Hreinsdottir, S., Kumar, P., Garner, G., Kopp, R., Golledge, N., Bell, R., Paulik, R., Lawrence, J., Denys, P., Gillies, T., Bengtson, S., Howell, A., Clark, K., King, D., Litchfield, N. and Newnham, R. (2024 b) The Significance of Interseismic Vertical Land Movement at Convergent Plate Boundaries in Probabilistic Sea-Level Projections for AR6 Scenarios: The New Zealand Case. Earth’s Future 12:e2023EF004165. [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Diary Exporter (2023) Solar leasing: Making money while the sun shines. July/August. Available online at: https://dairyexporter.co.nz/solar-leasing-making-money-while-the-sun-shines/#:~:text=Under%20a%20lease%20agreement%20the,to%20take%20the%20extra%20load. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- New Zealand Herald (2019) Elderly woman dies in flood waters on West Coast. 27 March. Available online at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/elderly-woman-dies-in-flood-waters-on-west-coast/3DM2IEDN7EYE6SRRGOHKCHXJUA/. Accessed 17 February 2025.

- New Zealand Herald (2023 b) Auckland flood victims: The four people killed in extreme and unprecedented weather event. 31 Jan. Available online at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/faces-of-the-flood-four-killed-across-auckland-and-waikato-in-extreme-and-unprecedented-weather-event/Z7VR72Z3YJAILCOAVOG4B72DXQ/. Accessed 17 February 2025.

- New Zealand Landcare Trust (2024) Fonterra announces $250,000 in grants for wetland restoration. Available online at: Fonterra announces $250,000 in grants for wetland restoration - NZ Landcare Trust https://landcare.org.nz/fonterra-announces-250000-in-grants-for-wetland-restoration/. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Nguyen, T. M. (2022) Morphological responses of cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata L.) and tall fescue (Lolium arundinaceum Schreb.) to waterlogging stress. University Of Tasmania. Thesis.

- Nicholls, R. J., and Cazenave, A. (2010) Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science, 328(5985), 1517-1520. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R. J., Hoozemans, F. M., and Marchand, M. (1999) Increasing flood risk and wetland losses due to global sea-level rise: regional and global analyses. Global Environmental Change, 9, S69-S87. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R., Wong, P., Burkett, V., Codignotto, J., Hay, J., McLean, R., Ragoonaden, S. and Woodroffe, C. (2007) Coastal systems and low-lying areas. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M., Canziani, O., Palutikof, J., van der Linden, P. and Hanson, C. (Eds.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. pp. 315-356.

- Parker, K. and Mainelli, M. (2024) What happens if we ‘burn all the carbon’? carbon reserves, carbon budgets, and policy options for governments. Royal Society of Chemistry. Environ. Sci.: Atmos. Vol. 4. pp. 435-454. [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (2015) Preparing New Zealand for rising seas: Certainty and Uncertainty. November. Available online at: https://pce.parliament.nz/media/fgwje5fb/preparing-nz-for-rising-seas-web-small.pdf. Accessed 18 November 2024.

- Patterson, M. and Cole, A. (2013) ‘Total economic value’ of New Zealand’s land-based ecosystems and their services. In Dymond J. (Ed.) Ecosystem services in New Zealand – conditions and trends. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln, New Zealand.

- Paulik, R., Crowley, K., Cradock-Henry, N., Wilson, T. and McSporran, A. (2021) Flood Impacts on Dairy Farms in the Bay of Plenty Region, New Zealand. Climate. Vol. 9. No. 30. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer W. T., Harper J. T. and O’Neel S. (2008) Kinematic constraints on glacier contributions to 21st-century sea-level rise. Science 321, 1340. [CrossRef]

- Pittock, B. and Wratt, D. (2001) Chapter 12. Australia and New Zealand. IPCC. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/wg2TARchap12.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- Purandare, J., de Sousa de Saboya, R., Bayraktarov, E., Boström-Einarsson, L., Carnell, P.E., Eger, A.M., Le Port, A., Macreadie, P.I., Reeves, S.E., van Kampen, P. (2024) Database for marine and coastal restoration projects in Australia and New Zealand. Ecological Management & Restoration 25, 14-20. [CrossRef]

- Rakkasagi, S., & Goyal, M. K. (2025). Protecting wetlands for future generations: A comprehensive approach to the water-climate-society nexus in South Asia. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 115, 107988. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, C., Gaston, T., Sadat-Noori, M., Glamore, W., Morton, J., Chalmers, A. (2023) Innovative tidal control successfully promotes saltmarsh restoration. Restoration Ecology 31, e13774. [CrossRef]

- Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (2024 a) Dairy and Arable Farms Drive Growth as Farm Sales Rise Across New Zealand. Available online at: https://www.reinz.co.nz/Web/Web/News/News-Articles/Market-updates/Oct_2024_rural_data_Dairy_and_Arable_Farms_Drive_Growth_as_Farm_Sales_Rise_Across_New_Zealand.aspx. 25 November. Accessed 22 April 2025.

- Rennie, R. (2022) Light and shade of signing on with solar. Technology. Farmers Weekly. 29 September. Available online at: https://www.farmersweekly.co.nz/technology/light-and-shade-of-signing-on-with-solar/#:~:text=Most%20projects%20aim%20to%20lease%20land%2C%20at,keen%20to%20get%20projects%20over%20the%20line. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- Quinn, R. (2023) More than 3000 injury claims from this year's storms – ACC data. RNZ. 9 April. Available online at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/487589/more-than-3000-injury-claims-from-this-year-s-storms-acc-data. Accessed 17 February 2025.

- Rouse, H., Bell, R., Lundquist, C., Blackett, P., Hicks, D. M., and King, D. N. (2017) Coastal adaptation to climate change in Aotearoa-New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 51(2), 183-222. [CrossRef]

- Sairinen, R., Barrow, C., & Karjalainen, T. P. (2010). Environmental conflict mediation and social impact assessment: Approaches for enhanced environmental governance?. Environmental impact assessment review, 30(5), 289-292. [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Sinclair, P., Qu, Z., Lam-Gordillo, O. and Bulmer, R. (submitted) Beyond Blue Carbon: Valuing Ecosystem Services of Coastal Wetlands in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research (2025).

- Snow, V., Dodd, M. and Nichols, S. (2025) Impact of waterlogging on harvestable pasture. Report to NIWA. Unpublished data, available by request.

- Statistica (2025 a) Average area of dairy farms in New Zealand from 2013 to 2024 (in hectares). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1102345/new-zealand-dairy-farm-size/#:~:text=In%20the%202024%20dairy%20season,effective%20hectares%20in%20New%20Zealand. Accessed 12 March 2025.

- Statistica (2025 b) Average number of cows per hectare in New Zealand from 2013 to 2024. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1416424/new-zealand-average-number-of-cows-per-hectare/#:~:text=In%202024%2C%20the%20average%20stocking,cows%20per%20hectare%20was%202.82. Accessed 14 February 2025.

- The Treasury (2025) Discount Rates, New Zealand Government, Wellington. Available online at: https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/public-sector-leadership/guidance/reporting-financial/discount-rates. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- Turner, E.R. (2004) Coastal wetland subsidence arising from local hydrologic manipulations. Estuaries 27, 265-272.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2012) Slow onset events. Technical paper. FCCC/ TP/2012/7. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2012/tp/07.pdf. Accessed 22 April 2025.

- Vaughan, A., Brent, A., Fitzgerald, M. and Kueppers, J. (2023) Agrivoltaics: Integrating Solar Energy Generation with Livestock Farming in Canterbury. Prepared for Our Land and Water Rural Professionals Fund 2023. June. Available online at https://ourlandandwater.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Agrivoltaics_Report_OLW-RPF23.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2025.

- Vlotman, W. F., Wong, T., and Schultz, B. (2007) Integration of drainage, water quality and flood management in rural, urban and lowland areas. Irrigation and Drainage: The journal of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage, 56(S1), S161-S177. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, T., Jain, S., Bender, J., Meyers, S. D., and Luther, M. E. (2015) Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. Nature Climate Change, 5(12), 1093-1097. [CrossRef]

- Waikato River Authority (2022) Standard costs and assumptions. Available online at: https://waikatoriver.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Standard-Costs-and-Assumptions-July-2022.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2025.

- Wang, Y., & Qian, Y. (2024). Driving factors to agriculture total factor productivity and its contribution to just energy transition. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 105, 107369. [CrossRef]

- Water New Zealand (2024) Rising sea levels could affect freshwater. Available online at: https://www.waternz.org.nz/Story?Action=View&Story_id=81#:~:text=%22This%20is%20where%20we%20in,rises%20we'll%20start%20to. Accessed 18 December 2024.

- Walker, G. (2010). Environmental justice, impact assessment and the politics of knowledge: The implications of assessing the social distribution of environmental outcomes. Environmental impact assessment review, 30(5), 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Weekes, J., and Ryan, S. (2015) Floods shut down Wellington, one dead. New Zealand Herald. 14 May. Available online at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/floods-shut-down-wellington-one-dead/U2NLENPALUNI7P3RZ7UAGJNWHQ/.

- Western Bay of Plenty District Council. (2025) “Property and Rates Search website.” Available online at: https://www.westernbay.govt.nz/property-rates-and-building/property-and-rates-search. Access 25 February 2025.

- Wetlands Trust (Undated) Restore Wetlands. Available online at: https://www.wetlandtrust.org.nz/restore-wetlands/. Accessed 21 August 2025.

- Wilby, R. L., and Keenan, R. (2012) Adapting to flood risk under climate change. Progress in Physical Geography, 36(3), 348-378. [CrossRef]

- Wunderling, N., von der Heydt, A.S., Aksenov, Y., Barker, S., Bastiaansen, R., Brovkin, V., Brunetti, M., Couplet, V., Kleinen, T., Lear, C.H., Lohmann, J., Roman-Cuesta, R.M., Sinet, S., Swingedouw, D., Winkelmann, R., Anand, P., Barichivich, J., Bathiany, S., Baudena, M., Bruun, J.T., Chiessi, C.M., Coxall, H.K., Docquier, D., Donges, J.F., Falkena, S.K.J., Klose, A.K., Obura, D., Rocha, J., Rynders, S., Steinert, N.J., Willeit, M. (2024) Climate tipping point interactions and cascades: a review. Earth Syst. Dynam. 15, 41-74. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Pearson, D., McLaren, S.J. and Horne, D. (2025) Expansion of Lifestyle Blocks in Peri-Urban New Zealand: A Review of the Implications for Environmental Management and Landscape Design. Land 14(7), 1447. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Chen, M., Yang, G., Jiang, B., and Zhang, J. (2020) Wetland ecosystem services research: A critical review. Global Ecology and Conservation, 22, e01027. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Tanner, C., Holland, P., and Qu, Z. (2024) Dynamic Economic Valuation of coastal wetland restoration: A nature-based solution for climate and biodiversity. Environmental Challenges . [CrossRef]

| Stock size | Transport costs | Grazing off-farm costs |

| 114-642 | 6,000–60,000 | 9,000–112,000 |

| Service | Reported economic estimate | Source |

| Replacement cost for flood management | NZD$16,000,000 | Department of Conservation (2007) |

| Gamebird hunting | NZD$60,000 p.a. | Department of Conservation (2007) |

| Existence/intrinsic value | NZD$55,291,671 p.a.1 | Kirkland (1988) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).