1. Introduction

April 2024 was the hottest month ever recorded in Bangladesh (Roy, 2024). Among the 19 warmest years recorded in the past one and half centuries, 18 have occurred since the beginning of the 21st century (WMO, 2022). Global climate shifts are evident in intensified cyclones, irregular precipitation, prolonged droughts, seasonal changes, and many severe weather events worldwide (IPCC, 2022). Bangladesh is situated in a vulnerable region, frequently subjected to numerous extreme events, earning global attention as the ‘epicentre of climate change’ and ‘ground zero’ for climate change. (Huq, 2001; IPCC, 2014; Iman, 2009). Bangladesh has received significant research attention for climatic adversities (see Morinière, 2009). A growing body of research explores increased soil salinity (Chen and Mueller, 2018 Adnan et al., 2020), sea level rise (Karim and Mimura, 2008; Pethick and Orford, 2013; Davis et al., 2018) or urban climate vulnerability (Alam and Rabbani, 2007; Araos et al., 2017; Ahmed et al., 2018) in Bangladesh. Visibly, the research focus is on Bangladesh’s climate change is dominantly on coastal areas. However, following a heavy pouring induced large-scale landslides in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh suddenly adding a new location to the list of hot spots. Soon after that, the National Adaptation Plan (2023–2050), identifies the CHT as a priority area for climate action. This research strives to contemplate this problem framing with a critical climate change lens (Shewly, Nadiruzzanan and Warner, 2023; Nadiruzzaman et al., 2022).

This region is the most disadvantaged and vulnerable part of Bangladesh in terms of geographical settings and almost all major development indicators (UNDP, 2009). The CHT, comprising three administrative districts, namely Rangamati, Bandarban, and Khagrachari, is unique from other parts of Bangladesh because of its topography, vegetation, biodiversity, and diverse indigenous groups and cultures (Sarkar and Mukul, 2024). Over the last four decades, this ecologically critical region has been experiencing violent conflict, structural deprivation, and non-implementation of the peace accords (see Rasul, 2007; Chakma and Chakma, 2021; Chakma, 2022; Shewly and Gerharz, 2022). Besides, over the last few decades, it has been a place of controversial land acquisition for tourism, infrastructural development, and internal displacement (Chakma and D’costa, 2013; Ahmed, 2017). Therefore, although Bangladesh serves as a key site for climate change research, the CHT has largely been overlooked. However, heavy Monsoon downpours in 2017 caused a horrific landslide mainly in the Rangamati district (Sifat et al., 2019; Abedin et al., 2020), and climate change impact in CHT came into the discussion. The impact of climate change can be much more significant for Indigenous communities living in more remote and ecologically fragile zones and relying directly on their immediate environments for subsistence agriculture (Rahman, 2014).

Against this backdrop, this paper aims to study the climate crisis in the CHT in the face of neoliberal development and environmental degradation. In doing so, this article investigates the following aspects of the CHT: (i) the prevailing climatic conditions and contemporary weather patterns in all three districts; (ii) the repercussions of these changing patterns on biodiversity, agricultural practices, livelihoods, ethnic communities, their daily lives, and social dynamics. Concurrently, (iii) it assesses the current state of climate change experiences, perceptions, awareness, and institutional frameworks, aiming to identify prospective avenues for proactive strategies in climate change adaptation and mitigation.

In doing so, this paper advances theoretical discussions by challenging climate-only narratives and emphasizing the need to analyze environmental risks within their localized socio-ecological contexts. It contributes to the growing body of scholarship advocating for context-sensitive frameworks that move beyond generalized attributions of climate change as the root cause of all environmental vulnerabilities, thereby promoting more nuanced, equitable, and regionally attuned policy responses. Climate-centric framings often obscure intersecting social, economic, and political factors that shape vulnerabilities (O’Brien & Leichenko, 2019), while historical and institutional contexts further influence risk exposure and adaptation (Nightingale et al., 2020).

Contemporary research highlights how climate policies can reinforce structural inequalities rather than mitigate them (Sultana, 2022; Pellow, 2018). Adaptation strategies rooted in climate determinism overlook governance, land tenure, and economic disparities (Baldwin & Bettini, 2017). Case studies from the Global South show that extreme weather events amplify existing socio-political inequalities rather than act as isolated crises (Taylor, 2020). This paper calls for equitable, context-sensitive policies that move beyond reductionist climate narratives.

2. Understanding Climate Change Beyond Climate Washing Approach

Climate change is an undeniable fact in the current world, which we experience in terms of changes in weather variabilities, patterns, and the magnitude and frequency of extreme events. But the changes are not identical across the globe. Therefore, global climate assessment reports, such as the one produced by IPCC, give us an idea of the average change across the globe. However, that does not proxy the climate change reality of a specific geographic location. Therefore, to assess the climate scenario of a particular geographic location, we need to analyze 30-35 years of meteorological data on that place. To understand the climate change scenario of that place, we need baseline data from an even older historical reference point. However, despite a growing number of research on climate change impacts, not much research refers to local data on climate change, instead makes an uncritical connection between the changed condition and climate change (Nadiruzzaman et al., 2022). This uncritical space of imagined interpretation of climate change makes room for climate washing. Such efforts of climate washing are problematic as they fail to comprehend the complexity of a problem and this could potentially divert attention and resources to a climate-only solution, which ends up being unsuccessful.

This paper integrates three critical lenses to assess climate change impact in the backdrop of political turmoil, neoliberal land use, and ongoing marginalisation in the CHT - (a) climate change science combining meteorological data and peoples’ experiences with climatic changes; (b) interplay of climatic and non-climatic factors that culminate hazards; and (c) construction of vulnerabilities.

First, various attributions to climate change are used in contemporary research to show variability and future changes. Researchers often use local oral history/farmers’ perception as a proxy for climate data (Wickman, 2018; Das, 2018; Guodaar et al., 2021) or time series analysis of meteorological data and compare them with local perception (Elagaib et al., 2017). IPCC climate projections (IPCC 2001, 2007) are increasingly used in research and decision-making processes. In this context, scholars have observed substantial discrepancies in slow climate variability at a regional scale and call for continued research on temporal and spatial structures of climate variability (Raucher, 2011; Laepple and Huybers, 2014; Dad et al., 2021). At regional scales, observational uncertainties do not simulate precipitation (IPCC, 2013). Besides, there is low confidence in projections of changes in monsoons (rainfall, circulation) and regional scale precipitation because there is little consensus in climate models regarding the signs of future change in monsoons (Seneviratne et al., 2012; Dastagir, 2015). Therefore, comparing the alignment of projections with the accumulating observational data is essential. We argue that attribution to climate change requires meteorological data assessment (in places where weather data is available) to comprehend local and regional scale impact precisely, which can be compared or linked with local perception of climate change.

Second, we contend that clarity between the climate change element and the underlying non-climatic condition is essential for understanding the problem better and identifying options to address the issue (Nadiruzzaman et al., 2022). In line with the growing literature challenging the naturalistic and linear understanding of insecurities (O’Keefe, Westgate, and Wisner, 1976; Sen, 1981; Watts, 1983; Wisner et al., 2004), we consider it crucial to maintain a critical exploration in understanding the broad spectrum of different interfaces. For all disasters, there are many more factors at play than climate change alone; therefore, caution is required to avoid conflation of the causes of extreme weather events and associated crises (Lahsen and Ribot, 2020; Shewly, Nadiruzzaman and Warner, 2023). To understand climate change attribution and evidence, we need to look into climate change onsets (i.e., drought, flood, etc.), underlying conditions (i.e., knowledge and skills, economic condition, cooperation, ethnic tension, conflict, etc.), potential impacts and the complexity of the systems. In a region that has experienced low-intensity conflict, it is necessary to check whether climate change drives the deterioration of order and the restoration of (in)security.

Third, the impacts of climate change are uneven across the country or regions. Also, within a similar geographical setting, it affects different groups of people differently. In most cases, poor and marginal groups are the victims of the most brutal hit of environmental onsets (Sen, 1981; Watts, 1983). Long-term sustainability of people’s livelihoods is impossible if long-term socioecological prospects are compromised, institutions and structures are updated and strengthened according to change, disruptions to other’s interests are taken care of, and ethics, politics, and notions are not institutionalised (Mikulewicz et al., 2023).

While some issues may have been previously explored, this study uniquely integrates multiple methodologies focusing on local-level dynamics in an under-researched region, offering fresh analytical insights into the nexus of climate change, environmental degradation, and development in the CHT. These reflections are crucial for guiding actionable responses to the crisis. We contend that the multicausal effects of the climate crisis are a critical and urgent issue that demands context-specific exploration rather than solely introducing entirely new perspectives. In doing so, this work will contribute to the growing body of literature that calls for addressing the complex, multifactorial nature of environmental stresses.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Study Area

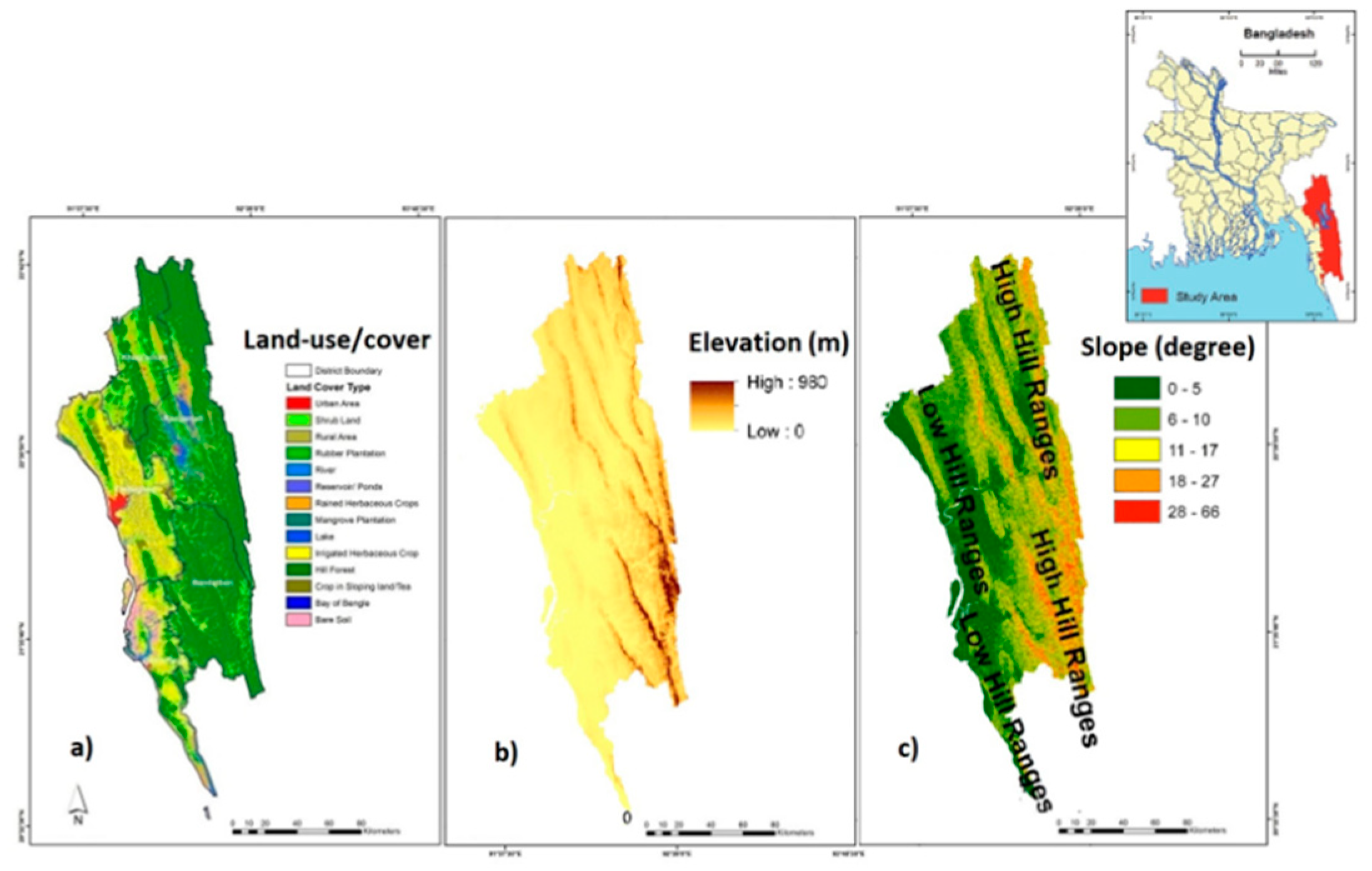

Located in the southeastern corner of Bangladesh, this region is geographically encircled by India to the north and east and Myanmar to the southeast (

Figure 1). Administratively, the CHT comprises three districts, namely Rangamati, Khagrachari, and Bandarban, characterised by a hilly terrain ranging in elevation from 450 to 1060 meters, featuring valleys and cliffs. This region encompasses 12% of the nation's land, hosting nearly 40% of its evergreen to semi-evergreen forests (Ahammad et al., 2023). A forest area of 1,105,353 hectares constitutes over 80% of the CHTs' land (BFD, 2016). Around 73% of this region is forest-friendly, 15% supports horticulture, and just 3% is fit for intensive terrace farming (Rasul, 2007).

The CHT forests are categorised into three groups: unclassified, reserved, and community forests (Ahammad et al., 2023). The unclassified forests, primarily characterised by exposed hilly terrain, encompass 64% of the total forested area, whereas reserved forests, which encompass medium and dense forest types, account for the remaining 36% and are under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD). In addition to state-owned forests, the community-owned forests, commonly called the Village Common Forests (VCF), span approximately 12,530 hectares (Chowdhury et al., 2018).

This region is inhabited by 11–13 diverse indigenous groups, constituting 55.77% of Bangladesh's total indigenous population (Uddin, 2016; BBS, 2022). Recent data reveals that the CHT's overall population is 1,842,815, with 920,217 individuals (49.94%) belonging to various indigenous groups, while 50.06% are Bengalis (BBS, 2022). Historically, this region was a distinct geopolitical entity with its own social and political system, operating independently of colonial administration. This autonomy was reinforced by the 1935 Government of India Act, designating the CHT as a 'totally excluded area,' which prohibited Bengalis from the adjacent plain districts from purchasing land or establishing permanent residence in the region (Chakma, 2022).

The post-colonial states of Pakistan and, subsequently, Bangladesh sought control over the CHT's indigenous territories through military, bureaucratic, political, demographic, and economic measures, leading to low-intensity conflicts and extensive displacement (Chakma, 2022; Shewly and Gerharz, 2022). For example, the construction of the Kaptai dam in the 1960s submerged 40% of the region's arable land, displacing numerous indigenous families, many of whom migrated to neighbouring India and Burma. Despite a peace agreement in 1997, three critical political factors—the government's transmigration policy, ongoing militarisation, and non-implementation of the CHT Accord—have caused political instability among the indigenous communities (Chakma, 2022). Past and current development projects, alongside increasing land grabbing in the name of expansion of the tourism industry, have displaced local populations and adversely impacted the local ecosystem (CHT Commission, 1991; Chakma, 2023).

3.2. Field Techniques

This paper is primarily based on questionnaire surveys, focus group discussions, interviews, observations, and casual discussions to gain insight into the local population's daily challenges. Data enumerators were from local ethnic groups, possessing in-depth knowledge of local cultural sensitivities, extensive social research experience, and fluency in local languages and dialects. In terms of data collection, the study aimed to encompass a diverse representation of ethnic groups (69% Chakma, 12% Mroo, 11% Bengali, 8% Marma) and various livelihoods (including agriculture, labour, livestock, poultry, fruit gardening, non-agricultural work, and more). The research also aimed to achieve extensive geographical coverage and engage diverse stakeholders, including local elites, elected representatives, government officials, and development agencies.

Taking into account a 5% margin of error, a 95% confidence level, and a 50% response distribution, the calculated sample size for a population of 1,586,141 is 384 (Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), 2011). We then conducted surveys with 400 households to gather people's perspectives, knowledge, and experiences regarding climate change in their local contexts. In the survey, 68% of the informants were male and 32% female. The majority (49%) of respondents were between 28 and 42 years old, while 28% were aged 43 to 57. We conducted 21 interviews with personnel from public institutions and development organizations, held 6 FGDs involving 48 participants (approximately 6-8 members per group), and carried out 18 key informant interviews with community members. FGDs explored local views on the causes of changes, community practices, values, and beliefs. Interviews focused on agricultural practices, biodiversity, changes in employment and livelihoods, vulnerability, and coping strategies.

In developing the questionnaire, interview protocols, and FGD schedules, we engaged in a comprehensive review of existing literature alongside a critical reflection on our extensive experience in the development sector, spanning over a decade. Our methodological framework underwent scrutiny and approval by an independent review body, after which we conducted a pilot field test wherein data enumerators assumed primary roles under the direct observation of the research lead. This initial stage allowed all team members to observe interview techniques employed by others, document their observations, and subsequently discuss insights within the group. Based on feedback from this field test, the data collection instruments were refined for enhanced rigor and applicability. Random spot-checks were implemented during the data collection phase to ensure procedural consistency. Furthermore, daily debriefing sessions facilitated a collaborative environment where enumerators discussed encountered challenges, posed inquiries, and collectively devised standardized solutions. Upon completion of the data collection process, a comprehensive consistency check was conducted on each questionnaire to ensure data integrity.

3.3. Data Analysis

Crop yields and severe weather events data were compared with climatic data sourced from satellite records and information provided by the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD). Specifically, the study utilized the past 30 years' daily data for temperature, sunlight duration, humidity, and wind pressure from the Rangamati district, acquired from the BMD. Since the CHT region has one weather station, the data from this station may not accurately represent the entire area. To supplement this, weather data for Bandarban and Khagrachari districts was gathered from the NASA TRMM_3B42_daily satellite dataset (NASA Goddard Earth Sciences, Data and Information Services Center, 2019). However, satellite data is less reliable for capturing temperature variations in regions with diverse topography. As a result, the climate forecasts and patterns presented in this study heavily rely on rainfall data. This research greatly benefits from the insights gained from people's real-life experiences to supplement information regarding temperature and other meteorological variables. It draws upon life-history interviews conducted with elderly individuals.

The analysis of climate change trends in this region involved two key steps: (i) Time series plots, correlograms, and unit tests (like the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test) were applied to evaluate the stationarity of seasonal data for rainfall, temperature, sunshine hours, humidity, and wind pressure in each district. (ii) Trend analysis was carried out using linear, quadratic, and exponential models, with model selection guided by Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), for the stationary climatic variables. Questionnaire survey data was coded, edited for consistency, computerized, and then collated, synthesized, and analyzed. Data was categorized by gender, age, location, learning background, and other social, economic, and cultural categories. Quantitative data were recorded numerically, while some qualitative data were converted using semantic differential or Likert scales. Informants' qualitative opinions obtained from semi-structured interviews, FGDs, and informal queries were transcribed, coded, and analyzed.

4. Results

4.1. Climate Change Projection for CHT

Bangladesh experiences four distinct seasons: winter (December–February), pre-monsoon (March-May), monsoon (June–September), and post-monsoon (October–November). Analyzing data on intense precipitation between 1988-2017 reveals a decrease in the frequency of precipitation events (≥89 mm) in all three districts. The highest documented rainfall occurred on 12 June 2017 in Rangamati (343mm/24 hours), on 9 June 2018 in Bandarban (170mm/24 hours), and on 12 June 2018 in Khagrachari (148mm/24 hours).

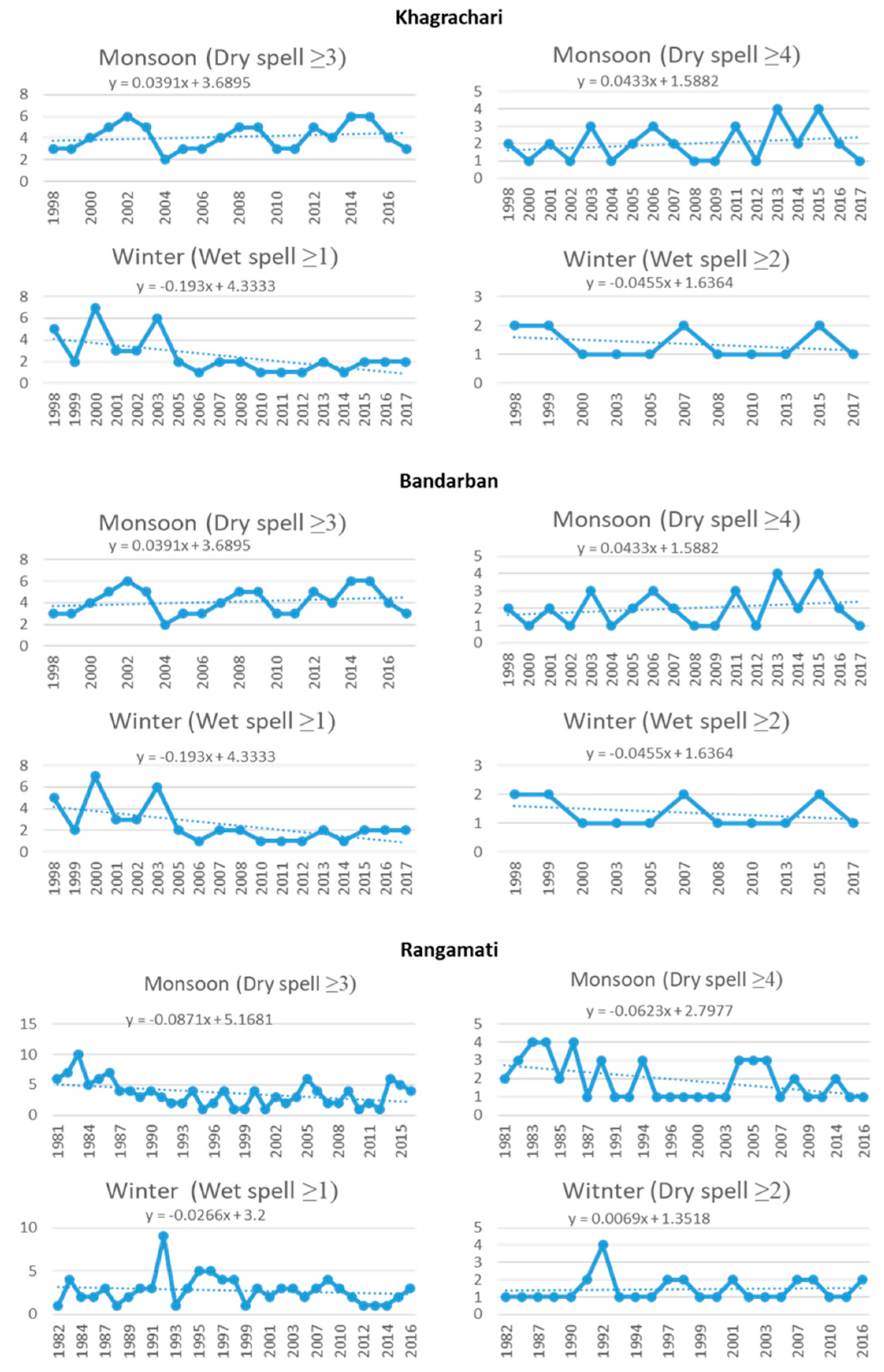

In Bandarban, analysis of monsoon data (dry spells ≥3 and ≥4) demonstrates a notable trend of rising temperatures during the 1998–2017 period, signifying a rapid increase in warmth (

Figure 2). Specifically, in the monsoon season, the frequency of dry spells lasting over three days reduced in June, July, and September. However, a rise was noted in August, with recorded data from 2001 to 2017. The dry spell continuing over four days during the monsoon season denoted a consistent annual trend in June and September (2002–2016). However, the trajectory displayed an annual increase in July and August (2003–2015). The yearly decrease was observed in winter for more than 1 and 2 days of wet spells. In contrast, Khagrachari's monsoon data (dry spells ≥3) shows a pattern of declining temperatures from 1998 to 2017, indicating that the dry periods lasted less than three days. This research also found that during the monsoon season (June–September), dry spells lasting three or more days either declined or stayed unchanged each year. Monsoon dry spells ≥4 days demonstrated a yearly declining pattern in June and July. In August, the frequency of dry spells rose each year, while in September, the pattern remained unchanged. A yearly decline was recorded in winter (December–February) for wet spells of at least one day (≥1), while wet spells lasting two or more days exhibited a rising trend. Monsoon data in Rangamati (dry spells ≥3 and ≥4) shows a declining pattern in temperature from 1981 to 2016, meaning the dry periods lasted fewer than three days. This research also found that during monsoon (June–September), the dry spell of ≥3 days decreased each year except June. Monsoon dry spells of four or more days indicated a yearly rising pattern in June and July. In August, the dry spell stayed constant from 1983 to 2004. In September, the four-day dry spell decreased each year. During winter (December–February), a yearly decline was noted for wet spells lasting at least one day, while wet spells of two or more days showed an annual increase. In December and January, wet spells lasting at least one day increased each year, whereas, in February, there was no annual increase in wet spells.

4.2. Local Perceptions of Environmental Change in CHT

In the household survey and focus groups, people were asked about the local weather and surrounding environment in connection to their life and livelihoods, if they had sensed any change in the weather pattern and local environment, if ‘yes’, what triggers that change, how that affects their everyday life and what do they do in response. There was a unanimous response about spotting changes. Over half of the informants responded that they knew about climate change (male 67% and female 33%). Almost all respondents (around 99%) noted noticeable shifts in the weather system in recent years. They perceived climate change based on variations in temperature, rainfall, and weather patterns. Unanimously they attributed these changes to human activities, pollution, and broader environmental transformations. (

Table 1). One of the key changes they highlighted is a general increase in temperature across all seasons, significantly impacting their farming practices. About half of the informants across field sites have recognized feel-like temperature as the key indicator of environmental change.

Deforestation was identified by 90-100% of informants across all study sites as the primary driver of environmental change. In certain areas of Rangamati and Khagrachari, where industrialization's effects are noticeable, this was also highlighted as a contributing factor. Respondents described their experiences of these changes, emphasizing increased heat and water shortages, especially during the dry season. Interviews and conversations with residents in all field sites revealed that winters have become shorter in recent years, meteorological patterns are shifting across seasons, temperatures are rising, and thunderstorms are occurring more frequently than before.

4.3. Impact of Changed Rainfall and Temperature on Agriculture, Poultry and Livestock

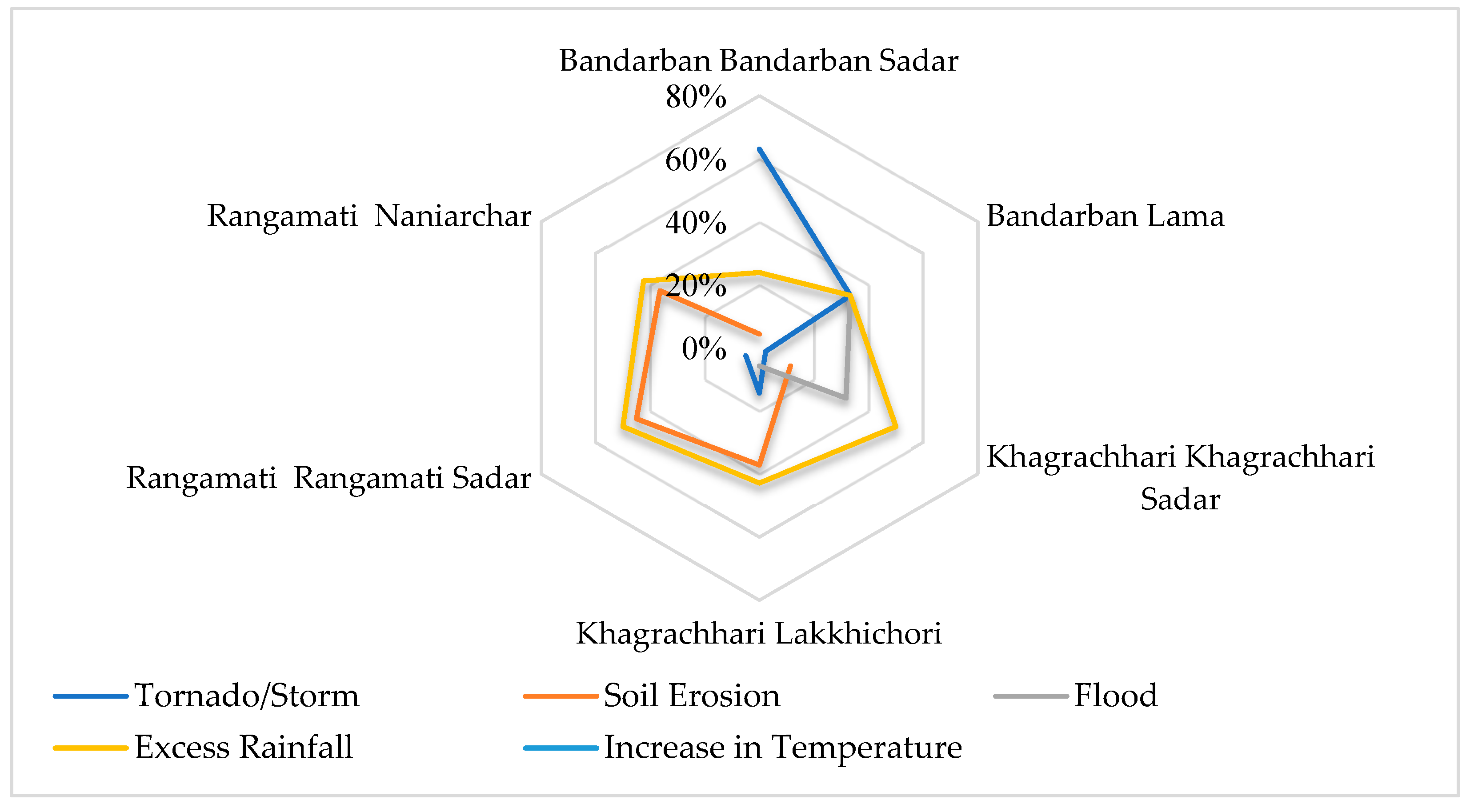

The primary crops in the CHT include rice, ginger, turmeric, mango, and jackfruit, along with secondary crops like pumpkin, cucumber, chilli, pineapple, banana, and pomelo. (Also see, Ahammed,2019). Survey data shows that environmental hazards like storms, soil erosion, landslides, floods, excessive rainfall, and rising temperatures significantly impact agriculture (

Figure 3). However, over three-quarters of respondents were unaware of upcoming disasters. Additionally, 85% of informants reported a sharp decline in crop prices due to environmental stresses, with the most severe effects in Khagrachari Sadar (99%) and the least in Rangamati Sadar (49%), directly affecting their income. Beyond income loss, changing rainfall patterns have increased irrigation costs and worsened water scarcity, particularly during crop seasons. Local farmers noted that even slight fluctuations in temperature and rainfall affect agricultural yields and the local economy. In Rangamati, farmers are increasingly forced to buy climate-resilient seeds and fertilizers at higher prices due to land degradation, raising production costs. Therefore, reliance on hybrid seeds, pesticides, and chemical fertilizers has grown, often contaminating water sources and harming aquatic ecosystems.

4.4. Increased Environmental Stresses and Water Scarcity

Of the informants, 57% feel that water sources have shifted over the past decade. They attribute this change primarily to two factors: 47% point to the increased use of tube wells for water collection, while 37% cite the reduction in forested areas. Additional factors mentioned during interviews and discussions include rock extraction, rising temperatures, and intense rainfall. Excessive water extraction from the same tube wells has led to a drop in water levels. Among the informants, 40% depend on shallow tube wells for drinking water, while 24% use deep tube wells and 18% rely on springs. Smaller water sources, including ponds, rivers, rainwater harvesting, waterfalls, and supplied water, are also used. The majority of water sources (85%) are located within 0-1 km, while the remaining 15% are situated between 1-2 km away. Half of the informants link deforestation to water scarcity, while the rest mention factors like rising temperatures (29%), falling water tables (14%), and rock extraction (7%) as contributing causes.

Our survey data shows that more than half of the informants faced water shortages during extreme events, with Bandarban Sadar and Lakhhichori being particularly affected. Water scarcity intensifies during environmental stresses, especially flash floods, which are the main contributors to shortages, along with landslides and cyclones. Flash floods were especially severe in Lama, affecting 89% of the population. Cyclones and landslides had a major impact in Khagrachari Sadar (44%) and Nani-archar (58%). Over half of the informants (55%) reported having to travel to nearby villages to collect water in response to the shortage. To cope, they took measures like digging new springs and boiling water for drinking. In Khagrachari Sadar, 84% of individuals are forced to fetch water from surrounding villages, with women being the primary individuals involved in this task.

4.5. Changes in Biodiversity

The CHT is renowned for its magnificent biodiversity, distinctive landscape, vast forest reserves, rich cultural heritage, and stunning natural beauty. Discussions during interviews and household surveys consistently emphasised the following cyclic impacts.

For example, an anonymous Headman highlights,

‘Over the past several decades, the population in the CHT has significantly increased, resulting in expanded and intensified land use patterns in the hill forests, accompanied by increased deforestation and commercial forestation activities. Consequently, the overall ecosystem and biodiversity in the CHT have been significantly affected.’

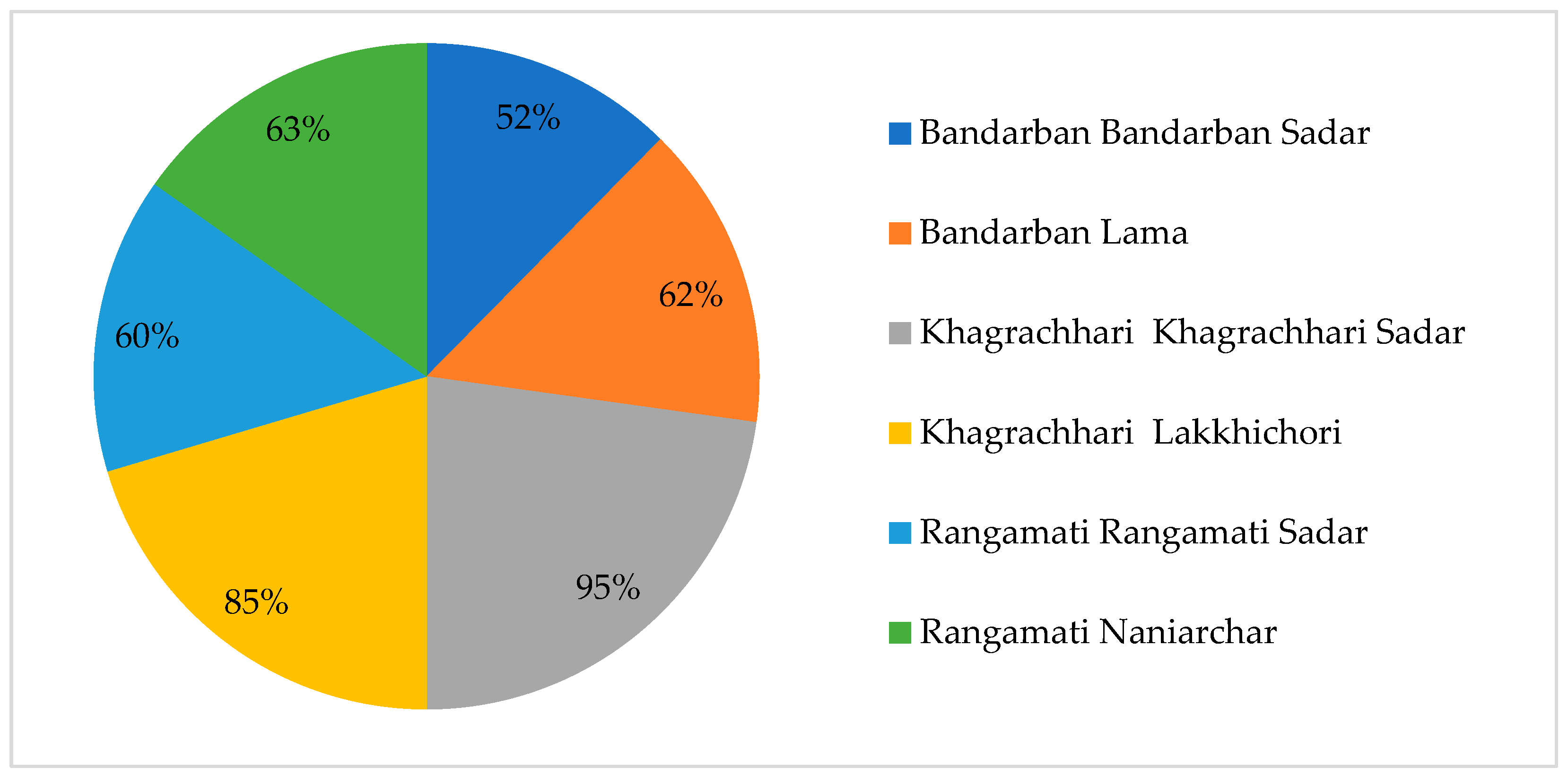

Informants were asked about their views on local biodiversity loss, and their overwhelming responses pointed fingers at deforestation (

Figure 4).

Plant species such as Garjan, Chapalish, Jarul, and Koroi are experiencing severe decline in Khagrachari Sadar and Lakkhichori. In Rangamati Sadar and Naniarchar, Garjan and Chapalish are also facing rapid reductions. Local communities have identified Garjan as the most at-risk species in the CHT. However, these observations tend to focus on the more prominent species seen throughout the community's lifetime, often overlooking smaller shrubs, vines, and other lesser-known plants that, although not immediately noticeable, play a vital environmental role and are gradually disappearing.

The disappearance of the species mentioned above indicates a loss for those dependent on them for sustenance and shelter within their canopy. Informants (78%) also acknowledge the adverse impact on wildlife in the CHT. Species documented during interviews include fox, bear, and deer in Bandarban Sadar and Lama; bear, deer, and wild pig in Khagrachari Sadar; deer and Moorhen in Lakkhichori; fox, deer, and monkey in Rangamati Sadar; and fox, deer, and pig in Naniarchar.

4.6. Impact on Income, Livelihood and Economy

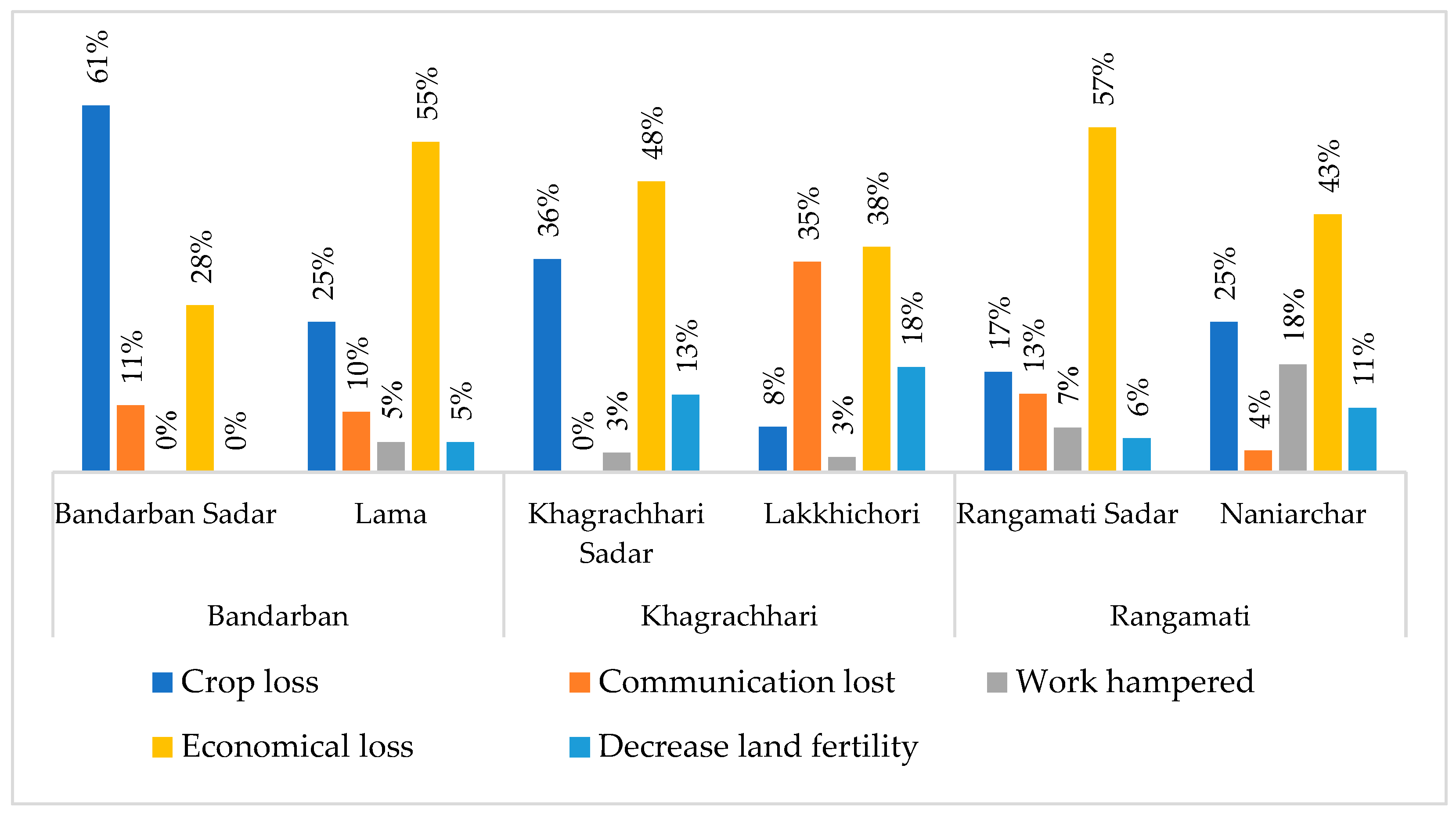

Extreme environmental events significantly impact infrastructure, particularly in the Khagrachari region, where roads, culverts, and bridges suffer extensive harm. These disruptions result in agricultural losses, interrupted communication, halted economic activities, and declining soil fertility, all of which pose serious challenges to local communities. These factors have a considerable impact on people's livelihoods, with only 26% of respondents feeling that their current means of living can sufficiently adjust to these changes. Moreover, 71% of respondents recognized that extreme events harm local infrastructure, including roads, culverts, and bridges. This damage has led to business losses varying between 22% and 94% across different regions, with the most significant losses seen in Bandarban and Khagrachari districts. Additionally, 15% of those surveyed indicated a desire to switch professions due to increasing environmental pressures, with 76% of them opting for physically demanding work, whether in agriculture or other industries, regardless of gender (

Figure 5).

Destruction of local infrastructure disrupts transportation and agricultural trade, resulting in reduced earnings. This infrastructure damage primarily led to business declines in Khagrachari and limited access to essential services like healthcare and education. The most significant challenge was the decline in crop yields and widespread livestock fatalities throughout the area.

5. Discussion

5.1. Understanding Climate Change in the Context of CHT

Meteorological data indicates a decrease in the rate of heavy precipitation(>89mm) throughout the region, which has been detailed in the results section. The duration of monsoon dry spells (>3 and >4 consecutive full dry days) is increasing in Bandarban, while marginally declining in Rangamati and Khagrachari. The shift suggests that Bandarban might face more dry monsoons, impacting crop production, vegetation, and water sources. However, Rangamati and Khagrachari might experience less change during the monsoon. Regarding wet spells (>1 day) in winter, Bandarban shows a decrease, while Rangamati and Khagrachari exhibit an increase. While integrating meteorological data with local experiences does not definitively confirm a direct connection between climate change and its immediate adverse effects on the well-being and economic activities of CHT residents, it also does not eliminate the possibility of future climate-driven occurrences. In particular, extreme hydro-climatic events such as intense precipitation and severe storms remain a concern. Emerging climate events such as landslides, floods, and hurricanes in the CHT are closely linked to underlying factors, including extensive infrastructure development, changes in land use and cover, and the degradation of forests and biodiversity. These combined factors have significantly affected the overall environmental conditions, aligning with the weather variations and other adverse climate impacts experienced by CHT residents over time.

CHT has just recently been in Bangladesh’s national disaster hotspots. Lately, flash floods and landslides have dominated disaster reports. On June 13, 2017, continuous rainfall and massive landslides ravaged the hill districts of Rangamati, Bandarban, and Khagrachari, claiming 152 lives (UN RC, 2017). Hundreds sustained injuries, and approximately 15,000 families were severely impacted, losing the majority of their possessions. Landslides devastated farmland, ruined harvests, and severely damaged infrastructure, including roads and power systems. This recent event has been consistently echoed in the accounts of the informants. The same amount of pouring in twenty years ago and now would have very different effects due to significant alterations in the CHT's landscape and land utilization over time. For instance, looking at the data for the heaviest rainfall, Rangamati witnessed similarly heavy rainfall in 1998, 1999, 2004, and 2017, with each event surpassing 300 mm. However, there has been a significant increase in landslides in recent years. Geology, land use, and land cover change were categorical variables for the 2017 landslide, which was triggered by excessive rain (Sifat et al., 2019; Abedin et al., 2020). Abedin et al. (2020) reveal two important causal relations in their study; the largest landslide occurred in a rubber garden where natural forests were cleared, planting rubber trees. Landslide occurrence had an inverse relationship with distance to the road network; most of the landslides (96.29%) occurred within a 2 km distance to the road. These scientific research findings also match the local voices in our study. Sifat et al. (2019) warn that the large number of landslides has made the slope unstable, thereby increasing the possibility of slope failure in the area more than before, in which Rangamati Sadar is the most high-risk zone.

Deforestation was a central cause for all measures in the research participants’ accounts. The process of forest degradation began during the British colonial period and has accelerated in recent times by the privatisation of forest land for the promotion of sedentary agriculture, horticulture, and rubber plantation; the construction of a hydraulic dam on the Karnafuli River; the settlement of lowland people; and the constant conflict between indigenous people and the Forest Department (for a historical account, see Rasul, 2007). Despite governmental restrictions on access to reserved forests, the region continues to experience a concerning rate of forest loss. For instance, between 2000 and 2015, the extent of forest cover in the CHT diminished by 8% (Government of Bangladesh, 2020: p.64). Furthermore, government-led restoration initiatives have shown limited concern for ecological functionality, biodiversity preservation, and environmental sustainability (Ahammad et al., 2023). The annual forest destruction rate in Bandarban Sadar Upazila is 17.92% (Mamnun and Hossen, 2020).

This narrative of land transformation, deforestation, soil erosion, intense rainfall, flash floods, and landslides is interconnected. An all-encompassing perspective is required to grasp the interrelation of development, hazards and climate variability. Therefore, climate change should not be studied from a narrow perspective, but instead from an all-encompassing viewpoint that includes the interrelations among various factors driving environmental change. While flash floods and landslides in the CHTs are mostly related to man-made soil erosion and deforestation, the frequency and severity of such disasters are likely to increase sharply because of climate change induced precipitation increases (Gunter, Rahman, and Rahman, 2008).

5.2. Complex Governance and Power Dynamics in the CHT

The CHT has a complex administrative and governance structure, characterized by overlapping de jure and de facto control. The region has been militarized for over forty years, despite the 1997 peace treaty aimed at ending this military presence. Military forces maintain both temporary and permanent camps, as well as checkpoints, exerting de facto power in the region—often seen not as a national security issue, but as state-sponsored marginalization of indigenous communities. The region also has a ministry focused on CHT welfare, while local governance is managed by district councils, with Chairmen and councillors elected through general voting. Indigenous communities continue to follow their traditional system, where circle chief (often called King) collects annual taxes, celebrated through local festivals. At the grassroots level, headmen and karbaris work more local levels. Additionally, various armed factions with various demands including autonomy remain active in some parts in the region, particularly in the region’s remote forests. Relations between military forces and indigenous communities remain strained, with differing narratives surrounding the causes of the tension and military actions in the region. All of these factors create a complex governance environment, where power dynamics vary across the region. Effective engagements on environmental and climate change issues require a nuanced understanding of local contexts, careful management of intergroup relations, and long-term, community-based involvement navigating through various official and unofficial governance hurdles.

6. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Future Research Direction

This research reveals that environmental and livelihood vulnerabilities in the CHT are not solely attributable to climate change but are exacerbated by interlocking socio-ecological factors, including deforestation, infrastructure expansion, and land-use shifts. The lack of a direct causal link between climate change and immediate livelihood impacts highlights environmental stressors' complex, multifactorial nature, where climate functions as one component within broader systemic pressures. The observed intensification of water scarcity, growing dependency on climate-resilient seeds, and agricultural strain illustrate an "ecological entanglement" where industrialization and resource over-extraction amplify the effects of hydro-climatic events, posing cumulative, forward-looking risks. By integrating meteorological data with local knowledge, this study provides a nuanced understanding of climate variability in the region and its cascading effects on livelihoods, biodiversity, and social dynamics. In doing so, it challenges dominant climate-centric narratives that often obscure the role of historical and institutional factors in shaping vulnerability (O’Brien & Leichenko, 2019; Nightingale et al., 2020).

This paper highlights how climate-induced hazards in the CHT are not solely driven by environmental factors but are deeply embedded within broader socio-political and economic processes, including deforestation, land-use change, governance structures, and the marginalization of Indigenous communities. The findings emphasize that adaptation strategies must be context-sensitive, acknowledging the interplay between climate-induced hazards and anthropogenic transformations in the landscape. This aligns with the growing body of research advocating for holistic, multi-dimensional approaches to climate resilience, particularly in regions with overlapping vulnerabilities (Sultana, 2022; Baldwin & Bettini, 2017).

For CHT, this paper recommends a comprehensive approach to climate change awareness, starting with an objective diagnosis of environmental issues and advocating for inclusive, just solutions. It emphasizes the importance of long-term capacity-building and awareness campaigns that promote internal communication and cross-learning among stakeholders. This model can foster collaboration between sectors, such as agriculture and meteorology, by increasing climate awareness and information demand. Climate change considerations must also be integrated into various sectors, including agriculture, infrastructure, health, and education, ensuring alignment with global development goals and addressing gaps identified through past disasters. Additionally, the paper highlights the need for a multi-horizon approach to Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), incorporating both short-term actions (such as awareness and evacuation planning) and medium-to-long-term strategies (such as constructing shelters and improving land-use planning). Environmental protection in the CHT region, including activities like afforestation and biodiversity preservation, must be prioritized, with local communities playing an active role in conservation efforts. Given the unique context of the CHT, characterized by conflicts and militarization, a holistic focus on livelihood security and infrastructure development is also crucial for long-term climate resilience.

From a theoretical perspective, this research contributes to the broader literature on climate change and vulnerability by demonstrating the limitations of reductionist approaches that attribute environmental crises solely to climatic changes. Instead, it advances a more integrated perspective, drawing from political ecology and critical disaster studies, to reveal how climate change intersects with governance, land tenure, and socio-economic inequalities (Pellow, 2018; Lahsen & Ribot, 2020). This study reinforces calls for equitable, regionally attuned policy responses that move beyond generalized attributions of climate change as the singular cause of environmental stress (Taylor, 2020; Shewly et al, 2023). Besides, this paper enhances climate vulnerability assessment methodologies by integrating meteorological data with local knowledge, distinguishing between climate and non-climate factors to inform effective adaptation strategies.

Finally, this research provides an essential foundation for future studies on climate change in the CHT by illustrating how environmental risks must be understood in their localized socio-ecological contexts. It calls for sustained interdisciplinary research that bridges climate science with political and socio-economic analyses to formulate more just and effective adaptation strategies. By doing so, it contributes to the broader academic discourse on climate justice, governance, and resilience in the Global South.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

End Note

The term ‘indigenous’ refers to the population covered by the United Nations' definition of ‘indigenous people’. The term has a political connotation for material reasons. The government of Bangladesh uses an umbrella term, ‘ethnic minorities,’ which allows it to neoliberalise indigenous peoples’ land without worrying much about any international legal remedy.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to all the informants for being so open and kind to us. We appreciate comments, reflections, and feedback from many experts and development practitioners at different knowledge-sharing events. We also thank the Manusher Jonno Foundation for commissioning this study and supporting us with logistics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abedin, J.; Rabby, Y.W.; Hasan, I. Characteristics, causes, and consequences of June 13, 2017, landslides in Rangamati District Bangladesh’. Geoenviron Disasters. 2020, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.S.G.; Abdullah, A.Y.M.; Dewan, A.; Hall, J.W. Changing land use and flood hazard effects on poverty in coastal Bangladesh. Land Use Policy. 2020, 99, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.H. Tourism and state violence in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. In: M.T. Khan and M. S. Rahman (eds) Neoliberal Development in Bangladesh: People on the Margins. The University Press Limited, Dhaka, 2017, pp. 315–342.

- Ahmed, F.; Moors, E.; Khan, M.S.A.; Warner, J.; Terwisscha van Scheltinga, C. Tipping points in adaptation to urban flooding under climate change and urban growth: The case of the Dhaka megacity. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, R.; Hossain, M.K.; Sobhan, I.; Hasan, R.; Biswas, S.R.; Mukul, S.A. Social-ecological and institutional factors affecting forest and landscape restoration in the Chittagong Hill tracts of Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Rabbani, M.G. Vulnerabilities and responses to climate change for Dhaka. Environment and Urbanization 2007, 19, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araos, M.; Ford, J.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Biesbroek, R.; Moser, S. Climate change adaptation planning for Global South megacities: the case of Dhaka. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 2017, 19, 682–696. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). Population and housing census: Preliminary report. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Dhaka, 2022. Available online at: http://www.bbs.gov.bd/site/page/b588b454-0f88-4679-bf20-90e06dc1d10b/-. (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD). Draft National Forest Policy. Bangladesh Forest Department, Dhaka, 2016. Available online at: http://www.bforest.gov.bd/site/page/ffa2ec14-acdf-467b-9111-b677a857a9b9Policy-.7. (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Chakma, A. Does political security matter? A study on the life satisfaction of indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Journal of Asian and African Studies 2022, 59, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakma, K.; D'Costa, B. The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT): Diminishing violence or violent peace? In: A. Edward, R. Jeffrey, and A. J. Regan (eds) Diminishing Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific: Why Some Subside and Others Don't. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon and New York, 2013, pp. 137–149.

- Chakma, P.; Chakma, B. Bangladesh in the indigenous world 2021. In: D. Mamo (eds) The indigenous world 2021. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Copenhagen, 2021.

- Chakma, P. Flooding in CHT: When development gives little but takes all. The Daily Star, 2023. Available online at: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/views/news/when-development-gives-little-and-takes-all-3401221 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Chen, J.; Mueller, V. Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Zahra, F.T.; Rahman, M.F.; Islam, K. Village common forest management in Komolchori, Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: An example of community-based natural resources management. Small-scale Forestry 2018, 17, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dad, J.M.; Muslim, M.; Rashid, I.; Reshi, Z.A. Time series analysis of climate variability and trends in Kashmir Himalaya. Ecological Indicators, 2021, 126, 107690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.V. People’s history of climate change. History Compass 2018, 16, e12497. [Google Scholar]

- Dastagir, M.R. Modelling recent climate change induced extreme events in Bangladesh: A review. Weather and Climate Extremes 2015, 7, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.F.; Bhattachan, A.; D’Odorico, P.; Suweis, S. A universal model for predicting human migration under climate change: examining future sea level rise in Bangladesh. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 064030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagib, N.A.; Musa, A.A.; Sulieman, H. M. Socio-hydrological framework of farmer-drought feedback: Darfur as a case study. In O. Abdalla, A. Kacimov, M. Chen, A. Al-Maktoumi, T. Al-Hosni, and I Clark (eds) Water Resources in Arid Areas: The Way Forward. Springer, Cham, 2017.

- Government of Bangladesh (GoB). Tree and forest resources of Bangladesh: Report on the Bangladesh forest inventory. Bangladesh Forest Department, Dhaka, 2020. Available online at: http://bfis.bforest.gov.bd/bfi/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/BFI_report_final_8–12–20_2.pdf. (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Gunter, G.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, A.F. How Vulnerable are Bangladesh's Indigenous People to Climate Change? Bangladesh Development Research Center (BDRC), Dhaka, 2008. Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1126441 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Guodaar, L.; Bardsley, D.K.; Suh, J. Integrating local perceptions with scientific evidence to understand climate change variability in northern Ghana: a mixed-methods approach. Applied Geography 2021, 130, 102440. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.S.; Sarmin, N.S.; Miah, M.G. Assessment of scenario-based land use changes in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. Environmental Development 2020, 34, 100463. [Google Scholar]

- Huq, S. Climate change and Bangladesh. Science 2001, 294, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, M. Where warming hits hard. Nature Climate Change 2009, 3, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014, pp. 1327–1370.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. In: T.F. Stocker et al. (eds) Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. In: S Solomon et al. (eds) Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2001: The scientific basis. In: J T Houghton et al. (eds) Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001.

- Karim, M.F.; Mimura, N. Impacts of climate change and sea-level rise on cyclonic storm surge floods in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change 2008, 18, 490–500. [Google Scholar]

- Lahsen, M.; Ribot, J. Politics of attributing extreme events and disasters to climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2022, 13, e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laepple, T.; Huybers, P. Ocean surface temperature variability: Large model–data differences at decadal and longer periods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 16682–16687. [Google Scholar]

- Mamnun, M.; Hossen, S. Spatio-temporal analysis of land cover changes in the evergreen and semi-evergreen rainforests: A case study in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. International Journal of Forestry, Ecology and Environment 2020, 2, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulewicz, M.; Crawford, N.; Caretta, M.; Sultana, F. Intersectionality & climate Justice: A call for Synergy in scholarship and practice. Environmental Politics 2023, 32, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Morinière, L.C.E. Tracing the footprint of ‘environmental migrants’ through 50 years of literature. In: A. Oliver-Smith & X. Shen (eds) Linking Environmental Change, Migration & Social Vulnerability. United Nations University, 2009, pp. 22–29.

- Nadiruzzaman, M.; Scheffran, J.; Shewly, H.J.; Kley, S. Conflict-sensitive climate change adaptation: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, P.; Westgate, K.; Wisner, B. Taking the natureness out of natural disaster. Nature 1976, 260, 566–567. [Google Scholar]

- Pethick, J.; Orford, J.D. The rapid rise in effective sea-level in southwest Bangladesh: Its causes and contemporary rates. Global and Planetary Change 2013, 111, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A. Bangladesh climate vulnerability: floods and cyclones. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Ethiopia, 2014.

- Rasul, G. Political ecology of the degradation of forest commons in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. Environmental Conservation 2007, 34, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Raucher, R.S. The future of research on climate change impacts on water: a workshop focused on adaption strategies and information needs. Water Research Foundation 2011. Available online at: http://www.waterrf.org/projectsreports/publicreportlibrary/4340.pdf (accessed on 07 March 2024).

- Roy, P. High Temperature Days: Barring miracle, record of 76yrs breaks today. The Daily Star, 2024. Available online at: https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/high-temperature-days-barring-miracle-record-76yrs-breaks-today-3595481. (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Sarkar, O.T.; Mukul, S.A. Challenges and Institutional Barriers to Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. Land 2024, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1981.

- Seneviratne, S.; et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In; C.B., Field et al. (eds) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012, pp. 109-230.

- Shewly, H. J.; Gerharz, E. Identity, conflict, and social movement activism in nation-building politics in Bangladesh. ASIEN 2022, 163/164, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewly, H.J.; Nadiruzzaman, M.; Warner, J. Causal connections between climate change and disaster: the politics of ‘victimhood ’framing and blaming. International Development Planning Review 2023, 45, 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Sifat, S.F.; Mahmud, T.; Tarin, M.A.; Haque, D.M.E. 2019. Event-based landslide susceptibility mapping using weights of evidence (WoE) and modified frequency ratio (MFR) model: a case study of Rangamati district in Bangladesh. Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes 2019, 4, 222–235. [Google Scholar]

- The CHT Commission. Life is not ours: Land and human rights in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. The Report of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission, 19 May.

- UNDP. Socio-economic baseline survey of Chittagong Hill Tracts. United Nations Development Programme, Dhaka, 2009. Available online at: https://www.hdrc-bd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/6.-Socio-economic-Baseline-Survey-of-Chittagong-Hill-Tracts.pdf. (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Uddin, A. Dynamics of strategies for survival of the indigenous people in Southeastern Bangladesh. Ethnopolitics 2016, 15, 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- UN RC. Bangladesh: HCTT response plan (June December 2017) – Bangladesh’. ReliefWeb, 2017. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/bangla (last accessed on 07 March 2023).

- Watts, M. Silent Violence: Food, famine and peasantry in Northern Nigeria. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1983.

- Wickman, T. Narrating indigenous histories of climate change in the Americas and Pacific. In: S. White, C. Pfister, and F. Mauelshagen. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2018.

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. Routledge, London, 2004.

- WMO. Eight warmest years on record witness upsurge in climate change impacts. World Meteorological Organization, 2022. Available online at: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/eight-warmest-years-record-witness-upsurge-climate-change-impacts (last accessed on ).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).