1. Introduction

The etiopathogenesis of human autoimmunity is not fully elucidated. Several mechanisms are still under investigation underlying the occurrence of adaptive and innate immune responses [

1]. The adaptive immune system consists for a large part of T-cells, which recognize specific epitopes derived from antigens through their T-cell receptor (TCR). The recombination of key TCR DNA coding segments allows for an essentially endless repertoire of potential antigen-binding TCRs [

2,

3].

The AutoImmune REgulator gene (

AIRE) encodes for a non-classical transcriptional factor,

i.e. a facilitator/modulator that is expressed in medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTEC) where it plays a pivotal role in the process of negative selection occurring in the perinatal age [

4]. As regard mature thymocytes are screened for autoreactivity and, in case high avidity recognition of self-antigen occurs, they are clonally eliminated [

5]. Nevertheless, some self-reactive T-cells can escape from the thymus, go to the peripheral blood and get activated during the lifetime, generating autoimmune diseases under special circumstances of genetic/environmental interaction. Indeed, in the human monogenic disorder Autoimmune PolyEndocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal Dystrophy syndrome (APECED, Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1 (APS1)) caused by AIRE deficiency or loss of function

AIRE mutations, T-cell autoreactivity is responsible for dysfunction of several endocrine glands and non-endocrine tissues. The clinical diagnosis occurs in the presence of at least two out of three relevant manifestations

i.e. hypoparathyroidism, adrenocortical insufficiency and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis [

4].

It is generally recognized that the mechanism of central tolerance provided by AIRE expressing mTECs is not the sole in the regulation of the adaptive immune response since peripheral tolerance mechanisms exist in the periphery. In the peripheral lymphoid organs, the deletion or induction of functional unresponsiveness in autoreactive T-cells requires interaction with an antigen-presenting cell (APC) presenting cognate antigen. Peripheral tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) can induce anergy or peripheral clonal deletion of T-cells by presenting an antigen without expressing costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 necessary for the full activation of T lymphocytes [

6]. Furthermore, cell-extrinsic peripheral tolerance mechanisms involve suppression of effector cells by regulatory phenotypes [

7].

In addition to the AIRE expression in thymic medullary epithelial cells, multiple types of extrathymic AIRE expressing cells (eTACs) [

8] were described, especially residing in secondary lymphoid organs, suggesting a putative immune regulatory function confirmed by the expression of immunomodulatory molecules such as IDO (indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase), IL-10 (interleukin 10) and PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1) [

9]. In particular, eTACs possess antigen presenting features as shown by markers that largely overlap with DCs, possibly representing a distinct subgroup [

8,

10] thus with potential function in peripheral tolerance through antigen presentation

via MHCCII (Major histocompatibility complex class II)-TCR. Suzuki et al. detected low AIRE expression in B cells (CD19

+), cells from the monocyte/macrophage lineage (CD14

+) [

11], stromal cells [

12], whereas T-cells (CD65

- CD14

- CD19

-) tested negative [

11]. eTACs were indeed detected in inflamed tissues of patients with autoimmune diseases and in various cancer tissues [

8].

Recent findings indicate that Aire controls immune tolerance by an additional mechanism—the induction of FoxP3-positive T regulatory cells in the thymus that have the ability to suppress autoreactive cells. Thus, Aire deficiency also limits the development of Tregs and/or makes them dysfunctional [

13].

AIRE is a transcription factor with many targets, leading to different responses in different contexts. The exact role of AIRE expression in peripheral tolerance therefore remains to be unraveled. In the light of the foregoing in this manuscript, we set up experimental conditions using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donors (HD) to elucidate whether AIRE could bind to the promoter of known autoantigens, suggesting its putative role in the expression of self-antigens in human peripheral blood.

2. Results

2.1. AIRE Binds to Promoter Regions of Thyroid and Pancreatic Autoantigens in Human PBMC

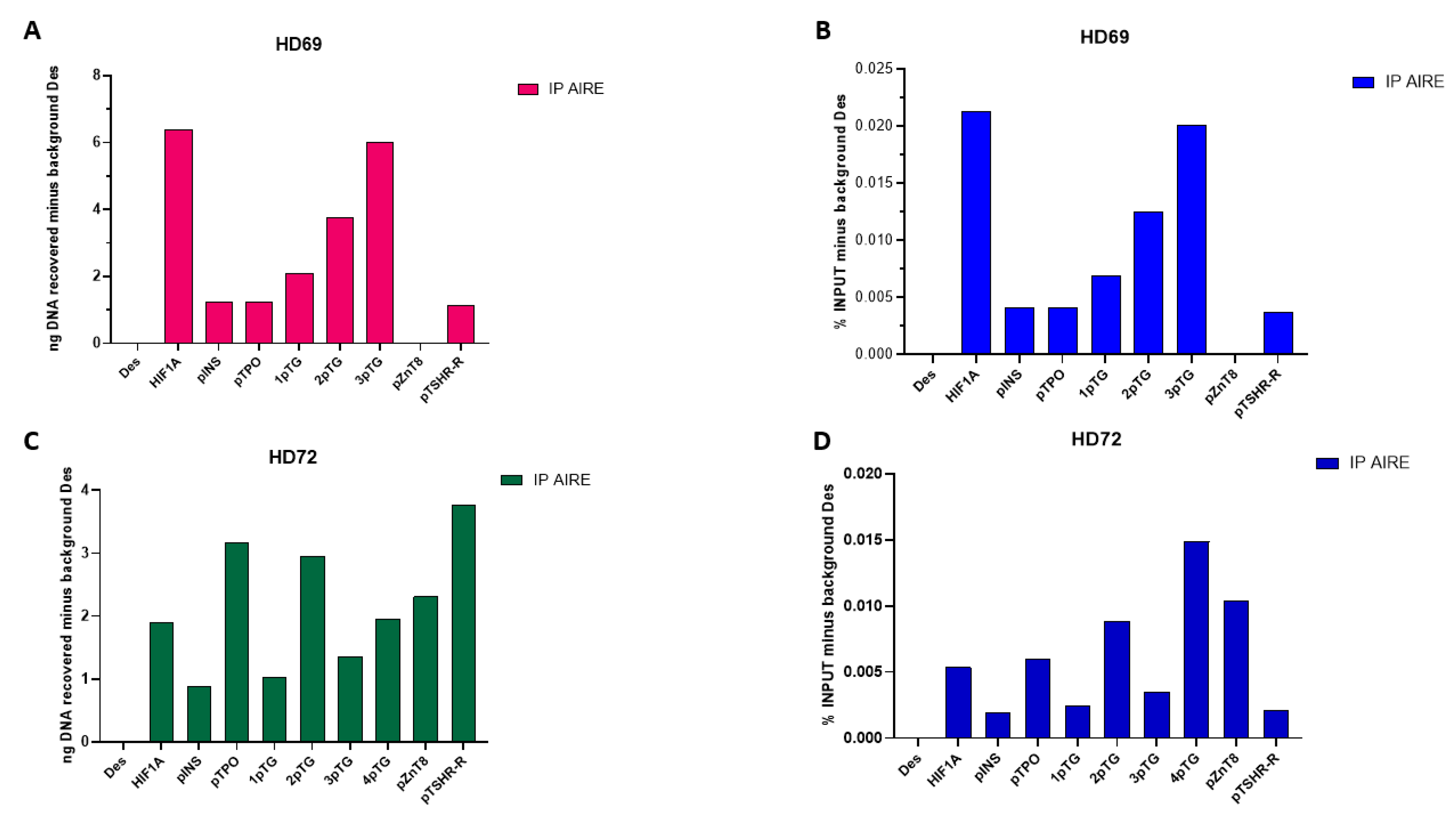

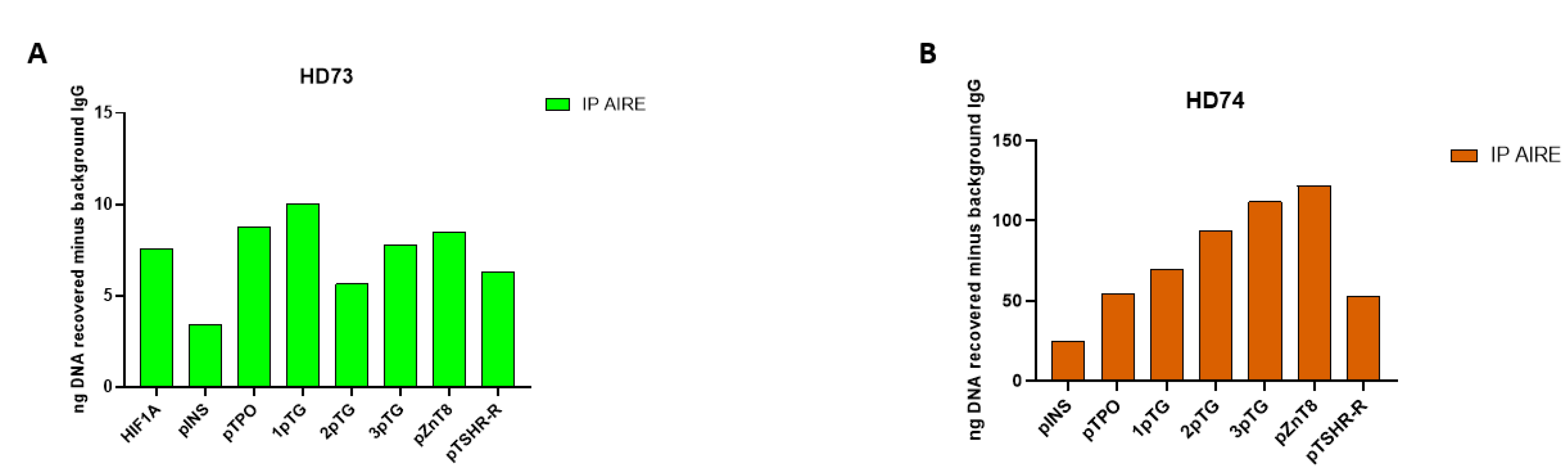

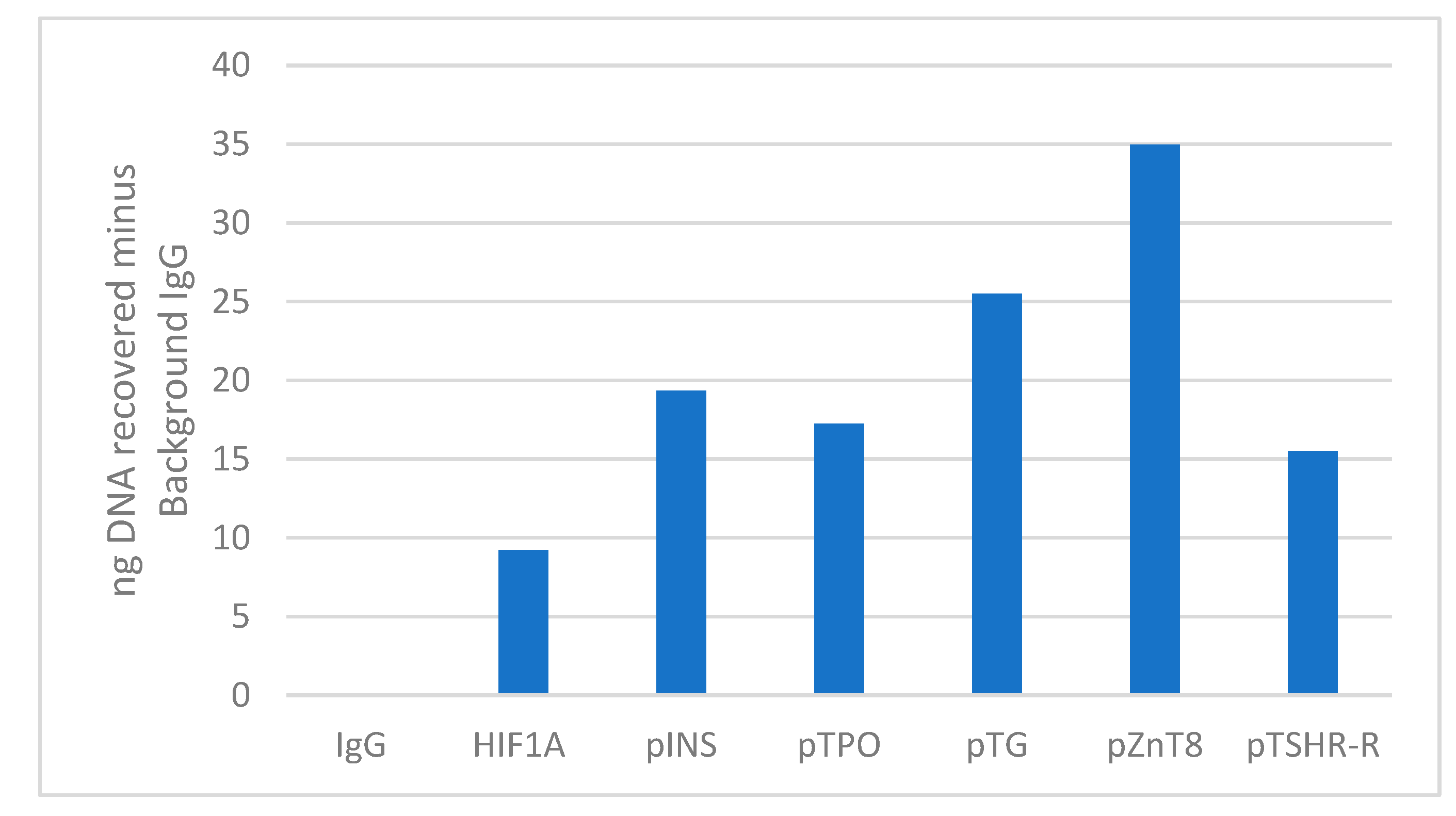

ChIP in PBMC samples of 4 healthy control individuals with anti-AIRE antibody showed amplification of TG, TPO, TSH-R, insulin, ZnT8 promoters compared to negative desert control and negative control IgG (Immunoglobulin G). Absolute signals of relative transcripts analysis over background for each target are represented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Amplicons of ChIP were validated by sequencing. Therefore, TG, TPO, TSH-R, insulin, and ZnT8 autoantigen promoters are direct targets of AIRE in PBMC samples from healthy controls. Input chromatin was very carefully quantified and the quality of the isolated chromatin was highly reproducible; washing and purification steps were performed with absolute accuracy. ChIP of the 4 samples revealed amplicons of Insulin, TG, TPO, TSH-R and ZnT8 with different methods of quantification of ChIP signals estimated as ng of DNA recovered (

Figure 1 A, C) and percentage of input signal minus background of desert gene (

Figure 1 B, D) or ng of DNA recovered minus background IgG (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

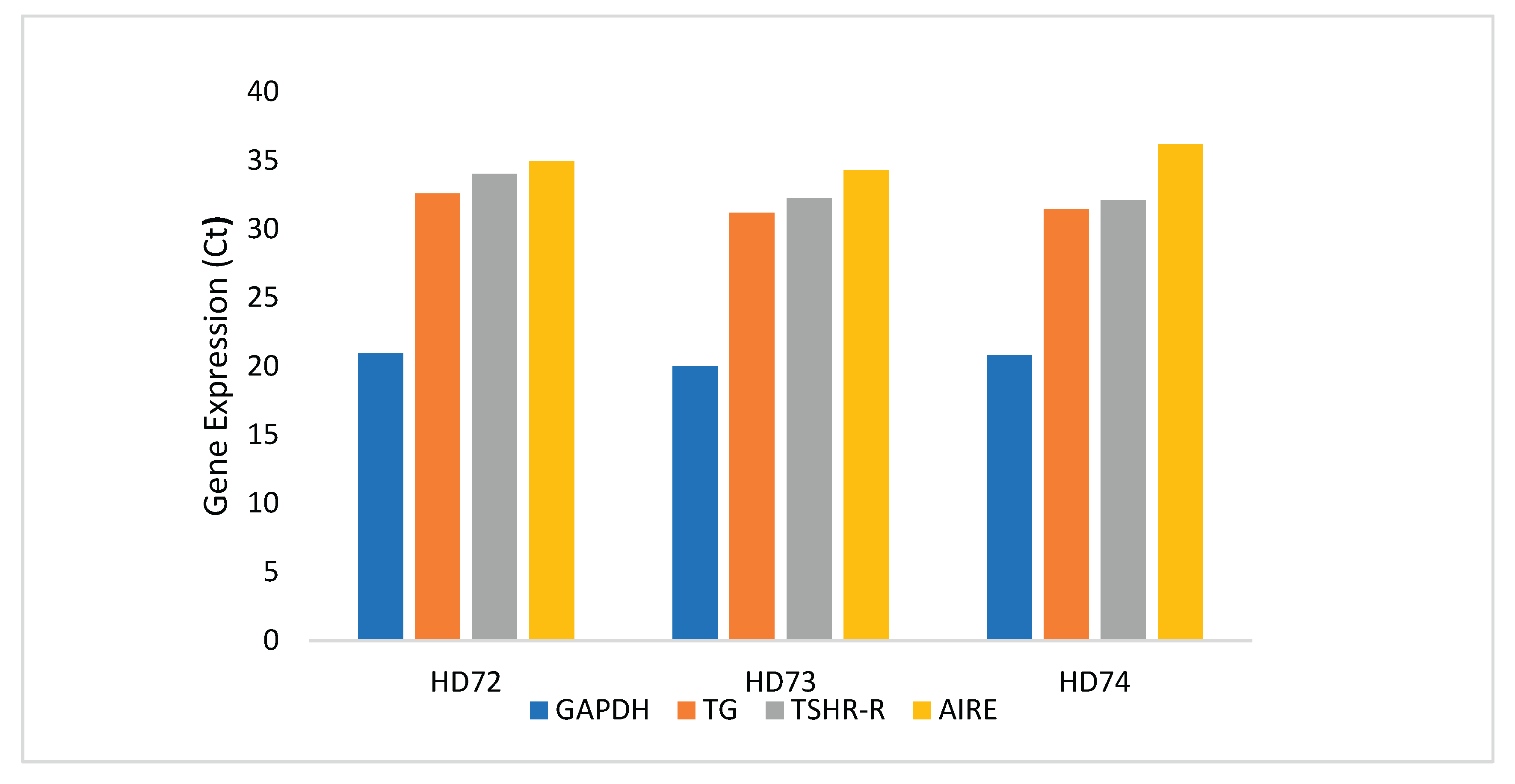

qRT-PCR on PBMC of samples HD72, HD73, and HD74 confirmed AIRE expression and the most abundant relative transcripts of the tested representative TG and TSH-R autoantigens (

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

Potential mechanisms were reported in the literature to explain the contribution of AIRE to peripheral tolerance since its expression correlates with a more mature DC phenotype [

8]. As regard levels of AIRE expression can vary substantially in DC from transient expression to a temporal state of maturation. Evidence for a more direct role of AIRE in DC maturation derives from studies on AIRE deficient cells from APECED patients where monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) exhibit impaired function as well as impaired maturation [

14,

15,

16]. In opposite, AIRE is not crucial for the development of tolerogenic DCs since these can be generated

in vitro from APECED monocytes and their role and function in Tr1 differentiation are similar to tolerogenic DCs generated from HD [

17]. Furthermore, there are clues that AIRE may contribute to peripheral tolerance through the exhaustion of T effector cells. Indeed, in NOD mice [

18] DC-specific overexpression of AIRE results in a decrease of IFN-γ and TNF-α by T-cells. This is accompanied by increased expression of exhaustion-associated markers such as PD1 (programmed death 1), LAG3 (lymphocyte activation gene 3) and TIM3 (T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3) without significant changes in the population of FoxP3

+ T regulatory cells (Tregs).

In this manuscript, the issue of AIRE binding to promoters of known autoantigens was unraveled through ChIP, a valuable tool to study gene regulation, including chromatin remodeling and histone modifications and protein/DNA interactions, even applied to the immunology field [

19]. A monoclonal Ab anti-human AIRE was used to bind and immunoprecipitate chromatin extracted at a high purity level after formaldehyde cross-linking to preserve it. Reverse crosslinking isolated DNA and precipitated material was then analysed by qRT-PCR [

20]. Standardization of the approach is remarkably challenging, especially in the steps of quantitative analysis of the precipitate and normalization of data. Extraction of good chromatin strictly relies on the quality of the starting material generally obtained from human PBMC that are rescued with standardized methods. Shearing of chromatin was then obtained by sonication (hydrodynamic shearing) followed by estimation of sonication efficiency by gel electrophoresis [

20]. For ChIP, we relied on the validated experience of other groups with PBMC as starting material, where low AIRE expression [

11] is detected employing the same anti-AIRE monoclonal antibody we used. Indeed, monoclonal antibodies are at higher specificity compared to polyclonal sera that may recognize several epitopes of the target, increasing the chance of selecting low-abundance templates [

21]. With this monoclonal antibody (Ab) we would expect to overcome the fact that different Abs can differ in their sensitivity to inhibitory factors present in the input chromatin samples. Appropriate controls were introduced by analyzing in parallel the input sample and the control sample to which the normal goat IgG was added in order to estimate the amount of background signal in respect to the ‘true signal’ in the subsequent qRT-PCR.

Normalization of obtained data precedes data interpretation; therefore, the choice of the appropriate normalization method is essential since this can influence the final conclusions. As shown for samples analysed in

Figure 1 results for two HD samples are compared with 2 different methods,

i.e. nanograms of recovered DNA minus desert gene background and percentage of input chromatin with subtraction of desert gene background. Indeed, comparing the results obtained with these 2 different methods did not affect the biological interpretation. Results were also validated for all 4 samples with normalization based on subtracting the IgG background.

In this manuscript, we provided evidence for AIRE binding to promoter regions of known autoantigens in human PBMC, suggesting that this non-conventional transcription factor could indeed have influence through facilitating/modulating autoantigen expression. Of note, qRT-PCR experiments confirm that in PBMC of available samples there is AIRE expression, but also expression of some representative autoantigens, including TG and TSH-R, among those evaluated in this investigation that putatively can occur under the influence of this facilitator/modulator.

In agreement with our results obtained in bulk human PBMC, indeed even in mice certain lymph node stromal cells residing in the lymph node cortex can express AIRE. Strikingly, there is evidence that these cells also express specific tissue-restricted antigens (TRA), including antigens from the eye, intestine, pancreas, liver, central nervous system and skin [

22]. Furthermore, these cells not only express the mRNA of the antigen, but this is also translated into full-length proteins that could potentially be used for antigen presentation and tolerance [

22].

We are aware that functional studies will need to confirm that AIRE is transcriptionally active in the peripheral blood and that mechanistic analysis should be extensively carried out by flow cytometric demonstration of antigen presentation and co-culture assays with autoreactive T-cell clones. To demonstrate the influence of AIRE on peripheral tolerance following binding to promoters of known autoantigens and their expression in the periphery, apoptosis/anergy assays following antigen encounter or transcriptomic/proteomic profiling of purified AIRE-positive PBMC subsets should be carried out whenever the recruitment of biological samples and their amount could allow the execution of these studies. Additionally, the issue of the effect of T regulatory cells in peripheral tolerance under the influence of AIRE expression should be extensively investigated.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human PBMC Recruitment and Sample Collection

To unravel the AIRE mechanism in the pathogenesis of pediatric autoimmune diseases, due to the small amount of blood that can be taken from children, it was necessary to resort to large blood samples that can be obtained from human donors.

PBMC were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Histopaque, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical C, St Louis, MO, USA) from 50 ml sodium heparinized venous buffy coat samples of 4 human HD, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium), and then frozen down in liquid nitrogen.

HD subjects (n = 4) were enrolled in the investigation, recruited at the OPBG Blood Transfusion Centre. The study was approved by the OPBG Ethical Committee Study number 1275_opbg_2016. Written informed consent from human donors was obtained.

4.2. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP of PBMC was performed using Active Motif kit ChIP-IT® PBMC Kit (Vinci Biochem Srl, Florence, Italy) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Briefly, approximately 30x106 PBMC were formaldehyde fixed (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for protein-DNA cross-linking at room temperature (RT) for 15 minutes and the reaction was stopped by adding the solution provided by the kit. Cells were then lysed and sheared to get chromatin fragments by sonicating in Bioruptor Plus Diagenode (Liege, Belgium). Chromatin quantification was calculated with Qubit dsDNA BR assay (Sigma-Aldrich). For each immunoprecipitation reaction, 30 μg of chromatin diluted in 650 μL was incubated with Protein G coated magnetic beads and 7 μg of anti-human AIRE monoclonal (mouse) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C overnight in an end-to-end rotator. For negative control, 8 μg of IgG1 goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) per 30 μg of chromatin was employed. 50 μg/μL of sheared chromatin was used for the input fraction.

As control of the performance of ChIP technology for active chromatin immunoprecipitation, rabbit polyclonal Ab anti-human H3 (acetyl K27) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (2 μg per 25 μg of chromatin) was employed. Genomic DNA from beads was eluted and purified followed by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) to assess enrichment of the hypoxia-inducing factor 1A (HIF1A) promoter as control of immunoprecipitation, known to have a noncanonical

AIRE binding site as direct target of

AIRE [

21]. Primers were selected as follows: forward CCCTTGAAGTTTACAGCAACAG and reverse ACAGGGGAACTCACCTTGTC. As negative control, primers for detecting a gene desert region, known to be devoid of gene encoding proteins, were appropriately designed for qRT-PCR: desert forward CCCAAACTCTGAGAGGCTTATT and reverse GAGCCATCATCTAGACACCTTC. For the desert gene PCR program included 94 °C x 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 seconds, 3 different annealing temperatures 55 °C, 57 °C, 59 °C for 30 seconds and 72 °C for 30 seconds, followed by extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes [

23]. qRT-PCR was then used to analyse promoters of known autoantigens, including thyroid-related thyroglobulin (TG), thyroperoxidase (TPO), thyrotropin (TSH)-receptor (TSH-R) [

24] insulin-dependent diabetes (Type 1 diabetes)-related autoantigens,

i.e. insulin (INS) and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) [

25].

Thyroglobulin promoter (pTG) primers were selected as following: 1pTG forward CAGGTCTCACAGGAACAG and reverse CAACCAAAAGATAGCAGG (109 bp, annealing temperature (AT) 50 °C); 2pTG forward CCTGCTATCTTTTGGTTG and reverse GGTGAGGGAAGCAAAATAC (98 bp, AT 51,5 °C); 3pTG forward GAAGGAGAAGGAGAAAGGGTAG and reverse GTATCTTTGGAGGGAACAGG (93 bp, AT 55 °C); 4pTG forward GGACCTAGGGCAAGCAGTG and reverse CAGCAGGGTGAAGATCTCC (87 pb, AT 58 °C). TSH receptor (pTSH-R) promoter primers included forward CCATTATCTAGTCGCGAG and reverse CTGGAGGTTAAGTGGATG (133 bp, AT 50 °C). TPO promoter (pTPO) primers were forward CACAGTCTCTCCGCTCTC and reverse CTGGGAATTCTCAACGTG (79 bp, AT 54 °C). Insulin promoter (pINS) primers were forward GAGACATTTGCCCCCAGC and reverse CGTCAGCACCTCTTCCTCAG (99 bp, AT 60 °C) and zinc transporter 8 promoter primers (pZnT8) were forward CTAGTTATCCTTGTGGTCAC and reverse CATAGGGTTATTGGGAG (82 bp, AT 48 °C, 50 °C, 55 °C). PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels. Four independent experiments were conducted for the validation of the result. Recovered nanograms of DNA from Immunoprecipitation were estimated by Nanodrop and Qubit dsDNA BR Assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

4.3. Real-Time PCR

RNA was extracted from PBMC samples from the same healthy blood donors employed for ChIP with RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Quiagen, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA was quantified using a nanodrop and reverse transcribed (1000 ng x 2) using Superscript IV First Strand Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Srl, Milan, Italy). The following representative gene transcripts were analysed on RNA of residual PBMC samples: thyroglobulin using forward CCAGTGGCTTCTCTTCCTGACT and reverse CCTTGGAGGAAGCGGATGGTTT primers and TSH-R using forward GAGTTTCCTTCACCTCACACGG and reverse CTGCTCTCATTACACATCAAGGAC primers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.; methodology, C.N., I.M., E.P. and A.F.; software, C.N. and I.M.; validation, A.F.; formal analysis, C.N., I.M., E.P. and A.F.; investigation, C.N., I.M., E.P. and A.F.; resources, C.N. and A.F.; data curation, C.N., I.M., A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N., I.M., E.P. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and A.F.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, A.F.; funding acquisition, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with current research funds (202405_IMMUNO_FIERABRACC to A. Fierabracci).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (Study number 1275_opbg_2016). Written informed consent from human donors was obtained).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of ethical consent for human healthy donors. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Alessia Palma and Anna Lo Russo for technical support for molecular biology techniques and PBMC isolation. We also acknowledge the OPBG Blood Transfusion Centre for providing blood samples from human healthy donor volunteers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TCR |

T-cell receptor |

| AIRE |

AutoImmune REgulator gene |

| mTEC |

medullary Thymic Epithelial Cells |

| APECED |

Autoimmune PolyEndocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal Dystrophy |

| APS1 |

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1 |

| APC |

Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| DCs |

Peripheral tolerogenic Dendritic Cells |

| eTACs |

extraThymic AIRE expressing Cells |

| IDO |

Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin 10 |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| MHCCII |

Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II |

| ChIP |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

| PBMC |

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| HD |

Healthy Donors |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| RT |

Room Temperature |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative Real-Time PCR |

| HIF1A |

Hypoxia-Inducing Factor 1A |

| TG |

Thyroglobulin |

| TPO |

Thyroperoxidase |

| TSH |

Thyrotropin |

| TSH-R |

Thyrotropin Receptor |

| INS |

Insulin |

| ZnT8 |

Zinc Transporter 8 |

| pTG |

Thyroglobulin Promoter |

| pTSH-R |

Thyrotropin Receptor Promoter |

| pTPO |

Thyroperoxidase Promoter |

| pINS |

Insulin Promoter |

| pZnT8 |

Zinc Transporter 8 Promoter |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| DC |

Dendritic Cells |

| moDCs |

Monocyte-derived Dendritic Cells |

| NOD |

Non-Obese Diabetic mice |

| INF-γ |

Interferon gamma |

| TFN-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| PD1 |

Programmed Death 1 |

| LAG3 |

Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3 |

| TIM3 |

T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin domain 3 |

| Tregs |

regulatory cells |

| Ab |

Antibody |

| TRA |

Tissue-Restricted Antigens |

References

- Rosenblum, M.D.; Remedios, K.A.; Abbas, A.K. Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 2228–2233.

- Metzger, T.C.; Anderson, M.S. Control of central and peripheral tolerance by Aire. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 241, 89–103.

- Washburn, T.; Schweighoffer, E.; Gridley, T.; Chang, D.; Fowlkes, B.J.; Cado, D.; Robey, E. Notch activity influences the alphabeta versus gammadelta T cell lineage decision. Cell 1997, 88, 833–843.

- Fierabracci, A. Recent insights into the role and molecular mechanisms of the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene in autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 10, 137–143.

- Perniola, R. Twenty years of AIRE. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 98.

- Gardner, J.M.; DeVoss, J.J.; Friedman, R.S.; Wong, D.J.; Tan, Y.X.; Zhou, X.; et al. Deletional tolerance mediated by extrathymic Aire-expressing cells. Science 2008, 321, 843–847.

- Hamilton-Williams, E.E.; Bergot, A.S.; Reeves, P.L.; Steptoe, R.J. Maintenance of peripheral tolerance to islet antigens. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 72, 118–125.

- van Laar, G.G.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Tas, S.W. Extrathymic AIRE-expressing cells: Friends or foes in autoimmunity and cancer? Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103141.

- Tas, S.W.; Vervoordeldonk, M.J.; Hajji, N.; Schuitemaker, J.H.N.; van der Sluijs, K.F.; May, M.M.; et al. Noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling in dendritic cells is required for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase induction and immune regulation. Blood 2007, 110, 1540–1549.

- Gardner, J.M.; Metzger, T.C.; McMahon, E.J.; Au-Yeung, B.B.; Krawisz, A.K.; Lu, W.; et al. Extrathymic Aire-expressing cells are a distinct bone marrow-derived population that induce functional inactivation of CD4⁺ T cells. Immunity 2013, 39, 560–572.

- Suzuki, E.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kawano, O.; Endo, K.; Haneda, H.; Yukiue, H.; et al. Expression of AIRE in thymocytes and peripheral lymphocytes. Autoimmunity 2008, 41, 133–139.

- Bergström, B.; Lundqvist, C.; Vasileiadis, G.K.; Carlsten, H.; Ekwall, O.; Ekwall, A.H. The rheumatoid arthritis risk gene AIRE is induced by cytokines in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and augments the pro-inflammatory response. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1384.

- Husebye, E.S.; Anderson, M.S.; Kämpe, O. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1132–1141.

- Pöntynen, N.; Strengell, M.; Sillanpää, N.; Saharinen, J.; Ulmanen, I.; Julkunen, I.; et al. Critical immunological pathways are downregulated in APECED patient dendritic cells. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 86, 1139–1152.

- Sillanpää, N.; Magureanu, C.G.; Murumägi, A.; Reinikainen, A.; West, A.; Manninen, A.; et al. Autoimmune regulator induced changes in the gene expression profile of human monocyte-dendritic cell lineage. Mol. Immunol. 2004, 41, 1185–1198.

- Ryan, K.R.; Hong, M.; Arkwright, P.D.; Gennery, A.R.; Costigan, C.; Dominguez, M.; et al. Impaired dendritic cell maturation and cytokine production in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis with or without APECED. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008, 154, 406–414.

- Crossland, K.L.; Abinun, M.; Arkwright, P.D.; Cheetham, T.D.; Pearce, S.H.; Hilkens, C.M.U.; et al. AIRE is not essential for the induction of human tolerogenic dendritic cells. Autoimmunity 2016, 49, 211–218.

- Kulshrestha, D.; Yeh, L.T.; Chien, M.W.; Chou, F.C.; Sytwu, H.K. Peripheral autoimmune regulator induces exhaustion of CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ effector T cells to attenuate autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1128.

- Carey, M.F.; Peterson, C.L.; Smale, S.T. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, 4, pdb.prot5279.

- Haring, M.; Offermann, S.; Danker, T.; Horst, I.; Peterhansel, C.; Stam, M. Chromatin immunoprecipitation: Optimization, quantitative analysis and data normalization. Plant Methods 2007, 3, 11.

- Padmanabhan, R.A.; Johnson, B.S.; Dhyani, A.K.; Pillai, S.M.; Jayakrishnan, K.; Laloraya, M. Autoimmune regulator (AIRE) takes a hypoxia-inducing factor 1A route to regulate FOXP3 expression in PCOS. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 89, e13637.

- Lee, J.W.; Epardaud, M.; Sun, J.; Becker, J.E.; Cheng, A.C.; Yonekura, A.R.; et al. Peripheral antigen display by lymph node stroma promotes T cell tolerance to intestinal self. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 181–190.

- Ovcharenko, I.; Loots, G.G.; Nobrega, M.A.; Hardison, R.C.; Miller, W.; Stubbs, L. Evolution and functional classification of vertebrate gene deserts. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 137–145.

- McLachlan, S.M.; Rapoport, B. Breaking tolerance to thyroid antigens: Changing concepts in thyroid autoimmunity. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 59–105.

- Arvan, P.; Pietropaolo, M.; Ostrov, D.; Rhodes, C.J. Islet autoantigens: Structure, function, localization, and regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007658.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).