1. Introduction

Autoimmune diseases comprise over 80 pathologies that affect around 3-5% of the population [

1]. Polyautoimmunity, a combination of multiple autoimmune diseases within a single patient, is frequently encountered in clinical settings [

2,

3]. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (APS) refers to the damage of two or more endocrine glands leading to their failure, often accompanied by organ-specific non-endocrine autoimmune diseases [

4,

5]. There are two primary types of APS: 1 and 2. APS-1 is a disease resulting from a mutation in the autoimmune regulator (

AIRE) gene, with autosomal recessive inheritance. The syndrome comprises of three primary components: autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), hypoparathyroidism, and candidiasis of the skin and mucous membranes. APS-1 typically appears during childhood [

4,

5]. It is important to note that APS-1 is one of the few types of monogenic autoimmune diseases that primarily affect the endocrine system and follows the principles of Mendelian inheritance [

2,

6]. Much more frequently, there is a complicated interplay between genetic factors that determine susceptibility to illness and the environment. [

1,

2,

5]. Thus, autoimmune endocrine disorders typically have multiple contributing factors [

1]. A prime example is APS-2, also known as adult APS. This condition is typically characterized by the co-occurrence of major components, namely AAI, type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1), and/or autoimmune thyroid diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis (AIT) or Graves' disease (GD) [

7].

Some authors also differentiate between the third and fourth types of APS. APS-3 includes autoimmune thyroid disorders combined with other autoimmune diseases, except adrenal insufficiency. APS type 4 comprises other combinations of autoimmune endocrine diseases that are not major APS 1-3. However, considering the shared pathogenesis and genetic predisposition, APS of the third and fourth types are typically classified as APS of adults, along with APS of the second type, according to most authors [

8].

Antibodies (Ab) targeting specific molecules serve as biomarkers for the autoimmune onset of endocrine diseases and also predict their development. Thus, the primary Ab target proteins in AIT are thyroperoxidase (TPO), an enzyme crucial for thyroid hormone biosynthesis, and thyroglobulin (Tg), a thyroid hormone precursor. The main immunological marker of GD is the presence of anti-thyroid hormone receptor antibodies, detectable in 90% of cases [

9]. In type I diabetes mellitus, the most extensively researched autoantibodies include those targeting glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), insulin (IAA), tyrosine phosphatase (IA2), zinc transporter (ZnT8), and islets of Langerhans cells (ICA) [

10,

11]. A highly sensitive method for confirming the autoimmune origin of adrenal insufficiency is by measuring Ab to P450c21 (21 hydroxylase, 21-OH), a steroidogenesis enzyme that is exclusively expressed in the adrenal cortex [

12]. Finally, autoantibodies to interferon-ω (IFN- ω) and - α2 (IFN- α2), and, when cutaneous mucosal candidiasis is present, also to interleukin-22 (IL-22), have been found in the majority of patients with APS-1 [

13,

14].

Considering the polyautoimmunity phenomenon, it cannot be ruled out that impaired immune tolerance to self-antigens may be a common pathogenetic mechanism underlying the development of various autoimmune diseases. This hypothesis is supported by studies which found several genetic loci playing a crucial part in immunity regulation and contributing to the predisposition to multiple pathologies simultaneously [

5,

15,

16]. Thus, certain alleles of the genes in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) system have been linked to an increased risk of developing autoimmune diseases. Specifically, components of the human leukocyte antigens (HLA) class II encoded HLA-DRB1*03-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201 and DRB1*04-DQA1*0301-DQB1*0302 haplotypes have been associated with various autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, DM1, GD, and AAI [

17,

18]. However, these haplotypes have a high frequency in the general population, with around 20% occurring in central Italy [

19]. Nevertheless, only a minority of carriers develops AAI.

Variations in the

PTPN22,

CTLA-4,

CIITA, and other genes are believed to modulate the risk determined by HLA class II genes [

16]. Most likely, the development of AAI, including APS-2, is determined by the combined effects of mutations in multiple genes that have clinically significant mutual influence. This necessitates a thorough study of multiple genes at once utilizing exome sequencing followed by a genetic roadmap. In addition, a whole-exome study of the proband and his parents provides an additional opportunity to identify novel predictors of autoimmune disease. This article outlines the findings of the genetic and immunologic assessment of two patients with APS-2 (Patient A and Patient B), one patient with AAI (Patient C), and their respective parents.

2. Results

2.1. Detection of autoantibodies in serum samples of patients

The results of testing patient serum samples using ELISA kits and microarray-based assay are shown in

Table 1,

Table S1 and

Figure S1. Antibodies against 21-hydroxylase were found in all patients through ELISA (Patient A, 51.672 U/mL; Patient B, 40.728 U/mL, Patient C: 53.779 U/mL, normal <0.4 U/mL,

Table S1), verified by qualitative microarray analysis. The immunologic test results confirmed the autoimmune genesis of primary adrenal insufficiency in all three patients. Additionally, Patient A exhibited an elevated level of antibodies to tyrosine phosphatase, measuring 27.6 U/mL (normal range: 0-10 U/mL). Patients A and B showed elevated levels of thyroid peroxidase antibodies, while their thyroglobulin antibodies were within the normal range according to both methods. In contrast, Patient C's insulin antibodies were notably increased (18.4 U/mL), but their antibodies to tyrosine phosphatase, zinc transporter 8, pancreatic islet cells, and glutamate decarboxylase were all within standard reference values. Furthermore, antibodies to gliadin and tissue transglutaminase were not detected. None of the patients had antibodies to type I interferons and interleukin-22 by microarray analysis, which made it possible to exclude the diagnosis of APS-1, for which these markers are highly specific [

20,

21]. The latter was especially important for Patient C, who, in addition to AAI, was diagnosed with esophageal candidiasis.

2.2. Characterization of the exome data

The primary quality control metrics for the entire-exome sequencing of patient samples are presented in

Table 2. The sex chromosome karyotype and outcomes of the

SRY gene analysis matched the information provided in the patient medical records. All nine exome datasets exhibited high quality and were suitable for further analysis.

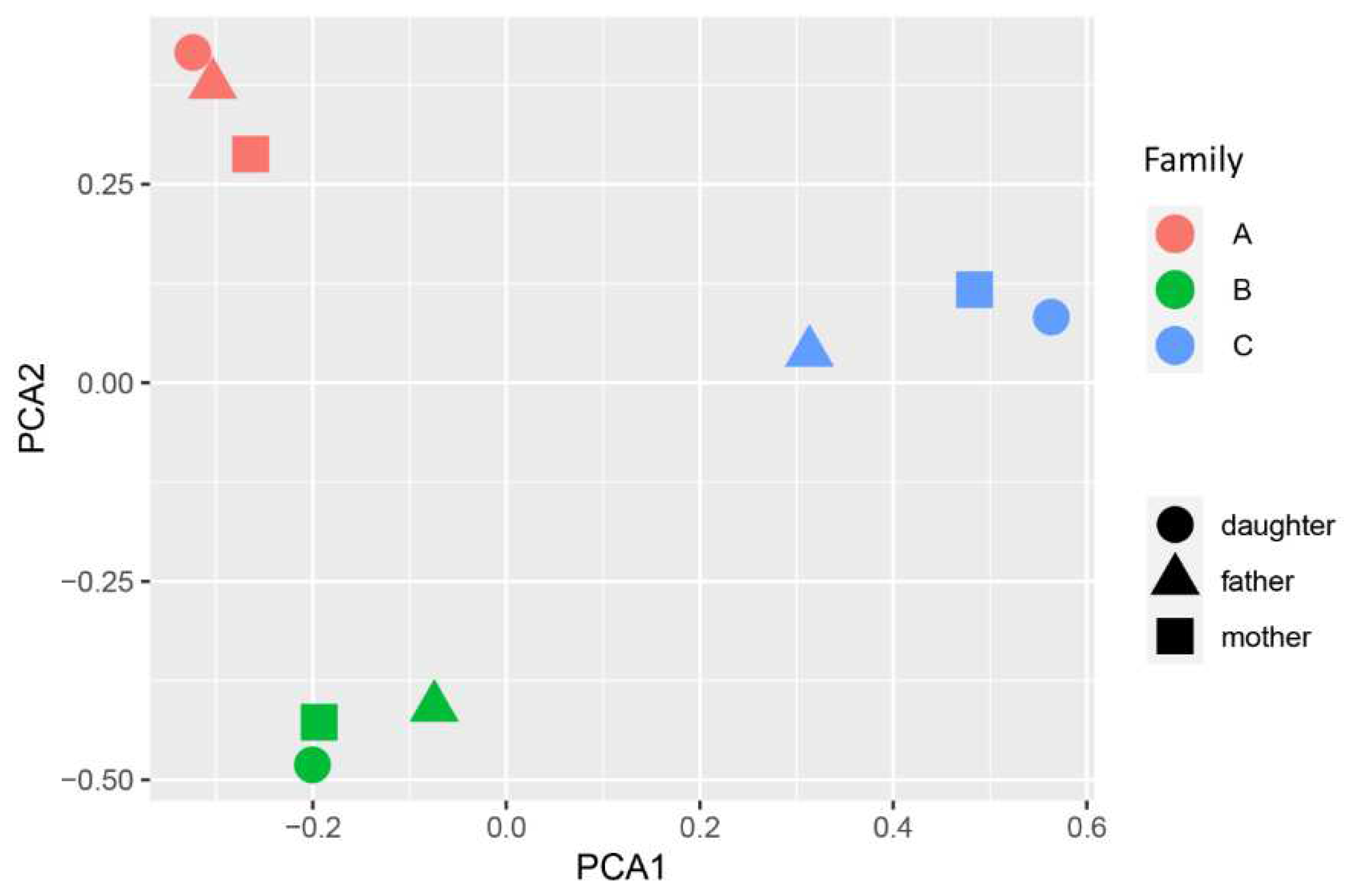

The overall genotyping quality of the samples was 99.75%. Principal component analysis (PCA) data showed a pronounced genetic distance between families (

Figure 1). A total of 2497 variants in sex chromosomes, which were excluded during PCA, and 155188 variants in autosomes were present in the sample.

According to the identity by descent (IBD) analysis, the daughters inherited approximately 50% of the variants from each parent (refer to

Table S2). Moreover, 17.26% of the variants present in the parents of the Family A were also detected to overlap. Analysis by runs of homozygosity (ROH) revealed a 1083.817 kb single region on Chromosome 1 of Proband B, from genomic position 45206495 to 46290311, with a SNP distribution density of 10.035 and 99.1% proportion of homozygous variants. This region matched the paternal (45163647-46487552) and did not contain any pathognomonic genes. The proband's mother had heterozygous variants in this region at a higher proportion than what is allowed for ROH.

2.3. Analysis of genetic variants

Table 3 summarizes APS-specific genetic variants that we have detected and were previously described [

22,

23].

No clinically significant gene variants were identified from the HPO ‘Autoimmunity’ panel HP:0002960 [

24] (

Table S3). Detailed results of the interpretation of nucleotide sequence variants are presented in

Table S4, which is based on our custom panel utilizing literature data.

Table S5 showcase variants marked as pathogenic by at least one Clinvar user. Given the high frequency most of variants within the healthy population, we recommend interpreting them as ‘risk alleles‘. A heterozygous variant of uncertain clinical significance (VUS)

FOXE1 (NM_004473.4):c.743C>G (p.Ala248Gly) in patient B was inherited from the mother and has been identified as a risk factor for thyroid carcinoma [

25]. The

FOXE1 gene is also associated with the development of autoimmune thyroiditis [

26,

27]. Paternally transmitted heterozygous pathogenic variant

MCCC2 (NM_022132.5):c.1574+1G>A from patient B associated with 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase 2 deficiency. Because this disease is monogenic, no additional phenotype is expected, and no second causative allele was found, the variant was not included in

Table S5. For an identical reason, we did not include carriage of the pathogenic variant

COL7A1 (NM_000094.4):c.682+1G>A in patient C, inherited from her mother and associated with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, as well as the likely pathogenic variant

HFE (NM_000410.4):c.187C>G (p.His63Asp associated with hemochromatosis, type 1, which she inherited from her father. Patient C has the repeatedly described in the literature

BRCA1 (NM_007294.4):c.5074G>C (p.Asp1692His), which is consistent with the genealogical history: her maternal grandmother was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Next, we examined variants that have not been previously reported in the clinic (

Table S4) and were classified as not benign and likely benign based on the criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [

28].

Patient A inherited VUS in the

CLEC16A gene (NM_015226.3):c.3097G>A (p.Ala1033Thr) from their father, with both being heterozygous. Homozygotes have not been reported in the Genome Aggregation Database (

gnomAD), and no syndrome is associated with this variant in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. Despite

in silico predictions of benignity, the variant is considered as VUS due to the unknown inheritance type. The

CLEC16A gene has been described in broad association with autoimmune diseases, among them autoimmune thyroiditis and AAI [

29].

Patient B was found to have a heterozygous maternally transmitted VUS:

CLEC16A (NM_015226.3):c.2083G>A (p.Asp695Asn) and

ABCA7 (NM_019112.4):c.3187G>A (p.Glu1063Lys), and the former variant is not present in gnomAD. The

ABCA7 gene encodes a protein responsible for phagocytosis [

30]. Some evidence suggests that individuals with schizophrenia may have abnormal autoimmune responses and higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in their blood [

31]. This finding could potentially extend to other immune disorders as well.

No new clinically significant variants from gene panel were found in Patient C.

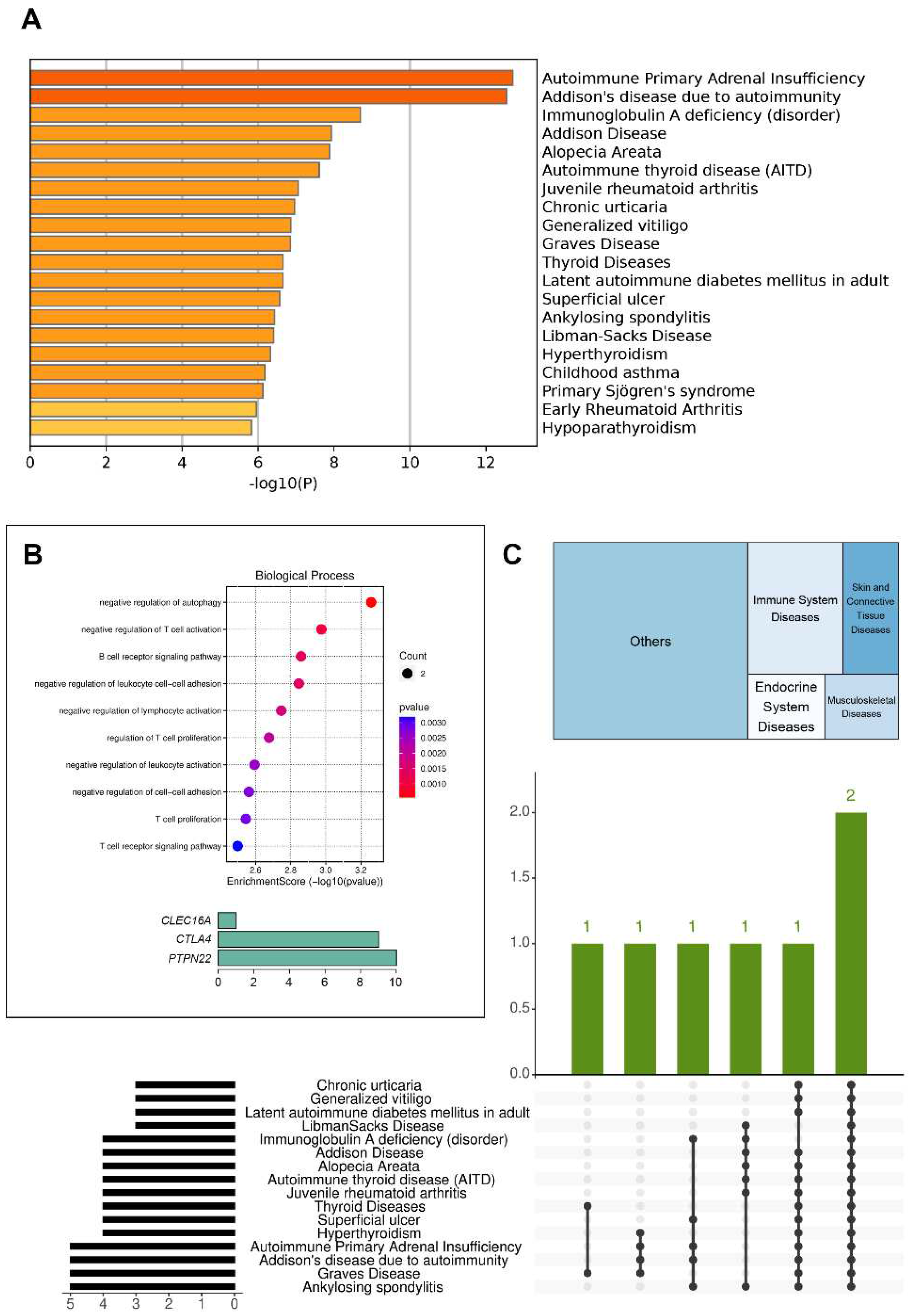

Since patient B had the largest number of variants in genes associated with autoimmune diseases among all probands, we performed gene enrichment analysis for her using Metascape and SRplot (

Figure 2).

2.4. Overview of HLA system risk and protective alleles/haplotypes in studied families and controls.

The results of HLA typing of class II loci are presented in

Table 4 and

Table S6. In Family A, the daughter had

DRB1*03:01:01:01G,

DQA1*05:01:01:01G, and

DQB1*02:01:01:01G alleles, which were characteristic of APS-4 [

22]; they were inherited from the father. The frequency of this haplotype in a healthy Russian population is 6.4912%. Probands from families B and C possessed alleles related to APS types 2, 3, and 4. Notably, alleles

DQA1*03:01:01G and

DQB1*03:02:01G are characteristic of APS-2 and APS-3. The

DRB1*04:04~DQA1*03:01~DQB1*03:02 haplotype related to APS-2 has an incidence rate of 1.8098% amongst healthy volunteers. Meanwhile, the

DRB1*04:01~DQA1*03:01~DQB1*03:01~DQB1*03:02 haplotype characteristic for APS-3 has occurrence rate of 1.9347%.

We analyzed the HLA haplotype frequencies of both our patients and healthy volunteers from the bone marrow donor registry, as shown in Table S7. Of the six proband haplotypes resulting from a combination of alleles from seven genes, four were not encountered in the control sample and have a frequency of less than 0.0624%, while the remaining two haplotypes have frequencies of 0.2% and 2%, respectively, and are common in the population. Following partitioning and analysis into separate classes, namely Class I with three genes and Class II with four genes, Class I showed a total of six unique haplotypes with four occurrences (frequencies of 2%, 4%, 0.5%, and 0.025%), while two occurrences with a frequency less than 0.003% were not found in the control sample. In Class II, the frequencies were 3%, 6%, 0.2%, 0.3%, and 0.9%.

3. Discussion

Our study involved genetic testing for not only the patients with AAI but also their family members (specifically the parents). This design was chosen to ensure accurate interpretation of the genetic findings. Therefore, it is imperative to analyze the clinical characteristics and genetic information of the patient and their family members to assess phenotype-genotype correlations. Identified pathogenic or variants of uncertain significance in parents may contribute to the subclinical course of the disease. Conversely, the absence of pathology in parents with pathogenic mutations may be due to protective variants in other genes or environmental factors. Additionally, the development of the disease in the patient may result from a complex interplay of various genetic factors.

All patients had serum autoantibodies against 21 hydroxylase, confirming the significance of this marker for the diagnosis of AAI [

12]. In the analyzed group, all individuals had

AIRE gene variants that were either benign or likely benign (

Table S3). Based on the clinical data and results indicating an absence of antibodies against interferon-α and -ω, as well as interleukin-22, APS-1 has been ruled out. This determination was particularly crucial for Patient C, who had been diagnosed with esophageal candidiasis in addition to AAI. However, recent evidence highlights heterozygous or dominant-negative mutations causing only partial

AIRE gene function loss. Such defects could contribute to the development of varied autoimmune diseases in the affected person, but with a delayed onset, mild course and not necessarily manifested in multiple forms [

32]. Carriage of antibodies without apparent disease has also been reported [

23].

Significant associations between variants and diseases as defined by

genome-wide association studies (GWAS) usually have a frequency of over 3% in gnomAD. This means that they are considered to be benign based on the ACMG criteria. However, the rarity of AAI in Russia makes it unfeasible to collect DNA samples from thousands of patients required to conduct GWAS to determine the significance of certain variant for pathogenesis. For instance, primary adrenal insufficiency has a global prevalence rate of 115 patients per 1 million population [

12]. For Russia, a country with a population exceeding 140 million people, conducting GWAS studies is feasible. However, the current lack of a unified register of patients with AAI in the Russian Federation and the fragmented information on patients significantly complicates the process [

33].

In the present study, we identified established mutations in the

CTLA4,

PTPN22,

NFATC1,

GPR174, and

VDR genes, which are linked to endocrine autoimmunity [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38], that were inherited from their parents in patients with this condition. Patients with APS-2, in contrast to patient with AAI only, each inherited a distinct VUS in the

CLEC16A gene: (NM_015226.3):c.3097G>A (p.Ala1033Thr) in Patient A and (NM_015226.3):c.2083G>A (p.Asp695Asn) in Patient B. These variants have not been previously described.

CLEC16A genetic variations have been associated with various autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, Crohn's disease, AAI, rheumatoid arthritis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [

39].

In this study, we conducted a whole-exome analysis but not a whole-genome analysis. It is worth noting that approximately 90% of the variants identified through GWAS are located in noncoding regions, which include both intronic areas and intergenic regions. Chromosomal crossovers among patients with various autoimmune diseases are undeniable, making it challenging to distinguish between different nosologies at the genomic level [

40]. In the presented case, Patient A manifests mutations in the

AMPD1, PRSS1, STOX1, MBL2 and

SAA1 genes. Further, Patient B also displays pathogenic mutations in the

KLKB1, MCCC2, PRSS1, SAA1, PTPRJ, ABCC6, SERPINA7, IL4R, BCHE genes; while patient C exhibits such mutations in the

KLKB1, FGFR4, ASAH1, STOX1, SAA1, TENM4, ABCC6, PKD1,

COL7A1, HFE, BRCA1 and

CST3 genes (as partially shown in

Table S4). Associations have been reported between non-endocrine autoimmune pathologies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune myocarditis, and most of the genes listed.

SAA1 and

ABCC6 gene variants were present in all patients of the study. However, current evidence does not support linking these variants to autoimmune endocrinopathies as they can also occur in patients without autoimmune diseases [

41].

Comparable challenges arise when attempting to relate a single variant to pathology as they are often situated within the haplotype [

42]. Additionally, 22% of loci connected with APS display heterogeneity in phenotype [

43]. Haplotypes that are presumed to be concerned with a certain disease are found in a healthy population with high frequency. The occurrence of the disease cannot be wholly attributed to the haplotype allele combination since there exists a significant linkage disequilibrium between genes present in haplotypes. Thus, if only one of the genes contributes to disease causality, the alleles of the other genes may not have any pathogenetic significance.

HLA-DRB1 could be considered the pivotal gene in this case, based on its connection with autoimmune diseases, in tandem with the

DRB1*04 allele group. The

HLA-DQB1 and

HLA-DQA1 alleles, which also figure in other haplogroups, further support this claim.

The proband of Family A was characterized by alleles DRB1*03:01:01:01G, DQA1*05:01:01:01G and DQB1*02:01:01:01G associated with APS-4. However, the 6.4912% significant frequency of this allele in the population does not establish a clear association with the disease. In our opinion, HLA typing outcomes may be impacted by the presence of rare Family A alleles in European Russia. Additionally, the HLA-A and HLA-DPB1 genes pose challenges for haplotype analysis due to their distance from other MHC genes and minimal linkage disequilibrium. Probands from Families B and C possessed alleles related to APS types 2, 3, and 4. Specifically, alleles DQA1*03:01:01G and DQB1*03:02:01G are characteristic of APS-2 and APS-3, respectively. Nevertheless, the haplotypes' frequencies found in both Patients B and C are much more prevalent in the general population than the disease associated with them.

In the future, to identify genetic predictors of autoimmune endocrinopathies, the entire genome of patients and their family members should be analyzed, including non-coding regions such as intronic and intergenic regions, to identify clinically significant variants. Furthermore, this study should be conducted on a much larger patient sample.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

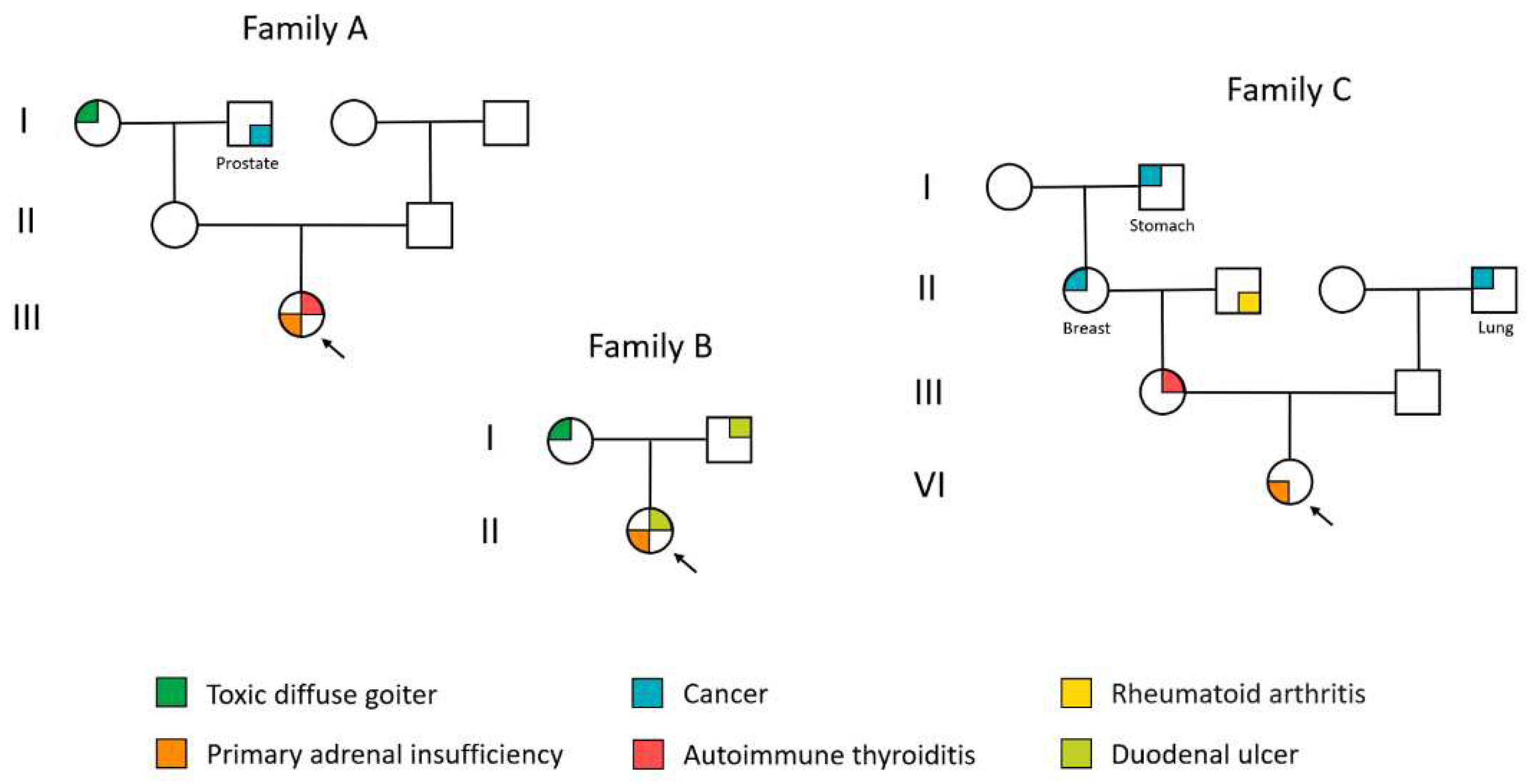

Patient A (female) was enrolled in the study at the age of 22 years. At age 16, she received a diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism due to autoimmune thyroiditis and takes levothyroxine sodium. At 18 years old, the patient exhibited clinical indications of primary adrenal insufficiency, including skin darkening around the knee and elbow joints as well as groin folds, vomiting, a desire for salty food, and a weight loss of 16 kg. The symptoms progressed over time and within two years, the patient experienced an Addisonian crisis, requiring urgent hospitalization. Hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone therapy was initiated during hospitalization. The patient presented with comorbidities, including Setton nevus and latent iron deficiency. There was no inheritance for autoimmune diseases. The patient's mother experienced an acute cerebral circulatory disorder at the age of 50, while her father had chronic pancreatitis. Her maternal grandmother was diagnosed with nodular goiter, and her maternal grandfather had prostate cancer that metastasized to the stomach. Additionally, her paternal grandfather had arterial hypertension from a young age. The results of laboratory examinations at the last hospitalization are presented in

Table 5.

Patient B, a female participant, was enrolled in the study at the age of 28 after presenting with complaints of skin darkening, dry skin, hair loss, general weakness, nausea, and cravings for salty foods. Primary autoimmune-related adrenal insufficiency was confirmed at the Endocrinology Research Center, Ministry of Health of Russia, through the insulin hypoglycemia test (

Table 5). Administration of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone commenced as treatment. The patient reported no menstrual disorders. Related pathologies included autoimmune thyroiditis in the euthyroid stage, nodular goiter (EU-TIRADS 2), peptic ulcer of the 12-peritoneum, hemorrhoids, and a surgically removed lipoma on the back area at age 28 years old. The dermatologist examined the patient due to suspicion of papillary lichen planus. The family history includes peptic ulcer disease in both the patient's father and grandfather, as well as diffuse toxic goiter in the patient's mother.

The female patient C underwent her initial examination at the Endocrinology Research Center, Moscow, Russia at the age of 20. Based on the medical documentation provided, acute hypoxia was observed upon birth. Thereafter, the infant experienced diarrhea and weight loss from the first few days of life, with a diagnosis of anus atresia and intermediate fistula (surgical treatment was performed at 3.5 years old). Since the first year of life, the patient has experienced nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (unrelated to meals), and frequent fainting, particularly in connection with acute respiratory viral infections and emotional stress. As a result, she has been frequently hospitalized in the infectious diseases department. At age 15, she underwent her first hormonal examination due to a sudden 10kg weight loss, salt cravings, and skin darkening. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels were measured at 1008 pg/mL. Blood cortisol levels were found to be 40.2 nmol/L, while aldosterone levels were 49 pmol/L. Renin levels were determined to be 141 IU/L. Primary adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed, and treatment with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone was initiated. According to the patient's medical history, reactive hepatitis was diagnosed at the age of 18, and ophthalmologic examination revealed partial ptosis of both eyelids.

Table 5 presents the laboratory test results from the patient's most recent hospitalization. The examination revealed the following comorbidities: hyperprolactinemia without a pituitary adenoma (the patient was started on treatment with a dopaminergic receptor agonist) and moderate regurgitation due to mitral valve anterior leaflet prolapse. It is noteworthy that the patient was additionally diagnosed with esophageal candidiasis. The patient's medical history indicates several hereditary conditions. Her mother's medical records indicate diagnoses of ovarian cancer, primary hypothyroidism resulting from autoimmune thyroiditis, nodular goiter, and polycystic ovary syndrome. Additionally, other family members have been diagnosed with breast cancer (maternal grandmother), gastric cancer (maternal grandmother's father), rheumatoid arthritis (maternal grandfather), and lung cancer (paternal grandfather).

The probands’ hereditary history is shown in

Figure 3.

4.2. Clinical samples and genomic DNA isolation

Serum samples were collected from patients and stored at −80°C. Venous blood samples were collected from both patients and their parents. Genomic DNA was extracted from total peripheral human blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

4.3. Detection of autoantibodies in serum samples by ELISA kits and microarray-based assay

All patients serum samples were measured by ELISA to detect autoantibodies to P450c21 (21-OH, BioVendor Laboratory Medicine, Brno, Czech Republic), thyroperoxidase (TPO, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA), and thyroglobulin (TG, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), tyrosine phosphatase (IA2), islet cell antigens (ICA), zinc transporter 8 (Zn8, all – from Medipan, Berlin, Germany), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) (Biomerica, Irvine, CA, USA), insulin (IAA), parietal cells of the stomach (ATP4), Castle intrinsic factor (GIF, all – from Orgentec, Mainz, Germany). Serum sample of Patient C was additionally tested for antibodies against gliadin (GLD, Vector-Best, Novosibirsk, Russia) and tissue transglutaminase (TGM2, Orgentec, Mainz, Germany).

Serum samples of patients were assayed using hydrogel microarray with immobilized antigen for detection of autoantibodies to interleukin 22 (IL-22), omega and alpha-2-a interferons (IFN-ω and IFN-α-2a) and organ-specific autoantibodies to 21-OH, GAD, IA2, ICA, TG, and TPO. The microarrays were manufactured as described previously [

20]. Each antigen was immobilized in 4 repetitions to increase the reproducibility of the assay results. Patient serum samples were diluted 1:100 (100 mM Tris-HCl buffer with 0.1% Triton X-100) and applied to the microarray (100 µl). After overnight incubation at 37 °C, intermediate washing (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, 20 min), rinsing and drying, the microarrays were developed with fluorescently labeled anti-species antibodies. As detecting antibodies, we used F(ab')2-Goat anti-Human IgG Fc gamma Secondary Antibody (Cat # 31163, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) labeled with Cy5 cyanine dye. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, the microarrays were washed (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, 30 min), rinsed and dried by centrifugation. Registration of fluorescent images of microarrays and calculation of fluorescent signals were performed using a microarray analyzer and software developed at the Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, Moscow. Interpretation of the results of analysis on a microarray with the determination of the presence/absence of autoantibodies in blood serum were performed as described previously [

20,

21].

4.4. Exome Sequencing and Genetic Examination

DNA Libraries were prepared from 500 ng of genomic DNA using the MGIEasy Universal DNA Library Prep Set (MGI Tech, Shenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA fragmentation was performed via ultrasonication using Covaris S-220 (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA) with an average fragment length of 250 bp. Whole-exome enrichment of DNA library pools was performed according to a previously described protocol [

44] using the SureSelect Human All Exon v7 probes (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The concentrations of DNA libraries were measured using Qubit Flex (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of the prepared libraries was assessed using Bioanalyzer 2100 with the High Sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The enriched library pools were further circularized and sequenced via paired end sequencing using DNBSEQ-G400 with the DNBSEQ-G400RS High-throughput Sequencing Set PE100 following the manufacturer’s instructions (MGI Tech, Shenzhen, China), with the average coverage of 100× Fastq files generated using the basecallLite software (ver. 1.0.7.84) from the manufacturer (MGI Tech, Shenzhen, China).

Bioinformatics analysis of sequencing data was performed through a series of steps. The quality control of the obtained paired fastq files was performed using FastQC v0.11.9 [

45]. Based on the quality metrics, fastq files were trimmed using BBDuk by BBMap v38.96 [

46]. Trimming data were aligned to the indexed reference genome GRCh37 using bwa-mem2 v2.2.1 [

47]. SAM files were converted into bam files and sorted using SAMtools v1.10 to check the percentage of the aligned reads [

48]. The duplicates in the obtained bam files were marked using Picard MarkDuplicates v2.22.4 [

49] and excluded from further analysis.

Quality control analysis on marked bam files with the following Agilent all-exon v7 target file “regions.bed”. For the samples that passed quality control (width of target coverage 10× ≥ 95%), single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels were called using the bcftools mpileup software v1.9 [

50] and vcf files were obtained for each sample.

Alignment quality was assessed on a bam file with labeled duplicates using a bed file containing information on targeting regions. After variant calling, vcf files were normalized using vt normalize v0.5772 [

51] and filtered based on the target regions expanded by ± 100 base pairs flanking each end. Calling data were annotated using the InterVar software [

52]. The significance of nucleotide sequence variants was evaluated based on the ACMG criteria [

25]. Variants with a read depth of 14x or higher were exclusively selected for consideration. The clinical significance of nucleotide sequence variants was evaluated based on the ACMG criteria [

25]. Variants with a read depth of 14× or higher were exclusively selected for consideration.

Genes from the HPO ‘Autoimmunity’ panel HP:0002960 [

24], excluding HLA genes, and our custom panel based on literature data (

Table S8) were analyzed. A group of 637 healthy volunteers, who had undergone whole-exome sequencing in a previous study [

53], was utilized as controls. Before performing the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT), we removed 1790 variants from the vcf file due to genotyping quality less than 95%. We conducted TDT and PCA utilizing plink v1.90b6.24 software [

54] to determine the genetic distance of the samples. Due to the small sample size, corrected P values were not reported as all variants exhibited P > 0.05 in the ‘.tdt.adjusted‘ file. To evaluate relatedness, IBD was employed as an additional control, along with default parameters for runs of homozygosity (ROHs). Graphical data depiction was executed utilizing R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The charts of gene enrichment analysis following DisGeNET categories were created using the Metascape v3.5.20230101 [

55] and UpSet plot generated using the SRPLOT online tool (

http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/srplot (accessed on 18 November 2023)).

4.5. High-Resolution HLA Typing

The preparation of amplicon libraries for HLA high-resolution genotyping was performed using HLA Expert kit (DNA Technology LLC, Moscow, Russia) following the manufacturer’s protocol (Kit was approved by Russian Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare (Roszdravnadzor)). It included several steps. The first stage involved a qPCR for human gene that does not have pseudogenes and is presented in a single copy. This was required for the estimation of a concentration and the presence of inhibitors in a genomic DNA sample. The results were used for normalization of DNA amount during the following step. The second stage involved a multiplex PCR for most variable exons (2, 3, 4 for the HLA class I and 2, 3 for the HLA class II). Primers were designed using conservative regions of gene introns flanking the exons. Several primers with one nucleotide shift were used to prevent an imbalance in nucleotide content during sequencing. The third stage involved ligation of the adapters containing Illumina i5 and i7 indexes. The fourth stage was an additional routine PCR (6 cycles) with the p5 and p7 primers. The purification with magnetic beads (SPRI type) was performed after each stage. Quality control of the libraries was performed using agarose gel electrophoresis; the concentration was measured using the Qubit 3 fluorometer with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

Sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fastq files were analyzed with HLA-Expert software (DNA Technology LLC, Moscow, Russia) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Obtained exon sequences were aligned to the MHC sequences IMGT/HLA v3.41.0 [

56].

Basic quality control metrics for QC included:

- -

quality threshold for reads (low quality reads were trimmed or discarded);

- -

lowest absolute and relative coverage for each position;

- -

the highest number of differences (insertions, substitutions, deletions) from the group average for each read;

- -

maximum relative position error - the number of differences (insertions, substitutions, deletions) from the consensus sequence in each position should not exceed the specified threshold;

- -

the highest average error per read for a group;

- -

the lowest number of reads in groups for each exon (I-class 2,3,4 exons, II-class-2,3 exons);

- -

the allelic imbalance should not exceed a given threshold; the ratio of the read number for the exons from each allele and the sum of these ratios;

- -

the presence of phantom (cross-mapping) and chimeric sequences;

- -

the percentage of combined, clustered, and used for typing reads computed for each sample.

Haplotype frequencies were estimated by Arlequin version 3.5.2.2 [

57] using the expectation-maximum algorithm. Haplotype frequencies were determined for the class I loci, class II loci, five loci (A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1) and six loci (A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1, DPB1).

4.6. Sanger Sequencing

The following SNPs were additionally verified by Sanger sequencing: rs2476601 in the

PTPN22 gene, rs731236 and rs7975232 in the

VDR gene, rs72650691 and rs1183715710 in the

CLEC16A gene, rs538912281 in the

FOXE1 gene, and rs758401262 in the

ABCA7 gene. Sanger sequencing was performed using a 3730xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Nucleotide sequence alignment was performed using the Chromas Lite 2.1 program (Technelysium Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Australia). A comparative analysis of DNA sequences and polymorphisms was conducted using the Unipro UGENE software [

58], with reference to corresponding regions of the

PTPN22,

VDR,

CLEC16A,

FOXE1, and

ABCA7 genes from the GenBank database.

5. Conclusions

Immunological examination can detect antibody carriers and predict the risk of autoimmune disease development. However, a genetic trio-based examination and high-resolution HLA typing did not provide clear predictors of autoimmune endocrinopathies. Therefore, conducting whole-genome sequencing on a larger cohort of patients and their families is advisable to identify clinically significant variants in non-coding regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Fluorescence images of the microarray and medians of normalized signals from the microarray elements after assaying the serum samples from patients. Table S1: Detection of Autoantibodies by ELISA kits. Table S2: Identity by descent (IBD) of members of three families. Table S3: Genetic variants detected by using a HPO panel (Family A, Family B, Family C). Table S4: Genetic variants detected using a custom panel (Family A, Family B, Family C). Table S5: Variants assigned Clinvar pathogenic clinical significance. Table S6: Results of high-resolution HLA typing. Table S7: Haplotype frequencies for family members. Table S8: A list of genes linked to autoimmune diseases, excluding HLA, currently under investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O.K., M.Y.Y., D.A.G; methodology, A.A.B., V.V.C., O.N.S., A.O.S., A.F.S., D.O.K.; software, A.A.B., V.V.C., O.N.S.; investigation, A.A.B., A.O.S., A.F.S., E.V.K, E.N.S.; formal analysis, A.A.B., V.V.C., O.N.S., M.Y.Y.; resources, D.V.R., D.O.K.; examination of patients, M.Y.Y., N.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.B., M.Y.Y., N.F.N., D.A.G.; writing—review and editing: A.A.B., E.A.T., M.Y.Y., D.A.G.; visualization, V.V.C., O.N.S; project administration, D.O.K.; funding acquisition, D.V.R., D.A.G.; supervision, E.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation to the EIMB Center for Precision Genome Editing and Genetic Technologies for Biomedicine under the Federal Research Program for Genetic Technologies Development for 2019-2027 (agreement number 075-15-2019-1660; microarray-based autoantibodies detection and Sanger sequencing) and by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation allocated to the Center for Precision Genome Editing and Genetic Technologies for Biomedicine (agreement number 075-15-2019-1789; whole-exome sequencing).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the Endocrinology Research Centre, Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia (protocol .17 and date of approval 27 September 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its

Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kochi, Y. Genetics of autoimmune diseases: perspectives from genome-wide association studies. Int. Immunol. 2016, 28, 155-161. [CrossRef]

- Anaya, J.M.; Rojas-Villarraga, A.; García-Carrasco, M. The autoimmune tautology: From polyautoimmunity and familial autoimmunity to the autoimmune genes. Autoimmune Dis. 2012, 2012, 297193. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Monsalve, D.M.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, M.; Zapata, E.; Naranjo-Pulido, A.; Suárez-Avellaneda, A.; Ríos-Serna, L.J.; Prieto, C.; et al. New insights into the taxonomy of autoimmune diseases based on polyautoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 126, 102780. [CrossRef]

- Charmandari, E.; Nicolaides, N.C.; Chrousos, G.P. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 2014, 383, 2152-2167. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, R.M.; Giuffrida, G.; Campennì, A. Autoimmune endocrine diseases. Minerva Endocrinol. 2018, 43, 305-322. [CrossRef]

- Su, M.A.; Anderson, M.S. Monogenic autoimmune diseases: insights into self-tolerance. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 20R-25R. [CrossRef]

- Betterle, C.; Dal Pra, C.; Mantero, F.; Zanchetta, R. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: autoantibodies, autoantigens, and their applicability in diagnosis and disease prediction. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 327-364. [CrossRef]

- Betterle, C.; Furmaniak, J.; Sabbadin, C.; Scaroni, C.; Presotto, F. Type 3 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (APS-3) or type 3 multiple autoimmune syndrome (MAS-3): an expanding galaxy. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2023, 46, 643-665. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-uricoechea, H.; Nogueira, J.P.; Pinz, V.; Schwarzstein, D. The Usefulness of Thyroid Antibodies in the Diagnostic Approach to Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. Antibodies 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Torii, S. Expression and function of IA-2 family proteins, unique neuroendocrine-specific protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Endocr. J. 2009, 56, 639-648. [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Swensen, A.C.; Qian, W.J. Serum biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of type 1 diabetes. Transl. Res. 2018, 201, 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Øksnes, M.; Husebye, E.S. Approach to the patient: Diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency in adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, dgad402. [CrossRef]

- Meager, A.; Visvalingam, K.; Peterson, P.; Möll, K.; Murumägi, A.; Krohn, K.; Eskelin, P.; Perheentupa, J.; Husebye, E.; Kadota, Y.; et al. Anti-interferon autoantibodies in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, 1152–1164. [CrossRef]

- Kisand, K.; Bøe Wolff, A.S.; Podkrajšek, K.T.; Tserel, L.; Link, M.; Kisand, K. V.; Ersvaer, E.; Perheentupa, J.; Erichsen, M.M.; Bratanic, N.; et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 299–308. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.A.; Criswell, L,A. PTPN22: Its role in SLE and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 2007, 40, 582–590. [CrossRef]

- Fichna, M.; Małecki, P.P.; Żurawek, M.; Furman, K.; Gębarski, B.; Fichna, P.; Ruchała, M. Genetic variants and risk of endocrine autoimmunity in relatives of patients with Addison's disease. Endocr. Connect. 2023, 12, e230008. [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.C.; Simmonds, M.J. The HLA Region and Autoimmune Disease: Associations and Mechanisms of Action. Curr. Genomics 2007, 8, 453-65. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Baek, I.C.; Kim, H.J.; Choi. E.J.; Ahn, M.; Jung, M.H.; Suh, B.K.; Cho, W.K.; Kim, T.G. HLA alleles, especially amino-acid signatures of HLA-DPB1, might contribute to the molecular pathogenesis of early-onset autoimmune thyroid disease. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216941. [CrossRef]

- Gambelunghe, G.; Falorni, A.; Ghaderi, M.; Laureti, S.; Tortoioli, C.; Santeusanio, F.; Brunetti, P.; Sanjeevi, C.B. Microsatellite polymorphism of the MHC class I chain-related (MIC-A and MIC-B) genes marks the risk for autoimmune Addison's disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 3701-3707. [CrossRef]

- Savvateeva, E.N.; Yukina, M.Y.; Nuralieva, N.F.; Filippova, M.A.; Gryadunov, D.A., Troshina, E.A. Multiplex Autoantibody Detection in Patients with Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndromes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5502. [CrossRef]

- Nuralieva, N.; Yukina, M.; Sozaeva, L.; Donnikov, M.; Kovalenko, L.; Troshina, E.; Orlova, E.; Gryadunov, D.; Savvateeva, E.; Dedov, I. Diagnostic Accuracy of Methods for Detection of Antibodies against Type I Interferons in Patients with Endocrine Disorders. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1948. [CrossRef]

- Frommer, L.; Kahaly, G.J. Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 4769-4782. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, D.; Røyrvik, E.C.; Aranda-Guillén, M.; Berger, A.H.; Landegren, N.; Artaza, H.; Hallgren, Å.; Grytaas, M.A.; Ström, S.; Bratland, E. et al. GWAS for autoimmune Addison's disease identifies multiple risk loci and highlights AIRE in disease susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 959. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.; Gargano, M.; Matentzoglu, N.; Carmody, L.C.; Lewis-Smith, D.; Vasilevsky, N.A.; Danis, D.; Balagura, G.; Baynam, G.; Brower, A.M.; et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 8, D1207-D1217. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.S.; da Silva, J.G.; Tomaz, R.A.; Pinto, A.E.; Bugalho, M.J.; Leite, V.; Cavaco, B.M. Identification of a novel germline FOXE1 variant in patients with familial non-medullary thyroid carcinoma (FNMTC). Endocrine 2015, 49, 204-214. [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, Y.; Park, Y.J. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases, Thyroid Function, and Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 2018, 33, 175-184. [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Widiapradja, A.; Levick, S.P.; McKelvey, K.J.; Liao, X.H.; Refetoff, S.; Bullock, M.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J. Foxe1 Deletion in the Adult Mouse Is Associated With Increased Thyroidal Mast Cells and Hypothyroidism. Endocrinology 2022 163, bqac158. [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17, 405-424. [CrossRef]

- Yukina, M.Y.; Larina, A.A.; Vasilyev, E.V.; Troshina, E.A.; Dimitrova, D.A. Search for Genetic Predictors of Adult Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome in Monozygotic Twins. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2021, 14, 11795514211009796. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Abe-Dohmae, S.; Iwamoto, N.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Yokoyama, S. Helical apolipoproteins of high-density lipoprotein enhance phagocytosis by stabilizing ATP-binding cassette transporter A7. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2591-2599. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Yoshino, Y.; Kawabe, K.; Ibuki, T.; Ochi, S.; Mori, Y.; Ozaki, Y.; Numata, S.; Iga, J.I.; Ohmori, T.; et al. ABCA7 Gene Expression and Genetic Association Study in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 441-446. [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, B.E.; Berger, A.H.; Bruserud, Ø.; Goldfarb, Y.; Sulen, A.; Breivik, L.; Hellesen, A.; Ben-Dor, S.; Haffner-Krausz, R.; Knappskog, P.M.; et al. A partial form of AIRE deficiency underlies a mild form of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J. Clin. Invest. 2023, 133, e169704. [CrossRef]

- Yukina, M.Yu.; Nuralieva, N.F.; Troshina, E.A. Analysis of the prevalence and incidence of adrenal insufficiency in the world. Ateroscleroz 2022, 18, 426-429. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, H.; Howson, J.M.; Esposito, L.; Heward, J.; Snook, H.; Chamberlain, G.; Rainbow, D.B.; Hunter, K.M.; Smith, A.N.; Di Genova, G.; et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 2003, 423, 506-511. [CrossRef]

- Maine, C.J.; Hamilton-Williams, E.E.; Cheung, J.; Stanford, S.M.; Bottini, N.; Wicker, L.S.; Sherman, L.A. PTPN22 alters the development of regulatory T cells in the thymus. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 5267-5275. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Yoo, S.A.; Kim, M.; Kim, W.U. The Role of Calcium-Calcineurin-NFAT Signaling Pathway in Health and Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 195. [CrossRef]

- Napier, C.; Mitchell, A.L.; Gan, E.; Wilson, I.; Pearce, S.H. Role of the X-linked gene GPR174 in autoimmune Addison's disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E187-E190. [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, C.; Guerini, F.R.; Bolognesi, E.; Zanzottera, M.; Clerici, M. VDR Gene Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Autoimmunity: A Narrative Review. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 916. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.H.; Cui, L.; Jiang, X.X.; Song, Y.D.; Liu, S.S.; Wu, K.Y.; Dong, H.J.; Mao, M.; Ovlyakulov, B.; Wu, H.M.; et al. Autoimmune Disease Associated CLEC16A Variants Convey Risk of Parkinson's Disease in Han Chinese. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 856493. [CrossRef]

- Richard-Miceli, C.; Criswell, L.A. Emerging patterns of genetic overlap across autoimmune disorders. Genome Med. 2012, 4, 6. [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, Y.; Baujat, G.; Botschen, U.; Wittkampf, T.; du Moulin, M.; Stella, J.; Le Merrer, M.; Guest, G.; Lambot, K.; Tazarourte-Pinturier, M.F.; et al. Generalized arterial calcification of infancy and pseudoxanthoma elasticum can be caused by mutations in either ENPP1 or ABCC6. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Farh, K.K.; Marson, A.; Zhu, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Housley, W.J.; Beik, S.; Shoresh, N.; Whitton, H.; Ryan, R.J.; Shishkin, A.A.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature 2015, 518, 337-343. [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, M.; Brown, C.D.; Maranville, J.C. A catalog of GWAS fine-mapping efforts in autoimmune disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 549-563. [CrossRef]

- Belova, V.; Pavlova, A.; Afasizhev, R.; Moskalenko, V.; Korzhanova, M.; Krivoy, A.; Cheranev, V.; Nikashin, B.; Bulusheva, I.; Rebrikov, D.; et al. System Analysis of the Sequencing Quality of Human Whole Exome Samples on BGI NGS Platform. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 609. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data; Babraham Institute: Cambridge, UK, 2017.

- Bushnell, B. BBMap: A Fast, Accurate, Splice-Aware Aligner. 2014. Available online: https://github.com/BioInfoTools/BBMap (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Li, H.; Durbin, H. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–176. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [CrossRef]

- Broad Institute. Picard Toolkit. 2014. Available online: https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Li, H. A Statistical Framework for SNP Calling, Mutation Discovery, Association Mapping and Population Genetical Parameter Estimation from Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2987–2993. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Kang, H.M. Unified Representation of Genetic Variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2202–2204. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, K. InterVar: Clinical Interpretation of Genetic Variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP Guidelines. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Buianova, A.A.; Proskura, M.V.; Cheranev, V.V.; Belova, V.A.; Shmitko, A.O.; Pavlova, A.S.; Vasiliadis, I.A.; Suchalko, O.N.; Rebrikov, D.V.; Petrosyan, E.K.; et al. Candidate Genes for IgA Nephropathy in Pediatric Patients: Exome-Wide Association Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15984. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Chang, C. PLINK v. 1.90b6.24. Available online https://github.com/chrchang/plink-ng/tree/master/1.9 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J.; Maccari, G.; Georgiou, X.; Cooper, M.A.; Flicek, P.; Robinson, J.; Marsh, S.G.E. The IPD-IMGT/HLA Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1053-D1060. [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010, 10, 564-567. [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166-1167. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).