1. Introduction

Modern deep learning systems for industrial applications such as online advertising and recommendation engines face unprecedented scaling challenges due to massive parameter counts exceeding terabyte-scale dimensions. Click-through rate (CTR) prediction models, which estimate the probability of user engagement with digital content, exemplify this trend with sparse feature dimensions surpassing

unique identifiers [

1,

2]. These models employ embedding layers that convert high-dimensional sparse inputs into dense representations, followed by fully-connected neural networks that capture complex feature interactions.

The computational demands of training such massive models have traditionally been addressed through distributed CPU clusters employing message passing interface (MPI) frameworks [

3]. While functional, these solutions suffer from substantial communication overhead, limited scalability, and prohibitive operational costs. As model sizes continue to grow exponentially, simply scaling out CPU resources becomes economically and technically unsustainable. Even with hundreds of nodes, synchronization latency and network bandwidth constraints create fundamental bottlenecks that impede training throughput and research velocity.

Graphics processing units (GPUs) offer compelling acceleration potential but introduce their own constraints, primarily limited high-bandwidth memory (HBM) capacity relative to model sizes. Prior GPU-based parameter server implementations [

4,

5] attempted to circumvent this limitation by caching parameters in CPU memory, but incurred significant PCIe transfer overhead that diminished the computational advantages. The fundamental challenge remains: how to leverage GPU acceleration for terabyte-scale models that exceed the aggregate memory of practical computing clusters.

This paper introduces StrataServe, a distributed hierarchical parameter server that coordinates GPU HBM, CPU DRAM, and solid-state drives (SSDs) into a unified parameter-serving hierarchy. Our system employs a novel architecture that maintains working parameters exclusively in GPU memory, eliminates CPU-GPU data transfer bottlenecks through direct peer-to-peer GPU communication, and efficiently manages out-of-core parameters through optimized SSD access patterns. By aligning storage technologies with their optimal usage patterns and carefully orchestrating data movement between hierarchy levels, StrataServe enables efficient training of previously impractical model sizes.

Experimental evaluation on production CTR prediction workloads demonstrates that a 4-node StrataServe configuration outperforms 75-150 node CPU clusters by 1.8-4.8× while maintaining equivalent accuracy. More significantly, the price-performance ratio improves by 4.4-9.0×, making massive model training substantially more accessible. The contributions of this work include: (1) a hierarchical parameter server architecture coordinating HBM, DRAM, and SSD storage; (2) a distributed GPU hash table with direct inter-GPU communication; (3) a 4-stage pipeline that overlaps computation and data movement; and (4) comprehensive evaluation on industrial-scale models confirming production viability.

2. Related Work

Distributed training for large-scale neural networks has evolved through several architectural paradigms. The parameter server concept [

3] emerged as a dominant framework, separating model parameters from worker nodes to enable data parallelism. Early implementations focused primarily on CPU-based clusters with synchronous [

6] and asynchronous [

7] update strategies. These systems demonstrated scalability to hundreds of nodes but faced fundamental communication bottlenecks as model sizes grew into terabyte territory.

GPU-accelerated parameter servers attempted to leverage the computational advantages of modern accelerators. GeePS [

4] introduced a two-layer architecture that maintained parameters in CPU memory while fetching working sets to GPUs, but incurred substantial PCIe transfer overhead. Poseidon [

8] employed wait-free backpropagation and hybrid communication strategies to optimize network utilization, while Gaia [

9] addressed geo-distributed training across wide-area networks. These systems improved training efficiency but remained constrained by CPU memory capacity limitations.

Model compression techniques, particularly feature hashing [

10,

11], offered an alternative approach by reducing parameter counts through dimensionality reduction. Methods like one permutation hashing with random projections [

12] achieved significant model size reduction but incurred accuracy degradation unacceptable for production systems where even 0.1% performance regression translates to substantial revenue impact. Our experiments in

Section 3 confirm that while hashing enables single-machine training, the accuracy tradeoffs preclude deployment in revenue-critical applications.

Storage hierarchy exploitation has been explored in database systems [

13,

14] and key-value stores [

15,

16,

17]. FlashStore [

17] optimized hash functions for compact memory footprints, while WiscKey [

18] separated keys and values to minimize I/O amplification. These principles inform our SSD parameter server design, though we specialize for the unique access patterns of neural network training.

Recent work on hierarchical memory systems for deep learning includes Bandana [

19], which utilized non-volatile memory for model storage, and FlexPS [

20], which introduced flexible parallelism control. However, these approaches either targeted different problem domains or lacked the comprehensive hierarchy coordination necessary for terabyte-scale models. StrataServe distinguishes itself through its integrated three-layer architecture specifically optimized for the sparsity patterns and access characteristics of massive embedding models.

Industrial CTR prediction systems have evolved from logistic regression models to sophisticated deep learning architectures including Wide&Deep [

21], DeepFM [

22], and Deep Interest Network [

2]. These models consistently demonstrate that maintaining full parameter spaces yields superior accuracy compared to compressed representations, creating the fundamental tension that StrataServe resolves: preserving model fidelity while enabling computationally feasible training.

3. Motivation: The Limitations of Hashing and MPI Clusters

Before presenting our hierarchical parameter server architecture, we examine why alternative approaches prove inadequate for production-scale systems. Model compression through feature hashing represents an intuitively appealing solution to the parameter explosion problem. We conducted extensive experiments with the One Permutation + One Sign Random Projection (OP+OSRP) hashing method, which reduces dimensionality through column permutation, binning, and randomized projection.

Table 1 illustrates the performance impact of increasingly aggressive hashing on web search advertising data. While hashing reduces parameter counts by 2-4 orders of magnitude, the corresponding AUC degradation renders these models unsuitable for production deployment. Even with

bins preserving 3 billion parameters—substantial compression from the original 199 billion—AUC decreases by 1.14%, representing commercially significant revenue loss. This sensitivity stems from the collision probability in hashing, which inevitably maps distinct features to identical embeddings, blurring semantic distinctions crucial for accurate prediction.

MPI-based distributed training clusters represent the conventional alternative, partitioning parameters across numerous CPU nodes (typically 75-150 nodes for production systems). While functionally capable of training massive models, this approach suffers from three fundamental limitations: (1) communication overhead dominates computation as node count increases, (2) hardware and maintenance costs scale linearly with cluster size, and (3) parameter staleness in asynchronous updates impedes convergence speed. Our measurements indicate that beyond approximately 50 nodes, additional resources yield diminishing returns due to synchronization overhead.

These limitations motivated the development of StrataServe, which preserves model accuracy by maintaining the full parameter space while overcoming computational barriers through memory hierarchy optimization rather than brute-force cluster scaling. By strategically placing parameters across HBM, DRAM, and SSD based on access patterns, we achieve the computational benefits of GPU acceleration without the accuracy compromises of hashing or the scalability limits of massive CPU clusters.

4. StrataServe Architecture

StrataServe employs a three-tier hierarchical architecture that coordinates GPU high-bandwidth memory (HBM-PS), CPU main memory (MEM-PS), and solid-state drives (SSD-PS) into a unified parameter-serving system. This design reflects the fundamental access pattern disparity in massive embedding models: while the total parameter space reaches terabytes, each training example references only a tiny fraction (typically 100-500 parameters) due to extreme sparsity in the input features.

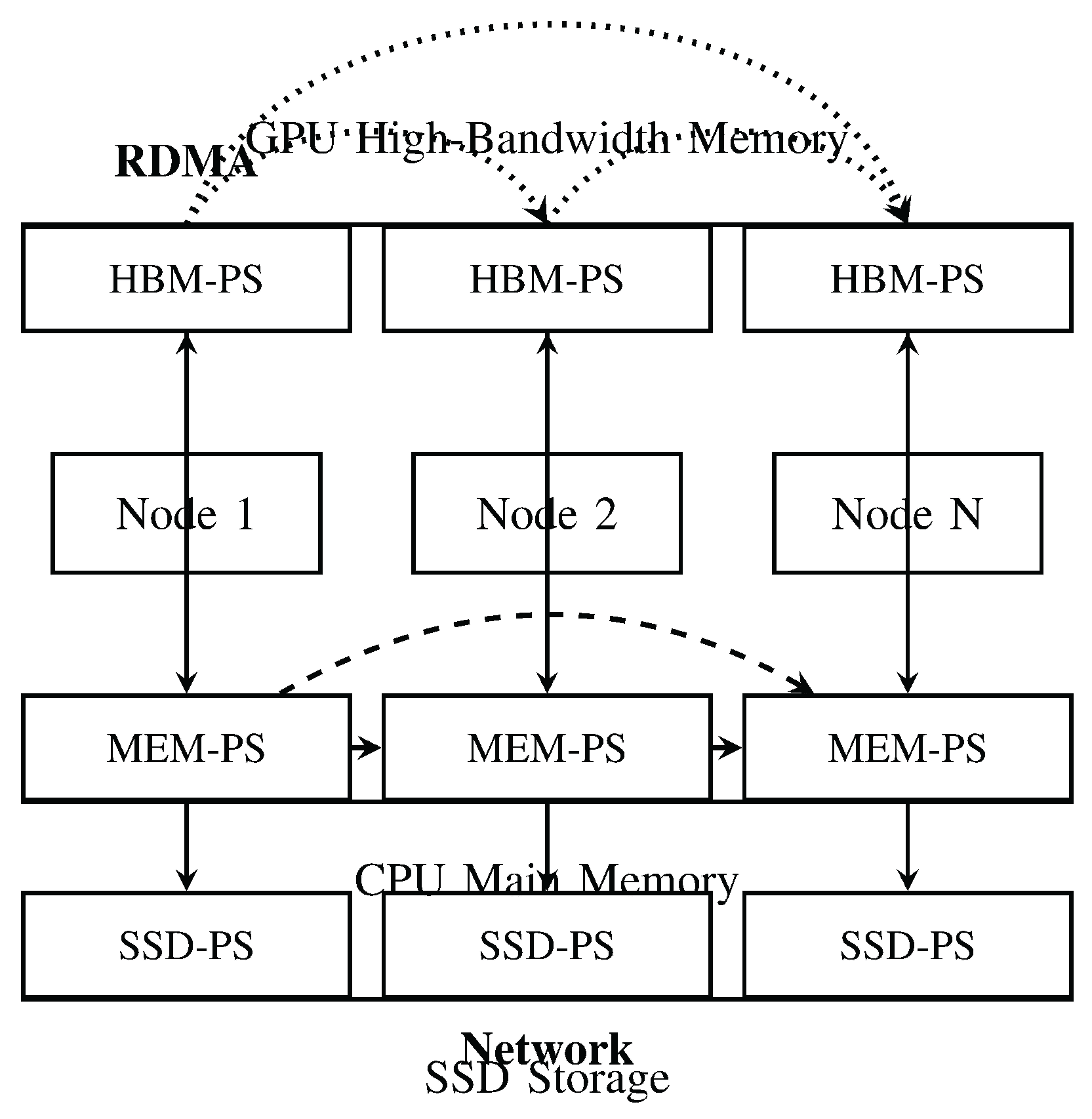

Figure 1 illustrates the system architecture. The HBM-PS maintains working parameters distributed across GPU memories within and across nodes, employing a distributed hash table for efficient access. The MEM-PS acts as an intermediate cache, prefetching parameters from SSDs and coordinating with peer nodes to gather required parameters. The SSD-PS provides persistent storage for the complete parameter space, organized in file-grained units optimized for sequential access.

The training workflow follows a carefully orchestrated sequence: (1) each node processes its assigned data batches, identifying referenced parameters; (2) MEM-PS gathers local parameters from SSD-PS and remote parameters from peer MEM-PS instances; (3) parameters are partitioned and transferred to HBM-PS; (4) GPU workers execute forward and backward propagation, synchronizing updates through all-reduce communication; (5) MEM-PS collects updates and periodically persists them to SSD-PS. This workflow maximizes GPU utilization by ensuring that data movement occurs concurrently with computation.

A critical innovation in StrataServe is the four-stage execution pipeline that overlaps network communication, SSD I/O, CPU processing, and GPU computation. Each stage operates independently with dedicated prefetch buffers, hiding the latency of slower operations (particularly SSD access and network transfers) behind GPU computation. The pipeline capacities are tuned to match the execution characteristics of each stage, ensuring that GPUs remain continuously active without stalling for data.

5. HBM-PS: Distributed GPU Parameter Serving

The HBM-PS component manages parameter storage and access within GPU high-bandwidth memory, forming the performance-critical foundation of StrataServe. Unlike prior systems that treated GPU memory as a cache with frequent CPU-GPU transfers, HBM-PS maintains the complete working parameter set exclusively in GPU memory throughout training iterations, eliminating PCIe transfer overhead.

We implement a distributed hash table spanning all GPUs within the system, with parameters sharded across devices using a modulo-based partitioning scheme. Each GPU maintains a local hash table implemented using concurrent_unordered_map from the cuDF library, which employs open addressing for collision resolution. The hash table capacity is fixed during initialization based on the expected parameter count per GPU, avoiding expensive dynamic memory allocation during training.

Parameter access operations follow a carefully designed protocol. The

get operation retrieves parameter values for forward propagation, while

accumulate applies gradient updates during backward propagation. Algorithm 1 illustrates the accumulate operation, which partitions key-value pairs by destination GPU and asynchronously transmits them via NVLink. This approach maximizes interconnect utilization by batching communications and overlapping transfers with computation.

|

Algorithm 1 Distributed Hash Table Accumulate Operation |

-

Require:

Key-value pairs

- 1:

Switch to GPU owning input memory - 2:

Partition by destination GPU - 3:

for each GPU i in parallel do

- 4:

Asynchronously send to GPU i

- 5:

end for - 6:

Wait for all sends to complete - 7:

for each GPU i do

- 8:

Switch to GPU i

- 9:

Asynchronously accumulate into local hash table - 10:

end for |

Inter-node GPU communication employs Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) over Converged Ethernet (RoCE), enabling direct GPU-to-GPU transfers without CPU involvement or system memory buffering. This zero-copy communication path substantially reduces latency and CPU overhead compared to traditional approaches that stage data through host memory. Parameter synchronization across nodes follows an all-reduce pattern that combines inter-node and intra-node reduction phases to efficiently aggregate updates from all workers.

For dense parameters in fully-connected layers—which constitute a small fraction of total parameters but are accessed by every example—we employ a replication strategy that maintains copies in each GPU’s HBM. This optimization eliminates communication overhead for these frequently accessed parameters while consuming negligible additional memory due to their relatively small size compared to embedding tables.

The HBM-PS design effectively addresses the memory capacity limitations of individual GPUs by federating HBM across the entire system while maintaining the performance advantages of GPU-resident parameters through efficient communication patterns and access protocols.

6. MEM-PS and SSD-PS: Memory and Storage Hierarchy

The MEM-PS and SSD-PS components manage the memory and storage hierarchy that supports the HBM-PS, providing capacity for parameters that exceed aggregate GPU memory while maintaining efficient access patterns. MEM-PS serves as an intelligent cache and coordination layer, while SSD-PS provides persistent storage for the complete parameter space.

MEM-PS implements a parameter gathering mechanism that identifies required parameters from input batches, retrieves local parameters from SSD-PS, and fetches remote parameters from peer nodes. Parameters are partitioned across nodes using the same modulo hashing scheme employed by HBM-PS, ensuring consistent mapping throughout the hierarchy. This consistency minimizes coordination overhead when moving parameters between levels.

We employ a hybrid cache eviction policy that combines least-recently-used (LRU) and least-frequently-used (LFU) strategies. Newly accessed parameters enter an LRU cache, while evicted parameters migrate to an LFU cache. This approach captures both recency and frequency access patterns common in embedding models, where certain parameters (e.g., frequently occurring user demographics or popular content) receive disproportionate attention. Working parameters for current and prefetched batches are pinned in memory to prevent premature eviction.

SSD-PS organizes parameters in file-grained units optimized for sequential access, addressing the fundamental mismatch between SSD block I/O and fine-grained parameter access. Each file contains a collection of parameters, with an in-memory mapping maintaining the correspondence between parameters and their host files. When reading parameters, SSD-PS loads entire files containing required parameters, amortizing I/O overhead across multiple parameters. While this approach may read unnecessary parameters, the sequential access pattern achieves substantially higher throughput than random reads.

Parameter updates are handled through an append-only strategy that writes updated parameters as new files rather than modifying existing files in place. This approach leverages the superior write performance of sequential operations compared to random updates. The mapping is updated to reference the new versions, rendering previous copies stale. A background compaction process periodically merges files with high proportions of stale parameters, reclaiming storage space and maintaining read performance.

File compaction employs a leveled strategy inspired by LevelDB, merging files when stale parameters exceed a threshold (typically 50%). This approach bounds storage overhead to approximately 2× the active parameter size while minimizing compaction frequency. The compaction process selectively merges files based on staleness metrics, prioritizing those with the highest potential storage reclamation.

The MEM-PS and SSD-PS combination effectively extends the usable parameter capacity beyond physical memory limits while maintaining acceptable access latency through caching and I/O optimization. This hierarchical approach enables training of models that would be impossible with pure in-memory strategies while avoiding the accuracy compromises of model compression techniques.

7. Experimental Evaluation

We evaluated StrataServe on production click-through rate prediction workloads to assess training performance, accuracy preservation, and scalability. Our experimental setup comprised 4 GPU nodes, each equipped with 8×32GB HBM GPUs, 48-core CPUs, 1TB DRAM, 20TB NVMe SSDs, and 100Gb RDMA networking. We compared against a production MPI cluster using 75-150 CPU nodes with comparable per-node specifications.

Table 2 describes the five production models used in our evaluation, spanning parameter sizes from 300GB to 10TB. These models represent actual deployment scenarios in web search advertising, with sparse parameter counts ranging from 8 billion to 200 billion. The MPI cluster configurations reflect current production deployments for each model, demonstrating the substantial resources required for conventional distributed training.

7.1. Performance Comparison with MPI Solution

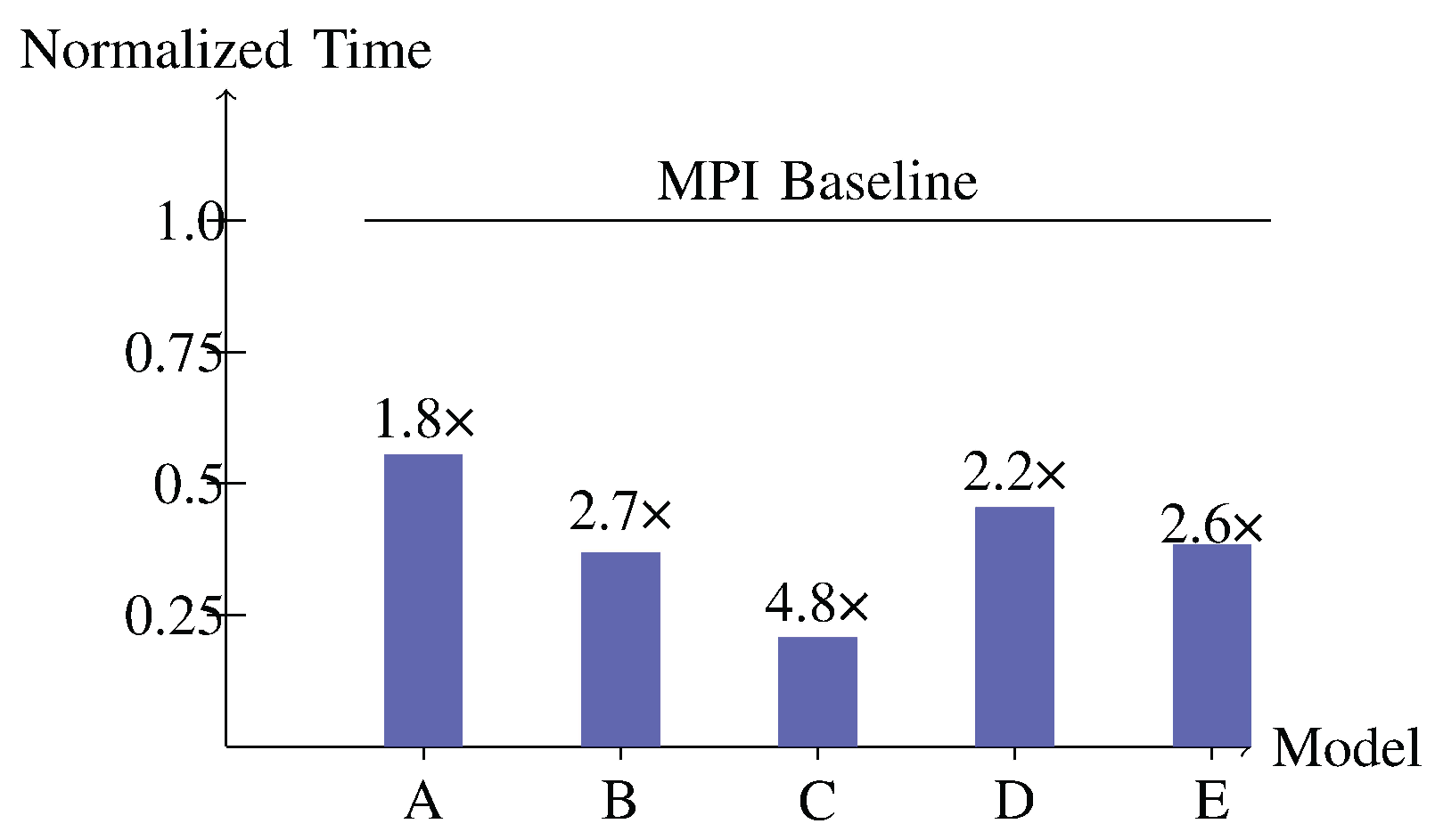

We measured end-to-end training time for all models using both StrataServe (4 nodes) and the production MPI cluster.

Figure 2 shows the normalized execution time, with StrataServe achieving speedups of 1.8-4.8× across the model spectrum. The largest performance gains occurred for intermediate-sized models (C and D), where the balance between computation and communication best matches StrataServe’s architectural advantages.

More significantly, we evaluated price-performance ratio by normalizing for hardware and maintenance costs. Since each GPU node costs approximately 10× equivalent CPU nodes, the 4-node StrataServe configuration represents substantially lower expenditure than the 75-150 node MPI clusters.

Table 3 shows the cost-normalized speedup, with StrataServe delivering 4.4-9.0× better price-performance across all models.

Accuracy measurements confirmed that StrataServe maintains production-grade model quality. Online A/B testing over 24-hour periods showed AUC differences within 0.1% compared to MPI-trained models, with some models showing slight improvements due to reduced parameter staleness in the smaller cluster configuration. This accuracy preservation is crucial for production deployment where even minor regression carries significant business impact.

7.2. System Characterization

We analyzed execution time distribution across major system components to identify potential bottlenecks. For smaller models (A and B), HDFS data loading dominated execution time due to the relatively light parameter access requirements. As model size increased (C-E), parameter gathering became the dominant factor, though the four-stage pipeline effectively hid much of this latency behind GPU computation.

HBM-PS operations showed expected correlation with model characteristics: pull/push operation time depended on input non-zero counts, while training computation scaled with dense parameter counts. The distributed hash table demonstrated linear scaling with parameter access rates, with inter-GPU communication consuming less than 15% of total HBM-PS time even for the largest models.

MEM-PS cache performance showed rapid warm-up, reaching 46% hit rate within 40 batches and stabilizing thereafter. This effective caching substantially reduced SSD access frequency, with approximately half of parameter requests served directly from memory. The hybrid LRU-LFU policy effectively captured the access patterns of production workloads, where certain parameters receive disproportionate attention.

SSD-PS exhibited predictable I/O patterns with periodic compaction-induced spikes. The append-only update strategy achieved sustained write throughput of 1.5GB/s per node, while read performance reached 2GB/s during parameter loading. Compaction operations occurred approximately every 50 batches for the largest model, temporarily increasing I/O time but maintaining sustainable storage growth.

Scalability analysis demonstrated near-linear throughput scaling from 1 to 4 nodes, achieving 3.57× speedup on 4 nodes compared to the ideal 4× linear scaling. The slight sub-linear trend resulted from increased inter-node communication in larger configurations, though RDMA optimization minimized this overhead. These results confirm that StrataServe effectively leverages additional nodes without encountering fundamental scalability barriers.

8. Conclusions

StrataServe demonstrates that hierarchical parameter serving across HBM, DRAM, and SSD enables efficient training of terabyte-scale embedding models without accuracy compromises. By coordinating storage technologies according to their access characteristics and optimizing data movement between hierarchy levels, we overcome the memory capacity limitations that previously constrained GPU-accelerated training of massive models.

Our evaluation on production click-through rate prediction workloads confirms both the performance and economic advantages of this approach. A 4-node StrataServe configuration outperforms 75-150 node CPU clusters while reducing hardware and maintenance costs substantially. The architecture maintains production-grade accuracy and demonstrates scalable performance across model sizes from 300GB to 10TB.

The principles embodied in StrataServe—hierarchy-aware parameter placement, direct inter-GPU communication, and pipelined execution—provide a blueprint for scaling distributed learning systems as model sizes continue to grow. Rather than relying on brute-force cluster expansion or accuracy-compromising compression, this approach offers a sustainable path forward for training the massive models required by modern AI applications.

Future work includes extending the hierarchy to incorporate emerging memory technologies such as non-volatile RAM, optimizing for heterogeneous workload patterns, and developing more sophisticated parameter placement strategies based on access prediction. The StrataServe architecture represents a significant step toward making massive-scale model training both computationally feasible and economically practical.

References

- Fan, M.; Guo, J.; Zhu, S.; Miao, S.; Sun, M.; Li, P. MOBIUS: towards the next generation of query-ad matching in baidu’s sponsored search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2019, pp. 2509–2517.

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, X.; Song, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, J.; Li, H.; Gai, K. Deep interest network for click-through rate prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2018, pp. 1059–1068.

- Li, M.; Andersen, D.G.; Park, J.W.; Smola, A.J.; Ahmed, A.; Josifovski, V.; Long, J.; Shekita, E.J.; Su, B.Y. Scaling distributed machine learning with the parameter server. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 14), 2014, pp. 583–598.

- Cui, H.; Zhang, H.; Ganger, G.R.; Gibbons, P.B.; Xing, E.P. GeePS: Scalable deep learning on distributed GPUs with a GPU-specialized parameter server. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh European Conference on Computer Systems, 2016, pp. 1–16.

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Xie, D.; Qian, Y.; Jia, R.; Li, P. AIBox: CTR prediction model training on a single node. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2019, pp. 319–328.

- Valiant, L.G. A bridging model for parallel computation. 1990, Vol. 33, pp. 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Q.; Cipar, J.; Cui, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.K.; Gibbons, P.B.; Gibson, G.A.; Ganger, G.R.; Xing, E.P. More effective distributed ML via a stale synchronous parallel parameter server. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2013, pp. 1223–1231.

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, S.; Dai, W.; Ho, Q.; Liang, X.; Hu, Z.; Wei, J.; Xie, P.; Xing, E.P. Poseidon: An efficient communication architecture for distributed deep learning on GPU clusters. In Proceedings of the 2017 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 17), 2017, pp. 181–193.

- Hsieh, K.; Harlap, A.; Vijaykumar, N.; Konomis, D.; Ganger, G.R.; Gibbons, P.B.; Mutlu, O. Gaia: Geo-distributed machine learning approaching LAN speeds. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 17), 2017, pp. 629–647.

- Weinberger, K.; Dasgupta, A.; Langford, J.; Smola, A.; Attenberg, J. Feature hashing for large scale multitask learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th annual international conference on machine learning, 2009, pp. 1113–1120.

- Li, P.; Shrivastava, A.; Moore, J.; König, A.C. Hashing algorithms for large-scale learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2011, pp. 2672–2680.

- Li, P.; Owen, A.B.; Zhang, C.H. One permutation hashing. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, 2012, pp. 3122–3130.

- Chou, H.T.; DeWitt, D.J. An evaluation of buffer management strategies for relational database systems. 1986, Vol. 1, pp. 311–336.

- O’Neil, E.J.; O’Neil, P.E.; Weikum, G. The LRU-K page replacement algorithm for database disk buffering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data, 1993, pp. 297–306.

- Andersen, D.G.; Franklin, J.; Kaminsky, M.; Phanishayee, A.; Tan, L.; Vasudevan, V. FAWN: A fast array of wimpy nodes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 22nd symposium on Operating systems principles, 2009, pp. 1–14.

- Lim, H.; Fan, B.; Andersen, D.G.; Kaminsky, M. SILT: A memory-efficient, high-performance key-value store. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Third ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2011, pp. 1–13.

- Debnath, B.K.; Sengupta, S.; Li, J. FlashStore: High throughput persistent key-value store. 2010, Vol. 3, pp. 1414–1425. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Pillai, T.S.; Gopalakrishnan, H.; Arpaci-Dusseau, A.C.; Arpaci-Dusseau, R.H. WiscKey: Separating keys from values in SSD-conscious storage. 2017, Vol. 13, pp. 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, A.; Naumov, M.; Gardner, D.; Smelyanskiy, M.; Pupyrev, S.; Hazelwood, K.; Cidon, A.; Katti, S. Bandana: Using non-volatile memory for storing deep learning models. 2018.

- Huang, Y.; Jin, T.; Wu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yan, X.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, J. FlexPS: Flexible parallelism control in parameter server architecture. 2018, Vol. 11, pp. 566–579. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.T.; Koc, L.; Harmsen, J.; Shaked, T.; Chandra, T.; Aradhye, H.; Anderson, G.; Corrado, G.; Chai, W.; Ispir, M.; et al. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st workshop on deep learning for recommender systems, 2016, pp. 7–10.

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: a factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2017, pp. 1725–1731.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).